Abstract

Belief in a just world (BJW) has been assumed to promote subjective well-being. The results of cross-sectional studies have been consistent with this assumption but inconclusive about the causal origins of the correlations. Correia et al. (2009a) experimentally tested the original hypothesis (BJW causes subjective well-being) against the alternative hypothesis (subjective well-being causes BJW) and found support for both. Our Study 1 comprised four experiments that repeated and extended Correia et al.’s (2009a) experiments and fully replicated their findings. Study 2 reanalyzed a longitudinal data set regarding the interrelationships of several variants of BJW and subjective well-being. Cross-lagged panel analyses revealed very weak support for the original hypothesis and a little but not much more support for the alternative hypothesis. Taken together, the findings from both studies are consistent with Correia et al.’s (2009a) findings and suggest that the causal relationship between BJW and SWB is bidirectional in nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

People need to believe in a just world, a world in which good citizenship behavior is rewarded and antisocial conduct is punished (Lerner, 1980). According to Dalbert (2001), belief in a just world (BJW) serves three psychological functions. First, it helps people cope with observed injustice by assimilating it into a belief in justice. The blaming and derogating of victims are examples (Hafer & Bègue, 2005). If victims can be made responsible for their misfortune because they behaved carelessly, they can no longer be considered innocent (Ellard et al., 2016). Such assimilation offers observers a sense of control (Lerner & Miller, 1978). If they behave decently and follow the norms of conduct, they will not become victims. Second, believing in justice implies that one can trust one’s fellow citizens. Among other implications, trusting others makes investing in long-term projects worthwhile, such as education, friendships, or starting a family (Hafer, 2000). Third, believing in justice motivates people to treat their fellow citizens justly because fair behavior will be reciprocated (Sutton & Winnard, 2007).

Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being

Because these psychological functions are adaptive, BJW should promote subjective well-being. This effect should be especially true for personal belief in a just world (personal BJW; Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2019; Sutton & Douglas, 2005). Personal BJW differs from general belief in a just world (general BJW) in that the former asserts justice for the self, whereas the latter refers to justice for others (Dalbert, 1999; Lipkus et al., 1996). Therefore, personal BJW should be more relevant for subjective well-being than general BJW.

These assumptions have received empirical support. Several studies have found correlations between BJW and subjective well-being. Moreover, studies that measured personal BJW and general BJW separately found that subjective well-being was more strongly correlated with personal BJW than with general BJW. Several reviews of these findings are available (Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2019; Correia et al., 2009a; Dalbert, 1998, 1999, 2001; Dalbert & Donat, 2015; Donat et al., 2016; Furnham, 2003; Hafer & Sutton, 2016). The research we report in the present paper contributes to this literature. In two studies, the first experimental and the second longitudinal, we investigated the causal nature of the relationship between BJW and subjective well-being.

Additional Variants of the Belief in a Just World

Besides the subdivision of BJW into personal BJW and general BJW, additional variants of BJW have been proposed in the literature. First, having a weak belief in justice does not imply that one has a strong belief in injustice. Some people who do not believe in a just world may in fact believe that the world is unjust. Others, however, might not believe in a just world or in an unjust world. Therefore, it is worthwhile to conceptualize BJW and belief in an unjust world as separate constructs (Dalbert, Lipkus, Sally, & Goch, 2001). Next, Maes (1998) proposed a differentiation between the belief in immanent justice and the belief in ultimate justice. The former reflects the belief that favorable versus unfavorable outcomes are inherent consequences of a person’s behavior. This belief promotes the blaming of victims if helping them is impossible or would be too costly for the observer. By contrast, believers in ultimate justice admit that injustice happens but claim that justice will be restored eventually (i.e., that innocent victims will eventually be compensated and perpetrators will eventually be punished). Accordingly, the belief in ultimate justice can be further subdivided into the belief in victim compensation and the belief in perpetrator punishment. Maes and Schmitt (1999) found that the belief in immanent justice and the two kinds of beliefs in ultimate justice had different correlations with relevant third variables, such as blaming victims. In the previous literature, possible associations between these BJW variants and subjective well-being were not considered even though they can be assumed. First, the correlations of BJW and belief in an unjust world with subjective well-being might differ not only in direction but also in strength (Dalbert et al., 2001). Next, the belief in ultimate justice might better protect victims from emotional suffering because they can trust that they will eventually be compensated. By contrast, victims who believe in immanent justice might more readily think that they deserve to be punished. The opposite effects can be expected for perpetrators. Perpetrators who believe in immanent justice might fear that they will be punished soon, whereas perpetrators who believe in ultimate justice might engage in the temporal discounting of punishment in the distant future. We investigated these ideas in the exploratory part of our Study 2.

Components of Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being has been decomposed into an emotional component (positive affect) and a cognitive component (life satisfaction; Diener, 1984). Regarding the extents to which these two components are linked with BJW, most studies have reported stronger correlations between BJW and life satisfaction than between BJW and positive affect. This pattern was especially likely to be found when subjective well-being was measured as a state. This finding makes sense because BJW and life satisfaction have large trait and small state components, whereas positive affect has a large state and a small trait component. If positive affect is measured as a trait (positive affectivity), correlations with BJW that are similar to those that have been reported for life satisfaction can be expected (Correia et al., 2009a; Dalbert, 1998, 1999, 2001).

Causal Links Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being

Taken together, previous research has accumulated evidence that is consistent with the assumption that BJW is positively correlated with subjective well-being. Importantly, this evidence has been interpreted as support for the assumption that BJW has a causal impact on subjective well-being. Given the assumed functions of BJW (Dalbert, 2001), this conclusion is theoretically plausible. However, it is not yet safe to draw such a conclusion because correlations between BJW and subjective well-being have been identified exclusively in cross-sectional studies. Cross-sectional correlations between two variables X and Y are ambiguous regarding their causal nature because they can be generated by several causal processes. X may cause Y, Y may cause X, X and Y may cause each other reciprocally, or X and Y may be caused by a common factor Z that generates a spurious correlation between X and Y. Applied to our research question, the correlation between BJW and subjective well-being can be generated by several causal processes. BJW may promote subjective well-being, subjective well-being may promote BJW, BJW and subjective well-being may affect each other reciprocally, or BJW and subjective well-being may both depend on a common factor, such as optimism or positive illusions. Each of these causal processes would generate a correlation between BJW and subjective well-being. Therefore, all correlations between BJW and subjective well-being that have been found in previous cross-sectional studies remain causally ambiguous.

Correia et al. (2009a) addressed this important issue of the causal ambiguity of cross-sectional correlations between BJW and subjective well-being. They acknowledged that BJW might promote subjective well-being (original hypothesis). Yet they also deemed it theoretically feasible that subjective well-being might promote BJW (alternative hypothesis) via mood-congruent information processing (Baumert & Schmitt, 2012; Bower, 1991; Rusting, 1998; Schwarz, 1990). Happy people have a more optimistic view on life than unhappy people, and this perceptual readiness might include incidents of potential injustice. Moreover, happy people might have better memories for just events in comparison with unjust events (Blaney, 1986). Due to both of these processes (i.e., perceptual selectivity and selective memory), over time, happy people might come to the conclusion that justice prevails after all. Correia et al. (2009a) argued that the original hypothesis (BJW causes subjective well-being) and its counterpart (subjective well-being causes BJW) can be pitted against each other only in experimental and longitudinal research. Correia et al. (2009a) as well as Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) employed the experimental strategy, whereas we employed both strategies. We replicated and extended Correia et al.’s (2009a) and Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) experiments in Study 1 and investigated the longitudinal association between BJW and subjective well-being in Study 2.

Correia et al.’s (2009a) Studies

Answering their own call for research that is informative regarding the causal relationship between BJW and subjective well-being, Correia et al. (2009a) conducted three studies. Study 1 used Velten’s (1968) mood induction technique to manipulate affect. In addition to the positive and negative mood conditions, the design included a control condition without any mood manipulation. Mood induction was followed by a manipulation check and the assessment of general BJW and personal BJW as dependent variables. During the assessments of both variants of BJW, participants in the positive versus negative mood condition listened to happy versus sad music, respectively. Despite successful mood induction and sufficient power for detecting small effects, no significant differences in general BJW or personal BJW were found between the mood conditions. However, the predicted order of means was confirmed such that general BJW and personal BJW were stronger in the positive than in the negative mood condition.

Study 2 manipulated life satisfaction by instructing participants to recall either positive or negative life events. Unlike Study 1, Study 2 did not include a control condition. A manipulation check indicated that the manipulation was successful, and it significantly affected both dependent variables. General BJW and personal BJW were higher in the positive than in the negative life satisfaction condition.

Study 3 manipulated BJW by telling participants that a master’s degree would versus would not guarantee a successful professional career. Because participants were undergraduates, this information could affect personal BJW. It could also affect general BJW if participants generalized the information beyond their major. Study 3 did not include a control condition. Positive affect and life satisfaction served as the dependent variables. Life satisfaction was significantly higher in the just world condition than in the unjust world condition. Positive affect did not differ between the two conditions. Taken together, the results of the three experiments suggest a reciprocal causal relationship between BJW and life satisfaction. In other words, BJW affected life satisfaction (original hypothesis) but is was also affected by life satisfaction (alternative hypothesis).

Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) Studies

Recently, Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) replicated Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 3 in two separate studies. Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) were primarily interested in the mechanisms that might explain why personal BJW promotes subjective well-being. Their central hypothesis was that personal BJW increases positive affect and decreases negative affect because BJW is empowering.

In Study 3, the manipulation of BJW was similar to what Correia et al. (2009a) used in their Study 3. Personal BJW was affirmed by having participants read an article asserting that university graduates enjoy career success, a high income level, and overall high life satisfaction. Personal BJW was disaffirmed by having participants read an article claiming that university graduates enjoy only moderate levels of career success, income, and life satisfaction. Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) acknowledged that this manipulation might affect not only personal BJW but also general BJW. Therefore, general BJW was included as a covariate. Study 3 did not include a control condition. After participants were exposed to the articles, manipulation success, empowerment, positive affect, and negative affect were assessed. The manipulation of personal BJW was successful. Moreover, it affected empowerment as well as positive and negative affect. In line with the authors’ central hypothesis, empowerment partially mediated the effect of personal BJW on positive and negative affect.

In Study 4, personal BJW was manipulated as in Study 3. Different from Study 3, empowerment was not measured as a mediator variable but was manipulated to more rigorously test its causal impact on subjective well-being. The effects of Personal BJW x Empowerment interaction on positive and negative affect were partially unexpected and complex. Important for the present context, the effects of affirming versus disaffirming personal BJW on positive and negative affect found in Study 3 were replicated in Study 4.

Hypotheses and Empirical Evidence of Their Validity

The causal relationships between BJW and subjective well-being that guided Correia et al.’s (2009a), Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023), and the present research, can be translated into eight hypotheses.

H1a

Positive affect promotes general BJW.

H1b

Positive affect promotes personal BJW.

H1c

Life satisfaction promotes general BJW.

H1d

Life satisfaction promotes personal BJW.

H2a

General BJW promotes positive affect.

H2b

General BJW promotes life satisfaction.

H2c

Personal BJW promotes positive affect.

H2d

Personal BJW promotes life satisfaction.

The first four hypotheses reflect the original assumption that BJW is a resource that enhances subjective well-being. The second four hypotheses reflect the alternative rationale that subjective well-being nourishes BJW.

Correia et al.’s (2009a) research provided empirical support for H1c, H1d, and either H2b or H2d or both depending on which variant of BJW was manipulated in their Study 3. H1a, H1b, H2a, and H2c were not supported. Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) tested only H2a or H2c or both depending on which variant of BJW was affirmed versus disaffirmed in their Studies 3 and 4.

Given the inconsistent support for H2a or H2c or both and the related question of which variant of BJW was manipulated in Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 3 and Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) Studies 3 and 4, further research is needed. In addition to further experimental evidence, evidence from longitudinal research is needed but has not yet been provided to our knowledge.

The Present Research

The research we present here addressed both desiderata. Study 1 tested H1a through H2d experimentally. Study 2 tested H1a and H2a longitudinally and explored the longitudinal associations between additional variants of BJW (belief in an unjust world, belief in ultimate justice, belief in immanent justice) and subjective well-being. Parts of our research are replications, parts are modifications and improvements over previous experiments, and parts are entirely novel. Specifically, our research goes beyond previous research in several ways.

-

Our research is the first to combine experimental and longitudinal methodology to test the causal relationship between BJW and subjective well-being.

-

Different from Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 3 and Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) Studies 3 and 4, our Experiments 3 and 4 manipulated general BJW and personal BJW separately in order to test their unique effects on subjective well-being.

-

Different from Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) studies and in line with Correia et al.’s (2009a) studies, our studies tested the effect of BJW on cognitive well-being (life satisfaction) and emotional well-being (positive affect).

-

Different from Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) studies and in line with Correia et al.’s (2009a) studies, our studies tested not only effects of BJW on well-being (original hypothesis) but also effects of well-being on BJW (alternative hypothesis).

-

Different from Correia et al.’s (2009a) studies and Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) studies, we explored variants of BJW that have previously not been associated with subjective well-being although such associations are theoretically plausible.

-

Different from Correia et al.’s (2009a) Studies 2 and 3 and Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) Studies 3 and 4, our experimental manipulations always included a neutral condition. Such a neutral condition increases the construct validity of the manipulation because it allows for a stricter test of manipulation success and a stricter test of substantive hypotheses. A neutral condition provides a stricter test because its effects on the manipulation check measures and the dependent variables can be expected to be weaker than the effects of the conditions that manipulate the independent variable. This expectation can be tested, and if confirmed, it affirms the construct validity of the experimental design.

Study 1

Overview

Four experiments were conducted to test H1a through H2d. Experiment 1 tested H1a and H1b, Experiment 2 tested H1c and H1d, Experiment 3 tested H2a and H2b, and Experiment 4 tested H2c and H2d.

Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 1 served as the blueprint for our experiments because it had two important strengths. First, its design included a control condition in addition to the two experimental conditions. For reasons explained earlier, control conditions increase the construct validity of experimental designs. Second, Correia et al. (2009a) addressed the issue of power in their Study 1. According to their power calculation, N = 96 participants “produced a power of .87 to detect a small effect, percentage of variance explained (PV) = 9%, with a 0.05 significance criterion” (p. 223). Our a priori power analysis for the omnibus F test of a one-way ANOVA with three between-subjects conditions recommended N = 159 participants for the detection of a medium-sized effect (f = 0.25; α = 0.05; power = 0.80; k = 3; Faul et al., 2009). We recruited this number of participants for each experiment. Due to experimental attrition, the final samples were smaller but always larger than the sample used in Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 1.

We tested our hypotheses with a one-way ANOVA. Because the power of the F tests was lower than desired due to experimental attrition, we additionally contrasted the means of the two experimental conditions with one-tailed t tests. This procedure increased power and was acceptable because our hypotheses were directional. As two dependent variables were measured in each experiment, we applied Holm-Bonferroni corrections to control the family-wise error rate.

Participants were invited via email from the list of total members of a German university as well as via two survey platforms (empirio, SurveyCircle) and Facebook. All experiments were conducted online with SoSci Survey (Leiner, 2019). Data were analyzed with IBM-SPSS Statistics 25. All raw data, experimental procedures, and SPSS syntax files are available as open source material (OSF | Causal Relationships Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being).

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 tested H1a and H1b: Positive affect promotes general BJW and personal BJW.

Method

Design, Sample, and Procedure

We included three experimental conditions (positive affect, negative affect, control). Of the individuals who agreed to participate, 122 (67 female; Mage = 26.7, SDage = 9.5) completed the experiment (actual power of the F test = 0.68; actual power of the one-tailed t test = 0.70).

To manipulate affect, we used the German version of the Velten (1968) mood induction procedure. In the positive affect condition, participants read 40 positive statements, first silently, then aloud. While reading the statements, participants listened to Mozart’s Kleine Nachtmusik. In the negative affect condition, participants read 40 negative statements and listened to Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Both pieces were used in Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 1. Participants in the control condition read neutral statements and did not listen to music.

Measures

The good versus bad mood items from the short version of the Multidimensional Mood Questionnaire (Steyer, Schwenkmetzger, Notz, & Eid, 1997; 12 items; e.g., “unhappy”; 6-point rating scale: 0 = not at all to 5 = completely; alpha = 0.92) served as a manipulation check measure. General BJW was measured with Dalbert et al. (1987) scale (six items; e.g., “I think the world is basically a just place”; 6-point rating scale: 0 = not at all true to 5 = completely true; alpha = 0.92). Personal BJW was measured with Dalbert’s (1999) scale (seven items; e.g., “I am usually treated fairly”; 6-point rating scale: 0 = not at all true to 5 = completely true; alpha = 0.96). Scale scores were computed as average item scores here as well as in Experiments 2, 3, and 4.

Results

Table 1 provides the results of the manipulation check. The means of positive affect differed across the conditions in the expected order (positive affect > control > negative affect). The F test was not significant, but the directional t test contrasting the positive against the negative affect condition was.

Table 1 also presents the results of the tests of H1a and H1b. The means of general BJW and personal BJW differed across the conditions in the expected order (positive affect > control > negative affect). The F test for general BJW was not significant, but the directional t test contrasting the positive against the negative affect condition was. The same result was obtained for personal BJW. Thus, H1a and H1b were empirically supported but only when the positive and negative affect conditions were pitted directly against each other.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 tested H1c and H1d: Life satisfaction promotes general BJW and personal BJW.

Method

Design, Sample, and Procedure

We included three experimental conditions (high life satisfaction, low life satisfaction, control). Of the individuals who agreed to participate, 124 (74 women; Mage = 26.6; SDage = 8.8) completed the experiment (actual power of the F test = 0.69; actual power of the one-tailed t test = 0.73).

Participants in the high (vs. low) life satisfaction condition were asked to remember and vividly imagine seven happy (vs. unhappy) life events. Participants in the control condition were asked to remember their last seven meals.

Measures

A German version (Schumacher, 2003) of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larson, & Griffin, 1985) served as a manipulation check measure (five items; e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”; 7-point rating scale: 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.83). General BJW (α = 0.84) and personal BJW (α = 0.95) were assessed as in Experiment 1.

Results

Table 1 presents the results of the manipulation check. The means of life satisfaction differed across the conditions in the expected order (high life satisfaction > control > low life satisfaction). The F test and the directional t test (contrasting the high against the low life satisfaction condition) were significant.

Table 1 also presents the results of the tests of H1c and H1d. The means of general BJW and personal BJW differed across the conditions in the expected order (high life satisfaction > control > low life satisfaction). The effect of life satisfaction on general BJW was significant according to both the F test and the directional t test contrasting the high against the low life satisfaction condition. The same pattern was observed for personal BJW. Thus, hypotheses H1c and H1d were empirically supported.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 tested H2a and H2b: General BJW promotes positive affect and life satisfaction.

Method

Design, Sample, and Procedure

We included three experimental conditions (high general BJW, low general BJW, control). Of the individuals who agreed to participate, 127 (84 women; Mage = 26.8; SDage = 8.2) completed the experiment (actual power of the F test = 0.70; actual power of the directional t test = 0.74).

We adopted the manipulation of BJW from Correia et al.’s (2009a) Study 3, but we modified it because the manipulation that Correia et al. (2009a) and Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) used might have affected general and personal BJW. Our (German) participants read an article about bachelor’s degree programs in the US. In the high (vs. low) general BJW condition, the article cited a report suggesting that the time, money, and effort students invest in a bachelor’s degree pays off (vs. does not pay off) in terms of career opportunities. Participants in the control condition read an article about a rare kind of giraffe.

Measures

General BJW (alpha = 0.92), positive affect (alpha = 0.95), and life satisfaction (alpha = 0.93) were measured as in Experiments 1 and 2.

Results

Table 1 provides the results of the manipulation check. The means of general BJW differed across the conditions in the expected order (high general BJW > control > low general BJW). The F test and the directional t test (contrasting the high against the low general BJW condition) were significant.

Table 1 also presents the results of the tests of H2a and H2b. The means of positive affect and life satisfaction differed across the conditions in the expected order (high general BJW > control > low general BJW). General BJW had a significant impact on life satisfaction (when contrasting the high against the low general BJW condition with the directional t test) but not on positive affect.

Experiment 4

Experiment 4 tested H2c and H2d: Personal BJW promotes positive affect and life satisfaction.

Method

Design, Sample, and Procedure

We included three experimental conditions (high personal BJW, low personal BJW, control). Of the individuals who agreed to participate, 123 (78 women; Mage = 25.9, SDage = 7.6) completed the experiment (actual power of the F test = 0.69; actual power of the directional t test = 0.71).

The manipulation of personal BJW was similar to the manipulation of general BJW in Experiment 3 with the only but crucial difference being that the article was not about bachelor programs at U.S. universities but about bachelor programs at German universities. To increase concern, the article was supplemented by a quote from a student who was enrolled at the same university where most of the students who were participating in the experiment were enrolled.

Measures

Personal BJW (alpha = 0.91), positive affect (alpha = 0.96), and life satisfaction (alpha = 0.91) were measured as in Experiments 1 and 2.

Results

Table 1 provides the results of the manipulation check. The means of personal BJW differed across the conditions in the expected order (high personal BJW > control > low personal BJW). The F test and the directional t test (contrasting the high against the low personal BJW condition) were significant.

Table 1 also presents the results of the tests of H2c and H2d. The means of positive affect and life satisfaction differed across the conditions in the expected order (high personal BJW > control > low personal BJW). Personal BJW had a significant impact on life satisfaction but not on positive affect. These results mirror the results from Experiment 3 for general BJW. Accordingly, H2c was empirically supported but H2d was not.

Discussion

Summary of Findings and Conclusions

Table 2 summarizes the findings from Study 1 along with Correia et al.’s (2009a) and Bartholomaeus et al.’s (2023) findings. Three important conclusions can be drawn from Table 2. First, results on the relationship between BJW and emotional well-being (positive affect) were less consistent than the results on the relationship between BJW and cognitive well-being (life satisfaction). Second, the distinction between general BJW and personal BJW seemed less relevant for their causal relationships with subjective well-being than assumed in previous studies that were based on cross-sectional correlations. Third and important for our central research interest, the available evidence implies that the causal relationship between BJW and subjective well-being is reciprocal. This finding is important because the cross-sectional correlations between BJW and subjective well-being have always been attributed to a causal effect of BJW on subjective well-being. The findings summarized in Table 2 suggest that this one-sided view is incomplete.

Limitations

Our experiments were slightly underpowered even when we tested our hypotheses via one-tailed t tests contrasting the high versus low conditions directly against each other. Although the limited power impaired the robustness of our findings, it did not render them worthless for several reasons. First, power is an issue only when the null hypothesis cannot be rejected (i.e., in two out of eight cases in Study 1). Second, Table 2 shows that all hypotheses were empirically supported by at least one study. Third, in our research, the conditional means of the dependent variables always differed in the expected order (IV high > control > IV low). The probability that such a pattern would come about by mere chance is extremely small: p = (1/3!)8 = 0.000006. Fourth, the limited power of our experiments was counterbalanced by the control condition that was included in all experiments. This feature contributed to the construct validity of the design: The means of all dependent variables including the manipulation check measures were always smaller in the control condition than in the high IV (independent variable) condition and always larger than in the low IV condition. This fully consistent pattern suggests not only that our manipulations worked as intended but also that the nonsignificant effects are not zero in the population but smaller in size than the effects that turned out to be statistically significant. Power calculations in future studies that are intended to replicate our set of experiments should therefore assume small effects instead of the medium-sized effects we assumed.

Study 2

Overview

Study 2 used longitudinal data to address the causal relationship between BJW and subjective well-being. This strategy was recommended by Correia et al. (2009a) but has never been employed to our knowledge. We reanalyzed data from a survey on the social and psychological transformation of the German population after the German reunification in 1990. Several findings from this research have been published previously (Fischer et al., 2007; Koschate, Hoffmann, & Schmitt, 2012; Maes & Schmitt, 1999; Orth et al., 2009; Schmitt & Maes, 1998, 2002; Schmitt et al., 2009). However, longitudinal associations between BJW and subjective well-being were analyzed in the current study for the first time.

The available data allowed us to test H1a, H1c, H2a, and H2b on associations between general BJW and subjective well-being. The remaining hypotheses (H1b, H1d, H2c, H2d) could not be tested because personal BJW was introduced into the literature by Lipkus et al. (1996) and Dalbert (1999) after our study had been planned and after we had already begun collecting the data. However, personal BJW was measured at the last occasion of measurement. Therefore, we were able to compute cross-sectional correlations between personal BJW and subjective well-being.

In addition to testing H1a, H1c, H2a, and H2b, we investigated longitudinal associations between the BJW variants introduced earlier (belief in an unjust world, belief in ultimate justice, and belief in immanent justice). Because this part of our study was exploratory, we describe it in the Online Supplement and report only the most important findings here (OSF | Causal Relationships Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being).

Method

Design and Sample

Data were collected at three occasions of measurement (T1, T2, and T3) 6, 8, and 10 years after the German reunification (1996, 1998, 2000). Participants were recruited on the basis of a geographical division of Germany into 18 regions (East/West x North/Middle/South x Large Cities/Medium-Sized Cities/Small Cities). The registration offices of two cities from each region provided random samples of inhabitants between 15 and 75 years of age. Additional respondents were recruited randomly from electronic telephone directories. The present analysis was based on 2,455 ≤ N ≤ 2,523 (T1), 1,290 ≤ N ≤ 1,339 (T2), and 886 ≤ N ≤ 895 (T3) participants who provided valid measures of the constructs. The mean age of the sample at T1 was M = 57 years (SD = 16), and 60% of the participants were men. The sample was representative with respect to most demographic variables, but men and participants with higher education were overrepresented (Schmitt et al., 2006). The raw data are openly available (OSF | Causal Relationships Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being).

Measures

General BJW and personal BJW were measured as in Study 1. Two emotional well-being trait components were assessed: (a) Depression was measured with a modified German version of the Beck Depression Inventory (20 items; e.g., “I feel sad”; 6-point rating scale: 0 = never to 5 = almost always; Sauer et al., 2013; Schmitt & Maes, 2000). (b) Positive affectivity was measured with the Psychological Health Scale from the Trier Personality Questionnaire (19 items; e.g., “I am in a good mood”; 4-point rating scale: 0 = never to 3 = always; Becker, 1989). Life satisfaction was measured with a modified version of the Fahrenberg et al. (2000) Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (47 items; e.g., “I am satisfied with my job”; 6-point rating scale: 0 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied).

Data Analytic Strategy

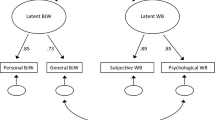

Cross-lagged panel analysis was employed to test H1a, H1c, H2a, and H2b (Kearney, 2017). Figure 1 presents the path model. It contains four types of parameters: six autoregressive effects, six cross-lagged effects, three cross-sectional correlations, and six residuals. The cross-lagged effects (e.g., of BJW at T1 on subjective well-being at T2) are relevant for our research question. These effects reflect systematic change in the dependent variable (e.g., subjective well-being) across a time period (e.g., from T1 to T2) that can be explained by the independent variable (BJW) as observed at the beginning of the time interval (T1). Different from a simple cross-lagged model that includes only first-order autoregressive and cross-lagged effects, our model also included second-order effects because cross-lagged effects might not only be short-lived but might also be long-lasting. In order to avoid spurious second-order cross-lagged effects, we had to include second-order autoregressive effects in the model as well. The inclusion of higher order autoregressive effects also solved a problem of traditional first-order only autoregressive models, which imply that the stability of the constructs will drop to zero in the long run (Orth et al., 2021).

The parameters of the model depicted in Fig. 1 were estimated via multiple regression analyses for each hypothesis and each dependent variable (Table 3). Note that Table 3 does not present results of these analyses. Results will be reported below in the Results section. Rather than reporting results, Table 3 explains how the general cross-lagged panel model (Fig. 1) was translated into specific models which reflect our hypotheses. To avoid inflating the Type I errors from multiple testing, we applied the Holm-Bonferroni adjustment to the p-values of the F tests. To avoid overfitting the model and parameter bias due to overfit, we did not estimate saturated models. Rather, we included only significant predictors that had been identified via stepwise inclusion (p < .05) and exclusion (p > .10).

Post hoc power calculations with G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) yielded power > 0.95 for detecting a medium-sized partial regression effect (f2 = 0.15, α < 0.05) and power = 0.87 for detecting a small-sized partial regression effect (f2 = 0.02, α < 0.05) for the smallest sample that was available for any of the cross-lagged regression analyses we performed.

All analyses were computed with IBM-SPSS Statistics 25. All syntax files for creating scales and for computing the descriptive statistics, correlations, and regression analyses are available as open source material (OSF | Causal Relationships Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, alpha reliability estimates) for all scales. Scale scores were computed as average item scores as in Study 1.

Correlations

Table 5 reports the correlations between all scales.

Correlations Between the Subjective Well-Being Scales

Four observations are noteworthy regarding these correlations. First, all well-being indicators were highly stable across time. Second, stability across 2 years was higher than stability across 4 years. Such a finding is typical in longitudinal studies (e.g., Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Third, the two emotional well-being scales (depression, positive affectivity) were more strongly correlated with each other than each of them was correlated with the cognitive well-being scale (life satisfaction). Fourth, all scales were substantially correlated with each other and together reflected subjective well-being as a broad construct. Despite this communality, the pattern of correlations suggested some uniqueness, especially regarding the division into cognitive and emotional well-being.

Correlations Between the BJW Scales

Three observations are noteworthy regarding these correlations. First, the stability of the general BJW scale was lower than the stability of the subjective well-being scales. To some extent, this difference reflects the lower reliability of the general BJW scale in comparison with the reliabilities of the subjective well-being scales (Table 4). Second and in line with previous research (e.g., Dalbert, 1999; Lipkus et al., 1996), personal BJW was moderately correlated with general BJW, suggesting that the two variants of BJW are distinct but also overlap to some extent. Third, the correlation between general BJW and personal BJW was highest when both were assessed at the same occasion (T3), suggesting that intraindividual change in the two BJW variants covaries.

Correlations Between the Subjective Well-Being Scales and the BJW Scales

Three observations are noteworthy regarding these correlations. First, general BJW and personal BJW were correlated with all components of subjective well-being. Second, correlations between general BJW and cognitive well-being (life satisfaction) were higher in comparison with correlations between general BJW and emotional well-being (depression, positive affectivity). The same pattern was found for personal BJW, mirroring the results from Study 1 as well as the results from Correia et al.’s (2009a) studies. Third and in line with previous research (Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2019; Goodwin & Williams, 2023; Sutton & Douglas, 2005), personal BJW was more closely associated with subjective well-being than general BJW was.

Cross-Lagged Effects

Cross-Lagged Effects of Subjective Well-Being on General BJW

Of the cross-lagged effects predicted by H1a and H1c (Models 1 and 2 in Table 4), none were significant. Depression and positive affectivity did not influence general BJW over time.

However, our exploratory analyses revealed three cross-lagged effects of subjective well-being on other variants of BJW over time (see the Online Supplement: OSF | Causal Relationships Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being). Depression at T1 had a cross-lagged effect on belief in an unjust world at T2 (β = 0.106), F(1, 1102) = 17.927, p = .00002, and at T3 (β = 0.084), F(1, 579) = 6.838, p = .009. Further, life satisfaction at T1 had a cross-lagged effect on belief in immanent justice at T2 (β = 0.084), F(1, 1096) = 5.054, p = .025.

Cross-Lagged Effects of General BJW on Subjective Well-Being

Of the six cross-lagged effects predicted by H2a and H2b (Models 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 in Table 4), none were significant. General BJW did not influence depression or positive affectivity over time.

However, our exploratory analyses revealed one effect of BJW on subjective well-being over time. Belief in an unjust world at T1 had a small cross-lagged effect on depression at T2 (β = 0.046), F(1, 1129) = 4.293, p = .033. Thus, the causal relationship between belief in an unjust world and depression turned out to be reciprocal.

Discussion

In line with many previous studies, we found cross-sectional correlations between BJW and subjective well-being. Although these correlations were not large in size, they were consistent in direction: People who believe in a just world tend to be more satisfied with their lives and happier than those who have a lower BJW.

In contrast to this consistent replication of previous cross-sectional correlations, none of our hypotheses on longitudinal associations between general BJW and subjective well-being received empirical support – despite the comparatively liberal Holm-Bonferroni adjustment to the p-values of the critical F tests. However, some BJW variants that were not part of our hypotheses but were part of our exploratory analyses were involved in significant longitudinal associations with subjective well-being. Yet only one of these associations was consistent with the original hypothesis that BJW causally affects subjective well-being: Earlier belief in an unjust world at T1 had a small cross-lagged effect on later depression at T2. Although this effect was small, it suggests that believing in an unjust world might be a risk factor for emotional well-being. More results supported the alternative hypothesis that subjective well-being affects BJW. Three cross-lagged effects were consistent with this assumption, and each was stronger than the effect of believing in injustice on later depression. Specifically, earlier depression (T1) led to an increase in later (T2, T3) belief in an unjust world, and earlier life satisfaction (T1) led to an increase in later (T2) belief in immanent justice. The reciprocal longitudinal associations between depression and belief in an unjust world suggest that emotional well-being and believing in injustice may reinforce each other and may thus be involved in a vicious cycle.

General Discussion

Taken together, the results of our two studies support Correia et al.’s (2009a) conclusion that BJW and subjective well-being affect each other reciprocally. This conclusion seems safe because all significant effects were consistent in direction. Not a single counter-hypothetical effect was discovered. However, the effect sizes differed, and the most notable difference was between the experimental effects in Study 1 and the cross-lagged effects in Study 2. The experimental effects were more frequent and were stronger than the longitudinal cross-lagged effects. This pattern may mean that bidirectional effects between BJW and subjective well-being are not very long-lasting. It might also mean that the experimental effects were inflated by irrelevant factors, such as demand or cognitive consistency effects. Finally, it may mean that bidirectional effects between BJW and subjective well-being last for a period of time that is shorter than the 2-year interval between the occasions of measurement in Study 2.

Limitations

Although we hope that our research will be appreciated as novel and valuable, it is not flawless. The fact that we did not assess personal BJW in Study 2 at all three occasions may be the most severe limitation. This drawback was due to the fact that personal BJW was introduced into the literature by Lipkus et al. (1996) and Dalbert (1999) after our study had been planned and after the data had already been collected for the first two measurement occasions (T1, T2). Personal BJW was measured only at T3, and thus, it was too late to estimate its longitudinal associations with subjective well-being.

Next, the temporal spacing of measurement occasions in Study 2 can be questioned. We do not know whether 2-year lags are appropriate for capturing changes in BJW and subjective well-being. How to choose appropriate time lags is a severe but typical challenge in longitudinal research (Hopwood et al., 2021).

Insufficient power in Study 1 was another limitation. Power was lower than intended due to experimental attrition. However, as we argued in the Limitations section of Study 1, all the nonsignificant effects were fully consistent with the significant effects. It is extremely unlikely that these results occurred by chance. It is more likely that the nonsignificant effects exist in the population but were too small to be detected in our samples. Future replications of Study 1 should recruit samples that are large enough for small effects to be detected.

Another limitation of all experiments addressing the causal relationship between BJW and subjective well-being (Bartholomaeus et al., 2023; Correia et al., 2009a; our Study 1) is the use of the same (positive affect, life satisfaction) or similar (BJW) manipulations. Although using the same manipulations can be considered a strength from a replication perspective, it comes with the limitation that the generalizability of the effects remains uncertain.

Next, our manipulation check was limited in retrospect because we assessed only the construct that was manipulated but not related constructs that might have been affected by the manipulation as well. For example, manipulating life satisfaction by letting participants remember happy and sad life events might affect not only their life satisfaction but also their positive affect. Although this limitation is typical of experimental research, it makes it impossible not only to determine the discriminant construct validity of the manipulation but also to use mediation analysis to disentangle the multiple mechanisms that might explain the experimental effect.

A similar limitation applies to Study 2. BJW is associated with several personality traits (Nudelman, 2013) and so is subjective well-being (Diener & Lucas, 1999). We did not measure these associated traits in Study 2 and thus could not control for them. However, it is crucial to control for such traits in order to definitively determine the unique causal effects of BJW and subjective well-being on each other. It is possible, although perhaps unlikely (cf. Sutton & Douglas, 2005), that controlling for associated personality traits (e.g., neuroticism, optimism, self-efficacy) would have eliminated the few significant cross-lagged effects between BJW and subjective well-being that we reported.

Future Research

In addition to avoiding these limitations, future research on the links between BJW and subjective well-being should be experimental or longitudinal. The cross-sectional evidence is ample and consistent, and therefore, no further cross-sectional studies are needed. Our request for causally informative research applies not only to associations between BJW and subjective well-being but also to mediators of these associations and to other consequences of BJW that have been assumed.

Regarding mediators, Bartholomaeus et al. (2023) suggested that empowerment mediates the effect of BJW on emotional well-being. Their research was convincing in that empowerment was measured and manipulated. Given the reciprocal causality between BJW and subjective well-being, future experiments should also test effects of empowerment on BJW and effects of subjective well-being on empowerment. Goodwin and Williams (2023) investigated perceived control, optimism, and gratitude as meditators of the relationship between BJW and subjective well-being. Because they used cross-sectional data, the causal origins of the associations among the variables, including the mediators, remain unclear. Testing the causal direction of the mediators would require longitudinal data.

The same demand for either experimental or longitudinal research applies to other consequences of BJW (besides subjective well-being) that have been assumed in the literature, that are theoretically feasible, but that have exclusively been investigated in cross-sectional studies. Bullying may serve as an example. Several studies found that BJW was negatively associated with bullying and being bullied (Correia et al., 2009b; Donat et al., 2012, 2020). The methodological strategies we used here could be used to help test the nature of the causal relationships between these variables. It is possible that BJW not only prevents people from engaging in abusive behavior toward others or from becoming victims of such behavior. It might also be possible that those who refrain from such behavior or who do not become victims conclude from their experiences that the world they live in is just.

Change history

30 September 2023

In this article, instead of writing “Correia et al.’s (2009a)” the text reads as “Correia et al. (2009a)” and Table 3 has been updated.

References

Bartholomaeus, J., & Strelan, P. (2019). The adaptive, approach-oriented correlates of belief in a just world for the self: A review of the research. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.028.

Bartholomaeus, J., Burns, N., & Strelan, P. (2023). The empowering function of the belief in a just world for the self: Trait-level and experimental tests of its association with positive and negative affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49, 510–526.

Baumert, A., & Schmitt, M. (2012). Personality and information processing. European Journal of Personality, 26, 87–89.

Becker, P. (1989). Trierer Persönlichkeitsfragebogen (TPF) [Trier Personality Questionnaire]. Hogrefe.

Blaney, P. H. (1986). Affect and memory: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 229–246.

Bower, G. H. (1991). Mood congruity of social judgments. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Emotion and Social Judgments (pp. 31–53). Pergamon Press.

Correia, I., Batista, M. T., & Lima, M. L. (2009a). Does the belief in a just world bring happiness? Causal relationships among belief in a just world, life satisfaction and mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 61, 220–227.

Correia, I., Kamble, S. V., & Dalbert, C. (2009b). Belief in a just world and well-being of bullies, victims and defenders: A study with portuguese and indian students. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 22, 497–508.

Dalbert, C. (1998). Belief in a just world, well-being, and coping with an unjust fate. In L. Montada, & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Responses to victimizations and belief in a Just World (pp. 87–105). Plenum Press.

Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a Just World Scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12, 79–98.

Dalbert, C. (2001). The justice motive as a personal resource: Dealing with challenges and critical life events. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Dalbert, C., & Donat, M. (2015). Belief in a just world. In J. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the social & behavioral Sciences (pp. 487–492). Elsevier.

Dalbert, C., Montada, L., & Schmitt, M. (1987). Glaube an eine gerechte Welt als Motiv: Validierungskorrelate zweier Skalen [Belief in a just world as a motive: Validity correlates of two scales]. Psychologische Beiträge, 29, 596–615.

Dalbert, C., Lipkus, I. M., Sallay, H., & Goch, I. (2001). A just and an unjust world: Structure and validity of different world beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 561–577.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575).

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-Being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 213–229). Russell Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Donat, M., Umlauft, S., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2012). Belief in a just world, teacher justice, and bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 185–193.

Donat, M., Peter, F., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2016). The meaning of students’ personal belief in a just world for positive and negative aspects of school-specific well-being. Social Justice Research, 29, 73–102.

Donat, M., Rüprich, C., Gallschütz, C., & Dalbert, C. (2020). Unjust behavior in the digital space: The relation between cyber-bullying and justice beliefs and experiences. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 101–123.

Ellard, J., Harvey, A., & Callan, M. (2016). The justice motive: History, theory, and research. In C. Sabbagh, & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research (pp. 127–143). Springer.

Fahrenberg, J., Myrtek, M., Schumacher, J., & Brähler, E. (2000). Fragebogen zur Lebenszufriedenheit [Life satisfaction questionnaire]. Hogrefe.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

Fischer, R., Maes, J., & Schmitt, M. (2007). Tearing down the ‘Wall in the head’? Culture contact between Germans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 163–179.

Furnham, A. (2003). Belief in a just world: Research progress over the past decade. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 795–817.

Goodwin, T. C., & Williams, G. A. (2023). Testing the roles of perceived control, optimism, and gratitude in the relationship between general/personal belief in a just world and well-being/depression. Social Justice Research, 36, 40–74.

Hafer, C. L. (2000). Investment in long-term goals and commitment to just means drive the need to believe in a just world. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1059–1073.

Hafer, C. L., & Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: Problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 128–167.

Hafer, C. L., & Sutton, R. (2016). Belief in a just world. In C. Sabbagh, & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research (pp. 145–160). Springer.

Hopwood, C. J., Bleidorn, W., & Wright, A. G. C. (2021). Connecting theory to methods in longitudinal research. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2022, 17, 884–894.

Kearney, M. W. (2017). Cross-lagged panel analysis. In M. R. Allen (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods (pp. 312–314). Sage.

Koschate, M., Hofmann, W., & Schmitt, M. (2012). When East meets West: A longitudinal examination of the relationship between group relative deprivation and intergroup contact in reunified Germany. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 290–311.

Leiner, D. J. (2019). SoSci Survey (Version 3.1.06) [Computer software]. Available at https://www.soscisurvey.de.

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world. A fundamental delusion. Plenum Press.

Lerner, M. J., & Miller, D. T. (1978). Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1030–1051.

Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., & Siegler, I. C. (1996). The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: Implications for psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 666–677.

Maes, J. (1998). Immanent justice and ultimate justice: Two ways of believing in justice. In L. Montada, & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Responses to victimizations and belief in a Just World (pp. 9–40). Plenum Press.

Maes, J., & Schmitt, M. (1999). More on ultimate and immanent justice: Results from the research project „Justice as a problem within reunified Germany. Social Justice Research, 12, 65–78.

Nudelman, G. (2013). The belief in a just world and personality: A meta-analysis. Social Justice Research, 26, 105–119.

Orth, U., Robins, R. W., Trzesniewski, K. H., Maes, J., & Schmitt, M. (2009). Low self-esteem is a risk factor for depressive symptoms from young adulthood to old age. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 472–478.

Orth, U., Clark, D. A., Donnellan, M. B., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Testing prospective effects in longitudinal research: Comparing seven competing cross-lagged models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120, 1013–1034.

Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25.

Rusting, C. L. (1998). Personality, mood, and cognitive processing of emotional information: Three conceptual frameworks. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 165–196.

Sauer, S., Schmitt, M., & Ziegler, M. (2013). Rasch analysis of a simplified Beck Depression Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 530–535.

Schmitt, M., & Maes, J. (1998). Perceived injustice in unified Germany and mental health. Social Justice Research, 11, 59–78.

Schmitt, M., & Maes, J. (2000). Vorschlag zur Vereinfachung des Beck-Depressions-Inventars (BDI) [Proposal of a simplified Beck Depression Inventory]. Diagnostica, 46, 38–46.

Schmitt, M., & Maes, J. (2002). Stereotypic ingroup bias as self-defense against relative deprivation: Evidence from a longitudinal study of the german unification process. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 309–326.

Schmitt, M., Altstötter-Gleich, C., Hinz, A., Maes, J., & Brähler, E. (2006). Normwerte für das Vereinfachte Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI-V) in der Allgemeinbevölkerung. [Norms for the simplified Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-V) in the general population]. Diagnostica, 52, 51–59.

Schmitt, M., Maes, J., & Widaman, K. (2009). Longitudinal effects of egoistic and fraternal relative deprivation on well-being and protest. International Journal of Psychology, 44, 1–9.

Schumacher, J. (2003). Satisfaction with Life Scale. In J. Schumacher, A. Klaiberg, & E. Brähler (Eds.), Diagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und Wohlbefinden [Assessment Procedures for Quality of Life and Well-Being] (pp. 305–309). Hogrefe.

Schwarz, N. (1990). Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states. In R. Sorrentino, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior (2 vol., pp. 527–561). Guilford.

Steyer, R., Schwenkmezger, P., Notz, P., & Eid, M. (1997). Der Mehrdimensionale Befindlichkeitsfragebogen [Multidimensional Mood Questionnaire]. Hogrefe.

Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2005). Justice for all, or just for me? More evidence of the importance of the self-other distinction in just-world beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 637–645.

Sutton, R. M., & Winnard, E. J. (2007). Looking ahead through lenses of justice: The relevance of just-world beliefs to intentions and confidence in the future. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 649–666.

Velten, E. (1968). A laboratory task for induction of mood states. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 6, 473–472.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation, No. SCHM1092/1-1, SCHM1092/1-2, SCHM1092/1-3. We thank Jane Zagorski for her help in editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitt, M., Heck, L. & Maes, J. Experimental and Longitudinal Investigations of the Causal Relationship Between Belief in a Just World and Subjective Well-Being. Soc Just Res 36, 432–455 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-023-00427-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-023-00427-5