Abstract

The psychological bases of ideology have received renewed attention amid growing political polarization. Nevertheless, little research has examined how one’s understanding of political ideas might moderate the relationship between “pre-political” psychological variables and ideology. In this paper, we fill this gap by exploring how expertise influences citizens’ ability to select ideological orientations that match their psychologically rooted worldviews. We find that expertise strengthens the relationship between two basic social worldviews—competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs and left–right self-placement. Moreover, expertise strengthens these relationships by boosting the impact of the worldviews on two intervening ideological attitude systems—social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. These results go beyond previous work on expertise and ideology, suggesting that expertise strengthens not only relationships between explicitly political attitudes but also the relationship between political attitudes and their psychological antecedents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Far from fading away, ideological differences among citizens have only increased in extremity and acrimony in the present era (Hunter, 1991; Jost, 2006; Lakoff, 1996; Stimson, 2004). Given the intractable and seemingly fundamental nature of contemporary ideological disputes, social and behavioral scientists have increasingly searched for the deeper psychological roots of people’s varying political outlooks. From one angle, many social and personality psychologists have focused on how a range of “pre-political” psychological variables may predispose individuals to adopt certain ideological preferences at an explicitly political level (see Duckitt, 2001; Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003). Approaches of this sort emphasize that ideological affinities are not psychologically random, even among those with a weak understanding of politics. Rather, attraction to ideologies of the left and right is deeply rooted in orientations toward uncertainty and threat, simple worldviews, and a variety of other motives (Jost, 2006). From a second, fairly different angle, political scientists and sociologists have focused on how elites from different parties compete to construct opposing ideologies and how elite cue-giving transmits these ideologies to the mass public (Feldman, 2003; Hinich & Munger, 1994; Sapiro, 2004; Sniderman & Bullock, 2004). Brought down to the level of the individual, these perspectives emphasize that those high in political expertise—who have better-developed political knowledge structures—are more likely to learn, comprehend, and use the ideologies that originate from elite discourse (Converse, 1964; Zaller, 1992).

In this paper, we link these two modes of analysis by exploring the ways in which political expertise may influence citizens’ abilities to select ideological orientations that “correctly” match their pre-political, psychologically rooted beliefs about the social world. Specifically, we look at whether political expertise strengthens the relationship between two general social worldviews—competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs (Duckitt, 2001)—and three ideological variables—social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, and general left–right self-placement. We begin by reviewing recent work on the psychological bases of ideology.

Psychological Foundations: The Pre-Political Bases of Political Ideology

Psychologists have long argued that political preferences may be shaped by underlying psychological needs and characteristics (e.g., Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950; Allport, 1954; Eysenck, 1954, Rokeach, 1960; Wilson, 1973). However, the psychological bases of ideological affinity have received renewed attention (e.g., Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Jost, 2006; Jost et al., 2003; Jost, Federico, & Napier, 2009; Jost, Nosek, & Gosling, 2008) amid the growing political polarization of recent years over hot-button issues like the Iraq war, gay marriage, and so on (e.g., Haidt & Graham, 2007; Hunter, 1991; Lakoff, 1996). Like older perspectives on the roots of ideology, these newer approaches argue that people adopt political perspectives that best satisfy a set of epistemic, existential, and relationship-protecting motives. One recent line of work focuses on the psychological bases of the general left–right continuum and its two interrelated facets: (1) egalitarianism versus anti-egalitarianism and (2) openness versus resistance to change (Jost, 2006; Jost et al., 2003, 2007, 2008). This perspective conceptualizes ideological affinity as a form of motivated social cognition in which preferences for the left versus right are governed by situational and dispositional variables associated with the management of threat and uncertainty. Specifically, this model argues that fears about threat, loss, and social instability and needs for order, structure, and closure should be associated with conservatism, while openness to new experiences, cognitive complexity, and tolerance of uncertainty should be associated with liberalism. Confirming this, both current research and reviews of the literature find strong support for this pattern of relationships (e.g., Jost et al., 2003, 2008).

Importantly, this “motivated social cognition” model views the two aforementioned facets of the left–right distinction—egalitarianism versus anti-egalitarianism and openness versus resistance to change—as operating largely in tandem and as a function of the same underlying psychological processes. Departing somewhat from this formulation, Duckitt and his colleagues have recently proposed a dual process model that disaggregates these two facets of the left–right distinction to a greater extent and suggests that they may have different motivational foundations (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Sibley, 2009). According to this model, different personality dimensions predispose people to different sets of stable beliefs about the social world. These distinct worldviews are in turn associated with the endorsement of ideological attitude systems serving different motivational goals. For example, a personality orientation characterized by power motivation, tough-mindedness, and lack of empathy predisposes people to perceive the social world as a cut-throat competitive jungle. This belief reinforces the motivational goals of power, dominance, and superiority. These goals correspond most closely to the ideological attitude system of social dominance orientation (SDO) discussed by Sidanius and Pratto (1999), which taps one’s general preference for equality versus inequality in intergroup relations. Similarly, a personality orientation toward social conformity predisposes people to perceive the existence of a dangerous world. This belief activates motivational goals of social control and security. In turn, these goals correspond most clearly to the ideological attitude system of right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) identified by Altemeyer (1996, 1998), consisting of conventionalism, submission to ingroup authorities, and aggression toward outgroups.

Consistent with this account, Duckitt and his colleagues have found that (1) SDO and RWA are distinct ideological dimensions; (2) each one is primarily associated with a distinct set of social values; (3) each one is most strongly shaped by a particular “pre-political” worldview, i.e., competitive-jungle beliefs in the case of SDO and dangerous-world beliefs in the case of RWA; and (4) each is linked to different personality traits, e.g., low agreeableness in the case of the SDO dimension and low openness in the case of the RWA dimension (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Fisher, 2003; Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis, & Birum, 2002; Sibley, Wilson, & Duckitt, 2007; see also Altemeyer, 1998; Duriez & Soenens, 2006; Duriez, Van Hiel, & Kossowska, 2005; McFarland, 2005; Schwartz, 1992; Stangor & Leary, 2006). By extension, this model suggests that two different mediational pathways may contribute to self-placement on the general left–right dimension (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Feldman, 2003). In the first pathway, the belief that the world is a competitive jungle leads to a higher level of SDO, i.e., a willingness to maintain group hierarchy and a tendency to see inequality as justified. In turn, this orientation attracts individuals to the conservative side of the general left–right spectrum on the basis of the political right’s relative preference for hierarchy. In the second pathway, belief in a dangerous world and a concern with maintaining social order predisposes one to a higher level of RWA, which is rooted in a preference for traditionalism over social change. In turn, this orientation attracts individuals to the conservative side of the left–right spectrum on the basis of the political right’s relative preference for order, conformity, and preservationism. Thus, the two pathways highlighted by the dual process model may in fact be antecedents of the two themes that anchor the left–right distinction, i.e., egalitarianism versus anti-egalitarianism and openness versus resistance to novelty (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Weber & Federico, 2007).

In sum, current work in social and personality psychology offers a variety of models that explain the underpinnings of ideology by integrating a variety of motivational influences and personality characteristics. Nevertheless, very little of the research inspired by these new lines of inquiry has focused on how the ultimate ideological consequences of these psychological processes are conditioned by the extent to which individuals have the expertise needed to learn and understand the ideological systems constructed by political elites. As we shall soon see, this deficit is particularly notable with respect to the dual-process approach to the foundations of ideology.

Political Expertise and the Worldview-Ideology Connection

So, what implications does research on the consequences of expertise have for current psychological models of ideology? Above all, the literature on public opinion suggests that it is important to attend to the social origins and learning of the different ideologies that individuals might be motivated to adopt. Along these lines, this literature makes two particularly relevant points about ideological attitude systems (Converse, 1964, 2000; Sniderman & Bullock, 2004; Zaller, 1992). The first is that ideological attitude systems are socially constructed by a specialized minority of political elites, consisting mainly of the most prominent members of competing political parties. As such, for most citizens, ideologies are not direct products of intra-individual psychological processes; they are pre-existing social constructs chosen from a menu of political options offered by a particular political culture, even if the choice is itself shaped by various psychological processes. The second point is that the ideological attitude systems constructed by elites are learned only partially in the mass public, shaping attitudes to a much greater extent among those with high levels of political expertise.

This second point is particularly germane for an understanding of how the relationship between psychological variables and ideological affinities may be conditioned by expertise. Research on political expertise has consistently shown wide variation in knowledge not only between elites and the mass public, but also within the mass public itself (Campbell, Converse, Miller, & Stokes, 1960; Converse, 1964, 2000; Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). In fact, it seems that many citizens lack even the most fundamental knowledge about the political system, including information about figures, institutions, and democratic procedures (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). These patterns have crucial implications for how well citizens “use” ideology. For example, studies have indicated that the attitudes of most citizens are not ideologically consistent with one another or with broader predispositions (Bennett, 2006; Converse, 1964; Erikson & Tedin, 2003; Judd & Krosnick, 1989; Kinder & Sears, 1985; Luskin, 1987; Zaller, 1992). Moreover, despite the fact that at least two-thirds of adults identify themselves as liberals or conservatives, only a minority of citizens can accurately think about politics in the abstract ideological language of liberalism versus conservatism (Campbell et al., 1960; Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; Erikson & Tedin, 2003; Stimson, 2004; but see Jost, 2006, for another perspective on being “ideological”). However, research also suggests that political elites and members of the mass public with high levels of political expertise—who are more likely to have learned the ideological language elites use to discuss politics—are more likely to correctly understand and use ideologies to structure their attitudes (resulting in higher levels of ideological consistency among attitudes, a stronger tendency to conceptualize politics in ideological terms, and so on; see Campbell et al., 1960; Converse, 1964, 2000; Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; Erikson & Tedin, 2003; Federico, 2007; Federico & Schneider, 2007; Judd & Krosnick, 1989; Kinder, 2006; Lavine, Thomsen, & Gonzales, 1997; Layman & Carsey, 2002; Zaller, 1992). Thus, although various pre-political variables may play a role in citizens’ ideological affinities, it is also clear that citizens vary widely in the extent to which they understand the ideological attitude systems they have to choose from in the first place.

This raises a critical question: does political expertise condition the relationship between pre-political psychological variables and ideological preferences? While research suggests that expertise increases (1) consistency between left–right self-placement and issue positions and (2) the extent to which different issue positions are ideologically aligned with one another (e.g., Converse, 1964), the literature on political attitudes is largely silent with respect to the question of whether expertise has any influence on the relationship between ideology and its pre-political antecedents. Nevertheless, prior work on expertise suggests that people with a stronger understanding of politics and political ideas may be better able to select the ideological content that best matches their pre-political beliefs about the social world and psychological needs. In contrast, individuals with a poor understanding of politics may find it harder to appropriately identify ideological positions consistent with their psychological inclinations. In this case, we would expect the relationship between psychological variables and ideological dimensions—such as SDO, RWA, and the more generalized left–right spectrum that SDO and RWA get “mapped” onto—to be stronger among those high in expertise. According to this perspective, the added inter-attitudinal coherence provided by expertise may extend not only to variously explicitly political constructs, but also to the pre-political worldviews often thought to form the basis for ideology.

However, it is not evidently clear that expertise should influence the vertical connection between ideological attitude systems and their pre-political antecedents the same way that it influences connections between other political attitudes. In this vein, one could argue that worldviews and other generalized psychological inclinations may represent heuristic bases of political judgment that people at all levels of expertise can rely upon (Lau & Redlawsk, 2006; Popkin, 1991; see also Sniderman, Brody, & Tetlock, 1991). That is, worldviews and generalized needs may serve as simple metaphors that allow even those who do not clearly understand the “forensic” content of various ideologies and the policy preferences that they entail to make political choices that broadly accord with what they see as essential to the good life (Lakoff, 1996; Lane, 1962). Indeed, the basic assumptions about social life and human nature embedded in the worldviews highlighted by the dual-process model can be regarded as central to even the crudest political belief systems (Brewer & Steenbergen, 2002; Lane, 1962). In this case, we would expect the relationship between psychological variables and ideological continua like SDO, RWA, and the related left–right spectrum to be similar among those low and high in political expertise.

Unfortunately, only a handful of studies have explored the influence of expertise on the connection between ideology and its pre-political antecedents. Nevertheless, the studies that do exist provide suggestive evidence for the argument that expertise should strengthen the relationship between pre-political psychological variables and ideological affinity. For example, Federico and Goren (2009) recently found that political expertise strengthens the relationship between the need for cognitive closure—i.e., the extent to which an individual is motivated to possess knowledge that is secure, stable, and permanent (Kruglanski, 1996; see also Jost et al., 2003)—and generalized political conservatism. Similarly, Kemmelmeier (2007) found that cognitive rigidity better predicts conservatism among American foreign-policy officials who scored higher on an indirect measure of expertise, i.e., self-reported interest in politics.

Although instructive, these results are limited in a number of ways. First, they focus on a narrow range of psychological constructs, such as the need for closure and cognitive rigidity (e.g., see Jost et al., 2003). As such, they tell us little about how expertise may moderate the relationship between ideology and citizens’ pre-political worldviews, such as the competitive-jungle and dangerous-world beliefs highlighted by Duckitt’s (2001) dual-process model. This omission is significant, given that the two pathways emphasized by this model have been even more directly linked to intolerance than cognitive-motivational variables such as the need for closure; in fact, the competitive-jungle/SDO and dangerous-world/RWA pathways were originally proposed as explanations of prejudice, as opposed to generalized political choice (Duckitt, 2001). Because much research suggests that knowledge and sophistication tend to weaken intolerant predispositions (e.g., Allport, 1954; Christie, 1954; Lipset, 1960; Sniderman et al., 1991; Stenner, 2005), one might find different effects of expertise with respect to the impact of constructs like the worldviews emphasized by the dual-process model.

A second problem is that the aforementioned studies focus solely on one type of ideological attitude system, i.e., the generalized left–right continuum. While this dimension plays an important role in the structuring of political attitudes (Jost, 2006), so do the ideological systems represented by SDO and RWA. In fact, they can be thought of as key antecedents of the two concerns that anchor the left–right distinction, i.e., egalitarianism versus anti-egalitarianism and openness versus resistance to change (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Jost et al., 2003). This implies that any tendency for expertise to strengthen the relationship between pre-political worldviews and left–right self-placement may be mediated by its intervening tendency to strengthen the relationship between worldviews and SDO and RWA. Therefore, it is also important to look at the impact of expertise on the extent to which people’s worldviews can predict each of these ideological attitude systems, i.e., competitive-jungle beliefs in the case of SDO and dangerous-world beliefs in the case of RWA.

Research Questions

In an effort to address these gaps in the extant literature, the present study examined the possibility that expertise may moderate the relationship between endorsement of the two pre-political worldviews central to Duckitt’s (2001) dual-process model,i.e., competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs,and three ideological attitude systems, i.e., SDO, RWA, and the general left–right dimension. Specifically, we examine two primary questions:

-

(1)

Does expertise strengthen the relationship between each worldview and the ideological attitude system it is typically associated with (i.e., SDO in the case of competitive-jungle beliefs and RWA in the case of dangerous-world beliefs), or do the worldviews have similar effects across expertise levels?

-

(2)

Does expertise strengthen the relationship between each worldview and self-placement on the more general left–right dimension, or do the worldviews have similar effects across expertise levels?

Moreover, in light of the possibility that SDO and RWA may be precursors of the concerns that determine one’s location on the general left–right spectrum—i.e., egalitarianism versus anti-egalitarianism and openness versus resistance to change—we examine one other question:

-

(3)

Is the interactive effect of each worldview and expertise on left–right self-placement mediated by the intervening effects of these interactions on SDO and RWA?

Method

Participants

The data for this study came from a survey of undergraduates enrolled in psychology courses at a large Midwestern university (N = 288). All participants received either extra credit or $5 as compensation. Participants were recruited for mass-testing sessions by class announcements, online advertisements on the Psychology Department website, and flyers posted in university buildings. All participants read and signed a consent form before completing the survey individually. The sample was composed of 122 men and 166 women with a mean age of 20 years (SD = 4.27). Of these, 76.7% were Caucasian, 15.7% were Asian-American, 2.8% were African-American, 1% were Latino, and 1% were Native American; 2.8% classified themselves as “other.” Broken down by political affiliation, 49.5% identified themselves as Democrats, 21.2% identified themselves as independents, and 29.3% identified themselves as Republican.

Measures

Measures of our key study variables are described below. Unless otherwise indicated, all items used a seven-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Competitive-Jungle Beliefs

We measured respondents’ tendency to believe that the word is a ruthless “competitive jungle” using a 13-item version of Duckitt’s (2001) Competitive Jungle Scale (see Weber & Federico, 2007). Sample items included: “It’s a dog-eat-dog world where you have to be ruthless at times” and “Winning is not the first thing; it’s the only thing.” All items were recoded to indicate a stronger belief that the world is a competitive jungle and then averaged to form a composite (α = .85, M = 2.88, SD = .93).

Dangerous-World Beliefs

We measured people’s basic tendency to view the world as dangerous and threatening using the 10-item scale developed by Duckitt (2001). Sample items included: “My knowledge and experience tells me that the social world we live in is basically a dangerous and unpredictable place, in which good, decent, and moral people’s values and way of life are threatened and disrupted by bad people” and “There are many dangerous people in our society who will attack somebody out of pure meanness, for no reason at all.” All items were recoded to indicate stronger dangerous-world beliefs and then averaged to form a composite (α = .74, M = 3.75, SD = .76).

Social Dominance Orientation

SDO was measured using the full 16-item Social Dominance Orientation Scale (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Sample items included: “Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups,” “We would have fewer problems if we treated people more equally” (reverse coded), and “To get ahead in life, it’s sometimes necessary to step on other groups.” All items were recoded so that higher numbers corresponded to higher levels of SDO and then averaged to form a composite (α = .91, M = 2.87, SD = 1.09).

Right-Wing Authoritarianism

RWA was measured using a shortened 12-item version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale comprising of items that have appeared consistently on successive versions of the instrument (see Altemeyer, 1996; Weber & Federico, 2007). Sample items included: “Obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children can learn,” “The courts are right on being easy on drug users. Punishment would not do any good in cases like these” (reverse coded), and “It may be considered old-fashioned by some, but having a decent, respectable appearance is still the mark of a gentleman and, especially, a lady.” All items were recoded so that higher numbers indicated higher RWA and then averaged to form a single composite (α = .77, M = 3.99, SD = .91).

Political Expertise

Expertise was measured using standard factual items, which are regarded as the most valid indicators of expert–novice differences in political cognition and awareness of elite discourse (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; Fiske, Lau, & Smith, 1990; Zaller, 1992). Eleven items were used: “What job or political office does Dick Cheney hold?”; “What job or political office does John Roberts hold?”; “What job or political office does Nancy Pelosi hold?”; “What job or political office does Kim Jong-il hold?”; “What job or office does Samuel Alito hold?”; “What job or political office does Norm Coleman hold?”“What job or political office does Russ Feingold hold?”; “Which political party currently has the most members in the Senate in Washington, D.C.?”; “Which political party currently has the most members in the House in Washington, D.C.?”; “How long is the term of office for a U.S. Senator?”; and “Whose job is it to nominate justices to the Supreme Court?” Responses to all items were scored on a 0/1 basis, such that 0 indicated no answer or an incorrect answer and 1 indicated a correct answer. Each participant’s scores on the 11 items were averaged to create a single overall index of political expertise ranging from 0 to 1 (α = .76; M = .43, SD = .24).

Left–right Self-Placement

We operationalized the key dependent variable using two standard seven-point ideology items. The two items were: “How would you describe your political outlook with regard to economic issues?” and “How would you describe your political outlook with regard to social issues?” Participants responded to both items on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (very liberal) to 7 (very conservative). The two items were correlated at r = .58, p < .001, so they were averaged to form a single composite measure of left–right self-placement (α = .72; M = 3.60, SD = 1.41).

Results

Intercorrelations between the variables are shown in Table 1. Expertise was related only to dangerous-world beliefs and RWA. Consistent with the notion that authoritarianism is a belief system of the “unsophisticated” (Altemeyer, 1996; Christie, 1954), both of these correlations were negative (r = −.25, with dangerous world; and r = −.26, with RWA). As expected, correlations between the other variables were all significant (all ps at least < .01). Consistent with previous work (Duckitt, 2001), competitive-jungle beliefs were more strongly related to SDO (r = .67) than to RWA (r = .22), and dangerous-world beliefs were more strongly related to RWA (r = .38) than to SDO (r = .16). Finally, left–right self-placement was slightly more related to competitive-jungle beliefs (r = .27) than to RWA (r = .18) and more related to RWA (r = .53) than to SDO (r = .39).

Political Expertise, Worldviews, and Ideological Attitude Systems: Effects on SDO and RWA

Extant work suggests that each of the two aforementioned worldviews relates more specifically and proximally to a particular ideological attitude system: i.e., SDO in the case of competitive-jungle beliefs and RWA in the case of dangerous-world beliefs (e.g., Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt et al., 2002). If so, expertise may moderate the relationship between each pre-political worldview and its associated ideological attitude system, i.e., the relationship between competitive-jungle beliefs and SDO and the relationship between dangerous-world beliefs and RWA. To examine this possibility, we estimated a pair of nested ordinary least-squares regression models for each of the two worldviews. In the first pair of models, SDO was regressed on competitive-jungle beliefs, dangerous-world beliefs, expertise, and the Competitive Jungle × Expertise interaction; in the second pair of models, RWA was regressed on competitive-jungle beliefs, dangerous-world beliefs, expertise, and the Dangerous World × Expertise interaction. In these models, coefficients for the interactions between expertise and each worldview test the hypothesis that expertise should moderate the impact of the worldviews. Expertise and the worldview variables were centered prior to the analyses (Aiken & West, 1991). Finally, as recommended by Long and Ervin (2000), as a general precaution in linear regression—even where heteroskedasticity is not explicitly suspected—HC3 robust standard errors were used in all analyses.

Results for the competitive-jungle/SDO analysis are summarized in Table 2. Model 1 examined the main effects of the two worldviews and expertise. Consistent with prior work (Duckitt et al., 2002), those who strongly believed the world to be a competitive jungle were higher in SDO (b = .79, p < .001), while those who endorsed dangerous-world beliefs were not (p > .50). Moreover, expertise was unrelated to self-placement on the SDO dimension (p > .50). In turn, Model 2 added the Competitive Jungle × Expertise interaction. This interaction was positive and significant (b = .44, p < .05). We probed this interaction by computing simple slopes for the relationship between competitive-jungle beliefs and SDO one standard deviation above and below the mean of expertise (Aiken & West, 1991). These post hoc analyses indicated that the tendency to see the world as a competitive jungle significantly related to SDO at both high and low expertise. However, consistent with the hypothesis that expertise would strengthen the influence of pre-political variables, the competitive-jungle dimension was more strongly related to SDO when expertise was high (b = .90, SE = .07, p < .001) than when expertise was low (b = .68, SE = .07, p < .001).

Similar results for the dangerous-world/RWA analysis are shown in Table 3. Model 1 examined the main effects of the two worldviews and expertise. Again confirming prior results, those who believed the world to be dangerous were higher in RWA (b = .38, p < .001); similarly, those who saw the world as a competitive jungle were also higher in RWA, but this effect was smaller, as one would expect (b = .16, p < .01). Expertise was also negatively related to RWA (b = −.66, p < .001), again suggesting that authoritarianism declines with sophistication. Model 2 added the Dangerous World × Expertise interaction to the equation. This interaction was positive and significant (b = .41, p = .05). This significant interaction was broken down by computing simple slopes one standard deviation above and below the mean of the expertise variable. As with competitive-jungle beliefs and SDO, these analyses indicated that dangerous-world beliefs were significantly related to RWA at all levels of expertise. However, the dangerous-world dimension was more strongly related to RWA when expertise was high (b = .46, SE = .08, p < .001) than when it was low (b = .26, SE = .10, p < .01).

Thus, our first set of analyses provided a consistent pattern of support for the hypothesis that expertise would strengthen the linkage between two pre-political worldviews—competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs—and self-placement along the two ideological attitude dimensions of SDO and RWA. As such, expertise does appear to strengthen the ability to connect generalized psychological inclinations with the “correct” ideological orientations.

Political Expertise, Worldviews, and Left–Right Self-Placement

The preceding results suggest that expertise strengthens the relationship between each pre-political worldview and its associated ideological attitude system. As noted previously though, the competitive-jungle/SDO and dangerous-world/RWA pathways should also have downstream effects on the more general ideological dimension of left–right self-placement. Therefore, we also looked at whether the relationship between two worldview variables emphasized in Duckitt’s (2001) dual process model—competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs—and the even more explicitly political variable of left–right self-placement is moderated by political expertise. We examined these additional predictions in three more OLS regressions. Estimation procedures for these models were identical to those used in the SDO and RWA analyses. Again, coefficients for the interactions between expertise and each worldview test the hypothesis that expertise should moderate the impact of the worldviews on left–right self-placement.

The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 4. Model 1 examined the main effects of two worldviews and expertise. As might be expected, those who strongly believed the world to be a competitive jungle were more politically conservative (b = .44, p < .001), and to a lesser extent, so were those who believed the world to be dangerous (b = .22, p < .05). Moreover, expertise was essentially unrelated to left–right self-placement (p > .50). In turn, Model 2 added the Competitive Jungle × Expertise interaction to the equation. This interaction was positive and significant (b = .86, p < .01), suggesting that the relationship between competitive-jungle beliefs and conservatism was more pronounced among those higher in expertise. To probe this interaction, we computed simple slopes for the relationship between competitive jungle beliefs and left–right self-placement one standard deviation above and below the mean of expertise. These analyses indicated that competitive jungle beliefs were strongly related to conservatism when expertise was high (b = .61, SE = .12, p < .001) but not when expertise was low (b = .19, SE = .13, p > .15).

Finally, Model 3 added the Dangerous World × Expertise interaction to Model 1. This interaction was positive and significant (b = .85, p < .01), suggesting that the relationship between dangerous-world beliefs and political conservatism was stronger among those with high levels of expertise. In order to unpack this interaction, simple slopes for the relationship between dangerous-world beliefs and left–right self-placement were computed at expertise levels one standard deviation above and below the mean of the latter variable. These analyses indicated that the tendency to see the world as a dangerous place was strongly related to conservatism when expertise was high (b = .41, SE = .13, p < .01) but not when expertise was low (b = −.01, SE = .15, p > .75).

Thus, paralleling our results for the specific ideological attitude dimensions of SDO and RWA, we find that political expertise strengthens the relationship between the pre-political competitive-jungle and dangerous-world dimensions, on one hand, and the more general ideological dimension of left–right self-placement, on the other.

Mediated-Moderation Analyses

Finally, our hypotheses suggest that the tendency for expertise to strengthen the relationship between each pre-political worldview and the generalized dimension of left–right self-placement should be mediated by the tendency for expertise to strengthen the relationships between the worldviews and the two specific dimensions of ideological attitudes, i.e., SDO and RWA, which influence left–right self-placement. In statistical terms, our hypotheses imply a pattern of mediated moderation in which the effect of the Competitive Jungle × Expertise interaction on left–right self-placement is mediated by SDO and the effect of the Dangerous World × Expertise on left–right self-placement is mediated by RWA (Baron & Kenny, 1986). With respect to our data, three conditions must be met for the hypothesis of mediated moderation to receive support: (1) each worldview must interact with expertise to predict left–right self-placement; (2) each worldview must interact with expertise to predict the appropriate mediator, i.e., SDO in the case of competitive-jungle beliefs and RWA in the case of dangerous-world beliefs; and (3) in final models predicting left–right self-placement, the interaction between expertise and each worldview must be significantly reduced in magnitude when the relevant mediator (i.e., SDO for competitive jungle or RWA for dangerous world) is added to the model, and the mediator itself must have a significant coefficient (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Wegener & Fabrigar, 2000).

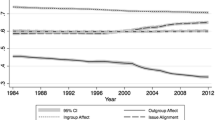

The mediated-moderation analyses are summarized in Fig. 1 for the effects of competitive-jungle beliefs and SDO and in Fig. 2 for dangerous-world beliefs and RWA; main effect terms for expertise and the relevant worldview are included in the regressions but not shown in the figures. In both sets of analyses, the estimates summarized in Table 4 meet the first criterion; they indicate significant interactive effects of each worldview and expertise on left–right self-placement. In turn, the second criterion is satisfied by the results shown in Tables 2 and 3; these indicate significant interactive effects of each worldview and expertise on the relevant mediating ideological attitude dimension—SDO in the case of competitive-jungle beliefs and RWA in the case of dangerous-world beliefs. Finally, the third criterion was examined by (1) adding SDO to Model 2 from Table 4, in which left–right self-placement was regressed on the two worldviews, political expertise, and the Competitive Jungle × Expertise interaction, and (2) adding RWA to Model 3 from Table 4, in which left–right self-placement was regressed on the two worldviews, political expertise, and the Dangerous World × Expertise interaction.

Looking first at the competitive-jungle/SDO results in Fig. 1, the mediator, SDO, had a significant effect on left–right self-placement (b = .47, p < .001) and the interaction was reduced from b = .86 (p < .01) to b = .63 (p < .10).Footnote 1 We then used a bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) to estimate the indirect effect of the Competitive Jungle × Expertise interaction on left–right self-placement via SDO. Confirming our expectations, this analysis indicated a significant indirect effect (I.E. = .21, with a 95% confidence interval of .03-.45).Footnote 2 Turning to the dangerous-world/RWA results in Fig. 2, the mediator, RWA, had a significant effect on left–right self-placement (b = .79, p < .001) and the interaction was reduced from b = .85 (p < .01) to b = .52 (p > .10).Footnote 3 Paralleling the SDO results, the Dangerous World × Expertise interaction had a significant indirect effect on left–right self-placement via RWA (I.E. = .33, with a 95% confidence interval of .02–.69). Thus, the mediated-moderation hypothesis was supported with respect to both worldview and ideological attitude-system pairs.Footnote 4

Discussion

Amidst a rising tide of political polarization, recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in the psychological foundations of citizens’ ideological affinities (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Jost et al. 2008, 2009). Along with an older tradition of psychological research on the origins of ideology (e.g., Adorno et al., 1950; Wilson, 1973), this emerging body of work suggests that a number of pre-political variables—including generalized social worldviews and orientations toward uncertainty and threat—may determine which ideological positions citizens find most attractive. However, political psychologists have paid considerably less attention to how the relationship between psychological variables and ideological affinity may be conditioned by processes related to the expertise-driven learning of abstract ideological constructs. In this vein, it is clear that individuals vary enormously in the extent to which they have acquired the conceptual knowledge needed to understand the different ideological options they have to choose from. It is thus possible that the impact of pre-political psychological variables on ideology may be different for citizens with different levels of expertise. Unfortunately, prior theoretical considerations offer divergent predictions about the effect of expertise. On one hand, some work suggests that expertise may simplify the process of choosing the ideological position most consistent with one’s psychological inclinations, leading to a stronger relationship between psychological variables and ideology (e.g., Federico & Goren, 2009). On the other hand, generalized worldviews and other basic psychological inclinations may serve as heuristics or metaphors that even those low in expertise are able to rely on, leading to roughly similar relationships between psychological variables and ideology among those low and high in expertise (Lane, 1962).

In this study, we examined the role of expertise with respect to two pre-political worldviews, i.e., competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs; and three ideological attitude systems, i.e., social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, and the general left–right dimension (Duckitt, 2001). Our data provide a clear pattern of support for the hypothesis that expertise should strengthen the relationship between pre-political variables—the two worldviews, in this case—and various ideological attitude systems. In particular, we found that expertise strengthened the relationship between each worldview and the specific ideological attitude system that prior work suggests it should be most closely linked to, i.e., SDO in the case of competitive-jungle beliefs and RWA in the case of dangerous-world beliefs. In turn, we also found that expertise strengthened the relationship between each worldview and left–right self-placement. Finally, tying these two sets of findings together, we found that the two specific ideological attitude systems—SDO and RWA—mediated the interactive effects of each worldview and expertise on general left–right self-placement. This suggests that expertise may strengthen both the immediate and downstream ideological consequences of worldviews.

Taken together with previous findings (Federico & Goren, 2009; Kemmelmeier, 2007), our results suggest that the political implications of pre-political psychological variables are not a given. Rather, the relationship between psychological variables and ideological affinity is notably stronger among those with an expert understanding of politics and abstract political ideas. While experts have the information and understanding needed to choose ideological positions maximally consistent with their underlying needs and views of social life, those who lack political expertise appear to make “noisier” choices among the various ideological options on offer in any given political environment. By extension, our findings suggest that the organizational effects of expertise may run deeper than suspected. While research has repeatedly indicated that expertise strengthens relationships between the explicitly political elements of ideological attitude systems (e.g., left–right self-placement, issue positions, and so on; Converse, 2000), the results we report here go one step further, suggesting that expertise also strengthens the relationship between ideological dimensions and their pre-political antecedents. As such, general worldviews—such as those implying a “dangerous world” or a “competitive jungle”—are not merely simple metaphors that all citizens make equally skilled use of in organizing their political attitudes.

More broadly, our interactive approach suggests a useful integration of the perspective on ideology offered by psychology and the perspective offered by political science. Like proponents of the “psychological” perspective, we suggest that ideological orientations may be shaped by underlying needs and worldviews that are pre-political and very general in nature. Nevertheless, like those who champion perspectives emphasizing the uneven diffusion of the content of ideological attitude systems and the role of expertise in the (differential) learning of this content, we also recognize that psychological variables may be of little consequence for ideological affinities among individuals whose political knowledge—in particular, their knowledge of ideas central to elite discourse—is lacking. Thus, our approach adds an awareness of the role of expertise in the learning of ideological content to the psychological perspective on ideology and an awareness of why citizens might be more attracted to one ideology rather than another to the political science approach.

Our results strengthen the case for analyzing ideological attachment in terms of its psychological foundations (Jost, 2006). As we have seen, previous research strongly suggests that citizens’ ideological affinities are not random; rather, they covary strongly with a wide range of psychological variables related to general orientations toward uncertainty, threat, and the nature of social life (Jost et al., 2003, 2009; Wilson, 1973). Adding heft to this general conclusion, our research indicates that psychological variables have their strongest impact on ideological affinity among those who best understand the content of various ideologies, suggesting that the connection between psychological processes and ideology is fundamental and rooted in the functional consonance between underlying needs and beliefs and the manifest content of ideological attitude systems. This last point has broader normative implications as well. Historically, many of our “best-of-all-worlds” models of political judgment rest on the Enlightenment ideal of autonomous individuals who form their beliefs under the guidance of reason and objective evidence rather than simplistic factors like “instinct,” emotion, or taken-for-granted presuppositions about the nature of reality (see Marcus, 2008). While both history and empirical research have cast general doubt on this idealized view and even on the reified contrast between reason and passion that it entails (Marcus, 2002; Redlawsk, 2006), expertise is often held up as a source of deliverance from instinct (see Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). However, our results suggest that seemingly stereotyped perceptions of the world as “dangerous” or violently competitive are particularly influential among the sophisticated and well informed. To the extent that these worldviews are as much a function of chronic personality predispositions as they are of immediate social reality (Duckitt, 2001), expertise may allow citizens to make political choices that are more instrumentally rational with respect to their deepest inclinations, but not necessarily ones that are more substantively rational with respect to individual and collective interests (Jost et al., 2009).

Limitations and Future Directions

The results of this study indicate that political expertise moderates the relationship between social worldviews and ideology. We find that people who know more about politics can better connect their general views of social life to various ideological positions. In this sense, our study tells us more about how political experts reason than about how political novices come to hold the preferences that they do. As such, processes behind the political preferences of political novices need further examination. In particular, future research should consider dependent variables other than the ideological attitude systems we examine here. It is certainly possible, and perhaps likely, that worldview endorsement may predict core value beliefs equally well regardless of political expertise. Although an understanding of ideological attitude systems is heavily dependent on expertise, people with varying levels of political expertise seem equally able to understand the abstract principles behind political values (Goren, 2004). These values—such as beliefs about equal opportunity, self-reliance and limited government—may be easier for the average citizen to make sense of and to understand. Indeed, Lavine et al. (1997) found that political novices tend to organize their political attitudes more by values than by ideology. To shed more light on the origins of belief system structure among novices, it would be useful in future research to consider the relationship between worldviews and core political values.

In addition, future work would do well to replicate the results of our correlational analyses using experimental manipulations of the two worldview variables. Previous research suggests that it is possible to activate specific worldviews by having people read scenarios that describe the future as extremely dangerous and frightening (see Duckitt & Fisher, 2003). To extend the research findings reported here, future studies should also examine whether experimentally activated worldviews interact with expertise to influence people’s ideological positions, and whether the interactions between each worldview and expertise have an indirect effect on left–right self-placement via their intermediate effects on the specific ideological attitude systems of SDO and RWA.

Finally, this study provides a cross-sectional snapshot of relationships between pre-political variables and ideological preferences at only one point in time. Unfortunately, studies with our design do not allow researchers to examine questions about changes produced by the gradual acquisition of expertise throughout the lifespan or potential feedback loops between worldviews and ideological attitude systems. Investigations into such questions require following individuals from adolescence to late adulthood, taking multiple measures of beliefs about the social world, ideological attitude systems, and levels of political expertise along the way. These longitudinal studies should also consider how variables such as parenting styles (e.g., authoritarian styles) and neighborhood crime levels affect the development of worldviews and ideological positions. Although costly in terms of time and effort, longitudinal studies of this sort would provide a much needed, comprehensive account of the origins of ideological preferences.

Notes

In the competitive-jungle/SDO analysis, the predictors in the final equation containing SDO accounted for a significant proportion of variance in left–right self-placement, F(5, 279) = 13.59, p < .001, with adjusted R 2 = .173.

All bootstrap analyses used 5000 replications to estimate indirect effects.

In the dangerous-world/RWA analysis, the predictors in the final equation containing RWA accounted for a significant proportion of variance in left–right self-placement, F(5, 279) = 32.65, p < .001, with adjusted R 2 = .305.

Duckitt and Sibley (2009) have argued that the competitive-jungle/SDO path should have its strongest effects on economic issues, while the dangerous-world/RWA path should have its strongest effects on social issues. Given the high correlation between our economic and social ideology indicators (r = .58, p < .001), we use a composite of the two. However, when the competitive-jungle/SDO analyses in Table 2, Model 2 of Table 4, and Fig. 1 are replicated using the economic ideology item as the sole dependent measure, all results remain the same. Similarly, when the dangerous-world/RWA analyses in Table 3, Model 3 of Table 4, and Fig. 2 are replicated using the social ideology item only as the dependent measure, the results also remain the same.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 47–92.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. G. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social-psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bennett, S. (2006). Democratic competence, before converse and after. Critical Review, 18, 105–142.

Brewer, P. R., & Steenbergen, M. R. (2002). All against all: How beliefs about human nature shape foreign policy opinions. Political Psychology, 23, 39–58.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, W. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Christie, R. (1954). Authoritarianism re-examined. In R. Christie & M. Jahoda (Eds.), Studies in the scope and method of “The Authoritarian Personality” (pp. 123–196). Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Converse, P. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent. New York: Free Press.

Converse, P. (2000). Assessing the capacity of mass electorates. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 331–353.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 41–113.

Duckitt, J., & Fisher, K. (2003). The impact of social threat on worldview and ideological attitudes. Political Psychology., 24, 199–222.

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). A dual process model of ideological attitudes and system justification. In J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, & H. Thorisdottir (Eds.), Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification (pp. 292–313). New York: Oxford University Press.

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., du Plessis, I., & Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual-process model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 75–93.

Duriez, B., & Soenens, B. (2006). Personality, identity styles and authoritarianism: An integrative study among late adolescents. European Journal of Personality, 20, 397–417.

Duriez, B., Van Hiel, A., & Kossowska, M. (2005). Authoritarianism and social dominance in Western and Eastern Europe: The importance of the socio-political context and of political interest and involvement. Political Psychology, 26, 299–320.

Erikson, R. S., & Tedin, K. L. (2003). American public opinion (6th ed.). New York: Longman.

Eysenck, H. J. (1954). The psychology of politics. New York: Praeger.

Federico, C. M. (2007). Expertise, evaluative motivation, and the structure of citizens’ ideological commitments. Political Psychology, 28, 535–562.

Federico, C. M., & Goren, P. (2009). Motivated social cognition and ideology: Is attention to elite discourse a prerequisite for epistemically motivated political affinities? In J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, & H. Thorisdottir (Eds.), Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification (pp. 267–291). New York: Oxford University Press.

Federico, C. M., & Schneider, M. (2007). Political expertise and the use of ideology: Moderating effects of evaluative motivation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71, 221–252.

Feldman, S. (2003). Values, ideology, and structure of political attitudes. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 477–508). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fiske, S. T., Lau, R. R., & Smith, R. A. (1990). On the varieties and utilities of political expertise. Social Cognition, 8, 31–48.

Goren, P. (2004). Political sophistication and policy reasoning: A reconsideration. American Journal of Political Science, 48, 462–478.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20, 98–116.

Hinich, M. J., & Munger, M. C. (1994). Ideology and the theory of political choice. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Hunter, J. D. (1991). Culture wars: The struggle to define America. New York: Basic Books.

Jost, J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61, 651–670.

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., & Napier, J. (2009). Political ideology: Its structure, function, andelective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 307–337.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Jost, J. T., Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., Gosling, S. D., Palfai, T. P., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 989–1007.

Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Ideology: Its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 126–136.

Judd, C. M., & Krosnick, J. A. (1989). The structural bases of consistency among political attitudes: Effects of expertise and attitude importance. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 99–128). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kemmelmeier, M. (2007). Political conservatism, rigidity, and dogmatism in American foreign policy officials: The 1966 Mennis data. The Journal of Psychology, 141, 77–90.

Kinder, D. R. (2006). Belief systems today. Critical Review, 18, 197–216.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (1985). Public opinion and political action. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 659–741). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1996). Motivated social cognition: Principles of the interface. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: A handbook of basic principles (pp. 493–522). New York: Guilford Press.

Lakoff, G. (1996). Moral politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lane, R. E. (1962). Political ideology. New York: Free Press.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing in election campaigns. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lavine, H., Thomsen, C. J., & Gonzales, M. H. (1997). The development of interattitudinal consistency: The shared consequences model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 735–749.

Layman, G. C., & Carsey, T. M. (2002). Party polarization and “conflict extension” in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 786–802.

Lipset, S. M. (1960). Political man. New York: Doubleday.

Long, J. S., & Ervin, L. H. (2000). Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. American Statistician, 54, 217–234.

Luskin, R. (1987). Measuring political sophistication. American Journal of Political Science, 31, 856–899.

Marcus, G. E. (2002). The sentimental citizen: Emotion in democratic politics. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Marcus, G. E. (2008). Blinded by the light: Aspiration and inspiration in political psychology. Political Psychology, 29, 313–330.

McFarland, S. (2005). On the eve of war: Authoritarianism, social dominance, and American students’ attitudes toward attacking Iraq. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 360–367.

Popkin, S. L. (1991). The reasoning voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). Feeling politics: Emotion in political information processing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rokeach, M. (1960). The open and closed mind. New York: Basic Books.

Sapiro, V. (2004). Not your parents’ political socialization. Annual Review of Political Science, 7, 1–23.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental designs: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., & Duckitt, J. (2007). Effects of dangerous and competitive worldviews on right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation over a five-month period. Political Psychology, 28, 357–371.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Bullock, J. (2004). A consistency theory of public opinion and political choice: The hypothesis of menu dependence. In W. E. Saris & P. M. Sniderman (Eds.), Studies in public opinion: Attitudes, nonattitudes, measurement error, and change (pp. 337–357). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stangor, C., & Leary, S. P. (2006). Intergroup beliefs: Investigations from the social side. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 243–281.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stimson, J. A. (2004). Tides of consent. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Weber, C. W., & Federico, C. M. (2007). Interpersonal attachment and patterns of ideological belief. Political Psychology, 28, 389–416.

Wegener, D. T., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2000). Analysis and design for non-experimental data: Addressing causal and non-causal hypotheses. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 412–450). New York: Cambridge.

Wilson, G. D. (1973). The psychology of conservatism. New York: Academic Press.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Federico, C.M., Hunt, C.V. & Ergun, D. Political Expertise, Social Worldviews, and Ideology: Translating “Competitive Jungles” and “Dangerous Worlds” into Ideological Reality. Soc Just Res 22, 259–279 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-009-0097-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-009-0097-0