Abstract

Numerous studies examining the impact of income on subjective well-being (SWB) have found significant positive relationships exhibiting decreasing marginal returns. However, the impact of economic circumstances on SWB is better captured through a combination of income, wealth (per capita net worth), and perceived and relative economic conditions. Using data from the Chinese Household Income Project, I find that within rural and urban China, wealth significantly predicts SWB, exhibiting decreasing marginal returns independent of more common measures of economic circumstances such as income and occupational status. Within urban China, these associations decrease in magnitude and significance with the addition of objective relative measures of wealth and income. Finally, I find that subjective perceptions of relative standard of living are strongly associated with SWB independent of other measures. These results highlight the importance of using multiple objective and subjective measures of economic circumstances, demonstrating potential limitations of studies that have focused exclusively on income as a predictor of well-being. Results are interpreted within the context of China’s changing social and economic structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A wide body of evidence suggests that economic circumstances are associated with subjective well-beingFootnote 1 (SWB) (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002; Headey and Wooden 2004; Aknin et al. 2009; Kahneman and Deaton 2010; Stevenson and Wolfers 2008). However, previous research has primarily used income as the sole measure of economic circumstances, and has focused on economically developed countries. This paper revisits the associations between economic factors and well-being in the context of China, employing measures of economic circumstances that go beyond mere income.

Evidence from many countries and across many decades supports the association between income and SWB (Veenhoven 1991; Diener and Biswas-Diener 2000; Diener and Oishi 2000; Diener and Seligman 2004; Deaton 2008; Stevenson and Wolfers 2008; Sacks et al. 2010). However, income alone poorly captures the entirety of economic well-being. This may be particularly true in economically developing countries, where economic well-being may be more dependent on a combination of durables, such as agricultural tools and livestock, than on income alone. Per capita net worth (also referred to throughout as wealth), which includes all of an individual’s or household’s durables, debts, savings, real estate, stocks, bonds, et cetera, provides a much clearer picture of a person’s overall economic circumstances, particularly when used in tandem with income (Mullis 1992).

Need theory suggests that the greatest returns to wealth will occur among the most asset-poor individuals, who will spend increased assets on basic necessities integral to well-being, such as shelter and food (Diener and Lucas 2000; Biswas-Diener and Diener 2001; Howell and Howell, 2008). Discretionary wealth (wealth remaining after basic necessities have been secured) has also been found to be associated with SWB (Howell et al. 2006), and may allow individuals to secure durables used for agricultural production or access to transportation. Wealth may also offer individuals comfort and flexibility in their living conditions, and help to buffer against exogenous shocks such as illness or drought. In this way, wealth acts as a safety net (Gilbert 2002). At higher levels of wealth, the effect of economic gains on happiness may depend on the extent to which individuals have material desires and are able to fulfill them (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002).

Easterlin (1974) argues that after a certain point, relative and not absolute economic circumstances impact SWB. This provides an explanation for the Easterlin Paradox, the idea that economic growth is not associated with increases in subjective well-being in the long-term, despite the fact that wealthier individuals within a society report being happier. Several studies have supported the idea that the association between economic circumstances and SWB is indeed strongly influenced by comparisons to reference groups and resulting experiences of relative deprivation (McBride 2001; Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2005; Kingdon and Knight 2007; Boyce et al. 2010; Knight and Gunatilaka 2011). Reference groups may be local, national, or international. Current circumstances may also be evaluated in comparison to expectations or previous circumstances. Relative economic circumstances could impact SWB through feelings of acceptance, power, and control over one’s life or other groups (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Keltner et al. 2003; Bookwalter and Dalenberg 2010).

While numerous studies have examined variations in SWB, macro- and particularly micro-studies of SWB have focused on higher-income countries (Appleton and Song 2008). Whether associations with well-being in more economically developed countries hold true for poorer countries is not clear. Within the need theory framework, one would expect that absolute improvements in economic circumstances would be more greatly associated with well-being in economically developing areas, where basic needs have not been met, material aspirations are not excessive, and where any amount of wealth might provide a crucial baseline level of protection against shocks. For example, Howell and Howell (2008) found larger effect sizes of income on SWB in lower-income developing economies. At the country level, they also found associations to be stronger when employing measures of wealth as opposed to income, potentially emphasizing the security provided by wealth in areas where alternative support structures or safety nets are lacking. The limited micro-data available seem to suggest that even within developing countries, relative economic circumstances also play an important role in well-being (Kenny 2005).

China presents a particularly interesting case for examining these relationships. China currently has the world’s second-largest economy (International Monetary Fund 2013) and one of the world’s fastest-growing economies (Tse 2010). However, within China, there are extreme disparities in wealth and income. Zhao and Sai (2008) found that the top wealth decile owned more than one-third of total wealth, whereas the bottom two deciles owned less than 3 %. Moreover, some evidence indicates that inequalities have been increasing (Xie and Zhou 2014; Wei and Wu 2001). Between 2005 and 2007, China’s Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality of income distribution, increased 14 % in urban areas (Li and Zhao 2007; Zhao and Sai 2008). Within China, there are also extreme rural–urban divides in income, with individuals in urban areas earning nearly twice as much as their rural counterparts. Rural–urban inequalities have been reinforced by government policies that favor urban areas (Yang 1999). These disparities allow us to look at a country that is simultaneously poor and relatively wealthy, independent of some of the cultural norms that remain constant throughout China.

Easterlin et al. (2012) examined changes in mean SWB in China from 1990 to 2010, using six sets of time series data. Despite rapid growth in mean per capita income, well-being did not see consistent improvement over this time period. Both life and financial satisfaction decreased among the lowest tercile of respondents, leading to an increase in inequality of well-being. Easterlin et al. (2012) attribute higher levels of Chinese life satisfaction in the early 1990s in part to high levels of employment, and welfare-based safety nets. At the start of the 2000s, when data employed in this study were collected, unprofitable state-owned enterprises, and as a result, employment and social safety nets, were on the decline in China (World Bank 2007). Positive effects of increased per capita income may also have been negated by rising material aspirations (Easterlin et al. 2012).

Well-being should be considered within the context of China’s unprecedented urbanization over the past several decades. The government-run hukou system regulates internal migration within China, as well as certain economic activities and access to government benefits (Chan and Zhang 1999). An individual’s hukou dictates whether they are legally permitted to live in urban or rural areas. As a result of mass migration to urban areas, over 20 % of China’s population now lives in areas not sanctioned by their hukou (Gong et al. 2012). Mass migration may reflect changing aspirations among the Chinese population, while providing new reference groups for social comparison. Recently urbanized migrant workers may be faced with evidence of substantial wealth disparities, causing negative evaluations of personal social standing despite objective improvements over rural standard of living.

Research on happiness has increased dramatically over the last few decades (Diener et al. 1999, 2013a, b). In this time, a plethora of research has emerged on the relationships between SWB and a wide variety of factors, including personality, social connectedness, self-rated health, marital status, ethnic group, and religiosity, among many others (Diener 2012, 2013a, b; Pavot and Diener 2013). The emphasis of this study on the relationship between economic circumstances and SWB should not be considered an argument that wealth is the most important determinant of individual happiness. However, better understanding of the associations between economic circumstances and SWB will allow us to more effectively evaluate the extent to which political and societal emphasis on economic growth is justified, and how social programs can most effectively improve well-being.

Debate is ongoing about the appropriate way to measure SWB. The methods used to measure happiness determine, to a degree, the types of responses that respondents produce. Instead of using cross-sectional survey questions, some argue that SWB should be measured at repeated random times throughout the day (Stone et al. 1999), or that subjective reports should be “reviewed” by someone close to the individual who is self-reporting (Sandvik et al. 1993). Additionally, different dimensions of happiness (such as affective/emotional or cognitive/evaluative SWB) require unique forms of measurement (Schimmack et al. 2008). Differences in reports of well-being may also be shaped by cultural norms. For example, Suh proposed that East Asian norms surrounding modesty may prevent respondents from self-reporting very high levels of well-being or success (Suh 2000).

Due to limitations in the questions available on large-scale surveys, many of the quantitative studies on happiness rely on one or two SWB variables. For example, the World Values Survey (2009) utilizes a four-point ordinal measure of SWB that is similar to the variable (described in Sect. 3.2.1) employed in this study. Such SWB questions have been correlated with laughing, smiling, and sociability (Diener 1984), as well as self-reported health and sleep quality (Diener et al. 2006). More generally, SWB questions have also been found to have reasonably high reliability (Eid and Diener 2004).

In Sect. 1, I reviewed the relevant literature on economic circumstances and SWB. In Sect. 2, I present three hypotheses regarding the associations between SWB and economic circumstances. Using data from the Chinese Household Income Project (Sect. 3.1), I find support for these hypotheses (Sect. 4). Additional analysis is included examining rural–urban variations in these associations. These results are connected to China’s social and economic context (Sect. 5), and several limitations are outlined (Sect. 6).

2 Hypotheses

The first two hypotheses suggest that SWB will be associated with two different objective measures of economic circumstances. The third hypothesis asserts that perceptions of economic circumstances relative to others will also impact SWB.

Hypothesis 1

Income will be positively and significantly associated with SWB after controlling for covariates.

Hypothesis 2

Per capita net worth (wealth) will be positively and significantly associated with SWB after controlling for associations with income.

Hypothesis 3

Perceived relative standard of living will be positively and significantly associated with subjective well-being after controlling for absolute and relative wealth and income.

Hypothesis 1 is meant to affirm previous findings on the income-SWB association within the CHIP data set. Hypothesis 2 examines the impact of the addition of wealth to the model used to test hypothesis 1. The addition of a variable examining perceived relative standard of living in hypothesis 3 allows me to tap a perceived relative component of economic circumstances after controlling for objective relative economic circumstances related to wealth and income. Support for this hypothesis would emphasize the importance of reference groups and perceived differences in determining how economic circumstances are associated with SWB.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 The Chinese Household Income Project (CHIP)

The Chinese Household Income Project is comprised of a multistage stratified probability sample of the People’s Republic of China, collected in 2002–2003 (Shi 2002). Data collection was sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the Institute of Economics, the Chinese Academy of Science, and the Asian Development Bank. The project’s goal was to gather information on income distribution throughout China. However, the CHIP contains variables on a range of socio-demographic and economic topics. More extensive information on the CHIP can be found in the link provided in “Appendix 1”.

Data were gathered from both rural and urban areas within China. The rural survey covered 22 provinces; the urban survey covered 12 provinces and 77 cities. There were slight rural–urban differences in some survey questions, which are outlined in Sect. 3.2. Additionally, among urban respondents, some survey items were varied based on whether the respondent was a migrant.

Data collection was conducted via questionnaire-based face-to-face interviews. For many questions, a single household respondent was allowed to answer for other members of the household. This was not the case for the SWB variable. SWB data was only collected from the household respondent and not the entire household. Therefore, each household yielded one individual with SWB data who was included in the analysis. Analysis was also restricted to respondents age 18 and older. A small percentage of households (1.6 %) whose total debts were greater than their combined assets were excluded, because the relationship between negative wealth and SWB is not functionally similar to the relationship between positive wealth and SWB. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper, the relationship between negative wealth and SWB is an interesting topic for future research. After incorporating these inclusion criteria, a total of 17,682 individual observations remained, with 9060 observations coming from the rural sampling frame and 8622 coming from the urban sampling frame. Among the urban individuals, 1895 were migrants while 6727 were not-migrants All further descriptive and inferential statistics will be based on these groups of individuals.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Subjective Well-Being

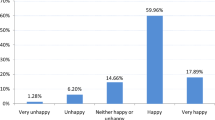

SWB was measured through a single five-point Likert-scale question. In urban areas, this question was: “Generally speaking, do you feel happy?” The responses were: very happy, happy, so–so, not very happy, and not happy at all. In rural areas, the question was worded “Are you happy now?” In rural areas the response category “so–so” was written “just so–so.” Descriptive statistics for this and other categorical variables are presented in Table 4 of the “Appendix 2”. Approximately 10 % of respondents consider themselves to be not happy at all or not very happy, and nearly 58 % are either happy or very happy. About 31 % of respondents reported being “so–so.” Responses of “don’t know” were collapsed with non-responses, accounting for approximately 1 % of respondents. The average person is somewhere between so–so and happy (mean = 3.58). The rural mean was 0.21 higher than the urban mean, which t-tests demonstrate to be significantly different at the p < 0.001 level.

3.2.2 Income

Income is measured via the equivalized sum of personal income from all family members (from all jobs, subsidies, and the monetary value of in-kind income) and shared household income. Within the urban data set, income information was collected at the individual level, which was then summed across the family and equivalized. The urban-migrant subsection had a variable measuring the total income of the household, so there was no need to sum before equivalizing. Rural income is calculated by adding individual wage income for all family members to total family production (which was calculated separately), and then equivalizing. Although individual incomes were sometimes reported for wage jobs in rural areas, the majority of rural income came from (primarily agricultural) family production activities.

The purpose of equivalization is to determine per capita estimations of income based on the total income of a household. I utilize the square root equivalization method, which involves dividing total household income by the square root of the household size (Headey and Wooden 2004). For urban non-migrants, household size was measured as the number of family members or relatives living in the household. For urban migrants, it was specified that household size should include only individuals living in the city. In rural areas, household size was measured by the number of individuals living in the household for 6 months or more.

The median income is 8166 yuan per year. However, there are large urban–rural divides. Individuals from urban areas have a median income of 11,286 yuan, nearly twice as large as the median rural income of 5736 yuan. Descriptive statistics for income and other socioeconomic variables are presented in Table 5 of the “Appendix 2”. In analysis, the functional form of income is logged income. This transformation was applied because of the presence of skewness in the non-logged income variable, and because this functional form is supported in the literature (Diener et al. 2013a, b). Additionally, a base of 1 yuan has been added to allow a log to be taken of those with an income of 0.

3.2.3 Wealth (Per Capita Net Worth)

Wealth is calculated by adding the total value of all financial assets (such as cash, fixed deposits, stocks, bonds, and money lent out) to the value of all durable goods, owned houses, and other assets (such as livestock, farm equipment, electronics, etc.). The total amount of household debt (for example, from hardship of living, medical expenses, purchase of durables, loans, and interest rates on previous debts) is then subtracted from this amount.

The result is total household wealth, measured in yuan. The same technique used to generate equivalized income is employed to generate an individual level value of wealth. The median individual wealth across all areas is 20,632 yuan, with values ranging from 0 to 2,005,000 yuan. Again, rural–urban disparities are found. The rural–urban inequality is much greater for wealth than for income: the median wealth in urban areas was 45,017 yuan, while the median wealth in rural areas was 13,547 yuan. For the same reasons as with income, the functional form of wealth is logged wealth. Again, a base of 1 yuan was added to allow the log to be taken for respondents with 0 wealth.

3.2.4 Perceived Relative Standard of Living

Perceived standard of living is the only variable used in this study that exists exclusively in the urban non-migrant survey, with no acceptably analogous question in the urban migrant or rural survey. The question asks: “In which group do you think your household living standard falls in the city?” with possible responses of: low (in the lowest 25 %), below middle (in the next-lowest 25 %), above middle (in the third-lowest 25 %), and high (in the highest 25 %). Approximately 88 % of respondents considered themselves in the middle two categories. Less than 1 % considered themselves in the top 25 %, while around 11 % considered themselves in the bottom 25 %.

Throughout this paper, objective relative economic circumstances (or objective relative income/wealth) refer to an individual’s actual relative economic position, measured by their income or wealth centile within a city. This is distinct from an individual’s perceived relative economic circumstances, which requires respondents to judge how their standard of living compares to others within their city. For example, a respondent with an equivalized wealth of 80,000 yuan might be in the 83rd centile of wealth within their city, representing their objective relative economic circumstances. However, they may self-report a perceived relative standard of living of “below-middle.” These different concepts represent distinct but related pathways through which economic circumstances can influence well-being.

3.2.5 Demographic Controls

Controls were also included for gender, age (measured continuously), education (coded as completion of elementary school or below, any middle or technical school, and any college or university), household size (measured as a count), urban–rural location, marriage (coded never married, with spouse, divorced, widowed, and other), ethnicity (coded as Han majority, minority), employment status (such as working, unemployed, retired, and full-time homemaker), and potentially privileging Communist Party membership (coded as Communist Party member and other/no party). Tables 4 and 5 in the “Appendix 2” contain descriptive statistics for these remaining socio-demographic variables. Notably, the household respondents (who had SWB data) were substantially older and more often male than the total sample, including non-respondent household members. Household respondents were also more likely to be married and currently working. These differences probably occurred due to systematic sampling biases in which certain individuals (middle-aged men) were inordinately likely to be selected from the household members to be the respondent.

3.3 Methods

The statistical technique employed in this study is ordered logistic regression. This technique is used because the dependent variable, subjective well-being, is ordinal. We assume that there is an underlying continuous latent SWB construct, which can be modeled \(swb^{*} = \beta x + \varepsilon\), however, the CHIP survey only captures SWB responses on an ordinal scale from 1 to 5. For an overview of methodological concerns related to cardinal versus ordinal modeling of SWB and related statistical assumptions, see Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004).

Results of the ordered logistic regressions are displayed in several forms. First, odds ratios are given for each coefficient. Odds ratios display the odds of an outcome occurring if x is present, compared to the odds of an outcome occurring if x is not present. An odds ratio of 1.5 for the independent variable “income” would mean that every one-unit increase in “income” is associated with 1.5 times greater odds of being in a higher category of SWB compared to the odds of being in all lower categories of SWB. Additionally, results will be displayed in log odds, with standard errors in parentheses. Standardized coefficients will be displayed in brackets for income and wealth. Comparisons between coefficients are made using Wald tests. To deal with the effects of hierarchical groupings of households by location, all models include clustering on geographic location, comprised of county for rural respondents and city for urban respondents. Due to heteroskedasticity, Huber-White robust standard errors are employed when applicable.

4 Results

In Table 1, the first model examines the relationship between income and SWB after accounting for several covariates. Model 1 demonstrates a positive impact of logged income on SWB at the p < 0.001 level of significance. For every one-unit increase in logged income, the odds of being in a higher category of SWB increases by a factor of 1.66, after controlling for all other variables.

In Table 1, Model 2 is identical to Model 1, except that the logged wealth variable has been added. As stated by Headey, Muffels, and Wooden (2008), if income and wealth were strongly collinear, the inclusion of both variables simultaneously would be problematic. However, logged income and wealth are only moderately correlated (0.49).

In Model 2, wealth shows an independent effect on SWB at the p < 0.001 level of significance, even after controlling for demographic factors and income. However, the variable for income still displays a significant association with SWB. While the standardized coefficient of logged income (β = 1.37) is greater than that of logged wealth (β = 1.21), this difference was not significant at the p < 0.01 level. With the addition of the wealth variable, the magnitude of the income variable (in log odds) shrinks approximately 20 %. This decrease is significant at the p < 0.001 level. The odds of being happy also appear to be higher for respondents who are living in rural areas and are female.

Due to the functional form of the wealth variable, the relationship between SWB and wealth exhibits decreasing marginal returns. In Fig. 1, I display the predicted probabilities of falling into different SWB categories based on different levels of wealth, holding all other variables constant at the mean. These probabilities were generated via post-enumeration commands performed after running Model 2. The labels on the x-axis are the values of wealth in yuan equivalent to the scores of transformed wealth employed in the regression. However, the figure presents the relationship between SWB and the log of wealth. The x-axis is restricted to values of wealth below 5000 yuan, which accounts for slightly more than the bottom decile of the sample.

Going from 1 to 5000 yuan in wealth is associated with the predicted probability of being happy nearly doubling, going from 24.9 % at 1 yuan to 45.2 % at 5000 yuan. The same general trend can be observed for the predicted probability of being not very happy, which drops from 22.5 to 9.4 % at 1 and 5000 yuan, respectively. By comparison, going from 100,000 yuan to 200,000 yuan is associated with an increase in the predicted probability of being happy of only 1 percentage point.

Also noteworthy are the differences in the impact of income and wealth on SWB by urban versus rural residence. In Table 6 of the “Appendix 2”, two opposing patterns emerge after stratifying by location. Comparing coefficients standardized within each location, I find that within urban areas there are significantly larger associations (p < 0.01) between income and SWB (β = 1.42) than wealth and SWB (β = 1.12). Across rural areas, the pattern is the opposite. The coefficient for wealth (β = 1.41) is significantly (p < 0.01) larger than the coefficient for income (β = 1.19). This general trend may result from the fact that rural communities are relatively more impoverished in terms of wealth than income: median income in rural areas is nearly half of that in urban areas. However, median wealth in rural areas is less than one-third of that in urban areas. These findings highlight the potential importance of wealth in more impoverished areas.

Next, to test hypothesis 3, I examine the effects of the perceived relative standard of living variable. This variable examines respondents’ perceived standard of living relative to others in their city (bottom 25, 25–50 %, etc.). Only urban non-migrants were asked this question, reducing the sample to less than 7000 respondents. A crosstab of this variable with quartiles of wealth (calculated by city, for the reduced sample) is located in Table 2.

The purpose of constructing Table 2 was to see how individuals in different city-based asset quartiles perceived their standards of living compared to others in the same city. Nearly 90 % of respondents place themselves in the middle two standard of living categories. Lack of responses in the highest category of perceived relative standard of living may be due to cultural response biases pertaining to modesty (Mathews 2012). To state that you are wealthy, even to a survey interviewer, may be considered a form of bragging. Similarly, respondents may be embarrassed to self-report having a lower standard of living. However, it is also possible that some respondents are miscalculating where they stand in their city. For example, 42.28 % of the respondents in the top asset quartile by city place themselves in the second-lowest standard of living category. This may reflect a combination of social desirability responses and miscalculation.

Model 3 in Table 3 is the same as Model 2 in Table 1, except that it is limited to urban non-migrants, as with Table 2. The general trends are similar between these two models: both income and wealth are significant at the p < 0.05 level after controlling for all other variables. Model 4 builds on Model 3, including a variable measuring objective relative economic position. This variable was created by calculating what centile individuals fall into in terms of income and wealth within their city. With the inclusion of these variables, both logged income and wealth become insignificant. These strong associations potentially demonstrate the importance of objective relative economic standing based on absolute levels of income and wealth. However, strong correlations between income and objective relative income (0.76), and wealth and objective relative wealth (0.73), are suggestive of collinearity issues.

In Model 5, I add the relative perceived standard of living variable from Table 2. This variable is found to be strongly and significantly associated with SWB. A one-unit increase in perceived relative standard of living is associated with a 2.74 increase in the odds of being in a higher category of SWB. Additionally, after adding this variable to the regression model, only the relative income variable is significant. Figure 2 (located in “Appendix 2”) displays predicted probabilities of different categories of SWB based on the perceived relative variable in Model 4. For example, going from self-reporting being in the lowest standard of living category (0–25 %) to the middle category (26–50 %) is associated with the predicted probability of being happy increasing from 26 % to 46 %. However, Models 3 to 5 are less generalizable than Models 1 and 2, as analysis was restricted to urban non-migrants.

5 Discussion

It is becoming increasingly evident that measures of economic circumstances based entirely on income are inadequate. This paper has demonstrated some of the advantages of employing more complex objective, subjective, and relative measures of economic circumstances in predicting SWB. This is not to suggest that material wealth is the appropriate pathway to happiness. There is mounting evidence that (at least after basic material needs have been met) a strong desire for material wealth may be detrimental to happiness (Headey et al. 2008). It is also useful to note that OLS models of the association between income, wealth, and SWB in urban China had an R-squared of only 0.06. The addition of the perceived and objective relative variables produced an r-squared of 0.16. This indicates that much variation in SWB is still unaccounted for when one only looks at economic circumstances. Along these lines, in the CHIP data set, numerous individuals with low income and wealth were happy, and many individuals with high income and wealth were not. However, it is important to understand the complexity of the associations between economic circumstances and SWB to the extent that they are present.

The results from Models 1 and 2 suggest several important findings. Both income and wealth have independent associations with SWB. In the results section, it was noted that the magnitude of the income variable decreases after the addition of the wealth variable. This finding suggests that under certain circumstances, exclusion of wealth may lead to a positive bias in income–well-being associations. In Table 6, when these results were stratified by location, we see contrasting trends: the standardized coefficient for income was significantly larger than the coefficient for wealth in urban areas, while the opposite was true for rural areas. These differences reflect the unique circumstances of China. Rural areas are substantially more impoverished in terms of wealth compared to income relative to urban areas. Additionally, rural families may be more dependent on productive assets to sustain their livelihood.

Rural families may also be particularly vulnerable to shocks that would not affect non-agricultural urban workers. For example, nearly 40 % of rural respondents said they “suffered from disaster” in 2002, with an average reported decrease in agricultural earnings of nearly 30 %. Such shocks should be considered in the context of recent studies demonstrating the deleterious effects of poverty on cognitive performance (Sheehy-Skeffington and Haushofer 2014; Mani et al. 2013), which could further impact well-being on a variety of levels. Having adequate holdings of wealth may be integral to effectively buffering against or quickly recovering from such shocks.

In circumstances where families’ productive capabilities are not as tied to their livelihoods, or where social services are more widely available, it is possible that wealth would have less of an effect on well-being. For example, in economically developed countries, the association between absolute wealth and well-being might be less substantial, as more families may have access to some form of safety net, either from personal wealth holdings or government services. In these circumstances, the contribution of wealth to well-being may be dependent on relative evaluations of wealth, and the ability to fulfill desires for culturally relevant goods and services, particularly in reference to salient comparison groups.

In Models 3 through 5, I examine objective, perceived and relative indicators of economic circumstances in urban areas. After adding measures of objective relative economic standing within one’s city, the absolute measures of income and wealth become insignificant. While these results may be due to fairly strong collinearity between relative and non-relative objective measures, they may also be indicative of effects related to social comparisons and relative deprivation. Going beyond these objective relative measures, I add a variable measuring perceived relative standard of living. This variable is strongly associated with SWB, despite the four other measures of economic circumstances employed. Out of the four other variables, only objective relative income remains significant, which is consistent with the apparent strength of association between income and SWB in urban compared to rural areas.

The cross-tabulation of the perceived relative variable with wealth quartiled within cities raises several questions. At the most basic level, we may want to know why individuals whose wealth is in the top 25 % (or even the top 5 %) may not report being in even the top 50 % in terms of standard of living. Similar findings, indicating the variability of subjective (or self-reported) evaluations of economic circumstances have been found by several other authors. Milanovic and Jovanovic (1999) found decreases in self-reported poverty over a period of rising inequality and falling incomes in Russia. Similarly, in a study of over 560 families in Tanzania, not a single family self-reported being in the highest wealth category (World Bank 1999). Using the same Tanzanian data, Kenny (2005) found similar levels of self-reported wealth in both relatively poor and relatively rich locales. This evidence suggests that self-reports of economic circumstances are perhaps only loosely associated with absolute economic circumstances. In the context of China, this may be due to cultural values emphasizing modesty. Such cultural response biases may affect responses for other variables in this study. For example, income, wealth, and happiness may all have been deflated due to culturally biased item response patterns. These errors could take place in interpretation of questions (What does “happy” really mean?), evaluation of individual circumstances (How much are my assets worth?), comparisons to others (I know how wealthy I am, but am I in the top 25 %?), or translation of information into survey responses (If I say I’m rich, I’ll be bragging, so I’ll say I’m upper middle class).

Overall, findings from this study are supported by an emerging literature stressing the role of relative economic circumstances. Relative deprivation may be linked to SWB through self-evaluation of achievements or feelings of control over others (McBride 2001; Keltner et al. 2003; Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2005; Kingdon and Knight 2007; Clark et al. 2008; Bookwalter and Dalenberg 2010; Boyce et al. 2010). While Anderson et al. (2012) emphasize the importance of local or face-to-face reference groups in making comparisons, findings from this study suggest that comparisons may take place on multiple levels. Results also emphasize that while objective relative economic circumstances appear to play a role in predicting well-being, subjective perceptions of these differences may be even more greatly associated with well-being, particularly after basic needs have been met.

These findings must be considered within China’s changing socioeconomic and demographic circumstances. Over the last three and a half decades, the Gini coefficient for China has nearly doubled, with levels of inequality now surpassing the United States (Xie and Zhou 2014). This growing inequality has been driven in large part by rural–urban divides in income. In rural areas, economic activities remain primarily comprised of family-based agricultural production, while urban China has rapidly industrialized. China is also experiencing massive internal migration, which may affect both aspirations and social comparisons of urban and rural workers. Mass migration also poses new challenges to the shifting Chinese welfare system (Chan 2010).

These changing contexts have implications for social policies aimed at improving well-being. Policies targeting individuals in the lowest quartile of wealth would see the biggest increases in happiness (or decreases in unhappiness) per unit increase of wealth. Returns to increases in wealth appear to be greater among rural individuals, who may be particularly asset-poor. It is at these lower levels of wealth that assets may be utilized to prevent small exogenous shocks (such as crop failure or short-term unemployment) from causing individuals to fail to acquire the basic necessities of life. At higher levels of wealth, it may be that reducing inequality will most greatly improve well-being by reducing differences in economic circumstances among salient reference groups. Piketty and Qian (2006) suggest that one strategy to reduce inequality would be for China to implement progressive tax policies that could redistribute the inordinate amounts of wealth accumulated by the top income bracket in recent years. Effective social welfare programs and state-provided benefits might also reduce the importance of individual income or wealth to SWB by providing resources and security to those who are most vulnerable (Pacek and Radcliff 2008; Hochman and Skopek 2013).

6 Limitations and Conclusion

Several limitations to this paper suggest avenues for future research. Like many large surveys, the CHIP has only one SWB question. Within this survey it is possible that minor variations in the wording of the SWB question or the response categories between urban, rural, and migrant populations may have biased results. More generally, variations between survey items should be minimized to allow for robust comparisons to be made within different sections of the CHIP data. Despite the large probability sample employed in this study, only one respondent from each household was asked about their SWB. Within China, the external validity of this study is limited by the extent to which respondents who answered the SWB questions differed from the total sample.

Due to the substantial association between perceived relative standard of living and SWB, researchers are encouraged to examine the mechanisms through which this and other subjective and objective relative variables impact SWB. Again, it is useful to note that cultural response biases may have impacted these associations (Suh 2000). Better understanding of how such biases may impact reported economic circumstances and well-being would be particularly beneficial to studies comparing self-reported or subjective concepts across disparate contexts.

Future studies could also disaggregate the summary wealth variables employed in this study to provide a more detailed understanding of how durables, assets, and debts are associated with SWB. Studies could also explore stratified or interactional associations among income, wealth, and SWB. This could help to determine potential threshold effects in the associations between economic circumstances and happiness. To better understand the economic context within China, studies could incorporate regional variations in economic factors such as cost of living and tax rates.

More generally, since the data used in this study are cross-sectional, I am unable to make causal inferences from the models. These issues could be partially remedied through the use of panel data and instrumental variables. Such techniques could help to parse out the complex interplay between income and wealth. Hopefully future research will examine different cultural contexts to see if the effects found here exist elsewhere. In more economically developed countries, where basic needs are generally secured, the role of wealth in sustaining economic livelihoods and protecting against shocks may be less important than relative perceptions of whether you are “keeping up with the Joneses.”

The goal of this paper has been to explore the nature of the relationships between objective and perceived relative economic circumstances, and SWB using data from a multistage stratified probability sample of China. This study found significant impacts of wealth on SWB independent of a more traditional measure of economic circumstances—income. Results from this paper emphasize an often-overlooked component of economic well-being: perceived relative economic circumstances, measured here through perceived relative standard of living. This variable was found to have a large and highly significant impact on SWB. This study suggests that absolute, relative, and subjective wealth require considerably more attention in the field of happiness economics and by those who value the well-being of societies. It is hoped that later surveys measuring economic circumstances will be inclined to include detailed questions regarding wealth (particularly in economically developing countries) and perceptions of economic circumstances.

Notes

The terms “subjective well-being” and “happiness” are used interchangeably throughout this paper.

References

Aknin, L. B., Norton, M. I., & Dunn, E. W. (2009). From wealth to well-being? Money matters, but less than people think. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 523–527.

Anderson, C., Kraus, M. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Keltner, D. (2012). The local-ladder effect social status and subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 23(7), 764–771.

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in urban China: Components and determinants. World Development, 36(11), 2325–2340.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2001). Making the best of a bad situation: Satisfaction in the slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 329–352.

Bookwalter, J. T., & Dalenberg, D. R. (2010). Relative to what or whom? The importance of norms and relative standing to well-being in South Africa. World Development, 38(3), 345–355.

Boyce, C. J., Brown, G. D., & Moore, S. C. (2010). Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 21(4), 471–475.

Chan, K. W. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: Notes on a debate. Population and development review, 36(2), 357–364

Chan, K. W., & Zhang, L. (1999). The hukou system and rural-urban migration in China: Processes and changes. The China Quarterly, 160, 818–855.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M.A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association, 22(2), 53–72.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E. (2012). New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. American Psychologist, 67(8), 590–597.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2000). New directions in subjective well-being research: The cutting edge. Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(1), 21–33.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2000). Explaining differences in societal levels of happiness: Relative standards, need fulfillment, culture, and evaluation theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 41–78.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist, 61(4), 305.

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 185–218). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Ryan, K. L. (2013a). Universals and cultural differences in the causes and structure of happiness: A multilevel review. In C. Keyes (Ed.), Mental well-being (pp. 153–176). Dordrecht: Springer.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Beyond money toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013b). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 267–276.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. Nations and households in Economic Growth, 89, 89–125.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(25), 9775.

Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2004). Global judgments of subjective well-being: Situational variability and long-term stability. Social Indicators Research, 65(3), 245–277.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How Important is Methodology for the estimates of the determinants of Happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5), 997–1019.

Gilbert, D. (2002). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality (6th ed.). New York, NY: Wadsworth.

Gong, P., Liang, S., Carlton, E. J., Jiang, Q., Wu, J., Wang, L., & Remais, J. V. (2012). Urbanization and health in China. The Lancet, 379(9818), 843–852.

Headey, B., Muffels, R., & Wooden, M. (2008). Money does not buy happiness: Or does it? A reassessment based on the combined effects of wealth, income and consumption. Social Indicators Research, 87(1), 65–82.

Headey, B., & Wooden, M. (2004). The effects of wealth and income on subjective well-being and ill-being. Economic Record, 80(s1), S24–S33.

Hochman, O., & Skopek, N. (2013). The impact of wealth on subjective well-being: A comparison of three welfare-state regimes. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 34, 127–141.

Howell, R. T., & Howell, C. J. (2008). The relation of economic status to subjective well-being in developing countries: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 536.

Howell, C. J., Howell, R. T., & Schwabe, K. A. (2006). Is income related to happiness for the materially deprived? Examining the association between wealth and life satisfaction among indigenous Malaysian farmers. Social Indicators Research, 76, 499–524.

International Monetary Fund. (2013). Transitions and tensions. Washington, DC: World Economic Outlook, World Economic and Financial Survey.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284.

Kenny, C. (2005). Does development make you happy? Subjective wellbeing and economic growth in developing countries. Social Indicators Research, 73(2), 199–219.

Kingdon, G., & Knight, J. (2007). Unemployment in South Africa, 1995–2003: causes, problems and policies. Journal of African Economies, 16(5), 813–848.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2011). Does economic growth raise happiness in China? Oxford Development Studies, 39(01), 1–24.

Li, S., & Zhao, R. (2007). Changes in the distribution of wealth in China, 1995–2002. Research Article No. 2007/3 in UNUWIDER. http://econarticles.repec.org/article/unuwarticle/rp2007-03.htm.

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341(6149), 976–980.

Mathews, G. (2012). Happiness, culture, and context. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(4), 299–312.

McBride, M. (2001). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 45(3), 251–278.

Milanovic, B., & Jovanovic, B. (1999). Change in the perception of the poverty line during times of depression. Policy Research Working Papers, World Bank WPS, Washington, DC.

Mullis, R. J. (1992). Measures of economic well-being as predictors of psychological well-being. Social Indicators Research, 26(2), 119–135.

Pacek, A., & Radcliff, B. (2008). Assessing the welfare state: The politics of happiness. Perspectives on Politics, 6(02), 267–277.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2013). Happiness experienced: The science of subjective well-being. In S. David, I. Boniwell, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 134–154). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Piketty, T., & Qian, N., (2006). Income inequality and progressive income taxation in China and India, 1986–2015. CEPR Discussion Paper 5703. Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

Sacks, D., Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2010). Subjective well-being, income, economic development and growth. NBER Working Paper 16441. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Sandvik, E., Diener, E., & Seidlitz, L. (1993). Subjective well-being: The convergence and stability of self-report and non-self-report measures. Journal of Personality, 61(3), 317–342.

Schimmack, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2008). The influence of environment and personality on the affective and cognitive component of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 41–60.

Sheehy-Skeffington, J., & Haushofer, J. (2014). The behavioural economics of poverty. In UNDP barriers to and opportunities for poverty reduction (pp. 96–112).

Shi, L. (2002). Chinese Household Income Project, ICPSR21741-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2009-08-14. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR21741.v1.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox (No. w14282). National Bureau of Economic Research, 1–102.

Stone, A. A., Shiffman, S. S., & DeVries, M. (1999). Rethinking our self-report assessment methodologies: An argument for collecting ecological valid, momentary measurements. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Wellbeing: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 26–39). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Suh, E. (2000). Self, the hyphen between culture and subjective well-being. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), culture and subjective well-being (pp. 63–86). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tse, E. (2010). The China strategy: harnessing the power of the world’s fastest-growing economy. New York: Basic Books.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34.

Wei, S. J., & Wu, Y. (2001). Globalization and inequality: Evidence from within China. No. w8611. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

World Bank. (2007). China’s modernizing labor market: Trends and emerging challenges. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (1999). Tanzania: Peri-urban development in the African 733 Mirror. Report No. 19526TA. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Values Survey. (2009). 1981–2008 official aggregate v. 20090901, 2009. World Values Survey Association.

Xie, Y., & Zhou, X. (2014). Income inequality in today’s China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(19), 6928–6933.

Yang, Dennis Tao. (1999). Urban-biased politics and rising income inequality in China. American Economic Review, 89(2), 306–310.

Zhao, R., & Sai, D. (2008). The distribution of wealth in China. In B. Gustafsson, L. Shi, & T. Sicular (Eds.), Inequality and public policy in China (pp. 118–144). Cambridge, UK, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Selected Survey Questions

This appendix contains questions from the 2002 CHIP questionnaire that are particularly important to this study, emphasizing differences between rural, urban non-migrant, and urban-migrant versions of the survey. Variations in survey items may reflect variations in the actual questions employed in data collection or variations in translation. All versions of the questionnaire and additional information can be found at http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/21741.

1.1 Subjective Well-Being

Urban (migrant and non-migrant): Generally speaking, do you feel happy?

-

(1) very happy, (2) happy, (3) so–so, (4) not very happy, (5) not happy at all (6) don’t know

Rural: Are you happy now?

-

(1) very happy, (2) happy, (3) just so–so, (4) not very happy, (5) not happy at all, (6) don’t know

1.2 Perceived Relative Standard of Living

Urban (non-migrant): In which group do you think your household living standard falls in the city? (Current)

-

(1) Low (in the lowest 25 %), (2) Below middle (in the next lowest 25 %), (3) Above middle (in the third lowest 25 %), (4) High (in the highest 25 %)

1.3 Political Party

Urban (non-migrant): Member of which party?

-

(1) The Communist Party, (2) Other Parties, (3) Communist Youth League, (4) No Party

Urban (migrant): Member of CPPC?

-

(1) yes, (2) no

Rural: Member of the Communist Party?

-

(1) yes, (2) no

1.4 Household Size

Urban (non-migrant): Household size is calculated by summing the number of members within the household based on the unique ID codes of members.

Urban (migrant): How many people were there in your household? (people who were resident in this city)

Rural: Total number of residents in your household in 2002 …living with you 6 months and more

1.5 Marital Status

All: Marital status?

-

(1) with spouse, (2) never married, (3) divorced, (4) widow or widower, (5) other

1.6 Minority Status

Rural/Urban (migrant): National ethnic minority?

-

(1) yes, (2) no

Urban (non-migrant): Nationality?

-

(1) Han, (2) Minority, (3) others

1.7 Income and Wealth

Further decomposition of income and wealth can be found in the full-length versions of the questionnaire. A more extensive breakdown of these variables is excluded here to save space. For example, the composite variable measuring household income in rural areas is comprised of over 40 variables.

1.8 Wealth

Urban (migrant and non-migrant):

-

Total financial assets

-

Estimated present market value of durable goods

-

Estimated present market value of self-owned productive fixed assets

-

Estimated present market value of privately owned houses

-

Estimated present market value of other assets

-

Total household debts at the end of 2002

Rural:

-

Value of household fixed productive assets

-

The estimated value for self-owned house

-

Total value of all financial assets at the end of 2002

-

Total present value of durable goods (and furniture) (estimated)

-

Total debts of household at the end of 2002

1.9 Income

Urban (non-migrant):

-

Personal yearly income in 2002 (total income)

-

Subsidy for minimum living standard

-

Living hardship subsidies from work unit

-

Second job and sideline income

-

Monetary value of income in kind

Urban (migrant):

-

Total household income from working in cities and family production in 2002

Rural:

-

Individual total wage income

-

Total non-wage income of individual member

-

Annual net household income (total net income in 2002)

Appendix 2

See Tables 4, 5, 6 and Fig. 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Otis, N. Subjective Well-Being in China: Associations with Absolute, Relative, and Perceived Economic Circumstances. Soc Indic Res 132, 885–905 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1312-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1312-7