Abstract

Following an unprecedented boom, since 2008 Ireland has experienced a severe economic and labour market crisis. Considerable debate persists as to where the heaviest burden of the recession has fallen. Conventional measures of relative income poverty and inequality have a limited capacity to capture the impact of the recession in terms of social exclusion. This is exacerbated by a dramatic increase in the scale of debt problems including significant negative equity issues. Our analysis provides no evidence for individualization or class polarization of risk. Instead, while economic stress level is highly stratified in class terms in both boom and bust periods, the changing impact of class is highly contingent on life course stage. An income based classification showed that the affluent income class saw its advantage relative to the income poor class decline at the earliest stage of the life-course and remain stable across the rest of the life course. At the other end of the hierarchy, the income poor class experienced a relative improvement in their situation in the earlier life-course phase and no significant change at the later stages. For the remaining income classes, life-course stage was even more important. At the earliest stage the precarious class experienced some improvement in its situation while the outcomes for the middle classes remain unchanged. In the mid-life course the precarious and lower middle classes experienced disproportionate increases in their stress levels while at the later stage it is the combined middle classes that lost out. Additional effects over time relating to social class are restricted to the deteriorating situation of the petit bourgeoisie at the middle stage of the life-course. The pattern is clearly a good deal more complex than that suggested by conventional notions of ‘middle class squeeze’ and points to the distinctive challenges relating to welfare and taxation policy faced by governments in the Great Recession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Boom and Bust in Ireland

In this paper we focus on the impact of the Great Recession in Ireland on the distribution of economic stress across classes. In so doing we consider both social class differences employing the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) (Rose and Harrison 2006), and income class differences as the concept has featured in recent debates among economists (Gornik and Jäntti 2013). Ireland’s remarkable macro-economic fluctuations make it a particularly interesting case study of the distributional consequences of the Great Recession. Ireland experienced the fastest economic growth rates in the OECD during the first part of the so called ‘Celtic Tiger’ boom period from 1994 to 2000. Employment increased dramatically, long-term unemployment almost disappeared and significant immigration occurred. Blanchard (2002: 51) was led to conclude “I do not know the rules by which miracles are officially defined but this seems to come close”. This was followed by the period 2000–2007 when growth and employment expansion continued but was fuelled by excessive credit expansion and an unsustainable property boom (Nolan et al. 2014). From 2008 onwards an economic crisis emerged which had a more negative impact on national output than in any other OECD country. The combination of the global economic recession, the banking crisis, and the bursting of a domestic property bubble led to an unprecedented contraction in national output and income and to a fiscal crisis resulting in Ireland having to accept a ‘bail out’ from the European Central Bank, the European Union and the International Monetary Fund. Gross Domestic Product declined rapidly, the unemployment rate rose steeply from less than 5 % in 2007 to close to 15 % in 2012. Long term unemployment also rose steadily from less than 2 % to over 8 % in 2012. Many of those who retained their jobs also saw a decline in earnings and in net income due to wage cuts, particularly in the public sector, and tax increases (Callan et al. 2013).

Jenkins et al.’s (2013) comparative analysis of the impact of the Great Recession showed that the distributional effects reflect not only differences in the nature of the macroeconomic downturn but also in the manner in which cash transfers and direct taxes cushioned household net incomes from the full consequences of reductions in market incomes. Nolan et al. (2013) concluded that, while Ireland was one of the countries most affected by the downturn in relation to household income, focusing on the period 2008–2011, taxation, welfare and public sector pay changes were generally progressive. However, the direct employment effect of the recession resulted in higher than average losses for the bottom income decile. Considerable debate has persisted in Ireland regarding where the heaviest burden has fallen and where economic stress has been most keenly felt (Keane et al. 2014; Nolan et al. 2013; Social Justice Ireland 2013; TASC 2014).

2 Going Beyond Income Measures: Material Deprivation and Economic Stress

The fact that considerable disagreement continues to exist regarding the degree to which the costs of the recession have been distributed in an equitable manner is probably not unrelated to the limited capacity of conventional measures of relative income poverty and inequality to capture the impact of the scale and diversity of economic and social change that characterised both boom and bust in Ireland. The most widely employed relative income measure of poverty involves being below 60 % of median equivalized household income, which is a key EU social indicator intended to capture exclusion from ordinary, living patterns, customs and activities (Townsend 1979). This measure works best in a period of stability.Footnote 1 The volatility of absolute income levels in Ireland in the boom and the subsequent bust has undermined its usefulness. For the period 2004–2011 there was no clear trend in income poverty at 60 % of median household equivalent disposable median income (Watson and Maitre 2012). Similarly, the average Gini coefficient actually declined from 0.318 for the period 2004–2008 to 0.306 for 2009–2011. These results reflect the manner in which such measures capture the changing distribution of income rather than changes in command over resources (Nolan and Whelan 2011).

The need for a multidimensional perspective on the impact of the Great Recession is reinforced by the distinctive role of debt in the current recession with Ireland providing a particularly vivid example of the scale of such problems. A priori it seems plausible that the impact of such problems will be reflected in outcomes that go beyond current income and encompass changed material conditions and levels of economic stress. The question of the extent to which objective circumstances and the subjective experience of the Great Recession move in tandem is an empirical issue and one to which we pay particular attention.

Analysis of the Irish case is interesting not only because of the scale of the recession following a period of unprecedented boom but because the Irish component of the European Union Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) allows us to develop separate and reliable measures of material deprivation and economic stress for the period 2004–2011 enabling comparison of pre and post-recession outcomes.Footnote 2 Our primary focus is on changing patterns of economic stress but we pay particular attention to the extent to which such changes can be accounted for by corresponding changes in material deprivation.

3 Class and Life-Courses Perspectives on the Distributional Consequences of the Great Recession in Ireland

Our focus in exploring different perspectives on the distributional impact of the Great Recession in Ireland is largely on the potential impact of macro-economic changes relating to work, welfare and housing. However, we accept that politicians’ and policy makers’ anticipation of the electoral responses of particular socio-economic groups can clearly contribute to distributional outcomes. In the Irish case, claims of increased polarization have been made by a variety of social critics and the trade union movement who argue that the response of the state to the economic crisis has been deeply flawed, involving not only a failure to protect the vulnerable but the imposition of major sacrifices on those on low and middle incomes (Social Justice Ireland 2013; TASC 2012, 2014). These claims generally assumed that outcomes in the Irish case were broadly in line with the international trend towards increased income inequality (Piketty 2014) with consequences in terms of disparities in a range of social outcomes along the lines argued by Wilkinson and Pickett (2009).

In contrast the ‘individualization’ perspective suggests that a series of societal changes has undermined the salience of traditional stratification cleavages with higher levels of risk being more widely spread among segments of the population (Beck 1992). An important variant of this argument focuses on the emergence of new inequalities as a consequence of individualized life-course trajectories with hierarchical stratification structures such as social class considered to have a declining impact (Vandecasteele 2007, 2010; Pintelon et al. 2013). Increased concern with life-course risks has generally involved a focus on ‘new risks’ largely associated with entering and securing stability in the labour market and with care responsibilities primarily at the stage of family building (Taylor-Gooby 2004). However, given that our focus will be on household outcomes, the impact of the Great Recession in relation to the distribution of household debt provides further arguments for focusing on life-course variation. During the boom period the level of personal indebtedness in Ireland increased dramatically. Credit card debt per capita rose from €102 in 1996 to €707 in 2008, and the number of credit cards issues increased rapidly and the level of mortgage credit per capita increased over tenfold between 1995 and 2008 (Russell et al. 2012). Moreover at the peak of the boom the ratio of house prices to average earnings and loan to value ratios among first time buyers were exceptionally high (Kelly 2009). Since the onset of the economic crisis, mortgage arrears have grown steadily and the most recent figures show that 12.7 % of mortgage holders were in arrears for principal dwellings, as were a further 20.4 % of buy-to-let mortgages holders.Footnote 3 The scale of debt problems experienced by Irish households is exceptional in European terms. The CSO (2014a, b) Household Finance and Consumption Survey 2013 showed that the Irish figure of 56.8 % reporting debt is the fifth highest in the Eurozone. This includes all types of loans and credit and not just ‘problematic debt’. In 2011 the rate of mortgage/rent arrears among Irish households was the highest in the EU, standing at 11.6 % compared to 4.1 % across the EU28. Combining information on arrears in utility bills, hire purchase repayments and mortgage/rent, just less than 20 % of Irish households were in arrears in at least one of these categories compared to an average of 11.7 % for the EU28 (Eurostat, EU-SILC dabaseFootnote 4). Furthermore, McCarthy (2014) has shown that far from ‘mortgage distress’ being largely a consequence of increased unemployment, in 85 % of the case where arrears were reported the Head of Household was in employment. In an analysis of household consumption patterns Gerlach-Kristen (2013) concluded that the main burden of the Irish crisis has been borne by younger households. A CSO (2013) survey on financial effects of the downturn also found that households headed by a person aged less than 55 were much more likely to have made cutbacks in expenditure in the previous 12 months. The scale and wide distribution of mortgage arrears difficulties suggests that, if notions of individualization relating to life-course phase have increasing relevance, Ireland could prove to be an interesting test case.

A somewhat different interpretation of the Irish experience that incorporates increasing debt levels and negative equity, public sector pay cuts and pension levies, increasing progressivity in taxation and the difficulties being experienced by the self-employed has resulted in the notion of ‘middle class squeeze’ and the crisis of the ‘coping classes’ coming to have considerable resonance in popular debate in Ireland. This was reflected in the devotion of a special series in the influential Irish Times to the topic of ‘Ireland’s Squeezed Middle’. The term ‘middle class squeeze’ originates in the US.Footnote 5 There it refers to the relative decline in earnings of middling groups and to the depletion of their wealth as a result of ‘overspending’ in order to maintain established standards of living (PRC 2012). Such overspending is seen to be closely associated with easier access to credit.

In the analysis that follows we will provide an account of changing patterns of economic stress by income class, social class and the life course stage. We shall also seek to assess the extent to which class effects are mediated by material deprivation and related factors and are moderated by life-course stages (Whelan and Maître 2008; Vandecasteele 2010).

4 Income Class and Social Class

In pursuing the above issues, we draw on conceptions of ‘class’ developed by both economists and sociologists and seek to assess the extent to which doing so enhances our ability to understand changing patterns of economic stress in the Irish case. The theoretical conception of social class employed in this paper is that developed by Goldthorpe (2006) is based on two main principles of differentiation. The first is that of employment status. The second relates to the regulation of employment as a viable response to the weaker or stronger presence of monitoring and asset specificity problems in different work situations. It focuses on relational as well as distributive aspects of inequality. Individuals are understood to possess certain resources and experience a variety of constraints by virtue of the class positions they occupy. Goldthorpe and Jackson (2007: 528) stress that, while there is no inherent reason why income class and social class approaches should produce similar results, they suggest that, particularly where economist’s notion of ‘permanent income’ can be measured only in a ‘one-shot’ fashion, social class position may provide important additional information.

Similarly Atkinson and Brandolini (2013) have shown that, while social stratification by the class categories of the Goldthorpe schema and clustering by income are clearly correlated, the match is far from perfect. They note that, while both variables can contribute to identifying patterns of social stratification, their conceptual primacy varies across disciplines. As Gornik and Jännti observe (2013: 9), what economists refer to as the “middle class” might more accurately be described as those that fall in the “middle” of the income distribution. Within this income-based framework ‘class classifications’ have been developed in two ways (Gornik and Jännti 2013: 10). The first involves aggregating income bands into deciles or quintiles. With this approach the size of classes remain constant over time. Atkinson and Brandolini (2013: 78) note that the EU uses as its main income inequality measure the ratio of the income share of the top 20 % to that of the bottom 20 % and transfers away from the middle 60 % could, if made proportionately, leave measured income inequality unchanged. They are the “forgotten” middle. An alternative approach establishes class groups involving intervals defined by percentages of median household income (Atkinson and Brandolini 2013: 82). The economics literature is said to be “converging” (Ravallion 2010, 446) on the definition of the income limits for the middle income group as 75 and 125 % of the median. Atkinson and Brandolini (2013) note that we may either accept “the premise that middle-class living standards begin when poverty ends,” as Ravallion (2010, 446) states, or instead take a more conservative approach and fix a level so as “to ensure that the lower endpoint of the middle class represents an income significantly above the poverty level,” as suggested by Horrigan and Haugen (1988: 5). Atkinson and Brandolini (2013) note that in the EU, the former criterion would bring us to identify the lower bound with the at-risk-of-poverty line, set at 60 % of the median, whereas the second criterion would rationalize the 75 % cut off as defining the “margins” of poverty as plus a quarter of the at-risk-of-poverty line. The middle class can then be said to be those “comfortably” clear of being at-risk-of-poverty. They note that the rationale for the bottom cut off implies that there exists a “lower middle class,” comprised of people whose income is in the range of 75–125 % of the median and who are neither poor nor precarious. We could analogously postulate that there is an “upper middle class” between the “lower middle class” and the rich or affluent by taking the 125 % cut off, which is a quarter less than the income level that identifies the rich. The implicit “richness line” would equal 167 % of the median. This would amount to partitioning the population into five groups.

Obviously the number of categories identified and the labels attached to them is to some extent arbitrary and one may wish to employ different schemas. Here we will provide a set of analyses distinguishing 5 income categories as set out below

-

Less than 60 % of median equivalized income—income poor

-

60–75 % of median equivalized income—precarious income class

-

75–125 % of median equivalized income—lower middle income class

-

125–166 % of median equivalized income—upper middle income class

-

167 % of median equivalized income—affluent class

We have chosen to label those between 60 and 75 % of equivalized income as “precarious class” because of the evidence that this group are highly likely to experience frequent transitions into and out of poverty (Jenkins 2011).

5 Data and Measures

5.1 Data

Our analysis is based on data from the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) for Ireland which is a voluntary survey of private households carried out by the Central Statistics Office (CSO). The number of households in the completed sample varied from 4,300 to 6,000 between 2004 and 2011 and the number of individuals from 13,000 to 14,000. The analysis in this paper is conducted at the individual level and we use all the SILC waves from 2004 to 2011 for descriptive and modelling purposes. Our primary focus is on the comparison of pre-recession (2004–2008) and post-recession (2009–2011) using cross-sectional waves.Footnote 6 The analysis necessarily focuses on the impact of aggregate class categories over time and cannot take into account the movement of individuals between class categories. Significant change over time in the size of either income or class categories would complicate the interpretation of such effects. However, analysis available from the authors revealed extremely modest change over time in the distribution of income class and social class and the relationship between them. This of course does not exclude the possibility that the composition of classes, in particular income classes, may change over time. In the analysis that follows we consider the extent to which a range of factors mediate and moderate the relationship between economic and social class and economic stress.

The main alternative to the analysis that we have conducted would involve a peak to trough comparison focusing on the 2008 and 2011 waves. Such an analysis would miss out on a distinctive aspect of the Irish experience relating to the manner in which the economic crash was preceded by a substantial boom and had a variable impact across socio-economic groups.

Where household or household reference person (HRP) characteristics are involved these have been allocated to all household member.Footnote 7 Our key dependent variable is economic stress. Our central focus is on the manner in which the impact of the Great Recession on such levels is mediated by material deprivation, income class, social class, life-course and life-course related factors.

Below we provide information on the construction of key variables.

5.2 Economic Stress

The SILC survey asks questions of the person responsible for the accommodation in relation to household topics as well as to all individuals aged 16 and over for items such as labour market situation, health, personal income etc. For the purpose of this analysis we have identified several questions at household and individual level that are clearly related to economic stress. When the questions have been answered by the person responsible for the accommodation we attributed these answers to all household members. For the individual questions we attributed the answers of the household reference person (HRP) to all household members.Footnote 8 Our analysis therefore relates to the extent to which individuals are located in households experiencing economic stress.

Below we present the five items that our preliminary analysis indicated as appropriate for the measurement of economic stress and the corresponding questions on which they are based. The responses to each question are dichotomised.

-

The first item relating to ability to make ends meet is based on the following question. “A household may have different sources of income and more than one household member may contribute to it. Thinking of your household’s total income, is your household able to make ends meet, namely, to pay for its usual necessary expenses?” Seven possible answers were offered from “very easily” to “great difficulty” and responses indicating “great difficulty” or “difficulty” have been given a value of 1 while the remaining categories have been scored as zero.

-

Households were defined as having a problem with arrears (in the past 12 months) where they were unable to avoid arrears relating to mortgage or rent, or utility bills or hire purchase instalments. Those households experiencing such problems were given values of 1 while the remainder were scored as 0.

-

The indicator relating to the financial burden of total housing cost was based on the following question: “Thinking of your total housing costs including mortgage repayment or rent, insurance and service charges. To what extent are these costs a financial burden to you?” Three possible answers were offered and responses indicating a “heavy burden” or “somewhat of a burden” were scored as 1 while the remaining category was assigned a value of 0.

-

A further indicator of debt was captured by the question “Has the household had to go into debt within the last 12 months to meet ordinary living expenses such as mortgage repayments, rent, food and Christmas or back-to-school expenses?” A positive answer was scored as 1 while a negative one was assigned a value of 0.

-

Finally the indicator of ability to save was based on the question “Can you save some of your income regularly?” A negative answer was scored as 1 while a positive one was assigned a value of 0.

The reliability level of the simple additive economic stress measure, as captured by the Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.73 with modest variation across years.

In creating the stress index, following Desai and Shah (1988), each item is weighted by its prevalence weight in the population. Less frequently experienced stresses are allocated a proportionately greater weight. As we are analysing data from 2004 to 2011 we want to take account also of the changes over time in the relative contribution of constituent items to the overall stress. This produces a continuous variable which has then been ‘normalized’ to produce scores ranging from 0 to 1. A score of zero means that the individual is not stressed on any of the items while a score of 1 means that the individual is stressed on all items while intermediate scores reflect the pattern of stress responses and the prevalence weights at each point in time. Our choice of the prevalence weighting procedure and our decision to allow such weights to vary across time reflects our desire to capture changes in the underlying economic stress variable rather than the specific items included in the index.Footnote 9 The same procedure is employed in relation to the measure of deprivation we employ. Since the choice of thresholds for the dichotomous items making up the deprivation and stress scales necessarily involve the exercise of judgement, the prevalence weighting procedure has the advantage of adjusting for the distributional consequences of such decisions.

5.3 Household Income

The income measure employed throughout our analysis is annual disposable income adjusted for household size using the Irish modified equivalence scale.Footnote 10

5.4 Material Deprivation

The measure of material deprivation we employ comprises household and HRP items, as set out below, relating to enforced absence of life-style items. It excludes items that might more plausibly be understood as tapping economic stress rather than deprivation per se. Our analysis relates to the extent to which individuals are located in households experiencing material deprivation.

-

Two pairs of strong shoes

-

A warm waterproof overcoat

-

Buy new rather than second hand clothes

-

Eat meals with meat, chicken or fish (or vegetarian equivalent) every second day

-

Have a roast joint (or its equivalent) one a week.

-

Go without heating during the past twelve months

-

Keeping the home adequately warm

-

Replace any worn out furniture

-

Buy presents for family or friends once a year

-

Have family or friends for a drink or meal once a month

-

Have a morning, afternoon or evening out in the past fortnight for entertainment

Across the Irish SILC 2004–2011 waves the simple additive material deprivation index has a Cronbach alpha reliability of 0.82 with modest deviation across years.Footnote 11 In our subsequent analysis we employ a prevalence-weighted version of the deprivation measure with weights allowed to vary across years. The measure relates to the extent of deprivation experienced by the household in which the individual is located.

6 The Relationship Between Income Class and Social Class

In Table 1 we show the relationship between income class and social class aggregated across the 8 years of our analysis. For the income poor class a significant overlap with the ESeC class schema is reflected in the fact that two-thirds of this group were located in lower white collar and skilled manual and semi-unskilled manual and never worked classes. Less than one in ten were found in the higher and lower salariat. The social class profile for the precarious income class is remarkably similar to that for the income poor.

For the lower middle class we observe differences at both ends of the social class distribution with almost one in four being located in the salariat and just less than one in two in the lower white collar/skilled manual or semi/unskilled manual and never worked class. For the upper middle class, 40 % are located in the salariat and 30 % in the bottom two classes. For the affluent class, membership of the salariat predominates with close to 60 % being drawn from this class compared to 15 % for the bottom two classes. For the income poor and precarious classes the number located either in the salariat or the higher grade white and blue collar classes ranges from 17 to 21 %. It then rises to 37 % for the lower middle and to 57 % for the upper middle class and finally 74 % for the affluent class. The number drawn from the higher grade white and blue collar classes rises from 8 % for the income poor to 18 % for the upper middle class before declining slightly for the affluent class.

There is substantial overlap between the income class and ESeC schemas in their ability to capture a hierarchical dimension of social stratification. However, there is very little differentiation between the income classes in the inflow to these classes from the self-employed in agriculture and petit bourgeoisie. These latter groups are clearly characterised by considerable heterogeneity in terms of their distribution across income classes.

7 Trends in Household Income, Material Deprivation and Economic Stress by Income Class and Social Class

Before focusing on the multivariate analysis of economic stress we provide descriptive analysis of the scale of change over time in levels of household income, material deprivation and economic stress by income class and social class.Footnote 12 In Table 2 we show the breakdown of equivalised household income (adjusted to the 2011 Consumer Price Index), material deprivation and economic stress by income class and time period. In the period 2004–2008 the income class categorisation accounted for 44.5 % of the variance in household income. The average level of equivalised income ranged from €8,799 for the income poor category to €47,588 for the affluent class—a differential of 5.4:1. Overall there was little change in income levels between 2004–2008 and 2009–2011. However, the affluent class experienced a substantial drop in income adjusted for the consumer price index. At the other extreme the income poor class saw a modest decrease in their income level. The remaining classes experienced modest increases in their income levels. Focusing on absolute income levels there is no evidence of widening gaps between the income classes, despite the fact that the proportion of variance accounted for between income classes increased from 44.5 to 66.4 %. The significant reduction of within income class variance may be related to the reduction in the importance of market income relative to welfare income such as the impact of the recession on overtime and bonus earnings.Footnote 13 Similarly, absolute income differences as such provide no evidence of middle class squeeze.

The picture in relation to levels of material deprivation is somewhat different. Once again a clear hierarchical pattern was observed in the boom period with the level of deprivation ranging from 0.007 for the affluent class to 0.147 for the income poor class—a differential of over 20:1, reflecting the ability of the former class to almost entirely avoid such deprivation. In moving from the boom to the bust period, we observe a significant increase in the overall level of deprivation from 0.058 to 0.077. All income classes experience some increase. The sharpest increase of 0.036 and 0.032 are observed respectively for the precarious and lower middle classes. They are followed by the upper middle class with an increase of 0.017. Changes at the extremes are more modest involving an increase of 0.008 for the income poor and one of 0.004 for the affluent class. The overall effect of these changes is a small reduction in the proportion of variance accounted for by income class from 12.3 to 11.8 %.

For economic stress we also observe a clear hierarchical pattern with the level of stress in the first period ranging from 0.069 for the affluent class to 0.371 for the income poor—a differential of 5.4:1—identical to that for household income. An overall increase in the level of economic stress of 0.068 was observed. In this case the precarious and lower middle classes are more sharply differentiated from the remaining classes. The respective increases are 0.100 and 0.087. The next largest increases of 0.057 and 0.040 are observed respectively for the income poor and affluent classes. Unlike the situation in relation to material deprivation, the lowest increase in stress levels is observed for upper middle class. The overall effect of these changes is to reduce the proportion of variance accounted by differences between income classes from 15.5 to 13.5 %.

The material deprivation results point to a squeeze on the precarious class and the middle classes while the economic stress results suggest a narrower focus on the precarious class and lower middle class.

In Table 3 we set out the corresponding analysis relating to social class. Focusing first on equivalised income, we observe that in the boom period there is both a hierarchical effect and a property ownership influence which varies for the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. Income levels for the higher salariat were 2.2 times those for the semi-unskilled manual and never worked class. The next highest incomes are observed for the lower salariat and self-employed in agriculture class. The petit-bourgeoisie and the higher grade white and blue collar classes were at the lower end of the spectrum. Consistent with the income class analysis, the higher salariat experienced the sharpest reduction in their income, followed by the petit bourgeoisie and the higher grade white and blue collar class. Little change was observed for the two lowest classes while the lower salariat and farmers experienced more significant increases. The former is likely to reflect the protection from unemployment enjoyed by public sector workers. The economic fortunes of farmers are much less tightly linked to the domestic business cycle than is the case for other classes with farm income largely being drawn from farm subsidies and direct payments. In contrast to the income class situation, we observe an increase in the proportion of between class variation from 11.1 to 16.3 %.

Overall the analysis points to a reduction in income levels at the top of both the income class and social class hierarchy and little change at the bottom. However, while the income class analysis shows little change in the intermediate categories, social class analysis reveals a great deal of heterogeneity in this range. For the property owning classes we observe sharply contrasting experiences for agricultural and non-agricultural categories with farmers experiencing a significant improvement in their situation while the remaining proprietors saw their incomes fall. Similarly, while the lower salariat saw a modest increase in their income levels, the higher grade white collar and blue collar experienced a corresponding fall in their incomes, So while the income class analysis points to the reduction of the gap between the affluent class and all others, the social class outcomes point to a selective form of ‘middle class squeeze’.

For both material deprivation and economic stress the sharpest increases in moving from boom to bust are observed for the precarious and lowest income classes. Consistent with these findings, the most pronounced deterioration for both outcomes is observed for the petit-bourgeoisie and the higher and lower grade white and blue collar classes.

8 Multivariate Analysis of Economic Stress

In what follows we look at the factors associated with economic stress for all individuals included in the 2004–2011 surveys. Our dependent variable is the prevalence weighted stress variable with such weights being allowed to vary across year. For ease of interpretation the variable is “normalized” so that the scores run from 0 to 1.

When considering the impact of income class, social class and life course stage on economic stress we control for a range of potential mediators. Our models also included a dummy variable to capture the difference in levels of economic stress between 2004–2008 and 2009–2011. We also include an appropriate set of interaction terms to take into account the moderation of class effects by time period. As the dependent variable, economic stress, is continuous we estimate OLS regression models.Footnote 14

Since our independent variables are household characteristics and characteristics of the Household Reference Person (HRP), it implicitly assumes full sharing of resources within household. We note that the available evidence based on an analysis of the 2010 SILC module on within household distribution of resources broadly supports this assumption. In particular, there was no evidence that women suffered increased deprivation when they did not have an independent income (Watson et al. 2013).

In Table 4 the initial model contains only the period effect and shows that economic stress increased by 0.063 as the economy went from boom to bust. Model 2 adds both income class and social class. Five income classes are included in the model, with the affluent households (> 166 % median income) as the reference group. It also includes the interaction of the income class categories with period. For social class, on the basis of earlier analysis, interactions with period were restricted to the self-employed classes. The model provides estimates of the net effect of income classes controlling for social class and vice versa. For the period 2004–2008 economic stress is clearly stratified by income class. Compared to the most affluent class, economic stress levels of the income poor were 0.274 higher, for the precarious class the gap was 0.193, for the lower middle class 0.102 and 0.035 for the upper middle class. When we focus on change over time we observe significant increases for the precarious income group and the lower middle income group with changes over time for these groups being respectively 0.053 and 0.045 higher than for the affluent class. Changes over time for the income poor and the upper-middle class did not differ significantly from the affluent class.

The impact of social class is somewhat muted. This is in line with our expectation that such effects would operate to significant effect through income class, which is controlled for in the model.Footnote 15 Results for social class indicate that in the first period, stress levels were highest among the semi-unskilled manual and never worked classes and the lower services/sales occupations. The self-employed and the lower salariat did not differ significantly from the higher salariat reference group. The important social class changes relate to the self-employed classes. However, they operate in opposite directions for the agricultural and non-agricultural classes. For the former we see a decline in stress level of 0.057 while for the latter we see an increase of 0.057 which results in the net gap between this class and the semi-unskilled class being reduced from 0.087 (0.068 + 0.019) to 0.030. Unsurprisingly income groups and social class together account for a significant proportion of variance in economic stress at 17 %. Model 3 adds life course related variables to the model including age of head of household and presence of children. Housing tenure is also related to period in the life-course, with a higher proportion of older households falling into the ‘owned outright’ category and a higher percentage of younger households in the private-rented sector. Therefore housing tenure is added simultaneously with age and presence of children. The major contrast in the first period was between those in households where the HRP was over 65 and all others, with the difference ranging from 0.058 for the 45–54 age group to 0.072 for the 55–64 group. Over time, stress levels for the 45–54 age groups increased significantly with a coefficient of 0.032 being observed for the interaction between this age group and time period. A similar effect was observed for the 35–44 age group but the increase was just short of statistical significance.Footnote 16 We find that, controlling for all other factors, those in households with children reported significantly higher levels of economic stress (adding 0.040 to the stress score). The model fit statistics indicate that life course related factors (and their interactions with period) have a significant bearing on economic stress accounting for an additional 9.6 % of variance in stress scores when included in the model.

Consistent with the arguments outlined above in relation to housing debt and mortgage arrears, housing tenure is found to exert an independent influence on economic stress even when we control for income, class and other factors. Public sector tenants report the highest level of stress with a coefficient of 0.219. However they experienced no increase in economic stress over the second period. In the first period mortgage holders reported scores of only 0.028 higher than for outright home owners. However, they reported the steepest rise in economic stress over the period examined, experiencing an increase in stress score of 0.063. The introduction of the life course variables accounts for the changing impact of agricultural self-employment between periods. However, the changing pattern of life course influences had little impact on the remaining class effects.

In Model 4 we seek to take material circumstances into account. Of particular importance here is the material deprivation indicator. However, on the basis of further exploratory analysis, we also included the contrast between those drawing < 25 % of their income from social welfare and the changing impact of this contrast over time. In the first period those drawing more than 25 % of their income from welfare sources had net stress scores that were 0.058 higher than the remainder of the population. In the second period this had increased to 0.096. This effect provides a partial explanation of the fact that income classes and social classes at the peak of the respective hierarchies increased their relative advantage over a range of other classes. It also suggests an element of polarization which is not fully captured by income class and social class effects.

There was no additional period effect of having children in model 3. However, in model 4 when we control for deprivation and social welfare income those with children are shown to experience a higher rise in economic stress in the 2009–2011 period.

Adding the social welfare income and material deprivation variables explains a further 20.1 % of the variance, with the latter playing the major explanatory role, giving a total R2 of 0.470. In the boom period adding these variables reduces the income poor and precarious class effects by approximately half but has more modest effects for the differences between the middle classes and the affluent class. Their introduction also accounts for the increased effects for the income poor and precarious classes over time. We are left with net income class effects that are significantly reduced and that are uniform across period. However, taking these factors into account plays no role in accounting for the deteriorating situation of the petit bourgeoisie. Clearly the members of this class have experienced consequences of the recession which go beyond material deprivation.

9 The Interaction of Income Class and Life Course Effects

The analysis reported above provides an account of overall trends in the population as a whole. However, further analysis revealed significant pattern of interactions between class and life-course effects. This was particularly the case in relation to income class. In other words, class effects cannot be fully understood independently of life-course stage and vice versa. Exploratory analysis revealed the existence of a pattern of significant three way interactions between life course categories and income and social class. In order to present and facilitate this somewhat complex pattern of interactions involving a large number of dummy variables, in Table 5 we set out separate equations for three aggregated HRP age groups—those aged under 35 years, 35–64 years and 65 years and over. In each case we present the gross effects of income class and the changes between periods first and then report the net effects when social class and the range of controls included in our earlier analysis are introduced. From the first equation relating to HRPs younger than 35 we can see that the impact of being in the income poverty class and the precarious class actually declined over time with respective coefficients of −0.099 and −0.055, although only the former coefficient is statistically significant. In other words, the gap in stress levels between these classes and the affluent class narrowed over time. Since there was no evidence of significant negative change over time for the middle classes, indeed the interaction coefficients are positive, the two lowest income classes also improved their positions in comparison with these classes.

At this stage of the life-course, once we have controlled for income class effects, social class coefficients, with the exception of agricultural self-employment, are not statistically significant. This is likely to reflect the fact that many of the benefits of higher social classes only emerge over time as factors such as incremental scales, promotions and other forms of career advancement come into play, while advantages such as lower unemployment risks are already captured by income classes. It appears that welfare, taxation and labour market effects associated with recession and austerity eroded the advantage of the middle and affluent classes in this early life course group, while the lower income classes, which included a significant number of lone parents, who already had exceptionally high levels of economic stress in the boom period, found their relative disadvantage in stress reduced.

It is notable that it is at this stage of the life course that having children has the greatest effect on economic stress. Introducing social class and the control variables produces a modest reduction in the interaction coefficients between income and period to −0.077 for the income poor and −0.041 for the precarious group, with the former remaining statistically significant. It is notable that the coefficient for the interaction of non-agricultural self-employment with period is effectively zero for this age group.

For the middle life-course group a quite different situation is observed, with significant increase over time in the impact of being in the precarious class and the lower middle income class with respective coefficients of 0.059 and 0.064. Here, the pattern of coefficients is consistent with a ‘precarious class and lower middle class squeeze’ effect. Introducing social class and, in particular, material deprivation and social welfare dependence reduces these interaction effects to close to zero. In contrast with the situation for the youngest age group, the coefficient for the interaction of the petit bourgeoisie and time period of 0.066 is highly significant. Unlike the situation at the earlier stage of the life course, for this group, the net effects of being in the two lower social classes remains statistically significant. At this stage of the life course the increased impact over time of the HRP being in non-agricultural self-employment is highly significant even when controlling for a variety of other factors.

Finally, for the 65 + group we observe increases over time for the lower and upper middle classes with respective coefficients of 0.046 and 0.041 producing a ‘middle class squeeze’ profile. However, it should be noted that overall there was no change in the economic stress levels of this age group and there is no period effect for the affluent reference group. These results are observed in a context where income class effects account for a smaller proportion of variance for this age group compared to the younger ones; 5.4 % compared to just less than 20 %. This is in line with the decreased role of market outcomes at this stage of the life course. As with the younger age group the coefficient for the petit-bourgeoisie-time period interaction is close to zero. The “crisis” of the petit bourgeoisie is entirely a mid-life course phenomenon.

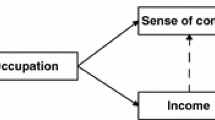

In order to provide a detailed picture of the impact of such effects, in Fig. 1 we document the predicted effects from the models relating to gross income class effects in Table 5. For the youngest age group we can see that for the income poor class, stress levels actually declined by 0.027. For the precarious class a modest increase of 0.020 was observed. The increases for the remaining classes were substantially higher ranging from 0.079 to 0.092. As a consequence, we observe a systematic narrowing of difference between the two lowest income classes and the middle and affluent classes. It is important to remember that the stress levels for these younger low income age groups are at both points in time at the upper end of the continuum but no significant deterioration in their situation is observed over time.

Focusing on the middle life course group, it is clear that economic stress increases for all income categories. The income poor category which had enjoyed an advantage over their younger counterparts in the first period report an increase of 0.068 and had an almost identical stress levels in the second period, 0.453 versus 0.459. However, the sharpest increases of 0.098 and 0.102 are observed for the precarious and lower middle classes respectively. For the upper middle and lower social classes the respective increases are 0.055 and 0.039. As a consequence of these changes the contrast between the income poor and precarious classes, evident in the early period, disappears while the contrast between the income poor and the lower middle group is substantially reduced. In contrast, the advantage enjoyed by the upper middle and affluent class increases with the difference in stress scores for the former going from 0.004 to 0.038 and for the latter from 0.011 to 0.043.

Finally, focusing on the older age groups we see that at both periods and for all income class categories stress scores are lower for this group. However, the pattern of change over time differs from that prevailing at other stages of the life-course. For the income poor and affluent classes stress levels actually decline over time. For the precarious class there is a modest increase and the sharpest increases of 0.028 and 0.022 are for the lower and upper middle classes respectively.

Over time we can see that life-course differences increased significantly in the affluent and upper middle classes and were reduced in the income poor class. For the lower middle class variation across time was modest. Finally, for the precarious class the gap between the youngest and middle age groups was eliminated. Both income class and life course position contribute to economic stress: stress scores range from 0.039 for the affluent older group (in period 2) to 0.486 for the youngest income poor group (in period 1)—a differential of 12.5:1. However, the manner in which they combine is far from straightforward and it is obvious that significant further exploration of the processes within life course groups is required to provide an adequate account of the underlying mechanisms.

10 Conclusions

The economic crisis has had a detrimental effect on the livelihoods of many Irish households. While rising unemployment and poverty are visible signs of the recession’s impact, it is likely that the effects of such an extensive decline in GDP and severe cuts in public expenditure have spread considerably further than those who have directly experienced job losses and income poverty. Increases in taxation, declining wages and hours of work, and reductions in state transfers have impacted across the social and income distribution, while mortgage arrears have spiralled among groups who were previously well protected from financial difficulties. The scale of these effects has led to questions as to the class and life-course distribution of the cost of the recession and the extent to which the burden has been disproportionately borne by specific social groups.

Relative income-poverty measures have failed to pick up the rising hardship because the general decline in income levels led to the poverty threshold falling in value. Here we have focused on economic stress while controlling for level of material deprivation and welfare dependency. Our analysis suggest that changes in stress levels between the boom and bust period for income class groups are largely accounted for by trends in material circumstances and their changing impact.

It is clear from our findings that economic stress was strongly influenced by social stratification factors for both of the time periods we have considered. There is no evidence that the increasing influence of life-course factors led to a diminution in the impact of either income class or social class. Instead we observe a pattern of interaction that shows the impact of each factor to be highly contingent on the situation in relation to the other.

The pattern of change over time cannot be accurately described as involving either individualization or polarization. The recession resulted in raised stress level for all income classes and social classes. The affluent class remained largely insulated from the experience of economic stress, however, it saw its advantage relative to the income poor class decline at the earliest stage of the life-course and remain stable across the rest of the life course. At the other end of the hierarchy, the income poor class experienced a relative improvement in their stress situation in the earlier life course phase and no significant change at the later stages. For the remaining income classes, life-course stage was even more important. At the earliest stage the precarious class experiences some improvement in its situation while the outcomes for the middle classes remain unchanged. In the mid-life course the precarious and lower middle classes experience disproportionate increase in their stress levels while at the later life-cycle stage it is the combined middle classes that lose out. Additional effects over time relating to social class are restricted to deteriorating situation of the petit bourgeoisie at the middle stage of the life-course.

Our analysis has provided clear evidence of the substantial impact of both class and life course effects or as they have been described as in the social investment literature—‘old’ and ‘new’ risks. However, rather than ‘old’ class related risks being displaced by ‘new’ life course risks, following Pintelon et al. (2013) and Whelan and Maître (2008), we observe a complex pattern of interaction in which income and class effects are conditional on phase of the life-course and vice versa. Understanding the changing role of class and life course factors is greatly facilitated by moving beyond a focus on income in order to develop a multi-dimensional perspective that encompasses material deprivation and economic stress.

Since 2011 there have been significant further cuts in public sector pay, and tax changes such as the introduction of a property tax and additional cuts in public sector pay introduced in 2013 (see Callan et al. 2013). These are not captured in the current analysis and may affect subsequent patterns of economic stress. The analysis also stops well before the labour market recovery observed in 2013 and the partial recovery in property values (CSO 2014a, b). Evaluation of the complex set of effects involved must await future analysis. Nevertheless, dealing with the potential political pressures arising from the unprecedented levels of economic stress for the precarious and lower middle income classes and the petit-bourgeoisie while sustaining the social welfare arrangements that have in significant part protected the income poor class, presents formidable challenges in terms of maintaining social cohesion and political legitimacy (Dellepiane and Hardiman 2012; Nolan et al. 2014).

Notes

Fixed poverty lines are a good deal more responsive to cyclical changes but have featured much less in European policy debates (Madden 2014).

Comparative analysis involving EU-SILC has tended to operate with measures of material deprivation that, in fact, encompass items that in terms of their manifest content appear to be more plausibly construed as indicators of subjective economic stress. For further discussion of these issues see (Whelan and Maître 2013).

Central Bank August 2013, Residential and mortgage Arrears Figures q2 2013.

Extracted 11/11/13.

For a detailed discussion of this notion see Kuz (2013).

The rotating nature of the SILC sample where individuals can be included in the sample for a maximum of four consecutive years together with substantial attrition problems in the Irish case mean that it is not possible to employ panel analysis to arrive at reliable conclusions relating to the impact of individual movement between classes.

In calculating standard errors we adjust for the clustering of individuals within households.

The household reference person is the person responsible for the accommodation. When the responsibility is shared the oldest person is chosen and in case of identical age, the HRP title is attributed to the male respondent.

In contrast to a simple additive measure which is uniform across years which would produce only 6 values for the stress variable the heterogeneous prevalence weighted procedures produces a continuous variable with 237 values.

The scale assigns the first adult in a household the value 1, each additional adult a value of 0.66 and each child a value of 0.33.

Factor analysis confirms that material deprivation and economic stress measures constitute two distinct dimensions.

Our analysis focuses on absolute rather than relative change. Further analysis allowing the impact of increases in material deprivation over time to vary across income class and social class provided no evidence of significant interactions that would suggest the need to employ a relative deprivation perspective rather than focusing on absolute change.

Peak to trough estimates involving comparisons of 2011 with 2008, which fail to capture significant increases between 2004 and 2008 show more substantial declines for all classes. However, the pattern of class differences in material deprivation and economic stress which are our primary focus remain broadly similar.

Our major focus is not the prediction of economic stress as such but further analysis shows that only 1.6 % of the predicted values are outside the range 0–1.

Income and social class jointly account for 16.1 % of the variance. 10 % is unique to income class and 1.5 % to social class with 4.6 % being shared between them. Thus 75.1 % of the social class effect is mediated by income class with 4.9 % being independent of the latter. Entering income class and social class separately produces patterns of coefficients comparable to those set out in Tables 2 and 3. For social class the largest positive coefficient is for the petit-bourgeoisie, followed by the intermediate & lower supervisory & technical & the lower services/sales/technical. The largest negative coefficient is for farmers with a more modest negative effect for the routine manual group and no significant effect for the never worked category. For income class the coefficients for the gross interactions of time period with the precarious and lower middle classes are almost identical to those observed when controlling for social class.

Non-significant interactions with age group are excluded.

References

Atkinson, A., & Brandolini, A. (2013). On the identification of the middle class. In J. C. Gornik & M. Jäntti (Eds.), Economic disparities in the middle class in affluent countries. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. London: Sage.

Blanchard, O. (2002). Comments and discussion. Brooking Economics Papers, 1, 58–66.

Callan, T., Nolan, B., Keane, C., Savage, M., & Walsh, J. R. (2013). Crisis, responses and distributional impact the case of Ireland. Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin. Working paper 456.

Central Statistics Office. (2013). Quarterly national household survey: Effect on households of the economic downturn quarter 3 2012. Cork: Central Statistics Office.

Central Statistics Office. (2014a). Quarterly national household survey quarter 4 2013. Cork: Central Statistics Office.

Central Statistics Office. (2014b). Household finance and consumption survey 2013. Cork: Central Statistics Office.

Dellepiane, S., & Hardiman, N. (2012). Governing the Irish economy: A triple crisis. In N. Hardiman (Ed.), Irish governance in crisis. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Desai, M., & Shah, A. (1988). An econometric approach to the measurement of poverty. Oxford Economic Papers, 40(3), 505–522.

Gerlach-Kristen, P. (2013). Research notes—Younger and older households in the crisis, quarterly economic commentary, Spring 2013. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute. http://www.esri.ie/UserFiles/publications/RN20130104.pdf.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (2006). Social class and differentiation of employment contracts. In J. H. Goldthorpe (Ed.), On sociology volume II second edition: Illustration and retrospect. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Goldthorpe, J. H., & Jackson, M. (2007). Intergenerational class mobility in contemporary Britain: Political concerns and empirical findings. British Journal of Sociology, 58(4), 526–546.

Gornik, J., & Jännti, M. (2013). Introduction. In J. C. Gornik & M. Jäntti (Eds.), Economic disparities in the middle class in affluent countries. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Horrigan, Michael W., & Haugen, Steven E. (1988). The declining middle class thesis: A sensitivity analysis. Monthly Labor Review, 111(5), 3–13.

Jenkins, S. P. (2011). Changing fortunes: Income mobility and poverty dynamics in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, S. P., Brandolini, A., Micklewright, J., & Nolan, B. (2013). The great recession and the distribution of household income. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keane, C., Callan, T., Savage, M., Walsh, J. R., & Colgan, B. (2014). Distributional impact of tax, welfare and public service wage policies: Budget 2015 and budgets 2009–2015. Dublin: Economic and Social Research.

Kelly, M. (2009) The Irish credit bubble. Working paper series WP09/32. Dublin: UCD Centre for Economic Research.

Kuz, B. (2013). Credit, consumption, and debt: Comparative perspectives. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 54(3), 183–186.

Madden, D. (2014). Health and wealth on the roller coaster: Ireland, 2003–2011. Social Indicators Research,. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0644-4.

McCarthy, Y. (2014). Dis-entangling the mortgage arrears crisis: The role of the labour market, income volatility and negative equity. Dublin: Barrington Lecture, Statistical and Social Inquiry Society,

Nolan, B., Callan, T., & Maître, B. (2013). Ireland. In S. Jenkins, A. Brandolini, J. Micklewright, & B. Nolan (Eds.), The great recession and the distribution of household income. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2011). Poverty and deprivation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nolan, B., Whelan, C. T., Calvert, E., Fahey, T., Healy, T., Mulcahy, A., et al. (2014). Ireland: inequality and its impacts in boom and bust. In B. Nolan, W. Salverda, D. Checchi, I. Marx, A. McKnight, I. G. Tóth, & H. van de Werfhorst (Eds.), Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pew Research Center (PRC). (2012). Fewer, poorer, gloomier: The lost decade of the middle class. Washington, D.C: Pew Social & Demographic Trends.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Pintelon, O., Cantillon, B., van den Bosch, K., & Whelan, C. T. (2013). The social stratification of social risks: Class and responsibility in the new welfare state. Journal of European Social Policy, 23(1), 52–67.

Ravallion, M. (2010). The developing world’s bulging (but vulnerable) middle class. World Development, 38(4), 445–454.

Rose, D., & Harrison, E. (2006). The European socio-economic classification: A new social class schema for comparative European research. European Societies, 9(3), 459–490.

Russell, H., Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2012). Economic vulnerability and the severity of debt problems: An analysis of the Irish EU-SILC 2008. European Sociological Review, 29(4), 695–706.

Social Justice Ireland. (2013). Who really took the hits during Ireland’s bailout? Dublin.

TASC. (2012). TASC’s proposal for a more equitable budget, Dublin.

TASC. (2014). Income Inequality in Ireland. Think-tank for Action on Social Cahnge: Dublin.

Taylor-Gooby, P. (2004). New Risks and Social Change. In P. Taylor-Gooby (Ed.), New risks, new welfare: The transformation of the European welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Vandecasteele, L. (2007). Dynamic inequalities: The impact of social stratification determinants on poverty dynamics in Europe. Ph.D. Dissertation, Catholic University Leuven, Belgium.

Vandecasteele, L. (2010). Poverty trajectories after risky life course events in different European welfare regimes. European Societies, 12(2), 257–278.

Watson, D. & Maitre, B. (2012) Technical paper on poverty indicators. Appendix C Report of the Review of the National Poverty Target.

Watson, D., Maitre, B., & Cantillon, S. (2013). Implications of income pooling and household decision-making for the measurement of poverty and deprivation: An analysis of the SILC 2010 special module for Ireland. Social inclusion technical paper no. 4. Dublin: Department of Social Protection.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2008). “New” and “Old” social risks: Life cycle and social class perspectives on social exclusion in Ireland. Economic and Social Review, 39(2), 131–156.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2013). Material deprivation, economic stress & reference groups: An analysis of EU-SILC 2009. European Sociological Review, 29(6), 1162–1174.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why more equal societies almost always do better. London: Allen Lane.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the comments of two anonymous referees as well as from the participants at seminars at the Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin, at the Social Protection Policy Workshop at the Geary Institute for Public Policy, University College Dublin, at Nuffield College Oxford and the 2014 annual conference of the European Consortium for Sociological Research. This journal article was derived from work done within the research programme for the Analysis and Measurement of Poverty and Social Exclusion funded by the Department of Social Protection under the Irish National Action Plan for Social Inclusion 2007–2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whelan, C.T., Russell, H. & Maître, B. Economic Stress and the Great Recession in Ireland: Polarization, Individualization or ‘Middle Class Squeeze’?. Soc Indic Res 126, 503–526 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0905-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0905-x