Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among gratitude, social support, coping style, and well-being. In total, 750 undergraduate participants completed four inventories measuring the variables of interest. Analyses of structural equation modeling found that gratitude had direct effects on undergraduates’ active coping styles, social support, and well-being. In addition, gratitude had indirect effects on undergraduates’ well-being via an active coping style and social support, and social support had direct effects on undergraduates’ active coping styles. These results support the proposed model of well-being and contribute to the understanding of how gratitude influences undergraduates’ well-being via interpersonal and cognitive variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Well-being, usually defined as an integration of general life satisfaction and positive emotions, is also regarded as happiness (Brulde 2007; Diener et al. 2002; Karlson et al. 2013). According to a survey of 2,345 American adults in April 2013, two-thirds of Americans, especially undergraduates, were unhappy. Along the same line, studies have shown that over half of Korean undergraduates do not have a happy university life (John Tung Foundation 2008). This finding suggests that undergraduates’ well-being is suffering (Berger et al. 2011; Stupnisky et al. 2013). The well-being of undergraduates is critical to their academic success (Berger et al. 2011; Potter 2010; Salami 2010; Suldo et al. 2011; Turashvili and Japaridze 2012; Ye et al. 2012). Thus, the factors influencing undergraduates’ well-being are worth understanding.

Gratitude is a disposition of feeling and expressing thankfulness consistently over time and across situations (Emmons and Crumpler 2000). Studies have shown that gratitude is a predictor of well-being (e.g., Hill and Allemand 2011; Martínez-Martí et al. 2010; Nelson 2009; Wood et al. 2007). However, mechanisms relating trait gratitude to well-being have not been systematically explored. Previous research has suggested two gratitude-specific hypotheses: the schematic hypothesis and the coping hypothesis. The coping hypothesis proposes that grateful people are more likely to use both instrumental and emotional social support, and these people tend to employ more active coping strategies (Wood et al. 2010). This observation suggests that social support and coping style may be two important mediators between gratitude and well-being. Social support is the interpersonal process of providing or exchanging resources (Gabert-Quillen et al. 2011). Coping styles are the strategies people employ to manage behaviors, emotions, and cognitions when they feel stressed (Thomas et al. 2011). Although these two concepts are well researched, the ways in which they are related to gratitude are still unclear (Wood et al. 2007). Moreover, although studies on the emotional benefits of gratitude have been increasing, the relationship between gratitude and undergraduates’ well-being is seldom explored. This study therefore aimed to understand how gratitude may influence undergraduates’ well-being via social support and coping styles.

2 Gratitude, Social Support, Coping Style, and Well-Being

2.1 Gratitude and Social Support

Gratitude is considered a subjective feeling of thankfulness and appreciation for life and is usually regarded as a pleasant feeling that occurs when an individual receives a favor or benefits from others (McCullough et al. 2001). As a psychological state, gratitude is also considered to be a disposition, defined by the tendency to respond with grateful emotions to other people’s generosity and the ways in which others contribute to positive experiences and outcomes in one’s life (McCullough et al. 2002).

Schwarzer and Knoll (2007) defined social support as the degree to which individuals are socially embedded: when individuals perceive social support, they have a sense of belonging, obligation, and intimacy. In addition, social support refers to the quality of social relationships, such as the perceived availability of help or actual support received. Gabert-Quillen et al. (2011) suggested that social support is a process of providing or exchanging perceived resources with other people. The most frequently investigated types of social support have been emotional or appraisal support (e.g., offering reassurance and listening empathetically), informational support (e.g., giving advice), instrumental or tangible support (e.g., assisting with a problem or giving money), and belonging or companionship support (e.g., spending time with) (Gabert-Quillen et al. 2011; Schwarzer and Knoll 2007).

It has been found that gratitude leads to a higher level of perceived social support and lower levels of stress and depression (Coursaris and Liu 2009; Wood et al. 2008). The positive relationship between gratitude and social support can be observed in the feelings of being cared for, loved, and highly esteemed (McCullough and Tsang 2004). Grateful individuals typically act prosocially to express their gratitude, and such prosocial actions, in the long run, facilitate social bonds and friendships (Harpham 2004). Accordingly, feeling grateful should have positive effects on social support.

2.2 Gratitude and Coping Style

Thomas et al. (2011) suggested that coping styles are strategies to manage behaviors, emotions, and cognitions when one feels stressed. Various categories of coping styles have been proposed, such as the 2 × 2 matrix model: direct/active, direct/inactive, indirect/active, and indirect/inactive; the two-type model: active versus passive coping; and the three-type model: problem-focused (e.g., active coping and planning), adaptive emotion-focused (e.g., positive reinterpretation and acceptance), and maladaptive emotion-focused (e.g., denial and mental disengagement) (Boehmer et al. 2007; Carver et al. 1989; Thomas et al. 2011).

According to the broaden-and-build theory, positive emotions are adaptive mechanisms that broaden the thought-action repertoire and improve cognitive ability (Fredrickson and Branigan 2005). Gratitude is a positive emotion (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006; Tsang 2006). Many researchers (e.g., Fredrickson 2004; Fredrickson et al. 2003) have suggested that gratitude, like other positive emotions, may broaden the scope of cognition and enable flexible thinking, which facilitates effective methods of coping with stress and adversity and leads to improved coping skills over time. In addition, grateful people tend to focus on the positive aspects of life (Adler and Fagley 2005), which may be reflected in their use of more active and adaptive coping strategies. Therefore, gratitude should have effects on undergraduates’ coping style.

2.3 Gratitude and Well-Being

Ryan and Deci (2001) posited that well-being is derived from two philosophical traditions: the hedonic approach and the eudaimonic approach. The hedonic approach emphasizes that well-being depends on obtaining pleasure and avoiding pain, whereas the eudaimonic approach conceptualizes well-being as the extent to which an individual is fully functioning (Kjell 2011). Although there are many ways to evaluate the pleasure/pain continuum in human experience, the hedonic approach is influential in the well-being approach (Boniwell 2007). Many researchers (e.g., Diener 2000; Schimmack 2003; Suh et al. 1998) have claimed that well-being involves both cognitive and affective components: evaluating one’s life positively (life satisfaction) and experiencing relatively more positive than negative emotions (affect balance). In other words, well-being is a combination of general life satisfaction and the presence of positive emotions (Brulde 2007; Diener et al. 2002; Karlson et al. 2013).

Many studies have found that gratitude is linked to well-being. For example, Hill and Allemand (2011) found that grateful and forgiving adults reported greater well-being in adulthood. Similarly, Watkins et al. (2003) found that individuals who scored higher in grateful personality traits reported more life satisfaction, higher subjective well-being, and more positive emotions than their less grateful counterparts. Experimental studies have also found that gratitude interventions, such as gratitude journals (Emmons and McCullough 2003), gratitude exercises (Seligman et al. 2005), and count-your-blessings exercises (Chan 2010), significantly improved individuals’ well-being. These empirical findings suggest that there is a causal relationship between gratitude and well-being.

2.4 How Gratitude Indirectly Influences Well-Being

Gratitude may influence well-being via social support. Watkins (2004) asserted that gratitude increases happiness by intensifying a number of benefits in an individual’s life. In particular, gratitude may increase happiness by enhancing a person’s social relationships. Research has also suggested that well-being is related to the quality of an individual’s friendships and social contacts (Sarason and Sarason 2009; Myers 2000). Expressions of gratitude may result in social support, which may, in turn, facilitate long-term well-being.

Gratitude may also influence well-being in that the practice of gratitude serves as an effective coping mechanism. When a person views life as a gift, that person is able to find benefits even in unpleasant circumstances (Watkins 2004). Based on the broaden-and-build theory, which argues that positive emotions broaden mindsets and build enduring personal resources, Emmons and McCullough (2003) argued that gratitude is effective in increasing well-being because it builds psychological and social resources. Furthermore, it has been found that coping strategies mediate the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction: gratitude may help an individual cope with stressful life events, which enhance that individual’s well-being in the long run (Wood et al. 2007).

As for the relationship between social support and coping style, the transactional stress theory (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) suggests that social support is a protective factor that influences the cognitive appraisal of stressful events. Empirical findings have also demonstrated that social support is one of the most important noncontextual factors that influence coping strategies (e.g., Devonport and Lane 2006). However, social support may only foster certain types of coping strategies. Study findings have demonstrated that social support is positively related to active coping (Hall et al. 2011; Shen 2009) but negatively associated with avoidant coping (Boehmer et al. 2007). Avoidant coping involves responses that manage potentially threatening emotions by diverting attention away from the threat (Thomas et al. 2011). Many studies have also found that individuals with high social support tend to use problem-focused coping strategies, whereas individuals with low social support tend to employ emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g., Bolger and Amarel 2007; Pakenham and Bursnall 2006). Accordingly, gratitude may influence people’s well-being via two mechanisms: social support and an active coping style such that social support may enhance a person’s active coping skills, which, in turn, facilitates his or her well-being.

2.5 Proposed Model of This Study

This study proposes a model of how gratitude influences undergraduates’ well-being via social support and active coping styles. Well-being is often operationalized as hedonic balance through a global measure obtained when a negative affect is subtracted from the sum of positive affect and satisfaction with life (e.g., Schimmack et al. 2008; Sheldon and Hoon 2007; Vitterso 2001). Moreover, the instrument employed to measure well-being in this study is negatively correlated with negative emotions (r = −.422, p < .001) (Lin 2011, unpublished doctoral dissertation). Additionally, passive coping has been found to be negatively correlated with gratitude (e.g., Wood et al. 2007), social support (e.g., Boehmer et al. 2007; Chao 2011; Greenglass 1993; Manne et al. 2005), and well-being (e.g., Chao 2011; Elliot et al. 2011; Cicognani 2011; Frydenberg and Lewis 2009; Litman and Lunsford 2009; Pottie and Ingram 2008; Shiota 2006; Smedema et al. 2010; Turashvili and Japaridze 2012; Varni et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2012). As such, negative emotions and passive copying styles were not included in the model proposed in this study.

The present study hypothesizes that in the proposed model, gratitude will have direct effects on undergraduates’ active coping styles, social support, and well-being. Furthermore, this model proposes that gratitude will have indirect effects on undergraduates’ well-being via an active coping style and social support and that social support will have direct effects on undergraduates’ active coping styles.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Participants were 750 undergraduates sampled from 10 universities. Of the total, 43.9 % of the participants were from private universities, and 56.1 % of the participants were from public universities. With a mean age of 20.31 years (SD = 1.07), the participants included 264 males (35.2 %) and 486 females (64.8 %).

3.2 Instruments

3.2.1 The Inventory of Undergraduates’ Gratitude (IUG)

The IUG, developed by the researchers (Lin and Yeh 2011), was employed to measure the participants’ gratitude traits in this study. The IUG was a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree.” With a total of 26 items, the IUG included five factors: thank others (7 items), thank God (5 items), cherish blessings (5 items), appreciate hardship (5 items), and cherish the moment (4 items). The test items included statements such as “I thank others for what they have done for me in daily life.” Exploratory factor analysis indicates that 50.18 % of the total variance is explained. The Cronbach’s α coefficients were .930, .844, .824, .796, .750, and .742 for the IUG and for the five factors listed above, respectively. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the IUG had good construct validity; χ2(N = 214) = 1,612.25 (p < .05); goodness-of-fit (GFI) = .86, adjusted goodness-of-fit (AGFI) = .83, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .078, and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) = .049; normed fit index (NFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and relative fit index (RFI) were above .90; and Parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI) and Parsimonious goodness-of-fit Index (PGFI) were above .50.

3.2.2 The Inventory of Social Support (ISS)

The ISS, developed by the researchers (Lin 2011, unpublished doctoral dissertation), was employed to measure the participants’ level of social support in this study. The ISS was a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “never” to “always.” With a total of 18 items, the ISS included two factors: emotional-companion support (11 items) and informational-tangible support (7 items). The test items included statements such as “When I felt depressed, they (important others) encouraged me.” Exploratory factor analysis indicated that the total variance explained was 58.72 %. The Cronbach’s α coefficients were .951, .948, and .864 for the ISS and for the two factors, respectively. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the ISS had good construct validity; χ2(N = 214) = 1041.07 (p < .05); GFI = .87, AGFI = .83, RMSEA = .095, and SRMR = .041; NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI, and RFI were above .90; and PNFI and PGFI were above .50.

3.2.3 The Inventory of Coping Style (ICS)

The ICS, developed by the researchers (Lin 2011, unpublished doctoral dissertation), was employed to measure the participants’ types of coping style in this study. The ICS was a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “never” to “always.” With a total of 24 items, the ICS included four factors: problem-focused active coping (8 items), problem-focused passive coping (5 items), emotion-focused active coping (5 items), and problem-focused passive coping (5 items). The test items included statements such as “When I encountered a problem, felt depressed, or felt pressured, I tried to use different methods to solve the problem.” Exploratory factor analysis indicated that the total variance explained was 45.20 %. The Cronbach’s α coefficients were .822, .837, .818, and .791 for the four factors, respectively. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the ICS had good construct validity; χ2(N = 214) = 1,063.05 (p < .05); GFI = .89, AGFI = .87, RMSEA = .067, and SRMR = .054; NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI, and RFI were all above .90; and PNFI and PGFI were above .50.

3.2.4 The Inventory of Well-Being (IWB)

The IWB, developed by the researchers (Lin 2011, unpublished doctoral dissertation), was revised from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985) and Long-term Affect (Diener et al. 1995). The IWB was employed to measure the participants’ perceived well-being in this study; it was a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree.” With a total of 10 items, the IWB included two factors: life satisfaction (5 items) and positive emotion (5 items). The test items included statements such as “I am satisfied with my current life.” Exploratory factor analysis indicated that the total variance explained was 63.64 %. The Cronbach’s α coefficients were .898, .891, and .868 for the IWB and for the two factors, respectively. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the IWB had good construct validity; χ2(N = 214) = 168.87 (p < .05); GFI = .96, AGFI = .93, RMSEA = .076, and SRMR = .041; NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI, and RFI were above .90; and PNFI and PGFI were above .50. Moreover, IWB was negatively correlated with negative emotions (r = −.422, p < . 001).

3.3 Procedures and Data Analyses

All inventories in this study were administered in university classes by the professor who was teaching the course. No time limit was posed; however, all participants completed the inventories within 15 min. All data were collected during a two-month period. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to explore the relationships among gratitude, active coping style, social support, and well-being.

4 Results

4.1 Goodness-of-Fit of the Proposed Model

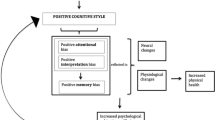

Bagozzi and Yi (1998) suggested that three indices should be employed to examine the goodness of fit of a model. These indices are preliminary fit criteria, overall model fit, and the fit of the internal structure of the model. The present study employed these indices to investigate the goodness-of-fit of the proposed model. Analyses considering these aspects revealed that all estimated parameters in this study met the criteria proposed by Bagozzi and Yi. The important values of the model are shown in Fig. 1.

Following the suggestion of Hair et al. (2006), we employed three dimensions of indices to examine the overall model fit of the proposed model in this study. These indices were absolute fit measures, relative fit measures, and parsimonious fit measures. The absolute fit measures suggested that the model was not a good fit: χ2 (N = 750) = 321.79, p = .000. However, the χ2 test is sensitive to sample size; the other indices should be considered to make an overall judgment (Hair et al. 2006). In the present study, whereas GFI (.93) and SRMR (.04) reached the ideal criteria, AGFI (.87) and RMSEA (.10) were acceptable. As for the relative fit measures, the NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI, and RFI were all greater than .95, indicating a good fit. Finally, from the perspective of the parsimonious fit measures, PNFI (.67) and PGFI (.53) were all greater than the ideal value of .50. Overall, analyses of the overall model-fit measures suggest that the proposed model is acceptable.

4.2 Fit of Internal Structure of the Model

The following four criteria were employed to examine the fit of internal structure of the model proposed in this study: (1) the individual item reliability is greater than .50, (2) the latent variable composite reliability is greater than .50, (3) the extracted average variance of the latent variable is greater than .50, and (4) all factor loadings of estimated parameters are significant (Bagozzi and Yi 1998). The findings of the current study revealed that all individual items’ measures of reliability except life satisfaction (.49) were greater than .50 (range .50–.88), the composite measures of reliability ranged from .69 to .93, and the extracted average variances ranged from .53 to .88. These findings indicate that the model exhibited a good fit of internal structure.

4.3 Analyses of Direct Effects, Indirect Effects, and Explained Variance

All of the direct effects were significant. The direct effects of gratitude on social support, coping style, and well-being were .597, .586, and .428, respectively, ps < .001; the direct effects of social support on coping style and well-being were .139 and .208, respectively; and the direct effect of coping style on well-being was .300. The indirect effect of gratitude on well-being was .325, p < .001. The overall effect of gratitude on social support, coping style, and well-being was .597, .669, and .753, respectively, ps < .001; and that of social support on coping style and well-being was .139 and .250, respectively, ps < .01. Finally, the overall effect of coping style on well-being was .300, p < .001.

In addition, Fig. 1 shows that the residual variance of social support was .644, indicating that gratitude explained 35.6 % of the variance in social support; the residual variance of coping style was .540, indicating that gratitude and social support explained 46.0 % of the variance in coping style; and the residual variance of well-being was .345, indicating that gratitude, social support, and coping style jointly explained 65.4 % of the variance in well-being.

5 Discussion

As suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1998), this study employed three indices to examine the goodness of fit of the proposed model: preliminary fit criteria, the overall model fit, and the fit of the internal structure of the model. Overall, the findings in this study suggest that the model has a good fit. In other words, the study’s hypotheses regarding the relationships among gratitude, social support, active coping style, and well-being are fully supported. Three conclusions can be made.

First, grateful undergraduates tend to have a higher degree of emotional-companion and informational-tangible social support; such forms of social support not only have a direct influence on the students’ well-being but also indirectly influence their well-being. This conclusion is in line with the findings that, over time, gratitude leads to a higher level of social support (e.g., Roberts 2004; Seligman et al. 2005; Wood et al. 2008). The underlying mechanisms of this relationship may be the feelings of being loved, cared for, and valued, as well as prosocial behaviors. McCullough et al. (2002) claimed that viewing oneself as the beneficiary of others’ generosity may lead one to feel esteemed and valued, which further strengthens self-esteem and perceived social support. Moreover, it has been suggested that grateful people usually act prosocially to express their gratitude, which enhances social bonds and friendships in the long run (Harpham 2004).

The findings in this study align with previous research demonstrating that social support has an impact on well-being (Gencoz and Ozlale 2004; Sheldon and Hoon 2007; Kaniasty 2011). Kaniasty (2011) found that perceived social support had significant associations with indicators of psychosocial well-being. Nahum-Shani et al. (2011) also found that receiving emotional support is associated with enhanced well-being when the individual perceives the supportive exchange as reciprocal. Positive correlations between social support and well-being have also been found in studies of serious health problems, bereavement, terror events, and daily stressful conditions (Cheng et al. 2010; Sarason and Sarason 2009). Social support may decrease self-defensive behavior and allow for flexibility in interpersonal conflicts, contributing to personal growth and well-being (Mikulincer and Shaver 2009). In addition, social support provides hope, increases self-confidence, and is an important buffer against loneliness and stress (Sarason and Sarason 2009). Notably, Siewert et al. (2011) found that social support was related to higher levels of well-being, and emotional support was more influential than practical and informational support. The present study, however, found that both types of social support are equally important to undergraduates’ well-being, as evidenced by their identical loading (.94) in the model. Therefore, the proposed route of gratitude–social support–well-being is supported by the SEM analyses.

The second conclusion that the present findings support is that grateful undergraduates tend to employ active problem-focused coping as well as active emotion-focused active coping, which facilitates their well-being. This argument lends support to the claim that gratitude leads to a more adaptive coping style (Wood et al. 2007) and that an adaptive coping style enhances well-being (Crockett et al. 2007). Gratitude is an effective coping mechanism for dealing with stressful events (Adler and Fagley 2005). Grateful people are inclined to view the world as a pleasant place and to take time to focus on the positive aspects of life (Adler and Fagley 2005; Watkins et al. 2003). This positive perception of the world may lead to an increased willingness to actively address problems. Moreover, gratitude is a positive emotion (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006). According to the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson and Branigan 2005), positive emotions facilitate an upward spiral toward optimal functioning and enhance emotional well-being by broadening the scope of an individual’s habitual thoughts and actions (Fredrickson and Joiner 2002). By broadening these thoughts and actions, the positive emotion of gratitude improves coping and builds resilience. Furthermore, these improvements enhance the individual’s experience of positive emotions and well-being (Fredrickson 2004). The proposed route of gratitude–active coping style–well-being in the model is therefore consistent with previous findings.

A third conclusion that can be drawn from the current study is that grateful undergraduates tend to have a high degree of emotional-companion and informational-tangible social support. This social support, in turn, has an indirect influence on students’ well-being by increasing the use of an active coping style. This conclusion lends support to the finding that gratitude is related to higher levels of satisfaction with life, happiness, and positive emotions (e.g., Chan 2010; Kashdan et al. 2006; Fredrickson et al. 2003) and the suggestion that gratitude has a causative influence on well-being (Chan 2010; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005; McCullough et al. 2004). Moreover, the findings in this study support that coping style mediates the relationship between social support and well-being (Wu et al. 2011) and that social support enhances active coping skills (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). In addition, previous studies have indicated that social support is a crucial factor influencing positive coping in times of stress (e.g., Devonport and Lane 2006; Linley and Joseph 2004). Accordingly, the proposed route of gratitude–social support–coping style–well-being in the model integrates the results of related previous findings.

6 Conclusions and Suggestions

Gratitude is regarded as an important human virtue. Recently, there has been a renewed interest in the empirical study of gratitude, especially the consequences of gratitude. This study proposes an integrative model for gratitude and well-being based on related findings and theories. The findings in this study add to existing theories on the subject by describing the mechanisms by which gratitude is related to undergraduates’ well-being. The findings of this study suggest that gratitude, social support, coping style, and well-being are interrelated. The present findings also suggest that gratitude influences well-being directly and indirectly through social support and coping style via the aforementioned three routes. All three of the proposed routes are supported by the SEM analyses. Social support and active coping style are important mechanisms that explain the ways in which gratitude influences undergraduates’ well-being. Therefore, this study contributes to an understanding of the way gratitude influences undergraduates’ well-being via interpersonal and cognitive variables.

Although this study is a correlational study, it is conducted with a large sample. Additionally, the model’s goodness-of-fit indices suggest that the proposed model is reliable. These patterns can therefore provide important references for college instructors and researchers who endeavor to improve undergraduates’ well-being by fostering gratitude. Further studies should focus on alternative mechanisms by utilizing experimental designs to enrich the path models supported by the present study. Moreover, the causal effects suggested in this study can be further confirmed through experimental studies. Intervention studies have suggested that gratitude journals and gratitude exercises (e.g., Hill and Allemand 2011; Chan 2010) can significantly enhance well-being. Similar interventions may be employed to observe whether such interventions can facilitate undergraduates’ social support and active coping skills, thereby further enhancing their well-being.

References

Adler, M. G., & Fagley, N. S. (2005). Appreciation: Individual differences in finding value and meaning as a unique predictor of subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 73(1), 79–114.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1998). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Academy of Marking Science, 16, 76–94.

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17(4), 319–325.

Berger, C., Alcalay, L., Torretti, A., & Milicic, N. (2011). Socio-emotional well-being and academic achievement: Evidence from a multilevel approach. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 24(2), 344–351.

Boehmer, S., Luszczynska, A., & Schwarzer, R. (2007). Coping and quality of life after tumor surgery: Personal and social resources promote different domains of quality of life. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 20(1), 61–75.

Bolger, N., & Amarel, D. (2007). Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: Experimental evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 458–475.

Boniwell, I. (2007). Developing conceptions of well-being: Advancing subjective, hedonic and eudaimonic theories. Social Psychology Review, 9, 3–18.

Brulde, B. (2007). Happiness and the good life: Introduction and conceptual framework. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 1–14.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283.

Chan, D. W. (2010). Gratitude, gratitude intervention and subjective well-being among Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 30(2), 139–153.

Chao, R. C.-L. (2011). Managing stress and maintaining well-being: Social support, problem-focused coping, and avoidant coping. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 338–348.

Cheng, S. T., Lee, C. K. L., & Chow, P. K. Y. (2010). Social support and psychological well-being of nursing home residents in Hong Kong. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(7), 1185–1190.

Cicognani, E. (2011). Coping strategies with minor stressors in adolescence: Relationships with social support, self-efficacy, and psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(3), 559–578.

Coursaris, C. K., & Liu, M. (2009). An analysis of social support exchanges in online HIV/AIDS self-help groups. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 911–918.

Crockett, L. J., Iturbide, M. I., Torres, R. A., McGinley, M., Raffaelli, M., & Carlo, G. (2007). Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(4), 347–355.

Devonport, T. J., & Lane, A. M. (2006). Relationships between self-efficacy, coping and student retention. Social Behavior and Personality, 34, 127–138.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 63–73). New York: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 130–141.

Elliot, A. J., Thrash, T. M., & Murayama, K. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of self-regulation and well-being: Avoidance personal goals, avoidance coping, stress generation, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 79(3), 643–674.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 56–69.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19(3), 313–332.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175.

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376.

Frydenberg, E., & Lewis, R. (2009). Relations among well-being, avoidant coping, and active coping in a large sample of Australian adolescents. Psychological Reports, 104(3), 745–758.

Gabert-Quillen, C. A., Irish, L. A., Sledjeski, E., Fallon, W., Spoonster, E., & Delahanty, D. L. (2011). The impact of social support on the relationship between trauma history and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in motor vehicle accident victims. International Journal of Stress Management, 19(1), 69–79.

Gencoz, T., & Ozlale, Y. (2004). Direct and indirect effects of social support on psychological well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 32(5), 449–458.

Greenglass, E. R. (1993). The contribution of social support to coping strategies. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 42(4), 323–340.

Hair, J. F., Jr, Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Hall, P. A., Marshall, J., Mercado, A., & Tkachuk, G. (2011). Changes in coping style and treatment outcome following motor vehicle accident. Rehabilitation Psychology, 56(1), 43–51.

Harpham, E. J. (2004). Gratitude in the history of ideas. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 19–36). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hill, P. L., & Allemand, M. (2011). Gratitude, forgivingness, and well-being in adulthood: Tests of moderation and incremental prediction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(5), 397–407.

John Tung Foundation. (2008). A survey of college students’ subjective stressors associated with depressive mood. Retrieved from http://www.jtf.org.tw/psyche/melancholia/survey.asp?This=69&Page=1.

Kaniasty, K. (2011). Predicting social psychological well-being following trauma: The role of postdisaster social support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0021412.

Karlson, C. W., Gallagher, M. W., Olson, C. A., & Hamilton, N. A. (2013). Insomnia symptoms and well-being: Longitudinal follow-up. Health Psychology, 32(3), 311–319.

Kashdan, T. B., Uswatte, G., & Julian, T. (2006). Gratitude and hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in Vietnam war veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(2), 177–199.

Kjell, O. N. E. (2011). Sustainable well-being: A potential synergy between sustainability and well-being research. Review of General Psychology, 15(3), 255–266.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lin, C. C., & Yeh, Y. C. (2011). The development of the "Inventory of Undergraduates' Gratitude". Psychological Testing, 58(S), 2–33.

Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 11–21.

Litman, J. A., & Lunsford, G. D. (2009). Frequency of use and impact of coping strategies assessed by the COPE Inventory and their relationships to post-event health and well-being. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(7), 982–991.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131.

Manne, S. L., Ostroff, J. S., Winkel, G., Fox, K., Grana, G., Miller, E., et al. (2005). Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 634–646.

Martínez-Martí, M. L., Avia, M. D., & Hernández-Lloreda, M. J. (2010). The effects of counting blessings on subjective well-being: A gratitude intervention in a Spanish sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 886–896.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 12–127.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249–266.

McCullough, M. E., & Tsang, J. (2004). Parent of the virtues? The prosocial contours of gratitude. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 123–141). New York: Oxford University Press.

McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 295–309.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2009). An attachment and behavioral systems perspective on social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 7–19.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, 56–57.

Nahum-Shani, I., Bamberger, P. A., & Bacharach, S. B. (2011). Social support and employee well-being: The conditioning effect of perceived patterns of supportive exchange. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(1), 123–139.

Nelson, C. (2009). Appreciating gratitude: Can gratitude be used as a psychological intervention to improve individual well-being? Counselling Psychology Review, 24(3–4), 38–50.

Pakenham, K. I., & Bursnall, S. (2006). Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes for children of a parent with multiple sclerosisi and comparisons with children of healthy parents. Clinical Rehabilitation, 20, 709–723.

Potter, D. (2010). Psychosocial well-being and the relationship between divorce and children’s academic achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 933–946.

Pottie, C. G., & Ingram, K. M. (2008). Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: A multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 855–864.

Roberts, R. C. (2004). The blessings of gratitude: A conceptual analysis. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 58–78). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Reviews Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Salami, O. S. (2010). Emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, psychological well-being and students attitudes: Implications for quality education. European Journal of Educational Studies, 2, 247–257.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2009). Social support: Mapping the construct. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 113–120.

Schimmack, U. (2003). Affect measurement in experience sampling research. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 79–106.

Schimmack, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2008). The influence of environment and personality on the affective and cognitive component of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 89, 41–60.

Schwarzer, R., & Knoll, N. (2007). Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. International Journal of Psychology, 42(4), 243–252.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Sheldon, K. M., & Hoon, T. H. (2007). The multiple determination of well-being: Independent effects of positive traits, needs, goals, selves, social supports, and cultural contexts. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(4), 565–592.

Shen, Y. E. (2009). Relationships between self-efficacy, social support and stress coping strategies in Chinese primary and secondary school teachers. Stress and Health, 25, 129–138.

Shiota, M. N. (2006). Silver linings and candles in the dark: Differences among positive coping strategies in predicting subjective well-being. Emotion, 6(2), 335–339.

Siewert, K., Antoniw, K., Kubiak, T., & Weber, H. (2011). The more the better? The relationship between mismatches in social support and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(4), 621–631.

Smedema, S. M., Catalano, D., & Ebener, D. J. (2010). The relationship of coping, self-worth, and subjective well-being: A structural equation model. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 53(3), 131–142.

Stupnisky, R. H., Perry, R. P., Renaud, R. D., & Hladkyj, S. (2013). Looking beyond grades: Comparing self-esteem and perceived academic control as predictors of first-year college students’ well-being. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 151–157.

Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Triandis, H. C. (1998). The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 482–493.

Suldo, S., Thalji, A., & Ferron, J. (2011). Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 17–30.

Thomas, A. C., Allen, F. L., Phillips, J., & Karantzas, G. (2011). Gaming machine addiction: The role of avoidance, accessibility and social support. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0024865.

Tsang, J.-A. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behaviour: An experimental test of gratitude. Cognition and Emotion, 20(1), 138–148.

Turashvili, T., & Japaridze, M. (2012). Psychological well-being and its relation to academic performance of students in Georgian context. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 49, 73–80.

Varni, S. E., Miller, C. T., McCuin, T., & Solomon, S. (2012). Disengagement and engagement coping with HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being of people with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31(2), 123–150.

Vitterso, J. (2001). Personality traits and subjective well-being: Emotional stability, not extraversion, is probably the important predictor. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 903–914.

Watkins, P. C. (2004). Gratitude and subjective well-being. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 167–192). New York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, Y., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(5), 431–452.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890–905.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(9), 1076–1093.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 854–871.

Wu, C.-I., Wei, P., & Song, B.-P. (2011). Relationship among social support, coping style and subjective well-being of public college and private college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 126–127.

Ye, Y., Mei, W., & Liu, Y. (2012). Effect of academic comparisons on the subjective well-being of Chinese secondary school students. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(8), 1233–1238.

Zhou, T., Wu, D., & Lin, L. (2012). On the intermediary function of coping styles: Between self-concept and subjective well being of adolescents of Han, Qiang and Yi nationalities. Psychology, 3(2), 136–142.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Council of the Republic of China in Taiwan (Contract No. NSC 100-2511-S-004-002-MY3 and NSC 101-2420-H-004-014-MY2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CC., Yeh, Yc. How Gratitude Influences Well-Being: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Soc Indic Res 118, 205–217 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0424-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0424-6