Abstract

Authors consider that subjective well-being is a theoretical construct that includes three components: life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect. Despite the numerous studies already conducted, divergences remain concerning how to conceptualize these components within a global structure of subjective well-being. This study aims to examine the dimensionality of the subjective well-being construct. A set of self-report questionnaires was used to assess life satisfaction, positive and negative affect in 397 teachers of primary and high schools. A model of a tripartite structure was tested using a confirmatory factor analysis. The results corroborate the premise that subjective well-being is a multidimensional construct that incorporates three components: life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect. Our findings reinforce the viewpoint that these three components are moderately correlated and relatively independent and also strengthen the need for a complete SWB assessment that includes adequate measures of all three components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Teachers’ well-being emerges as crucial for effective teaching. Fredrickson (2001), in the context of the “broaden and build theory”, argues that positive emotions increases several cognitive functions such creativity, attention and memory and extend action repertoires, expectations, resources, motivation and resilience in the face of adversity. Research has shown that resilient and engaged teachers influence the experiences of autonomy and competence of students, and foster their motivation (Klusmann et al. 2008). Also Day et al. (2000) suggest that motivated and enthusiastic teachers increase intrinsic motivation in students and enhance their levels of vitality.

Subjective well-being has emerged as one of the most pervasive concepts in psychological research, (Diener et al. 1999). Diener (1984) proposed that subjective well-being has three different components: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Despite the numerous studies already conducted, divergences remain concerning how to conceptualize these three components within subjective well-being global structure.

1.1 Subjective Well-Being

Veenhoven (1984) defines subjective well-being as the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of her or his life as a whole in a favorable way. The subjective element of well-being reflects the researchers’ conviction that social indicators by itselves do not characterize quality of life (Diener and Suh 1997) and that people respond differently to the same circumstances, and appraise conditions based on their distinctive expectations, values and previous experiences (Diener et al. 1999). Subjective well-being is a multidimensional construct that involves a cognitive component, related to how we evaluate our life satisfaction, and an affective component, concerning our positive or negative emotional reactions (Diener and Lucas 1999). The subjective well-being should reflect the experience of a high level of positive affect, a low level of negative affect and a high degree of satisfaction with one’s life (Deci and Ryan 2008; Diener et al. 2005).

The scientific study of this area has grown rapidly since the 60s. Research in subjective well-being arena has sought out to explore its structure and measurement, to discover its predictive variables, to compare its levels across different countries, to study its physiological mechanisms, to observe the adaptation across time to events that influence it, to evaluate its consequences to physical and mental health, and to develop strategies to promote it (Diener 1984; Diener et al. 1999; Eid and Larsen 2008; Kahneman et al. 1999).

1.1.1 Subjective Well-Being Structure

Andrews and Withey (1976, p. 18) claimed that individuals’ assessments of their lives include “both a cognitive evaluation and some degree of positive and/or negative feeling, i.e., ‘affect’”. Other researchers have also argued that subjective well-being included cognitive and affective components (Diener 1984; Diener et al. 1999). Diener (1984), in his seminal article “Subjective Well-Being”, proposed that subjective well-being has three distinct components: life satisfaction (LS), positive affect (PA), and negative affect (NA). However, the independence versus interrelationship of cognition and affect has promoted an ongoing debate (Arthaud-Day et al. 2005). Pavot and Diener (1993) believe that the affective and the cognitive components are not completely independent because both depend on evaluative appraisals, but are distinct in some degree and can offer complementary information if assessed separately. Diener et al. (2000) refer that the life satisfaction component and the affective component are moderately and sometimes highly correlated, but several studies suggest a major variability in the magnitude of these correlations (Schimmack 2008). Suh et al. (1998) pointed as a possible explanation for this the fact that the correlations between cognitive and affective components reflect the relative weight that people confer or give to the different types of information when they judge LS. In addition, other authors stated that the cognitive and affective components seem to be influenced by distinct factors and differently by the same factors (Schimmack 2006).

Some controversial questions also remain about the nature and the dimensional structure of affect. There are two established research traditions regarding the relationship between positive and negative emotions. The first tradition, the bivariate affect approach, perspectives positive and negative affect highly but not absolutely independent (Watson et al. 1988). The second tradition, the bipolar or unidimensional approach, argues that positive affect and negative affect are inversely related (Russel and Carroll 1999). Both perspectives have consistent empirical support. Several studies demonstrated orthogonality between dimensions of affect (Billings et al. 2000; Potter et al. 2000), and other studies sustain that PA and NA are inversely correlated (Russel and Carroll 1999).

In the current study, the scale adopted to assess the affective subjective well-being component emerged from the first tradition. The conceptualization underlying suggests that positive and negative affect are produced by different processes and show distinct degrees of relationship with other variables (Arthaud-Day et al. 2005). In truth, research suggests that physiological processes underlying PA and NA are different, showing close relations between brain activity, neuro-hormones and emotional reactivity (Ashby et al. 1999; Cacciopo et al. 2000; Lane et al. 1997). Also other studies support that life events influence differently PA and NA (Van Eck et al. 1996).

Currently, despite the existence of multiple studies on this topic, there isn’t to this date a consensus concerning how these three components can be conceptualized in relation to an analytic model. In the research we can distinguish four approaches: an higher-order latent SWB factor indicated by LS, PA and NA; SWB as a composite factor combining its three components; LS, PA and NA as separate constructs; and measuring just one component, but describing results in terms of subjective well-being (Busseri et al. 2007).

1.1.2 Subjective Well-Being Measurement

The great majority of work on subjective well-being has been developed using self-report questionnaires because researchers believe that no one better than the individual himself can judge his happiness level (Diener 1994). Despite some critics about the use of self-report measures, mainly concerning the existence of contextual influences, biases and responses styles (Schwarz and Strack 1999), research has established that these influences are limited (Eid and Diener 2004; Schimmack and Oishi 2005). Premature instruments typically used a single question and showed to have some degree of validity but the development of this research field has led researchers to develop multi-item scales with higher reliability and validity than single-item instruments (Diener et al. 2005). Nevertheless, subjective well-being measurement still presents some problems. Pavot (2008) refers the lack of a clear subjective well-being definition as one problematic question with implications to its measurement, since subjective well-being is conceptualized as a broad domain and sometimes researchers study it taking diverse perspectives that only converge in one of the subjective well-being components. In fact, there aren’t many instruments that assess all components of subjective well-being. The Oxford Happiness Inventory (Argyle et al. 1995) is one that measures both the subjective well-being affective and satisfaction components. Some authors stated that a comprehensive assessment of subjective well-being requires separate measures of life satisfaction and affective components of subjective well-being (Diener and Seligman 2004; Pavot 2008).

Despite there are several instruments to measure life satisfaction, Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is one of the most widely used instruments in the assessment of subjective well-being cognitive component. It was developed by Diener et al. (1985) and, in a review, Pavot and Diener (1993, p. 170) considered that “Preliminary work with SWLS reveals that life satisfaction may be a meaningful psychological construct”. The same authors, in a more recent review (Pavot and Diener 2008, p. 148), have reinforced that “SWLS has proven to be a reliable and valid measure of the life satisfaction component of SWB.” Authors of SWLS were concerned with the formulation of an instrument that assessed individuals’ global judgment of their life, with items that allowed respondents to weight domains of their lives in terms of their own values, in order to reach a global judgment of life satisfaction (Pavot and Diener 1993).

Concerning to the assessment of the two subjective well-being affective components, The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule––PANAS (Watson et al. 1988), is the most frequently instrument used to measure PA and NA.Watson et al. (1988) have conducted factor analytic studies using diverse range of affect adjectives, samples and rotation techniques in order to create independent assessments of PA and NA. These authors refer that PA reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active and alert, whereas NA is a general dimension of subjective distress and unpleasurable engagement that comprises several aversive mood states such as anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, fear and nervousness. In PANAS design, Watson et al. (1988) were concerned with selecting terms of the affective lexicon that were relative pure markers of either PA or NA. Some studies with confirmatory analysis have pointed the relative independence of PA and NA using the PANAS scales (Crawford and Henry 2004; Terracciano et al. 2003; Tuccitto et al. 2010).

1.2 Current Study

Regardless of the existence of studies that support the several approaches to subjective well-being structure, our study adopts the premise that LS, PA and NA are independent but correlated constructs that measure this theoretical concept. First, we believe that this model is the most adjusted to the one that is theoretically proposed by subjective well-being authors (Diener 1984; Diener et al. 1999). Repeatedly, these authors have emphasized that subjective well-being included three components and that researchers should assess all of them. Second, several research has supported this idea. Lucas et al. (1996) concluded that the three components measured different construct of well-being. Additionally, others studies show that subjective well-being components correlate distinctly with the same variables (Albuquerque et al. in press; Diener and Lucas 1999; Lucas et al. 1996). Second, there is an increasing importance of this construct in Portuguese literature and in the extensive applications of this instruments and it will be useful at this point to have more accurate results of its validity.

Despite Galinha and Pais-Ribeiro (2008) have also tested subjective well-being structure in a Portuguese sample, these authors used an incomplete version of PANAS scale items: four items to PA and four items to NA. Also the cognitive component of subjective well-being was assessed by one single indicator, which revealed less psychometric qualities that multi item scales (Diener 2000; Diener et al. 2005), and through the satisfaction with life domains measure. So they tested a four component structure instead of the tripartite one explored in other studies:

Thus, the present study aims at examining the subjective well-being construct validity of the Portuguese versions of SWLS and PANAS, using structural equation modeling, specifically confirmatory factor analysis in a teachers’ sample. Our hypothesis is that subjective well-being model structure, that conceives LS, PA and NA as three independent components moderately correlated, will be confirmed in a Portuguese sample of teachers.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Three hundred and ninety seven teachers participated in this study, recruited from primary and high schools in Viseu district (Portugal) and selected randomly by clusters corresponding to the schools they worked in. Mean age was 41.09 (SD = 7.71), 72.1% were females (n = 287) and 27.9% males (n = 111). The mean of years in teaching experience was 16.85 (SD = 8.00). Sociodemographic characteristics of this teachers’ sample were analysed in comparison to the characteristics of the Portuguese teachers’ population (Gabinete de Estatística e Planeamento da Educação 2010). We found that our sample had similar sociodemographic characteristics.

We contacted schools’ boards and obtained permission for the data collection. With the collaboration of school staff, the author gave participants a battery of self-report questionnaires related to personality, well-being and socio-demographic and professional data, as well as script information about the research goals and filling instructions. In line with ethical requirements, it was emphasized that participants cooperation was voluntary and their answers were confidential and only used for the purpose of the study.

2.2 Measures

Subjective well-being was assessed by the Portuguese versions of SWLS (Diener et al. 1985) and PANAS (Watson et al. 1988).

The Portuguese SWLS version used in the present study was validated to the Portuguese population by Simões (1992) and the answers are measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the translation and adaptation study Simões (1992) found a Cronbach’s alpha of .77 and one single factor emerged, accounting for 53% of the variance of the scale.

The first validation of PANAS for the Portuguese population achieved by Simões (1993) was used in this study. This version comprises 22 adjectival affect descriptors (11 to evaluate PA and 11 to evaluate NA), rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not of all) to 5 (extremely). The addiction of two more descriptors to the original Watson, Clark and Tellegen (1988) version aimed at improving internal consistency, since a few original descriptors were problematic in their content when translated. Cronbach’s alpha was .82 for PA and .85 for NA, and convergent and divergent validity was confirmed.

3 Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for all items that compose the three dimensions of the SWB construct. In this sample, positive affect (PA) has higher means than negative affect (NA).

If we compare these means with others found in another Portuguese teachers’ sample using the same measures (Albuquerque 2006), the current SWLS items’ means are similar to the previous, despite the mean values for PA items and NA items are in some cases slightly higher.

We conducted a confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) to SWB measure considering the Portuguese version of SWLS (Simões 1992) and PANAS (Simões 1993) and the assumption that SWLS, PA and NA are three independent and correlated factors. This first order factor analysis considers the subjective well-being as a theoretical construct not metrically attainable. On the calculus we used a categorical robust weighted least square estimator (WLSMV) developed by Muthén and Muthén (2001), that consider the observed variables that compose a continuous latent variable are ordinal, as it happens when we use Likert scales such as this one.

When we first calculated the model with the 27 items of the two instruments (SWLS and PANAS), the indicators for global adjustment were a little lower than the acceptable level. Examining the indicators for local adjustment was possible to identify four items (PANAS 8, 10, 13 and 21) that had low values of R 2 (.098–.183), which indicates few variance explained by the proposed model (Kline 2005). Because of this, we removed these items one by one, until we had a model composed by three latent variables (SWLS, PA and NA), that we hypothesized to have 5 items in the first factor, 9 in the second and 9 in the last one. This option was based on the assumption of improving the adjustment and validity of the model and these 4 items were not considered essential for the measure of PA and NA. So it would be better for the instrument not to have this many items.

We calculated the model once again and the model fit was evaluated based on five goodness of fit indices, which are indicators provided by the software with the chosen estimator, and the ones suggested by Brown (2006) for better assessment of overall model fit. The overview of these indices allowed us to consider the present model to have an acceptable global model fit [c 2(81) = 316.663; p < .001/TLI = .95/CFI = .90/RMSEA = .08/SRMR = .07]. The CFI and RMSEA are above the cut point recommended (>.90 and <.08, respectably), and TLI and SRMR (>.95 and <.08, respectably) are a little bit better that the cut point suggested by Brown (2006).

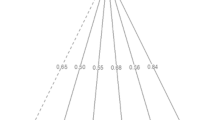

Also, regarding local adjustment, we observed (Fig. 1; Table 2) that all standardized indicators have theoretical and statistical support and so, we considered this a plausible model for explaining the factorial structure of subjective well-being construct.

The loading values presented on Table 2 support the adequacy of the model and our option of excluding 4 items, since we can see that all items have values of R 2 above .250, and all 23 items on the model have R 2 ranging from .252 till .854. The corrected item-total correlations showed adequate values that confirm the adequacy of these items to the construction of each measure and their internal consistency.

Cronbach’s alpha values (SWLS: .84; PA: .79; NA: .86) allow us to assume, good to very good levels of internal consistency for the three factors of the subjective well being scale.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the structure underlying the three components of subjective well-being using a confirmatory factor analysis. Our hypothesis that subjective well-being model structure integrates LS, PA and NA as three independent components was confirmed.

This study identified a three independent but moderately correlated factor model for the explanation of subjective well-being. The three subjective well-being components emerge at an identical level with moderated correlations between them. All items that integrate the final model are strongly loaded on the appropriate factor and the reliability values of the scale or subscales, provided by the final model, are very adequate.

Our analysis provides empirical support for the relative independence of cognitive and affective subjective well-being components that was found in other studies (Lucas et al. 1996) and also corroborated a moderate correlation between cognitive and affective components (Arthaud-Day et al. 2005; Diener et al. 1995, 2000; McCullough et al. 2000). As Pavot and Diener (1993) suggest, the affective and the cognitive components aren’t completely independent since both depend on evaluative appraisals, nevertheless they are distinct in some degree and can offer complementary information if assessed separately.

Concerning the relationship between subjective well-being affective dimensions, our findings support that PA and NA are separable components, weakly and inversely correlated. Authors of PANAS point out that PA and NA are highly but not completely independent. However, the correlation coefficients found in the current study were higher than those found by the authors of the scale, (from r = −12 to r = −.20) (Watson et al. 1988). As we said above, two perspectives coexist in the affect arena with empirical support: the bivariate affect approach and the unidimensional approach. Our findings show that PA and NA aren’t completely independent but are only moderately and inversely correlated. Perhaps, PA and NA may coexist, in some degree, independently, and the levels of one don’t influence the levels of the other. However, when a type of affect reaches high levels that may lead a decreasing in the levels of the other.

One of the problems in subjective well-being measurement is that several researchers, despite measuring only one of its components, describe the results in terms of subjective well-being (Busseri et al. 2007). Furthermore, Pavot (2008) pointed as one of the problems in subjective well-being assessment the fact that its evaluation is too narrow or incomplete. These results highlight that cognitive and affective measures aren’t equivalent, thus it is important to use both components to avoid biases.

Regarding PANAS, there are two positive items, ‘proud’ and ‘moved’, and also two negative items, ‘hostile’ and ‘ashamed’, that show problems in validity, with low R 2 values or too high residual variance. The issue with the positive items may be related to the semantic characteristics of the adjectives in Portuguese language. ‘Proud’ (‘orgulhoso’ in Portuguese) has either a positive or negative affective connotation depending on the context, so it’s a very subjective affective adjectival. Also ‘moved’ (‘emocionado’ in Portuguese), which is a positive adjective added to the scale by the author of the Portuguese validation, is not a pure marker of positive affect in the Portuguese language, since it can be used to characterize positive or negative emotional states. The two items, ‘hostile’ (hostil in Portuguese) and ‘ashamed’ (envergonhado in Portuguese.), seem clear markers of negative affect, nevertheless they aren’t correlated satisfactorily with the rest of the set of negative affect items. The idea of PA and NA independence underlying the theoretical construct of PANAS requires a particular and difficult care in the selection of items in an attempt to obtain a scale that measures independent constructs (Crawford and Henry 2004). The authors of PANAS refer that their items are relative pure markers of PA and NA. The translation of items into Portuguese language can also modify their strength as pure markers of PA or NA, weakening their correlations with others items of the respective subscale.

Our findings extend the work on subjective well-being structure and corroborate the threefold structure that suggested some degree of empirical independence between LS, PA and NA. In addition, these results reveal that the Portuguese versions of SWLS (Simões 1992) and PANAS (Simões 1993) are meaningful measures of subjective well-being in teachers, if two positive and two negative items of PANAS are removed, for not fitting the model. Future research using this version of PANAS should bear in mind this issue.

5 Limitations and Future Research

One methodological limitation of this study concerns the specificity of the population studied composed only by teachers. Since the overrepresentation of certain groups limits the generalization to other populations (Brewer 2000), additional studies should be developed using larger, heterogeneous and representative samples.

Although the tested model has been supported by statistical indicators it is also true that it is in the limit of adequacy for its acceptability. The CFI, and RMSEA are in the cut point referred in the literature for considering the model acceptable, but we also know that the studies for this cut point have, in a great majority, maximum likelihood (ML) as estimator (Brown 2006). So, it is possible to consider that this is a very good explanation of the construct and that future studies should try to strengthen the results including other samples.

6 Conclusion

This study corroborates the premise that subjective well-being is a multidimensional construct that incorporates three components: life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect. These findings reinforce the viewpoint that these three components are moderately correlated and relatively independent and also strengthen the necessity of a complete SWB assessment that includes adequate measures of all three components. The findings contribute to reinforce the tripartite structure of subjective well-being at a cross-cultural level.

References

Albuquerque, I. (2006). O florescimento dos professores: Projectos pessoais, bem-estar subjectivo e satisfação profissional. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra.

Albuquerque, I., Lima, M. P., Matos, M., & Figueiredo, C. (in press). Neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness and subjective well-being: What hides behind global analyses? Social Indicators Research.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: Americans’ perceptions of quality of life. New York: Plenum Press.

Argyle, M., Martin, M., & Lu, L. (1995). Testing for stress and happiness: The role of social cognitive factors. In C. D. Spielberg & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Stress and emotion (Vol. 15, pp. 173–187). Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis.

Arthaud-Day, M. L., Rode, J. C., Mooney, C. H., & Near, J. P. (2005). The subjective well-being construct: A test of its convergent, discriminate, and factorial validity. Social Indicators Research, 74, 445–476.

Ashby, F. G., Isen, A. M., & Turken, A. U. (1999). A neurological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychological Review, 106, 529–550.

Billings, D. W., Folkman, S., Acree, M., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Coping and physical health during caregiving: The roles of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 131–142.

Brewer, M. B. (2000). Research design and issues of validity. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 3–16). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, T. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press.

Busseri, M. A., Sadava, S. W., & Decourville, N. (2007). A hybrid model for research on subjective well-being: Examining common-and component specific sources of variance in life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Social Indicators Research, 83, 413–445.

Cacciopo, J. T., Berntson, G. G., Larsen, J. T., Poehlmann, K. M., & Ito, T. A. (2000). The psychophysiology of emotion. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 173–191). New York: Guilford Press.

Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 245–265.

Day, C., Fried, R. L., Patrick, B. C., Hisley, J., Kempler, T., & College, G. (2000). “What’s everybody so excited about?”: The effects of teacher enthusiasm on student intrinsic motivation and vitality. Journal of Experimental Education, 68, 217–236.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 1–11.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E. (1994). Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Social Indicators Research, 31, 103–157.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 213–229). New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2005). Subjective well-being: The Science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 63–73). New York: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Scollon, C. K., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Suh, E. M. (2000). Positivity and the construction of life satisfaction judgments: Global happiness is not the sum of its parts. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 159–176.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 130–141.

Diener, E., & Suh, M. E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40, 189–216.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Tree decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2004). Global judgments of subjective well-being: Situational variability and long-term stability. Social Indicators Research, 65, 245–277.

Eid, M., & Larsen, R. J. (Eds.). (2008). The Science of Subjective Well-Being. London: The Guilford Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

Gabinete de Estatística e Planeamento da Educação (2010). Perfil do Docente 2008/09. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estatística e Planeamento da Educação.

Galinha, I. C., & Pais-Ribeiro, J. L. (2008). The structure and stability of subjective well-being: A structure equation modelling analysis. Applied Research Quality Life, 3, 293–314.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwartz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kline, R. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (2th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of self-regulatory patterns. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 702–715.

Lane, R. D., Reiman, E. M., Ahern, G. L., & Schwartz, G. E. (1997). Neuroanatomical correlates of pleasant and unpleasant emotion. Neuropsychologia, 35, 1437–1444.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 616–628.

McCullough, G., Huebner, E. S., & Laughlin, J. E. (2000). Life events, self-concept and adolescents’ positive subjective well-being. Psychology in Schools, 37, 281–290.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2001). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Pavot, W. (2008). The assessment of subjective well-being. Success and shortfalls. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 124–141). London: The Guilford Press.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction with Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152.

Potter, P., Zautra, A., & Reich, J. (2000). Stressful events and information processing dispositions moderate the relationship between positive and negative affect: Implications for pain patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 22, 191–198.

Russel, J. A., & Carroll, J. M. (1999). On bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 3–30.

Schimmack, U. (2006). The structure of subjective well-being: Personality, affect, life satisfaction, and domain satisfaction. Unpublished manuscript.

Schimmack, U. (2008). The structure of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 97–123). London: The Guilford Press.

Schimmack, U., & Oishi, S. (2005). The influence of chronically and temporarily accessible information on life satisfaction judgements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 395–406.

Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1999). Reports of subjective well-being: Judgmental process and their methodological implications. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 61–84). New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Simões, A. (1992). Ulterior validação de uma escala de satisfação com a vida (SWLS). Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, XXVI(3), 503–515.

Simões, A. (1993). São os homens mais agressivos que as mulheres? Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, XXVII, 387–404.

Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Triandis, H. C. (1998). The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 482–493.

Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Costa, Jr., & Paul, T. (2003). Factorial and construct validity of the Italian Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19, 131–141.

Tuccitto, D. E., Giacobbi, P. R., Jr., & Leite, W. L. (2010). The internal structure of positive and negative affect. A confirmatory factor analysis of the PANAS. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70, 125–141.

Van Eck, M., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., & Sulon, J. (1996). The effects of stress, traits, mood states and stressful daily events on salivary cortisol levels. Biological Psychology, 43, 69–84.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: The Riedel Publishing Company.

Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1107.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albuquerque, I., de Lima, M.P., Figueiredo, C. et al. Subjective Well-Being Structure: Confirmatory Factor Analysis in a Teachers’ Portuguese Sample. Soc Indic Res 105, 569–580 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9789-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9789-6