Abstract

The transition to parenthood is a watershed moment for most parents, introducing the possibility of intra-individual and interpersonal growth or decline. Given the increasing number of dual-earner couples in the United States, new parents’ attitudes towards employment (as well as the ways in which they balance employment and personal demands) may have an impact on their overall well-being. Based on anecdotal accounts, guilt about the conflict between employment and family (termed work-family guilt) appears particularly pervasive among U.S. mothers of young children; specifically, mothers, but not fathers, express high levels of a subtype of work-family guilt, that pertains to the negative impact their work has on their families (termed work-interfering-with-family guilt). However, little research within psychology has explicitly examined this phenomenon, and to our knowledge, no quantitative study has investigated gender differences in work-family guilt among U.S. parents of young children. In a cross-sectional, correlational study involving 255 parents of toddlers from the greater Southern California area, we coded parents’ narrative responses to a series of open-ended questions regarding employment and family for the presence of work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt (in the form of guilt about the negative impact of employment on children). Mothers had significantly higher work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt relative to fathers. We discuss our findings in terms of theory on gender roles, as well as the questions they generate for future areas of investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

[Work] does impact my family because I don’t spend enough time doing things for them. I feel distracted by work a lot of the time, which makes me feel guilty about spending less time with my kids. I feel like I can’t win by working.

– Participant Mother

The transition to parenthood has been described as a transformative experience—one that has garnered significant interest from social scientists for nearly 50 years (Nelson et al. 2014; Rossi 1968). This transition may be one of the most dramatic experiences in adulthood, requiring reorganization across multiple domains of identity (Cowan and Cowan 2000). Further, becoming a parent is associated with higher risk for negative personal outcomes, particularly among women. For instance, in transitioning to parenthood, mothers face elevated risk for psychiatric distress (Dietz et al. 2007; Jones et al. 2014; Ross and McLean 2006), which in part may be related to hormone changes and sleep deprivation (Gay et al. 2004; Hendrick et al. 1998; Parfitt and Ayers 2014) but can also be attributed to psychological stress (Cutrona 1984; Don et al. 2014). In addition, new mothers fare poorly as compared to new fathers according to other indicators, such as life satisfaction (Nelson et al. 2015).

This transition to parenthood may be more complicated among parents who also work outside the home, perhaps particularly for mothers who are employed. When they first become parents, employed adults may find that their working and home lives both change dramatically, with practical and emotional consequences. Increasingly, in two-parent families, both members of the couple must work in order to sustain a stable living (Hayghe 1990). Yet, in keeping with traditional gender roles (Eagly et al. 2000), new working mothers still carry primary responsibility for childrearing and may face greater demands on their time and energy than new working fathers (Bianchi et al. 2006; Ozer 1995; Sasaki et al. 2010). Further, the pressure for mothers to have large quantities of face time with their children is at its apex (Milkie et al. 2015). As a result, working mothers are likely to experience more conflict between their responsibilities as parents and workers, which in turn might result in feelings of guilt.

Although mothers’ and fathers’ perspectives on working inside and outside the home have been discussed through the use of qualitative data in sociology (Hochschild and Machung 1989), less psychological research has examined these issues (Korabik 2015). Further, work-family guilt emerges as a salient theme in qualitative studies (e.g., Aycan and Eskin 2000, working with a Turkish sample), but has received limited quantitative attention. Whereas qualitative studies are poised to provide significant depth regarding social issues, quantitative data have the potential to speak to the extent to which phenomena are widespread and consistent across large numbers of people (Strauss and Corbin 1998). In the present paper, we provide a quantitative examination of gender differences in work-family guilt among a U.S. sample of parents of young children. By using narrative data collected in response to a series of open-ended questions about employment and family, we are able to analyze the extent to which parents spontaneously acknowledge feelings of guilt when describing their employment and family experiences. An advantage of this approach is that it captures the thoughts and feelings that organically arise when parents reflect on their experiences; however, by rating the narratives on scales assessing the extent to which guilt is present, we render the data amenable to quantitative analyses, enabling us to speak to statistically significant differences in the prevalence of these themes.

It is important to investigate factors associated with work-family guilt because guilt may have important intra- and inter-personal consequences. On the intrapersonal front, greater work-family guilt, like greater general guilt, may be associated with more general distress, such as depression (Ghatavi et al. 2002) and anxiety (Shapiro and Stewart 2011). Further, guilt may result in behavior that can be detrimental in the long-term, such as quitting paid employment altogether or taking on too much household responsibility when work-family guilt is high (Hochschild and Machung 1989; Martínez et al. 2011). Interpersonally, work-family guilt may have consequences for the child: Parents riddled with work-family guilt may engage in more repair behaviors, such as permissive parenting, more commonly found in dual-earner families, which in turn can be detrimental for children (Martínez et al. 2011; Nomaguchi and Milkie 2004).

Grounded primarily in research on gender beliefs and work-family, we test the hypothesis that mothers will demonstrate greater guilt about working and parenting (referred to as work-family guilt) than fathers. Further, we predict that mothers will display greater guilt about work-interfering-with-family, a subtype of work-family guilt, than fathers. We recruited our sample from the United States, and therefore we rely most heavily on studies conducted with U.S. samples; however, given the paucity of quantitative studies on this topic, we use studies examining gender differences in work-family from other cultural contexts to inform our hypotheses.

Gender Beliefs

Gender beliefs, that is, cultural beliefs or schemas that inform how people enact gender in their day-to-day lives (Ridgeway and Correll 2004), figure prominently in our theoretical model of the origins of gender differences in work-family guilt. Gender beliefs are ubiquitous in modern U.S. culture (Lueptow et al. 2001; Spence and Buckner 2000) and contribute to gender-role norms, such as expectations that men be primarily agentic (i.e., independent and assertive) and women be primarily communal (i.e., warm and nurturing; Eagly et al. 2000). In turn, these expectations inform important aspects of men’s and women’s lives. Notably, because caring for children requires nurturance and emotional responsiveness (i.e., communal tasks), women are commonly expected to be the primary caregiver (Eagly et al. 2000).

Violations of gender-normed behavior then become salient, and oftentimes criticized, behavior (Okimoto and Brescoll 2010; Rudman and Phelan 2008), which can result in internal and external consequences. On the internal front, violating a gender-prescribed norm can result in perceived feelings of inadequacy, leading to guilt, which in turn can lead to negative outcomes, such as anxiety (Duxbury and Higgins 1991; Good and Sanchez 2010; Guerrero-Witt and Wood 2010). In terms of external consequences, gender-norm violation may result in backlash from others (i.e., social and economic penalties for violating gender stereotypes, such as criticism from colleagues and hiring discrimination; Okimoto and Brescoll 2010; Rudman 1998; Rudman et al. 2012).

Societal perceptions of employed mothers’ failure to fulfill primary caregiving duties could translate into global negative perceptions of working women, extending to their workplace abilities. Indeed, working mothers are considered less competent in the workplace than professional women without children (Cuddy et al. 2004), whereas fathers who return to full-time employment after the birth of a child are viewed as more professionally competent (Etaugh and Folger 1998). These perceptions portend important outcomes for working mothers: Compared to fathers, as well as to men and women without children, working mothers are held to higher standards for hiring, and they are less likely to be promoted (Fuegen et al. 2004). Moreover, working mothers are viewed as less dedicated to their families than non-working mothers (Etaugh and Nekolny 1990), a comment echoed by anecdotal accounts (Covert 2014). Thus, working mothers may face considerable judgment and criticism regarding their commitment to their children and the quality of their caregiving. As a result of gender beliefs—specifically, those about employment and family—the experiences, and resulting emotions, of men and women as they combine employment and family are likely different.

Over time, experiencing backlash may result in the additional internalization of gender norms and increased negative sequelae. For instance, whereas an employed mother may initially experience some discomfort due to her awareness of the gender-norm violation she is committing (working for pay instead of taking care of her young child), critical comments from colleagues may both further reinforce her belief that a norm violation has occurred and also intensify her negative emotional reaction regarding her behavior (Moss‐Racusin and Rudman 2010; Rudman and Fairchild 2004). In sum, negative emotions, such as guilt, can arise directly from internalization of gender norms, or indirectly, via the experience of backlash, as well as through both channels.

Work-Family Conflict

In line with Korabik (2015), we posit that negative emotional reactions such as work-family guilt arise in reaction to conflicts emerging from the interaction of employment and family in parents’ lives. At the broadest level, work-family interaction involves the process by which the experiences in family roles influence experiences in work roles, and vice versa (Eby et al. 2010). Conflict occurs when the two roles are incompatible with one another, resulting in an inability to meet the demands at work or at home (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). By definition, conflict can flow in either direction—demands at home (e.g., a sick child) could interfere with the ability to complete tasks at work (i.e., family-interfering-with-work conflict) and/or demands at work (e.g., late meetings) could interfere with the ability to fulfill family commitments (i.e., work-interfering-with-family conflict; Frone et al. 1997). A study conducted in Turkey suggested that although reports of family-interfering-with-work conflict were not statistically distinct by gender, women reported greater work-interfering-with-family conflict than men (Aycan and Eskin 2005). Moreover, across multiple cultural contexts, both types of work-family conflict are associated with experiencing more negative emotions, such as anxiety, tension, worry, frustration, guilt, and distress among men and women (Frone et al. 1997; Geurts et al. 2003; Livingston and Judge 2008; Shaw and Burns 1993), as well as lower job and life satisfaction (Ernst Kossek and Ozeki 1998).

Given traditional gender-role expectations that mothers’ primary responsibility should involve caring for children, work-interfering-with-family conflicts may create more distress for working mothers. On the other hand, because working mothers may be held to higher standards in the workplace (Fuegen et al. 2004), working mothers may also struggle with family-interfering-with-work conflicts. For instance, imagine the scenario in which a young child experiences a high fever on the same day as an important meeting at his parent’s work; in this circumstance, a parent must make the difficult choice to leave the child with another caregiver or miss the important meeting at work to care for the child. In this situation, a mother may experience negative emotions about either solution to this problem: Leaving the child at home with an alternate caregiver may cause guilt as a result of her failure to fulfill caregiving duties, yet missing work to stay home may make her worried about the consequences of shirking employment-related responsibilities and potentially guilty for doing so. On the other hand, if a father is in the same position, he may experience relatively less guilt regarding going to work because fulfilling his occupational duties is a central part of his parental, gender-prescribed role as primary breadwinner.

Thus, although both fathers and mothers may experience some conflict about the competing demands of their work and home lives, and prioritizing family above work may also create distress among mothers, mothers may experience more personal distress than fathers when prioritizing work-related demands at the expense of home-related demands due to the fact that this action violates a traditional gender norm for mothers (Milkie and Peltola 1999; Nomaguchi et al. 2005). This assertion is in part supported by the results of a recent study examining anxiety among new mothers. The researchers found that anxiety is higher among new mothers whose roles and gender attitudes are conflicting, such as mothers who work and hold traditional beliefs about the division of childcare responsibilities, than among new mothers whose roles and gender attitudes are concordant (Mickelson et al. 2013). The findings provide initial empirical evidence that gender-role conflict is related to increased negative emotion (anxiety) among new mothers relative to new fathers. In the current investigation, we posit that the emotional consequences of work-family conflict extend beyond conflict, stress, and anxiety to the unique experience of work-family guilt, particularly among mothers.

Work-Family Guilt

Guilt is a self-evaluative emotion that arises when people feel they have violated a societal or moral standard and deserve reproach for their wrongdoing (Jones and Kugler 1993; Klass 1987; Tangney 2003). Theorists argue that guilt is an interpersonal emotion, typically occurring within the context of a close personal relationship (Baumeister et al. 1994) and that it consists of cognitive (i.e., the recognition of harm), affective (i.e., unpleasant feelings), and motivational components (i.e., desire to reverse the harm that one has caused; Hoffman 1982). Further, an individual’s feelings of guilt may be independent of the existence of any actual physical, psychological, or emotional harm (Harder et al. 1992; O’Connor et al. 1999).

Importantly, guilt can be measured indirectly through its presence in behavioral samples (indexing others’ perceptions of the presence of guilt; e.g., Kochanska et al. 2002) or directly through self-reports (indexing one’s own perception of guilt; e.g., Fayard et al. 2012), with each measure yielding unique, yet complementary information. Narrative responses, a type of behavioral measure, can reveal differences in psychological states that may exist outside one’s conscious awareness (Jacobvitz et al. 2002). Although self-report measures capture a relevant piece of information concerning an individual’s own felt experience of internal states, they are limited by the fact that people are not always able to accurately appraise these states (Jacobvitz et al. 2002). In the current study, we test a narrative measure of work-family guilt, enabling us to reduce respondent biases.

Recently, Korabik (2015) applied terminology used in the work-family conflict literature to differentiate among different sub-types of work-family guilt. Specifically, Korabik argued that work-family guilt can arise when employment interferes with family or family interferes with employment (Glavin et al. 2011; Hochwarter et al. 2007; Livingston and Judge 2008; Korabik 2015). For instance, work-interfering-with-family guilt can arise when a work meeting is scheduled to run into the evening hours, preventing a parent from putting his/her children to bed; family-interfering-with-work guilt can arise when staying up late at night with a sleepless child causes a parent to miss his/her early morning work meeting. Few studies have explicitly differentiated between the two sub-types of work-family guilt (Korabik 2015). In our research, we distinguish between (a) work-family guilt (the overarching term that encompasses guilt emerging from conflicts between work and family, going in either direction) and (b) guilt specifically related to work impairing one’s ability to attend to child- and family-related issues (work-interfering-with-family guilt)—a subtype of work-family guilt, which we reason may be particularly prevalent among mothers as compared to fathers (Staines 1980). Work-interfering-with-family guilt likely takes many forms, including guilt about the negative impact of work on aspects of the child’s life, on the romantic partnership, and on the living space or domestic tasks. In the current study, we focus specifically on work-interfering-with-family guilt as it pertains to the impact of employment on the child because this aspect may have the clearest implications for parenting.

Only a handful of quantitative studies have explored gender differences in work-family guilt (Korabik 2015), and we were unable to find any quantitative examinations of gender differences in work-family guilt in U.S. samples. In a sample of employed parents from Turkey, mothers reported significantly higher levels of “employment-related guilt” than fathers; also, work-family conflict was associated with higher levels of guilt among both mothers and fathers (Aycan and Eskin 2005). Another study conducted with working mothers and fathers in Spain, in which the authors measured guilt arising from several different aspects of parenting (e.g., delegating parenting tasks to others), did not reveal gender differences (Martínez et al. 2011). Notably, these studies were conducted in different cultures and used different conceptualizations of work-family guilt, making it difficult to determine the source of these discrepant findings. For example, the latter study could have failed to establish gender differences in guilt due to differences in cultural norms or because the broad conceptualization of guilt washed away gender differences in the different subtypes of work-family guilt. For instance, mothers may experience greater guilt when considering the impact they might have on their children, whereas fathers experience greater guilt when they feel their family is impacting their work performance. Finally, both studies measured guilt via self-reports, which are susceptible to significant respondent biases. Investigations examining sub-types of work-family guilt among parents of young children using measures that reduce respondent biases are needed.

Evidence from related research literatures supports our hypothesis that working mothers may experience more guilt than working fathers. For instance, Benetti-McQuoid and Bursik (2005) conducted a study with undergraduates at an urban university on the East Coast of the United States finding that self-reported proneness to general guilt in response to hypothetical scenarios is greater among women than among men, and it is greater among both women and men with traditionally feminine gender roles than women and men with traditionally masculine gender roles. Moreover, within a sample of U.S. students and employees, Livingston and Judge (2008) found that work-interfering-with-family conflict is associated with greater self-reported general guilt among people with an egalitarian gender-role orientation, which may be more common among working mothers. Of note is that in their study, 75 % of the participants did not have children under the age of 10, underscoring the need for research on work-family guilt among parents of young children. Based on the findings we described, we expect that working mothers experience more work-family guilt than working fathers. However, based on the specific type of gender-role conflict that working mothers are most likely to encounter (Eagly et al. 2000; Etaugh and Nekolny 1990), we suspect that gender differences in work-interfering-with-family guilt are particularly salient.

Current Investigation

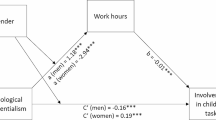

Using a novel assessment tool, we closely examined the experiences of general work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt among working parents of young children. We operationalized work-family guilt as the result of work-family conflict, with components of negative cognition and emotion, as well as motivation to reduce harm (Hoffman 1982). We explored whether, as compared to fathers, mothers have greater work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt. We coded working parents’ open-ended narratives about work and family for the expression of (a) work-family guilt and (b) work-interfering-with-family guilt, operationalized specifically as the extent to which the parent perceives his/her work as having a negative impact on his/her child. Parents reported on their general guilt, which was used as a covariate to enable us to examine whether gender differences in work-family guilt exist beyond previously-documented differences in general guilt (Benetti-McQuoid and Bursik 2005). Based on theorizing regarding the consequences of gender-norm violation (e.g., Okimoto and Brescoll 2010), we anticipated that working mothers would experience more coder-rated work-family guilt (Hypothesis 1) and coder-rated work-interfering-with-family guilt (Hypothesis 2) than working fathers.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A U.S. community sample of full-time working parents of children ages 1–3 years-old completed our online survey (N = 255, with 140 mothers). Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 48 years-old (M mothers = 32.89, SD mothers = 5.09; M fathers = 32.26, SD fathers = 4.79). Most participants (81 % of mothers, 82 % of fathers) were married, European-American (81 % mothers, 79 % fathers), and had Bachelor’s degrees (76 % mothers, 77 % fathers). Most participants were employed more than 40 h per week (M mothers = 44.81, SD mothers = 7.72; M fathers = 45.63, SD fathers = 5.81); hours worked per week ranged from 36 to 81 (rangemothers = 36–81; rangefathers = 36–66). Further, most participants reported an annual household income of greater than $61,000 (62.1 % mothers, 56.5 % fathers), with annual household income ranging from less than $40,000 to greater than $100,000 (for both mothers and fathers).

Participants responded to an advertisement for a study of the emotional experiences of parents of children between the ages of 1–3 years-old. Recruitment occurred via social media websites, regional parenting websites, and email listservs for parents working at institutions and corporations, as well as via flyers posted in businesses and in public spaces in a large U.S. Southern California city and surrounding metro area. Participants responded in writing to open-ended questions about their experiences about their employment, completed a self-report measure of general guilt, and then provided additional information about their employment and demographics.

Measures

General Guilt

Participants completed the 6-item guilt subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson and Clark 1994) to assess their current feelings of guilt. Participants rated the extent to which they had experienced each emotion (guilty, blameworthy, dissatisfied with self, angry with self, and disgusted with self) over the last few weeks on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). This subscale has been widely used as a measure of guilt (e.g., Fayard et al. 2012; Leahey et al. 2007) and has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .86), test-retest reliability over an average period of 2 months (α = .68), and convergent and discriminant validity (Watson and Clark 1994). In our sample, reliability was sound (full sample: α = .89; mothers: α = .89; fathers: α = .91).

Coders’ Ratings of Guilt

We developed the Pomona Work and Family Assessment (PWFA; Borelli et al. 2014) by reading theoretical papers and opinion articles on work-family guilt and by conducting focus groups with employed parents to identify the types of emotional responses parents have regarding work-family conflicts. The PWFA consists of four open-ended prompts to which participants are asked to respond while considering all aspects of their employment experiences: “How does your employment impact your family?” (Prompt 1); “How does your employment impact your child or children?” (Prompt 2); “How does your employment impact your romantic partner?” (Prompt 3); and “How does your employment impact you personally?” (Prompt 4).

Participants’ responses across the four prompts were coded on two dimensions. Four coders (unaware of all participant identifying and demographic information, including gender) coded for the presence of work-family guilt when the participant expressed the thought or feeling that there was something that he/she should do differently with respect to the intersection of their employment and family lives along with indications that the participant felt at fault for negative impacts in work and family domains that arose as a result of working and parenting (see Table 1). Coders coded for work-interfering-with-family guilt when the participant seemed to feel at fault for negative impacts on children that arose as a result of working for pay (see Table 2). The four coders were trained to reliability on a set of 36 narratives that we created for training purposes (i.e., not part of the study sample). After achieving inter-rater reliability on the training narratives, all four coders coded all of the study narratives. We assessed inter-rater reliability using Spearman rank order correlations (Gaderman et al. 2012), which capture the ordinal nature of the data, to compute Cronbach’s alphas for work-family guilt (α = .88) and for work-interfering-with-family guilt (α = .89). Given that one coder was a study author, we conducted reliability sensitivity analyses excluding this coder and achieved similar levels of inter-rater reliability using the remaining coders (αs = .82; .84, respectively). We computed mean scores of all four coders’ ratings, which were used in the subsequent analyses; our findings remained significant when the author-coder was excluded.

Given that the present study is the first to use the PWFA, we conducted analyses involving additional variables to establish the validity of the scales. Scores on the work-family guilt scale were positively associated with theoretically-related constructs: self-reported negative emotion, r = .26, p = . 001 (PANAS-X); general guilt on two different self-report measures, r = .31, p = . 001 (PANAS-X guilt scale), and r = .26, p = . 001 (Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale; Cohen et al. 2011); attachment anxiety, r = .22, p = . 001, and avoidance, r = .18, p = .01 (Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Scale; Fraley et al. 2000); and both depressive, r = .37, p = . 001 (Patient Health Questionnaire; Kroenke and Spitzer 2002), and anxiety symptoms, r = .29, p = . 001 (General Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; Spitzer et al. 2006). By contrast, scores on work-family guilt were not associated with theoretically distinct constructs, such as job engagement, r = .01, p = .86 (May et al. 2004), participants’ age, r = .02, p = . 70, or participants’ education, r = −.06, p = .33. Patterns of associations for the work-interfering-with-family guilt scale were similar: The same associations that were statistically significant for work-family guilt were significant for work-interfering-with-family guilt. Findings provide preliminary support that the PWFA measures the intended construct given that PWFA scores are significantly associated with theoretically-related but not unrelated constructs.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

None of the demographic factors examined in our study (participant age, income, educational attainment, race, or hours worked per week) were significantly associated with work-family or work-interfering-with-family guilt, so we did not include them as covariates in analyses. However, among mothers, PANAS guilt was positively associated with work-family guilt, r = .35, p = 001, and work-interfering-with-family guilt, r = .32, p = 001; no significant associations between general guilt and coder-rated guilt emerged for fathers. For both mothers, r = .69, p = 0001, and fathers, r = .70, p = 001, work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt were positively associated. Prior to testing hypotheses and using linear regressions, we examined whether any of these demographic factors were moderators of the association between parent gender and work-family guilt. None of these factors significantly moderated these associations.

Examination of the coded data revealed that work-family guilt was positively skewed; therefore, we conducted a logarithmic transformation, which restored the data to within normal parameters. Work-interfering-with-family guilt was normally distributed. Independent t-tests revealed that, as compared to fathers (M = 2.16, SD = 1.05), mothers (M = 2.46, SD = 1.09) were rated as describing their work experiences with significantly more guilt, t(254) = 2.23, p = .05, ηp 2 = .06. As compared to fathers (M = 1.83, SD = 0.80), mothers (M = 2.33, SD = 1.15) were rated as describing their work having significantly greater negative impact on their children (work-interfering-with-family guilt), t(254) = 3.88, p = .001, ηp 2 = .02. Mean PANAS-X guilt scores, which were roughly comparable to prior studies of college students (Fayard et al. 2012; Leahey et al. 2007), were used as a covariate to ensure that findings reflect gender differences in work-family guilt rather than gender differences in general guilt. As an extra precaution for our ordinal dependent variables, we also conducted Mann Whitney U tests on these data; gender differences on both scales remained statistically significant. Zero-order correlations revealed that general guilt and work-family guilt were positively associated among mothers only and that work-family and work-interfering-with-family guilt were positively associated for both genders.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1 predicted that mothers would have higher coder-rated work-family guilt than fathers. A univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) indicated that after controlling for PANAS guilt, F(1, 254) = 22.15, p = .001, ηp 2 = 0.08, mothers (M = 2.32, SD = 1.16) demonstrated higher work-family guilt than fathers (M = 1.83, SD = 1.04), F(1, 254) = 15.29, p = .001, ηp 2 = 0.06. The findings remained significant when PANAS guilt was not included in the model, thus supporting our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that as compared to fathers, mothers would be characterized as expressing higher work-interfering-with-family guilt. After controlling for PANAS guilt, F(1, 254) = 12.53, p = .001, ηp 2 = 0.05, mothers (M = 2.46, SD = 1.09) demonstrated higher work-interfering-with-family guilt than fathers (M = 2.16, SD = 1.05) in the ANCOVA, F(1, 254) = 4.76, p = .03, ηp 2 = 0.02. These findings were also significant when PANAS guilt was not included in the model, thus confirming our second hypothesis.

Discussion

The notion that mothers experience more work-family guilt than fathers is almost a truism, grounded in both qualitative cross-cultural research (Aycan and Eskin 2000) and voices from the blogosphere (e.g., Lilley 2011). However, we are not aware of a single quantitative study that had previously examined gender differences in work-family guilt in the United States, making it difficult to ascertain the generalizability of qualitative findings. We found that when asking open-ended questions about their work, mothers’ narratives conveyed stronger feelings of guilt (as perceived by masked coders) pertaining to work-family conflict, and specifically, to its impact on their children, than did those of fathers. Moreover, the gender differences persisted above and beyond general guilt, suggesting that greater work-family guilt among mothers was not simply reducible to women’s overall higher propensity for guilt. However, it is worth noting that in our sample, general guilt was not higher among mothers as compared to fathers, which is a departure from what Benetti-McQuoid and Bursik (2005) found, although their study involved a different population than ours (undergraduate students versus parents of young children, respectively).

Our findings add to a growing body of literature documenting associations between work-family conflict and negative emotion. For instance, studies conducted in the United States and the Netherlands suggest that work-family conflict is associated with greater negative emotion (Frone et al. 1997; Geurts et al. 2003; Livingston and Judge 2008). Further, the gender differences we observed are consistent with prior findings that new mothers (with mismatched gender roles and work-status) experience greater anxiety than new fathers (Mickelson et al. 2013). It is important to note that much of the prior research on work-family conflict has been conducted with parents of older children (Livingston and Judge 2008). Mothers of toddlers may experience heightened work-family conflict, and thus work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt, as compared to mothers of older children, because the gender beliefs regarding mothering are even stronger when children are young. Our work contributes to this literature by suggesting that work-family conflict elicits more guilt among mothers as compared to fathers of toddlers.

Further, our findings resonate in part with the results of a study conducted among parents of children under 6 years-old in Turkey: Aycan and Eskin (2005) found that mothers reported greater work-interfering-with-family conflict than fathers, although not greater family-interfering-with-work conflict. We did not directly assess work-family conflict, but we did find that mothers had greater work-family guilt than fathers. Work-family guilt may be one of several emotional responses that emerge from work-family conflict; therefore these studies cannot be precisely equated, although it is interesting to note the differences in our findings regarding work-interfering-with-family constructs. Our findings also diverge from Martínez et al. (2011) study of parents of children between 3 and 6 years-old residing in Spain; these researchers did not find gender differences in self-reported work-family guilt arising from situations that could broadly be defined as work-interfering-with family conflict. At this point, it is not possible to ascertain whether the differences in the findings across these three studies are best accounted for by cultural differences (United States, Turkey, Spain), the different constructs measured (work-family guilt, work-family conflict), variations in measurement (coded narrative data, self-report data), or discrepancies in children’s ages, but the differences undoubtedly raise interesting questions that can be pursued in future investigations.

In future studies, it would be interesting to examine whether gender differences in work-family guilt precede or even explain gender differences in anxiety, as has been proposed but not tested (Duxbury and Higgins 1991). Further, it would be important to examine whether men who violate gender norms of not being employed (e.g., stay-at-home or unemployed fathers) feel greater guilt about their non-working behavior than do non-working mothers. If the theoretical formulation informing our research is true, we would expect to find reverse patterns of work-family guilt in this situation (such that fathers have greater guilt than mothers).

In our study, we distinguished between work-family guilt, an overarching term that encompasses guilt about all conflicts occurring between work and family, and work-interfering-with-family guilt, the subtype of work-family guilt that arises when employment impedes one’s ability to tend to family-related responsibilities. Due to our interest in factors that might affect parenting, we focused explicitly on the guilt experienced as a result of feeling that one’s work has a negative impact on the child. Traditional gender roles involve a central focus on caregiving, and this creates a gender role conflict for working mothers (Eagly et al. 2000); in response, working mothers may experience negative emotions (Mickelson et al. 2013), such as guilt. As such, we thought it important to make a distinction between general work-family guilt and the subtype of this guilt that involves concern about harm to the child or the family. However, our data revealed that work-family guilt and work-interfering-with-family guilt were highly positively correlated; further, the gender effects in work-interfering-with-family guilt were smaller in size than the gender effect in general work-family guilt. These findings suggest that mothers have guilt related to myriad aspects of work-family conflict, raising additional questions. For instance, do mothers also feel guiltier than fathers about family-related responsibilities interfering with work? Moreover, our findings prompt questions about the temporal precedence and/or causal pattern between different aspects of work-family guilt: Do mothers’ feelings of guilt begin in one domain (i.e., work-interfering-with-family guilt) and then spread to work-family guilt more generally? Our preliminary findings open up numerous research questions regarding fine-grained distinctions among subtypes of work-family guilt.

Limitations and Future Directions

Future studies could build upon our research in several ways. First, our research design was correlational and cross-sectional, limiting our ability to draw temporal or causal inferences. We can speculate as to the causes of the gender differences here, but ultimately we are unable to use these data to speak to them. Evidence suggests that exposing individuals to a negative stereotype about their in-group is associated with maladaptive outcomes, in part because the activation of the negative stereotype results in stereotype threat—the fear of confirming the negative stereotype (Spencer et al. 1999; Steele and Aronson 1995). In future studies, a similar paradigm could be implemented (e.g., exposing participants to traditional or non-traditional stereotypes of the roles of mothers versus fathers) to demonstrate the hypothesized link between social factors and elevated work-family guilt among mothers.

Second, our recruitment method is a potential limitation of our current research. In our study we stated that, in order to participate, adults must have a child between the ages of 1 and 3 years-old and work full-time. Participants’ awareness that we were recruiting parents who worked full-time may have given them insight into the purpose of the study, potentially biasing our results. In addition, although assumptions about gender roles figure prominently in our theoretical conceptualization of this research (Eagly et al. 2000), we did not directly assess gender roles in our study, limiting our ability to identify mechanisms of the observed gender differences in work-family guilt. Measuring gender roles can help refine our understanding of these findings by identifying moderators of the gender differences: Do men with egalitarian gender roles also experience work-family guilt? Do working mothers who subscribe to traditional gender roles have higher guilt than those who subscribe to non-traditional gender roles, as has been shown in the case of anxiety (Mickelson et al. 2013)? Is work-family guilt likely to increase or decrease as egalitarian gender roles become more widespread? Do those with non-Western gender roles exhibit guilt patterns that are similar to our U.S.-based sample? In future studies it will be essential to identify factors that modify and explain our findings and to determine whether these effects vary across cultures.

Finally, all of the participants included in these studies worked full-time, and most were Caucasian, living above the poverty line, and married or in a long-term committed relationship, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future work could examine whether lower-income mothers, mothers who work part-time, or single mothers experience greater work-family guilt than their male counterparts. Although our own data did not reveal interactions between participants’ gender and their marital status or income, our sample composition may have been underpowered to detect such differences. Feeling autonomous in the decision to work may be better represented among married and high-socioeconomic status mothers. Accordingly, these women may have more control over their work schedules, permitting them to balance work and family, and possibly feel less guilt (cf. Hochwarter et al. 2007). Consistent with the finding that role strain is greater among women low in resources (Hobfoll 2001; Shipley and Coats 1992), lower-income mothers who are employed full-time may experience higher work-interfering-with-family guilt as a result of having to spend time away from their children and yet still struggling to provide for them. Accordingly, our study may underestimate U.S. gender differences in work-family guilt. Further, our samples were recruited from the United States, and notions about childrearing and parenting vary cross-culturally (Hays 1996), which could influence the extent to which our findings generalize. In future work it will be important to examine gender differences in work-family guilt in other cultures. The answers to these questions would inform social psychological theories about gender differences in work-family guilt.

To our knowledge, the study presented here is among the first quantitative assessments of gender differences in work-family guilt among U.S. parents, despite the long history of examining these topics qualitatively within the field of sociology. Hence, our study complements existing sociological research in providing converging quantitative evidence of these gender differences, which enhances confidence in the generalizability of the phenomenon. In addition, our research is timely given that the landscape of research regarding employment experiences among parents of young children is rapidly evolving (Boris 2014). Given that the transition to parenthood introduces opportunities for growth as well as declines in both the interpersonal and personal mental health domains (Nelson et al. 2014), understanding the factors that place new parents at risk for maladjustment is crucial. Successful adjustment to becoming a parent involves not only bringing a child into one’s home, but also learning to integrate the new role as parent with other life roles.

Practice Implications

Understanding the nuances of how parents of young children feel about their roles has important implications for parents’, couples’, and children’s psychological well-being. With respect to parents themselves, the transition to parenthood represents a risky period for mothers (Don et al. 2014), and efforts to understand risk among new parents who work ought to incorporate an assessment of how they feel about their work-family life. Identifying factors that confer risk for heightened work-family guilt, such as parent gender, is an important endeavor because guilt is theoretically and empirically linked with myriad intrapersonal and interpersonal negative outcomes. Work-family guilt can impact one’s general well-being, for example, by increasing risk for depression or anxiety (Ghatavi et al. 2002), and may influence one’s behavior in a way that could have negative downstream occupational consequences (Martínez et al. 2011). For instance, it is conceivable that work-family guilt could impair occupational performance, as has been demonstrated in the case of anxiety (Beadel et al. 2013). Moreover, it may impact one’s parenting behavior, resulting in permissive behavior (Martínez et al. 2011). Further, work-family guilt may be detected by children, inadvertently conveying negative messages about the meaning of parents’ employment, which in turn could influence children’s behavior.

The manifestation of work-family guilt in different contexts and across time is an important area for future inquiry. For instance, it would be interesting to understand when work-family guilt is highest among parents of both genders. In the present study, we studied parents of 1 to 3 year-olds due to our desire to tap an age range beyond typical parental leaves and yet before traditional preschool entrance. It also would be illuminating to examine how parents’ work-family guilt changes as a function of children’s birth order, as well as to examine other moderators of the association between parents’ gender and work-family guilt.

If work-family guilt is higher among mothers but not fathers, as our study suggests, and if subsequent experimental research supports the notion that exposure to traditional parent gender-role stereotypes evokes feelings of guilt among mothers, an important next step would be to identify ways of redefining gender roles. Promising research in other areas of social psychology suggests that norms are modifiable (Knudson-Martin 2011; Rosenthal and Crisp 2006) and that small, well-chosen interventions targeting stereotypes can cause significant behavior change (Walton and Cohen 2011). Redefining gender roles becomes a public mental health issue when viewed from the standpoint of mothers’ emotional well-being, so efforts to develop, test, and implement methods of redefining “good mothering” are crucial.

Conclusion

Our study provides preliminary evidence of gender differences in work-family guilt among U.S. parents of young children. The transition to parenthood represents a period of unique risk and opportunity in terms of both relational and psychiatric health (Don et al. 2014; Parfitt and Ayers 2014), and understanding how people fare psychologically when they become parents is crucial to supporting young families. If coming to the workplace is fraught with guilty feelings for mothers more than for fathers, mothers may be more likely to demonstrate negative occupational outcomes, providing an impetus to reduce gender differences in work-family guilt.

References

Aycan, Z., & Eskin, M. (2000, July). A cultural perspective to work-family conflict in dual-career families with preschool children: The case of Turkey. Paper presented at the Meeting of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, Pultusk, Poland.

Aycan, Z., & Eskin, M. (2005). Relative contributions of childcare, spousal support, and organizational support in reducing work-family conflict for men and women: the case of Turkey. Sex Roles, 53, 453–471.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 243–267.

Beadel, J. R., Green, J. S., Hosseinbor, S., & Teachman, B. A. (2013). Influence of age, thought content, and anxiety on suppression of intrusive thoughts. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 598–607.

Benetti-McQuoid, J., & Bursik, K. (2005). Individual differences in experiences of and responses to guilt and shame: examining the lenses of gender and gender role. Sex Roles, 53, 133–142.

Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Borelli, J. L., Nelson, S. K., and River, L. R. (2014). Pomona work and family assessment. Unpublished document. Pomona College, Claremont, CA.

Boris, E. (2014). Mothers, household managers, and productive workers: The international labor organization and women in development. Global Social Policy, 14, 189–208.

Cohen, T. R., Wolf, S. T., Panter, A. T., & Insko, C. A. (2011). Introducing the GASP scale: A new measure of guilt and shame proneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 947–966.

Covert, B. (2014, June 23). No, working moms are not ruining their children. Think Progress. Retrieved from http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2014/06/23/3451313/working-mothers- children/.

Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2000). When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2004). When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 701–718.

Cutrona, C. E. (1984). Social support and stress in the transition to parenthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 378–390.

Dietz, P. M., Williams, S. B., Callaghan, W. M., Bachman, D. J., Whitlock, E. P., & Hornbrook, M. C. (2007). Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 1515–1520.

Don, B. P., Chong, A., Biehle, S. N., Gordon, A., & Mickelson, K. D. (2014). Anxiety across the transition to parenthood: Change trajectories among low-risk parents. Anxiety, Stress and Coping: An International Journal, 27, 633–649.

Duxbury, L. E., & Higgins, C. A. (1991). Gender differences in work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 60–74.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes & H. M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 123–174). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Eby, L. T., Maher, C. P., & Butts, M. M. (2010). The intersection of work and family life: The role of affect. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 599–622.

Ernst Kossek, E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 139–149.

Etaugh, C., & Folger, D. (1998). Perceptions of parents whose work and parenting behaviors deviate from role expectations. Sex Roles, 39, 215–223.

Etaugh, C., & Nekolny, K. (1990). Effects of employment status and marital status on perceptions of mothers. Sex Roles, 23, 273–280.

Fayard, J. V., Roberts, B. W., Robins, R. W., & Watson, D. (2012). Uncovering the affective core of conscientiousness: The role of self-conscious emotions. Journal of Personality, 80, 1–32.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365.

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 145–167.

Fuegen, K., Biernat, M., Haines, E., & Deaux, K. (2004). Mothers and fathers in the workplace: How gender and parental status influence judgments of job-related competence. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 737–754.

Gaderman, A. M., Guhn, M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2012). Estimating ordinal reliability for likert-type and ordinal item response data: A conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 17, 1–13. Retrieved from http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=17&n=3.

Gay, C. L., Lee, K. A., & Lee, S. Y. (2004). Sleep patterns and fatigue in new mothers and fathers. Biological Research for Nursing, 5, 311–318.

Geurts, S. A. E., Kompier, M. A. J., Roxburgh, S., & Houtman, I. L. D. (2003). Does work-home interference mediate the relationship between workload and well-being? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 532–559.

Ghatavi, K., Nicolson, R., MacDonald, C., Osher, S., & Levitt, A. (2002). Defining guilt in depression: a comparison of subjects with major depression, chronic medical illness and healthy controls. Journal of Affective Disorders, 68, 307–315.

Glavin, P., Schieman, S., & Reid, S. (2011). Boundary-spanning work demands and their consequences for guilt and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 43–57.

Good, J. J., & Sanchez, D. T. (2010). Doing gender for different reasons: Why gender norm conformity positively and negatively predicts self-esteem. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 203–214.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88.

Guerrero-Witt, M., & Wood, W. (2010). Self-regulation of gendered behavior in everyday life. Sex Roles, 62, 635–646.

Harder, D. W., Cutler, L., & Rockart, L. (1992). Assessment of shame and guilt and their relationships to psychopathology. Journal of Personality Assessment, 59, 584–604.

Hayghe, H. (1990). Family members in the work force. Monthly Labor Review, 113(3), 14–19.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hendrick, V., Altshuler, L. L., & Suri, R. (1998). Hormonal changes in the postpartum and implications for postpartum depression. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry, 39, 93–101.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. International Review of Applied Psychology, 50, 337–370.

Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York, NY: Viking.

Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewe, P. L., Meurs, J. A., & Kacmar, C. (2007). The interactive effect of work-induced guilt and ability to manage resources on job and life satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 125–135.

Hoffman, M. L. (1982). Development of prosocial motivation: Empathy and guilt. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The development of prosocial behavior (pp. 281–313). New York, NY: Academic.

Jacobvitz, D., Curran, M., & Moller, N. (2002). Measurement of adult attachment: the place of self-report and interview methodologies. Attachment & Human Development, 4, 207–215.

Jones, I., Chandra, P. S., Dazzan, P., & Howard, L. M. (2014). Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1789–1799.

Jones, W. H., & Kugler, K. (1993). Interpersonal outcomes of the guilt inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 246–258.

Klass, E. T. (1987). Situational approach to assessment of guilt: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 9, 35–48.

Knudson-Martin, C. (2011). Changing gender norms in families and society: Toward equality amidst complexities and contradictions. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes (4th ed., pp. 324–346). New York, NY: Guilford.

Kochanska, G., Gross, J. N., Lin, M.-H., & Nichols, K. E. (2002). Guilt in young children: Development, determinants, and relations with a broader system of standards. Child Development, 73, 461–482.

Korabik, K. (2015). The intersection of gender and work-family guilt. In M. J. Mills (Ed.), Gender and the work-family experience (pp. 141–157). Switzerland: Springer International.

Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32, 509–515.

Leahey, T. M., Crowther, J. H., & Mickelson, K. D. (2007). The frequency, nature, and effects of naturally occurring appearance-focused social comparisons. Behavior Therapy, 38, 132–143.

Lilley, C. (2011, August 31). The ballad of a working mom: Guilt, anxiety, exhaustion and guilt. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/blogs/babyproject/2011/08/30/140068781/the-ballad-of-a-working-mom-guilt-anxiety-exhaustion-and-guilt.

Livingston, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Emotional responses to work-family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 207–216.

Lueptow, L. B., Garovich-Szabo, L., & Lueptow, M. B. (2001). Social change and the persistence of sex typing: 1974–1997. Social Forces, 80(1), 1–36.

Martínez, P., Carrasco, M. J., Aza, G., Blanco, A., & Espinar, I. (2011). Family gender role and guilt in spanish dual-earner families. Sex Roles, 65, 813–826.

May, R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 11–37.

Mickelson, K. D., Chong, A., & Don, B. (2013). To thine own self be true: Impact of gender role and attitude mismatch on new mothers’ mental health. In J. Marich (Ed.), Psychology of women: Diverse perspectives from the modern world (pp. 1–16). Hauppauge, NY: Nova.

Milkie, M. A., Nomaguchi, K. M., & Denny, K. E. (2015). Does the amount of time mothers spend with children or adolescents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 355–372.

Milkie, M. A., & Peltola, P. (1999). Playing all the roles: Gender and the work-family balancing act. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 476–490.

Moss‐Racusin, C. A., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). Disruptions in women’s self‐promotion: The backlash avoidance model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 186–202.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychological Bulletin, 140, 846–895.

Nelson, S. K., Layous, K., Cole, S. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2015). Are fathers (but not mothers) happier than their childless peers? Gender moderates the association between parenthood, psychological need satisfaction, and stress. Manuscript under review.

Nomaguchi, K. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2004). Costs and rewards of children: the effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 65, 356–374.

Nomaguchi, K. M., Milkie, M. A., & Bianchi, S. M. (2005). Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? Journal of Family Issues, 26, 756–792.

O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., & Weiss, J. (1999). Interpersonal guilt, shame, and psychological problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 18, 181–203.

Okimoto, T. G., & Brescoll, V. L. (2010). The price of power: Power seeking and backlash against female politicians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 923–936.

Ozer, E. M. (1995). The impact of childcare responsibility and self-efficacy on the psychological health of professional working mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 315–335.

Parfitt, Y., & Ayers, S. (2014). Transition to parenthood and mental health in first-time parents. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35, 263–273.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender and Society, 18, 510–531.

Rosenthal, H. E., & Crisp, R. J. (2006). Reducing stereotype threat by blurring intergroup boundaries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 501–511.

Ross, L. E., & McLean, L. M. (2006). Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 1285–1298.

Rossi, A. S. (1968). Transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 30, 26–39.

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 629–645.

Rudman, L. A., & Fairchild, K. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 157–176.

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Nauts, S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 165–179.

Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2008). Backlash effects for counterstereotypical behavior in organizations. In A. Brief & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 28, pp. 61–79). New York, NY: Elsevier.

Sasaki, T., Hazen, N. L., & Swann, W. J. (2010). The supermom trap: Do involved dads erode moms’ self-competence? Personal Relationships, 17, 71–79.

Shapiro, L. J., & Stewart, S. E. (2011). Pathological guilt: A persistent yet overlooked treatment factor in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 23, 63–70.

Shaw, E., & Burns, A. (1993). Guilt and the working parent. Australian Journal of Marriage and Family, 14, 30–43.

Shipley, P., & Coats, M. (1992). A community study of dual-role stress and coping in working mothers. Work and Stress, 6, 49–63.

Spence, J. T., & Buckner, C. E. (2000). Instrumental and expressive traits, trait stereotypes, and sexist attitudes: What do they signify? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 44–62.

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4–28.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Tangney, J. P. (2003). Self-relevant emotions. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 384–400). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form. Unpublished manuscript, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

No external funding was used to support this project. Internal grants from Pomona College (including the Hahn Teaching with Technology grant) funded the work. Prior to data collection, we obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board at Pomona College. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borelli, J.L., Nelson, S.K., River, L.M. et al. Gender Differences in Work-Family Guilt in Parents of Young Children. Sex Roles 76, 356–368 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0579-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0579-0