Abstract

We present a bibliometric comparison of publication performance in 226 scientific disciplines in the Web of Science (WoS) for six post-communist EU member states relative to six EU-15 countries of a comparable size. We compare not only overall country-level publication counts, but also high quality publication output where publication quality is inferred from the journal Article Influence Scores. As of 2010–2014, post-communist countries are still lagging far behind their EU counterparts, with the exception of a few scientific disciplines mainly in Slovenia. Moreover, research in post-communist countries tends to focus relatively more on quantity rather than quality. The relative publication performance of post-communist countries in the WoS is strongest in natural sciences and engineering. Future research is needed to reveal the underlying causes of these performance differences, which may include funding and productivity gaps, the historical legacy of the communist ideology, and Web of Science coverage differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

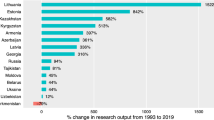

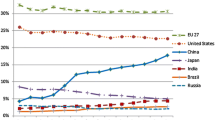

Following the end of Communist rule in Eastern Europe, several of the post-communist countries enjoyed rapid convergence towards their Western European counterparts in many areas including steady increases in income per capita, reductions in the prevalence of coronary heart disease, or improvements in environmental quality.Footnote 1 However, the rate of convergence in scientific research performance appears to have been much slower. In 2015 only about 3% of the European Research Council’s (ERC) Starting Grants originated from the EU’s new Eastern members. This is an important gap to understand given the significance of research and innovation for long-term economic growth and the European Structural Fund’s heavy focus on R&D activities. Unfortunately, the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) are missing from most systematic international comparisons of scientific publication and citation performance (surveyed in the next section).

Our goal is thus to provide the first up-to-date cross-country comparison of publication performance for post-communist EU member states, which we contrast with a set of similarly sized EU-15 (developed) economies.Footnote 2 In line with the existing literature, we provide field-specific comparisons. In order to assess the nature of the scientific catch-up process in these countries, we focus on two separate cross-country comparisons, one looking at overall publication performance and a second based primarily on high quality research. We thus compare not only the total scientific publication performance per capita but also the number of articles published in the most influential journals. The next section positions our analysis in the scientometric literature. The added value of our study is that it provides an up-to-date descriptive look at an important but neglected geographical area. Our analysis is based on the Web of Science (WoS) data such that our varying coverage of scientific disciplines corresponds to the limitations of the WoS.

Brief literature review

Ideally, cross-country comparisons of scientific performance are based on measuring both the discipline-specific publication performance and the discipline-normalized citation impact of such performance. Depending on the purpose of the comparison, one may also attempt to control for cross-country differences in R&D funding levels, again preferably by field.

The literature has progressed towards this ideal starting with May (1997) who presents a comparison of national scientific publication performance based on simple counts of papers and citations without standardization for discipline-specific attributes, country size or R&D funding levels. King (2004) distinguishes seven broad fields of research and normalizes the country-level publication counts by country population or GDP. The dearth of information on discipline-specific R&D funding across countries limits researchers’ ability to account for parts of performance gaps that are due to funding differences.Footnote 3 Similarly, there are no widely accepted measures of ‘natural’ publishing intensity (the number of articles expected to be published per year) by field of science (Abramo and D’Angelo 2014a).

There has been much more progress in accounting for discipline-specific citation patterns.Footnote 4 It is now well established that simple citation counts provide a misleading country-level aggregate (as illustrated in, e.g., Abramo et al. 2008) due to countries’ different structures of scientific disciplines. As a result, almost all recent cross-country or time comparisons have been based on time- and discipline-normalized citation impacts.Footnote 5

The most relevant example of this practice for our analysis is offered by Kozak et al. (2015). They contrast publication counts and normalized citation impacts from 1981 to 2011 for six post-communist EU-member states and four formerly soviet republics. They do so for three broad groups of scientific disciplines and report relatively little improvement in the publication and citation performance of these countries after the breakdown of communism.Footnote 6 In contrast to their work, our analysis offers a view of the post-communist countries’ more recent publication performance in detailed WoS disciplines (categories). Our approach thus enables us to ask whether there are at least some specific disciplines in which the post-communist countries do well in comparison to their developed EU counterparts. Unlike Kozak et al. (2015) we cover the social sciences and agricultural sciences. More importantly, we also directly contrast the quantity vsersu quality choices made by researchers in the post-communist EU countries to those made in the EU-15 countries.

In terms of practical application, the widely used CWTS and Scimago online rankings of universities and institutions (but not of countries) are based on three complementary statistics: the total number of articles published, the average field-normalized citations per article, and the total number of highly cited articles.Footnote 7 Our approach is similar in that we contrast countries’ scientific outputs (by field) using both total publication counts and selected high-quality publication counts. We abstain from analyzing citation impacts given our focus on very recent publications, which we detail in the next section.

Methodology

Our country and discipline-level analysis compares total publication performance, i.e., the number of Articles published during 2010–2014 in journals registered by the Web of Science (WoS). An article is credited to a country if at least one of its authors is affiliated with an institution that has an address in that country. In the case of co-authored articles, each article is credited to all countries that appear among the authors’ affiliations. We differentiate between 226 academic disciplines based on the WoS Categories used to classify journals. If a journal belongs to several WoS Categories, we credit the articles published in that journal to all of the relevant WoS Categories.

We adjust country-level publication performance only for country population size (i.e., we measure publications per capita). Hence, our population-adjusted publication performance indicators for each discipline reflect compounded differences in aggregate country-level R&D expenditures, in the field structure of funding by country, and in research productivity. Disentangling the specific contributions of these factors is an important area for future research.

To shed light on potential differences in the quality structure of the total publication performance, we additionally contrast countries in terms of their publication output in influential scientific journals. We thus infer publication quality from information on the placement of articles. Similarly to Smith et al. (2014) we rely on the discipline-specific percentile of journal ranking according to its citation impact. Unlike Smith et al. (2014), who used the simple Impact Factor (as defined by Thomson Reuters), we identify the most important journals as those with an Article Influence Score (AIS) in the top quarter within their particular WoS Category.Footnote 8 Where a journal is assigned to multiple WoS Categories we use its average percentile rank across WoS Categories. This is a simple approach that would not be justifiable for a comparison of individual researchers or research teams and it has a number of drawbacks even at the country level. The leading alternative is to rely on field-normalized citation indicators. A prototype of such a measure is the country-specific average relative citation index (RCI).Footnote 9 When used to assess countries at a widely different level of scientific development, however, this index is driven in large part by the lower tail of the citation distribution profile. For two countries with an identical number of highly cited articles, the index depends on the extent of less cited publications.Footnote 10 Further, as the index does not differentiate citations by their importance (i.e., their source), it may be affected by localized (within-country) citation patterns. This may affect the measurement of scientific performance in post-communist countries, whose research communities were isolated from the outside world for decades and who may thus be susceptible to within-country instrumental citation practices. We thus believe that in our case, the per capita country-specific number of highly cited articles (reflecting the field and time of publication), based on the notion that a journal’s AIS is by construction correlated with the average impact of its articles, provides a suitable indicator of publication quality. Furthermore, we are interested in the most recent publication performance, meaning that its citation impact is yet to be accumulated. Future work should ideally complement our simple up-to-date comparisons with a sophisticated field-normalized citation index that enables citations’ countries of origin to be distinguished.

The main goal of this paper is to offer a meaningful comparison between the research output recorded by relatively developed and successful post-communist EU economies and that of their EU-15 counterparts. Hence, we start with the set of four Visegrad countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). To this set, we add Slovenia—the richest new EU member state with a history of communism—and Croatia, so that the analysis covers both of the post-Yugoslav economies that are now in the EU. These six post-communist EU countries are relatively comparable in terms of development and size.

To make a balanced comparison, we next compile data from six of the EU-15 countries. Since the six post-communist countries we focus on are mostly small or medium-sized countries where English is not the native language, our selection of comparable developed EU countries aims to include countries that share both of these features. Country size may be related to research output through the existence of a viable set of local publication outlets (e.g., a large-enough internal research market in Germany, not in Slovenia or Slovakia). Researchers from non-English-speaking countries may face language barriers to international publishing, thanks to English being the academic lingua franca, which researchers from English-speaking countries do not. Therefore we have chosen Austria, Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden for our comparison. We have intentionally avoided English-speaking Ireland and the UK as well as large EU-15 countries such as Germany or France. We believe that this set of six successful post-communist and six mid-sized EU-15 countries is reasonably balanced and enables us to draw meaningful conclusions.

Results

In this section, we present charts comparing each country’s per capita total publication performance (the number of articles published in journals between 2010 and 2014 normalized by the country’s populationFootnote 11) and each country’s high quality publication performance. Each country’s performance in both dimensions is compared to the average performance of all other (11) countries.Footnote 12 Each chart in Fig. 1 provides the overall picture for one country. The plotted elements represent WoS Categories. To facilitate the comparisons, we group the 226 WoS Categories into five broad research areas (Natural Sciences, Engineering and Technology, Medical and Health Sciences, Agricultural Sciences, and Social Sciences) according to the OECD classification and distinguish these areas using different colors.

Number of articles published per capita (overall vs. high quality) in 2010–2014, relative to average number in other countries. Each point represents one discipline (WoS Category). The distance of a given WoS Category from the dashed horizontal and vertical lines measures a country’s percentage deviation in that discipline from the average per capita publication performance of all (11) other countries. The horizontal axis captures total article counts (publication performance ‘quantity’) while the vertical axis captures article counts corresponding to journals that appear in the top quartile of their WoS Category according to the journal Article Influence Score (publication performance ‘quality’)

For each country, the distance of a given scientific discipline from the horizontal and vertical dashed lines measures that country’s percentage point difference from the other countries’ average publication performance in that WoS discipline. The horizontal axis captures total publication performance (quantity) while the vertical axis captures publication performance in high-AIS journals (quality). Points located to the right of the vertical dashed line thus represent WoS Categories in which the country in question outperforms the average of the other eleven countries in terms of quantity, and points located above the horizontal dashed line indicate that the country in question outperforms the other eleven on average in terms of quality. The axes are identically scaled, so that the quantity and quality results on each chart, and the country-specific charts themselves can be easily compared.Footnote 13

The graphs in the first row of Fig. 1 correspond to the Visegrad countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). Their relative publication performance is low both overall and in high quality publications. Recall that the comparison benchmark for these Visegrad countries includes not only the six EU-15 countries, but also the other (five) post-communist CEE countries. There is a pattern of publication quantity at the expense of quality, especially in Poland and Slovakia. Note that from among the Visegrad countries, only the Czech Republic shows a handful of fields that reach above the horizontal mean benchmark of quality. This contrasts with highly developed countries such as the Netherlands or Sweden, which exhibit quality performance well above 100% (i.e., at more than twice the average level) in a large number of disciplines. Slovenia differs from the other countries of the former Eastern bloc, as it performs somewhere between the “West” and “East” and is notably above the average in numerous disciplines. In Fig. 1, Slovenia resembles Portugal, the EU-15 country whose level of per capita GDP in PPP is similar to that of Slovenia or the Czech Republic. In contrast, the performance of Croatia, the other post-Yugoslav country in our sample, is more reminiscent of the Visegrad countries.Footnote 14

The Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Finland show more proportional patterns between the quantity and quality of their publication performance. On the other hand, Belgium, Portugal and Slovenia have rather dispersed patterns—some disciplines are focused on quality (disciplines above the 45-degree line), others on quantity (disciplines below the 45-degree line). Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 show the same data as Fig. 1 separately for each broad scientific area to provide a more detailed insight.

Agricultural Sciences: Number of articles published per capita (overall vs. high quality) in 2010–2014, relative to average number in other countries. Each point represents one discipline (WoS Category). The distance of a given WoS Category from the dashed horizontal and vertical lines measures a country’s percentage deviation in that discipline from the average per capita publication performance of all (11) other countries. The horizontal axis captures total article counts (publication performance ‘quantity’) while the vertical axis captures article counts corresponding to journals that appear in the top quartile of their WoS Category according to the journal Article Influence Score (publication performance ‘quality’)

Engineering and Technology: Number of articles published per capita (overall vs. high quality) in 2010–2014, relative to average number in other countries. Each point represents one discipline (WoS Category). The distance of a given WoS Category from the dashed horizontal and vertical lines measures a country’s percentage deviation in that discipline from the average per capita publication performance of all (11) other countries. The horizontal axis captures total article counts (publication performance ‘quantity’) while the vertical axis captures article counts corresponding to journals that appear in the top quartile of their WoS Category according to the journal Article Influence Score (publication performance ‘quality’)

Medical and Health Sciences: Number of articles published per capita (overall vs. high quality) in 2010–2014, relative to average number in other countries. Each point represents one discipline (WoS Category). The distance of a given WoS Category from the dashed horizontal and vertical lines measures a country’s percentage deviation in that discipline from the average per capita publication performance of all (11) other countries. The horizontal axis captures total article counts (publication performance ‘quantity’) while the vertical axis captures article counts corresponding to journals that appear in the top quartile of their WoS Category according to the journal Article Influence Score (publication performance ‘quality’)

Natural Sciences: Number of articles published per capita (overall vs. high quality) in 2010–2014, relative to average number in other countries. Each point represents one discipline (WoS Category). The distance of a given WoS Category from the dashed horizontal and vertical lines measures a country’s percentage deviation in that discipline from the average per capita publication performance of all (11) other countries. The horizontal axis captures total article counts (publication performance ‘quantity’) while the vertical axis captures article counts corresponding to journals that appear in the top quartile of their WoS Category according to the journal Article Influence Score (publication performance ‘quality’)

Social Sciences: Number of articles published per capita (overall vs. high quality) in 2010–2014, relative to average number in other countries. Each point represents one discipline (WoS Category). The distance of a given WoS Category from the dashed horizontal and vertical lines measures a country’s percentage deviation in that discipline from the average per capita publication performance of all (11) other countries. The horizontal axis captures total article counts (publication performance ‘quantity’) while the vertical axis captures article counts corresponding to journals that appear in the top quartile of their WoS Category according to the journal Article Influence Score (publication performance ‘quality’)

Next, we quantify these graphical comparisons at the country level. Table 1 summarizes what proportion of WoS Categories in a given research area is located in the upper-right quadrant of each panel, i.e., above average both overall and in terms of high quality publications.

Compared to the other EU-15 countries in our analysis, Sweden, the Netherlands and Finland score particularly strongly using this composite measure while there are a noticeably smaller number of WoS disciplines in which Austria and especially Portugal have above average publication counts. However, no EU-15 country performs as poorly as Slovakia or Poland, where not a single scientific discipline scores above the average for the other countries. Hungary and Croatia also come very close to this minimum performance. On the other hand, Slovenia does better than Portugal using this particular metric in all broad fields of science.

Excluding Slovenia, the post-communist countries do particularly poorly in Social Sciences and in Agricultural Sciences, where they do not produce a single above-average discipline. Medical and Health Sciences are not very different in this regard. Only in Natural Sciences and in Engineering and Technology does the Czech Republic’s performance begin to resemble that of Slovenia and Portugal. One plausible interpretation of the relative weakness in Social Sciences is the long-term heritage of the communist regimes under which the social sciences were particularly adversely affected. Alternative explanations include differences in WoS coverage between countries, differences in publication productivity, and differences in the share of total funding allocated to these disciplines.

Finally, we quantify the country-specific propensity towards high quality research (as approximated using journal AIS). Table 2 presents the differences in the quantity-quality gradient between two groups of countries: the six post-communist countries of CEE and the six EU-15 countries. The quantity-quality gradient equals the ratio of quantity to quality of relative publication performance for each group of countries in each discipline (WoS Category). Specifically, for each discipline we computed the ratio of the two gradients across the two groups of countries and then we averaged these discipline-specific ratios across WoS disciplines by our broad research areas. The average ratio for a given research area (e.g., Natural Sciences) is thus defined as

where the index i refers to an individual discipline (e.g., Microbiology). Quality and quantity are defined as above. When the value of the ratio exceeds 1, this reflects a strong propensity towards publication quantity at the expense of quality in CEE countries. This tendency is apparent in all research areas, but is strongest in Social Sciences.

It is more than plausible that scientific performance in CEE countries is lower than in our EU-15 comparison countries thanks largely to a lower extent of funding (Vanecek 2008). But it is less clear why a lower funding level should skew the quality-quantity comparison within CEE countries towards quantity and why this tendency should be stronger in Social Sciences. Our descriptive evidence thus motivates future work on the incentives and funding mechanisms that the social sciences face in CEE countries.

Concluding notes

Our descriptive evidence implies that when it comes to scientific publication performance measured a quarter of a century after the fall of communism, post-communist CEE EU member states still lag noticeably behind their Western counterparts. In the majority of narrowly defined scientific disciplines both their total publication performance and especially their high quality publication performance are far below the average of our comparison set of EU-15 countries. In relative terms, post-communist CEE countries perform better in natural sciences, engineering and technology than in social or medical sciences. Post-communist countries’ publication output is also notably focused on quantity as opposed to quality (as approximated by journal AIS), which likely distracts their limited resources away from internationally more competitive research. This focus on quantity may be related to prevailing deficiencies in public governance (scientific evaluation and funding mechanisms) in the post-communist countries (Jonkers and Zacharewicz 2016). Future research could focus on case studies of those specific scientific disciplines where post-communist countries appear competitive and ask how this success has been generated. Ultimately, a policy-relevant insight into the sources of these publication output differences requires a full understanding of discipline-specific R&D expenditures, funding allocation mechanisms, numbers of researchers, research evaluation procedures, and promotion and hiring practices.

Notes

See, e.g., Shleifer and Treisman (2014) for a broad assessment of the post-communist transition.

Given that we focus on recent publications, we abstain from analyzing their citation impact. This is an important area for future research.

A few studies have attempted to deal with this data constraint: Abramo and D’Angelo (2014b) approximate researchers’ pay levels within a country to convert the average citation impact per paper for each author into a person-specific productivity index. Bentley (2015) compares productivity per researcher across countries based on a pay-level survey. Boyle (2008) contrasts pay levels by field between two countries to explain publication output gaps. Bornmann et al. (2014) normalize citation impacts using GDP per capita.

Mingers and Leydesdorff (2015) provide a comprehensive review of theory and practice in scientometrics, which highlights much recent progress in citation impact measurement.

There are several other studies that consider the CEE countries' publication and citation aggregates (Abbott and Schiermeier 2014; Must 2006; Vinkler 2008; Kozlowski et al. 1999; Vanecek 2008, 2014; Radosevic and Yoruk 2014) and collaboration between post-communist scientists and their EU-15 counterparts (Gorraiz et al. 2012; Kozak et al. 2015; Makkonen and Mitze 2016). Some studies focused on specific fields of science also include post-communist countries; see, e.g., Fiala and Willet (2015) for computer science and Pajić (2015) for social sciences.

Using a more sophisticated approach, Ciminiet al. (2014) assess the competitiveness of nations using Scopus citation patterns across 26 disciplines.

The AIS measures the average per-article influence of the papers published in a journal. Formally, it is defined as 0.01*EigenFactor Score/X, where \(X\) is the 5-year journal article count relative to the 5-year article count from all journals. The EigenFactor Score reflects the overall importance of a journal by utilising an algorithm similar to Google’s PageRank. The AIS is thus similar to the more widely-used Impact Factor (IF), but it has several important advantages. First, it puts more weight on citations from more prestigious journals, making the measure more informative compared to raw citation counts. Second, unlike the standard IF, the AIS uses a five-year time window. Third, the AIS ignores citations to articles from the same journal, making it harder to manipulate. Clearly, neither the AIS nor the IF are particularly well suited to assessing the quality of a publication or a researcher. However, the AIS becomes useful with a higher degree of aggregation; this would be undermined only if some groups of researchers were to systematically publish journal articles whose impact did not on average correspond to that of the journals they were published in.

The RCI compares the average citation rate of articles published in scientific journals in a given discipline in a given country during a given year with the average citation rates of all articles published in that year and discipline worldwide.

More precisely by population aged 15–64 in the year 2015.

The computation of the means does not reflect population differences of countries, so that country observations are counted with equal weight. We exclude the particular country in question from the computation of the mean across the other 11 countries to ensure that the mean used is not affected by the country in question.

In producing our figures, we have applied some basic WoS Category restrictions: We exclude 5 disciplines that do not belong to any of the broad research areas and another 5 very small disciplines that have on average fewer than 25 articles per country during our 5-year window. The charts also omit those WoS Categories that fall outside their scale: There are 51 disciplines omitted from the Netherlands, 18 from Sweden, 11 from Finland, 8 from Slovenia, and 3 from each of Austria, Belgium, Croatia and Portugal. About half of these disciplines belong to the Social Sciences. We left out these observations in order to maintain reasonable readability within our figures, but they were still used to compute the statistics in Tables 1 and 2. Note that most of these omissions correspond to highly productive fields in Western countries; hence, the charts are somewhat biased in favor of the post-communist countries.

It is plausible that our comparisons, which normalize for population only, systematically favor smaller countries that manage to maintain a minimum of viable scientific activity in each field of science. This is an interesting area for future research.

References

Abbott, A., & Schiermeier, Q. (2014). Central Europe up close. Nature, 515(7525), 22–25.

Abramo, G., & D’Angelo, C. A. (2014a). Assessing national strengths and weaknesses in research fields. Journal of Informetrics, 8(3), 766–775.

Abramo, G., & D’Angelo, C. A. (2014b). How do you define and measure research productivity? Scientometrics, 101(2), 1129–1144.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Di Costa, F. (2008). Assessment of sectoral aggregation distortion in research productivity measurements. Research Evaluation, 17(2), 111–121.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Viel, F. (2011). The field-standardized average impact of national research systems compared to world average: the case of Italy. Scientometrics, 88(2), 599–615.

Bentley, P. J. (2015). Cross-country differences in publishing productivity of academics in research universities. Scientometrics, 102(1), 865–883.

Bornmann, L., & Leydesdorff, L. (2013). Macro-indicators of citation impacts of six prolific countries: InCites data and the statistical significance of trends. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056768.

Bornmann, L., Leydesdorff, L., & Wang, J. (2014). How to improve the prediction based on citation impact percentiles for years shortly after the publication date? Journal of Informetrics, 8(1), 175–180.

Boyle, G. (2008). Pay peanuts and get monkeys? Evidence from academia. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 8(1), 1–24.

Cimini, G., Gabrielli, A., & Labini, F. S. (2014). The scientific competitiveness of nations. PLoS ONE, 9(12), e113470. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113470.

Fiala, D., & Willett, P. (2015). Computer science in Eastern Europe 1989–2014: A bibliometric study. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 67(5), 526–541.

Garfield, E. (1979). Is citation analysis a legitimate evaluation tool? Scientometrics, 1(4), 359–375.

Gorraiz, J., Reimann, R., & Gumpenberger, C. (2012). Key factors and considerations in the assessment of international collaboration: A case study for Austria and six countries. Scientometrics, 91(2), 417–433.

Jonkers, K., & Zacharewicz, T. (2016). Research performance based funding systems: A comparative assessment (No. JRC101043). Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, Joint Research Centre.

King, D. A. (2004). The scientific impact of nations. Nature, 430(6997), 311–316.

Kozak, M., Bornmann, L., & Leydesdorff, L. (2015). How have the Eastern European countries of the former Warsaw Pact developed since 1990? A bibliometric study. Scientometrics, 102(2), 1101–1117.

Kozlowski, J., Radosevic, S., & Ircha, D. (1999). History matters: The inherited disciplinary structure of the post-communist science in countries of central and Eastern Europe and its restructuring. Scientometrics, 45(1), 137–166.

Makkonen, T., & Mitze, T. (2016). Scientific collaboration between ‘old’and ‘new’member states: Did joining the European Union make a difference? Scientometrics, 106(3), 1193–1215.

May, R. M. (1997). The scientific wealth of nations. Science, 275(5301), 793–796.

Mingers, J., & Leydesdorff, L. (2015). A review of theory and practice in scientometrics. European Journal of Operational Research, 246(1), 1–19.

Moed, H. F., Burger, W. J. M., Frankfort, J. G., & Van Raan, A. F. (1985). The use of bibliometric data for the measurement of university research performance. Research Policy, 14(3), 131–149.

Must, Ü. (2006). “New” countries in Europe-Research, development and innovation strategies vs bibliometric data. Scientometrics, 66(2), 241–248.

Pajić, D. (2015). Globalization of the social sciences in Eastern Europe: Genuine breakthrough or a slippery slope of the research evaluation practice? Scientometrics, 102(3), 2131–2150.

Radosevic, S., & Yoruk, E. (2014). Are there global shifts in the world science base? Analysing the catching up and falling behind of world regions. Scientometrics, 101(3), 1897–1924.

Shleifer, A., & Treisman, D. (2014). Normal countries: The East 25 years after communism. Foreign Affairs, 93(6), 92–103.

Smith, M. J., Weinberger, C., Bruna, E. M., & Allesina, S. (2014). The scientific impact of nations: Journal placement and citation performance. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e109195.

Vanecek, J. (2008). Bibliometric analysis of the Czech research publications from 1994 to 2005. Scientometrics, 77, 345–360.

Vanecek, J. (2014). The effect of performance-based research funding on output of R&D results in the Czech Republic. Scientometrics, 98(1), 657–681.

Vinkler, P. (2008). Correlation between the structure of scientific research, scientometric indicators and GDP in EU and non-EU countries. Scientometrics, 74(2), 237–254.

Acknowledgements

This study was completed with the support of the Czech Academy of Sciences, as part of its Strategy AV21. The authors wish to thank J. Kovařík for his help in obtaining information from the WoS, and two anonymous referees for valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jurajda, Š., Kozubek, S., Münich, D. et al. Scientific publication performance in post-communist countries: still lagging far behind. Scientometrics 112, 315–328 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2389-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2389-8

Keywords

- Bibliometrics

- National comparison

- Scientometric indicators

- Article Influence Score

- Web of Science

- Post-communist Europe