Abstract

Parental involvement is widely acknowledged as a critical factor influencing the college choice process among families. What is not clear, though, is whether this parental driven factor also takes place at the school level along with school related factors. Using a national sample of 9th grade students drawn from about 900 schools, we found that parental involvement also operates at the school context along with a high school’s academic press. Moreover, at both individual- and school-level contexts, parental involvement creates a “college-going” cultural capital in the form of attainment of milestones towards college.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Standards-based and high-stakes processes characterize the 21st century policy context of K-12 education reform in the United States (Hamilton et al. 2008). Policies such as the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 (2012) and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 (2015), as well as initiatives like the Common Core Standards and Race to the Top have emphasized mandates and incentives that seek to raise educational standards, increase expectations for students, and engage in high-stakes assessment (Hamilton et al. 2008; Viteritti 2012). Within schools, this educational climate can be associated with the concept of academic press, defined as the emphasis a school places on providing clear standards of student achievement and resources to develop students’ academic success (Phillips 1997). Although literature clearly demonstrates that academic press is linked to higher student performance (e.g., Goddard et al. 2000; Roney et al. 2007; Smith 2002), there is a dearth of scholarship explicitly and empirically using the concept to consider post-K-12 planning and student outcomes. Yet, making this connection could assist in understanding how today’s educational climate links with college and career readiness, which are also major parts of the nation’s education policy agenda.

Using data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ (NCES) High School Longitudinal Study of 2009, this study examines the relationship between school academic press, students’ college readiness, and parental involvement in fostering college readiness. Conceptually, there is alignment between the notion of academic press and the development of college-going culture within schools, given that college-going cultures emphasize schools intentionally cultivating aspirations and committing resources for college preparation (Corwin and Tierney 2007; McClafferty et al. 2002). Our study empirically elucidates whether there is a direct relationship between the concept of academic press and college readiness.

Furthermore, extant research and conceptual models widely demonstrate parental involvement as a critical factor influencing the college choice process (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Hossler et al. 1989; Perna 2006; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008; Tierney and Auerbach 2005). Unfortunately, in college access and choice literature, scholars “know the kinds of factors that influence predisposition, but we still do not know how students’ understandings of education are formed through the interaction of family background, school context, and academic performance,” (Bergerson 2009, p. 116). To further move scholarship forward, this study considers academic press as a possible link in understanding how critical variables impacting students’ college readiness interact with or do not interact with one another. Doing so is particularly important given that legislation such as NCLB of 2001 (2002) expanded opportunities for parental engagement with schools and mandated that states in need of funding for under-resourced (Title I) schools develop practices for involving families, “based on the most current research that meets the highest professional and technical standards, on effective parental involvement that fosters achievement to high standards for all children.” (Section 1111.d). ESSA (2015) has continued and even expanded upon previous NCLB directives for familial engagement in schools, demonstrating a continued interest among education practitioners and policymakers for access to up-to-date empirical research related to the connection between school and home for student success.

Yet, a number of quantitative studies adopt an input–output regression approach that ignores the impact of parental involvement and school processes on the attainment of milestones towards college (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; McCarron and Inkelas 2006; Perna and Titus 2005). Thus, we still know very little from a quantitative perspective about how parental involvement, the school context, and the familial context interact within the college-going process. The quantitative research that does adopt a process approach for parental involvement is based on dated cohorts of students, beginning in the late 1950s (e.g., Sewell and Shah 1968), late 1980s (e.g., Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Rumberger 1995; Stage and Hossler 1989), and early 1990s (e.g., Perna and Titus 2005). Few of these studies sought to uncover the process linking family and school contexts in readiness for college through the analytic approach of structural equation modeling (SEM) (e.g., Sewell and Hauser 1992; Sewell and Shah 1968; Stage and Hossler 1989). And, none of those SEM-based studies either modeled processes taking place at the individual and school levels in a simultaneous manner, or corrected for design effects associated with complex survey analyses as those present in national databases (Heck and Thomas 2015; Stapleton 2013).

Therefore, in addition to filling a need within the current education policy context for research that can inform parental engagement in schools for improved student outcomes, we also seek to update previous research on the topic. Pascarella (2006) best articulated the reasons as to the importance of conducting replication studies in higher education. Replicated studies help to ascertain the veracity of past scholarship; and, affirmation of previous findings increases the likelihood that recommendations will be implemented (Pascarella 2006). In doing so, this study utilizes a recent cohort of high school students from the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 while adopting the most advanced multilevel SEM procedures to model the role of academic press and parental involvement in students’ readiness for college taking place within families and across schools. Accordingly, the following research questions guided this inquiry: (1) Does high school academic press affect students’ attainment of milestones toward college? (2) What is the relationship between parental involvement, academic press, and students’ attainment of milestones towards college?

Literature Review

Reaching critical milestones along the pathway to college requires students’ acquisition of academic resources and preparation, which include a combination of students’ test scores, academic performance, and the quality and intensity of the high school curriculum (Adelman 1999; Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Hossler et al. 1989). When students are provided access to school academic supports and resources, there is greater likelihood that they will enroll in college (Hossler et al. 1989; McDonough 1997; Perna 2006). While scholars have differed regarding what combination of school characteristics most effectively promotes the academic qualifications and college aspirations that can lead to college readiness, there is strong consensus that school culture creates or constrains students’ pathways to college (Oseguera 2013).

One of the most popular frames used to connect school culture to college readiness outcomes is college-going culture. When schools systematically create organizational norms and structures related to college readiness, they develop a college-going culture. McClafferty et al. (2002) define college-going culture as a way for “ensuring that the schools devote energy, time, and resources toward college preparation so that all students are prepared for a full range of postsecondary options upon graduation” (p. 5). Similarly, Corwin and Tierney (2007) suggest that college-going culture “in a high school cultivates aspirations and behaviors conducive to preparing for, applying to and enrolling in college. A strong college culture is tangible, pervasive and beneficial to students” (p. 3). The presence of a college-going culture is particularly important to low-income and first-generation students who may predominantly depend on their schools as form of social capital and as a resource in college preparation (Auerbach 2004; McDonough and Calderone 2006; McDonough and Fann 2007).

Yet, schools often restrict or extend information (e.g., about college preparation, course offerings) to students based on their academic track or other factors, which is known as gatekeeping (Hill Collins 2009; McDonough and Fann 2007). Thus, while extant scholarship demonstrates that school culture can positively impact academic achievement and help students become college ready (ACT 2004; Lee 2006; Martinez and Klopott 2005; Phillips 1997; Shouse 1996), students can be particularly vulnerable to the uneven provision of academic rigor as well as the presence of gatekeeping, which run counter to the concept of college-going culture for all and reinforces educational inequity (Hill Collins 2009; McDonough and Fann 2007).

Students’ ability to benefit from parental encouragement and involvement in college going is also prone to inequities (Arnold et al. 2012; George Mwangi 2015; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008; Savitz-Romer and Bouffard 2014). Regardless of race, socioeconomic status (SES), or other social identities, parents’ educational expectations shape children’s postsecondary predisposition and academic endeavors (Cooper et al. 2005; Holland 2010). However, while parental expectations of their children obtaining a college degree affect whether students apply to college, parents’ own awareness of college impacts their expectations of and involvement in their child’s preparation process (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000). The literature clearly concludes that while parents play a critical role in college preparation, parental support can be hindered or enhanced by structural factors, which creates inequities for students in successfully navigating college choice (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; George Mwangi 2015; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008).

In addition to providing emotional support and encouragement, parents’ involvement in their children’s experience in school has significant implications for academic development and academic preparation for college (Fan and Williams 2010; Perna and Titus 2005; Tierney and Auerbach 2005). In the middle and high school contexts, the role of parental involvement in school activities is pivotal in enabling this process (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Fan and Chen 2001; Perna and Titus 2005; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008). Scholars find that parental interaction with schools can occur in various ways. Hossler et al.’s (1989) three-stage college choice framework suggests that parents be involved with their child’s school and engage in regular communication with teachers and guidance counselors. In their study on the role of parental involvement in college enrollment, Perna and Titus (2005) found that the odds of a student enrolling in a 2-year or 4-year college immediately after high school increased with the frequency that parents discussed education-related topics, contacted their child’s school to volunteer, and initiated communication with the school regarding academics. Even brief engagement with their child’s school can demonstrate parents acting as an educational advocate, thus increasing the likelihood that the child will receive the resources needed from their school (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000).

However, there is less empirical evidence on the effects of parental involvement for high school outcomes than there is for elementary school outcomes, leaving high school practitioners with less research to inform intervention and programs for involving parents within schools (Hill and Chao 2009; Ross 2016). Although schools should “engage parents when and where they are and when they are available” (Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008, p. 575), many high schools still struggle with sustaining parental engagement, particularly related to college-readiness (Holcomb-McCoy 2010). Even when high school staff cite wanting to engage with parents about college opportunities, they are often not able to actualize this aspiration, particularly when they are located in high poverty areas (Holcomb-McCoy 2010). For example, some researchers suggest that parents of Color and low-SES parents are less likely to participate in formal school activities due to barriers such as working multiple jobs, language barriers, and mistrust in the educational system (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Fordham 1996; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008). Additionally, families without “college knowledge” may also rely on schools to provide college planning resources and information, but may not be aware of how to engage with their children’s school during the college preparation process (Engberg and Gilbert 2014; Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch 1995). Teachers and other school staff can wrongly perceived parents’ lack of traditional involvement from a deficit perspective as disinterest in students’ education (Tierney and Auerbach 2005). These studies concluded that teachers and other school staff often wrongly perceived these parents’ lack of traditional involvement as disinterest in students’ education. This misperception can lead to delimited academic opportunities, resources, and support being provided if students do not have additional educational advocates (McDonough 1997; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008). A stronger understanding of the connection between the school environment itself and parental involvement for understanding high school outcomes like college readiness are needed in order to help schools better understand what they can do to foster that involvement.

We focus on school’s academic press within our study given that when college going and academic rigor becomes a part of the school’s culture, this should allow opportunities for schools to institutionalize engagement with parents around college readiness (Corwin and Tierney 2007). We examine the relationship between school culture, parental involvement, and students’ attainment of milestones towards college by centering on the concept of academic press. A less referenced model for understanding the role of school culture in college-going outcomes, academic press refers to the focus schools place on resources and standards that develop students’ academic success, promote the pursuit of rigorous academic goals, and foster student learning (Lieber 2009; Odden and Odden 1995; Phillips 1997). It differs from college-going culture (or is sometimes integrated into that framework) in that its main emphasis is on the strong presence of academic pressure and excellence integrated into a school’s overall culture. Academic press may provide an effective counter to gatekeeping because it suggests the elimination of non-rigorous academic curricula and an investment in highly credentialed teaching staff (Martinez and Klopott 2002).

Like high parental expectations, academic press also emphasizes high standards and positively impacts student achievement (Goddard et al. 2000; Smith 2002). Despite that similarity, given that the focus of academic press is on the school environment and culture, less is understood regarding whether or how a school’s academic press connects to parental engagement or to the relationship between parents and schools for college readiness. Our study addresses this by investigating whether there is a relationship between a school’s academic press and parental involvement within the college readiness context.

Conceptual Model

Our conceptual model builds upon foundational and contemporary college access and choice literature related to the role of parents and schools (e.g., Arnold et al. 2012; Corwin and Tierney 2007; George Mwangi 2015; Hill and Tyson 2009; Hossler et al. 1989; Perna 2006; Perna and Titus 2005; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008; Sewell and Hauser 1992; Sewell and Shah 1968; Stage and Hossler 1989; Tierney and Auerbach 2005). Overall, this scholarship illustrates that the relationships between students, parents, and schools help students navigate the educational system and the college preparation process. Our study investigates this interaction by integrating the concept of academic press. In so doing, we bring about a multilevel perspective whereby both family and school contexts are considered in a simultaneous manner as potential predictors of attainment of milestones within families and across schools.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) has been regarded as having a significant impact on academic ability, academic preparation and achievement (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Perna 2005, 2006; Sirin 2005; White 1982). Previous research highlights the direct impact of SES on ability (Lee and Burkam 2002; Reyes and Stanic 1988). Based on a meta-analysis of over 100,000 students from over 6800 schools, Sirin (2005) reported a medium to strong association between SES and academic achievement. Lee and Burkam (2002) suggest that SES contributes to inequitable access to resources that impact the development of cognitive skills among children. Their findings reveal a strong relationship between SES and cognitive ability.

Previous work also emphasizes a relationship between SES and parental involvement, suggesting that students from a higher SES background have a greater likelihood of having parents who are involved in their academic experiences (Eagle 1989; Leppel et al. 2001; Ma 2009). Eagle (1989) suggests that SES plays a key role in the extent to which parents are involved in their children’s education.

Ability

Previous research suggests that a student’s own ability is a predictor of the extent to which a parent would be involved in a student’s academic schooling (Eccles and Harold 1993; Patel and Stevens 2010). Students with stronger academic or cognitive abilities have a greater likelihood of parents’ involvement in their schooling and educational experiences. In particular, Patel and Stevens (2010) suggest that parents’ perceptions of their students’ academic abilities affects the extent to which they are involved in their students’ educational experiences in school. Furthermore, academic ability has been linked to academic achievement (Rohde and Thompson 2007). Accordingly, our conceptual model reflects the impact of academic ability on parental involvement, as well as academic ability on the attainment of milestones toward college.

Parental Involvement

Consistent with Perna and Titus (2005), our model regards parental involvement as a form of social capital that bestows important resources during a student’s path to college. Parental involvement fosters student development through communicating expectations and providing strategies to become academically prepared (Hill and Tyson 2009; Savitz-Romer and Bouffard 2014). Hill and Tyson (2009) regard this form of parental involvement as academic socialization, which has the strongest impact on students’ educational outcomes. Additional research supports the finding that parental involvement is strongly associated with the extent to which students become academically prepared for college (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Fan and Chen 2001; Perna and Titus 2005). Based on these findings, our conceptual model highlights the direct impact of parental involvement on the attainment of milestones toward college.

Academic Press

Based on the work of Phillips (1997), we assume that a school’s academic press is a relevant construct to appraise the school context. Academic press represents the shared or normative practices, policies, values, and beliefs in a school that bolster high academic success (Shouse 1996). Academic press puts special emphasis on the qualification of human resources allocated to improving academic performance and to the curricular components of a school (Lee 2006). Accordingly, evidence of academic press includes rigorous curricula, promotion of enrollment in higher-level courses like AP courses, and policies that increase numbers of certified teachers and counselors (Darling-Hammond 2000; Kaplan and Owings 2001; Lee et al. 1997; Lee 2006).

In alignment with Perna’s (2006) nested conceptual model of college choice, and with the sociological attainment literature (e.g., Sewell and Hauser 1992), our model regards the attainment of milestones as the result of two processes operating at both the individual and the school context in a simultaneous manner. The family context is shaped by the family’s socioeconomic status, which provides the foundation for academic preparation, familial social capital (e.g., parental involvement), familial cultural capital (e.g., parental education level), as well as familial financial resources (e.g., family income) in creating opportunities to attend college. This social and cultural capital enables parents to be involved in their students’ schooling, which paves the way for their future postsecondary opportunities (Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Rowan-Kenyon et al. 2008). The second layer of our model is comprised of the school context. This context largely mirrors the process taking place at the individual level. In other words, our model presumes that families are prone to enroll their children in schools that strongly resemble their family status and the process by which they follow in readying their children for postsecondary opportunities (Alexander and Entwisle 1996; Goldring and Phillips 2008; Lee and Burkam 2002; Schneider et al. 1998). It is in this context in which the impact of a school’s emphasis on academic press would be evidenced by its influence of parental involvement at the school level, as well as on students’ attainment of milestones towards college at the aggregate level.

Methodology

Model Testing Strategy

In view of the two-level contextual nature of our model (see Fig. 1) and the stratified nature of our sample, we opted for a multilevel approach in answering our research questions.Footnote 1 We first examined the extent to which our attainment of milestones latent factors operate in a comparable manner across both families and schools, a condition referred to in the multilevel SEM literature as configural (Stapleton et al. 2016), or contextual (Marsh et al. 2012). If found viable, the configural or contextual model allows one to compute the intraclass correlation (ICC) of the factor. The ICC facilitates the estimation of that portion of the latent factor’s variance accounted for by the schools (Heck and Thomas 2015; Hox et al. 2018; Stapleton et al. 2016). Having ascertained that the latent factors operate at both the individual and school level, we examined the viability of our model using multilevel SEM. Then, we tested for a cross-level effect of a school’s academic press on the effect of parental involvement on attainment of milestones at the family level. We proceeded with this cross-level test once we documented the extent to which the effect of parental involvement on attainment of milestones varied significantly across schools following Heck’s suggestions (R. Heck, personal communication, January 19, 2018).

Evaluation of Fit

The SEM literature recommends using multiple indices of fit, which varies according to such considerations as sample size and whether the data are multivariate normal (Finney and DiStefano 2013; Heck and Thomas 2015; Schreiber et al. 2006). In view of the fact that our data departed from the assumption of multivariate normality (see Table 1), we opted for Mplus’ MLR estimator to generate both robust point estimates and robust goodness of fit indices. The MLR estimator has the added advantage of relying on full information likelihood for handling missing cases, a method recognized as state of the art in the SEM literature (Enders 2013; Heck and Thomas 2015). Our robust fit indices included: (a) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) or Tucker Lewis index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Both the CFI and the TLI have a range of possible values between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 signifying good fit (Wang and Wang 2012). We considered RMSEA less than 0.06 as signifying a good fit (Byrne 2012; Hu and Bentler 1999). Following Hu and Bentler’s (1999) suggestion, we consider SRMR values less than or equal to 0.08 to signify good model fit. We also report a χ2 value for our model while cautioning the reader that this index is highly sensitive to sample sizes (Byrne 2012). In general, small sample sizes tend to produce χ2 values supporting the model while the contrary is true for large samples (Wang and Wang 2012).

Reliability Estimates

We relied on Raykov’s (1997) composite estimator ω to appraise the overall reliability of each of our latent factors. Though widely popular, the Cronbach’s alpha (1951) is known to provide inaccurate estimates of the internal consistency of scales by both item response theory (e.g., Sharkness and DeAngelo 2011) and confirmatory factor analysis (e.g., Wang and Wang 2012). To begin, Cronbach’s alpha incorrectly presumes that the items making up a scale are measured without error (Hancock and Mueller 2001; Sharkness and DeAngelo 2011). It also relies on the unrealistic assumption that the items load in a single latent factor, while displaying similar loadings in that factor (Raykov 1997, 2009; Stapleton et al. 2016). In contrast, Raykov’s omega estimate assumes that the strength of the association with the latent factor varies across items, while acknowledging that the items themselves are prone to measurement error (Raykov 1997).

Data Source

This study relies on data from the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09), a nationally-representative longitudinal survey administered by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). HSLS:09 follows a stratified sample of 9th grade students beginning in 2009 and is continuing to track students through postsecondary education. Our sample is comprised of about 19,000 individuals who enrolled in about 900 schools.Footnote 2 When weighted, this sample represents approximately 3.4 million students.

Accounting for Sampling Design Effects

HSLS:09 follows a stratified multistage sampling strategy with unequal probability of sample selection to approach the national population of 9th graders in 2009. We selected the panel weight W3W1W2STU to account for those 9th graders who participated in the base year (2009), the first follow-up (2012), and who also had high school transcripts collected in the 2013–2014 period.

The straightforward use of stratified samples is prone to produce biased point estimates (Stapleton 2013), while increasing the probability of erroneously finding significant results (Heeringa et al. 2010; Heck and Thomas 2015; Thomas and Heck 2001). Accordingly, we used the Mplus option Cluster to take into account the fact that our sample of students were nested within schools; doing so allowed us to correct standard error of the estimates. We incorporated the panel weight W3W1W2STU in all analyses to generate unbiased point estimates as well. And, we used the Mplus option of a two-level analysis in all of our multilevel models.

Latent Factors and Measures

Our model consists of one variable, academic ability, and four latent factors consisting of: Parental Involvement, Attainment of Milestones by 12th grade, SES, and High School Academic Press. The model regards SES and Academic Press as exogenous latent factors. The endogenous variable and latent factors are Academic Ability, Parental Involvement, and Attainment of Milestones.

Academic Ability

We relied on a single item score (X1TXMTH) to appraise academic ability. This standardized test score was administered in 2009 when the participants were in 9th grade. The test seeks to assess algebraic reasoning and ability in mathematics (Ingels et al. 2011). While we would have preferred using several indicators to demonstrate multiple domains of academic ability, math ability is the only ability measure available in HSLS:09.

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

The extant literature stresses the impact that the cultural capital of a familial socioeconomic status (comprised of parental education and family income) can have on the overall educational achievement of students (Jaeger 2011), and ultimately in college-going behavior (Engberg and Wolniak 2010; Gibbons and Borders 2010; Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb 2010; Perry and McConney 2010; Wells and Lynch 2012). While family income has been commonly used as an indicator of wealth, the inclusion of parental education captures additional impacts in the student environment of social and cultural capital (Jaeger 2011; White 1982). Accordingly, in appraising SES, we included three key variables from HSLS:09, including mother’s highest education (MOED), father’s highest education (FAED), and family income (BYINCOME). The data for these variables were all collected in 2009 when the students were in 9th grade.

Parental Involvement

Cabrera and LaNasa (2000) suggest that parental encouragement includes both motivational and behavioral dimensions. While the motivational component of parental encouragement contributes to managing and maintaining educational expectations (Savitz-Romer and Bouffard 2014), the behavioral component is more proactive in creating educational opportunities and has been found to be associated with high school students’ academic achievement (Hill and Tyson 2009; Stewart 2008) as well as with their actual college enrollment (Perna and Titus 2005). Consistent with this literature, our latent factor of parental involvement was appraised with five indicators of proactive parental involvement when the students were in 11th grade: (1) Parent discussed career options with the student (PENCAR); (2) Parent discussed school courses and/or school programs with the student (PENCOURSE); (3) Parent discussed preparing for college entrance exams with the student (PENEXAM); and (4) Parent discussed applying for college with the student (PENAPPLY).

Attainment of Milestones

Being prepared for college has been termed by many researchers in the field of higher education as college readiness, which can be defined by the “attainment of milestones,” signifying academic preparation for success in college (e.g., Adelman 1999; Berkner et al. 1997; Cabrera et al. 2005; Calcagno et al. 2007; Wiley et al. 2011). Likewise, The College Board’s 2011 research report on college readiness addresses the characteristics associated with college readiness, including SAT scores, high school grades, and the rigor of academic coursework (Wiley et al. 2011). Metrics such as high school grade point average, college entrance exam scores, class rank, and academic coursework have been associated with predicting success in college (Berkner et al. 1997).

Our latent factor of attainment of milestones includes three indicators signifying college readiness and preparation for college: (1) Student took the SAT/ACT by 12th grade (TOOKATEST); (2) Student has cumulative GPA in all academic subjects by 12th grade (HSASGPA); (3) Highest mathematics course taken by the student by 12th grade (HIMATH); and (4) Student applied to college (APPLIEDC).

High School Academic Press

Phillips’ (1997) review of the literature on academic press suggests that schools are most effective when offering demanding course curriculum and employing qualified teachers and administrators. Such an approach is consistent with the extant literature. Teacher certification, a measure of teacher quality (Kaplan and Owings 2001), has been found to be the most consistent and best predictor of student achievement in math and reading (Cabrera et al. 2006; Darling-Hammond 2000; Lee 2006; Lee et al. 1997).

The indicators we selected for this latent factor include (1) the number of certified math teachers (CMATHT); (2) the number of certified science teachers (CSCIT); and (3) the number of certified counselors (CERTCO).

Summary Statistics

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for the measures used in testing our model. As shown in Table 1, the Doornick-Hansen and Mardia tests indicated the sample violates the assumption of multivariate normality, which called for our use of Mplus’ Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimator (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015) to generate robust point estimates. Table 1 also reveals that our level-1 measures display non trivial intraclass correlations (ICCs) ranging from 0.154 to 0.332, signifying that each variable’s variability is “parsed” into two components: within families and between schools (Stapleton et al. 2016). Such strong correlation among subjects within schools further supported our selection of multilevel SEM as a mechanism to avoid downward bias estimation problems, while modeling for the process accounting for such interdependence among subjects (Heck and Thomas 2015).

Results

Our results are organized in two sections. The first section documents the measurement properties of our latent factors and their corresponding items across families and between schools. It also reports the extent to which the configural model is a viable representation of the multilevel data. The second section reports the structural models seeking to explain determinants of attainment of milestones across our two levels of analyses.

Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

Aside from the χ2 index (χ2(111) = 1032.9, p value < .01), the rest of the evaluation fit indices converge in supporting our measurement model at both the school and individual levels (see Table 2). Both the CFI value of 0.970, and the TLI value of 0.960 are above 0.95, while the RMSEA index of 0.018 is less than 0.05. The within SRMR value of 0.037 and between SRMR value of 0.058 are below the 0.08 threshold (see Table 2).

The reliability of the latent factors within families ranges from 0.680 for SES, 0.802 for parental involvement, to 0.724 for attainment of milestones. The latent constructs are reliably appraised at the school level as well. The reliability of HS academic press is 0.954, while the corresponding reliabilities for SES and parental involvement are 0.950 and 0.837, respectively.

The magnitude and pattern of factor loadings across both levels also support the consistency in measuring our constructs. Within families, the loadings ranged from 0.504 for having applied to colleges (APPLIEDC), an indicator of attainment of milestones, to 0.793 for parents having discussed career options (PENCAR), an indicator of parental involvement. Across schools, the range of loadings was of 0.300 for APPLIEDC, an indicator of attainment of milestones, to 0.974 for the number of certified science teachers (CSCIT), an indicator of the school-level latent factor HS academic press.

We also found that the configural model is a viable representation of our stratified data.Footnote 3 The Muthén-Satorra’s MLR rescaled test of difference in χ2 (see Heck and Thomas 2015, p. 173) was significant (Δχ2(8) = 255.9, p value < .01). The configural model also yielded acceptable indicators of fit (RMSEA = 0.019; CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.958; SRMR within = 0.037, SRMR between = 0.071). The last column in Table 2 reports the ICC estimates of the latent factors under the configural model, which are corrected for measurement error at level-1 (Heck and Thomas 2015). In the case of SES, the ICC of 0.437 signifies that almost 44% of the variance in the latent factor is accounted by schools. For the latent factor attaining of milestones, almost a third of its variance lies within schools. In the case of the parental involvement latent factor, almost 20% of its variance is accounted for by schools. In all, both configural and ICC results support the use of multilevel SEM to account for latent factors operating at the school level. Moreover, meeting the condition of a configural model operating in both strata also implies that the latent factors of SES, parental involvement, and attainment of milestones have the same meaning at the school level as they do at the family level (Heck and Thomas 2015).

Multilevel SEM Results

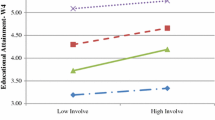

Figure 2 depicts the structural coefficients associated to the different equations underscoring the milestone towards college model within families and between schools. Hypothesized effects found significant are represented with a straight line. Dotted lines depict hypothesized paths found non-significant. We report all paths in standardized units.

Aside from the χ2 test (χ2(138) = 1732.9, p value < 0.05), the bulk of fit indices suggest that our multilevel model of attainment of milestones is a plausible representation of the hierarchical data. As indicated by CFI and the Tucker-Lewis Fit Index (TLI) values of 0.957 and 0.947, the hypothesized model provides a better fit to the data next to a model assuming no associations among the latent factors in both between schools and within families. This conclusion is further strengthened by a REMSA of 0.021, which is far below Hu and Bentler’s (1999) recommended threshold of 0.05. The SRMR results suggest that the model reproduces the variances and covariances among the variables slightly better within families (SRMR = 0.041) than it does between schools (SRMR = 0.076). However, the SRMR between schools falls within the acceptable threshold of 0.08 or less (Hu and Bentler 1999).

At the family level, we found all of our hypothesized paths to be significant (see lower level in Fig. 2). The size of the structural paths ranges from being small (Ability → Parental Involvement = 0.135) to being high (Ability → Attainment of Milestones = 0.511). The model accounted for 10.7% of the variance in academic ability, explained nearly 13% of the variance in parental involvement in school activities, and accounted for nearly 52% of the variance in attainment of milestones. Parental SES has significant and positive effects on ability (0.327), parental involvement (0.288), and attainment of milestones (0.216). Parental involvement in school activities has a positive but moderate effect on attainment of milestones (0.231). Its effect is slightly larger than the one originating from SES (0.216), although substantially smaller than the one originating from the ability of the student (0.511). All in all, our results are quite consistent with our review of the literature of (e.g., Eagle 1989; Fan and Chen 2001; Hossler et al. 1991; Sewell and Shah 1968; Sewell et al. 1980; Sirin 2005; Stage and Hossler 1989; Stewart 2008). Evidently, parental involvement aimed in academic socialization activities had a positive impact on their children’s attainment of milestones towards college, a finding that is consistent with Hill and Tyson’s (2009) meta-analysis of the literature.

At the school level, the model explained 90%Footnote 4 of the variance in attainment of milestones across schools. It accounted for 42% of the variance of parental involvement across schools, while elucidating almost 60% of the aggregate ability of children across schools. In terms of the predictors of school-level of parental involvement, we found support for two out of three hypothesized paths. It is evident that school-based parental involvement is strongly affected by a school aggregate level of SES (0.658, p < .05), while slightly negatively affected by a school-level of student academic ability (− 0.014, p < .05). However, high school academic press exerted no effect on this construct (0.001, p value > 0.05). In relation to attainment of academic readiness for college between schools, we found that our SEM model supported all hypothesized paths. The strongest predictors attainment of milestones across schools were school-level of SES (0.445, p < .05), school-based academic ability (0.408, p < .05) followed by parental involvement (0.202, p < .05). Surprisingly, high school academic press had a negative effect on attainment of milestones across schools; however significant this effect was rather small (− 0.150, p < .05). School-level academic ability, in turn, was strongly affected by school-level SES (0.770, p < .05).

We also examined whether high school academic press exerted a cross-level effect consisting in moderating the impact of parental involvement on attainment of milestones at the family level. Informed by the academic press literature (e.g., Goddard, et al. 2000; Martinez and Klopott 2002; Roney et al. 2007; Smith 2002) and the school-college going culture literature (e.g., Corwin and Tierney 2007; McDonough and Fann 2007), we hypothesized that schools having qualified teachers and counselors would foster an environment whereby parents would be able to secure the cultural and social academic capital needed to become more involved in their children’s education; hence, improving their readiness for college (Savitz-Romer and Bouffard 2014). We found that indeed the effect of parental involvement on attainment of milestones significantly varied across schools (standard deviation = 0.138, p value < .05). However, the cross-level effect of high school academic press was rather trivial (− 0.002), and non significant (p > .05).

Limitations

Our ability of capturing parental and school involvement is rather limited. In their extensive review of the literature, Hill and Tyson (2009) identified three broad categories of parental involvement in education; namely, academic socialization, home-based involvement, and school-based involvement. Our indicators of parental involvement address only one of these categories: academic socialization, a category that involves making preparations for the future (e.g., discussing career plans) and engaging in learning strategies (e.g., discussing preparation for taking college admission tests). It is worth noting, however, that Hill and Tyson reported that across all types of parental involvement, the one reflecting academic socialization had the strongest positive correlation with academic achievement.

While our study captures the active behavioral involvement of parents in the schooling context of their children, we do not have direct measures of different types of familial involvement. For example, our study is unable to capture the influences from and impact of additional family members, such as siblings, grandparents, or other extended family members, who may also play a critical role in students’ schooling experience and academic preparation (George Mwangi 2015). We also acknowledge the important role of race, ethnicity, and gender in college readiness. However, modeling the impact of these in a multilevel SEM context calls for invariance tests, which examines the extent to which the model significantly varies across race, ethnicity or gender (Heck and Thomas 2015). Unfortunately, such tests are beyond the scope of our study and we suggest studying invariance of the model across gender, race, and ethnicity as a recommendation for future research.

Finally, our measures of school involvement are limited in the extent to which we can capture the quality of engagement between the schooling context and the parent. Improved measures may have allowed us to better appraise the construct of academic press. For example, future measures that assess quality of teaching, access to enriched curriculum, the extent and quality of peer interactions, as well as the configuration of courses, could provide us with improved measures for the construct of academic press. Future research may be focused on qualitative studies seeking to capture the nuances of quality in engagement of the school factors and parental factors on the student and their educational experiences.

Discussion

One of the main rationales for our study was to engage in updating extant research on college readiness and the role of parents and schools. Specifically, we wanted to determine if the results of earlier research were replicable using a more recent dataset (HSLS:09) and advanced multilevel SEM procedures. In doing so, replication provides a means to “advance understanding over time of ‘how we know what we know’ in the field of higher education” (Wells et al. 2015, p. 185) Our study demonstrates that parental involvement has a unique and positive impact on a student’s attainment of milestones towards college by 12th grade. It had the largest effect on the attainment of milestones, second only to academic ability. This finding is consistent with the literature in acknowledging the relationship between parental expectations and participation in school activities and academic achievement (e.g., Fan and Chen 2001; Hill and Tyson 2009). Recent results from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) analysis of HSLS:09 data also report that parents continue having the largest influence on high school students’ plans of whether to attend college and their future career (Radford et al. 2018).

Yet, in further building upon the work of social stratification and status attainment research (e.g., Sewell and Shah 1968; Sewell and Hauser 1992), as well as the college choice literature (e.g., Cabrera and LaNasa 2000; Hossler et al. 1989), we advanced a new model postulating the impact of parental involvement on the attainment of milestones, not only within the individual-family context, but also across schools. This model posits that parental involvement has an impact on a student’s attainment of milestones toward college, one that is distinct from those emanating from the family SES, the academic ability of the student, and the school context. Our results indicate that this “college-going” cultural capital producing process also takes place at the school level. School contexts coexist in tandem with factors emerging from the families nested within the schools themselves. A substantial proportion of the variance in the latent factors of family SES, parental involvement, and attainment of milestones is accounted for by the school setting to which a family belongs. Thus, the school context largely mimics the process families undergo in facilitating their children’s attainment of milestones towards college.

At both levels of analysis (school and individual), our results highlight the important role that parental involvement has in fostering readiness for college within families and between the schools the families are nested within. This critical role of parental encouragement justifies the current emphasis in education policy and practice, such as ESSA’s (2015) focus on the involvement of parents and family members in the education of their students. Each of the five parental behaviors considered effective in this study can be used as guides to help parents play more influential roles in their children’s’ college readiness through initiating practices of academic socialization (Hill and Tyson 2009). For example, our findings can be used to inform interventions implemented by schools, college outreach programs such as GEAR UP, and other community organizations that focus on strengthening the connection between the familial home environment and students’ educational experiences. Strengthening these partnerships between schools and families has important implications for the cultivation of cultural capital that percolate in the academic readiness of the student for college.

Furthermore, results of a national survey of high school counselors show that the majority of counselors believe that emphasizing academic socialization (e.g., connecting college and career choices to academic preparation) is important in promoting college readiness (The College Board 2012). And yet only 30% of them report that their schools engage in such activities (The College Board 2012). It is not hard to figure out why this is the case. Several obstacles ranging from extensive administrative demands to caseloads, far exceeding the recommended ratio of 250 cases, prevent counselors from engaging in academic socialization for college (McDonough 2005; Moyer 2011; Paisley and McMahon 2001). Yet, our study suggests that unlocking the power of parental involvement in academic socialization may be a way of multiplying the impact of counseling. Instead of working on individual cases, counselors could be trained to work with families and their communities in how to engage in academic socialization activities. Given that family members are already the main influencers of high school students’ postsecondary and career plans (Radford et al. 2018), counselors would be enabling the families and their communities to activate their existing funds of knowledge (González et al. 2005) to facilitate their children’s readiness for college.

Researchers also cite the importance of high school resources in increasing academic performance (e.g., Phillips 1997) and college access (e.g., Perna 2006). Education policy explicitly aligns with this scholarship and also pushes schools towards greater familial engagement for the improvement of student and school outcomes (ESSA 2015). Yet, our study shows that high school academic press affected neither parental involvement nor readiness for college. There is only one study to date (Lee 2006) that we found supporting the lack of a positive relationship between academic press and applying to college (specifically the probability of taking college admission tests) among a nationally representative sample of high school students (National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988). However in Lee’s (2006) dissertation study, academic press was solely measured as the percentage of teachers with a professional degree. Given our more comprehensive measure of academic press in this study as well as an extensive body literature that would suggest a positive relationship between academic press and college readiness, our results are important for schools and future researchers to note. Perhaps our indicators of school academic press, which rely on the certification of teachers and counselors, are still too distant for capturing the nuanced ways in which a school uses its resources to ensure college access. In this regard, future researchers engaging the concept of academic press need to consider indicators of quality that go beyond having qualified teachers and counselors.

For example, given what is known in college access literature about gatekeeping (Hill Collins 2009; McDonough and Fann 2007), our results align with an important nuance in that school resources do not inherently ensure student access to those resources—particularly if they are not being used effectively or inclusively. How are school resources (e.g., certified teachers and counselors) being distributed to students? Are they only being provided to students on college preparatory tracks? Are there other barriers to students in accessing existing school resources that they need to be college ready? How might the ratios of these certified teachers and counselors to the number of students within a school impact student outcomes for college? While it is beyond the scope of this paper to answer these questions, our results lead us to pose them as areas for future empirical investigation as college readiness must be connected to equity in educational opportunities for students within their schools (McDonough and Fann 2007; Tierney and Auerbach 2005).

Additionally, our results reflect the challenges schools face in fostering familial involvement. Scholars demonstrate a decline in parental engagement with schools as students transition from elementary school into middle school and then high school (Hill and Chao 2009; Spera 2005). According to Hill and Tyson (2009), middle school teachers, in comparison to elementary school teachers, face the challenge of having a larger number of parents with whom to connect. In addition, from the parent perspective, middle school students likely have multiple teachers throughout their day, making it challenging for parents to form relationships with their child’s teachers (Hill and Tyson 2009). It is possible that high school teachers and counselors face similar challenges when trying to interface with parents, which may have led to our results regarding the relationship between academic press and parental involvement. We suggest future research continues to investigate how schools engage parents and the factors that increase parental involvement in schools. Given federal legislation such as ESSA (2015) mandating the need for empirically-proven practices for familial engagement, this focus will continue to be a priority within the U.S. educational policy agenda into the future.

Notes

To meet IES’s disclosure policies in the use of restricted databases, we only report overall estimates of the sample size and number of schools.

The configural model consists of constraining the factor loadings to be the same within families and across schools, and contrasting this model against an unconstrained model. The Muthén-Satorra’s MLR test of difference in χ2 is recommended in conducting this test (Heck and Thomas 2015).

According to Heck (R. Heck, personal communication, August 17, 2017) finding more variance explained at level-2 than in level-1 is not surprising. Mplus standardizes the variance at each level, which leads to higher R2 s between groups than it does within groups. Variability also plays a role. The R2 s in level-1 are based on about 19,000 individuals, while R2 s in level-2 are based on about 900 schools.

References

ACT. (2004). Crisis at the core: Preparing all students for college & work. Iowa City, IA: ACT.

Adelman, C. (1999). Answers in the tool box. Academic intensity, attendance patterns, and bachelor’s degree attainment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Alexander, K. L., & Entwisle, D. R. (1996). Schools and children at risk. In A. Booth & J. F. Dunn (Eds.), Family-school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? (pp. 67–88). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Arnold, K. D., Liu, E. C. & Armstrong, K. J. (2012). The ecology of college readiness. ASHE Higher Education Report, Vol. 38, No. 5. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Auerbach, S. (2004). Engaging Latino parents in supporting college pathways: Lessons from a college access program. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 3(2), 125–145.

Bergerson, A. (2009). College choice & access to college: Moving policies, research, & practice to the 21st century. ASHE Higher Education Report, Vol. 35, No. 4. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Berkner, L., Chavez, L., & Carroll, C. D. (1997). Access to postsecondary education for the 1992 high school graduates. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge.

Cabrera, A. F., Burkum, K. R., & LaNasa, S. (2005). Pathways to a four-year degree: Determinants of transfer and degree completion. In A. Seidman (Ed.), College student retention: A formula for student success (pp. 155–209). Westport, CT: ACE/Praeger.

Cabrera, A. F. & LaNasa, S. (2000). Understanding the college choice of disadvantaged students. New Directions for Institutional Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cabrera, A. F., Prabhu, R., Deil-Amen, R., Terenzini, P. T., Lee, C., & Franklin, R. F., Jr. (2006). Increasing the college preparedness of at-risk students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 5(2), 79–97.

Calcagno, J. C., Crosta, P., Bailey, T., & Jenkins, D. (2007). Stepping stones to a degree: The impact of enrollment pathways and milestones on community college student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 775–801.

Cooper, C., Chavira, G., & Mena, D. (2005). From pipelines to partnerships: A synthesis of research on how diverse families, schools and communities support children’s pathways through school. Journal of Education for Students Placed At Risk, 10(4), 407–430.

Corwin, Z. B., & Tierney, W. G. (2007). Getting there—and beyond: Building a culture of college going in high schools. Los Angeles: Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8, 1.

Eagle, E. (1989). Socioeconomic status, family structure, and parental involvement: The correlates of achievement. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1993). Parent-school involvement during the early adolescent years. Teachers College Record, 94, 568.

Enders, C. G. (2013). Analyzing structural equation modeling with missing data. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Muller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 439–493). North Carolina, Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Engberg, M. E., & Gilbert, A. (2014). The counseling opportunity structure: Examining correlates of four-year college going rates. Research in Higher Education, 55(3), 219–244.

Engberg, M. E., & Wolniak, G. C. (2010). Examining the effects of high school contexts on postsecondary enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 51(2), 132–153.

Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015. (2015–2016). P.L. 114-95 § 114, Stat. 1177.

Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–22.

Fan, W., & Williams, C. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74.

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2013). Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hanckock & R. O. Muller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: Second course (2nd ed., pp. 439–493). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Fordham, S. (1996). Blacked out: Dilemmas of race, identity, and success at Capital High. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

George Mwangi, C. A. (2015). (Re)Examining the role of family and community in college access and choice: A metasynthesis. The Review of Higher Education, 39(1), 123–151.

Gibbons, M. M., & Borders, L. D. (2010). Prospective first-generation college students: A social-cognitive perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 58(3), 194–208.

Goddard, R. D., Sweetland, S. R., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). Academic emphasis of urban elementary schools and student achievement in reading and mathematics: A multilevel analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36(5), 683–702.

Goldring, E. B., & Phillips, K. J. (2008). Parent preferences and parent choices: The public–private decision about school choice. Journal of Education Policy, 23(3), 209–230.

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Grodsky, E., & Riegle-Crumb, C. (2010). Those who choose and those who don’t: Social background and college orientation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627(1), 14–35.

Hamilton, L. S., Stecher, B. M., & Yuan, K. (2008). Standards-based reform in the United States: History, research, and future directions. Washington, DC: Rand Corporation.

Hancock, G. R., & Mueller, R. O. (2001). Rethinking construct reliability within latent variable systems. In R. Cudeck, S. Du Toit, & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: Present and future- A Festschrift of Karl Jöreskog (pp. 195–216). Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Heck, R. H., & Thomas, S. L. (2015). An introduction to multilevel modeling techniques: MLM and SEM approaches using Mplus. New York: Routledge.

Heeringa, S. G., West, B. T., & Berglund, P. A. (2010). Applied survey data analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Hill, N., & Tyson, D. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytical assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 740–763.

Hill, N. E., & Chao, R. K. (2009). Families, schools, and the adolescent: Connecting research, policy, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hill Collins, P. (2009). Another kind of public education: Race, school, the media, and democratic possibilities. Boston: Beacon Press.

Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2010). Involving low-income parents and parents of color in college readiness activities: An exploratory study. Professional School Counseling, 14(1), 115–124.

Holland, N. E. (2010). Postsecondary education preparation of traditionally underrepresented college students: A social capital perspective. Journal Of Diversity In Higher Education, 3(2), 111–125.

Hossler, D., Braxton, J., & Coopersmith, G. (1989). Understanding student college choice. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 5, pp. 231–288). New York: Agathon Press.

Hossler, D., Schmidt, J., & Bouse, G. (1991). Family knowledge of postsecondary costs and financial aid. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 21(1), 4–17.

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & de Shoot, R. (2018). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–15.

Ingels, S. J., Pratt, D. J., Herget, D. R., Burns, L. J., Dever, J. A., Ottem, R., Rogers, J. E., Jin, Y., & Leinwand, S. (2011). High school longitudinal study of 2009 (HSLS:09). Base-year data file documentation (NCES 2011-328). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Jaeger, M. M. (2011). Does cultural capital really affect academic achievement? New evidence from combined sibling and panel data. Sociology of Education, 84(4), 281–298.

Kaplan, L. S., & Owings, W. A. (2001). Teacher quality and student achievement: Recommendations for principals. NASSP Bulletin, 85, 628.

Lee, C. (2006). Academic readiness and taking of college admission tests. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

Lee, V., & Burkam, D. (2002). Inequality at the starting gate: Social background differences in achievement as children begin school. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Lee, V. E., Smith, J. B., & Croninger, R. G. (1997). How high school organization influences the equitable distribution of learning in mathematics and science. Sociology of Education, 70(2), 128–150.

Leppel, K., Williams, M. L., & Waldauer, C. (2001). The impact of parental occupation and socioeconomic status on choice of college major. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22(4), 373–394.

Lieber, C. M. (2009). Increasing college access through school-based models of postsecondary preparation, planning, & support. Cambridge, MA: Educators for Social Responsibility.

Ma, Y. (2009). Family socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and college major choices-gender, race/ethnic, and nativity patterns. Sociological Perspectives, 52(2), 211–234.

Marsh, H., Lüdtke, O., Nagengast, B., Trautwein, U., Morin, A., Abduljabbar, A., et al. (2012). Classroom climate and contextual effects: Conceptual and methodological issues in the evaluation of group-level effects. Educational Psychologist, 47, 106–124.

Martinez, M., & Klopott, S. (2002). How is school reform tied to increasing college access and success for low-income and minority youth?. Washington, DC: Pathways to College Network.

Martinez, M., & Klopott, S. (2005). The link between high school reform & college access & success for low-income & minority youth. Washington, DC: AYPF.

McCarron, G. P., & Inkelas, K. K. (2006). The gap between educational aspirations and attainment for first-generation college students and the role of parental involvement. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 534–549.

McClafferty, K. A., McDonough, P. M., & Nunez, A. (2002, April). What is a college culture? Facilitating college preparation through organizational change. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

McDonough, P. (2005). Counseling matters: Knowledge, assistance, organizational commitment in college preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. B. Corwin, & J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach (pp. 69–87). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

McDonough, P. M. (1997). Choosing colleges: How social class and schools structure opportunity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

McDonough, P. M., & Calderone, S. (2006). The meaning of money: Perceptual differences between college counselors and low-income families about college costs and financial aid. American Behavioral Scientist, 12, 1703–1718.

McDonough, P. M., & Fann, A. (2007). The study of inequality. In P. Gumport (Ed.), Sociology of higher education: Contributions and their contexts (pp. 53–93). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press.

Moyer, M. (2011). Effects of non-guidance activities, supervision, and student-to-counselor ratios on school counselor burnout. Journal of School Counseling, 9(5), 1–31.

Muthén, L. & Muthén, B. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. (2002). P.L. 107-110, 20 U.S.C. § 6319.

Odden, A., & Odden, E. (1995). Educational leadership for America’s schools. New York: McGraw Hill.

Oseguera, L. (2013). Importance of high school conditions for college access. Los Angeles, CA: UC Accord and Pathways to Postsecondary Success.

Paisley, P. O., & McMahon, G. (2001). School counseling for the 21st century: Challenges and opportunities. Professional School Counseling, 5(2), 106–116.

Pascarella, E. (2006). How college affects students: Ten directions for future research. Journal of College Student Development, 47(5), 508–520.

Patel, N., & Stevens, S. (2010). Parent-teacher-student discrepancies in academic ability beliefs: Influences on parent involvement. School Community Journal, 20(2), 115–136.

Perna, L. W. (2005). The key to college access: Rigorous academic preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. B. Corwin, & J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach (pp. 113–134). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Perna, L. W. (2006). Studying college choice: A proposed conceptual model. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 21, pp. 99–157). New York: Agathon Press.

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. A. (2005). The relationship between parental involvement as social capital and college enrollment: An examination of racial/ethnic group differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 485–518.

Perry, L. B., & McConney, A. (2010). Does the SES of the school matter? An examination of socioeconomic status and student achievement using PISA 2003. Teachers College Record, 112(4), 1137–1162.

Phillips, M. (1997). What makes schools effective? A comparison of the relationships of communitarian climate and academic climate to mathematics achievement and attendance during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 34(4), 633–662.

Radford, A. W., Fritch, L. B., Leu, K., and Duprey, M. (2018). High school longitudinal study of 2009 (HSLS:09) second follow-up: A first look at fall 2009 ninth-graders in 2016 (NCES 2018-139). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: NCES.

Raykov, T. (1997). Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Applied Psychological Measurement, 21, 173–184.

Raykov, T. (2009). Evaluation of scale reliability for unidimensional measures using latent variable modeling. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 42(3), 223–232.

Reyes, L. H., & Stanic, G. M. (1988). Race, sex, socioeconomic status, and mathematics. Journal for research in mathematics education, 19, 26–43.

Rohde, T. E., & Thompson, L. A. (2007). Predicting academic achievement with cognitive ability. Intelligence, 35(1), 83–92.

Roney, K., Coleman, H., & Schlichting, K. A. (2007). Linking the organizational health of middle grades schools to student achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 91(4), 289–321.

Ross, T. (2016). The differential effects of parental involvement on high school completion and postsecondary attendance. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24, 30.

Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., Bell, A. D., & Perna, L. W. (2008). Contextual influences on parental involvement in college going: Variations by socioeconomic class. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 564–586.

Rumberger, R. W. (1995). Dropping out of middle school: A multilevel analysis of students and schools. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 583–625.

Savitz-Romer, M., & Bouffard, S. M. (2014). Ready, willing and able: A developmental approach to college access and success. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Schneider, M., Marschall, M., Teske, P., & Roch, C. (1998). School choice and culture wars in the classroom: What different parents seek from education. Social Science Quarterly, 79(3), 489–501.

Schreiber, J. B., Stage, F. K., King, J., Nora, A., & Barlow, E. A. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–337.

Sewell, W. H., & Hauser, R. M. (1992). A review of the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study of Social and Psychological Factors in Aspirations and Achievements 1963–1993. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Sewell, W. H., Hauser, R. M., & Wolf, W. C. (1980). Sex, schooling, and occupational status. American Journal of Sociology, 86, 551–583.

Sewell, W. H., & Shah, V. P. (1968). Social class, parental encouragement, and educational aspirations. American Journal of Sociology, 73(5), 559–572.

Sharkness, J., & DeAngelo, L. (2011). Measuring student involvement: A comparison of classical test theory and item response theory in the construction of scales from student surveys. Research in Higher Education, 52, 480–507.

Shouse, R. C. (1996). Academic press and sense of community: Conflict, congruence, and implications for student achievement. Social Psychology in Education, 1, 47–68.

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453.

Smith, P. A. (2002). The organizational health of high schools and student proficiency in mathematics. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 98–104.

Spera, C. (2005). A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 125–146.

Stage, F. K., & Hossler, D. (1989). Differences in family influences on college attendance plans for male and female ninth graders. Research in Higher Education, 30(3), 301–315.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1995). Social capital and the reproduction of inequality: Information networks among Mexican-origin high school students. Sociology of Education, 68, 116–135.

Stapleton, L. M. (2013). Multilevel structural equation modeling with complex sample data. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Muller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 521–562). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Stapleton, L. M., Yang, J. S., & Hancock, G. R. (2016). Construct meaning in multilevel settings. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 41(5), 481–520.

Stewart, E. B. (2008). School structural characteristics, student effort, peer associations, and parental involvement the influence of school-and individual-level factors on academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 40(2), 179–204.

The College Board. (2012). The College Board 2012 National Survey of School Counselors and Administrators report on survey findings: Barriers and supports to school counselor success. Washington, DC: The College Board.

Thomas, S. L., & Heck, R. H. (2001). Analysis of large-scale secondary data in higher education research: Potential perils associated with complex sampling designs. Research in Higher Education, 42(5), 517–540.

Tierney, W. G., & Auerbach, S. (2005). Toward developing an untapped resource: The role of families in college preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. B. Corwin, & J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach (pp. 29–48). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Viteritti, J. P. (2012). The federal role in school reform: Obama’s Race to the Top. Notre Dame Law Review, 87(5), 2087–2121.

Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling. Applications using Mplus. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Wells, R., Kolek, E. A., Williams, E., & Saunders, D. B. (2015). “How we know what we know”: A systematic comparison of research methods employed in higher education journals, 1996–2000 v. 2006–2010. Journal of Higher Education, 86(2), 171–198.

Wells, R. S., & Lynch, C. M. (2012). Delayed college entry and the socioeconomic gap: Examining the roles of student plans, family income, parental education, and parental occupation. Journal of Higher Education, 83(5), 671–697.

White, K. R. (1982). The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3), 461.

Wiley, A., Wyatt, J., & Camara, W. J. (2011). The development of a multidimensional college readiness index. College Board Research Report 2013-3. Retrieved from: https://research.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/publications/2012/7/researchreport-2010-3-development-multidimensional-college-readiness-index.pdf.

Acknowledgements

Our special thanks go to Ronald H. Heck, Professor of Educational Administration at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa. Ron graciously dedicated considerable time assisting us in unlocking the incredible potential multilevel structural equation modeling has in examining the impact of school and family contexts. We also thank the Research in Higher Education reviewers of this article whose feedback on earlier drafts improved our final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

George Mwangi, C.A., Cabrera, A.F. & Kurban, E.R. Connecting School and Home: Examining Parental and School Involvement in Readiness for College Through Multilevel SEM. Res High Educ 60, 553–575 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9520-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9520-4