Abstract

Expanding the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian (hereafter respectfully Indigenous) talent pool to undertake valuable roles in business, health, education, academia, government, policy development and community development is critical for addressing current disparities between Indigenous and other Australians. Parity of access and engagement with education plays a key role in facilitating participation in these roles but has not yet been attained. This article provides an initial systematic review of literature on the state of the evidence regarding access/attraction, retention and completions for Indigenous Higher Degree Research (HDR) students. This article identifies the quantity (number examined), nature (e.g. focus of study), quality (peer reviewed and evidence of methodological rigour) and characteristics (e.g. publication type, authorship) of the limited publications. Using specific search strings (words or phrases of relevance to the topic), a systematic review methodology was employed to search nine databases and grey (non-peer reviewed) literature from 1995 to 2015. The resultant 12 publications were mined with quality assessed and a predetermined framework used to extract and synthesise the characteristics from individual publications. This research contributes to existing literature about Indigenous Peoples in HDR programs internationally in identifying significant cultural and institutional barriers and highlighting institutional enablers which can contribute to attraction, retention and completion. Building on the prior limited research reported in the review, the article highlights the need for further research and provides an initial agenda of directions for universities and government to redress the disparity in entry and completion of Indigenous Peoples in HDR programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Education shapes people’s life pathways and opportunities to participate in social, cultural and economic experiences and contributes to individual and collective health and wellbeing and overall quality of life (SCRGSP 2014; White and Wood 2009; Zubrick et al. 2006). Fostering nurturing environments for higher education student success is critical for expanding the capacity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter respectfully Indigenous) PeoplesFootnote 1 to undertake valuable roles in academia, government, policy development and communityFootnote 2 development initiatives (Australian Government 2011). As such, participation in higher education plays a vital role in improving the overall positioning of Indigenous communities in Australia. Increased capacity contributes to raising social, health and economic prosperity for Indigenous Peoples.

In 2015–2016 there were a number of reviews into research in Australian universities which resulted in a range of recommendations; some of which had implications for Indigenous Peoples’ higher education opportunities. The National Science and Innovation Agenda (NSIA) aimed to strengthen Australia’s research system, encourage collaboration between universities and businesses and better translate research outcomes into economic and social benefits (Birmingham 2016). The Watt Review was commissioned to review research policy and funding arrangements with the broad aim to ensure quality and excellence of Australian university research and research training (DET 2015) and set out 28 recommendations to build on the NSIA (Birmingham 2016). The Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA) was tasked with reviewing Australia’s research training system (see ACOLA 2016). The new Research Training Program will allow universities to increase higher degree research (HDR) stipends and following an ACOLA recommendation, the government decided to double the weighting given to Indigenous HDR completions in calculating scholarship allocations (Ross 2016). Supporters suggest that the changes will help universities attract HDR students, particularly from Indigenous communities (Ross 2016). The earlier Review of Higher Education Access and Outcomes for Indigenous People, chaired by Professor Larissa Behrendt in 2012, highlighted the role that higher education plays in improving health, education and economic outcomes for Indigenous peoples and examined the role of higher education in closing the gap and reducing Indigenous disadvantage (DET 2017).

However, deriving the benefits of education requires equity of access and participation and engagement with learning (Zubrick et al. 2006). Only 5% of Indigenous Australians hold a Bachelors degree or above (AHRC 2017) and like Indigenous Peoples in countries including Aotearoa/New Zealand (see Barnhardt 2002, cited in Schofield et al. 2013), Canada (see Childs et al. 2016), and the United States (see Cabrera et al. 1999, cited in Wilson et al. 2011), are affected by a range of factors which mean that they are less likely than non-Indigenous Peoples to graduate after commencing university. Though comprising 3% of the total Australian population, Indigenous Australians are underrepresented in HDR programs at just over 1% of HDR cohorts (Behrendt et al. 2012). There is an upward trend for Indigenous HDR students. Fifty-five Indigenous Australians were awarded PhDs from 1990 to 2000; this figure rose to 219 from 2000 to 2011 (Bock 2016—a quadruple increase. These numbers are still a long way from benchmark parity with the non-Indigenous population. The younger profile of Indigenous Australians—the median age of Indigenous Australians is 22 years compared to the overall Australian population of 38 (ABS 2011)—provides fertile ground for the expansion of young people’s educational opportunities but there must be appropriate support and development through schooling and undergraduate studies and on to completion of HDR programs.

In this article, we systematically investigated the prevailing literature about attraction, retention and completion for Indigenous HDR students. In the context of government, societal and university calls to increase the number of Indigenous Peoples commencing and completing HDR programs, the thorough and systematic literature review identified that we need to know more about Indigenous HDR students’ experiences relative to other student cohorts in Australia and internationally and that there is actually very limited research which has examined the factors which impact on attraction into, and completion of, HDR studies. The review aimed to: (1) ascertain the quantity, nature and quality of relevant published documentation across time (1995–2015); and (2) improve the evidence-base to increase the participation of Indigenous HDR students by identifying and synthesising enablers of HDR attraction, retention and completion. We first present a summary of Indigenous methodologies and our position as researchers, and then provide a brief overview of the issues affecting Indigenous Peoples in higher education in Australia and internationally. We then address the first purpose of this article, which is to provide a thorough overview of the extant research which highlights a complex mix of individual and cultural and institutional factors which determine attraction and completion. The overall implications of the findings from the limited research in this area leads to our second purpose of the article, namely, that there is need for development of new support initiatives for Indigenous HDR students to better inform students, academics and policy makers about factors assisting Indigenous Peoples to commence and complete HDR programs. In so doing it is expected that there will be response to education being a priority area in the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2011–2018. In providing suggestions about what we need to undertake in future research and outlining an initial agenda for directions for universities and government, the review provides a platform from which action plans for Indigenous HDR support can be developed across Australian universities; which should include analysis of successful Indigenous HDR outcomes and identification of gaps between theory and practice.

Indigenous Research Methodologies and Us as Researchers

Within the international literature on Indigenous methodologies, Kovach (2015, p. 46) summarised “As Indigenous methodologies have emerged within the mainstream research discourse, awareness of its epistemological distinctiveness, alongside what this means for research design and interpretation, has been challenging for both friend and foe. It is with an awareness of the assimilating force of dominant discourse that exists within sites of formal education that…speaks to the nature and promise of Indigenous methodologies”. Kovach (2015, p. 54) highlighted four central aspects of Indigenous methodologies as follows: “holistic Indigenous knowledge systems are a legitimate way of knowing; receptivity and relationship between researcher and participants is (or ought to be) a natural part of the research methodology; collectivity, as a way of knowing, assumes reciprocity to the community; Indigenous methods, including story, are a legitimate way of sharing knowledge”. Battiste (2013) suggested that education systems do not accommodate the heritage, knowledge or culture that students bring to education in not be reflective of the everyday they share with their families; only an imagined and aspirational ‘other’. Moreover, Smith (2012) emphasised the need to do more than deconstruct Western scholarship but to understand the ways in which Indigenous Peoples can ask and seek answers to their own concerns within a context in which resistance to new formations of colonisation is articulated and decolonisation of research methods helps to reclaim Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

Specifically in the Australian Indigenous context, Rigney (1999) emphasised three fundamental and related principles of Indigenist research namely: resistance as the emancipatory imperative (supporting personal, community, cultural and political struggles of Indigenous Australians in healing from past oppressions and achieving cultural freedom in the future), political integrity (the provision of a social link between research and the political struggle of Indigenous communities), and privileging Indigenous voices (whose goals are to serve and inform the Indigenous struggles for self-determination). Nakata (cited in Nakata et al. (2014) has explained that Indigenous scholarly enquiry is said to emerge at the [cultural] interface of: Indigenous Peoples’ traditional and contemporary knowledge, experience and analytical standpoints; the representation of these as historically constructed by Western disciplines and the knowledge methods and practice of Western disciplines that impact on Indigenous lives and shape Indigenous options. Nakata (2010) stresses the case to include traditional Indigenous knowledge as not less formal or less valued than scientific knowledge, and that traditional and contemporary knowledge both need to be privileged in the appropriate context for appropriate purposes. Nakata (cited in McGlion 2009) said that Indigenous studies have been a study of, and about, Indigenous Peoples. We acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples remain the subjects of study within Western institutions and by non-Indigenous Peoples and thus an important aspect of the publications we discuss within this article is that the majority included Indigenous researchers and that this small but growing area of research is privileging Indigenous voices. Moreover, we now make transparent the background, training and position we, as researchers, bring to undertaking this Indigenous research.

This review article was prompted by the authors’ concerns about the low rates of attraction, retention and completion and limited specific support for Indigenous HDR students in Australian universities. The research for this article was undertaken by an inter-disciplinary team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers who have extensive experience researching and teaching in universities. The research was done through mutual learning and with an emphasis on capacity building in developing research skills of junior Indigenous researchers and the cultural knowledge of the non-Indigenous researcher.

Educated in Western sandstone institutions, and a career academic, who is internationally-recognised for her research in human resource management and cross-cultural management, the non-Indigenous first author has worked in a range of intercultural research teams and across a wide range of countries internationally. A strong focus in her work life has been sharing knowledge and examining different ways of working. Though embracing a qualitative and narrative approach to research throughout her career, she came to Indigenous research as a journey of new learning. The second author is an Aboriginal Australian woman with a strong commitment to improving the health and prosperity of Indigenous nations through research. As director of a Centre for Indigenous Health Equity Research at a university, she well understands what educational opportunities offer Indigenous nations and the challenges faced in terms of access and success in tertiary institutions. The third author is an Aboriginal woman whose journey typically reflects those impacted by the Stolen Generation. Since completing a mainstream Western doctorate she has developed a strong reputation for her involvement in developing pathways for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students from education to employment. She pioneered the development of the first Indigenous business course that accredits students with the ability to work with First Australians. Her successful research projects have led to her current role as lead investigator for a nationally-awarded grant investigating ways to enhance Indigenous businesses through improved financial literacy. The fourth author has deep insights into Indigenous higher education and the barriers facing the development of an Indigenous research workforce. He has held senior academic and executive roles in five higher education institutions and has actively developed strategies and implemented policies to increase Indigenous research students. He is currently negotiating a multi-institutional research capacity building program with six universities in an attempt to address the barriers to retaining Indigenous research students.

Higher Education and Indigenous Peoples

Following extensive reforms in education in the university sector since the late 1980s, there was a significant increase in the number of students enrolled at universities including international students and domestic (Australian citizen/permanent resident) school leavers (those who move straight from secondary school to university studies). Increasing university and government attention is focused on how to retain students after they have enrolled; increase the diversity of the student cohort; and develop success strategies, especially for students from under-represented groups, lower socio-economic backgrounds and those who are the first in their immediate family to attend university. The increasingly diverse student cohort has meant that significant attention has been devoted to addressing specific students’ needs including part-time and online students, people with disabilities, and gender diversity.

Research has examined issues specifically affecting enrolment into, and completion of, undergraduate university degrees for Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 3 This has included negative perceptions of higher education within communities (Cameron and Robinson 2014). Such negative perceptions can arise from: lack of belief in the value of such for gaining (better) employment or providing value back to the community; and/or negative experiences of being researched; and/or despite initiatives within higher education to improve Indigenous Peoples’ learning, lack of cultural safety. Another factor affecting opportunities to enrol for some individuals is low socio-economic status (Schofield et al. 2013). Moreover, Kippen et al. (2006) mentioned a range of other factors which could impact on Indigenous Peoples’ enrolment (and potentially completion after enrolment) as including: past educational experiences, lack of Indigenous role models, lack of information about university, and living in rural/remote locations distant from universities. Further issues experienced within universities include: racism, discrimination, and exclusionary practices within universities as well as negative attitudes of non-Indigenous students (Farrington et al. 1999); and inflexibility of academic requirements with respect to insufficient cultural content in curriculum (Cameron and Robinson 2014). Prior research has also highlighted facilitators as including: university departments/centres for Indigenous student support (Cameron and Robinson 2014); university support strategies to address racism/discrimination (Farrington et al. 1999); other university support services (Miller 2005); financial assistance from universities and government (Cameron and Robinson 2014; Miller 2005); flexibility in course design/delivery (Miller 2005); cultural safety within universities (Kippen et al. 2006); and family having interest in, and providing support for, university attendance and study (Cameron and Robinson 2014).

Reporting on the United Kingdom, McCulloch and Thomas (2013), suggested that there has been a tendency of higher education institutions to approach widening participation of the student cohort at a doctoral level as an extension of the undergraduate level, but they argue that doctoral education is sufficiently different to warrant a distinct approach and research agenda with focus beyond access and transition through the exploration of the broader research degree and post-doctoral experience. We concur with this position and in particular, as demonstrated throughout this review, highlight that HDR studies have a new set of particular challenges for Indigenous Peoples, most especially, doing research in Western institutions which may not be supportive of Indigenous methodologies or ways of approaching research and resistance by potential research participants when researching Indigenous issues. Moreover, Indigenous HDR students may experience difficulties when working one-on-one with non-Indigenous academics who may have insufficient Indigenous cultural or methodological knowledge or Indigenous academics who may face considerable time pressures and issues with cultural safety of their own.

Like the experience for Indigenous Peoples in some other colonised countries, Indigenous Australian HDR students are positioned differently to undergraduates in university systems. Thus, in providing an initial systematic literature review of factors affecting attraction and completion of Indigenous Australian HDR students, this article contributes to a broader literature examining entry into, and experiences within, doctoral programs for Indigenous Peoples internationally, most notably Aotearoa/New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Prior international research has suggested Indigenous Peoples in doctoral programs internationally encounter racism and discrimination (which can be manifest as being identified as being different from others, experiencing the shortcomings of negative stereotypes and assumptions, and sensing alienation from others) (Ballew 1996), additional cultural and personal demands for family and community while working on theses (McKinley et al. 2011), issues with supervision including insufficient methodological or cultural knowledge of Indigenous supervisorsFootnote 4 (Grant and McKinley 2011); and challenges stemming from university/institutional deficits in cultural/social aptitude (Bancroft 2013). The current research also reinforces international literature noting both individual/cultural (family involvement and support, doctoral candidates’ reconciling their own identity within the institution) and institutional (e.g. university engagement with communities, supervisor knowledge and training) factors as success facilitators for Indigenous Peoples in doctoral programs globally (see Elliott 2010; Hutchinson et al. 2008; McKinley et al. 2011; Wisker and Robinson 2012).

Systematic Literature Review—Aim and Objectives

The overarching aim of the review was to: report on the state of evidence about the characteristics, including enablers and barriers, in the attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students. In the review, we critically appraised publications by:

-

taking account of the quantity of publications;

-

cataloguing publications according to nature/type;

-

mapping changes in publication outputs across the specified timeframe;

-

assessing the quality of publications; and

-

identifying the characteristics of the facilitating strategies and constraints in attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students.

Systematic Literature Review—Methods

The methodological approaches of Campbell and Cochrane Collaborations and Sanson-Fisher et al. (2006) informed the design of this systematic review. It also aligned with the approach of our previous reviews - see Bainbridge et al. (2014). Peer-reviewed and grey (non-peer reviewed) literature (e.g. media articles) over the past two decades (1995–2015) were systematically searched and appraised. The start date coincided with historical points in time where the numbers of Indigenous enrolments and HDR students started to increase and covered the period leading into the establishment of Indigenous development and support in many universities.

Review Strategy

A four-step systematic review method was adopted and is described in detail below.

Step 1: Searching the Evidence Base

A desktop canvassing of the literature was undertaken. The systematic literature review was undertaken using electronic databases with additional searching through Google/Google Scholar; and websites of researchers who had authored papers in the database search. The first 100 returns of each, as per the Campbell Collaboration protocol for relevance and practicality (Personal Communication, Campbell Collaboration 2012) were included in the review. Reference lists of the final search documents were also probed. Nine databases were searched:

-

AEI (Australian Education Index) (ProQuest Dialog);

-

Australian Public Affairs Full Text (APAFT);

-

Econlit (Ovid);

-

ERIC (Education Resources Information Centre) (CSA);

-

IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences) (CSA);

-

PsycINFO (ProQuest Dialog);

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (WoK);

-

Social Services Abstracts (CSA); and

-

Sociological Abstracts (CSA).

An iterative quality improvement approach was adopted in the development of the search terms to ensure we cast as wide-a-net as possible in canvassing the literature sources. In doing so, the results from original searches were scanned and search terms refined. The search terms used for the final canvassing of the literature were:

-

Aborig* OR “Torres Strait Islander” OR indig*

-

AND Australia*

-

AND “post graduate” OR PhD OR HDR OR “higher degree” OR “doctoral candidate” OR doctoral

-

AND barrier* OR enabler* OR success OR entry OR commenc* OR attraction OR recruitment OR retention OR completion OR improv*

-

NOT Canad* OR child*

Step 2: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria developed at the search outset were applied to the retrieved documents. Publications were included if:

-

they were published between January 1995 and December 2015;

-

the key search terms are located in the title or abstract;

-

they are available in English; and

-

they explicitly identify Indigenous HDR students as their key focus.

Publications were excluded where Indigenous HDR student attraction, retention and completion processes or the effects of specific HDR processes could not be separated from other innovations.

Step 3: Classification of Publications

The application of inclusion/exclusion criteria obtained a total of 12 publications for review. Sanson-Fisher et al. (2006) suggests the extent to which the best evidence can be used to guide development in a field is dependent on the quantity and quality of available evidence. Moreover, the quantity of measurement, descriptive and intervention research publications across time indicates whether research efforts have moved beyond describing the issue to providing data about how to facilitate positive change. Following this rationale, a phased approach to classifying individual publications was then implemented:

Phase 1 Publications were grouped according to type under the classifications of (1) original research: data based; (2) reviews: summaries or critical reviews; (3) program descriptions; (4) discussion papers and commentaries: general articles on Indigenous HDR students, and recommendations of task forces or committees; and (5) case reports (Sanson-Fisher et al. 2006).

Phase 2 All original research publications were then classified under three categories: descriptive; measurement and intervention research:

-

Measurement research included publications developing or testing a measure of attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students.

-

Descriptive research included publications where the key aim was to explore and describe issues, processes/models or attributes related to the attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous Australian HDR students.

-

Intervention research included publications in which the aim was to test the effectiveness of any innovation/intervention implemented to improve the attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students (Sanson-Fisher et al. 2006).

Phase 3 Twelve (12/79 or 15.2%) publications were identified for full-text review. A subset of 20 publications (20/79 or 25.3%) was assessed by one of the researchers at a different institution to verify inclusion and classification of publications selected by the first researcher. There was initially 60% agreement between the first and second researcher. However, full consensus was reached in negotiations between the two authors for the final decision of 12 included publications.

Phase 4 Quality was determined using two indicators: (1) methodological quality; and (2) peer-review. The methodological approach by which research evidence is generated is seen as an indicator of quality. Peer-review increases the probability of quality (Sanson-Fisher et al. 2006), and as such this was used as a benchmark for determining quality.

Step 4: Mining the Data

The characteristics and outcomes of all publications were identified by conceptually mining the 12 resulting publications according to a predetermined framework. Documents were hand-searched to identify the framework elements. These included: author and publication year; Indigenous authorship/author leadership; publication type; focus of publication; methods; publication classification; quality of the design for original research publications only; facilitating environments; constraints; strategies; and outcomes. Facilitating environments were enablers operating in the attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students, and constraints were the reverse of such. Strategies included the mechanisms facilitating the successful attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students, and outcomes pertained to any outcomes or consequences subsequential to Indigenous HDR student experiences.

Systematic Literature Review—Results

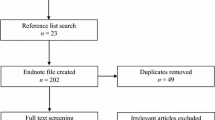

Figure 1 is a PRISMA flow chart (Moher et al. 2009) showing how the total number of publications identified was reduced to the final 12 included publications.

Flow diagram of search strategy (Moher et al. 2009)

Quantity, Nature and Quality of Identified Publications

Number of Publications

As shown in Fig. 1, 79 articles were found through database searching with 14 articles identified through additional sources. Additional sources included Google/Google Scholar (using similar search terms). Names of primary authors identified in the database were also searched. There were 93 records in total. Five duplicates were excluded; resulting in 88 records being screened. Of these, 66 records were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were on topics including Indigenous People in other countries, Indigenous Australian primary and high school and undergraduate students, Indigenous Australian community, health and literacy issues, and some medical/science/social sciences papers on unrelated populations. Thus, 22 full-text articles were accessed. Ten full-text documents were excluded from the additional sources—one was a newspaper report, one was focused on intercultural doctoral research and included limited reference to Indigenous HDR students, and eight others made reference to HDR students but were primarily about undergraduate/postgraduate coursework students or doing academic (not specifically HDR) research. The full-text of each of 12 resulting articles was downloaded and organised into a folder split by database name. In addition, each citation was imported into an Endnote library with its corresponding full-text added as an attachment to each entry. In the final analysis, 12 studies were examined (Barney 2013; Behrendt et al. 2012; Chirgwin 2014; Day 2007; Elston et al. 2013; Harrison et al. 2017; Laycock et al. 2009; Schofield et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014).

There were no publications identified from 1995 to 2007; or 2008 or 2010. From 2007 they increased (only 1 publication) and decreased sporadically (2 publications in each of 2009, 2011 and 2012) until 2013; at which point they peaked (4 publications). Publications decreased again for 2014 (2 publications) and 2015 (only 1 publication). The rapid increase to four publications in 2013 might have been motivated by the release of the Behrendt Report in 2012.

Classification of Publications

The twelve identified publications (See Table 1) included peer-reviewed journal articles [n = 9] (Barney 2013; Chirgwin 2014; Day 2007; Elston et al. 2013; Harrison et al. 2017; Schofield et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2011, 2014); book chapters [n = 1] (Trudgett 2013); and reports [n = 2] (Behrendt et al. 2012; Laycock et al. 2009). Ten of 12 (83.3%) publications were classified as original research. Original research publications were then categorised as descriptive [n = 10] (Barney 2013; Behrendt et al. 2012; Chirgwin 2014; Elston et al. 2013; Harrison et al. 2017; Laycock et al. 2009; Trudgett 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014), measurement (n = 0) and intervention research (n = 0).

Quality of Publications

All the included publications were deemed to be of quality given that they had been peer reviewed (journal articles) or included in a book by an established international publisher (book chapter) or involved a national government-initiated review or conducted through a major university research centre (reports). However they had varying degrees of quality in respect to methodological rigour evidenced. In making an assessment of quality we recognised the challenges associated with collecting reasonable respondent/participant numbers given the under-representation of Indigenous Peoples amongst university students and particularly in HDR studies. Moreover, the same methodological rigour may not be evidenced in reports as peer reviewed journals as they may have different target readership. However, there was some deficiency in a few of the publications in respect to insufficient articulation of research processes in terms of researcher relationships, ethical issues and rigorous analysis. This is not to suggest that the research for these publications was not sufficiently rigorous but just that these aspects of the process were not explained in the publications; and we therefore highlight that making this clear is an integral part of publishing research. We consider it important that publications clearly explain relationships between researchers and participants and how the studies were conducted in respect to ensuring cultural safety of participants and whether the projects involved Indigenous researchers.

Authorship of the Publications

Arguing for the Indigenous involvement in research and policy development, Maddison (2012) said that while research evidence can make a positive contribution to Indigenous policy development, the research that has seemingly carried most weight with policy-makers has often not been research guided and informed by Indigenous perspectives. Thus, she recommends a different form of Indigenous participation in which Indigenous Peoples are not just ‘consulted’ by government as passive individuals but are partners in a genuine dialogue about policy. In accordance with this it was valuable to see the privileging of Indigenous voices (see Rigney 1999) in research on Indigenous HDR students in that eight of the 12 publications explicitly identified the inclusion of Indigenous authors (Behrendt et al. 2013; Elston et al. 2013; Harrison et al. 2017; Schofield et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014). In six cases the lead author was Indigenous; of those, four were sole authored. Moreover, in one other publication (Barney 2013), there was acknowledgement of an Indigenous research assistant. In other publications, involvement with Indigenous university student support units/centres was noted.

While some of the work of Trudgett (2009, 2011, 2013) included quantitative or quantitative and qualitative data collection processes, and Elston et al. (2013) included some outcome data analyses, the remainder of the publications presented solely qualitative studies, conceptual approaches or were reports; thus there was no substantive difference in the methodological approaches utilised across Indigenous-led or non-Indigenous-led publications though some of the publications (by Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers alike) mentioned the value of qualitative research for research with Indigenous Peoples given cultural emphasis on narratives. Moreover, quality deficiency in explanation of researcher relationships was evident in publications led by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers.

The Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2 displays the key characteristics of the 12 publications. The publications provided evidence for a number of contributing factors in attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students (see Table 2).

In terms of emphasis, most attention focussed on support mechanisms (4/12 or 33.3%) for the attraction, retention and completion of HDR students (Behrendt et al. 2012; Elston et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2013). Another five publications (5/12 or 41.6%) had an explicit focus on the supervision of Indigenous HDR students as a key strategy of support (Day 2007; Harrison et al. 2017; Laycock et al. 2009; Trudgett 2011, 2014). The other three publications (3/12 or 25%) focused on academic (Schofield et al. 2013; Barney 2013) and non-academic barriers (Chirgwin 2014) to completion. The nature of the types of support and constraints are explored below.

Facilitators: Support Mechanisms for Indigenous HDR Students (Behrendt et al. 2012; Elston et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2013)

Trudgett (2013) succinctly summed up the current context in which support is offered to Indigenous HDR students in advising the Australian higher education sector does not consider Indigenous HDR students as a separate cohort or provide individually- or culturally-tailored support mechanisms. Support structures presently available to Indigenous HDR students are the same as available to Indigenous undergraduate students or non-Indigenous HDR students. Trudgett (2013) identified four required primary support mechanisms: (1) assistance from the Indigenous department at their institution; (2) quality supervision; (3) financial assistance; and (4) support from family and community to enrol in and continue with HDR studies, and where Indigenous Peoples studies are focused on Indigenous culture, people and issues, some people within family and community may also provide guidance on research methodologies, content and even dissemination of the research. These themes were in other studies and form part of the organising framework in which the review results are presented.

Facilitating Environments: Indigenous Departments and Units

Indigenous departments differ across universities. Some provide cultural, pastoral and academic support whilst other Indigenous departments operate through a combination of support services, teaching and research responsibilities. Very few provide appropriate support for postgraduate students (Trudgett 2013). Thus, the notion of appropriate spaces in facilitating success for Indigenous HDR students was identified across a number of publications (Barney 2013; Elston et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2013). Barney (2013) for example, referred to a Postgraduate Meeting Space, and said it provided essential ‘kayak’ and ‘paddles’ to assist Indigenous students in navigating the waters of postgraduate study. Elston et al. (2013) similarly recognised the significance of providing a supportive environment in which Indigenous HDR health students could flourish. In developing a cohort model for building Indigenous researcher capacity, facilitators of success Elston et al. (2013) found to be critical in establishing the cohort and enabling the program of work included: (1) establishment of cohort values embedded in respect and Indigenous knowledges; (2) developing a visual representation (logo) to establish a sense of identity and belonging in the affiliated group; (3) Indigenous ownership and leadership; (4) creating and maintaining two safe ‘holding spaces’—one operating at the cultural interface and in which Indigenous and non-Indigenous members interacted, and another where Indigenous affiliates only came together in a safe environment; and (5) privileging Indigenous knowledges and methodologies. Standard productivity measures were used including publications, participation, completions and post-completion employment.

To expand the role of Indigenous departments to better support Indigenous HDR students, Trudgett (2009, 2013) made seven recommendations: (1) ensure department staff provide a welcoming environment; (2) employ more Indigenous academics with appropriate research qualifications in stable positions to build supervisory capacity; (3) ensure all Indigenous departments have Indigenous Postgraduate Support Officers; (4) conduct regular workshops to provide Indigenous postgraduate students with peer support; (5) facilitate orientation to the department for all Indigenous Postgraduate students; (6) establish an Indigenous Postgraduate support group to avoid exclusion and isolation; and (7) ensure scholarship information is available in advance. We argue that such initiatives are important for creating not only a culturally-safe place for Indigenous HDR students to undertake research but also could work with a cohort model in which individuals are informed, included and can share experiences in a supportive environment of learning from each other.

Quality Supervision of Indigenous HDR Students (Behrendt et al. 2012; Day 2007; Harrison et al. 2017; Laycock et al. 2009; Trudgett 2011, 2013, 2014)

All HDR students require standards of excellence in supervision. However, Indigenous HDR students require the support of supervisors who have additional skill sets and expertise. Strong supervision supporting cultural safety and recognising Indigenous knowledge systems are associated with ensuring students are respected to maintain their own identities and conduct culturally-sensitive research. In examining the importance of good supervision (Trudgett 2011, 2013, 2014), the following critical aspects were identified: developing and maintaining strong and trusting relationships; supervisors having respect for students as knowledge holders; involving community and Elders in supervisory processes; recognition of different interpretations of process; supervision styles recognising the key principles of cultural safety including using Indigenous methodologies (Day 2007); mandatory training in culturally-competent practice; providing strong research environments including for example, research training and mentoring (Day 2007); and acknowledging gender and cultural background can be important for some students.

Recognising the commitments and workload of Indigenous supervisors, Behrendt et al. (2012) recommended system flexibility to allow for supervisors from other institutions to be members of the supervision team when appropriate supervisors are unavailable within a particular university/department.

The value of having a thesis examined by other Indigenous researchers who share a partial subject position to Indigenous students has also been recognised. Harrison et al. (2017) highlight the challenges presented by having a very small pool of Indigenous examiners available in Australia. They note the possibility an examiner will know the candidate, creating a conflict of interest; and potential bias introduced into the marking of the thesis. In some circumstances, bias can work in favour of the candidate, but in others cases the limited number of Indigenous academics in Australia can result in ‘tricky’ processes and be detrimental to the candidate (Harrison et al. 2017).

Laycock et al. (2009) provided a practical resource guide for supervisors to support Indigenous health researchers. It offers practical information, advice, strategies and narratives of success stories in Indigenous health research. Topics covered include setting up a workplace with the capacity to employ, support and train a developing researcher, research processes and doing research work in, and with, Indigenous communities.

Financial Assistance (Behrendt et al. 2012; Schofield et al. 2013; Trudgett 2014)

Schofield et al. (2013) argued that Indigenous participation in higher education has increased modestly and this has been strongly related to financial rewards to universities being provided by the federal government. Behrendt et al. (2012) advocated that federal government scholarship funding should be equivalent to universities’ target numbers for Indigenous Peoples undertaking HDR programs in order to support completion of degrees as well as to ensure a pipeline of Indigenous HDR students. However, Schofield et al. (2013) also identified providing specific financial support can detract from the experiences of Indigenous HDR students in that some non-Indigenous students perceive this kind of positive discrimination as discriminatory and unacceptable in university merit-based systems. It is important to acknowledge that what some are viewing as not in accord with merit are policies/practices that have been implemented in universities. Such policies/practices have been developed to provide some redress to the discriminatory status quo and history of racism which has permeated Australian society (including white institutions like universities). The reaction from some to such initiatives is discriminatory and reflects lack of recognition of their own privileged position. As Walter and Butler (2013, p. 401) noted ‘Professing colour-blindness exculpates those who are racially privileged from responsibility for the unequal status and disadvantage of those who are not and, critically, from overtly recognising their own race privilege. Disavowing the racial dividend embeds the status quo’.

Trudgett (2014) argues financial support is an equity issue because Indigenous students often experience greater financial difficulties than other students. Indeed, she argued, based on need and student profile, additional assistance is required as currently available assistance is received at the same rate as other HDR students. Yet Indigenous students carry additional burdens increasing study costs, for instance, many are mature aged students with existing responsibilities; maintenance of cultural, family and community responsibilities; and movement from home communities to study. Thus, we suggest universities need to have a much more individually-tailored approach to recognising needs and providing assistance as required; which might also vary throughout different stages of the HDR candidature.

Support from Family and Community (Trudgett 2014)

Families and communities play a key role in Indigenous HDR students’ lives and projects, e.g. students’ projects invariably focus on issues prioritised by communities and conducted in partnership with those communities. Trudgett (2014) suggests this should be seen as nurturing environment in which students can be supported in the development of research methodologies, content and dissemination and implementation of findings. This connection to family and community becomes even more important because many students are first in their family to undertake postgraduate study and it provides a link to understanding the student’s work while modelling opportunities to others.

Academic and Non-academic Barriers to Attraction, Retention and Completion (Barney 2013; Day 2007; Chirgwin 2014; Schofield et al. 2013)

Schofield et al. (2013) suggests under-representation of Indigenous students in HDR programs and constraints to improved participation and completion are largely embedded in institutional dimensions including government and university policy responses. Like Trudgett (2009, 2013) they propose the higher education context is “largely indifferent to progressing broader social goals and projects such as social equity because it is not core business” (Schofield et al. 2013, pp. 15–16). Several institutional barriers were identified as contributing to the underrepresentation of Indigenous HDR students in universities. Critical was institutional racism and discrimination—failing to provide an ‘Indigenous-friendly’ environment and culture in universities. For instance, as cited in Schofield et al. (2013) a survey conducted by the National Tertiary Education Union in 2011 found 79.5% of Indigenous workers considered they did not receive as much respect as non-Indigenous counterparts; 71.5% experienced direct racial discrimination and racist attitudes.

In addition there are also individual and cultural level issues, including: low socio-economic status; often having moved from remote locations; and past experiences (Schofield et al. 2013). Lovitts (cited in Chirgwin 2014) said while many Indigenous students had successfully managed challenges during their undergraduate studies, once they undertake independent research as producer of knowledge there is extra personal responsibility. Chirgwin (2014) noted some researchers have been critical of prior discourse on barriers to higher education for Indigenous Peoples which have focused on a ‘deficit paradigm’. Chirgwin (2014) stated this perception is, to a large extent, supported by recurrent themes of shortcomings in individual students, government policy and funding, university culture and support, and culturally sensitive interactions at the staff–student level.

Indigenous HDR students also experience cultural and social isolation within universities and lack peer support from non-HDR Indigenous students. While the many benefits of Indigenous support units for undergraduate students have been identified, some are said to offer limited support for postgraduate and doctoral students. Trudgett (2009) noted problems experienced by some postgraduate students are associated with feeling staff were not welcoming/approachable, a lack of Indigenous academics employed in the units/centres, and support officers having minimal understanding of postgraduate studies. Coupled with cultural isolation, Barney (2013) reported some Indigenous HDR students found lack of cultural understanding, safety and support in the university system and Trudgett (2011), recognising the potential lack of knowledge of non-Indigenous supervisors, suggested that they should receive cultural awareness training. However, we note that the nature of such training, for instance brief 2 day workshops is likely to be inadequate to make sustainable change (Bainbridge et al. 2015; Jongen et al. 2018). A respectful two-way learning relationship between Indigenous students and supervisors is therefore recommended.

Effacement of Indigenous knowledges and cultures was identified as a significant issue (Schofield et al. 2013) and thus Trudgett (2011) emphasised the important role in cultural safety played by Indigenous Elders or community members in the supervision process. However, being able to provide Indigenous supervision is affected by the limited numbers of Indigenous academics within universities as well as workloads of those who do supervise. Day (2007) noted Indigenous staff may be enrolled in their own HDR studies while employed as academics and are mostly women who may have a wide range of responsibilities within education but also have broader socio-cultural support responsibilities. Therefore, Day (2007) suggested that there should be greater recognition that the social, cultural and academic lives of Indigenous staff are highly integrated with the communities they serve as educators. Further, Harrison et al. (2017) noted existing research about PhD examination highlighted four key areas of examination procedure (examiner expectations, standards, issues of quality and experience of the examination process itself) which may affect thesis examination outcomes. They suggested that there are two additional factors which also affect success of Indigenous doctoral students during the examination process, namely, distrust of processes and academic politics. While it is valuable to have an Indigenous examiner who has familiarity with methodologies, Harrison et al.’s (2017) research found there can be distrust in an institution previously viewed as disregarding non-Western approaches to research (see also Trudgett 2011). Distrust was further heightened by perceptions of ‘factionalism’ within academic processes (Harrison et al. 2017). Further, the previously accepted credibility of the doctoral examination process may be questioned through reflections on notions of objectivity, and the role of race and academic politics in higher education in Australia (Harrison et al. 2017). While it could be argued that being Indigenous does not necessarily make someone a suitable examiner, it is essential that content knowledge is considered in choosing examiners. Particularly where an Indigenous methodology has been used it is critical that an examiner (Indigenous or non-Indigenous) is proficient with the methods and able to assess the thesis in terms of how the methodology has been applied, and data collected and analysed.

Discussion

Contributions of the Publications—Quantity, Nature, Quality and Characteristics

The review highlights that little attention has been paid to examining the specific needs of Indigenous HDR students in Australia with minimal outputs examining Indigenous Australian HDR student attraction, retention and completions over the period of publications which were reviewed, and, for two of those years (2008 and 2010) there were no publications. Mapping the number of publications showed random dispersal, that publications have not moved much beyond qualitative descriptive studies and that generally, outputs have not increased across time.

In the next three sub-sections we present a summary of the theoretical grounding of the publications, their methodological approaches and participant profile/sample. This is also summarised in Table 3.

Theoretical Grounding

Overall, the publications reviewed provided limited reference to theory. Two publications referred to figures about under-representation of Indigenous Peoples in university enrolments and completions (Trudgett 2009, 2011). The majority of the other publications referred to earlier research in the field (some of which, such as curricula, was not HDR-specific). These included: barriers (Day 2007; Schofield et al. 2013); doctoral examination (Harrison et al. 2017); enrolment and completion (Chirgwin 2013); experience as doctoral students (Trudgett 2014); support and/or success factors (Barney 2013; Day 2007); support units (Trudgett 2013); and researching with/about Indigenous Peoples (Elston et al. 2013). The limited use of theory likely reflects this research field being in its infancy but the evidence highlights the need for greater engagement with theory across a range of disciplinary areas, such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education (which itself draws from the aforementioned fields as well as other areas). Most particularly given a growing literature on the importance of understanding and privileging Indigenist research both internationally (e.g. Battiste 2013; Kovach 2015; Smith 2012) and in Australia (e.g. Nakata 2010; Rigney 1999) there could have been more reference to use of specific Indigenous methodologies in the publications.

Methods Approach

The publications reviewed used a range of methods approaches. Two publications (Trudgett 2009, 2011) used surveys which included some open-ended qualitative questions, and two others used a mixed methods approach combining surveys and interviews (Chirgwin 2014; Trudgett 2013). Two publications were conceptual (Day 2007; Schofield et al. 2013). Of the six using qualitative methods (Behrendt et al. 2012; Barney 2013 Chirgwin 2014; Elston et al. 2013; Harrison et al. 2017; Trudgett 2014) most involved interviews although some also referred to other forms of data collection including Behrendt et al. (2013) who also used consultation, whilst Elston et al. 2013 used evaluations and outcome data. Several publications noted a qualitative approach was consistent with Indigenous Australians favouring participating in qualitative projects given cultural underpinnings in a narrative genre. One publication suggested the value of a culturally-responsive methodology (Chirgwin 2014) while another referred to all knowledge as being socially situated in the subject (Harrison et al. 2017). The evidence highlights the importance of future research being done with cognisance to culturally-appropriate methodologies, e.g. Indigenist research which privileges Indigenous voices (see Nakata 2010; Rigney 1999).

Participant Profile

Of the empirical publications, most studies involved students although some used other data sources including: supervisors in addition to students (Harrison et al. 2017); supervisors and graduates in addition to current students (Trudgett 2013); graduates and supervisors (Trudgett 2014); and researchers (Elston et al. 2013). As would be expected given the small cohort of Indigenous HDR students, the samples in the studies were small ranging from one student to 55 students and/or graduates. Where supervisors or other researchers were also studied the sample ranged from one to 33. Several publications had data gathered within one university (Barney 2013; Chirgwin 2014; Elston et al. 2013) and some were also from one faculty, including health (Elston et al. 2013) and education (Chirgwin 2013). Some studies involved multi-university and multi-faculty participants (Behrendt et al. 2012; Harrison et al. 2017; Trudgett 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014) with two (Trudgett 2009, 2011) involving participants from 23 universities and one (Behrendt et al. 2012) having participants from 39 universities. Thus, the evidence base for identifying strategies to achieve parity of admission and completion of HDR programs for Indigenous Peoples would be enhanced by studies including more inter-disciplinary/inter-university samples and multiple stakeholder perspectives from prospective/current/completed HDR students, families/community, supervisors, and university administrators.

Characteristics of the Publications in the Context of Interdisciplinary Indigenous Research

The state of Indigenous HDR research as examined in this review is consistent with most reviews conducted across diverse disciplinary Indigenous fields. For instance, in areas of Indigenous health; mentoring; family-centred interventions; program transfer and implementation; sexual assault; cultural competency; child and maternal health; suicide; and alcohol and other drugs (Sanson-Fisher et al. 2006; Clifford et al. 2013; McCalman et al. 2012; Bainbridge et al. 2014; Bainbridge et al. 2015; Jongen et al. 2014; Clifford et al. 2015; McCalman et al. 2014; McCalman et al. 2017; Doran et al. 2017) review authors reported that studies are primarily descriptive with little intervention or measurement of research and they generally lack rigorous methodological approaches. Similarly characterised, the Indigenous HDR research examined herein is in its very early exploratory phases and has not yet explored the effectiveness of strategies for Indigenous HDR students, captured its impact qualitatively or quantitatively, developed appropriate measures or assessed cost-effectiveness. Lack of evaluation research has also been noted recently by the Australian Government who are planning steps to rectify the situation by allocating “$10 million a year over four years to strengthen the evaluation of Indigenous Affairs programmes” (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2017). Evaluation research will strengthen our case for investment in Indigenous HDR students by understanding what works for whom, under what conditions, through what strategies and with what consequences. Though the combinations of strategies that work are currently somewhat uncertain, we do have a base from which to bolster future research directions.

Facilitating Strategies and Constraints in Attraction, Retention and Completion

The review demonstrates evidence of research doing more than just describing problems but also, as Sanson-Fisher et al. (2006) emphasise, providing details about initiatives for making positive change. Several publications focused on a specific aspect of the HDR experience, and in sum provided a useful overview of individual/cultural and institutional facilitators and barriers to Indigenous HDR student successes (as summarised in Table 2). Facilitators included several factors for developing institutional capability to better support Indigenous students. These included increased scholarship funding (Behrendt et al. 2012); dedicated postgraduate researcher support (Barney 2013; Trudgett 2013); Indigenous student support centres catering for HDR student needs separate to that of undergraduates (Trudgett 2009); strong and appropriate supervision (Schofield et al. 2013; Trudgett 2011, 2014); having role models, Indigenous leadership, building researcher capacity; exclusive Indigenous spaces and mentoring (Elston et al. 2013); correct mix of supervisors (Behrendt et al. 2012); specific support/training for supervisors of Indigenous students (Laycock et al. 2009); and Indigenous examiners for theses (Harrison et al. 2017).

A majority of the publications articulated strategies or provided recommendations to improve student experience and/or assist attraction, retention and completion (Behrendt et al. 2012; Day 2007; Laycock et al. 2009; Schofield et al. 2013; Trudgett 2009, 2011, 2013). However, across the publications there is limited analysis of specific programs, interventions or improvements which have occurred within programs or reference to signature programs with high completion/success rates or providing targeted, culturally-specific support for Indigenous HDR students. Though largely descriptive in nature, the reviewed publications nevertheless provide foundational evidence for building a potential suite of strategies for implementation and may guide further research to establish the effectiveness of such strategies to support Indigenous HDR students. Moreover, the review suggests the need for future research emphasising intervention-based examinations.

New commitments to supporting Indigenous HDR students in Australia have been disseminated since the inclusion dates for this review. More investment in Indigenous HDR students is suggested in the form of guidelines, strategies and policy. For instance, the Australian Council of Graduate Research (ACGR) recently released Good Practice Guidelines for the Training of Indigenous Researchers. They propose specific strategies under six overarching aims: (1) ensuring that Indigenous research education is a university priority; (2) increasing the number of Indigenous graduate research candidates; (3) providing culturally-appropriate engagement and opportunities for Indigenous graduate research candidates; (4) maximising the likelihood that supervision of Indigenous graduate research candidates is appropriate; (5) promoting the unique perspectives that Indigenous graduate research candidates bring to knowledge; and (6) preparing Indigenous graduate research candidates for the careers of their choice (ACGR 2017). These primary aims partially address the identified institutional barriers encountered by HDR Indigenous students such as cultural and social isolation and lack of peer support, ongoing discrimination in universities, lack of cultural understanding, safety and support, effacement of Indigenous knowledge and thesis examination procedures. They do not address the individual and cultural factors that impede attraction, retention and completions; for instance past negative experiences in education, low-socio-economic situations, remote locations and changing personal circumstances such as ill-health. In either case, what works in achieving the implementation of such targets is largely unknown.

The Australian government has also contributed to increasing the access, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students by enshrining institutional incentives in policy. As noted, the ACOLA Review of Australia’s Research Training System 2016 had one strategic recommendation accepted by the government, namely doubled weighting for Indigenous HDR students in the HDR completions formula (ACOLA 2016). While such measures are useful, implementation is still left to institutional goodwill and with the small numbers of Indigenous HDR students there is unlikely to be a substantive difference to investments in student support—especially given that the dominant discourse in higher education institutions is centred on undergraduate students and mainstream HDR.

Limitations and Issues for Future Research and Policy

Limitations

Though a database search was undertaken multiple times using varying search terms only five articles were found focused on the topic of the review. Another seven articles of relevance were found through searching Google/Google Scholar and examining websites of researchers who were authors of publications—using a combination of terms. We broadened the search with the inclusion of such terms as Indig* research or Indig* but this elicited many more articles of no relevance to the topic. Google was able to locate articles not found through Boolean search terms even though a combination of terms needed to be used and each combination separately resulted in different articles being found. It could be surmised there may be other studies undertaken within universities which are not publicly available, and a limitation of our research was not analysing these and thus our article provides an initial systematic review of the publicly-available literature. Thus, future research could entail contacting Indigenous student support units/centres and academics at Australian universities to ascertain whether other analyses of barriers and enablers for Indigenous HDR students have been undertaken.

Issues for Future Research and Policy

Indigenous HDR students may share similarities to other groups of students (both HDR and undergraduate/postgraduate coursework) in respect to factors affecting attraction and retention. For instance, non-Indigenous students from low socio-economic backgrounds also face financial hardships, non-Indigenous students from remote areas may also suffer isolation, and students from a range of cultural backgrounds, genders and sexual orientations may have prior and ongoing experiences of discrimination. However, sharing some similarities with Indigenous Peoples in other colonised nations, Australian Indigenous students face culturally-specific challenges—most notably the legacy of colonialism which perpetuates lack of cultural understanding and safety within and outside universities. Indigenous HDR students, more particularly, confront non-recognition of Indigenous knowledge, lack of cultural/methodological expertise by their (usually) non-Indigenous supervisors, and too many demands on Indigenous supervisors. There is fertile ground for universities to create a climate of learning that draws on Australian Indigenous knowledges and accords with the view of Villegas (2010, p. 283), commenting on Aotearoa/New Zealand Indigenous higher education, that “tertiary education is a key site for Indigenous community development…at the nexus of knowledge and leadership… ‘higher’ education can become a space where Indigenous people find new applications for Indigenous knowledge and meaningful ways to express their creativity and culture”.

Though our searches on databases and Google/Google Scholar suggest there are many articles on Indigenous Peoples’ experiences in schooling and undergraduate (and to a lesser extent postgraduate coursework) university studies, there is limited research examining why Indigenous Peoples only continue into HDR studies in small numbers and the challenges they face and support received when they do undertake HDR programs. In addition to issues noted in the discussion and limitations sections, future research might also entail longitudinal studies of individual students to examine factors contributing to student withdrawal and highlighting success stories. Moreover though we used electronic databases and Google/Google Scholar to access articles to undertake this systematic literature review, we acknowledge that there are other tools for examining publications and assessing quality and impact, such as Scimago, Cabell’s, Web of Science, and the H Index or impact factors of specific journals, and these might be used in future research.

It is envisaged more in-depth studies should result in development of strategies (within universities and at national policy level) to attract, support and assist completion of Indigenous HDR students and future research may further address objectives of the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2011–2018 (Australian Government 2011) in providing a cohort of Indigenous HDR graduates to move into the academic workforce.

Conclusions

In providing an initial systematic review of the limited literature examining barriers and enablers of attraction, retention and completion of Indigenous HDR students, this article advances knowledge of inequities in educational opportunities and what is required to improve opportunities and enhance support within higher education institutions and from government. This article also contributes in emphasising the need for: intervention-based examinations and greater theoretical engagement across a range of disciplinary areas.

Further we emphasize that future research is done with cognisance to culturally-appropriate methodologies—and that Indigenous Peoples ask and seek answers to their own concerns (Smith 2012). Moreover, we highlight the importance of continuing to privilege Indigenous voices through research in this space being done by Indigenous Peoples. Future research should utilise Indigenous research methodologies and methods. We draw attention to the importance of both qualitative approaches including Indigenous Yarning; an Indigenous cultural form of conversation and sharing stories and knowledge (see Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010; Walker et al. 2014) as well as quantitative methods. Walter and Andersen (2013) produced the first book specifically examining Indigenous quantitative methodology with particular reference to nayri kati (good numbers) and the importance of research ‘framed through and within an Indigenous standpoint’ (p. 85).

The review reinforces the objectives of the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2011–2018 (Australian Government 2011) underscoring the necessity of increased representation of Indigenous Peoples in HDR programs and the higher education workforce.

Notes

Where the term Indigenous HDR student/Indigenous Peoples is used it refers to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander HDR students or Peoples except where specific reference is made to Indigenous Peoples internationally.

For the purposes of this article we use the term community to refer broadly to extended family and the cultural group with which individual Indigenous Peoples identify. We acknowledge, however, that the term is very complex and may have multiple meanings, but importantly must be as individuals and communities choose to define it. As Peters-Little (2010, p. 18) notes of community in Aboriginal Australia, given the diversity of definitions of community and the non-applicability of the one definition for all situations and diversity of groups within communities, it is important to “bring forth discussions on the importance of self-definition, as opposed to having bureaucracies determine who and what is a community or an Aboriginal person and what their structures of representation and socio-economic needs will be”.

Given the limited amount of research undertaken about Indigenous Peoples’ experiences in higher education, some of the literature referred to in this article is also mentioned in other articles developed by some of the authors.

Throughout this article the term supervisors means doctoral/research thesis supervisors (usually referred to as advisors in North American universities).

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2011). 238.0.55.001—Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2016 from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/latestProducts/3238.0.55.001Media%20Release1June%202011.

Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA). (2016). Securing Australia’s Future—Research training system review. Retrieved February 2, 2017 from http://acola.org.au/index.php/projects/securing-australia-s-future/saf13-rts-review.

Australian Government. (2011). Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2011–2018. Canberra, Australia: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia. Retrieved August 31, 2016 from http://apo.org.au/resource/indigenous-economic-development-strategy-2011-2018.

Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). (2017). A statistical overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in Australia. Retrieved February 3, 2017 from https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/statistical-overview-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-australia-social#Heading363.

Bainbridge, R., McCalman, J., Clifford, A., & Tsey, K. (2015). Cultural competency in the delivery of health services for Indigenous people. Issues paper no. 13. Produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Canberra/Melbourne: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare/Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., McCalman, J., & Towle, S. (2014). The quantity, quality and characteristics of Indigenous Australian mentoring: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1263.

Ballew, R. (1996). The experience of Native American women obtaining doctoral degrees in psychology at traditional American universities. PhD dissertation. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee via ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Social Sciences, Retrieved December 4, 2014.

Bancroft, S. (2013). Capital, kinship, and white privilege: Social and cultural influences upon the minority doctoral experience in the sciences. Multicultural Education, 20, 10–16.

Barney, K. (2013). ‘Taking your mob with you’: Giving voice to the experiences of Indigenous Australian postgraduate students. Higher Education Research & Development, 32, 515–528.

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonising education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Limited.

Behrendt, L., Larkin, S., Griew, R., & Kelly, P. (2012). Review of higher education access and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Final report. Canberra: DIISRTE.

Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about Yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies., 3(1), 37–50.

Birmingham, S. (2016). Taking action to unlock the potential of Australian research, Friday 6 th May 2016 Media Release of Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham, Minister for Education and Training. Retrieved February 2, 2017 from http://ministers.education.gov.au/birmingham/taking-action-unlock-potential-australian-research.

Bock, A. (2016). Rise of Aboriginal PhDs heralds a change in culture. The Sydney Morning Herald, March 17, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2016 from http://www.smh.com.au/national/education/rise-of-aboriginal-phds-heralds-a-change-in-culture-20140316-34vqm.html.

Cameron, S., & Robinson, K. (2014). The experiences of Indigenous Australian psychologists at university. Australian Psychologist, 49, 54–62.

Childs, S. E., Finnie, R., & Martinello, F. (2016). Postsecondary student persistence and pathways: Evidence from the YITS-A in Canada. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9424-0.

Chirgwin, S. K. (2014). Burdens too difficult to carry? A case study of three academically able Indigenous Australian Masters students who had to withdraw. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(5), 594–609.

Clifford, A. C., Doran, C. M., & Tsey, K. (2013). A systematic review of suicide prevention interventions targeting Indigenous peoples in Australia, United States, Canada and New Zealand. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 463. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-463.

Clifford, A., McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R., & Tsey, K. (2015). Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: A systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv010.

Day, D. (2007). Enhancing success for Indigenous postgraduate students. Synergy, 26, 13–18.

Department of Education and Training (DET). (2015). Review of Research Policy and Funding Arrangements. Retrieved February 2, 2017 from https://www.education.gov.au/review-research-policy-and-funding-arrangements-0.

Department of Education and Training (DET). (2017). Review of Higher Education Access and Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Retrieved February 3, 2014 from https://www.education.gov.au/review-higher-education-access-and-outcomes-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people.

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2017). $10m a year to strengthen IAS evaluation [Press release]. Retrieved May 15, 2017 from https://ministers.dpmc.gov.au/scullion/2017/10m-year-strengthen-ias-evaluation.

Doran, C.M., Kinchin, I., Bainbridge, R., McCalman, J., Shakeshaft, & A.P. (2017). Effectiveness of alcohol and other drug interventions in at risk Aboriginal youth: An Evidence Check rapid review brokered by the Sax Institute (www.saxinstitute.org.au) for the NSW Drug and Alcohol Population and Community Programs, 2017.

Elliott, S.A. (2010). Walking the worlds: The experience of native psychologists in their doctoral training and practice. PhD dissertation. Santa Barbara: Fielding Graduate University via ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Social Sciences, Retrieved December 4, 2014.

Elston, J. K., Saunders, V., Hayes, B., Bainbridge, R., & McCoy, B. (2013). Building Indigenous Australian research capacity. Contemporary Nurse, 46, 6–12.

Farrington, S., Daniel DiGregorio, K., & Page, S. (1999). The things that matter: Understanding the factors that affect the participation and retention of Indigenous students in the cadigal program at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney. Sydney: Annual Conference of the Australian Association of Research in Education.

Grant, B., & McKinley, E. (2011). Colouring the pedagogy of doctoral supervision: Considering supervisor, student and knowledge through the lens of Indigeneity. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 48, 377–386.

Harrison, N., Trudgett, M., & Page, S. (2017). The dissertation examination: Identifying critical factors in the success of Indigenous Australian doctoral students. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(1), 1115–1127.

Hutchinson, P., Mushquash, C., & Donaldson, S. (2008). Conducting health research with Aboriginal communities: Barriers and strategies for graduate student success. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 31(1), 268–278.

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R., & Clifford, A. (2018). Cultural Competence in Health: A review of the evidence. Singapore: SpringerNature.

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R., & Tsey, K. (2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal and child health and wellbeing: A systematic search of programs and services in Australian primary health care settings. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 251.

Kippen, S., Ward, B., & Warren, L. (2006). Enhancing Indigenous participation in higher education health courses in rural Victoria. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 35, 1–10.

Kovach, M. (2015). Emerging from the margins: Indigenous methodologies. In Susan Strega (Eds.), Research as resistance: Revisiting critical indigenous and anti-oppressive approaches (2nd ed., pp. 43–64). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press Inc.

Laycock, A., Walker, D., Harrison, N., & Brands, J. (2009). Supporting Indigenous researchers: A practical guide for supervisors. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health.

Maddison, S. (2012). Evidence and contestation in the Indigenous policy domain: Voice, ideology and institutional inequality. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 71(3), 269–277.

McCalman, J., Bridge, F., Whiteside, M., Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., & Jongen, C. (2014). Responding to Indigenous Australian sexual assault: A systematic review of the literature. SAGE Open, 2014, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013518931.