Abstract

High school students’ accuracy in estimating the cost of college (AECC) was examined by utilizing a new methodological approach, the absolute-deviation-continuous construct. This study used the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09) data and examined 10,530 11th grade students in order to measure their AECC for 4-year public and private postsecondary institutions. The findings revealed that high school students tended to overestimate the cost of college, especially 4-year public in-state tuition. Second, this investigation explored AECC differences across racial/ethnic groups. Lastly, this research examined how AECC differed based on racial/ethnic and college financial-related factors (importance of cost on college enrollment, knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA, and eligibility for financial aid). This examination is important because it is the first critical analysis of AECC and is timely given the data were collected immediately after the Great Recession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A calamity of circumstances has made financing college a challenge for students seeking postsecondary education. Some concerns include an increase in college tuition and fees, a reduction in federal and state contributions to offsetting students’ costs for college attendance, and an increase in students’ dependency on loans to pay for college attendance (Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education and Penn Alliance for Higher Education [Pell Institute] and Democracy [PennAHEAD] 2015). Further contributing to this situation is the influence that cost of college has on high school students’ college choice process (De La Rosa 2006; Perna 2006a, b; Post 1990). Little is understood of the discrepancy between high school students’ perceptions of and actual cost of college. Even less is understood of racial/ethnic group differences that exist in high school students’ accuracy in their estimation of the cost of college (AECC), including along college financial-related factors. College financial-related factors include elements such as importance of cost on college enrollment, knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA, and eligibility for financial aid. Examining students’ AECC is important because it may influence the type of higher education institution they explore during their college choice process and perhaps most dramatically, if they will even explore enrolling in postsecondary education. Numerous studies (e.g., Addo et al. 2016; Castillo and Hill 2004; Castillo et al. 2010; Hahn and Price 2008; Heller 1999; Linsenmeier et al. 2006) found racial/ethnic differences along college financial-related factors and college enrollment decisions. Further analysis of both areas is necessary in an effort to identify causes of the relatively stagnant number of students of color enrolling in postsecondary education (Kena et al. 2016).

Theoretical Background: Race/Ethnicity and College Access

This investigation is framed along Perna’s (2006a) conceptual model of student college choice that includes four layers: habitus (e.g., demographic characteristics [which incorporates race/ethnicity and gender], cultural capital, and social capital); school and community contexts (e.g., availability of resources, types of resources, and structural supports and barriers); higher education context (e.g., marketing and recruitment, location, and institutional characteristics); and social, economic, and policy contexts (e.g., economic features and public policy characteristics). Perna’s model, which resembles the ecological systems theory developed by Bronfenbrenner (1979), conceptualizes students’ college access as being influenced by these four interconnected layers. This framework allows for the examination of how variables within and among each layer influence aspects related with students’ college access.

Supporting this conceptual model, a vast literature exists that has concluded that college enrollment rates are strikingly different for racial and ethnic groups (Avery and Kane 2004; Black and Sufi 2002; Hahn and Price 2008; Kim 2004; Perna 2000, 2007). Recent National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, n.d.a, n.d.c) data reveal racial/ethnic group differences in the percentages of recent high school completers (NCES, n.d.a) and 18- to 24-year-olds (NCES, n.d.c) who have enrolled in postsecondary education. While 42.1% of the U.S. population aged 18 to 24 are enrolled in postsecondary education, only 24.9% of Native American, 30.5% of Pacific Islander, 35.4% of Hispanic, and 35.6% of Black populations are enrolled in higher education (NCES, n.d.c). On the other hand, 44.4% of White, 44.5% of Mixed Race, and 65.3% of Asian populations in this age group are enrolled in postsecondary education.

A rich literature exists that examines racial/ethnic group differences in students’ postsecondary education enrollment. Racial/ethnic group membership has been found to be a predictor of college enrollment (Perna 2007) with Blacks and Latinas/os less likely to enroll in postsecondary education compared to Whites (Perna 2000). Furthermore, racial/ethnic group differences exist across postsecondary enrollment predictors, such as family income and assets (Zhan and Sherraden 2011), secondary school preparation (Engberg and Wolniak 2009; Solorzano and Ornelas 2002), program of study (Staniec 2004), availability of financial aid (Dynarski 2000; Kim 2012), selectivity of institution (Carnevale and Rose 2003; Reardon et al. 2012), and type of institution (Flores and Park 2013; NCES, n.d.b).

In sum, race/ethnicity is a significant predictor of students’ postsecondary education access. As a result, Perna (2007) urged the scholarly community to further investigate the manner in which different racial/ethnic groups make decisions about college access. This investigation provides an in-depth analysis of one element of the college enrollment process— racial/ethnic group differences in high school students’ accuracy in estimating the cost of college.

Purpose of Study

This examination is the first investigation to focus on the study of AECC. It presents a new methodological approach to examine AECC and explores the relations between students’ race/ethnicity and AECC using High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09) data for 10,530 11th grade students. Also, it assesses racial/ethnic group differences on AECC and on college financial-related factors. Specifically, this investigation was guided by the following questions:

-

(1)

How accurately did high school students estimate the cost of college at 4-year public and private institutions?

-

(2)

Are there any differences among racial/ethnic groups on high school students’ 4-year public and private AECC levels?

-

(3)

Do high school students’ 4-year public and private AECC levels differ based on race/ethnicity and college financial-related factors (importance of cost on college enrollment, knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA, and eligibility for financial aid)? Are there any interaction effects between race/ethnicity and each college financial-related factor on high school students’ 4-year public and private AECC levels?

This inquiry is especially timely given the data were collected immediately after the Great Recession. As Heller (1997) contended, examining more recent data is important when examining issues associated with cost of college given the ever-changing prices in college tuition. This research can help inform federal and state policies and high school staff and college administrators’ practices aimed at better disseminating information related to college costs to high school students and their families, and in particular to specific racial/ethnic groups who might need more targeted support in understanding the cost of college and other college financial-related influences.

Literature Review

Students’ Accuracy in Estimating the Cost of College

Research that has explored AECC examines high school students’ ability to accurately estimate the cost of college tuition and fees at public and/or private postsecondary institutions (Antonio and Bersola 2004; Avery and Kane 2004; Crowther et al. 1992; Horn et al. 2003; Merchant 2004; Mintrop et al. 2004; Olson and Rosenfeld 1985; Post 1990; Turner et al. 2004). In general, these studies concluded that high school students overestimate the cost of college tuition and fees. Turner et al. (2004), for example, discovered that two-thirds of students they surveyed in Georgia overestimated the actual cost of college tuition and fees. And high school students’ overestimation can be quite substantial. In their examination of California high school students’ AECC, Antonio and Bersola (2004) found that students on average overestimated the annual cost of college by approximately $26,000 at University of California Davis, $25,000 at California State University Sacramento, and $9700 at a local community college. Further, students’ overestimation of the cost of tuition and fees tends to be greater for 4-year public as compared to 4-year private postsecondary education institutions (Horn et al. 2003; Olson and Rosenfeld 1985).

Analyses of high school students’ AECC uncovered differences across demographic characteristics such as (a) race/ethnicity (Antonio and Bersola 2004; Horn et al. 2003; Post 1990), (b) socioeconomic status (SES; Antonio and Bersola 2004; Bueschel and Venezia 2004; Grodsky and Jones 2007; Horn et al. 2003; Merchant 2004; Olson and Rosenfeld 1985; Turner et al. 2004), and (c) gender (Horn et al. 2003). Overall, racial/ethnic group membership was not found to be a consistent predictor of high school students’ AECC; studies had conflicting findings regarding which racial/ethnic group was more accurate and inaccurate in approximating the cost of college. Some scholarship identified Latinos (e.g., Antonio and Bersola 2004) while others recognized Blacks (e.g., Horn et al. 2003) as most accurate in estimating the cost of college. In terms of most inaccurate, Horn et al. (2003) identified Latinos and Antonio and Bersola (2004) determined Southeast Asians were most imprecise. Mixed results were also found relative to students’ SES and AECC. Some studies concluded that students with higher levels of SES tended to more accurately estimate the cost of college (Antonio and Bersola 2004; Horn et al. 2003; Olson and Rosenfeld 1985). However, other studies found no significant associations between SES and AECC (Bueschel and Venezia 2004; Merchant 2004; Turner et al. 2004). As for gender, male students tended to have more accurate estimates of the cost of college than female students (Horn et al. 2003). Horn et al. (2003), for example, found that 17.2% of males versus 15.3% of females accurately estimated the cost of college.

Methodological Approaches

The majority of studies that examined high school students’ AECC explored AECC as one of many factors related to high school students’ college access. As a result, the theoretical construct employed (i.e., range-categorization AECC) and types of statistical analyses done along AECC were insufficient. Likewise, past studies are limited given their (a) use of small sample sizes (e.g., Antonio and Bersola 2004; Avery and Kane 2004; Crowther et al. 1992; Ikenberry and Hartle 1998; Merchant 2004; Mintrop et al. 2004; Post 1990; Turner et al. 2004; Venezia 2004), (b) use of preselected response ranges instead of open-ended items (e.g., Avery and Kane 2004; Olson and Rosenfeld 1985), and (c) failure to examine students’ AECC for private postsecondary education tuition (e.g., Antonio and Bersola 2004; Avery and Kane 2004; Bueschel and Venezia 2004; Merchant 2004; Mintrop et al. 2004; Post 1990; Turner et al. 2004; Venezia 2004). Beyond methodological limitations, the manner in which AECC has been conceptualized, with the use of the range-categorization construct, is problematic, an area that will be discussed in the next section.

Range-Categorization

Several studies (e.g., Antonio and Bersola 2004; Avery and Kane 2004; Bueschel and Venezia 2004; Crowther et al. 1992; Horn et al. 2003; Merchant 2004; Mintrop et al. 2004; Olson and Rosenfeld 1985; Turner et al. 2004) examined AECC by utilizing a range-categorization approach. This method employs a researcher determined categorical range that classifies students. The range can be along a dollar value (e.g., the estimate is within $2000 and $2500 of the actual cost of college) or percentage (e.g., the estimate is within 15% of the actual cost of college). However, some accuracy ranges are quite extreme; Antonio and Bersola (2004), for example, designated students as accurate estimators if they estimated the cost of tuition as up to twice (i.e., 200%) the actual cost. The categorical classification is often defined along a grouping of students (e.g., accurate versus inaccurate or overestimators versus underestimators).

Horn et al.’s (2003) study is the most comprehensive investigation that exemplifies range-categorization AECC. These researchers used data from the Parent and Youth Surveys of the 1999 National Household Education Surveys Program (NHES:99) to examine 7910 students in grades 6-12 and their knowledge of the cost of attending college, including their ability to accurately estimate its cost. The researchers chose an arbitrary percentage range of within 25%Footnote 1 and categorized all students who estimated the cost of college and fees within this percentage of the actual cost as accurate. Those who estimated the cost of college outside of the 25% range were classified as inaccurate. For example, if the average 4-year public tuition level in a state was $10,000, all individuals who estimated the cost of 4-year public tuition between $7500 and $12,500 were classified as accurate estimators. Those students who estimated the cost of tuition below $7500 or above $12,500 were categorized as inaccurate estimators. Given the binary classification of accurate and inaccurate, the only type of regression analyses these scholars could employ was logistic regression.

While the range-categorization AECC is frequently employed in examining high school students’ AECC, it is problematic. First, a researcher determined categorical range, for example, 25%, is arbitrary. There is no literature that supports the selection of a particular range to categorize students. Also, the categorization of students as either accurate or inaccurate presents a whole set of concerns. For example, those students who were just outside of the 25% range would be classified as inaccurate. However, it could be argued that these students were just as “accurate” as those who were just under the 25% margin. In other words, using the prior example, a student who estimated the cost to be $7505 should be treated similarly as someone who estimated the cost at $7495. Further, those students whose estimates of the cost of college were just over the 25% range could have overestimated by $10 and been categorized in the same manner as a student whose estimate was at the 80% range and who overestimated by $25,000. We argue that these students’ AECC scores are tremendously different, but the binary categorization, such as the one used by Horn et al. (2003), treats them both the same. Next, the literature on racial/ethnic group differences along college financial-related factors will be presented.

Racial/Ethnic Group Differences in College Financial-Related Factors

Some studies (e.g., Hahn and Price 2008; Heller 1997, 1999; Kim 2004; Kim et al. 2009; Paulsen and St John 2002; St. John et al. 2005) examined racial/ethnic group differences relative to college financial-related factors and students’ college enrollment decisions. College financial-related influences on college enrollment decisions examined in the literature include price of college (De la Rosa 2006; Greenfield 2015; Hahn and Price 2008; Heller 1999; Perna and Titus 2005; St. John et al. 2005; Zarate and Pachon 2006), borrowing to pay for college (Addo et al. 2016; Hahn and Price 2008), and availability and knowledge of financial aid opportunities (Bell et al. 2009; De la Rosa 2006; Greenfield 2015; Hahn and Price 2008; Hu 2010; Immerwahr 2003; Kim et al. 2009; Perna and Steele 2011; St. John et al. 2005; Zarate and Pachon 2006). In general, students of color, in particular Blacks and Latinos, tend to have lower levels of college financial knowledge and are more sensitive to the role finances have in their college enrollment decisions (Grodsky and Jones 2007; Tomás Rivera Policy Institute 2005).

High school students’ knowledge of the cost of college is a central factor in their college choice process (Bowen et al. 2009; Crowther et al. 1992; Long 2004; Orfield 1992; Perna 2006a, b). Several studies (e.g., Heller 2006; Kane 1994; Leslie and Brinkman 1987; McPherson and Schapiro 1991; Post 1990; Shires 1995; St. John 1990) examined students’ sensitivity to college costs and their postsecondary education enrollment decisions. For example, Kane (1994) estimated that a $1000 increase in the price of tuition was associated with a 15-percentage point decline in college enrollment for Blacks and a 13-percentage point decrease for Whites. While such studies vary in the effect size of tuition increase, they concluded that an inverse relation exists between tuition and enrollment rates; an increase in the cost of college decreases students’ enrollment rates. While this literature stresses the importance of the cost of college on students’ enrollment decisions, it fails to examine the role that high school students’ knowledge of the cost of college has on high school students’ college choice process.

Hahn and Price (2008) concluded that Black and Latino students who were qualified for but decided to not enroll in postsecondary education based their decision primarily on the following factors: price of college, availability of grant or scholarship aid, and aversion to borrowing. However, there are inconclusive results regarding which student racial/ethnic group is most sensitive to college financial-related factors in their college choice process. Perna and Titus (2005), for example, reported that Blacks are more sensitive to the cost of college and availability of financial aid in their enrollment decisions compared to other racial/ethnic groups. On the other hand, the Tomás Rivera Policy Institute (2005) found that levels of awareness and understanding of college prices and financial aid are particularly low among Latino students.

The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) is used to determine federal (e.g., Pell Grants) and state assistance to students enrolling in postsecondary education. However, students have limited knowledge and reduced completion rates of FASA (Kantrowitz 2011; McKinney and Novak 2015); it is estimated that students who fail to complete a FAFSA forgo a total of $24 billion annually in college financial assistance (Kantrowitz 2011). While the percentage of students who fail to file a FAFSA has decreased in the last decade, the number of students who neglect to submit a FAFSA has remained relatively flat during this same period (Kantrowitz 2011). In their comprehensive review of the role of aid programs in students’ enrollment levels, Deming and Dynarski (2010) identified the effect of substantial paperwork and administrative hurdles in preventing program goals. Using data from the 2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:08), Kantrowitz (2011) found that 22.9% of students who did not file a FAFSA attributed their failure to file to limited information about how to apply for financial aid. Other studies (e.g., Kofoed 2016; McKinney and Novak 2015) identified racial/ethnic group differences in students’ FAFSA filing behavior. Namely, Blacks who attended a 4-year public or private postsecondary institution were more likely to file a FAFSA in contrast to Whites; differences between Latinos’ likeliness to complete a FAFSA compared to Whites were only evidenced in those who enrolled in 4-year public institutions. Similarly, Kofoed (2016) concluded that Pell-eligible Blacks and Latinos tend to complete a FAFSA at higher rates as compared to similar White students.

It is important to note that most of the research exploring college financial-related factors focused on Whites, Blacks, and Latinos, neglecting to examine other racial/ethnic groups such as Asians. Furthermore, studies failed to investigate racial/ethnic group differences in how college financial-related factors influence students’ ability to accurately estimate the cost of college. Furthermore, the research has not examined the intersection of college financial-related factors and race/ethnicity on students’ accuracy in estimating the cost of 4-year public and private tuition.

Methods

Data

Participants

The HSLS:09 includes 25,210 ninth graders from 940 schools throughout the US. HSLS:09 comprises base year data collected in 2009 and the first follow-up data collected in the spring of 2012 when participants were expected to be 11th graders. This study used the first follow-up data for two reasons. First, there was a large amount of missing data in the ninth graders’ estimation of the cost of college, and 11th graders tend to more accurately estimate the cost of college compared to 9th graders (Antonio and Bersola 2004; Bell et al. 2009; Mintrop et al. 2004; Perna 2006b).

The sample size was reduced to 10,530 to take into account missing data, those students who did not answer or indicated they did not know the estimated cost of college, and outliers. First, students whose residential states were missing were excluded because state information was necessary to associate respondents with their state’s average 4-year public tuition level. Second, those students who did not provide estimates of 4-year public and/or private tuition were excluded. Further, we screened outliers in the sample. These outliers included students whose estimates were exceptionally deviant from the means, such as “$1” or “$99,999.00.” Bangerjee and Iglewicz (2007) recommended that researchers employing large sample size datasets use a modified boxplot outlier-labeling procedure. Thus, we completed the outlier labeling procedure to screen out outliers using the more conservative estimate of 2.2 instead of 1.5 that is normally used in the boxplot procedure.

Of the 11th graders in the sample (N = 10,530), 51.4% were male and 48.6% female (see Table 1). The following was the racial/ethnic breakdown: 58.1% White, 13.9% Hispanic, 9.8% Black, 8.7% Asian, and 9.6% Other. Parental educational attainment of participants was high with 50.9% of students having at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Family income was divided into six categories, and nearly half (47.7%) of participants had family incomes greater than $75,000. Meanwhile, 22.1% of students came from families with incomes of $35,000 or less.

Variables

A total of 10 variables were used in this study. All variables were derived from the first follow-up data collected when participants were expected to be 11th graders. These variables were used to examine respondents’ demographic characteristics, students’ AECC utilizing the researchers’ developed absolute-deviation-continuous construct, and the college financial-related factors.

Demographic Variables

Demographic variables examined included gender, race/ethnicity, parental education, and family income. For the race/ethnicity variable, we combined all groups outside of White, Asian, Black, and Hispanic into a group we labeled Other. Students’ categorization of parental education and family income was guided by the scholarship of Hillman et al. (2015); these researchers also used HSLS:09 data to examine the interaction of racial/ethnic differences on college financial preparations and savings. Parental education was categorized into three groups: high school or less, associate degree or some college, and bachelor’s degree or higher. Students were classified into one of these groups based on the highest educational attainment of one of their parents. Family income categories were arranged into the same six categorical ranges (see Table 1) used by Hillman et al.

Absolute-Deviation-Continuous AECC

For this investigation, in an effort to address the limitations associated with calculating AECC using range-categorization, AECC was measured using the researchers’ developed absolute-deviation-continuous method. The formula used to calculate students’ AECC by using the proposed absolute-deviation-continuous method is represented below:

The absolute-deviation-continuous approach we developed uses the absolute value of the difference between a student’s estimate of the cost of college and fees and the actual cost. Thus, students who overestimate and underestimate the actual cost of tuition by $100 would have the same AECC level. Also, while the majority of studies that employed the range-categorization approach ignored students who underestimated the cost of college, the absolute-deviation-continuous method includes them. Further, absolute-deviation-continuous AECC does not categorize students (e.g., accurate or inaccurate) into arbitrary groupings. Instead, it treats students’ AECC levels as continuous, which allows for the use of multiple types of analyses. The use of a continuous dependent variable allows for a greater ability to capture sensitivity in how independent variables are associated with the dependent variable.

The variable, absolute-deviation-continuous AECC, was derived from two HSLS:09 questions: “What is your best estimate of the cost of one year’s tuition and required fees at a public 4-year college in your state?” and “What is your best estimate of the cost of one year’s tuition and required fees at a private college?” We obtained the actual cost of college by utilizing individual states’ averages of 4-year public tuition and fees and the national average of 4-year private tuition and fees for 2011–2012 (the same year students in the sample were surveyed) published by NCES (n.d.d). A high school student who resided in New York would be associated with the 4-year public in-state tuition rate in that same state. Individual state averages of 4-year public in-state tuition rates were used since tuition and fees vary from state to state. For example, during the 2011–2012 academic year, the average annual in-state cost to attend a 4-year public university in Vermont was $13,339 and Wyoming was $3501. Since 4-year private tuition rates are not governed by state policies, the U.S. average 4-year private tuition and fees was used, which in 2011–2012 was $23,460 (NCES, n.d.d). In addition, we used AECC raw scores for analysis of descriptive statistics:

College Financial-Related Variables

Three financial-related variables were examined in this study: (a) importance of cost on college enrollment, (b) knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA, and (c) perceived eligibility for federal and state aid. Importance of cost on students’ college enrollment used the question: “how important to you is the importance of cost when choosing a school or college?” Responses ranged from 1 = very important, 2 = somewhat important, and 3 = not at all important, and this variable was treated as an ordinal variable. Knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA was derived from the question: “will you complete a FAFSA?” Based on responses, a nominal variable consisting of “yes,” “no,” “don’t know what a FAFSA is,” and “haven’t thought about this yet” was created. A substantial percentage of students in our sample indicated they did not know what FAFSA was or had not thought about completing a FAFSA, 44.1 and 11.2%, respectively. Thus, we determined that both categories should be included in our analyses and not treated as missing data. Perceived eligibility for federal and state aid was derived from the question: “will you be qualified for federal and state loans?” For this question, the response options were “yes,” “no,” and “don’t know.” Similar to the prior variable, a large share of the sample (33.3%) answered “don’t know;” a percentage we did not believe should be excluded from our analyses. Therefore, we kept students who answered that they did not know rather than treating them as missing data. This nominal variable has three responses: “yes,” “no,” and “don’t know.”

Analysis

This investigation employed three types of statistical analyses: descriptive statistics, multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA), and factorial MANOVA. Descriptive statistics were calculated to present high school students’ demographic information and AECC levels (4-year public and private). MANOVA was used to examine differences among racial/ethnic groups on 4-year public and private AECC. Factorial MANOVA was employed to examine group differences in independent variables: race and financial-related factors that included importance of cost on college enrollment, knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA, perceived eligibility for federal and state aid, and the interactions between two independent variables on 4-year public and private AECC levels.

Results

AECC

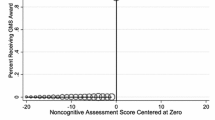

First, we analyzed how accurately students estimated the cost of 4-year public and private tuition and required fees. We calculated the percentages of students who overestimated and underestimated the actual cost of tuition (see Tables 2, 3). It was found that 81.9% of students overestimated and 18.1% underestimated the cost of 4-year public tuition (M = 10,050.34, SD = 11,449.78), and 64.6% of students overestimated and 35.4% underestimated the cost of 4-year private tuition (M = 5807.20, SD = 16,005.31). In other words, on average, students overestimated the cost of 4-year public tuition by $10,050.34 and overestimated the cost of 4-year private tuition by $5807.20.

Analyses of the levels of absolute-deviation-continuous AECC indicated that the mean 4-year public value was 136.89 (SD = 123.40), which was higher (i.e., less accurate) than the 4-year private AECC value of 57.00 (SD = 38.88). The skewness and kurtosis indicated normal distribution for absolute-deviation-continuous AECC for both 4-year public and private tuition. Positive values of skewness in raw AECC indicate that both public and private estimates had distributions with a long tail to the right (overestimate), and students overwhelmingly overestimated 4-year public (skewness = .87) compared to private (skewness = .25) college costs.

Race/Ethnicity on AECC

There was a significant difference among racial/ethnic groups on 4-year public and private AECC levels, F (8, 16,170.00) = 8.95, p < .001. Bonferreni post hoc test was conducted to identify exactly where group differences existed in each follow-up ANOVA. It was found that White and Asian students estimated 4-year public tuition and fees significantly better compared to Black and Hispanic students. On the other hand, Whites more accurately estimated the cost of 4-year private tuition and fees compared to Asian, Black, and Hispanic students (see Tables 4, 5). Now that we have established that racial/ethnic differences on AECC existed, the next section will further examine how AECC levels differed based on race/ethnicity and college financial-related variables selected for this study.

Race/Ethnicity and College Financial-Related Variables on AECC

Importance of Cost on Enrollment

High school students’ 4-year public and private AECC significantly differed based on race/ethnicity, F (8, 15,810.00) = 3.97, p < .001, but did not differ based on their perception of the importance of cost on college enrollment. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between race/ethnicity and importance of cost on students’ college enrollment on 4-year public and private AECC levels, F (16, 15,810.00) = 1.66, p < .05. In other words, 4-year public and private AECC significantly varied among racial/ethnic groups, and these differences were affected by students’ perception about the importance of the cost of college on enrollment. ANOVA was used to follow up MANOVA, and post hoc tests found that White and Asian students predicted 4-year public tuition and fees significantly more accurately than Black and Hispanic students, while White students estimated 4-year private tuition significantly more precisely than Asian, Black, and Hispanic students. Moreover, Asian students who did not believe the cost of college was relative to their college enrollment estimated 4-year public AECC most accurately among all combinations of race/ethnicity and importance of cost on college enrollment. On the other hand, Black students who did not consider cost of college to be important in relation to college enrollment estimated 4-year public tuition and fees least accurately compared to all other possible groups (see Tables 6, 7).

Knowledge of and Intent to Complete FAFSA

There was a significant group difference in race/ethnicity for 4-year public and private AECC, F (8, 15,140.00) = 6.65, p < .001. Although AECC did not differ significantly based on students’ knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA, there was a significant interaction between race/ethnicity and students’ knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA on 4-year public and private AECC levels, F (8, 15,140.00) = 1.54, p < .05. This indicated that 4-year public and private AECC significantly varied among racial/ethnic groups, and these differences were affected by knowledge of and intent to complete FAFSA. The results of follow-up ANOVA indicated that White and Asian students estimated 4-year public tuition and fees significantly more accurately than Black and Hispanic students. White students, at the same time, estimated 4-year private tuition and fees significantly more accurately than Asian, Black, and Hispanic students. Although MANOVA indicated a significant interaction effect, follow-up ANOVA did not find any significant interactions for either 4-year public or private AECC levels (see Table 8). Interestingly, a large percentage of respondents, 44.1%, were not familiar with what the FAFSA was. In other words, close to half of the 11th grade respondents were unaware of the FAFSA.

Eligibility for Federal and State Aid

High school students’ 4-year public and private AECC levels significantly differed based on race/ethnicity, F (8, 16,020.00) = 9.15, p < .001, and based on eligibility for federal and state financial aid, F (4, 16,020.00) = 2.68, p < .05. There was no significant interaction between these variables. Further, Bonferreni post hoc test in ANOVA found that White and Asian students estimated 4-year public tuition and fees significantly more accurately compared to Black and Hispanic students, and for private AECC, White students estimated the cost of college significantly more accurately than Asian, Black, Hispanic, and Other students. Lastly, we found students who believed they would be eligible for federal or state aid estimated 4-year public tuition and fees significantly more accurately than students who did not describe themselves as eligible for aid (see Tables 9, 10).

Limitations

The use of secondary data can be limiting since the researchers did not have the ability to influence the questions asked and correct terminology used in the questionnaire. For example, the HSLS:09 questionnaire asked respondents: “for which types of financial aid do you think you [will/would] qualify?” One of the response options for participants was “federal or state loans.” This statement option is limiting since not all states offer loans to students who enroll in postsecondary education, and the wording excludes grants offered by federal and state governments. Also, the examination of tuition levels is challenging given the large variability that may exist across public (even within the same state; e.g., California State University Long Beach versus University of California Los Angeles) and private postsecondary education institutions. Another limitation, also related to tuition levels, is that it was unclear which 4-year public and private postsecondary education institutions students were thinking of when estimating the cost of tuition and fees. If that information were available and used to calculate AECC, it could enhance the precision of students’ AECC levels. Finally, this research was based on the premise that students’ knowledge of, and accuracy of estimating, college costs influences their postsecondary education enrollment decisions. Unfortunately, there is limited empirical research to help support this premise. However, given the novelty of AECC, this investigation is a foundation for establishing AECC in the academic literature.

Discussion

This study presented a new methodological approach to calculate AECC, absolute-deviation-continuous. From a theoretical perspective, the absolute-deviation-continuous method is a more comprehensive approach compared to the most commonly used range-categorization method. Examining AECC using absolute-deviation-continuous, we argued, more accurately reflects how precisely (or imprecisely) students estimate the cost of college. The use of absolute-deviation-continuous prevents (a) the placement of students into arbitrary categorical groups (e.g., within a dollar value or percentage range), (b) the concerns associated with proximity (i.e., just beyond a specific range might be classified differently), and (c) the differential treatment of students who are equally inaccurate (e.g., underestimate or overestimate the cost of college by $100).

This investigation supports prior research (e.g., Antonio and Bersola 2004; Avery and Kane 2004; Horn et al. 2003; Merchant 2004; Mintrop et al. 2004; Turner et al. 2004) that found high school students are unaware of the cost of tuition and fees. We discovered that 11th grade students significantly overestimated the cost of 4-year public and private tuition and fees. On average, students overestimated the costs of 4-year public by $10,050.34 and private by $5807.20. This inability to accurately estimate the cost of college can likely be traced to “underlying information constraints” (Scott-Clayton 2012) experienced by high school students in relation to college financial awareness (George-Jackson and Jones Gast 2015). Some possible information constraints may be attributed to family unfamiliarity with the cost of college (Grodsky and Jones 2007; Horn et al. 2003; Ikenberry and Hartle 1998), colleges failing to adequately disseminate college cost information to high school students (Zarate and Pachon 2006), or high school students neglecting to investigate this information early in their college choice process (Horn et al. 2003). Further, students’ inaccuracy in estimating the cost of college may also point to the incredibly complex tuition structure that exists in the US postsecondary system (George-Jackson and Jones Gast 2015; Morphew 2007). If students are to have a realistic understanding of the cost of college, they need to comprehend tuition differences such as: in-state/out-of-state university, in-state/out-of-state college, in-district/out-of-district community college, and the thousands of private postsecondary education institutions in the nation. This might be a rather daunting and unrealistic expectation to have of high school students who are juggling the other elements that comprise the college choice process.

Also, students’ substantial overestimation of the cost of 4-year public tuition likely points to their limited knowledge in relation to the significant price differentials that exist between in-state public and private tuition levels. Sacerdote (2004) and Scott-Clayton (2012) hypothesized that students may use the higher-priced private tuition costs as a guide in their estimation of the cost of college, including that of 4-year public institutions. The relatively new field of neuroeconomics, which uses neuroscientific methods to analyze economically relevant brain processes (Kenning and Plassmann 2005; Sanfey et al. 2006), may help uncover how private college costs are driving students’ understanding of the cost of college. The overestimation that students tend to make in approximating 4-year public tuition is potentially troubling since prior studies inform us that the cost of college is an important factor that students consider during their college choice process (De la Rosa 2006; Greenfield 2015; Hahn and Price 2008; Perna and Titus 2005; St. John et al. 2005; Zarate and Pachon 2006). In other words, if high school students perceive higher education is too expensive, this may dampen their postsecondary education enrollment (Hahn and Price 2008).

Perna (2006b) discussed how high school students tended to wait until late in their college choice process to examine the cost of college—often waiting until late into 12th grade. The findings from our study support this notion. While students delaying until the 12th grade to comprehensively consider the cost of college might keep college options available to many students, it may also be limiting as it may refrain students and their families from preparing financially for costs associated with postsecondary education attendance. This may particularly disadvantage families of color who are less likely to financially plan for college (Hillman et al. 2015). Furthermore, financial aid processes, perhaps most notably FAFSA, have not incentivized students and their families to have conversations about financing postsecondary education until late in the college choice process. Students are not able to file their FAFSA until a few months before they are scheduled to begin college (Kelchen and Goldrick-Rab 2015; Scott-Clayton 2012). Indeed, high school students must often apply to colleges and universities without an understanding of their particular aid eligibility. It is for this reason that several scholars have recommended the use of prior–prior year (i.e., year-old rather than most recent) family financial information to make aid determinations (Cannon and Goldrick-Rab 2016; Dynarski and Wiederspan 2012; National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators 2013; Scott-Clayton 2012). The use of prior–prior financial data, which is scheduled to launch during the 2017–2018 FAFSA award cycle, could encourage families to have conversations earlier in the college choice process about the cost and financing of college.

In this study, differences in students’ AECC were documented along racial/ethnic characteristics. In general, it was found that Whites were more likely to accurately estimate the cost of 4-year public and private college while Asian students were most accurate in estimating the cost of 4-year public. On the other hand, Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to inaccurately estimate the cost of 4-year public and private tuition and fees. These findings are especially worrisome because students of color are more likely to have parents who did not attend college and/or with limited levels of college knowledge (Perna 2006b; Tierney and Auerbach 2005) and parents who depend on high school staff to provide college choice information (Cabrera and La Nasa 2001; Ceja 2006; Perna 2006a). Also, students of color are more likely to be enrolled in school districts with higher student-to-counselor ratios, which make it even more challenging to provide information about the cost of college to these students (George-Jackson and Jones Gast 2015; McDonough 2005). This is disconcerting since studies (e.g., Antonio and Bersola 2004; Horn et al. 2003) found that high school students who had conversations with counselors tended to have stronger AECC levels. Thus, if students of color are unfamiliar with the actual cost of college, especially at public institutions that tend to be more affordable, this may lead them to believe college attendance is not financially feasible. These findings are of serious concern given the disproportionately lower enrollment rates of Blacks and Hispanics in postsecondary education (Kena et al. 2016). In other words, not understanding the actual cost of college may be further contributing to high school students’ college choice decisions (i.e., not applying to specific types of institutions or most problematic not enrolling in college).

A large percentage of respondents (44.1%) were not familiar with what the FAFSA was. This is a particularly troubling finding since federal, state, and institutional aid is almost entirely tied to students filing a FAFSA. Thus, if students are unaware with the FAFSA a mere 1 year before they are required to complete it, this may contribute to the billions of dollars eligible students fail to claim in financial assistance (Kofoed 2016). Likely in response to the large unfamiliarity with FAFSA and high rates of students who fail to file a FAFSA, in recent years, the federal government has placed a significant amount of resources to increasing the knowledge and completion rates of FAFSA (Federal Student Aid, n.d.). Some initiatives include a Financial Aid Toolkit portal of information for counselors and availability of data on FAFSA completion rates by high school.

This study highlights the strong relation that exists between students’ AECC and their perception of eligibility for state and federal aid. Consequently, this points to some high school students who are quite savvy of elements related to college financial awareness. However, and most importantly, it also points to the fact that there are many students who are quite unfamiliar with aspects related to college financial awareness. Cunningham et al. (2008), in their examination of ways to expand postsecondary access to underserved students in Michigan, recommended the creation of a college financing literacy program for students and families that includes information about total costs of education, savings plan options, tax credit programs, student grants and loans, and expectations for financial assistance programs. The implementation of college financial literacy programs such as these can begin to address the information gaps that exist, primarily for populations of color, in relation to students obtaining information about the cost of, and aid programs to help fund, their postsecondary education (George-Jackson and Jones Gast 2015).

Implications

The current study is a starting point for a discussion of AECC and identifies several areas for further study. First, with the establishment of the absolute-deviation-continuous AECC methodological approach, it is imperative to further analyze this construct along other areas related to students’ college access. For example, utilizing absolute-deviation-continuous AECC to examine factors beyond race/ethnicity and college financial-related factors and in areas such as the role of high school environments and parents in shaping students’ AECC. Also, it would be interesting to analyze the relationship between students’ AECC and their postsecondary education enrollment decisions (e.g., enroll versus not enroll, public versus private, 2-year versus 4-year institution).

Eleventh grade students’ inability to accurately estimate the cost of college seems to point to students examining the cost of college later in their college choice process. Since financial decisions seem to be made later in the college choice process, it may be too late for students and their families to make informed financial decisions around college selection. Thus, it is necessary to further investigate students who are making later college choice decisions and the effect this has on several aspects related to their college financial planning (e.g., AECC levels, knowledge of FAFSA, eligibility for federal and state aid).

Information related to the actual cost of college, especially that of 4-year public postsecondary education institutions, does not appear to be reaching 11th grade students. More needs to be understood about the role of guidance counselors, contribution of higher education outreach efforts, and involvement of community-based organizations (CBOs) in disseminating information about the cost of college. This investigation supports the notion that college finance literacy dissemination efforts are not particularly strong (De La Rosa 2006). Thus, more needs to be understood about why high school students are not getting this information and how more effective dissemination tactics can be implemented (George-Jackson and Jones Gast 2015).

We identified several facets of the cost of college that practitioners at the K-12 and higher education systems and CBOs should consider. Perhaps most importantly, this work identifies specific demographic groups who are less likely to accurately estimate the cost of college. Thus, it would be important for K-12, higher education, and CBO staff to partner to target these specific groups in an effort to inform them of the costs associated with college. Also, dissemination of this information should not wait until the 11th or 12th grade—instead such efforts should begin much earlier in an effort to equip students with necessary information about college enrollment.

Notes

These researchers also conducted analysis at the 15 and 50% range levels.

References

Addo, F. R., Houle, J. N., & Simon, D. (2016). Young, black, and (still) in the red: Parental wealth, race, and student loan debt. Race and Social Problems, 8(1), 64–76.

Antonio, A. L., & Bersola, S. H. (2004). Working toward K-16 coherence in California. In M. Kirst & A. Venezia (Eds.), From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education (pp. 31–76). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Avery, C., & Kane, T. J. (2004). Student perceptions of college opportunities. The Boston COACH program. In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 355–394). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Banerjee, S., & Iglewicz, B. (2007). A simple univariate outlier identification procedure designed for large samples. Communications in Statistics: Simulation and Computation, 36(2), 249–263.

Bell, A. D., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., & Perna, L. W. (2009). College knowledge of 9th and 11th grade students: Variation by school and state context. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(6), 663–685.

Black, S. E., & Sufi, A. (2002). Who goes to college? Differential enrollment by race and family background (No. w9310). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: http://www.nber.org/papers/w9310

Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., & McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Bueschel, A. C., & Venezia, A. (2004). Oregon’s K-16 reforms: A blueprint for change? In M. Kirst & A. Venezia (Eds.), From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education (pp. 151–182). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cabrera, A. F., & La Nasa, S. M. (2001). On the path to college: Three critical tasks facing America’s disadvantaged. Research in Higher Education, 42(2), 119–149.

Cannon, R, & Goldrick-Rab, S. (2016). Too late? Too little: The timing of financial aid applications. Retrieved from http://wihopelab.com/publications/Timing-Financial-Aid-Applications.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., & Rose, S. J. (2003). Socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and selective college admissions. Retrieved from Century Foundation website: https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/app/uploads/2003/03/31010722/tcf-carnrose-2.pdf

Castillo, L. G., & Hill, R. D. (2004). Predictors of distress in Chicana college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 32(4), 234–248.

Castillo, L. G., Lopez-Arenas, A., & Saldivar, I. M. (2010). The influence of acculturation and enculturation on Mexican American high school students’ decision to apply to college. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 38(2), 88–98.

Ceja, M. (2006). Understanding the role of parents and siblings as information sources in the college choice process of Chicana students. Journal of College Student Development, 47(1), 87–104.

Crowther, T., Lykins, D., & Spohn, K. (1992). Report of the appalachian access and success project to the Ohio Board of Regents. Retrieved from http://www.oache.org/downloads/accessstudy.php

Cunningham, A. F., Erisman, W., & Looney, S. M. (2008). Higher education in Michigan: Overcoming challenges to expand access. Retrieved from the Institute for Higher Education Policy website: http://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/pubs/higher_education_in_michigan.pdf

De La Rosa, M. L. (2006). Is opportunity knocking? Low-income students’ perceptions of college and financial aid. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(12), 1670–1686.

Deming, D., & Dynarski, S. (2010). College aid. Targeting investments in children: Fighting poverty when resources are limited (pp. 283–302). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Dynarski, S. (2000). Hope for whom? Financial aid for the middle class and its impact on college attendance (No. w7756). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: http://www.nber.org/papers/w7756.pdf

Dynarski, S., & Wiederspan, M. (2012). Student aid simplification: Looking back and looking ahead (No. w17834). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17834.pdf

Engberg, M. E., & Wolniak, G. C. (2009). Navigating disparate pathways to college: Examining the conditional effects of race on enrollment decisions. Teachers College Record, 111(9), 2255–2279.

Federal Student Aid. (n.d.). FAFSA completion by high school. Retrieved from https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/about/data-center/student/application-volume/fafsa-completion-high-school

Flores, S. M., & Park, T. J. (2013). Race, ethnicity, and college success examining the continued significance of the minority-serving institution. Educational Researcher, 42(3), 115–128.

George-Jackson, C., & Jones Gast, M. (2015). Addressing information gaps: Disparities in financial awareness and preparedness on the road to college. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 44(3), 202–234.

Greenfield, J. S. (2015). Challenges and opportunities in the pursuit of college finance literacy. The High School Journal, 98(4), 316–336.

Grodsky, E., & Jones, M. T. (2007). Real and imagined barriers to college entry: Perceptions of cost. Social Science Research, 36(2), 745–766.

Hahn, R. D., & Price, D. (2008). Promise lost: College-qualified students who don’t enroll in college. Retrieved from http://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/pubs/promiselostcollegequalrpt.pdf

Heller, D. E. (1997). Student price response in higher education: An update to Leslie and Brinkman. Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 624–659.

Heller, D. E. (1999). The effects of tuition and state financial aid on public college enrollment. The Review of Higher Education, 23(1), 65–89.

Heller, D. E. (2006). State support of higher education: Past, present, and future. In D. M. Priest & E. P. St. John (Eds.), Privatization and public universities (pp. 11–37). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University.

Hillman, N., Gast, M. J., & George-Jackson, C. (2015). When to begin? Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differences in financial planning, preparing, and saving for college. Teachers College Record, 117(8), 1–28.

Horn, L., Chen, X., & Chapman, C. (2003). Getting ready to pay for college: What students and their parents know about the cost of college tuition and what they are doing to find out. Washington, DC: Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Hu, S. (2010). Scholarship awards, college choice, and student engagement in college activities: A study of high-achieving low-income students of color. Journal of College Student Development, 51(2), 150–161.

Ikenberry, S., & Hartle, T. (1998). Too little knowledge is a dangerous thing: What the public thinks and knows about paying for college. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Immerwahr, J. (2003). With diploma in hand: Hispanic high school seniors talk about their future. Retrieved from http://www.highereducation.org/reports/hispanic/hispanic.shtml

Kane, T. J. (1994). College entry by Blacks since 1970: The role of college costs, family background, and the returns to education. Journal of Political Economy, 102(5), 878–911.

Kantrowitz, M. (2011, September 2). The distribution of grants and scholarships by race. FinAid.org.

Kelchen, R., & Goldrick-Rab, S. (2015). Accelerating college knowledge: A fiscal analysis of a targeted early commitment Pell Grant program. The Journal of Higher Education, 86(2), 199–232.

Kena, G., Hussar, W., McFarland, J., de Brey, C., Musu-Gillette, L., & Dunlop Velez, E. (2016). The condition of education 2016 (NCES 2016-144). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch

Kenning, P., & Plassmann, H. (2005). Neuroeconomics: An overview from an economic perspective. Brain Research Bulletin, 67(2005), 343–354.

Kim, D. (2004). The effect of financial aid on students’ college choice: Differences by racial groups. Research in Higher Education, 45(1), 43–70.

Kim, J. (2012). Exploring the relationship between state financial aid policy and postsecondary enrollment choices: A focus on income and race differences. Research in Higher Education, 53(2), 123–151.

Kim, J., DesJardins, S. L., & McCall, B. P. (2009). Exploring the effects of student expectations about financial aid on postsecondary choice: A focus on income and racial/ethnic differences. Research in Higher Education, 50(8), 741–774.

Kofoed, M. S. (2016). To apply or not to apply: FAFSA completion and financial aid gaps. Research in Higher Education, Online First, 1–39.

Leslie, L. L., & Brinkman, P. T. (1987). Student price response in higher education: The student demand studies. Journal of Higher Education, 58(2), 181–204.

Linsenmeier, D. M., Rosen, H. S., & Rouse, C. E. (2006). Financial aid packages and college enrollment decisions: An econometric case study. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(1), 126–145.

Long, B. T. (2004). The impact of federal tax credits for higher education expenses. In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 101–168). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

McDonough, P. M. (2005). Counseling matters: Knowledge, assistance, and organizational commitment in college preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. B. Corwin, & J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach (pp. 69–87). Albany, NY: State University of New York.

McKinney, L., & Novak, H. (2015). FAFSA filing among first-year college students: Who files on time, who doesn’t, and why does it matter? Research in Higher Education, 56(1), 1–28.

McPherson, M. S., & Schapiro, M. O. (1991). Keeping college affordable: Government and educational opportunity. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Merchant, B. (2004). Roadblocks to effective K-16 reform in Illinois. In M. Kirst & A. Venezia (Eds.), From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education (pp. 115–150). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mintrop, H., Milton, T. H., Schmidtlein, F. A., & MacLellan, A. M. (2004). K-16 reform in Maryland: The first steps. In M. Kirst & A. Venezia (Eds.), From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education (pp. 220–251). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Morphew, C. C. (2007). Fixed-tuition pricing: A solution that may be worse than the problem. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 39(1), 34–39.

National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. (2013). A tale of two income years: Comparing prior–prior year and prior-year through pell grant awards. Retrieved from https://www.nasfaa.org/uploads/documents/ppy_report.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.a). Table 302.20: Percentage of recent high school completers enrolled in 2- and 4-year colleges, by race/ethnicity (1960 through 2015). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_302.20.asp?current=yes

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.b). Table 302.43: Percentage distribution of fall 2009 ninth-graders who had completed high school, by postsecondary enrollment status in fall 2013, and selected measures of their high school achievement and selected student characteristics (2013). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_302.43.asp?current=yes

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.c). Table 302.65. Percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity and state (2014). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_302.65.asp?current=yes

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.d.). Table 330.20. Average undergraduate tuition and fees and room and board rates charged for full-time students in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of institution and state or jurisdiction: 2011–12 and 2012–13. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_330.20.asp

Olson, L., & Rosenfeld, R. A. (1985). Parents, students, and knowledge of college costs. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 15(1), 42–55.

Orfield, G. (1992). Money, equity, and college access. Harvard Educational Review, 62(3), 337–373.

Paulsen, M. B., & St John, E. P. (2002). Social class and college costs: Examining the financial nexus between college choice and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(2), 189–236.

Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education and Penn Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy. (2015). Indicators of higher education equity in the United States, 45 year trend report, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Indicators_of_Higher_Education_Equity_in_the_US_45_Year_Trend_Report.pdf

Perna, L. W. (2000). Differences in the decision to enroll in college among African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites. Journal of Higher Education, 71(2), 117–141.

Perna, L. W. (2006a). Studying college access and choice: A proposed conceptual model. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 21, pp. 99–157). Dordrecht: Springer.

Perna, L. W. (2006b). Understanding the relationship between information about college prices and financial aid and students’ college-related behaviors. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(12), 1620–1635.

Perna, L. W. (2007). The sources of racial-ethnic group differences in college enrollment: A critical examination. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2007(133), 51–66.

Perna, L. W., & Steele, P. (2011). The role of context in understanding the contributions of financial aid to college opportunity. Teachers College Record, 113(5), 895–933.

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. A. (2005). The relationship between parental involvement as social capital and college enrollment: An examination of racial/ethnic group differences. Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 485–518.

Post, D. (1990). College-going decisions by Chicanos: The politics of misinformation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 12(2), 174–187.

Reardon, S. F., Baker, R., & Klasik, D. (2012). Race, income, and enrollment patterns in highly selective colleges, 1982–2004. Retrieved from Center for Education Policy Analysis, Stanford University website: http://cepa.stanford.edu/content/race-income-and-enrollmentpatterns-highly-selective-colleges-1982-2004

Sacerdote, B. (2004). Comment on: Student perceptions of college opportunities. The Boston COACH program. In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 355–394). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Sanfey, A. G., Loewenstein, G., McClure, S. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2006). Neuroeconomics: Cross-currents in research on decision-making. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(3), 108–116.

Scott-Clayton, J. (2012). Information constraints and financial aid policy (No. w17811). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w17811.pdf

Shires, M. A. (1995). The master plan revisited (again): Prospects for providing access to public undergraduate education in California (draft). Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED382151)

Solorzano, D. G., & Ornelas, A. (2002). A critical race analysis of advanced placement classes: A case of educational inequality. Journal of Latinos and Education, 1(4), 215–229.

St. John, E. P. (1990). Price response in enrollment decisions: An analysis of the high school and beyond sophomore cohort. Research in Higher Education, 31(2), 161–176.

St. John, E. P., Paulsen, M. B., & Carter, D. F. (2005). Diversity, college costs, and postsecondary opportunity: An examination of the college choice-persistence nexus for African Americans and Whites. Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 545–569.

Staniec, J. F. O. (2004). The effects of race, sex, and expected returns on the choice of college major. Eastern Economic Journal, 30(4), 549–562.

Tierney, W. G., & Auerbach, S. (2005). Toward developing an untapped resource: The role of families in college preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. B. Corwin, & J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach (pp. 29–48). Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Tomás Rivera Policy Institute. (2005). Perceptions of financial aid among California Latino youth. Retrieved from http://trpi.org/wp-content/uploads/archives/facts.pdf

Turner, C. S., Jones, L. M., & Hearn, J. C. (2004). Georgia’s P-16 reforms and the promise of a seamless system. In M. Kirst & A. Venezia (Eds.), From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education (pp. 183–219). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Venezia, A. (2004). K-16 turmoil in Texas. In M. Kirst & A. Venezia (Eds.), From high school to college: Improving opportunities for success in postsecondary education (pp. 77–114). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Zarate, M. E., & Pachon, H. P. (2006). Perceptions of college financial aid among California Latino youth: Executive summary. Retrieved from http://trpi.org/wp-content/uploads/archives/Financial_Aid_Surveyfinal6302006.pdf

Zhan, M., & Sherraden, M. (2011). Assets and liabilities, race/ethnicity, and children’s college education. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2168–2175.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nienhusser, H.K., Oshio, T. High School Students’ Accuracy in Estimating the Cost of College: A Proposed Methodological Approach and Differences Among Racial/Ethnic Groups and College Financial-Related Factors. Res High Educ 58, 723–745 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9447-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9447-1