Abstract

College affordability continues to be a top concern among prospective students, their families, and policy makers. Prior work has demonstrated that a significant share of prospective students forgo financial aid because they did not complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA); recent federal policy efforts have focused on supporting students and their families to successfully file the FAFSA. Despite the fact that students must refile the FAFSA every year to maintain their aid eligibility, there are many fewer efforts to help college students renew their financial aid each year. While prior research has documented the positive effect of financial aid on persistence, we are not aware of previous studies that have documented the rate at which freshman year financial aid recipients successfully refile the FAFSA, particularly students who are in good academic standing and appear well-poised to succeed in college. The goal of our paper is to address this gap in the literature by documenting the rates and patterns of FAFSA renewal. Using the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study, we find that roughly 16 % of freshmen Pell Grant recipients in good academic standing do not refile a FAFSA for their sophomore year. Even among Pell Grant recipients in good academic standing who return for sophomore year, nearly 10 % do not refile a FAFSA. Consequently, we estimate that these non-refilers are forfeiting $3,550 in federal student aid that they would have received upon successful FAFSA refiling. Failure to refile a FAFSA is strongly associated with students dropping out later in college and not earning a degree within six years. These results suggest that interventions designed to increase FAFSA refiling may be an effective way to improve college persistence for low-income students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

College affordability continues to be a top concern for prospective students, their families, and policy makers. Gaps in college completion have widened over time, with students from the top income quartile five times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree by age 25 than their peers from the bottom income quartile (Bailey and Dynarski 2011). A large body of research demonstrates that need-based financial aid can lead to substantial improvements in college entry, persistence, and success among low-income students (Castleman and Long, forthcoming; Deming and Dynarski 2009; Dynarski 2003; Kane 2003).

There are many sources of need-based financial aid (including grants, loans, and work-study programs) offered by the federal government, state governments, and individual colleges and universities. Eligibility for the vast majority of these financial aid programs is determined by the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which requires prospective students to provide detailed information on their (and their families’) income, assets, and family composition. Given the complexity of the current FAFSA filing process, researchers point to the FAFSA as a barrier to financial aid, and thus college access, for many low-income students (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2006; Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2008). One out of every ten first-year college students who would be eligible for need-based financial aid do not complete the FAFSA.Footnote 1 The complexity of the FAFSA may deter other academically-prepared but financially-needy students from entering college in the first place.

In response to these concerns, there has been substantial policy investment to help high school seniors and their families complete the FAFSA. These efforts include both governmental initiatives like the U.S. Department of Education FAFSA Completion Project, which provides school districts with real-time information about which students have completed the FAFSA, and privately-funded efforts like College Goal Sunday, which provides students in 34 states with free FAFSA completion assistance.Footnote 2 Results from a recent experiment show that providing lower-income families with FAFSA filing assistance can generate substantial improvements in both FAFSA filing and college entry, reinforcing that the FAFSA acts as a significant barrier to higher education (Bettinger et al. 2012). While there has been considerable attention to addressing this problem with high school seniors, there are many fewer efforts to help college students renew their financial aid each year, despite the fact that students need to refile their FAFSA on an annual basis to maintain their eligibility for federal, state, and institutional grant and loan aid.

Several prior papers investigate the relationship between need-based financial aid and persistence, and present consistent evidence that access to financial aid increases students’ persistence in college (Castleman and Long, forthcoming; Bettinger 2004; Dunlop 2013; Goldrick-Rab et al. 2012). However, we are not aware of any study that has documented the rate at which freshman year financial aid recipients successfully refile the FAFSA. The goal of our paper is to address this gap in the literature by documenting the extent of and patterns underlying FAFSA refiling among college students. Our analyses provide new descriptive evidence on whether application barriers associated with the FAFSA continue to negatively impact postsecondary outcomes among students who already completed the FAFSA, received financial aid, and successfully enrolled in college. These results can help inform future policy efforts to increase college affordability and success among economically-disadvantaged students.

We pay particular attention to the refiling behavior of Pell Grant recipients who are in good academic standing and whose stated expectation is to earn a degree; we view this population as having the most to gain from refiling the FAFSA. The failure of a substantial share of these students to refile would point to the need for greater policy attention to and intervention in this stage in the financial aid process. We use a nationally representative dataset, the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:04/09), to document the rate of FAFSA refiling among college freshmen and to investigate whether FAFSA refiling behavior varies by student academic and demographic characteristics. We then estimate the extent to which FAFSA refiling is associated with students’ college persistence and degree attainment after controlling for other factors correlated with student success.

To preview our results, we find that a substantial portion of freshmen Pell grant recipients with GPAs of 3.0 or higher do not refile a FAFSA (roughly 16 %). Conditional on returning for their sophomore year, one in ten of these higher-performing low-income students do not refile the FAFSA, and thus continue on in college without the financial aid they received freshman year. We estimate these non-refilers forfeit $1,930 in Pell grants, $1,620 in federal loan aid, and potentially thousands of dollars more in state and institutional grant aid.Footnote 3 Based on results from our regression analysis, students who do not refile are substantially less likely to persist in college or earn a degree within six years, compared with observationally similar students who do refile. The results of these analyses are informative for the design of financial aid policies as well as the potential importance of targeting resources to assist students with renewing their financial aid.

The remainder of our paper is structured as follows. In the “Literature Review” Section, we discuss traditional and behavioral economic theories that inform why freshmen financial aid recipients in good academic standing may not refile a FAFSA. In the “Data” Section, we describe the data we use in our analysis, and in the “Empirical Strategy” Section we discuss our methodology in detail. We present our results in the “Results” Section, and conclude with a discussion of the importance of our findings and direction for future research and policy in the “Discussion” Section.

Literature Review

Economists have traditionally modeled students’ decisions about whether to pursue higher education as a cost-benefit analysis (Becker 1964). However, the college access literature has documented several failures of this traditional decision-making model. For example, several studies have documented that students and families from disadvantaged backgrounds may struggle to estimate the cost of college tuition, and often overestimate what their actual tuition expenses would be (Avery and Kane 2004; Grodsky and Jones 2007; Horn et al. 2003).Footnote 4 Students may lack information on what aid is available or how to navigate the application processes. For example, of college freshmen who did not apply for aid in 2011–2012, 14 % did not because they had “no information on how to apply”, and 43 % did not because they thought they were ineligible.Footnote 5

A more recent line of work in behavioral economics demonstrates how behavioral responses may interfere with students making well-informed decisions about the higher education investments they pursue (Castleman 2015; Ross et al. 2013). Applying for college and completing the FAFSA requires students to access and digest a complex array of information, which requires a substantial investment of time and cognitive energy. Various studies also show that near-term costs or an inability to maintain attention on tasks can lead to individuals forgoing investments that they recognize are in their long-term interest to pursue, particularly when balancing multiple commitments in the present (e.g. Karlan et al. 2010; Thaler and Bernatzi 2004). In the context of postsecondary access and success, even small cost obstacles can prevent students from completing important stages of the college application process (Pallais 2015). Furthermore, even students who understand the financial benefits of completing the FAFSA may nevertheless procrastinate or put off indefinitely completing their aid application, or become too frustrated with the complexity of the process to complete all necessary steps (Bettinger et al. 2012; Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2006; Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2008).

These behavioral responses—the tendency to become frustrated with or procrastinate in the face of complex information; the tendency to favor near-term costs over longer-term investments; and limited attention—may help explain why a significant percentage of potential financial aid recipients do not apply. The tendency to procrastinate in the face of complexity may also explain why over half of students who do file the FAFSA miss state priority deadlines that would have qualified them for additional financial aid (King 2004; authors’ calculations from BPS:04/09).

Recognition of these informational and behavioral barriers has motivated various efforts to increase the visibility of financial aid programs and the assistance available to students to complete the FAFSA, as well as efforts to reduce the complexity of the aid process. These initiatives include the FAFSA completion efforts described in the introduction; the USDOE has also mandated that colleges post net price calculators on their websites to provide students with personalized estimates of the price their families would face at each institution. Researchers have also found that simple text-based nudges reminding students about required tasks for successful college matriculation can increase enrollment among college-intending high school graduates (Castleman and Page 2015).Footnote 6 , Footnote 7

While these behavioral theories help explain why financial aid-eligible students who enroll in college may not complete the FAFSA, to what extent do they predict that students who have already received financial aid for freshman year would struggle to refile their FAFSA for the subsequent year? After all, these students—perhaps with parental or school-based assistance—have already successfully navigated the FAFSA while they were in high school. In addition, students who filed a FAFSA the previous year are eligible to complete a “Renewal FAFSA” that auto-populates some of their responses.Footnote 8

On the other hand, many college freshmen are living away from their families for the first time, and thus may be less likely to receive parental assistance when applying for financial aid. College freshmen are also removed from the high school counselors and teachers who may have supported them through the college application process and encouraged them to apply for financial aid. Students who live off-campus or attend non-residential colleges are less likely to be connected to their college community or aware of financial aid renewal supports available on campus. Additionally, college freshmen may be particularly prone to attentional failure given the wide slate of new academic and social commitments that many students maintain. And while both the United States Department of Education and students’ college send email reminders about FAFSA re-filing, email is likely not the most effective channel through which to communicate with college students (Castleman 2015; Castleman and Page 2015).Footnote 9 Finally, students may lack accurate information regarding their continued eligibility for financial aid programs. For example, over half of previous Pell grant recipients who were enrolled in 2011–2012 did not re-apply for aid because they thought themselves ineligible.Footnote 10

Another possibility for why students do not refile the FAFSA is that they have information to indicate that they are unlikely to continue to receive financial aid, perhaps because they are not maintaining satisfactory academic progress (SAP) or because their family has experienced a significant change in income, and thus make informed decisions not to refile. During the period of our analyses, however, SAP requirements that can affect students’ aid eligibility were not binding until the end of the second year in college, so we would not expect first-year students to choose not to refile because they were not meeting SAP (Schudde and Scott-Clayton 2014). Furthermore, we demonstrate that refiling rates are substantial even for students with first-year GPAs over 3.0, who were not at risk for failing to meet SAP requirements. And while some students may have experienced family income fluctuations from year to year, the algorithm that is used to calculate families’ Expected Family Contribution is sufficiently complex and opaque that few students are likely to be able to precisely map how changes to family income would affect their add receipt. Among freshmen Pell recipients who did refile the FAFSA, 81 % are again awarded a Pell grant the following year, indicating that a substantial share of non-refilers may also be likely to maintain their eligibility. Finally, as we demonstrate in our results, 10 % of students who re-enroll in college do not refile the FAFSA. Taken collectively, these considerations suggest that informational and behavioral obstacles associated with the FAFSA likely contribute to students’ failure to refile, rather than students making fully-informed decisions not to refile the FAFSA.

Thus, there are a variety of informational and behavioral barriers that may prevent students—even those who had received aid freshman year, are in good academic standing, and who plan to return for sophomore year—from successfully refiling their FAFSA. Failure to renew financial aid may be particularly detrimental for lower-income students who intend to continue on in higher education, as research has shown that need-based financial aid significantly improves students’ persistence and success in college (Bettinger 2004; Castleman and Long, forthcoming; Dunlop 2013). Despite the potential importance of FAFSA refiling to students’ persistence in college, we are not aware of prior studies that document FAFSA renewal rates or investigate whether renewal rates vary by students’ academic or demographic background. Nor are we aware of any study that looks at how FAFSA refiling is associated with future academic outcomes. Our paper is therefore organized around the following research questions:

-

1.

At what rate do college freshmen financial aid recipients successfully refile their FAFSA?

-

2.

Does the probability that students refile their FAFSA vary based on student academic and demographic characteristics?

-

3.

How is successful FAFSA refiling associated with future academic outcomes, including persistence beyond freshmen year and degree attainment?

Data

For our analysis, we use data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:04/09), which is administered by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). BPS respondents are first-time students enrolled at postsecondary education institutions during the 2003–2004 academic year, and constitute a nationally-representative sample. BPS first interviews students at the end of their first year in college (Spring 2004), and then follows these respondents for six years. In addition to interviewing respondents again in 2006 and 2009, the BPS collects and compiles extensive student-level data from a variety of sources. These data include college entrance exam scores and survey responses from the ACT and College Board; financial aid information from the FAFSA; aid disbursement information from the National Student Loan Data System; and enrollment and degree attainment records from the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) for each institution attended during the study period that is covered by NSC.Footnote 11 The BPS also collects data on the characteristics of the institution(s) each respondent attended, including the sector (i.e. public, private non-profit, or private for-profit), level (i.e. 4-, 2-, or less-than-2-year), and published tuition and fees of each institution.Footnote 12 We supplement the BPS’s institutional information with admissions data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), an NCES-maintained database containing detailed information for all U.S. postsecondary education institutions that participate in Title IV financial aid programs.Footnote 13

Most variables used in our analysis come from students’ FAFSA records. For each FAFSA a student filed for the six academic years in the study, we observe the student’s responses to and outcomes from the FAFSA, including: measures of family income and assets, family composition, demographic information, the resulting Expected Family Contribution (EFC), and the federal financial aid the student is offered (i.e. Pell grants, Stafford loans). From the NSC data, we observe BPS respondents’ college enrollment status at each institution attended for every month between July 2003 through June 2009; we also observe degree or certificate receipt during the study period. This information gives us a near complete picture of BPS respondents’ college persistence and degree attainment up to six years after their initial enrollment. Additional variables of interest, such as college GPA and employment information, are available for the select survey years (2004, 2006, and 2009).

In all of our analyses, we first limit our sample to students who filed a FAFSA for their first year in college (2003–2004), expect to earn a degree (associate or bachelor’s), have not yet completed the degree they stated they intended to pursue, and were enrolled during April 2004. These restrictions focus our analyses on students who we can reasonably infer had the intention of continuing their education beyond the first year. We focus most of our analyses on students who received a Pell grant their first year, and thus have the most to benefit in terms of continued grant assistance from refiling a FAFSA.Footnote 14 For some of our analyses, we add a third restriction of students who earned a GPA of 3.0 or higher during their first year, as these students appear academically-poised to continue and succeed in college. Finally, we focus some of our analyses on students who re-enroll during the following academic year, 2004–2005.Footnote 15

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for five relevant samples of students: All freshmen FAFSA filers (column 1, n = 10,740); freshmen Pell grant recipients (column 2, n = 5050); freshman Pell Grant recipients who re-enrolled for sophomore year (column 3, n = 4370); freshmen Pell recipients who earned a 3.0 GPA or higher (column 4, n = 2840); and freshmen Pell recipients who earned a 3.0 GPA or higher and re-enrolled for sophomore year (column 5, n = 2500).Footnote 16 As expected, Pell recipients differ from the full sample of freshmen FAFSA filers on most measures. Pell recipients receive more need-based grant aid and borrow more in student loans, but receive fewer merit-based grant dollars. Pell recipients are more likely to be female or underrepresented minority (black or Hispanic), and less likely to be classified as dependent for financial aid purposes. Pell recipients score lower on college entrance exams and earn slightly lower GPAs as college freshmen. By construct, Pell recipients are of lower socio-economic status: their total household income is less than half that of the average college student, and they are more likely to be a first generation college student. Pell grant recipients are less likely to live on campus, and more likely to live on their own; they are also much more likely to have dependent children. Interestingly, even though Pell grant recipients are lower-income and have more financial need, Pell grant recipients are no more likely to work at an outside job or for a work-study program, and those who do work similar hours on average to the full sample of students. Pell grant recipients have a lower cost of attendance, largely due to the fact that Pell recipients are less likely to attend 4-year institutions and more likely to attend 2-year or less-than 2-year institutions. Pell grant recipients are significantly less likely to persist after their freshmen year or earn a bachelor’s degree within six years of initial enrollment. While these differences are attenuated upon conditioning on high freshmen GPAs (column 3), enrollment in sophomore year (column 4), or both high freshmen GPA and sophomore enrollment (column 5), we still observe significant gaps in persistence and degree attainment between these conditioned samples of Pell grant recipients and the full college freshmen population of FAFSA filers. The relatively low persistence and graduation rates of Pell recipients make this population a high priority for policy makers, which is one of the reasons we focus on Pell recipients in our analysis.

Empirical Strategy

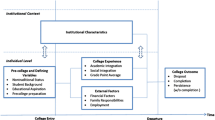

To address our first research question, we use the BPS to estimate the proportion of college freshmen who refile the FAFSA for the following academic year for the full sample, as well as sub-samples of interest based on freshman Pell grant receipt, freshmen GPA, and re-enrollment as a sophomore. Next, we perform two sets of regression analyses to address our research questions of: (1) how the probability of refiling a FAFSA varies by student and institution characteristics; and (2) the association between successful FAFSA refiling and future success in college. To investigate (1), we estimate a linear probability model in which the dependent variable is an indicator equal to one if the student did not refile a FAFSA for the next academic year (2004–2005), and zero if otherwise.Footnote 17 Specifically, we estimate the following equation:

X i is a vector of student characteristics, including demographics (gender, race, household income, and first generation college student status); academic achievement (SAT score, freshman year GPA)Footnote 18 ; financial aid information (dependency status, Pell grant award, other grant awards, loan borrowing, cost of attendance); employment status (has job outside of school, hours worked); household information (has dependent children, has spouse with an income); and living situation (lives on campus, lives with parents, or lives on own). Z s is a vector of institution characteristics, including level (i.e. 4-year, 2-year, or less-than 2-year); control (public, private non-profit, or private for-profit); and admission rate as a proxy for institutional quality. Together, X i and Z s contain all variables shown in Table 1 (with the exception of the outcome measures of subsequent enrollment and degree attainment). Each of these variables may be related to a student’s probability of refiling the FAFSA for various reasons. For example, some studies find that the demographic characteristics of race, gender, age, and income are significant predictors of FAFSA filing (Kantrowitz 2009; Kofoed 2015). These patterns may be explained, in part, by the differences in prospective students’ accuracy of information regarding college financial aid (Avery and Kane 2004; Horn et al. 2003; Oreopoulos and Dunn 2013) or access to the social capital provided by people in their families, neighborhoods, and friend circles familiar with the financial aid process (McDonough 1997; Nagaoka et al. 2009; Perna and Titus 2005; Tierney and Venegas 2006). We include variables describing students’ financial aid awards to test whether students with larger financial aid packages–and thus strong incentive to renew their aid—are more likely to refile. Our model also takes into account students’ differences in available time resources, by controlling for the number of hours the student spends working outside school and family obligations. Students who have more outside responsibilities, such as caring for children or working at an outside job, may have less time or cognitive energy toward the refiling the FAFSA (Castleman 2015; Castleman and Page, forthcoming; Mullainathan and Shafir 2013). Finally, we include institution characteristics as a predictor of refiling. Institutions vary substantially in the advising resources they provide to students, which likely significantly impacts refiling rates (Scott-Clayton 2015). ϵ i is the error term, which in addition to noise absorbs differences in refiling rates explained by unobservable characteristics, such as motivation and organizational skills.

We acknowledge that the decisions to refile and re-enroll are likely inter-related in a complex manner. Some proportion of the students who do not refile a FAFSA likely make this decision because they do not intend to re-enroll for the following academic year. At the same time, it is also likely that some students do not re-enroll because they did not refile a FAFSA and therefore did not receive the aid they needed to continue in college.Footnote 19 Unfortunately, given data and methodological limitations we cannot observe the direction of causation of this relationship. What we can do, however, is investigate patterns of FAFSA refiling (or failing to refile) among Pell Grant recipients who re-enroll for sophomore year. We therefore estimate a second set of linear probability models in which we restrict the sample to students who re-enrolled for their sophomore year. Because we are particularly interested in the refiling behavior of students who are academically well positioned to continue in college, we also estimate both sets of models for the sub-sample of students who earned a 3.0 GPA or higher during their freshman year in college.

To quantify the degree to which FAFSA refiling is associated with future outcomes, we estimate the following regression model:

where Outcome i is a measure of student \( i^{{\prime }} s \) academic success, and Fail to Refile i , X i and Z s are defined as above. We interpret the OLS estimate of the coefficient of interest, γ 1, as the difference in the probability of achieving Outcome i between students who refile versus those who do not refile the FAFSA, controlling for the host of covariates included in X i and Z s .Footnote 20 Our goal of including these covariates is to control for other observable predictors of academic success, especially those which are also be correlated with a student’s propensity to refile the FAFSA. Previous studies document that the demographic characteristics of race, gender, age, and income are predictors of college persistence and graduation (e.g. Bailey and Dynarski 2011; Turner 2004). As discussed above, research shows that financial aid is a determinant of college success. Several descriptive studies and a few recent causal studies shows that a student’s probability of graduating varies substantially by the type of college they attend (e.g. Cohodes and Goodman 2014; Goodman et al. 2003). While the link between outside work schedules and family obligations are less well documented, there is some evidence that these also influence college outcomes (Scott-Clayton 2011; Scott-Clayton and Minaya 2015) The outcomes we use as dependent variables in Eq. 2 are enrollment in subsequent years, associate degree (AA) attainment by June 2009, and bachelor degree (BA) attainment by June 2009.Footnote 21

Our regression model does not account for unobservable characteristics that are likely related to both students’ propensity to refile a FAFSA and ability succeed in college, such as motivation and organizational skills. For this reason, we do not interpret our estimates of Eq. 2 as the causal effects of not refiling a FAFSA, but instead as associations between failure to refile and student outcomes. However, we believe this analysis is still valuable to understand how the outcomes of observably-similar students diverge after the FAFSA refiling decision is made.

Results

Probability of Refilling the FAFSA

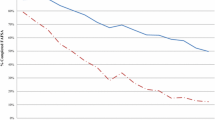

We first report raw means for the share of students that refile the FAFSA for our various samples of interest in Table 2. Panel A shows that among our sample of freshmen who initially applied for financial aid (n = 10,740), approximately three-fourths of students refile a FAFSA for the following year, while one-quarter do not refile. Refiling rates are higher for Pell grant recipients (83.4 %) and for Pell grant recipients who earn a 3.0 or higher freshman GPA (84.5 %). This result is intuitive as higher-income students generally do not qualify for need based aid and many do not borrow student loans, giving these higher-income students less incentive to refile a FAFSA. Still, one in six Pell grant recipients in our sample (who were enrolled through Spring 2004 and expect to earn a degree) did not refile a FAFSA; this is true even among those with good GPAs who appear well positioned to successfully continue their studies.

When we restrict our sample to students who did re-enroll for their second year (Panel B), we find that 10 % Pell grant recipients do not refile their FAFSA, which is true even of Pell grant recipients with good GPAs. Therefore, one out of ten lower-income students who are in good academic standing enter their second year of college without receiving the need-based grant aid for which they likely would have been eligible had they refiled their FAFSA.Footnote 22

Refiling Patterns by Student and Institutional Characteristics

We first explore how FAFSA refilers and non-refilers differ by comparing uncontrolled means of observable characteristics for both groups of students in Table 3. The characteristics of student who fail to refile suggest they are substantially more likely to be from populations that have been traditionally underrepresented in higher education.Footnote 23 Non-refilers are lower achieving academically, as demonstrated by their lower freshman GPAs and SAT scores. Non-refilers are less likely to be full-time students, and more likely to be female or underrepresented minorities. Non-refilers are less likely to be financially dependent or to come from households with larger incomes, and are more likely to be first-generation college students. Non-refilers are less likely to live on campus, and more likely to live on their own. Non-refilers are more likely to have dependent children or spouses with income. Non-refilers attend less expensive colleges with higher admission rates, are less likely to attend public or private non-profit institutions (compared to private for-profit institutions), are less likely to 4-year institutions, and are more likely to attend less-than 2-year institutions.Footnote 24 , Footnote 25

In Table 4, we formalize this analysis by estimating the association between FAFSA refiling and student and institution characteristics Eq. 1. Each column displays results from a separate regression with the following restrictions on our overall sample: all freshmen Pell recipients (column 1); Pell recipients who re-enrolled for their sophomore year (column 2); Pell recipients with freshmen GPAs of 3.0 or above (column 3); and Pell recipients with GPAs of 3.0 or above who re-enrolled sophomore year (column 4). In these regression models, we create categorical variables for freshman GPA, with the reference categories being GPA = 0–0.99. The reference category for institution control is for-profit institutions; the reference category for institution level is less-than 2-year institutions.

In column (1), we find that Pell recipients with strong GPAs (3.0 or higher) are 29.3 percentage points more likely to refile a FAFSA than those with the lowest GPAs (less than 1.0). This result translates to a predicted probability of refiling of 57 % for low GPA students, compared to 87 % for high GPA students.Footnote 26 Financial aid awards, measured as percent of the student’s cost of attendance (COA), also significantly predicts FAFSA refiling. To give an example of the interpretation of these coefficients: all else equal, a student whose Pell award covers 25 % of his COA is 8.9 percentage points less likely to refile compared to a student whose Pell award covers 75 % of his COA (predicted probabilities of failure to refile being 16 and 7.1 %, respectively). Even still, 14.8 % of Pell recipients whose awards are at the 75th percentile of the distribution of Pell as a share of COA fail to refile (8.4 % for students who re-enroll).Footnote 27

Institution level and control are also strong predictors of failure to refiling. For example, Pell recipients at 4-year institutions are 34.8 percentage points more likely to refile than students at less-than 2-year institutions and 8.3 percentage points more likely to refile than Pell recipients at 2-year institutions. Pell recipients at public and private non-profit institutions are 4 to 5 percentage points more likely to refile than Pell recipients at for-profit institutions. Other significant coefficients from column (1) show that underrepresented minorities are slightly (in magnitude and statistical significance) more likely to refile, and that working additional hours at an outside job is associated with a very small decrease in the probability of refiling (i.e. one additional hour of work is associated with a 0.2 percentage point decrease in the probability of refiling). When we restrict the sample to Pell recipients who re-enrolled for their second year for college (column 2), freshman GPA, Pell award, and institution type remain strong predictors of refiling. When we restrict the sample to Pell recipients who earn high GPAs their freshman year (columns 3 and 4), we find similar associations between refiling and institution level, although the associations with institution sector disappear.Footnote 28

Because institution level is consistently the strongest predictor of refiling, and because students who attend 4-, 2-, or less-than 2-year institutions are on average quite different from each other, we also estimate the associations between student characteristics and refiling separately for each institution level.Footnote 29 Table 5 shows our estimates from these models. The results in columns (1)–(3) correspond to models estimated with all Pell recipients (4-, 2-, and less-than 2-year, respectively); columns (4)–(6) correspond to models with the sample restricted to Pell recipients who re-enroll for sophomore. We find that the association between higher GPA and refiling is driven by students at 4- and 2-year institutions, as the coefficients on the GPA categories are not significant for the less-than 2-year sample.Footnote 30 Interestingly, while other forms of financial aid predict FAFSA refiling for students at 4-year institutions, Pell award is predictive of refiling only for students at 2-year institutions (columns 2 and 5). We believe this result is driven by the difference in costs of attendance across institution level: the average cost of attendance for Pell students at 4-year institutions in 2003–2004 was almost double that of Pell students at 2-year institutions. Institution sector is also a significant predictor of refiling only for students at 2-year institutions.

To emphasize the main takeaways of our analysis thus far, we find that institution type is the strongest predictor of FAFSA refiling, with Pell recipients at 4-year institutions being the most likely to refile (91 % predicted probability), followed by recipients at 2-year institutions (83 %) and less-than 2-year institutions (56 %). Freshman GPA is also a strong predictor of refiling, but only at 4- and 2-year institutions. Finally, students with larger financial aid awards are more likely to refile at 4- and 2-year institutions. This result suggests that students may be responding to their larger incentive to refile, or perhaps are more aware of their need to refile to maintain aid eligibility.

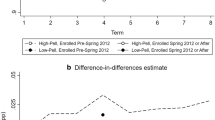

Association Between FAFSA Re-Filing and Longer-Term College Success

In Table 6, we present our estimates of Eq. 2, the associations between FAFSA re-filing during freshman year and longer-term college outcomes. We consider the relationship between FAFSA refiling and subsequent enrollment in columns 1 through 3, and the relationship between refiling and degree receipt in columns 4 and 5. Each grouping of rows corresponds to the coefficient estimate and standard error for a separate model using different samples of students: all freshman Pell recipients, freshman Pell recipients in good academic standing; freshman Pell recipients who returned for sophomore year; and freshman Pell recipients in good academic standing who returned for sophomore year. Consistently across samples, failing to refile the FAFSA is negatively associated with continuing in college and earning a degree. For instance, freshman year Pell recipients who do not refile are 25.2 percentage points less likely to be enrolled in what would be their junior year of college (column 2) and 3.1 percentage points less likely to earn a bachelor’s degree within six years (column 5) compared with observationally-similar students who do refile. When using the mean outcomes of the full sample of students as a benchmark, these effects translate to 36 and 12 % decreases in the probability of still being enrolled junior year and earning a degree, respectively. These associations between not refiling and future enrollment and AA degree attainment are similar when the sample is restricted to Pell recipients with GPAs 3.0 or higher and re-enroll although the estimates in column 5 for BA degree attainment decrease in magnitude and significance.

Because we found that institution level is a strong predictor of refiling, we next examine whether the longer-term outcomes of FAFSA non-refilers differ across institution level. We present the results of these models for the four samples of freshmen Pell Grant recipients in Table 7. While non-refilers have similar decreased probabilities of re-enrolling for sophomore year across institution levels, a pattern emerges that failure to refile the FAFSA is more strongly associated with negative longer-term outcomes for students at 2-year institutions.

Discussion

Prospective college students need to complete a lengthy and complicated application in order to qualify for financial aid for college. A large body of research has demonstrated that the complexity of this application may deter college-ready low-income students from successfully enrolling in college. Both the federal and state governments as well as non-profit and community-based organizations have invested substantial resources to assist students and their families to complete the FAFSA. Yet there has been considerably less attention to helping students successfully re-apply for financial aid once they are in college, despite the fact that they need to complete the same financial aid application each year to maintain grant and loan assistance. While there have been several prior studies demonstrating positive impacts of financial aid on college persistence and success, our paper is the first of which we are aware that documents rates and patterns of FAFSA refiling for a nationally-representative sample. This evidence is informative for policy efforts to increase college completion among economically disadvantaged students.

We find that a substantial share of freshman year Pell Grant recipients do not successfully refile the FAFSA. This is true for students in good academic standing and who return for sophomore year in college. Roughly 16 % of Pell recipients with strong freshman year GPAs do not refile, and approximately 10 % of these students who return for sophomore year do so without the financial aid the received for their first year in college. FAFSA refiling rates are particularly low among students who start out at 2-year institutions or less-than 2-year institutions.

An important question to consider is how much aid students may be foregoing by not refiling their FAFSA. The answer is difficult to know with precision, as we cannot observe the relevant household income information for students who do not provide refile the FAFSA. Instead, we predict forgone aid of non-refilers using the available data. Specifically, we first estimate a student-level regression model of observed sophomore-year federal aid on freshmen-year characteristics (the same set of control variables used in Eqs. 1 and 2 above), for the sample of students who did refile the FAFSA. We then use this estimated model to predict the sophomore-year federal aid awards for students who did not refile the FAFSA, and estimate that, had students refilled, they would have received, on average, $1,930 in Pell grant and $1,620 in federal loan awards. These estimates do not include the potential thousands of dollars in forgone state and institutional aid for non-refilers, as we do not observe sophomore-year aid receipts from these sources for any students in the BPS. While these estimates do not account for the potential cases where students choose not to refile because their household’s financial situation significantly improved during their freshmen year in college (and thus would no longer be eligible for need-based financial aid), as we argue earlier, these cases are infrequent and refilers are likely experience similar income and asset volatility to non-refilers.

We also find that among freshman Pell Grant recipients, failure to refile the FAFSA is strongly and negatively associated with staying in college or earning a degree. College sophomores who received a Pell Grant freshman year, had a first year cumulative GPA of at least 3.0, and did not refile the FAFSA were 14 percentage points less likely to still be enrolled junior year and 3.8 percentage points less likely to earn an associate’s degree within six years. When we focus on 2-year institutions, the relationship between failure to refile and academic success is more pronounced and significant. While we do not interpret these results as the causal effects of not refiling a FAFSA, they do suggest that refiling may be an important factor in students’ ability to persist to graduation.

One open question emerging from our paper is what share of students who fail to refile do so as an informed and careful decision rather than failing to refile as a result of the informational and behavioral obstacles we describe earlier. The results of our analyses lend further support to recent studies demonstrating that complex application processes and complicated procedural hurdles can deter academically-ready and college-intending students from successfully matriculating at all or from enrolling at institutions where they are well-positioned for success. Prior research shows, for instance, that college-bound high school seniors who would be eligible for need-based financial aid do not complete the FAFSA (Bettinger et al. 2012). High-achieving, low-income students do not apply to selective institutions with high graduation rates and low net costs where they appear admissible (Bowen et al. 2009; Hoxby and Avery 2013; Smith et al. 2013). College-intending high school graduates who have been accepted to and plan to intend college fail to matriculate as a result of financial and procedural hurdles they encounter in the summer after high school (Castleman et al. 2012; Castleman and Page 2014, 2015; Castleman et al. 2014). Our results indicate that complex processes such as refiling the FAFSA can continue to pose challenging hurdles for students, even those who have already successfully completed the FAFSA in high school and who have done well academically in college.

Consistent with prior work, one implication of our analyses is that the way information is delivered to students matters substantially. The US Department of Education and many colleges send email reminders to students to refile their FAFSA, but according to data from the Pew Center, only three percent of adolescents report exchanging emails on a daily basis (Lenhart 2012). Recent interventions demonstrate, on the other hand, that utilizing channels like text messaging that more effectively reach students and families can allow for more effective transmission of education-related information, and in turn, improved outcomes (Castleman and Page 2015; Bergman 2014; York and Loeb 2014). Given the information and behavioral barriers that may contribute to students failing to refile the FAFSA, students may similarly benefit from proactively-delivered prompts to renew their financial aid.

Castleman and Page (forthcoming) conducted a pilot experiment in which they randomly assigned college freshmen in Massachusetts a series of text message reminders to refile the FAFSA. The messages informed students about key deadlines and steps associated with FAFSA refiling and encouraged students to seek help with FAFSA refiling, either from the financial aid office at their college or from uAspire, a community-based organization focused on college affordability. The text campaign led to substantial increases in the probability that community college students persisted into sophomore year, though had no effect on sophomore-year persistence for students who started at 4-year institutions. The positive impacts for community college freshmen are consistent with our findings, which indicate that, after controlling for other characteristics, students at 2-year institutions are roughly half as likely to refile a FAFSA, and therefore may benefit from additional refiling-related reminders and the offer of assistance.Footnote 31 Due to data limitations, Castleman and Page were unable to observe whether students actually refiled their FAFSA, so one clear implication from both their experiment and our analyses is that additional research needs to be conducted to investigate whether personalized refiling messages combined with the offer of assistance leads to increases in successful refiling as well as persistence in college.

One clear appeal of these types of interventions is that they can be conducted at scale and at low cost relative to other more labor-intensive strategies to increase FAFSA re-filing. Colleges or universities could collect students’ cell numbers during the college application process and send students personalized refiling reminders in the spring of freshman year, or incorporate FAFSA refiling as part of their re-enrollment process. The Department of Education could collect cell phone numbers as part of the initial FAFSA application and send students similar text reminders to renew their aid. One important point to emphasize is that reminders alone may not be sufficient to increase refiling rates, given the complexity of the FAFSA. Therefore, colleges and universities or state and federal governments should investigate strategies that leverage personalized messaging technologies to connect students to FAFSA refiling assistance (either campus-based or remote) when they need help.

Over the last several years both the Obama Administration and Congress have been exploring proposals to simplify the federal financial aid application process. These proposals range from greatly simplifying the FAFSA or improving students’ ability to import much of the information they need for the FAFSA from their income tax returns, to allowing families to apply for federal financial aid based on income from two years’ prior. However, much of the debate around these proposals has centered around students who are filing the FAFSA for the first time. The Administration and Congress should consider additional policy levers for increasing the share of students that successfully renew their federal financial aid. One option would be to have students’ initial FAFSA automatically qualify them for multiple years of aid if their income and assets were sufficiently low. Another option would be to improve on existing systems that allow students to transfer in information from a prior year’s FAFSA submission.

In closing, financial aid remains an integral component of policy efforts to improve postsecondary outcomes for economically-disadvantaged students. In addition to ensuring that state and federal need-based aid programs remain sufficiently funded, policy efforts should continue to focus on supporting students through the complex financial aid application process—both when they first apply, and just as importantly, when they need to renew their aid.

Notes

For more information on these programs, see http://www.ed.gov/blog/2012/05/ed-announces-fafsa-completion-project-expansion/ and http://www.collegegoalsundayusa.org/pages/about.aspx.

For more detail on how we obtained these estimates of forgone aid, see “Discussion” Section.

Students only realize their true cost of attendance at a specific college after applying for admission and submitting the FAFSA for that institution.

Source: authors’ calculations from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study of 2012.

However, filing a Renewal FAFSA still requires applicants to fill in responses to the questions regarding income and assets, which are the most onerous to complete.

The U.S. Department of Education sends reminder emails to refile the FAFSA to students who: (1) have previously received a federal PIN; (2) whose name, date of birth, and social security number match with Social Security Administration records; and (3) provided a valid email address on their previously file FAFSA. Source: CollegeUp.org (http://blog.collegeup.org/tips-for-submitting-your-renewal-fafsa).

Source: authors’ calculation from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study of 2012.

In Fall 2003, the NSC enrollment data covered 86.5 percent of all postsecondary institutions. In Fall 2009, the coverage rate increased to 92 percent. Source: http://nscresearchcenter.org/workingwithourdata/.

Some students attended more than one institution during the 2003–2004 academic year, and some students switch institutions between their first and second year of college. Unless otherwise specified, we use the characteristics of the first institution a student attended during 2003–2004 in our analysis.

Using IPEDS, we calculate admissions rates by dividing total number of applicants by admitted students. These data are available for all institutions with no open admission policy.

The Federal Pell Grant Program awards needs-based grants to low-income students who attend participating postsecondary institutions. The award amount is determined by a student’s expected family contribution (EFC), which is calculated using the income and assets data from students FAFSA (source: http://www2.ed.gov/programs/fpg/index.html). In 2003–2004, students with EFCs less than or equal to $3,850; and Pell awards for full-time students ranged from $400 to $4,050.

We define “re-enroll” as enrolling at any postsecondary institution during the 2004–2005 academic year, not necessarily the institution that the student first attended in 2003–2004.

In accordance with IES reporting standards for restricted-use data, all sample sizes are rounded to the nearest ten.

Our results are robust to using probit or logistic regression models in place of the linear probability models.

For student who took the ACT, the BPS converts their ACT score to an SAT score for comparison; we use these converted ACT scores in our analysis. For students with no record of either entrance exam scores, we convert their missing value for SAT score to the sample mean, and include an indicator for missing entrance exam score in the regression.

While there is no deadline for filing the FAFSA and receiving a Pell grant, the majority of states and institutions have priority deadlines for their aid programs that are typically no later than April 1st, although some are as early as February 15th.

Our results are robust to several other specifications of Eq. 2, including logit, probit, and propensity score matching models.

We also estimate these models with cumulative GPA in 2006, certificate attainment by 2009, and on-time BA degree attainment (i.e. by June 2007). Across specifications, the associations between refiling and these outcomes are insignificant, and we omit these results from our tables.

For additional reference, Appendix Table 8 shows the refiling rates by institution-level.

Appendix Table 9 shows these means comparisons with the sample restricted to Pell recipients with good freshmen GPAs; the patterns we describe in this section are also consistent for that population.

For the subset of students who re-enroll, one question is whether failure to refile is associated with where students enroll for their sophomore year. However, we find that that refilers and non-refilers are similarly likely to remain at the same institution as they were enrolled for their first year (91 vs 90 %, respectively).

As expected, freshmen who fail to refile but remain enrolled are significantly less likely to file a FAFSA for the 2005–2006 academic year (17 vs 71 % of freshmen refilers).

To calculate these predicted probabilities, we set the rest of the control variables in the model at their means.

The 75th percentile corresponds to a Pell award that covers 32 % of a student’s cost of attendance.

Also significant in Table 4 are the coefficients for the missing variable indicator for cost of attendance (columns 1 and 2). This is likely due to the fact that cost of attendance variable is missing for those students who attend more than one institution during 2003–2004. This population of students represents a small percentage of our sample (5 %).

Appendix Table 10 shows the means of our analysis variables by institution level for freshmen Pell recipients. Compared to Pell recipients at 2-year and less-than 2-year institutions, Pell recipients at 4-year institutions are higher-achieving academically (as measured by their SAT scores), are less likely to be minority or first generation college students; are more likely to live on campus; are less likely to have dependent children; and are more likely to persist and graduate. Appendix Table 11 compares certain characteristics of institutions by level. Two-year and less-than two-year are much more likely to have open admission policies. Less-than two-year institutions are much more likely to have a continuous calendar system. Two-year and less-than two-year institutions share many of the same top degree or certificate programs; less-than two-year institutions also award degrees and certificates in vocational trades, such as “transportation and materials moving”, “construction trades”, and “precision production.”.

This pattern may be explained by grade inflation at less-than two-year institutions: 74 percent of students in our base Pell recipient sample who attended less-than two-year institutions earned a GPA or 3.0 or higher, compared to 50 % of students at four-year institutions and 55 % at two-year institutions. Similarly, an insufficient number of students at less-than two-year institutions earned a GPA below 1.0, thus necessitating the elimination of this category and making 1.00–1.99 the reference category for columns 3 and 6.

This statistic is based on the results from Table 6, which show that students at 2-year institutions are roughly 8 % points less likely to refile than students at four-year institutions.

References

Avery, C., & Kane, T. J. (2004). Student Perceptions of College Opportunities: The Boston COACH Program. In C.M.Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bailey, M. J., & Dynarski, S. M. (2011). Gains and gaps: Changing inequality in U.S. college entry and completion. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. New York: Russell Sage.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital. New York: Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bergman, P. (2014). Parent-child information frictions and human capital investment: Evidence from a field experiment. Working paper.

Bettinger, E. P. (2004). Is the finish line in sight? Financial aid’s impact on retention and graduation. In C.M.Hoxy (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Bettinger, E. P., Long, B. T., Oreopoulos, P., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2012). The role of application assistance and information in college decisions: results from the H&R block FAFSA experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3), 1205–1242.

Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. W., & McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Castleman, B. L. (2015). Prompts, personalization, and pay-offs: Strategies to improve the design and delivery of college financial aid information. In B. L. Casleman, S. Schwartz, & S. Baum (Eds.), Decision making for student success. New York: Routledge press.

Castleman, B. L., Arnold, K. D., & Wartman, K. L. (2012). Stemming the tide of summer melt: An experimental study of the effects of post-high school summer intervention on college enrollment. The Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5(1), 1–18.

Castleman, B. L. & Long, B. T. Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, forthcoming.

Castleman, B. L. & Page, L. C. Freshman year financial aid nudges: An experiment to increase FAFSA renewal and college persistence. Journal of Human Resources, forthcoming.

Castleman, B. L., & Page, L. C. (2014). A trickle or a torrent? Understanding the extent of summer melt among college-intending high school graduates. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 202–220.

Castleman, B. L., & Page, L. C. (2015). Summer nudging: Can personalized text messages and peer mentor outreach increase college going among low-income high school graduates? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 115, 144–160.

Castleman, B. L., Page, L. C., & Schooley, K. (2014). The forgotten summer: Does the offer of college counseling after high school mitigate summer melt among college-intending, low-income high school graduates? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(2), 320–344.

Cohodes, S., & Goodman, J. (2014). Merit aid, college quality and college completion: Massachusetts’ adam scholarship as an in-kind subsidy. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(4), 251–285.

Deming, D., & Dynarski, S. M. (2009). Into college, out of poverty? Policies to increase the postsecondary attainment of the poor. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15387. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dunlop, E. (2013). What do Stafford Loans actually buy you? The effect of Stafford Loan access on community college students. National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. Working Paper 94. http://www.caldercenter.org/publications/upload/erinWP.pdf.

Dynarski, S. M. (2003). Does aid matter? Measuring the effect of student aid on college attendance and completion. American Economic Review, 93(1), 279–288.

Dynarski, S. M., & Scott-Clayton J. E. (2006). The cost of complexity in federal student aid: Lessons from optimal tax theory and behavioral economics. National Tax Journal, 59(2), 319–356.

Dynarski, S. M., & Scott-Clayton, J. E. (2008). Complexity and targeting in federal student aid: A quantitative analysis. In J. Poterba (Ed.), Tax policy and the economy (Vol. 22). Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Dynarski, S. M., Scott-Clayton, J. E., & Wiederspan, M. (2013). Simplifying tax incentives and aid for college: progress and prospects. In J. Poterba (Ed.), Tax policy and the economy (Vol. 27). Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Goldrick-Rab, S., Harris, D., Kelchen, R., & Benson, J. (2012). Need-based financial aid and college persitence: Experimental evidence from Wisconsin. Wisconsin Scholars Longitudinal Study report. http://www.finaidstudy.org/documents/goldrick-rab%20harris%20benson%20kelchen.pdf.

Goodman, J., Hurwitz, M., & Smith, J. (2003). College access, initial college choice and degree completion. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 20996. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Grodsky, E., & Jones, M. T. (2007). Real and imagined barriers to college entry: perceptions of cost. Social Science Research, 36(2), 745–766.

Horn, L., Chen, X., & Chapman, C. (2003). Getting ready to pay for college: What students and their parents know about the cost of college tuition and what they are going to find out. Washington: U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics.

Hoxby, C. & Avery, C. (2013). The missing ‘one-offs’: The hidden supply of high-achieving, low- income students. Brookings papers on economic activity, economic studies program, the brookings institution, (Vol. 46:1 Spring), 1–65.

Kane, T. J. (2003). A quasi-experimental estimate of the impact of financial aid on college- going. National bureau of economic research working paper 9703. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kantrowitz, M. (2009). Analysis of why some students do not apply for financial aid. Finaid.org. Retrieved April 27, 2009 from http://www.finaid.org/educators/20090427 CharacteristicsOfNonApplicants.pdf.

Karlan, D., McConnell, M., Mullainathan, S., & Zinman, J. (2010). Getting to the top of mind: How reminders increase saving. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 16205.

Kelchen, R., & Jones, G. (2015). A simulation of pell grant awards using prior prior year financial data. Journal of Education Finance, 40(3), 253–272.

King, J. E. (2004). Missed opportunities: Students who do not apply for financial aid. Washington, D.C: American Council on Education, Center for Policy Analysis.

King, J. E. (2006). Missed Opportunities Revisited: Students who do not apply for financial aid. Washington, D.C: American Council on Education, Center for Policy Analysis.

Kofoed, M. S. (2015). To apply or not apply: FAFSA completion and financial aid gaps. Working paper.

Lenhart, A. (2012). Teens, smartphones & texting. Pew research center’s internet & American life project.

McDonough, P. M. (1997). Choosing colleges: How social class and schools structure opportunity. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: The new science of having less and how it defines our lives. New York: Henry Holt Time Books.

Nagaoka, J., Roderick, M., & Coca, V. (2009). Barriers to college attainment: lessons from chicago. Center for American progress; The consortium on Chicago school research at the University of Chicago.

Oreopoulos, P., & Dunn, R. (2013). Information and college access: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(1), 3–26.

Pallais, A. (2015). Small differences that matter: Mistakes in applying to college. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(2), 493–520.

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. (2005). The relationship between parental involvement as social capital and college enrollment: An examination of racial/ethnic group differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 485–518.

Ross, R., White, S., Wright, J. & Knapp, L. (2013). Using behavioral economics for postsecondary success. Ideas 42.

Schudde, L. & Scott-Clayton, J.E. (2014) Pell grants as performance-based aid? An examination of satisfactory academic progress requirements in the nation’s largest need-based aid program. A CAPSEE working paper.

Scott-Clayton, J. E. (2011). The causal effect of federal work-study participation: Quasi- experimental evidence from West Virginia. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(4), 506–527.

Scott-Clayton, J. E. (2015). The shapeless river: Does a lack of structure inhibit students’ progress community colleges? In B. L. Castleman, S. Schwartz, & S. Baum (Eds.), Decision making for student success. New York: Routledge Press.

Scott-Clayton, J.E. & Minaya, V. (2015) Should student employment be subsidized? Conditional counterfactuals and the outcome of work-study participation. National bureau of economic research working paper 20329. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Smith, J., Pender, M., & Howell, J. (2013). The full extent of academic undermatch. Economics of Education Review, 32(247), 261.

Stockwell, M. S., Kharbanda, E. O., Martinez, R. A., Vargas, C. Y., Vawdrewy, D. K., & Camargo, S. (2012). Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric and adolescent population: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 307(16), 1702–1708.

Thaler, R. H., & Bernatzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. The Journal of Political Economy, 112(1), 164–187.

Tierney, W. G., & Venegas, K. M. (2006). Fictive kin and social capital: The role of peer groups in applying and paying for college. The American Behavioral Scientist, 49(12), 1687–1702.

Turner, S. E. (2004). Going to College and Finishing College: Explaining Different Educational Outcomes. In C. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

York, B.N. & Loeb, S. (2014). One step at a time: The effects of an early literacy text messaging program for parents of preschoolers. National bureau of economic research working paper 20659. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for feedback from seminar participants at the University of Virginia and at the APPAM and ASHE conferences. This research was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant #R305B090002 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education. Any errors or omissions are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bird, K., Castleman, B.L. Here Today, Gone Tomorrow? Investigating Rates and Patterns of Financial Aid Renewal Among College Freshmen. Res High Educ 57, 395–422 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9390-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9390-y