Abstract

A prominent argument as to why countries sign “deep” preferential trade agreements (PTAs) is to foster global value chains (GVCs) operations. By exploiting a new dataset on the content of PTAs, this paper quantifies the positive impact of deep PTAs on GVC participation, mostly driven by value-added trade in intermediate rather than in final goods and services. On average, each additional policy areas increases the domestic and the foreign value added of intermediates by 0.48 and 0.38%. Deep PTAs facilitate integration in industries with higher levels of value added. Their content also matters for GVC integration by income group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

All members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have signed at least one preferential trade agreement (PTA).Footnote 1 The content of these agreements has changed over time as they now encompass a number of policy areas that extend beyond traditional trade policy (Hofmann et al. 2019). Through PTAs, member countries commit to cut their tariffs and undertake additional obligations in policy areas that are covered by the WTO, such as customs administration or contingent protection. But they increasingly break new grounds in policy domains that are not regulated by the WTO, such as investment and competition policy. This new generation of “deep” trade agreements is at the core of a number of policy and research debates, as economists try to assess these agreements’ economic effects and provide guidance on how to design and implement them efficiently.

This paper contributes to this broader debate on trade agreements by empirically investigating the relationship between deep trade agreements and global value chains (GVCs). Using a new dataset on the content of PTAs that has been developed by the World Bank, our analysis allows us to: (1) quantify the relationship between deep trade agreements and GVC integration among PTA partners; (2) disentangle the importance of specific sets of provisions in PTAs; and (3) shed light on the role of deep trade agreements in shaping the pattern of integration across countries with different levels of development.

Our key finding is that the depth of trade agreements contributes to increase GVC trade among parties. The relationship is stronger in higher value-added industries: Deeper trade arrangements may help countries to integrate in high value-added industries. We also find that for trade agreements between developed and developing countries, this effect is mostly driven by the presence of provisions that are currently outside the domain of the WTO and that deal with behind-the-border policies, such as investment and competition policy. For trade agreements between developing countries, the impact of trade agreements on GVC trade is mostly driven by the reduction of traditional trade barriers such as tariffs and other border measures.

The argument that the rise of deep trade agreements and the increasing importance of GVCs are related is not new and has been informally made in influential studies by Lawrence (1996), Baldwin (2011) and WTO (2011), among others. Intuitively, the unbundling of stages of production across borders creates new forms of cross-border policy spillovers and time-consistency problems. Deeper forms of integration may ameliorate these coordination and commitment problems, because they discipline those national policies that are needed for the smooth operation of GVCs.

Formal models of the relationship between GVCs and (Osnago et al. 2017) trade agreements are presented in Antràs and Staiger (2012) and Bickwit et al. (2018). A few studies have examined related questions from an empirical perspective: Orefice and Rocha (2014), Johnson and Noguera (2017), Osnago et al. (2017, 2019).Footnote 2 As compared with the current study, these papers either abstract from the depth of trade agreements (Johnson and Noguera 2017), or are based on a smaller database that has been developed by the WTO (WTO 2011) that covers only 100 agreements, or use different measures for GVC-related trade (Orefice and Rocha 2014; Osnago et al. 2017, 2019).Footnote 3

In the econometric analysis, we use a structural gravity model at the aggregate and sectoral levels to estimate the relationship between cross-border production linkages and the depth of PTAs. To control for selection bias that derives from the presence of zero trade flows, our estimations are performed with the use of a Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (PPML) model. PTA depth measures are based on the new World Bank dataset on the content of PTAs, which covers 260 agreements that were signed by around 180 countries between 1958 and 2015. This is the entire realm of PTAs that were in force and notified to the WTO as of December 2015.Footnote 4 We build several indicators of PTA depth that capture the scope and legal enforceability of trade agreements. Bilateral GVC integration is measured in two ways: value-added trade; and trade in parts and components.

Value-added trade comes from Wang et al. (2013) and is based on the World Input Output dataset (WIOD) for the years 1995–2011. Value added trade provides a more accurate measure of GVCs involvement. It also allows us to investigate the impact of deep trade agreements on both goods and services trade and across industries with different levels of value added.

The information on-value added trade, however, covers a limited sample of countries (40). In contrast, trade in parts and components records gross trade flows, which can be subject to double-counting, but has the advantage of being available for the full set of countries and years that are covered by the new dataset on PTAs. Having the whole sample of countries allows us to investigate how the effect of deep PTAs varies with the level of development of countries that are involved in an agreement. It also provides some insight as to whether certain types of provisions that are included in PTAs are more relevant for agreements between countries with different levels of development.

We first study how the depth of PTAs affects GVC integration in aggregate and for goods and services separately. We examine total domestic value added (DVA) in gross exports and foreign value added (FVA) in gross exports. The main finding is that deep PTAs are associated with increases in the domestic value-added content of exports—mainly through GVCs. Adding a provision to a PTA boosts the domestic value added of intermediate goods and services exports—forward GVC linkages—by 0.48%, while an additional provision in a PTA increases foreign value added of intermediate goods and services exports—backward GVC linkages—by 0.39%. We also find evidence that deep trade agreements are particularly significant to improve forward linkages into more complex GVCs—GVCs where exported intermediates cross borders two times or more—while we do not find a significant impact of deep trade agreements on domestic and foreign value added of final goods and services exports.

Estimations that we perform separately for services and goods show that the impact of deep trade agreements is usually higher for value-added trade in services as compared to value-added trade in goods. In addition, the positive impact of deep trade agreements on intermediates that cross the border more than once is significant only for exports in intermediate services: Agreements that extend beyond pure market access and include behind-the-border provisions are particularly important for services GVC integration.

We also analyse whether the impact of deep trade agreements on GVC integration is heterogeneous across industries. We estimate sectoral regressions with the addition of an interaction term between depth and the share of value added in overall production of a sector. The results suggest that deep trade agreements are particularly relevant for GVC integration in high value-added industries. These industries are usually services sectors, which are often characterized by non-tangible activities such as research and development or retail services, for which deeper commitments and beyond-the-border policies are important.

Next, we empirically explore potential heterogeneity in the effects of deep PTAs by splitting the provisions into two categories, which depend on their relationship with WTO rules.Footnote 5 “WTO+” provisions fall under the current mandate of the WTO and are already subject to some form of commitment in WTO agreements; “WTO-X” provisions, on the contrary, refer to policy obligations that are outside the current mandate of the WTO and relate to areas that are not yet regulated by the WTO. We focus on the larger sample of countries that is available for trade in parts and components to explore whether the impact of different provisions is heterogeneous across countries with different levels of development. The estimates suggest that WTO-X provisions are very important for GVC-related trade between North and South countries. On the other hand, WTO+ provisions are still relevant for trade among developing countries.

To address potential endogeneity, we include in our regressions a set of fixed effects that partially deals with the issue (Baier and Bergstrand 2007; Piermartini and Yotov 2016). As an alternative approach, a set of leads and lags of the variable that captures the depth of trade agreements are included in the regression. This allows us to control for the dynamic effect of the impact of deep trade agreements on GVC-related trade.

The results suggest that there is some anticipation effect of deep trade agreements, but this effect is limited to 1 year before the agreement enters into force. The positive trade effect of deep agreements persists after the first year, and it generally stabilizes over time. This is especially true for the domestic value added of intermediates. As to the dynamics for trade in parts and components, the results show that there are no anticipation effects but the impact of deep agreements persists after the entry into force of the agreements that involve North and South countries.

Finally, a concern is that in a world where production is fragmented across countries, GVC trade between two countries is affected not only by their trade agreements but also by the trade agreements that are signed by any country along the value chain (Noguera 2012). As deep agreements may have a stronger impact on bilateral GVC trade than do shallow agreements, it is well possible that the level of depth of preferential trade agreements that are signed by third countries along the supply chain could indirectly affect GVC-related trade between two countries. We build on the approach by Noguera (2012) to control for the indirect effect of deep trade agreements and find that the coefficients of the modified gravity regressions are larger than those of the standard gravity model, which confirms the existence of indirect effects of signing deep PTAs through third countries.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 discusses the data that are used in the paper. Section 3 presents the empirical analysis that focuses on the impact of PTA depth on GVC integration, while Sect. 4 focuses on the differential impact that different sets of provisions in deep trade agreements have on countries with different levels of development. Section 5 presents robustness tests. Concluding remarks follow.

2 Data

In this section, we take a first look at the data on the content of trade agreements and present the measures of PTA depth and GVC trade that are used in the analysis.

2.1 Deep Trade Agreements

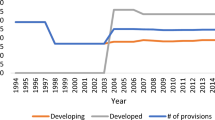

In the literature, the effects of PTAs on trade are generally estimated by including a dummy variable that is equal to one when two countries are involved in an agreement (Limão 2016). In our econometric analysis, we also estimate the coefficient of a dummy variable for PTAs; but we take a step forward by estimating the effects of deep trade agreements with the use of three new measures of depth. The data on the content of deep agreements come from a new database at the World Bank that covers 260 PTAs, which is the realm of preferential agreements that exclude partial scope agreements in force and were notified to the WTO up to the end of 2015 (Hofmann et al. 2019). The methodology is based on the work of Horn et al. (2010), which was also used in the World Trade Report 2011 (WTO 2011). The data provide information on two key aspects of the content of PTAs: (1) the policy areas that are covered in each agreement, which is based on a list of 52 policy areas; and (2) whether each provision is legally enforceable or not, based on an analysis of the legal language of the treaty text and the possibility of recourse to dispute settlement.Footnote 6

As a first measure of depth, we use the number of legally enforceable provisions that are included in an agreement from the World Bank database. While an imperfect metric, this is a logical first step to capture the level of depth of PTAs, as the extent of policy commitments depends on the number of areas that are covered by an agreement. Specifically, we define the variable \(TotalDepth_{ijt} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{k = 1}^{52} Prov_{ijt}^{k}\): the simple count of legally enforceable provisions (\(Prov_{ijt}^{k}\)) that are included in the agreement between country \(i\) and \(j\) at time \(t\).Footnote 7

An alternative measure of depth can be constructed on a subset of “core” border and behind-the-border provisions: those provisions that have a clear economic content, as opposed to other provisions that do not: e.g., cultural cooperation, anti-terrorism. Core provisions include: tariff liberalization for industrial and agriculture goods; technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures; export taxes and anti-dumping and countervailing measures; trade related intellectual property (TRIPs) and trade related investment measures (TRIMs); movement of capital; state-owned enterprises; state aid; competition policies; intellectual property rights (IPR); investment; public procurement; and services. The 18 “core” provisions are also those that are most often included in PTAs (Hofmann et al. 2019). We define the variable \(CoreDepth\) as the number of core provisions (\(Prov_{ijt}^{c}\)) that are included in the agreement between country \(i\) and \(j\) at time \(t\):\(CoreDepth_{ijt} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{c = 1}^{18} Prov_{ijt}^{c}\).

Finally, we use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of our dataset. PCA transforms the 52 provisions into a set of orthogonal variables: “components”. The first component is a weighted average of the provisions that take into account around 27% of the variation in the data.Footnote 8 The structure of the weights that are assigned to each provision in the first component suggests that the first component captures the “scope” of the agreement and it can be used as an alternative measure of depth.Footnote 9 In fact, the correlation between the first component and the number of provisions in a PTA is equal to 0.94. We then define \(PCADepth\) as the weighted average of provisions that use the coefficients of the first component as weights (\(\omega_{k}\)): \(PCADepth_{ijt} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{k = 1}^{52} \omega_{k} Prov_{ijt}^{k}\).

The database on the content of trade agreements is also useful to examine which type of provisions is more important for GVCs. To do this, we divide provisions into 2 categories following Horn et al. (2010): “WTO+” provisions fall under the current mandate of the WTO and are already subject to some form of commitment in WTO agreements, such as tariffs, customs, and anti-dumping. “WTO-X” provisions, on the contrary, refer to policy obligations that are outside of the current mandate of the WTO, such as investment and competition policy. We then split \(TotalDepth\) into two parts that capture how many legally enforceable WTO+ and WTO-X provisions are included in a PTA. The variables are defined as \(WTOplus_{ijt} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{p = 1}^{14} Prov_{ijt}^{p}\) and \(WTOextra_{ijt} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{x = 1}^{38} Prov_{ijt}^{x}\), where \(Prov_{ijt}^{p}\) are 14 WTO+ provisions and \(Prov_{ijt}^{x}\) are 38 WTO-X provisions that are included in an agreement between countries \(i\) and \(j\) in year \(t\).

2.2 Global Value Chains

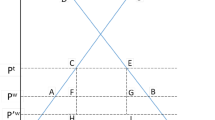

In our analysis, we use different datasets and measures to capture the intensity of GVC relationships between two countries: First, we use data from the World Input–Output Database (WIOD) and the decomposition of value added that was proposed by Wang et al. (2013) to measure bilateral value-added trade flows.Footnote 10 Specifically, Wang et al. (2013) decompose gross trade into several value-added components (see Fig. 1). Our first measure of interest is domestic value added (DVA). It simply measures the amount of value added by the exporting country that is contained in its exports: the sum of the first four components in the figure. While this is not a direct measure of GVCs, the comparisons of the results for this variable with our second variable of interest (discussed next) sheds light on the relationship between deep trade agreements and GVCs.

Source: Authors’ re-elaboration of Wang et al. (2013)

Decomposition of gross exports

The second variable of interest is value added in intermediates: It includes the value of exports that has been produced domestically, exported as an intermediate good, reprocessed by the importing countries, and then either directly absorbed there: component (2) in the figure; or further exported to third countries: component (3); or re-exported to the original country: component (4). We define a third variable from the sub-set of re-exported intermediates: components (3) and (4). Re-exported intermediates represent the most fragmented parts of a production process in which goods and services cross at least two borders before being eventually absorbed. These two variables capture the bilateral forward linkages between two countries.

We also use foreign value added in gross exports that can be further decomposed between final and intermediate goods and services: components (5) and (6). It measures all value that has not been produced domestically and that is contained in gross exports. This variable captures backward linkages. At this stage, the decomposition does not allow us to identify the country of origin of the foreign value and hence it is an imperfect measure of bilateral GVC linkages.Footnote 11

Second, for the analysis that is based on gross trade flows, we use trade in parts and components to proxy for global production sharing. There is no broadly accepted definition of trade in parts and components to which we can refer, so our classification builds on the existing literature (WTO 2011; Orefice and Rocha 2014). Specifically, for our analysis, we define as parts and components all non-fuel intermediates from the Broad Economic Categories (BEC) classification (codes 111, 121, 21, 22, 42, and 53), supplemented with unfinished textile products in division 65 of the SITC classification.

These various measures have advantages and disadvantages, which is the reason why we chose to employ a broader set of indicators rather than focusing on a single one. In particular, measures that are based on value-added trade are more precise as they us allow to deal directly with the problem of double-counting in gross trade data and account for the input–output relationships in production. WIOD data also have the advantage of covering trade in both goods and services. The data on (goods) trade in parts and components are available for a large set of countries and years,Footnote 12 thus allowing us to rely on a broader panel, which includes many more developing countries than does the WIOD.Footnote 13 However, the correlation between gross and value-added trade variables for the sub-sample of WIOD countries and years is large and ranges between 0.75 and 0.88 (see the first column of Table 1).

3 Depth of Trade Agreements and GVC Integration

In this section, we present the empirical strategy and the analysis of the impact of deep agreements on value-added trade. We also investigate whether the impact of deep trade agreements is heterogeneous for industries with high and low value added that is incorporated in their production.

3.1 Empirical Strategy

To assess the impact of deep agreements on GVC integration, we estimate the following structural gravity equation for the time period 1995–2011 with a Pseudo-Poisson Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimator. We use the PPML approach to deal with zeros in the dependent variables and to have a consistent estimate in the presence of heteroskedasticity. The regression equation is:

where \(GVCtrade_{ijt}\) is a measure of value-added trade between country \(i\) and \(j\) at time \(t\) and is captured either by different components of value-added trade or by gross trade in intermediates; \(Depth_{ijt}\) is one of the three measures of the depth of PTAs that were defined in Sect. 2a above; \(BIT_{ijt}\) controls for the presence of a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) between country \(i\) and country \(j\) at time \(t\)Footnote 14; \(PTA_{ijt}\) is a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 whenever there is a preferential trade agreement, either active or inactive, between the two countries at time \(t\)Footnote 15; and the \(\delta\)s are sets of country-pair, importing-country-time, and exporting-country-time fixed effects.Footnote 16 Sample statistics of the variables included in Eq. (1) are reported in Table 14.

It is important to note how the variables of depth have been constructed for inactive PTAs. In practice, there are two types of inactive PTAs: i) agreements that expired or that have been terminated (such as the first Yaounde convention or the Arusha convention); and ii) agreements that have been replaced by more recent agreements (such as the interim agreements that have been signed between the European Union and all the acceding countries). None of the inactive PTAs have been coded in Hofmann et al. (2019), and therefore there is no consistent information on their content. In this paper, we assume that the inactive PTAs in the first category were shallow, and we assigned a value of depth equal to 0. On the other hand, we assume that the PTAs that have been replaced by other agreements were similar to the newer PTAs. Thus, in our data, the depth of the replaced agreements is equal to the depth of the replacing agreement.Footnote 17

Our estimates might suffer from endogeneity that derives from omitted variables and simultaneity bias. Omitted variables bias arises when the error term is correlated with some unobservable country-specific policy variables—e.g. restrictive domestic policy regulation—which at the same time affect both GVC-related trade and the probability of forming a deep PTA. Reverse causality may arise from the fact that firms in country-pairs that are involved in GVCs may lobby for deeper trade agreements to secure supply of intermediates in partner countries and therefore to decrease the probability of trade diversion. The set of fixed effects that are included in the structural gravity estimation partially deals with both sources of endogeneity (Baier and Bergstrand 2007; Piermartini and Yotov 2016). As an alternative approach, a set of leads and lags of the variable that captures the depth of trade agreements are included in the regression and presented as a robustness check.

3.2 Baseline Results

Table 2 reports the coefficients of total depth, core depth, and PCA depth for the regressions that use DVA and FVA as dependent variables. All coefficients of depth are positive and significant: Deep PTAs have a positive impact on both forward and backward linkages.

Adding a policy area is associated with an average increase of 0.4% of total domestic value added and an average increase of 0.26% of foreign value added. The coefficients increase substantially for core depth only: Those policy areas are particularly important as they reduce the governance gap between countries in areas that are relevant for GVC-related trade.Footnote 18 Also, the coefficients of PCA depth show a similar pattern to the coefficient of total number of provisions. Part of the difference in the magnitude of the coefficients is due to the different range of the independent variables. A one standard deviation increase in the number of provisions is associated with a 0.07% increase in domestic value added and a 0.05% increase in foreign value added; similarly, a one standard deviation increase in PCA depth is associated with a 0.06% increase in domestic value added and 0.10% increase in foreign value added.

The in-force or inactive PTA dummy variable is non-significant in most of the estimations. This variable controls for the presence of shallow PTAs and for agreements that are no longer in force for which we have no information on depth. The lack of statistical significance indicates that it is the depth of PTAs—and not the mere presence of shallow agreements—that matters for GVC trade.

Control variables such as BITs have the expected sign: BITs have a positive effect on GVC-related trade. The magnitude of the BITs coefficient needs to be interpreted carefully, given that these agreements often focus on specific sectors or areas. Therefore, in our regressions, which are aggregated at the country level, their effect might be positively biased.

A concern is that the trade variables in our first set of regressions may be driven by traditional trade in final goods and services rather than by GVC trade. To address this concern, we assess the impact of deep trade agreements on FVA and on DVA separately for intermediate and final goods and services. The results that are presented in Table 3 decompose domestic value added into: DVA in final exports (columns 1–3); DVA in intermediate exports (columns 4–6); and DVA of re-exported intermediates (columns 7–9). The coefficients that capturing PTA depth are significant only for DVA of intermediate exports: Deep trade agreements are particularly important in the context of GVCs as compared to trade in final goods. Our results indicate that countries tend to export more goods that incorporate their domestic intermediate goods and services to partners with which they signed a PTA that covers more policy areas.

In terms of magnitudes, the coefficients that capture the impact of adding one additional provision on domestic value added in intermediates are slightly higher as compared to the aggregate variables that are presented in Table 2 and are equal to 0.48% on average. In addition, the positive relationship between deeper trade agreements and GVC integration is particularly important for the sub-set of re-exported intermediates that cross the border at least twice: Deep agreements are particularly important in the context highly fragmented production processes. A one standard deviation increase in the number of provisions is associated with a 0.04% increase in the domestic value added of final exports and a 0.09% increase in the domestic value added of intermediate exports.

The results for the effect of deep agreements on foreign value-added trade of final and intermediate exports are presented in Table 4. Also, in this case the positive impact of our variable of interest is significant only for FVA of intermediate exports. As for domestic value added, countries tend to export more goods that incorporate foreign intermediate goods and services to partners with which they signed a PTA that covers more policy areas: Deeper agreements could increase the integration in value chains in middle stages of production—a country exports intermediate goods that contain foreign value added—rather than in assembling: a country exports final goods that are made of foreign value added.

The coefficients are also larger as compared to the baseline regression. Adding an extra provision in an agreement increases the foreign value added of intermediate exports by 0.38%. A one standard deviation increase in the number of provisions is associated with a 0.01% increase in the foreign value added of final exports and a 0.07% increase in the foreign value added of intermediate exports.

In Table 5 and Table 6 the results for the impact of deep trade agreements on GVC integration are presented for goods and services separately. For simplicity, the results are presented for only one of our depth variables.Footnote 19 In the case of goods, the relationship between deep trade agreements and forward GVC linkages is mainly driven by domestic value added in intermediate exports and is significant only at a 10% level. For foreign value added, depth is positive and significant only for intermediates. For services, deeper agreements have a positive impact on domestic value-added services with results that are once again driven by intermediate exports, and foreign value-added services. Notice that the coefficients of deep trade agreements tend to be larger for services than for goods: Agreements that extend beyond pure market access are particularly important for GVC integration in services. A one standard deviation increase in the number of provisions is associated with a 0.04% increase in the domestic value added of intermediate goods exports and a 0.08% increase in the domestic value added of intermediate services exports. Finally, the coefficient on BIT is consistently positive and significant for goods but consistently insignificant for services. This is in line with the growing role played by deep PTAs in laying out the regulatory terms for trade in services and investments, which often surpass the scope of BITs.

3.3 Sector Level Regressions

In this section we investigate whether the impact of deep trade agreements on GVC participation is heterogeneous across industries with different levels of value-added shares in total production. We estimate the following specification:

where \(GVCtrade_{ijtk}\) is a measure of GVC integration between country \(i\) and \(j\) in sector k at time \(t\); \(Industry VA_{k}\) is a variable that captures the value added of a certain industry and it is measured either as the share of value added that an industry has in total production (see Appendix Table 15) or with a dummy variable that is equal to one when the share of value added of an industry is above the median and zero otherwise; \(Depth_{ijt}\), \(PTA_{ijt}\), and \(BIT_{ijt}\) are defined as in Eq. (1); and \(\delta_{ijk}\), \(\delta_{ikt}\), and \(\delta_{jkt}\), represent country-pair-industry, reporter-industry-time, and partner-industry-time fixed effects, respectively.

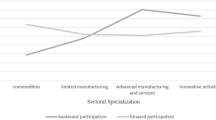

The results for goods that are presented in Table 7 suggest that deeper agreements are equally relevant on average for higher value-added industries as compared to lower-value industries. On the other hand, the results for services GVC integration that are presented in Table 8 show that the interaction term between depth and industry value added is always positive and significant for domestic value added; for foreign value added the results are less robust. The absence of significant differentiated effects for goods might be explained by the fact that the variation across industries in the level of value added is much lower for goods as compared to services. In addition, the value added that is incorporated in services production is usually higher than the value added that is incorporated in goods production. This is in line with the concept of the “smile-curve” in the GVC literature.Footnote 20 The magnitude of the impact of depth on higher value-added industries is usually higher for services GVC integration: Deep trade agreements help countries to integrate in industries with higher levels of value added.

4 Content of Trade Agreements, GVC Integration, and Income Level

Different groups of provisions may matter more for PTAs between countries at different levels of development. Intuitively, this is because the reason for signing trade agreements could be different depending on the countries that are involved and on the level of liberalization that has already been achieved. Moreover, as shown in Hofmann et al. (2019) the scope of PTAs varies across different groups of countries: The PTAs that have been signed among developed countries (North) are roughly as deep as the agreements that have been signed between developed and developing (South) countries; on the other hand, the PTAs that have been signed among developing countries are on average shallower. We study how the content of PTAs affects GVC trade between North–North, North–South, and South–South country-pairs.Footnote 21

For this exercise, we use the data on trade in parts and components to exploit the information from a larger sample. As a first step we investigate the relationship between deep PTAs and trade in parts and components on a sample of 184 countries for the time interval 1995–2014. In particular we estimate the structural gravity model in Eq. (1) with the use of trade in parts and components as the dependent variable. As a second step we add to our baseline regression the interactions of our variables of depth with three dummy variables that identify three mutually exclusive country groups: North–North, North–South, and South–South. The specification is as follows:

where \(LevDev_{ij}\) represents a vector of any two dummy variables among the three country groups defined above.

The results from the PPML estimations in Table 9 are in line with the results that use trade in value added. In particular, including one more provision increases trade in parts and components by 0.3% on average. An additional core provision has a larger impact of 0.6% on average. A one standard deviation increase in the number of provisions is associated with a 0.02% increase in gross imports of parts and components, and a one standard deviation increase PCA depth is associated with a 0.18% increase in gross imports of parts and components.

We find that deep PTAs affect trade in parts and components differently depending on the income group of the countries that are involved (Table 10): Column 1 shows that the average impact of WTO+ and WTO-X provisions is not significant. Column 2 includes the interactions of the number of WTO+ and WTO-X provisions with binary variables that identify South–South and North–South country-pairs. Thus, the coefficients of the number of provisions have to be interpreted as the coefficients for the omitted category: North–North pairs. Columns 3 and 4 have the same structure but with South–South and North–South pairs as omitted categories, respectively. The effect of PTA depth on North–South GVC-trade is driven by WTO-X provisions such as investment, competition policy, and other behind-the-border provisions. On the other hand, South–South GVC-trade is mostly affected by WTO+ provisions. For North–North agreements, the coefficients on WTO+ and WTO-X are not significant.Footnote 22

While there is no formal theory to guide the analysis, the differential effects of deep agreements across countries’ levels of development may have a simple intuitive explanation. Deep trade agreements affect GVC trade directly, as they lower trade barriers between members, and indirectly, as they improve institutions through commitments to reform. Deep PTAs may matter less for developed countries as trade is already liberalized and domestic institutions are robust. On the contrary, weak institutions in developing economies are likely to be a constraint for GVC integration with developed countries, and deep provisions can offer a commitment device and should therefore increase GVC-related trade. Finally, since tariffs and other border barriers are often still high between developing countries, PTAs may affect GVC trade mostly through traditional trade liberalization in South–South relationships.

5 Robustness

In this section, we undertake three robustness tests.

5.1 PTAs Indirect Effects

In a world where production is fragmented across countries, the level of depth of preferential trade agreements that are signed by third countries along the supply chain could indirectly affect GVC-related trade between two countries. Intuitively, deeper trade agreements in third countries reduce trade costs along the entire supply chain, which thus encourages trade in intermediates also among countries that are not part of the agreement. To control for the indirect effect of deep trade agreements, we follow Noguera (2012) and estimate the impact of deep PTAs on the level of integration in GVCs with the use of the following modified gravity framework:

where the variables and the set of controls and fixed effects are the same as in Eq. (1), but the PTA depth variable is weighted by using two different shares: \(s_{ikjt}\) is the share of value added from country \(i\) to country \(j\) that is embodied in country \(k\)‘s final products that reaches country \(j\); and \(\varphi_{ikljt}\) is the share of value added from country \(i\) that is embodied in intermediate inputs produced in country \(k\) that are absorbed as final demand in country \(j\) after travelling through possibly multiple countries \(l\).

The estimates in Table 11 are in line with the standard gravity estimates for the total depth variable.Footnote 23 Deep PTAs tend to increase forward and backward linkages, with stronger effects for exports in intermediates. The coefficients of the modified gravity regressions are larger than those of the standard gravity model, which suggests the existence of indirect effects of signing deep PTAs through third countries.

5.2 Adjustment to Trade Policy Changes

As suggested by Trefler (2004), the adjustment of trade flows between two countries after signing a PTA is not instantaneous; it may take some time. Therefore, estimations that use consecutive years will not allow our dependent variable to adjust properly. To reduce this bias, estimations are performed with the use of three-year intervals.

The results that are presented in Table 12 have the same sign as the results in the baseline regressions, and the coefficients are slightly larger in of magnitude, which confirms the positive relationship between PTA depth and GVC-related trade.Footnote 24 In particular, adding a policy area is associated with: an average increase of 0.43% of total domestic value added (column (1) Table 12); an average increase of 0.49% of the value added in intermediate exports (column (3) Table 12); and an average increase of 0.37% of the foreign value added in intermediates (column (7) Table 12). With respect to gross trade flows, including one more provision increases trade in parts and components by 0.44% on average (column (8) Table 12).

5.3 Dynamic Effects

To control for reverse causality and shed light on potential adjustment of trade over time, regressions are performed that include leads and lags in our full samples. More specifically, we run the following regression:

where we add all of the lags of depth until \(t - 3\) and the leads until \(t + 3\) to our baseline specification.

Results for trade in value added, which are presented in Fig. 2, suggest that there are some anticipation effects of deep PTAs on intermediate domestic value added and, to a lesser extent, on intermediate foreign value added. However, these effects are limited to 1 year before the agreement enters into force. The time gap between the time that an agreement is signed by the parties and the time that it enters into force may help explain such anticipation patterns. Figure 2 also disentangles the dynamic effects of deep PTAs on the value-added components of gross exports by splitting domestic and foreign value added intermediate and final goods value added. The key insight is that both contemporaneous and cumulative effects tend to be larger for domestic and foreign intermediate value added than for domestic and foreign final value added.

For trade in parts and components, the results point to some interesting patterns in the data across different income groups: Fig. 3 shows the values of the coefficients of three different measures of depth between \(t - 3\) and \(t + 3\) for the three country groups analyzed above: North–North; North–South; and South–South. While the coefficients of depth are not significantly different from zero in any year before the entry into force of the agreement for any income groups, the figure suggests that the effect of deep PTAs cumulates over time for the North–South and for South–South pairs. For the former group of trade agreements, the cumulative effect is particularly strong, which is consistent with the view that deep agreements may have offered a commitment device for reforms in developing economies that have helped them anchor to GVCs. The cumulative effect for the South–South country-pairs is not significant.

6 Conclusions

This paper contributes to the existing literature on the relationship between trade agreements and cross-border production linkages. There are three main novelties in the paper: First, it uses new data on trade in value added in addition to more standard data on trade flows of parts and components to assess separately the impact of trade agreements on goods and services and to investigate whether the relationship between trade agreements and GVC participation is heterogeneous across industries with different levels of value-added shares. Second, it exploits new information on the content of a larger number of PTAs and attempts to identify which type of provisions matter the most for GVC-related trade. Third, it examines how the effect of the content of deep PTAs changes, depending on the level of development of the countries that are involved in trade agreements.

With this new approach, we are able to establish three main results:

-

1.

The depth of trade agreements is associated with more GVC-related trade among participating countries. The positive relationship between deep agreements and GVC integration is driven by value-added trade in intermediates rather than in final goods and services. Adding a policy area to a PTA increases the domestic value added of intermediates (forward GVC linkages) and the foreign value added of intermediates (backward GVC linkages) by 0.48 and 0.38%, respectively.

-

2.

At the sectoral level, deep trade agreements are more relevant for higher value-added industries: Deeper trade arrangements help countries to integrate in industries with higher levels of value added.

-

3.

Provisions that are outside the current WTO mandate—such as competition policy and investment—are key drivers of the relationship between deep trade agreements and GVC-related trade—particularly for North–South PTAs. More traditional trade-related border provisions are still an important driver of GVC trade for South–South PTAs.

As a venue for future research, there is still little knowledge on and understanding of the relationship between the content of specific provisions in trade agreements and trade, GVC participation, and other variables of interest. Recent work at the World Bank involves collecting data by core provision and studying how this metric of depth affects economic outcomes.

Notes

As is common in the recent trade literature, the term PTAs will be used throughout the paper and is preferred to the term ‘regional trade agreements’ (RTAs) since some of these agreements are not necessarily among countries within the same region or in regional proximity. We will also often refer to PTAs as ‘deep (trade) agreements’, in recognition of the fact that several provisions in PTAs are not preferential in nature (Baldwin and Low 2009).

In our analysis we exclude partial scope agreements that cover only certain products.

See Horn et al. (2010).

Table 13 in “Appendix” presents the list of provisions. More details on the methodology and the data on deep trade agreements can be found in Hofmann et al. (2019). The data are freely available at the following website: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/content-deep-trade-agreements.

Unless otherwise stated, all provisions that are included in measures of PTA depth are legally enforceable. We also create an index that summarizes the depth of a PTA into three categories: shallow PTA, if it includes fewer than 10 provisions; deep PTA, if it includes between 11 and 20 provisions; and very deep PTA, if more than 21 provisions are included. Results that are obtained with this categorical variable are similar to the one reported for \(TotalDepth_{ijt}\).

The components are not weighted averages of the variables in a strict sense since the coefficients (or loadings) that are associated with each variable in each component can also be negative and do not sum to one. In this paper, we use the term weights when referring to the coefficients of the components.

Other components still incorporate important information in the data but their economic interpretation is difficult.

The WIOD database covers 40 countries in the period 1995–2011.

The sum of the six above mentioned value-added components do not match exactly the official trade statistics in gross value terms. The difference is due to double counting (column (7)) that tends to increase when goods and services cross borders multiple times. The work of Wang et al. (2013) contributes to a body of the literature that develops measures of the positioning of countries and industries in GVCs (see Fally 2012; Antràs et al. 2012; Antràs and Chor 2013).

Regressions that use gross trade data are estimated for 184 countries between 1995 and 2014.

We tested our work on two other trade-in-value-added datasets that are based on the Eora and GTAP Inter-Country Input–Output tables. Despite offering wide country coverage (189 for Eora and 121 for GTAP), these two datasets do not suit our empirical context perfectly, which leads to either non-significant or weakly significant results. The Eora dataset relies on several assumptions to generate the underlying time series for developing countries, which might distort our variables of interest. Being only available for selected years (2004, 2007, and 2011), the GTAP data mutes a substantial amount of variation from our sample. Possibly for this reason, we find that our key result on the relationship between deep agreements and GVC is supported only with weak significance when we use the GTAP database. Results are available upon request.

Data on BITs come from UNCTAD. The exclusion of this variable from the regressions does not affect the results.

The variable \(PTA_{ijt}\) is taken from Egger and Larch (2008).

Our regression model remains in the category of gravity models, since the country-pair fixed effects soak up the effect of distance.

This assumption may over-estimate the depth of older PTAs; but we believe that the error introduced should be negligible since most of the replaced PTAs are agreements between the European Union and acceding countries.

Results for the other depth variables are qualitatively similar and are available upon request.

The smile-curve concept, which was introduced by Acer founder Stan Shih in the early 1990s, asserts that value-added is becoming more concentrated at the upstream and downstream ends of the value chain.

North is defined as the group of high-income WTO Members, while South comprises low- and middle-income and LDC WTO members.

Estimations using the WIOD, which covers only a few developing countries, are similar to this last set of results.

The results for the other depth variables are qualitatively similar and are available upon request.

Similar results are also found when regressions are performed using four- and five-year intervals. Results for the other depth variables are qualitatively similar and are available upon request for the data in value added (Table 12).

References

Antràs, P., & Chor, D. (2013). Organizing the global value chain. Econometrica, 81(6), 2127–2204.

Antràs, P., Chor, D., Fally, T., & Hillberry, R. (2012). Measuring the upstreamness of production and trade flows. American Economic Review, 102(3), 412–416.

Antràs, P., & Staiger, R. W. (2012). Offshoring and the role of trade agreements. American Economic Review, 102(7), 3140–3183.

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics, 71(1), 72–95.

Baldwin, R. (2011). 21st century regionalism: Filling the gap between 21st century trade and 20th century trade rules. Geneva: World Trade Organization (WTO), Economic Research and Statistics Division.

Baldwin, R., & Low, P. (2009). Beyond tariffs: Multilateralising non-tariff RTA commitments, Chap. 3. In R. Baldwin & P. Low (Eds.), Multilateralizing regionalism: Challenges for the global trading system. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bickwit, G., Ornelas, E., & Turner, J. (2018). Preferential trade agreements and global sourcing. CEP Discussion Papers dp1581, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Boffa, M., Jansen, M., & Solleder, O. (2019). Do we need deeper trade agreements for GVCs or just a BIT? The World Economy, 42(6), 1713–1739.

Egger, P., & Larch, M. (2008). Interdependent preferential trade agreement memberships: An empirical analysis. Journal of International Economics, 76(2), 384–399.

Fally, T. (2012). Production staging: Measurement and facts.

Hofmann, C., Osnago, A., & Michele, R. (2019). The content of preferential trade agreements. World Trade Review, 18(3), 365–398.

Horn, H., Mavroidis, P. C., & Sapir, A. (2010). Beyond the WTO? An anatomy of EU and US preferential trade agreements. The World Economy, 33(11), 1565–1588.

Johnson, R. C., & Noguera, G. (2017). A portrait of trade in value added over four decades. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(5), 896–911.

Lawrence, R. Z. (1996). Regionalism, multilateralism, and deeper integration. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Limão, N. (2016). Preferential trade agreements. In K. Bagwell & R. W. Staiger (Eds.), Handbook of commercial policy (Vol. 1). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Mattoo, A., Mulabdic, A., & Ruta, M. (2017). Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in Deep Agreements. Policy Research Working Paper Series, The World Bank.

Noguera, G. (2012). Trade costs and gravity for gross and value added trade.

Orefice, G., & Rocha, N. (2014). Deep integration and production networks: An empirical analysis. The World Economy, 37(1), 106–136.

Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2017). Do deep trade agreements boost vertical FDI? World Bank Economic Review, 30(1), S119–S125.

Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2019). Deep trade agreements and vertical FDI: The devil is in the details. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 52(4), 1558–1599.

Piermartini, R., & Yotov, Y. V. (2016). Estimating trade policy effects with structural gravity. School of Economics Working Paper Series 2016-10, LeBow College of Business, Drexel University.

Rubínová, S. (2017). The impact of new regionalism on global value chains participation. CTEI Working Paper, The Graduate Institute, Centre for Trade and Economic Integration, Geneva.

Trefler, D. (2004). The long and short of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement. American Economic Review, 88(4), 870–895.

Wang, Z., Wei, S.-J., & Zhu, K. (2013). Quantifying international production sharing at the bilateral and sector levels. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

World Trade Organization. (2011). World Trade Report 2011: The WTO and preferential trade agreements—From co-existence to coherence. Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Richard Baldwin, Michael Ferrantino, Nuno Limão, Aaditya Mattoo, Sebastien Miroudot, Alen Mulabdic, Zhi Wang, and seminar participants at Stanford University, the University of Maryland, the Graduate Institute in Geneva, the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE) in Beijing, the OECD, and the World Bank for helpful comments and suggestions. Errors are our responsibility only. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments that they represent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laget, E., Osnago, A., Rocha, N. et al. Deep Trade Agreements and Global Value Chains. Rev Ind Organ 57, 379–410 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09780-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09780-0