Abstract

The aim of this paper is to empirically study the effect of uncertainty on private consumption using a sample of Spanish households, and therefore, to test the existence of a precautionary motive for saving. Using data provided by the Spanish Survey of Household Finances and the Labour Force Survey we construct several uncertainty measures that are commonly used in the literature and an additional indicator based on job insecurity data, and we consequently estimate different econometric models under the life-cycle/permanent income hypothesis, including these measures of uncertainty. Our results are twofold: first, we find evidence in favour of the precautionary saving hypothesis. Secondly, we find that, unlike other variables related to the performance of the labour market (such as the unemployment rate) the job insecurity indicator is an appropriate variable to approximate income uncertainty in any macroeconomic context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In this paper we test the precautionary savings hypothesis for a sample of Spanish households, using a panel of subjective and objective uncertainty measures. These are constructed from the Survey of Household Finances (Encuesta Financiera de las Familias, EFF), provided by the Bank of Spain.

The literature on consumption and savings has reached a consensus as regards to the theoretical conditions under which uncertainty generates additional household savings, the so-called precautionary savings motive (see inter alia Leland 1968; Sandmo 1970; and Drèze and Modigliani 1972). However, the empirical tests of the precautionary saving hypothesis have found mixed results. Depending on the type of data, country, or econometric approach, different authors provide inconclusive evidence.

By using uncertainty measures based on the standard deviation or the variance of income, Caballero (1991) and Kazarosian (1997) find a strong precautionary saving in U.S. while Miles (1997) or Guariglia and Rossi (2002) show evidence of precautionary saving in U.K. In the same vein, Carroll (1994) and Carroll and Samwick (1998), with U.S. data and using the Equivalent Precautionary Premium and some measures also based on the standard deviation and the variance of income to proxy uncertainty, find that coefficients on all variables are highly significant. However, Dynan (1993) approximating income uncertainty by the variance of consumption growth, finds a precautionary motive in the U.S. which is too small and inconsistent with plausible risk-aversion parameters. Guiso et al. (1992) and Lusardi (1997) also find scant conclusive evidence in favour of the hypothesis of precautionary saving when they analyse precautionary saving constructing a measure of subjective earnings uncertainty using Italian data. On the other hand, Mastrogiacomo and Alessie (2014) show that the small estimated precautionary effect for Dutch households may be a result of a methodological shortcoming, and find that taking into account the uncertainty as perceived by the second income earner in the household precautionary saving accounts for about 30% of total saving.

The literature using uncertainty measures based on labour market performance also shows very different results. Guariglia (2001), using British data and measuring uncertainty through subjective probabilities of job loss, concludes that there is a strong precautionary motive for saving. Ceritoglu (2013), who uses the predicted probability of becoming unemployed, finds also evidence of precautionary saving for Turkish households. However, Lusardi (1998), using uncertainty measures based on ex-ante subjective probability of becoming unemployed, finds that although those perceiving a higher income risk are those saving more and accumulating more wealth, the contribution of precautionary saving to wealth accumulation is not very large and certainly cannot explain the wealth holdings of the very rich in the U.S. Also by using as uncertainty measure the subjective probability of becoming unemployed, Benito (2006) shows that job insecurity does not decrease current consumption in U.K. However, when he uses the predicted probability of job loss (calculated from a probit model) results support the hypothesis of precautionary saving effects associated with unemployment risk and job.Footnote 1

This paper contributes to the existing literature in three main aspects. Firstly, using a sample of Spanish households we find new evidence in favour of the existence of a precautionary savings motive. Our econometric results unambiguously confirm the existence of a negative impact of uncertainty on consumption. Secondly, we show that depending on the specific uncertainty measure its impact on consumption is different. In general, we find that subjective measures (based on self-perception about future household income variability) tend to generate a non-significant impact on consumption, and hence on savings. Objective measures (as the risk of losing the job, proxied by the unemployment rate, or the job insecurity that the household reference person faces) generate a significant negative impact on consumption. Finally, we show that the impact of these objective measures is different depending on the moment of the business cycle we are studying. Specifically, we find that in a context of low unemployment rates, the uncertainty measured through the jobless rate exerts no impact on household consumption, whereas when it is high and rising it becomes an important source of income uncertainty, generating a large share of precautionary saving. However, when we control for time-invariant effects by estimating a fixed-effects panel data model, contrary to expectations, the unemployment rate has a significant and positive effect on consumption which casts doubts on the validity of this variable as an adequate uncertainty measure. The job insecurity measure, on the contrary, is significant at all business cycle horizons as well as in the panel specification.

The main feature of this paper is the inclusion of multiple measures of uncertainty. In the existing literature each author has constructed different measures based on the specific information provided by their dataset. In this sense, our paper reviews these measures and includes as many as possible given our data in the specification of an empirical consumption function. This allows us to check which of these measures are more reliable as uncertainty sources for the households included in our sample. Moreover, we construct an individual composite index of job insecurity, based on the information provided by our dataset, which allows us to introduce a novel source of income uncertainty, the job insecurity faced by the household reference person. This individual composite index combines information on seniority, type of job arrangement (part time/full time), type of contract, number of previous employers, firm size and unemployment record. The higher the index the more vulnerable the worker is to a potential job loss, and thus we expect a fall in current consumption to increase saving as a buffer against future contingencies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a composite index of this type is introduced in a consumption equation to test the precautionary saving hypothesis.

Another feature of this paper is that it collects data for two years (2008 and 2011), allowing thus comparisons between household consumption behaviour before and during the Great Recession. The magnitude of such recession, especially in the Spanish case, is likely to have modified the underlying consumption and saving patterns. Our results suggest that indeed this is the case, and that different uncertainty sources impact on household decisions on different moments of time.

Our results are relevant for the design of economic policy. On the one hand, they suggest that labour market reforms that tend to weaken the position of workers as regards job security are likely to impact negatively on aggregate demand, through falls in consumption. Also, it may be concluded that keeping a low and stable unemployment rate in the economy is not only an economic target per se, but would help in reducing the volatility of the saving rate of households.

After this introduction, the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly summarises the theoretical framework underlying the econometric analysis. Section 3 provides a description of the data and its main characteristics and Section 4 comprises the explanation of the uncertainty measures constructed. Section 5 presents the econometric model and the results and finally, Section 6 concludes.

2 Theoretical underpinnings

The rationale for our econometric analysis below lies in the standard theoretical framework of consumption/savings decisions in a context of uncertainty (see Leland 1968; Sandmo 1970; and Drèze and Modigliani 1972) in which individuals tend to behave prudently (Kimball 1990).

Standard theoretical models of consumer behaviour show that the optimal pattern of consumption is described by an Euler equation, which relates the expected growth of future consumption with the conditional variance of the consumption growth rate (see Attanasio 1999).Footnote 2 However, the latter cannot be directly estimated empirically, as indicated by Carroll (1992), since the conditional variance may be an endogenous variable depending on the accumulated wealth. This problem has been solved in the literature replacing this variable by different measures of uncertainty.

A wide branch of the literature has proxied uncertainty through the variability of income (see inter alia Zeldes 1989a; Caballero 1990; Guiso et al. 1992; Carroll 1994; Kazarosian 1997; Lusardi 1997; Miles 1997; Blundell and Stoker 1999; Hahm 1999; Guariglia and Rossi 2002; Menegatti 2007, 2010; or Kitamura et al. 2012) using the standard deviation or the variance of income (see for example Zeldes 1989a; Blundell and Stoker 1999; or Kitamura et al. 2012). In this same line are also the works of Caballero (1991), who measures the uncertainty of labour income by the standard deviation of the percentage change in the annual value of human wealth, or Miles (1997), who uses the variance of income and its standard deviation as a measure of uncertainty. Both find evidence of a strong precautionary saving in the US and UK, respectively. Using panel data from the US, Kazarosian (1997) proxies the individual specific income uncertainty by the standard deviation of the residual of the profile (log) income-age estimate of each individual. Guariglia and Rossi (2002) estimate the variance of the residuals of an earnings equation in the following year as the volatility of income, using British data. Both studies show evidence of the existence of precautionary savings. Also Carroll (1994) and Carroll and Samwick (1998) with the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) data obtain evidence of precautionary savings in the United States using several measures of income variability.

A different branch of literature has proxied uncertainty by the variability of consumption/expenditures. Dynan (1993) states that “consumption variability is a better measure of risk because the consumption of an optimizing household changes only in response to unexpected changes in income, which represent true risk” (p. 1105).

During recessions uncertainty about future income increases, which is to a great extent explained by rising unemployment. Thus, another branch of the literature has proxied uncertainty by the probability of continuing to receive labour income in the future. Since most consumers get their income from labour, losing their job is the biggest negative impact on their income, and the risk of future episodes of unemployment would be a good indicator of the uncertainty (see Malley and Moutos 1996; Lusardi 1998; Guariglia 2001; Carroll et al. 2003; Benito 2006; Barceló and Villanueva 2010; Cuadro-Sáez 2011; Sastre and Fernández-Sánchez 2011; for a discussion). This is closely related to the probability of being employed, and therefore to the unemployment rate.

Despite the large number of papers analysing the existence of precautionary saving, the empirical results are not conclusive. There is no consensus about the strength of this precautionary motive neither has the existing literature reached a definite answer to what is the most appropriate measure of uncertainty. Consequently, we will include in our empirical analysis several measures of uncertainty about future income as well as a number of control variables commonly used in the literature (such as income, wealth, debt, credit constraints, risk aversion and individual and familiar characteristics of households and its members). In particular, and using the Spanish Survey of Household Finances (see below) and external data (taken from the Labour Force Survey), we construct several measures related to the probability of continuing to receive labour income in the future and the household income variability.

3 Data description

Although aggregate measures of income uncertainty (based on macro data) present several advantages, the use of microeconomic information is a preferable option since the former cannot be used to measure the specific income risk of households and the information portrayed in the latter may be far more relevant to analyse consumer behaviour, especially in the context of the precautionary savings hypothesis (see Miles 1997).Footnote 3 Therefore, the use of a microeconomic dataset is preferred to analyse several aspects of the economic and financial situation of households and to assess the difference between consumption patterns before and during the current crisis. Among the existing alternatives in the Spanish case we opted for the Survey of Household Finances (Encuesta Financiera de las Familias, EFF hereafter). This is an official survey compiled by the Bank of Spain since 2002 to obtain direct information about the financial conditions of the Spanish households. This survey was conducted for 2002, 2005, 2008 and 2011 (a fifth wave, the EFF2014, is expected to be released by the end of 2017). Some important features of the EFF are: i) the inclusion of a panel component (several households are followed in consecutive waves, in particular, around 32% of households in the EFF2002 (1,666 households) have been re-interviewed in all the following waves, representing approximately 27% of households in the EFF2011); ii) the oversampling of the upper deciles of the income distribution (to better capture the behaviour of the richer families); and iii) the imputation of non-observed values following a stochastic multiple imputation technique. Specifically, the EFF imputes five values for each lost item of each household observation. Therefore, these five values may vary depending on the degree of uncertainty about the imputation model. The study object statistics are obtained by combining the information from these multiple imputations, as suggested by Rubin (1996).

The EFF provides an extensive list of variables on the characteristics of households in the sample and each of its individuals. Questions regarding assets and debts refer to the whole household, while those on employment status and related income are specified for each household member over 16 years. Most of the information refers to the moment of the interview, although information about all incomes before taxes earned during the calendar year prior to the survey wave is also collected.

An important aspect to consider is the labour status of the household reference person. In this survey the reference person is the person responsible for the accommodation. Since the household reference person is self-reported, it is assumed, as in Rossi and Sansone (2017), that he or she is who chiefly takes financial decisions. The characteristics of income sources and/or the household consumption and savings patterns, as well as possible sources of uncertainty about their future earnings are likely to differ depending on the labour situation of the household reference person. We follow the general practice in the literature (see inter alia Lusardi 1998; Carroll et al. 2003; or Benito 2006) and focus on households whose reference person is an employee. Therefore, our sample is composed by all the households whose reference person is employee (regardless of age or other characteristics).Footnote 4 This decision is justified by the type of uncertainty measures we will construct (mainly related to the labour market status) and for which information is only available for this group. To avoid the effect of outliers without dropping observations (since our sample size is not too large) we have replaced the highest 1% and lowest 1% values by the contiguous values counting inwards from the extremes. In our final sample we eliminate the households with missing values in some of the uncertainty measures. In particular, we drop 30 households in the 2008 wave and 51 in the 2011 wave due to missing values for the job insecurity indicator and the measures related to the perception of the individual about losing his/her job in the future.

4 Measuring uncertainty

We first use subjective data to build an uncertainty measure related to income variability.Footnote 5 Guiso et al. (1992) and Lusardi (1997) find inconclusive evidence on the precautionary saving hypothesis using subjective data of the variance of income drawn from the information provided by the Italian Survey on Income and Wealth (SHIW). Their uncertainty measure is based on household responses to two questions regarding the probability distribution of the rate of growth of income and inflation in the year following the interview. The EFF has a similar question: households are inquired about their expectations about future income.Footnote 6 However, households are only asked about if they believe that their future income will be higher, lower or equal than current income, but not the distribution of this income expectation. Therefore, from this information we can only generate a dummy variable (Negative Y expectations), taking value one when the household thinks that its future income will be lower than current income (bad expectations about their future household income) and zero otherwise.Footnote 7 This, obviously, limits the strength of this variable as a proxy for uncertainty.

The remaining uncertainty measures are related to the probability of continuing to receive labour income in the future. Although in this case the EFF data would allow us to construct different (objective and subjective) measures at the individual level since we have the information needed for all household members aged 16 and over, we decide to proxy the household uncertainty by that of its reference person.Footnote 8

In empirical works, income uncertainty due to the risk of unemployment is proxied by several variables. Studies based on micro data have measured the risk of unemployment by the ex-ante (subjective and/or predicted) probability to become unemployed (job loss). This is the focus of the works of Lusardi (1998), Guariglia (2001) and Benito (2006), among others.

As regards the subjective measures, changes in the survey design between 2008 and 2011 do not allow us to construct exactly the same variables, although they basically measure the same concept and are comparable. In the case of the EFF2008, respondents declared whether they believed they would lose their job or not in the following twelve months. Accordingly, we construct a dummy (Losing job) for the reference person, taking value 1 when the individual believes that he will become unemployed in the next 12 months, and 0 otherwise.

In the EFF2011, however, respondents are asked to assign a specific probability to the event of losing their job in the forthcoming twelve months.Footnote 9 From this information we derive two uncertainty measures, using only the responses given by the household reference person. The first one (denoted p2 of losing job) is just the square of this subjective probability, which gives greater weight to higher odds of becoming unemployed. Specifically, we re-scale the probability to a 0–1 interval and square it. The second uncertainty measure is the one used in Lusardi (1998) and Guariglia (2001). Under certain simplifying assumptions, they derive a measure of the variance of income from the subjective probability of being unemployed in future. Let p the subjective probability of job loss and (1−p) the probability of maintaining the employment status. If the replacement rate of the unemployment insurance is zero and earnings do not change when the respondent does not lose his job (income next year will be the same as in the current year), then the individual earnings can be interpreted as a random variable, where the expected value of earnings is (1−p)Y and the variance of income is equal to p(1−p)Y2, where Y is the logarithm of labour income (see Lusardi 1998, p. 451). Ceritoğlu (2013) also uses this measure of labour income risk, obtaining evidence of precautionary savings for Turkish households. But unlike Lusardi (1998), Guariglia (2001) or the present paper, he does not use a subjective probability of becoming unemployed, but rather a probability predicted from a first stage probit model. In any case, we have built this second variable of uncertainty (denoted Variance of expected labour Y) from the labour income data for the household reference person in 2011 (in logs) and the probability that he/she assigns to become unemployed in the next twelve months.Footnote 10

In addition to the subjective probability of losing the job, we can proxy the uncertainty in the labour market from several objective measures. In the empirical works at a macroeconomic level is common to use the unemployment rate as a proxy for uncertainty. Thus, those who have been assigned higher unemployment rates will be subject to greater future job insecurity than those who belong to a group with lower average unemployment rate (See Mody et al. 2012; Bande and Riveiro 2013; or Estrada et al. 2014).

Given that the EFF does not report unemployment rates (under any type of aggregation) nor the geographical location within the Spanish territory of households in the sample (such that we could assign the jobless rate of where they lived) we are forced to use external data in assigning unemployment rates to households.Footnote 11 Following Campos et al. (2004), we use the unemployment rates provided in the Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the gender and age group to which the household reference person belongs to. So, using the LFS microdata we compute, for each EFF wave, average unemployment rates by five-year age groups and gender, and assign those rates to the households included in the EFF. In this way, the uncertainty measure is the unemployment rate assigned to the household reference person for the current year (Un rate).Footnote 12 If the precautionary saving hypothesis holds, households would consume less the higher the unemployment rate; that is, when the reference person belongs to a group with higher average unemployment rate, the household would perceive more uncertainty about future labour income and would reduce their consumption expenditures, i.e., precautionary saving would take place.

Labour market uncertainty can also be measured through other objective variables related to the reference person’s job. Some of them are seniority, size of the company, number of employers, having a temporary contract, having been unemployed in the previous year or working part time. Overall, the first two are negatively related to the risk of job loss while the remaining have a positive relationship with uncertainty (see Lusardi 1997; Benito 2006 or Miles 1997; among others). Working part time can be a choice of the worker, but the evidence suggests that those who have this type of contract are generally subject to less job security than those who work full time. Employees who are hired on full-time or with permanent contracts may experience less job insecurity because they may have a greater feeling of being an integral part of the organization than part-time or temporary employees would (Barling and Gallagher 1996; Sverke et al. 2000). For the Spanish economy, Barceló and Villanueva (2010) using data from the EFF (waves of 2002 and 2005), find evidence in favour to the existence of precautionary savings proxying the probability of losing employment by the type of contract that the main recipients of income at household have.

Given the different dimensions of job insecurity, we opted to construct an overall composite indicator of job insecurity, rather than using these variables in isolation of one another in the econometric estimations. In particular, the six variables that make up the indicator are seniority, working time, type of contract, number of employers, firm size and unemployment record.

We build this uncertainty measure (Job insecurity indicator) by assigning a numerical value (consecutive numbers) to each of the different categories of these six variables, such that the greater the value the poorer the employment status of the household reference person (i.e. values in ascending order from best to worst employment situation). To avoid penalizing the different work situations in the variables having more categories (by construction they would have greater values of the indicator), we normalize the assigned values by the number of categories of the variable, so that the maximum value that can be assigned is 1 in each variable. The aggregation method to construct the indicator is a linear aggregation (i.e., the sum of the normalized individual indicators) and, in this case, unweighted. The resulting job insecurity indicator is therefore the sum of the assigned values to these six variables according to the employment status of the reference person in the household (Table 1). In this context, greater job insecurity is proxied by higher values of the indicator, reflecting, therefore, a greater likelihood of becoming unemployed. It is important to remind that this measure is computed at the individual level and, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time in the literature that such type of uncertainty indicator is employed in the analysis of precautionary savings.

5 Econometric model and results

In the existing literature three variants have been used to test for the existence of a precautionary motive for saving. Some authors analyse the effect of uncertainty on consumption (see inter alia Attanasio and Weber 1989; Zeldes 1989a; Coejo et al. 1990; Guiso et al. 1992; Argimón et al. 1993; Dynan 1993; Carroll 1994; Miles 1997; Blundell and Stoker 1999; Banks et al. 2001; or Benito 2006, among others). Other authors explore the impact of uncertainty estimating saving equations directly (see inter alia Jappelli and Pagano 1994; Hubbard et al. 1994; Hahm 1999; Hahm and Steigerwald 1999; Guariglia 2001 or Guariglia and Kim 2003, for example). A third group of authors have analysed the proportion of wealth (of a country or a household) explained by the presence of uncertainty or how the wealth-to-income ratio varies when a source of uncertainty is included (see, for example, Caballero 1991; Hubbard et al. 1995; Guiso et al. 1996; Kazarosian 1997; Lusardi 1997, 1998; Carroll and Samwick 1998).

Among these three general approaches, the first one seems to best fit our dataset.Footnote 13 Thus, we will assess the existence of precautionary saving by analysing the effect of different types of uncertainty measures on consumption. If there is a precautionary motive for saving, uncertainty in the current period should increase savings and thus decrease current consumption, i.e., we expect a negative sign on the uncertainty variable.

The econometric model relates current consumption of a household with a number of covariates measuring personal, family, work and financial characteristics. Specifically, assuming that the underlying relationship between the dependent and independent variables can be expressed in a log-linear form, the model is:

Where ci is non-durable consumption of the i-th household; B and C are vectors of parameters to be estimated; β0 is the intercept; Xi is a vector of variables that collects personal individual characteristics of each individual/household (age, sex, education level…) and Zi is a vector of variables that reflect the main economic determinants of consumption (income, real wealth and financial wealth, expressed in logarithms); UNCi is the uncertainty measure; vi is an error term assumed independently and identically distributed. This equation is estimated by OLS (see Carroll 1994; Lusardi 1997; Miles 1997; Guariglia and Rossi 2002; Deidda 2013; or Estrada et al. 2014; among others).Footnote 14,Footnote 15

The income variable included in the model is the income of the household reference person in the year prior to the survey, given that our uncertainty measures are defined in relation to this reference person. We include the income of the previous year and not of the current year by homogeneity in the data. The interviews for the survey are conducted in different moments of time and, therefore, households respond at the time of the interview what their “regular monthly” income is. Thus, to avoid assuming that current income is the same throughout the year of the interview, we use the income of the previous year which is the last known yearly income. The respondents report their total income (in different categories) in the calendar year preceding the survey (2007 or 2010, in each case).Footnote 16

A set of variables comprising individual and family characteristic are also included in addition to income and wealth. These variables are the size or composition of the family (see, for example Skinner 1988; Lusardi 1993, 1997; or Banks et al. 2001), whether there are children at home (as in Miles 1997; Kazarosian 1997; Lusardi 1997; Carroll and Samwick 1998; or Guariglia and Kim 2003) and the number of recipients of income, which in our case refers to the number of adults with a job (Dynan 1993; Lusardi 1998; or Guariglia and Kim 2003; among others). Other variables that reflect personal characteristics are age, gender, marital status, health or education level (see, for example, Guiso et al. 1996; Kazarosian 1997; Carroll and Samwick 1998; Lusardi 1998; Guariglia 2001; Benito 2006; or Deidda 2013).

Equation (1) is initially estimated by OLS for separate waves of the survey, namely 2008 and 2011. Thus, we are able to analyse whether results change in two different moments of time characterised by completely different macroeconomic contexts. However, the OLS estimation by waves may be flawed due a sample selection bias. Given that we have selected households where the reference person is an employee (in order to explore the impact of labour income uncertainty on saving decisions) there could be some factors that lead individuals to become employees instead of self-employed and that could affect consumption. Also, some individuals could switch labour status from one wave to the other (employee to self-employed, for instance), and therefore they would be included in one sample but not on the other. Thus, in the OLS estimations we cannot control for these time-invariant factors that affect occupational choices of individuals. To explore the potential impact of these issues on our results we exploited the panel component of the survey, and estimate an additional model including individual fixed-effects.Footnote 17 In this panel estimation, the households included in the regressions (704) are those whose reference person is the same in both years.

Before presenting our results, in order to analyse and interpret them it is necessary to overview the different macroeconomic context in which they are estimated. In general terms, 2008 is characterized by high private debt (the household debt as a percentage of GDP reached 83% in 2007), the absence of liquidity constraints (by 2008, before the financial meltdown, the Spanish banking system had completed a wild competition process, fuelled by the housing bubble: commercial and saving banks had competed for new clients using mortgages and personal loans as a commercial vehicle, hence the wide availability of cheap credit) and a very low (for the Spanish standards) unemployment rate (in 2007 the unemployment rate stood at the 30-years low 8.2%, rising to 11.2% in 2008). On the contrary, 2011 is characterized by a high and rising unemployment rate (almost doubled since 2008, reaching 21.4%). The private debt in terms of GDP continued to increase during the first years of the crisis due to the negative performance of aggregate production, reaching its peak in 2010. In addition, the strong restructuring of the banking sector, forced by the financial meltdown, led commercial banks to restrain credit, limiting the ability of households to borrow. Our econometric results are consistent with these differences in the macroeconomic context.

We begin by analysing the impact of subjective uncertainty measures. Table 2 summarises the empirical results. Columns (1), (4) and (8) provide a baseline scenario in which we estimate the consumption model without any uncertainty measure. Columns (2) and (3) summarise the results for 2008 including the two available measures, the negative expectations about future household income and the expectations about losing the job in the next twelve months, (denoted as “Negative Y expectations” and “Losing job”, respectively), while columns (5) to (7) report the estimated coefficients for 2011 with the available measures, the negative expectations about future household income, the squared probability of losing the job in the next twelve months and the variance of expected labour income (“Negative Y expectations”, “p2 of losing job” and “Variance of expected labour Y”). In general, the results for the standard control variables are in line with previous analysis, with expected signs. Wealth impacts positively on consumption, and the household characteristics show the expected relations.Footnote 18 Additionally, the estimated coefficients are, in general, robust to the specification as regards the inclusion of different uncertainty measures, even though they differ in magnitude in the two waves. This is especially interesting as regards wealth variables. Real wealth shows greater coefficients in 2008 (0.023) than in 2011 (0.012), whereas financial wealth has greater coefficients in 2011, and is only significant at the 90% in 2008. Contrary to the predictions of standard models of consumption, income is not significant in 2008, turning to significant coefficients in 2011. We interpret this joint result as the outcome of the macroeconomic context outlined above. In 2008 the household wealth had been substantially increased, mainly real wealth through the increase in real estate prices due to the housing boom. This growth of wealth, coupled with the absence of liquidity constraints may explain why in 2008 income is not significant. Households had purchasing power via wealth and borrowing against their price-increasing real assets. However, in 2011, as a result of the burst of the housing bubble, real estate prices fell dramatically, hence decreasing the value of real wealth. Additionally, households tended to accumulate financial assets.Footnote 19 This would explain why the two variables of wealth are significant and robust to the type of specification, but the coefficient of real wealth is much lower in 2011 than in 2008. Due to the loss of real wealth and the existence of strong credit restrictions, in 2011 income becomes an important determinant of consumption, being, together with financial wealth, the main source of purchasing power. Moreover, the elasticity of income remains more or less stable, which means that the estimated parameter is robust to the type of specification. We have also included a dummy variable measuring risk aversion,Footnote 20 but although having a negative coefficient, this subjective variable is not significant in any specification.

As regards the analysis of precautionary savings none of the subjective uncertainty measures seem to exert a significant effect on consumption, neither in the individual wave estimation nor in the panel specification. Starting with the household expectations about future income (Negative Y expectations), (columns (2), (5) and (9) in Table 2), this variable is not significant in any year. As explained above, we constructed a second subjective uncertainty measure for 2008, a binary variable taking value 1 if the reference person of the household believes he/she will lose his job in the forthcoming 12 months (losing job). The regression with this variable resulted in a non-significant effect, most likely due to a low self-perceived risk of job loss during the strongest business cycle of the Spanish economy in the last 40 years. For 2011 we constructed two additional uncertainty measures. Firstly, we use the squared probability of the self-perceived probability of losing the job in the next 12 months, p2 of losing job (column (6) in Table 2). Given the non-significance of this measure, we also computed the variance of the expected income from the subjective probability of being unemployed in the next 12 months (Variance of expected labour Y) and estimated the model accordingly. Results, summarised in column (7) of Table 2 suggest that this subjective measure of uncertainty is not significant either. The panel specification also confirms the lack of significance of subjective uncertainty measures. In this case, the only available measure for both waves is the household expectations about future income, which also presents a negative but non-significant coefficient. Therefore, the general image that emerges from this first set of econometric results is that subjective uncertainty measures play no role in the explanation of consumption patterns of the households included in our sample, which would reject the hypothesis of a precautionary saving motive. These results are in line with those of Benito (2006) who does not find evidence of precautionary savings in UK using the subjective probability of losing the job.

Mastrogiacomo and Alessie (2014) highlight that the small impact of precautionary savings found usually in the empirical literature when using subjective measures of uncertainty could be due to the shortcoming of taking into account only the uncertainty borne by the reference person. Thus, they also include in the analysis the uncertainty perceived by the second income earner, and check whether the results for objective and subjective uncertainty measures are similar. Their results show little difference between these uncertainty measures, and that both indicate that precautionary savings account for approximately 30% of savings in the Netherlands. We followed the same strategy as a robustness check, that is, we included also the uncertainty borne by the couple of the reference person, but results do not change: the subjective measures are not significant.Footnote 21

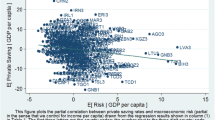

Given the lack of significance of the available subjective uncertainty measures we analyze the impact of two different objective measures, namely the unemployment rate and the job insecurity indicator, which are related to the probability of continuing to receive labour income in the future. Table 3 summarizes our results when we include the unemployment rate as the uncertainty measure. In this case we find that in the separate wave estimations this variable presents the expected negative sign, but it is only significant for 2011, with a coefficient of −1.696. We may interpret this result in the context of the macroeconomic performance of the Spanish economy during the recession. Unemployment was in 2007–2008 at its 30-year lowest value, and thus it did not generate uncertainty on consumption/saving decisions. Hence, the measure of uncertainty approximated by the unemployment rate assigned to the household’s reference person is not significant for 2008. However, in 2011, due to the strong increase in the number of unemployed workers, expectations of further rises in the unemployment rate were present (in fact, the unemployment rate peaked to 26.1% two years later). Given the great job destruction that was taking place, the unemployment risk became an important source of uncertainty. Hence, the unemployment rate turns to be significant with a strong and negative value in consumption regressions for 2011. Mody et al. (2012), Bande and Riveiro (2013) or Estrada et al. (2014) find similar results as regards the existence of precautionary savings using the level of the unemployment rate in the first two cases, and its volatility in the latter. Campos et al. (2004), however, using the probability of becoming unemployed for the reference person in the household, find no evidence of precautionary savings. This result may be in line with our estimates for 2008, given that they analyze a period (1985–1995) in which the unemployment rate did not follow a defined pattern, with marked upswings and declines. Nevertheless, the results with the panel are discouraging as regards the validity of the unemployment rate as an adequate uncertainty measure, since the coefficient on the unemployment rate is now positive and significant, which goes against the theory. Recall that our unemployment measure is an average of five-year age groups and gender, and thus, it is rather gross in order to fine-tune the uncertainty borne by households individually. Taking altogether, these results cast doubts on this objective measure of uncertainty, and reinforce our prior that rather than the unemployment risk, there may be other labour income risk sources that affect consumption/saving decisions. We turn now to the estimated models with the job insecurity indicator as the proxy for uncertainty.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the estimation of our consumption models with this new uncertainty measure. Columns (2) and (4) show that this indicator has the expected negative sign, being significant for both waves. Thus, while the coefficient takes the value −0.096 in 2008 it falls to a significant value of −0.070 in 2011. A high value for the job insecurity indicator implies that the working conditions are poor, i.e., the individual has a job with bad conditions and precarious stability, which translates into a greater risk of losing it. Barceló and Villanueva (2010) use as a measure of uncertainty the type of contract of the reference person and find evidence for precautionary savings in Spain. Our measure is more complete since it adds others sources of job instability, which may reinforce or mitigate the effect of the type of contract alone, such as seniority in the company, the size of the firm, whether the individual was unemployed or not during the previous year, etc. Our results point in the same direction than those of Barceló and Villanueva (2010). Although unemployment may be low, the labour conditions that the individuals face in the workplace may become a source of uncertainty. For instance, individuals with a worse situation, e.g., on a temporary contract, without seniority, etc., perceive greater uncertainty about their future job situation than others with greater job security. Therefore, in 2008 the indicator of job insecurity is significant. In 2011 this measure is still important but not as relevant as in 2008. We interpret this result as the outcome of the great job destruction that was taking place: uncertainty affected all types of work, and even being in a “good” and stable job was not a guarantee to avoid dismissals, and therefore many workers did not feel secure in their job, and saved “for a rainy day”. The panel estimation reinforces this result. Even though many controls become non-significant when we estimate the panel with individual fixed effect (especially income and wealth, which may be explained along the lines of the changes in the macroeconomic context, note the negative coefficient of the time fixed effect), the conclusion as regards the role of the job insecurity indicator as an adequate measure of uncertainty in consumption models is maintained. The estimated coefficient is negative and significant (−0.085). Therefore, we conclude that our empirical results support the view of the existence of precautionary savings among the households in our sample, and that job characteristics (summarised in our job insecurity indicator) measure more adequately the uncertainty about future labour income than a rather aggregated labour market measure as the unemployment rate.

As a final robustness check we finally test the effect of the macroeconomic context on household consumption/saving behaviour, pooling the information for both years into a single dataset, and estimating the model for this extended sample without any uncertainty measure with an indicator variable taking value 1 in 2011. Therefore, if this time fixed effect is significant with a negative sign, it would support our assumption that changes in the macroeconomic context affect consumption/saving decisions. Table 5 shows the result of this robustness analysis. As can be seen, the year dummy is significant and has a negative coefficient, providing thus support to our assumption about the effect of the macroeconomic context on consumption.Footnote 22

6 Concluding remarks

In general, the evidence found on this paper supports the existence of a precautionary saving motive among the Spanish households, and adds to the existing literature on this topic by providing new estimates based on different uncertainty sources. The magnitude of the effect that uncertainty has on household consumption varies depending on the considered measure of uncertainty, and the most appropriate measure in each case varies with the macroeconomic context.

Our findings suggest that subjective uncertainty measures do not provide any supportive evidence of a precautionary saving motive. Among the objective measures included in our econometric models, it seems that the job insecurity indicator serves as an adequate uncertainty measure, while the unemployment rate provides mixed results, dependent on the time period or econometric specification. We interpret this result as the outcome of the combination of a high and persistent jobless rate (which has never fell below 7%, even in the best years of the previous expansionary business cycle), an extremely persistent distribution of personal characteristics within our sample, especially as regards unemployment risk, and an imperfect unemployment risk assignment in our empirical model, since we are using 5-year average unemployment rates. The job insecurity indicator, in addition of being an individual measure not affected by assignment biases, measures more dimensions than just unemployment risk, which may exert a significant effect on consumption and saving decisions: the type of contract, seniority (which determines firing costs, and therefore employment protection), size of the firm, etc. Our empirical results suggest that this is the case, with a clear negative effect on consumption decision, regardless of the econometric specification.

These results may be helpful for the design of economic policy. On the one hand, they suggest that labour market reforms that tend to weaken the position of workers as regards job security are likely to impact negatively on aggregate demand, through falls in consumption. This is especially relevant in a highly indebted economy, as the Spanish one, where additional savings could be used to cancel out debts instead of being directed towards investment. Also, it may be concluded that keeping a low and stable unemployment rate in the economy is not only an economic target per se, but would help in reducing the volatility of the saving rate of households.

Notes

A detailed review of the existing evidence on precautionary savings, as well as the different econometric approaches and uncertainty proxies can be found in Lugilde et al. (2017).

Usually, the Euler equation includes also the income growth to capture the existence of liquidity constraints or myopia effects of the consumers which consume all their income.

Among papers using macro data we highlight the contributions of, among others, Hahm (1999), Hahm and Steigerwald (1999), Lyhagen (2001), Menegatti (2007, 2010), Mody et al. (2012) or Bande and Riveiro (2013). In the group of papers using micro data good examples are the contributions of Hall and Mishkin (1982), Skinner (1988), Attanasio and Weber (1989), Zeldes (1989a, b), Guiso et al. (1992, 1996), Dynan (1993), Lusardi (1993, 1997, 1998), Carroll (1994), Carroll and Samwick (1997), Kazarosian (1997), Miles (1997), Banks et al. (2001), Guariglia (2001), Guariglia and Kim (2003), Benito (2006), Deidda (2013) and Mastrogiacomo and Alessie (2014).

Due to the size of our sample, obtaining estimates of permanent income is not entirely correct, ruling out this approach to the subject matter.

The specific question is: “Do you think that in the future your income will be higher, lower or the same as at present?”

See Appendix for definitions of uncertainty measures.

In particular, the question is: “At present there are people who lose their job due to termination of work contract, dismissal or other reasons. On a scale of 0 to 100, what do you think is the probability that you will lose your job in the next twelve months?”

The variable labour income is constructed from the income data for the reference person in the current year provided by the survey.

The Bank of Spain has collected information about the province of birth and region of residence but this is not reported for confidentiality issues.

Note, however, that to avoid multicollinearity this forces us to drop from the group of control variables the age of the reference person. Also, note the unemployment rate is clustered in a fixed number of groups, which must be taken into account in the estimations to avoid the Moulton or group bias, which can lead to lower standard errors. We therefore use cluster standard errors using a robust covariance matrix.

The EFF also allows for the computation of total wealth, net worth and net financial worth, and therefore we could also opt for the estimation of a wealth equation, adding an uncertainty term. However, this analysis would be out of the scope of the present paper, and is left for future research.

We take the variables in logarithms to eliminate the effect of the different units of measure in which they are expressed.

All variables related to income, wealth, debt and expenditures are expressed in 2011 euros using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) as deflator. To adjust assets and debts to 2011 euros, the data from the EFF2008 have been multiplied by 1.0741. To adjust the household income for the calendar year prior to the survey to 2011 euros, factors were 1.0780 for 2008 and 1.0238 for 2011 (Banco de España 2014).

Although we are only considering employees, the income variable comprises all incomes they declare that have earned in the previous year and not just salary or extra payments received.

These time invariant effects could also affect wealth accumulation, either real of financial, which in turn could introduce potential endogeneity problems with these wealth variables. Thus, the panel estimation with fixed effects also accounts for this potential endogeneity problem. We acknowledge one of the reviewers for this important insight.

The credit constraint variable is a dummy equal to one when the household reports he/she has been denied a loan or has been granted a loan for an amount less than that he/she requested for during the last two years, or that he/she has not applied for a loan on the belief that the application would be turned down.

According to the Bank of Spain, compared to the first quarter of 2009, in the first quarter of 2011 the percentage of Spanish households with any type of financial asset was greater (and the increase in this percentage was higher in the lower half of the wealth distribution). For families with some kind of financial asset, the median value of these assets increased by 23.1%. See Banco de España (2014).

This dummy variable takes value one when households report they are not willing to take on financial risk when they make an investment, zero otherwise.

These results are not reported for brevity but are available from authors upon request.

We also run the regressions for the whole sample, pooling observations of both waves, including interaction terms between time and uncertainty indicators. Results do not change for the uncertainty variables: the significant uncertainty proxies are the objective variables. These results are not reported for brevity, are available from authors upon request.

References

Argimón, I., González-Páramo, J. M., & Roldán, J. M. (1993). Ahorro, Riqueza y Tipos de Interés en España. Investigaciones Económicas, 17(2), 313–332.

Attanasio, O. (1999). Consumption. In J. Taylor & yM. Woodford (Ed.), Handbook of Macroeconomics (Vol. 1., pp. 741–812). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Attanasio, O. P., & Weber, G. (1989). Intertemporal substitution, risk aversion and the Euler equation for consumption. The Economic Journal, 99(395), 59–73.

Bande, R., & Riveiro, D. (2013). Private saving rates and macroeconomic uncertainty: evidence from Spanish regional data. The Economic and Social Review, 44(3), 323–349.

Banco de España (2010). Encuesta Financiera de las Familias (EFF) 2008: métodos, resultados y cambios desde 2005. Economic Bulletin, 12/2010, 30–64.

Banco de España (2013). The indebtedness of the Spanish economy: characteristics, correction and challenges. Annual Report, 35–56.

Banco de España (2014). Encuesta Financiera de las Familias (EFF) 2011: métodos, resultados y cambios desde 2008. Economic Bulletin, 01/2014, 71–103.

Banks, J., Blundell, R., & Brugiavini, A. (2001). Risk pooling, precautionary saving and consumption growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 68(4), 757–779.

Barceló, C. & E. Villanueva (2010). Los Efectos de la Estabilidad Laboral sobre el Ahorro y la Riqueza de los Hogares Españoles. Banco de España: Economic Bulletin, 06/2010, 81–86.

Barling, J., & Gallagher, D. G. (1996). Part-time employment. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Ed.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 243–277). New York, NY: Wiley.

Benito, A. (2006). Does job insecurity affect household consumption? Oxford Economic Papers, 58, 157–181.

Bover, O. (2011). The Spanish survey of household finances (EFF): description and methods of the 2008 wave. Occasional Paper no. 1103, Banco de España.

Bover et al. (2014). The Spanish survey of households finances (EFF): description and methods of the 2011 wave. Occasional Paper no. 1407, Banco de España.

Blundell, R., & Stoker, T. M. (1999). Consumption and the timing of income risk. European Economic Review, 43(3), 475–507.

Caballero, R. J. (1990). Consumption puzzles and precautionary savings. Journal of monetary Economics, 25(1), 113–136.

Caballero, R. J. (1991). Earnings uncertainty and aggregate wealth accumulation. The American Economic Review, 81(4), 859–871.

Campos, J. A., Marchante, A., & Ropero, M. A. (2004). ¿Ahorran por motivo precaución los hogares españoles? Revista Asturiana Délelőtt Economía, 30, 161–176.

Carroll, C. D. (1992). The buffer-stock theory of saving: some macroeconomic evidence. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 61–127.

Carroll, C. D. (1994). How does future income affect current consumption?. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(1), 111–147.

Carroll, C. D., & Samwick, A. (1997). The nature of precautionary wealth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 40, 41–71.

Carroll, C. D., & Samwick, A. (1998). How important is precautionary saving? Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(3), 410–419.

Carroll, C., Dynan, K., & Krane, S. (2003). Unemployment risk and precautionary wealth: evidence from households’ balance sheets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(3), 586–604.

Ceritoğlu, E. (2013). The impact of labour income risk on household saving decisions in Turkey. Review of Economics of the Household, 11(1), 109–129.

Coejo, D. T., Sans, C. M., & Domingo, J. A. (1990). Una función de consumo privado para la economía española: aplicación del análisis de cointegración. Cuadernos económicos Délelőtt ICE, 44, 173–212.

Cuadro- Sáez, L. (2011). Determinantes y Perspectivas de la Tasa de Ahorro en Estados Unidos. Banco de España: Economic Bulletin, 04/2011, 111–121.

Deaton, A. (2011). The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans. NBER Working Paper, No. 17128.

Deidda, M. (2013). Precautionary saving, financial risk, and portfolio choice. Review of Income and Wealth, 59(1), 133–156.

Drèze, J., & Modigliani, F. (1972). Consumption decisions under uncertainty. Journal of Economic Theory, 5, 308–335.

Dynan, K. E. (1993). How prudent are consumers?. Journal of Political Economy, 101(6), 1104–1113.

Estrada, Á., Valdeolivas, E., Vallés, J., & Garrote, D. (2014). Household debt and uncertainty: Private consumption after the Great Recession (No. 1415). Banco de España: Documentos de trabajo.

Guariglia, A. (2001). Saving behaviour and earnings uncertainty: evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Journal of Population Economics, 14(4), 619–634.

Guariglia, A., & Kim, B. Y. (2003). The effects of consumption variability on saving: evidence from a panel of muscovite households. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(3), 357–377.

Guariglia, A., & Rossi, M. (2002). Consumption, habit formation, and precautionary saving: evidence from the British household panel survey. Oxford Economic Papers, 54(1), 1–19.

Guiso, L., Jappelli, T., & Terlizzese, D. (1992). Earnings uncertainty and precautionary saving. Journal of Monetary Economics, 30(2), 307–337.

Guiso, L., Jappelli, T., & Terlizzese, D. (1996). Income risk, borrowing constraints, and portfolio choice. The American Economic Review, 86(1), 158–172.

Hahm, J. H. (1999). Consumption growth, income growth and earnings uncertainty: simple cross-country evidence. International Economic Journal, 13(2), 39–58.

Hahm, J. H., & Steigerwald, D. G. (1999). Consumption adjustment under time-varying income uncertainty. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(1), 32–40.

Hall, R. E., & Mishkin, F. (1982). The sensitivity of consumption to transitory income: estimate from panel data on households. Econometrica, 50, 461–481.

Hubbard, R. G., Skinner, J., & Zeldes, S. P. (1994). The importance of precautionary motives in explaining individual and aggregate saving. In: Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, Vol. 40, 59–125. North-Holland.

Hubbard, R. G., Skinner, J., & Zeldes, S. P. (1995). Precautionary saving and social insurance (No. w4884). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jappelli, T., & Pagano, M. (1994). Saving, growth, and liquidity constraints. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 83–109.

Kazarosian, M. (1997). Precautionary savings: a panel study. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(2), 241–247.

Kimball, M. S. (1990). Precautionary saving in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 58(1), 53–73.

Kitamura, T., Yonezawa, Y., & Nakasato, M. (2012). Saving behavior under the influence of income risk: an experimental study. Economics Bulletin, 30, 1–8.

Leland, H. E. (1968). Saving and uncertainty: The precautionary demand for saving. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82(3), 465–473.

Lugilde, A., Bande, R. and Riveiro, D. (2017) Precautionary saving: a review of the theory and the evidence.

Lusardi, A. (1993). Euler Equations in MicroData: merging data from two samples. CentER Discussion Paper, 1993.

Lusardi, A. (1997). Precautionary saving and subjective earnings variance. Economics Letters, 57(3), 319–326.

Lusardi, A. (1998). On the importance of the precautionary saving motive. American Economic Review, 88(2), 449–453.

Lyhagen, J. (2001). The effect of precautionary saving on consumption in Sweden. Applied Economics, 33, 673–681.

Malley, J., & Moutos, T. (1996). Unemployment and consumption. Oxford Economic Papers, 48, 548–600.

Marchante, A., Ortega, B., & Trujillo, F. (2001). Regional differences in personal saving rates in Spain. Papers in Regional Science, 80, 465–482.

Mastrogiacomo, M., & Alessie, R. (2014). The precautionary savings motive and household savings. Oxford Economic Papers, 66, 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpt028.

Menegatti, M. (2001). On the conditions for precautionary saving. Journal of Economic Theory, 98(1), 189–193.

Menegatti, M. (2007). Consumption and uncertainty: a panel analysis in Italian regions. Applied Economics Letters, 14(1), 39–42.

Menegatti, M. (2010). Uncertainty and consumption: new evidence in OECD countries. Bulletin of Economic Research, 62(3), 227–242.

Miles, D. (1997). A household level study of the determinants of incomes and consumption. The Economic Journal, 107(440), 1–25.

Miller, B. L. (1974). Optimal consumption with stochastic income stream. Econometrica, 42, 253–266.

Miller, B. L. (1976). The effect on optimal consumption of increased uncertainty in labor income in the multiperiod case. Journal of Economic Theory, 13, 154–167.

Mody, A., Ohnsorge, F. & Sandri, D. (2012). Precautionary Savings in the Great Recession. IMF Working Paper WP12/42.

Pratt, J. W. (1964). Risk Aversion in the Small and in the Large. Econometrica, 32, 122–136.

Rossi, M. & Sansone, D. (2017). Precautionary savings and the self-employed. Small Business Economics, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9919-x.

Rubin, D. B. (1996). Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91(434), 473–489.

Sandmo, A. (1970). The effect of uncertainty on saving decisions. The Review of Economic Studies, 37(3), 353–360.

Sastre, T. & J. L. Fernández-Sánchez (2011). La Tasa de Ahorro Durante la Crisis Económica: el Papel de las Expectativas de Desempleo y de la Financiación. Banco de España: Economic Bulletin, 11/2011, 63–77.

Skinner, J. (1988). Risky income, life cycle consumption, and precautionary savings. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(2), 237–255.

Sibley, D. S. (1975). Permanent and transitory effects in a model of optimal consumption with wage income uncertainty. Journal of Economic Theory, 11, 68–82.

Sverke, M., Gallagher, D. G., & Hellgren, J. (2000). Alternative work arrangements: Job stress, well-being and pro-organizational attitudes among employees with different employment contracts. In K. Isaksson, C. Hogstedt, C. Eriksson & T. Theorell (Ed.), Health effects of the new labour market (pp. 145–167). New York, NY: Plenum.

Zeldes, S. P. (1989a). Optimal consumption with stochastic income: Deviations from certainty equivalence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(2), 275–298.

Zeldes, S. P. (1989b). Consumption and liquidity constraints: an empirical investigation. The Journal of Political Economy, 97(2), 305–346.

Acknowledgements

Comments from other members of the GAME research group, participants at seminars at the University of Naples and at the University of Santiago de Compostela, as well as from Tullio Jappelli, are gratefully acknowledged. Remaining errors are our sole responsibility.

Funding

This research has been partially funded by Xunta de Galicia through grant ED431C 2017/44. Alba Lugilde acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Education through the FPU grant FPU13/01940.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lugilde, A., Bande, R. & Riveiro, D. Precautionary saving in Spain during the great recession: evidence from a panel of uncertainty indicators. Rev Econ Household 16, 1151–1179 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9412-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9412-6