Abstract

We examined the Direct and Indirect Effects model of Writing (DIEW), using longitudinal data from Korean-speaking beginning writers. DIEW posits hierarchical structural relations among component skills (e.g., transcription skills, higher order cognitive skills, oral language, motivation/affect, background knowledge) where lower level skills are needed for higher order skills and where component skills make direct and indirect contributions to writing (see Fig. 1). A total of 201 Korean-speaking children were assessed on component skills in Grade 1, including transcription (spelling and handwriting fluency), higher order cognitive skills (inference, perspective taking, and monitoring), oral language (vocabulary and grammatical knowledge), and executive function (working memory and attention). Their writing skills were assessed in Grades 1 and 3. DIEW fit the data well. In Grade 1, transcription skills were directly related to writing, whereas vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, working memory, and attention were indirectly related to writing. For Grade 3 writing, inference and spelling were directly related while working memory made both direct and indirect contributions. Attention, vocabulary, and grammatical knowledge made indirect contributions via spelling and inference. These results support DIEW and its associated hypotheses such as the hierarchical nature of structural relations, the roles of higher order cognitive skills, and the changing relations of component skills to writing as a function of development (a developmental hypothesis).

Direct and indirect effects model of writing (DIEW)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing is one of the most challenging skills to acquire. Nationally representative data from the US have consistently shown that three quarters of students write at or below basic proficiency (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2012). As a production skill, writing requires generating ideas, translating them into oral language, and transcribing them into written text. This is captured in the simple view of writing, according to which ideation (generation and translation of ideas) and transcription (encoding the translated ideas into print) are the two essential skills for writing development (Berninger et al., 2002; Juel, Griffith, & Gough, 1986). Moreover, in the not-so-simple view of writing, working memory and self-regulation (e.g., attention, goal-setting, planning, monitoring) were further identified as component skills needed for coordinating multiple and iterative processes in writing (Berninger & Winn, 2006). These two theoretical models of developmental writing—the simple and not-so-simple views of writing—are supported by a relatively large body of studies that has shown the contributions of oral language, transcription skills (spelling and handwriting), working memory, and monitoring to writing (Abbott & Berninger, 1993; Arfe, Dockrell, & De Bernardi, 2016; Babayiğit, 2014; Berninger, Abbott, Abbott, Graham, & Richards, 2002; Berninger et al., 1997; Coker, 2006; Graham, Berninger, & Fan, 2007; Graham et al., 1997; Graham, Harris, & McKeown, 2013; Hayes & Chenoweth, 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Kim, Al Otaiba, Folsom, Greulich, & Puranik, 2014a; Kim, Al Otaiba, Wanzek, & Gatlin, 2015a; Limpo & Alves, 2013; Olinghouse, 2008; Olive, 2004).

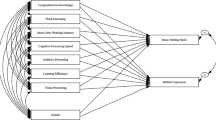

Recently the simple and not-so-simple views of writing were integrated and extended by the Direct and Indirect Effects model of Writing (DIEW; see Fig. 1). DIEW extends the previous models in two critical ways: (a) by specifying structural relations among component skills and (b) by expanding the component skills of writing to include higher order cognitive skills (e.g., reasoning, inference, perspective taking), background knowledge (content and discourse knowledge), and affect and motivation (see below for details). DIEW has been recently examined and validated with English-speaking children in the US (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017). Our goals in the present study were to extend the prior investigation in two unique ways: by investigating the generalizability of DIEW in Korean, a language that is highly different from English, and by investigating longitudinal relations of component skills to writing.

Direct and indirect effects model of writing (DIEW)

In addition to identifying component skills, specifying structural relations or pathways of relations—how component skills are related to one another and to writing—is one of the key parts of a theoretical model. According to Singer and Ruddell (1985), a theoretical model should “depict a theory’s variables, mechanisms, constructs, and interrelationships” (p. 620). Systematic relations among component skills explain mechanisms and pathways by which component skills affect writing development and reveal not only direct effects but also indirect effects. Indirect effects are particularly important for lower level skills because their contributions to writing are expected to be primarily indirect via higher order skills and, thus, can be easily masked. According to DIEW (see Fig. 1), component skills have hierarchical structural relations where foundational or low-order skills are needed for higher order skills, and higher order skills partially or completely mediate the relations of low-order skills to writing. Therefore, lower level skills have cascading effects on writing. Specifically, executive function (or domain-general foundational cognition), such as working memory, inhibitory control, and attention, supports the development of two large categories of skills, discourse oral language and transcription skills. The discourse oral language skill—the ability to produce oral texts such as extended conversations, stories, and informational texts—maps onto “ideation” in the simple view of writing (see Juel et al., 1986) and “text generation” in the not-so-simple view of writing (Berninger & Winn, 2006), as it captures the ability to generate, connect, organize, and translate ideas into oral language at the discourse level. Discourse oral language itself draws on multiple layers of skills, including foundational oral language skills (vocabulary and grammatical knowledge) and higher order cognitive skills (e.g., inference, perspective taking, monitoring) as well as executive function (e.g., working memory; Alonzo, Yeomans-Maldonado, Murphy, Bevens, & LARRC, 2016; Bianco et al., 2010; Florit, Roch, Altoe, & Loverato, 2009; Florit, Roch, & Loverato, 2014; Kim, 2015a, 2016, 2017a; Kim & Phillips, 2014; Lepola, Lynch, Laakkonen, Silvén, & Niemi, 2012; Tompkins, Guo, & Justice, 2013).

The hypothesized hierarchical structural relations in DIEW are based on empirical evidence. For instance, working memory (Bourdin & Fayol, 1994; Hayes & Chenoweth, 2007; Olive, 2004) and vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (Babayigit, 2014; Coker, 2006; Kim et al., 2011, 2014a; Olinghouse, 2008) are related to writing, and working memory is one of the essential skills for vocabulary and grammatical acquisition (see Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990; Gathercole, Service, Hitch, Adams, & Martin, 1999; Kim, 2017b; Verhagen & Leseman, 2016). Given these relations, some of the effect of working memory on writing might be mediated by vocabulary and grammatical knowledge. A similar logic applies to the relations between working memory and other component skills in DIEW such as higher order cognitive skills (e.g., inference). If inference is related to writing (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017), and inference requires working memory (Craig & Lewandowsky, 2012; Kim, 2017b), then the effect of working memory may be, at least partially, mediated by higher order cognitive skills. Recent studies indicated that executive function (or foundational cognition), foundational oral language skills, higher order cognitive skills, and discourse oral language skills are directly and indirectly related to writing (Kim et al., 2015a; Kim & Schatschneider, 2017).

The other essential component skill, transcription (spelling and handwriting fluency), draws on knowledge or awareness of phonology, orthography, and semantics (see Adams, 1990; Berninger et al., 1992; Kim, 2011; Kim, Apel, & Al Otaiba, 2013a; Nagy, Berninger, & Abbott, 2006; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; Treiman, 1993). The extent to which transcription skills are developed influences the extent to which other resources (lower level domain-general foundational cognitive skills) are available for writing processes (see information processing theory in LaBerge & Samuels, 1974). Therefore, the roles of component skills would vary as a function of developmental phase (a developmental hypothesis). When transcription skills are not automatized, typically during the beginning phase or for children with dysfluent transcription skills, children’s mental resources (e.g., working memory and attention) are used up to support transcription, and thus, transcription skills constrain employment of other component skills to a large extent. With further development of transcription skills, their constraining role would decrease, allowing these resources to be available for higher order processes.

The component skills and overall structural relations hypothesized in DIEW are expected to be language general. In other words, the broad framework of DIEW are not expected to differ across languages or writing systems because writing like language (Bock, 1982) and reading (Radach, Kennedy, & Rayner, 2004) relies on universal human information processing. However, this does not deny language- or orthography-specific processes found in many prior studies (e.g., Aro & Wimmer, 2003; Dromi & Berman, 1986; Naigles & Leher, 2002; McBride-Chang et al., 2010). In fact, as a corollary of the developmental hypothesis of DIEW, the relative contributions of component skills at different developmental phases might vary as a function of orthographic depth: The constraining role of transcription skills would not last as long in transparent orthographies as they would in opaque orthographies (see, for example, Babayiğit & Stainthorp, 2010) because, when taught well, children acquire transcription skills earlier in transparent orthographies than in opaque orthographies.

Writing, of course, requires generating ideas and therefore, draws on background knowledge, which includes both content and discourse knowledge (e.g., Beaufort, 2004; Hayes, 2006; McCutchen, 1986; Olinghouse, Graham, & Gillespie, 2015; Perin, Keselman, & Monopoli, 2003; Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1985). The importance of content knowledge has been highlighted in the knowledge-telling model according to which novice writers resort to telling what they know (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1985). Discourse knowledge includes knowledge about characteristics of different genres (e.g., text structure and associated key words) and about procedures and strategies to present content appropriate for the genre (e.g., narrative, compare-contrast; Olinghouse et al., 2015). In DIEW, background knowledge is expected to have a reciprocal relation with the development of writing and discourse oral language skills.

Furthermore, in DIEW, one’s affect and motivation, including one’s attitudes and beliefs toward and positive and negative emotions (e.g., anxiety) and thoughts associated with writing, are expected to develop interactively with children’s transcription and written composition skills. Literature on motivation has shown that students’ beliefs about their ability to perform a task and values about the importance of the task influence students’ achievement in complex tasks such as writing via their effort and persistence (Eccles, 2005; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Graham et al., 2007; Klassen, 2002; Pajares, 2003). In DIEW, the relation between writing and affect is hypothesized to be reciprocal, such that students’ development and difficulties with writing (transcription and written composition) would influence their affect and motivation, which, in turn, would influence further development of writing skills.

Another distinguishing feature of DIEW is inclusion of higher order cognitive skills as component skills. Quality writing requires “organizing and thinking through … ideas or experiences and … explicating the relationships among them” (Applebee, 1984, p. 577). Therefore, quality writing would draw on one’s analytical and reasoning skills such as inference. Perspective taking, one’s knowledge of and inferences about others’ mental and emotional states, also would be important to writing. Perspective taking in relation to writing has been studied with a specific focus on audience awareness (e.g., Carvalho, 2002; Elbow, 1981; Ryder, Vander Lei, & Roen, 1999) because quality writing requires an understanding of the needs of the readers and modulating language and structure accordingly (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017) in order to engage their readers (Wollman-Bonilla, 2001). In DIEW, perspective taking instead of audience awareness is included because it is a broader concept that encompasses audience awareness and reflects the idea that the role of perspective taking in writing goes beyond an understanding of audience. For example, source-based writing or read-to-write tasks are widely used in daily instruction (Graham & Harris, 2017) as well as state and national assessments (e.g., National Assessment of Educational Progress [NAEP]). In this case, quality writing depends on the writer’s accurate understanding of the source text (i.e., reading skills; Kim, in press), which requires an understanding of the source material author’s perspective and motivation (i.e., perspective taking) as well as perspectives of characters in the source material (Kim, 2015a, 2017a; Kim & Phillips, 2014). It should be noted that audience awareness has been studied with older children and adults, assuming that it is a late-developing skill, and is generally accepted as being relevant to writing after a certain point of development (e.g., Grade 5; Carvalho, 2002). However, even young children demonstrate perspective taking in oral language interactions (e.g., De Temple, Wu, & Snow, 1991; Kim, 2015a, 2015b, 2017a; Kim & Phillips, 2014; also see a large body of literature on theory of mind) and audience awareness in writing (Wollman-Bonilla, 2001). Overall, despite speculations (Applebee, 1984; McCutchen, 2000), reasoning (e.g., inference) and perspective taking have not been explicitly included as component skills in previous theoretical models of developmental writing. The other higher order cognitive skill, monitoring, on the other hand, has garnered attention for developing writers (e.g., Limpo & Alves, 2013) and is included in the not-so-simple view of writing as part of the self-regulation construct (Berninger & Winn, 2006). Per the developmental hypothesis noted above, higher order cognitive skills are expected to play increasingly greater roles in writing as children develop their literacy skills for a couple of reasons: (a) the constraining role of transcription skills decreases, allowing higher order cognitive skills to be available for writing processes, and (b) the complexity of texts children are expected to produce increases as children develop literacy skills (i.e., in upper grades), placing greater demands on language and higher order cognitive skills.

The structural relations hypothesized in DIEW have been recently investigated with English-speaking children. Results showed that DIEW fit the data very well, and lower level skills were found to make indirect contributions to writing via upper level skills (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017). Furthermore, a higher order cognitive skill, inference, was independently related to writing quality after accounting for transcription skills and perspective taking (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017).

Present study

Our primary goals were twofold: (a) to examine the generalizability of DIEW (the overall hierarchical structural relations and associated direct and indirect effects) in a language other than English, and (b) to test the developmental hypothesis (i.e., changing contributions of component skills over time), using longitudinal data from Korean-speaking children in Grades 1 and 3. Korean is vastly different from English in the oral language and writing system. Unlike English, the Korean language has a predicate-final structure (i.e., subject-object-verb) and rich morphology due to its agglutinative nature (i.e., a high rate of affixes and inflections). The writing system of the Korean language, Hangul, is also distinct from English as it is fairly transparent (Cho, 2009; Kim, 2011). As noted above, the overall structural relations hypothesized in DIEW are not expected to differ across languages and writing systems. Note, however, that an examination of the hypothesis about cross-language variation was beyond the scope of the present study because it requires cross-linguistic longitudinal studies.

The present study also extends the earlier study of DIEW with English-speaking children by using longitudinal data to investigate potentially changing roles of component skills as children develop literacy skills over time (see the developmental hypothesis above). As noted above, component skills are expected to have differential relations to writing outcomes as a function of development such that transcription skills are expected to have greater influences on writing in the beginning phase of writing development, whereas other skills such as higher order cognitive skills are expected to have greater influences at a more advanced phase.

Specific research questions that guided the present study were as follows:

-

1.

Does DIEW fit the data from Korean-speaking children well?

-

2.

What is the nature of concurrent relations of component skills to writing in Grade 1?

-

3.

What are longitudinal relations of component skills in Grade 1 to writing in Grade 3?

-

4.

Are higher order cognitive skills (inference, perspective taking, and monitoring) in Grade 1 related to writing skills in Grades 1 and 3 after accounting for transcription skills, foundational oral language skills, and foundational cognitive skills?

We hypothesized that DIEW would fit the data from Korean-speaking children well. Higher order cognitive skills, inference in particular, were hypothesized to be related to writing, given recent evidence from English-speaking first graders (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017). Finally, we expected that the relative contributions of component skills might differ for writing in Grade 1 versus Grade 3 such that transcription skills would play greater roles in Grade 1 writing, whereas higher order cognitive skills would play larger roles in Grade 3 writing.

Method

Participants

A total of 201 children (56% boys; mean age = 6.84 years, SD = .30) in Grade 1 participated in a larger longitudinal study of Korean literacy development wherein a cohort of children was followed from Grade 1 to Grade 3. Results on oral language skills in Grade 1 were reported earlier (Kim, 2016). Participating children were from seven classrooms in a single public elementary school in an urban area in South Korea. In Grade 3, 168 students remained, with attrition (16%) largely due to transfer to other schools. However, those who remained in the study and those who dropped out did not differ in the skills measured in Grade 1 after accounting for age, Wilks’s Lambda = .96, F(13, 147) = .50, p = .92. The school personnel and neighborhood indicated that the children were largely from middle-class or low-middle-class families although socioeconomic backgrounds of the individual children were not available. None of the participating children had identified disabilities.

Formal education in South Korea starts in Grade 1. However, the vast majority of children attend kindergarten (either private or public) and receive some form of literacy instruction. Therefore, many children have foundational literacy skills (Cho, 2009; Cho, McBride-Chang, & Park, 2008; Kim, 2011, 2015b; Kim, Park, & Wagner, 2014b) and writing skills (Kim, Park, & Park, 2013b, 2015b) at entry to Grade 1. Curriculum in elementary schools (Grades 1–6) is centralized and uniform. Reading and writing are part of the language arts curriculum and are integrated particularly in primary grades such that writing instruction mostly focuses on expressing ideas (by short answer or short essay) in response to a written passage.

Measures

Children were assessed on the following constructs in Grade 1: working memory, attention, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, inference, perspective taking (theory of mind), comprehension monitoring, spelling, handwriting fluency, and writing. Writing was assessed in Grade 3 again, using the same task used in Grade 1. All constructs were assessed by single tasks, except for handwriting fluency, which was assessed by two tasks. All the tasks were piloted and revised prior to the present study. Unless otherwise noted, children’s responses were scored dichotomously (1 = correct; 0 = incorrect) for each item and all the items were administered to children.

Working memory

A widely used working memory task, the listening span task (Kim, 2015a, 2015b; Daneman & Merikle, 1996), was used. In this task, the child was presented with a short sentence involving common knowledge to children (e.g., Birds can fly) and was asked to identify whether the heard sentence was correct or not (yes/no). After hearing two or three sentences, the child was asked to identify the first words in the sentences. The listening span task in English and European languages requires children to identify the last words in each sentence (e.g., Kim, 2017a, 2017b; Florit et al., 2009). However, in this study the child was asked to identify the first word in each sentence because final words in Korean sentences are either verbs or adjectives that inflect so that endings are highly similar (i.e., similar syllables). This version of the task was used in previous studies with Korean-speaking children and was shown to relate to vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (Kim, 2015a). There were four practice items and 18 experimental items, and administration was discontinued after three consecutive incorrect responses. Children’s responses regarding the veracity of the statements were not scored, but their responses on the first words in correct order were given a score of 0 to 2: 2 for correctly identifying all the first words in correct order; 1 for identifying the correct first words, but in incorrect order; and 0 for identifying incorrect first words. Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Attention

Attention was measured by an adapted version of the first nine items of the Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behavior Scale (SWAN; Swanson et al., 2006). The full version of the SWAN includes 30 items, but only the first nine items are related to sustaining attention on tasks (e.g., ‘‘Engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort”; Saez, Folsom, Al Otaiba, & Schatschneider, 2012), whereas the other items assess hyperactivity (nine items) and aggression (12 items). SWAN is a behavioral checklist typically rated by classroom teachers with each item rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (far below average) to 7 (far above average). SWAN was completed by the students’ classroom teachers. Cronbach’s alpha was .99.

Vocabulary

A normed expressive vocabulary task was used (Kim at al., in press). This task was developed, designed, and normed with Korean-speaking children and was not a translation of an assessment in another language. In this task, the child was asked to identify pictured objects with increasing difficulty (e.g., the child was shown an illustration of a whale and was asked to name it). There were four practice items and 52 test items. Testing discontinued after five consecutive incorrect items. Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Grammatical knowledge

Children’s grammatical knowledge was assessed by an adapted task from a previous study (Kim, 2015a). The child’s task was to detect and correct grammatical errors in grammatical markers, tense, and postpositions. The child was asked whether a heard sentence was grammatically correct. If grammatically incorrect, the child was asked to correct the sentence. The child received a point for accurately responding to the correctness of the sentence, and earned a point for each successfully correcting grammatical error in incorrect sentences. There were two practice items and 18 test items. Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

Knowledge-based inference

A knowledge-based inference task was developed modeling after the Inference subtest of the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL; Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999). In this task, the child heard two- to three-sentence scenarios and was asked a question that required inference based on background knowledge. An example item is “Soomin wanted to wear last year’s dress to school one day, but when she tried it on, she could not wear it. Why?” Correct responses included answers such as “She has outgrown the dress,” or “The dress is too small for her”. There were two practice items and 12 test items. Cronbach’s alpha was .69.

Perspective taking

Perspective taking was measured by theory of mind scenarios. Theory of mind is typically defined as one’s knowledge of the mental status and perspectives of others (e.g., thoughts and emotions; Howlin, Baron-Cohen, & Hadwin, 1999), and is widely assessed by false belief and appearance-reality tasks. Although theory of mind has been typically studied with young children (e.g., prekindergarten-aged), recent studies have revealed its development into early adulthood (Valle, Massaro, Castelli, & Marchetti, 2015). Theory of mind develops from first-order understanding (e.g., knowledge of a story character’s mistaken belief), followed by second-order understanding (e.g., knowledge of a character’s mistaken belief about another character; Astington & Jenkins, 1999; Caillies & Sourn-Bissaoui, 2008; Kim, 2015a, 2017a; Norbury, 2005).

In the present study, perspective taking was measured using first-order and second-order theory of mind scenarios appropriate to the developmental stage of the children. The first-order questions were based on an appearance-reality scenario using a snack box that is highly familiar to children in Korea (Gwon & Lee, 2012). The second-order theory of mind questions were based on false belief scenarios involving the context of a bakery and a visit to a farm (Kim, 2015a; Kim & Phillips 2014). For the scenarios, children listened to a series of events presented with illustrations, then answered the assessor’s questions requiring inference about a character’s belief (first order) or a character’s belief about another character’s thoughts (second order). The perspective taking measure included 15 questions (three first-order questions and 12 s-order questions). Cronbach’s alpha was .74.

Comprehension monitoring

Following many previous studies on comprehension monitoring, an inconsistency detection task was used (e.g., Baker, 1984; Kim & Phillips, 2014). The child heard a short story (e.g., “Jimin’s favorite color is green. His bag is green. His pants are green. Jimin’s favorite color is red.”) and was asked to identify whether the story made sense or not. The meaning of “not making sense” was explained in practice items as sentences not going together. If the child indicated that the story did not make sense, he or she was asked to provide a brief explanation and to fix the story so that it made sense. There were four practice items and 14 test items. Consistent stories (six items) and inconsistent stories (eight items) were randomly ordered. For the inconsistent stories, in addition to the accuracy of the child’s response, the accuracy of the child’s explanation was dichotomously scored, resulting in a total possible score of 22. Cronbach’s alpha was .78.

Spelling

Spelling was assessed by a 30-item dictation task (Kim & Petscher, 2013). The task was developed in consultation with primary grade educators and included orthographically transparent words and those that undergo phonological shifts (see Kim & Petscher, 2013, for the list). For each item, children were read aloud (a) the target word in isolation, (b) the target word in a sentence, and (c) the target word in isolation again. Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Handwriting fluency

Students’ handwriting fluency is typically assessed by letter-writing, sentence-writing, or paragraph-writing tasks (e.g., Kim et al. 2013b, 2015b). In the present study, we used two paragraph-copying tasks (110 words in the first task; 194 words in the second task), which were administered approximately one week apart. In these tasks, students were given a passage and were asked to copy as much of it as possible in a minute. The number of words written correctly was their score. Inter-rater reliability (exact agreement) using 50 samples was .98.

Writing

A previously used experimental task was used to assess students’ writing skills. In this task, the student was asked to write about an animal that would be best suited as a class pet and to provide reasons (Kim et al., 2015a; Wagner et al., 2011). Students’ written compositions were evaluated for overall quality focusing on the extent to which ideas were developed and organized. The rating scale ranged from 0 (unscorable due to no writing or illegible handwriting) to 5 (a clear main idea is elaborated in an organized manner). A similar approach has been used widely in previous studies (e.g., Graham, Harris, & Chorzempa, 2002; Kim et al., 2014a, 2015a; Olinghouse, 2008). Inter-rater reliability (exact agreement) using 50 writing samples each in Grades 1 and 3 (for a total of 100 written samples) ranged from 84 to 100%, respectively.

Procedures

For the majority of the tasks, children were individually assessed by rigorously trained research assistants in a quiet space in the school. Writing and spelling tasks were administered as a whole class. The two tasks of handwriting fluency skills were administered on separate days approximately a week apart. The individual assessment battery was administered in several sessions over a period of a month with each session 30 to 40 min long. Data were collected approximately three months after the academic year had started.

Data analysis strategy

Primary data analytic strategies were Confirmatory Factory Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), using MPLUS 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). A latent variable was created for handwriting fluency. The other constructs were assessed by single measures, and therefore, observed variables were used. The research questions about whether DIEW fits the data from Korean-speaking children well and about concurrent relations (Research Questions 1 and 2) were addressed by fitting and comparing three alternative models shown in Fig. 2 using data from Grade 1. In Fig. 2a, higher order cognitive skills and transcription skills were hypothesized to completely mediate the contributions of vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, working memory, and attention to writing. In Fig. 2b, direct contributions of vocabulary and grammatical knowledge to writing were examined. In Fig. 2c, working memory and attention were hypothesized to make direct contributions over and above all the other variables to writing. For the longitudinal relations question (Research Question 3), a similar set of alternative models were fitted in which direct contributions to Grade 3 writing of Grade 1 component skills, in addition to Grade 1 writing, were systematically examined (see Fig. 3a–c). These models (Figs. 2, 3) also addressed the last research question about the relations of higher order cognitive skills to writing (Research Question 4). Across all the models, vocabulary and grammatical knowledge were hypothesized to predict transcription skills, based on the importance of semantic knowledge to spelling (see Treiman, 1993) and prior evidence (Kim et al., 2013a). In addition, based on preliminary analysis, working memory was allowed to directly relate to higher order cognitive skills, but not to transcription skills, and attention was allowed to directly relate to transcription skills, but not to higher order cognitive skills (see Figs. 2, 3).

Three alternative models of relations among Grade 1 writing, inference, theory of mind, comprehension monitoring, spelling, handwriting fluency, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, working memory, and attention. G1 = Grade 1; ToM = theory of mind; Monitor = comprehension monitoring; Handwrite = handwriting fluency; Grammar = grammatical knowledge

Three alternative models of relations among Grade 3 writing and Grade 1 writing, inference, theory of mind, comprehension monitoring, spelling, handwriting fluency, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, working memory, and attention. G1 = Grade 1; G3 = Grade 3; ToM = theory of mind; Monitor = comprehension monitoring; Handwrite = handwriting fluency; Grammar = grammatical knowledge

Model fit was evaluated by the Chi square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR). Typically, CFI and TLI values equal to or greater than .90 and RMSEA and SRMR values equal to or less than .08 are considered to be acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). Model comparisons for nested models were made using Chi square differences.

Results

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analysis

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics. Mean scores in writing were somewhat low in Grade 1 (1.86) and Grade 3 (2.69), but there was sufficient variation around the means. Mean performance on the normed vocabulary task in Grade 1 ranked in the 35th percentile. Distributional properties of all the variables were appropriate as indicated by skewness and kurtosis values, which were within ± 3 for all variables except one: Kurtosis of the second handwriting fluency task was 4.28. Therefore, raw scores were used in the subsequent analyses.

Bivariate correlations between measures are presented in Table 2. Working memory, attention, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, and higher order cognitive skills were weakly to moderately related to Grade 1 and Grade 3 writing quality (.14 ≤ rs ≤ .42). Transcription skills were moderately related to Grade 1 and Grade 3 writing quality (.33 ≤ rs ≤ .52). Grade 1 writing quality was weakly related to Grade 3 writing quality (r = .28). Language and cognitive skills were weakly to moderately related to each other (.12 ≤ rs ≤ .56). Because children were nested within teachers, intraclass correlations due to classroom differences were estimated using the equation ICC = (level 2 variance)/(level 1 variance + level 2 variance). ICCs for the vast majority of measures were zero (e.g., grammatical knowledge, inference) or minimal (e.g., .013 for vocabulary, .016 for writing quality). The only exception was attention, for which the ICC was .27.

Concurrent relations of component skills to writing quality in grade 1

The three alternative models shown in Fig. 2 were fitted to the data. For the handwriting fluency latent variable, the loadings were strong (ps < .001; see Fig. 4). The first model, Fig. 2a, hypothesized that transcription and higher order cognitive skills are directly related to writing quality, whereas foundational cognitive skills and oral language skills are indirectly related to writing. This model had an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (17) = 18.56, p = .35, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03. In Fig. 2b, vocabulary and grammatical knowledge were hypothesized to be directly related to writing quality in Grade 1 over and above higher order cognitive skills and transcription skills. The model fit was also good, χ2 (15) = 15.73, p = .40, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03. In Fig. 2c, working memory and attention were hypothesized to directly relate to writing quality in Grade 1 over and above all the other language, cognitive, and transcription skills, and the model fit was also good, χ2 (15) = 15.96, p = .38, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03. Chi square difference tests showed that Fig. 2a was not different from Fig. 2b, Δχ2 = 2.83, Δdf = 2, p = .24, or Fig. 2c, Δχ2 = 2.6, Δdf = 2, p = .27. Figure 2b and c are not nested models, and therefore, their model fits cannot be compared using the Chi square difference test. Inspection of the path coefficients showed that the direct focal paths in Fig. 2b (vocabulary and grammatical knowledge) and Fig. 2c (working memory and attention) were not statistically significant. Therefore, Fig. 2a was chosen as the final model for parsimony. In other words, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, working memory, and attention were not directly related to writing quality over and above higher order cognitive skills and transcription skills.

Standardized path coefficients for the final model for Grade 1 writing. Statistically significant paths (p < .05) are indicated by solid lines; nonsignificant paths are indicated by dashed lines. G1 = Grade 1; ToM = theory of mind; Monitor = comprehension monitoring; Handwrite = handwriting fluency; Grammar = grammatical knowledge

Standardized path coefficients of the final model for Grade 1 are shown in Fig. 4. None of the higher order cognitive skills were independently related to writing (ps ≥ .63) after accounting for transcription skills. Spelling (β = .25, p = .002) and handwriting fluency (β = .32, p < .001) were both independently related to writing quality. Vocabulary was weakly to moderately related to all the higher order cognitive skills and transcription skills (.17 ≤ βs ≤ .43, ps ≤ .02). Grammatical knowledge was also weakly but significantly related to them (.15 ≤ βs ≤ .22, ps ≤ .03) with an exception for spelling (β = .04, p = .56). Working memory was moderately related to vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (.40 ≤ γs ≤ .42, ps ≤ .01) and weakly but directly related to higher order cognitive skills (.14 ≤ γs ≤ .24, ps ≤ .02). Attention was weakly related to vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, spelling, and handwriting fluency (.19 ≤ γs ≤ .23, ps ≤ .002). In addition to the direct effects of transcription skills on writing quality, indirect effects of working memory, attention, vocabulary, and grammatical knowledge via transcription skills were as follows: .08 for grammatical knowledge, .12 for working memory, .19 for attention, and .20 for vocabulary.

Longitudinal relations of component skills to writing quality

In order to examine the relations of component skills in Grade 1 to writing quality in Grade 3, the three alternative models shown in Fig. 3 were fitted to the data. Model fit was excellent for Fig. 3a, χ2 (22) = 30.58, p = .10, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .04; for Fig. 3b, χ2 (20) = 30.39, p = .06, CFI = .99, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .04; and for Fig. 3c, χ2 (20) = 22.35, p = .32, CFI = 1.00, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03. Chi square difference tests revealed that Fig. 3c is superior to both Fig. 3a, Δχ2 = 8.23, Δdf = 2, p = .02, and Fig. 3b, Δχ2 = 8.04, Δdf = 2, p = .02. Therefore, Fig. 3c was chosen as the final model.

Standardized path coefficients are presented in Fig. 5. Inference (β = .22, p = .007) and spelling (β = .32, p < .001) were independently related to writing quality in Grade 3. Working memory in Grade 1 was also directly related to writing quality in Grade 3 (γ = .19, p = .008) as well as indirectly related via oral language skills, inference, and spelling. Theory of mind and comprehension monitoring were not independently related to Grade 3 writing (ps ≥ .20). Handwriting fluency was not independently related to Grade 3 writing quality (β = .11, p = .25) after accounting for its contribution to Grade 1 writing. Grade 1 writing was also not independently related to Grade 3 writing quality (β = -.03, p = .71) after accounting for the contributions of Grade 1 component skills. The relations of attention, vocabulary, and grammatical knowledge to higher order cognitive skills and transcription skills were similar to those in Grade 1. The total effect of working memory on Grade 3 writing was .30 (.19 direct effect + .11 indirect effect). The indirect effects of variables on Grade 3 writing quality were as follows: .05 for grammatical knowledge, .11 for working memory, and .22 for vocabulary, and .27 for attention,

Standardized path coefficients for the final model for Grade 3 writing. Statistically significant paths (p < .05) are indicated by solid lines; nonsignificant paths are indicated by dashed lines. G1 = Grade 1; G3 = Grade 3; ToM = theory of mind; Monitor = comprehension monitoring; Handwrite = handwriting fluency; Grammar = grammatical knowledge

Discussion

DIEW extends previous theoretical models of developmental writing by specifying structural relations among component skills as well as incorporating higher order cognitive skills, background knowledge, and motivation and affect as component skills. The present study replicates and extends a previous investigation of DIEW with English-speaking children (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017) in two ways: The present study (a) used data from children who speak and learn to write in a language that is highly different from English (i.e., Korean) and (b) investigated differential relations of component skills as a function of development (the developmental hypothesis) using longitudinal data. Specifically, our foci in the present study were to examine DIEW and longitudinal and differential relations of component skills, including higher order cognitive skills, to later writing, using data from Korean-speaking children.

Generalizability of DIEW to Korean-speaking children

Overall, DIEW fit the data well for Korean-speaking children, supporting the generalizability of DIEW to Korean. The component skills were related to writing in Grades 1 and 3 as shown in the bivariate correlations, with magnitudes ranging from .14 to .52 (Table 2). The roles of component skills in writing were also supported by the finding that Grade 1 writing was no longer related to G3 writing once the contributions of components skills in Grade 1 were accounted for (see Fig. 5; see also Kent, Wanzek, Petscher, Al Otaiba, & Kim, 2014, for similar results). However, whereas some component skills were directly related, others such as attention, vocabulary, and grammatical knowledge were indirectly related to writing. Indirect effects as measured by standardized path coefficients were not minimal, particularly for attention (.19 to .27) and vocabulary (.20 to .22). The contributions of vocabulary and grammatical knowledge to writing are convergent with previous studies (Kim et al., 2011, 2015a; Olinghouse, 2008), but also divergent in that their effects were indirect, whereas previous studies showed direct (or unique) relations. The discrepancy in terms of direct and indirect relations is likely attributed to differences in study design. For example, in the present study, higher order cognitive skills were accounted for, whereas they were not in previous investigations.

The present findings also underscore the contribution of attention to writing. Attention or attentional control is included in the not-so-simple view of writing as part of the self-regulation construct (see Berninger & Winn, 2006) and in DIEW as part of executive function. However, only a few studies have empirically investigated its role in writing. Hooper and his colleagues (2011) found that an executive function latent variable that included attention and working memory was related to writing after accounting for fine motor skill, word reading, and rapid automatized naming. Kent and his colleagues (2014) also showed that attention in kindergarten predicted writing quality in Grade 1 for English-speaking children. The present study extended these previous studies by showing the multiple pathways by which attention is indirectly related to writing (i.e., via vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, and transcription skills). Taken together, these studies demonstrate the significant role of attention in writing skills.

Longitudinal relations: developmental hypothesis

The present findings highlight the differential roles of component skills as a function of development. In Grade 1, only transcription skills were directly related to writing, and the other component skills were not directly related to writing after accounting for their contributions via transcription skills. For Grade 3 writing, inference and spelling (but not handwriting fluency) had direct relations to writing; working memory had both a direct relation to writing and indirect relation to writing via other skills (vocabulary, inference, and spelling). While these results support the well-established role of transcription skills for developing writers (e.g., Abbott & Berninger, 1993; Graham et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2011, 2015a; Kim & Schatschneider, 2017), we believe that the different pattern of results in Grades 1 and 3 suggests the developmental nature of relations. During the very beginning phase of writing development in Grade 1, transcription skills play a large constraining role, creating a bottleneck phenomenon, to the extent that the roles of the other component skills are muted: Transcription skills completely mediated the relation of working memory to writing in Grade 1. In Grade 3, however, the constraining role of transcription skills is reduced (e.g., the relation of handwriting fluency to Grade 3 writing was .11, but to Grade 1 writing was .32), allowing the contributions of lower order domain-general cognition, working memory, and higher order cognitive skills such as inference to writing. Indeed, the total effect of working memory on writing increased from .12 for Grade 1 writing to .30 for Grade 3 writing, primarily due to working memory’s direct relation to writing in Grade 3.

The independent relation of inference to writing even for beginning writers is worth noting. Although speculations have been made about the roles of reasoning and perspective taking in developmental writing (Applebee, 1984; McCutchen, 2000), these have not been investigated for beginning writers until recently. The present findings are convergent with a study with English-speaking children in Grade 1 (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017) but also divergent from it because in the present study, the relation of inference to writing was found for Grade 3 writing, but not for Grade 1 writing. We speculate that the direct relation of inference to writing in Grade 3 but not in Grade 1 can be explained by the developmental hypothesis noted above. The fact that Grade 1 inference is independently related to Grade 3 writing, but not Grade 1 writing, indicates that although the importance of children’s higher order cognitive skills in writing skills may not be readily apparent at a particular point of development (e.g., in Grade 1), this does not negate the importance of these skills in writing development. It is unclear, however, why inference was related to writing in Grade 1 for English-speaking children, but not for the present sample of Korean-speaking children in Grade 1. A future cross-linguistic study is needed.

The other higher order cognitive skills, perspective taking and monitoring, were not independently related to writing after accounting for the other variables in the model. Although these findings are similar to recent findings with English-speaking first graders (Kim & Schatschneider, 2017), they also contrast with previous evidence on the unique contribution of monitoring to writing. Limpo and Alves (2013) operationalized monitoring via detection and correction of inconsistent sentences and found it to be independently related to writing. However, there are several differences between Limpo and Alves’s study and the present study: (a) the former included older students in Grades 4 to 9, whereas the present study examined students in Grades 1 and 3; (b) the monitoring task in the former study was administered in the context of reading (students read inconsistent texts and corrected them in writing), whereas the monitoring task in the present study was in an oral language context; and (c) the former study did not include other higher order skills in the statistical models, whereas the present study did. Given these differences, reasons for the discrepant findings for the role of monitoring in writing are unclear. One possibility is that perspective taking and monitoring may play unique roles beyond the beginning phase of writing development examined in the present study. For instance, Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) found that on average, students at a more advanced writing phase (e.g., in Grade 7) use the “knowledge transforming” strategy where they adjust the content and the form of the text according to their communicative goal. In contrast, the primary writing strategy for beginning writers is “knowledge telling” where the writer’s focus is to encode what they know (their knowledge) in print, without attention to the content and form for a specific communicative goal. Perhaps, higher order cognitive skills such as perspective taking and monitoring play more prominent roles for the knowledge transforming strategy. Future studies with children in different developmental phases can shed light on this speculation.

Limitations, future directions, and implications

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting the present findings. First, the sample in the present study came from a single school, primarily serving children from middle-class and low-middle-class backgrounds. A future replication with a more diverse sample is warranted. Second, the majority of constructs were measured using single tasks due to time and resource constraints. Therefore, in future studies, it will be ideal to measure each construct with multiple tasks to minimize measurement error. Also it will be ideal to include other component skills of writing. Although the component skills in the present study were relatively comprehensive, previous studies have reported additional contributors such as background knowledge, including both content knowledge and genre knowledge (Olinghouse & Graham, 2009; Olinghouse et al., 2015); discourse oral language (Berninger & Abbott, 2010; Kim et al., 2015a; Kim & Schatschneider, 2017); and motivation/affect factors (e.g., Graham et al., 2007). Finally, given the correlational nature of the study, causal conclusions are limited. Therefore, future studies are warranted to investigate whether instruction on the included component skills causally improves writing.

The present study adds to growing evidence about the direct and indirect contributions of component skills to writing, using longitudinal data from Korean-speaking beginning writers, and indicates the importance of specifying and examining structural relations among component skills. Future efforts are certainly needed to replicate and extend the present study with children in different (e.g., more advanced) stages of writing development and in different languages.

References

Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (1993). Structural equation modeling of relationships among developmental skills and writing skills in primary- and intermediate-grade writers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 478–508.

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Alonzo, C. N., Yeomans-Maldonado, C., Murphy, K. A., Bevens, B., & LARRC. (2016). Predicting second grade listening comprehension using prekindergarten measures. Topics in Language Disorders, 36, 3123–3333.

Applebee, A. N. (1984). Writing and reasoning. Review of Educational Research, 54, 577–596.

Arfe, B., Dockrell, J. E., & De Bernardi, B. (2016). The effect of language-specific factors on early written composition: The role of spelling, oral language and text generation skills in a shallow orthography. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29, 501–527.

Aro, M., & Wimmer, H. (2003). Learning to read: English in comparison to six more regular orthographies. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716403000316.

Astington, J., & Jenkins, J. (1999). A longitudinal study of the relation between language and theory of mind development. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1311–1320.

Babayiğit, S. (2014). Contributions of word-level and verbal skills to written expression: Comparison of learners who speak English as a first (L1) and second language (L2). Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27, 1207–1229.

Babayiğit, S., & Stainthorp, R. (2010). Component processes of early reading, spelling, and narrative writing skills in Turkish: A longitudinal study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23, 539–568.

Baker, L. (1984). Children’s effective use of multiple standards for evaluating their comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 588–597.

Beaufort, A. (2004). Developmental gains of a history major: A case for building a theory of disciplinary writing expertise. Research in the Teaching of English, 39, 136–185.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Berninger, V. W., & Abbott, R. D. (2010). Discourse-level oral language, oral expression, reading comprehension, and written expression: Related yet unique language systems in grades 1, 3, 5, and 7. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 635–651.

Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., Graham, S., & Richards, T. (2002). Writing and reading: Connections between language by hand and language by eye. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940203500104.

Berninger, V. W., Vaughn, K. B., Graham, S., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., Rogan, L. W., et al. (1997). Treatment of handwriting problems in beginning writers: Transfer from handwriting to composition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 652–666.

Berninger, V. W., & Winn, W. D. (2006). Implications of advancements in brain research and technology for writing development, writing instruction, and educational evolution. In C. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 96–114). New York: Guilford.

Berninger, V. W., Yates, C. W., Cartwright, A., Rutberg, J., Remy, E., & Abbott, R. (1992). Lower-level developmental skills in beginning writing. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4, 257–280.

Bianco, M., Bressoux, P., Doyen, A. L., Lambert, E., Lima, L., Pellenq, C., et al. (2010). Early training in oral comprehension and phonological skills: Results of a three-year longitudinal Study. Scientific Studies of Reading, 14, 211–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430903117518.

Bock, J. K. (1982). Toward a cognitive psychology of syntax: Information processing contributions to sentence formulation. Psychological Review, 89, 1–47.

Bourdin, B., & Fayol, M. (1994). Is written language production more difficult than oral language production? A working memory approach. International Journal of Psychology, 29, 591–620.

Caillies, S., & Sourn-Bissaoui, S. (2008). Children’s understanding of idioms and theory of mind development. Developmental Science, 11, 703–711.

Carrow-Woolfolk, E. (1999). Comprehensive assessment of spoken language. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessment.

Carvalho, J. B. (2002). Developing audience awareness in writing. Journal of Research in Reading, 25, 271–282.

Cho, J.-R. (2009). Syllable and letter knowledge in earlier Korean Hangul reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 938–947.

Cho, J.-R., McBride-Chang, C., & Park, S.-G. (2008). Phonological awareness and morphological awareness: Differential associations to regular and irregular word recognition in early Korean Hangul readers. Reading and Writing, 21, 255–274.

Coker, D. L. (2006). Impact of first-grade factors on the growth and outcomes of urban schoolchildren’s primary-grade writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 471–488.

Craig, S., & Lewandowsky, S. (2012). Whichever way you choose to categorize, working memory helps you learn. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65, 439–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2011.608854.

Daneman, M., & Merikle, P. M. (1996). Working memory and language comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 422–433.

De Temple, J. M., Wu, S.-F., & Snow, C. E. (1991). Papa pig just left for pigtown: Children’s oral and written picture descriptions under varying instructions. Discourse Processes, 14, 469–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539109544797.

Dromi, E., & Berman, R. A. (1986). Language-specific and language-general in developing syntax. Journal of Child Language, 13, 371–387.

Eccles, J. S. (2005). Subjective task value and the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 105–121). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153.

Elbow, P. (1981). Writing with power. New York: Oxford University Press.

Florit, E., Roch, M., Altoè, G., & Levorato, M. C. (2009). Listening comprehension in preschoolers: The role of memory. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27, 935–951.

Florit, E., Roch, M., & Levorato, M. C. (2014). Listening text comprehension in preschoolers: A longitudinal study on the role of semantic components. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27, 793–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9464-1.

Gathercole, S. E., & Baddeley, A. D. (1990). The role of phonological memory in vocabulary acquisition: A study of young children learning new names. British Journal of Psychology, 81, 439–454.

Gathercole, S. E., Service, E., Hitch, G. J., Adams, A., & Martin, A. J. (1999). Phonological short-term memory and vocabulary development: Further evidence on the nature of the relationship. Cognitive Psychology, 13, 65–77.

Graham, S., Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., & Whitaker, D. (1997). Role of mechanics in composing of elementary school students: A new methodological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.1.170.

Graham, S., Berninger, V., & Fan, W. (2007). The structural relationship between writing attitude and writing achievement in first and third grade students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32, 516–536.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2017). Reading and writing connections: How writing can build better readers (and vice versa). In Improving reading and reading engagement in the 21st century (pp. 333–350). Singapore: Springer.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Chorzempa, B. F. (2002). Contribution of spelling instruction to the spelling, writing, and reading of poor spellers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 669–686.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & McKeown, D. (2013). The writing of students with LD and a meta-analysis of SRSD writing intervention studies: Redux. In L. Swanson, K. R. Harris, & S. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of learning disabilities (2nd ed.). MY: Guilford Press.

Gwon, E.-Y., & Lee, H.-J. (2012). Children’s development of lying, false belief and executive function. Korean Journal of Developmental Psychology, 25, 165–184.

Hayes, J. R. (2006). New directions in writing theory. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 28–40). New York: Guilford.

Hayes, J. R., & Chenoweth, N. A. (2007). Working memory in an editing task. Written Communication, 24, 283–294.

Hooper, S. R., Costa, L.-J., McBee, M., Anderson, K. L., Yerby, D. C., Knuth, S. B., et al. (2011). Concurrent and longitudinal neuropsychological contributors to written language expression in first and second grade students. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 24, 221–252.

Howlin, P., Baron-Cohen, S., & Hadwin, J. (1999). Teaching children with autism to mind read. Chichester: Wiley.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Juel, C., Griffith, P. L., & Gough, P. B. (1986). Acquisition of literacy: A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78, 243–255.

Kent, S., Wanzek, J., Petscher, Y., Al Otaiba, S., & Kim, Y.-S. (2014). Writing fluency and quality in kindergarten and first grade: The role of attention, reading, transcription, and oral language. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27, 1163–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9480-1.

Kim, Y.-S. (2011). Considering linguistic and orthographic features in early literacy acquisition: Evidence from Korean. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36, 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.06.003.

Kim, Y.-S. (2015a). Language and cognitive predictors of text comprehension: Evidence from multivariate analysis. Child Development, 86, 128–144.

Kim, Y.-S., Al Otaiba, S., Folsom, J. S., Greulich, L., & Puranik, C. (2014a). Evaluating the dimensionality of first grade written composition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0152).

Kim, Y.-S., Al Otaiba, S., Puranik, C., Folsom, J. S., Greulich, L., & Wagner, R. K. (2011). Componential skills of beginning writing: An exploratory study. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.06.004.

Kim, Y.-S., Al Otaiba, S., Wanzek, J., & Gatlin, B. (2015a). Towards an understanding of dimension, predictors, and gender gaps in written composition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037210.

Kim, Y.-S., Apel, K., & Al Otaiba, S. (2013a). The relation of linguistic awareness and vocabulary to word reading and spelling for first-grade students participating in response to instruction. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 44, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2013/12-0013).

Kim, Y.-S., Park, C., & Park, Y. (2013b). Is academic language use a separate dimension in begining writing? Evidence from Korean children. Learning and Individual Differences, 27, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.06.002.

Kim, Y.-S., Park, C., & Wagner, R. K. (2014b). Is oral/text reading fluency a “bridge” to reading comprehension? Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27, 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9434-7.

Kim, Y.-S., & Petscher, Y. (2013). Considering word characteristics for spelling accuracy: Evidence from Korean-speaking children. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.08.002.

Kim, Y.-S., & Phillips, B. (2014). Cognitive correlates of listening comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 49, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.74.

Kim, Y.-S. G. (2015b). Developmental, component-based model of reading fluency: An investigation of word-reading fluency, text-reading fluency, and reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 50, 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.107.

Kim, Y.-S. G. (2016). Direct and mediated effects of language and cognitive skills on comprehension or oral narrative texts (listening comprehension) for children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.08.003.

Kim, Y.-S. G. (2017a). Why the simple view of reading is not simplistic: Unpacking the simple view of reading using a direct and indirect effect model of reading (DIER). Scientific Studies of Reading, 21, 310–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2017.1291643.

Kim, Y.-S. G. (2017b). Multicomponent view of vocabulary acquisition: An investigation with primary grade children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 162, 120–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.05.004.

Kim, Y.-S. G. (in press). Interactive dynamic literacy model: An integrative theoretical framework for reading and writing relations. In R. Alves, T. Limpo, & M. Joshi (Eds.), Reading-writing connections: Towards integrative literacy science. Netherlands: Springer.

Kim, Y.–S. G., Cho, J.-R., & Park, S.-G. (in press). The Korean Test of Language and Literacy Diagnosis (K-TOLLD). Korea Guidance. [in Korean]

Kim, Y.-S. G., Park, C., & Park, Y. (2015b). Dimensions of discourse-level oral language skills and their relations to reading comprehension and written composition: An exploratory study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 28, 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9542-7.

Kim, Y.-S. G., & Schatschneider, C. (2017). Expanding the developmental models of writing: A direct and indirect effects model of developmental writing (DIEW). Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000129.

Klassen, R. (2002). Writing in early adolescence: A review of the role of self-efficacy beliefs. Educational Psychology Review, 14, 173–203. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014626805572.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, 293–323.

Lepola, J., Lynch, J., Laakkonen, E., Silvén, M., & Niemi, P. (2012). The role of inference making and other language skills in the development of narrative discourse-level oral language in 4- to 6-year old children. Reading Research Quarterly, 47, 259–282.

Limpo, T., & Alves, R. A. (2013). Modeling writing development: Contribution of transcription and self-regulation to Portuguese students’ text generation quality. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 401–413.

McBride-Chang, C., Cho, J.-R., Liu, H., Wagner, R. K., Shu, H., Zhou, A., et al. (2010). Changing models across cultures: Associations of phonological awareness and morphological structure awareness with vocabulary and word recognition in second graders from Beijing, Hong Kong, Korea, and the United States. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92, 140–160.

McCutchen, D. (1986). Domain knowledge and linguistic knowledge in the development of writing ability. Journal of Memory and Language, 25, 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596x(86)90036-7.

McCutchen, D. (2000). Knowledge, processing, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational Psychologist, 35, 13–23.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2013). Mplus 7.1. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén.

Nagy, W., Berninger, V. W., & Abbott, R. D. (2006). Contributions of morphology beyond phonology to literacy outcomes of upper elementary and middle-school students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.134.

Naigles, L. R., & Leher, N. (2002). Language-general and language-specific influences on children’s acquisition of argument structure: A comparison of French and English. Journal of Child Language, 29, 545–566.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2012). The nation’s report card: Writing 2011(NCES 2012–470). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Norbury, C. F. (2005). The relationship between theory of mind and metaphor: Evidence from children with language impairment and autistic spectrum disorder. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 23, 383–399.

Olinghouse, N. G. (2008). Student- and instruction-level predictors of narrative writing in third-grade students. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 21, 3–26.

Olinghouse, N. G., & Graham, S. (2009). The relationship between discourse knowledge and the writing performance of elementary-grade students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 37–50.

Olinghouse, N. G., Graham, S., & Gillespie, A. (2015). The relationship of discourse and topic knowledge to fifth graders’ writing performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 391–406.

Olive, T. (2004). Working memory in writing: Empirical evidence from the dual-task technique. European Psychologist, 9, 32–42.

Pajares, F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: A review of the literature. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19, 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308222.

Perin, D., Keselman, A., & Monopoli, M. (2003). The academic writing of community college remedial students: Text and learner variables. Higher Education, 45, 19–42.

Radach, R., Kennedy, A., & Rayner, K. (2004). Eye movements and information processing during reading. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Ryder, P. M., Vander Lei, E. U., & Roen, D. H. (1999). Audience considerations for evaluating writing. In C. R. Cooper & L. Odell (Eds.), Evaluating writing (pp. 93–113). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Sáez, L., Folsom, J. S., Al Otaiba, S., & Schatschneider, C. (2012). Relations among student attention behaviors, teacher practices, and beginning word reading skill. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45, 418–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411431243.

Scadamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1985). Development of dialectical processes in composition. In D. R. Olson, N. Torrance, & A. Hildyard (Eds.), Literacy, language and learning: The nature and consequences of reading and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, H., & Ruddell, R. (Eds.). (1985). Theoretical models and processes of reading (3rd ed.). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Swanson, J. M., Schuck, S., Mann, M., Carlson, C., Hartman, K., Sergeant, J. A., et al. (2006). Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: The SNAP and SWAN rating scales. Retrieved from http://www.adhd.net/SNAP_SWAN.pdf.

Tompkins, V., Guo, Y., & Justice, L. M. (2013). Inference generation, story comprehension, and language in the preschool years. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 26, 403–429.

Treiman, R. (1993). Beginning to spell: A study of first grade children. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valle, A., Massaro, D., Castelli, I., & Marchetti, A. (2015). Theory of mind development in adolescence and early adulthood: The growing complexity of recursive thinking ability. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11, 112–124.

Verhagen, J., & Leseman, P. (2016). How do verbal short-term memory and working memory relate to the acquisition of vocabulary and grammar? A comparison between first and second language learners. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 65–82.

Wagner, R. K., Puranik, C. S., Foorman, B., Foster, E., Tschinkel, E., & Kantor, P. T. (2011). Modeling the development of written language. Reading and Writing, 24, 203–220.

Wollman-Bonilla, J. E. (2001). Can first-grade writers demonstrate audience awareness? Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 184–201.

Funding

Funding was provided by Institute of Education Sciences (Grant No. R305A130131) and National Research Foundation of Korea (Grant No. NRF-2013S1A3A2054928).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, YS.G., Park, SH. Unpacking pathways using the direct and indirect effects model of writing (DIEW) and the contributions of higher order cognitive skills to writing. Read Writ 32, 1319–1343 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9913-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9913-y