Abstract

Purpose

There is a growing population of older people living alone within the context of dramatic population ageing and changing living arrangements. However, little is known about the quality of life (QoL) of older people living alone in Mainland China. This study aimed to investigate QoL and its related factors among Chinese older people who live alone.

Methods

A stratified random cluster sample of 521 community-dwelling older people living alone in Shanghai completed a structured questionnaire through face-to-face interviews. QoL was measured using the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire. Other data collected included self-rated health, physical health, cognitive function, depression, functional ability, loneliness, social support, physical activity, health services satisfaction, satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions and socio-demographic variables.

Results

Older people living alone in Mainland China rated social relationships and financial circumstances as sources of low satisfaction within their QoL. Multiway analysis of variance showed that satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions, self-rated health, functional ability, depression, economic level, social support, loneliness, previous occupation and health services satisfaction were independently related to QoL, accounting for 68.8 % of the variance. Depression and previous occupation had an interaction effect upon QoL.

Conclusions

This study identified nine factors influencing the QoL of older people living alone in Mainland China. Interventions to increase satisfaction with dwelling conditions, improve economic level, social support and functional ability, decrease loneliness and depression and improve health services satisfaction appear to be important for enhancing their QoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population ageing is unprecedented all over the world [1]. The population of older people is growing by 2 % each year, considerably faster than the population as a whole, and is expected to continue growing faster than other age groups with the annual growth rate reaching 2.8 % in 2025–2030 [2]. It is estimated that the number of older people will exceed the number of children for the first time in 2045, and the proportion of older people will rise to 22 % in 2050 [1, 3]. This means that 1 in 5 people will be 60 years and older by the year 2050 and that there will be 2 billion older people alive in the world, tripling the number of 1950.

One of the important features of population ageing is the increase in older people living alone which is predicted to accelerate quickly towards the middle of the twenty-first century [4]. With changes in lifestyle and family values, improvement in living conditions and the increase in family nuclearization and population flow of younger people, living arrangements are changing and the number of older people living alone is increasing. The proportion of worldwide older people aged 60 years and above living alone is now estimated to be 14 % [1].

Older people living alone have been identified as an at-risk group for poorer physical and mental health, more social isolation, less social support and lower quality of life (QoL) and therefore warrant specific attention [5–9]. With the population ageing, the goal of a prolonged life has begun to shift to achieving a life ‘worth living’, that is, adding ‘quality’ to life to improve older people’s health, independence, activity, and social and economic participation [10]. Assessment of older people’s QoL has become an important public health issue and the stated end-point of policies aiming to promote active ageing [11]. Some studies focusing upon the QoL and its related factors of older people living alone have been conducted in developed countries and in Hong Kong and Taiwan. For example, Lee interviewed 109 older people living alone in Hong Kong and reported that mental health, life satisfaction, the number of days in hospitals, self-esteem and age were factors related to QoL [7]. Lin et al. [8] explored perceived QoL and related factors in 192 older people living alone in Taiwan. Education level, residential area, the number of chronic diseases, self-rated health, depression, social support and socio-economic status were identified as factors influencing different dimensions of QoL. The findings of Yahaya et al.’s [12] study revealed that self-rated health, gender, occupation and education level were important factors related to the QoL of older Malaysians living alone. A recent study which explored the QoL of older people living alone in Italy reported that depression, having no caregiver and never married were associated with a lower QoL [13].

However, few studies of older people living alone have been conducted in Mainland China where interdependence, filial piety and group harmony are emphasized. Considering that the experienced QoL depends on the context of the culture and value systems in relation to people’s goals, expectations, standards and concerns [14], the findings derived from studies in developed countries may not be generalizable to Mainland China.

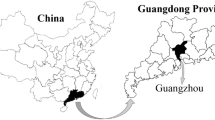

Shanghai was the first city in China to experience an ageing population and has the highest proportion of older people [15]. The process of population ageing in Shanghai has taken place so sharply that its older population increased from 10.0 to 18.0 % within 20 years, a transition that has taken about 100 years in many European countries [16]. By the end of 2010, Shanghai’s older people aged 60 years and above had reached 3.3 million accounting for 23.4 % of Shanghai’s total population [17]. This proportion is much higher than the national average of 13.3 % [18]. This study, therefore, aimed to investigate QoL and its related factors among older people living alone in Shanghai, China. The study results will help to provide an in-depth understanding of the QoL of older people living alone in Shanghai, identify subgroups who are at greater risk of a lower QoL so that their needs may be addressed through appropriate health and social care interventions.

Methods

Design, setting and sample

A cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted in Chongming County, a district with a relatively large proportion of older people living alone in Shanghai, using a stratified random cluster sampling method. All towns were stratified into two groups reflecting their socio-economic status (low and high) with one town being randomly selected from each group. A number of communities were randomly selected from each town to achieve the required sample size, which was calculated using power analysis assuming an α of 0.05, a power of 0.80 and a medium effect size for multivariate analysis, and anticipating a 30 % attrition rate of the potential sample of older people to a questionnaire survey [19]. Nine communities (low socio-economic status: n = 4; high socio-economic status: n = 5) were selected and people who were 60 years and older, living alone in these communities, able to communicate in Mandarin or Chongming dialect, and had no moderate or severe cognitive impairment indicated by a score under 6 on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) [20] were recruited to the sample. In all, 640 older people were identified, of whom 22 declined to participate, 97 were ineligible because of poor cognitive function and 521 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 95.9 %.

Measurements

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was QoL which was measured using the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL) [10]. The OPQOL has been validated in ethnically diverse community-dwelling older people in England. The original version of the questionnaire comprises 35 items with the participants being asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each item by choosing one of five possible options from ‘strongly disagree = 1’ to ‘strongly agree = 5’ with a higher score indicating a higher QoL.

The Chinese version of the OPQOL was developed for this study. Its validity and reliability have been tested within the 521 subjects, and the results have been reported elsewhere [21]. Overall, the Chinese OPQOL is an appropriate measurement tool for assessing the QoL of older people in China. It comprises 36 items reflecting eight dimensions of QoL, namely leisure and social activities, psychological well-being, health and independence, financial circumstances, social relationships, home and neighbourhood, culture/religion and safety. The convergent validity and discriminant validity were satisfactory. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of overall OPQOL and most of its dimensions exceeded 0.70. It also demonstrated good stability with the intra-class correlation coefficient of overall OPQOL and most of its dimensions exceeding 0.60.

Independent variables

The independent variables examined in this study included self-rated health, physical health, cognitive function, depression, functional ability, loneliness, social support, physical activity, health services satisfaction, satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions and socio-demographic variables. These variables were selected as independent variables because they have been identified in a systematic review as important factors of QoL of Chinese older people [22]. Self-rated health was measured by asking ‘How would you rate your current health status?’ on a 5-point scale from ‘very good’ to ‘very poor’. Physical health was measured in terms of the presence of chronic diseases, the number of chronic diseases and the presence of acute diseases in the previous 4 weeks.

The SPMSQ was used to assess cognitive function [20]. It comprises 10 items testing some intellectual areas with one point being given to each correct answer, yielding a score range of 0–10. As cognitive function can be influenced by education, the education level was taken into account in the scoring [20]. An adjusted score of 8–10 indicated intact cognitive function, 6–7 indicated mild cognitive impairment, 3–5 indicated moderate cognitive impairment and 2 or under indicated severe cognitive impairment. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the SPMSQ in this study was 0.71.

Depression was measured using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [23]. This scale uses a dichotomous response format of ‘yes’ or ‘no’. One point is assigned when people indicate a positive answer to the item representing depressive symptoms. The total score ranges from 0 to 15 with a higher score indicating a higher level of depression. A cut-off point of 8 was used in this study with the participants who scored equal to or greater than 8 being considered as having depression [24]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale was 0.82 in this study.

Functional ability was measured with the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale [25]. The ADL Scale includes 14 items with two composites: physical self-maintenance (PSM) Scale (6 items) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) Scale (8 items). The former assesses basic physical functioning such as feeding, dressing and grooming, and the latter assesses more complicated skills such as using the telephone, shopping and doing housework. For each item, the participants were asked to rate on a 4-point scale from performing the activity totally independent to totally dependent with a lower score indicating a greater level of functional ability. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study was 0.92.

The UCLA Loneliness Scale version 3 (RULS-V3) was used to measure the participants’ loneliness level [26]. This scale comprises 20 items with each item being rated on a 4-point scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always) yielding a score range of 20–80. The participants who scored 20–34, 35–49, 50–64 and 65–80 were considered to have a low level, moderate level, moderately high level and high level of loneliness, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the RULS-V3 was 0.89.

The Social Support Rate Scale (SSRS) assesses people’s social support level [27]. It comprises three dimensions, namely objective support, subjective support and support utilization, yielding a score range of 12–65 with a higher score indicating a higher level of social support. Considering that the participants were older people living alone, one item regarding living arrangements was deleted from the scale when it was used in this study. The modified scale had a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.76.

Physical activity was measured using self-report frequency of engaging in activities with different intensities. The participants who spent at least half an hour of moderate or/and strenuous exercise on at least 5 days per week were regarded as being adequate in physical activity [28]. Health services satisfaction was measured by one single question of ‘On the whole, how satisfied are you with the health services?’ using a 5-point scale from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’. Satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions was measured on a 5-point single-item scale from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’.

Data collection procedure

The study was granted ethical approval by King’s College London Research Ethics Committee. Information sheets were given to the 640 potential participants during door-to-door visits by 18 trained data collectors who were familiar with the older people and had experience in questionnaire surveys. Those who agreed to participate in the study (n = 618) were offered a face-to-face interview at their home or in community committee office. During the interview, the SPMSQ [20] was first administered to assess cognitive function with those scoring under 6 (n = 97) being excluded from further participation due to their poor cognitive function. Older people with good cognitive function (n = 521) signed a consent form and completed a structured questionnaire.

Data collection occurred between November 2011 and March 2012. Monthly meetings were held to review and discuss the data collection techniques. Frequent telephone contacts with data collectors were made to assess their data collection progress and to check whether they encountered any problems.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 16.0. Descriptive statistics including mean, medium, standard deviation (SD), score range, frequency and percentage were used to describe the participants’ characteristics. In order to investigate the factors related to QoL, bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted. The OPQOL is a Likert scale yielding ordinal data [29]. Therefore, the Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to explore the relationships between overall QoL and each independent variable. Subsequently, the variables which had statistical significant relationships with QoL in the bivariate analyses were entered into the multiway analysis of variance (ANOVA) model, which is suitable when independent variables are categorical and dependent variables are continuous [30]. Additionally, the original data of overall QoL were replaced with ranks (rank of QoL) to permit ANOVA. Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance (p > 0.05) suggested that the error variance of the independent factor was equal across groups, which signified the appropriateness for ANOVA model.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The majority of the participants were female (66.0 %), widowed (96.1 %) and had a low education level (87.7 %) (no formal education: 46.8 %; primary school: 40.9 %). Their age ranged from 60 to 99 years old with a mean age of 76.3 years (SD = 8.3). Most participants were peasants (78.3 %) and lived in a rural area (90.0 %). More than half of the participants (58.9 %) reported a low economic level (Table 1).

More than two-fifths of the participants (43.2 %) rated their health as good (38.8 %) or very good (4.4 %), and 15.2 % reported a poor health status (12.5 % for poor; 2.7 % for very poor). Nearly half of the participants (44.5 %) reported having a chronic disease with a range of 1–5 diseases (M = 1.7, SD = 0.9). Only 4.8 % reported that they had any acute disease in the previous 4 weeks. More than four-fifths of the 521 participants (87.1 %) had intact cognitive function. A total of 248 older people scored 8 or over on the 15-item GDS, indicating a depression prevalence of 47.6 %. Approximately three-quarters of the participants (72.0 %) had a high level of functional ability (Table 1).

The total score for the RULS-V3 ranged from 20–63 with the median of 45, indicating a moderate level of loneliness. The mean score on the SSRS was 30.5 (SD = 6.1) with a range from 15 to 51. As for physical activity, only 16.7 % of the participants reported adequate physical activity. In addition, the majority of the participants (63.9 %) reported being satisfied (61.8 %) or very satisfied (2.1 %) with their health services. Regarding satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions, 69.8 % of all participants felt satisfied (66.0 %) or very satisfied (3.8 %) with their dwelling conditions.

Quality of life of the participants

The distribution of each item in the OPQOL is set out in Table 2. Most participants (>80.0 %) rated highly on the following aspects of their QoL: having children around (85.2 %), the help from family, friends or neighbours (84.5 %), friendly neighbourhood (84.1 %), being healthy enough to get out and about (81.4 %), having someone who gave them love and affection (81.0 %) and feeling safe where they lived (81.0 %). On the other hand, more than three-quarters of the participants reported that they would have liked more companionship or contact with other people (77.5 %) and more people with whom to enjoy life (75.4 %). Almost three-quarters reported that they did not have enough money to pay for household repairs (73.5 %) and that the cost of things restricted their life (71.2 %), and more than half reported that they did not have enough money to afford healthcare expenses (59.7 %) and they could not afford to do things that they would enjoy (56.2 %) indicating that the participants were less satisfied with these aspects of their QoL.

Factors related to QoL

Age, education level, previous occupation, economic level, residential area, the presence of chronic diseases, the presence of acute diseases, cognitive function, depression, functional ability, self-rated health, physical activity, loneliness, social support, health services satisfaction and satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions had significant relationships with QoL in the bivariate analyses (Table 1).

In the ANOVA model, satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions, self-rated health, functional ability, depression, economic level, social support, loneliness, previous occupation and health services satisfaction were significantly associated with QoL, accounting for 68.8 % of the total variance (Table 3).

As can be seen from Table 4, the participants who were satisfied with their overall dwelling conditions and reported better health and a higher level of functional ability reported a higher QoL. Regarding the impact of economic level upon QoL, the participants with a low economic level reported the lowest QoL followed by those with a medium–low economic level. Those with a medium–high and high economic level reported the highest QoL, but there was no statistically significant difference between these two groups. In addition, social support, loneliness and health services satisfaction had some effect upon QoL. The participants who reported a higher level of social support, a lower level of loneliness and were satisfied with their health services reported a higher QoL.

Depression and previous occupation both had an impact upon QoL. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between these two factors. Generally, the participants having no depression reported a higher QoL. However, the effect of depression upon QoL varied across the different occupational groups (Table 5). Among those having no depression, the peasants reported a lower QoL than blue-collar workers and non-manual workers, and non-manual workers reported the highest QoL. However, among those having depression, the peasants had a significantly higher QoL than the other two occupational groups. The difference between blue-collar workers and non-manual workers regarding QoL was not significant.

Discussion

This study explored the QoL of older people living alone in Mainland China and its related factors. Most participants would have liked more companionship or more people with whom to enjoy life, although they agreed that their family, friends or neighbours would help them if needed and they had someone who gave them love and affection. These findings suggested that the participants were less satisfied with their social relationships within their QoL because these four items were allocated in the ‘social relationships’ dimension of the OPQOL. This further reflected the feeling of loneliness of the participants. Family members, friends or neighbours could give them help and love, but this kind of support was not enough to meet all that they desired, which was demonstrated by the finding that their overall social support level was low. In addition to social relationships, financial status was another dimension relating to their QoL with which many participants were less satisfied. Most of them reported that they did not have enough money to pay for household repairs with the cost of things restricting their life, they did not have enough money to afford healthcare expenses or to do things that they would enjoy. Compared with older people who lived with others, older people living alone were likely to receive less financial support and report more financial strain [31]. The economic deprivation may be more noticeable in the current context in China, where the rapid economic changes and increasing inflation have resulted in the rise of cost of living [32]. Together with the immature pension scheme and low income, older people living alone may face more financial challenges.

The finding that satisfaction with overall dwelling conditions had an important effect upon QoL is supported by previous research [7, 33]. As older people tend to have more restricted spaces than younger people, they are more likely to remain at home and spend much time there [33]. Having adequate housing with essential and satisfactory facilities may provide a sense of security, stability and attachment. In the Chinese context, having no place to live is one of the worst scenarios in old age [32]. Therefore, older people’s perceptions of their dwelling conditions tend to exert a major impact upon their QoL.

Health plays a dominant role in influencing people’s life satisfaction and happiness [34] and older people’s QoL. Self-rated health was the second most important factor with older people with a better self-rated health reporting a higher QoL, corroborating previous findings [12, 35, 36]. Functional ability was another health-related factor identified as independently associated with QoL. The participants who reported a higher level of functional ability were likely to report a higher QoL. Similar findings have been reported in previous research [35, 37]. Good functional ability is a sign of self-maintenance which helps older people maintain social contact with the outside world and participate in social activities [7]. Being able to do these things gives meaning to older people’s lives and consequently improves their QoL.

A number of studies have related economic level to QoL [36, 38, 39]. This also emerged in the current study with the participants’ QoL being different across the different economic levels. A lower level of economic status can exert strong negative effects upon older people by impairing their confidence in life, lowering self-esteem and reducing coping sources and eventually lead to a lower QoL [36]. Notably, however, there was no statistical difference in the reported QoL between the medium–high and high economic level groups. A possible explanation for this may be that economic status influences QoL only at the poverty level [36, 40]. Once people’s basic needs are met, the effect of economic status is less influential.

Similar to previous studies [41, 42], this study showed that social support was an important factor related to QoL with the participants reporting a higher level of social support having a higher QoL. It suggests that enhancing overall social support for older people living alone might be an effective way to improve their QoL. However, this study revealed a generally low level of social support for the participants compared with the Chinese norm [43], which calls for strategies to improve their social support level.

Loneliness was significantly associated with the QoL of older people living alone with those having a higher level of loneliness reporting a lower QoL. An extensive literature has noted the adverse impact of loneliness upon physical and psychological health, which may eventually impair QoL [44–46]. As the participants in this study reported a moderate level of loneliness, the findings imply a need to reduce loneliness.

This study found that satisfaction with health services was independently associated with QoL. A possible explanation may be that older people who were satisfied with their health services were more likely to perceive that they had received effective care which could improve their utilization of health services and adherence to treatment regimens and consequently tended to recover more easily from health problems and reported a higher QoL [47]. Another possible explanation is that satisfaction with the health services is a good proxy for subjective health perception [47, 48]. Therefore, older people who reported satisfaction with their health services had a better self-rated health and consequently reported a higher QoL.

Consistent with previous research [49–51], this study revealed that depression was a predominant factor contributing to a lower QoL. Compared with previous studies regarding depression in Chinese older people, the prevalence of depression in this study was higher [52] indicating the need for effective strategies to reduce depression. Additionally, a comprehensive assessment of depression and an in-depth analysis of older people’s ability to deal with depression are necessary, because there was an interaction effect between depression and previous occupation upon QoL which has not been reported previously. Some studies have revealed that older people who were in professional occupations before retirement were likely to have a higher QoL due to their higher socio-economic status compared with those who were in manual occupations [53, 54]. This was confirmed in the non-depressed group in this study with the non-manual workers reporting the highest QoL while the peasants reporting the lowest QoL. However, in the depressed group, the peasants reported the highest QoL, indicating that the effect of depression was far more pronounced in blue-collar workers and non-manual workers than in peasants.

Some limitations of this study should be born in mind. First, this study was a cross-sectional survey, and therefore, the causal relationships between the related factors and QoL could not be identified. Additionally, the measurement of QoL changes across different time spans was not possible due to the study design. Secondly, the sample was from an economically deprived and agriculture-dominated district of Shanghai. Thus, the findings may not be generalized to other older people living alone in other settings. Lastly, the self-report data may reflect socially desirable responses and recall bias.

Conclusions

This study is one of the few studies focusing upon the QoL of older people living alone in Mainland China. The results showed that Chinese older people living alone rated social relationships and financial circumstances as aspects which were important to their QoL, and they were less satisfied with these two aspects. Satisfactory dwelling conditions, good self-rated health, higher levels of functional ability, less depression, less financial strain, more social support, less loneliness and satisfactory health services were key factors for a higher QoL. By understanding the factors related to the QoL of older people living alone in Mainland China, health and social care providers and policy makers can develop strategies to improve QoL. This study suggests a need for Interventions and policy development addressing the concern of social support, loneliness, financial status and depression.

References

United Nations. (2009). World population ageing 2009. New York: United Nations.

United Nations. (2001). World population ageing: 1950–2050. New York: United Nations.

World Health Organization. (2008). WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Rolls, L., Seymour, J. E., Froggatt, K. A., & Hanratty, B. (2010). Older people living along at the end of life in the UK: Research and policy challenges. Palliative Medicine, 25(6), 650–657.

Casey, B., & Yamada, A. (2002). Getting older, getting poorer? A study of the earnings, pensions, assets and living arrangements of older people in nine countries. OECD labour market and social policy occasional papers, no. 60, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/345816633534. Accessed March 24, 2013.

Chou, K. L., & Chi, I. (2000). Comparison between elderly Chinese living alone and those living with others. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 33(4), 51–66.

Lee, J. J. (2005). An exploratory study on the quality of life of older Chinese people living alone in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 71(1–3), 335–361.

Lin, P. C., Yen, M. F., & Fetzer, S. J. (2008). Quality of life in elders living alone in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(12), 1610–1617.

World Health Organization. (1977). Prevention of mental disorders in the elderly. Copenhagen: World Health Organization.

Bowling, A. (2009). The psychometric properties of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire, compared with CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. doi:10.1155/2009/298950.

World Health Organization. (2002). Active ageing. A policy framework. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yahaya, N., Abdullah, S. S., Momtaz, Y. A., & Hamid, T. A. (2010). Quality of life of older Malaysians living alone. Educational Gerontology, 36(10–11), 893–906.

Bilotta, C., Bowling, A., Nicolini, P., Case, A., & Vergani, C. (2012). Quality of life in older outpatients living alone in the community in Italy. Health and Social Care in the Community, 20(1), 32–41.

The WHOQOL Group. (1995). The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409.

Chen, Z. L., & Chen, X. B. (2006). Discussion on situation of the ageing in Shanghai and its countermeasures. Chinese Health Service Management, 22(11), 671–673.

Zhang, L. (2010). Shanghai coming to grip with its aging population problems. EAI background brief, no. 517. http://www.eai.nus.edu.sg/BB517.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2013.

Gerontological Society of Shanghai. (2011). 2010 Shanghai monitored statistical information on population of the elderly & development of old age program. http://www.shanghaigss.org.cn/news_view.asp?newsid=7892. Accessed August 30, 2013.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2011). Major figures of the sixth national population census. http://www.stats.gov.cn/zgrkpc/dlc/yw/t20110428_402722384.htm. Accessed August 30, 2013.

Newton, R. R., & Rudestam, K. E. (1999). Your statistical consultant: Answers to your data analysis questions. California: Sage.

Pfeiffer, E. (1975). A Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 23(10), 433–441.

Chen, Y., Hicks, A., & While, A. E. (2013). Validity and reliability of the modified Chinese version of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL) in older people living alone in China. International Journal of Older People Nursing. doi:10.1111/opn.12042.

Chen, Y., Hicks, A., & While, A. E. (2013). Quality of life of older people in China: A systematic review. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 23(1), 88–100.

Sheikh, J. L., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist, 5(1–2), 165–173.

Boey, K. W. (2000). The use of GDS-15 among the older adults in Beijing. Clinical Gerontologist, 21(2), 49–60.

Lawton, M. P., & Brody, E. M. (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40.

Xiao, S. Y. (1999). The Social Support Rate Scale. In X. D. Ma, X. L. Wang, & H. Ma (Eds.), The handbook of Mental Health Rating Scales (pp. 127–131). Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Journal Press.

Haskell, W. L., Lee, I. M., Pate, R. R., Powell, K. E., Blair, S. N., Franklin, B. A., et al. (2007). Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 39(8), 1423–1434.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Zhong, R. Y. (2004). An analysis of the living condition of the elders living alone in Shanghai and the policy related. Journal of Social Science, 8, 66–70.

Tong, H. M., Lai, D. W. L., Zeng, Q., & Xu, W. Y. (2011). Effects of social exclusion on depressive symptoms: Elderly Chinese living alone in Shanghai. China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 26(4), 349–364.

Phillips, D. R., Siu, O. L., Yeh, A. G. O., & Cheng, K. H. C. (2005). The impacts of dwelling conditions on older persons’ psychological well-being in Hong Kong: The mediating role of residential satisfaction. Social Science and Medicine, 60(12), 2785–2797.

Michalos, A. C., Zumbo, B. D., & Hubley, A. (2000). Health and the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 51(3), 245–286.

Lee, T. W., Ko, I. S., & Lee, K. J. (2006). Health promotion behaviors and quality of life among community-dwelling elderly in Korea: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(3), 293–300.

Zhang, J. P., Huang, H. S., Ye, M., & Zeng, H. (2008). Factors influencing the subjective well being (SWB) in a sample of older adults in an economically depressed area of China. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 46(3), 335–347.

Paskulin, L., Vianna, L., & Molzahn, A. E. (2009). Factors associated with quality of life of Brazilian older adults. International Nursing Review, 56(1), 109–115.

Jia, S. M., Feng, Z. Y., Hu, Y., & Wang, J. Q. (2004). Survey of the living quality and its effect factors for the aged people in urban community of Shanghai city. Journal of Nurses Training, 19(5), 420–423.

Zhou, B., Chen, K., Wang, J. F., Wang, H., Zhang, S. S., & Zheng, W. J. (2011). Quality of life and related factors in the older rural and urban Chinese populations in Zhejiang Province. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30(2), 199–225.

Cai, T. J. (2004). Self-rated life satisfaction and its determinants among Chinese elderly females living alone. Chinese Journal of Population Science, S1, 70–74.

Deng, J. L., Hu, J. M., Wu, W. L., Dong, B. R., & Wu, H. M. (2010). Subjective well-being, social support, and age-related functioning among the very old in China. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(7), 697–703.

Huang, J. Q., Chen, Q. E., & Shu, X. F. (2005). A study on the relationship between quality of life and social support of elder in community. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medicine Science, 14(8), 725–726.

Xiao, S. Y. (1994). The theoretical basis and applications of Social Support Rate Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 4(2), 98–100.

Fratiglioni, L., Wang, H. X., Ericsson, K., Maytan, M., & Winblad, B. (2000). Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: A community-based longitudinal study. The Lancet, 355(9212), 1315–1319.

Lauder, W., Sharkey, S., & Mummery, K. (2004). A community survey of loneliness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46(1), 88–94.

Victor, C., Scambler, S., Bond, J., & Bowling, A. (2000). Being alone in later life: Loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 10(4), 407–417.

Ruggeri, M., Nose, M., Bonetto, C., Cristofalo, D., Lasalvia, A., Salvi, G., et al. (2005). Changes and predictors of change in objective and subjective quality of life: Multiwave follow-up study in community psychiatric practice. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 121–130.

Joseph, C., & Nichols, S. (2007). Patient satisfaction and quality of life among persons attending chronic disease clinics in South Trinidad, West Indies. The West Indian Medical Journal, 56(2), 108–114.

Brett, C. E., Gow, A. J., Corley, J., Pattie, A., Starr, J. M., & Deary, I. J. (2012). Psychosocial factors and health as determinants of quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Quality of Life Research, 21(3), 505–516.

Chachamovich, E., Fleck, M., Laidlaw, K., & Power, M. (2008). Impact of major depression and subsyndromal symptoms on quality of life and attitudes towards aging in an international sample of older adults. The Gerontologist, 48(5), 593–602.

Chou, K. L., & Chi, I. (1999). Determinants of life satisfaction in Hong Kong Chinese elderly: A longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 3(4), 328–335.

Chen, Y., Hicks, A., & While, A. E. (2012). Depression and related factors in older people in China: A systematic review. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 22(1), 52–67.

Ning, H. D., Luo, C. S., Zhang, Q. X., Zhu, Y. H., Wu, S. Y., Liang, H. Y., et al. (1999). An epidemiological study on quality of life among elderly population in Shenzhen. Chinese Journal of Prevention and Control of Chronic Non-communicable Diseases, 7(4), 1–5.

Qian, Z. C., & Zhou, M. (2004). Social support and quality of life: China’s oldest-old. http://paa2005.princeton.edu/papers/51243. Accessed September 13, 2012.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Yan Hu and Professor Hai-ou Xia for their translation of the OPQOL and Mr. Peter Milligan for his advice on statistical analysis. We thank data collectors for their assistance in data collection and the older people for their participating in this study. The authors would also like to thank China Scholarship Council, King’s College London and Fudan University for their financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Hicks, A. & While, A.E. Quality of life and related factors: a questionnaire survey of older people living alone in Mainland China. Qual Life Res 23, 1593–1602 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0587-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0587-2