Abstract

Becoming an entrepreneurial university has been identified as the solution to the problems facing contemporary higher education systems. The idea of becoming an entrepreneurial university can be seen as the result of a more globalised higher education sector where the domestic and institution-specific characteristics of universities are downplayed in favour of a more uniform idea of what a university should do and how it should be organized. This article contributes to this scholarly discussion by analysing how efforts to transform universities into “more complete organisations” are understood and interpreted in terms of organisational structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The European higher education (HE) landscape has experienced dramatic changes in the last couple of decades as a result of numerous reforms within the sector (Maassen 2009; Vukasovic et al. 2012). These reforms have taken place in the context of a perceived crisis in European higher education, where arguments related to decreased quality, lack of efficiency and poor relevance are heard frequently (Maassen and Olsen 2007). Becoming an entrepreneurial university has been identified as the solution to these perceived problems (Clark 1998). However, the idea of becoming an entrepreneurial university is not just a European response, but can be seen as the result of a more globalised higher education sector where the domestic and institution-specific characteristics of universities are downplayed in favour of a more uniform idea of what a university should do and how it should be organised (Mohrman et al. 2008). How specific this idea really is, is still open to question. In the same way that globalisation may mean many things to many people (Farazmand 1999, p. 511), the idea of the entrepreneurial university also encompasses several functions, such as fostering economic development (Pinheiro et al. 2012); leveraging interdisciplinary collaborations and innovation (Gibbons et al. 1994); addressing the needs of various stakeholders (Jongbloed et al. 2008) and improving efficiency and transparency (Stensaker and Harvey 2011). However some have argued that the current changes represent a fundamental shift from universities being loosely-coupled systems (Birnbaum 1988) into them being strategic organisational actors (Krücken and Meier 2006; Whitley 2008). This article contributes to this scholarly discussion by analysing how efforts to transform universities into “more complete organisations” are understood and interpreted in terms of organisational structures. This is an important aspect to investigate, firstly as it has the potential to shed light on both whether and how global ideas concerning university organisation are being translated into practice (Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón 2005). Secondly, because it can indicate to what extent one of the most stable public organisations in history, the university (Rothblatt and Wittrock 1993), is embarking on fundamental internal transformation. However, our point-of-departure is based on an understanding of change and continuity as being in a dialectical relationship (Farazmand 1999, p. 510) where global scripts and ideas are exposed to local translations (Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón 2005).

In this paper, these issues are explored by investigating the structural features of a major Nordic (Danish) university. From a macro (system-level) perspective, Denmark is a highly interesting case since few European, let alone Nordic, university systems have undergone such abrupt changes in the last decade. Further, the Danish system can be said to be especially exposed to dominant global ideas concerning university organisation, partly due to the policy emphasis put on globalisation. The chosen case, Aarhus University (AU), has radically pursued an internal reform agenda as a means of coping with the new dynamics brought about by shifting (operational and regulative) conditions, both domestically and internationally (Aagaard 2011). The article is structured around five main sections. Following the introduction, “Danish Higher Education Reforms: The Search for Strong Universities” briefly presents recent changes in the national HE landscape. This is followed by a conceptual section reviewing major thrusts from organisational science and higher education literatures, with a privileged focus on design-related dimensions and organisational archetypes. Section “Strategic Transformation at Aarhus University” presents the major empirical findings and “Discussion” discusses them in light of the literature. The paper concludes by summarising the main findings and their implications for our current understanding of change processes across public organisations like universities.

Danish Higher Education Reforms: The Search for Strong Universities

The Danish HE system has undergone a string of far reaching changes in the latest decade, all with the intention that the public universities should be strengthened as organisations. This section provides a short summary of the main elements of reform.

The current wave of reforms began at the end of 2001 when a national Research Commission proposed a number of bold changes targeting: (i) the funding system; (ii) the institutional landscape and (iii) the internal management of universities. One major policy objective was to increase the effectiveness and relevance of national research efforts. When a new Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation assumed overall responsibility for research and innovation in 2001, these proposals became the cornerstones of the policy-development process. The first two important steps by the new Ministry were to initiate reforms of the research council system and of the existing University Act. In 2003, reforms of the research funding system, aimed at ensuring an optimal use of public resources, took effect. The reform was an attempt to simplify the organisational structure of the research sub-system and strengthen its overall management and coordination. As a result, the research funding system was split into two subsystems: a council for independent research and a council for strategic research. A number of new strategic-funding councils were also established alongside the traditional research councils. This resulted in a number of shifts: from core funding to funding based on competition; from basic research to strategic research and from smaller to larger grants (Aagard and Mejlgaard 2012).

University governance systems were also exposed to dramatic changes. The 2003 University Act introduced central Boards composed of an external majority as the superior authority of universities and prescribed appointed rather than elected leaders. The ultimate objective was to sharpen-up the profiles of individual institutions and to increase collaboration between the various actors composing the research and innovation sub-systems. An illustration of the new policy-logic (Maassen and Stensaker 2011) lies in the expectation that universities would in future devise clear goals and strategies for fostering cooperation with industry. Knowledge exchange, technology transfer and staff mobility were explicitly added to the mission of universities, alongside the traditional tasks of education and research. Further, the new Act emphasised that universities’ central leadership structures ought to make strategic selections across research and educational areas and give these high priority in the years to come. As the next major policy step, in 2005 a Danish Globalisation Council was set-up. With broad representation from different sections of society, its main function was to advise the government on a national strategy in the light of global events and the rise of the knowledge economy. A rather comprehensive globalisation strategy was launched in the spring of 2006. It contains 350 specific initiatives which together entail further extensive reforms of education and research programmes and substantial changes in the framework conditions for growth and innovation in all areas of society, including entrepreneurship and innovation policy. “Strong universities” were seen as a key measure or benchmark in realising the ambitious goals.

In the realm of HE, the most dramatic outcome of the globalisation strategy was a reduction, through mergers, in the number of universities from 12 to 8 (from January 2007). Additionally, 12 (out of 15) public sector research institutes were integrated across the remaining public universities. As is often the case, the merger process produced winners and losers. Copenhagen University, the Technical University of Denmark and Aarhus University in particular gained from the mergers, in terms of increased size and influence. Together they now account for about two thirds of all Danish public research. In the eyes of the Ministry, the new, larger “super-universities” will not only be more competitive when applying for external (mostly EU) funds, but will also facilitate the recruitment and retention of international scientific talent. The Ministry foresaw that the “modernised” universities would be able to respond more efficiently to external demands, by developing new educational offerings and forming stronger relationships with industry. However how these new (large) universities should be internally organised was entirely left to the institutions themselves.

Old and New Organisational Archetypes in Higher Education

The Importance of Organisational Structures in Universities

Universities, in Europe and elsewhere, have traditionally been conceived as loosely-coupled organisations (Birnbaum 1988), with authority delegated to the bottom of the organisation (Clark 1983). However, within universities, organisational structures have been found to play an important role as an expression of various disciplines and academic areas and the ways in which they are socially linked to one another (Ben-David 1992). As underlined by Becher and Trowler (2001), academic tribes and territories are often manifested in various forms of organisational structure: departments, research centres, faculties, schools, etc. A university can, as a consequence, be seen as an “organisational umbrella” for various forms of disciplinary activity. A classic conception of how such activities can be coherently organised—the research university—is often seen as one of the key organisational forms in higher education (Martin 2012). In the research university: work integration is quite loosely-coupled between different organisational structures (departments, faculties); the internal governance of the university is based on collegiality, although with frequent power struggles for resources and influence; the norms and values are often focused on academic freedom and power and influence is largely rooted in disciplinary knowledge and expertise (Clark 1983; Ben-David 1992; Pinheiro 2012b). In general, the values and norms of this type of university are closely linked to the conception of HE as a public good (Slaughter and Rhoades 2004).

Organisational Archetypes as Powerful Global Ideas

The concept of the research university fits well with what Greenwood and Hinings (1993, p. 1052) call ‘organisational archetype’. Organisational archetypes are defined by organisational structures and management systems that are described in a holistic way, consisting of a mix of ideas, beliefs and values making up a distinct interpretive scheme (Greenwood and Hinings 1988). Scholarly interest in archetypes is linked to the need for understanding organisational diversity through the use of typologies. Yet organisational archetypes have also been found to play a central role (e.g. within neo-institutional theory) as examples of powerful global scripts, templates and schemas that may trigger conformity amongst organisations within a specific organisational field (Scott 2008a). While early versions of neo-institutional theory emphasised how organisations respond to external pressures through ceremonial conformity, by de-coupling structure from action (Powell and DiMaggio 1991), later versions have recognised that such de-coupling may collapse and that structures and actions may become more closely linked over time (Scott 2008b, p. 432). Hence, organisational archetypes can potentially be a powerful driver of organisational change. Across the organisational field of HE, the archetype of the ‘research university’ has been empirically found to be the most successful (and legitimating) organisational idea on a global scale (Beerkens 2010; Mohrman et al. 2008; Martin 2012; Pinheiro 2012b; Pinheiro et al. 2012).

The Rise of the Entrepreneurial University as a New Organisational Archetype

In the last decade the archetype of the research university has been challenged by the emergence of another powerful global idea, that of the entrepreneurial university (Clark 1998; Etzkowitz et al. 2008; Pinheiro 2012a). As an organisational archetype, the entrepreneurial university is characterised by the adoption of new structural arrangements aimed at enhancing internal collaborations (coupling) and fostering external partnerships (bridging). Its distinctive features include: a diversified funding base and the reallocation of resources around strategic areas; a strengthened central steering core (formal leadership structures); a focus on inter- and multi-disciplinary collaborations across teaching and research; technology transfers and collaborative partnerships along an extended developmental periphery and changes in governance structures like the inclusion of external parties on university boards (Clark 1998; Pinheiro 2012a). In this respect, the entrepreneurial archetype represents a considerable departure from the traditional ways in which university structures and activities were organised (see Table 1).

Most importantly, it can be argued that the rise of entrepreneurialism in HE (Clark 1998) is part and parcel of a much larger process encompassing the (global) diffusion of neo-liberal ideas (efficiency, effectiveness, competitiveness, etc.) that have been at the forefront of public sector reforms in recent years (Farazmand 1999; Christensen and Lægreid 2011) and are manifested in the adoption of market-type instruments and shifting behavioural postures within universities (c.f. Salminen 2003). It has been suggested that a possible implication of the adoption of this model is a fundamental shift in the values and norms of HE, where the public good dimension is downplayed in favour of the ‘logic of the marketplace’ and its negative effects on the inner life and social function of universities (Slaughter and Rhoades 2004)

The Relationship Between Organisational Archetypes and Organisational Structures in a Broad Institutional Perspective

While our notion of university archetypes is closely linked to institutional perspectives concerned with how scripts, ideas and models are diffused globally, it is important to underline that our analysis is based on a broader understanding of institutional theory. Farazmand (2002, p. 67–71) differentiates between a narrow and a broad-based stream of institutional theory. In the first stream organisations are mainly seen as passive recipients of external ideas within a defined organisational field where there is little or no effect from organisational actions such as strategies and planning. Within the broad-based stream of institutional research, organisations are seen as more active players within the field in which they are located, allowing them to “absorb pressures by learning from the external living eco-systems in which they operate” (Farazmand 2002, p. 73). This distinction is important since the archetypes of both the research university and the entrepreneurial university can be considered as dominant and powerful global ideas on how universities should be organised, while the archetypes themselves provide quite limited information on how organisational structures should be designed to match the goals and ambitions related to each archetype. In principle, this may open up various organisational responses. The implication is that specific organisational structures can be designed by the individual university or borrowed from what may be perceived as key role-models within the organisational field (Scott 2008a).

In line with the broad-based institutional perspective, scholars have suggested that, as a process, the adoption and subsequent diffusion (institutionalisation) of specific structural designs within organisations is permeated by the attribution of meanings and coherence through translation processes (Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón 2005). Consequently, organisational structures are often thought to enhance organisational legitimacy in the eyes of external constituencies like government or industry (Drori and Honig 2013), foster access to scarce resources (Pfeffer and Salancik 2003) and contribute to a positive market image (Leihy and Salazar 2012). Organisational structures might also facilitate value creation in the form of external partnerships (Morris and Snell 2007). Hence, organisational structures should be conceived as far more than simple neutral instruments as they “embody-wittingly or otherwise-intentions, aspirations, and purposes” (Greenwood and Hinings 1993, p.1055). Following Scott’s (2008b) assertion that, as a process, the reorganisation of university structures may have significant effects on issues concerning values, norms and power within organisations, it is also of interest to identify potential winners and losers.

For example, the rise of enterprising (market-based) models across the public sector (Christensen and Lægreid 2011), with the aim of aiding its modernisation, is intrinsically linked with the ‘logic of the marketplace’ (Slaughter and Rhoades 2004; Farazmand 1999) and the (neo-liberal) normative belief regarding the positive effects emanating from: competition; a focus on efficiency/effectiveness; rationalisation; strategic planning etc. In other words, whilst assessing structural changes at the meso/micro levels (agency), one needs to take into account the wider institutional conditions (structure) underpinning such internal change processes (see Hay and Wincott 1998). Given our interest in studying how efforts related to transforming universities into more strategic organisational actors are understood and interpreted in terms of organisational structures, a key issue to investigate is how the establishment of certain organisational structures are legitimised and argued for and whether specific arguments outweigh others when designing new structural arrangements. In our analysis, a privileged focus is given to three sets of arguments cutting across the organisational dimensions featured in Table 1, namely: the importance of: (i) core functions and mission(s); (ii) formal roles and responsibilities and (iii) access to and allocation of resources. The rationale for selecting these is twofold. First, these features rank prominently in current academic debates around university management and transformation (Vorley and Nelles 2012; Frølich 2005; Salminen 2003). Second, the selected features are intrinsically related to central elements of organisational archetypes (Greenwood and Hinings 1993, p. 1054). Before we tackle each of these arguments, we provide a brief overview of the change dynamics across the case university.

Strategic Transformation at Aarhus University

Drivers and Internal Development Process

Prior to 2005, Arhus University (AU) was a typical or traditional public multi-faculty university where, amongst other aspects, leaders were elected. However, starting in the autumn of 2005, a new system based on appointed leaders at all levels of the organisation and a university board with a majority of external members were instituted. Such changes were part of a much larger reorganisation effort, which was a strategic response to a number of challenges, internal and external, facing the university. On the external front, these included: increasing domestic and international competition for research funds and in attracting the most talented researchers and students; a strengthened focus on (strategic) research; the need for a better understanding of the university’s societal role, both regionally and nationally and the external expectations regarding the role of (Danish) universities in tackling global challenges such as climate change, migration, etc. Internal challenges included: efficiency demands, breaking down departmental “silos” to foster multidisciplinary collaboration and partnerships with societal actors across public and private sectors and creating a greater scope for strategic leadership.

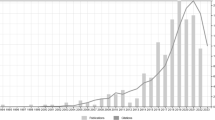

The merger process was initiated in 2006 when two small universities and two large government-run research institutes were integrated into the “old” AU (Fig. 1). This resulted in a 40 % rise in annual turnover (826 million Euros in 2012) and an increase from five to nine main academic areas. Additionally, the merger created a rather large, diverse and geographically spread-out university. In fact size, i.e. the ability to compete both nationally and internationally, appears to have been the single most determining factor driving the strategic actions of AU’s central administration.

Although the post-merger situation called for further internal reorganisation, no major structural changes were implemented for the first couple of years. This was primarily due to the merger agreements, in which the units involved were allowed to continue to run independently for a limited period of time. The first step towards actual structural integration was initiated in 2008, when the university adopted a new 5-year strategy. This defined the university’s four core functions (see below). It has since been supplemented by a range of specific strategies across key areas like internationalisation and talent development, in addition to a vision plan (up to 2028) for its physical infrastructure. The new strategy underlined the need for sweeping academic reorganisation. According to the central administration, the mergers created the ideal conditions for realising a range of synergies across the university’s core activities, including significant potential for interdisciplinary collaborations.

Following the adoption of the new strategic plan, the central administration, via the Rector, initiated the so-called academic development process in the spring of 2010, with the adoption of a new vision statement: “to belong to the elite of universities and to contribute to the development of national and global welfare.” (AU 2008, p.4) A few months later, the University Board decided to organise all internal research and teaching activities around four main academic areas and the overall framework for the continuation of the merger/integration process was then determined. Following this, each new main academic area carried out an analysis of academic structures and requirements related to the internal organisation, including desirable departmental structures. At the same time, a detailed analysis of the university’s existing administrative structures and requirements was carried out, in order to determine how best to organise administrative functions. The main goals of this far reaching reorganisation effort were: to further improve quality, impact and international reach; to strengthen performance in terms of academic and financial results; to complete the merger process, i.e. to create one unified university; to tear down internal boundaries and stimulate collaboration across disciplines and to ensure a more professional and efficient administration.

The final major decision about the reorganisation process was taken by the University Board in the spring of 2011, with the implementation process running until the end of 2012. The adopted solution was a new organisational structure composed of fewer core academic units (faculties and departments) and a simpler administrative structure. By establishing one “unified university”, the strategic aim was to reduce internal barriers to collaboration by greatly reducing the number of sub-units (Hatakenaka and Thompson 2010, p. 45). Following the original merger in 2006, AU consisted of nine independent faculties and schools representing a total of 55 institutes. By the autumn of 2011 this had been reduced to four faculties (Fig. 2 and 3) encompassing a total of 27 departments. As a result, today academically-related departments are to a large degree located geographically close to each other, in the form of coherent academic environments cutting across the main academic (focus) areas.

Core Functions and Mission(s)

AU’s internal values are based on the ethical ideals of freedom and independence described in the Magna Charta of the European Universities (AU 2008, p. 4). The university’s mission is: “to develop knowledge, welfare and culture through research and research-based education, knowledge dissemination and external advice.” (ibid.) In other words, the ambition is to combine mass (training) with elite (research) functions while engaging with, and remaining relevant to, society and various external stakeholders. In addition to the traditional university functions of teaching and research (Clark 1983), AU’s board decided to include ‘knowledge exchange’ and ‘talent development’ as core activities. The former pertains to the increasing importance attributed to societal engagement and the direct role of universities in economic development and innovation (c.f. Pinheiro et al. 2012), i.e. what some have considered to be the key feature of the “second academic revolution”, namely the rise of entrepreneurial science (Etzkowitz and Webster 1998). This extended mission is legitimatised on the basis of the university’s contribution to social progress and development.

“The University of Aarhus provides independent and inspiring knowledge as a basis for the development of society […] It is essential for progress in society that the entire knowledge base developed at the university be made available and that the research carried out at the university can function as a gateway to the global knowledge market.” (AU 2008, p. 16)

As a core function, ‘talent development’ is intrinsically linked with the need to internally develop and externally attract the best scientific talents and to realise the strategic ambition of becoming a ‘world class’ player in the increasingly globalised field of higher education (Kehm and Stensaker 2009) by combining research in novel ways and developing a distinct scientific profile.

“The University of Aarhus belongs to the international elite […] The university wishes to combine research in new ways—with new subject areas and across traditional subject borders—in greater depth and in new and unknown fields.” (AU 2008, p. 12)

According to the central administration or central steering core (Clark 1998), the focus on these four core functions is a natural progression of the early conception of the university as a core component of a “triple-helix” of university-government and industry relations (Etzkowitz and Webster 1998), naturally resulting in what is termed a novel conceptualisation of the modern university in the form of a ‘quadruple helix’ (Fig. 2).

Formal Roles and Responsibilities

Turning now to role specification (power reallocation), at the level of the central administration the reorganisation led to a change from ten management units to a much smaller, unified senior leadership team with cross-cutting responsibility for strategic management and quality assurance across the board. This rather powerful group of individuals consists of the Rector, the Pro-Rector, the University Director and the Dean of each of the four faculties. The latter have now a dual role. Not only are they responsible for the academic and financial management of their respective units, but on behalf of the senior management group they also head the university’s four core functions. The Rector is responsible for the daily management of the university within the framework set out by the University Board. The other members of the senior management group perform their duties and responsibilities in light of the authority given to them by the Rector. In its work, the senior management group is supported by three specialised units: the senior management group secretariat; the management secretariat and the press office. In order to ensure academic checks and balances, academic councils and internal forums responsible for each of the four academic areas have also been established. The legitimising basis of the changes in the formal roles and responsibilities are well reflected in the strategic plan, addressing both internal and external audiences and stressing aspects such as efficiency and cohesiveness.

“Professional and coherent management is a prerequisite for the effective running of a large university. […] This is why the university is establishing a new, effective and cohesive management body that is able to handle the larger and broader portfolio of tasks that the University of Aarhus will be facing in the future.” (AU 2008, p. 22; emphasis added)

Access to, and Reallocation of, Resources

In addition to the significant reduction in the number of internal units, the reorganisation efforts described above led to changes in the internal allocation of funds. In 2010, AU’s Board established a strategic financial management fund worth DKK 1,150 million (2011–2016), the equivalent of 3 % of the university’s annual turnover. Its core aim is to support long-term strategic endeavours across the core academic areas and to launch new strategic initiatives. In the realm of research, a number of interdisciplinary research centres (global change and development, entrepreneurship and innovation etc.) involving different academic fields and traditions are currently being established. The aim, according to the central administration, is to create new and groundbreaking scientific results capable of enhancing AU’s scientific profile on the one hand and its relative position in global research rankingsFootnote 1 on the other. Figure 4 below shows the resource allocations (relative amounts) per academic function in 2011.

As far as income is concerned about 60 % of funds are allocated directly from central government, of which 34 % are for research activities; 28 % comes from external competitive research funds and 13 % from other sources (consulting and/or developmental services), including 9 % from government contracts (Holm-Nielsen 2012). As a result of the merger, and the subsequent increase in size, the new AU has become a major domestic player, responsible for 27 % of total research performed across the Danish public-sector. In order to leverage its financial independence, the university has in place a research foundation, composed of various limited (holding) companies; real-estate investments and a science-park. Finally, according to an external (“independent”) consultancy report providing the central administration with the legitimising basis for undertaking the sweeping reorganisation (including instilling a spirit of enterprise):

“When basic research ideas are developed in such [tight links between basic and applied research efforts] a strategic context, researchers may well find that there are broader options for funding—including strategic grants or industry sponsorship […] it is vital that the mechanisms for funding inside the University should actively encourage staff to look forward to innovative and creative ways of doing things.” (Hatakenaka and Thompson 2010, p. 21, 80)

Discussion

Strategic Actor-Hood and Archetypes

Similarly to what is happening elsewhere across the Nordic region (Aarrevaara et al. 2009), the 2003 University Act accorded the university the special status of an independent institution under the auspices of public administration. It is stressed that the “freedom and independence of the university are crucial prerequisites for it to be able to meet its obligations to society.” (AU 2008, p.3) Recent developments have been marked by a much stronger ‘top-down’ orientation (Salminen 2003), with fewer people involved in key strategic decisions. This shift in governance modus is reflected in the newly adopted organisational structure culminating in a strengthened central steering core (Clark 1998). Having said that, as means of properly managing internal and external legitimacy (Drori and Honig 2013) the process is being balanced by embracing traditional academic norms and values around freedom and independence, inter alia, by referring to the ethical ideas described in the Magna Charta of the European Universities (AU 2008, p.4).

The newly adopted internal governance model stresses the importance of academic checks and balances. In concrete (structural) terms, this has resulted in the inclusion of an academic council for each faculty and a total of four academic forums, one for each core activity. Across the academic heartland (Clark 1998), the new organisational structure includes academic forums at the sub-unit (departmental) level as well. Accountability (Stensaker and Harvey 2011) and legitimacy (Drori and Honig 2013) concerns have resulted in strategic attention being paid to the inclusion of external parties in internal governance structures, in the form of advisory-boards and committees as well as employer panels.

Following on the premises outlined earlier, around the transformation of universities into more coherent strategic actors (Whitley 2008; Krücken and Meier 2006), the data reveal that efforts are well underway to adopt (de-institutionalisation) existing structural arrangements and concurrently adapt (re-institutionalisation) a new organisational structure better suited to the disruptive changes, perceived and real, emanating from the outside (c.f. Beerkens 2010). A number of key aspects stand out in this new strategic posture and its respective structural (design-related) adjustments.

First, the attention paid to professional management (Gornitzka and Larsen 2004) and rationalisation (Ramirez 2010), aligned with the prevalence of ‘New Public Management’ in the organisational field of HE (Salminen 2003), and aimed at making AU a leaner, more effective and efficient organisation capable of responding to an increasingly complex and volatile environment. This mirrors ongoing efforts to create unitary, coherent and predictable organisational entities by universities’ central steering cores across Europe (Krücken and Meier 2006; Whitley 2008), substantiated, inter alia, around a distinct institutional profile and organisational identity (c.f. Fumasoli et al. 2012). Second, the data suggests the importance attributed to intra- and inter-organisational collaborations and partnerships such as new interdisciplinary units and formal agreements with external stakeholders across the public and private sectors (Pinheiro 2012c; Jongbloed et al. 2008). Third, the strategic importance attributed to financial autonomy and the need to tap into new funding streams aimed at gradually reducing reliance on the public purse (Clark 1998).

All of these aspects are intrinsically linked with the relational archetype (Morris and Snell 2007) of the ‘entrepreneurial university’ sketched out earlier. The legitimacy of this pervasive global model (Mohrman et al. 2008) lies in its apparent ability to improve internal efficiency (e.g. with respect to operations and teaching activities) while, simultaneously, promoting research capacity (excellence) and external partnerships (relevance) across the board (Pinheiro 2012a; Vorley and Nelles 2012; Clark 1998). Yet in many respects these features are not unique to AU as an organisation (c.f. Pinheiro 2012b). What makes this case so uniquely compelling, at least within the Northern European HE context, pertains to the adoption of a matrix-type organisational model. At the heart of this lies the willingness to foster a tighter coupling (integration) across core functions, types of activities and sub-units. The paradox, given the search for a stronger organisational actor-hood (Ramirez 2010), is that at the same time the matrix structure sacrifices unity of command (Mintzberg 1979). The matrix can be interpreted here as a strategic archetype (Greenwood and Hinings 1993) used by AU’s central steering core in an attempt to deal with the challenges—functional, institutional, cultural etc.—posed by shifting environmental conditions which together have led to the need to create a much larger, “stronger” university.

Assessing the Relevance of the Matrix Organisation as an University Archetype

Matrix structures or cross-functional organisations are thought to be ideal: (i) whilst attempting to combine functional and project-related tasks (Galbraith 1971); (ii) when organisations possess multiple-priority strategies (Ford and Randolph 1992) and (iii) in those circumstances where management is keen to foster the sharing of specialised (and costly) resources (Galbraith 2008). The model is widespread across the business (for-profit) world, but there have been attempts to introduce it within the public sector as well (Rowlinson 2001). As alluded to earlier, this is part and parcel of a far reaching process, initiated in the 1980s, of modernising public administration (Christensen and Lægreid 2011). Preliminary studies suggest that, despite implementation bottlenecks, the matrix has been found to improve the performance of public organisations (Kuprenas 2003; Brignall and Modell 2000). There are, however, a number of preconditions if synergies are to be realised as originally (rationally) planned by management.

“The numerous interfaces inherent in a matrix structure require strong communication skills and an ability to work in teams, while the dual authority of a matrix requires people who are adaptive and comfortable with ambiguity in order to prevent negative influences to motivation and job satisfaction.” (Kuprenas 2003, p.59; emphasis added)

The few existing studies shedding light on the implementation of matrix structures within universities pertain to the commercialisation of academic knowledge. In North America, Bercovitz et al. (2001) found the link between the adoption of specific organisational structures around the technology transfer function and performance to be predictable in the light of theory. The matrix-model was found to be positively correlated with coordination capabilities and leveraging the critical trade-off between different revenue streams. Studies from Europe illustrate how the introduction of a de facto interdisciplinary matrix, in the form of a dedicated research division supporting commercialisation, not only facilitates work integration (coupling) amongst scholars belonging to different disciplinary traditions and sub-units, but, most importantly, it enables the successful achievement of multiple university functions and ambitions (Debackere 2000). Notwithstanding this, the above studies also highlight that the positive correlation between structure and performance is to a large degree a function of path-dependencies, with the adopted matrix-type structures reflecting historical trajectories and institutional legacies and traditions (see Krücken 2003; Pinheiro 2012b). The inclusion of consultative, ‘bottom-up’ structures such as academic forums are an example of the importance attributed to the deeply institutionalised traditions of collegiality (Tapper and Palfreyman 2011) and democracy (de Boer and Stensaker 2007) within universities.

Is that it then? Can we simply conclude that the adoption of a matrix structure and its subsequent alignment with strategic considerations and endogenous factors like path dependencies, culture, etc. is the panacea for the problems facing modern (European) universities? In our view, and in theory, the matrix structure does indeed have the potential to solve some critical problems, but its adoption (and full institutionalisation) raises some additional dilemmas. A key issue is how to find a balance between work-integration, linkages and coupling while at the same time maintaining organisational control and coherence. To facilitate this balance, we argue, the role of individuals or agents in academic structures comes to the fore (Clark 1983), as advocated by proponents of micro-institutionalism (Powell and Colyvas 2008).

According to Galbraith (1971, 1973, 2008), the effective functioning of lateral structures, a core component of the matrix-design, relies on individuals (“functional managers”) who act as integrators, facilitating coordination across units. Studies of the entrepreneurial behaviour of universities, in Europe and beyond, have shed light on the importance attributed to the active support of the academic heartland (Clark 1998; Pinheiro 2012b). Similarly, academic efforts geared towards stronger collaborations with external parties like industry were found to be intrinsically dependent on the pro-active initiatives of certain individuals—academic entrepreneurs—at the sub-unit level (Bercovitz and Feldman 2008; Pinheiro 2012c). AU’s matrix model is unambiguous as regards the role attributed to formal leaders (academic managers) both at the central and unit levels. What is less clear however is what role, if any, individual academics are to play in terms of acting as boundary spanners (Aldrich and Herker 1977) from both intra- (dismantling internal silos) and inter- (building bridges with the outside) organisational perspectives.

Earlier studies focusing on the performance effects of matrix-structures suggest that greater clarity of managers’ roles, whilst important from a technical performance viewpoint, was found to have little impact on either administrative control or efficiency (Sbragia 1984). Within universities, stronger administrative control over academic activities has been shown to be correlated with an increase in ‘academic bureaucratisation’ (Gornitzka et al. 1998), with the potential for negative effects on core tasks. Similarly, studies by Musselin (2007) suggest that formal structures and procedures, even when numerous, seldom contribute to increasing academic cooperation and coordination and only weakly support hierarchical power.

Advocates of the matrix structure contend that it is the ideal design for implementing cross-disciplinary projects. However earlier studies revealed that, due to their dualistic nature, matrices tend to generate conflicts between project- and disciplinary-based groups (Joyce 1986). It is widely acknowledged in the literature that, in excess, conflict can reduce organisational performance (c.f. De Dreu et al. 1999). Traditional academic structures focusing on collegiality (Tapper and Palfreyman 2011) and democracy (de Boer and Stensaker 2007) have, for the most part, been able to cope with conflicts arising from the prevalence of multiple goals, functions, aspirations and sub-cultures within universities (Clark 1983; Kerr 2001). Disciplinary postures and traditions (Becher and Trowler 2001) and academic values (Welch 2005) are deeply entrenched, implying that university managers need to take contextual dimensions seriously. Policies and projects aimed at stimulating certain functions like ‘talent development’ and/or ‘knowledge exchange’ run the risk of being counterproductive if/when inadequate attention is paid to knowledge dimensions (Clark 1983) and the ‘inner life’—postures, preferences, traditions etc.—of sub-units and academic groups across the academic heartland (Clark 1998; Schwartzman 2008).

Matrix structures are thought to facilitate the difficult balance between differentiation and integration (Galbraith 1973, 2008). Fiercer competition has, inter alia, meant that universities are increasingly pressurised to develop distinct institutional/market profiles (Kehm and Stensaker 2009). Within universities ‘loose-coupling’ has been found to be advantageous in situations where environments are increasingly complex and volatile (Birnbaum 1988; Pinheiro 2012a) and when external signals are characterised by ambiguity and the coexistence of contradictory (policy/market/institutional) logics (Maassen and Stensaker 2011), since they foster a variety of responses at the organisational (central) and sub-unit levels (Greenwood et al. 2011; Pinheiro 2012b, c). Contractual arrangements (Gornitzka et al. 2004) and the rise of strategic science regimes (Rip 2004) across the Nordic countries are resulting in the central steering core of universities paying increasing attention to the centralisation of decision making procedures (Frølich 2005; Salminen 2003), in tandem with closer integration (tighter-coupling) between functions, sub-units, knowledge domains and stakeholder groups (Fumasoli et al. 2012; Pinheiro 2012b; Vorley and Nelles 2012). Given the focus put on task integration (coordination), proponents of matrix-type organisations across the organisational field of HE need to be careful not to disrupt existing path- and resource-dependent arrangements and structures likely to promote positive differentiation (scientific excellence, entrepreneurial behaviour etc.) across core tasks and sub-units (see Pinheiro 2012a; Schwartzman 2008).

Conclusion and Implications

The case presented here provides yet more empirical evidence of the profound changes sweeping across Europe’s HE system and its core organisational actors, public universities. As for AU, it is undeniable that the merger process brought to the fore a new “strategic impetus” (Rip 2004), with the central administration taking full advantage of this unique opportunity—using the archetype of the entrepreneurial university as an argument for initiating (and legitimating) a specific interpretation of the idea of the entrepreneurial university. In practical terms this was achieved by: restructuring the ways in which academic activities were traditionally organised and coordinated; redefining roles and responsibilities and reallocating resources. In principle, this implies a formal strengthening of the role of the central administration and in particular, the leadership within the university. While the implications are not yet empirically observable, one can imagine that this reorganisation increases the opportunities for stronger organisational and social control, with academics faced with stronger expectations regarding output (performance) and the number of tasks to pay attention to, with increasing insecurity as a likely result (Farazmand 1999, p. 517).

However, following Farazmand’s (1999, p. 510) claim that one should view globalisation as a dialectical relationship between change and continuity, the possible effects of the new university design are complex and may even be somewhat paradoxical. For example, the interpretation of how a more entrepreneurial university should look, structurally speaking, included picking many elements from a familiar form within organisational studies—the matrix structure. This is in part a result of the ambiguity associated with the entrepreneurial university as a blueprint or organisational template when it comes to the ways in which structural and functional arrangements ought to be addressed in real life situations. Equally important, the archetype of the entrepreneurial university is thought to address concerns with respect to external support for internal goals and aspirations (Drori and Honig 2013), for example by signaling the university’s willingness to reach-out to various external stakeholders and contribute to the development of society (Pinheiro et al. 2012). On the other hand, and at the level of the organisational field, internal legitimacy (Drori and Honig 2013) is assured by simultaneously adopting and adapting (Beerkens 2010) particular features associated with the widespread archetype of the research-intensive university, which might imply that dimensions associated with the public-good (Slaughter and Rhoades 2004) can be upheld.

Turning back briefly to the structural features associated with the matrix archetype, it is worth noting that these differ substantially from the ways in which traditional research universities have been (and still are) organised. Yet it is still an open question whether, as an archetype for organising internal activities, the matrix structure will indeed enable universities like AU to reach the goals and ambitions associated with the entrepreneurial archetype. At least two very different outcomes can be predicted. On the one hand, over time the new (matrix) design may ensure stronger organisational coherence as a result of the concentration of academic areas and the integration of functions via dual leadership structures (responsibilities). This development is, to a large extent, conditioned by how state instruments related to funding, accountability and institutional governance match the specific characteristics of the new organisational design (c.f. Maassen and Olsen 2007). On the other hand, the newly adopted (matrix) structure may also run the risk of being co-opted (Selznick 1966) by the inherent characteristics and deeply institutionalised aspects (e.g. collegiality, autonomy etc.) of the traditional research university. Since, as Galbraith (2008) demonstrates, matrix structures are aimed at cutting across various horizontal and vertical functional areas, the handling of multiple, conflicting goals (Kerr 2001) and institutional logics (Greenwood et al. 2011) may, paradoxically, result in a lower degree of functional integration, with the new (matrix) design ending-up mirroring the traditional loose-coupling research universities are known for (Pinheiro 2012b). The implication is not necessarily that universities will remain the same (inertia), since formal changes and the restructuring processes may indeed end up transforming internal cultures, social (trusty) relations and functional integration in ways not yet foreseen.

Notes

In 2012, AU ranked 86th globally, in the prestigious world university rankings prepared by Shanghai’s Jiao Tang university. Domestically, AU has consistently ranked number 2, after the University of Copenhagen, the country’s flagship institution.

References

Aagaard, K. (2011). Danish University mergers: the case of Aarhus University. Paper presented at the Hedda 10th anniversary conference. Oslo, 4th November.

Aagaard, K., & Mejlgaard, K. (Eds.) (2012). Dansk forskningspolitik efter årtusindskiftet. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Aarrevaara, T., Dobson, I., & Elander, C. (2009). Brave new world: higher education reform in Finland. Higher Education Management and Policy, 21(2), 2–18.

Aldrich, H., & Herker, D. (1977). Boundary spanning roles and organization structure. The Academy of Management Review, 2(2), 217–230.

AU (2008). Strategy 2008-2012: quality and diversity. Aarhus: University of Aarhus.

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Beerkens, E. (2010). Global models for the national research university: adoption and adaptation in Indonesia and Malaysia. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 8(3), 369–381.

Ben-David, J. (1992). Centers of learning. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publ.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrepreneurs: organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19(1), 69–89. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0295.

Bercovitz, J., Feldman, M., Feller, I., & Burton, R. (2001). Organizational structure as a determinant of academic patent and licensing behavior: an exploratory study of Duke, Johns Hopkins, and Pennsylvania State Universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1–2), 21–35. doi:10.1023/a:1007828026904.

Birnbaum, R. (1988). How colleges work: The cybernetics of academic organization and leadership. University of Michigan: Jossey-Bass.

Brignall, S., & Modell, S. (2000). An institutional perspective on performance measurement and management in the ‘new public sector’. Management Accounting Research, 11(3), 281–306. doi:10.1006/mare.2000.0136.

Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (Eds.) (2011). The Ashgate research companion to new public management. Surrey: Ashgate.

Clark, B. R. (1983). The higher education system: academic organization in cross-national perspective. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: organizational pathways of transformation. New York: Pergamon.

Czarniawska-Joerges, B., & Sevón, G. (2005). Global ideas: how ideas, objects and practices travel in a global economy. Copenhagen: Liber & Copenhagen Business School Press.

de Boer, H., & Stensaker, B. (2007). An internal representative system: the democratic vision. In P. Maassen, & J. P. Olsen (Eds.), University dynamics and European integration (Vol. 19, pp. 99–118, Higher Education Dynamics). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

De Dreu, C. K. W., Harinck, F., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (1999). Conflict and performance in groups and organizations. In C. Cooper & I. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 14, pp. 369–414). New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Debackere, K. (2000). Managing academic R&D as a business at K.U. Leuven: context, structure and process. R&D Management, 30(4), 323–328. doi:10.1111/1467-9310.00186.

Drori, I., & Honig, B. (2013). A process model of internal and external legitimacy. Organization Studies, 34(3), 345–376. doi:10.1177/0170840612467153.

Etzkowitz, H., & Webster, A. (1998). Entrepreneurial science: the second academic revolution. In E. Etzkowitz, A. Webster, & P. Healey (Eds.), Capitalizing knowledge: new intersections of industry and academia (pp. 21–46). Albany: SUNY Press.

Etzkowitz, H., Ranga, M., Benner, M., Guaranys, L., Maculan, A. M., & Kneller, R. (2008). Pathways to the entrepreneurial university: towards a global convergence. Science and Public Policy, 35(9), 681–695. doi:10.3152/030234208x389701.

Farazmand, A. (1999). Globalization and public administration. Public Administration Review, 59(6), 509–522.

Farazmand, A. (2002). Modern organizations: theory and practice. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

Ford, R. C., & Randolph, W. A. (1992). Cross-functional structures: a review and integration of matrix organization and project management. Journal of Management, 18(2), 267–294. doi:10.1177/014920639201800204.

Frølich, N. (2005). Implementation of new public management in Norwegian Universities. European Journal of Education, 40(2), 223–234. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3435.2005.00221.x.

Fumasoli, T., Pinheiro, R., Stensaker, B. (2012). Strategy and identity formation in Norwegian and Swiss universities. Paper presented at the CHER conference, September 10–12 Belgrade.

Galbraith, J. R. (1971). Matrix organization designs: how to combine functional and project forms. Business Horizons, 14(1), 29–40. doi:10.1016/0007-6813(71)90037-1.

Galbraith, J. R. (1973). Designing complex organizations. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Galbraith, J. R. (2008). Designing matrix organizations that actually work: how IBM, Proctor & Gamble and others design for success. San Francisco: Wiley.

Gibbons, M., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Gornitzka, Å., & Larsen, I. M. (2004). Towards professionalisation? Restructuring of administrative work force in universities. Higher Education, 47(4), 455–471. doi:10.1023/B:HIGH.0000020870.06667.f1.

Gornitzka, Å., Kyvik, S., & Larsen, I. M. (1998). The bureaucratisation of universities. Minerva, 36(1), 21–47. doi:10.1023/a:1004382403543.

Gornitzka, Å., Stensaker, B., Smeby, J.-C., & De Boer, H. (2004). Contract arrangements in the Nordic countries: solving the efficiency-effectiveness dilemma? Higher Education in Europe, 29, 87–101. doi:10.1080/03797720410001673319.

Greenwood, R., & Hinings, C. (1988). Organizational design types, tracks and the dynamics of strategic change. Organization Studies, 9(3), 293–316. doi:10.1177/017084068800900301.

Greenwood, R., & Hinings, C. (1993). Understanding strategic change: the contribution of archetypes. Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), 1052–1081.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371. doi:10.1080/19416520.2011.590299.

Hatakenaka, S., & Thompson, Q. (2010). Aarhus University: reform review: Final Report. Arhus.

Hay, C., & Wincott, D. (1998). Structure, agency and historical institutionalism. Political Studies, 46(5), 951–957.

Holm-Nielsen, L. B. (2012). Mergers in higher education: University reforms in Denmark–the case of Aarhus university. Presentation at the seminar “University Mergers: European Experiences”, Lisbon.

Jongbloed, B., Enders, J., & Salerno, C. (2008). Higher education and its communities: interconnections, interdependencies and a research agenda. Higher Education, 56(3), 303–324. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9128-2.

Joyce, W. F. (1986). Matrix organization: a social experiment. The Academy of Management Journal, 29(3), 536–561. doi:10.2307/256223.

Kehm, B. M., & Stensaker, B. (2009). University rankings, diversity, and the new landscape of higher education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Kerr, C. (2001). The uses of the university. Massachusets: Harvard University Press.

Krücken, G. (2003). Learning the ‘New, New Thing’: on the role of path dependency in university structures. Higher Education, 46(3), 315–339. doi:10.1023/a:1025344413682.

Krücken, G., & Meier, F. (2006). Turning the university into an organizational actor. In G. S. Drori, J. W. Meyer, & H. Hwang (Eds.), Globalization and organization: world society and organizational change (pp. 241–257). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuprenas, J. A. (2003). Implementation and performance of a matrix organization structure. International Journal of Project Management, 21(1), 51–62.

Leihy, P., & Salazar, J. (2012). Institutional, regional and market identity in Chilean public regional universities. In R. Pinheiro, P. Benneworth, & G. A. Jones (Eds.), Universities and regional development: a critical assessment of tensions and contradictions (pp. 141–160). Milton Park and New York: Routledge.

Maassen, P. (2009). The modernisation of European higher education. In A. Amaral, I. Bleiklie, C. Musselin (Eds.), From governance to identity (Vol. 24, pp. 95–112, Higher Education Dynamics). Springer Netherlands.

Maassen, P., & Olsen, J. P. (Eds.). (2007). University dynamics and European integration. Dordrecht: Springer.

Maassen, P., & Stensaker, B. (2011). The knowledge triangle, European higher education policy logics and policy implications. Higher Education, 61(6), 757–769. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9360-4.

Martin, B. R. (2012). Are universities and university research under threat? Towards an evolutionary model of university speciation. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(3), 543–565. doi:10.1093/cje/bes006.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations: a synthesis of the research. Harlow: Prentice-Hall.

Mohrman, K., Ma, W., & Baker, D. (2008). The research university in transition: the emerging global model. Higher Education Policy, 21(1), 5–27.

Morris, S. S., & Snell, S. A. (2007). Relational archetypes, organizational learning, and value creation: extending the human resource architecture. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 236–256. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.23464060.

Musselin, C. (2007). Are universities specific organisations? In G. Krücken, A. Kosmützky, & M. Torka (Eds.), Towards a multiversity? Universities between global trends and national traditions (pp. 63–84). Bielefeld: Transaction Publishers.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (2003). The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. Stanford, California: Stanford Business Books.

Pinheiro, R. (2012a). The future of the (entrepreneurial) university: Resolving or propelling the tensions between the regional and the global? Paper presented at CHER 2012 conference, Belgrade Sept. 10–12.

Pinheiro, R. (2012b). In the region, for the region? A comparative study of the institutionalisation of the regional mission of universities. Oslo: University of Oslo.

Pinheiro, R. (2012c). University ambiguity and institutionalization: a tale of three regions. In R. Pinheiro, P. Benneworth, & G. A. Jones (Eds.), Universities and regional development: A critical assessment of tensions and contradictions (pp. 35–55). Milton Park and New York: Routledge.

Pinheiro, R., Benneworth, P., & Jones, G. A. (Eds.). (2012). Universities and regional development: a critical assessment of tensions and contradictions. Milton Park and New York: Routledge.

Powell, W., & Colyvas, J. (2008). Microfoundations of institutional theory. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 276–298). London: Sage.

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ramirez, F. O. (2010). Accounting for excellence: transforming universities into organizational actors. In V. Rust, L. Portnoi, & S. Bagely (Eds.), Higher education, policy, and the global competition phenomenon (pp. 43–58). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Rip, A. (2004). Strategic research, post-modern universities and research training. Higher Education Policy, 17(2), 153–166.

Rothblatt, S., & Wittrock, B. (1993). The European and American university since 1800: historical and sociological essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rowlinson, S. (2001). Matrix organizational structure, culture and commitment: a Hong Kong public sector case study of change. Construction Management and Economics, 19(7), 669–673. doi:10.1080/01446190110066137.

Salminen, A. (2003). New public management and Finnish public sector organisations: the case of universities. In A. Amaral, V. L. Meek, & I. M. Larsen (Eds.), The higher education managerial revolution? (pp. 55–75). Dordrecht: Springer.

Sbragia, R. (1984). Clarity of manager roles and performance of R&D multidisciplinary projects in matrix structures. R&D Management, 14(2), 113–126. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.1984.tb01150.x.

Schwartzman, S. (Ed.). (2008). University and development in Latin America: successful experiences of research centers (Global Perspectives in Higher Education). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Scott, W. R. (2008a). Institutions and organizations: ideas and interests. London: Sage Publications.

Scott, W. R. (2008b). Approaching adulthood: the maturing of institutional theory. Theory and Society, 37(5), 427–442. doi:10.1007/s11186-008-9067-z.

Selznick, P. (1966). TVA and the grass roots : a study in the sociology of formal organization. New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row.

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore, N.J.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stensaker, B., & Harvey, L. (2011). Accountability in higher education: global perspectives on trust and power. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Tapper, T., & Palfreyman, D. (2011). Oxford, the Collegiate University: conflict, consensus and continuity. Dordrecht: Springer.

Vorley, T., & Nelles, J. (2012). Scaling entrepreneurial architecture: the challenge of managing regional technology transfer in Hamburg. In R. Pinheiro, P. Benneworth, & G. A. Jones (Eds.), Universities and regional development: a critical assessment of tensions and contradictions (pp. 181–198). Milton Park and New York: Routledge.

Vukasovic, M., Maassen, P., Nerland, M., Pinheiro, R., Stensaker, B., & Vabø, A. (2012). Effects of higher education reforms: change dynamics. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Welch, A. R. (2005). The professoriate: profile of a profession. Dordrecht: Springer.

Whitley, R. (2008). Constructing universities as strategic actors: limitations and variations. In L. Engwall & D. Weaire (Eds.), The university in the market (pp. 23–37). London: Portland Press Ltd.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kaare Aagaard and two anonymous reviewers for their contribution and insightful comments on an earlier version of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinheiro, R., Stensaker, B. Designing the Entrepreneurial University: The Interpretation of a Global Idea. Public Organiz Rev 14, 497–516 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-013-0241-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-013-0241-z