Abstract

Electoral campaigns are increasingly reliant on small donations from individual donors. In this work, we examine the influence of racial and partisan social descriptive norms on donation behavior using a randomized field experiment. We find that partisan identity information treatments significantly increase donation behavior, while racial identity information has only small and insignificant effect compared to the control. We find, however, significant variation by racial status. For minorities, information about the behavior of other donors in their racial group is as powerful or more powerful than information about co-partisan behavior, while white respondents are much more responsive to information about co-partisan behavior than to information about co-racial behavior. Our results show that partisan and racial identity based social normative information can have a strong effect on actual donation behaviors and how these normative motivations vary across racial groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Political donations are essential to campaigns and small dollar donations have increased drastically in recent election cycles (Magleby et al., 2018).Footnote 1 As such, understanding what influences individual donation behavior has important practical implications. One potential motivator for donor behavior is social normative expectations (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Social descriptive normative appeals regularly feature in campaign fundraising (Hassell & Wyler, 2019) and affect many important political behaviors (Garcia Bedolla & Michelson, 2012; Gerber & Rogers, 2009; Panagopoulos, 2010).Footnote 2

Unfortunately, we know relatively little about social descriptive normative information’s effect on individual donations.Footnote 3 Instead, our knowledge focuses on campaign messengers, campaign targeting (Hassell and Quin Monson 2014; Grant & Rudolph, 2002; Magleby et al., 2018) and the purposive benefits donors accrue (Ansohlebehre et al. 2003; Francia et al., 2003; Magleby et al., 2018; Broockman & Malhotra, 2020).Footnote 4

However, there are good reasons to believe social descriptive norms are important in campaign donors’ decisions. Descriptive normative information provides insights regarding others’ actions in similar situations and has strong effects on human behaviors (Cialdini & Trost, 1998; Cialdini et al., 2006; Goldstein et al., 2008) and political behaviors in particular (Anoll, 2022; Garcia Bedolla & Michelson, 2012; Gerber & Rogers, 2009; Hassell & Wyler, 2019; Morton & Ou, 2019; White & Laird, 2020). Lastly, although not looking specifically at norms surrounding racial and gender identities, donors sharing racial or gendered identity (or both) with a candidate are more likely to donate to that candidate (Grumbach & Sahn, 2020; Grumbach et al., 2022; Thomsen & Swers, 2017).

In this study, we investigate the impact of descriptive normative information on individuals’ political donations. We also examine whether effects differ by reference group used or across groups.Footnote 5 Specifically, we examine whether descriptive normative information about partisan identities (same partisan donors) and racial identities (same racial group donors) encourage political donations.

Our experiment randomly assigned registered voters to receive information about the average contributions of other individuals (varying the reference group used—either information about general behaviors or the behaviors of those sharing a racial or political identity) while holding constant information about donation frequency and amount. Thus, we identify racial and partisan descriptive social normative information’s effects on individual donation behavior and whether those effects vary across groups.

Overall, information about the behavior of co-partisans significantly increases donation behavior, while information about donors from the same racial groups has only a mild effect. However, there are important heterogeneities. While the effect of information about the behavior of co-ethnic donors is insubstantial among whites, for minorities it is much larger.

This study provides the first insights into the role descriptive social normative information plays (or fails to play in some circumstances) on individual political donation behaviors. We show descriptive partisan and racial social normative information have a strong influence on political fundraising, but effects vary across racial groups.

Partisan and Racial Social Norms and Political Behaviors

People primarily donate to political campaigns for their own internal satisfaction, rather than for external benefits (Francia et al., 2003; Magleby et al., 2018). While limited work shows social descriptive normative information referencing actions of other co- and opposite-party partisans and neighbors motivates donation behavior (Augenblick & Cunha, 2015; Perez-Truglia & Cruces, 2017),Footnote 6 we know little about how racial identity social descriptive normative information affects donation behaviors.

Previous work on social descriptive norms, however, drives our expectations about how group based descriptive social normative information might affect donation behavior. Descriptive normative information is information about how others behave and what they do, and does not rely on enforcement or visibility/monitoring like injunctive social norms. Extensive work has shown descriptive normative information encourages individuals to align their behaviors to the norm (e.g., Cialdini et al., 2006; Goldstein et al., 2008).

Descriptive normative information is powerful, in part, because it provides heuristics about what successful people do (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Individuals use descriptive normative information as a decisional shortcut, choosing actions likely to be appropriate for given situations (Cialdini et al., 1990). As such, in-group social descriptive normative information should be even more powerful because it indicates how people like us successfully navigate life. The provision of normative information is most effective when individuals identify with the source of the descriptive normative information (Tankard and Paluck 2016) and feel connected to that group (Anoll, 2022; Bonilla & Tillery, 2020; Dawson, 1994).

These in-group descriptive social normative information effects also are apparent in other political behaviors. Social norms communicated through in-groups have a strong effect on turnout (Garcia Bedolla & Michelson, 2012; Valenzuela & Michelson, 2016) and vote choice (Chandra, 2006; Landa & Duell, 2015; Schnakenberg, 2013; White & Laird, 2020). As such, we hypothesize that descriptive social normative information regarding partisanship and race are likely to influence campaign donations.

In this work, we differentiate between the effect of descriptive social normative information by the reference group used, specifically those invoking identities based around given attributes (e.g., racial and ethnic groups) and those invoking identities based around chosen attributes (e.g., occupation and party affiliation). We focus on racial identity, emphasizing shared race and ethnicity, and partisan identity, emphasizing shared partisan affiliations. Given the previous work outlined above, we expect descriptive social norms emanating from racial and partisan identities should have a positive influence on individuals’ propensity to donate to political campaigns.Footnote 7All else equal, information regarding the donation behavior of other donors who share their identity is expected to induce donors to increase campaign contributions relative to information about donation behavior that does not include information about the behavior of others who share their identity. Our reasoning gives rise to the following hypothesisFootnote 8:

Hypothesis 1

Information about the behaviors of those who share an individual’s identity is likely to increase donation behavior.

However, descriptive social normative information may interact with different social identities to affect behavior differently (Klar, 2013). Information about the behavior of minorities often reminds minorities of their disadvantaged political status, rallying them around candidates most likely to help them (White & Laird, 2020). Racial and ethnic identity is more salient for minorities than whites (Dawson, 1994; Morton et al., 2020; Steck et al., 2003; Valenzuela & Michelson, 2016) and, as such, information about in-group behaviors should prompt a greater response among minorities. In contrast, white identity is much less salient for whites (Steck et al., 2003) and only matters in specific social and electoral contexts (Abrajano & Hajnal, 2015; Holbein & Hassell, 2019; Petrow et al., 2018).Footnote 9 As such, we pre-registered that the effect of descriptive social norms emanating from shared racial identities will be fundamentally different for minorities than for whites:

Hypothesis 2

Different identity based descriptive social normative information has differential marginal effects on giving conditional on donors’ racial and ethnic status.

Hypothesis 2a

Inclusion of racial identity descriptive social normative information should increase donation behavior more for minorities than for whites.

Hypothesis 2b

Inclusion of partisan identity descriptive social normative information should increase donation behavior more for whites than for minorities.

Lastly, we note that political financial contributions are political behaviors, meaning there are substantive selection effects and significant barriers to entry. Individuals uninterested in politics are unlikely to give (Verba et al., 1995). Thus, we preregistered that treatments are more likely to affect previous donors.

Hypothesis 3

Individuals who have given to campaigns previously will be more responsive to racial and partisan identity descriptive social normative information than nondonors.

Research Design

To test the effect of partisan and racial identity descriptive social normative information on political donation behaviors, we conducted a field experiment manipulating the information voters received about political contributions.Footnote 10 All subjects were registered voters randomly selected and assigned to control and treatment groups. We informed subjects of the average contributions of other individuals and varied the identity of those other individuals. We then used campaign finance records to identify effects of each treatment on donation behavior.

Our experimental design allows us to causally identify the effects of different identity-based social descriptive normative information on donation behavior. Although previous work documents differences in donation behaviors across racial groups (Francia et al., 2003; Magleby et al., 2018; Verba et al., 1995), these correlations may be driven by campaigns intentionally targeting politically active individuals (Grant & Rudolph, 2002; Hassell and Quin Monson 2014). As such, our work uses an experimental design to identify the effects of racial and partisan identity-based social descriptive normative information on the decision to contribute financially to political campaigns.

Measuring the impact of our treatments on donation behavior faces two challenges. Firstly, due to social desirability bias self-reported campaign contribution data may not reflect actual behavior (e.g., Burt & Popple, 1998; DellaVigna et al., 2016; Karp & Brockington, 2005; Parry & Crossley, 1950), especially when dealing with racial identities (Garcia Bedolla & Michelson, 2012; White & Laird, 2020). Secondly, while pre-treatment measurement yields greater statistical power, it is hard to design without introducing bias in identifying treatment effects (Broockman et al., 2017; Montgomery et al., 2018).

We solve these challenges by conducting our study in Florida and using actual political donation information from Florida campaign finance records.Footnote 11 Unlike the limited data available from the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) which does not itemize donations below $200, the Florida Division of Elections makes public every donation, regardless the size, on the Florida Campaign Finance Database.Footnote 12 Public campaign finance records also provide pre-treatment measurements of individual donation behavior without contaminating treatment effects. As such, we can precisely estimate treatment effects and control pre-treatment variances across experimental groups. Our experiment consists of three phrases.

Phase 1: Constructing the Sample

The first phase entailed defining the setting in which to run our experiment, developing randomization strategies, and identifying the sample. Because this study requires a racially diverse subject pool, and because of the public and comprehensive nature of campaign finance records, we conducted our experiment in Florida. The U.S. Census Bureau’s diversity index (the likelihood that two people chosen at random will be from different race and ethnicity groups) rates Florida at 64.1%, close to the national level of 61.1%.Footnote 13

First, we conducted a representative survey of Florida voters using a Florida based research firm.Footnote 14 We obtained voter registration information from the Department of State of Florida. This information includes registered voters’ name, address, date of birth, party affiliation, phone number, and email address. We randomly pulled registered voters’ names, address, and their email from the Florida registry. With the help of the research firm, we constructed a random sample by contacting registered voters using the email addresses available through the Florida voter file.Footnote 15 We collected donation behavior of Florida voters based on 1502 respondents asked to self-report their donation frequency and the amount they had donated.

We constructed random samples for our experimental groups with another 2676 survey respondents. We used this second sample for a number of reasons. First, because we wanted a sample who had not been asked previously about their donation behavior to reduce the potential impact of demand effects (those 2676 survey respondents were not asked donation questions). Second, because we wanted to be confident that these individuals would check their email (approximately 50,000 emails were sent to obtain this sample of respondents), and third, because we were interested in other exploratory questions related to this project but not reported here.Footnote 16

The geographic distribution of our 2676 Florida voters, which closely matches the geographic distribution of voters, is illustrated in Fig. 1. As shown in Tables A1 and A2 of the online appendix, the sample is representative of Florida voters and matches the age, gender, racial, and partisan demographics of Florida voters.Footnote 17 The purpose the surveys conducted in Phase 1 is to verify demographic information collected through the voter file and to collected self-reported information about previous political campaign donations used to construct the interventions in Phase 2.

Phase 2: Implementation of Treatments

Using the second sample of respondents collected in Phase 1, we randomly assigned the 2676 survey respondents to one of three treatments.Footnote 18 We use the demographic information (including party affiliation and race) acquired from the Florida voter file and from the survey as the base to construct experimental groups.Footnote 19 The Control Group consists of 980 voters, the Partisan Identity Social Norm Group consists of 728 voters, and the Racial Identity Social Norm Group consists of 968 voters. As shown in the Online Appendix, there are no pre-treatment imbalances in gender, age, or race across treatment groups. More importantly, there are no significant differences across treatment groups in (1) the proportion of voters who donated in 2018–2020 prior to the treatments, (2) the amount given prior to the treatments, and (3) the number of donations given prior to the treatments.Footnote 20

Our sample included non-partisans (No Party Affiliation or NPAs), or “independents,” registered voters who were not affiliated with either the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. Because they did not register with a party, we randomly assigned independents to either the Racial Identity Social Norm treatment or the Control Group. Although independents often include “leaners” whose voting behavior often mirrors those of partisans, we do not to treat them as partisans because partisan identity shapes other political behavior beyond voting even when political attitudes are the same (Huddy et al., 2015).Footnote 21 When non-partisans are excluded from the Control Group, there are no differences between the Control and Partisan Identity Social Norm treatments as noted above and no significant differences in partisan identity. In the empirical analysis, unless otherwise noted, we exclude non-partisans when comparing the Partisan Identity Social Norm Group to the Control Group.

Treatments were emailed from Florida public university account.Footnote 22 The main content was identical across treatments, with the exception of the identity based social descriptive normative information. The methodological approach used in our study, constructing and delivering information to convey descriptive social norms, is consistent with previous work such as Frey and Meier (2004), Shang and Croson (2009), Kessler (2017), Gerber and Rogers (2009), Hassell and Wyler (2019), Condon et al. (2016), Murray and Matland (2014) and Panagopoulos et al. (2014). Participants were randomly assigned to receive one of three different treatments. In the Control Group, neither the party affiliation nor racial identity of the other donors was mentioned. In the Partisan Identity Social Norm Group, voters received information about the donation amount and frequency of other voters with the same party affiliation (i.e., Democrats received information about Democrats and Republicans about Republicans). Individuals assigned to the Racial Identity Social Norm Group received treatment information about the donation behaviors of other individuals of the same racial group (i.e. Hispanic and Latinos received information about Hispanics and Latinos, Blacks about Blacks, and whites about whites). The Control and Racial Social Norm treatment groups consists solely of individuals who are either Black, Hispanic, or White.

The text of the emails is below and shows in brackets the randomized treatment component. A complete copy of a control group email is reported in Online Appendix C.1.

One of the most important ways that you can make sure your voice is heard by policymakers is to show support by donating money to a political campaign. Research has shown that just being a donor, regardless of the amount or to whom the money was given, makes politicians more responsive to your request. That’s why it’s important that more voters like you are involved in the political process!

Ever wondered how much you have given compares with other [Florida/(Republicans/Democrats)/(Black/Hispanic & Latino/white)] voters? Here are some statistics about the donation behaviors of [Florida/(Republicans/Democrats)/(Black/ Hispanic & Latino/white)] voters in the most recent state election cycle:

[Florida/(Republicans/Democrats)/(Black/Hispanic & Latino/white)] voters gave at least one donation and donated at least $15 to $30.

The email also included graphics associated with the specific treatment (see Fig. 2) and a link to a webpage containing basic information and links to webpages of major party candidates running in contested state senate elections.Footnote 23

Because we were interested in causally identifying the effects of the racial and partisan identity-based descriptive normative information, we kept information provided about the amount and number of donations other donors gave constant. As such, as noted in the text of the emails above, we intentionally used a range of the average amount and frequency of contribution, and we applied this same information across treatments. Such a design allows us to avoid deception while accommodating group differences in donation history. Because our primary interest is to identify the effect of information about the donation behavior of individuals who shared a racial or partisan identity on political contributions and potential heterogeneous effects, the only variation in treatment was the partisan and racial identity of the comparison group described.Footnote 24 Treatment emails (Phase 2 of the study) were sent out on 15 October 2020, 18 days prior to the 2020 state legislative elections. Emails were delivered simultaneously and sent only once.

Phase 3: Collection of Donation Data

Critical to our study, we need to measure voters’ donation behavior post-treatment to identify the extent to which subjects’ donation behavior was influenced by the normative information. Since giving political donations is both socially desirable and costly and stated behaviors of costly yet socially desirable behaviors are often fundamentally different from actual behaviors (Berinsky, 1999; LaPiere, 1934) and differences in social norms across groups might cause differences in reporting relative to actual behaviors across groups (White & Laird, 2020), we are primarily interested in what our subjects do rather than what they say. Hence, we examine individuals’ actual behaviors using Florida Campaign Finance records.Footnote 25

We use Florida campaign finance data for two reasons. First, our email treatments specifically highlighted Florida donor behavior in state legislative elections and included a link to lists of major party state senate candidates running in contested elections. Second, in Florida, all donations are recorded no matter the size of the donation (in contrast to data available from the FEC which does not itemized reports of donations under $200), thus allowing us to avoid concerns of data censorship.Footnote 26 Given the reference amount in the email was small ($15 to $30), if we use FEC data, many individuals who might respond to the treatment by giving a similarly small amount would not be reported in the data thus limiting our ability to identify causal effects.Footnote 27

The Florida Campaign Finance records contain donors’ names and addresses, contribution amounts, the receiver’s identity, and importantly, the date of donation.Footnote 28 Because there can be a time gap between the date of donation and when it is publicly available online we downloaded public records six months after implementing treatments to avoid missing data caused by reporting delays.Footnote 29 Since subjects in our sample were registered voters in Florida, Florida campaign finance data can be merged to our sample using names and addresses to identify whether our interventions affected donation behavior in treatment groups compared to the control group.

In this study we did not track when our emails were effectively received (i.e., opened and read) by subjects and we could not have tracked the follow-up solicitations donors received from campaigns after their first donation. According to IRB protocols at our institution, we were not allowed to collect subjects’ internet behaviors without consent. As stated earlier, to minimize the demand on subjects in a field study conducted through emails, we did not ask subjects for the consent of tracking their internet footprints (i.e., when they read our emails or visited the websites provided in the emails), therefore we did not record these data even if such data collection may have been technically feasible. Moreover, whether tracking email click-throughs is effective is debatable as individuals might internalize and be affected by the email content but not use the links in the email to make a donation. We might reasonably expect they could be more likely to respond to other solicitations because of the treatment email content.

Experimental Results

Random assignment and negligible pre-treatment differences allow us to identify treatment effects by directly comparing outcomes in the control and treatment groups. For all statistical tests, we used one-tailed tests when our hypotheses predict a directional relationship between quantities of interest. We use two time-windows to identify subjects’ responses to our treatment information. The first window is 3-weeks (between 16 October 2020 and 5 November 2020), which starts from the day after our intervention and ends the week of Election Day. The second time window is 10-weeks (between 16 October 2020 and 24 December 2020), starting from the day after our intervention until the week of winter holidays. In the 10-week window, about 64% of donations occur in the first 3 weeks. Unless otherwise specified, in the main text our analysis focuses on the results of the first 3 weeks.Footnote 30

Differential Effects of Partisan and Racial Descriptive Normative Information

Before presenting our main findings, we note that in the overall sample individuals rarely donated; about 0.4% in the control group, 0.4% in the racial identity descriptive social norm group, and 1.2% in the partisan identity descriptive social norm group donated. In the overall sample, the differences between the control and racial identity descriptive social norm treatments are close to zero and not statistically significant (0.4% vs. 0.4%, p > 0.1), but as expected, we find that individuals in the partisan identity social norm treatment were about three times as likely to make a political contribution (0.4% vs. 1.2%, one-tailed t-test, p = 0.043) compared to partisans in the control group.

Our main analysis, however, focuses on treatment effects on the previous donors who donated at least once in the most recent election cycle (consistent with the overall randomization process, we find no imbalances in randomization among the subsample of previous donors).Footnote 31 We focus on previous donors because we expect previous donors to be more responsive to the treatments. Indeed, we find that approximately 96% of post-treatment donations were contributed by those who had donated previously.Footnote 32 All the previous donors in our study have a clear racial identity as either Black, Hispanic, or White recorded in their registered voter files, ensuring our analysis remains focused on relevant racial groups and excludes any potential ambiguity.

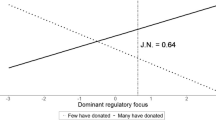

As shown in Fig. 3, there are significant and substantive differences between the control and partisan identity social norm groups among previous donors. About 3.7% of the control group (excluding independents) donated after our intervention compared to 34.6% the partisan social identity group (one-tailed t-test, p = 0.002, independents are excluded from the Control Group in this statistic).Footnote 33

The likelihood of donation by treatment and sample. Notes: The numbers next to the point estimates are the mean difference of the likelihood of giving between the treatment groups and the control group. The label below each set of the point estimates shows the treatment group that voters were randomly assigned to. The analysis focuses on previous donors only. In the comparisons between Control and Partisan Information, the non-partisan voters in the Control group are excluded to make Control and Partisan comparable. p-values are results of one-tailed t tests. Takeaway: Partisan Identity Social Norm treatments encourage greater contribution activity relative to the control, while Racial Identity Social Norm treatments have little effects in the overall sample

In addition, we can also examine the amount and number of donations after treatment to identify treatment effects. We choose to use a non-parametric equality-of-medians test to compare the distributional differences of the two quantities, given that the distribution of donations is skewed. Moreover, when the mean value is significantly influenced by outliers and/or when the sample size is small, the nonparametric approach is preferable to parametric tests (Siegel, 1956; Wilcox, 2011).Footnote 34 We find that both the median frequency of donations and median amount donated in the partisan identity social norm group is significantly higher than it is in the control group (median test, p = 0.004 and 0.004, respectively; Mann–Whitney, p = 0.004 and 0.005 respectively).Footnote 35 On the whole, combined with previous analysis, we can confidently conclude the partisan identity descriptive normative information has a strong positive effects on political contributions, consistent with Hypothesis 1.

In contrast, relative to the control group, we find smaller effects of the racial identity descriptive social norm treatment. About 14.3% of previous donors contributed, a percentage that is larger but statistically indistinguishable from the control group. The results of a median test also suggest the distributional differences in the number and amount of donations between the racial identity social norm group and the control group is minimal.Footnote 36 Taken together, these results suggest that social information about the donation behavior of those who share the same racial identity may not necessarily establish or serve as effective descriptive social norms that prompt previous donors’ giving at the aggregate level.

Differential Treatment Effects on Minorities and Whites

The previous analysis focuses on the overall effects of racial and partisan descriptive normative information. However, as outlined previously (and pre-registered) we expect these effects to vary across racial groups. As stated in Hypothesis 2, we expect racial identity normative information should increase donation behavior more for minorities, while the partisan identity normative information should increase donation behavior more for whites.

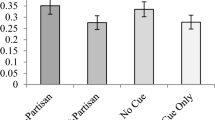

Our results align with expectations. Looking first at the response of racial minorities who had previously donated to a campaign, we find that about 25% of minorities in the racial identity social norm treatment donated compared to 33.3% in the partisan identity social norm treatment group and 0% in the control group.Footnote 37 As shown in Fig. 4, the difference between the racial identity descriptive social norm group and the control group is in the expected direction; it is statistically significant using a t-test (p = 0.031) although it does not quite reach standard levels of statistical significance using the nonparametric Fisher–Pitman permutation test (p = 0.133), however, in the 10-week analysis, which provides greater statistical power, both tests are statistically significant.Footnote 38 Among minorities, differences between the partisan identity social norm group and the control is also statistically significant using a t-test (p = 0.0247), although it is marginally significant using the nonparametric Fisher–Pitman permutation test (p = 0.088).Footnote 39

The likelihood of donation by treatment and ethnic group. Notes the figures in the first (second) row are based on data of 3 (10) weeks. The numbers next to the point estimates are the mean difference of the likelihood of giving between the treatment groups and the control group. The label below each set of the point estimates shows the treatment group that voters were randomly assigned to. In the comparisons between the Control and the Partisan Identity treatment, the non-partisan voters in the Control are excluded to make the Control and Partisan Identity comparable. The analysis of effects among minorities is based solely on Black and Hispanic participants across the Control and Racial Social Norm treatment groups. Similarly, the analysis of effects among White individuals is based exclusively on White participants. p-values are results of one-tailed t tests. Takeaway: Compared to the Control group, Partisan Identity treatments prompt increased donation behavior for both minorities and whites who are previous donors. Racial Identity treatments prompt greater donation behavior among minorities who are previous donors, but not for whites

In contrast, only about 10% of whites in the racial identity social norm treatment gave a donation, compared to 35% in the partisan identity social norm treatment, and 11% who received the control. For whites, the differences between the control and racial identity social norm treatments are not close to statistically significant. However, the difference between the partisan identity social norm treatment and the control are substantively and statistically significant (one-tailed t-test, p = 0.017; permutation-test, p = 0.042). Extending our analysis from 3 weeks’ observations to 10 weeks’ observations provides qualitatively identical results (see the Online Appendix B1).

These comparisons reported above may mask the influence caused by demographic information. In particular, while gender composition is identical across treatment groups both at the aggregate level and when we break down the analysis by individuals’ racial group, the distribution of age groups across treatments is only balanced at the aggregate level but not at the racial group level. In order to control for the effects possibly caused by the imbalanced distribution of age groups, we perform regression analysis and include demographic variables into regressions. These results are reported in Tables A4 and A5 in Online Appendix B.2. We find that after controlling for the possible influence of demographic variables, our main findings regarding the heterogeneous treatment effects on white and minorities continue to hold.

Lastly, we note that while these effects could be the result of minorities placing more emphasis on the behavior of others in their in-group, it could also be because such information updates norms of behaviors differently. Because the reality is that the donor pool is predominantly white (Magleby et al., 2018), the priors for minorities may be that the giving reported in the social information is mainly contributed by whites but not minorities. As a result, the minor effect of racial identity descriptive normative information could be the result of stronger group affiliations or because minorities update their prior beliefs upwards about the average donation while whites do not. While our design, unfortunately, does not allow us to differentiate these possible effects future research should work to identify the specific causal mechanism.

Donation History and Treatment Effects

Lastly, and briefly, our data also provides insights into the effects of information about the donation behavior of co-ethnics and co-partisans on the donation behaviors of those who have given to a campaign previously and those who have not, as we outlined in Hypothesis 3.

Consistent with expectations, and as suggested by our previous analysis, our treatments have the greatest effect on previous donors. In the control group, 3.7% of previous donors contributed while only 0.2% of non-previous-donors engaged in giving (t-test and permutation-test, p < 0.001). Likewise, in the treatment groups, those who did not donate before did not contribute in either time window. In contrast, 14.3% of previous donors contributed in the racial identity group (14.3% vs. 0%, t-test and permutation-test, p < 0.001) and 34.6% of previous donors contributed in the partisan identity group (34.6% vs. 0%, t-test and permutation-test, p < 0.001) in the first 3 weeks after treatment (an effect that grows when we extend observations to 10-weeks).

Implications and Conclusion

In recent election cycles, small dollar donations have played an even more important role in electoral politics (Magleby et al., 2018). We combine theory-driven hypotheses with a field experiment to explore the effect of partisan and racial descriptive normative information on political donations. Our work highlights the important influence that identity based social norms can have on donor behavior, providing both theory-based advancements of the effectiveness of different identity based social norms and their influence on political donor behavior as well as practical implications for real world campaign who often use descriptive normative information in their appeals (Hassell & Wyler, 2019). Identifying small dollar donors’ motivations and understanding how to promote greater participation on this dimension has both theoretical and practical implications.

To begin from the practical perspective, even if our specific messages have never been employed by campaign practitioners, our findings have practical significance that may be of use to those in the field. While the overall impact of our treatment appears small, compared to typical campaign fundraising strategies, the reported effects are highly likely underestimated. First, the time window in which we collect donation data is short relative to the length of a legislative campaign. Second, while campaigns contact potential donors many times over the course of the campaign, we only sent one neutral email to the recipients.Footnote 40

Our findings also reaffirm that individuals who never donated may not be ideal targets of campaign fundraising (Magleby et al., 2018). The majority (about 97%) of voters in our sample had never donated previously in Florida state level campaigns. Although we find statistically significant effects caused by the partisan identity social norm treatments at the aggregate level where both never-donors and previous-donors are considered, these effects are primary driven by the effects on previous donors. Since we find that our interventions have no effects on never-donors, we urge caution in interpreting practical implications of our findings on these people. Even if our treatment effects may be under-estimated as discussed above, future studies should further investigate how (and when) social norms might mobile non-donors to engage in campaign giving.

These results also suggest that encouraging donation behavior through descriptive social normative information may actually exacerbate inequalities in participation. In considering reforms or programs that might help increase participation, scholars have warned that many of these programs have detrimental effects on political equality across groups (Berinsky, 2005; Enos et al., 2014). Our results suggest that efforts to increase participation through the use of normative information may worsen political inequalities by getting those most likely to participate to participate more and doing little to mobilize citizens with a lower propensity to participate.

However, overall, our results show that both racial and political identity-based descriptive social norms can have a substantive effect on the propensity of individual to give political monetary contributions. We find a 35% (3-week) increase in the percentage of individuals donating after receiving information of the donation behavior of donors who are affiliated with the same party (i.e., partisan identity), and a mild and not quite significant increase (14%, 3-week) in the likelihood of giving after receiving the information of the donation behavior of donors who are from the same racial group (i.e., racial identity).

We further show that the effects of racial and partisan social descriptive normative information vary according to the race of the individual. Racial descriptive normative information has substantially stronger effects for minorities than for whites. For donors who are minorities, descriptive normative information to give a political donation based on racial identities are more salient and powerful than for whites. Our results provide evidence that the effect of social descriptive normative information utilizing specific identities to motivate political donation behavior varies across groups.

Finally, while the Florida Campaign Finance records offer several advantages for identifying treatment effects, our study is limited in its ability to investigate how our interventions affect small donors’ giving outside of Florida. As with many empirical research studies conducted in the field, we face the challenge of missing data, as some individuals may donate to candidates or parties that are not reflected in the Florida campaign finance reports, potentially introducing identification bias. Furthermore, most of our sampled donors’ contributions are less than $200, which means that even if they donated to federal-level candidates, their contributions would not be recorded in the FEC dataset. Collecting data on small political contributions at both the state and federal levels poses a challenge that is beyond the scope of our study, but it is an important consideration for future research in this area.

Data Availability

We are open to share our data for replications.

Notes

Magleby et al. (2018) estimate that between 9 and 10 (12 and 13) million donors gave to federal campaigns, committees and PACs in 2008 (2012), most being small dollar donors.

Social norms can be differentiated into injunctive and descriptive norms (Cialdini et al., 1990). Injunctive norms refer to “what others want us to do or … avoid doing,” and compliance to injunctive norms is often associated with social enforcement and monitoring. However, descriptive norms refer simply to what others actually do. People use descriptive norms as decisional shortcut and conform to descriptive norms, in the absence of enforcement and monitoring, because their desire to live successfully (Cialdini and Trost 1998). Our study focuses on the effects of descriptive norms rather than injunctive norms.

Older studies of donation behavior identify three main benefits to donors: purposive, solidary, and material benefits (Francia et al., 2003; Wilson 1974). Recent work, however, “finds little evidence…for material (an individual or group benefit) or solidary (sociability and prestige) reasons for giving” (Magleby et al., 2018, p. 27).

Previous studies have used social information (Broockman and Kalla, 2022; Ou and Tyson 2021), such as the money raised by another candidate (Augenblick and Cunha 2015; Green et al., 2015) or money donated by neighbors (Perez-Truglia and Cruces 2017), but have not examined racial or political identity as potential motivators.

These works are limited in their attempts to estimate the effect of partisan social normative information. Perez-Truglia and Cruces (2017) focus on neighbors and only examine presidential campaign donations over $200. Augenblick and Cunha (2015) only test the effect of messages coming from a single campaign on that campaign’s fundraising.

The precise identification of how descriptive social normative information prompts giving is beyond the scope of our design. While our treatments highlight descriptive behaviors of others in ways consistent with other work on social norms (e.g., Gerber and Rogers 2009; Hassell and Wyler 2019), we cannot exclude the possibility that our experimental interventions may prompt other considerations such as expressive motivations (Magleby et al., 2018; Schuessler 2000). Information about descriptive norms could work because they create social expectations for behavior (Cialdini and Goldstein 2004) or because they help solve coordination problems (Lewis 1969). Unable to differentiate between these two pathways here, this is an area ripe for future work.

Our hypotheses are preregistered and available at EGAP registry (https://osf.io/bz53e).

The messages did not favor any particular candidate, political party, or political organization.

Florida’s nickname, the Sunshine State, is said to refer both to weather and regulations governing transparency.

Florida sunshine laws mandate publicizing donors’ addresses allowing us to match survey respondents from the voter file to donation records. Bulk data from the FEC, in contrast, only provides the city and zip code thus inhibiting such precise matching.

Diversity statistics at the state and national level are available at https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-the-united-states-2010-and-2020-census.html.

See Appendix A3 for additional details of the survey.

Only one registered voter from each address was selected for the study to limit spillover (or multiple forms of the treatment) from one experimental subject to another.

We note that there was no overlap between the respondents of the two surveys.

More information about the Florida voter file is available at https://dos.myflorida.com/elections/for-voters/voter-registration/voter-information-as-a-public-record/.

We limit our experiment to survey respondents in part because we knew, given their response to the survey, that the email in the voter file was active. Although our measure is still an intent to treat effect, because we know these email inboxes were being regularly monitored we can be more confident in measuring treatment effects.

More information about how we determine and categorize participants’ racial identity is available in the Appendix A2.

Based on Florida campaign finance records, 3.2% of individuals in the control group, 3.6% in the partisan identity group, and 2.9% in the racial identity group donated in the 2018–2020 election cycle. We compare the proportion of previous donors using two-tailed t-tests and none are statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. When we focus on previous donors, we compare donation frequency and amount using equality of median tests. These pre-treatment differences are also not significant.

Future work should consider whether or not independent leaners respond similarly to partisan social norms.

Treatment emails were sent from a university email account while the invitations for the original survey were sent by the survey research firm. Thus, there was no association between the two emails that would lead respondents to believe they were connected.

The emails were non-partisan and did not promote any particular candidate or party.

The information about the amount and frequency of donations given to subjects in our study is derived from the self-reported information collected in Phase 1. We note that there are differences between subjects’ reports about their behavior and their actual behavior as reported in Florida’s campaign finance data. The difference may be the result of individuals over-reporting political contributions because giving is socially desirable or because they gave to candidates outside of Florida which would not be in the Florida campaign finance data. Importantly, however, the information regarding the frequency and amount of donation is a range value consistent across treatments and should not affect the identification of treatment effects.

FEC bulk data also does not provide donors’ specific addresses in their bulk data, limiting our ability to match subjects to donations.

Indeed, the average and median donation amount to Florida campaigns of those who donated after the treatment was substantially smaller than $200.

According to Florida’s laws, any political donation (even as small as $0.01) in Florida is recorded. We identified whether and when a subject donated from public information available at https://dos.elections.myflorida.com/campaign-finance/contributions/.

We used individuals’ first name, last name, street number, and zip code as identifiers to match to public records.

Importantly, since we focus on the average treatment effects, the identified effects are equally valid using three-weeks or ten-weeks as the time window. However, it should be noted that we may risk lose informative data by using a shorter time window. Hence, in our analysis, we tested both 3-week and 10-week time windows.

Another question is whether our treatments changed who respondents gave to. Unfortunately, we cannot identify this effect because our treatments reinforce the previous behavior of donors. Before as well as after our treatments, donors gave to candidates who shared the same partisanship or ethnic group, or both, which is consistent with previous research (see Grumbach and Sahn 2020).

Most people, 97% of our sample, had never donated to Florida state-level campaigns. We do not have reliable records regarding whether our sample donated to candidates outside of Florida or to federal campaigns in Florida. We discuss more about this in the conclusion.

Appendix B.3 in the Online Appendix presents the calculations of statistical power. We focus on the analysis of treatment effects caused by partisan identity based social norm. At the aggregate level, the identified effects are sufficiently statistically powerful at the conventional level (i.e., greater than 0.8).

As noted when we describe our results, we also conduct the Mann–Whitney Wilcoxon test as a robustness check, since it takes the ranks of each observation into account and is thus more powerful than the median test (Siegel 1956).

Individuals in the partisan identity descriptive social norm group gave nine donations (a total of $449.33 in which one donor gave $250 and the others gave on average $24.8) while individuals in the control group gave only one donation ($25).

Six donors in the racial identity group contributed a total of $49.

A caveat is that our study is based on a relatively small sample. When we break down the analysis by ethnic and racial status, the power of the effects is between 0.67 and 0.71, which is somewhat underpowered. In order to partially address this issue, we report the results of the non-parametric Fisher–Pitman permutation tests as a robustness check. The non-parametric Fisher–Pitman permutation tests rely on fewer and weaker assumptions and have the highest power (100%) compared to related tests (Siegel 1956). Using a Monte Carlo study, Moir (1998) shows permutation tests have statistically reliable power for as few as eight observations per treatment category. In all of our analysis there are more than eight observations per treatment category.

Based on the data of the 10-week time window, about 38% of minorities in the racial identity social norm treatment donated compared to 0% in the control group. The difference is statistically significant both under t test (p = 0.008) and permutation test (p = 0.042).

Because we might be concerned the fact that blacks are highly likely to be Democrats (and thus are reacting to a partisan cue rather than a racial cue), we also examined the results only for Hispanic/Latinos (who are much more divided along partisan lines in Florida). We find the same directional effects with further reduced statistical power.

Our estimates may even further underestimate the effect because giving at the state level is smaller than the federal level donation given the national media exposure and the nationalization of politics in recent years.

References

Abrajano, M., & Hajnal, Z. L. (2015). White backlash. Princeton University Press.

Anoll, A. (2022). The obligation mosaic: Race and social norms in US political participation. University of Chicago Press.

Ansolabehere, S., De Figueiredo, J. M., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2003). Why is there so little money in US politics? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 105–130.

Augenblick, N., & Cunha, J. M. (2015). Competition and cooperation in a public goods game: A field experiment. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 574–588.

Barber, M., & Eatough, M. (2020). Industry politicization and interest group campaign contribution strategies. Journal of Politics, 82(3), 1008–1025.

Berinsky, A. J. (1999). The two faces of public opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 1209–1230.

Berinsky, A. J. (2005). The perverse consequences of electoral reform in the United States. American Politics Research, 33(4), 471–491.

Bonilla, T., & Tillery, A. B. (2020). Which identity frames boost support for and mobilization in the #BlackLivesMatter movement? An experimental test. American Political Science Review, 114(4), 947–962.

Broockman, D. E., & Kalla, J. L. (2022). When and why are campaigns’ persuasive effects small? Evidence from the 2020 US presidential election. American Journal of Political Science, 67(4), 833–849.

Broockman, D. E., Kalla, J. L., & Sekhon, J. S. (2017). The design of field experiments with survey outcomes: A framework for selecting more efficient, robust, and ethical designs. Political Analysis, 25(4), 435–464.

Broockman, D. E., & Malhotra, N. (2020). What do partisan donors want? Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 104–118.

Burt, C., & Popple, J. S. (1998). Memorial distortions in donation data. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(6), 724–733.

Chandra, K. (2006). What is ethnic identity and does it matter? Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 397–424.

Cialdini, R. B., Demaine, L. J., Sagarin, B. J., Barrett, D. W., Rhoads, K., & Winter, P. L. (2006). Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Social Influence, 1(1), 3–15.

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015.

Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske & G. Lidzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, 4th ed., pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

Condon, M., Larimer, C. W., & Panagopoulos, C. (2016). Partisan social pressure and voter mobilization. American Politics Research, 44(6), 982–1007.

Dawson, M. C. (1994). Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton University Press.

DellaVigna, S., List, J. A., Malmendier, U., & Rao, G. (2016). Voting to tell others. The Review of Economic Studies, 84(1), 143–181.

Enos, R. D. (2016). What the demolition of public housing teaches us about the impact of racial threat on political behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 123–142.

Enos, R. D., Fowler, A., & Vavreck, L. (2014). Increasing inequality: The effect of GOTV mobilization on the composition of the electorate. Journal of Politics, 76(1), 1–288.

Francia, P. L., Green, J. C., Herrnson, P. S., Powell, L. W., & Wilcox, C. (2003). The financiers of congressional elections: Investors, ideologues and intimates. Columbia University Press.

Frey, B. S., & Meier, S. (2004). Social comparisons and pro-social behavior: Testing “conditional cooperation” in a field experiment. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1717–1722.

Garcia Bedolla, L., & Michelson, M. R. (2012). Mobilizing inclusion: Transforming the electorate through get-out-the-vote campaigns. Yale University Press.

Gerber, A., & Rogers, T. (2009). Descriptive social norms and the motivation to vote: Everybody’s voting and so should you. Journal of Politics, 71(1), 178–191.

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472–482.

Grant, J. T., & Rudolph, T. J. (2002). To give or not to give: Modeling individuals’ contribution decisions. Political Behavior, 24(1), 31–54.

Green, D. P., Krasno, J. S., Panagopoulos, C., Farrer, B., & Schwam-Baird, M. (2015). Encouraging small donor contributions: A field experiment testing the effects of nonpartisan messages. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 183–191.

Grier, K. B., & Munger, M. C. (1993). Comparing interest group PAC contributions to House and Senate incumbents, 1980–1986. Journal of Politics, 55(3), 615–643.

Grumbach, J. M., & Sahn, A. (2020). Race and representation in campaign finance. American Political Science Review, 114(1), 206–221.

Grumbach, J. M., Sahn, A., & Staszak, S. (2022). Gender, race, and intersectionality in campaign finance. Political Behavior, 44(2), 319–340.

Hassell, H. J. G. (2022). Local racial context, campaign messaging, and public political behavior: A congressional campaign field experiment. Electoral Studies, 69, 102247.

Hassell, H. J. G., & Quin Monson, J. (2014). Campaign targets and messages in campaign fundraising. Political Behavior, 36(2), 359–376.

Hassell, H. J. G., & Wyler, E. E. (2019). Negative descriptive social norms and political action: People aren’t acting, so you should. Political Behavior, 41(1), 231–256.

Hill, S. J., & Huber, G. A. (2017). Representativeness and motivations of the contemporary donorate: Results from merged survey and administrative records. Political Behavior, 39(1), 3–29.

Holbein, J. B., & Hassell, H. J. G. (2019). “When your group fails: Race and information responsiveness. Journal of Public Administration and Theory, 29(2), 268–286.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Karp, J. A., & Brockington, D. (2005). Social desirability and response validity: A comparative analysis of overreporting voter turnout in five countries. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 825–840.

Kessler, J. B. (2017). Announcements of support and public good provision. American Economic Review, 107(12), 3760–3787.

Klar, S. (2013). The influence of competing identity primes on political preferences. Journal of Politics, 75(4), 1108–1124.

Landa, D., & Duell, D. (2015). Social identity and electoral accountability. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 671–689.

LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230–237.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention: A philosophical study. Harvard University Press.

Magleby, D. B., Goodliffe, J., & Olsen, J. A. (2018). Who donates in campaigns? The importance of message, messenger, medium, and structure. Cambridge University Press.

Moir, R. (1998). A Monte Carlo analysis of the Fisher randomization technique: Reviving randomization for experimental economists. Experimental Economics, 1(1), 87–100.

Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., & Torres, M. (2018). How conditioning on posttreatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 760–775.

Morton, R., & Ou, K. (2019). Public voting and prosocial behavior. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 6(3), 141–158.

Morton, R. B., Ou, K., & Qin, X. (2020). Reducing the detrimental effect of identity voting: An experiment on intergroup coordination in China. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 174, 320–331.

Murray, G. R., & Matland, R. E. (2014). Mobilization effects using mail: Social pressure, descriptive norms, and timing. Political Research Quarterly, 67(2), 304–319.

Ou, K., & Tyson, S. A. (2021). The concreteness of social knowledge and the quality of democratic choice. Political Science Research and Methods, 11(3), 483–500.

Panagopoulos, C. (2010). Affect, social pressure and prosocial motivation: Field experimental evidence of the mobilizing effects. Political Behavior, 32(4), 369–386.

Panagopoulos, C., Larimer, C. W., & Condon, M. (2014). Social pressure, descriptive norms, and voter mobilization. Political Behavior, 36, 451–469.

Parry, H. J., & Crossley, H. M. (1950). Validity of responses to survey questions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 14(1), 61–80.

Perez-Truglia, R., & Cruces, G. (2017). Partisan interactions: Evidence from a field experiment in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 125(4), 1208–1243.

Petrow, G. A., Transue, J. E., & Vercellotti, T. (2018). Do white in-group processes matter, too? White racial identity and support for black political candidates. Political Behavior, 40(1), 197–222.

Schnakenberg, K. E. (2013). Group identity and symbolic political behavior. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 9, 137–167.

Schuessler, A. A. (2000). A logic of expressive choice. Princeton University Press.

Shang, J., & Croson, R. (2009). A field experiment in charitable contribution: The impact of social information on the voluntary provision of public goods. The Economic Journal, 119(540), 1422–1439.

Siegel, S. (1956). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill.

Steck, L. W., Heckert, D. M., & Alex Heckert, D. (2003). The salience of racial identity among African-American and white students. Race and Society, 6(1), 57–73.

Thomsen, D. M., & Swers, M. L. (2017). Which women can run? Gender, partisanship, and candidate donor networks. Political Research Quarterly, 70(2), 449–463.

Valenzuela, A. A., & Michelson, M. R. (2016). Turnout, status, and identity: Mobilizing Latinos to vote with group appeals. American Political Science Review, 110(4), 615–630.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

White, I. K., & Laird, C. N. (2020). Steadfast Democrats: How social forces shape black political behavior. Princeton University Press

Wilcox, R. R. (2011). Introduction to robust estimation and hypothesis testing. Academic.

Wilson, J. Q. (1974). Political organizations. Basic Books.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The experiments and reported findings are not under review at any other journals and have not been previously published in any format.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Paul Herrnson, Jake Grumbach, John Kuk, Joyce Ejukonemu, Ethan Busby, members at APSA Annual Meeting, MPSA Annual Meeting, and seminar audiences at Brigham Young University and Florida State University for invaluable feedback. We thank Braeden McNulty and Kwabena Fletcher for their helpful assistance. This study is pre-registered at EGAP registry (https://osf.io/bz53e). Supplementary material for this article is available in the Appendix in the online edition. Replication files are available in the Political Behavior Data Archive on Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E6ND6G). This research was reviewed and approved by the Florida State University Institutional Review Board. All errors remain the responsibility of the authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cyphers, K.H., Hassell, H.J.G. & Ou, K. Racial and Partisan Social Information Prompts Campaign Giving: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Polit Behav 46, 1913–1933 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09902-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09902-w