Abstract

Does intensifying immigrationenforcement lead to under-reporting of crime among undocumented immigrants and their communities? We empirically test the claims of activists and legal advocates that the escalation of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activities in 2017 negatively impacted the willingness of undocumented immigrants and Hispanic communities to report crime. We hypothesize that ICE cooperation with local law enforcement, in particular, discourages undocumented immigrants and their Hispanic community members from reporting crime. Using a difference-in-difference approach and FBI Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) data at the county level, we find that total reported crime fell from 2016 to 2017 in counties with higher shares of Hispanic individuals and in counties where local law enforcement had more cooperation with ICE. Using the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), we show that these declines in the measured crime rate are driven by decreased crime reporting by Hispanic communities rather than by decreased crime commission or victimization. Finally, we replicate these results in a second case study by leveraging the staggered roll-out of the 2008–2014 Secure Communities program across US counties. Taken together, our findings add to a growing body of literature demonstrating how immigration enforcement reduces vulnerable populations’ access to state services, including the criminal justice system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since the end of the nineteenth century, the US federal government has borne primary legal authority over immigration enforcement—regulating both the entry and exit of immigrants as well as detaining and deporting immigrants within the United States. However, cooperation between federal immigration enforcement and state and local authorities has played an increasingly prominent role in the modern US immigration apparatus (Armenta and Alvarez 2017). This cooperation has intensified over the past three decades as a result of a growing securitization and politicization of immigration, despite limited evidence of any link between immigration and crime. The addition of Section 287(g) in 1997 to the Immigration and Nationality Act and the 2008 Secure Communities program are only two examples of securitized domestic immigration enforcement. Both expanded federal partnerships with state and local law enforcement in order to facilitate the deportation of immigrants identified as posing threats to national security or public safety.Footnote 1 The level and breadth of immigration enforcement activities only increased further under the Trump administration, with President Trump signing Executive Order No. 13768 dramatically escalating border enforcement and expanding cooperation between Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and local authorities just days after assuming office in 2017.Footnote 2

Immigrant rights advocates have argued that such tactics marginalize both undocumented immigrants and immigrant diaspora communities, deterring access to the criminal justice system and increasing racial profiling of ethnic groups associated with undocumented immigration (ACLU 2018). Social science scholarship has also called into question the ability of heightened immigration enforcement to achieve its stated goal of reducing crime (Miles and Cox 2014; O’Brien et al. 2019; Treyger et al. 2014; Hines and Giovanni 2019). Yet despite growing scholarly interest (Collingwood and O’Brien 2019; Wong et al. 2019; Treyger et al. 2014; Miles and Cox 2014; Nguyen and Gill 2016; Donato and Rodriguez 2014), there remains a sparsity of comprehensive subnational research on the effect of immigration enforcement on measurable outcomes related to the criminal justice system and engagement with the state. Difficulties in distinguishing crime reporting from crime rates and estimating local populations of undocumented immigrants have limited quantitative analysis of the link between immigration enforcement and crime reporting.

We investigate how uneven implementation of federal immigration enforcement and the level of cooperation between federal and local law enforcement in particular may produce externalities in political behavior among undocumented immigrants and their relatives and neighbors. Specifically, we examine how policy-driven national variation in immigration enforcement affects individuals’ propensity to utilize the criminal justice system. Our work builds on insights from research showing how certain characteristics of groups and individuals influence the rate of utilization of state services (Currie 2006; Aizer 2007; Bertrand et al. 2006; Besley and Coate 1992; Bhargava and Manoli 2015; Chetty et al. 2013) and that areal crime under-reporting is positively associated with immigrant population share (Gutierrez and Kirk 2017; Davis and Erez 1998).

We hypothesize that national policy measures expanding immigration enforcement cooperation with local law enforcement decrease crime reporting among undocumented immigrants and their HispanicFootnote 3 family and community members. With individuals from Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America making up an estimated \(76\%\) of undocumented immigrants in 2016, we argue that spillover effects of enforcement on engagement with the state are most visible among Hispanic communities.Footnote 4 Crime under-reporting may occur due to two possible mechanisms: fear that engagement with the law will lead to deportation and mistrust in law enforcement agents due to racial profiling. However, we also theorize that local policies limiting or supporting law enforcement cooperation may result in variation in the local effects of national immigration enforcement initiatives. While some counties have sanctuary policies, broadly defined by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center as policies that “limit the participation of local agencies in helping with federal immigration enforcement,” other counties actively cooperate with federal immigration enforcement.

We empirically test our hypotheses with two case studies. We first examine the effect of intensified immigration enforcement starting in 2017 as a result of Executive Order No. 13768 using crime data collected under the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program (UCR). We show that total reported crime in 2017 declined significantly compared to 2016 in areas with higher Hispanic population shares. We next examine Executive Order No. 13768’s effects in counties based on pre-existing levels of cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. Consistent with the “chilling effect” of local law enforcement engagement with ICE on undocumented immigrant willingness to report crime victimization as theorized by (Collingwood and O’Brien 2019; O’Brien et al. 2019), we find that counties with sanctuary policies in place did not demonstrate the same patterns of reported crime decrease as counties that cooperate more with ICE. As a mechanism check, we show that Hispanic respondents in the National Crime Victimization Survey were significantly less likely to report crime in 2017 than 2016. We argue that this pattern of results reflects a decline in willingness to report crime rather than changes in crime commission. We use a second case study, the 2008 roll-out of Secure Communities, to further test the implications of our theory and observe similar results. Our findings add to a growing body of literature examining the consequences of punitive state activities on individuals’ relationship to the state (Burch 2013; Laniyonu 2018; Lerman and Weaver 2014a, b; Walker 2014; White 2016) and to groups’ differential access and use of services. Our results also suggest reduced access to the criminal justice system among undocumented immigrant and adjacent populations is a significant consequence of immigration enforcement intensification by the federal government, and that such shocks may be mitigated or exacerbated in localities with policies helping or hindering cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

Immigration and Crime

Our work contributes to a growing literature examining the link between immigration, crime commission, and crime reporting. A wealth of existing work finds immigration has either no impact on crime rates or contributes to a reduction in crime rates (Wadsworth 2010; Lee and Martinez 2009; Ramiro et al. 2010; Butcher and Piehl 1998; Morenoff and Astor 2006; Light and Miller 2018). In one such study, Stowell (2009) indicate a negative effect of immigrant density on total crime rates in their study of U.S. metropolitan areas. Other work has disaggregated crime rates to examine the effects of immigration on particular types of crimes, and similarly finds no or negative associations between immigrant populations and crime rates (Reid 2005; Lee et al. 2001; Wadsworth 2010). Existing research specifically on undocumented immigration reaches a similar conclusion: there is no or limited evidence that undocumented immigration increases crime (O’Brien et al. 2019; Hagan and Palloni 1998, 1999). In an individual-level study in the Los Angeles area, for example, Hickman and Suttorp (2008) find that undocumented immigrants are not more predisposed to commit crime than citizens. A recent cross-sectional analysis found no statistically significant relationship between the size of undocumented immigrant population in 2014 and violent crime rates by U.S. metro area and reported a negative relationship between the size of undocumented populations and property crime rates (Maciag 2017). Similarly, Green (2016) finds no association between the undocumented population and violent crime using estimates of undocumented populations at the state level, though a small positive association between the undocumented population size and drug-related arrests.

While the null and even inverse relationship between immigrant populations and crime rates is well established, academic research is still divided on the root causes. One leading explanation is ‘selectivity theory,’ or the idea that immigrants who come to the United States are more interested in building new lives for themselves and are therefore less likely to commit crime (Stowell 2009). Another theory postulates that immigrants, and specifically undocumented immigrants, are less likely to engage with the criminal justice system through reporting crime victimization. In their case study of Phoenix, Menjivar and Bejarano (2004) document a perception of bias in policing and unwillingness to report crimes among Central American immigrants. Another qualitative study reveals a lower than expected rate of police calls by LatinaFootnote 5 women experiencing domestic violence in the Washington D.C. metro area (Ammar 2005). Examining NCVS data in the 40 largest metropolitan areas in the US, Comino et al. (2016) find undocumented immigrants are four times less likely to report crime. These findings are complicated by work that finds no differential reporting rates between documented immigrants and U.S. born individuals. Separate studies of immigrant and ethnic minority communities in New York City find high willingness among immigrants to report crime victimization to law enforcement (Khondaker et al. 2017; Davis and Henderson 2003). The restriction of much of these studies to one metropolitan area, however, limits the generalizability of their findings. Our study looks beyond the role of an individual’s citizenship status in influencing their decisions to report crime to show how restrictive policies can change considerations for both undocumented immigrants and adjacent communities.

Immigrant Engagement with the Criminal Justice System

Studying immigrants and their communities’ engagement with the criminal justice system is an increasingly relevant line of inquiry as local law enforcement becomes further embedded in the federal immigration enforcement apparatus. A growing body of work examining the impact of Secure Communities and Section 287(g)—two programs that increased local enforcement of federal immigration policies—find little effect on overall crime reduction (Treyger et al. 2014; Miles and Cox 2014; Nguyen and Gill 2016; Donato and Rodriguez 2014). Limited scholarship, however, has found that immigration enforcement may reduce certain types of crimes, without explicitly accounting for the possibility that such changes may be driven by crime reporting rather than crime commission. For example, Miles and Cox (2014)’s study of the Secure Communities program found that the number of non-citizens detained by ICE had a negligible effect on overall crime rates, although property crime rates appeared to decrease for some specifications. Koper et al. (2013)’s case study of Prince William County, VA found that aggressive immigration enforcement policies only reduced one type of violent crime, though inadvertently harmed police relations with immigrant communities in part by reducing willingness to report crime victimization. The damaging effects of local authorities’ cooperation with federal immigration enforcement on trust is empirically documented by Wong et al. (2019). Collingwood and O’Brien (2019) find that the passage of SB4, a Texas law increasing local cooperation with immigration authorities, had a chilling effect on 911 calls made in El Paso, a city with a large foreign-born population.

Reluctance to report crimes is perhaps the largest consequence of the erosion of trust in local authorities due to increased enforcement. Multiple studies based on surveys, state or city-level data, and ethnographic work have documented fear of deportation as a driver of crime under-reporting among undocumented immigrants (Wong et al. 2019; Provine 2016; Menjivar and Simmons 2018). One study found that the fear of deportation was a significant predictor of mistrust in the criminal justice system among Latina women (Messing 2015).Footnote 6 Research has demonstrated that undocumented women under-report domestic abuse due to fear that they or their partners will be deported (Menjivar and Salcido 2002; Menjivar and Bejarano 2004). Ethnographic work has also long shown how restrictive immigration policies with a focus on deportation push non-citizens to avoid contact with the state and lead “shadowed lives” (Chavez 2012). Kittrie (2005) argues that undocumented immigrants themselves may be victimized by criminals at higher rates as a direct consequence of their legal statuses.

In addition to deterring undocumented individuals from reporting crime, intensified immigration enforcement may also have significant spillover effects on adjacent immigrant and non-immigrant communities connected to the direct targets of policies by family, social networks, or shared ethnicity (Cruz Nichols et al. 2018). Policies that disproportionately target minorities such as ‘stop and frisk’ in New York have been shown to have a chilling effect on trust in the state and engagement in political life (Lerman and Weaver 2014b; Weaver and Lerman 2010; Laniyonu 2019). Theodore (2013) and Theodore and Habans (2016) report high mistrust of local law enforcement agents by Latinos.Footnote 7 Hispanic people are overall less likely than other ethnic groups to report violent crime victimization, with possible barriers including language and fears of racial profiling (Reitzel et al. 2004; Rennison 2007).

Such effects have also been documented in the use of other state services. The threat of deportation has been found to influence participation in federal means-tested programs such as Medicaid, Women, Infants and Children Program (WIC), and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), among non-citizens and their relatives (Alsan and Yang 2018; Vargas 2015; Vargas and Pirog 2016; Watson 2014). These effects are particularly pronounced among Hispanic communities in accessing SNAP and Social Security (Alsan and Yang 2018) and in visits to doctors and emergency rooms (Asch et al. 1994; Hardy 2012; White 2014). The consistency of these findings suggests that aggressive immigration policies have spillover effects to other domains in which U.S. residents interact with the state service providers and institutions, as well as spillover to influence the behavior of family members, neighbors, friends, and coethnics of undocumented immigrants. These policy spillovers are larger for those living in localities with large immigrant populations with high immigration enforcement (Maltby et al. 2020; Rocha et al. 2015).

The Role of Local Policies

Finally, our research builds on work examining how local-level policies shape the effects of national-level shifts in immigration enforcement. Research on how local “sanctuary” policies limiting cooperation between local agencies, including law enforcement, and federal immigration authorities affect crime and reporting has generated mixed findings. In a study of 107 U.S. cities with sanctuary policies, Martinez et al. (2018) find that the adoption of sanctuary policies and the undocumented Mexican population are not associated with higher crime rates. O’Brien et al. (2019) find similar results through a matched analysis of comparable cities, finding that cities which introduced a policy of declining ICE detainers demonstrated no statistically significant increase in violent crime.

How local policies may affect crime reporting is less well-understood. Kittrie (2005) argues that local sanctuary policies do not affect crime reporting since undocumented immigrants are not always aware as to whether their jurisdiction has a sanctuary policy in place and the policies themselves are often highly ambiguous, though does not empirically examine this argument. Lyons et al. (2013) suggest that there are lower rates of crime in sanctuary cities as a result of higher trust between officials and immigrant communities. Similarly, a discussion paper on the effect of increased ICE enforcement in 2017 at the state level found that undocumented women were discouraged from reporting domestic abuse, but that sanctuary policies partially offset this impact (Amuedo-Dorantes and Arenas-Arroyo 2019).

Conversely, some counties and states may have policies in place that facilitate their cooperation with ICE in an attempt to increase deportations. The rise of “immigration federalism,” or local attempts to regulate immigration, has manifested in both protectionist and restrictionist policies (Garcia 2019; Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan 2015). While a 2012 Supreme Court decision limited localities’ abilities to unilaterally conduct immigration enforcement, it enabled localities to keep laws in place corresponding with federal immigration law (Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan 2015). Studies of the effects of restrictive local immigration policies are mixed. Chalfin and Deza (2020), for example, argue that local labor-related enforcement policies reduce crime rates by driving out young male undocumented immigrants. Coon (2017), on the other hand, argues that restrictions primarily lead to decreased crime reporting and increased racial profiling of Hispanic individuals. We contribute to this literature by quantitatively examining how pre-existing variation in local cooperation with federal immigration enforcement shapes the effects of restrictive national immigration policies.

Theory and Hypotheses: Immigration Enforcement and Access to the Criminal Justice System

We explore how willingness to engage with the criminal justice arm of the state may shift among undocumented immigrant and adjacent communities as a result of increased immigration enforcement. We argue that willingness to access to the criminal justice system negatively covaries with the intensity of immigration enforcement. We expect to see localities with high levels of cooperation with ICE reducing Hispanic communities’ willingness to report crime, resulting in lower reported crime rates. While our empirical tests are unable to identify the exact causes of decreased interaction with the criminal justice system, we propose two potential underlying explanations: (1) fear of arrest and deportation when reporting crime (2) perceptions of discrimination by law enforcement agents.

Based on reports from the ACLU and other advocacy groups following the 2017 increase in ICE enforcement, fear of personal arrest or arrest and deportation of a family or community member has deterred individuals from reporting crimes in order to avoid courthouses, and limit interaction with law enforcement agents more generally (ACLU 2018). While we are unable to empirically differentiate between reporting by undocumented immigrants and Hispanic communities, there is strong theoretical justification that changes in reporting would be driven by both. A significant majority (70\(\%\)) of undocumented immigrants and a substantial minority (44\(\%\)) of LatinosFootnote 8 surveyed in major metropolitan areas following enactment of the Secure Communities program were less likely to report crime victimization due to fear of police inquiry about their immigration status or the status of friends or family members (Theodore 2013). An increased fear of deportation would therefore drive decreased crime reporting among both undocumented immigrants themselves and Hispanic communities.

The second possible explanation is a perception of discrimination by law enforcement against Hispanic individuals and subsequent unwillingness to report or cooperate in crime reporting. This theorized mechanism builds on research by Desmond et al. (2016), who found that African-Americans in Milwaukee were less likely to report crime for a year after police brutality against an African-American man in 2004.Footnote 9 In a similar manner, increased deportation efforts against undocumented immigrants could result in a broader unwillingness to report crime in Hispanic communities. In either case, we suggest that the result of intensified immigration enforcement may have interpretive effects (Pierson 1993) in which Hispanic communities learn about the increased probability of themselves or their family members being deported through encounters with the criminal justice system and are therefore less likely to report crime.

Based on these two potential explanations, we propose a model of resident-state engagement under which a resident, when choosing to report crime victimization, has two considerations. She must weigh the gravity of the crime against the perceived risk of deportation and/or unfair treatment for herself and members of her community. Therefore, as the level of cooperation between local authorities and immigration enforcement increases in an area, individuals living in communities with significant numbers of undocumented immigrants update their perceived threat of deportation and unfair treatment for themselves or their neighbors while holding constant their evaluation of a crime’s gravity. We assume that following the 2017 increases in ICE enforcement, undocumented immigrants, Hispanic immigrants, and citizens of Hispanic descent continued to experience crime and be victims of crime at the same or similar rates. We argue that increased immigration enforcement instead has the effect of discouraging communities with high Hispanic populations from interacting with the criminal justice system.

While our theory rests on the argument that enforcement against undocumented immigrants will affect both their behavior and the behavior of their communities, data on the number of undocumented immigrants is unreliable at the local level. Following Miles and Cox (2014), we attempt to overcome the difficulty in measuring local concentrations of undocumented immigrants by assuming that areas with larger Hispanic populations also have larger undocumented immigrant populations. Undocumented immigrants of Hispanic origin make up 76\(\%\) of the total undocumented population. In contrast, Hispanic immigrants make up only 50\(\%\) of the total foreign-born population, and approximately 23\(\%\) of the foreign-born population is undocumented.Footnote 10 Research has shown that undocumented immigrants rely heavily on existing social networks to reduce the risks associated with living undocumented and accessing employment opportunities (Durand et al. 2006). While a declining share of the US Hispanic population is foreign-born—though immigrants still made up over 34\(\%\) of the Hispanic population as of 2019—chain migration networks and social networks among the diaspora play a significant role in undocumented immigrant settlement patterns (Odem and Lacy 2009). We therefore predict the effects of immigration enforcement will be most visible in Hispanic communities due to fears about deportation of themselves or undocumented community members and due to mistrust in the police from heightened racial profiling.

H1

Counties with higher Hispanic population proportions will exhibit a decrease in overall crime reporting relative to areas with lower Hispanic population proportions following intensification of federal immigration enforcement policies.

We also expect that the effect of national-level policies on immigration enforcement on individual willingness to report crime is moderated by local-level policies. We argue that the 2017 Executive Order No. 13768 had an uneven immediate effect at the local level based on the existing levels of cooperation between local law enforcement and ICE. If increased deportation risk is truly affecting crime reporting, we expect to see no change in crime rates in areas cooperating with ICE compared to counties with sanctuary policies limiting such cooperation. In this model, reported crime rates are lower in counties cooperating with ICE not because the actual number of crimes has decreased, but instead because fewer victims are willing to report victimization in such counties. Conversely, sanctuary policies limiting cooperation may strengthen undocumented immigrant and community trust in law enforcement and as a result mitigate the effects of a national escalation in enforcement. This hypothesis necessarily requires assuming that undocumented immigrants and diaspora communities are familiar with local policies limiting or enabling cooperation.

H2

Counties in which local law enforcement cooperate with federal immigration enforcement will exhibit a decrease in overall reported crime compared to counties with sanctuary policies limiting cooperation following intensification of federal immigration enforcement policies.

Finally, a decline in crime reporting by Hispanic individuals should be visible in survey or other data explicitly measuring this outcome.

H3

Hispanic individuals will be less likely to report crime victimization to the police following intensification of federal immigration enforcement policies.

Research Design

Main Outcome of Interest: Crime Reporting

Our identification strategy relies on the fact that undocumented immigrants and Hispanic populations are unevenly distributed across the United States. This uneven pattern of settlement allows us to examine H1: that the intensification of immigration enforcement affects crime reporting in those counties with higher proportions of Hispanic populations. Since rates of crime reporting compared to rates of crime commission are unobserved, we use reported crime rates as a proxy for crime reporting. Based on the existing literature documenting no or a negative relationship between immigration and crime, we assume that increased local immigration enforcement will not produce a significant decrease in the actual number of crimes committed. We validate this assumption using a mechanism test based on survey data measuring crime reporting.

In our first case study, we use the end of 2016 as a cut point following Executive Order No. 13768 in early 2017 and use 2017 as the post-treatment year. The first approach we employ is a difference-in-difference model at the county level:

In this model, \(Y_{it}\) refers to our outcome of interest–the total reported crime index—in county i and time t. We include district fixed effects \(\alpha _i\) and time fixed effects \(\lambda _t\). \(D_i\) is the Hispanic population share in county i. The coefficient of interest is \(\delta \) which is an interaction of \(D_i\) and \(Post_t\), an indicator of whether we are in the pre-treatment or post-treatment period. A negative \(\delta \) would support our hypothesis that overall reported crime rates are decreasing in areas with higher percentages of Hispanic people. In other words, the decrease in reported crime rates will be more pronounced than in areas with 20\(\%\) Hispanic population than in areas with 2\(\%\)

We chose the difference-in-difference design in order to account for permanent differences among counties and differences in year that are independent of the treatment effect. By comparing the change in reported crime rate over time between areas with high and low concentrations of Hispanic populations in a difference-in-difference design, we hold constant unobserved heterogeneity in local area crime propensities which might introduce omitted variable bias given selection on Hispanic population concentration. In order for the difference-in-difference to be valid, however, we must make the assumption of parallel trends between treated and control groups. We test the parallel trends assumption in SI-A2 by looking at the treated and control county crime trends in the years prior. If the propensity of undocumented immigrants and Hispanic populations to report crime has changed as a result of increased immigration enforcement, then we would expect there to be a difference in changes in the reported crime rate between areas with high and low concentrations of Hispanic populations only in the treatment year.

Mechanism: Uneven Immigration Enforcement

We test H2: counties with heightened immigration enforcement by local authorities will exhibit a decrease in overall crime reporting, by leveraging local variation in policies that strengthen or limit cooperation with ICE. We predict that reported crime rates in counties with high participation of local authorities in federal immigration enforcement will decrease from 2016 to 2017 in comparison to counties with sanctuary policies that impose limitations on these partnerships. This is because undocumented immigrants and Hispanic people will not fear the same consequences of deportation or discrimination as a result of engaging with local law enforcement in counties limiting cooperation with ICE. Modifying Equation 1 above,

In this model, we substitute the level of local cooperation with ICE for \(D_i\). The coefficient \(\delta \) on the interaction term is our independent variable of interest—the level of local cooperation with ICE interacted with the treatment period. A negative coefficient would indicate that crime declined more between 2016 and 2017 in counties which were more cooperative with ICE.

Mechanism: Crime Reporting

To better identify the mechanism of changes in crime rates being driven by crime reporting rather than the actual level of crime committed, we directly look at reporting rates. To evaluate H3, which predicts those of Hispanic descent to be less likely to report crimes in 2017 compared to 2016, we run a difference-in-difference at the individual level for crime reporting:

In this equation, \(Y_{i}\) is whether or not a victimized NCVS respondent reported the crime to the police, \(D_{i}\) is a binary variable (Hispanic (1) or Not Hispanic (0), \(\lambda _t\) captures time fixed effects, and \(X_i\) represents a vector of covariates for individuals, and \(\epsilon _{it}\) is the error term. The coefficient \(\delta \) on the interaction term is our independent variable of interest—the probability of reporting crime conditional on being Hispanic and responding in treatment period, 2017. A negative coefficient would indicate that victimized Hispanic NCVS respondents were less likely to report their victimization to police.

Data

Uniform Crime Reporting

We utilize a variety of data sources to test our hypotheses. We collect our data on crime rates from the FBI annual crime reporting data on violent and property crimes at the county level (Uniform Crime Reporting UCR). Violent crimes include homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault while property crimes include burglary/trespassing, motor-vehicle theft, property theft, and arson. Following the criminological literature we report crime indices, which represent the number of reported crimes per 100,000 people in a jurisdictional unit. For example, an increase in the violent crime index of 10 suggests that the reported rate of violent crime has increased from 10 to 20 per 100,000 people. We plot the 2017 total crime index, the sum of violent and property crime, by US county in Fig. 1.

American Community Survey

We obtain the Hispanic county population share using demographic data from the annual American Community Survey (ACS)’s 2017 Five Year Estimates. To get a sense of the distribution of our primary independent variable, we plot the distribution of Hispanic population shares in 2017 in Fig. 2.

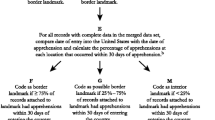

Immigration Enforcement Intensity

In order to measure cooperation with national immigration directives, we use a dataset from the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC), a nonprofit immigrant advocacy organization, which has coded nearly every US county on seven immigration enforcement policies to create a 0 (most cooperative) to 7 (least cooperative) point scale measuring “local entanglement with ICE” based on data obtained using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and expert coding.Footnote 11 While the most cooperative counties include counties whose local law enforcement establishes 287(g) agreements or contracts with ICE to detain immigrants, counties deemed least cooperative have enacted sanctuary policies that impose limitations on how much local agencies can help with federal immigration enforcement. A full list of definitions and county coverage rates for the ILRC scale is available in SI-A1. Figure 3 displays county-level law enforcement cooperation with ICE as of 2017 based on the ILRC data.Footnote 12,Footnote 13

National Crime Victimization Survey

Finally, we use data on crime reporting and ethnic background from the National Crime Victimization Survey from the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, with ‘Hispanic’ proxying for our category of interest. The NCVS is an annual, nationally representative household survey that collects information on crime victimization, demographic data, crime characteristics and reporting of crime to police by households. While the NCVS collects information on violent crime (labeled “personal crime”) at the individual level, property crime data is collected at the household level. A secondary limitation of the 2016 household data is the inclusion of household interviews from the second half of 2015 (as much as 35\(\%\) of interviews in the 2016 file) due to changes in household weights–however, this should not affect the individual personal crimes reporting rates observed.Footnote 14 We therefore only use the personal crimes data from the 2016-2017 waves to test H3—lower personal crime reporting by undocumented and Hispanic individuals.

Case Study 1: 2016–2017 Change in Immigration Enforcement

Five days after Donald Trump assumed the office of the President, he issued Executive Order No. 13768 “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States” that dramatically altered immigration enforcement across the country.Footnote 15 The order, and accompanying implementation memo, tripled the number of ICE officers from 5000 to 15,000, expanded the mandate of ICE, and lowered the barriers for deportation. Notably, the order changed the deportation priorities from those with criminal convictions to include anyone charged with a crime whether or not they are convicted, anyone who has committed acts that could constitute a chargeable criminal offense, and anyone without immigration documents. Around the country, ICE also began to carry out more arrests at courthouses in a break from the Obama-era policy in which courthouse arrests were a last resort for pre-identified targets.Footnote 16

Deportation rates under the Trump administration declined relative to their peak under the Obama administration according to the Transactional Access Records Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.Footnote 17 However, the change in ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) tactics following the 2017 Executive Order No. 13768 increased the risk of engaging with the justice system for undocumented immigrants, particularly as a result of expanded cooperation between ICE and local law enforcement. According to advocates, the knowledge that interaction with the police may lead to deportation reduced immigrant and diaspora populations’ willingness to engage with the criminal justice system. A joint survey of law enforcement officers and court officials by the ACLU and the National Immigrant Woman’s Advocacy Project found that a majority of respondents faced increased difficulties in investigating crimes due to increased immigrant reticence (ACLU 2018). Indeed, some local authorities criticized the increasing partnerships between federal and local immigration enforcement for negatively impacting the relationship between the police and local residents. “You don’t want your local community, your minority communities particularly, afraid to talk to the police, afraid to be witnesses, afraid to come forward as victims of crime if they feel that local police is an arm of immigration,” said San Francisco Sheriff Michael Hennessey.Footnote 18 This statement is consistent with political scientists’ recent conceptualization of the US criminal justice system as the ‘second face’ of the liberal democratic state in its surveillance, regulation, and social control of race-class subjugated communities (Lerman and Weaver 2014b; Weaver and Lerman 2010; Soss and Weaver 2017; Weitzer and Tuch 2006).

However, national-level changes in immigration enforcement do not result in uniform implementation in every community. Since 1989, a number of state and local authorities have enacted sanctuary policies that limit cooperation between local authorities and federal immigration enforcement as the population of undocumented immigrants has risen and immigrant advocacy has strengthened in the United States. Conversely, the ILRC notes that jurisdictions that do not have sanctuary policies in place may actively coordinate with federal enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants. As seen in Fig. 3, wide variation in the level of cooperation between local authorities and federal immigration enforcement existed as of the implementation of Executive Order No. 13768 in January 2017. While approximately 410 counties strengthened their protections of undocumented immigrants and 244 counties increased cooperation with ICE between 2017 and 2018, examining the effect of the policies in place at the date of the order offers insight into how the national enforcement shift interacted with policies at the local level.Footnote 19

In this section, we empirically evaluate claims that the issuance of Executive Order No. 13768 and accompanying intensification of immigration enforcement in 2017 decreased immigrants and their communities’ engagement with the criminal justice system. We also evaluate how variation in local law enforcement cooperation with federal immigration enforcement conditioned the impact of the order on affected communities. Finally, we conduct a mechanism check that the observed changes are driven by reporting using data that directly measures this outcome.

Results: Crime Rates Decreased in Counties with Large Hispanic Population Between 2016 and 2017

We turn to our parametric evaluation of our first hypothesis: that between 2016 and 2017, we expect a decrease in crime reporting by Hispanic populations. As mentioned above, we employ a difference-in-difference approach to rule out unobserved heterogeneity between counties. The independent variable of interest is an interaction term between county Hispanic population and an indicator for the year 2017. Table 1 displays the results of this estimation. Consistent with our hypothesis, there is a smaller relationship between total reported crime and the share of county population that is Hispanic in 2017 vs. 2016. In substantive terms, each percentage point increase in Hispanic population is associated with a 3.11 crime decline in the total reported crime rate per 100,000 people in 2017 relative to 2016. A 10\(\%\) point increase in Hispanic population is associated with a 1.8\(\%\) of a standard deviation decrease in the total reported crime rate. Columns 2 and 3 explore heterogeneity in changes by crime index type. A 1 unit increase in Hispanic population is associated with a decline of 2.52 reported property and .6 violent crimes per 100,000 people in 2017 relative to 2016. Given concerns about uniformity in crime reporting by law enforcement agencies within counties (e.g. Maltz and Targonski 2002), we demonstrate our results’ insensitivity to subsetting to counties with reporting by all local agencies in SI-A3. Finally, in SI-A4, we test whether the results depend on using Hispanic population as a proxy for local undocumented population by re-estimating Table 1 while substituting the foreign born non-citizen population share for Hispanic population share. If intensifying federal immigration enforcement reduces crime reporting among undocumented immigrants and their communities, reported crime rates should not only decline in areas with higher Hispanic population shares, but in areas with large foreign born non-citizen population shares more generally. Consistent with these expectations, foreign-born population is also associated with lower reported crime rates in 2017 vs. 2016.

While these effect sizes appear vanishingly small, it is important to remember that if the hypothesized model of crime under-reporting among undocumented immigrants and adjacent communities is correct, all of the estimated decline in crime reporting is occurring among the percentage of the population is Hispanic, not the county population writ large. For example, if a county’s population is 10\(\%\) Hispanic, a decline of 2.5 in the reported property crime rate per 100,000 for each 1 percent of the county being Hispanic is equivalent to a reduction of 25 in the reported property crime rate per 100,000 among the Hispanic individuals living in that county, assuming that no other subgroup experiences a change in reporting or crime. If some subset of that population is undocumented immigrant and the effect size is entirely driven by reduced reporting among undocumented immigrants, 25 is the lower bound of the decrease in the reported property crime rate per 100,000 among undocumented immigrants. The degree to which the effect size is greater than 25 is inversely related to the share of Hispanic individuals who are undocumented and the share of documented Hispanic individuals who became less likely to report property crimes in 2017. Our data is unable to differentiate between these two possibilities, and given the difficulty in precisely estimating the undocumented immigrant population at the county level, the true effect might be unattainable. Although there is no clear theoretical reason to expect other racial groups to change their propensity to report crime between 2016 and 2017, to the extent that they did, 25\(\%\) would be an over-estimation of the reduction in crime reporting.

Crime Rates Did Not Decline in Counties Limiting ICE Cooperation

We next test our second hypothesis: that crime rates declined in counties that had greater “local entanglement” with ICE relative to counties that limited cooperation. In order to test our hypothesis on the effect of increased local immigration enforcement, we invert the ILRC scale so that 0 represents the least cooperative counties (counties enacting sanctuary policies) and 7 represents the most cooperative counties. In keeping with the foregoing empirical strategy, Table 2 repeats the difference-in-difference model and interacts an indicator for 2017 with the inverted ILRC scale. Consistent with previous evidence, we find that the reported crime rate declined between 2016 and 2017 in counties where law enforcement was more cooperative with federal immigration enforcement. Column 1 of Table 2 demonstrates that a one-unit increase on the ILRC scale (SD: 1.01) is associated with a decrease of 22 crimes per 100,000 people in 2017 relative to 2016. Columns 2 and 3 of Table 2 decompose the effect of increased enforcement intensity on reported property and violent crime considered separately. Once again, both reported property and violent crime rates exhibited a significant decrease between 2016 and 2017. In SI-A5, we evaluate whether our results are spuriously driven by changes in counties with low Hispanic populations where we would not expect ICE enforcement to affect crime reporting. We re-estimate Table 4 while subsetting to the top quintile of counties by Hispanic population and find identical results. In SI-A6, we use nearest-neighbor matching to assuage model dependency concerns and find substantively similar results. Finally in SI-A7, we once again demonstrate that our results are insensitive to restricting the sample to counties with 100\(\%\) data reporting coverage.

Propensity to Report Crime Decreased Among NCVS Hispanic Respondents in 2017

Finally, we turn to evaluating our mechanism: that scaled-up immigration enforcement tactics in 2017 changed the propensity to report a crime rather than commit a crime. We use the 2016 and 2017 waves of individual-level data from the National Crime Victimization Survey. To test whether Hispanic crime reporting declined in 2017 relative to 2016, we interact indicators for whether a respondent was Hispanic and whether they responded in the 2017 wave of the data. We also use pre-made survey weights to be able to make population inferences. The dependent variable is whether the respondent notified the police after being a victim of a personal crime (rape or sexual assault, robbery, aggravated and simple assault, and personal larceny) in the survey year. The NCVS began asking respondents about citizenship status in 2016, but unfortunately access to this variable is restricted. It is unclear what effect such a question will have on how many undocumented immigrants enter the sample, but by limiting the data to 2016 and 2017, we hold constant any differences in the sample this question may have induced.

The results of this analysis are in Table 3. Column 1 presents a basic model without any covariates. The result indicates that Hispanics in 2017 were 12\(\%\) less likely than non-Hispanics in 2017 to notify police of their crime. In column 2, we add demographic controls for age, gender, and whether a respondent identified as ‘black.’ Column 3 adds controls for whether a respondent lives in a rural, urban, or suburban area, their city size, and what region of the US they live in. Both models suggest similar effect sizes to the baseline model.

Case Study 2: Secure Communities Roll-out 2008–2014

One limitation in our first case study is the possible confounding of the treatment of immigration enforcement intensity in 2017 with a generalized ‘Trump effect.’ It is possible that the escalation in anti-immigrant rhetoric by candidate and then President Donald Trump may have affected the perceived safety of undocumented people and citizens of Hispanic background in interacting with government officials independent of the scaling up local immigration activities. In Trump’s speeches, for example, Central Americans have been characterized as gang members, drug smugglers, and human traffickers, and famously “rapists” and “criminals” (Gabbatt 2015). In this case, the results of our first case study would be driven primarily by a fear of engagement with the criminal justice arm of the state due to growing anti-Hispanic sentiment and speech in national-level and local-level politics rather than by changes in enforcement. The predictions from this alternative explanation would also explain the pattern we observe: whether a county contracts and cooperates with federal immigration enforcement is likely correlated with the levels of anti-immigrant and anti-Hispanic sentiment within a county government.

We therefore test our hypothesis that intensifying local authorities’ role in immigration enforcement reduces crime reporting by evaluating whether the staggered roll-out of ICE’s Secure Communities program in US counties between 2008 and 2014 affected crime rates.Footnote 20 The program began in 2008 under President George W. Bush’s administration and expanded under President Barack Obama until it was discontinued in 2014. Under the Secure Communities program, local and state jailers cooperated with ICE leading to the deportation of 700,000 non-citizens (TRAC 2019). Jurisdictions participating in Secure Communities share the fingerprints of arrested individuals with DHS, which compares the fingerprints against its ‘Automated Biometric System,’ which alerted DHS whenever local law enforcement arrested three categories of individuals: 1) a non-citizen who is in the US without legal permission, 2) a non-citizen with legal permission to be in the US but who would be eligible for deportation if they are convicted of their crime, or 3) a naturalized citizen whose fingerprints remain in the database. DHS could then decide to place an ‘immigration hold’ on the arrestee to give ICE time to transfer them to federal custody for deportation. While non-citizens reporting crimes are not directly targeted under this program, our theory predicts that the the local partnerships with federal immigration enforcement blurring the lines between ICE and the local authorities and the disproportionate impact on Hispanic communities affected their calculus on whether to report their victimization.

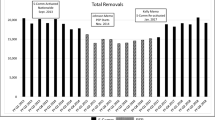

Secure Communities had a phased roll-out across the US, starting with a pilot in Harris County, Texas in November 2008. Full nationwide implementation was only achieved by January 2013. Figure 4 depicts the monthly percentage of the 3138 counties in our sample which had deported at least one individual under the Secure Communities program during its roll-out.Footnote 21,Footnote 22

In line with previous studies of the effects of Secure Communities, we take advantage of the timing of the roll-out of the program across counties to conduct a staggered difference-in-difference analysis of how intensified local cooperation with federal immigration enforcement affects on crime reporting.Footnote 23 Specifically, we test whether counties with higher deportation rates under the Secure Communities program had lower crime reporting. As in our first case study, the measurement we use for crime reporting is the number of reported crimes from UCR. For the intensity of local immigration enforcement, we use the number of deportations as a result of Secure Communities. We hypothesize that if increased law enforcement cooperation with ICE increases undocumented and adjacent communities’ fear of deportation and mistrust in the police, we would expect to see a decline in crime rates with the implementation of the Secure Communities program.

Our unit of observation is monthly county-level reported crime rates and monthly deportation activity between 2002 and 2014. The independent variable is the number of deportations in a given county, year and month due to the Secure Communities booking procedure per 100,000 people (TRAC 2019). We opt for a continuous measure of program intensity rather than a binary indicator for whether Secure Communities is operative in a county for two reasons. First, it better accords with our theoretical focus on how variation in the intensity of deportation activity impacts crime reporting. Second, while jurisdictions may be de jure participants in Secure Communities, local opposition to the program or the threat of civil rights lawsuits produced non-compliance among some local law enforcement officials (Medina 2014). As a result, a binary indicator for Secure Communities activation within a county may not capture the intensity of deportation activity there. The dependent variables are monthly total reported crimes per 100,000, property crimes per 100,000, and violent crimes per 100,000 (FBI 2019).Footnote 24 The model includes county, month, and year fixed effects, as well as control variables for Hispanic origin population share, Black population share, logged median household income, and the foreign-born population share.Footnote 25

Results: Crime Rates Decreased in Counties with Higher Deportations under Secure Communities

Consistent with our previous findings, higher immigration enforcement activity is negatively associated with overall reported crime. (Table 4 Column 1). In substantive terms, a 1 unit increase in the deportation rate due to Secure Communities enforcement per 100,000 is associated with a .03 reduction in the total reported crime rate per 100,000. Among counties which saw any deportation activity, the average deportation rate was 3.18. While this rate appears small, it supports our hypothesized mechanisms: it is not the deportation activity itself but the threat of deportation and fear and confusion about the role of police officers and other state agents that makes undocumented and adjacent communities more reluctant to report crime. It is further suggestive of the fact that even slight increases in immigration enforcement activities can spillover to citizens in communities with high undocumented populations. Finally, these point estimates may be understated as these are measuring crime rates by county, but the effects of these policies were likely concentrated among Hispanic populations, in particular of Mexican origin.Footnote 26

Given the secular decrease in crime occurring nationally during the observation period (e.g. Stowell 2009), it is possible that our time fixed effects strategy accounting for year and month-specific crime shocks fails to account for an overall negative trend in crime. To account for this possibility, we replace year fixed effects with a linear time trend in columns 4–6 of Table 4 and find substantively identical results. This suggests that the negative association we find between deportation intensity and total crime is driven by changes in the threat of deportation rather than spurious correlation between nationally declining crime rates and the increase in deportations due to the Secure Communities program.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper demonstrates how intensification of federal immigration enforcement and cooperation with local authorities affects crime reporting among undocumented and adjacent populations within the United States. In our first case study, we show that the issuance of the 2017 Executive Order No. 13768 scaling up partnerships between ICE and local law enforcement in 2017 led to a decline in reported crimes in counties with higher Hispanic populations from 2016 to 2017 compared to counties with lower Hispanic populations. This effect is not uniform across the US, as we find that counties exhibiting greater cooperation with ICE experienced declines in the total reported crime rate between 2016 and 2017 relative to counties limiting cooperation with ICE. We demonstrate that this decrease in reported crime rates is due to changes in crime reporting rather than in crime commission through our analysis of NCVS data, in which we observe Hispanic respondents were less willing to report crime victimization in 2017 compared to 2016. In a second case study, we test the contextual robustness of our theory using the roll-out of the Secure Communities program between 2008 and 2014 and find an identical pattern of results for reported crime rates as enforcement activity intensified. Our results therefore suggest that a direct byproduct of intensified federal immigration enforcement may be decreasing access to the criminal justice system among undocumented individuals and their communities.

Nonetheless, these findings must be interpreted with several caveats. A primary challenge relates to our inability to differentiate between spillover effect on crime reporting among the broader Hispanic population compared to undocumented immigrants specifically. While we hypothesize both are occurring, without data on legal resident vs. non-resident crime reporting we are unable to effectively differentiate between these hypotheses. A secondary concern lies in our analysis’ reliance on cases of elevated immigration enforcement intensity. A corollary of the theory that restrictive immigration measures reduce crime reporting is that inclusive immigration policies should increase crime-reporting and therefore improve access to the criminal justice system among vulnerable populations. This implication may seem at odds with existing literature that shows sanctuary policies do not lead to increases in crime rates locally (O’Brien et al. 2019; Martinez-Schuldt and Martinez 2019). While it may be that the adoption of sanctuary policies in a country increases undocumented immigrants and their communities' trust in local law enforcement and increases their access to the criminal justice system, our analysis is unable to answer that question. We have instead examined the differential effect of enforcement shocks in countries that have pre-existing sanctuary policies in place rather than the effect of implementing a sanctuary policy. Differential effect of enforcement shocks in counties already adopting such policies rather than the effect of such policies themselves.

A third concern lies with recent debates regarding the criminal justice system as an avenue of recourse for marginalized communities and the existence of alternatives. Long-running abolitionist and defunding debates among activists and scholars brought to fore following the 2020 police killing of George Floyd have called for the end of or reduction of policing and the carceral system, increased investment in communities, and the development of community alternatives to policing (Akbar 2020; Vitale 2017; McDowell and Fernandez 2018; Davis 2011; Gilmore 2007). Qualitative work on the effect of increased cooperation between local law enforcement and federal immigration authorities has argued that such policies have pushed communities further into the “shadows” (Chavez 2012; ACLU 2018), though other work has argued for a more nuanced understanding of undocumented immigrants’ strategies in the aftermath of restrictive policy enactment (Garcia 2019). Recent work has also highlighted the resilience of Latino communities in the realms of civic participation and political engagement (McCann and Jones-Correa 2020). Our findings do not enable us to examine the possibility of Hispanic and undocumented immigrant communities organizing and developing alternatives to accessing the criminal justice system.

Finally, our thesis that local law enforcement’s cooperation with ICE leads to crime under-reporting relies upon differential changes in crime rates correctly identifying a disconnect in crime and crime reporting. The accurate measurement of the ‘ground-truth’ of crime always depends on the extent to which citizens are reporting victimization and we are not aware of a more credible source of data against which to compare our estimates that can also capture variation in the actual level of deportation risk.

Our results also point to avenues for future research. In both of our case studies, we find that the changes in the overall crime rate are almost entirely driven by changes in the property crime rate. The divergence between reported property crime rates and violent crime rates could reflect immigrant engagement with the criminal justice system only in extreme cases of physical harm, which aligns with the findings from criminological research that victims are more likely to report severe crimes to the police (Block 1974; Langton 2012; Tarling and Morris 2010). A promising line of inquiry could dig deeper into the sensitivity of crime reporting to national and local policy changes examining impacts by crime type.

A second direction for further research relates to information; specifically, how policy knowledge diffuses across communities. Our results suggest that residents, green-card holders, and citizens of Hispanic origin perceive national-level changes in immigration enforcement activity and are reactive to such changes. This is in line with a wealth of existing work that establishes that changes in policies can directly lead to undocumented immigrants’ fear of the state (Chavez 2012) and immediate-term shifts in behavior (Garcia 2019), and that there are indeed spillover effects on Latino citizens (Cruz Nichols et al. 2018). However, more work is needed to understand how information is disseminated and what the resulting network effects are within communities. The introduction of additional sanctuary policies by some counties as well as policies enhancing cooperation by other counties in the year following Executive Order No. 13768 complicates the precision of our findings. Yet it also offers grounds for future research on the effects of local-level policies and whether such policies can immediately shape the effects of national immigration enforcement shocks.

Finally, we propose that crime under-reporting is driven by a reluctance to engage with local law enforcement due to either increased fears of deportation for an undocumented individual and for communities with large numbers of undocumented people, or due to a decrease of trust in the police. In the wider scholarship, there is significant evidence for both hypothesized mechanisms. From a survey of undocumented immigrants, Wong et al. (2019) conclude that “when local law enforcement officials do the work of federal immigration enforcement, this further blurs what are already opaque lines between policing and federal immigration enforcement,” which can deter undocumented immigrants and potentially their community members from reporting crimes to the police (5). Alternatively, policies that disproportionately affect a particular community can result in the wider community losing faith and trust in the agents who enforce them, as revealed by the studies of police stops in black and brown communities (Lerman and Weaver 2014b; Fagan et al. 2016; Stoudt et al. 2011). While we are unable to distinguish between these two theories in our analysis, a future research agenda could disentangle and shed light on these processes. In the context of growing research on the scope of policing, identifying these mechanisms has implications for when communities seek to develop alternatives.

In conclusion, our article contributes to a growing literature demonstrating how the intensification of deportation activity further stratifies access to state services (Alsan and Yang 2018; Vargas 2015; Vargas and Pirog 2016; Watson 2014). Citizens or legal non-citizens with undocumented relatives or neighbors may relinquish their access to a state service because the heightened risk of deportation due to federal policy-making outweighs the rights of citizenship or residency. It also shines a light on the consequences of the growing linkages between immigration enforcement and the policing and carceral apparatus. As the debate over the relationship between federal immigration enforcement and local authorities continues, our research underscores the importance of examining the effects of such policies on marginalized communities.

Notes

We use the term Hispanic rather than Latino/a/x as a matter of consistency with our data sources, however, we are sensitive to debates on terminology.

Terminology used in article.

Terminology used in the article.

Terminology used in the article.

Terminology used in the report.

ILRC’s coding includes seven policies: 1. Declines 287(g) Program, 2. Declines ICE detention contract, 3. Limits ICE holds, 4. Limits ICE notifications, 5. Limits on ICE interrogations in jail, 6. Prohibition on asking immigration status, 7. General Prohibition on Assistance to ICE

Counties in black lack an ILRC coding of local law enforcement cooperation with ICE

The ILRC provided us with the raw FOIA data upon request and the present version of the ILRC map is available here.

The NCVS includes sexual assault and simple assault in personal crimes, which the UCR excludes. However, the NCVS does not include homicides or crime against children 11 or younger.

Secure Communities was reactivated on January 25, 2017 under Executive Order No. 13768: “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States”

Deportation rates by county were scraped from Syracuse University’s Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) database on ‘Removals Under the Secure Communities Program.

Some counties appear to never have deported any individuals under the Secure Communities program, whether due to non-compliance during the time window or because they never arrested any individuals whose fingerprints were registered with DHS

Miles and Cox (2014) uses a similar design to study Secure Communities’ effect on crime. We extend their crime data to include 2 years prior to their observation period and two years after their observation period to take advantage of data not available at the time of their publication.

In some counties, crimes are only reported by counties to the federal government quarterly, biennially, or annually. We imputed monthly values for these counties by averaging the total annual crime across each respective time period, following the approach taken by Miles and Cox (2014). We also acknowledge the caveat made by Maltz and Targonski (2002) who report missing data issues with the UCR stemming from reporting variation within counties.

Demographic data is taken from the American Community Survey 5-year estimates.

It is estimated that 78\(\%\) of deportations under Secure Communities were to Mexico. https://econofact.org/secure-communities-broad-impacts-of-increased-immigration-enforcement

References

ACLU. (2018). Freezing out justice: How immigration arrests at courthouses are undermining the justice system. Tech. rep. https://www.aclu.org/report/freezing-out-justice.

Aizer, A. (2007). Public health insurance, program take-up, and child health. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3), 400–415.

Akbar, A. (2020). An abolitionist horizon for police (reform). California Law Review108(6).

Alsan, M. & Yang, C. (2018). Fear and the safety net: Evidence from secure communities. In: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 24731. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24731.pdf.

Ammar, N. H., et al. (2005). Calls to police and police response: A case study of Latina immigrant women in the USA. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 7(4), 230–244.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. & Arenas-Arroyo, E. (2019). Immigration enforcement, police trust and domestic violence. In: IZA Discussion Paper No. 12721. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3483959.

Armenta, A., & Alvarez, I. (2017). Policing immigrants or policing immigration? Understanding local law enforcement participation in immigration control. Sociology Compass, 11(2), e12453.

Asch, S., Leake, B., & Gelberg, L. (1994). Does fear of immigration authorities deter tuberculosis patients from seeking care? Western Journal of Medicine, 161(4), 373.

Bertrand, M., Shafir, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2006). Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 25(1), 8–23.

Besley, T., & Coate, S. (1992). Understanding welfare stigma: Taxpayer resentment and statistical discrimination. Journal of Public Economics, 48(2), 165–183.

Bhargava, S., & Manoli, D. (2015). Psychological frictions and the incomplete take-up of social benefits: Evidence from an IRS field experiment. American Economic Review, 105(11), 3489–3529.

Block, R. (1974). Why notify the police: The victim’s decision to notify the police of an assault. Criminology, 11(4), 555–569.

Burch, T. R. (2013). Trading democracy for justice: Criminal convictions and the decline of neighborhood political participation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Butcher, K. F., & Piehl, A. M. (1998). Cross-city evidence on the relationship between immigration and crime. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: The Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, 17(3), 457–493.

Chalfin, A., & Deza, M. (2020). Immigration enforcement, crime, and demography: Evidence from the Legal Arizona Workers Act. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(2), 515–562.

Chavez, L. R. (2012). Shadowed lives: Undocumented immigrants in American society. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Chetty, N., Friedman, J., & Saez, E. (2013). Using differences in knowledge across neighborhoods to uncover the impacts of the EITC on earnings. American Economic Review, 103(7), 2683–2721.

Collingwood, L., & O’Brien, B. G. (2019). Sanctuary cities: The politics of refuge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comino, S., Mastrobuoni, G., & Nicolo, A. (2016). Silence of the innocents: Illegal immigrants’ underreporting of crime and their victimization.

Coon, M. (2017). Local immigration enforcement and arrests of the Hispanic population. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 5(3), 645–666.

Cruz Nichols, V., LeBron, A. M. W., & Pedraza, F. I. (2018). Spillover effects: Immigrant policing and government skepticism in matters of health for Latinos. Public Administration Review, 78(3), 432–443.

Currie, J. (2006). The take-up of social benefits. In A. J. Auerbach, D. Card, & J. M. Quigley (Eds.), Public policy and the income distribution (pp. 80–148). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Davis, A. Y. (2011). Are prisons obsolete?. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Davis, R. C. & Erez, E. (1998). Immigrant populations as victims: Toward a multicultural criminal justice system. research in brief.

Davis, R. C., & Henderson, N. J. (2003). Willingness to report crimes: The role of ethnic group membership and community efficacy. Crime & Delinquency, 49(4), 564–580.

Desmond, M., Papachristos, A. V., & Kirk, D. S. (2016). Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 857–876.

Desmond, M., Papachristos, A. V., & Kirk, D. S. (2020). Evidence of the effect of police violence on citizen crime reporting. American Sociological Review, 85(1), 184–190.

Donato, K. M., & Rodriguez, L. A. (2014). Police arrests in a time of uncertainty: The impact of 287 (g) on arrests in a new immigrant gateway. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(13), 1696–1722.

Durand, J., Telles, E., & Flashman, J. (2006). The demographic foundations of the Latino population. In: Hispanics and the future of America, (pp. 66–99).

Fagan, J., Tyler, T. R., & Meares, T. L. (2016). Street stops and police legitimacy in New York. In: Comparing the Democratic Governance of Police Intelligence. Edward Elgar Publishing.

FBI. (2019). National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS. https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/nibrs.

Gabbatt, A. (2015). Donald Trump’s tirade on Mexico’s ’Drugs and Rapists’ outrages US Latinos. In: The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/usnews/2015/jun/16/donald-trump-mexico-presidential-speech-latino-hispanic.

Garcia, A. S. (2019). Legal passing: Navigating undocumented life and local immigration law. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California (Vol. 21). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Green, D. (2016). The Trump hypothesis: Testing immigrant populations as a determinant of violent and drug-related crime in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 97(3), 506–524.

Gulasekaram, P., & Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2015). The new immigration federalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gutierrez, C. M., & Kirk, D. S. (2017). Silence speaks: The relationship between immigration and the underreporting of crime. Crime & Delinquency, 63(8), 926–950.

Hagan, J., & Palloni, A. (1998). Immigration and crime in the United States. In J. P. Smith & B. Edmonston (Eds.), The immigration debate: Studies on the economic, demographic, and fiscal effects of immigration (pp. 367–387). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Hagan, J., & Palloni, A. (1999). Sociological criminology and the mythology of hispanic immigration and crime. Social Problems, 46(4), 617–632.

Hardy, L. J., et al. (2012). A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1250–1253.

Hickman, L. J., & Suttorp, M. J. (2008). Are deportable aliens a unique threat to public safety-comparing the recidivism of deportable and nondeportable aliens. Criminology & Pub. Pol’y, 7, 59.

Hines, A. L. & Giovanni, P. (2019). Immigrants’ Deportations, Local Crime and Police Effectiveness.

Khondaker, M. I., Wu, Y., & Lambert, E. G. (2017). Bangladeshi immigrants’ willingness to report crime in New York City. Policing and Society, 27(2), 188–204.

Kittrie, O. F. (2005). Federalism, deportation, and crime victims afraid to call the police. Iowa Law Review, 91, 1449.

Koper, C. et al. (2013). The effects of local immigration enforcement on crime and disorder: A case study of Prince William County, Virginia. In: Koper, C. (ed) Criminology & public policy (vol. 12, pp. 239–276).

Langton, L., et al. (2012). Victimizations not reported to the police, 2006–2010. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice: US Department of Justice.

Laniyonu, A. (2018). The political consequences of policing: Evidence from New York City. Political Behavior, 41(2), 527–558.

Laniyonu, A. (2019). The political consequences of policing: Evidence from New York City. Political Behavior, 41(2), 527–558.

Lee, M. T. & Martinez, R. (2009). Immigration reduces crime: An emerging scholarly consensus. In: Immigration, crime and justice. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 3–16.

Lee, M. T., Martinez, R., & Rosenfeld, R. (2001). Does immigration increase homicide? Negative evidence from three border cities. The Sociological Quarterly, 42(4), 559–580.

Lerman, A. E. & Weaver, V. (2014). Staying out of sight? Concentrated policing and local political action. In: Wildeman, C., Hacker, J. S., Weaver, V. M. (eds) The annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (vol. 651, pp. 202–219).

Lerman, A. E., & Weaver, V. M. (2014). Arresting citizenship: The democratic consequences of American Crime control. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Light, Ml, & Miller, T. (2018). Does undocumented immigration increase violent crime? Criminology, 56(2), 370–401.

Lyons, C. J., Velez, M. B., & Santoro, W. A. (2013). Neighborhood immigration, violence, and city-level immigrant political opportunities. American Sociological Review, 78(4), 604–632.

Maciag, M. (2017). Analysis: Undocumented immigrants not linkedwith higher crime rates. In: Governing Magazine, March.

Maltby, E. et al. (2020). Demographic context, mass deportation, and latino linked fate. In: Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, pp. 1–28.

Maltz, M., & Targonski, J. (2002). A note on the use of county-level UCR data. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18(3), 297–318.

Martinez, D. E., Martinez-Schuldt, R. D., & Cantor, G. (2018). Providing sanctuary or fostering crime? A review of the research on “sanctuary cities” and crime. Sociology Compass, 12(1), e12547.

Ramiro, M., Stowell, J. I., & Lee, M. T. (2010). Immigration and crime in an era of transformation: A longitudinal analysis of homicides in San Diego neighborhoods, 1980–2000. Criminology, 48(3), 797–829.

Martinez-Schuldt, R. D., & Martinez, D. E. (2019). Sanctuary policies and city-level incidents of violence, 1990 to 2010. Justice Quarterly, 36(4), 567–593.

McCann, J. A. & Jones-Correa, M. (2020). Holding fast: Resilience and civic engagement among latino immigrants.

McDowell, M. G., & Fernandez, L. A. (2018). Disband, disempower, and disarm’: Amplifying the theory and practice of police abolition. Critical Criminology, 26(3), 373–391.

Medina, J. (2014). Fearing Lawsuits, Sheriffs Balk at U.S. request to hold noncitizens for extra time. In: New York Times, Section A, Page 10. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/06/us/politics/fearing-lawsuits-sheriffs-balk-at-usrequest-to-detain-noncitizens-for-extra-time.html.

Menjivar, C., & Bejarano, C. (2004). Latino immigrants’ perceptions of crime and police authorities in the United States: A case study from the phoenix metropolitan area. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(1), 120–148.

Menjivar, C., & Salcido, O. (2002). Immigrant women and domestic violence: Common experiences in different countries. Gender & Society, 16(6), 898–920.

Menjivar, C., Simmons, W. P., et al. (2018). Immigration enforcement, the racialization of legal status, and perceptions of the police: Latinos in Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, and Phoenix in comparative perspective. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 15(1), 107–128.

Messing, J. T., et al. (2015). Latinas’ perceptions of law enforcement: Fear of deportation, crime reporting, and trust in the system. Affilia, 30(3), 328–340.

Miles, T. J., & Cox, A. B. (2014). Does immigration enforcement reduce crime? Evidence from secure communities. The Journal of Law and Economics, 57(4), 937–973.

Morenoff, J. D., & Astor, A. (2006). Immigrant assimilation and crime. In: Immigration and crime: Race, ethnicity, and violence, pp. 36–63.

Nguyen, M. T., & Gill, H. (2016). Interior immigration enforcement: The impacts of expanding local law enforcement authority. Urban Studies, 53(2), 302–323.

O’Brien, B. G., Collingwood, L., & El-Khatib, S. O. (2019). The politics of refuge: Sanctuary cities, crime, and undocumented immigration. Urban Affairs Review, 55(1), 3–40.

Odem, M. E., & Lacy, E. C. (2009). Latino immigrants and the transformation of the US South. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Pierson, P. (1993). When effect becomes cause: Policy feedback and political change. World Politics, 45(4), 595–628.

Provine, D. M., et al. (2016). Policing immigrants: Local law enforcement on the front lines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reid, L. W., et al. (2005). The immigration-crime relationship: Evidence across US metropolitan areas. Social Science Research, 34(4), 757–780.

Reitzel, J. D., Rice, S. K., & Piquero, A. R. (2004). Lines and shadows: Perceptions of racial profiling and the Hispanic experience. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(6), 607–616.