Abstract

A prominent explanation for why women are significantly underrepresented in public office in the U.S. is that stereotypes lead voters to favor male candidates over female candidates. Yet whether voters actually use a candidate’s sex as a voting heuristic in the presence of other common information about candidates remains a surprisingly unsettled question. Using a conjoint experiment that controls for stereotypes, we show that voters are biased against female candidates but in some unexpected ways. The average effect of a candidate’s sex on voter decisions is small in magnitude, is limited to presidential rather than congressional elections, and appears only among male voters. More importantly, independent voters display the greatest negative bias against female candidates. The results suggest that partisanship works as a kind of “insurance” for voters who can be sure that the party affiliation of the candidate will represent their views in office regardless of the sex of the candidate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The number of female candidates running for elective office in the United States has been increasing for decades, but women are still underrepresented in politics compared to men. Women hold fewer than one in five congressional seats despite the fact that women compose a majority of the U.S. population. Why is there such an immense disparity in descriptive representation?

One prominent answer is that voters are biased against female candidates. However, theory and evidence also suggest that voters use candidate sex as a proxy for other useful information.Footnote 1 Voters frequently make decisions about unfamiliar candidates based on heuristics, readily available information cues that allow them to reduce the cognitive effort used to gather detailed information (Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Popkin 1991). Voters who are biased against (or toward) female candidates might readily use candidate sex as a shortcut that implies other information about candidates. This is often done through stereotyping, the process of simplified characterization about an individual based on their group membership. Although voters do not necessarily assign feminine attributes to female candidates (Bauer 2017; Brooks 2013; Dolan 2014a, b; Schneider and Bos 2014), voters often stereotype candidates based on their gender and associate certain personality traits and policy positions with men and women (Alexander and Andersen 1993; Huddy and Terkildsen 1993a, b; Kahn 1994; Koch 2002; Lawless 2004; McDermott 1997; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan 2009; Sapiro 1981). For example, lacking direct knowledge of such things, a voter might assume that a female candidate is more focused on domestic policy issues such as education or that a male candidate is more knowledgeable.

At the same time, candidate sex is only one of many informational cues that are available to voters. It is likely that other important cues overwhelm the effect of candidate sex on voting decisions. As a long line of scholarly research has documented, political party is the most likely of these cues (e.g., Campbell et al. 1960; Rahn 1993). The strengthening of partisanship in the electorate in recent years, particularly along “affective” lines, suggests that other cues including candidate sex might have limited influence (Iyengar et al. 2012; Iyengar and Westwood 2015).

Our contribution in this manuscript is threefold. First, and most importantly, using an original conjoint experiment, we uncover voter bias due to the direct effect of candidate sex after accounting for various other information about candidates, especially their partisanship and gender stereotyped attributes. Our research design, which is relatively new in political science, enables us to not only to more closely reflect how candidates are presented to voters than do traditional survey experiments by jointly varying numerous candidate attributes at a time, but also to identify the extent to which candidate sex matters in voter evaluation relative to other crucial cues about candidates that would in real elections be often correlated with candidate sex. For instance, voters in real elections might—wrongly or rightly—believe that male candidates have more experience than female candidates. If these voters value experience, they could prefer male candidates because of their sex, their experience advantage, or both. The conjoint design allows us to separately assess these confounding explanations in a clean way. While this design may not completely account for all possible gender-based stereotypes, it improves on prior experimental research in its ability to minimize such a masking problem—a concern that the effect of candidate sex might have been inflated due to the behavior of “filling in the blanks” among respondents.

Second, we manipulate the level of office that candidates in our experiment are seeking to assess whether the bias toward female candidate varies between congressional and presidential elections. To our knowledge, no experiment has tested whether voters’ treatment of male and female candidates depend on the political office being sought. Our experiment provides a unique opportunity to test the theory of gender-office congruency. As we explain below, this theory predicts a greater bias against female candidates in presidential elections due to the public’s belief that male traits are better aligned with expectations of a president.

Third, we demonstrate how the marginal effect of candidate sex varies across subgroups within the population by carefully scrutinizing the interactions of candidate sex with voters’ background characteristics such as gender and partisanship. While the gender-affinity effect has been tested extensively in the literature, only limited attention has been paid to whether same-gender voting still appears when party cues are present. To mimic the different role that party plays in primary and general elections, our conjoint experiment also randomly creates the context of electoral competition where a pair of candidates shown to voters either shares or does not share the same party label. This enables us to identify whether and to what extent a candidate’s party label helps partisan voters to overcome bias against male or female candidates.

To preview the results, we find that voters use candidate sex as a heuristic even when provided with information on other attributes of candidates such as party affiliations and policy positions. In our experiment, the respondents from the general public exhibit a bias against female candidates and punish them compared to an identical male candidate. Although the average effect of a candidate’s sex on vote choice is relatively small in magnitude compared to the effects of information about party affiliations and policy positions, its impact on election outcomes could be decisive in tight races such as the 2016 presidential elections where small margins of votes separate the candidates. This reality might deter women away from running for elected office in the first place.

At the same time, the bias against female candidates appears only among male voters and is limited to presidential rather than congressional elections. The results of our study further reveal that independent respondents, who do not rely on a candidate’s party affiliation as a cue, show the greatest negative bias against female candidates among the subjects of our experiment. Moreover, Republican respondents lose their hostility toward female candidates when candidates can be differentiated by a party label, while Democratic respondents do not use candidate sex as a voting heuristic in any context. This finding suggests that partisanship works as a kind of “insurance” for Republican voters who can be confident that the party affiliation of the candidate will represent their views in office regardless of the sex of the candidate. This further implies that, while the particularly acute underrepresentation of women in the Republican Party may reflect selective decisions made by female candidates themselves for not running from this party, it could be partly driven by the biases that female candidates are likely to face in primary elections, where the party label is not a point of differentiation.

Candidate Sex and Voters’ Evaluation of Candidates

Previous studies suggest that voters make inferences based on a candidate’s sex (McDermott 1997). For instance, voters often presume that female candidates lack stereotypically masculine traits such as competence and strong leadership, traits that are often considered to be significant for elected officials to achieve success in politics (Alexander and Andersen 1993; Huddy and Terkildsen 1993b; Lawless 2004; Schneider and Bos 2014). Some studies argue that such gender stereotypes lead voters to favor male candidates over female candidates (Dolan et al. 2015; Lawless 2004). In contrast, others claim that gender stereotypes exert almost no influence on the evaluation of female candidates among voters (Anastasopoulos 2016; Brooks 2013) and that party and issue cues are weightier than gender stereotypes (Anderson et al. 2011; Dolan 2014a, b; Hayes 2011; Matland and King 2002; Thompson and Steckenrider 1997).

Female candidates are also assumed to be able to deal more effectively with “women’s issues,” such as those concerned with the environment, education, and healthcare, while male candidates are viewed to be well suited to deal with issues such as defense, crime, and the economy (Dolan 2010; Huddy and Terkildsen 1993b; Kahn 1994; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan 2009). Not only are male and female candidates thought to be interested in different policy areas, but they are also considered to have different stances on those issues. Voters appear to seek out information in a way that comports with stereotypes about the kinds of issues associated with male and female candidates (Ditonto et al. 2014). In addition, voters tend to think female candidates are more liberal and progressive than their male counterparts on various issues (Koch 2000; Sapiro 1981).

As important as these perceptions are, they are distinct from the direct effects of candidate sex that result from a voter’s underlying predisposition to vote for male or female candidates—a “baseline gender preference” (Sanbonmatsu 2002). While scholars generally agree that voters have certain gender stereotypes toward men and women running for public office, it remains an unsettled question whether candidate sex has an independent effect on voter evaluation. Failure to account for stereotypes and other candidate characteristics makes it ambiguous as to whether female candidates are disadvantaged compared to their male counterparts. We hope to resolve three key sources for this ambiguity.

First of all, if voters display a bias against female candidates, it might be because they dislike the idea of women in office per se (i.e., a “baseline gender preference” for male politicians) or because they associate female politicians with stereotypes such as passivity and a focus on issues such as health care that they value less than male-linked stereotypes such as strong leadership style and a focus on economic policy. Economists might describe this as a distinction between “taste-based” discrimination and “statistical” discrimination (see Guryan and Charles 2013). In addition, during electoral campaigns, voters receive other significant information about candidates, including characteristics such as party affiliation, policy positions, personal background, and polling results (Lau and Redlawsk 2006). Because voters often enter the campaign with ideological orientations, issue preferences, and attachments to particular parties, information about these attributes of candidates may play a more significant role than candidate sex in deciding their vote choice even if voters have certain stereotyped views toward men and women running for electoral office. This leads to a testable hypothesis that voters do not use candidate sex as a voting heuristic after accounting for stereotypes and other candidate characteristics.

Any “baseline gender preference” that exists within the population might vary across subgroups. The literature has paid particular attention to the difference between male and female voters to examine whether female voters support female candidates at higher rates than do male voters due to in-group favoritism originated from “gender affinity” (Dolan 2008; Rosenthal 1995; Sanbonmatsu 2002). The gender affinity effect has received mixed support in the literature. Some studies show that women do not necessarily vote for female candidates more than they do for male candidates (Ekstrand and Eckert 1981; Higgle et al. 1997; Lynch and Dolan 2014; Sapiro 1981) and that this effect is limited under the presence of policy issue cues (Anderson et al. 2011). Our study is able to resolve whether there is a baseline or taste-based preference for candidates of one sex or the other for both male and female voters.

Second, female candidates appear to face a greater challenge when they run for executive office than when they run for legislative office (Huddy and Terkildsen 1993a; Lawrence and Rose 2014; Rose 2013). The common explanation for the difference across offices also hinges on stereotypes in that voters may perceive male candidates are more likely to have characteristics such as strong leadership and to emphasize issues such as foreign policy that align well with expectations of presidents, while female candidates are more likely to be seen as compassionate and emphasizing domestic issues such as health care and education that are well-suited to being a legislator (Eagly and Karau 2002; Kahn 1996; Koch 2002; Sapiro 1981). This “gender-office congruency theory” thus generates a hypothesis that the use of candidate sex as a voting heuristic among voters does not vary across political offices being sought when we isolate the effect of candidate sex from stereotypes that voters associate with male and female politicians. A study by Kirkland and Coppock (forthcoming) also uses conjoint experiments and finds some evidence for voter bias against male candidates in an environment where voters are given less information, notably the absence of any partisan information. Further research is needed to understand how the office in question and richness of candidate information might shift gender bias back and forth from one setting to another.Footnote 2

The third question we address is the degree to which partisanship dominates other factors. Partisanship has been considered as the most important factor behind most voting decisions; in the contemporary polarized environment, party labels convey a lot of information and might leave little room for partisan voters to rely on candidate sex. We analogize that voting for a co-partisan provides a kind of “insurance” that essentially guarantees how a politician will act in office. This leads to a hypothesis that independents, who do not have any attachments to particular parties, are more likely to rely on candidate sex when they evaluate candidates.

But this effect may be limited to general elections where party labels differentiate candidates. Candidate sex is likely to operate differently in a primary where voters make choices between two competing candidates of the same party. For Democrats, candidate sex does not convey as a clear ideological signal; thus, the effect of candidate sex is expected to be marginal regardless of a candidate’s party label. In contrast, Republicans tend to view female candidates as more liberal than comparable male candidates, which might lead them to withdraw their support to female candidates unless a party signal differentiates the two competing candidates (see King and Matland 2003). This implies that both Democrats and Republicans do not rely on candidate sex when the party label is a point of differentiation, but that candidate sex has different effects when they choose a candidate from those running from the same party.

Research Design

It is challenging to isolate gender effects in observational data where female candidates might have been selected differentially during the recruitment process (Dolan and Sanbonmatsu 2011). The quality of emerging female candidates indeed differs significantly from their male counterparts (Anzia and Berry 2011; Fox and Lawless 2010; Lawless and Pearson 2008). Candidates are also strategic actors whose anticipation of the electorate’s response can shape their decisions (Schaffner 2007). Thus, an extensive amount of research has conducted survey experiments to understand the effect of candidate sex on voter decisions (e.g., Bauer 2015; Brooks 2013; Fridkin et al. 2009; Iyengar et al. 1996; Kahn 1994; Sanbonmatsu 2002; Sapiro 1981). These experimental studies contribute much to our understanding by intentionally manipulating candidate profiles and behavior. We build on these studies by varying more candidate attributes simultaneously and randomizing the order of those attributes.

We test the hypotheses laid out above using a conjoint survey experiment. Recently introduced to political science, conjoint experiments were widely used in marketing to assess the impact of many product characteristics. Unlike more familiar factorial designs, conjoint experiments vary all treatments simultaneously. For example, a traditional experiment interested in how the sex and race of a candidate affects voter decision making would randomly generate one of four types: white male, white female, black male, or black female. In contrast, a conjoint design would randomly generate either a male or female candidate and randomly generate the candidate’s race in a separate step. With only two characteristics, either approach might be fine. But when the number of characteristics grows, the traditional experiment requires more data than are usually available. For example, an experiment where candidates have ten characteristics (which are each dichotomous) would have 1024 types. If each of the characteristics has three values such as white, black, and Hispanics, there would be 59,049 types. An extremely large sample would be needed to populate all of those cells with a sufficient number of observations.

The conjoint design avoids this problem by varying each characteristic separately. This allows the researcher to assess the impacts of the independent and interactive effects of multiple variables on a common outcome metric without sacrificing much statistical power or imposing assumptions about functional forms of relationships (Hainmueller et al. 2014). This degree of power and flexibility is appealing in our application because it allows us to randomly vary many more candidate traits than have previous studies to better understand multidimensional decision-making by voters. This permits us not only to separate the baseline “taste-based” effect of candidate sex from the other characteristics such as gender stereotypes or partisanship that voters might infer in a “statistical” fashion, but also to assess simultaneously the relative importance of these factors on voter evaluation. Furthermore, the conjoint analysis also enables us to minimize the effect of social desirability bias and to elicit true attitudes toward female candidates by allowing respondents to justify any particular choice of candidates with multiple reasons.

In our experiment, we present each subject with a pair of opposing candidates whose profiles are randomly generated from the set of characteristics, and then ask him/her to choose between the two candidates. Although some studies give each subject only one candidate at a time to evaluate, presenting two opposing candidates is more realistic as it mimics the decision that voters must make on real ballots. We asked respondents which candidate they would vote for if it was an actual election, a familiar task for most of the electorate. The profiles of candidates are created in line with the existing literature on voter decisions as well as gender stereotypes more specifically (Lau and Redlawsk 2006; Lynch and Dolan 2014). We manipulate candidate attributes within four broad categories of information that a voter might encounter in a salient campaign: personal information, party information, issue information, and polling information.

First, to vary personal information that describes a candidate’s backgrounds and personality in the candidate profiles, we include a candidate’s sex, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, experience in public office, and salient personality trait. These attributes have been considered to play an important role when voters make decisions. For instance, scholars have paid extensive attention to the effect of a candidate’s race on voter decisions in expectation that black candidates are disadvantaged compared to white candidates. We are especially interested in personality traits because, in the absence of direct information, these are the stereotypes that voters are most likely to ascribe to male and female candidates. These perceptions rather than sex itself might drive voting choices. For example, the perceived competence and personality traits of candidates have been discussed as possible sources of disadvantage to women running for public office (Fridkin and Kenney 2011). Most importantly, as noted above, male candidates are often viewed to be more decisive and stronger leaders than female candidates. Hence, having experience in public office may help female candidates fend off criticism over the lack of competence toward them; and having personality traits that contradict their gender stereotypes may alleviate bias against female candidates. The personality traits of candidates are adopted from survey questions conducted by the American National Election Studies that routinely ask whether candidates provide strong leadership, are compassionate, are honest, are intelligent, are knowledgeable, and really care about people like you.

Second, many American voters have psychological attachments to one of the major political parties, making it natural to rely on party information about candidates. Some recent studies suggest that, even if voters hold gendered attitudes, they are still heavily influenced by a candidate’s party label rather than a candidate’s sex when they decide for whom to vote (Anderson et al. 2011; Dolan 2014a; Falk and Kenski 2006; Hayes 2011; Matland and King 2002). Hence, we include a candidate’s party label as an essential attribute to vary in the candidate profiles.Footnote 3 Importantly, by varying the party labels for both candidates, we are able to investigate the effects of candidate sex when the candidates are from opposing parties (as in a general election) and when they are from the same party (as in a primary election).

Third, the effect of candidate sex on voter decisions may be dampened when issue information such as a candidate’s policy positions and expertise is given to voters. Female candidates are often seen to have different policy priorities and preferences from their male counterparts (Swers 2002). The issue information attributes in the candidate profiles include a candidate’s positions on abortion, immigration, the federal budget deficit, and national defense. In addition, to distinguish positions from emphasis, we include the following six policy areas as varying attributes to describe the policy specialization of candidates: economic policy, foreign policy, public safety (crime), education, health care, and the environment.

Fourth, and finally, we vary polling information that describes a candidate’s popular support in the public. Voters have been known to rely on polling data as a sign of the relative desirability of candidates. Therefore, they may engage in strategic voting behavior by jumping on the bandwagon when one candidate is performing well in the polls. Voters with such incentives may pay attention to the public opinion when they evaluate candidates. The reported favorability rating of each candidate is randomly varied among five levels from relatively unpopular (34%) to highly popular (70%).Footnote 4

Table 1 summarizes all the attributes of candidate profiles used in our experiment. There is a total of 13 varying attributes. Some attributes take only two values, as in the case of partisanship (Democrat or Republican), whereas others take on several values, as in the case of polling favorability (five values ranging from 34 to 70%). For each profile, we randomly assign a value of each attribute. This research design yields 9,953,280 possible combinations of candidate profiles. Because the values of the candidate attributes are all randomly assigned, the use of a conjoint experiment rather than a factorial design makes it possible to estimate the effect of each attribute with a modest number of observations.Footnote 5

Our experiment asks respondents to review the profiles of two candidates that are randomly created from the set of attributes and then to choose between them.Footnote 6 This evaluation task is repeated ten times, with each pair of candidates displayed on a new screen. The categories of attributes of candidates such as age and experience in office are shown in randomized order across respondents so that the exercise does not inadvertently focus respondent attention on specific attributes.Footnote 7 Because so many attributes are varied, we think it is unlikely that respondents would be able to surmise the purpose of the experiment and behave strategically rather than simply choosing the candidate that seems most appealing.

Figure 1 presents an example of one set of congressional candidate profiles that was shown to a respondent in our experiment. The visual presentation mimics the one used by Hainmueller et al. (2014) and illustrates how attributes are varied across respondents.Footnote 8

In addition to varying attributes of the candidates, we also vary the office being sought to examine whether candidate sex has a different effect on voter decisions between presidential and congressional elections. Specifically, we split the ten pairs of candidates being evaluated into five sets of congressional candidates and five sets of presidential candidates, and ask respondents to evaluate candidates both for president and for Congress. The order of evaluation is randomly determined across respondents. Hence, approximately half respondents in our experiment first evaluated five pairs of candidates for president and then moved on to evaluating another five pairs of candidates for the House of Representatives; the remaining respondents evaluated the two groups in the reversed order.Footnote 9

Data and Method of Analysis

We collected data through an online survey experiment that was fielded in March 2016. The sample of voting-eligible adults in the United States was drawn by Survey Sampling International (SSI).Footnote 10 In collecting the data, we stratified the sample by the region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), sex (male and female), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian, and others), and age groups, based on the latest U.S. Census data. To be more specific, we first asked demographic screening questions to 3152 people in the SSI panel, and then invited 1733 respondents among them to our survey according to fixed quotas so that the total sample matches the adult U.S. Census population on age, sex, geographic region, and race/ethnicity.Footnote 11 In the survey, we also collected data of other personal information about respondents such as educational background, social class, partisanship, political interest, and ideological position. A total of 1583 respondents completed the conjoint experiment tasks in our survey (a completion rate of 91.3%). A detailed descriptive statistics on our sample are shown in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material. Because each of our respondents evaluated ten pairs of candidates, we have data from 31,660 profiles or 15,830 evaluated pairings. This is large enough to estimate the effect of each attribute in the candidate profiles.

The outcome variable of interest in this study is which candidate was chosen by a respondent. The choices are coded as a binary variable, where a value of one indicates that a respondent supported the candidate and zero otherwise. We analyze the data following the statistical approach developed in Hainmueller et al. (2014) to estimate non-parametrically what they define as the average marginal component effect (AMCE). To estimate the AMCE of each attribute on the probability that the candidate will be chosen, we employ the “cjoint” package (ver. 2.0.4) developed by Strezhnev et al. (2016). The standard errors are clustered by the respondent to account for the dependence of observations across respondents. In the following sections, we first present the average direct effect of a candidate’s sex on voter decisions, including separate examinations for presidential and congressional candidates to test for the gender-office congruency hypothesis. We then present the results that test for heterogeneous treatment effects by including the interactions between candidates’ attributes and respondents’ characteristics to reveal how bias against female candidates varies among different subpopulations within the electorate to test for the gender-affinity hypothesis. Finally, we explore differences by party to test whether party affiliation moderates any gender bias that exists in the full population.

Effects of Candidate Sex and Gender-Office Congruence

We begin with Fig. 2, which shows the relative importance of candidate attributes on electoral support for the full sample of respondents and candidate pairings. The dots denote point estimates for the AMCEs, which indicate the average effect of each attribute on the probability that the candidate will be chosen. The horizontal bars show 95% confidence intervals.Footnote 12 Our main interest here is the importance of candidate sex on voter decisions. Because each attribute is dichotomous, the estimated effects can be directly compared to one another. Note that within each category of attributes, one treatment is arbitrarily chosen as the omitted reference category, just as in a regression framework where one category serves as the baseline. For candidate sex, we set male as the baseline.

The results of our experiment show that candidate sex is a significant voting heuristic, even under the presence of many other cues about candidates. On average, respondents are 1.3 percentage points less likely to vote for a female candidate. Importantly, because of complete randomization of all attributes, this effect cannot be attributed to other factors such as age, experience, issue priorities, or even personality traits that might differ (in reality or perception) between male and female candidates in real elections. In other words, it seems that voters are biased against female candidates as a baseline preference and not just because of traits inferred in a “statistical” fashion when evaluating a female candidate. We show in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material that the effect is larger—2.5 percentage points—when the analysis is limited to opposite-sex pairings that include a male candidate and a female candidate. Relative to some other variables such as political experience and policy positions, the effect of candidate sex on voter decisions appears relatively small in magnitude. For instance, candidates with a 4-year experience in public office are 4.7 percentage points more likely to be selected than those without any political experience. Similarly, respondents are 4.1 percentage points more likely to vote for a 36-year old candidate than for a 76-year old candidate. These attributes have greater effects on vote choice than do a candidate’s sex. However, the magnitude of the gender effect is similar to the penalty faced by minority candidates and candidates with the lowest approval ratings and thus is likely to matter in a tight race where the winner is determined by a narrow margin.

As explained above, scholars have suggested that while women might be discriminated against in presidential elections, female candidates might face less bias or even be favored in congressional elections. Although the logic of how voters might connect perceived traits of male and female candidates with specific offices is intuitive, the gender-office congruency theory has not been fully tested. To provide some resolution to this question, our experiment presented half of the candidate pairs as seeking the presidency and half as seeking seats in the House of Representatives. Analyzing these two groups separately provides a clean test of this theory. Incidentally, it also provides a check on the verisimilitude of our experiment by revealing whether respondents are taking the task seriously enough to differentiate between offices.

Figure 3 shows the results of our analysis, which indicates the estimated marginal effect of candidate sex by the type of political office being sought. We find a clear and statistically significant difference between the two types of political office. The overall effect of 1.3 points disadvantage presented earlier was an average that masked this difference by office. Our respondents indeed punish female candidates by 2.4 percentage points (p = .003) in presidential elections, while there is no female disadvantage in congressional elections (p = .894). The confidence intervals in Fig. 3 appear to overlap, but the difference between the two kinds of elections (2.3 percentage points) is nonetheless statistically significant (p = .046).

Marginal effect of candidate sex on voting decision by office type. Note Plots show the estimated effects of the randomly assigned candidate sex (female) on the probability of being supported by voters, conditional on the assumed level of office. The horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the point estimates

This finding suggests that female candidates face a greater challenge when they run for executive office than when they run for legislative office; this is true even after controlling for stereotypes that voters associate with male and female politicians. As a result, the standard gender-office congruency theory does not fully explain why voters have a bias against women being elected as president.Footnote 13 For example, because we randomly varied personal characteristics and experience in office, it is not the case that respondents preferred male candidates in the hypothetical presidential election because they inferred that the men were stronger leaders or more experienced. An additional explanation may be that the public simply has more experience with women in Congress, including even the former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. In contrast, the public must use imagination to anticipate what a female president would do in office (Burden et al. 2017). Research on the first election of black candidates finds that white voters are initially resistant because of the uncertainty and lack of experience with black elected officials (Hajnal 2003). It is plausible that the difference between presidential and congressional elections may be because having no experience of a female president brought some fears and uncertainties to voters about choosing a female candidate in presidential elections.

We further show in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material that this result is not necessarily driven by people’s attitudes toward Hillary Clinton, who was running for the Democratic presidential nomination at the time when our survey was conducted. It is difficult to test for whether attitudes toward Clinton underlie views about a female president because those who have bias against a female president are prone to dislike Clinton as well. However, as we show in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material, there is little evidence for a “Hillary effect” in our data. Even among those who do not have a negative favorability rating toward Clinton, we still found a tendency that people have a greater bias against female candidates in presidential elections than they do in congressional elections.

Effects of Candidate Sex by Subgroups of Respondents

We have so far analyzed the overall effect of candidate sex on voter decisions. While we found a modest negative bias against female candidates, not all voters are likely to punish female candidates in the same manner. To examine the heterogeneity of treatment effects, Fig. 4 compares the estimated marginal effects of candidate sex on voter decisions for several subgroups of respondents. This figure shows how the disadvantage of a female candidate varies across the respondent’s characteristics such as sex, education level, age, social class, region of residence, race/ethnicity, and partisanship.Footnote 14 The negative values of estimates imply that respondents punish female candidates. (The effects for male candidates are simply the opposite to those shown in the figure.)

Marginal effects of candidate sex on voting decision by respondent attributes. Note Plots show the estimated effects of the randomly assigned candidate sex (female) on the probability of being supported by voters, conditional on voter attributes. The horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the point estimates

Although treatment effects do not actually differ much across respondent attributes, we do uncover some differences across levels of self-identified social class. Whereas respondents who identify themselves as lower class tend to punish female candidates, those who identify themselves as upper class do not have any bias against female candidates. Differences by race and ethnicity, region, and age are modest to nonexistent. Our results further indicate that female respondents do not vote disproportionately for female candidates at higher rates when other candidate attributes are varied. Instead, the results show that male respondents prefer male candidates over female candidates. In short, we find no evidence for the gender affinity effect in the form that is often believed to exist among female respondents, but we do find evidence for an opposite affinity among male respondents.Footnote 15

A more dramatic pattern emerges across respondents depending on party identification.Footnote 16 While Republicans have a negative bias against female candidates of about two percentage points, Democrats do not punish female candidates.Footnote 17 This is not especially surprising given the preponderance of women who identify as Democrats and serve as Democrats in elective office, although we find that it holds even when other characteristics of the candidate such as policy positions are held constant via randomization.Footnote 18 What may be more surprising is that independents exhibit a larger negative bias against female candidates than do Republicans.Footnote 19 The probability that independents support a candidate is 3.2 percentage points lower if that candidate is woman.Footnote 20

This result is consistent with our hypothesis. We conjecture that among voters with partisan affiliations, partisanship acts as a strong force that leaves relatively little room for candidate sex to affect the voting decision. Partisanship is in fact a better diagnostic for how election officials will behave in office than perhaps any other characteristic, so partisan voters rationally focus on that dimension over candidate sex. Independents, in contrast, lack a predisposition to favor one of the candidates based on party. Without a clear indicator that one of the candidates will act as a faithful agent of their independent voter’s interests in office, their bias against female candidates is more readily apparent. In short, partisan labels provide a kind of “insurance” for partisans that guards against the uncertainty that a different kind of officeholder might bring. A candidate’s party brings a high level of predictability that allows partisan voters to discount other information. Independents, who lack the security provided by a party affiliation, end up relying more on other factors including candidate sex.

Interestingly, this result conflicts with what respondents say when asked about candidate sex in isolation. For example, a survey conducted in November 2014 asked respondents whether they hoped to see a female elected president in their lifetimes or whether it did not matter to them. A majority of Democrats said they hoped this would happen, and more than one-third of independents did, but fewer than one in five Republicans did.Footnote 21 This suggests that Republicans would be most likely to harbor bias against female candidates, or Democrats to harbor bias in favor of them, but this only appears to be true in the abstract when other factors about candidates are absent. Our conjoint experiment shows that in the context of making a decision between two candidates with realistic profiles, candidate sex actually matters most to independents because partisanship does not provide them with a reason in itself to override it. For a voter who identifies with a party, choosing a candidate of the same party provides some “insurance” about what the official would do in office regardless of their sex.

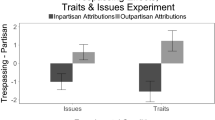

To explore partisan differences further, Fig. 5 presents the estimated marginal effects of candidate sex separately for the two electoral contexts—competitions between different-party candidate pairings (Democratic vs. Republican candidates) and competitions between same-party candidate pairings (Democratic vs. Democratic candidates or Republican vs. Republican candidates). These two scenarios mimic the options that voters actually face in general elections and primary elections, respectively. We argue that independents display the greatest response to candidate sex because a candidate’s party label cannot work for them to ensure that their views are reflected in politics. If this is the case, the effect of candidate sex on voter decisions should be more determinative among partisan voters (especially among Republicans) in the context of electoral competition where the party label is not a point of differentiation.

Marginal effects of candidate sex by respondent party identification. Note Plots show the estimated effects of candidate sex on the probability of being preferred to vote in elections. They are separately estimated by the same-party pairings and different party pairings for the group of respondents who are Democrats, Republicans, and Independents, respectively. The horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the point estimates

The results shown in Fig. 5 are consistent with our expectations. When electoral competition is between two candidates from different parties, neither Democrats nor Republicans show hostility toward female candidates (i.e., the estimated marginal effect of candidate sex for each group is not statistically discernible from zero). In contrast, when electoral competition is between the two candidates running from the same party, Republicans show biases against female candidates of 2.8 percentage points, while Democrats remain to have no bias against female candidates.Footnote 22 Independents are different from partisans: they show a preference for male candidates to female candidates in both cases. These findings suggest that candidate sex does not matter among Democrats regardless of the electoral context; candidate sex becomes more important for Republicans when candidates cannot be differentiated by a party label; and candidate sex always affects their vote choice among independents. In other words, partisanship helps Republicans override the bias based on candidate sex. This implies that candidate sex is likely to play a more important role for partisan voters (especially Republicans) in evaluating candidates in primary elections or in nonpartisan elections where the party label—so consequential in general elections—is not a point of differentiation.

In summary, the results of our conjoint experiment demonstrate that voters use candidate sex as a voting heuristic even when it is embedded among various other cues about candidates. At the same time, the overall effect of candidate sex on voter decisions is relatively small compared to other candidate attributes such as issue positions and public office experience, and its magnitude is almost the same as the effect of candidate race/ethnicity. In addition, punishment of female candidates is limited to presidential rather than congressional elections, and appears only among male voters. More importantly, the results further show that the effect of candidate sex varies significantly among voters across party lines, and in particular, that independent rather than Republican voters showing the greatest negative bias against female candidates. We attribute this to the “insurance” that a party label provides to partisan voters and argue that the lack of such relevant information for independents allows their bias against female candidates to emerge. Republicans display bias in nonpartisan elections but appear to overcome the bias when they can differentiate candidates based on the party label.

Conclusion

Even though a majority of the population and of voters in the United States is female, women are sorely underrepresented in Congress and a woman has yet to be elected president. A complete explanation for the underrepresentation of women in elective office is necessarily complex and multifaceted, yet its elements are gradually coming to fruition. In particular, recent research has shown that part of the explanation is that potential female candidates are less likely to view themselves as qualified, are less willing to endure the demands of campaigning, and are less likely to be recruited than are men in similar circumstances (Kanthak and Woon 2015; Lawless 2012; Lawless and Fox 2005; Sanbonmatsu 2006).

Previous studies have demonstrated that voters view candidates from gendered perspectives. This in itself could lead to the gender inequality in elected office. However, the scholarly literature has not made clear whether voters actually use candidate sex as a heuristic. This is partly because various other cues about candidates—such as candidate’s party label and even policy positions—are also available to voters. These other cues may overwhelm the effect of candidate sex on voter decisions, particularly in the contemporary era as public resistance to women in public life has declined and party cues have become so powerful.

The design of our study allows for new insight on this aspect of women’s representation. It is difficult to evaluate the effect of candidate sex on vote decisions by using actual election results due to the presence of endogeneity problems such as entrance barriers for female candidates. Hence, multiple prior studies have conducted experiments to determine whether a candidate’s sex has a direct effect on voting decisions among people by manipulating candidate profiles in campaign advertisements and newspaper articles to make firmer causal inferences. However, those studies test the effects of multiple candidate attributes in separate experiments rather than simultaneously, and the number of varying candidate attributes in each experiment is quite limited. Omitting potentially relevant characteristics is a concern because voters have been shown to infer things about candidates based on their sex. Because the conventional experimental designs cannot fully decompose multiple treatment effects and rule out these inferential mechanisms, we instead employed a conjoint survey experiment. This design enables us to examine the relative importance of candidate sex on vote decisions by randomly varying a large number of candidate attributes in profiles to rule out endogenous effects, spurious effects, and mechanisms that are distinct from a baseline gender preference.

The results of our study demonstrate that a candidate’s sex affects voter decisions even under the presence of many other information cues about candidates. The respondents in our experiment pay attention not only to a candidate’s party label and issue positions, but also to the candidate’s sex. However, the overall magnitude of the bias against female candidates is relatively small compared to other candidate attributes such as issue positions and public office experience, and its magnitude is almost the same as the effect of candidate race/ethnicity. Moreover, the bias does not occur because women disproportionately support female candidates; rather, the gender-based affinity effect is found only among male respondents who prefer male candidates to female candidates. The effect of candidate sex also differs between presidential and congressional elections. However, in an apparently challenge to the gender-office congruency theory, we found that female candidates running for presidential elections face a greater challenge than those running for congressional elections even after isolating the effect of candidate sex as distinct from stereotypes that voters associate with male and female politicians. Thus, the role of gender stereotypes among voters cannot fully explain the difference between the levels of office that candidates are seeking.

Most importantly, our results further showed that the effect of a candidate’s sex varies significantly among respondents across party lines, and in particular, that independent rather than Republican respondents show the greatest negative bias against female candidates. We attribute this to the “insurance” that a party label provides to partisan voters, who can be sure that the party affiliation of the candidate will represent their views in office regardless of the sex of the candidate, and argue that the lack of such relevant information for independents allows their bias against female candidates to emerge. Republicans override their bias against female candidates when they can differentiate candidates based on the party label. In contrast, independents have no such insurance, and always react more immediately to candidate sex.

Our findings point to at least three intriguing paths for further research about conditions where candidate sex might operate different. The first path is to explore election environments where candidate information is less rich. The importance of candidate sex as an informational cue may be different depending on the types of other candidate attributes shown to voters. Indeed, the information cues available to voters differ depending on the context of electoral campaign. The sex of a candidate is usually easy to discern from advertising or from the names listed on the ballot, but policy information might be more elusive, particularly in lower level elections where knowledge about candidates is thinner. In addition, there is also a possibility that exposure to candidate attributes related to gender stereotypes activates voters showing a bias against female candidates (see Bauer 2015). As a future extension, we need to systematically examine how the effect of candidate sex changes with variation in the information environment.

The second path to explore is how candidate sex interacts with other candidate characteristics. Exploring these combinations could reveal the importance of “intersectional” candidate profiles such as the differences between female candidates who are black and those who are white. In exploratory analysis of such interactions, we detected an interesting interaction between candidate sex and the candidate’s position on national security. At least in the congressional election scenario, women who took the “strong national defense” position were disadvantaged relative to those who took the stereotypic position of reducing the defense budget. This suggests that the effect of candidate sex could vary across time and other contexts as other considerations rise and fall in prominence, for example, as national security becomes more or less salient. Future studies might even ask respondents about the “most important problem” in the election to assess how that conditions the bias for or against female candidates.

The third path is about how voter experiences with female elected officials might themselves change attitudes over time. The number of female representatives is increasing in Congress, especially on the Democratic side of the aisle. Voters often rely on stereotypes in evaluating unfamiliar candidates due to fear and uncertainty associated with them, but those uncertainties tend to dissipate as voters experience more members of underrepresented groups in elective office. Thus, the experience of having female representatives in Congress may have reduced the bias against female candidates among Democrats. Moreover, the presence of female president may change how voters evaluate female candidates in presidential elections afterwards. Researchers might test this possibility by examining whether female candidates are evaluated differently between voters who have any incumbent female representatives before and those who do not have such an experience.

Notes

We generally use the term sex rather than gender, although we note that it is unclear which is the more accurate way to describe how candidates present themselves and how voters perceive those presentations. Our experiments follow popular usage by describing candidates dichotomously as either male or female and do not explore the subtleties of gendered factors such as visual presentation by candidates.

The Kirkland and Coppock (forthcoming) study differs from ours in two important ways. First, the authors compare elections with and without party labels, but do not examine elections where both candidates are from the same party. Second, their experiment does not tell respondents what office is being sought. Instead, the experiment varies the previous office held by the candidate, ranging from local offices such as city council to representative in Congress. It is possible that respondents infer what office is being sought by the backgrounds that are presented to them in each candidate pairing.

It is important to control for policy positions as well as party labels in our conjoint experiment. We believe party affiliation, at least in the contemporary era, is a broader indicator to a voter about how a politician will act in office. In Congress, for instance, politicians often have to follow party leadership by giving up their own policy goals. Thus, it is likely that partisan voters still rely on a candidate’s party label independently from cues about his or her policy positions.

These values are spaced nine percentage points apart to create a total of five levels of ratings (34, 43, 52, 61, and 70%) that keep a constant interval.

The exact formulas used to estimate the effect of each attribute are explained in Hainmueller et al. (2014).

There might be a concern that conjoint experiments, which ask respondents to choose from multiple hypothetical descriptions of objects, produce biased outcomes due to the failure to accurately capture real-world decision-making. However, a study by Hainmueller et al. (2015) validated conjoint experiments against real-world behavior by employing the case of referendums in Switzerland as the behavioral benchmark. According to their study, the results of conjoint experiments closely correspond to the choices made by people under real-world conditions. Thus, we have reason to believe that our findings translate reasonably well to the real world. In addition, as we have shown in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material, we found no evidence to suggest that our respondents made artificial judgments when they were exposed to candidate pairs with less plausible profile combinations.

The order is fixed across ten pairs for each respondent to minimize his or her cognitive burden.

This design creates some combinations of candidate attributes that would be rare in real elections. For instance, voters seldom encounter a candidate who is female, black, Republican, pro-choice, and who wants to increase taxes. Such implausible combinations may introduce some biases to the results by leading our subjects to make artificial judgments without much cognitive effort (Auspurg et al. 2009). However, as we show in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material, the likelihood of having implausible combinations is limited, and the results remain almost the same even after excluding those combinations. We address this issue at greater length in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material using response timers to assess whether respondents take the experiment less seriously when candidates’ policy positions seem incongruent with their party affiliations.

We randomize the order of evaluation in this way to mitigate the concern that respondents may change their behavior when they evaluate the latter five pairs of candidates.

Some might be concerned that actual voters may differ from the overall adult population. While our survey does not directly ask respondents whether they have cast a ballot in the general election, we have a measure of their political interest. Turnout and political interest are indeed highly correlated. According to data from the 2012 ANES, 92% of people who are very interested in politics report they voted in the election; in contrast, only 37% of people with no political interest report voting. However, we find that the bias against female candidates does not vary across respondents with different levels of political interest (see the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material for more details).

It is possible that voters are biased against female candidates only when it comes to the presidency and not for other executive offices such as governor and mayor. Additional experiments will be necessary to pursue these nuances of the gender-office congruency theory.

The exact questions used to measure the characteristics of our respondents are reported in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material.

Note that we cannot rule out the possibility that the effects for male and female respondents are themselves not statistically significant from one another (p > .10).

We measure party identification using the first of the standard branching questions. That is, “leaners” are not distinguished from other independents. However, we also have a measure of attitude toward each party. Our data suggest that 41.2% of those who identified themselves as independents are truly neutral to both parties; the rest of the self-identified independents (59.8%) have an attitude leaning toward either party, but the tilt is often slight and they are almost equally split between the two parties (28.9% for Republicans and 29.9% for Democrats). We discuss more details about the distribution of leaners among independents in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material.

The AMCE for Democrats is positive (pro-female) but not statistically significant, suggesting that candidate sex has no effect on their candidate evaluation among Democrats.

The negative bias against female candidates found among Republicans is not simply because they have imagined Hillary Clinton when they heard of female president. As we have shown in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material, we found that disfavoring Clinton does not lead respondents (including Republicans) to show a greater bias against a female president. In addition, the results of a list experiment designed to minimize social desirability bias shows that Republicans still exhibit a much greater bias against female president than other respondents do even after controlling for the “Hillary Effect” (Burden et al. 2017).

The estimated effect for independents is 1.2 points larger than for Republicans, but the difference between them is not statistically significant (p > .10).

Among independents, both men and women exhibit bias against female candidates. In contrast, among Democrats, neither men nor women exhibit bias against female candidates; and among Republicans, only men exhibit bias against female candidates. More details about the results for subgroups defined by a respondent’s partisanship crossed with sex are shown in the Appendix in Electronic Supplementary Material.

Pew Research Center (2017).

Democrats actually favor female candidates by 1.2 percentage points, but this estimated effect is not statistically significant at the .10 level.

References

Alexander, D., & Andersen, K. (1993). Gender as a factor in the attribution of leadership traits. Political Research Quarterly, 46(3), 527–545.

Anastasopoulos, L. (2016). Estimating the gender penalty in house of representatives elections using a regression discontinuity design. Electoral Studies, 43, 150–157.

Anderson, M. R., Lewis, C. J., & Baird, C. L. (2011). Punishment or reward? An experiment on the effects of sex and gender issues on candidate choice. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 32(2), 136–157.

Anzia, S. F., & Berry, C. R. (2011). The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson effect: Why do congresswomen outperform Congressmen? American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 478–493.

Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., & Liebig, S. (2009). Complaxity, learning effects, and plausibility of vignettes in factorial surveys. Unpublished manisucript. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-150806.

Bauer, N. M. (2015). Emotional, sensitive, and unfit for office? Gender stereotype activation and support female candidates. Political Psychology, 36(6), 691–708.

Bauer, N. M. (2017). The effects of countersterotypic gender strategies on candidate evaluations. Political Psychology, 38(2), 279–295.

Berinsky, A. J., Margolis, M. F., & Sances, M. W. (2014). Separating the shirkers from the workers? Making sure respondents pay attention on self-administered surveys. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 739–753.

Brooks, D. J. (2013). He runs, she runs: Why gender stereotypes do not harm women candidates. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 496–515.

Burden, B. C., Ono, Y., & Yamada, M. (2017). Reassessing public support for a female president. Journal of Politics, 79(3), 1073–1078.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Ditonto, T. M., Hamilton, A. J., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2014). Gender stereotypes, information search, and voting behavior in political campaigns. Political Behavior, 36(2), 335–358.

Dolan, K. (2008). Is there a ‘gender affinity effect’ in american politics? Political Research Quarterly, 61(1), 79–89.

Dolan, K. (2010). The impact of gender stereotyped evaluations on support for women candidates. Political Behavior, 32(1), 69–88.

Dolan, K., & Sanbonmatsu, K. (2011). Candidate gender and experimental political science. In J. N. Druckman, D. P. Green, J. H. Kuklinski & A. Lupia (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of experimental political science (pp. 289–298). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dolan, K. (2014a). Gender stereotypes, candidate evaluations, and voting for women candidates: What really matters? Political Research Quarterly, 67(1), 96–107.

Dolan, K. (2014b). When does gender matter? Women candidates and gender stereotypes in American elections. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dolan, J., Deckman, M., & Swers, M. (2015). Women and politics: Paths to power and political influence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598.

Ekstrand, L., & Eckert, W. A. (1981). The impact of candidate’s sex on voter choice. Western Political Quarterly, 34(1), 78–87.

Falk, E., & Kenski, K. (2006). Issue saliency and gender stereotypes: Support for women as presidents in times of war and terrorism. Social Science Quarterly, 87(1), 1–18.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2010). If only they’d ask: Gender, recruitment, and political ambition. Journal of Politics, 72(2), 310.

Fridkin, K. L., & Kenney, P. J. (2011). The role of candidate traits in campaigns. Journal of Politics, 73(1), 61–73.

Fridkin, K. L., Kenney, P. J., & Woodall, G. S. (2009). Bad for men, better for women: The impact of stereotypes during negative campaigns. Political Behavior, 31(1), 53–77.

Guryan, J., & Charles, K. K. (2013). Taste-based or statistical discrimination: The economics of discrimination returns to its roots. The Economic Journal, 123(November), F41–F432.

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(8), 2395–2400.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30.

Hajnal, Z. L. (2003). Uncertainty, experience with black representation, and the White vote. In B. C. Burden (Ed.), Uncertainty in American politics (pp. 213–243). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hayes, D. (2011). When gender and party collide: Stereotyping in candidate trait attribution. Politics & Gender, 7(2), 133–165.

Higgle, E. D. B., Miller, P. M., Shields, T. G., & Johnson, M. M. S. (1997). Gender stereotypes and decision context in the evaluation of political candidates. Women & Politics, 17(3), 69–88.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993a). The consequences of gender stereotypes for women candidates at different levels and types of office. Political Research Quarterly, 46(3), 503–525.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993b). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 119–147.

Iyengar, S., Valentino, N. A., Ansolabehere, S., & Simon, A. F. (1996). Running as a woman: Gender stereotyping in women’s campaigns. In P. Norris (Ed.), Women, media, and politics (pp. 77–98). New York: Oxford University Press.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Kahn, K. F. (1994). Does gender make a difference? An experimental examination of sex stereotypes and press patterns in statewide campaigns. American Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 162–195.

Kahn, K. F. (1996). The political consequences of being a woman: How stereotypes influence the conduct and consequences of political campaigns. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kam, C. D. (2012). Risk attitudes and political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 817–836.

Kanthak, K., & Woon, J. (2015). Women don’t run? Election aversion and candidate entry. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 595–612.

King, D. C., & Matland, R. E. (2003). Sex and the grand old party: An experimental investigation of the effect of candidate sex on support for a Republican candidate. American Politics Research, 31(6), 595–612.

Kirkland, P. A., & Coppock, A. (forthcoming). Candiate choice without party labels: New insights from conjoint survey experiments. Political Behavior.

Koch, J. W. (2000). Do citizens apply gender stereotypes to infer candidates’ ideological orientations? Journal of Politics, 62(2), 414–429.

Koch, J. W. (2002). Gender stereotypes and citizens’ impressions of house candidates’ ideological orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 453–462.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing in election campaigns. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Politics of presence? Congresswomen and symbolic representation. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 81–99.

Lawless, J. L., & Fox, R. L. (2005). It takes a candidate: Why women don’t run for office. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, J. L., & Pearson, K. (2008). The primary reason for women’s underrepresentation? Reevaluating the conventional wisdom. Journal of Politics, 70(1), 67–82.

Lawless, J. L. (2012). Becoming a candidate: Political ambition and the decision to run for office. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lawrence, R. G., & Rose, M. (2014). The race for the presidency: Hillary Rodham Clington. In S. Thomas & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Women and elective office (pp. 67–79). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know?. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lynch, T. R., & Dolan, K. (2014). Voter attitudes, behaviors, and women candidates. In S. Thomas & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Women and elective office (pp. 46–66). New York: Oxford University Press.

Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., & Mo, C. H. (2013). Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: Distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 391–410.

Matland, R., & King, D. (2002). Women as candidates in congressional elections. In C. S. Rosenthal (Ed.), Women transforming Congress (pp. 119–145). Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

McDermott, M. L. (1997). Voting cues in low-information elections: Candidate gender as a social information variable in contemporary United States elections. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 270–283.

Pew Research Center. (2017). American’s views of women as political leaders differ by gender. Retrieved April 25, 2018, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/05/19/americans-views-of-women-as-political-leaders-differ-by-gender/.

Popkin, S. L. (1991). The reasoning voter: Communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about pollitical candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 472–496.

Rose, M. (2013). Women & executive office: Pathways & performance. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Rosenthal, C. S. (1995). The role of gender in representation descriptive representation. Political Research Quarterly, 48(3), 599–611.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 20–34.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2006). Where women run: Gender and party in the American States. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Sanbonmatsu, K., & Dolan, K. (2009). Do gender stereotypes transcend party? Political Research Quarterly, 62(3), 485–494.

Sapiro, V. (1981). If U.S. Senator Baker were a woman: An experimental study of candidate images. Political Psychology, 3(1/2), 61–83.

Schaffner, B. F. (2007). Priming gender: Campaigning on women’s issues in U.S. Senate Elections. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 803–817.

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology, 35(2), 245–266.

Strezhnev, A., Berwick, E., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2016). Package “Cjoint” version 2.0.4.

Swers, M. L. (2002). The difference women make: The policy impact of women in Congress. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thompson, S., & Steckenrider, J. (1997). The relative irrelevance of candidate sex. Women & Politics, 17(4), 71–92.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael DeCrescenzo, Sarah Khan, Spencer Piston, Eleanor Neff Powell, David P. Redlawsk, and seminar participants at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Boston University, the University of Chicago, Dartmouth College, and Keio University for their helpful comments on this research. We also appreciate Yusaku Horiuchi for sharing his R scripts, and Masahiro Yamada and Masahiro Zenkyo for their assistance in data collection. Earlier versions of this work were presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association and the Annual Meeting of the Society for Political Methodology. This research was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (26285036; 26780078; 17K03523) and the Kwansei Gakuin University Research Grant. Yoshikuni Ono also received the JSPS postdoctoral fellowship for research abroad. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numeral results in the paper are available in the Political Behavior Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IZKZET).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ono, Y., Burden, B.C. The Contingent Effects of Candidate Sex on Voter Choice. Polit Behav 41, 583–607 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9464-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9464-6