Abstract

In 2009, women are still dramatically underrepresented in elected office in the United States. Though the reasons for this are complex, public attitudes toward this situation are no doubt of importance. While a number of scholars have demonstrated that women candidates do not suffer at the ballot box because of their sex, we should not assume that this means that voter attitudes about gender are irrelevant to politics. Indeed, individual attitudes towards women’s representation in government and a desire for greater descriptive representation of women may shape attitudes and behaviors in situations when people are faced with a woman candidate. This project provides a more complete understanding of the determinants of the public’s desire (or lack thereof) to see more women in elective office and support them in different circumstances. The primary mechanism proposed to explain these attitudes is gender stereotypes. Gender stereotypes about the abilities and traits of political women and men are clear and well documented and could easily serve to shape an individual’s evaluations about the appropriate level and place for women in office. Drawing on an original survey of 1039 U.S. adults, and evaluating both issue and trait stereotypes, I demonstrate the ways in which sex stereotypes do and do not influence public willingness to support women in various electoral situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Notwithstanding recent successes in women’s election to office at most levels in the U.S., the reality is that women are still dramatically underrepresented in American government and politics. Despite the avalanche of attention to the candidacies of Senator Hillary Clinton and Governor Sarah Palin, the election of 2008 continued the pattern of incremental increases in women’s representation in Congress, state legislatures, and statewide office (Center for American Women and Politics 2009). Since several elements of the 2008 election demonstrated that issues surrounding candidate sex and gender considerations are still of central importance in American politics, attention to their impact on women’s underrepresentation is still necessary.

To date, scholarly research on women’s underrepresentation has demonstrated that this situation cannot be explained by poor candidate quality (Fulton et al. 2006; Lawless and Fox 2005), inadequate campaign resources (Burrell 2008), or overt voter bias against women (Dolan 2004). Instead, recent works have highlighted the importance of institutional influences (Lawless and Pearson 2008; Palmer and Simon 2006), political party recruitment efforts (Burrell 2008; Sanbonmatsu 2006), and the number of women willing to stand for election as candidates (Lawless and Fox 2005). One area that has received less attention, however, is public opinion toward the question of women’s representation in elected office. While a number of scholars have demonstrated that women candidates do not suffer disproportionally at the ballot box because of their sex, we should not assume that this means that voter attitudes about gender are irrelevant to politics. Indeed, individual attitudes towards women’s representation in government and a desire for greater descriptive representation of women may shape specific vote choice decisions that people make when faced with a woman candidate. For example, a voter who values greater representation of women in government may be moved to support a woman candidate in a race against a man. At the same time, these attitudes can have an impact beyond vote choice, influencing individual decisions to donate money to candidates or organizations that seek to increase the number of women in office, volunteer in campaigns, or simply try to convince others to support a particular candidate. Conversely, people who do not place a high value on increasing women’s representation or who hold negative feelings towards such an increase may seek to support male candidates with their time, money, and vote.

This project provides a more complete understanding of the determinants of the public’s desire (or lack thereof) to see more women in elective office and support them in different circumstances. The primary mechanism proposed to explain these attitudes is gender stereotypes. Gender stereotypes about the abilities and traits of political women and men are clear and well documented and could easily serve to shape an individual’s evaluations about the appropriate level and place for women in office. In much the way that general gender stereotypes might shape personal preferences when choosing an accountant or child care provider, this work hypothesizes that political gender stereotypes shape people’s desire for a greater or lesser role for women in elective office. However, much of the work on gender stereotypes has focused on more identifying the different kinds of stereotypes people hold about women and men in politics, which means that we know somewhat less about the influence of stereotypes on political attitudes and behaviors. This project will contribute to our understanding of the importance and potential impact of gender stereotypes by examining whether and how they shape people’s support for women candidates in various electoral circumstances.

Gender Stereotypes and Public Attitudes

The main hypothesis examined here is that people who perceive women as possessing the appropriate policy competence and personality characteristics expected of successful leaders will be more likely than others to support a greater role for women in elective office. At the same time, those who see men as more well-suited for office will be less likely to support women candidates and the idea of more women in office. The literature on the presence of gender stereotypes in public evaluations of women and men in office is clear. Numerous experiments and surveys indicate that voters believe female politicians are warmer and more compassionate, better able to handle education, family, and women’s issues, and are more liberal, Democratic, and feminist than men (Alexander and Andersen 1993; Burrell 1994; Huddy and Terkildsen 1993a; Kahn 1996; Koch 1999). Male politicians are seen as strong and intelligent, best able to handle crime, defense, and foreign policy issues, and more conservative (Lawless 2004). Recent work demonstrates the role that stereotypes can play in shaping voting behavior, primarily through the positive or negative feeling voters have about the characteristics and traits they see certain kinds of candidates possessing (Dolan 2004; Kahn 1996; Lawless 2004; Sanbonmatsu 2002). For example, voters who value honesty and ethics in government are more likely to vote for a woman running against a man, while people most concerned about foreign policy issues are more likely to support a man over a woman (Dolan 2004; Lawless 2004).

The research reported here extends our understanding of the link between gender stereotypes and attitudes toward women’s representation in office in three specific ways. In doing so, this research expands the situations in which we consider the impact of stereotypes on attitudes toward women candidates and women in office more generally, focusing both on how stereotypes might operate to shape support for women in specific electoral situations and for a more general support for greater descriptive representation of women. First, I examine whether and how stereotypes are related to an individual’s baseline preference for supporting candidates of a particular sex in a head to head matchup between a woman and a man. Voting for a woman candidate is a clear and direct way to try to increase the number of women in office and people with clear preferences for women’s descriptive representation may be more likely to use candidate sex as a cue when making their voting choice. The expectation here is that people with more positive stereotypes about women will be more likely to have a baseline preference for women candidates over men. Previous research has shown that many voters do in fact prefer to support candidates of one sex or the other, with most work finding that women voters are more likely to have a baseline preference and that their preference is for women candidates (Rosenthal 1995; Sanbonmatsu 2002). Sanbonmatsu (2002) also finds a role for the influence of stereotypes, demonstrating that people who believed that men were more well suited to politics and stronger on important issues (crime, foreign affairs) were more likely to express a baseline preference for men. However, in her analysis, gender stereotypes were less useful in predicting a preference for women candidates.

A second hypothesis considers whether stereotypes about women are related to a more general desire for greater gender balance in government. At their most basic, stereotypes tell us whether people see candidates with certain characteristics to be capable of governing or not. Those who see women as possessing the requisite abilities (for example, skill in handling a broad set of issues, compassion, competence) will no doubt be more likely to want more women in office than those who hold them in a more negative light. Given the centrality of gender stereotypes to people’s evaluations of women and men in politics, I expect that those who hold more positive issue and trait stereotypes about women will be more likely to want higher levels of women in office and those who hold more negative stereotypes will favor more male dominated government.

Illustrative of this connection is polling data that asks Americans whether they think the United States would be governed better or worse with more women in elective office. People who saw more women in government as a benefit to the country did so because they evaluated women as more conscientious and less corrupt than men and more likely to exercise fiscal responsibility and broad concern for all people. Those who saw more women in government as a negative articulated a view of women as too weak, too inconsistent, and not possessing the economic and financial competence required of leaders (Simmons 2001).

Finally, I consider how the impact of stereotypes on attitudes towards supporting women candidates might be mediated by political party. Here I hypothesize that people with more positive stereotypes will be more likely to support a woman candidate when she is a Democrat than when she is a Republican. This hypothesis is motivated by work that suggests that voter attitudes and behaviors toward women candidates are shaped, in part, by the party affiliation of these women. For example, some research suggests that Republican women candidates have a harder time attracting votes from their own party than do Democrats (King and Matland 2003; Lawless and Pearson 2008), while other work finds that people’s stereotype evaluations are shaped by a woman candidate’s party (Koch 2002; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan 2009). Dolan (2004) suggests that this is because issue and trait stereotypes of women and of Democrats are generally consistent with each other, while stereotypes of women and of Republicans are more at odds with each other. This, combined with the more traditional gender ideology of the Republican party, can result in Republican women facing more challenging electoral situations than do Democratic women. Given that there is such an imbalance in the party affiliation of women in elected office in the U.S. (for example, 77% of the women in the 111th Congress and 71% of women state legislators serving in 2009 are Democrats), considering whether people’s stereotypes and attitudes towards women in government are influenced by the party of women candidates is important.

Data and Methods

The data for this project come from an original public opinion survey designed to examine the impact of candidate sex and gender considerations on public evaluations of women in politics. One of the major limitations in the current state of our understanding of gender stereotypes has been data availability. Indeed, much of the existing research on stereotypes has had to rely on samples that are geographically limited (Alexander and Anderson 1993; Kahn 1996) or that relied on samples of college students (Huddy and Terkildsen 1993a, b; Fox and Smith 1998; Leeper 1991). Recently, a few studies have tried to examine gender stereotypes among the general public, relying on original surveys administered to random state or national samples (Sanbonmatsu 2002; Lawless 2004). This project continues in that vein, reporting data from a national sample based on a survey designed specifically to examine gender stereotypes and their impact on political attitudes and behaviors.

The survey was administered to a random sample of 1039 U.S. adults in September 2007. Given that Nancy Pelosi had been Speaker of the U.S. House for about 9 months and Hillary Clinton’s campaign was gearing up for the Democratic presidential primaries in late 2007, this period offers a unique time to examine the public’s thinking on women in various electoral situations.Footnote 1 The sample was stratified to represent respondents who lived in states with women governors and/or U.S. Senators and respondents from states with only men in these positions. The survey incorporated questions on a wide range of gendered political attitudes, including gender stereotypes (issue competence and personality traits), the presence of a baseline gender preference for candidates, attitudes toward gender balance in the ideal government, attitudes about what explains women’s underrepresentation in elected office, and central political variables such as political efficacy, ideology and knowledge. The survey was administered online in a WebTV environment by Knowledge Networks (KN) through their Knowledge Panel. Relying on a sampling frame that includes the entire U.S. telephone population, Knowledge Networks uses random digit dialing and probability sampling techniques to draw samples that are representative of the U.S. population. They provide, at no charge, WebTV hardware and free monthly Internet service to all sample respondents who don’t already have these services, thereby overcoming the potential problem of samples biased against individuals without access to the Internet. (Appendix 1 provides information on the demographic characteristics of the sample).

In examining whether political gender stereotypes are related to attitudes toward women in specific electoral situations and a more general support for greater descriptive representation, I employ four dependent variables (see Appendix 2 for all survey questions employed). The first measures whether respondents have a baseline gender preference when choosing among two equally qualified candidates, one a man and the other a woman. Sanbonmatsu (2002) and Rosenthal (1995) both demonstrate that many people do have a baseline preference for candidates of one sex or another. The goal here is to determine whether this baseline preference is shaped by gender stereotypes. This variable is coded 0 for those who prefer a man and 1 for those who prefer a woman.

Two dependent variables consider the important role of political party in shaping gendered political attitudes. While most work on stereotypes considers attitudes towards women as a group, women candidates in the real world usually run in partisan races, which may mean that they will be evaluated by the public from more than one perspective. Recent work that highlights the impact of party on people’s views of women would caution us against ignoring the ways in which partisanship can interact with candidate sex to shape evaluations (Brians 2005; King and Matland 2003; Koch 2002). The measures here ask respondents whether they would vote for a qualified Republican woman and (in a separate question) a qualified Democratic woman for president (coded 0 for no, 1 for yes).

The final dependent variable taps attitudes toward women’s descriptive representation by asking respondents for their opinion on the percentage of male and female officeholders in the “best government the U.S. could have.” This measure, similar to one employed in the 2006 American National Election Study (ANES) Pilot Study, is coded so that people who supported parity (50% women and 50% men) or majority-female government are coded 1 and those supporting majority male government (51–100%) are coded 0.

The primary independent variables of interest measure respondents’ stereotyped views of women and men in politics. Drawing on a long line of psychological and political science literature on gender stereotypes, I include measures of both issue competence and personal trait stereotypes. For the issue competence measures, respondents were asked whether they thought women or men in elected office were better at handling education, terrorism, health care, and the economy, or whether they saw no difference (Alexander and Anderson 1993; Huddy and Terkildsen 1993a; Kahn 1996; Koch 1999: Lawless 2004; Leeper 1991; Rossenwasser and Seale 1988; Sapiro 1981/1982; Shapiro and Mahajan 1986). For the trait measures, people were asked whether women or men candidates and officeholders tended to be more assertive, compassionate, consensus-building, and ambitious, or whether there was no difference between them (Alexander and Anderson 1993; Ashmore and Del Boca 1979; Deaux and Lewis 1984; Huddy and Terkildsen 1993a, b; Kahn 1996; Lawless 2004). Each stereotype variable is coded 1 if the respondent thinks men are better at the issue or more likely to have the trait, 2 if they see no difference between women and men, and 3 if they think women are better/more likely to possess the characteristic. Drawing on standard female and male stereotypes, the individual measures are then recoded into four variables: those measuring female issues (education, health care), male issues (terrorism, economy), female traits (compassionate, consensus-building), and male traits (assertive, ambitious).Footnote 2

The other independent variables in the analysis are respondent education (1 = less than high school through 4 = BA or higher), sex (1 = male, 2 = female), party identification (1 = strong Republican through 7 = strong Democrat) race (0 = nonwhite, 1 = white), age (in years), and income (1 = less than $5000, 20 = $175,00 or more). Also important here is the potential interaction of respondent sex and party identification, which is measured in the model by an interaction term. An additional variable in the model accounts for whether the respondent lives in a state with a woman governor or woman member of the U.S. Senate or not. Based on previous research on descriptive representation and the impact of women officeholders, we might expect that people who have experienced women leaders could have different attitudes about women in office (Lawless 2004). This variable is coded 0 if a respondent lives in a state with only male governors and Senators and one if there was at least one woman leader in the state (governor or U.S. Senate). Finally, in the models estimating support for a woman Republican candidate for president, support for a woman Democrat for president, and gender balance in government, I add the variable measuring baseline gender preference as an independent variable. If baseline gender preference is an important attitude that is related to other attitudes and behaviors, it should be related to the other three dependent variables (Sanbonmatsu 2002). Indeed, a check of the correlations suggests that this will be an important control on the relationship between the stereotypes and the other dependent variables.Footnote 3

Analysis

Support for Women

The first step in the analysis is to examine the distribution of attitudes toward women candidates and officeholders in general and confirm the presence of gender stereotyped thinking with regard to women and men in politics. Table 1 presents the frequency distributions for the four dependent variables for the entire sample and then by respondent sex and political party. There are few surprises here. Among the entire sample, a majority of respondents (60%) have a baseline gender preference for a man candidate, but a sizeable minority (40%) indicates that they would prefer a woman. A majority of respondents claim a willingness to vote for a Republican woman for president (60%). But support for a Democratic woman candidate for president is clearly higher, with 71% of respondents expressing this perspective. Since the survey was taken in September 2007, this may be, in part, the influence of Hillary Clinton’s candidacy. However, it is more likely another confirmation of the finding that Republican women candidates sometimes face greater electoral challenges than do Democratic women (King and Matland 2003; Palmer and Simon 2006; Lawless and Pearson 2008). Finally, when asked for their vision of gender balance in the “best government,” a majority of people (53%) call for parity between women and men. It is interesting to note that people’s ideal is something that is light years away from reality, although this response may be influenced by some respondents desire to appear unbiased. At the same time, social desirability cannot be exclusively shaping responses, as fully 39% of the sample is comfortable reporting that they would prefer majority-male government (between 51% and 100%) and only 9% of respondents desire majority-female government.

The other columns in Table 1 demonstrate the importance of sex and partisanship to respondent attitudes toward women in politics. On each of the four dependent variables, women in the sample are more likely to favor supporting a woman than are men. This finding reinforces earlier work on descriptive representation that demonstrates these gender-based influences (Rosenthal 1995; Sanbonmatsu 2002). The frequencies by party suggest that, while Democrats generally show more willingness to support women in office than Republicans do, this generosity does not extend to supporting women when they are Republicans. Too, these data demonstrate support for the finding from other research that women Republicans have a harder time gaining support among their own party members than do women Democrats. Here, 20% of Republican respondents would not support a Republican woman for president, while only 11% of Democrats would reject a Democratic woman (King and Matland 2003; Lawless and Pearson 2008).

Stereotypes

Table 2 presents a mixed picture of the presence of political gender stereotypes in the sample. With regard to stereotypes about women’s and men’s issue competencies, there are few surprises. On three of the four issues, a majority of respondents see one sex as better at handling the issue than the other sex and these attitudes fall in the expected direction. Majorities see women as better able to handle education and health care and see men as more competent at handling terrorism. However, it is worth noting that between 38% and 40% of respondents see no difference between women and men in the ability to handle each of these issues. On economic matters, which is generally considered a “male” area of expertise, 51% of respondents saw no difference between women and men in ability to handle the issue and only 28% held the predicted stereotype of male competence.

With regard to the trait stereotypes, the picture is less clear. On three of the four traits (assertive, consensus-builder, ambitious), either a plurality or majority of people saw no difference between women and men in the likelihood of possessing that trait. Only on the variable measuring compassion did a majority of respondents (71%) hold the expected stereotype, which is assuming women would be more compassionate than men. Again, while it is difficult to tell whether respondents are expressing a desire to appear egalitarian in their evaluations of the personality traits of women and men, between 20% and 40% of respondents are willing to say that they see men as more likely to be ambitious, consensus-oriented, or assertive. Instead, it is also possible that stereotypes about traits are changing or that people are more likely to hold stereotypes about issue competence than about personality traits. In general, the ability of the public to evaluate women candidates as assertive or ambitious as easily as they do men remains a relatively recent phenomenon. At the same time, even in 2007, between 50% and 70% of the respondents employed traditional gender stereotypes on five of the eight issue and trait measures. Despite the integration of women into elected office and the presence of high visibility figures like Nancy Pelosi, Sarah Palin, and Hillary Clinton, reliance on gender stereotypes is still the most common response when evaluating political women.

Predicting Stereotypes

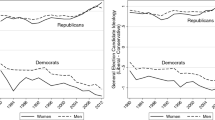

The key question posed by this project is whether and how gender stereotypes are related to the attitudes people hold about women candidates and women in office. However, the possession of political gender stereotypes is no doubt shaped by individual-level respondent characteristics. Therefore, before we examine the relationship of stereotypes to attitudes, it is important to get a sense of the determinants of stereotypes themselves. Table 3 presents a regression analysis of the four stereotype variables as a function of respondent demographic and political characteristics—education, sex, party identification, race, age, income, and the interaction of sex and partisanship. The female and male policy variables are coded such that a low value indicates that respondents see men as better able to handle these issues and a high value indicates that they see women as better at these issues. The trait stereotypes are coded in the same fashion—low values mean that respondents see men as more likely to possess the traits in each variable, while high values indicate that they see women as more likely to possess these characteristics.Footnote 4

The first thing to note about the data presented in Table 3 is that the models do a better job of predicting people’s evaluations of female stereotypes than of male stereotypes. Only respondent sex and party identification are significantly related to male policy stereotypes and none of the variables in the model are related to male traits. With regard to policy, men and Republicans see men as better able to handle male policies than women, while women and Democrats see women as better able to handle these issues than men. For the female stereotypes, respondent sex and party identification are the strongest predictor of these attitudes, but characteristics like education, age, and income matter as well.

The second thing to notice about the determinants of stereotypes is that respondent sex and party identification are significantly related to three of the four stereotypes. For the female and male policy measures, this means that women and Democrats in the sample are more likely to see women as better at these issues, while men and Republicans see men as better at both sets. The interesting thing is that this pattern holds for both female and male policies. So, it is not necessarily the case that people see women or men as better at particular issues that are consistent with stereotyped expectations based on policy area (women with education, men with economics). Instead, the data suggest that the stereotype is one of sex superiority in general—women and Democrats see women as better at all issues, female or male, and men and Republicans see men as better at all issues. For female traits, the same pattern exists. Women and Democrats are more likely to see women as compassionate and consensus oriented and men and Republicans see men as possessing these skills more than women. So the data on three of the four stereotype measures suggests a “sex superiority” effect—people tend to see one sex or the other as more capable on all of the issues and possessing the more positive characteristics across the board.

The final thing to note here is the significance of the interaction of respondent sex and party for people’s evaluations of female stereotypes. In evaluating whether women or men are better at female policies or possess female characteristics, the impact of party identification is less important for women and more important for men. Another way of looking at this is to say that respondent sex matters less for differentiating among Democrats and matters more among Republicans.

Stereotypes and Support for Women

The main hypothesis tested in this research is that political gender stereotypes are not just interesting attitudes, but that they are also consequential. Specifically, I expect that they are related to people’s level of support for women in various electoral circumstances. In order to gauge this, I conducted a logistic regression analysis on each of the four dependent variables—baseline preference for a woman or man candidate, willingness to vote for a woman Republican for president, willingness to vote for a woman Democrat for president, and support for greater gender balance in government. The primary independent variables of interest are the four stereotype variables—female policy, male policy, female traits, and male traits. The other variables in the model are those discussed in the earlier section on data and methods. Because the coefficients of a logit analysis are not as easily interpreted as other regression results, I use the coefficients for the significant stereotype variables to calculate predicted probabilities for the impact of these attitudes on support for women in the different electoral situations.Footnote 5 (The full logit analysis is presented in Table 4).

Figures 1–4 present graphs that demonstrate the change in the probability that people would support a women on each dependent variable as a function of their stereotyped evaluations. Recall that the stereotype variables are coded to measure whether respondents see women or men as better able to handle the female and male policy areas and whether they see women or men as more likely to possess the female and male traits. Taking the baseline preference variable first (Fig. 1), we see that people’s attitudes on female policy, male policy, and female trait stereotypes are significantly related to their preference for supporting a woman over a man. The probability that a respondent who sees men as better at female policy issues (education and health care) will prefer the woman over the man is .19. However, for those who see women as better at female policy areas, the probability of supporting the woman rises to .42. This provides clear support for the hypothesis that people who see women as more competent at certain policy areas will be more likely to support women for office. The same pattern is true for the female trait stereotype. Respondents who see men as more likely to possess the female traits (compassion and consensus orientation) have a .20 probability of preferring to support a woman. This probability rises to .42 among people who see women as stronger on the stereotypical female characteristics. Yet, the strongest relationship in the model is between evaluation of competence on stereotypical male policy issues and preference for a woman. Here, we see that the probability of preferring a woman is .12 among those who see men as better at male policy issues (economy and terrorism). However, among those who see women as better able to handle these male issues, the probability of supporting a woman is .84. This is an enormous increase and it speaks to the power of people’s evaluations of women’s competence in dealing with stereotypical male issues in increasing their comfort level with voting for a woman.

The two variables measuring support for women based on their political party offers an interesting insight. The only stereotype variable related to people’s willingness to support a woman Republican for president is their evaluation of male policy issues. Figure 2 demonstrates the importance of perceived female competence on these male issues. The probability of supporting a woman Republican increases from .55 among those who see men as better at male issues than woman to .71 among those who see women as better than men. The absence of a significant impact for evaluations of female policy stereotypes suggests that people view Republican candidates, or at least Republican women candidates, more closely through the lens of male issues. This may be the case because Republicans are generally more closely associated with a concern for these male policy areas than are Democrats, leading to people having a heightened sense of their importance to this evaluation. Neither female nor male trait stereotypes are significant in this analysis.

The story is a bit different for people’s support for a woman Democrat for president (Fig. 3). Here, both female and male policy stereotypes are significant. But, as with the two previous analyses, we see an important role for evaluations on male issues. As respondents move from seeing men as better on female policy issues to seeing women as better on these issues, the probability of supporting the woman Democrat for president rises from .63 to .88. Overall levels of support for a woman running for president as a Democrat are clearly higher than they are for a Republican woman. Here the impact of the male issue stereotypes is just as large, increasing the probability of supporting a woman Democrat from .70 among those who see men as better at the economy and terrorism to .95 among those who see women as better able to handle these issues. As with the variable measuring support for a woman Republican, neither of the trait stereotypes is significant here.

Finally, in Fig. 4 we see the continued importance of policy stereotypes and the lack of a role for trait stereotypes in the variable measuring support for greater gender balance in government. As with baseline preference for a woman and support for a woman Democrat for president, evaluations of male policy issues are more important to support for a greater number of women than are evaluations of female policy areas, although both are significant in the model. Taking female policy attitudes first, we see a rise in the predicted probability of desiring more gender balance in government from .48 to .64 as people move from seeing men as having an advantage on these issues to seeing women as having the advantage. Yet, the impact of evaluations of male issues is enormous, with the probability of favoring parity increasing from .33 among those who see men as better than woman on male issues to .95 among those who see women as better on these issues than men. Neither of the trait stereotypes is significantly related to a desire for gender parity in government.

Another thing to note from the full models is the performance of respondent sex and partisanship in these models. In Table 3, we saw a general impact of these two variables on gender stereotypes and a role for the interaction of the two for female stereotypes. However, in the analysis of the variables measuring support for women in the four situations (Table 4), we see no direct influence for respondent sex. Respondent party identification is significantly related to three of the four variables—baseline preference, and support for a Republican or Democratic woman for president—in the expected directions. None of the variables measuring the interaction of respondent sex and party identification are significant here. So, while respondent sex may not have a direct effect independent of stereotypes on attitudes towards women in these situations, it has an important indirect effect through the shaping of stereotypes themselves. The same could be said for the lack of direct influence of respondent education, age, race, or income on support for women. The impact of these variables is present indirectly through their (limited) impact on stereotypes. Political party appears to play a more important role, both indirectly through its influence on stereotypes and directly in the impact on attitudes toward the various electoral situations.

In sum, the hypothesis that stereotypes matter to people’s willingness to support women in elective office receives clear and convincing support from this analysis. At the same time, the findings require a refinement in this thinking. Clearly, as the lack of impact of trait stereotypes demonstrates, all stereotypes are not equally important to electoral evaluations. This is an important finding, as it allows us to bring more precision to our understanding of the actual impact of political gender stereotypes. As noted earlier, our knowledge of the presence of gender stereotypes is extensive. What we have been lacking is a clear sense of whether these stereotypes help or hinder women (and men) candidates when they run for office. The finding of the relative lack of importance of trait stereotypes suggests that women who seek office may have to worry somewhat less than imagined about the personality traits they exhibit on the campaign trail.

The other major refinement in our thinking about stereotypes should be to understand the importance of issue stereotypes. These results demonstrate that stereotyped thinking on both female and male policy issues is central to people’s evaluations of women candidates. Too, we should note the importance that establishing competence on male issues would appear to have for women candidates. Of the four stereotype variables, male policy is the only one significantly related to all four of the variables measuring support for women. In each equation, it is the most important explanatory variable. As the figures demonstrate, evaluation of women’s abilities to handle stereotypical male issues has an enormous impact on willingness to support women in electoral situations. This would suggest that neutralizing the view that women are less capable at handling male issues is an important key to women candidates as they seek to gain voter support. Again, this finding expands our understanding of stereotypes by moving beyond cataloging their presence to understanding their impact.

Conclusion

That women are underrepresented in elective office in the U.S. is an obvious reality. Scholars of gender politics have examined the myriad reasons for this reality and have identified several important elements. One focus of these examinations is the role that evaluations of women’s abilities can play in shaping support for greater gender representation. The research reported here extends our understanding of the impact of these evaluations by focusing on political gender stereotypes and how they can influence people’s desire to see more women in elective office.

In line with other studies, the results reported here suggest that people still hold policy and trait stereotypes about women and men. Beyond that, the evidence presented here allows us to extend our understanding of how people use stereotypes in evaluating the appropriate role for women in office and provides general support for the hypothesis that people’s judgments about women’s capabilities shapes their willingness to support them in electoral situations. Trait stereotypes are of very limited utility in understanding support for women. However, views on policy stereotypes and, more specifically, views on stereotypically male issues are very important. People who see women as competent to deal with things like the economy and terrorism are dramatically more likely to voice a willingness to support them for office and a desire for greater gender balance in government. While the same pattern is evident for evaluations of women’s competence on female issues, evaluations of male issues are much more important. This would suggest that attention to bolstering credibility on these issues, or even working to neutralize the stereotypes, would serve women candidates well.

Notes

While this study does not directly examine people’s evaluations of Pelosi or Clinton, I do acknowledge that their presence in the political world may have influenced how people think about the appropriate representation of women in government. This notion that observing women in office can influence public attitudes is the basis for the work on the impact of women’s symbolic mobilization (Atkeson 2003; Hansen 1997; Koch 1997).

The correlations between the four variables measuring the gendered political stereotypes are as follows:

Female policy

Male policy

Female traits

Male traits

Female policy

–

.245*

.398*

.134*

Male policy

.245*

–

.232*

.338*

Female traits

.398*

.232*

–

−.038

Male traits

.134*

.338*

-.038

–

The correlations between the four dependent variables are as follows:

Baseline preference

Women president Republican

Women president Democrat

Parity

Baseline Preference

–

−.029

.431*

.384*

Republican Women president

−.029

–

.094*

.045

Democrat Women president

.431*

.094*

–

.360*

Gender parity

.384*

.045

.360*

–

Recall that the female policies are education and health care, while the male policies are terrorism and the economy. Female traits are compassionate and consensus building, while male traits are ambitious and aggressive.

I also conducted a seemingly unrelated estimates (SUE) analysis. The results of that analysis were completely consistent with the results reported in Table 4.

References

Alexander, D., & Andersen, K. (1993). Gender as a factor in the attribution of leadership traits. Political Research Quarterly, 46, 527–545.

Ashmore, R., & Del Boca, F. (1979). Sex stereotypes and implicit personality theory: Toward a cognitive-social psychological conceptualization. Sex Roles, 5, 219–248. doi:10.1007/BF00287932.

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not All cues are created equal: The conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. The Journal of Politics, 65, 1040–1061. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00124.

Brians, C. (2005). Women for women: Gender and party bias in voting for female candidates. American Politics Research, 33, 357–375. doi:10.1177/1532673X04269415.

Burrell, B. (1994). A woman’s place is in the house: Campaigning for congress in the feminist era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Burrell, B. (2008). Political parties, fund-raising, and sex. In B. Reingold (Ed.), Legislative women: Getting elected, getting ahead. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Center for American Women, Politics. (2009). Women in elective office 2009. Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University.

Deaux, K., & Lewis, L. (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 991–1004.

Dolan, K. (2004). Voting for women: How the public evaluates women candidates. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Fox, R., & Smith, E. (1998). The role of candidate sex in voter decision making. Political Psychology, 19, 405–419.

Fulton, S., Maestas, C., Maisel, L. S., & Stone, W. (2006). The sense of a woman: Gender, ambition, and the decision to run for congress. Political Research Quarterly, 59, 235–248.

Hansen, S. (1997). Talking about politics: Gender and contextual effects on political proselytizing. Journal of Politics, 59, 73–103.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993a). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 119–147.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993b). The consequences of gender stereotypes for women candidates at different levels and types of office. Political Research Quarterly, 46, 503–525.

Kahn, K. (1996). The political consequences of being a woman: How stereotypes influence the conduct and consequences of political campaigns. New York: Columbia University Press.

King, D., & Matland, R. (2003). Sex and the grand old party: An experimental investigation of the effect of candidate sex on support for a Republican candidate. American Politics Research, 31, 595–612.

Koch, J. (1997). Candidate gender and women’s psychological engagement in politics. American Politics Quarterly, 25, 118–133.

Koch, J. (1999). Candidate gender and assessments of senate candidates. Social Science Quarterly, 80, 84–96.

Koch, J. (2002). Gender stereotypes and citizens’ impression of house candidates ideological orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 453–462.

Lawless, J. (2004). Women, war, and winning elections: Gender stereotyping in the post-September 11th era. Political Research Quarterly, 57, 479–490.

Lawless, J., & Fox, R. (2005). It takes a candidate: Why women don’t run for office. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, J., & Pearson, K. (2008). The primary reason for women’s underrepresentation? Reevaluating the conventional wisdom. Journal of Politics, 70, 67–82.

Leeper, M. (1991). The impact of prejudice on female candidates: An experimental look at voter inference. American Politics Quarterly, 19, 248–261.

Palmer, B., & Simon, D. (2006). Breaking the political glass ceiling: Women and congressional elections. New York: Routledge.

Rosenthal, C. S. (1995). The role of gender in descriptive representation. Political Research Quarterly, 48, 599–611.

Rossenwasser, S., & Seale, J. (1988). Attitudes toward a hypothetical male or female presidential candidate—a research note. Political Psychology, 9, 591–598.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 20–34.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2006). Where women run: Gender and party in the American states. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Sanbonmatsu, K. & Dolan, K. (2009). Do gender stereotypes transcend party? Political Research Quarterly, 62.

Sapiro, V. (1981/1982). If U.S. Senator Baker were a woman: An experimental study of candidate images. Political Psychology, 7, 61–83.

Shapiro, R., & Mahajan, H. (1986). Gender differences in policy preferences: A summary of trends from the 1960s to the 1980s. Public Opinion Quarterly, 50, 42–61.

Simmons, W. (2001, January). A majority of Americans say more women in political office would be positive for the country. The Gallup Poll Monthly, 6–9.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Jennifer Lawless, Tom Holbrook, and the reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1—Demographics of Survey Respondents

See Table 5.

Appendix 2

Dependent Variables

-

1.

If two equally qualified candidates were running for office, one a man and the other a woman, do you think you would be more likely to vote for the man or the woman?

Man/Woman

-

2.

If the Republican Party nominated a woman for President, would you vote for her if she were qualified for the job?

Yes/No

-

3.

If the Democratic Party nominated a woman for President, would you vote for her if she were qualified for the job?

Yes/No

-

4.

In your opinion, in the best government the U.S. could have, what percent, [from 0 to 100], of elected officials would be men and what percentage would be women?

Independent Variables

-

1.

In general, do you think men or women in elected office are better at (improving our schools, dealing with terrorism, handling health care issues, handling the economy)?

Man/Woman/No Difference

-

2.

When you think about political candidates and officeholders, do you think men or women would tend to be more (assertive, compassionate, consensus builder, ambitious)?

Man/Woman/No Difference

-

3.

Respondent sex, education, party identification, race, age, income, and state of residence

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dolan, K. The Impact of Gender Stereotyped Evaluations on Support for Women Candidates. Polit Behav 32, 69–88 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9090-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9090-4