Abstract

Background Deprescribing is the process of medication withdrawal with the aims of reducing the harms of potentially inappropriate medication use and improving patient outcomes. Deprescribing of statins may be indicated for some older people, because the evidence for benefit in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease is limited and there is an increased risk of side effects in old age. Objective To determine older peoples’ attitudes and beliefs regarding medication use and their willingness to have regular medications, particularly statins, deprescribed. Setting An Australian acute-care hospital. Method A cross-sectional study of patients admitted to a teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia, aged ≥65 years and taking a statin was conducted. Attitudes and beliefs regarding medication use and willingness to have medications or statins deprescribed were captured using the validated Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing questionnaire, supplemented with additional statin-specific questions. Main outcome measures. Older inpatients’ attitudes and perspectives towards stopping medications, in particular statins. Results Overall, 180 participants were recruited, with a median age of 78 years, (interquartile range 71–85). Eighty-nine percent (95 % CI 84.4–93.6) of participants reported that they would be willing to stop one or more of their regular medications if their doctor said it was possible. Ninety-five percent (95 % CI 91.8–98.2) agreed that they would be willing to have a statin deprescribed. Moreover, 94 % (95 % CI 90.5–97.5) of participants expressed concern regarding the potential side effects of taking a statin. Conclusion The majority of older inpatients using statins are willing to have one or more of their current medications, including statins, deprescribed. These findings can be used to inform clinical practice and interventional statin deprescribing studies to optimise medication use in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on Practice

-

Australian Health Professionals can discuss medication withdrawal with their patients with the assurance that most patients are willing to consider having a medication deprescribed if their doctor recommends it.

-

Medical practitioners could expect that most older inpatients would be willing to have their statin deprescribed if their doctor recommended it because of limited evidence of benefit in that individual or high risk of adverse events.

-

Practitioners should anticipate that a small proportion of patients will not be willing to consider having a medication withdrawn, and further detailed investigation of barriers to deprescribing in these patients will be necessary to optimise medications for the individual.

Introduction

Deprescribing is the process of tapering or stopping medications with the aim of improving patient outcomes and optimising current therapy [1, 2]. Emerging evidence from observational and limited interventional studies of older people suggests that deprescribing is associated with improvements in quality of life and survival [1–4]. The potential benefits of a systematic, patient-centred deprescribing process may also extend to improved adherence and reduced financial costs [3]. However, as with any medical intervention, deprescribing may be associated with potential harms, such as withdrawal reactions or the reappearance of symptoms of the original disorder [3, 4]. Whilst deprescribing should be supervised by a health care professional it is essential to understand patients’ views and preferences towards pharmacotherapy and their willingness to have medications deprescribed, in order to achieve patient-centred care [5].

Several studies have shown that systematic deprescribing may be feasible [6–9], however, the translation of these into practice may be limited due to multiple barriers. General practitioners have reported that a major barrier to optimising medication use is patient resistance to have a medication ceased [10]. Qualitative studies of older adults have identified a number of factors that may influence their willingness to have a medication withdrawn, such as older age, duration of therapy, perceptions of need and the complexity of a medication regimen [11–14]. Recently, the Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire was developed to determine peoples’ attitudes and beliefs towards medication use, specifically in relation to medication withdrawal. In a population of outpatients taking an average of ten medications each, over 90 % of people were willing to have one or more medications deprescribed [15].

Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG) coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) are one of the most common pharmacological classes used by older people with over 40 % of Australians aged over 65 years taking a statin [16]. However, the appropriate use of statins in older people remains a matter of debate internationally. In older people, there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of statin therapy in secondary prevention of cardiovascular morbidity [17–19]. The evidence for statin use in primary prevention in this demographic is less clear [20–22] and yet risks of adverse effects of these medications are higher in older adults [23]. Moreover, as people age care goals may change from extending duration of life to maintaining function and quality of life. Considering older people’s attitudes to optimising statin therapy is crucial as whether to start, continue or discontinue statins remains a clinical and ethical dilemma in older people, particularly for those aged 80 years and over. Currently, there is limited evidence on the attitudes and beliefs of older people treated with statin therapy and their perspectives towards having their statins deprescribed.

Aims of the study

In a population of older inpatients prescribed statins, the aims of this study were to determine older peoples’ attitudes and beliefs regarding medication use and their willingness to have regular medications, particularly statins, deprescribed and to investigate whether participant characteristics would influence willingness to deprescribe medications or statins.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Northern Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee, Sydney, Australia (Ethics approval number: LNR/14/HAWKE/180).

Method

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study of participants admitted to the Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia was conducted. Individuals were invited to participate if they were aged 65 years and over, admitted to the cardiology, geriatric, orthopaedic or general medical wards, currently treated with a statin, able to speak and understand English, and provide consent. Participants were excluded if they were cognitively or functionally impaired as judged by the nurses on each study ward or refused to participate. Data collection occurred from the 30th July 2014 to 10th October 2014. Potential participants were provided with an information sheet and signed consent was obtained prior to administration of the questionnaire.

Data collection

Following consent, two trained pharmacy research students orally administered the study questionnaire. Data on socio-demographics and clinical characteristics were captured during the interview and from patient medical records. Medication use was documented at the time of recruitment from the national inpatient medication chart.

Attitudes and beliefs regarding medication use and statin therapy

Older peoples’ attitudes and perceptions regarding medication use were captured on a five-point Likert scale using the first ten items of the validated PATD questionnaire [15, 24]. As previously published, the PATD development included piloting and expert opinion reviews, after which the questionnaire underwent psychometric testing (face, content, and criterion validity; sensitivity; and test–retest reliability). Seven additional statin specific questions, of which five were captured on a five-point Likert scale were developed to meet the study objectives, in particular to assess patients’ attitudes, beliefs and experiences regarding their statin medications, how they would feel about cessation of their statin medications and if they recently heard negative information regarding statins. Statin questions were reviewed by all investigators for content validity and then piloted with participants for face validity. After piloting, five questions (four Likert scale questions and a question in relation to negative information about statins) were retained due to poor face validity of two items.

Clinical data

Socio-demographic data including age, gender, marital status (married, widowed or other), ethnicity (Caucasian or other) and level of education (secondary or above) were collected. Clinical data including comorbidities, frailty and cognition were assessed using the following validated tools: (a) Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [25], (b) Mini-Mental state examination (administered to the participant) [26] and (c) Reported Edmonton Frail Scale (REFS) [27]. As per previous studies, a REFS score of ≥8 was considered frail [27] and a MMSE of ≤23 was used to screen for cognitive impairment [26]. Patients were considered as treated for secondary prevention with statins if they had a documented past medical history of cardiovascular disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction or diabetes mellitus. Polypharmacy was defined as the use of five or more medications. Statin therapy data including statin type, duration of use (number of years), daily dose (high, medium or low dose) and indication were collected. The daily dose of each statin was standardised according to the lipid-lowering effect of 10 mg of atorvastatin (equivalent to 20 mg of simvastatin, 40 mg of pravastatin and 5 mg of rosuvastatin). Statin doses were categorised as low (<2 standardised units), medium (2–4 standardised units) and high dose (>4 standardised units) [28].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population characteristics. All data were reported as medians with an interquartile range (IQR) or proportions as appropriate. Percentage agreement with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CIs) for the PATD responses and five statin specific items were calculated by combining those who agreed or strongly agreed (remaining participants were unsure, disagreed or strongly disagreed).

We performed analysis between patient (e.g. age, frailty, cognition) and statin therapy (e.g. duration of use, indication) characteristics and their responses. Relationships between subject age and their willingness to stop medications, specifically statins were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation. The Mann–Whitney U statistic was used to compare responses on willingness to have medications or statins deprescribed according to participant and statin therapy related characteristics. A higher mean rank indicates that participants allocated higher scores for the questionnaire items, translating to a greater level of agreement with willingness to have medication or statins deprescribed [29]. Gamma rank correlation was used to internally validate and explore relationships between responses to the PATD questionnaire and additional statin questions. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. To internally validate the newly developed statin questions, we correlated statin questions with appropriate PATD questions. Finally, a subset of the participants (n = 15) was also recruited for PATD inter-rater reliability testing. Three investigators administered the PATD questionnaire to perform inter-rater reliability for the PATD statements and four statin items. The administrations occurred on two different days, 2–5 days apart. Gamma rank correlation was used to determine inter-rater reliability. Data were coded and analysed using the SPSS Statistics version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL).

Results

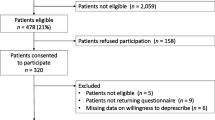

A total of 294 subjects were identified as potential study participants. Of these, 69 individuals were excluded (e.g. poor cognitive function (n = 23); functional impairment (n = 6); inadequate English language skills (n = 19); isolation in additional precautions room (n = 21) and 26 were missed due to being discharged before being approached to take part in the study). In total, 199 participants were approached and a final 180 (90 %) participants consented to take part in the study. The study population characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median participant age was 78, (interquartile range (IQR) = 71–85 with a median CCI score of two (IQR = 1.0–4.0) and a median of ten prescription medications (IQR = 7–12) taken.

Responses to the PATD questionnaire and statin questions

The responses to the PATD questionnaire and statin questions are presented in Fig. 1. Eighty-nine percent (95 % CI 84.4–93.6) of participants reported that they would be willing to stop one or more of their regular medications if deemed appropriate by their prescriber. Additionally, if their doctor said it was possible, 95 % (95 % CI 91.8–98.2) of participants agreed that they would be willing to have a statin deprescribed and 95 % (95 % CI 91.8–98.2) trusted their prescriber to inform them if it was necessary to stop their statin. Moreover, 94 % (95 % CI 90.5–97.5) of participants expressed concern regarding the potential side effects of taking a statin. Thirty-seven percent reported that they had recently heard negative information regarding statins, and of those, 95 % recalled it was through media (3 % from a health care professional, 2 % from a family member/friend).

Willingness to have a medication or statin deprescribed according to participant and statin therapy characteristics

Age, being frail, presence of cognitive impairment and polypharmacy did not significantly influence patient willingness to have their medications deprescribed (Table 2). With respect to statins, frail older adults were less willing to stop a statin than robust older adults (p = 0.035). Duration of statin use (≥10 vs. <10 years) and indication (primary vs. secondary prevention) was not related to willingness to deprescribe a statin (p = 0.224 and 0.945, respectively).

Correlations between responses to PATD and statin questions

Feeling comfortable with one’s number of medications was positively correlated with a willingness to continue taking statins (G = 0.521, p = 0.002). Increasing degree of comfort with current number of medications was correlated with reduced concern for possible statin side-effects (G = −0.440, p = 0.000). Willingness to continue taking a statin was positively correlated with trust in the prescriber to inform of necessary statin cessation (G = 0.867, p = 0.000).

Inter-rater reliability

Measures of association between the first and second administration of the PATD and the four Likert statin questions yielded gamma values that ranged from 0.76 to 1.00 with one outlier value for statement seven (G = 0.476, p = 0.302) (See Table 3).

Discussion

This study found that, if deemed appropriate by their doctor, the overwhelming majority of older inpatients prescribed a statin would be willing for one or more of their medications to be deprescribed, and an even higher proportion would accept having their statin deprescribed. No patient-related factors affected willingness to have any medication deprescribed. Interestingly frailty was associated with reduced willingness to have a statin deprescribed. These results are in concordance with the previous PATD study [15]. The addition of statin specific questions with a similarly high percentage of acceptance strengthens our conclusion that older adults are, in general, willing to consider deprescribing if introduced by their doctor.

Comparison of the willingness found in this study to other interventional deprescribing studies is challenging due to the variability in which patient acceptance of medication cessation is captured. For example, one study reported that only a third of patients accepted recommendations of medication withdrawal [8], whilst another presented a significantly higher acceptance rate of 82 % [6]. In our study, a high willingness to have statins deprescribed was observed with 95 % of participants willing to have their statin deprescribed. This is comparable to a physician driven deprescribing study conducted by Garfinkel et al. [6], in which 78 % of older patients had their statins ceased (this percentage reflects combined patient and primary care provider acceptance of recommendation from the study geriatrician). Similarly, a study by Van Duijin found that 94 % of patients with low cardiovascular risk advised to deprescribe their anti-hypertensive or statin medications decided to stop [30].

In concordance with the previous employment of the PATD, participant age, frailty status, number of medications and cognitive status were not found to significantly affect older adults’ willingness to stop a medication (question 4). Contrastingly, previous studies have proposed that older age may be associated with resistance to therapy change and potentially a lower willingness to have medications deprescribed [11, 12]. Furthermore, two studies into patients beliefs of antidepressants and tamoxifen found that a greater number of medications led to continuation [11, 14], whilst another study focusing on osteoporosis medication cited inconvenience as a factor that promoted discontinuation [12]. This contrast highlights that it may not be the complexity of a regimen or the presence of polypharmacy that defines willingness to deprescribe, but rather patients’ perceptions of what constitutes an inconvenient or necessary number of medications.

Interestingly, frail older adults were found to be less willing to deprescribe their statin specifically than robust older adults, however, the percentage agreement in the frail was still greater than 90 %. Frail older adults have previously been shown to have a high belief in the necessity of their medications and a low concern for potential harms [31], which may explain the difference observed in this study. Evidence in relation to younger statin users and non-adherence to statins indicates a lower perceived risk of cardiovascular mortality is associated with a higher rate of self-cessation of statins [29, 32–35]. This may therefore be a factor worth exploring in future patient centred deprescribing studies. However, as the vast majority of older adults are willing to have their medicines and statins deprescribed, predicting factors may be of little practical importance.

Previous studies have supported the influence of the prescriber on attitudes to therapy and medication taking behaviour. In this questionnaire, over 90 % of older adults agreed that they would be willing to trial statin deprescribing if deemed appropriate by their prescriber and 95 % of participants placed trust in their doctor to inform of necessary statin cessation. Additionally the previous employment of the PATD found a potential correlation between trust in physician and willingness to cease a medication. Therefore, a higher acceptance of deprescribing may be facilitated by greater physician involvement in recommending therapy change [8]. However, several studies have highlighted multiple prescriber barriers to deprescribing [1, 5, 10]. General practitioners (GPs) have expressed difficulty deprescribing in regular practice due to time constraints, as well as a lack of systematic guidelines and decision-making tools to identify appropriate circumstances in which to deprescribe [10]. GPs also voiced trepidation in discontinuing medications originally initiated by other doctors or medical specialists [1, 6, 36].

A high proportion of older adults expressed concern regarding the potential side effects of statin use, which may be attributed in part to the recent Australian media coverage regarding the adverse effects of statin therapy [37]. Indeed, the impact of media on statin taking behaviour has been suggested by several studies [34, 38]. Media was shown to negatively distort the perceived risk versus benefit ratio of statin therapy [38] through the emphasis of the potential statin-mediated adverse events over treatment benefits. Furthermore, media attention surrounding the withdrawal of cerivastatin was paralleled by a temporary decline in overall statin persistence [34].

Strengths and limitations

There are a number of strengths to this study, including high recruitment rates (80 %), giving a highly representative sample of the population studied. The assessment of patient attitudes, beliefs and perceptions towards medication use and clinical characteristics were based on validated tools. The inter-rater reliability further validates the PATD and statin-specific questions for verbal administration. The statement with the lowest correlation between administrations focused on participant willingness to accept more medications. Responses to this statement may have varied due to the hospital setting, where participants may have been acutely unwell and recently initiated on new medications around the time of recruitment.

However, a limitation of this research stems from its single site, in hospital population. This population represents the least healthy proportion of statin users, as patients taking statins are predominantly managed in the community by general practitioners. It is possible that community dwelling statin users (or even the study participants when not acutely ill) may be more willing to trial deprescribing of their statin as they are healthier and therefore may not see it as necessary. Conversely, they may be less willing due to a concern about ‘rocking the boat’. Additionally, patients’ attitudes towards medications may vary depending on the country and its health care system (i.e. how medications are provided and subsidised/reimbursed). Future studies in other acute and community settings internationally are required to confirm the generalizability of these results. Data on some clinical characteristics such as duration of statin use and data for frailty scales, was based on self-report, which may result in recall bias and inaccuracies, especially in those with cognitive impairment. For some participants a desire to portray themselves more positively may have impacted responses to patient perceptions regarding their understanding of current therapy or the impact of medication related costs on willingness to have therapy deprescribed.

Conclusion

This study suggests that almost all older adults treated with statins are willing to have one or more of their medications deprescribed, and an even greater proportion is willing to have their statins specifically withdrawn. These results strengthen the call for efforts to consider deprescribing in routine clinical care when appropriate, as patients themselves may not be the major barrier. Medical practitioners should discuss deprescribing of statins with individuals who they consider may be suitable for deprescribing with the assurance that most older patients are willing to take their doctor’s advice on this. Future interventional studies are needed to determine the outcomes of deprescribing statins.

References

Scott IA, Anderson K, Freeman CR, Stowasser DA. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust. 2014;201(7):390–2.

Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Hilmer SN. Discontinuing drug treatments. BMJ. 2014;349:g7013.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201(7):386–9.

Le Couteur D, Banks E, Gnjidic D, McLachlan A. Deprescribing. Aust Prescr. 2011;34(6):182–5.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(4):738–47.

Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1648–54.

Beer C, Loh PK, Peng YG, Potter K, Millar A. A pilot randomized controlled trial of deprescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(2):37–43.

Williams ME, Pulliam CC, Hunter R, Johnson TM, Owens JE, Kincaid J, et al. The short-term effect of interdisciplinary medication review on function and cost in ambulatory elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):93–8.

Reeve E, Andrews JM, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S. Feasibility of a patient-centered deprescribing process to reduce inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(1):29–38.

Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of dutch gps. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:56.

Dickinson R, Knapp P, House AO, Dimri V, Zermansky A, Petty D, et al. Long-term prescribing of antidepressants in the older population: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(573):e144–55.

Mazor KM, Velten S, Andrade SE, Yood RA. Older women’s views about prescription osteoporosis medication: a cross-sectional, qualitative study. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):999–1008.

Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3309–15.

Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(2):215–20.

Reeve E, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S. People’s attitudes, beliefs, and experiences regarding polypharmacy and willingness to deprescribe. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1508–14.

Morgan TK, Williamson M, Pirotta M, Stewart K, Myers SP, Barnes J. A national census of medicines use: a 24-hour snapshot of australians aged 50 years and older. Med J Aust. 2012;196(1):50–3.

Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG. Thinking through the medication list - appropriate prescribing and deprescribing in robust and frail older patients. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(12):924–8.

Roberts CG, Guallar E, Rodriguez A. Efficacy and safety of statin monotherapy in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(8):879–87.

Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:Cd004816.

Abramson JD, Rosenberg HG, Jewell N, Wright JM. Should people at low risk of cardiovascular disease take a statin? BMJ. 2013;347:f6123.

Berthold HK, Gouni-Berthold I. Lipid-lowering drug therapy in elderly patients. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(9):877–93.

Savarese G, Gotto AM Jr, Paolillo S, D’Amore C, Losco T, Musella F, et al. Benefits of statins in elderly subjects without established cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(22):2090–9.

Szadkowska I, Stanczyk A, Aronow WS, Kowalski J, Pawlicki L, Ahmed A, et al. Statin therapy in the elderly: a review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(1):114–8.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Development and validation of the patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (patd) questionnaire. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(1):51–6.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ”Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, Murnion BP, Dent J, Bajorek B, et al. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28(4):182–8.

Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Blyth FM, Travison T, Rogers K, Naganathan V, et al. Statin use and clinical outcomes in older men: A prospective population-based study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(3):e002333.

Perreault S, Blais L, Dragomir A, Bouchard MH, Lalonde L, Laurier C, et al. Persistence and determinants of statin therapy among middle-aged patients free of cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(9):667–74.

van Duijn HJ, Belo JN, Blom JW, Velberg ID, Assendelft WJ. Revised guidelines for cardiovascular risk management time to stop medication? A practice-based intervention study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(587):e347–52.

Modig S, Kristensson J. Kristensson Ekwall A, Rahm Hallberg I, Midlöv P. Frail elderly patients in primary care—their medication knowledge and beliefs about prescribed medicines. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(2):151–5.

Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding statin use in america and gaps in patient education (usage): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(3):208–15.

Mann DM, Allegrante JP, Natarajan S, Halm EA, Charlson M. Predictors of adherence to statins for primary prevention. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21(4):311–6.

Reaume KT, Erickson SR, Dorsch MP, Dunham NL, Hiniker SM, Prabhakar N, et al. Effects of cerivastatin withdrawal on statin persistence. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(7):956–61.

Stack RJ, Elliott RA, Noyce PR, Bundy C. A qualitative exploration of multiple medicines beliefs in co-morbid diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabet Med. 2008;25(10):1204–10.

Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006544.

Bernal DDL, Bereznicki LRE, Peterson GM. With great power comes great responsibility. Med J Aust. 2014;200(5):321.

Kon RH, Russo MW, Ory B, Mendys P, Simpson RJ Jr. Misperception among physicians and patients regarding the risks and benefits of statin treatment: the potential role of direct-to-consumer advertising. J Clin Lipidol. 2008;2(1):51–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Michele Thai who contributed to the data collection.

Funding

The authors received no sponsorship or funding for this study. Danijela Gnjidic is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Early Career Fellowship. Sallie Pearson is a Cancer Institute NSW Career Development Fellow.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Katie Qi and Emily Reeve have contributed equally to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, K., Reeve, E., Hilmer, S.N. et al. Older peoples’ attitudes regarding polypharmacy, statin use and willingness to have statins deprescribed in Australia. Int J Clin Pharm 37, 949–957 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0147-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0147-7