Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to evaluate medication use pattern in a university tertiary hospital in the Sultanate of Oman. Setting The study was conducted at the Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) and the SQUH Family and Community Medicine clinic (FAMCO), Muscat, Sultanate of Oman during 7th to 25th June 2008. Method The medication use pattern was evaluated in women attending FAMCO and the standard antenatal clinics at the hospital. Women were interviewed in different gestational ages using a structured questionnaire. The Electronic Patient Record (EPR) was reviewed to acquire additional information on medication use. Medications were classified according to the US FDA risk classification. Main outcome measure Medication used including prescribed medications, OTC medications, or herbal treatment during the current pregnancy and 3 months prior to conception. Results The study included a total of 139 pregnant mothers with an overall mean age of 28 ± 5 years ranging from 19 to 45 years. There was a slight overall reduction in the medication use including prescribed medications. However, there was a significant increase in utilization of vitamins and supplements (84–95% vs. 12% in the 3-months prior, P < 0.001) as well as herbal preparations (16–19% vs. 7% in the 3-months prior, P = 0.011) throughout pregnancy (P < 0.010). The use of category A medications increased in all trimester (43–52% vs. 13% in the 3 months prior, P < 0.010) while a reduction in the use of category C (for first and third trimester, P < 0.050) and D medications was seen. A reduction in the use of teratogenic drugs in all trimesters (P < 0.010) was also observed. Conclusion The prescribing of vitamins and minerals was optimal. However, the common use of herbal supplements observed warrants special attention due to their unknown risks. The conclusions should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of the findings on practice

-

Despite the low utilization of teratogenic medications, the use of medications in pregnancy is very common in Oman.

-

The common use of herbal supplements in pregnant women in Oman warrants special attention due to the limited information on adverse effects.

-

It is essential for healthcare providers to acquire the latest evidence regarding the potential benefits or harm associated with both medication and herbal use during pregnancy.

Introduction

Medication use during pregnancy has always created a challenge in antenatal care due to the potential foetal risk associated with the use of medications [1]. Pregnancy complaints may range from minor ailments such as indigestion, nausea and vomiting to more serious or chronic conditions such as hypertension or autoimmune disorders. This makes it extremely challenging to prescribe and balance the risk of under treating pregnant women with chronic conditions against exposing the foetus to unknown harm [2]. To improve safe prescribing in pregnancy, a number of systems have been used to classify foetal risk. These include the Swedish [3], the Australian [4], as well as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA-US) risk classification systems [5]. The FDA classification system consists of 5 main categories: (A, B, C, D, and X), where classes D and X are labelled as hazardous in pregnancy [5].

Most published literature that discuss medication use in pregnancy are conducted in the US [6], Australia [7] and Europe [8–10], with few studies undertaken in the developing world [11–13]. To our knowledge, there are currently no published studies to date that have looked into the pattern of medication use in pregnancy in Oman. For this reason, existing data may have little relevance to the current setting for pregnant women in Oman.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to examine the pattern of medication use in a tertiary hospital in the Sultanate of Oman including prescribed medications, over the counter (OTC) products, vitamins and minerals as well as herbal and complementary treatments. In order to enhance safe prescribing practises, this information will be used to provide recommendations to prescribers and other health-care providers.

Method

The study was conducted at the Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) and the SQUH Family and Community Medicine clinic (FAMCO), Muscat, Sultanate of Oman during 7th to 25th June 2008. Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, SQUH. Women who were attending FAMCO and the standard antenatal clinics at the hospital were eligible to participate in the study. The women were entitled regardless of their age, gestational age or educational status. Oral consent was taken from all the women eligible to enrol in the study. The interview took place while women were waiting for their regular antenatal check-ups.

Sample size

A sample size of 122 was calculated to detect a 10% difference of overall medication use at the 5% significant level between the 3-months prior and the first trimester (power = 0.9). To allow for drop-outs and losses to follow-up, the study increased its sample size by about 15% to 139.

Data collection

Subjects were interviewed by a single interviewer (IMA—first author) using a structured questionnaire developed by the research team. The questionnaire included patient demographics (e.g., age, educational status, employment status), previous medication usage including prescribed medications, OTC medications, or herbal treatment; and obstetric factors (previous pregnancies, pregnancy losses, and contraception usage) during the current pregnancy and 3 months prior to conception.

The questionnaire was piloted prior to the study on patients attending the antenatal clinics at the SQUH and modifications made as necessary. During the interview the researcher (IR) used pictures of drug packaging and pills of common drugs prescribed to help patient identify medications used earlier.

The Electronic Patient Record (EPR) was reviewed by the authors to acquire additional information on medication use and to confirm participants’ demographics. Women were interviewed in different gestational age; therefore the analysis was done according to the trimester. First trimester was defined as 0–13 weeks, second trimester was defined as 14–27 weeks, and the third trimester was defined as 28–42 weeks.

All prescribed and OTC medications (with the exception of herbal products) were classified according to the US FDA risk classification system using the following reference databases; Lexi-Comp on-line [14] and Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation by Briggs [15]. The FDA pregnancy labeling uses five categories—A, B, C, D, and X. When a medication was not listed in these references, it was given the category ‘unclassified’. If a medicinal product included multiple ingredients, the strictest FDA category was used, however, if one of the ingredients was not classified, then the medication was rated as ‘unclassified’. When a patient gave information on medication use and that medication was not recorded in the patient’s EPR or could not be identified by the researcher, it was given the category “unknown”.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were reported. Differences between the 3-months prior and the different trimesters were analyzed using McNemar’s χ2 tests. For continuous variables, means and standard deviations (±SD) were presented. An a priori two-tailed level of significance was set at the 0.05 level. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.1 [16].

Results

A total of 142 women were interviewed, most of which were in the third trimester. Three women were excluded because of incomplete medical record details. The demographics and gestational history of the included subjects is summarized in Table 1. Out of the 139 women included in the analysis, data from the 3-months prior to pregnancy and the first trimester were available for all 139 women, 130 women in the second trimester and 82 women in the third trimester. The overall mean age of the cohort was 28 ± 5 years ranging from 19 to 45 years old. The majority of women included were unemployed, with secondary school or higher education (Table 1).

Data on overall medication use is summarized in Table 2. There was a slight reduction in medication use throughout the pregnancy when compared to the 3-months prior to pregnancy period (48–49% (the 3 trimesters) vs. 51% in the 3-months prior to pregnancy). This was accompanied by a reduction in the use of prescribed medications in all trimesters compared to pre-pregnancy (41–43% vs. 45% in the 3-months prior). Although, an increase in the proportion of women taking OTC medications in the 1st trimester was observed compared to the 3 months prior (12% vs. 8%), the use of these medications remained more or less the same in the second and third trimesters (9 and 8%, respectively, vs. 8% in the 3-months prior). Noteworthy, was the increase in the use of vitamins and supplements (84–95% vs. 12% in the 3-months prior, P < 0.001), and herbal preparations (16–19% vs. 7% in the 3-months prior to pregnancy, P = 0.011) in all trimesters.

Medications used were stratified according to their pharmacological class (Table 3). Vitamin supplements (including folate, iron and multivitamin) and herbal preparations were the most frequently used throughout pregnancy (P < 0.010). Compared to pre-pregnancy, a threefold increase in the use of herbals was also observed with an estimated 18% of women taking herbal preparations at any point during their pregnancy. Out of 75% of women who were on folate supplement during the first trimester, only 8% of them were taking it during the 3 months prior to pregnancy (P < 0.010). Use of diabetic agents, antihypertensives, antibiotics and sinus/antihistamine agents was increased in the second trimester (P < 0.050). The use of antifungal, antacids and systemic-steroids was increased in the third trimester (P < 0.050). A notable reduction in the use of Ob/Gyn agents was observed in all trimesters (for first trimester, P < 0.050; for second and third trimesters, P < 0.010). Medications used from this class included chorionic gonadotropin, clomifene citrate, triptorelin, follitropin beta, norethisterone and combined contraceptive pills. An apparent increase in the use of analgesics in all trimesters compared to pre-pregnancy was noted.

Classification of medications according to the FDA pregnancy categories is summarized in Table 4. Overall, there was an increase in the use of category A medications in all trimesters (43–52% vs. 13% in the 3 months prior, P < 0.010). A reduction in the use of medications of categories C (for first and third trimester, P < 0.050) and D. Unclassified medication use was higher during pregnancy compared to the 3 months prior (14–20% vs. 8%; for second and third trimester, P < 0.050). Noteworthy was the decrease in the use of teratogenic drugs in all trimesters (P < 0.010)

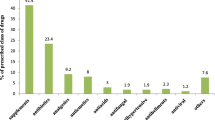

In the current study, 23.8% (n = 33) of women reported using herbal supplements during pregnancy. Table 5 demonstrates the Herbal supplements reported by women during pregnancy and their reported uses. Among the most common supplements taken were ginger (7.9%), honey (6.5%), thyme (5%) and green tea (3.6%). The most common uses included; flu and cold symptoms (9.4%), flatulence (6.5%), nausea (5%) or infection (4.3%).

Discussion

Knowledge of the safety of medication use in pregnancy has always been a concern for healthcare providers. This was the first study designed to provide information on the patterns of medication use during pregnancy in a tertiary hospital in Oman using the FDA classification. Due to the variability of methods used in reporting medication use in pregnancy in the literature and the health-care setting where these studies were conducted, it may be challenging to compare the results of this study with studies done elsewhere. Moreover, prescribing practises during pregnancy may vary between developing countries and the developed world [11, 13].

Our findings have demonstrated a high prevalence of overall use of medications during pregnancy compared to the pre-pregnancy period. The overall use of medication during pregnancy was comparable to the 3 months prior for both prescribed medications and OTC products. This is in agreement with the results of the MAP study [7]. A slight reduction in the overall use of prescription medications compared to the 3-months prior was noted; however, it was not statistically significant. This was accompanied by an apparent increase in the use of OTC medications in the first trimester which could have been explained by the increased use of anti-emetics.

A number of studies have reported analgesics among the most commonly prescribed medications in pregnancy [6, 23]. In a recent study among Pakistani women, analgesics including opioids accounted for 6.2% of all medications prescribed [11]. A similar trend towards increased to analgesics was observed. Similar to our findings, several studies have reported increased use of medications used to relief common ailments of pregnancy such as antacids, anti-emetics, [7, 23] and antifungals [7]. Our study has demonstrated an increased use of diabetic agents & antibiotics in the second trimester compared to pre-pregnancy. Other studies reported high use of diabetic agents during the whole duration of pregnancy [6], in particular insulin isophane [23]. Anti-infectives were reported among the most commonly dispensed medications during pregnancy [6, 23] which was mainly observed in our study in the third trimester.

In this study a combination of personal interviews using a structured questionnaire and extraction of information from patient medical records was used. We chose to interview women in the antenatal period to minimize the effect of the recall bias which is often associated with interviewing pregnant women after delivery [17, 18]. Previous work has shown that combining these two methods could result in under recording of medication use including vitamins and OTC medication [19]; however, this study has reported a high percentage of women using these preparations throughout the pregnancy. In this study, women were asked detailed questions on medication use and their specific indications. This has been shown to aid in improving recall to a large extent [20, 21]. This included information that is not usually documented by physicians in patient records such as; the use of OTC medication, herbal preparation, medication prescribed from other health institutions and to identify non-compliance.

A number of women included in this study were diagnosed with sickle cell disease, which could explain the trend towards increased use of analgesics including opioids. Additionally, a number of participants who were diagnosed with systemic lupus erythmatosis or had previous miscarriages were prescribed aspirin. The increased use of antacids, antifungals (11%, P < 0.05) and systemic steroids (9%; P < 0.05) in the third trimester was mainly to manage common ailments in pregnancy such as gastric reflux and vaginal thrush. In this study, 72–75% (P < 0.01) of women were taking folate supplements in the first and second trimesters compared to 8% in the 3 months pre-pregnancy. This is in agreement with a survey among Omani and Qatari women which showed that 88.7% of women take their folate supplements while only 13.2% of women have taken it during the pre-pregnancy period [22].

We evaluated exposure to both prescription and OTC medications according to the US FDA fetal risk classification system. Findings from our study have demonstrated a reduction in the use of medication in all trimesters for medications from the FDA pregnancy category C, D and X compared to pre-pregnancy. This reflects the awareness among prescribers, pharmacists and pregnant women to the safety concerns associated with medication use during pregnancy. Although studies have reported a higher prevalence for category X medications [6], our findings corroborate with Andrade et al. [23] which demonstrated a low prevalence for category D (3.4%) and category X medications (1.1%) during pregnancy. This variability in the results can be explained by methodological difference such as the units of observation used and medications analyzed, as well as differences in the health-care setting [6].

The prevalence of herbal use in this study corroborate those reported in the literature where frequency of use ranged between 7.1 and 56% [24–26]. Several studies have explored reasons for using herbs during pregnancy. These included management of pregnancy related conditions such as nausea and vomiting, digestive tract ailments [24–27] or for relaxation [24], all of which were reported in our study. In addition, more women in this study used herbs to manage infections including cough and cold (Table 5). Among the most commonly used herbs in this study were ginger, honey and thyme. The fact that these preparations, which are labelled as natural are exempt from FDA classification, could be misleading to patients and their health-care providers and could be posing a risk to both the foetus and the mother [6]. Therefore, health-care providers should be equipped with both the resources and the skills to provide patient education and counselling when it comes to using this class of medications.

The first limitation to this study was the reduction in power to detect differences especially at the third trimester as the sample size dropped from 139 to 80 due to drop-outs and losses to follow-up. Even though 18 days might seem a short study span, it represented a period required to recruit the 139 patients for this study. Due to its short duration, seasonal variation may have introduced another source of bias. However, Oman does not have 4 seasons like many European or North American countries but only 2 seasons. Hence, the authors believe that any notable differences will not be significant enough to bias the results. Although, the questionnaire of this study was similar albeit slight variations to that of Henry [7], however, external validation was not conducted. This study was conducted in a tertiary hospital in the capital of Oman which may limit the generalizibility of the results.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that the overall use of medication in particular prescription medications is very common. Reassuring was the low prevalence of teratogenic medications used in this study. The common use of herbal supplements observed in this study class warrants special attention due to the unknown risks that may be associated with their use. It is essential for healthcare providers to acquire the latest evidence regarding the potential benefits or harm associated with both medication and herbal use during pregnancy.

References

Kacew S. Fetal consequences and risks attributed to the use of prescribed and over-the-counter (OTC) preparations during pregnancy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;32(7):335–43.

Koren G, Pastuszak A, Ito S. Drugs in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(16):1128–37.

Berglund F, Flodh H, Lundborg P, Prame B, Sannerstedt R. Drug use during pregnancy and breast-feeding. A classification system for drug information. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1984;126:1–55.

Australian Drug Evaluation Committee. Prescribing medicines in pregnancy. 4th ed. Woden, Australia: Aust Gov Pub Unit; 1999.

Food and Drug Administration. Requirements on content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products. Fed Regist. 2006;71:3921–97.

Lee E, Maneno MK, Smith L, Weiss SR, Zuckerman IH, Wutoh AK, Xue Z. National patterns of medication use during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):537–45.

Henry A, Crowther C. Patterns of medication use during and prior to pregnancy: the MAP study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40(2):165–72.

Headley J, Northstone K, Simmons H, Golding J, the ALSPAC Study Team. Medication use during pregnancy: data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:355–61.

Lacroix I, Damase-Michel C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Prescription of drugs during pregnancy in France. Lancet. 2000;356:1735–6.

Olesen C, Sorensen HT, den Berg L, Olsen J, Steffensen FH, the Euromap Group. Prescribing during pregnancy and lactation with reference to the Swedish classification system: a population-based study among Danish women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:686–92.

Rohra DK, Das N, Azam SI, Solangi NA, Memon Z, Shaikh AM, Khan NH. Drug prescribing patterns during pregnancy in the tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:24.

Sharma R, Kapoor B, Verma U. Drug utilization pattern during pregnancy in North India. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:277–87.

Al-Humayyd MS, Babay ZH. Pattern of drug prescribing during pregnancy in Saudi women: a retrospective study. Saudi Pharm J. 2006;14(3,4):201–7.

Lexi-Drugs Online [database on the Internet]. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; 2008 [cited 30 July 2008]. Available from: http://online.lexi.com. Subscription required to view.

Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Summer JY. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. 6th ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 2002.

StataCorp. Stata: Release 11.1. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2010.

Tilley BC, Barnes AB, Bergstralh E, Labarthe D, Noller KL, Colton T, Adam E. A comparison of pregnancy history recall and medical records. Implications for retrospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(2):269–81.

Rockenbauer M, Olsen J, Czeizel AE, Pedersen L, Sřensen HT, the EuroMAP Group. Recall bias in a casecontrol surveillance system on the use of medicine during pregnancy. Epidemiology. 2001;12:461–6.

Bryant HE, Visser N, Love EL. Records, recall loss, and recall bias in pregnancy: a comparison of interview and medical records data of pregnant and postnatal women. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:78–80.

Mitchell AA, Cottler LB, Shapiro S. Effect of questionnaire design on recall of drug exposure in pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:670–6.

Forfar JO, Nelson MM. Epidemiology of drugs taken by pregnant women: drugs that may affect the fetus adversely. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14:632–42.

Hassan AS, Al-Kharusi BM. Knowledge and use of folic acid among pregnant Arabian women residing in Qatar and Oman. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2008;59(1):70–9.

Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:398.

Forster DA, Denning A, Wills G, Bolger M, McCarthy E. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy in a group of Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6:21.

Byrne MJ, Semple SJ, Coulthard KP. Complementary medicine use during pregnancy. Interviews with 48 women in a hospital antenatal ward. Aust Pharmacist. 2002;21:954–9.

Hepner DL, Harnett M, Segal S, Camann W, Bader A, Tsen L. Herbal use in parturients. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:690–3.

Hollyer T, Boon H, Georgousis A, Smith M, Einarson A. The use of CAM by women suffering from nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2(1):5.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the women who participated in the study, to the Pharmacy and the Obstetric/Gynecology departments who provided their support to this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Riyami, I.M., Al-Busaidy, I.Q. & Al-Zakwani, I.S. Medication use during pregnancy in Omani women. Int J Clin Pharm 33, 634–641 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9517-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9517-y