ABSTRACT

Purpose

Chlorogenic acid (CGA), the most abundant component in coffee, has exhibited many biological activities. The objective of this study is to assess preventive and therapeutic effects of CGA on obesity and obesity-related liver steatosis and insulin resistance.

Methods

Two sets of experiments were conducted. In set 1, 6-week old C57BL/6 mice were fed a regular chow or high-fat diet (HFD) for 15 weeks with twice intra-peritoneal (IP) injection of CGA (100 mg/kg) or DMSO (carrier solution) per week. In set 2, obese mice (average 50 g) were treated by CGA (100 mg/kg, IP, twice weekly) or DMSO for 6 weeks. Body weight, body composition and food intake were monitored. Blood glucose, insulin and lipid levels were measured at end of the study. Hepatic lipid accumulation and glucose homeostasis were evaluated. Additionally, genes involved in lipid metabolism and inflammation were analyzed by real time PCR.

Results

CGA significantly blocked the development of diet-induced obesity but did not affect body weight in obese mice. CGA treatment curbed HFD-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Quantitative PCR analysis shows that CGA treatment suppressed hepatic expression of Pparγ, Cd36, Fabp4, and Mgat1 gene. CGA treatment also attenuated inflammation in the liver and white adipose tissue accompanied by a decrease in mRNA levels of macrophage marker genes including F4/80, Cd68, Cd11b, Cd11c, and Tnfα, Mcp-1 and Ccr2 encoding inflammatory proteins.

Conclusion

Our study provides direct evidence in support of CGA as a potent compound in preventing diet-induced obesity and obesity-related metabolic syndrome. Our results suggest that drinking coffee is beneficial in maintaining metabolic homeostasis when on a high fat diet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Prevalence of obesity and overweight is progressively expanding worldwide and now affects more than 60% of adults in the US (1,2). Obesity has been identified as the major cause of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, various cancers, and other health problems, which lead to further morbidity and mortality. Emergence of metabolic syndrome incidence has resulted in an increased demand for new strategies that are safe and effective in preventing and treating obesity and obesity-associated diseases.

Coffee is one of the most widely consumed beverages, and an epidemiological study has shown coffee is inversely related to the risk of developing chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and cancer (3). Among the components in coffee, chlorogenic acid (CGA), an ester of caffeic acid and quinic acid (4), is the most abundant form of phenolic acid and major bioactive compound, which is also widely available in other plants, fruits and vegetables such as apples, pears, tomatoes, blueberries, and many others (5). In addition to its strong antioxidative property, the potential role of CGA in glucose and lipid metabolism has been explored in recent years. CGA has been reported to inhibit glucose-6-phosphate translocase 1, resulting in the reduction of glucose transport in the intestine (6). In the meanwhile, CGA enhances glucose uptake in isolated skeletal muscle cells and L6 muscle cell line (7,8) and improves glucose tolerance in db/db mice (9), indicating its potential antidiabetic activity. In addition, CGA significantly decreased plasma and liver lipid levels in (\( fa \)/\( fa \)) Zucke rats and rats fed a high-cholesterol diet (10,11). Using a fat enriched diet containing 37% fat calorie and 0.02% of CGA, Cho and colleagues (12) showed a reduced weight gain of ICR mice by 16% (40.05 g vs 47.7 g for high fat diet control without CGA). These studies suggest that CGA may exert a beneficial influence on metabolic diseases. The current study investigates the preventive and therapeutic activity of CGA in mice fed a HFD. Special attention was paid to the CGA effect on obesity-related liver steatosis and insulin resistance and the underlying molecular mechanism. Our results demonstrate that CGA significantly blocked diet-induced weight gain but did not affect body weight or fat mass in obese mice. In both prevention and treatment studies, CGA suppressed hepatic steatosis, suppressed obesity-related inflammation and improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Our results provide critical information regarding the beneficial effects of CGA in managing obesity and obesity-associated metabolic disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Chlorogenic acid (CGA) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan). The TRIZOL reagent and the SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis System are from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit was from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). PerfeCTa® SYBR® Green FastMix was acquired from Quanta BioSciences (Gaithersburg, MD). The Oil Red O solution was obtained from Electron Microscopy Science (Hatfield, PA). Infinity™ Triglycerides kit was purchased from Fisher Diagnostics (Middletown, VA). Total cholesterol assay kit was from Genzyme Diagnostics (Charlottetown, PE Canada) and NEFA-HR assay kits for free fatty acid was from Wako Bioproducts (Richmond, VA). The Mercodia Insulin ELISA kit was purchased from Mercodia Developing Diagnostics (Winston Salem, NC). A TUREtrack glucometer and test strips were purchased from Nipro Diagnostics, Inc. (Fort Lauderdale, FL). High-fat diet (F3282, 60% kJ/fat) was purchased from Bio-serv (Frenchtown, NJ). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA).

Animals and Treatment

All procedures performed on mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Two sets of experiments were carried out. In the first set, 6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice fed a HFD received two injections of CGA (100 mg/kg, intra-peritoneal) per week or carrier solution [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] for 15 weeks. In the second, obese mice (average body weight 50 g) were administrated CGA (100 mg/kg, intra-peritoneal) or DMSO twice per week for 6 weeks. Body weight and food intake were monitored weekly and animal body composition was determined at the end of the experiment using EchoMRI-100™ from Echo Medical Systems (Houston, TX).

Histochemical Analysis

After mice were sacrificed, the liver and epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) and brown adipose tissues (BAT) were collected, fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 6 μm. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed. Frozen sections (8 μm) were stained with 0.2% Oil Red O in 60% of isopropanol for 15 min and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline. A microscopic examination was performed and photographs were taken under a regular light microscope.

Lipid Extraction and Analysis

Hepatic lipids were extracted following an established procedure (13). Briefly, liver tissues were homogenized in phosphate buffered saline. Total lipids in 300 μl of homogenate were extracted by addition of 5 ml of chloroform-methanol (2:1, vol/vol) mixture. An aliquot of the organic phase was evaporated to dry and disolved in 1% Triton X-100. Hepatic cholesterol and triglyceride assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of Blood Lipid and Insulin Level

Blood samples were collected from fasted mice. Cholesterol, triglyceride, free fatty acid and insulin levels in the plasma were measured using commercial assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT) and Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT)

For GTT, mice were injected intraperitoneally with glucose at 2 g/kg body weight after fasting overnight. A small cut at the tip of a mouse tail was made at a selected time to give a small drop of blood which was directed absorbed into a test strip for determination of glucose level using a glucometer. For ITT, mice fasted for 4 h and blood glucose levels were measured after an intraperitoneal injection of insulin (0.75 U/kg) from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN).

Gene Expression Analysis by Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the mouse liver, pancrease, and white adipose tissues using the TRIZOL reagent or an RNeasy kit. Two micrograms of total RNA were used for the first strand cDNA synthesis, as recommended by the manufacturer. Real time PCR was performed using SYBR Green as an indicator using ABI StepOne Plus Real Time PCR system. PCR was carried out for 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Fluorescence was read during the reaction, allowing a continuous monitoring of the amount of PCR product. The data were normalized using GAPDH mRNA as an internal control. The primer sequences employed are summarized in Table 1.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). One-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the difference following Tukey post hoc test. All data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

CGA Prevented Animals from Development of High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Macrophage Infiltration in eWAT

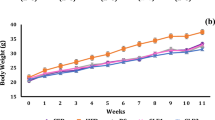

In the first set of experiments, the protective activity of CGA in diet-induced obesity was examined. As shown in Fig. 1a, 15-week HFD feeding significantly induced weight gain, and the average body weight in control animals is 48.2 ± 2.4 g. The average body weight of CGA-treated animals, on the other hand, is 31.6 ± 2.0 g at the end of the 15-week HFD feeding, slightly above the average body weight of chow-fed mice, but about 16 g less than that of HFD-fed control. Results from body composition analysis show that CGA blocked the increase of fat mass in HFD-fed animals without affecting lean mass (Fig. 1b). Compared to HFD-fed control animals, the CGA injection did not affect food intake during the 15-week feeding period (Fig. 1c). H&E staining of eWAT and BAT confirms lower level of fat accumulation in adipocytes in CGA treated mice, judging by the average size of adipocytes in eWAT (Fig. 1d–g) and the density of vacuole type structure in BAT (Fig. 1h–j). These results demonstrate that CGA blocks lipid accumulation in adipose tissue.

CGA prevented HFD-induced obesity in C57BL/6 male mice. Six-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were fed regular chow or HFD for 15 weeks. Mice were intraperitoneally injected by CGA (100 mg/kg, twice weekly) or carrier solution (DMSO) as the control. (a) Growth curve. (b) Fat and lean mass. (c) Food intake. (d) Average diameter of adipocytes in epididymal fat pad (calculated from 200 adipocytes from 4 separate slides). (e–g) H&E staining of white adipose tissue, scale bar: 500 μm. (h–j) H&E staining of brown adipose tissue, scale bar: 500 μm. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD of 5 animals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to HFD-DMSO group.

Macrophage infiltration in WAT is commonly observed in HFD-induced obesity (12,13). We examined the levels of adipose macrophages in control and CGA-treated mice using RT-PCR analysis. Figure 2 shows that HFD increased mRNA levels for macrophage specific marker genes F4/80, Cd68, Cd11c, and Cd11b by 9.2-, 20.2-, 9.6-, and 33.3-fold, respectively, compared to control animals fed regular chow. The transcript levels in the same group of macrophage marker genes in CGA-treated animals are significantly less than the HFD-fed control and similar to that of animals fed regular chow. These results suggest that CGA blocks HFD-induced chronic inflammation and macrophage infiltration in WAT.

Reduction of HFD-induced inflammation in epididymal white adipose tissue by CGA administration. Mice were sacrificed after 15-week of CGA injection. Epididymal adipose tissues were harvested, and total RNA was extracted. Relative mRNA levels of selected genes were determined by real time PCR. Inflammation is represented by the following selected gene expression: F4/80, Cd68, Cd11b, and Cd11c as well as cytokine Tnfα, and chemotactic factor gene Mcp-1 and its receptor Ccr2 in eWAT. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD, (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to HFD-DMSO group.

CGA Suppressed PPARγ-Associated Development of Fatty Liver in HFD-fed Mice

In addition to increased fat tissue, hepatic steatosis is also commonly observed in diet-induced obesity (14). Results in Fig. 3a–f show that HFD induced significant lipid accumulation in the mouse liver, as evidenced by the extensive vacuolation in H&E stained liver section and Oil Red O-stained massive lipid droplets. However, CGA-treated animals displayed significantly less fat accumulation in the liver, to levels similar to mice fed regular chow, which was also confirmed by measuring extracted liver triglyceride levels (Fig. 3g). The effects of CGA on blood concentration of triglyceride, free fatty acid and cholesterol were also examined. As shown in Fig. 3h–j, CGA significantly lowered triglyceride and cholesterol level but did not affect blood concentration of free fatty acid. Taken together, these results demonstrate that CGA markedly reduces hepatic lipid levels and improves plasma lipid profile.

CGA repressed HFD-induced hepatic steatosis and serum lipid levels. At the end of the 15-week of feeding, mice were sacrificed and livers were fixed with 10% neutrally bufferred fomalin. (a–c) Images of liver sections with H&E staining, scale bar: 500 μm. (d–f) Lipid level revealed by Oil Red O staining, scale bar: 500 μm. (g) Hepatic triglyceride levels. (h–j) Serum levels of triglyceride, total cholesterol and free fatty acid. *P < 0.05 compared to HFD-DMSO group.

Further studies were performed to evaluate the effect of CGA treatment on expression of genes involved in hepatic fat accumulation. Figure 4a shows that CGA markedly suppressed HFD-enhanced mRNA levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparγ1) (63%), Pparγ2 (52%), and its target genes including Cd36 (83%), fatty acid binding protein 4 (Fabp4, 47%), and monoacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (Mgat1, 99%). In addition, CGA treatment also increased mRNA levels of genes involving fatty acid metabolism including carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (Cpt1a, Cpt1b), and fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21) (Fig. 4b). CGA also inhibited HFD-induced hepatic inflammation, as evidenced by suppression of Cd68, Cd11b and Cd11c gene expression (Fig. 4c).

Effects of CGA on hepatic gene expression involved in lipid metabolism and inflammation. After mice were sacrificed at the end of 15-week of HFD feeding, liver tissues were harvested and hepatic total RNA was extracted. Real-time PCR analysis was utilized to evaluate relative mRNA level of selected genes which included (a) Pparγ1, Pparγ2 and target genes Cd36, Fabp4 and Mgat1. (b) Cpt1a, Cpt1b and Fgf21. (c) Macrophage marker genes F4/80, Cd68, Cd11b, and Cd11c. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD, (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to HFD-DMSO group.

CGA Suppressed Diet-Induced Hyperinsulinemia and Hyperglycemia in HFD-Fed Mice

To test whether CGA treatment improves obesity-associated insulin resistance, we compared fasting glucose levels and degree of glucose intolerance in the CGA-treated and DMSO-injected control mice fed a HFD. Levels of fasting glucose were much lower in CGA-treated mice than the HFD-fed control (134 ± 28 mg/dl vs. 204 ± 43 mg/dl). A glucose tolerance test (Fig. 5a) and the calculated area under the curve (AUC) (Fig. 5b) revealed a much higher clearance rate of intra-peritoneally injected glucose in CGA-treated animals, suggesting that CGA maintains glucose sensitivity. Protection against diet-induced insulin resistance was also demonstrated by an insulin tolerance test (Fig. 5c). Accordingly, CGA also ameliorated diet-induced hyperinsulinemia (0.7 μg/l vs. 5.3 μg/l) as shown in Fig. 5d, and dramatically inhibited an HFD-induced increase in mRNA levels of pancreatic Insulin1 and Insulin2 genes (Fig. 5e, f). These results validate that CGA protects animals against obesity-induced insulin resistance.

CGA improved hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia of animals fed with HFD. (a) Time dependent blood glucose level followed by IP injection of glucose (2 g/kg). (b) Area under the curve from glucose tolerance test. (c) Time dependent ratio of glucose concentration upon IP injection of insulin (0.75 U/kg). (d) Serum insulin levels at the end of the 15-week feeding with or without CGA administration. (e, f) Relative mRNA levels of Insulin1 and Insulin2 in pancreas. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD of 5 animals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to HFD-DMSO group.

CGA Treatment did not Affect Body Weight but Improved Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Mice

While the preventive effect of CGA on HFD-induced obesity, fatty liver and insulin resistance is clear, we question whether CGA has a therapeutic effect on obese mice. Diet-induced obese mice (average body weight 50 g) were divided into two groups and treated intraperitoneally with CGA (100 mg/kg,) or carrier solution (DMSO) twice weekly for 6 weeks. Results in Fig. 6a–c show that 6-week CGA treatment did not induce weight loss and the body fat mass and lean mass remained the same between CGA treated and control animals. H&E staining of eWAT shows that CGA treatment did not significantly change the size of adipocytes in WAT but slightly reduced the lipid droplets in BAT (Fig. 6d–g). Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity tests reveal that CGA treatment improved insulin sensitivity in obese mice, which is confirmed by amelioration of obesity-related hyperinsulinemia and reduction of calculated HOMA-IR. Taken together, these data demonstrate that CGA treatment improves insulin sensitivity in obese mice.

Six-week CGA treatment failed to cause weight loss in obese mice but improved insulin sensitivity. C57BL/6 obese mice fed a HFD were treated with CGA (100 mg/kg) or DMSO for 6 week. (a) Change of body weight. (b, c) Fat and lean mass measured before and after 6-week treatment. (d, e) H&E staining of white adipose tissue; scale bar: 500 μm. (f, g) H&E staining of brown adipose tissue; scale bar: 500 μm. (h) Time-dependent blood glucose level followed by IP injection of glucose (2 g/kg). (i) Time-dependent ratio of glucose concentration upon IP injection of insulin (0.75U/kg). (j) Serum insulin levels at the end of the 6-week CGA treatment; (k) HOMA-IR values calculated based on formula: (fasting insulin [μU/ml] × fasting glucose [mmol/l])/22.5. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD of 5 animals. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to DMSO group.

CGA Treatment Reduced Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Obesity-Related Chronic Inflammation in Obese Mice

Although CGA treatment did not induce weight loss in obese mice, results in Fig. 7e demonstrate that liver weight in CGA-treated animal was ~1.5 g, significantly lower than that of controls at ~2.5 g. In line with reduced liver weight, H&E and Oil red O staining of liver sections show less lipid accumulation in the liver of CGA-treated mice (Fig. 7a–d). Consistent with these results, CGA treatment of mice significantly reduced hepatic total cholesterol and triglyceride levels in obese animals (Fig. 7f, g). CGA treatment also reduced blood concentrations of free fatty acid, cholesterol and triglyceride levels (Fig. 7h–j).

CGA treatment reduced hepatic and blood lipids levels in obese mice fed a HFD. (a, b) Liver sections stained with H&E. (c, d) Oil Red O staining of liver sections showing less lipid accumulation in livers of CGA-treated animals compared with that of control. (e) Liver weight at the end of the 6-week treatment in obese mice. (f, g) Hepatic total cholesterol and triglyceride. (h-j) Serum levels of free fatty acid, cholesterol and triglyceride. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to DMSO-treated groups.

Similar to prevention study, mRNA levels of critical set of genes involved in lipid metabolism and inflammation were determined. Results in Fig. 8a show that CGA treatment decreased mRNA levels of Pparγ1 and Pparγ2, and their target genes Cd36, Fabp4 and Mgat1. In addition, CGA treatment also enhanced the Pparα level by 45% and increased its target genes peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (Acox1) and Fgf21 by 3.3~ and 1.8~ fold, respectively. Cpt1 gene transcription was not affected by CGA treatment (Fig. 8b).

Effect of CGA treatment on gene expressions in liver and white adipose tissue which were involved in lipid metabolism and inflammation. At the end of the 6-week CGA treatment of obese mice, animals were sacrificed and total RNA extracted from liver and white adipose tissue. (a) Relative mRNA levels of Pparγ1, Pparγ2 and their target genes Cd36, F abp4 and Mgat1. (b) mRNA levels of Pparα, Acox1, Fgf21, Cpt1a and Cpt1b. (c, d) mRNA levels of macrophage gene markers F 4/80, Cd68 and inflammatory factor genes Tnfα, Mcp-1 and Ccr2. Each data point represents the Mean ± SD, (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to DMSO group.

Consistent with improved hepatic lipid level, expression of macrophage marker genes such as chemoattractant Mcp-1 and its receptor C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (Ccr2), F4/80, Cd68 as well as Tnfα were also lower in CGA-treated animals (Fig. 8c). Similarly, mRNA levels of the same set of genes in eWAT also significantly reduced by CGA treatment (Fig. 8d). Taken together, these data suggest that CGA treatment of obese mice reduces HFD-induced chronic inflammation and improved hepatic steatosis.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have demonstrated that CGA is capable of effecting glucose and lipid metabolism as well as weight gain induced by HFD feeding (6,9–12). The current study comprehensively assesses both preventive and therapeutic activities of CGA on diet-induced obesity and obesity-associated metabolic syndromes, demonstrates the effect of CGA on obesity-related liver steatosis and insulin resistance, and explores underlying molecular mechanism. Utilizing C57BL/6 mice fed a HFD with 60% calorie from fats as an animal model and intraperitoneal injection as a route of drug administration, we examined the CGA activity in blocking HFD-induced weight gain and in reducing the body weight of obese mice. We demonstrate that CGA was effective in preventing HFD-induced weight gain (Fig. 1), inhibiting development of liver steatosis (Fig. 3), and blocking HFD-induced insulin resistance (Fig. 5). CGA treatment of obese mice did not yield weight loss, but improved insulin sensitivity (Fig. 6) and reduced lipid accumulation in the liver (Fig. 7). The beneficial effects were associated with CGA activity in blocking HFD-induced inflammation (Fig. 2), inhibiting diet-induced expression of Pparγ and its target genes in the liver, and increasing expression of genes responsible for lipid metabolism (Figs. 4 and 8).

The protective activity of CGA against HFD-induced obesity can be attributed to its antioxidant activity. Accumulating evidence suggests that chronic inflammation is closely associated with diet-induced obesity (15). HFD elevates production of reactive oxygen species in adipose tissue and boosts macrophage infiltration (16,17). We have previously shown that macrophage elimination by clodronate liposomes blocks HFD-induced obesity (18). We also recently demonstrated that HFD-induced obesity could be blocked by overexpression of superoxide dismutase 3 gene as a means to maintain redox homeostasis (19). CGA is a well-known anti-oxidant and capable of suppressing inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 activation and inhibition of the toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway (20,21) Consistent with these results, we observed that CGA treatment greatly reduced the mRNA level of macrophage marker genes in eWAT including F4/80, Cd68, Cd11b, Cd11c, Tnfa and Mcp-1 (Fig. 2), indicating a lack of diet-induced macrophage infiltration. Mechanistically, twice injection of CGA into mice per week provides sufficient antioxidants for animals to remove reactive oxygen species generated by consumption of lipids-enriched diet, thereby suppressing the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine gene induced by HFD, and consequently blocking fat accumulation and weight gain. Once the development of obesity is blocked, other metabolic parameters such glucose and insulin sensitivity maintain normal (Fig. 5). Results shown in Fig. 6a suggest that blockade of inflammation is not sufficient in reducing body weight in fats already accumulated in adipose tissue, indicating that antioxidants would not be effective in reducing body weight.

Results in Figs. 4 and 8 clearly show that CGA prevented and improved liver steatosis by inhibiting the PPARγ pathway. PPARγ, especially PPARγ2, is expressed highly in adipose tissue (22,23), promoting fatty acid uptake into adipocytes and adipocyte differentiation. Overexpression of hepatic Pparγ resulted in exacerbated liver steatosis (24). Conversely, liver and hepatocyte specific Pparγ knockout mice were protected against hepatic lipid accumulation (25–27). These studies suggest that PPARγ plays an important role in the development of hepatic steatosis. Our results show that HFD stimulated both Pparγ1 and Pparγ2 gene expression in the liver, concordant with HFD-induced hepatic lipid accumulation. Hepatic fatty acid transporter CD36 is a common target of PPARγ (28) and increased hepatic CD36 activity is critical for the development of steatosis in obesity (29–31). Consistent with previous reports (13,32–34), HFD significantly induced hepatic Cd36 expression, facilitating transport of long-chain fatty acids into liver. In both prevention and treatment studies, CGA dramatically reduced hepatic Pparγ mRNA level and inhibited expression of fatty acid transporter Cd36 and Fabp4 genes (Figs. 4a and 8a). In addition to blockade of fatty acid uptake, CGA also dramatically inhibited PPARγ-regulated Mgat1 expression. Mgat1 is involved in incorporation of fatty acids into triglyceride (35) and knockdown of this enzyme in the liver markedly reduced hepatic steatosis in diet-induced and genetic obese model (36). Therefore, by targeting the hepatic PPARγ pathway, CGA exerts its protective function against obesity-induced hepatic steatosis. Here, we quantify the change of PPARγ and its target genes by real time PCR. It should be noticed that the gene expression level is not necessarily equal to the protein level. Measurement in protein level will further confirm the effect of CGA on this pathway. In addition to the effect on Pparγ, previous studies have shown that CGA could enhance PPARα level in the liver and stimulate lipid utilization (11,12). In consistent with these earlier reports, our data also show that CGA promoted expression of Pparα and its target genes Acox1 and Fgf21 (Figs. 4b and 8b).

Several lines of evidence suggest CGA is a novel insulin sensitizer and capable of maintaining glucose hemostasis. Daily consumption of more than 3 cups of decaffeinated coffee containing high contents of CGA lowers the risk of developing type-2 diabetes by 30% (37). Clinical trials also verify that Emulin™, a patented blend of chlorogenic acid, myricetin, and quercetin, is able to chronically lower background blood glucose levels of diabetic patients (38). Here, our data demonstrate that CGA prevented HFD-induced hyperglycermia and hyperinsulinma (Fig. 5). Accordingly, CGA also improved insulin sensitivity in obese mice (Fig. 6h–k), in agreement with previous reports in db/db mice (9) and streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (39). Recent studies suggest that the inflamed adipose tissue in obesity triggers the development of obesity-related insulin resistance (40), indicating that reduction of tissue inflammation may be beneficial in obesity-related metabolic syndromes. In line with this report, RT-PCR analysis demonstrates that CGA inhibited diet-induced expression of macrophage marker genes (F4/80, Cd68, Cd11b, and Cd11c) and inhibited expression of pro-inflammatory mediator genes (Tnfα and Mcp-1) in the macrophages (Figs. 2 and 8). Attenuation of inflammatory phenotypes in adipose tissue and liver by CGA sensitizes peripheral tissues for the insulin response. In addition, Ong et al. (8) reported recently that CGA enables activation of AMPK and increase of glucose transport in skeletal muscle isolated from db/db mice and L6 skeletal muscle cells. In the meantime, CGA is capable of inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis by suppressing G6Pase activity (9). These potential effects may also contribute to the influence of CGA in obesity-related insulin resistance. The pathways for CGA-mediated benificial effects against HFD-induced obesity are illustrated in Fig. 9.

In summary, results presented in this study demonstrate CGA prevents mice from diet-induced obesity and obesity-related metabolic syndrome. CGA also improves liver steatosis, insulin sensitivity and reduces chronic inflammation in obese mice. These findings provide direct evidence in support of the potential health benefits of CGA in managing obesity and obesity-associated metabolic disorders. The next step for CGA research may be the development of improved CGA formulation to reach an effective CGA concentration in humans without toxicity and inconvenience.

REFERENCES

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766-81.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–7.

van Dam RM. Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Appl Phys Nutr Metab. 2008;33:1269–83.

Olthof MR, Hollman PCH, Katan MB. Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid are absorbed in humans. J Nutr. 2001;131:66–71.

Azuma K, Ippoushi K, Nakayama M, Ito H, Higashio H, Terao J. Absorption of chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid in rats after oral administration. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:5496–500.

McCarty MF. A chlorogenic acid-induced increase in GLP-1 production may mediate the impact of heavy coffee consumption on diabetes risk. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:848–53.

Prabhakar PK, Doble M. Synergistic effect of phytochemicals in combination with hypoglycemic drugs on glucose uptake in myotubes. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:1119–26.

Ong KW, Hsu A, Tan BK. Chlorogenic acid stimulates glucose transport in skeletal muscle via AMPK activation: a contributor to the beneficial effects of coffee on diabetes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32718.

Ong KW, Hsu A, Tan BK. Anti-diabetic and anti-lipidemic effects of chlorogenic acid are mediated by ampk activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1341–51.

Rodriguez de Sotillo DV, Hadley M. Chlorogenic acid modifies plasma and liver concentrations of: cholesterol, triacylglycerol, and minerals in (fa/fa) Zucker rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:717–26.

Wan CW, Wong CN, Pin WK, Wong MH, Kwok CY, Chan RY, et al. Chlorogenic acid exhibits cholesterol lowering and fatty liver attenuating properties by up-regulating the gene expression of PPAR-alpha in hypercholesterolemic rats induced with a high-cholesterol diet. Phytother Res. 2013;27:545–51.

Cho AS, Jeon SM, Kim MJ, Yeo J, Seo KI, Choi MS, et al. Chlorogenic acid exhibits anti-obesity property and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced-obese mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:937–43.

Ma Y, Huang Y, Yan L, Gao M, Liu D. Synthetic FXR agonist GW4064 prevents diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Pharm Res. 2013;30:1447–57.

Perlemuter G, Bigorgne A, Cassard-Doulcier AM, Naveau S. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathogenesis to patient care. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:458–69.

Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation. In Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome. Mediators Inflamm 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/289645.

Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–61.

Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–808.

Bu L, Gao M, Qu S, Liu D. Intraperitoneal injection of clodronate liposomes eliminates visceral adipose macrophages and blocks high-fat diet-induced weight gain and development of insulin resistance. AAPS J. 2013;15:1001–11.

Cui R, Gao M, Qu S, Liu D. Overexpression of superoxide dismutase 3 gene blocks high-fat diet-induced obesity, fatty liver and insulin resistance. Gene Ther. 2014;21:840-8.

Shan J, Fu J, Zhao Z, Kong X, Huang H, Luo L, et al. Chlorogenic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells through suppressing NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:1042–8.

Shi HT, Dong L, Jiang J, Zhao JH, Zhao G, Dang XY, et al. Chlorogenic acid reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis through inhibition of toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway. Toxicology. 2013;303:107–14.

Dreyer C, Krey G, Keller H, Givel F, Helftenbein G, Wahli W. Control of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by a novel family of nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1992;68:879–87.

Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspe E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, et al. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18779–89.

Yu ST, Matsusue K, Kashireddy P, Cao WQ, Yeldandi V, Yeldandi AV, et al. Adipocyte-specific gene expression and adipogenic steatosis in the mouse liver due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 1 (PPAR gamma 1) overexpression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:498–505.

Gavrilova O, Haluzik M, Matsusue K, Cutson JJ, Johnson L, Dietz KR, et al. Liver peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma contributes to hepatic steatosis, triglyceride clearance, and regulation of body fat mass. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34268–76.

Matsusue K, Haluzik M, Lambert G, Yim SH, Gavrilova O, Ward JM, et al. Liver-specific disruption of PPARgamma in leptin-deficient mice improves fatty liver but aggravates diabetic phenotypes. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:737–47.

Moran-Salvador E, Lopez-Parra M, Garcia-Alonso V, Titos E, Martinez-Clemente M, Gonzalez-Periz A, et al. Role for PPAR gamma in obesity-induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific conditional knockouts. FASEB J. 2011;25:2538–50.

Zhou J, Febbraio M, Wada T, Zhai Y, Kuruba R, He J, et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:556–67.

Kim Y, Park T. DNA microarrays to define and search for genes associated with obesity. Biotechnol J. 2010;5:99–112.

Miquilena-Colina ME, Lima-Cabello E, Sanchez-Campos S, Garcia-Mediavilla MV, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Lozano-Rodriguez T, et al. Hepatic fatty acid translocase CD36 upregulation is associated with insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia and increased steatosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2011;60:1394–402.

Koonen DPY, Jacobs RL, Febbraio M, Young ME, Soltys CLM, Ong H, et al. Increased hepatic CD36 expression contributes to dyslipidemia associated with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2007;56:2863–71.

Ma Y, Liu D. Activation of pregnane X receptor by pregnenolone 16 alpha-carbonitrile prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity in AKR/J mice. Plos One. 2012;7:e38734.

Gao M, Ma Y, Liu D. Rutin suppresses palmitic acids-triggered inflammation in macrophages and blocks high fat diet-induced obesity and fatty liver in mice. Pharm Res. 2013;30:2940–50.

Gao M, Ma Y, Cui R, Liu D. Hydrodynamic delivery of FGF21 gene alleviates obesity and fatty liver in mice fed a high-fat diet. J Control Release. 2014;185:1–11.

Cortes VA, Curtis DE, Sukumaran S, Shao XL, Parameswara V, Rashid S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in the AGPAT2-deficient mouse model of congenital generalized Lipodystrophy. Cell Metab. 2009;9:165–76.

Lee YJ, Ko EH, Kim JE, Kim E, Lee H, Choi H, et al. Nuclear receptor PPAR gamma-regulated monoacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (MGAT1) expression is responsible for the lipid accumulation in diet-induced hepatic steatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13656–61.

Huxley R, Lee CM, Barzi F, Timmermeister L, Czernichow S, Perkovic V, et al. Coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and tea consumption in relation to incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2053–63.

Ahrens MJ, Thompson DL. Effect of emulin on blood glucose in type 2 diabetics. J Med Food. 2013;16:211–5.

Karthikesan K, Pari L, Menon VP. Protective effect of tetrahydrocurcumin and chlorogenic acid against streptozotocin-nicotinamide generated oxidative stress induced diabetes. J Funct Foods. 2010;2:134–42.

Xu HY, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan Q, Yang DS, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–30.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Health (RO1EB007357 and RO1HL098295). We thank Ms. Ryan Fugett for proof-reading and English editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Gao, M. & Liu, D. Chlorogenic Acid Improves High Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Pharm Res 32, 1200–1209 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-014-1526-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-014-1526-9