Abstract

Pastoral theological scholarship on moral injury has not yet fully metabolized the liberative trajectory of pastoral theological discourse. To date, the care of those who come home from war remains largely depoliticized. This article argues that the wounds of war are personal and political and that care requires attending to the political dimension. The first section of the article sets the current pastoral theology conversation around moral injury within the historical context of the field around the care of veterans and the depoliticized nature of the clinical literature. The second section of the article argues the liberative trajectory of the field provides not only a basis for a robustly political response but also sets of relevant conceptual categories and care resources for veterans. The third section takes up Ryan LaMothe’s concept of “unconventional warriorism” as a basis for reimagining the political agency of soldiers and veterans. The article concludes by sketching out a broad proposal for the integration of politics and care for veterans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Several pastoral theologians have recently begun examining the spiritual struggles of soldiers and veteransFootnote 1 through the lens of moral injury (Graham, 2017; Moon, 2019; Ramsay & Doehring, 2019). This interest is timely—coming toward the end of America’s Global War on Terrorism and wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—and represents an important shift away from the notable silence of the field during and after the Vietnam War. Perhaps there were some, even many, who spoke out against the war. However, we have been unable to find any who attended to the care of the Vietnam veterans themselves. There are many potential reasons for this silence, which we explore below. Our contention, however, is that the recent pastoral theological scholarship on moral injury has not yet fully metabolized the liberative trajectory of the field of pastoral theology. In contrast with this trajectory, the care of those who come home from war remains largely depoliticized. The wounds of war are personal and political, and care requires attending to the political dimension (Kinghorn, 2012; Wiinikka-Lydon, 2017).

In this paper, then, we attempt that much-needed metabolization. In the first section, we examine the current pastoral theology conversation around moral injury and set it within the historical context of the field around the care of veterans and the depoliticized nature of the clinical literature. In the next section, we argue that the trajectory of the field provides not only a basis for a robustly political response but also sets of relevant conceptual categories and care resources. Finally, we conclude with a programmatic outline for bringing the wisdom of the wider field to bear within the context of the care of soldiers and veterans as well as naming key external resources and considerations to which pastoral theologians need also attend.

Pastoral Theology and the Depoliticization of Military Moral Injury

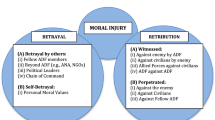

Moral injury first emerged in the clinical world as a conceptual and therapeutic response to the ways in which the moral dimensions of the trauma of war veterans exceeded the bounds of the conceptualization of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980) (even granting that the DSM-III included guilt). Jonathan Shay (1994), a United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) psychiatrist, first used the term moral injury to capture that excess in light of the experiences of betrayal the Vietnam veterans he worked with named. Shay’s conception focuses on the way that war corrupts character and how that corruption is linked to failures of leadership. Shay (2014) defines moral injury as “a betrayal of what’s right, by a person who holds legitimate authority (e.g., in the military—a leader) in a high-stakes situation” (p. 183). That betrayal could come at the hands of one’s immediate leadership or be tied all the way back to the actions or inaction of those holding political power. Shay’s account of moral injury built on the clear connections that Vietnam veterans made between their personal suffering and the politics and prosecution of the war itself.

More than a decade later, and many years into the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Brett Litz et al. (2009)Footnote 2 took up the concept of moral injury as a way to name and respond to the moral pain of veterans that is connected to their own agency or perceived failures and also results in some form of psychosocial impairment or maladaptive or destructive behaviors. Moral injury, as Litz frames it, involves a perceived moral violation that leads to painful moral emotions and cognitions with a resulting inability to navigate that pain toward meaning and connection. These violations include violations in which the self is perpetrator, with attendant moral emotions of guilt and shame, and/or violations as victim, with attendant moral emotions of anger and disgust (Currier et al., 2021).Footnote 3 Litz shifts the focus of moral injury away from the wider institutional (or even national) context with which Shay is concerned and zooms in on the individual agency of soldiers and veterans.

Pastoral Theology and Depoliticized Care

Larry Graham’s (2017) book Moral Injury: Restoring Wounded Souls is the first full-length treatment of moral injury by a pastoral theologian. At first glance, it might seem that Graham’s work actually sets the field up for a robustly political account of military moral injury. This would be in keeping with the overall oeuvre of Graham’s career that focuses on relational justice, signaling a shift away from the diagnosis-dependent aspects of the clinical pastoral paradigm. This shift moved the parameters of pastoral theology from just an individual to an individual’s community (and the social and political implications of communities). People come from communities, and return to communities; therefore, an analysis of communities and systems is paramount for pastoral theology. Graham conceptualizes moral injury as not just personal but as experienced on interpersonal and collective levels.

Moreover, Graham argues for a normalization of moral injury and strives to take it out of a pathologizing clinical context (even within the clinical context there is a strong bias against pathologizing moral injury). In Graham’s “normalized” account, moral injury flows out of moral dissonance and moral dilemmas. He doesn’t put it in these terms, but his work suggests something like a moral injury equivalent to the trauma-stress continuum (Dulmus & Hilarski, 2003). He even directly states that “there is no way to disconnect the personal and the public in understanding moral injury and fashioning healing responses to it” (Graham, 2017, p. 40). Unfortunately, Graham has mostly removed moral injury from its initial context among soldiers and veterans.Footnote 4 Thus, while he can imagine the integration of care and politics (or, at least, the public) with respect to thinking about moral injury and racism (the context of the previous quote), nowhere in Graham’s account does he trace a similar line of thinking with respect to thinking about war and moral injury.

Zachary Moon, another pastoral theologian and a former military chaplain writing about moral injury (and Graham’s student) ends up in a similar place but for different reasons. In Warriors Between Worlds: Moral Injury and Identities in Crisis, Moon (2019) argues that the problem of moral injury is a matter of moral dissonance between the moral orienting systems of military and civilian worlds. The solutions Moon offers, then, are focused on reintegration and how “warriors” (veterans) reintegrate into the civilian world. Moon seeks to do this culturally, intersectionally, and communally (elsewhere, he names this the “social-relation dimension” [2020]) and recognizes a kind of political responsibility of communities to care for those whom they have sent to war. Moon’s response, too, does not address military moral injury as a political problem. Moon seems averse to considering war to be the moral problem that moral injury is naming, and he categorically excludes it from the outset of his study as a kind of poison pill that risks alienating the very veterans he has in view. In Moon’s view, “[T]his tension is instructive for further work and may reveal how antiwar positions can limit access to communities who don’t share those values and beliefs” (2019, p. 16).Footnote 5

Nancy Ramsay (the current director of the Soul Repair Center at Brite Divinity School), Carrie Doehring, and others have offered up helpful care resources, most recently in an edited volume Military Moral Injury and Spiritual Care: A Resource for Religious Leaders and Professional Caregivers (Ramsay & Doehring, 2019). While many of these resources open up avenues for liturgical and communal modes of care, none of them offers a robustly political conception of either moral injury or its care. Given that this cuts against the grain of the general trajectory of the field (which we will get to in a moment), it seems appropriate to pause and ask, why? While there is no straightforward or obvious answer, we suggest this gap persists for two reasons. First, the field of pastoral theology developed largely under the influence of mainline Protestants in the wake of mainline Protestant opposition to Vietnam. The churches’ opposition to the Vietnam War, which generally came late, was largely accompanied by silence concerning soldiers and veterans, if not open blame and hostility, including toward military chaplains (Loveland, 2014, p. 22–25). Second, the field has historically been tied to clinical and psychological models and methods that prioritize the care of the individual. Even as Graham and others push back against the clinical conceptualization and treatment of moral injury, Litz’s highly individualistic account is generally their starting point.

The story of the development of diagnosis of PTSD highlights both the ways some clinicians ignored, shamed, and mistreated returning Vietnam veterans and how others showed up as powerful allies in the protest against the war and advocacy for the recognition and care of veterans (Scott, 1990). Even in the context of that story, it is not the case that mainline Protestant churches completely ignored or abandoned veterans. The National Council of Churches proved to be an early ally for the Vietnam Veterans Against the War as they began to form. The council even financially supported the organizational work that led to the codification and inclusion of post-traumatic stress disorder in the DSM-III in 1980 (Scott, 1990, p. 302). It would certainly be inaccurate to make sweeping statements about local church pastors and their treatment of Vietnam veterans.

What we can say is what did not happen at the level of academic discourse. In the wake of Vietnam, there was little to no attention paid to the care of veterans from within the field of pastoral theology. To be fair, pastoral theologians did not constitute themselves a “guild” until the creation of the Society for Pastoral Theology in 1985. As Nancy Ramsay relayed to us in an email: “If we had gathered a decade earlier in 1975, the War in Vietnam may well have been more present in our conversations. If the notion of military moral injury had been articulated or if a similar conflict had arisen, I think we would have made that a focus. Sadly concepts such as moral injury were not with us” (personal communication, March 18, 2022). We are grateful for Ramsay’s recollections on the guild in its early days both here and elsewhere (Hunter & Ramsay, 2017). While the guild may have not formally emerged until 1985, many of the people who were its antecedents had been in the academy for decades prior. And while Vietnam may have left the collective radar of those first members of the Society for Pastoral Theology, it was very much in the wider American consciousness.Footnote 6 There was widespread talk of post-Vietnam syndrome, and then PTSD, and then both as deeply personal and political wounds (Lifton, 1973/2005; Shatan, 1972, 1973). Perhaps it was simply an anti-war bias (no doubt the norm for mainline church clergy and seminary professors of the day) that accounts for pastoral theologians neglecting the deep wounds of Vietnam veterans and the ways those wounds were explicitly political.

We welcome the newfound interest in and scholarly attention upon the needs and concerns of veterans. The consequences of this interest and attention emerging quite late—after more than a decade into the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—are notable. The pastoral theological consideration of the situation of veterans has not occurred organically over the last 50 years, alongside the many developments in the field when it comes to feminist, Black, and womanist pastoral theology, for instance. Given that is the case, there is much in the pastoral theological conversation left unaccounted for in terms of both the development of the study of war trauma and in the application of the discipline’s own best insights within the context of the military and veteran communities. The interest in moral injury surged only after the publication of Litz’s work. Litz’s clinical conception of moral injury is ready-made for pastoral theological use within the clinical pastoral paradigm.Footnote 7 Clinical forms of knowledge still hold significant esteem within the guild, and it is no surprise that it is fundamentally Litz’s conception of moral injury as personal transgression that predominates in the work of Graham, Moon, and others. Even as they seek to move beyond it (as articulated above), they are beholden to it as their starting point.Footnote 8 So it is that moral injury has largely remained a highly individual and personal wound for veterans within the context of pastoral theology.

Politics and the Care of Moral Injury

It is in this context of a largely depoliticized account of moral injury that we suggest a much-needed repoliticization of care. On the surface, it would seem rather pedestrian to say the experiences and suffering of veterans is political. Working as they do to defend the polis, of course their work is political. In reality, though, America’s national narratives about its war making serve to depoliticize and then to privatize the trauma of veterans. The narratives grant meaning to the experiences and suffering of soldiers to the extent that they conform to a certain civil religious orthodoxy. They mask the reality of the moral suffering of soldiers behind the veil of personal sacrifice. America’s stories about war can affirm that war is horrible and that soldiers suffer because they do so pro nobis.

Recent pastoral theological work on moral injury inadvertently recapitulates this dynamic. Privatizing the trauma of veterans ensures both that America’s stories about war remain uninterrogated by the actual experiences of veterans and that veterans themselves often remain subject to these stories in the context of care. The moral and political landscape of American wars provides the context in which soldiers imagine and narrate what they do on the battlefield, even if the stories they tell stand in opposition to the story of American exceptionalism. If current pastoral theologians and caregivers proceed as if the larger context of war is irrelevant, then they, too, are liable to a similar judgment wrought in the wake of the critiques of liberation theologies. The care they provide may simply help veterans accommodate to the oppressive patriarchal dynamics of military service rather than bear witness to the liberating hope of the gospel.Footnote 9

While troubling these distinctions is precisely our point, historically, care has been conceptualized as “private,” of and proper to the oikos. The church is both oikos and polis. As pastoral theology developed as a discipline, it emerged as the study of an activity of the private sphere, the care work of pastors in the context of the church as oikos. The work of Black, feminist, and womanist pastoral theologians challenges this depoliticized orientation. We affirm this political trajectory of pastoral theology. Following Luke Bretherton, we see three dimensions to politics as a moral good. The first dimension refers to the good of the common life as such, the nature of the polis. The second dimension refers to the structures that give shape to the polis, statecraft (constitutions, laws, bureaucracy, etc.). Finally, politics includes the relational practices and prudential judgments that enact the good of association (Bretherton, 2019, pp. 32–34). To argue for the re-politicization of care, as we do, is to recognize the ways in which war, soldiering, and the aftermath of war for soldiers is bound up with all three dimensions of politics (or, in the case of the third dimension, the lack of political agency).

A political account of moral injury is attentive to war as an activity aimed (ostensibly) at preserving the polis as such (the first dimension), armies (and soldiers) as located within the bureaucracies of statecraft (the second dimension) and structurally subordinated to them and excluded from the relational domain of politics (the third dimension), relegated to live within the precarity of the permanent state of exception (Agamben, 1995/1998, 2003/2005). Soldiers are included within the polis through their exclusion and subordination. This political dynamic and the way it is narrated and oriented toward sacrifice (and justified theologically) parallels the ways that women were traditionally included within the polis through their exclusion from the oikos (state of nature) as wives and mothers (Tietje, 2021). Moral injury is best understood as located within this wider political context. We argue that a politically oriented conceptualization of moral injury and care stands in deep continuity with the overall trajectory of pastoral theology as increasingly attentive to contextualizing care within the larger political dynamics of exclusion and subordination, care not as accommodation to oppression but as a means of survival and even liberation.

Pastoral theology is not averse to the consideration of the personal and the political. The various 20th -century theologies “from below”Footnote 10 have forcefully asserted that “the personal is political.” Feminist theology (it is a feminist slogan, after all), Black liberation theology, womanist theology, Latin American liberation theology, queer theology, and other theologies “from below” have made significant contributions to the development of the field of pastoral theology. They have found deep resonances between the basic methodological stance of pastoral theology and theology “from below.” Pastoral theologians, from the outset, have seen their work as tending to persons in all their particularity (Anton Boisen’s living human document) and developing theologies that grow from the interplay of person(s) and theology.Footnote 11

Early pastoral theologians embraced ego psychology as offering liberating possibilities, even liberation from oppressive moral frameworks. However, psychology is not amoral, and over time it became clear that the psychological theories to which pastoral theologians were turning came with their own moral assumptions and problems. The overarching problem for these psychologies and the pastoral theologies that employed them was the extent to which they simply reflected the White, middle-class, and male perspective of the thinkers who had crafted them. That, at least, was the pushback pastoral theology faced beginning in the 1960s. Feminist and Black pastoral theologians began to question whether the frameworks they were employing, rather than provide a path for liberation, simply helped women and Black people accommodate to White male power in the midst of oppression. The time has come for a similar reappraisal of the soul care of soldiers and veterans.

A Liberative Trajectory

Feminist, Black liberation, and womanist pastoral theological conversations provide significant resources for the care of veterans. Moreover, the present state of the pastoral theological conversation is replete with untapped pastoral theological resources for thinking about war “from below,”Footnote 12 especially the turn to post-colonial (Lartey, 2013; McGarrah Sharp, 2019) and political pastoral theology (LaMothe, 2017a; Rogers-Vaughn, 2014, 2015). We intend to make explicit the latent resources within pastoral theology for thinking about war and the care of soldiers and veterans “from below,” from the perspective of their subordinated positionality. Much pastoral theological work has already been done to connect the personal (soul care) and the political (political and moral theology). Our modest hope is to bring the care of veterans into these wider conversations. In turn, we examine key Black, feminist, and womanist pastoral theological resources.

Before we do so, however, we want to pause and offer a caveat. We are speaking of soldiers (and veterans) who are (or were) situated within the U.S. military. We are aware of this institution’s death-dealing. We have very much been a part of it.Footnote 13 In other places we have imagined ways in which pastoral theology could think counterhegemonically in providing care to soldiers and veterans (Morris, 2020, 2021). Therefore, as we learn from Black, feminist, and womanist colleagues, we are keenly aware of the potential misuse and appropriation of caregiving competencies that are born from oppression and marginalization. Our goal, however, is to honor those communities by noting similar dynamics of exclusion and subordination for soldiers and veterans. These dynamics doubly impact soldiers who are also members of marginalized communities, Black women in particular (Fox, 2019; Melin, 2016). With that, we now explore, trace, and synthesize these liberative themes through the work of Edward Wimberly, Archie Smith, Bonnie Miller-McLemore, and Carroll Watkins Ali.

Black Liberation Pastoral Theology: Edward Wimberly and Archie Smith

Edward Wimberly wrote the first pastoral theology text from the perspective of Black experience. In Pastoral Care in the Black Church, Wimberly employs the four functions framework outlined by Clebsch and Jaekle (Hiltner’s healing, sustaining, and guiding with their addition of reconciliation) but focuses on sustaining and guiding as the two functions that have been most prevalent in the Black church. Wimberly (1979) writes:

The racial climate in America, from slavery to the present, has made sustaining and guiding more prominent than healing and reconciling. Racism and oppression have produced wounds in the black community that can be healed only to the extent that healing takes place in the structure of the total society. Therefore, the black church has had to find means to sustain and guide black persons in the midst of oppression. (p. 21)

For Wimberly, healing and reconciliation entail structural economic and political changes that have yet to be realized. The ongoing oppression of Black people makes “wounds almost irreparable” (p. 38). For White churches, by way of contrast, Wimberly writes:

Healing has been the dominant function in these white denominations largely because of the absence of economic, political, and social oppression. The healing model of modern pastoral care goes back to the early 1920s, and it was predominantly influenced by the one-to-one Freudian psychoanalytic orientation to psychiatry. To learn the methods and skills of the one-to-one healing model required economic resources and extensive clinical and educational opportunities to which many black pastors did not have access until very recently. (p. 22)

Black pastors, instead, drew on the resources they did have. The care of souls in the Black church has thus been more “corporate and communal.” Worship is at the heart of Black life, the Black church, and Black soul care. Wimberly offers a good outline of the history of the sustaining and guiding ministry of the Black church from slavery through the 1960s.

While Wimberly’s (1979) work precedes later womanist writers, his focus on the sustaining and guiding functions comports well with a key aspect of womanist ethics and care: survival.Footnote 14 Pastoral care in the Black church sustains and guides Black souls in the midst of ongoing oppression. Black pastors serve as “symbol(s) reflecting the hopes and aspirations of Black people for liberation from oppression in this life” (p. 20). Black pastoral care is not simply accommodation to oppression. It is the creation of conditions for survival in the midst of oppression.

While Wimberly treats the pastoral functions as conceptually distinct from the prophetic and political work of the Black church, from the outset it is clear that in reality no such distinction is possible. Wimberly himself acknowledges that healing is impossible because there is no path to personal healing for Black Americans apart from political healing. The care of souls in the Black church is intimately related to the Black church as an alternative space of political agency and the ongoing work of the Black church for civil rights. Current clinical and pastoral moral injury interventions, unintentionally, largely help soldiers and veterans adjust to political conditions that are unjust. With Wimberly, we affirm the need for pastoral care that empowers soldiers for survival, even and especially when political healing is not readily forthcoming. We turn next to Archie Smith Jr., who makes these connections much more explicit.

In The Relational Self: Ethics and Therapy from a Black Church Perspective, Smith (1982) builds on the work of Wimberly and others by explicitly putting Black liberation ethics into conversation with the therapeutic modalities in which he is trained. If healing for Black Christians demands political and social work, then ethics and therapy need to be brought to bear together in the work of the Black church for care and liberation. The two are, in reality, inseparable. Unfortunately, as Smith points out, sociological and psychological theoretical frameworks have been developed in support of social and political projects that may be fundamentally at odds with Black theology. Smith (1982) explains:

Sociologies or psychologies based upon and supportive of modern bourgeois individualism and materialism, or that fail to analyze the system and history of exploitative capitalism serve to delude both victims and social scientists while claiming to be value neutral. Social science and psychoanalysis premised on a different, but historically self-critical and liberating paradigm, will require the support of a different human subject and social order to be effective. (p. 25)

Because these sociologies and psychologies have been supportive of individualism and materialism, they have largely served “to adjust the individual within the established norms and structures of society, thereby strengthening the status quo” (Smith, 1982, p. 26). While psychology holds the potential for social criticism and change. Indeed, the task of psychology is to “free the inner life of the human subject from... internalized oppression” (p. 26). Yet, “it has often served to dull. . the potentially critical and emancipatory” (p. 26). The Black church, too, has often been viewed as “an opiate to militant action” (p. 26). What is needed, according to Smith, is a therapeutic and prophetic orientation. In this way, the Black church can support both “outer and inner transformation” (p. 27). Thus, Smith concludes that

[e]thics and therapy can find common cause in liberation struggles among oppressed groups that seek to build a sense of solidarity and respect for life where issues of self-contempt and demoralizing relational patterns are common. Both Christian social ethics and therapy are complementary when set within the context of liberation, reconciliation, and the relational self—expressed in the age old African proverb: “One is only human because of others, with others, and for others. (p. 27)

With a communal focus in mind, Smith argues for a relational paradigm that sets persons within a web of relations that links “private troubles. . with broad public issues” (p. 27). There is ever-present interconnection and dialectical exchange between inner and outer worlds. Indeed, “[M]orality is constituted through this web of dynamic relations” and is constitutive of our common moral life together.Footnote 15

Smith powerfully unites the personal and the political and argues for a dialectal relationship between ethics and therapy that puts both in the service of liberation. Smith’s work places pastoral psychology and therapy into conversation with Black liberation theology and points us toward the radical possibilities of doing pastoral theology “from below.” Pastoral theology can and does have a role to play in the liberation of the oppressed. Smith also provides us with the necessary critical tools for reorienting our work when the relationship between ethics and care has gone awry. He writes:

Therapy [or, spiritual care] may serve to adjust the individual within the limited horizon of the dominant ideology. Therapy in this case, may be seen as a delusional system, perpetuating the split between the person and the system. Therapy is then itself in need of emancipation. In order for therapy to serve its own implicit emancipatory interest, it needs to function in a different context and under social conditions that are more supportive of this interest.... In this light, it may be argued that the interest of liberation ethics in social transformation takes priority over an interest that takes for granted the assumptive world of individuals. (p. 153)

We suggest this is precisely the danger inherent with present clinical and pastoral theological conceptualizations and interventions around military moral injury. In cases where “therapy is then itself in need of emancipation,” Smith suggests it needs critical and dialectical engagement with liberation ethics. This is precisely what we have set out to do with respect to current pastoral conceptualizations of moral injury. With this in mind, we turn our attention to another movement to do pastoral theology “from below,” feminist pastoral theology.

Feminist Pastoral Theology: Bonnie Miller-Mclemore

We have just narrated the initial efforts toward a Black liberation pastoral theology. Feminist pastoral theology was a parallel development as feminism and feminist theology made its way into the pastoral theology conversation. The challenge, of course, as with the development of Black liberation pastoral theology, was that the overwhelming majority of pastoral theologians remained White men well into the 1990s.Footnote 16 This was certainly the case in the 1960 and 1970 s when both feminist and Black liberation theology were developing.

Bonnie Miller-McLemore stands out as one of the most significant pastoral theologians of the “second wave” of feminist pastoral theologians, not only as a feminist but as a leader in the discipline(s) on many fronts.Footnote 17 We want to articulate here two conceptual contributions she makes that unpack her synthesis within our trajectory. In turn, we examine her widely taken up expansion of Boisen’s living human document to the “living human web” and her addition of four core functions of pastoral care: resisting, empowering, nurturing, and liberating. The latter examination is central to our own constructive proposal.

Miller-McLemore’s “The Human Web: Reflections on the State of Pastoral Theology” (1993) points to both the centrality of care as the focus of pastoral theology and also the ways in which that care is now informed by “the study of sociology, ethics, culture, and public policy” (p. 367). Pastoral theology’s embrace of resources beyond the field of psychology represents a central aspect of the shift from Boisen’s “document” to Miller-McLemore’s (and Smith’s) “web.” Miller-McLemore directly ties this to the feminist slogan we have already embraced here: “the personal is the political.” The living human document implies the gaze of an external observer, one no doubt deeply embedded in the dominant societal power structures. The living human web is an image that highlights connectedness and its interdependence. If documents can be examined in isolation, a web implies an inextricable connection and embeddedness. Persons are always already enmeshed in social and political realities, notably systems of racist, capitalistic, and patriarchal oppression.

Crucially, if documents can be read, those embedded within the web must be empowered to speak for themselves. Miller-McLemore (2018) notes three significant trends in pastoral theology that lie behind this shift from the personal to the political: an increased interest in congregational studies, a new public theology, and the rise of liberation movements (p. 313). Boisen’s (1936/1971) turn to the living human document represents an important movement in theology away from abstraction. In its own right, it was a step toward doing theology “from below,” from the perspective of those who are suffering. The shift to thinking about the living human web further frames the work of the pastoral theologian in relation to the care of persons embedded within unjust social and political realities. Here, we have named this move as Miller-McLemore’s. She readily acknowledges her use of the web was already in the discipline’s ether; as we have seen, it was clearly already present in Smith’s work more than a decade earlier.

The turn to persons as embedded within the web thus evokes a new set of pastoral functions. Miller McLemore consolidates the additional pastoral functions suggested by feminist pastoral theology around the headings of resisting, empowering, nurturing, and liberating. Her summary of these functions bears quoting at length:

Compassionate resistance requires confrontation with evil, contesting violent, abusive behaviors that perpetuate underserved suffering and false stereotypes that distort the realities of people’s lives. Resistance includes a focused healing of wounds of abuse that have festered for generations. Empowerment involves advocacy and tenderness on behalf of the vulnerable, giving resources and means to those previously stripped of authority, voice, and power. Nurturance is not sympathetic kindness or quiescent support but fierce, dedicated proclamation of love that makes a space for difficult changes and fosters solidarity among the vulnerable. Liberation entails both escape from unjust, unwarranted affliction and release into new life and wholeness as created, redeemed, and loved people of God. (Miller-McLemore, 1999, p. 80)

If the personal is political, then the care of persons is political as well, and so too is our theorizing about care: “Pastoral care from a liberation perspective is about breaking silences, urging prophetic action, and liberating the oppressed. Pastoral theology is the critical reflection on this activity” (Miller-McLemore, 1999, p. 91). The work of feminist pastoral theologians and feminist pastoral caregivers (as outlined by the tasks of resisting, empowering, nurturing, and liberating) is thus necessarily political. If such work does not challenge existing patriarchal structures, then it risks unwitting collusion with them. The care of the oppressed entails resistance to oppression. Given this resistance, and the struggle for survival implicit within resistance, we now turn our attention to another movement to do pastoral theology “from below,” womanist pastoral theology.

Womanist Pastoral Theology: Carroll Watkins Ali

Carroll Watkins Ali builds on and expands Seward Hiltner’s functions of pastoral care beyond healing, sustaining, and guiding. Throughout her text Survival and Liberation: Pastoral Theology in African American Context (1999), she convincingly argues that a Hiltnerian method is not sufficient for poor African American women and the communities they represent. Watkins Ali affirms shepherding as central for pastoral theology and in doing so evokes a more holistic image of the shepherd. If the clinical pastoral paradigm emphasizes pastoral care as care of the one versus the ninety-nine, Watkins Ali (and Black and feminist pastoral theologians) press us to see that the one is always embedded within the wider flock. For Watkins Ali, then, care in the context of the African American community is attentive to Black experience, especially that of poor Black women.

In light of the cultural context of Black women and their struggle for both survival and liberation, Watkins Ali adds three community-based functions to Hiltner’s classic functions: “nurturing,” “empowering,” and “liberating” (p. 9).Footnote 18 To nurture the community, one must have an ongoing commitment to provide care that empowers counselees to have the strength to face various struggles within their community. The function of empowering contains the insistence that the struggle for liberation and emancipation must come from the oppressed people themselves. Pastoral caregivers “[put] people in touch with their own power so that they are enabled to claim their rights, resist oppression, and take control of their own lives” (p. 121). Finally, the liberating function entails political action. It involves working together as a community to eliminate oppression. The significance of Watkins Ali’s work is her insistence that, to adequately care for a community of people, the caregiver must address the systemic forces of oppression that keep the community down.

By way of contrast, the care of soldiers and veterans has remained “privatized” even as the discipline has largely taken on a more public and political voice. There has been work to contextualize the care of veterans within the “congregation” rather than solely as a function of pastoral caregivers (Moon, 2015). But, such moves nonetheless remain tied to the pastoral rather than prophetic tasks of pastoral care (Tietje, 2018). Just as the care of Black folks necessitates the upending of systems of White supremacy, so too does the care of veterans require a wholesale reappraisal of the moral and political context of American war, the church’s relationship to the American empire, and the political realities of soldiering. We affirm Wiinikka-Lydon’s (2017) claim that moral injury stands as an inherent political critique. The personal trauma of war for soldiers bears witness to the larger moral and political problems at the heart of American war making. We are certainly not the first soldiers, chaplains, or scholars to beat this drum (Mahedy, 1986/2004). Nevertheless, the current discourse within pastoral theology around moral injury continues to leave public triumphalistic narratives about soldiers and the state unchallenged and in so doing reinforces the privatization of the war trauma of soldiers.

War veterans, even after they return, continue to be placed on the sacrificial altar of the nation in order to support narratives of American exceptionalism and justice. Their stories, their lives, and their bodies are sanitized behind narratives of soldiers as national heroes and saviors (Ebel, 2015). Their struggles, their suffering, and their trauma—if and when they are acknowledged—are cast out of the polis proper. Yet, the witness of theological movements “from below” is again and again that “the personal is the political.” Thus, the work of pastoral care with veterans can and should be informed by the work of feminist, Black, and womanist pastoral theologians.

An Illuminating Exception: Lamothe’s Unconventional Warriorism

Ryan LaMothe’s article on warriorism shows up as a notable exception to the overall trend in the field regarding the privatization and depoliticization of the care of soldiers and veterans. In his article “Men, Warriorism, and Mourning: The Development of Unconventional Warriors,” LaMothe (2017b) examines the phenomenon of warriorism in the U.S. military. This almost autoethnographic piece is situated within his recent body of work setting pastoral theology within (and against) the context of the corrosive elements of American exceptionalism. In LaMothe’s analysis, then, American service members are formed as “warriors” in the military, trained to inculcate and live by the warrior ethos.Footnote 19 The warrior ethos, he argues, is undergirded by a straightforward patriotism and faith in American exceptionalism. He contends that the disillusionment of warriors in the face of the many failures and fiascos of American power around the world should be read as a kind of grief that might lead to new insight, orientation, and action. He does this through an examination of the life and work of retired Marine Corps General Smedley Butler. He traces the shift in the life of Butler from loyal soldier to the disillusioned author of War Is a Racket and advocate for various egalitarian and democratic movements and reforms. He names this shift as one from being a conventional warrior, one who “obeys his military commanders and political leaders,” to an unconventional warrior, one who “is more critical, possessing a sense of duty toward the people and not merely the state” (2017b, p. 834).

LaMothe is not directly engaging the literature on moral injury, but it is certainly possible to bring together his analysis around the mourning of conventional warriors with Shay’s account of moral injury as betrayal. LaMothe’s work suggests a way for soldiers and veterans through which they might hold on to a vital center, their identity as “warrior,” even as their experience of political betrayal presses toward a new “unconventional” orientation. For his part, LaMothe remains skeptical of both warriorism as such (seeing it as inextricably entangled with American exceptionalism) and the likelihood of the emergence of very many unconventional warriors.

LaMothe’s work, a minority report in the field, presents a helpful addition to the liberative trajectory we have outlined. If, as we suggest, soldiering means crossing the threshold into a political space of exception, within which moral and political agency are attenuated, constrained, and in many ways oppressive, one version of a liberation reading might be that survival means making it to the end of one’s enlistment contract and liberation means being able to set aside one’s identity as soldier or “warrior,” in LaMothe’s terms. For many, this straightforward reading may be the one with which they most readily identify. LaMothe does not directly address the political conditions of soldiering, but the implications are embedded in his analysis. Even so, his work suggests an alternative—not a release, rejection, or escape, necessarily, from one’s identity as a soldier but a shift, turn, or, dare we say, a kind of moral re-formation. Both in the context of LaMothe’s own biography and the life of Smedley Butler this movement occurs, in large part, in the context of separation from service or retirement. While departure is not entailed by LaMothe’s account (although likely implied), it does beg the question of whether it is possible for LaMothe’s “unconventional warriors” to remain within the military. While the military happily employs unconventional warriors—special operations soldiers who operate with increased agency in austere environments to accomplish unconventional missions—LaMothe’s disobedient “unconventional warriors” are the kinds of soldiers the military happily retrains, punishes, or separates from service. Is there, then, a place for “unconventional warriors” within the military? We think so, but not as “lone rangers” like Butler.

With these potential “unconventional warriors” within the military in mind, there are important threads from the liberative trajectory and LaMothe’s account of unconventional warriors that we’d like to carry forward, bring together, and extend. The liberative trajectory opens the door for contextualizing the moral trauma of soldiers (and veterans) within the wider moral and political context of their service. It helps us imagine care unbounded from the privatized clinical pastoral context. Key figures like Wimberly, Smith, Miller-McLemore, and Watkins Ali, taken together, suggest possibilities for life-giving care to emerge, not as a means of reinforcing the status quo of soldierly agency but as a means of empowerment within those constraints and of resistance to injustice. This implicates caregivers in the need for political work for liberation. LaMothe’s work suggests that this liberative work need not entail the rejection of soldiering per se (or even loyalty to one’s fellow soldiers or fellow citizens) but the abusive ways it is bound up with American exceptionalism and a form of life within a permanent state of exception.

Both the liberative trajectory and LaMothe can be supported by an even more explicitly political turn. Wimberly, Smith, Miller-McLemore, Watkins Ali, and LaMothe, each in their own way speak, to the need for political work. We suggest a form and direction that might take. LaMothe’s limitation, in particular, is that, in homing in on Butler, “unconventional warriors” are set up as exceptional figures. Butler is a general, not a lower enlisted “joe.” He is a solitary figure. Politics, at least at its most basic level (the third dimension described above), is relational and grounded in relational practices. It involves conflict and conciliation around goods held in common. If “unconventional warriorism” has any chance of emerging as a form of life within the context of the military, it is not in the context of lone, high-ranking dissenters.

While all soldiers are subject to life within the state of exception, we imagine a kind of bottom-up relational politics that is attentive to the experiences of those within the military who are most subjected to the harmful dynamics of soldiering: the low-ranking, women, and soldiers of color. At present, this is largely out of bounds. While much is made about the limits on the political speech of soldiers, the more fundamental constraint of soldierly agency is the limit on association and assembly. So it is that the possibilities of relational politics are severely inhibited from the outset. While naming and unpacking these limitations is essential for any adequate description of soldierly agency, we hasten to rejoin that these “realities” are contingent and historical. As such, they are subject to political interventions. We suggest unionization, in particular.

There are no easy answers. We are not suggesting unionization as a panacea but rather lifting it up as an example of the kind of radical re-imagination we are after. The civil-military distinction (and the legal regimes enforcing the military as a state of exception) is, in large part, an attempt to banish politics (and the partisan aspects of statecraft) from the prosecution of war. We fully recognize the danger of unleashing partisan politics in the context of the American military. Unionization, we think, would open up space for soldiers to live and breathe as political animals in the context of politics as relational practices. There are real political hurdles, but recent movements are heartening. Although federal law currently prohibits the unionization of soldiers (10 U.S. Code § 976), no such prohibition exists for National Guard soldiers on State active duty. The Department of Justice recently affirmed this gap in light of several recent pushes for unionization (Monroe, 2022; Winkie, 2022). We contend that churches and their chaplains could be key partners and advocates in the effort. Chaplains, in particular, are positioned to engage directly in political work, organizing and advocating for forms of political life for themselves and for their soldiers that disrupt the legal frameworks, national civil religious narratives, formation processes, and troubling lived realities of life as a soldier. Chaplains cannot do this work alone but must be supported by robust networks of American churches.

Conclusion: A Modest Proposal

In this paper, we have argued that the current pastoral theological conversation around military moral injury has not fully metabolized the political and liberative trajectory of the discipline. This larger movement within pastoral theology away from the focus on the individual needs to be brought to bear in the context of the care of veterans. If moral injury is indeed a political wound, then what is needed is nothing less than political healing. Along with Black, feminist, and womanist pastoral theologians, we argued that those who care for veterans should attend to nurturing and empowering them, as well as joining with them in resistance “from below.” Care, then, includes survival in the midst of oppression and not simply accommodation to it, but it must also include participation in the struggle for liberation. While liberation for some may mean a rejection of soldiering as such or of one’s own service as soldier, we argued it need not entail that and looked to LaMothe’s “unconventional warrior” as a possible exemplar for continued service.

We conclude by suggesting the following elements for future pastoral theological work around the care of soldiers and veterans.

-

1)

The care of soldiers and veterans requires the recognition that the vocation of soldiering is contested terrain within the Christian tradition and is bound up with various accounts of the relation of church/world, church/state, just war, pacifism, etc., i.e., the contested nature of politics in the first dimension and the nature and form of the polis itself.

-

2)

The care of soldiers and veterans requires a thick description of the constrained and burdened moral and political agency of soldiers within the state of exception, to include their location within the American civil religious sacrificial economy (and the role of Christian theology), the way that soldiering and war are bound up with masculinity (Tietje, 2021), and the ways these dynamics land very differently for soldiers who live at different intersections of race, class, gender, and rank. That is to say, a description of soldiering in terms of statecraft (or politics in the second dimension) and the limitations on relational politics (the third dimension) is necessary.

-

3)

Within this context, then, the functions of pastoral caregivers should be extended analogously to the ways that Black, feminist, and womanist pastoral theologians have suggested: survival, empowerment, resistance, liberation.

-

4)

If these are the functions, then military and VA chaplains and church leaders cannot help but enter into the fray of both relational and statecraft politics as allies with and advocates for soldiers and veterans. There is a bond based on solidarity that chaplains develop with soldiers and veterans, even those they did not directly serve alongside. It is by entering into this fray that chaplains can support soldiers and veterans (Morris, 2021).

Notes

We use the term soldiers throughout this paper to refer to current U.S. service members of any branch, including those in the National Guard and Reserves. We use the term veteran to refer to service members who have separated from service in any branch or component and under any condition of discharge.

The authors are all VA providers/researchers, with the exception of William Nash, who at the time was a psychiatrist in the United States Marine Corps.

This avoidance of context is surprising as Graham (2015) states, while summing up his career, “[A]s pastoral theologians, we are already well aware of the physically embodied and socially embedded nature of our lives. To a greater or lesser degree, all of our pastoral theological paradigms are sensitive to the embodied and embedded character of human life in the world” (p. 177).

Of course, the equal and opposite point can be forcefully made. Not taking a stand against a particular war can also be costly. We suspect this would be the rejoinder of the likes of Rita Brock and Gabriella Lettini (2012).

It is almost impossible to overstate the social, cultural, and political impact of the Vietnam war, even well into the 1980s. While there was never a true political reckoning over Vietnam, there was certainly an ongoing and evolving cultural reckoning, which was well underway in the 1980s. The blockbuster war films of the era are illustrative. The most famous line from First Blood (Kotcheff, 1982) was Rambo’s question: “Sir, do we get to win this time?” In Uncommon Valor (Kotcheff, 1983), one of the characters says to a team of fellow veterans on their way to rescue some MIAs: “No one can dispute the rightness of what you’re doing.” Platoon was released in 1986 (Stone) and Full Metal Jacket in 1987 (Kubrick). These films provided a forum for both re-narrating a win (First Blood, Uncommon Valor) and recognizing the profound immorality and suffering of the war (Platoon, Full Metal Jacket). Throughout the 1980s, the “Vietnam vet” also emerged in film and other media as a trope, someone deeply wounded psychologically and often physically unkempt and unfit for society. Further cultural markers of the salience of the war and its ongoing impact on veterans can be seen in the inclusion of PTSD in the DSM-III (1980) and the completion of “the Wall,” the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in 1982. Again, with all this as backdrop, the lack of engagement by pastoral theologians at the time is surprising.

And yet, Litz himself describes his adaptive disclosure method as “ill advised” for chaplains, who are not psychotherapeutically trained, to utilize as it is an “intensive, totally secular, step by step manualized psychotherapy” (personal communication, February 2016).

Elsewhere, Graham (2015) notes that the clinical pastoral paradigm “is still the default paradigm organizing pastoral theology and care” (p. 174). We agree—especially as it relates to moral injury—and this is problematic.

We suggest that the challenge for military chaplains is exacerbated by the fact that they function within the very system that both valorizes its warriors while both medicalizing and individualizing their maladies (as precisely their maladies). There are legal, political, and biopolitical regimes that all but guarantee military chaplains provide pastoral care that brackets out any wider moral and political questions about war. Thus, it must be acknowledged up front that the care of soldiers and veterans (properly inflected by the wider moral and political context of America’s wars) remains a tall order. The very institutions where pastoral caregivers most directly attend to the soul care of America’s soldiers and veterans—the United States Department of Veterans Affairs and the United States Department of Defense—are the very institutions in which such care will be least welcomed. We believe that churches and other religious bodies bear much of the blame for having de facto ceded responsibility and authority over their clergy to the state.

This phrasing comes from the theological fragments of Dietrich Bonhoeffer during the early days of his imprisonment, possibly in late 1942. In an unfinished paragraph, Bonhoeffer (1997) writes: “We have for once learnt to see the great events of world history from below, from the perspective of the outcast, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed, the reviled—in short, from the perspective of those who suffer” (p. 17). This quote represents a rather significant turn in 20th-century theology. We do not mean to read Bonhoeffer or this quote as the sole fulcrum that turned theology in a new direction. But, this quote does capture a shift that was already well underway. Bonhoeffer is indeed influential among early Latin American liberation theologians in this regard (Gutiérrez, 1983/2004; Weidersheim, 2021). Below (and above) are prepositions. They orient something (or someone) in relation to something else (or someone else). In this quote, below is an orientation in relation to history, privilege, and power. Those below are those crushed rather than propelled by the forward march of history: “outcasts, suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed, the reviled.” Theology “from below” is theology “from the perspective of those who suffer.” The important work of liberation theologies has been to show that in Jesus God turns history on its head. The crucified God is at the heart of history. Salvation, then, is not an escape from history but God’s solidarity within history with the “crucified peoples of history” (Ellacuría & Sobrino, 1993; Sobrino, 1994). Theologies “from below” begin from the perspective of those who are oppressed and suffering.

The terminology “from below” is technically anachronistic as applied to early pastoral theologians, Boisen in particular.

We recognize that “from below” has largely been jettisoned in favor of “from the margins” or “from the periphery” because it is hierarchical imagery. With respect to the situation of soldiers, we think below is actually the most apt preposition precisely because soldiers are subject to patriarchal dynamics of subordination within the military hierarchy.

Of course, so have all American citizens, whether they know or acknowledge it or not.

Of course, womanism is focused not only on survival but also on well-being and thriving. Melanie Harris (2010, pp. 114–123) highlights seven virtues that promote survival, well-being, and thriving that women of African descent embody: generosity, graciousness, compassion, spiritual wisdom, audacious courage, justice, and good community/good accountability.

Smith’s work is thus a clear antecedent of Bonnie Miller-McLemore’s later “living human web.”

We recognize though, that many women were already at work shaping pastoral theology and practice. The literature in pastoral theology, as in any field, recognizes those who have the positions, power, and influence to publish. There are always others doing important work “from below.”

Further, building on our previous note, a potential frustration with any trajectory are those critical voices that are omitted. We are beginning with Miller-McLemore as she pulls our liberative threads in complementary ways, especially with respect to Smith. However, the groundbreaking work of Peggy Way should be acknowledged. We recognize her influence on the entire field and especially on Miller-McLemore.

This is done to create a more robust vision of care, not eradicate Hiltner’s work.

The U.S. Army’s Warrior Ethos is “I will always place the mission first. I will never accept defeat. I will never quit. I will never leave a fallen comrade.” LaMothe (2017b) contends that warriorism is a kind of masculine ideal in a warrior society. The sociological evidence suggests the connection between masculinity and war runs much deeper. Warrior society or not, men have traditionally filled the role of warrior in times of war (Goldstein, 2001).

References

Agamben, G. (1998). Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Trans: Stanford University Press. (Original work published 1995)D. Heller-Roazen.

Agamben, G. (2005). State of exception (K. Attell, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 2003)

American Psychiatric Association (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev.).

Boisen, A. (1971). The exploration of the inner world: a study of mental disorder and religious experience. University of Pennsylvania Press. (Original work published 1936).

Bonhoeffer, D. (1997). Letters and papers from prison. Touchstone.

Bretherton, L. (2019). Christ and the common life: political theology and the case for democracy. Eerdmans.

Brock, R. N., & Lettini, G. (2012). Soul repair: recovering from moral injury after war. Beacon Press.

Currier, J., Drescher, K. D., & Nieuwsma, J. (Eds.). (2021). Addressing moral injury in clinical practice. American Psychological Association.

Dulmus, C. N., & Hilarski, C. (2003). When stress constitutes trauma and trauma constitutes crisis: the stress-trauma-crisis continuum. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 3(1), 27–36.

Ebel, J. (2015). GI messiahs: Soldiering, war, and american civil religion. Yale University Press.

Ellacuría, I., & Sobrino, J. (Eds.). (1993). Mysterium Liberationis: fundamental concepts of liberation theology. Orbis Books.

Fox, N. A. (2019). Aretē: “We as black women. Journal of Veteran Studies, 4, 58–77.

Goldstein, J. (2001). War and gender. Cambridge University Press.

Graham, L. K. (2015). Just between us: big thoughts on pastoral theology. Journal of Pastoral Theology, 25(3), 172–187.

Graham, L. K. (2017). Moral injury: restoring wounded souls. Abingdon Press.

Gutiérrez, G. (2004). In R. Barr (Ed.), The power of the poor in history. Trans.). Wipf & Stock. (Original work published 1983).

Harris, M. (2010). Gifts of virtue, Alice Walker, and womanist ethics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hunter, R. J., & Ramsay, N. J. (2017). How it all began and formative choices along the way: personal reflections on the Society for Pastoral Theology. Journal of Pastoral Theology, 27(2), 98–109.

Jinkerson, J. (2016). Defining and assessing moral injury: a syndrome perspective. Traumatology, 22(2), 122–130.

Kinghorn, W. (2012). Combat trauma and moral fragmentation: a theological account of moral injury. Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, 32(2), 57–74.

Kotcheff, T. (Director) (Ed.). (1982). First blood [Film]. Anabasis N. V. Cinema 84; Elcajo Productions.

Kotcheff, T. (Director) (Ed.). (1983). Uncommon valor [Film]. Brademan-Self Productions; Sunn Classic Pictures.

Kubrick, S. (Director) (Ed.). (1987). Full metal jacket [Film]. Warner Brothers; Natant; Stanley Kubrick Productions.

Lartey, E. Y. (2013). Postcolonializing God: an african american theology. SCM Press.

LaMothe, R. (2017a). Care of souls, care of polis: toward a political pastoral theology. Cascade Books.

LaMothe, R. (2017b). Men, warriorism, and mourning: the development of unconventional warriors. Pastoral Psychology, 66, 819–836.

Lifton, R. J. (2005). Home from the war: learning from Vietnam veterans. Other Press. (Original work published 1973).

Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 695–706.

Loveland, A. (2014). Change and conflict in the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps since 1945. University of Tennessee Press.

Mahedy, W. P. (2004). Out of night: The spiritual journey of Vietnam vets. Radix. (Original work published 1986).

McGarrah Sharp, M. (2019). Creating resistances: Pastoral care in a post-colonial world. Brill Press.

Miller-McLemore, B. (1993, April 7). The human web: Reflections on the state of pastoral theology. Christian Century, 110, 366–369.

Miller-McLemore, B. (1999). Feminist theory in pastoral theology. In B. Miller-McLemore & B. Gill-Austern (Eds.), Feminist and womanist pastoral theology (pp. 77–94). Abingdon.

Miller-McLemore, B. (2018). The living human web: a twenty-five year retrospective. Pastoral Psychology, 67, 305–321.

Melin, J. (2016). Desperate choices: why black women join the U.S. military at higher rates than other racial and ethnic groups. New England Journal of Public Policy, 28(2), 1–14.

Monroe, R. (2022, April 26). The National Guard soldiers trying to unionize. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-the-southwest/the-national-guard-soldiers-trying-to-unionize. Accessed April 28, 2022.

Moon, Z. (2015). Coming home: Ministry that matters with veterans and military families. Chalice Press.

Moon, Z. (2019). Warriors between worlds: Moral injury and identities in crisis. Lexington Books.

Moon, Z. (2020). Moral injury and the role of chaplains. In B. Kelle (Ed.), Moral injury: a guidebook for understanding and engagement (pp. 59–69). Lexington Books.

Morris, J. (2020). Veteran solidarity and Antonio Gramsci: Counterhegemony as pastoral theological intervention. Journal of Pastoral Theology, 30(3), 207–221.

Morris, J. (2021). Moral injury among returning veterans: from thank you for your service to a liberative solidarity. Lexington Books.

Ramsay, N. J., & Doehring, C. (Eds.). (2019). Military moral injury and spiritual care: a resource for religious leaders and professional caregivers. Chalice Press.

Rogers-Vaughn, B. (2014). Blessed are those who mourn: Depression as political resistance. Pastoral Psychology, 63, 503–522.

Rogers-Vaughn, B. (2015). Powers and principalities: initial reflections toward a post-capitalist pastoral theology. Journal of Pastoral Theology, 25(2), 71–92.

Sobrino, J. (1994). Principles of mercy: taking the crucified people from the cross. Orbis.

Scott, W. (1990). PTSD in DSM-III: a case in the politics of diagnosis and disease. Social Problems, 37, 294–310.

Shatan, C. (1972). May 6). Post-Vietnam syndrome. New York Times.

Shatan, C. (1973). The grief of soldiers: Vietnam combat veterans’ self-help movement. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 43, 640–653.

Shay, J. (1994). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Scribner.

Shay, J. (2014). Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(2), 182–191.

Smith, A. Jr. (1982). The relational self: Ethics and therapy from a Black church perspective. Abingdon.

Stone, O. (Director) (Ed.). (1986). Platoon [Film]. Hemdale Film Corp. Cinema 84.

Tietje, A. (2018). The responsibility and limits of military chaplains as public theologians. In S. D. MisirHiralall, C. L. Fici, & G. S. Vigna (Eds.), Religious studies scholars as public intellectuals (pp. 91–108). Routledge.

Tietje, A. (2021). War, masculinity, and the ambiguity of care. Pastoral Psychology, 70, 1–15.

Watkins Ali, C. (1999). Survival and liberation: Pastoral theology in african american context. Chalice Press.

Weidersheim, K. A. (2021). Dietrich Bonhoeffer: ideology, praxis and his influence on the theology of liberation. Political Theology, 23(8), 721–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/1462317X.2021.1925438.

Wiinikka-Lydon, J. (2017). Moral injury as inherent political critique: the prophetic possibilities of a new term. Political Theology, 18, 219–232.

Wimberly, E. (1979). Pastoral care in the Black church. Abingdon.

Winkie, D. (2022, January 25). Guard troops can unionize on state active duty, DoJ says. Army Times.https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2022/01/25/guard-troops-can-unionize-on-state-active-duty-doj-says/. Accessed April 4, 2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tietje, A., Morris, J. Shifting the Pastoral Theology Conversation on Moral Injury: The Personal Is Political for Soldiers and Veterans, Too. Pastoral Psychol 72, 863–880 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-023-01059-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-023-01059-x