Abstract

This paper examines whether the clarity of central bank communication about inflation varies with the economic environment. Using readability statistics and content analysis, we study the clarity of communication on the inflation outlook by seven central banks across three continents during the recent decade. We uncover significant and persistent differences in clarity over time and across countries. However, identifying determinants of clarity that are robustly relevant across our sample of central banks proves elusive. Overall, our findings suggest that a single model for clarity of central bank communication is not appropriate. Rather, when studying clarity of communication, country-specific and institution-specific factors are highly relevant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper aims for a deeper understanding of the clarity of central bank communication, in particular that related to the inflation outlook. Over the recent years, communication has become an integral element of monetary policy in many developed and emerging economies (Blinder et al. 2008). Indeed, central banks have made great efforts to increase their transparency and accountability to the public (Eijffinger and Geraats 2006; Dincer and Eichengreen 2007). Central banks provide a greater volume of information and communicate through a wider range of channels—including inflation reports, press releases, and press conferences—and this information tends to be available faster, more frequently, and to wider audiences than ever before.

By now, there is substantial evidence that central bank communication has been effective in providing the public with relevant information on monetary policy. Rosa and Verga (2007), for example, showed that market expectations react to information released by the European Central Bank (ECB) in its monthly press conferences. Hayo and Neuenkirch (2010) argued that Federal Reserve communication contributes to understanding federal funds target rate decisions. Ehrmann and Fratzscher (2007) analyzed the effects of comments by the Federal Reserve, the ECB, and the Bank of England (BOE). In particular, they discussed the connection between communication strategies and the underlying decision-making process of the committees who decide on interest rate policy.Footnote 1

Now that central bank communication has proven to be effective, other questions come into focus. In particular, what constitutes sound communication policies and how to measure their clarity? On the one hand, Alan Blinder (2009) has noted that ‘[s]ince clearer communications presumably have higher signal-to-noise ratios, they should in principle convey more information’. On the other hand, a few recent studies suggest that central banks have not always provided a clear message. Bulíř et al. (2008) and Bulíř et al. (forthcoming) find that central banks in a sample of developed and emerging market countries were clear on average between 60 % and 95 % of the time. Based on these findings, a further analysis of clarity of communication seems warranted.

What is clarity anyway? Is it simply lucidity of the text and its charts or is it consistency of the various signals, such as inflation forecasts and verbal assessments? The need to understand clarity is further underscored by some studies that argue that clarity matters. In a seminal contribution, Fracasso et al. (2003) have found that well-written inflation reports are associated with higher predictability of decisions. Recently, Jansen (2011b) has suggested that greater clarity of the Humphrey-Hawkins testimonies by the Fed chairman has gone hand in hand with lower volatility in financial markets. These findings do not imply that communication replaces sound economic analysis, but rather that clear communication can amplify the impact of such analysis.Footnote 2

We seek to answer two questions regarding clarity of central bank communications. First, to what extent has the clarity of central bank communication fluctuated over the years? To address this issue, we apply an often-used readability statistic to communications by seven central banks across three different continents during the recent decade. By doing so, we uncover significant and persistent differences in clarity over time and across countries. Readability appears to be country specific, reflecting partly the native tongue of the documents’ author.Footnote 3 Also, it is subject to longer-term trends. While some countries’ inflation reports have become more readable over time (Chile, Sweden, and the United Kingdom), in other countries readability worsened (Thailand). While such trends are presumably related to longer-term factors, such as internal efforts to produce clear communications, short-term deviations from such trends may be related to the economic environment.

Second, we try to explain variations in clarity over time. In particular, does the clarity of central bank communication depend on the context? Is clarity sensitive to the inflation outlook or uncertainty therein? To better understand why clarity could depend on the context, consider writing inflation reports under two different scenarios. In the first scenario, persistent monetization of debt has resulted in high inflation, and this policy is widely expected to continue. In the second scenario, there are many factors of inflation, some difficult to measure precisely, and some offsetting each other. There is relatively less for the central bank to gain (in terms of achieving its policy objective) by carefully “crafting the message” in the first scenario, because the causes of inflation are obvious and likely to continue; at the same time, delivering a clear message is relatively easy. In the second scenario, the potential gains for the central bank from a well-crafted message are substantial, although delivering a clear message is more challenging. In other words, communication becomes more challenging during complex economic situations, but incentives to communicate clearly also increase, so the empirical question that we examine is: which one of these two opposing effects is stronger? Specifically, during complex economic situations, do we observe an increased clarity of central bank communication?

To measure the complexity of the economic context, we use five proxy variables. Two of these covariates are based on the central bank’s own verbal assessment of inflation. To measure this assessment, we revert to content analysis (Holsti 1969; Krippendorf 2004). Two other covariates are related to the central banks objective for inflation. We use the gap between projected inflation and the objective as well as the difference between the most recently observed rate of inflation and the target. A fifth explanatory variable—available for four of the seven sample central banks—is the fraction of voting dissent in the monetary policy committee decisions. Our initial hypothesis is that when the inflation outlook is less certain, or less favorable, communication will be more difficult for the central bank, leading to less clarity. More uncertainty is typically associated with more explanatory factors and more challenges when measuring these factors and communicating their impact on the inflation outlook. Admittedly, in situations of greater uncertainty, the clarity of the central bank’s message yields a higher return. The central bank may be well aware that, in some cases, clear explanations are expected. If it then invests more heavily in the drafting process, clarity may well remain unchanged, or it may even increase. We are not aware of research that has sought to investigate this issue empirically.Footnote 4

Turning to results, identifying determinants of clarity that are robustly relevant across our sample of central banks proves elusive—only a handful of slope coefficients are significantly different from zero. In some cases, the central bank’s assessment of inflation and dissent in voting on interest rates explain a portion of the variation in clarity. Also, in three of the seven cases, the global financial crisis contributed to making central bank communication less clear. Overall, our findings suggest that a single model for clarity of communication is not appropriate. This conclusion mirrors earlier discussions in the literature, which stressed how communication strategies are often linked to country-specific and institution-specific factors (Blinder et al. 2008; Ehrmann and Fratzscher 2007).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the data and estimation approach. Section 3 presents results for the clarity of inflation reports, press releases and statements, and report length. Section 4 concludes with implications for future research.

2 Data and Methodology

2.1 Data and Content Analysis

Our analysis examines two main types of central bank communications during the last decade: (i) long documents aimed primarily at specialists (inflation reports, monetary policy report, and bulletins) and (ii) short documents aimed primarily at the general public (press releases and executive summaries of the long documents). To ensure consistency of our analysis, we include central bank documents only during the current monetary regime. Needless to say, before the onset of inflation targeting, most central banks did not communicate much on their monetary policy intentions, and there are no comparable pre-inflation targeting communications. Our sample period is also relatively free of unconventional policies (only the BOE engaged in “quantitative easing” toward the end of the sample period in March 2009, and BOE’s readability indicators of its communication during the “quantitative easing” period are not significantly different from the rest of the period).

Our sample consists of the following seven central banks: Banco Central de Chile, the BOE, the Bank of Thailand, the Czech National Bank (CNB), the ECB, the National Bank of Poland (NBP), and Sveriges Riksbank. These seven central banks combine advanced economies and emerging markets across three continents. Our main selection criterion was that the central banks focus strongly on inflation forecasts in their communications. Therefore, central banks in our sample have either adopted an inflation targeting regime or operate a framework in which the inflation outlook plays a similarly central role. Thus, our sample does not include central banks that pursue other objectives in addition to price stability, such as exchange rate stability, maximum employment, or moderate long-term interest rates. In those cases, communication would need to address a broader range of issues, as well as the trade-offs between multiple objectives. Such limitations make us exclude from our sample central banks that either fix their domestic currencies vis-à-vis the dollar and the euro or run “eclectic monetary regimes,” such as the U.S. Federal Reserve. Additional criteria in the sample selection were balanced coverage in terms of the world’s regions (the sample includes central banks from three continents), level of development (our sample includes both developed economies and emerging markets), size (our sample includes both small and large economies), and data availability. Table 1 provides an overview of the central banks as well as that or their communication tools.

To quantify the elements of various central bank communications, such as reports, press releases and statements, we use traditional content analysis techniques (Holsti 1969; Krippendorf 2004). Here, our approach is that of Guthrie and Wright (2000) and Bulíř et al. (forthcoming). In particular, we extract those text fragments containing the central bank’s view on various risks to inflation that are related to demand, supply, or external factors. The focus on inflation factors would be too narrow if the central bank had also other goals, conflicting with its inflation objective. However, since our sample consists of central banks that operate either inflation targeting or a similar (inflation-centered) framework, focusing on inflation-related communication seems to be a reasonable simplification.

We use a ternary coding scheme to categorize the comments, based on whether the inflation factors are expected to have inflationary (+1), neutral (0), or deflationary (−1) effects.Footnote 5 We then compute the central bank’s overall assessment of inflationary risks, by summing the individual coded inflation factors. We give each factor an equal weight because the communication usually does not provide explicit guidance on the factors’ quantitative importance. We also want to avoid further subjective judgments regarding the aggregation of the individual risk factors. To give an example, if an inflation report highlights three inflationary factors, and two deflationary factors, our overall measure—which we will denote by S—equals one. Larger positive (negative) values for S mean that the central bank is signaling greater concerns regarding inflationary (deflationary) risks. In the empirical analysis, we use the absolute value of S, rather than the value of S itself. The motivation is that larger positive as well as negative values equally warrant more elaborate explanations from the central bank. In addition, we will also use the dispersion of the individual inflationary factors. For most central banks, the communications data is available on a quarterly frequency. For the ECB, we use the quarterly averages for the individual Monthly Bulletins.

While this paper focuses on written communication by central banks, our analysis also covers central bankers’ statements intended for verbal delivery. The focus on written communication seems warranted by the general finding that these types of communication usually have a larger impact on financial markets than speeches or testimonies (Blinder et al. 2008). Still, we also include some spoken communication, in particular the Introductory Statements by the ECB President and the Opening Remarks by the Governor of the Bank of England. The introductory statements and opening remarks, of course, draw upon and are related to the underlying reports (monthly bulletin and inflation report, respectively). Nonetheless, including documents intended for verbal delivery provides an opportunity to compare their clarity relative to the clarity of the underlying reports.

2.2 Measuring the Clarity of Communication

One way to think about clarity of communication is by asking how easy it would be for someone to understand the information contained in the English version document. This notion of clarity underlies the so-called Flesch-Kincaid (FK) grade level (Kincaid et al. 1975) that can be interpreted as the number of years of education needed to sufficiently comprehend a text. The FK statistic was developed in the mid-1970s for the U.S. Navy and has since been widely applied in a variety of fields in English speaking countries (Clatworthy and Jones 2001; Paasche-Orlow et al. 2003). The FK scale is objective to the extent that it only uses textual characteristics of texts, such as the number of words, sentences, and syllables.Footnote 6 It is calculated as:

The intuition is that many words per sentence or many syllables per word decrease readability. If someone has to process a text with long words or sentences, it will be harder to grasp the message, and therefore would require more years of education. In our sample, the Flesch-Kincaid grade level varies from 10 to 19 years, with differences over time, across countries, and between the various communication channels in the same country.Footnote 7 Our argument is that the FK readability statistic is an intuitive way to measure variation in clarity. One potentially fruitful direction in which to extend the analysis is studying the amount of economic jargon and its complexity.

Our focus on the English version of central bank documents reflects the importance of English in modern central bank communication. The transmission of information works as follows. First, the central bank issues a document simultaneously in English and the native language(s).Footnote 8 The timing of these releases is known in advance and the internet is a key medium. Second, the document is read instantaneously by market analysts and international news agencies (Reuters, Bloomberg, and so on), who process and intermediate it further in a matter of hours. This step is done almost exclusively in English as analysts tend to cover several countries and are not necessarily speakers of the local language.Footnote 9 Third, domestic news agencies and newspapers in other countries pick up the analysis prepared in the previous step and disseminate its key message to their domestic audiences, often in languages other than English. To this end, readability of English-version documents is of paramount importance.

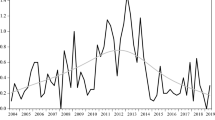

We find substantial variation in the Flesch-Kincaid grade level over time for each of the seven central banks in our sample (Fig. 1). One element of the variation are underlying trends in some countries: the readability of the central bank documents improved in Chile (requiring about two years less of schooling to comprehend the text in 2010 as compared to 2000), worsened in Thailand (requiring some additional four years of schooling), worsened marginally in Poland, and remained broadly unchanged in the rest of the sample. To check for nonstationarity of the readability scores we use the Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin test—which is to be preferred for smaller samples (Kwiatkowski et al. 1992)—and find that they were either stationary or trend stationary.Footnote 10 We therefore include a trend term (1998q1 = 1) in the subsequent regressions to account for the country-specific trends.

Readability of inflation reports and press statements, 1997–2010. (Flesch-Kincaid grade level; solid lines for reports and dashed lines for statements). Authors’ calculations based on information from the national central banks’ websites. The Flesch-Kincaid grade level can be interpreted as the number of years of education needed to comprehend a text. Missing observations were interpolated. The Czech National Bank does not issue press statements. See also Table 1 for further details

We also find statistically significant differences among countries (Fig. 2). Although we believe that reports are mostly read in English, many central banks draft them initially in native languages and some of the native-language clarity may get “lost in translation.”Footnote 11 The average Flesch-Kincaid score for an inflation report in any given country is therefore likely to depend on the features of the primary language of the country and on the way the primary language is translated into English. The most easily readable documents are those of United Kingdom and Sweden, requiring on average about 12 years of schooling; followed by the Czech Republic, requiring about 14 years; and, finally, those in the remaining four central banks require about 16 years for inflation reports and a little less for press statements. It would be a stretch, however, to interpret mechanically these cross-country differences of clarity of communication.Footnote 12 For our purposes, of course, the level of clarity is not directly relevant. Rather, our aim is to relate the fluctuations in clarity to the changing context in which the sample central banks operate. Trends and idiosyncratic shocks to communication aside, the variation in the Flesh-Kincaid grade level should be a good proxy for changes in clarity of communication, relative to other communications from the same central bank.Footnote 13

Summary statistics for readability of inflation reports and press statements (Flesch-Kincaid grade level, sample period). Authors’ calculations. The boxplot denotes the sample mean with a circle; the median and is its 95 % confidence interval with a line and the shaded area, respectively; the left and right sides of the box indicate the lower and upper quartiles; the whiskers are defined as the first quartile minus 1.5*interquartile range (IQR) and the third quartile plus 1.5*IQR. The Czech National Bank does not issue press statements

To provide a richer picture, we also consider document length as an alternative dimension of communication. The relationship between length of central bank documents and clarity is not straightforward. On the one hand, crafting a more precise, more nuanced message in an uncertain environment typically requires a longer communication. On the other hand, such a communication risks burying the message in a long or complex document, and ultimately becoming less clear. Therefore, we treat length as an additional feature of communication, separate from its clarity.

2.3 Analyzing Variations in Clarity

We now turn to a more formal analysis of clarity. We examine whether variations in clarity are related to quantifiable factors that capture changes in the context in which the communications took place. In our analysis, we include five elements warranting some type of explanation to the public, either because the outlook for inflation is less favorable, or because it is less certain. These factors are: (i) an absolute count of inflation factors (based on the content analysis); (ii) a measure of dispersion among the various inflation factors (based on the content analysis); (iii) forward-looking (ex ante) deviation from the inflation target; (iv) contemporaneous deviation from the inflation target; and (v) voting dissent in monetary policy committees.

We include these five factors in the following reduced-form regression:

where FK it denotes the Flesch-Kincaid grade level of a communication instrument (report, press release, or statement) issued by a central bank i in quarter t. Higher values of FK it imply less clarity: a reader would need more schooling to sufficiently comprehend the document. As an alternative measure for clarity, we also use the length of the documents. We use three deterministic variables: β 0 is a constant, α i captures country-specific effects, and T it is a linear trend.

The first two covariates (|S it | and V it ) refer to the central bank’s assessment of inflation in their communications. The variable S it , as discussed in Section 2.1, is the sum of the values of signals with respect to aggregate demand (AD it ); aggregate supply (AS it ); and external factors (FOR it ). Respective examples of such signals are fiscal and cyclical demand pressures (AD); labor supply pressures and capacity utilization (AS); and exchange rate shocks (FOR). Also as noted, the empirical analysis uses the absolute values of S it , i.e., a count of inflation factors. The motivation is that both upward and downward risks to price stability may equally warrant more explanation from the central bank. In our dataset, the average value of |S it | equals 2.5, while the maximum observed is 12.

The second measure, V, captures the dispersion in S it across the demand–supply-external factors. We measure dispersion as the distance between the individual signals from demand, supply and external factors, so that \( {V_{{it}}} = \left| {AD - AS} \right| + \left| {AD - FOR} \right| + \left| {AS - FOR} \right| \). Suppose the signals from demand, supply and external factors are all equal to each other. In that case, the central bank does not need to address potentially conflicting signals, and our measure V would be equal to zero. In our dataset, the mean value of V equals 5, while the maximum observed is 14.

The next two covariates compare inflation to the (time-varying) inflation targets in the sample central banks.Footnote 14 The third covariate is the absolute difference between the official inflation forecast/projection four quarters ahead, \( {E_{{it}}}\left( {{\pi_{{i,t + 4}}}} \right) \), and the inflation target, \( \pi_{{it}}^{ * } \), that is, the forward-looking (ex ante) inflation gap.Footnote 15 The fourth covariate is the absolute difference between current-period inflation and the target, where inflation is measured as year-on-year inflation in the quarter during which the report was published, i.e., the contemporaneous inflation gap. Central banks frequently discuss both why the inflation target was missed in the recent past and why it may be missed in the future.

The fifth covariate, included for those four central banks in our sample that publish voting records of their monetary policy committees, is the fraction of dissenting votes, DIS it . We use averages for all votes in meetings taking place during the quarter in which the report was published. Across the countries, there are some differences in the extent to which dissent finds its way into the report itself. In some central banks (e.g., the CNB), the staff writes the report with limited input from the monetary policy committee, so dissent is primarily expressed in the share of dissenting votes. In others (e.g., the BOE), the monetary policy committee is involved in designing the scenarios, so dissent may be reflected in the report to a larger extent. In both arrangements, however, the share of dissenting votes in the committee is a reasonable proxy for dissent, considering also that we focus on developments over time rather than cross-country comparisons.

What are reasonable priors for the β coefficients? For all five covariates, higher values imply the central bank has more to explain to the public—either the outlook for inflation is less positive, or there is less certainty regarding inflationary developments. For example, higher absolute levels of S it indicate the central bank is less comfortable about its outlook for inflation as it identifies a greater number of risks to price stability. Similarly, if there is a greater dispersion in the underlying signals, reflected in a higher value of V it , the central bank may want to explain what drives this dispersion and how it weighs the various and potentially conflicting signals. Particularly puzzling are deviations of inflation projections from the target and the central bank must to explain why it expects future inflation to remain above/below the target, and what are policy implications thereof. A similar story holds for the current level of inflation and its deviation from the target. Although inflation targeting implies a forward-looking policy, the public does pay attention to the contemporaneous inflation gap as it is indirectly linked to pension adjustments, wage negotiations, and so on. Finally, if the views of the monetary policy committee members start to diverge, the public may be less sure of which way the central bank’s policy will go.

Under our null hypothesis, the clarity of communication is impaired when the central bank is less sure about future developments or when it needs to explain larger deviations from the inflation target. Suppose that current inflation is above the target, but the official inflation projection/forecast is close to the target, even though the reports mention numerous and mutually offsetting inflation factors. It is going to take effort to present these developments in an accessible manner, presumably leading to a higher Flesch-Kincaid score. In other words, under the null hypothesis, one or more of the β coefficients would be positive. However, the central bank very well may be aware that, in some cases, it needs to present a clear message to the public. To enable this, the central bank may decide to devote more resources to the drafting process. If it succeeds, the clarity of its communications may remain unchanged, or it may even increase.

The correlations matrix in Table 2 suggests that the FK grade level is correlated with the number of words, and—as one could expect—there is a strong correlation between the number of words and the number of sentences. Also, the share of dissenting votes in the monetary policy committee is positively correlated with the number of words and sentences in the communication as well as with the FK grade level. The remaining pairwise correlations among the variables of interest are relatively low.

3 Results

We discuss the country-specific results of our clarity analyses in the following order: inflation reports, releases/statements, and document length, see Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively. We have also estimated a pooled regression, combining the data for the seven countries. However, results based on random-coefficient models (available upon request) suggest that none of the variables considered in Eq. (2) has a statistically significant effect that would be robust across the countries.

3.1 Clarity of Inflation Reports

The regression results are consistent with the graphical evidence discussed in Section 2. Readability of inflation reports, as measured by the Flesch-Kincaid grade level, is mostly country-specific and driven by deterministic variables. The constant terms point to significant differences in clarity (Table 3). Moreover, we also find, in some cases, significant coefficients for the trend. The inflation reports have become clearer over time in Chile, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, improving by almost 1/5 of a year of schooling per year. In contrast, the euro area Monthly Bulletins and in particular Thai inflation reports have become less clear during the sample period, by about 1/10 and 2/5 of a year of schooling per year. For the Czech Republic and Poland, there are no statistically significant trends.

Of the non-deterministic explanatory variables, only a handful appear to affect readability and none of them consistently across the sample. So, overall, it is difficult to relate changes in clarity to the economic context in which communications occurred. First, the number of inflation factors identified by the central bank (|S|) is associated with a reduction in FK in four out of seven sample countries, but this finding is statistically significant only for the Czech Republic. So, mentioning more risk factors coincides with an increase in report clarity, but this variable is not significant in most countries. Second, uncertainty regarding the inflation signal (V) does not have a significant impact on report clarity. Third, the absolute deviation of the inflation forecast from the target, \( \left| {{E_{{it}}}\left( {{\pi_{{i,t + 4}}}} \right) - \pi_{{it}}^{ * }} \right| \), reduces an inflation report’s clarity, that is, increases its FK score in two out of seven countries. However, the results are statistically significant only in the United Kingdom. In this case, the expected over/undershooting of the inflation target corresponds to a decline in readability of about ¾ of a year of schooling. Fourth, for most countries, past inflation deviations from the target are associated with lower clarity of an inflation report; however, the results are statistically significant only for the Czech Republic. Finally, a higher fraction of dissenting votes regarding monetary policy decisions is associated with a significantly increased clarity in the United Kingdom (for Sweden, the point estimate has the same sign, but is not statistically significant). The greater level of clarity could help to explain why Gerlach-Kristen (2004) finds that the presence of dissent contains useful information for predicting subsequent rate changes. We note that the results for the BOE and CNB are similar: in both cases, we find a negative impact of inflation gaps and a positive impact of signal uncertainty. The exact channels differ, however: in the case of the BOE, the inflation gaps are contemporaneous and the signal uncertainty is approximated by the signal count, while in the case of the CNB, the inflation gaps are expected, and the signal uncertainty is approximated by the voting dissent.

3.2 Clarity of Press Releases and Statements

Readability of press releases (Chile, Poland, Sweden, and Thailand) and statements (the euro area and the United Kingdom) follows similar patterns as that of inflation reports (Table 4). The estimates of the constant term and trend are statistically significant and we find that communication has become clearer over time in Chile and Sweden (by about ¼ of a year of schooling per year). In contrast, communication became less clear over time in the euro area, Poland, Thailand, and the United Kingdom. The differences in the latter group are large—for example, the decline in readability was three times larger in Thailand as compared to the United Kingdom.

None of the non-deterministic explanatory variables play a systematic role and only two variables are statistically significant in some countries. First, the uncertainty regarding the inflation signal (V) reduces communication clarity in Poland, Sweden, Thailand and the United Kingdom, but only the coefficient for the United Kingdom is significant. Second, past inflation deviations from the target are associated with increases in communication clarity in Sweden and the United Kingdom.

3.3 Length of Inflation Reports

The results for document length, measured as the number of words in the executive summary of the inflation report, are also very much country specific (Table 5). The length of the executive summary in individual countries did not vary much. However, in most countries, report length trended upward (the euro area, Poland, Thailand, and the United Kingdom). We find that the count of inflation factors, |S|, reduced report length in the Czech Republic. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, reports with more dispersed inflation factors are significantly shorter (in the euro area, Thailand, and the United Kingdom). A possible explanation could be that these central banks are compensating for the dispersion in inflation factors by trying to communicate more concisely. Contemporaneous inflation gaps are associated with longer reports in the euro area and the United Kingdom, but with shorter ones in Thailand. Finally, dissent in the board room increases report length in Poland. We have also estimated a pooled regression, and the results (available upon request) again suggest that none of the variables considered has a robust effect across all countries.

3.4 Impact of the Global Financial Crisis

The global financial crisis has presented unique challenges for monetary policy, including on the communication front, as policymakers have aimed to simultaneously reassure the public and communicate the potential vulnerabilities. To this end, some central banks tried to explicitly distinguish crisis-related measures and messages from those related to the regular conduct of monetary policy.

To examine the impact of the crisis, we introduce a binary dummy variable. While there is little disagreement that there was a global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, the exact timing of the crisis is debatable. The onset of the crisis is usually linked to the Lehman Brothers filing for bankruptcy protection in September 2008. The end of the crisis is less clear, as the financial markets remained in turmoil through 2009. With this in mind, the crisis dummy equals 1 from 2008q4 to 2009q4 and 0 otherwise.

Table 6 reports results for three country-level regressions (Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) where the crisis dummy is statistically significant and positive. For the other countries, it is not significantly different from zero. The coefficient for the crisis dummy suggests that, on average, the financial crisis added about 1–2 additional years of schooling needed to understand the reports. The crisis dummy leaves the earlier estimates from the Table 3 broadly unaffected. In this case, we also ran pooled-regressions. The coefficient for the crisis dummy implies additional ½ year of schooling, but it is not statistically significant.

3.5 Sensitivity Analysis

In addition to the global financial crisis, we also explored the sensitivity of our results along several other dimensions. First, we included the number of individual inflation factors, (AD it ), (AS it ), and (FOR it ), as additional regressors and found all variables to be statistically insignificant. We also added lagged values for past inflation deviations,\( \left| {{\pi_{{it}}} - \pi_{{it}}^{ * }} \right| \), and voting dissent (in the baseline model only the contemporaneous values were used). The motivation was that if the communications were released early in the quarter, probably not all information on inflation or dissent was available to those drafting the inflation reports. Again, the results with the lagged values did not differ materially from the main results.

Thirdly, we investigated whether the political environment could be related to clarity. To this end, we gathered data on the timing of elections, government changes, and coup d’etats. We also used the data on central bank governor turnover collected by Dreher et al. (2010). As the number of events per country is generally lower than five, we first used pooled regressions. However, we found no evidence of a significant relationship between political events and clarity. For the country with the highest number of political events (Thailand), we did find evidence suggesting that clarity was lower after periods with political changes. However, further analysis would be needed to reach definitive conclusions on the relationship between political context and the clarity of central bank communication.

Finally, we also experimented with an automated general-to-specific procedure using the Autometrics routine in Oxmetrics. The findings were qualitatively not affected and the routine selected non-deterministic variables identical to those identified in section 3.1—after identifying country-specific time dummies for the crisis period—while the deterministic variables (constant and trend) remained the most relevant for modeling clarity of communication.

4 Conclusions

This paper has combined a standard measure for readability (the Flesch-Kincaid grade level) with content analysis to analyze the clarity of various communication channels (inflation reports, press releases, and statements) on the inflation outlook by seven central banks during the recent decade. We focus on the English version of central bank documents, since the analysis and dissemination of these communications by market analysts and international news agencies is done mostly in English.

Our results suggest that readability is largely country-specific, with significant and persistent differences in clarity over time and across countries. We find little evidence that clarity of central bank communication changes significantly with higher uncertainty or with less favorable inflation outlook. Explaining short-term fluctuations in clarity has proved to be elusive, although the central bank assessment of inflation and dissent in voting on interest rates does explain some of the variation in clarity. Also, the impact of the global financial crisis is associated with relatively lower clarity in central bank communication in some cases.

Overall, our findings suggest that a single model for clarity of central bank communication is not appropriate. Rather, country-specific and institution-specific factors should be taken into account. This finding has important implications for those studying the effects of clarity, for instance along the lines in Jansen (2011b). Depending on the central bank under study, appropriate control covariates need to be selected, based on a thorough understanding the context in which communication has taken place. One avenue of research to follow up on the current paper is to extend the analysis beyond the current sample of the seven banks, and examine factors that influence the ways in which central banks adjust their monetary policy communications in response to external developments. It could also be of interest to expand our analysis to other forms of central bank communication, such as oral statements by central bank officials and the contents of monetary policy committee minutes (in countries where these are published), as well as communication on topics other than the inflation outlook and, in particular, on financial stability.Footnote 16

Notes

See Blinder et al. (2008) for a discussion of the literature up to 2008. Recent contributions on communication to financial markets include Brand et al. (2010), Hayo et al. (2010), Neuenkirch (2012), and Rosa (2011). Van der Cruijsen et al. (2010) study communication to the general public using a survey of Dutch households.

The term “country”, as used in this paper, may include also territorial entities that are not countries, but for which separate economic statistics are produced.

There is an analogy with a debate in the accounting literature that focuses on analyzing readability of corporations’ annual reports. For instance, Courtis (1998) finds some evidence that, rather than present accounting narratives objectively, managers use readability variability to emphasize good news and obfuscate bad news. However, other studies suggest that there is no such temporary variation (Clatworthy and Jones 2001).

First, each verbal comment was catalogued into a major category and several subcategories: demand (fiscal, domestic cycle pressure, wages, external demand, domestic asset price bubbles, other), supply (weather and similar shocks, oil/gas prices, agricultural prices, capacity utilization, labor supply, regulated prices, structural changes, retail competition, indirect taxes, other), or external (exchange rates, global financial shocks, other). Second, factors putting upward/downward pressure on inflation were denoted as +1/−1 and neutral factors were denoted as 0. Below are some examples of our coding using the ECB’s Monthly Bulletins. The January 2003 issue contained the following sentence: “the current subdued pace of economic growth should contain inflationary pressures” and was coded as −1 in the demand category. The January 2003 bulletin noted “various increases in administered prices,” and was coded as +1 in the supply category.

In addition to its objective nature, other reasons for choosing the Flesch–Kincaid measure include its convenience (the Flesch–Kincaid system is embedded in Microsoft Word), wide use in studies of readability, repeatability, and excellent comparability with other established readability scales, such as the fog index and the automated readability index. For instance, Kincaid and others (1975) have reported correlation coefficients of about 0.9 vis-à-vis alternative measures.

In the interest of full disclosure, the FK grade level of our paper is 14.3 years.

In the case of the ECB, communication is issued simultaneously in all member languages.

The staff of the Czech National Bank provided further anecdotal evidence: virtually all questions and comments with respect to the CNB inflation reports have been written either in English or referred to the English version of the documents.

Results for the KPSS-tests are available upon request.

The front-page footnote in the English-language Chilean reports explicitly states the seniority of the Spanish original: “This is a translation of a document originally written in Spanish. In case of discrepancy or difference in interpretation the Spanish original prevails.” Central bank reports in other countries contain similar disclaimers.

Jansen (2011a) also stresses that readability measures should be carefully interpreted.

Our use of the FK grade level to approximate changes in clarity of communication does not mean that central banks necessarily actively use this particular readability measure in polishing their external communications. That said, much of the research on clarity of central bank communication is (co)authored by central bank staff, so this is an area of some interest. Perhaps more importantly, central banks employ professional editors and communication experts, underscoring the importance they attach to properly calibrating their external communications.

Information on inflation targets and their changes was taken from the central bank documents or websites. Generally, inflation targets do not tend to change often, but our sample does contain some changes in inflation targets, which are reflected in the calculations. For example, in December 2003, the Bank of England’s target changed from 2.5 % retail price index (RPIX) inflation to 2 % inflation in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Also, Chile, the Czech Republic, and Poland had declining inflation targets during the first few years of the sample. Data on the targeted inflation series, usually headline inflation based on either harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) or regular index of consumer prices CPI indices, were taken from Haver Analytics.

The construction of inflation forecasts differs across central banks. For example, the CNB’s forecast is fully endogenous, while BOE and ECB forecasts are, nowadays, conditional on market expectations. Other things equal, the CNB’s ex ante one-year inflation gap will likely be smaller than the BOE’s one: the policy rule, coupled with model-consistent expectations, ensures that the inflation forecast is at the target in a horizon of about 2 years. In our context, however, this is not a major issue. We are not focusing on cross-country comparisons, but rather on comparisons within a country, and the construction of inflation forecasts for our sample countries has been reasonably consistent.

References

Blinder AS (2009) Talking about monetary policy: the virtues (and vices?) of central bank communication. BIS Working paper no. 274. (Basel: Bank for International Settlements). http://www.bis.org/publ/work274.htm

Blinder AS, Ehrmann M, Fratzscher M, De Haan J, Jansen D (2008) Central bank communication and monetary policy: a survey of theory and evidence. J Econ Lit 46:910–945

Born B, Ehrmann M, Fratzcher M (2011) Central bank communication on financial stability. ECB Working Paper 1332. (Frankfurt: European Central Bank). http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1332.pdf

Brand C, Buncic D, Turunen J (2010) The impact of ECB monetary policy decisions and communication on the yield curve. J Eur Econ Assoc 8:1266–1298

Bulíř A, Čihák M, Šmídková K (forthcoming) Writing clearly: the ECB’s monetary policy communication. Ger Econ Rev. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0475.2011.00562.x

Bulíř A, Šmídková K, Kotlán V, Navrátil D (2008) Inflation targeting and communication: it pays off to read inflation reports. IMF Working Paper 08/234. (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund). http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp08234.pdf

Čihák M, Muñoz S, Sharifuddin ST, Tintchev K (2012) Financial stability reports: what are they good for? IMF Working Paper 12/1. (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund). http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp1201.pdf

Clatworthy M, Jones M (2001) The effect of thematic structure on the variability of annual report readability. Account Audit Account J 14:311–326

Courtis JK (1998) Annual report readability variability: tests of the obfuscation hypothesis. Account Audit Account J 11:459–471

Dincer N, Eichengreen B (2007) Central bank transparency: causes, consequences and updates. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 14791

Dreher A, Sturm J-E, De Haan J (2010) When is a central bank governor replaced? Evidence based on a new data set. J Macro 32:766–781

Ehrmann M, Fratzscher M (2007) Communication by central bank committee members: different strategies, same effectiveness? J Money, Credit, Bank 39:509–541

Eijffinger SCW, Geraats PM (2006) How transparent are central banks? Eur J Pol Econ 22:1–21

Fracasso A, Genberg H, Wyplosz C (2003) How do central banks write? Geneva Reports on the World Economy, Special Report 2. (Geneva: The Center for Economic Policy Research). http://hei.unige.ch/~wyplosz/IR_fgw.pdf

Friedman BM (2008) Monetary policy and central bank communication: complements or substitutes? Comments on Blinder et al. (2008) http://www.bis.org/events/conf080626/friedman.pdf

Gerlach-Kristen P (2004) Is the MPC’s voting record informative about future UK monetary policy? Scand J Econ 106:299–313

Guthrie G, Wright J (2000) Open mouth operations. J Monetary Econ 46:489–516

Hayo B, Neuenkirch M (2010) Do Federal Reserve communications help predict federal funds target rate decisions? J Macroecon 32:1014–1024

Hayo B, Kutan A, Neuenkirch M (2010) The impact of U.S. central bank communication on European and Pacific equity market. Econ Lett 108:172–174

Holsti OR (1969) Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Jansen D (2011a) Mumbling with great incoherence: was is really so difficult to understand Alan Greenspan? Econ Lett 113:70–72

Jansen D (2011b) Has the clarity of central bank communication affected financial markets? Evidence from Humphrey-Hawkins testimonies. Cont Econ Pol 29:494–509

Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS (1975) Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Research Branch report 8–75. Naval Air Station, Memphis

Kohn DL (2008) Recent and prospective developments in monetary policy transparency and communications: a global perspective. Speech at the 2008 ASSA Meetings. http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/kohn20080105a.htm

Krippendorf K (2004) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Kwiatkowski D, Phillips PCB, Schmidt P, Shin Y (1992) Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? J Econom 54:159–178

Neuenkirch M (2012) Managing financial market expectations: the role of central bank transparency and central bank communication. Eur J Pol Econ 28:1–13

Paasche-Orlow M, Taylor H, Brancati F (2003) Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med 348:721–726

Rosa C (2011) Talking less and moving the market more: evidence from the ECB and the Fed. Scott J Pol Econ 58:51–81

Rosa C, Verga V (2007) On the consistency and effectiveness of central bank communication: evidence from the ECB. Eur J Pol Econ 23:145–175

Van der Cruijsen CAB, Jansen D, De Haan J (2010) How much does the public know about the ECB’s monetary policy? Evidence from a survey of Dutch households. European Central Bank, Working Paper No. 1265. http://www.dnb.nl/binaries/Working%20paper%20252_tcm46-236503.pdf

Woodford M (2005) Central bank communication and policy effectiveness. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 11898

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Ehrmann, Jakob de Haan, Helge Berger, Caroline Silverman, Nico Valckx, Zdeněk Tůma, Tomáš Holub, and participants in the 16th Annual International Conference at the University of Crete and in seminars at the International Monetary Fund, the Czech National Bank, and De Nederlandsche Bank for useful suggestions and discussions. The paper also greatly benefited from comments by two anonymous referees. Jansen thanks the IMF Institute for hospitality during his stay as visiting scholar. Research assistance by Kazim Kazimov and Caroline Silverman is gratefully acknowledged. Views expressed in the paper do not necessarily coincide with those of the IMF, the World Bank, the Eurosystem, de Nederlandsche Bank, or the Czech National Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bulíř, A., Čihák, M. & Jansen, DJ. What Drives Clarity of Central Bank Communication About Inflation?. Open Econ Rev 24, 125–145 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-012-9259-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-012-9259-z