Abstract

This study investigates the factors that drive US industry sectors’ response to domestic natural disasters for the period 1987–2018. In general, our results show that not all local industry portfolios experience more negative impacts than non-local industries. We find that location does matter, but the nature of the industry itself is also important. Moreover, results for firm size show that big firms outperform small firms, across many industry settings. Finally, disaster severity analysis reveals that industries react differently to disasters of different magnitudes, and the response also varies across the different disaster measures. Our findings provide a basis for development of equity reaction prediction in the event of natural disasters, thus mitigating the disaster risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, we have experienced a number of deadly natural disasters (e.g., Huricanes and wildfires in North America, floods, earthquake and tsunamis in Asia).Footnote 1 These disasters have cost US$820 billion to the global economy and affected 1 billion people.Footnote 2 Alongside the literature that discusses natural disaster-related general risks (see, e.g., Jongman et al. 2014; Brammer et al. 2019), finance studies investigate the economic impact of natural disasters on financial markets. These studies are generally limited to either a specific event or a specific industry sector (Wasileski et al. 2011; Pearson et al. 2011; Shan and Gong 2012; Fink and Fink 2013; Carleton and Hsiang 2016; Noth and Rehmbein 2019).

While a few studies examine the performance of different industries in the aftermath of natural disasters and find that industries react differently to such extreme events, and the reactions are not always negative (Worthington and Valadkhani 2004; Malik et al. 2020). Moreover, it still remains unclear why industries respond differently, i.e., some sectors react positively to natural disasters, while others show a negative response. We enhance and extend the existing literature and study the possible factors driving such variations across a comprehensive set of industries in the aftermath of natural disasters.Footnote 3

Intuitively, firms located in the disaster-hit areas are expected to be more negatively affected than those located outside. However, the existing literature does not provide conclusive evidence to support this intuition; in fact, some studies disagree that natural disasters are bad for the local economy (see, e.g., Botzen et al. 2019; Ulubaşoğlu et al. 2019; Boustan et al. 2017; Belasen and Polacheck 2008, Schumpeter 1942). Our study extends the literature and uses firm location information in conjunction with the industry sector to explore industry-wise firm response to natural disasters. Specifically, we explore the following research question: “Do constituent firms’ location, in conjunction with the industry it belongs to, explain the magnitude and direction of equity responses to natural disasters?”Footnote 4 Answering this question will help investors devise sound investment strategies to counter the natural disaster impacts well in advance of the event occurrence. Similarly, with an industry effect in mind, firm management can evaluate benefits (or otherwise) of locating firms in a disaster-prone area relative to disaster-free areas. Furthermore, findings of this study can help policy makers devise time-critical tailored post-disaster recovery packages, e.g., to which firms/industries the government’s financial support should be extended and to what extent. Funding agencies can also use findings of this study to forecast the credit needs (of the firm located in the disaster areas) in advance by carefully looking at the industry-wide distribution of the firms in the area.

Prior studies also discuss the importance of size in determining firms’ resilience to natural disaster; however, size is limited either to a firm or a specific industry. Basker and Miranda (2014) find negative impacts of hurricane Katrina on young and small firms, respectively. Fink and Fink (2013) find increasing returns of oil refineries during the Gulf of Mexico hurricanes and attribute this increasing trend to large firms utilizing their idle capacity and geographic diversification. They also suggest no significant impact of such hurricanes on small firms. As evident from these mixed findings, the current literature is not only limited but also disagrees on the importance of firm size in explaining the price reaction of industry portfolios to natural disasters. With this in mind, we sort the industry portfolios into small versus large firms and analyze their reaction when such disasters strike. Moreover, we also investigate the importance of disaster intensity—namely, whether and to what extent the magnitude of the natural disaster drives the equity responses. Larger disasters, intuitively, are more damaging and exert negative impact on the markets relative to less severe disasters. However, some studies argue that natural disasters create a demand for certain industries’ products which leads to increased prices and in turn high returns (see, e.g., Fox et al. 2009; Gu and Nyak 2016; Donaldson and Goodchild 2017). Due to the limited literature and inconclusive findings, we examine the market reaction of a range of industries to natural disasters based on human and financial loss.

To conduct our analysis, we analyze all natural disasters hitting the U.S. over the period January 1987–December 2018 and focus only on the disasters with specific start and end dates. We use the event study methodology to examine the immediate and post-disaster market reactions across different scenarios. In terms of portfolio construction, we use headquarter location of the constituent firms to sort local and non-local industries (see, e.g., Korniotis and Kumar 2013; Dessaint and Matray 2017). Dessaint and Matray (2017) argue that data for production units are not readily available, so they rely on the assumption that on average, such units are located in the same place as the headquarters (see, e.g., Chaney et al. 2012). For size-based portfolios, we use the median market capitalization, in order to assess their differential vulnerability to natural disasters. Finally, for disaster severity, we segregate the disaster impacts into different quartiles based on the extent of human and financial damage to the economy. We also conduct a range of other sensitivity checks to secure the reliability of our findings.

We document several notable findings. First, location in conjunction with the industry type plays an important role in explaining the equity market reaction. Our results suggest that not all local industries are negatively affected, and it depends on the industry type in which the firm is operating. Second, industries comprising of large firms outperform the industries comprising of small firms in the event of natural disasters and, hence, provide relatively safer investment opportunities. Third, industries not only react differently to disasters of different magnitudes, but the reaction also varies across the different disaster measures. Some industries (like Drugs) benefit when financial (human) loss is low (high), whereas others (like Gold) earn abnormal returns when the financial (human) loss is high (low). We conclude that the industry in which the firm operates has a big part to play in the magnitude and direction (positive, negative, or zero) of their equity reaction.

Overall, our study extends the existing literature in two key dimensions. First, it investigates whether and to what extent firm characteristics (size and location) explain the extent and direction of industry responses to natural disasters. In doing so, this study, for the first time, facilitates development of equity reaction prediction, in the event of similar natural disasters, to mitigate potential disaster risk.

Second, this study examines the importance of disaster characteristics in explaining the impacts of natural disasters on different sectors and helps unpack the natural disaster–equity relationship. The findings from this study help fill the void on whether and the extent to which the magnitude of respective natural disasters explains the variations in the performance of the respective industries. Findings will assist practitioners in devising sound investment strategies in the event of natural disasters and help governments devise industry-targeted post-disaster recovery plans in terms of extending (or not) the financial support to the firms located in the disaster-hit region.

This study proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review and hypotheses development, and Sect. 3 describes the data and research methodology. Section 4 presents the results, followed by a discussion. Section 5 provides additional analysis, and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

Prior studies document variation in disaster impacts across different industries (e.g., Fink and Fink 2013; Wang and Kutan 2013). However, researchers are yet to identify the factors driving these variations to assist different stakeholders in developing predictable reaction patterns to mitigate the potential disaster risk.

Few studies examine the localized impact of natural disasters on a specific industry and report contradictory findings. Wang and Kutan (2013) provide evidence of a positive impact of natural catastrophes on the performance of Japanese insurance stocks. Similarly, Fink and Fink (2013) show that hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico exert a positive impact on the price return of the oil refineries located in the affected region. However, Hosono et al. (2016) examine the banking sector and show that the Kobe earthquake negatively affected the lending capacity of banks located in the disaster-affected region, thus aggravating the borrowing constraints of their clients. They provide two measures of bank damage such that “the damage to a bank’s headquarters is likely to capture the decline in a bank’s managerial capacity to process loan applications at the back office, the damage to a bank’s branch network captures the decline in the bank’s financial health and risk-taking capacity”(p.1336). In contrast, Schüwer et al. (2019) examine the impact of hurricane Katrina on banks and suggest a positive impact on the independent banks located in the disaster-affected regions. Similarly, Bourdeau-Brien and Kryzanowski (2017) study the impacts of natural disasters for U.S. firms located in disaster-hit states and suggest negative equity behavior, whereas Noth and Rehbein (2019) reveal a contrary positive impact. Based on these contradictory findings, we develop our first prediction as follows:

HP1

The market impact of natural disasters is more negative for local industries than the non-local industries.

Following the literature (Korniotis and Kumar 2013; Dessaint and Matray 2017), we use firms’ headquarter location to define local industry portfolios such that they are comprised of only those firms having headquarters located in the disaster-hit state.Footnote 5 Dessaint and Matray (2017) argue that data for production units are not readily available so they have to rely on the assumption that on average, such units are located in the same place as the headquarters (see, e.g., Chaney et al. 2012). Hosono et al. (2016) also suggest that non-local banks are attractive for stakeholders, whereas Strobl (2011) finds that tropical storms negatively affect the economic development of U.S. coastal areas more than other areas.

Although we expect a higher negative impact on local industries than non-local industries, Fink and Fink (2013) motivate us to think critically about firm size. They show that equity returns of oil refineries are positively related to hurricanes, and large firms use their geographic diversification and idle capacity to benefit from this situation when compared to small firms. Interestingly, they do not find any negative impact on small firms either, in fact, small firms do not respond to the hurricanes at all. Whereas Basker and Miranda (2014) report negative impacts of hurricane Katrina on young and small firms, respectively. As evident for the cited studies, the current literature disagrees on the role of firm size in the equity–natural disaster relationship and does not provide any evidence of importance that constituent firms’ size can have in explaining the variation in this relationship. Therefore, we predict that natural disasters affect industries, comprising of small firms, to a greater extent due to limited capital/infrastructure resulting in reduced/no business operation. This motivates our next prediction:

HP2

The market impact of natural disasters is more negative for industries comprising of small firms than those comprising of big firms.

In this way, we explore a firm’s location and size in explaining the reactions of respective industries to natural disasters. Furthermore, we extend our study and examine whether disaster magnitude, based on either human or financial loss, can explain the variation in the industry responses. Prior literature suggests that natural disasters are damaging to the economy in general (see, e.g., Bosker et al. 2019), but few studies argue that some economic sectors might benefit from higher intensity of the natural disasters. Fox et al. (2009) and Gu and Nyak (2016) find that deadly natural disasters lead to drug shortages, and Mark and Jason (2017) imply that such shortage increases drug prices. As evident from the literature, there is a disagreement on whether and when large natural disasters have negative impact on equities. With this in mind, we conjecture a final prediction as follows:

HP3

The market impact of natural disasters for the industries is more pronounced with larger disaster events.

3 Data and research method

3.1 Data description

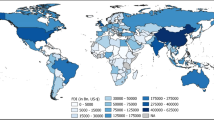

Our sample period covers January 1, 1987, to December 31, 2018.Footnote 6 We source data for US natural disasters from Emergency Disaster Database (EM-DAT) maintained by the Centre for Research in the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); many previous studies use this database considering its authenticity (Rahman 2018; Skidmore and Toya 2002; Cavallo et al. 2013).

We use a sample of 271 natural disasters for which data for specific start and end dates are available and which are not long lasting (i.e., for days or weeks but not months/years) during the period under study. To be included in our sample, the events must meet a minimum criterion related to human loss (at least 10 people perished or at least 100 are affected) and/or economic loss of USD 1 million and above. Additionally, we collect data for the USA’ common stocks from the Centre for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and headquarter locations from Compustat. Finally, we construct industry portfolios and disaster severity measures in the next section to relate them to the natural disasters.

3.2 Portfolio construction

3.2.1 Location-based industry portfolios

We construct two sets of industry portfolios using firms headquarter location. For the first set of portfolios (local industry portfolios), we apply an additional filter of “headquarter location” to the Standard Industry Classification (SIC) codes corresponding to the Kenneth French 49 Industry portfolios.Footnote 7 We identify firms having headquarters in the disaster-affected zone to constitute our 49 FF local industry portfolios. The second set of industry portfolios (non-local industry portfolios) comprises only those companies with headquarters outside the disaster-affected zone. We only use observations for which geographic locations of both the firm and disaster are available and exclude any firms with missing observations.

3.2.2 Size-based industry portfolios

Following the existing literature, we also divide the local portfolios according to the size of the firms, based on market capitalization (e.g., Fink and Fink 2013). Using median values as the dividing line, the 49 FF local industry portfolios are split into small firms versus big firms.

3.2.3 Disaster magnitude

To test our third prediction (HP3), we use human and financial losses as two alternative measures of the severity of the natural disasters. We sort natural disasters for both financial and human loss and partition at median values to designate high and low magnitude of loss. We then divide the disasters into four subgroups based on high (low) human (financial) loss and conduct an event study analysis for each case. We only use the disaster observations for which EM-DAT reports both human and financial losses and exclude observations where data for any of the disaster measures are missing.

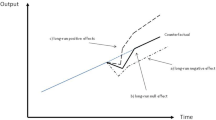

3.3 Hypotheses testing

Following the existing literature (see, e.g. Guo et al. 2020; MacKinlay 1997), we test our predictions using a standard event study method to estimate the effect of natural disaster on a wide range of industry portfolios, as described above, using equally weighted portfolios.Footnote 8 We use alternative windows for respective disasters such that for any disaster, the shortest window is (0, + 1) that captures the immediate response of equities and later we extend our analysis up to day thirty (+ 30) to examine the response over a longer time window. Some studies (see, e.g., Cooper et al. 2001) support the importance of confounding events in the event studies. However, Kothari and Warner (2007) argue that such events effect long-horizon event studies (generally one year). Our event windows extend to only thirty several days around the event, so we do not expect confounding events to drive our results. We use Fama French Five Factor Model (Fama and French 2015) to estimate abnormal returns presented in this study, however, in unreported experiment, we conduct a range of sensitivity checks, and the results are robust.Footnote 9

We use the widely accepted Boehmer et al. (1991) standardized cross-sectional z score to test the significance of the estimates and adjust for cross-sectional variance (Kolari and Pynnönen 2010). Marks and Musumeci (2017) examine the statistical power of different significance tests used in event studies and find that the Boehmer et al. (1991) measure performs well across a wide range of scenarios.

4 Results

We only discuss the industries generating statistically significant cumulative abnormal returns (at least at the 10% level).

4.1 Location effect

This section discusses the price reaction of local and non-local equity industries in the event of natural disasters. We report estimates of cumulative abnormal returns of local industries compared to non-local industries in Table 1 and test for the differences. We first discuss immediate market response (0, + 1) of local and non-local industry portfolios followed by longer window analysis (0, + 30) in the following sections and test our first prediction that the market impact of natural disasters is more negative for local firms than for non-local firms.

4.1.1 Immediate market reaction

Table 1 (Panel A) presents the cumulative abnormal returns of U.S. industry sectors in the first two days of the natural disasters’ occurrence. Results show that local industries earn a cumulative abnormal return of − 0.02 percent, whereas their counterpart non-local industries demonstrate a 0.02 percent return. Thus, there are negligible immediate effects and negligible differences between local and non-local industries at this aggregate level. These findings have no discernible support for our prediction (HP1) that the impacts of natural disasters for local industries are more negative than non-local industries.

An industry-wise breakdown indicates that equities are slow to react to natural disasters and very few industries show a statistically significant response. These results are aligned with Kaplanski and Levy (2010), who suggest that equities do not respond quickly to negative events. Moreover, we find variation in the market across different industries, and the results further show that responses are not always negative to such events; for example, Local Medical Equipment earns + 0.08 percent CAR (0, + 1), whereas Local Fun and Entertainment earns − 0.13 percent over the same event window.

Table 1 reports similar results for the non-local industries; for example, Construction earns 0.07 percent (CAR0, + 1), whereas Gold loses 0.13 percent abnormal return over the same window. Loayza et al. (2012), Cole et al. (2014), and Carleton and Hsiang (2016) suggest varying effects of natural disasters on respective economic sectors depending on the severity/class of natural disasters and the industry type. It is worth noting that in most cases, abnormal profits of local industries are not statistically different from those of non-local industries in the first two days of the disaster (0, + 1). Kaplanski and Levy (2010), who examine the impact of aviation disasters on stock returns, argue that investors do not quickly react to the initial news announcing the event occurrence; instead, they are more likely to wait and respond to the later detailed news coverage carrying nuanced information about the extent of damage.

4.1.2 Post-event market reactions to natural disasters

Table 1 (Panel B) shows that local industries earn 0.02 percent CAR (0, + 30), which is 0.18 percent less than that for non-local industries. This finding supports our first prediction of less negative impacts on non-local industry portfolios. Likewise, industry-wise analysis reveals that sixty-one percent of non-local industries outperform local industries, conforming to our first prediction. Notably, non-local Gold, Books, and Telecom industries earn 1.30 percent, 0.20 percent, and 0.14 percent thirty-day abnormal returns, respectively. These returns are 2.13 percent, 0.90 percent, and 0.74 percent higher than their counterpart local industries, and the differences are statistically significant. However, in several instances, local industries lose less than non-local industries; for example, Local Medical Equipment earns 0.27 percent higher thirty-day cumulative abnormal return than non-local medical equipment firms. These results negate our prediction of less negative impacts for non-local industry portfolios for several industries. Hence, we conclude that location is an important factor and taken together with industry type, and these findings will assist practitioners develop predictable disaster impact patterns.

4.2 Size effect

This section discusses the price reaction of industries, conditioned on constituent firms’ size, in the event of natural disasters. We report estimates in Table 2.

4.2.1 Immediate market reaction

Table 2 (Panel A) presents the cumulative abnormal returns of U.S. industry sectors in the first two days after the natural disaster. The results show a small but positive difference between the price reaction of big and small firms, indicating less negative impacts for big firms. These findings weakly conform to our prediction (HP2) that the impact of natural disasters for small firms is more negative than that experienced by big firms. However, an industry-wise breakdown indicates a very sluggish immediate response, particularly for big firms. Results show that only a quarter of industries (comprising large firms) respond as opposed to the 50 percent response rate of their counterpart small industries. We argue that investors interested in small firms overreact and price the catastrophes earlier than big firms.

4.2.2 Post-event market reactions to natural disasters

We find an increasing number of industries responding to natural disasters over the longer window. Table 2 (Panel B) indicates that big firms earn -0.08 percent CAR (0, + 30), which is 46 basis points more than the cumulative abnormal return for small industries, and the difference is statistically significant. Furthermore, industry-wise analysis shows that the market impact on 80 percent of the big firms is less negative than that for small firms, which supports our second prediction that big firms are less affected by natural disasters relative to small firms. Notably, big insurance companies earn 0.12 percent CAR (0, + 30), which is 61 basis points higher than small insurance firms (-0.49 percent). Similarly, big banks lose 6 basis points of CAR (0, + 30), whereas their counterpart small banks lose 42 basis points over the same event window. Table 2 (Panel B) reports similar results for respective small and big firms. Fink and Fink (2013) argue that large firms use their geographic diversification and idle capacity to benefit from catastrophic situations, compared to small firms. These findings conform to our prediction (HP2) of more negative impacts on small industry portfolios.

4.3 Disaster magnitude effect

4.3.1 Immediate market reaction

Table 3 (Panel A) presents the cumulative abnormal returns of U.S. industry sectors in the post-disaster period (intermediate-level disasters) two days after the disaster hits (CAR 0, + 1). Results indicate that human and financial losses are important; however, they do not affect equities in a similar fashion, and the impacts vary across industries. For instance, in Table 3 (Panel A), Gold earns 0.51 percent higher CAR (0, + 1) when human (financial) loss is low (high), whereas the Drugs industry reacts differently and earns higher abnormal return when human (financial) loss is high (low). Similarly, the Household Consumer sector performs better in the case of high human but low financial loss. We argue that the industry type in conjunction with the disaster severity can explain the magnitude and direction of equity price reaction. Practitioners can use these findings to predict the financial impacts on specific industries in the event of natural disasters by simply looking at the disaster severity in terms of human and financial losses.

Likewise, Table 3 (Panel B) reports CAR (0, + 1) of respective industries for the two extreme disaster severity levels (Low and High). The results show that the equity response depends on the industry type and the severity of the natural disaster. For example, Construction earns 46 basis points higher CAR (0, + 1) for extreme natural disasters compared to less damaging disasters. We argue that post-disaster reconstruction prospects earn such industries high stock returns in the event of damaging catastrophes (e.g., Potter et al. 2015; Schumpeter 1942). Gold retains its ‘safe haven’ property and earns 60 basis points higher returns in the case of highly damaging natural disasters relative to when damage is low. However, on the other hand, industries like Oil and Petroleum lose more when both human and financial losses are higher than when such losses are low. Table 3 reports results for all the 49 FF industries and partially supports the third prediction of more negative market impacts of larger natural disasters.

4.3.2 Post-event market reactions to natural disasters

We find an increasing number of industries responding to natural disasters over the longer window. Table 4 (Panel A) presents the results for intermediate disaster cases, whereas Panel B presents cumulative abnormal returns for extreme disaster cases. The industry-wise breakdown in Panel A suggests variation in the market impacts. Results show that industries related to health services like Drugs and Medical Equipment earn higher returns when human (financial) loss is high (low). Mark and Jason (2017) imply that shortage of drugs increases drug prices, whereas Fox et al. (2009) and Gu and Nyak (2016) suggest drug shortages are a consequence of natural disasters. On the other hand, Banks and Insurance industries, being financial based, lose more when the disaster causes high financial loss regardless of the magnitude of the human loss. Gold is again the best performer and earns 3.65 percent higher CAR (0, + 30) when financial (human) loss is high (low). Results for all industries are reported in Table 4 (Panel A).

Similarly, Table 4 (Panel B) compares CAR (0, + 30) of respective industries for the two extreme disaster severity levels (Low and High). Results show that equity response is related to the type of product/service the industry sells and the corresponding disaster-related human and financial losses. Our estimates indicate that the equity market earns 0.15 percent CAR (0, + 30) for less severe disasters, which are higher than the returns for more severe natural disasters. However, industries continue to react differently; Table 4 (Panel B) reports results for all the 49 FF industries. Notably, consistent with prior studies (see, e.g., Sakemoto 2018), Gold continues to be a ‘safe haven’ in both cases; however, it earns 89 basis points higher cumulative abnormal returns in case of high financial and human losses compared to when losses are low. Counter-intuitively, the Insurance industry benefits when losses are high relative to when they are low. Researchers suggest that following a disaster, demand for insurance coverage goes up and so does the premium (e.g., Ewing et al. 2006; Wang and Kutan 2013). Hence, insurance sector profits increase, yielding higher stock returns in this sector. On the other hand, other industries that experience more negative impacts of larger natural disasters include Mines, Oil and Petroleum, Real Estate, Transport, and Chips-Electronics. Results for these industries conform to our prediction of more negative impacts of larger disaster events. Generally, our findings suggest that different categories of natural disasters have a different impact on each industry, and these impacts vary across industries in line with the corresponding disasters’ severity.

5 Discussion

In general, the results show that local industry portfolios experience more negative impacts than non-local industries; however, not all industries follow this pattern. For example, the local Construction industry experiences abnormal losses over the thirty-day window, but the local Medical Equipment industry benefits. We suggest that location does matter, but the nature of the disaster and industry itself is also important; for example, Medical Equipment continues to perform well regardless of location and disaster as the defensive nature of the industry makes it resilient in such crisis situations. A few studies suggest that natural disasters lead to a shortage of supplies and unexpected increase in demand of such products.Footnote 11 This leads to price hikes and increases investor confidence regarding the performance of such industries in the aftermath of disasters. Hence, our findings provide the basis for diversification/hedging using the headquarters location of firms if natural disasters hit the U.S. Our findings partially support the first prediction of more negative impacts for local firms compared to non-local firms.

Likewise, firm size also plays a useful role in explaining the industry response to natural disasters. Our findings suggest that industries comprising big firms outperform industries consisting of small firms; this conforms to our second prediction. These results are consistent with Fink and Fink (2013) who find higher oil refinery returns for large firms relative to small firms in the event of hurricanes.

Finally, we examine the extent to which disaster magnitude, measured by human and financial loss, drives the equity market reaction. Our findings suggest that human and financial loss affects equities differently and mainly depends on the type of industry in which the firm operates. For instance, health care-related industries like Drugs perform better in the case of high human loss, while industries like Gold and Construction are better performers in the case of high financial losses. Overall, we find that analyzing the extent of loss and the industry the firm is operating in can help practitioners assess predictable equity reaction patterns.

5.1 Additional analysis

We provide multivariate analysis to support our main findings and set up a regression framework to analyze the cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) across a range of scenarios. In this section, we further narrow down our analysis and conjecture sub-predictions to critically analyze the combined role of location and size in driving the equity market reaction to natural disasters. Specifically, we combine the first two predictions, i.e., we add the size effect to our first prediction (HP1) of more negative disaster impacts for local firms than non-local firms and conjecture the first subset of predictions as follows:

HP1a

The market impact of natural disasters is more negative for local small firms than for non-local small firms.

HP1b

The market impact of natural disasters is more negative for local big firms than for non-local big firms.

Moreover, following the second prediction of the main analysis that small firms react more negatively than large firms, we add the location effect and propose a second subset of predictions such that:

HP2a

The market impact of natural disasters is more negative for small local firms than for big local firms.

HP2b

The market impact of natural disasters is more negative for small non-local firms than for big non-local firms.

It is worth noting that we test the aforementioned predictions for natural disasters of different magnitudes measured using human and financial losses.Footnote 12

5.2 Regression framework

We examine the role of location, firm size, and disaster-related human and financial losses in driving the equity market price reaction using the following equation:

CAR represents the cumulative abnormal return of the aggregate market over a specific window in the event of natural disasters. Variable Non-Local takes the value of one if the firm is located outside the disaster-affected area and zero otherwise. Local is a dummy variable that equals one for disaster-affected firms and zero otherwise. We assign variable Small a value of one for small-sized firms (based on market capitalization) and zero otherwise. Likewise, Medium takes the value of one for medium and Big takes value of one for big firms, respectively, and zero otherwise. \(\alpha\) represents the omitted case of local small firms, i.e., small firms located in the disaster-affected state(s). Furthermore, we divide natural disasters into four subsets based on financial and human losses (where FL is financial loss and HL is the human loss) and estimate the regressions for each subset of disasters. We independently sort meteorological disasters for both FL and HL, and partition at the median values to designate high and low magnitudes of loss. The 2 × 2 partition is derived from the four combined cases of high/low FL/HL. We use the regression framework to support our main findings and discuss the results in Sects. 5.2 and 5.3.Footnote 13

5.3 Location effect and firm size

In this section, we use a regression framework to support our main findings that the market impact of natural disasters is more negative for local small firms than for non-local firms and report our results in Table 5 (Panels A and B). The omitted case captured by the intercept term represents the local small firms. We see from the estimated intercept in the regression and positive coefficient for non-local firms that regardless of the disaster magnitude, local small firms are more negatively affected. Results in Panel A of Table 5 further indicate the economic impact of disasters is minimal in the first two days of the disasters relative to the longer window of thirty days in Panel B. Results for the full disaster sample (Panel B) suggest that non-local firms experience higher abnormal returns than local small firms, thus supporting our prediction (HP1a) that the market impact of natural disasters is more negative for local small firms than non-local small firms.

Likewise, we compare the impact for local and non-local big firms. Positive regression coefficients for Local × Big and Non-Local × Big suggest that in the event of natural disasters, big firms, regardless of location and disaster magnitude, experience higher abnormal returns relative to the base case, small-local firms. It is worth noting that the difference between local and non-local big firms is statically insignificant. This implies that for big firms, location is not that important. These results are consistent with Fink and Fink (2013) who attribute the positive impact of hurricanes on oil refinery returns to the firm’s large size. Our results further show that non-local big firms outperform local big firms for the disasters involving low human loss. Accordingly, these results negate our prediction (HP1b) of less negative effects for non-local big firms.

5.4 Size effect and location

In this section, we compare the market impact of natural disasters on local (non-local) small firms with local (non-local) large firms and test our predictions HP2a and HP2b. Table 5 (Panel B) presents a negative intercept (small local firms) but a positive coefficient for Local × Big (large local firms) across all the disaster samples. This indicates that local small firms are more negatively affected by natural disasters. These results support our main findings that the market impact of natural disasters is more negative for small (local) firms than big (local) firm. We observe a similar trend for non-local small and non-local big firms where small (non-local) firms have a smaller coefficient than their counterpart big (non-local) firms. These results support our prediction HP2b across all disaster subsets, as the estimated coefficients for small non-local firms are smaller than big non-local firms.

6 Conclusion

Investigating the importance of location and size in explaining the market reaction of U.S stocks to natural disasters of different severity is a contribution to the natural disaster–equity literature. Several results of this study are notable. First, location in conjunction with the industry type plays an important role in explaining the equity market reaction. Our results suggest that not all local (non-local) industries are more (less) negatively affected. These findings help us understand possible predictable patterns of equity market reaction based on firm location and industry. Second, equities are slow to react to natural disasters. Our results are consistent with the existing literature that supports a sluggish response to the initial bad news relative to later loss stemming from related information-carrying news of the extent of damages (Kaplanski and Levy 2010).

Third, constituent firm size is another key factor that can help unpack the natural disaster–equity reaction relationship. Our findings suggest that generally, large firms outperform small firms in the event of natural disasters and provide relatively safer investment opportunities. Fourth, industries react differently to disasters of different magnitudes, and the response also varies across the different disaster measures. Some industries (like Drugs) benefit when financial (human) loss is low (high), whereas others (like Gold) show abnormal returns when the financial (human) loss is high (low). These results are consistent with the literature that suggest hike in drug prices in times of disaster (Gu et al. 2016) and safe haven property of gold in financial turmoil (Sari et al. 2010). We conclude that the industry in which the firm operates has a big part to play in the magnitude and direction (positive, negative, or zero) of their equity reaction. Finally, our multivariate regression analysis indicates that regardless of the firm location and disaster magnitude, large firms are less negatively affected.

Our study has several implications for investors, and other stakeholders alike. First, for investors, our study provides the basis for the development of equity reaction prediction in the event of disaster events, using firm and disaster location and size, to mitigate potential disaster risk. Second, our finds help policy makers (government agencies), to tailor targeted (not mass) financial assistance packages for the firms, by just looking at the industries the firms relate to and corresponding firm and disaster characteristics. Finally, the funding institutions, like banks, can assess the credit needs of the firms in disaster-hit areas beforehand.

Given the increasing frequency of natural disasters over the last few years, it is important that we continue to examine the natural disaster–financial market relationship and unpack the factors that can help investors, mangers and policy makers mitigate the disaster risk. This study analyzes the market impact of domestic natural disasters on U.S equities; however, disasters happening around the world, particularly those affecting U.S. trading partner countries (like China and Japan), can also affect U.S equity markets’ performance. Similarly, this study is limited to direct (immediate) disaster damages, and future research can study indirect (long term) negative effects to proxy disaster magnitude. Furthermore, this study focuses on size and location of the firms, whereas future research can examine other firm characteristics too. For example, the feature of being part of a multinational group or a company being highly diversified in many different sectors. We leave these ideas for future researchers to explore.

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

Subscription-based database has been used, and restrictions on data sharing are in place.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

N/A.

Notes

The Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) defines natural disasters as “naturally occurring physical phenomena caused either by rapid or slow onset events which can be meteorological (extreme temperatures, cyclones and storms/wave surges), hydrological (avalanches and floods), climatological (drought and wildfires), geophysical (earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis and volcanic activity) or biological (disease epidemics).”

Disaster damage data available at www.emdat.be.

We use Kenneth French 49 Industry portfolio definitions to construct our portfolios. SIC codes comprising each industry portfolio are available at: http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

Detailed mechanism for constructing local and non-industry portfolios is explained later in the methodology section.

Data for production units is commercially available for only a small number of firms (SIC codes 2000–3999) and is missing for all of the remaining firms/industries. Therefore, we follow the literature that use headquarter location to proxy firm location (e.g., Dessaint and Matray 2017).

The sample period is limited to 1987–2018 due to non-availability of firm location data prior to 1987.

SIC codes comprising each industry portfolio are available at: http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

Kothari et al. (1995) imply that low volatility and large market capitalization stocks tend to dominate the value-weighted stocks. By constructing equally weighted portfolios we make sure that the findings represent the entire industry and not just the small number of large cap stocks.

We use alternative models to estimate abnormal returns and the results are robust. Furthermore, following Zhu (2017) and Malik et al. (2020), we conduct several other sensitivity checks. In one experiment, we include the event(s) that happen earlier in the month and drop the event(s) happening later in the same month. Similarly, in another experiment, we analyze only the disaster events that are at least one month apart and exclude all disasters happening in the same month. We find that the results of these sensitivity checks are qualitatively the same to those reported in our study.

Fox et al. (2009) and Gu and Nyak (2016) suggest natural disasters as one of the major reasons for drug shortages.

We follow the method explained in Sect. 3.2 of this study and partition natural disasters into four subsets based on median human and financial loss values.

We control for year and industry effects in our regression analysis to draw a meaningful conclusion.

References

Basker E, Miranda J (2014) Taken by storm: business financing, survival, and contagion in the aftermath of hurricane katrina (No. 1406)

Belasen AR, Polachek SW (2008) How hurricanes affect wages and employment in local labor markets. Am Econ Rev 98(2):49–53

Boehmer E, Masumeci J, Poulsen AB (1991) Event-study methodology under conditions of event-induced variance. J Financ Econ 30(2):253–272

Bosker M, Garretsen H, Marlet G, van Woerkens C (2019) Nether lands: evidence on the price and perception of rare natural disasters. J Eur Econ Assoc 17(2):413–453

Botzen WW, Deschenes O, Sanders M (2019) The economic impacts of natural disasters: a review of models and empirical studies. Rev Environ Econo Policy 13(2):167–188

Bourdeau-Brien M, Kryzanowski L (2017) The impact of natural disasters on the stock returns and volatilities of local firms. Q Rev Econ Financ 63:259–270

Boustan LP, Kahn ME, Rhode PW, Yanguas ML (2017) The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in us counties: a century of data (No. w23410). National Bureau of Economic Research

Brammer S, Branicki L, Linnenluecke M, Smith T (2019) Grand challenges in management research: attributes, achievements, and advancement. Aust J Manag 44(4):517–533

Carleton TA, Hsiang SM (2016) Social and economic impacts of climate. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9837

Cavallo E, Galiani S, Noy I, Pantano J (2013) Catastrophic natural disasters and economic growth. Rev Econ Stat 95(5):1549–1561

Chaney T, Sraer D, Thesmar D (2012) The collateral channel: how real estate shocks affect corporate investment. Am Econ Rev 102(6):2381–2409

Cole M, Elliott R, Okubo T, Strobl E (2014) Natural disasters and the birth, life and death of plants: the case of the Kobe earthquake. IPAG Working Paper, 2104.

Cooper MJ, Dimitrov O, Rau PR (2001) A rose. com by any other name. J Financ 56(6):2371–2388

Dessaint O, Matray A (2017) Do managers overreact to salient risks? Evidence from hurricane strikes. J Financ Econ 126(1):97–121

Donaldson M, Goodchild JH (2017) Drug shortages: how do we run out of salt water? Gen Dent 65(5):10–13

Ewing BT, Hein SE, Kruse JB (2006) insurer stock price responses to hurricane floyd: an event study analysis using storm characteristics. Weather Forecast 21:395–407

Fink JD, Fink KE (2013) Hurricane forecast revisions and petroleum refiner equity returns. Energy Econ 38:1–11

Fama EF, French KR (2015) A five-factor asset pricing model. J Financ Econ 116(1):1–22

Fox ER, Birt A, James KB, Kokko H, Salverson S, Soflin DL (2009) ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm 66(15):1399–1406

Gu A, Patel D, Nayak R (2016) Drug shortages. Pharmaceutical Public Policy, 151

Guo M, Kuai Y, Liu X (2020) Stock market response to environmental policies: evidence from heavily polluting firms in China. Econ Model 86:306–316

Hosono K, Miyakawa D, Uchino T, Hazama M, Ono A, Uchida H, Uesugi I (2016) Natural disasters, damage to banks, and firm investment. Int Econ Rev 57(4):1335–1370

Jongman B, Hochrainer-Stigler S, Feyen L, Aerts JCJH, Reinhard Mechler WJ, Botzen W, Bouwer LM, Pflug G, Rojas R, Ward PJ (2014) Increasing stress on disaster-risk finance due to large floods. Nature Climate Change 4(4):264–268

Kaplanski G, Levy H (2010) Sentiment and stock prices: the case of aviation disasters. J Financ Econ 95(2):174–201

Kolari JW, Pynnönen S (2010) Event study testing with cross-sectional correlation of abnormal returns. Rev Financ Stud 23(11):3996–4025

Korniotis GM, Kumar A (2013) State-level business cycles and local return predictability. J Financ 68(3):1037–1096

Kothari SP, Warner JB (2007) Econometrics of event studies. In: Handbook of empirical corporate finance (pp. 3–36). Elsevier

Loayza NV, Olaberria E, Rigolini J, Christiaensen L (2012) Natural disasters and growth: going beyond the averages. World Dev 40(7):1317–1336

MacKinlay AC (1997) Event studies in economics and finance. J Econ Lit 35(1):13–39

Malik IA, Faff RW, Chan KF (2020) Market response of US equities to domestic natural disasters: industry-based evidence. Account Financ 60(4):3875–3904

Marks JM, Musumeci J (2017) Misspecification in event studies. J Corp Finan 45:333–341

Noth F, Rehbein O (2019) Badly hurt? Natural disasters and direct firm effects. Financ Res Lett 28:254–258

Pearson MM, Hickman TM, Lawrence KE (2011) Retail recovery from natural disasters: New Orleans versus eight other United States disaster sites. Int Rev Retail Distrib Consum Res 21(5):415–444

Potter SH, Becker JS, Johnston DM, Rossiter KP (2015) An overview of the impacts of the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 14:6–14

Rahman MH (2018) Earthquakes don’t kill, built environment does: evidence from cross-country data. Econ Model 70:458–468

Sakemoto R (2018) Do precious and industrial metals act as hedges and safe havens for currency portfolios? Financ Res Lett 24:256–262

Sari R, Hammoudeh S, Soytas U (2010) Dynamics of oil price, precious metal prices, and exchange rate. Energy Econ 32(2):351–362

Schumpeter J (1942) Creative destruction. Capitalism, socialism and democracy, 82–5

Schüwer U, Lambert C, Noth F (2019) How do banks react to catastrophic events? Evidence from Hurricane Katrina. Rev Financ 23(1):75–116

Shan L, Gong SX (2012) Investor sentiment and stock returns: Wenchuan Earthquake. Financ Res Lett 9(1):36–47

Skidmore M, Toya H (2002) Do natural disasters promote long-run growth? Econ Inq 40(4):664–687

Strobl E (2011) The economic growth impact of hurricanes: evidence from US coastal counties. Rev Econ Stat 93(2):575–589

Ulubaşoğlu MA, Rahman MH, Önder YK, Chen Y, Rajabifard A (2019) Floods, bushfires and sectoral economic output in Australia, 1978–2014. Econ Record 95(308):58–80

Wang L, Kutan AM (2013) The impact of natural disasters on stock markets: evidence from Japan and the US. Comp Econ Stud 55:672–686

Wasileski G, Rodríguez H, Diaz W (2011) Business closure and relocation: a comparative analysis of the Loma Prieta earthquake and Hurricane Andrew. Disasters 35(1):102–129

Worthington A, Valadkhani A (2004) Measuring the impact of natural disasters on capital markets: an empirical application using intervention analysis. Appl Econ 36(19):2177–2186

Zhu Y (2017) Call it good, bad or no news? The valuation effect of debt issues. Account Financ 57(4):1203–1229

Funding

N/A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No known conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malik, I.A., Faff, R. Industry market reaction to natural disasters: do firm characteristics and disaster magnitude matter?. Nat Hazards 111, 2963–2994 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05164-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05164-z