Abstract

To better explore and understand the public's perceptions of and attitudes toward emerging technologies and food products, we conducted a US-based focus group study centered on nanotechnology, nano-food, and nano-food labeling. Seven focus groups were conducted in seven locations in two different US metropolitan areas from September 2010 to January 2011. In addition to revealing context-specific data on already established risk and public perception factors, our goal was to inductively identify other nano-food perception factors of significance for consideration when analyzing why and how perceptions and attitudes are formed to nanotechnology in food. Two such factors that emerged—altruism and skepticism—are particularly interesting in that they may be situated between different theoretical frameworks that have been used for explaining perception and attitude. We argue that they may represent a convergence point among theories that each help explain different aspects of both how food nanotechnologies are perceived and why those perceptions are formed. In this paper, we first review theoretical frameworks for evaluating risk perception and attitudes toward emerging technologies, then review previous work on public perception of nanotechnology and nano-food, describe our qualitative content analysis results for public perception toward nano-food—focusing especially on altruism and skepticism, and discuss implications of these findings in terms of how public attitudes toward nano-food could be formed and understood. Finally, we propose that paying attention to these two factors may guide more responsible development of nano-food in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nanotechnology refers to a broad range of tools, techniques, and applications that involve the manipulation of matter at the nanometer scale (1 nm = 10−9 m) to produce a variety of useful novel physical, chemical, and biological properties that do not exist at larger scales (NNI 2014). Applications of nanotechnology span virtually all industries, with more than 1600 nanotechnology-based consumer products already on the global market (PEN 2014) and global revenues from nanomaterials and nano-enabled products forecasted to reach over $4 trillion by 2018 (Lux Research 2014). Given the substantial role of the consumer in this burgeoning market, there has been much recent attention devoted to understanding what the public thinks about nanotechnology and why.

One sector in which nanotechnology is already having a major impact—but for which public attitudes are under-explored—is food. Applications of nanotechnology in the area of food (also called nano-food or food nanotechnologies hereinafter) span the entire chain from production to consumption. Areas of nano-food research and development (R&D) broadly include: agricultural production systems (e.g., precision farming sensors, targeted agro-chemicals); flavor, texture, and nutrient alterations or enhancements; and packaging for increased freshness and shelf-life (i.e., for longer transport and storage) as well as for increased food safety (e.g., improved barrier impermeability, contamination sensors, tracking systems) (Kuzma and Verhage 2006; Chaudhry et al. 2008). While these applications are in varying stages of the R&D pipeline, the Project on Nanotechnologies' inventory of nano-products currently lists 105 nano-food and beverage products, a number which may well be an underestimate (Chun 2009) and which is expected to grow considerably (Chaudhry et al. 2008; House of Lords 2010) given the significant global investment in nano-food R&D (Berube 2006; Dudo et al. 2011; Kuzma and VerHage 2006).

As investments and R&D in nano-food grow, it is increasingly recognized that public and consumer attitudes toward nano-food products and nanotechnology more generally matter a great deal to the development of the industry. From an economic and market standpoint, consumer needs, preferences, and purchasing behaviors are drivers of R&D decisions, especially in industry. The public’s perceptions of the risks and benefits associated with nanotechnology and nano-food, as well as their confidence and trust in the institutions involved in the production and regulation of nano-food, are likely to be significant factors for consumer acceptance of nano-food products (Siegrist et al. 2007, 2008, 2009) and, thus, of paramount importance to sales success and the availability of investment funding. Equally, if not more importantly, are the ethical aspects of consumers’ acceptance and trust, which are closely related to their rights to know about and to choose whether and when to consume nano-food products (Throne-Holst and Strandbakken 2009). Furthermore, significant public controversies have surrounded other technologies applied to food production and food products, such as the controversies around the safety of recombinant bovine somatotropin, labeling of genetically engineered foods, pervasiveness of pesticide residues, and origins of mad cow disease (e.g., Powell and Leiss 2004). Food nanotechnology is destined to be affected by consumers’ memories of and experiences with these controversies.

Despite these observations, public perceptions of and attitudes toward food nanotechnologies among consumers from the United States remain an unexplored area with very few studies (Brown and Kuzma 2013; Zhuo et al. 2013). There are more studies with European consumers (Siegrist et al. 2007, 2008, 2009; Vandermoere et al. 2011; Bieberstein et al. 2013) and others addressing the topic as a secondary consideration to broader non-food nanotechnology issues (Pidgeon and Rogers-Hayden 2007; Burri and Bellucci 2008; Throne-Holst and Strandbakken 2009; Siegrist and Keller 2011). These studies mostly have relied on quantitative survey techniques that typically are not designed to uncover the underlying rationales and processes by which public perceptions and decisions are formed—especially in lesser studied and understood areas—as compared to non-survey techniques (Brown and Kuzma 2013; Morgan 1996). Although these prior studies have begun to address the question of what factors are influencing public perceptions of nano-food, they have shortcomings in explaining why people hold the beliefs that they do.

To better explore and understand public perceptions and attitudes through an inductive method based on conversations among consumers, we conducted a US-based focus group study centered on nanotechnology, nano-food, and nano-food labeling. In addition to producing nano-food context-specific data on already established risk and public perception factors, our goal was to inductively identify any other unique and as yet unidentified nano-food perception factors of significance for consideration when analyzing why and how perceptions and attitudes are formed.

Two such factors that emerged—altruism and skepticism—are particularly interesting in that they situate nano-food among a number of different theoretical frameworks that have been used for explaining perception and attitude in a variety of contexts. Stated otherwise, altruism and skepticism are significant findings in that they represent a convergence point among theories that each help explain different aspects of both how food nanotechnologies are perceived and how those perceptions may be formed.

In this paper, we first review some of the theoretical frameworks for evaluating technological perceptions and attitudes and literature on the concepts of skepticism and altruism. We then describe our data collection and analysis methodologies of nano-food focus groups in the United States. Finally, we describe qualitative content analysis results for public perception toward nano-food—focusing especially on altruism and skepticism—and discuss implications in terms of how public attitudes toward nano-food are formed and understood.

Theories of perception and attitude

There exists a massive literature on consumer perception and attitude across a range of topics, technologies, products, and disciplines. Within this literature, the terms perception and attitude are assigned a variety of stated and implied definitions and, often, are regarded as synonymous. Further complicating the matter are related concepts such as social acceptance and consumer behavior which abut and overlap with some aspects of perception and attitude. For the purposes of this study, perception refers to how an individual or members of the public regard or feel about something that presents uncertain or ambiguous risks and benefits based on stimuli and information they receive from a variety of sources and how they interpret that stimuli and information through a variety of sensory, affective, cognitive, psychosocial, experiential, cultural, and mental processes. Attitude, by contrast, refers to the way in which an individual or the public is predisposed to act in a particular situation based on their perception (Schiff 1970).

Several different models attempt to explain the processes and factors that contribute to perceptions of risks and benefits for technologies and their products. One is the psychometric paradigm which focuses on identifying those aspects of a risk (e.g., newness, dreadedness, uncertainty, voluntariness, magnitude) that influence individuals' affect and emotion which then influence perceptions of that risk and ultimately judgments and decisions about that risk (Fischhoff et al. 1978). In addition to these risk factors, the psychometric paradigm also relies on a lengthy list of heuristics and cognitive biases that seek to explain how individuals evaluate new or ambiguous information about risks through common “mental shortcuts” such as referring to familiar experiences or discounting unfavorable outcomes. Stated otherwise, the psychometric approach “seeks to explain differences in how risks are perceived rather than differences in how individuals perceive risks” (Slimak and Dietz 2006, p. 1689). Thus, it follows that the psychometric approach has great descriptive and predictive value with respect to new risks and risk events and, as such, often has been used to empirically study perceptions of emerging technologies.

Beyond the psychometric paradigm and its emphasis on risk factors, there are also a number of sociological and cultural frameworks for risk perception that emphasize the role of social factors, norms, and values. One set of frameworks is based on the notion that individuals are often ill-equipped to accurately judge risks based on personal experience and, as such, rely on social networks and contracts to provide information about and to manage risks (Rohrmann and Renn 2000; Tucker and Ferson 2008). Consequently, trust and confidence in those social networks and contracts (i.e., the market, the political system, the regulatory system, news media, social groups) play an important role in perceptions of risk, especially when those risks are new, uncertain, or ambiguous. Beyond mere perception, trust and confidence have also been shown to influence people’s reactions to risk (for example, lack of trust in industry’s ability to handle risk is associated with greater levels of political activism) (Rohrmann and Renn 2000). One related theory is the social amplification of risk framework (SARF) which holds that the intermediaries through which individuals receive risk information (e.g., media, government, industry, advertising, social groups, etc.) can either amplify that information such that it receives greater public attention or attenuate it such that it does not (Kasperson et al. 1988).

While the approaches above are helpful for explaining the factors and mechanisms that cause different risks to be perceived differently across individuals, they are largely limited in explaining why those factors and mechanisms influence individuals’ risk perceptions (WÅhlberg 2001; Slimak and Dietz 2006). For instance, psychometric factors have been shown to explain only 20 % of the variance in risk perceptions among individuals as compared to 60–80 % of the variance among types of risks (Sjöberg 2000). The psychometric approach is regarded by several scholars as poorly-suited for evaluating differences in the perceptions of ecological risks and environmentally significant behaviors (for example, support for nuclear energy or recycling), which appear to be significantly more attributable to individual differences in value orientation (Slimak and Dietz 2006; De Groot and Steg 2008; De Groot et al. 2013; Hopper and Nielsen 1991).

Numerous studies have demonstrated that values significantly effect and are predictive of beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward risk and benefits (Stern 2000; Stern and Dietz 1994; Thøgersen and Ölander 2002). Others have described how values function when an individual is confronted with a novel risk situation or is in the position to choose whether to support a new technology or policy as follows: “The multistep model posits that core values are relatively stable over the course of an individual’s life, providing a basic referent for action, including assessing and making use of or discarding new information.” (Whitfield et al. 2009). Some studies have also shown that values play a significant role in trust—the more closely aligned an individual’s values are with those of institutions responsible for managing a risk, the more trust he or she will have in those institutions (Earle et al. 2007; Poortinga and Pidgeon 2003; Whitfield et al. 2009).

Related to values that people hold, the cultural theory of risk and cultural cognition of risk are two prominent and related approaches to understanding risk perception that emphasize the role of cultural and group affiliations. These approaches come closest perhaps to understanding the “why” of risk perception. According to cultural theory, differences in risk perception arise from differences in individuals’ views of the world and ways of living (Douglas and Wildavsky 1982). Two cross-cutting dimensions or axes, egalitarian versus hierarchical and communal versus individualistic, were used to describe four predominant cultural ways of life and supporting worldviews. An individual's worldview helps determine which risks he or she regards as worth accepting in order to achieve his or her ascribed-to cultural way of life. These worldviews have since been tested for a variety of environmental, health, and technological risks. For example, Douglas and Wildavsky (1982) suggest that adherents of an egalitarian–collectivist worldview tend to acknowledge environmental risks in order to advocate against social institutions that produce inequality, while adherents of an individualistic-hierarchical worldview tend to dismiss environmental risks in order to prevent interference with private control of activities and to defend those imbued with authority.

The related cultural cognition of risk connects the cultural theory of risk with the psychometric approach by positing that psychometric factors are the mechanisms by which cultural worldviews influence risk perceptions. Stated otherwise, various psychological processes are responsible for how individuals form their beliefs about risks such that those beliefs match their worldviews. Mechanisms of translating cultural worldviews to risk perception include identity-protective cognition; biased assimilation and group polarization; cultural credibility; cultural availability; and cultural identity affirmation, which relate to believing, seeking, or paying attention to risk information that supports one's own worldview or is conveyed by people with matching worldviews (Kahan 2012). In particular, cultural cognition of risk has taken foot in the study of emerging technologies such as nanotechnology. For example, Kahan et al. (2009) demonstrated that cultural cognition explains the majority of the differences in nanotechnology (not specific to nano-food, however) risk perception in the United States.

How cultural cognition and its mechanisms of translation relate to the characteristics of risk important under the psychometric paradigm (dread, familiarity, control, etc.) is not clear (Kahan 2012). We will return to a discussion of this in the context of skepticism and altruism for nano-food in the final section of this article. For now, having summarized some of the approaches to evaluating perceptions and attitudes, we turn to the current literature on specific perceptions and attitudes toward food nanotechnologies.

Nano-food perceptions and attitudes

It is mostly consistent across nanotechnology perception and attitude studies that a significant percentage of the public has little or no familiarity with nanotechnology and that even those with some familiarity are often unsure about whether the risks of nanotechnology outweigh the benefits or vice versa (Satterfield et al. 2009). Indeed, familiarity with and judgments of risks versus benefits have been a central focus of most of these studies as the dominant approach has been to build on the psychometric risk paradigm by identifying risk characteristics and heuristics that demonstrate effects on nanotechnology perceptions and attitudes. Among the psychometric and heuristic factors found to significantly have such effects are media exposure, framing effects, attitudes toward science and technology, intuitive toxicology, perceived naturalness, trust in regulations and risk management (Satterfield et al. 2009). Some studies have also found income, education, and religiosity to have a significant effect on perceptions of nano, while other studies have divergently found political leanings, race, age, and gender to be both significant and insignificant factors (Kahan et al. 2009; Satterfield et al. 2009).

Despite this array of nano perception factors found in the literature, there exists a knowledge gap about perceptions and attitudes toward particular nanotechnology applications. Foods containing, produced with, or packaged in materials containing nanomaterials (nano-food products) are an important area with limited perception and attitude research, especially in the United States (Cook and Fairweather 2007; Siegrist et al. 2007; Brown and Kuzma 2013). Even more paltry is the state of research on nano-food labeling attitudes, with only a handful of studies having addressed the issue, mostly with survey techniques and as a secondary consideration in conjunction with other non-food nano issues (Pidgeon and Rogers-Hayden 2007; Burri and Bellucci 2008; Throne-Holst and Strandbakken 2009; Siegrist and Keller 2011; Brown and Kuzma 2013). From a practical standpoint, poor understanding of public perceptions and attitudes creates a significant challenge for the fair and effective development of the nano-food industry. In this regard, we are referring to concerns about respecting the public’s view as a stakeholder in the development of nano-food and of nanotechnology more generally, as well as concerns about the success and continued advancement of nano-food and nanotechnology that may hinge on the public’s acceptance of such products (Köhler and Som 2008; Macoubrie 2006; Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering 2004).

Despite this, we are aware of only a few studies addressing perceived risks and benefits in the context of specific nano-food applications. Studies in the EU found that perceived naturalness and trust in the food industry, scientists, and consumer protection agencies are key factors influencing risk/benefit perceptions and acceptance of nano-food products (Frewer et al. 2011; Fischer et al. 2013; Siegrist et al. 2007, 2008). These studies also report that, from a valence standpoint, the public in the EU is hesitant to accept food containing or processed with nanotechnology and food packaging containing nanomaterials, albeit the latter is perceived as more beneficial than the former (Siegrist et al. 2007; Gupta et al. 2012). Similarly, consumers’ willingness to buy hypothetical products with added health benefits resulting from nanomaterial additives have been found to be lower as compared to products with similar benefits from natural additives, even though higher as compared to products with no additional health benefit at all (Siegrist et al. 2009). Siegrist et al. (2007) additionally constructed a model in which consumers’ social trust in the institutions and organizations comprising the food industry moderated their affect toward nano-food information which, in turn, fed into benefit and risk perceptions. Greater social trust in nano-food producers and perceptions of benefits had a positive impact on willingness to buy that outpaced the negative impact of perceived risks.

In light of the above results, we set out to explore U.S. consumer attitudes in conversational settings during which information about nanotechnology and nanotechnology in food was provided in stages followed by open-ended questions and then conversations among participants. In a prior analysis describing results from these focus groups, we reported on consumers' desires for nano-food labeling and acceptance of different nano-food products, as well as the need for more information about nano-food and trusted sources to manage labeling (Brown and Kuzma 2013). In addition to directly addressing these policy questions, we also designed the focus groups to look for risk perception factors already identified in the literature for nano-food (e.g., trust, benefits) and uncover additional risk perception factors or influences on consumer attitudes better revealed by qualitative methods. This paper presents and describes two novel perception factors for nano-food that arose from the focus groups, skepticism and altruism, and situates them within the context of existing risk perception theories. We introduce previous literature about these factors below, and then describe the methods and results of our analysis. In closing, we suggest a model for bridging psychometric and cultural theories of risk perception with these factors. This model should be considered for testing in future studies on technologies and risk perceptions.

Defining altruism

After we identified skepticism and altruism as potentially important and interesting perception themes for food nanotechnology (see “Results and discussion” section below), we conducted a literature search on whether and how these concepts have been discussed in the literature with regard to risk perception. Below we present the results of these searches and how we frame and define these terms for our subsequent analysis of the focus group conversations.

As a broad concept, altruism can be thought of as regard or affirmative action for the well-being of another. The concept of altruism pervades numerous disciplinary areas, including ethics, anthropology, biology, economics, psychology, and religious philosophies, among others. However, the conceptual details of altruism can vary quite significantly both within and across these different disciplines. Depending on the context, altruism can alternatively or collectively refer to mere emotional concern versus specific motivation or action for the well-being of others, mere selflessness versus self-sacrifice, an aspirational virtue versus a socially imposed duty, or an individual ethic versus a neurobiological trait. For example, the Oxford English Dictionary provides the following definition for altruism: “1. Disinterested or selfless concern for the well-being of others, esp. as a principle of action. Opposed to selfishness, egoism, or (in early use) egotism.”

Schwartz (1977) describes altruism as “intentions or purposes to benefit another as an expression of internal values, without regard for the network of social and material reinforcements” and attributes all altruistic intentions to exposure to another’s need and any of three internal factors translating that exposure into an intent to help: “(1) arousal of emotion; (2) activation of social expectations; or (3) activation of self-expectations.” This conception of altruism as a value has been widely identified as a highly significant factor in explaining pro-environmental perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Higher altruism, as defined generally by concern for the welfare of other humans and species, has been shown to be correlated with a higher degree of concern for the environment (Stern et al. 1999; Dietz et al. 2005; Whitfield et al. 2009) and higher perceptions of environmental risk (Slimak and Dietz 2006). It has also been shown to correlate with less favorable perceptions of nuclear power technologies (Whitfield et al. 2009). Elsewhere, scholars have described similarly a prosocial value orientation, like altruism, in which it is desired to “optimiz[e] outcomes for others” as opposed to one’s self and which results in stronger pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors (de Goot and Steg 2008; see also Stern 2000).

Altruism has also been described within the psychometric framework for risk perception, though far less explicitly than in value-based frameworks. While they do not specifically use the term altruism, Slovic and Västfjäll (2010) argue that people’s intuitive feelings and affect are insensitive to large losses of life and associated natural and human disasters such as poverty, starvation, disease, and genocide and manifest as failures to respond to and act to alleviate such harms. They describe a “psychophysical numbing” defined by diminishing marginal affective response to increasing numbers of lives at stake. They further suggest that any positive feelings associated with altruistic acts are subsumed by negative feelings associated with knowing that those acts will not go far enough to help the large number in need, thereby negating the motivation to act. Thus, they argue that, in keeping various heuristics and cognitive biases, altruistic concerns and actions are more likely to target specifically known victims or high-profile stories to that are easily imaginable, memorable, or that resonate personally.

The concept of altruism has been well explored in economics literature pertaining to health and environmental risks and decision making. Cai et al. (2008) describe two types of altruism influencing willingness to pay, risk-averting behavior, and related allocations of resources. The first, paternalistic altruism, occurs when an individual derives utility from his/her own consumption of goods and from the goods consumed by others for which he or she is concerned. The second, non-paternalistic altruism, occurs when the utility of those for whom an individual is concerned is an argument of the individual’s own utility. Others have also described a third form, impure altruism, in which an individual further derives utility from the act of being altruistic, sometimes referred to as “warm glow” (Kahneman and Knetsch 1992; Andreoni 1990). Studies have demonstrated that altruism can significantly affect willingness to pay and risk-averting behaviors (Cai et al. 2008; Dickie and Gerking 2007; Khwaja et al. 2006; Jones-Lee 1991; Viscusi et al. 1988; among others), but as almost all of these studies have been either theoretical or, when empirical, done in the context of altruism toward family members such that this effect cannot be generalized. At least one study has shown that given the same risk information, parents tend to make higher predictions of risk for their children than for themselves again demonstrating a form of altruism among family (Cai et al. 2008).

One particularly relevant exception to the family focus of prior economic studies of altruism is Lusk et al.’s (2007) study on the effect of altruism on individuals’ decisions to purchase environmentally-certified pork products. In this study, the authors approached altruism as a psychometric construct and, using survey and psychometric scaling methods, measured individuals’ levels of altruism. The study results showed that “more altruistic individuals are willing to pay more for pork products with public good attributes than less altruistic individuals …[indicating] that private purchases of goods with public-good attributes are not simply a result of individuals’ perceptions of the ability to mitigate private risks such as food safety, but that individual are making private choices to affect public outcomes.”

For the purposes of this study, focus group comments were initially coded as invoking altruism when they demonstrated concern about or suggested action for the benefit or welfare of other individuals or groups, regardless of whether the individual included him or herself as part of the group benefited. Factors such as the underlying source, motivation, or personal cost of suggested altruistic actions were not taken into consideration for the purposes of initial coding, but are discussed below in the analysis of altruism. The coding included statements of altruism as general sentiments as well as calls for specific behavior or action. Without the ability to observe participant behavior outside of the discussions, statements invoking altruism are taken at face value, presenting a potential for altruistic behavior.

Defining skepticism

Defining skepticism for the purposes of coding was a much more challenging task. Skepticism is an imprecise word with variable meanings both in common usage and in academic parlance. Indeed, skepticism is part of a large cluster of words that includes doubt, incredulity, uncertainty, disbelief, mistrust, distrust, reservation, anxiety, and misgiving which are typically used to define one another and often used interchangeably without much nuance (Merriam-Webster online Thesaurus).

As a discrete concept, skepticism is perhaps best defined within philosophy as “some degree of doubt regarding claims that elsewhere are taken for granted” and, in its epistemological form, questions whether our beliefs are rational, justified, or sufficiently certain to constitute knowledge (Pritchard 2004). According to Klein (2010), skepticism differs from “ordinary incredulity” in that the latter presupposes that our knowledge or beliefs about something are sufficiently true to provide the basis for doubting or questioning claims that produce a conclusion in conflict with that knowledge or beliefs. As such, our doubt disappears once the claims being questioned are reconciled with our prior knowledge or beliefs. Skepticism, by contrast, problematizes claims on the basis that we do not or cannot have such knowledge as is necessary to settle our doubts as to a claim. Even if the questioned claims are reconciled with our prior knowledge or beliefs, doubt persists because the knowledge or beliefs are themselves suspect.

In recent years, there has developed a growing body of academic literature devoted to unpacking and refining the definitions of two similarly polysemic words, “trust” and “uncertainty,” that over time have acquired unique and significant meanings across a number of social science disciplines. The result has been a proliferation of definitional frameworks, typologies, and concept models attempting to elucidate the different meanings of these terms both in discipline-specific and inter-disciplinary contexts (e.g., McKnight and Chervany 2001; Marsh and Dibben 2005; Mishler and Rose 1997). While the term skepticism sometimes appears in literature on trust and uncertainty, it is seldom defined or differentiated from related terms. Furthermore, there have been scant studies dedicated to discussing whether skepticism is a component of trust or uncertainty or whether it has its own unique and significant social scientific meaning.

A few scholars have attempted to describe skepticism as a tangible idea applied to individual perceptions, but have not defined it as a unique phenomenon separate from trust or uncertainty. As an example, in an evaluation of public trust in social and political institutions in post-communist societies by Mishler and Rose (1997), respondents were asked to indicate their level of trust in several institutions on a scale of 1–7. Scores above a 6 were regarded as indicating trust, below 2 as indicating distrust, and between 3 and 5 as indicating skepticism. No further definition of skepticism was provided.

In another study of trust in government risk regulation, Poortinga and Pidgeon (2003) evaluated respondents’ answers to 11 statements describing various dimensions of trust in government (e.g., “the government is competent enough,” “the government is acting in the public interest”). Based on the survey results, the authors concluded that the responses to the 11 prompts revealed a framework for evaluating trust based on two dimensions: a “general trust” dimension concerned with respondents’ views on the government’s competence, care, fairness, and openness, and a “skepticism” component concerned with respondents’ views on the government’s credibility, reliability, and integrity. The study, however, did not define skepticism nor did it explain why they authors regarded credibility, reliability, and integrity as elements of skepticism.

In contrast, Taylor-Gooby (2006) describes skepticism as an emerging “more discriminatory” approach to trust resulting from a more educated and critical public. This skepticism is a result of a kind of “active trust” in response to “changed social and cultural circumstances.” The author highlights Giddens (1994), “in which self-confident and active citizens seek to interpret the views of different experts with varying claims to authority.” The author purports that in situations in which credibility and trust have degraded, skepticism may emerge as a means to fill the trust void or to restore the skeptic’s sense of control over the situation, which was previously relinquished to an expert.

Taken one step further, Taylor-Gooby (2006) terms this new wave of an informed and vocally active public as “new skepticism” and connects it to citizen–government relations. This new skepticism reflects ideas from Bauman (1998), where end users of government policy are treated more as independent consumers than dependent clients, and Blair (2003), in that informed that consumer choice is emphasized over top-down policy making, paving the way for greater social justice. In short, Taylor-Gooby (2006) argues that skepticism contributes to a stronger form of democratic engagement during deliberation of salient issues.

Skepticism therefore arises from one’s doubt regarding the factuality (i.e., reality, veracity, credibility, reliability), rationality, or justifiability of claims about events, institutions, relationships, processes, knowledge, or information that are elsewhere taken for granted. It relates to but is different from distrust in that it does not necessarily question whether someone or something can or should be trusted, but rather questions claims that are either ascribed to that someone or something or are not ascribed to anything specifically. Stated more directly, trust is often placed in something or someone, but skepticism is often not. Trust is ascribed to an actor (whether individual or institutional), whereas skepticism is not necessarily placed in an actor. Skepticism is broader and often system-wide, involving a questioning about whether events or attributes will exist as multiple parties or institutions believe or state. Feelings of skepticism may relate to events, processes, systems, or multiple institutions that are questioned. To illustrate, one who distrusts private sector risk assessment may doubt the reliability of such assessments by questioning the assessors’ true motives (distrusting them), while one who is skeptical may question the underlying assumption that risk assessment or its outcomes are useful in the first place (regardless of trust in the assessors). As such, skepticism also differs from uncertainty in that, while the later may be the result of a lack of knowledge or information, the former questions the nature of that knowledge or information (e.g., its ability to ever be obtained or its veracity or reliability) or how it can be handled, used, or communicated toward producing a particular outcome, even after the knowledge or information has been acquired.

Interestingly, we find support for this conception of skepticism within the literature on altruism. While studies have shown that close alignment between an individual’s value orientation and that of institutions responsible for managing a risk results in the individual having greater trust in those institutions, one such study found that for individuals with altruistic value orientations having greater trust in the institutions responsible for managing a risk did not reduce perceptions of that risk, possibly because these individuals question the power of these institutions to prevent risks from occurring (Whitfield et al. 2009). This doubt as to the presupposed belief that trustworthy risk management will in fact reduce risk is consistent with our approach to skepticism.

For the purposes of our focus groups, we define skepticism as a theme in statements or exchanges where there is a presence of doubt or questioning regarding the factuality (i.e., reality, veracity, credibility, reliability), rationality, or justifiability of claims about the nature, purported facts, or purported outcomes of events, institutions, relationships, processes, knowledge, or information that are elsewhere taken for granted. It often appeared not in relation to a particular organization or group (like trust would) but rather to the food system, government decision-making systems, and technology development systems operating as a whole. Importantly, we approach skepticism not as a behavior or act, but as an expressed idea, view, attitude, or disposition, making it suitable to identify within verbal expressions of opinion.

Below we describe our methodology for identifying skepticism and altruism in focus group conversations and then describe the manifestations of these concepts in relation to food nanotechnology.

Methodology

Elsewhere we have described in detail the methodology used for this study and its advantages over other techniques (Brown and Kuzma 2013). In summary, public perception studies of nanotechnology have, with a few exceptions, relied almost exclusively on quantitative, written surveys which, as a tool, are not best suited for topics that are not well understood. They also are often less effective at exposing the underlying complexities of the processes by which participants formulate ideas or make decisions. In contrast, focus groups facilitate idea generation, populating the pool of relevant concepts, and encourage nuanced conversations that can expose and elucidate complex rationales behind individuals’ preferences (Krueger and Casey 2009; Morgan 1996). Focus groups can also foster a so-called “group effect” in which hearing others’ thoughts potentially activates new ideas in the minds of other participants (Morgan and Krueger 1993; Carey 1994; Carey and Smith 1994). Thus, focus groups can help better reveal the process and components of decision making, as well as help identify potential connections and relationships between different ideas. Furthermore, focus groups can be combined with survey methods to impart the benefits of the latter (e.g., the ability to make statistical inferences). Focus groups have been identified as especially suitable for exploring the relationship between individuals’ “lived experiences” and their feelings, attitudes, and behaviors toward food (Rabiee 2004).

For this study, we conducted seven 90-min focus groups with seven to ten participants between September 2010 and January 2011 in the Minnesota cities of Minneapolis, Richfield, and Bloomington (Hennepin Country) and the North Carolina cities of Raleigh, Garner, and Cary (Wake County). The cities selected represent the main metropolitan city, the largest suburb, and a randomly selected city with between 30,000 and 60,000 residents within Hennepin and Wake counties.

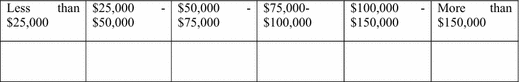

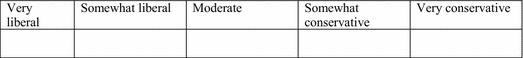

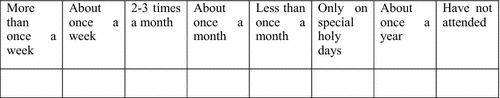

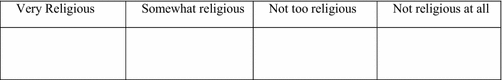

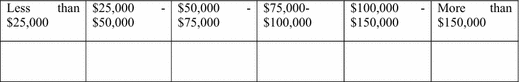

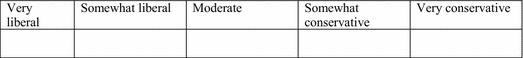

Participants were recruited with the goal of having an equal number of females and males in each group and matching the county’s demographic profile. Profiles were generated using census data and information from select city community centers and accounted for age, sex, race, education, family household income, and ideology (liberal, moderate, conservative) criteria. Individuals with prior background in or extensive knowledge of nanotechnology were excluded from participation.

A total of 56 participants partook in seven focus groups (n1 = 8, n2 = 10, n3 = 8, n4 = 7, n5 = 8, n6 = 7, n7 = 8). The demographic distribution contained more males (64 %, n = 36) versus females (36 %, n = 20); whites/Caucasians (84 %, n = 47) versus blacks/African Americans (11 %, n = 6) and Asians/Pacific Islanders (4 %, n = 2); and those with a post-graduate or professional degree (27 %, n = 15) versus college graduate (23 %, n = 13), some college (16 %, n = 9), high school graduate (14 %, n = 8), technical college graduate (7 %, n = 4), some high school (5 %, n = 3), some technical college (2 %, n = 1), and “Other” education (2 %, n = 1). Race/ethnicity and education had n = 1 and n = 2 “No Answer” responses, respectively. The most common age bracket was 50–60 (36 %, n = 20) compared to “Over 60” (23 %, n = 13), 41–49 (23 %, n = 13), 31–39 (7 %, n = 4), and “Under 30” (7 %, n = 4). Additionally, two provided “No Answer” for their ages.

Each group followed the same moderator-guided topic flow (Appendix 1) as follows:

-

Participants’ first thoughts about nanotechnology

-

Moderator’s reading of a prepared background statement about nanotechnology in general (Appendix 2)

-

Discussion of participants’ reactions to nanotechnology given the general background information

-

Moderator’s reading of a prepared background statement about nanotechnology in food (Appendix 2)

-

Discussion of participants’ reactions to nano-food given the nano-food background information

-

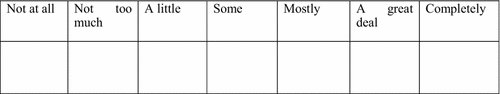

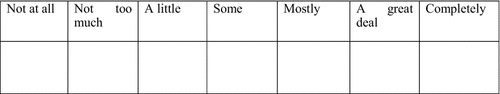

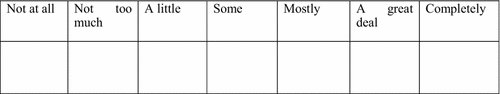

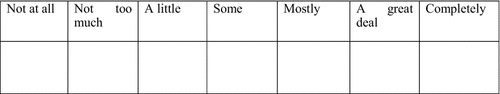

Individualized completion of in-group worksheets about willingness to use different nano-food products (Appendix 3) and subsequent group discussion

-

Discussion about nano-food product labeling

-

Final participant thoughts

-

Post survey (Appendix 4)

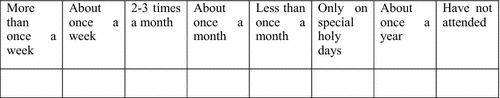

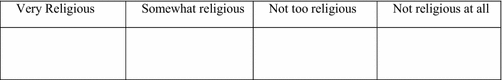

The in-group worksheets listed three broad nanotechnology food application areas: “food additive,” “food packaging,” and “food processing.” Space was provided for participants to list their perceived benefits and concerns and select their willingness to use each application and advertised benefit on a 1–5 scale. Participants were emailed post-focus groups surveys asking questions about issues related to nanotechnology in food and nanotechnology in general, including willingness to use, labeling, and regulatory issues.

Each focus group was audio recorded and included a moderator and a note-taker. Note-taking and audio recordings were used to construct transcripts for each group. Data sources from each focus group consisted of full transcripts, in-group worksheet responses (Appendix 3), and post-survey responses (Appendix 4). Focus group transcripts were analyzed using NVivo content analysis software by means of assigning topic or thematic codes to participants’ statements. All authors were involved in designing and executing the coding scheme. Author Brown developed the thematic coding scheme and did the initial coding. Author Fatehi also used these themes to code the data in NVivo. An inter-rater reliability score was derived using the percent agreement for whether two raters place a quote in a thematic category or not (p α,) (Gwet 2014). This score was 0.7 indicating 70 % initial agreement. The two primary raters met and resolved their differences in coding the data through a consensus process. Author Kuzma checked the results of this process and summarized them.

First, a large number of coding themes were generated based on typical terms arising in the emerging technologies and public perception literature (e.g., “trust,” “risks,” “benefits”). Second, numerous new coding themes were created inductively upon reading the focus group transcripts. A multi-level descriptive coding method was applied with most statements being assigned to one or more codes. Codes mostly fell into one of the three following categories: topic, intent, or a combination of both. Topic codes reference a specific subject raised by the participant, while intent codes were additionally assigned when some sort of preference or recommendation was supplied. Since most statements involved preference or views regarding one or more topics, the majority of codes represented a topic-intent combination. In order to capture the range of issues, scope, and complexity in numerous comments, several codes were frequently assigned to account for concrete or specific issues raised and larger themes participants may knowingly or unknowingly have implied (e.g., concerns regarding nanotechnology’s use in children’s products speaks to the concrete issue of children’s products in addition to the broader themes of risk and inter-generational differences).

Since each group followed the same question flow, corresponding transcripts were easily divided into six phases: (1) unprimed nanotechnology perceptions, (2) general nanotechnology perceptions, (3) nano-food product perceptions, (4) nano-food product willingness to use worksheet and consequent discussion, (5) nano-food product labeling discussions, and (6) final thoughts. Phase demarcations were determined based on the moderator’s explicit transition questions or statements, which clearly specified which topic was to be discussed by the group. Each phase elicited enough topic variety with respect to every other phase that separate coding lists were generated for each phase and applied across all groups. As a result, each phase contains a notable number of codes unique to that phase; however, many themes arose repeatedly across phases. Although all phases in each focus group were coded, analysis for this paper focuses on the emergence of skepticism and altruism as two coded themes unique to the literature and fairly ubiquitous across phases and groups. For analysis and discussion specifically about nano-food product willingness to use and labeling (phases 4 and 5), see Brown and Kuzma (2013).

Upon full transcript coding completion, the number of codes for each theme was tallied. Counts were assigned according to what constituted a complete expression of a theme or multi-participant exchange regarding a theme. Multiple analyses were conducted, depending on the phases and themes considered. To obtain a simple estimate of the frequency of given themes, codes were summed across all phases and groups. In the process of coding, statements embodying concepts not widely seen in the literature emerged: statements invoking skeptical sentiments and statements with an altruistic basis. Given the novelty of the presence of both ideas, more formalized coding definitions were formulated (see “Presence of altruism” and “Presence of skepticism” sections below) and all transcripts were re-coded to more accurately isolate comments invoking the themes and sub-themes of altruism and skepticism. Figure 1 shows the major themes and frequencies for the initial coding with skepticism appearing in the top five. Altruism cuts across several of the top themes shown in Fig. 1 including benefits, safety, nutrition, and generational differences. When re-coded, altruism appeared in 35 individual quotes in 17 exchanges.

Most prominent codes in full transcripts for all phases (counts). 1. Anticipation or impression of nanotechnology (n = 208) a. Negative (89) b. Positive (60) c. Mixed (54) d. Unsure (17) e. Neutral (6) 2. Risks (180) 3. Public awareness and understanding (159) 4. Reference to an existing product (155) 5. Skepticism (137) 6. Benefits (132) 7. Willingness to use products, mostly referencing products with nanomaterials (121) 8. Safety testing (69) 9. Nutrition (68) 10. Regulation (59) 11. Trust (50) 12. Generational differences (48) (any issue implicating adults vs. kids/younger people, e.g., differences in health-risk impacts, living styles, and interactions with technology)

Results and discussion

Presence of altruism

Statements or exchanges coded as having an altruistic basis were aggregated, re-coded with additional sub-themes, and sorted. Sub-themes (Table 1) pertained to the perceived or predicted benefits or risks of food nanotechnologies (specific applications or generally). Since altruism requires consideration of, concern for, or action toward someone or something outside of oneself (a target of sorts) we also assigned “target” classifications, in addition to sub-themes, to each statement invoking altruism. Out of all focus groups, a total of 17 exchanges invoked altruism with over 35 individual comments or statements of support or agreement. Notably, 16 out of the 17 exchanges dealt exclusively with some aspect of addressing starvation, food supply, or food quality, with the top three sub-themes emerging as “Food preservation, spoilage prevention, and storage” (six instances), “Food distribution and production” (five instances), and “Better/enhanced nutrition or crop yields” (four instances). Unsurprisingly, the majority of targets specified (13 exchanges) were those without enough food, in developing countries, or without access to grocery stores. Other targets included those with diseases like organ failure, unspecified for the “world,” and astronauts.

The environment was referenced several times in the context of its declining quality to provide food for the world however it was only mentioned once as a specific target of needing improvment in itself. The one statement that did not reference food production as a function of the environment specifically, and that directly presented the environment as a target of having problems, portrayed a more generic angle, stating “…there’s a very good possibility that this type of technology can relieve us of some of the problems we have in this world…the environmental problems and so forth that we’re dealing with.” The implied audience in that statement is the general world population, with the intended benefit of solving environmental problems. The fact that a larger group was referenced is evidence of expressing concern for other populations which is consistent with the definition of altruism.

Given that all except one comment dealt with current food issues, Table 1 provides a further breakdown of altruistic participant ideas evoked regarding food sufficiency, with example statements. Food preservation was frequently mentioned as a benefit. As a unique example of multiple audiences benefiting from better food preservation, one participant stated, “I see packaging as good I mean for people who need to have processed food long term, don’t have the advantage to go to the store like we do … [and] space technology, you know people traveling up there could eat real food, instead of something nasty, … you know if you can preserve food longer that is definitely an advantage.” In this case, preservation is assisting those with limited grocery access, in addition to those who have to spend time in space.

Regarding food distribution and production comments, while the example statement in the table highlights the transportability aspect, another angle was provided by this participant:

I think one of the most important things I would want to pass onto the researchers, is how [nanotechnology] will it impact the amount of available food and nutrition. I learned some things about changing the way this planet has enough dirt on it to create more food, turning a lot of this planet into desert, the deserts are just expanding, with population and where it is going to and less potable soil this could open up a whole new avenue of food production and that would have an impact on us in a positive way. And the other piece would be to find some way to work with various countries so that [these] profits [don’t] just go to the very rich, there should be a cost sharing, profiteering, huge benefit to both peoples …

The complexity of participant views is illustrated by this participant’s comment: the focus was on using technology to adjust food production methods, in order to expand general food production and improve nutrition, while preserving the ability of the environment to support food production and ensuring that the benefits go to not only the very rich. The latter half of this comment was also coded under the “Financial profit” sub-theme.

Risks and benefits were often considered together in the comments about helping other peoples or countries. The “Better/Enhanced nutrition, crop yields” sub-theme captures comments where nutritional improvements were highlighted, particularly for developing countries and the poor as the targets. However, the “Risk exposure” sub-theme invoked altruistic sentiments in worrying about the safety of nano-food products distributed to those without sufficient food access, despite the benefits. Along with the example in the table, the “Better/Enhanced nutrition, crop yield” sub-theme also had a “Risk Exposure” element: “…So once you get past the safety issues there is tremendous potential there.” The concern is that high-benefits do not alone justify food distribution, as long as risks remain unresolved.

Economic considerations for others were also expressed by the participants. Two comments coded as “Less costly food” both mentioned cheaper food as an important benefit for others and optimizing food access. “Financial profit” emphasized the need to ensure resulting profits were shared across populations.

Beyond the sub-themes in Table 1, four comments expressed the concept of products or technologies being rejected in developed nations but viewed as necessary for those in developing nations. It could be summarized as a “good enough for others but not for me” mindset, as is evident in this individual’s perspective (used as the example statement for “Less costly food”): “So engineering foods that last longer or are easier to produce, you know we don’t want to eat lettuce that is a year old, but there are people all over the world that are starving and need food sources that are viable and dependable and cheap and certainly there is quite a use for food that we may not choose but certainly it is desirable in other parts of the world.” While the person does deflect away from an individual choice by using “we” as a pronoun, it is definitively stated that what “is desirable” elsewhere may not be desirable here. Similar sentiments were expressed in three other cases of this theme. As it relates to altruism, this theme challenges whether such statements or individual positions are altruistic at all. Instead of simply describing how to assist other populations, “good enough for others but not for me” elicits undertones of social hierarchy, paternalism, and elitism. Accordingly, individual conceptions of altruism in these select instances addressing food sufficiency may be questioned.

Finally, while it was not a main driver in altruistic sentiments, overlap existed between altruism and skepticism in a few statements, albeit in dissimilar fashions. One participant presented an altruistic situation with a skeptical caveat: “And for world hunger we make enough food now we just don’t give it to everyone equally. We have the capacity to feed the whole world. We just don’t.” Although not specifically articulated, the individual is skeptical about the effectiveness of food distribution, in the context of attempting to feed the world with what is presently available. In contrast to this flavor of thematic overlap stands an exchange where a participant questions the presence of altruism:

1.5: Maybe they are trying to stay ahead in this could be a huge big positive in this whole thing, ahead of the population growth, this world isn’t getting any smaller, America is not shrinking, … so eventually maybe they’re thinking we don’t want to run out of space or we don’t want to run out of soil, we don’t want to run out of product, we don’t want to overload waste dumps and maybe this is one huge step in curbing all that.

1.4: It’s kind of hard to imagine our government being that altruistic.

An altruistic scenario is presented with which the skeptical individual does not disagree; however, this person questions whether those implicated (the government) can in fact be altruistic such that the scenario is attainable. Contrasting these two cases of thematic overlap reveals that skepticism can function from multiple angles for the same thematic basis.

Presence of skepticism

Statements or exchanges identified as containing some element of skepticism per our definition were aggregated, re-coded with sub-themes, and sorted. A total of 137 statements or exchanges were labeled as such, from which 36 unique sub-themes were created and applied. Since 22 of these sub-themes only appeared once or twice, we present and discuss only the sub-themes with a relatively higher number of counts. Table 2 presents the top 11 skepticism sub-themes, frequency counts, and example statements.

The skepticism sub-theme with the highest number of counts (36) was “Benefits of nanotechnology”. More specifically, this refers to a range of views that nanotechnology’s supposed benefits are not actually benefits, are mitigated by accompanied risks, or may be too good to be true, either as a whole or for particular applications. It often reflected the perspective that nanotechnology offers little to better food, as is best captured by this comment: “I don’t know how you can improve on Mother Nature.” Focusing less on a nature angle, this participant demonstrates the skeptical disposition to question what might be seen as a benefit: “… they can enhance food, flavor, color, whatever, but is that necessarily good? I don’t know.” Incorporating elements of other skepticism sub-themes, this individual ties benefits to public understanding and potential risks: “I’m just skeptical until I’ve been shown it’s a benefit or not a benefit to me. I don’t understand nanotechnology myself so I am skeptical of it, especially if it’s going to cost me more money for something I can’t prove to myself cause I may end up dead from it.”

Looking more broadly than nanotechnology, “Technology and product safety” occurred the second most frequently as a sub-theme (34 counts). While nanotechnology products were highly cited, this sub-theme captures concerns about any product or technology as a whole from a safety or risk standpoint. To ground nanotechnology perspectives, other technologies or products were periodically highlighted for comparison, such as genetically modified (GM) foods or Bisphenol A (BPA), as the second example quote shows. One participant incorporated a more historical risk viewpoint, stating “And it’s just like how long ago when there was lead in the paint, well nobody knew that was going to be harmful, or asbestos, nobody knew that, from the effects they find out that is not such a good thing.” More currently, the idea of technology adulterating food was an issue: “You don’t know if those packages are going to put something into the food itself, you don’t know that.” The skeptical stance regarding risk thus transcends a specific point in time or technology or product.

Following the top two skepticism sub-themes, the next nine had far fewer counts but are critical to explain, in order to present the gamut of skepticism’s influence. With 12 counts, “Public understanding of nanotechnology” was applied to statements or exchanges where individuals thought that they, themselves, or the public at large presently did not understand nanotechnology adequately in order to make decisions or form opinions, and/or were skeptical of the attainment of understanding. A sense of futility was evident for some, as expressed in this comment: “… It’s not like somebody is going to be out and learn everything there is to know about nanotechnology. It is just too out of the normal person’s comprehension.” On the other hand, others simply questioned the ease of an education process: “He read a nanotechnology description and it can mean a thousand different things so how do you communicate what that means to have nanotechnology processes so it is a challenge anyway.” A few participants tied understanding to decision making (see the first example quote in Table 2), demonstrating the potential impact of skepticism toward understanding on consumer purchasing behavior.

Similar to “Technology and product safety” is the sub-theme of “Safety testing and regulation”, which tallied 11 counts. While the former spoke to broader technology and product concerns, this sub-theme narrowed in on federal testing and regulation. Skepticism was apparent in views where testing and regulation were viewed as insufficient or following the presumption that companies avoid sufficient testing, in order to put a product on the market. This individual captured both points by stating, “Everything is inconclusive. All the stuff we have been talking about was inconclusive until they figured it out. If it takes 20 years to wait around, we aren’t going to wait around.” Accordingly, these views were not simply about companies, but rather, the market conditions in which they operate.

“Product label effectiveness” (11 counts) describes perspectives skeptical toward the usefulness of product labels, for multiple reasons. While nanotechnology product labels were mentioned, other products and labels in general were discussed to provide examples where labels are ineffective, such as warning labels on cigarettes. Skepticism about their ineffectual nature stemmed from concerns about correctly interpreting a label or that labels simply do not motivate behavioral change. Cross-coded with the “Public understanding” sub-theme, this exchange took the knowledge angle:

2.4: … but it’s putting that thing, “made with nanotechnology”, isn’t going to mean anything to anyone, unless they know…

2.9: what nanotechnology is.

In another focus group, this dialog highlights the more general view of how a label generally fails to affect consumer purchasing behavior:

3.8: Is like that now. Everybody reads labels on everything. I want to know everything that is in it.

3.1: But does that prevent you from buying everything that is in there.

3.8: Not all the time.

As with “Safety testing and regulation”, this sub-theme emphasized the role of previous technologies and product safety and labeling issues in the public’s mind.

Comments and exchanges coded as “Consumer choice and influence” (nine counts) dealt with how participants viewed consumers’ ability to make product and technology choices, and the extent to which their voices influenced product and technology cycles. Skeptical positions asserted that consumer choice and influence is limited, as illustrated by examples in Table 2. One participant stated with regard to labeling products:

5.7: I don’t think [nano-food product labeling] is going to be our concern anyways. I think it is going to be up to the FDA… I don’t think it will be up to consumers to have a decision on whether they put it on packages or not.

On the contrary another more simply stated:

1.8: You’re getting, either willingly or unwillingly, you’re pulled into it. You don’t have a choice.

Speaking to technological changes in food, one participant shared skepticism, though without cynicism toward all of nanotechnology:

1.6: … some of these nano materials could manifest themselves into different parts of the body that regular food cannot and some of the things when you introduce it might cause something else. I don’t think enough research has been done that I would be comfortable with it. Now obviously I can’t stop it, you know I’ll have to eat some of it. But I would prefer more to more eat natural foods, I would agree with this gentleman here that I don’t think there is anything wrong with this technology per say, if it’s applied to machines or iPods or things like that even though I don’t have any of those. I draw the line with food, at least at this time and I’m driving a 1967.

Not a single participant defended the idea that consumers will have a sufficient voice in product and technology development. Taken further, one person attached future risk with inevitability: “… the pesticides, all the stuff you get, 20 years or later, if you find out it is healthy or not, I think, we are stuck with it. It is inevitable, and I you hope my kids still don’t get sick from it when the time comes.”

Parallel to discussions about consumer behavior, the “Willingness to use nano-products” sub-theme (nine counts) covers perspectives where participants were skeptical about consumers choosing to use or purchase nano-products. Generally, a reason for the skepticism was provided; however, an overarching sense of avoidance motivated this person when talking about variations in willingness to use nanotechnology for food additives, packaging, or processing: “I don’t know why processing I’m willing to use. None of the other stuff I was willing to, the others I was neither willing [nor] unwilling. So, I’m skeptical of everything.” As captured in the Table 2 examples, the main reasons for unwillingness to use nano-products were limited knowledge about the product and merely the fact that the product is new. Such a view was echoed by this speaker: “… if I go to the grocery store and it says nano I am going to go home and I am going to think about it and research it. I am a huge researcher; I am just huge into it. I would check into everything and know everything about it before I’m willing to try it.”

Eight comments or exchanges were tallied for “Producers’ concern for the public” sub-theme. This addresses the perception of businesses and companies, with respect to their actions toward the public. The skeptical aspect sets a baseline of mistrust toward companies. The following exchange best illustrates the perspective:

1.7: Well I think it might be a mindset too. Are they really out to hurt me? Or are they really out to give me more nutrition?

1.1: I agree, I would think more along the lines that they are trying to do something good.

1.1: They’re not trying to…

1.8: Do us all in.

1.1: Well, or, take over our minds with some kind of control.

It is important to note that there was not a consensus against producers; rather, a moderate level of skepticism was applied to question producer motives. As exemplified by 1.1 above, some optimism certainly exists, though it did not outweigh the skeptical conversation tones.

Related to producer concern is how financial aspects of product development factor into producer decision making. “Financial motivations and influence” (seven counts) highlighted these perspectives. As expected, given skepticism toward producer concerns toward the public, participants were skeptical of the reasons for product development, citing economics and money as a negative influence. Entwining both the concern and financial issues, this speaker stated, “…because I think everyone knows that we are the most obese country in the world and we are the most spoiled country in the world, so it would make sense that we’re kinda pioneering something like this today. … maybe it’s just a money thing, they’re going to make some money off doing all this stuff but, I don’t know, but maybe they really do have general concern for the public and that we’re kinda out of shape and not good and not healthy.” Here, the individual leaves judgment open as to whether producers are acting out of a desire to solve a health matter or simply money.

Strong negativity and skepticism pervaded opinions about the “natural” nature of food technology, as seen in the seven counts for “Naturalness of nano, GMOs, and processing”. The simplest and most direct expression of skepticism was provided by this participant: “Well nanotechnology equals processed food, then that already has a negative connotation in my opinion.” In this person’s mind, nanotechnology was automatically linked with processing, which already carried a negative valence. Similarly, nanotechnology is termed as a verb in the Table 2 example statement, “nanotechnologized”, signifying implied food manipulation. Looking at a less decided opinion, this speaker agnostically describes genetically altered food, in light of processed food that appeared to not spoil over time:

5.7: She kept it on a plate for a year, no mold, no spoilage no bugs, it just turned hard plastic like that fake plastic fruit they have. Now that has to be harmful to you. And that’s my main concern about genetically altering foods that are supposed to be natural. Like I said before, what is natural? I mean when we get it, we can go to a fresh market next door, they tell us it is organic, but what do we know?

Lastly, “Producer transparency and communication” (seven counts) incorporates skeptical perceptions about the willingness and ability of companies to be transparent and communicate to the public. Such mediums for transparency and communication included general communication (e.g., advertisements) and product labels. Considering the marketing aspect, this individual shared the following: “It is not going to say this has got nano robots or nano enhanced flavors, it is going to be marketed in a creative packaging. … I just hope that the industry would try to do an appropriate job and say, ‘hey this is in here or it is made with this kind of processing plant’ … if you are forthcoming then you don’t have to tell as many lies later.” This sentiment matches those from “Producers’ concern for the public” and “Financial motivations and influence” in that skepticism exists regarding the motivations factoring into producer decisions, which, in this sub-theme, deal with communication and transparency. A lengthy example highlighting doubts about clear labeling efforts is shown in Table 2.

Conclusions

This study uncovers through qualitative methods that skepticism and altruism are two as yet unrecognized factors influencing perceptions of nanotechnology in food. It also reveals that these two new factors may be significantly insightful for bridging the gap between how and why perceptions are formed. In thinking logically about skepticism and altruism, they might provide a bridge between theories based on culture (cultural cognition) and those based on the features of the risks themselves (psychometric). We present these ideas as exploratory and because they strike us as logically informative and thought-provoking.

It should be noted, however, that focus group methods are not intended to be representative of populations, and our groups, although approximates, did not precisely match the population demographics. For example, more males were present in the focus groups than females. If anything, this composition may understate skepticism toward technologies if it relates to risk, as many studies have shown the “white male effect” in which white males rate societal risks as lower in magnitude than women and minorities (Finucane et al. 2000; Kahan et al. 2007). The generally older ages of our participants (59 % over age 50 vs. about 35 % in the U.S. population) and higher degrees of education (50 % with college education vs. about 40 % in the U.S. population) (U.S. Census Bureau 2015) may have affected our results. As such, we acknowledge that these ideas are not yet generalizable and that future studies will be needed to confirm or refute the significance of these findings across cultural and demographic groups and technological contexts.

In the interim, however, we suggest that both of these factors can be placed into a draft model for risk perception. In our review of the literature on risk perception theories, we are struck by how skepticism in particular and altruism to a lesser extent have not been specifically accounted for in studies on the psychometric paradigm or cultural cognition theory. Additionally, while our study was not designed to test either theory, our study findings do provide considerable food-for-thought that skepticism and altruism may provide bridges between these two theories (Fig. 2). The precise nature of that bridge needs further exploration, but we offer for consideration some logical possibilities based on our study results.

Draft model for placing skepticism and altruism in risk perception theory. The solid lines indicate influences from multiple studies in the literature, whereas the dashed lines are proposed relationships derived from this study. Explanations of the connections between cultural cognition, skepticism or altruism, and psychometric factors are proposed in the text boxes. The proposed connection between altruism and the psychometric paradigm is discussed in the text and Slovic and Västfjäll (2010)

One interpretation grounded in cultural cognition suggests that perhaps altruism and skepticism are heuristic tools by which individuals modulate their beliefs about risks to match their worldviews. Under this interpretation, it follows that cultural worldview would influence what an individual is skeptical or altruistically hopeful about although levels of skepticism or altruism could be the same among cultural groups. For example, individualists under cultural cognition theory may be more skeptical of government systems, whereas communitarians and egalitarians might be more skeptical of industrial-techno systems or those in positions of financial or resource power. With regard to altruism, it also makes sense that individualistic groups would rely less on government and more on individuals to act on concern for others by promoting and directing benefits of technologies, whereas communal groups might expect government to provide these services.

For example, to demonstrate the role of skepticism in cultural cognition types, hierarchical individualists, whose worldview is often described as “fatalistic,” may express skepticism such that they are powerless from understanding or controlling risks, as seen in statements like “[nanotechnology] is just too out of the normal person’s comprehension.” Egalitarian–individualist types may express skepticism about the ability of industry or government to control risks in support of the view that it should be left to the individual (e.g., “I don’t trust it unless I can prove its safe myself.”). To demonstrate the role of altruism, hierarchical-communitarian types may adopt an altruistic view like, “maybe [the technology developers] are…thinking…we don’t want to run out of soil, we don’t want to overload waste dumps, and maybe this is one huge step in curbing that,” indicative of support for stratified authority for the collective good. Finally, to demonstrate how skepticism and altruism may be simultaneously used, an egalitarian–communitarian type may espouse a view that supports collectivism or that deploys social pressure like, “[W]e make enough food now we just don’t give it to everyone equally. We have the capacity to feed the whole world. We just don’t.”

It is also possible that levels of altruism and skepticism really do change depending on cultural worldview, although that will also need to be tested. One starting hypothesis would be that the hierarchical-individualist group is less altruistic in its perception of food nanotechnologies given its reliance on the individual, and the egalitarian–communitarian group is more altruistic given its faith in communities to equalize distribution of resources. Another example is that egalitarian–communitarians may be more skeptical of systems in general as they pay more attention to previous impacts on the disenfranchised and powerless.

Alternatively, levels of skepticism and altruism may be primarily related to the features of the risks themselves. Previous experiences with food technologies and risk were extensively mentioned in our focus groups (e.g., BPA in water bottles, GM foods, food additives, pesticides in food), and these experiences could affect levels of skepticism regardless of cultural group. In the context of altruism, a few statements related to the risks from nano-food are insignificant compared to the overall benefit that could be experienced by people who need more food (e.g., “[nano-food is] food that we may not choose but certainly it is desirable in other parts of the world”). Statements expressing skepticism can indicate people having higher perceptions of risk because nano-foods are not controllable, (“I’m not going to be able to avoid eating it.”), or people having higher perceptions of risk because the harm from nano-food is uncertain or ambiguous, (“No one knows what it’s going to do to you.”).

A third possible interpretation is that skepticism and altruism function as some variety of the affect heuristic. The “warm glow” feeling of altruism in spreading benefits of nano-food to the poor may result in judging risks lower and benefits higher, while the scared and confused feeling of skepticism may trigger the opposite reaction to nano-foods.

From a theoretical standpoint, we summarize the above possible interpretations in Fig. 2 as a starting point for future studies and investigations to explore and better understand these relationships. In this draft model, cultural cognition is seen primarily as the why of risk perception and psychometric factors are the what, or the features of the risks themselves. Skepticism and altruism bridge these and direct the worldviews toward particular risk issues and what to do about them. Thus, skepticism and altruism could lie between the psychometric factors that vary with very specific food risks and the more constant cultural-world views that people possess. Trust is also to be viewed as a bridging factor in this model, although as discussed in the introduction, it has been considered in the literature as both a part of belief-based risk theories and as a psychometric factor. Regardless, it is distinct from skepticism and viewed as not closely related to altruism. For trust, something or someone must be trusted or not, whereas skepticism most often evoked questions about something occurring or not as a result of several organizations, people, and events in socio-technological systems.