Abstract

We investigated the relationship between personality and quality of life (QoL) considering emotion regulation and self-efficacy beliefs as mediating factors. A total of 409 participants from the French-speaking regions of Switzerland and from France completed questionnaires on personality, emotion regulation, self-efficacy beliefs, and QoL. Our findings revealed that specific personality traits have significant direct and indirect effects on QoL, mediated by emotion regulation and self-efficacy. Particularly, neuroticism was strongly and negatively related to emotion regulation and QoL, but not significantly linked to self-efficacy, whereas extraversion and conscientiousness were positively associated with all variables. This is the first study to demonstrate that both emotion regulation and self-efficacy are important mechanisms that link specific personality traits to QoL, suggesting that they channel and modulate the personality effects. However, more work is needed to understand these relationships in more detail (e.g., how the personality traits concurrently influence each other as well as emotion regulation and self-efficacy).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality of life

The World Health Organization defines Quality of Life (QoL) as individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and their relationship to salient features of their environment (Skevington et al. 2004). Although several authors have studied how different personality profiles and self-regulating factors such as emotions or self-efficacy beliefs influence QoL, little is known about how these characteristics may work together simultaneously. For instance, some personality psychologists have explored the personalities of happy and unhappy people and how adaptation and varying standards influence their QoL (Lucas and Diener 2015). They showed that personality factors influence QoL by associated tendencies to interpret objective conditions (such as behavior and environment) that might lead to stability of self-reported life satisfaction (such as psychological well-being and perceived QoL; Keating and Gaudet 2012). For example, being faced with a serious illness such as cardiovascular disease is likely to have implication on his or her objective quality of life, for instance, due to constraining the individual’s autonomy. However, people with the same illness may differ in terms of life satisfaction, independent from their objective health and life conditions, due to the interpretative tendencies related to, for example, their personality. Thus, both objective and subjective components are assumed to explain unique proportions of variance in people’s QoL (Wrosch and Scheier 2003).

Personality and quality of life

Among the personality dimensions, neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness are particularly important and are most frequently studied in relation to QoL (Lucas et al. 2000; Wismeijer and van Assen 2008). These three personality traits are the best predictors of mental health, life satisfaction, and positive affects (Finch et al. 2012). Specifically, neuroticism and extraversion predict long-term (over 10 years) the negative and positive affects (Costa and McCrae 1980) and, together, these two components of emotional well-being influenced overall the QoL (Diener at al. 2003; Kokkonen and Pulkkinen 2001; Lucas and Fujita 2000). Neuroticism is linked to the frequency and duration of negative affects and therefore to a lower QoL. This personality dimension can be considered as a system of perception of the “threat”, real or symbolic, and of reactivity to this threat. A high level of neuroticism predisposes people to more negative experience and distress (Watson and Clark 1984). People with higher neuroticism experience more stress, and are more responsive to negative aspects of situations than those emotionally stable (e.g., Costa and McCrae 1980; Charles et al. 2001). These people also experience fewer positive affects and are more prone to diseases such as depression and generalized anxiety. Extravert people, instead, will feel more positive affect with high activation (Lucas and Fujita 2000; Yik et al. 2011). Extraverts and introverts would spend as much time in social interactions, but individuals with a high level of extraversion experience more pleasure (Lucas and Baird 2004). Extravert people implement more active and dynamic specific processes and mechanisms, which was associated with increase in QoL (Wilt et al. 2012). At the level of activation, extraverts seek stimulation and more exciting activities, whereas introverted individuals may be less motivated to increase their happiness in situations requiring an increase in motivational commitment to a task requiring effort (Tamir 2009). Some studies also have shown that high conscientiousness explains significant amounts of variance in people’s QoL (e.g., Pocnet et al. 2016b). Conscientious individuals seem to overcome unexpected obstacles more easily than individuals who are less dedicated to achieving important life tasks. These people are oriented towards life situations that are beneficial to QoL, notably by setting higher goals and a higher level of motivation. They encounter fewer stressors because they put in place more preventive and organizational efforts to avoid them (e.g., DeNeve and Cooper 1998). Conscientious individuals are better able to anticipate and prepare for future consequences of potential adversities, more organized, and self-disciplined (Pocnet et al. 2016a). They seem also be more successful in establishing objective indicators of QoL (e.g., having a successful career, good health) (Barrick et al. 2001; Roberts et al. 2005) and therefore experience high levels of subjective well-being (Duckworth et al. 2012; Wrosch et al. 2007).

Emotion regulation and its relationships with personality and QoL

Often, individuals’ behaviors, cognitions, and feelings are influenced by basic regulatory tendencies that are associated with the personality of the person. These self-regulating tendencies are related to processes of emotion regulation (DeYoung et al. 2010). Emotion regulation has been defined as a process of initiating, avoiding, inhibiting, maintaining, or modulating the occurrence, form, intensity, or duration of affective states, emotion-related physiological or attentional processes, and/or behavioral concomitants of emotion (Reicherts et al. 2012). Emotion regulation has been found to be of high importance when it comes to adapting to various situations in order to meet the expectations of social and cultural environments (Eisenberg and Spinrad 2004).

Considering the relationship between personality and emotion regulation, studies indicate that individuals high in neuroticism, which encompasses impulsivity, are often low in self-control and impulse regulation and show a tendency to act without thought or planning (Hoyle 2006; Wismeijer and van Assen 2008). Neurotic people also exhibit high behavioral inhibition and negative self-evaluation, which can lead to underestimating progress in goal pursuit (Little and Chambers 2004). As such, poor self-regulation may stem from either under- or overcontrol (Hoyle and Gallagher 2015). Moreover, neuroticism is associated with a style of self-reflection that is ruminative and ego involved that could negatively influence the individual’s QoL (Norem and Chang 2002; Field et al. 2010).

Extraversion, besides indicating the tendency of being open towards others and appreciating social contact, is also characterized by experiencing positive emotions that include energy and optimism (Costa and McCrae 1992; Schaefer et al. 2004). These emotional resources are required to initiate and persist in coping efforts, which should facilitate the better use of coping strategies such as problem solving and seeking support (Vollrath 2001). For example, an extroverted person may become less quickly frusterated and may remain focused during problem solving because may rely more easily on emotional social support to regulate emotions (Kokkonen and Pulkkinen 2001). Suls and Martin (2005) found that extraversion was associated with low stress-reactivity and positive appraisals of available coping resources. Moreover, extraversion is related to subjective well-being, which seems to be associated with the fact that extravert people are more likely to selectively attend to positive information and dwell on positive events, all of which are strategies that promote and increase in positive affect, and therefore their QoL (Tamir 2009).

Conscientiousness concerns the ways in which people manage their behavior and cognitions. Its facets—competence, orderliness, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation—reflect different behavioral tendencies that characterize successful self-regulation (Roberts et al. 2005; McCrae and Löckenhoff 2010) and predict the use of effective strategies involving behavioral engagement such as problem solving as well as cognitive restructuring that could influence the individual’s QoL (Augustine et al. 2010). Some authors explained this link between conscientiousness and effective strategies by the fact that high levels of conscientiousness may be rooted in attentional systems that influence the ability to focus on boring or unpleasant tasks or to disengage from high negative intensity stimuli (Derryberry et al. 2003). Given that conscientious individuals should be able to resist the impulse to give up or vent emotions inappropriately (Vollrath 2001), conscientiousness should predict lower levels of disengagement and negative emotion-focused coping.

Self-efficacy beliefs and their relationships with personality and QoL

Self-efficacy represents an important resource as it reflects the unique capability of humans to learn from experience to handle challenging life situations. Self-efficacy is defined as a person’s belief of being able to successfully reach a desired outcome (Bandura 1993). Self-efficacy beliefs have an impact on the feeling of accomplishment, leading to a virtuous circle: if a person experiences a success, this will contribute to building up self-efficacy, enhance his/her motivation and capabilities and broaden his/her interest (Bandura 1997). In this context, specific personality traits may play an important role. High self-efficacy has been found to be more likely for individuals with higher conscientiousness and extraversion, and lower neuroticism (Hoyle and Gallagher 2015). A few empirical studies have investigated how personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs work in concert in order to promote QoL (Maddux and Volkmann 2010). For example, extraverts may have advantages in verbal information processing that support their sociability. Good language skills, speed of response as well as resistance to distraction are supported by self-efficacy, enhancing their adaptive value that might lead to a feeling of well-being (Matthews and Gilliand 1999). However, several studies on stress show that neuroticism leads to an overestimation of threats and an underestimation of personal agency, to ineffective forms of emotion-focused coping such as self-criticism and maladaptive meta-cognition which strengthen negative self-beliefs, and to perseverative and unproductive worry, resulting in feelings of dissatisfaction (Matthews and Zeidner 2004). At the same time, conscientiousness defined as the disposition to be purposeful, determined, organized, and controlled (Costa and McCrae 1992) may be especially interesting in this context because individuals who are higher in conscientiousness have been found to hold also higher self-efficacy beliefs for a given behavior. For example, Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham (2003) reported in their study that indidivudals with high conscientiousness were better able to build up self-efficacy by task effort and performance, persistence, resilience in the face of failure, effective problem solving, and efficiency of time use. Complementing these findings, Kelly and Johnson (2005) found that given their higher levels of self-efficacy, conscientious people were more likely to successfully engage in acts that were important to them, arguing that self-efficacy beliefs were directly responsible for the level of QoL that these people experienced.

Purpose of this study

The main focus of our study was to examine more closely the impact of personality on QoL considering emotion regulation and self-efficacy beliefs as mediating factors. Given prior findings, we expected that specific personality would be linked to emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL. Particularly, conscientiousness and extraversion were assumed to be positively, whereas neuroticism to be negatively linked to emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL.

Furthermore, emotion regulation was expected to mediate the effect of three personality traits on self-efficacy.

Also, self-efficacy was expected to mediate the effect of emotion regulation as well as the three personality traits on QoL, but the individual effects are expected to be differential. Specifically, neuroticism was assumed to be negatively linked to emotion regulation and to self-efficacy beliefs, while extraversion and conscientiousness were expected to be positively linked to the same variables. Additionally, emotion regulation was expected to be positively associated with self-efficacy beliefs.

Methods

Characteristics of the sample and procedure

A total of 409 individuals [including 211 women (51.6%) and 198 men (48.4%), ages ranging from 20 to 65 years, M age = 39.72, SD age = 12.87] representing a community-based sample of the French-speaking regions of Switzerland and of France (Aix en Provence region) participated in this study. Of the 409 participants, 254 (62.1%) were recruited in Switzerland and 155 (37.9%) were recruited in France. The subjects were recruited in the community by psychology students as part of a practical assignment. The participants were professionally active and employed in various institutions. They completed the paper–pencil questionnaires on personality, emotion regulation, self-efficacy beliefs, and QoL. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. As there were no substantial differences between the two samples, we combined the Swiss and French participants for the analysis.

Measures

Personality

We used the French version of the NEO-FFI-R, a short version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (Costa and McCrae 1992), measuring the five main personality dimensions of the five-factor model (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness). The participants were asked to respond to 60 items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Internal consistency coefficients of the French version of the NEO-FFI-R ranged from 0.70 to 0.82 for the five scales (Mdn = 0.76) (Aluja et al. 2005). In this study, we used only three domains: neuroticism (example item: When I am under the pressure of very difficult situations, I sometimes feel like I’m going to collapse) extraversion (example item: I like to have many people around me), and conscientiousness (example item: I have a well-defined set of goals and I work to achieve them in an orderly way). Internal consistency coefficients in this study were high (neuroticism: \(\alpha\) = 0.81, extraversion: \(\alpha\) = 0.76, and conscientiousness: \(\alpha\) = 0.82).

Self-efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES; Jerusalem and Schwarzer 1992) translated into French (Dumont et al. 2000) consists of 10 items, which are answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (completely true). An example item is: I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough. This scale is designed to assess self-beliefs related to solving a variety of challenging demands of life. In contrast to other scales, the GSES explicitly refers to personal agency, i.e. the belief that one’s actions are responsible for successful outcomes. In our study, internal consistency was high (\(\alpha\) = 0.84).

Emotion regulation

We used a subscale from the Dimensions of Emotional Openness questionnaire (DOE-20) to assess emotion regulation (Reicherts 2007). In this measure, the regulation of emotion dimension represents one’s capacity to regulate and monitor emotions. The four items of this subscale were: At moments I’m overwhelmed by strong emotions; I am able to alleviate or postpone the effects of a strong emotion; My feelings can sometimes cause me to break down; I manage to calm my feelings even in difficult situations. Answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Prior work has shown satisfactory reliability of the 4-item sub-scale (Reicherts et al. 2012). In our study the internal consistency for the emotion regulation dimension was satisfactory (\(\alpha\) = 0.67).

Quality of life

We used a 12-item version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL-12) to assess QoL, which was recently validated in French using the participants in the present study (Dupuis et al. 2016). This self-reported questionnaire consists of 12 items (3 per factor) related to 4 dimensions of the WHO Quality of Life Inventory WHOQOL-100, namely: physical health (\(\alpha\) = 0.73), psychological health (\(\alpha\) = 0.64), social relationships (\(\alpha\) = 0.61), and environment (\(\alpha\) = 0.69). The four-factor converged into a higher-order factor of overall QoL, which had a high internal consistency (\(\alpha\) = 0.84). Example items for each dimension are: Do you have enough energy for everyday life? is representative of the physical dimension; How much do you enjoy life? corresponds to the psychological dimension; How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? belongs to the subscale covering social relations, and How healthy is your physical environment? corresponds to the QoL dimension covering environment. Items are answered using a 5-point Likert scale, allowing the evaluation of own feeling (ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely), according to the questions. Analyses of internal consistency, item-total correlations, criterion validity, construct validity, and measurement invariance through confirmatory factor analysis, indicate that the overall WHOQOL-12 has good psychometric properties (Dupuis et al. 2016).

Statistical analysis

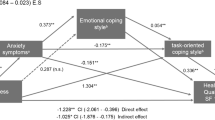

After evaluating descriptive findings for demographic and psychological characteristics, we computed the Pearson correlations between key study variables to examine zero-order relationships. We then tested three structural equation models (SEM) in order to determine the specific effects of the three personality dimensions (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness, respectively) on QoL considering emotion regulation and self-efficacy as mediators (Fig. 1). In those models, we also tested whether the effect of emotional regulation on QoL was mediated by self-efficacy. Given that including all personality traits would have resulted in a too complex model, we chose to test the effect of each personality trait separately. Thus, each model specified both direct and indirect effects of one personality trait (neuroticism, extraversion, or conscientiousness, respectively) on emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL.

QoL was measured by a general latent variable composed of the four dimensions of the WHOQOL-12. Furthermore, the determination coefficient, which indicates the amount of the variance in QoL explained by specific variables, was computed. To evaluate the model fit, the following indices were calculated using the Maximum Likelihood Robust estimation method (MLR): the \({{\chi }^{2}}\)/df ratio, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis non-normed index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The \({{\chi }^{2}}\)/df ratio is considered acceptable when lower than 5, and indicates an excellent fit when it is below 3 (Kline 2011). Hu and Bentler (1999) suggested that models presenting CFI or TLI indices greater than 0.90 are generally considered to be acceptable. A RMSEA below 0.07 indicates a good model fit and is acceptable as long as the confidence interval of its estimate is lower than 0.08 (MacCallum et al. 1996). The SRMR is acceptable when it is lower than 0.08 (Kline 2011). All analyses were performed with R; the structural equation model was tested using the R package ‘Lavaan’ (Rosseel 2012).

Results

Descriptive findings and zero-order correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all central variables are presented in Table 1. As the main variable of interest, QoL had a mean score of 48.30 ± 5.78 indicating a high overall level (range 12–60). Gender, age, and income were not significantly correlated with QoL. However, nationality was negatively linked to all components of QoL. The correlations between QoL and psychological variables were moderate. Specifically, all QoL domains correlated positively with extraversion, conscientiousness, and self-efficacy and negatively with neuroticism. Moreover, it appears that emotion regulation was linked to all QoL domains, except social relationships. In addition, neuroticism was negatively associated with emotion regulation and self-efficacy, while the links between the two others personality dimensions and emotion regulations as well as self-efficacy were significantly positive.

Neuroticism and its links to emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL

The Structural Equation Model (SEM) testing the relations between neuroticism, emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL explained 32.8% of variance in QoL. The model fit was good as indicated by a RMSEA of 0.059, 95% IC = [0.049, 0.070], a SRMR of 0.055, a CFI of 0.942, and a TLI of 0.927. The \({{\chi }^{2}}\)/df ratio was 2.43. Our model confirmed both direct and indirect significant effects of the variables (Table 2): Neuroticism showed direct effects, which standardized values ranging from −0.80 to 0.46, and indirect effects ranging from −0.37 to −0.04 on the other variables. As illustrated in Fig. 2 and indicated in Table 2, a large direct negative effect of neuroticism on emotion regulation was found (\(\beta\) = −0.80, p < 0.001), indicating that more neurotic individuals demonstrated less emotion regulation, but in contrast, the effect of emotion regulation on self-efficacy was positive but only approached significance (\(\beta\) = 0.46, p = 0.052), suggesting that individuals with better emotion regulation scored higher in self-efficacy. Consequently, the indirect effect of neuroticism on QoL, mediated by self-efficacy, was negative but not significant due to large standard errors of estimate (\(\beta\) = −0.37, p = 0.075). Neuroticism had a small negative direct effect on self-efficacy that was not significant (\(\beta\) = −0.11, p = 0.614). Self-efficacy in turn, had a positive and significant effect on QoL (\(\beta\) = 0.32, p < 0.001), resulting in a negligible negative indirect effect (\(\beta\) = −0.04, p = 0.618). Given both positive and strong effect of self-efficacy on QoL and a moderate positive effect of emotion regulation on self-efficacy, the indirect effect of emotion regulation on QoL via self-efficacy was positive, but only with an approached significance (\(\beta\) = 0.15, p = 0.065). Nevertheless, the total effect of neuroticism on QoL was negative and very significant (\(\beta\) = −0.50, p < 0.001).

Extraversion and its links to emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL

In the SEM including extraversion, emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL, a good fit was obtained with a RMSEA of 0.052, 95% IC = [0.041, 0.063], and a SRMR of 0.045. The \({{\chi }^{2}}\)/df ratio was 2.09, the CFI was 0.946, and TLI was 0.932. The model explained a total of 30.3% of variance in QoL. Regarding the prediction of QoL, all direct effects assumed by the model were significant, although smaller for extraversion and emotional regulation relationship (\(\beta\) = 0.20, p = 0.027) (Table 3). In addition, a significant mediation of the effect of extraversion and emotion regulation via self-efficacy on QoL was found (\(\beta\) = 0.12, p < 0.001, and \(\beta\) = 0.21, p < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, small but significant indirect effects of extraversion on self-efficacy via emotion regulation were measured (\(\beta\) = 0.11, p = 0.020). The indirect effect of extraversion on QoL mediated by emotion regulation and by self-efficacy was also small, although still significant (\(\beta\) = 0.04, p = 0.025). Consequently, the direct effect (\(\beta\) = 0.26, p < 0.001), the total indirect (\(\beta\) = 0.16, p < 0.001), and the total effect of extraversion on quality of life (\(\beta\) = 0.42, p < 0.001) were very significant.

Conscientiousness and its links to emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL

The third structural equation model testing the relations between conscientiousness, emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL explained 34.8% of variance in QoL. The model resulted in an RMSEA of 0.058, 95% IC = [0.047, 0.069], and a SRMR of 0.052. The \({{\chi }^{2}}\)/df ratio was 2.37, the CFI was 0.940 and the TLI was 0.924. All indices confirmed that the model fitted the data well. This last model resulted in both direct and indirect significant effects (Table 4). Conscientiousness showed direct effects ranging from 0.24 to 0.35 and a total indirect effect of 0.15 on QoL. As a consequence, the total effect of conscientiousness on QoL was positive and strongly (\(\beta\) = 0.51, p < 0.001). As depicted in Fig. 2, emotion regulation had a quite large positive effect on both self-efficacy (\(\beta\) = 0.53, p < 0.001) and QoL (\(\beta\) = 0.34, p < 0.001). These direct effects resulted in a moderate but significant positive indirect effect on QoL (\(\beta\) = 0.18, p = 0.002).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between personality (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness) and QoL, taking into account emotion regulation and self-efficacy beliefs as mediating factors. More specifically, we tested three models using each personality dimension together with emotion regulation and self-efficacy, representing factors mediating on QoL. Moreover, we tested whether self-efficacy mediated the impact of emotion regulation and personality on QoL, whereas emotion regulation mediated the effect of personality on self-efficacy.

Regarding personality, we found that high neuroticism was associated with poor QoL, while high extraversion and conscientiousness were positively related to QoL. One underlying reason for the negative association between neuroticism and QoL may be the fact that more neurotic individuals demonstrated less emotion regulation and low self-efficacy, which may lead them to the conclusion that life problems are beyond their control and therefore not manageable, and that their efforts could not solve them. In line with prior studies (Matthews and Zeidner 2004; Hoyle and Gallagher 2015; Pocnet et al. 2016b), our findings suggest that neurotic individuals may underestimate their personal skills or resources, as represented by poor self-efficacy, and that emotion regulation seems to channel effect of this on QoL. Conversely, the positive link between emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and QoL indicated that emotionally stable individuals with high self-efficacy and adaptive emotion regulation may experience higher QoL. Therefore, although neuroticism negatively influenced the QoL, the process of emotional regulation and self-efficacy beliefs seems to temper its effect. Our findings support the role of emotion regulation and self-efficacy as possible regulatory mechanisms which was also found in earlier studies (Norem and Chang 2002; Judge et al. 2007), but for the first time, self-efficacy and emotion regulation were examined concurrently showing their effective interplay.

Moreover, QoL was significantly and positively influenced by extraversion, directly or via self-efficacy beliefs and emotion regulation as mediating factors. Self-efficacy seems to channel the effect of extraversion on QoL, maybe by reinforcing the tendency to experiencing positive emotions that enhance self-assurance and self-esteem. Thus, jovial individuals who enjoy the company of others may experience themselves as particularly self-efficacious, as situations with others may allow recognition of one’s capacities and skills, which in turn may result in individuals feeling more positive about their life and functioning (e.g., Jopp and Rott 2006). These results are similar to previous findings about the influence of extraversion on QoL (Matthews and Gilliand 1999; Diener et al. 2003; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005; Lucas and Diener 2015), but to our knowledge, the present study is the first that has empirically confirmed the role of self-efficacy as a mediating factor between positive emotion regulation and high QoL. These positive connections between emotion regulation and self-efficacy is in line with theoretical assumptions (Maddux and Volkmann 2010) and could lead to a tendency to look on the bright side of life. However, contrary to our expectations, extraversion influenced QoL via emotional regulation and self-efficacy only moderately. As emotion regulation involves the ability to manage feelings in difficult situations, which includes the management of interpersonal relationships and the affectivity, we had expected at a more significant effect. One possible explanation is that extravert people are less likely to be affected by failure at a personal level, thus, it could be that individuals high on extraversion have a reduced need for emotion regulation. Also, as extravert individuals often talk to someone about their feelings and receive sympathy and understanding, they have been found to use this as a strategy to receive emotion-focused support and to activate their energy and social resources (Tsai et al. 2007). Talking to a supportive, validating person about one’s thoughts and emotions related to an acute stressor facilitates adjustment by reducing the frequency of distressing, intrusive thoughts (Lepore et al. 2000), which may make “internal” emotion regulation less needed.

Instead, our findings clearly indicate that neuroticism and conscientiousness dimensions of personality are strongly associated with emotion regulation. Specifically, neurotic people are likely to blame others and to underestimate goals progress, while conscientious individuals, who have, as its negative expression, a tendency towards perfectionism or compulsive persistence tend to blame themselves when they fail in the pursuing of their goals. Some authors suggest that the facet of impulsivity belongs within this domain because it reflects a failure to be conscientious, disciplined, or deliberate (McCrae and Löckenhoff 2010). So, both consciousness and neuroticism personality traits are related to emotions that need to be regulated.

Moreover, conscientiousness had significant direct as well as indirect effects on QoL, indicating that this personality dimension is an important factor in the context of QoL. Conscientiousness was strongly and positively related to self-efficacy, suggesting that being conscientious is likely to come with feeling strong about one’s competence. Moreover, self-efficacy beliefs mediated the relationship between conscientiousness and QoL: Trusting in one’s ability to complete tasks and reach goals seems to be one of the mechanisms linking conscientiousness to QoL, confirming findings by Judge et al. (2007). Our results suggest that conscientious people might have a higher QoL because they are organized, hard-working, and efficient, which likely contributes to their ability to achieve personal goals, as also suggested by other studies (Kelly and Johnson 2005; Maddux and Volkmann 2010; Pocnet et al. 2016b). In addition, people with high conscientiousness tend to practice healthy behaviors (e.g., engaging in physical exercise) and avoid risky health behaviors (e.g., smoking), behaviors that are part of the health dimension of QoL (e.g., Pocnet et al. 2016a). Conscientiousness was also positive linked to emotion regulation, suggesting that this personality domain seems to be a protective factor for the emotional impact of environmental constraints (e.g., Pocnet et al. 2016b) and that emotion regulation can be seen as an adjustment feature (Reicherts et al. 2012). Our findings further support the assumption that tenacity in the pursuit of goals, which characterizes conscientiousness, also involves patterns of goal directed behavior that supports emotion regulation, which in turn promotes QoL (Augustine and Larsen 2015). In other words, adaptive emotion regulation includes behavioral adjustment to initiate and maintain the pursuit of goals instead of giving up, as also reported by Wrosch et al. (2007).

A few important limitations should be noted. When considering all personality aspects of interest simultaneously, our theoretical model would have become very complex and the results of indirect effects, although significant, become smaller (B standardized < 0.05). Given that this is the first study to test the role of personality traits, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation on QoL, we chose to consider the three personality dimensions separately in order to ensure good model properties. Future studies should further develop the underlying theoretical model, considering the more specific interplay between neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness, as well as self-efficacy and emotion regulation. Such a model should then be tested including a larger sample to enhance the statistical power and model fit. Furthermore, this study was based on cross-sectional data. Ideally, mediation effects should be tested longitudinally for a better understanding on the causality of the effects. Finally, in the present study, we were missing some information that may be crucial, which should be considered in future studies: besides including information on coping strategies to disentangle the effects of emotion regulation, context specificity should be taken into account, because situational constraints (e.g., dealing with a specific event) and individual differences (e.g., financial or health status) might better explain the ways in which individuals implement regulation attempts to reach a life of high quality.

Conclusion

Considering the direct and indirect effects of specific personality profiles on QoL, this study has expanded prior work on the relationship between personality and QoL by including emotion regulation and self-efficacy. The present study provides a promising approach for future inquiry that could further advance a more comprehensive understanding of how personality characteristics together with emotion regulation skills and self-efficacy beliefs contribute to QoL. As a starting point, our study demonstrates that both emotion regulation and self-efficacy are central mechanisms that link specific personality dimensions to QoL and, therefore, suggests the chaining and modulation of these complex effects. Given that these links have implications for the ways in which people experience their daily life and how they influence their affective experiences, more in-depth prospective studies are promising avenues to further our understanding.

References

Aluja, A., García, O., Rossier, J., & García, L. F. (2005). Comparison of the NEO-FFI, the NEO-FFI-R and an alternative short version of the NEO-PI-R (NEO-60) in Swiss and Spanish samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 591–604. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.014.

Augustine, A. A., Hemenover, S. H., Larsen, R. J., & Shulman, T. E. (2010). Composition and consistency of the desired affective state: The role of personality and motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 133–143. doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9162-0.

Augustine, A. A., & Larsen, R. J. (2015). Personality, affect, and affect regulation. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, M. L. Cooper & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol 4. Personality processes and individual differences (pp. 147–165). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28, 117–148. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Judge, T. A. (2001). Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9, 9–30.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2003). Personality predicts academic achievement: Evidence from two longitudinal university samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 319–338. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00578-0.

Charles, S. T., Reynolds, C., & Gatz, M. (2001). Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 136–151. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.80.1.I36.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668–678. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO-Five-Factor (NEO-FFI) professional Manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Chicago: Aldine.

Derryberry, D., Reed, A. M., & Pilkenton-Taylor, C. (2003). Temperament and coping: Advantages of an individual differences perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 1049–1066. doi:10.1017/S0954579403000439.

DeYoung, C. G., Hirsh, J. B., Shane, M. S., Papademetris, X., Rajeevan, N., & Gray, J. R. (2010). Testing predictions from personality neuroscience: Brain structure and the big five. Psychological Science, 21, 820–828. doi:10.1177/0956797610370159.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056.

Dumont, M., Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (2000). Sentiment d’autoefficacité. Traduction française du Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (Jerusalem, & Schwarzer, 1992). http://userpage.fuberlin.de/~health/french.htm.

Dupuis, M., Jopp, D., Congard, A. & Pocnet, C. (2016). Cross-national validation of a brief form of the WHO Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL-12) in French. (Submitted)

Duckworth, A. l., Weir, D., Tsukayama, E., & Kwok, D. (2012). Who does well in life? Conscientious adults excel in both objective and subjective success. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 356. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00356.

Eisenberg, N., & Spinrad, T. L. (2004). Emotion-related regulation: sharpening the definition. Child Development, 75, 334–339.

Field, N. P., Joudy, R., & Hart, D. (2010). The moderating effect of self-concept valence on the relationship between self-focused attention and mood: An experience sampling study. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 70–77. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.11.001.

Finch, J. F., Baranik, L. E., Liu, Y., & West, S. G. (2012). Physical health, positive and negative affect, and personality: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 537–545. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.013.

Hoyle, R. H. (2006). Personality and self-regulation: Trait and information-processing perspectives. Journal of Personality, 74, 1507–1526.

Hoyle, R. H., & Gallagher, P. (2015). The interplay of personality and self-regulation. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, M. L. Cooper & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol 4. Personality processes and individual differences (pp. 189–207). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for indexes in covariance structure analyses: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 56–83. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1992). Self-efficacy as a resource factor in stress appraisal processes. In R. Schwarzer (Ed.), Self-efficacy: Thought control of action (pp. 195–213). Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Jopp, D., & Rott, C. (2006). Adaptation in very old age: Exploring the role of resources, beliefs, and attitudes for centenarians’ happiness. Psychology and Aging, 21, 266–280. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.266.

Judge, T. A., Jackson, C. L., Shaw, J. C., Scott, B. A., & Rich, B. L. (2007). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: The integral role of individual differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 107–127. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.107.

Keating, N., & Gaudet, N. (2012). Quality of life of persons with dementia. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 16, 454–456. doi:10.1007/s12603-011-0346-4.

Kelly, W. E., & Johnson, J. L. (2005). Time use efficiency and the five-factor model of personality. Education, 125, 511–515.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principle and practice of structural modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kokkonen, M., & Pulkkinen, L. (2001). Extraversion and neuroticism as antecedents of emotion regulation and dysregulation in adulthood. European Journal of Personality, 15, 407–424. doi:10.1002/per.425.

Lepore, S. J., Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Ragan, J., & Ramos, N. (2000). It’s not that bad: Social challenges to emotional disclosure enhance adjustment to stress. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 17, 341–361. doi:10.1080/10615800412331318625.

Little, B. R., & Chambers, N. C. (2004). Personal project pursuit: On human doings and well-beings. In W. M. Cox & E. Klinger (Eds.), Handbook of motivational counselling (pp. 65–82). Chichester: Wiley.

Lucas, R. E., & Baird, B. M. (2004). Extraversion and emotional reactivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 473–485. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.473.

Lucas, R. E., & Diener, E. (2015). Personality and subjective well-being: current issues and controversies. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, & Cooper & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol 4. Personality processes and individual differences (pp. 577–599). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., Grob, A., Suh, E. M., & Shao, L. (2000). Cross-cultural evidence for the fundamental features of extraversion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 452–468.

Lucas, R. E., & Fujita, F. (2000). Factors influencing the relation between extraversion and pleasant affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 1039–1056. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1039.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149.

Maddux, J. E., & Volkmann, J. (2010). Self-efficacy. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of personality and self-regulation (pp. 315–331). Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Matthews, G., & Gilliand, K. (1999). The personality theories of H. J. Eysenck and J. A. Gray: A comparative review. Personality and Individual Differences, 26, 583–626.

Matthews, G., & Zeidner, M. (2004). Traits, states and the trilogy of mind: An adaptive states perspective on intellectual functioning. In D. Y. Dai & R. J. Strenberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion and cognition: Integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development (pp. 143–174). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McCrae, R. R., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2010). Self-regulation and the Five-Factor Model of personality traits. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of personality and self-regulation (pp. 145–168). Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Norem, J. K., & Chang, E. C. (2002). The positive psychology of negative thinking. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 993–1001. doi:10.1002/jclp.10094.

Pocnet, C., Antonietti, J.-P., Rossier, J., Strippoli, M.-P., Glaus, J., & Preisig, M. (2016a). Personality, tobacco consumption, physical inactivity, obesity markers, and metabolic components as risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the general population. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 3, 1–8. doi:10.1080/13548506.2016.1255767.

Pocnet, C., Antonietti, J-P., Strippoli, M-P., Glaus, J., Preisig, M., & Rossier, J. (2016b). Individuals’quality of life linked to major life events, perceived social support, and personality traits. Quality of Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1296-4.

Reicherts, M. (2007). Dimensions of openness to emotions (DOE): A model of affect processing. Manual. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Reicherts, M., Genoud, P. A., & Zimmermann, G. (2012). L’ouverture emotionnelle : une nouvelle approche du vécu et du traitement émotionnels. Wavre: Mardaga.

Roberts, B., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., & Goldberg, L. R. (2005). The structure of conscientiousness: An empirical investigation based on seven major personality questionnaires. Personnel Psychology, 58, 103–139. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00301.x.

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Bogg, T. (2005). Conscientiousness and health across the life course. Review of General Psychology, 9, 156–168. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.156.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36.

Schaefer, P. S., Williams, C. C., Goodie, A. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2004). Overconfidence and the Big Five. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 473–480. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.010.

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., & O’Connell, K. A. (2004). The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 13, 299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

Suls, J., & Martin, R. (2005). The daily life of the garden-variety neurotic: Reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of Personality, 73, 1485–1510.

Tamir, M. (2009). Differential preferences for happiness: Extraversion and trait-consistent emotion regulation. Journal of Personality, 77, 447–470. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00554.x.

Tsai, S. W-C., Chen, C. C., & Hui-Lu, L. (2007). Test of a model linking employee positive moods and task performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1570–1583. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1570.

Vollrath, M. (2001). Personality and stress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 335–347.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465.

Wilt, J., Nofle, E. E., Fleeson, W., & Spain, J. S. (2012). The dynamic role of personality states in mediating the relationship between extraversion and positive affect. Journal of Personality, 80, 1205–1236. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00756.x.

Wismeijer, A., & van Assen, M. (2008). Do neuroticism and extraversion explain the negative association between self-concealment and subjective well-being? Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 345–349. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.002.

Wrosch, C., Miller, G. E., Scheier, M. F., & Brun de Pontet, S. (2007). Giving up on unattainable goals: Benefits for health? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 251–265. doi:10.1177/0146167206294905.

Wrosch, C., & Scheier, M. F. (2003). Personality and quality of life: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Quality of Life Research, 12, 59–72. doi:10.1023/A:1023529606137.

Yik, M. S. M., Russell, J. A., & Steiger, J. H. (2011). A 12-point circumplex structure of core affect. Emotion, 11, 705–731. doi:10.1037/a0023980.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pocnet, C., Dupuis, M., Congard, A. et al. Personality and its links to quality of life: Mediating effects of emotion regulation and self-efficacy beliefs. Motiv Emot 41, 196–208 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9603-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9603-0