Abstract

The current paper relies upon Broadbent and Laughlin’s (Manag Account Res 20(4):283–295, 2009, Accounting control and controlling accounting: interdisciplinary and critical perspectives, Emerald, Bingley, 2013) notion of culture, context, and steering mechanisms to understand how context and culture mould PMS change in healthcare switching from one pathway to another. It employs the case study of an Italian regional health service carried out over a 3-year period (2010–2013) with 25 semi-structured interviews with relevant actors (regional councillors, CEOs of healthcare organisations, and physicians that are heads of health departments), and including the retrospective collection of data on the period 2005–2009 through respondents’ views supported by secondary data. The findings show a switch from the reorientation trough absorption response of the first period (2005–2009) to the reorientation trough boundary management towards evolution response of the second period (2010–2013). They highlight that this is the result of a change in context and the leading rationalities towards a policy based on cooperation and stakeholder dialogue through the development of a common language helping to supersede previous inability to interact. It enlightens that the change in the RHS came about in the wake of a hybridisation of all the actors involved which can be construed as an enlargement in their interpretive schemes happening at the individual level and influencing the organisational level. In the study RHS the change in context and culture favoured the formation of a managerial logic and an enrichment of the value system of the organisation towards a well-functioning PMS. In turn the PMS daily helps to reinforce the cooperative and dialogic approach, prompting a virtuous circle, and offering broader insights relevant to theory, practice, and the policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Despite the enduring concern for public sector accounting change and the interesting implications unveiled in literature, the role played by context and cultural features in shaping accounting change still need to be explored (Liguori and Steccolini 2014). The need for more research on accounting change is even more relevant, among public sector organisations, in healthcare settings, where performance management systems (PMSFootnote 1) have long been called potential enablers of positive reconciliation regarding the conflicting issues of cost containment, quality and accountability, but have brought about few positive results (Lapsley 2008; Anessi Pessina 2006).

The literature on healthcare often reports different phenomena of accounting change featured with either resistance or hybridisation of professionals (e.g. Kurunmaki 2004), but leaves some questions unanswered. For instance, accounting change faces the well-acknowledged measurement difficulties in the field (Lapsley 2008). It has to cope with the tendency of the processes—above all, the clinical ones—to be less transparent and more difficult to evaluate (Eeckloo et al. 2007; Anthony and Young 2005; Miller 2002). It also has to deal with the lack of commonly accepted indicators (Miller 2002) other than financial measures, as well as uncertainty about the power relationships between different groups of stakeholders (Hopper and Bui 2016). In particular, researchers increasingly contend that a context- and culture-sensitive understanding of accounting is of primary importance (Messner 2016; Broadbent and Laughlin 2009, 2013). Literature warns that to date this is still vague in healthcare (Spanò 2016; Caldarelli et al. 2013), despite being essential to comprehend better the outcome of any attempt to implement PMS.

Focusing on PMS implementation in healthcare settings, this paper aims to understand how cultural and contextual factors mould accounting change. The study relies upon Broadbent and Laughlin’s (2009, 2013) notions of culture, context and steering mechanisms—among which PMSs—and their transactional and relational nature. Broadbent and Laughlin (e.g. 2013) in their Middle Range Theory (MRT) take the Habermas’ concept of steering, highlighting that organisational responses to regulatory controls (as steering mechanisms) can vary depending on the differing value systems being held by organisations that make actors more prone to resist or to accept any changes. In the wake of previous work by Ferreira and Otley (2009), where contextual and cultural issues remained not explicit, the authors (2009, 2013) argue that the nature of steering mechanisms such as PMS is intentional and derives from a discourse of rationalisation. In so doing, they contend that it is important to comprehend how context and culture shape PMS.

Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) theorisation of accounting change and its possible pathways is suitable to unfold the peculiar nature of the Italian National Health Service (INHS). Previous papers have already employed MRT to interpret accounting change, focusing either on a single organisation (Fiondella et al. 2016) or on the regional level (Campanale and Cinquini 2015). Fiondella et al. (2016) reflect on the factors possibly influencing changing pathways, without making explicit the possible connections between context, culture and transactional and relational steering, and limiting their attention at the level of a single university hospital. Cinquini et al. (2015) depicted the factors determining colonising attempts but leave implicit the issues relating to possible changing pathways and limit their focus to clinicians.

The gaps emerging from these researches represent the areas of major contribution of our study. The current paper potentially enriches this debate using these works as a starting point to propose a broader interpretation of how context and culture mould accounting change. More specifically, we examine the case of the regional health service Alfa,Footnote 2 which in 2007 was forced to engage in actions to implement a PMS and was subject to a failure in the first period (2005–2009) turned into a more positive response of the second period (2010–2013). On this ground, the paper aims to answer the following research question: how cultural and contextual factors moulded the accounting change of the Alfa Region leading to shifts from one changing pathway to another?

The findings allow us to show that the instrumental rationality of the first period and the atmosphere of emergency resulted in the lack of clarity, top-down approaches, absence of transparency related to performance measurement aims, targets, procedures, and indicators. This fostered “absorptive” superficial changes driven by compliance worrisome leaving the core of the organisations’ values and beliefs completely unchanged. As a result, the transactional adoption of the PMS determined improved financial conditions, but not laying the bases for acceptance of the new measures.

On the contrary, such acceptance progressively appeared as soon as there was a change in the rationality of the region towards more communicative positions, and in the contextual conditions determined by better financial control, and the political and regulatory stability. The raising communicative rationality fostered more openness to dialogue and cooperation between stakeholders, with aims no longer restricted to the financial outcomes, but increasingly oriented towards the creation of a common discourse between the parties involved. The change in this case was played at the boundaries, not compromising the core values of the RHS but attempting to enriching them, and slowly fostering a change in the practices. This was possible thanks to cooperation and dialogue that took place for the accounting change and thanks to the accounting change, with the PMS used as relational media, to building on new relations and to reinforcing those already existing. The effort for common dialogical practices prompted a quite novel process of hybridisation of the parties involved, not limited to clinicians (e.g. Campanale and Cinquini 2015; Kurunmaki 2004), but extended managers, who earned basic medical knowledge and learned how to interact and communicate with physicians.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. The second section addresses the debate on accounting change, highlighting the importance of cultural and contextual features for a contribution to debate on PMS change in healthcare. The third section describes the conceptual framework. The fourth section presents the data collection and the research context. The fifth section summarises the findings. The sixth section discusses the implications of the study. In the end, we provide some concluding remarks.

2 Context, culture and control: accounting change in public sector

Accounting change is a topic that has been variously addressed focusing on the drivers and correlates of change; the conditions enabling change; as well as the politics of change; the role of influential agents; and the effects of power relationships (e.g., Abernethy and Vagnoni 2004; Dent 1991; Laughlin 1991; Miller and O’Leary 1987). However, this debate is far from over, leaving room for empirical and theoretical speculations.

Understanding change in accounting systems requires a comprehension of the intrinsic nature of organisations, and the public sector offers remarkable insights (Broadbent and Guthrie 1992). Liguori and Steccolini (2014) in their editorial introduction to the 2014 special issue of Critical Perspectives on Accounting What’s accounting got to do with it? Accounting, innovation and public sector change, provide a commentary on the extant research on accounting change in the public sector. They call for more research on the role played by contextual and cultural conditions (see also Hopper and Bui 2016; Busco et al. 2015; Liguori 2012a, b; Liguori and Steccolini 2011).

Burns and Vaivio (2001) and Messner (2016) highlight the importance of a context- and culture-sensitive understanding of accounting. These authors explain that such knowledge has been pursued along different theoretical paths such as contingency theory (e.g., Gerdin and Greve 2008; Hirst 1981; Otley 1978), institutional theory (e.g., Brignall and Modell 2000; Modell 2003; Ezzamel et al. 2012), governmentality (e.g., Kurunmäki and Miller 2011; Miller 1992; Miller and O’Leary 1987), and practice theory (Ahrens and Chapman 2007; Schatzki 1996, 2002). These frameworks have been applied in many specific settings (regarding country, and industry) and an infinite number of context and cultural characteristics can be called as influencers of accounting change (Cinquini et al. 2015).

This literature opens a reflection on the interplay of factors such power and power coalitions, political creeds and interests, culture, values, environmental conditions, in shaping accounting change processes (Liguori and Steccolini 2014), which is relevant—among public sector organisations—for healthcare settings. In this domain, reforms have often ended up in failures, due to scarce acknowledgement (and awareness) of the peculiarities of this field and of the competition between costing and caring (Lapsley 2008; Anessi Pessina 2006).

Several studies have pointed out that in healthcare resistance and communication barriers affect the introduction of control tools, which consequently are only formally relied upon (e.g., Jacobs et al. 2004; Kurunmaki 2004; Broadbent et al. 2001; Jones 1999; Abernethy and Stoelwinder 1995; Chua and Degeling 1993; Preston 1992). This happens because dominant groups of professionals are used to performing their complex tasks independently (Abernethy and Stoelwinder 1995). They deal with the problematic dialectics of two conflicting logics: the management’s on the one hand, and the professional’s on the other (Caldarelli et al. 2012; Jacobs et al. 2004; Kurunmaki 2004). Possible role conflicts could emerge when healthcare professionals face control systems restricting their autonomy (Broadbent et al. 2001; Abernethy and Stoelwinder 1995), because they could attempt to evade them (Jacobs et al. 2004; Kurunmaki 2004).

Other researchers have shed light on the processes of hybridisation of clinical professionals, supporting the accounting change (Conrad and Uslu 2011; Eldenburg et al. 2010; Lehtonen 2007; Jarvinen 2006; Abernethy and Vagnoni 2004; Jacobs et al. 2004; Kurunmaki 2004; Coombs 1987). These studies have argued that the emergence of accounting systems cannot be explained merely as being contingent upon changes in environmental conditions and internal structures, but also depend on medical knowledge, practice and motivation (Nuti et al. 2013; Jarvinen 2006; Preston 1992). These studies highlight the critical role of clinicians in healthcare and their attitudes towards accounting tools (Conrad and Uslu 2011; Eldenburg et al. 2010; Lehtonen 2007; Abernethy and Vagnoni 2004; Jacobs et al. 2004; Kurunmaki 2004; Coombs 1987) that become a means of mediation among traditionally contrasting actors (Wickramasinghe 2015).

This summary shows that there is contradictory evidence on accounting change processes taking place in healthcare that leave wholly unanswered the issues relating to whether and how shifting responses to change may emerge in the field. From this perspective, a culture- and context-sensitive understanding of accounting change in healthcare is essential. This allows us to encompass featuring aspects such the increasingly changing regulations and environment, the power and politics of change, the role of influential actors, the hardly measurable financial and healthcare delivery performance, the opacity of the processes, and the broad accountability demand (e.g. Fiondella et al. 2016; Hopper and Bui 2016; Kurunmäki and Miller 2011; Eeckloo et al. 2007; Anthony and Young 2005; Kurunmaki 2004; Miller 2002; Chua and Preston 1994).

On these grounds, the purpose of the paper is to understand how cultural and contextual factors mould accounting change, leading to shifts from one changing pathway to another, in healthcare settings. To this aim, we rely on Broadbent and Laughlin’s (2009, 2013) conceptualisation of culture, context and steering mechanisms—among which PMSs—and their transactional and relational nature.

This framework is powerful for developing a critical understanding of empirical areas which have been actively engaged in changing PMS design (Broadbent and Laughlin 2009) and have faced systematic attempts to control performance (Modell 2003). Such suitability applies to both single organisations (e.g., Manes Rossi et al. 2018; Agrizzi et al. 2016; Fiondella et al. 2016) and broader institutional dynamics (e.g., Cinquini et al. 2015; Broadbent and Laughlin 2013; Broadbent et al. 2010). Indeed, this framework acknowledges that even in the smallest organisation it is possible to target sub-units with very different responses to change, and reminds that in practice hybrid forms can be detected. Moreover, as Fiondella et al. (2016) point out, this framework facilitates the examination of a broad range of factors in a coordinated effort, with relevance for complex settings such as healthcare.

It is worth noting, on this regard, that previous literature employing this framework to analyse accounting change in healthcare represents an essential starting point of this paper. A first contribution is by Campanale and Cinquini (2015). The authors focus on the Tuscan Region and employ Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) conceptualisation of changing pathways to understand the interaction between management accounting (as a design archetype) and clinicians’ interpretative schemes. They unveil dynamics of interactive colonisation for clinicians with interpretive schemes and design archetypes influencing each other. However, their main focus on clinicians and clinical dimensions does not allow to fully tap into the complexity of the interactions among actors encompassing additional perspectives. Moreover, in this paper the chance of shifting pathways remains overlooked. Such perspectives, instead, have been depicted by Fiondella et al. (2016) that relying upon the Broadbent and Laughlin MRT revealed how the change in the MAS of a healthcare organisation was successful due to the involvement of professionals in the ongoing process of change. In respect to Campanale and Cinquini (2015), however, Fiondella et al. (2016) views remain restricted to the organisational level, leaving room for reflections on how these dynamics would function in a different institutional setting and with multiple additional elements to consider. Moreover, both papers employ the theoretical framing of the MRT looking extensively at the possible changing pathways but leaving implicit the issues relating to how culture (rationality) and context impact on PMS design and PMS operationalisation. All these gaps, form instead the major areas where the current paper attempts to offer a contribution. In so doing, our paper also complements and extends the contribution by Nuti et al. (2013). This study discussed what factors led to a successful implementation of the performance evaluation system in Tuscany, but leaving the above-cited influences of cultural and contextual features implicit and underdeveloped.

3 Context, culture and control: a conceptual framework for accounting change

Broadbent and Laughlin model represents an operationalisation of Jürgen Habermas’ Critical theory (Power 2013) and traces complex connections between the language of accounting and how these ideas are integrated into current social systems (Lehman 2006, 2013). They take the Habermas’ concept of steering, highlighting that the internal colonisation of the life-world/interpretative scheme arises not only at the societal level but also at the organisational level. They argue that organisational responses to the regulatory controls (as steering mechanisms) can vary depending on the differing value systems being held by organisations that make actors more prone to resist or to accept any changes. Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) contend that every societal organisation has its own interpretive scheme, design archetypes and subsystems where the design archetypes, such as PMS, attempt to balance and make coherent the interpretive scheme and subsystems. To unfold how these dynamics take place and to comprehend how public sector accounting change works, Broadbent and Laughlin (2009) in acknowledging the importance of Ferreira and Otley’s PMS framework,Footnote 3 make a case for the importance of the role played by culture (that they label rationality) and context.

To explain their views, they clarify that “in relation to culture, it is important to make the way that the PMS links to lifeworld and interpretive schemes more explicit and that this is achieved by clarifying the underlying model of rationality that guide the development of the resultant PMS” (Broadbent and Laughlin 2013, p. 73). Thus, the authors, following the political orientation of Habermas’ work,Footnote 4 include the comprehension of cultural features in the broad conception of rationality, and signal the importance to comprehend the rationality of the controllers—of those in power—who can influence the nature of the PMS, and the context in which it operates. Broadbent and Laughlin (2009) clarify that any differences in the PMS design depend on the rationalities that are in action. The authors borrow the possible rationalities that can mould PMS discourses—instrumental and communicative—from Habermas’ critical theory (1984) and his interpretation of the Weberian ideal types.

Instrumental rationality in the Weberian sense is based on a rational calculation about the specific means of achieving definite ends and is based on the search for efficiency. Habermas (1984) questions whether rationalisation is solely the diffusion of instrumental rationality or purposive-rational action (Alvesson and Deetz 2000). He puts forward his theory of communicative action, arguing that ends, in whatever form, should not be predefined but should find their definition, and legitimacy, through the discursive processes. Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) contend that instrumental rationality may lead to transactional steering mechanisms, which implies narrowly defined outputs and outcomes (the ends), and often a specification of the means to be used to achieve these ends. Broadbent et al. (2010) exemplify this circumstance through reference to a contract to undertake a particular project over a definable period, in which the (instrumental) objectives, the process and the rewards (usually financial) are defined.

In this regard, Agrizzi et al. (2016) argue that transactional approaches are characterised by a command and control style and a something for something logic, which does not admit negotiation between stakeholders. Communicative rationality may lead to relational steering approaches less, if not, prescriptive and agreed thanks to deliberation and discourse between stakeholders. Usually, relational steering is considered regulative and justifiable (Laughlin 2007; Laughlin 1995a, b; Laughlin and Broadbent 1993) as it ensures more freedom to actors in comparison to transactional steering.

Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) signal that the two ideal types of relational and transactional PMSs should be regarded as extremes of a continuum, and it is likely that some PMSs—even in the same organisation—can empirically have both transactional and relational characteristics. For example, instrumental rationality may lead to a transactional adoption of the PMS due to precise and pervasive mandatory regulation, but then the PMS is implemented through relational approaches to the process of change and holds relational (less prescriptive) characteristics about ends and means.

On regard to the issues of context, Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) offer a twofold problematisation. On the one hand they look at the context in broad terms, encapsulating in this concept all the internal and external challenges and opportunities that exert a direct or indirect influence on the organisation and that, in turn, the PMS is intended to control. These contextual features mould the PMS design by defining the aspirations to fulfil and interacting with the rationalities in action (that instead are a-contextual). It in healthcare settings possibly deals, as Fiondella et al. (2016) signal, with issues of stability/instability of the political and regulatory environment, formal/substantive compliance to regulation, and financial conditions. In addition, Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) devote attention to the specific effect of context on the PMS operationalisation. The context in this case is referred to precise elements of finance and accountability and depends upon the prevailing model of rationality in place.

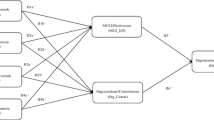

Drawing on Broadbent and Laughlin’s model (2009, 2013) we examine the process of accounting change of the Alfa RHS, following the conceptual descriptors summarised in Fig. 1 below.

To better comprehend how PMS change may practically take place thanks to the interaction of cultural and contextual features, as reported in Fig. 1, Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) clarify that there is the need for an empirical flesh. The authors clarify that when a process of change is triggered, different pathways may arise.

The first of these pathways is morphostasis (first order change) and takes place when changes are merely cosmetic, thus incapable of affecting the organisational routines, which quickly come back to the origins. Morphostasis may take two different routes.

Firstly Rebuttal, that arises when an environmental disturbance produces changes in the design archetypes, but later they come back to the original situation. The rebuttal is a highly risky strategy especially in the case of precise expectations or fragmented initiatives; it can be achieved if the alternative action proposed is shown to work and can benefit from a value-driven context (Laughlin et al. 1994).

Secondly, Reorientation, that results from an environmental disturbance affecting subsystems and compulsory internalised, but unable to challenge the interpretive schemes. Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) put forth two alternative ways through which reorientation occurs, that is through absorption or boundary management.

Reorientation through absorption is a change that cannot be rebutted but being perceived as dangerously touching the ethos and values of the organisation, is not accepted and is just played at the periphery of the daily practices. The absorptive strategy relies upon ‘a specialist work group’, that shows compliance with the accounting control expectations. This group ensures that they do not impinge the ‘real work’ of the organisation and its interpretive schemes (Broadbent et al. 2010; Broadbent and Guthrie 2008; Broadbent 1992). Reorientation through absorption is painful to achieve when the changes are very precisely detailed and intrusive (Mir and Shiraz Rahaman 2007; Broadbent 1992).

Reorientation through boundary management is based on cautious acceptance of the disturbance, as the controls forced by regulatory pressures are more embedded in the organisational design and practices, even if they do not undermine the organisation’s interpretive scheme but are played at the boundaries. It can transform into colonisation (Agyemang and Broadbent 2015) or evolution (Fiondella et al. 2016).

The second pathway is morphogenesis. Morphogenetic changes permeate the organisation bringing about profound changes. These modifications can be either mandatory or free and non-compulsory and are respectively labelled Colonisation and Evolution. Colonisation appears when the change is internalised by an authoritative minority which values and ethos become the new interpretive schemes. These stakeholders may use positional power and subtle tactics to force the change (see Dent 1991) that represent a success for the colonisers but not for the organisation. Dent (1991), Broadbent (1992) and Mir and Shiraz Rahaman (2007) propose stimulating discussion of the colonising dynamics. Evolution derives from a change deliberately and freely agreed upon by all stakeholders, and thus based on broad consensus (Laughlin 1987; Spanò et al. 2017). Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) contend that this decisive role of accounting controls, seen as beneficial tools, rarely appears in public sector where often, as in the case of the Private Financing Initiative (PFI) in the UK, revolution (colonisation) is likely to happen.

For the purposes of this paper we take Fig. 1 as model of reference to better tap into the changing process of the Alfa Region, and to understand how (and why) this RHS switched from one pathway to another.

4 Research context and data collection

4.1 The Italian NHS

The INHS is made by a system of autonomous regional health services (RHSs) understood as holdings with power and control rights (Longo 2003). Each RHS has the responsibility to deliver essential care levels, choose its model of governance, set objectives, plan activities and appoint or remove managers. RHSs differ in terms of such aspects as a region’s capacity to adopt effective measures to invest state funds and use taxation, the level of integration in terms of activities engaged in by the Department of Health, the ability to regulate the health service defining roles and responsibilities, whether there are any inter-organisational contracts, and the extent of the use of management accounting systems (Caldarelli et al. 2013).

Formez (2007) categorised Italian RHSs, as Autocratic, Centred, or Contractual ones. Autocratic RHSs, were featured by hierarchical relationships between the regional governing board and the healthcare organisations, with scarce autonomy and limited communication; that is RHSs which according to Broadbent and Laughlin’s model (2009, 2013) and Spanò (2016) have a prevailing instrumental rationality; Centred RHSs were characterised by a regional governing board, which is more prone to communicate but not willing to negotiate conditions with healthcare organisations; that is RHSs which are guided by an instrumental rationality, but show certain openness towards communicative instances; and Contractual RHSs were based on a model with a high level of autonomy for healthcare organisations, collaboration and cooperation at any level, prominent role of the private organisations, as well as on-going processes of negotiation; that is RHSs which according to Broadbent and Laughlin’s model (2009, 2013) and Spanò (2016) are more oriented towards a communicative rationality.

More recently, Nuti et al. (2016) offered an updated categorisation of the Italian RHSs, identifying different clusters for the period 2007–2012, and displaying a higher degree of heterogeneity. The authors show that five models of governance—Hierarchy and Targets, Trust and Altruism, Choice and Competition, Pay for Performance, Transparent Public Ranking—are variously combined on the national territory, determining different and mixed leading rationalities in each RHS. Drawing on these views, for instance, the papers by Nuti et al. (2013, 2016), contend that among others, the Tuscan performance evaluation system (PES) represents a successful case of accounting change. They highlight the benefits deriving from a visual reporting system, the linkage between PES and CEO’s reward system, the public disclosure of data, the high level of employees and managers involvement into the entire process, and a strong political commitment.

The Tuscan example can be understood, under Broadbent and Laughlin’s (2013) model, as a case of prevailing communicative rationality leading to a relational PMS. As Caldarelli et al. (2013) and Spanò (2016) posit, the dominant type of rationality has most influenced the response of Italian RHSs to the introduction of performance measurement systems overtimes, determining either fully transactional and fully relational PMSs, or in the majority of cases hybrid PMSs with both elements. In this regard, the suitability of Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) to examine an RHS lies in the fact that the reliance on the empirical flesh and the skeletal nature of this model allow us to encompass the multifaceted features of such a level of analysis. It enables us to consider that the implementation of a PMS with hybrid characteristics is likely to occur.

From the contextual perspective, RHSs differ in no small degree because of political, socio-economic, and environmental factors. These factors fit the conception of context put forth by Broadbent and Laughlin (2013), as they do not influence the model of rationality in place, but impact PMS design in many different ways (e.g., stability vs instability of the political and regulatory environment, formal vs substantial compliance to regulation, financial balance/imbalance). Such conditions may well impact PMS operationalisation regarding finance and accountability.

4.2 The Alfa RHS

The current paper examines the case of the regional health service Alfa, selected drawing on previous studies on the Italian RHSs (Caldarelli et al. 2012, 2013; Formez 2007).

Alfa is one of the largest regions in the south of Italy. From the socio-economic and demographic perspectives, Alfa is far from the average of the other Italian regions (see the Bank of Italy Report on the financial economic state of Italian Regions 2009), with adverse consequences for the health of citizens (Evaluation Report, 2012; Regional Health Plan 2010; Formez 2007). Alfa is increasingly affected by the phenomenon of ageing (20% of the population are above 65 years old), and from the epidemiological perspective, certain diseases have reached incidence and chronicity rates higher than in other RHSs (Ministry of Health report 2010). Also, Alfa has suffered high turbulence in the political spheres in the last 15 years (determining strategic discontinuity for healthcare), fast-changing regulations, and financial constraints.

Alfa potentially provides a lesson to learn as it experienced a failure in PMS change, turned into a posture more prone towards evolution in recent years. The growing attention for PMS by Alfa dates back to 2002 and was the consequence of normative turbulence at the National level and raising accountability pressures, increasingly calling for cost containment and quality. Such pressures led to attempts to introduce managerial tools in search for legitimacy. It also triggered additional but unsystematic actions taking place in 2005, that failed to achieve the above-cited expectations due to the lack of coherence and substantive adaptation to the specificities of the setting. This caused persistent bad performance in the period between 2005 and 2007, which resulted in tighter normative pressures by the central government and a mandatory plan for debt recovery. The pressures deriving from this situation forced Alfa to engage in actions to improve the existing PMS, which was only formally adopted in 2005 in the wake of increasing regulation.

The case of Alfa is compelling as it experienced a change in the contextual features towards more stability from the financial (also thanks to the above-cited Recovery Plan started in 2007), political, and regulatory perspectives. As literature signals, Alfa also experienced a change in the prevailing rationalities in place, shifting from the Autocratic model (under the Formez categorisation) to the mixed Hierarchy and Targets and Trust and Altruism model (Nuti et al. 2016), thus from leading instrumental rationality to more communicative rationality.Footnote 5

The results of this process can be positively evaluated (LEA Check 2012) since the region has been able to reduce its financial deficit and to implement a PMS deemed to be acceptable to those involved (Evaluation Report of the Alfa RHS 2012), even if it is still under the control of a special commission. The presence of the special commission (appointed by the President of the Council of Ministers) is mandatory for Alfa. It was created due to regulatory requirements in the wake of the financial deficit emerged in 2007. The special commission since 2007 has been an active actor of the change, and part of the so-called specialist work group entitled to carry out the process. Its composition has changed various times in the first phase of the process, reaching a relative stability in the years 2010–2013. The presence of the commission, due to its active role is not considered as a contextual factor in the discussion. Moreover, it is worth specifying that although the performance of the region Alfa from the economic and financial point of view has shown improvements (also thanks to the recovery plan) over the years, regarding a reduction of the deficit, the commission remains in charge until the deficit is eliminated.

4.3 Data collection

The case study addresses the process of change in the PMS taking place between 2010 and 2013. It is well acknowledged that a focus on a more extended period is advisable for understanding accounting changes, as these processes are the product of multiple iterative and oscillatory factors (Liguori and Steccolini 2011). Hence, following Liguori and Steccolini (2011) the case study was carried out ex-post, retrospectively reconstructing the antecedents of the change (2005–2007) and the first phase of the PMS implementation (2007–2010) by interviewing people involved in the process before the data collection began, and observed the phenomenon as it developed (2010–2013). Such an approach is valuable, as people’s interpretation of a change is required to shape the future course of change, and this process allows a more profound analysis of any transformation. However, because retrospective reconstruction can also suffer a bias due to ex-post rationalisation (Trochim and Donnelly 2006), we relied upon a triangulation of multiple data sources. Data collection involved semi-structured interviews carried out over a 3-year period archival analyses, and participant observation when possible.

A preliminary step was to review archival material. Such review involved looking at official and publicly available documents, as well as internal documents (summarised in Table 1). These evidence with the theoretical model of reference formed the basis for the semi-structured interviews.

The interviews were carried out with representatives of the categories of actors involved in the process of change: regional councillors, CEOs of healthcare organisations, and physicians that are heads of health departments. We also gathered the perceptions of other personnel in the field, such as nurses and physicians not holding managerial positions. On the contrary, due to privacy reasons, we did not interview patients, and their views are only implicitly addressed in a limited way by referring to physicians’ approaches to the change.

We interviewed six people who were directly involved during the first period of change (2005–2009) and 12 people who have been involved since 2010. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed for analysis soon after the event. A telephone follow-up with the respondents was conducted after a few data were found to be missing, with the conversations recorded and soon transcribed for the analysis. Before the analysis of the data, the interviewees were asked to review the transcripts and to make any corrections. Where necessary, we made further visits to confirm some of the information or to follow up on something which had arisen in another meeting, amounting to a total number of 25 interviews (see Table 2 below).

During the interviews, the researchers paid special attention to the actors’ perceptions relating to the change process. The researchers gained details about how the interviewees felt about their roles, the PMS’s role in the context of reference, and the practices and management tools available within the region, as well as how they perceived the newly introduced PMS and the impact of changes on their activities. An effort was put to comprehend the actors’ perceptions in relation to the PMS design, with regard to the level of multidimensionality, the openness to learning and cooperating within or outside the regional system, the degree of integration of different control tools, and the procedures for communication, sharing and collaboration.

4.4 Data analysis

Following Yin (2003) and Ragin et al. (2006) the data have been coded to identify the important patterns of the PMS change. The archival material (e.g. the available categorisation of RHS governance models), the interviews and other official reports available formed the starting point to collect these data. Then, from the issues raised by interviewees, we turned to consider how these factors influenced further changes in regulation and power coalitions, going beyond the mere political level to consider various professionals’ alliances. Any changes in financial and clinical performance were also monitored. The coding of the interviews took place through a two-step process since it not only relied upon the theoretical descriptors, but it also benefited from a comparison between these and the data gathered (both interviews and archival resources). Appendix offers several examples of the coding of the interviews that was carried out as follows.

Following the framework represented in Fig. 1, we considered changing regulation and changing power-political coalitions and their consequences regarding the culture of control and beliefs, transparency of the processes, the participation of change agents. For each type of prevailing rationality, we identified expected characteristics of the PMS, such as the types of views (secret vs shared); control tools relied upon (many tools with few effort vs few tools with big effort), use of control tools (as means of punishment vs as means of dialogue); routines and use of the PMS. For each category several assessment criteria have been identified to understand the posture of the RHS in each specific domain.

Referring to relevant literature embracing the same theoretical approach of the current paper (Broadbent and Laughlin 2009; Fiondella et al. 2016; Cinquini et al. 2015; Agrizzi et al. 2016) the questions were designed so at to gain full insights into the process of change, its motives, its stages, and its outcomes.

For the issues relating to the types of views we considered several aspects. We looked at how mission and vision are conceived (i.e. emphasis on clinical, financial, or mixed outcomes), communicated, and understood; we explored how key success factors are established, communicated, and understood; we checked how RHS organisational re-design is established, communicated, and understood; we inquired how strategy and plans are established, communicated, and understood.

For the issues relating to the control tools relied upon we considered how key performance indicators and related targets are established, communicated, and understood. Also, we investigated how performance assessment procedures and criteria are established, communicated, and understood.

Finally, for the issues relating to use of control tools we assessed whether the RHS relies upon systems of rewards and penalties and the reasons driving these choices. Instead, in relation to the routines and use of the PMS we looked at the information flows, systems and networks established, as well as at the reporting practices and the related timelines, to understand their main characteristics, how they were designed and agreed upon, and whether these are shared and comprehended by actors involved.

This approach allowed us to understand how the contextual features and the prevailing rationality evolved and how such evolution shaped the PMS design and operationalisation, leading to a shift from the absorptive responses occurring at the beginning towards progressive acceptance of the PMS, thanks to the boundary management strategies prompted by the specialist work group.

Following the theoretical model of reference, the findings are presented to describe the evolving factors moulding PMS change, that is rationality and context, and focusing on the PMS design. More specifically, in adherence with previous research by Fiondella et al. (2016), Broadbent and Laughlin (2009) and Manes Rossi et al. (2018) the course of events at the Alfa RHS is interpreted looking at the driving rationality (instrumental vs communicative) and the main contextual elements (e.g. political stability, regulatory environment and regulatory pressures, financial conditions) for the two main periods of change, i.e. the years 2007–2010 and the years 2010–2013. Also, we look at the PMS design and development, by highlighting what type of interactions took place among the institutional actors involved; the tools introduced, the implications for people, and any resisting subjects; the role played by the specialist work group in overcoming the upcoming difficulties and the strategies enacted to engage resisting subjects. Finally, the questions of PMS operationalisation in terms of finance and accountability have been deepened showing the differences between the two periods examined.

5 Findings

5.1 The PMS in 2007–2010

The change phase that took place between 2007 and 2010 was characterised by embryonic efforts in PMS implementation. The Specialist Work Group slowly began committing to the new logics to achieve morphostatic change—specifically, reorientation through absorption (Broadbent and Laughlin 2013)—as at the end of 2009, acceptance of the new logics increased but operationalisation did not yet appear. People adopted a formally compliant behaviour to satisfy the mandatory requests that could not be rebutted, mainly to avoid sanctions, but the PMS was not internalised in the daily practices, being perceived as dangerously touching the ethos and values of the organisation (Broadbent and Laughlin 2013). Specific contextual and cultural features can be identified as factors moulding this kind of response. Focusing on context, factors relating to financial imbalances, political instability and regulatory discontinuity are major intervening elements. From the cultural perspective, the actions of the first period were driven by a prevailing instrumental rationality, that drawing on Broadbent and Laughlin (2013) resulted in a transactional adoption (due to regulation) and transactional implementation (concerning the approach to the accounting change) of the PMS. Over this period the specialist work group enacted an absorptive strategy to assure that the compliance with accounting controls did not impinge the ‘real work’ of the organisation and its interpretive schemes (Broadbent 1992; Broadbent et al. 2010; Broadbent and Guthrie 2008).

An explanation of how this process took place follows.

The interviews carried out allowed us to understand the state of the art when the process of change slowly started in 2007. One of the Councillors (of the majority elected at that time) clarified that Alfa already before 2007 tried to implement a PMS, but these endeavours ended up in failures. He explained that a first attempt, in the wake of national reforms (e.g., decree 229/1999) dates back to 2002 and resulted in claims within the Regional Health Plan relating to the lack of managerial tools and regional information systems to support possible improvement actions, thus highlighting the need to overcome these limitations as a priority. The Councillors signalled that the failure of this first attempt was due the inability to go beyond the statements of intent, as nothing was truly put into practice. Then, a second attempt can be traced back to 2005 when for legitimacy purposes the region was willing to achieve the aims of cost containment, enhanced quality, the reorganisation of the healthcare departments, an integrated network for the delivery of care, and a well-functioning information system.

Nevertheless, at the beginning of 2007, when Alfa had to adopt a Recovery Plan in the wake of the healthcare deficit, despite the past attempts, the designed PMS was only formally relied upon due to quickness, the absence of involvement, primary focus on financial concerns, and lack of transparency.

One of the CEOs interviewed critically asserted that:

For the sake of rapidity (emphasis added), the process undertook was carried out only at a governmental level, and the PMS design was just influenced by the economic circumstances, but unable to fully capture the dimensions of quality of the health service delivered.

Another CEO, with medical background, highlighted that a significant concern was the absence of clear guidelines, with no transparency at multiple levels, in a highly politicised and turbulent environment, which led people to doubt the chance of a likely change and thus reject the PMS. He stated:

The lack of transparency permeated any area of intervention because some innovations relating to performance measurement and information flows were often cited but never clearly depicted, thus endangering communication between the various regional levels and actors. No transparency and the coercive bottom-up imposition of many not correctly understood tools and techniques meant that the majority of the physicians strongly opposed the process of change.

In particular, there was no agreement on how and through which tools the region should realise control systems and information flows. Indeed, those in charge for the change claiming that the autonomy of local healthcare organisations was fundamental, discharged their responsibilities attempting to put forth a consolidation role on the basis of the data provided by such organizations (thus treating the RHS as an empty box).

One of the physicians, head of health departments usefully summarised the main contextual features that at the beginning of 2007 led to a PMS formally relied upon: the already mentioned financial deficit, the unstable elected majority, the regulatory pressures coming from the INHS.

It is clearly impossible to trace linear relationships between these contextual factors that operated simultaneously in the Alfa Region. However, the Councillor interviewed noted that the regulatory pressures coming from the INHS not only increased because of the financial imbalances but were difficult to manage due to the power coalitions instability. In addition, the PMS design was influenced by the conventional approach of the region, based on hierarchical relationships, limited autonomy, and limited communication, the processes of change were guided by instrumental rationality.

To satisfy the national regulatory requests the (weak) majority elected created a specialist work group made of a few influential people, with no medical background, only looking for a quick compliance with the requirements. The specialist work group main aim was to satisfy internal accountability demands mainly centred on financial questions, and then thoroughly neglected any issue specific to healthcare delivery. These people attempted to pursue colonising intents using positional power and subtle tactics to force the change. However, they failed because of the strong ideology characterising the healthcare setting that allowed to restrain the changes.

Reasons for failure can be ascribed to the severe limitations identified during the interviews, that touched all the areas covered, as these were not only related to the fuzzy development of a founding view for the PMS, but also on the lack of clarity and agreement on the types of control tools and their use, as well as on the absence of transparency for the issues of information flows, networking activities, and reporting practices.

The reasons for failure were effectively summarised by one of the CEOs interviewed.

We received a booklet containing guidelines that referred to the timeline and methods to transfer the data required from the healthcare organisations to the region but did not address the issues relating to how the PMSs should have been structured to ensure comparability (and fair evaluation!). It goes without saying that the objectives were quite obscure and not specific, and the assessment procedures and criteria for the healthcare organisations were not identified. We had no space for consultation, has the game was played on different tables.

Clearly, the lack of clarity on the mission and vision resulted in a faint definition of the key success factors, again limited to economic-financial questions. Yet, the issues relating to the organisational structure were completely neglected, while all the questions relating to key performance indicators, target setting, performance assessment activities, rewards and penalties, information flows, systems and networks were cited in several documents, but not profoundly addressed.

The strategies and plans were mainly reliant on economic and financial issues, and not shared among the local healthcare organisations. Furthermore, the reporting process was difficult to manage in the absence of guidelines for information flows between the departments and the top management of healthcare organisations. This lack of transparency in the information flows led the majority of the physicians to strongly oppose the requests for information about their tasks and their performance. Such opposition were enhanced by the absence of instructions in terms of data to be collected and reported to the region, and the dangerous lack of transparency on the assessment procedures.

One of the Councillors interviewed was able to elaborate more on these problematic issues:

The PMS was mainly at the regional level, with a limited degree of thoroughness, shallow guidelines, and no specific reference to the role of healthcare organisations in managing the process. I had meetings with some CEOs and physicians, and they argued that the problems were related to the absence of instructions concerning data to be collected and reported to the region, and the dangerous lack of transparency on the assessment procedures.

About the inadequacy of the criteria for the assessment procedures, one of the CEOs with medical background also pointed out that:

Although the criteria considered to measure the performance were referred to as appropriateness, mobility and mortality, the emphasis was mainly on the achievement of financial balance, efficiency and effectiveness, while quality and the health of the population were unjustifiably neglected. I mean… The focus was only financial… at any cost!

At the end of 2007, following regulatory pressures and the adoption of the recovery plan, Alfa slowly engaged actions to design a more appropriate PMS and to implement it. For the triennium 2007–2010 the major tool remains the Recovery Plan. The transactional adoption of the recovery plan with the related linear cuts and constraints, as imposed by national regulation, was fundamental because over this period Alfa gained control of the financial imbalances. Usually, tools such as the recovery plan come across with unpleasant perceptions and are dealt with in a pessimistic yet scared way. However, in this case, the recovery plan was an opportunity for Alfa and represented a genuinely positive achievement. The Plan posed the basis for better contextual conditions for the intervention of the following years. It does not describe the result of the PMS implementation, for which it is not possible to detect any acceptance or substantive functioning. Instead it is the consequence of a normative intervention to cope with a pathologic condition of the regional health system. Over the 2007–2010 the Recovery Plan brought about two main positive achievements. Firstly, it was extremely helpful to re-establish financial balance.Footnote 6 Secondly, it posed the bases for reflections and analyses of the mistakes made, with the Alfa RHS increasingly committed to figure out possible solutions. Despite the increasing awareness of the problems, the situations remained quite unchanged until mid-2010 as the following subsection explains.

5.2 The PMs in 2010–2013

The phase between 2010 and 2013 featured several actions, enacted by the Specialist Work Group to deal with the above-cited problems and to engage in actions towards stakeholders’ consensus for the PMS implementation and use. The period 2010–2013 marked significant differences in the contextual and cultural conditions of the Region that need to be addressed to comprehend how the change took place.

The Specialist Work Group worked in specific financial, political and regulatory conditions. Firstly, in addition to the prominent role of the Recovery Plan, from the contextual point of view, we signal the changing dynamics that were taking place in 2010, with a newly elected (this time large) political majority at the Regional level. Such elections are commended as an important point in the changing processes for a twofold reason. The composition of the Regional council brought about stability in the normative environment and a diminished pressure at the national level. The diminished worrisome about financial imbalances reduced the emphasis on the sole hierarchy and target concerns typical of the previous leading to instrumental rationality, to increasingly leave space for cooperative approaches informed by the trust and altruism model and towards a more communicative rationality (Nuti et al. 2016).

A more detailed explanation of how these dynamics took place follows.

Focusing on the issues relating to the new driving rationalities surrounding the change, one of the CEOs with medical background clarified that:

Since 2010 the new regional board demonstrated more openness and willingness to foster collaboration and deliberative decision-making. The specialist work group organised a series of meetings to share the founding views of our new PMS, also employing experts from another region that had already faced this kind of accounting changes.

Participation was also ensured through a renewed composition of the specialist work group entitled to the change, which was made of a more significant number of people, with different backgrounds, looking for a substantive compliance to discursively agreed and negotiated requirements. This also encompassed the inclusion of representatives of the political opposition, given the importance of the healthcare sector and the superior aims under tutelage. This was an important signal of the new rationality in place given the well-known high politicisation of healthcare in Italy. Moreover, the presence of non-political figures in the Specialist Work Group was useful to avoid the mere interaction between political parties, in the absence of specific expertise, limiting the danger of simply political choices with no substantive effects.

One of the Councillors part of the specialist work group and belonging to the political opposition explained that:

Our aim (of the specialist work group) was to satisfy broad accountability demands, in a very complex setting and securing the defence of the professionals’ identities, acting as protectors of the ideologies in place, but also putting an effort in expanding the views of the people involved to render them committed to the change.

Another founding element of the deliberative approach chosen—that led to an evolutionary type of reorientation trough boundary management pathway—lies in the provision of a readily understandable booklet of guidelines. The commitment for the realisation of such deliberatively agreed document was essential to ameliorate the dimensions relating to the clarification of what the founding view for the PMS was, and how this could be put into practice.

The booklet was realised and discussed thanks to a multidisciplinary team made of managers, physicians, researchers, and sociologists, to account for very different exigencies from both the medical and managerial points of view. A strong effort was devoted to sharing the mission of the RHS, that is Protection of the right to health of communities and people, ensuring universal equality and equity of access to care, delivery of all care activities provided by the Essential Levels of Assistance, freedom of choice and attention to information and public participation (Regional Health Plan 2010).

The interviews showed a significant level of communication and understanding within the Alfa RHS, highlighting the fact that the region had succeeded in focusing a wide range of people on what was important by ensuring a shared understanding of the overarching purpose of the organisation. The responses from the interviewees revealed broad and ranging views and included better cooperation between different healthcare organisations and the region to increase effectiveness and quality of the services delivered, better communication between people inside each organisation, improved accountability, cost containment and the enhancement of human resources.

This new trend in the Alfa RHS was evident from one of the CEOs with medical background quotes.

The challenge was to get the balance between the two imperatives. One is the institutional imperative of delivering high-quality health services. The second is the economic-financial imperative, that is operating effectively and efficiently which relates to the health expenditure and alike. Thanks to meetings and consultation we agreed that the PMS in improving the economic performance has to serve significant interests as the equality and equity of access to care, and above all the quality of our clinical tasks. It is not an easy task for me handling all this financial data, but it turned from being a tedious compliance task to become an outstanding chance to do more and do it better.

Moreover, another interviewee, a Physician head of health department admitted that he was positively surprised by the new approach at the regional level, and provided the example of the problematic issue of beds cuts.

After many years of obscurity and secrecy, the Regional board has finally decided to disclose the aim and the criteria driving the process of change. Now it is clear that there will be no longer linear cuts but that the RHS is learning from other experiences, and that negotiation is a new way! The RHS has suffered tensions because of the reduction in the number of beds (about 8%) and departments or due to the unification of healthcare organisations and territorial districts (the number of local health organisations was reduced about 50%). Despite some strong oppositions, I value the fact that we were involved in the process and that the regional board was likely to consider alternative approaches that we tried to propose.

Thanks to the above-described cultural and contextual features, the PMS completely changed between 2010 and 2013, with the changes not merely imposed, but instead negotiated. The recipe for this success, given the newer communicative rationality in place, the political stability, the regulatory stability, and the financial imbalance control, was made of the following ingredients.

The actions were driven by shared views, dialogic approaches, and multilateral efforts. Alfa was profoundly committed to sharing its strategy through the Regional Health Plan and other documents. This renewed effort in clarifying and sharing the mission and objectives resulted in a number of actions to supersede the lack of clarity and agreement on the types of control tools and their use. Also, it determined greater transparency for the issues of information flows, networking activities, and reporting practices.

In particular, the plan issued at the end of 2010 thoroughly addressed the objectives, actions, and means to achieve them. It was also integrated with additional documents (performance management systems manual; regional guidelines for management, accounting and auditing; Regional guidelines for the definition of the Plan of Cost Centres and Centres of Responsibility, and the budgeting process) elaborated in a coordinated effort with the representatives of healthcare organisations to set the general objectives of the region and the specific goals of each healthcare organisation.

The new PMS was structured with a balanced focus on the region and the single healthcare organisations, with particular attention to the information systems improvement. The new PMS has also developed thanks to the participation to a benchmarking table with other RHSs and benefited from external counselling. The actors involved welcomed such a strategy as a signal of transparency and quality, also lauding the flexibility and adaptability of the model proposed to the specific exigencies of each setting. The appreciation is evident in the following quotes from one of the CEOs.

We appreciated the actions undertaken by the regional board to build consensus before proceeding. This led us to feel not threatened, and stimulated a proactive spirit, reassuring us on the adequacy of the exigencies of the health system.

Moreover, the attention of the Region was constantly devoted to identify what tools were to be used and how to implement them, to favour a coherent territorial action and to avoid losing resources in costly and scarcely understandable systems. Thus, Alfa requested to all the organisations in the RHS the reliance on tools such as budgeting, cost accounting, reporting, and performance assessment, offering, differently from the previous experiences, profound implementation guidelines and continuous mentoring.

The participative approach was helpful in identifying the key performance measures and in supporting target setting both at the central level and for each organisation. The realisation of a coherent performance assessment system based on agreed procedures, targets, criteria, and indicators was realised by the specialist work group relying upon the knowledge acquired through the participation to the above-cited benchmarking table, and closely looking at the existing practices within the territory in order to identify a baseline to discuss and improve. The main challenging issues involved considering the multidimensional aspects of performance. Indeed, over the previous years the limited focus on financial issues and the lack of a broader driving logic for performance measurement, together with the lack of transparency and sharing of the main views of the PMS were cited as major justifications by those people unwilling to conform to the change in action.

To avoid the attitude by several physicians to indulge in formal effort to mimic performance measures acceptance, while sticking on their own convincement through management by exceptions, the specialist work group put effort in profoundly renewing the performance assessment in order to meet the expectations of these resisting actors. Thus, it was essential to find a balance between objective and quantifiable measures (of both financial and economic performance and clinical effectiveness and quality), and the qualitative issues relating to not objectively measurable medical questions involving professional critical judgement (e.g. those frequent cases in which the clinical choices ensuring the higher quality for patients are those with higher medical costs).

Moving from extant available information and measure, the specialist work group realised a set of general objectives to fulfil and targets to meet, also identifying the related indicators that were soon reported in the Regional Health Plan (efficiency, mobility, quality, appropriateness, effectiveness and the health of the population). As said, this set was a very general and flexible reference that admitted justified variations as per the cases recalled above. Acceptance of such measures was favoured by the chance of considering these specific conditions. Also, acceptance was favoured by the clarity that characterised the process to communicate this set of measures to those in charge of performance measurement and reporting, from both the clinical and the managerial sides. Detailed communication relating to the driving logics, of the measures, the expected effects, and the ways to handle the assessment was crucial to supersede possible resistance by people involved. One of the physicians head of health departments participating to the preparatory phase of these indicators clarified that:

We could refine the indicators in case of specific exigencies of healthcare organisations, for example for university hospitals or centres of excellence, perceiving them more reliable and fairer. The specialist work group made it clear that the criteria that were considered to carry out performance evaluation tasks were those listed in the Plan and also provided an explanation about the content and the importance of each measure and the expected targets for the following 3 years. A target for each indicator was identified, also considering the average national values for the dimensions monitored.

An example is the indicator appropriateness. Appropriateness represents the use of a resource or service most suitably or efficiently. Alfa measures appropriateness as the DRG (diagnosis related groups)/HDG (homogeneous related groups) to monitor the economic consequences of diagnostic and clinical choices. Alfa still shows a higher ratio in comparison to other regions and deserves more effort because the target is to align the degree of appropriateness to the national level. However, the broad awareness of the importance of this dimension represents a valuable aspect of the performance measurement system realised. Another example refers to the extra-regional mobility measure. This measure is based on the provision that the region getting incoming mobility of patients reaps an increase in revenue, while the region suffering outgoing mobility incurs an expense. The monitoring of this indicator adds to the knowledge of citizen’s perceptions of the quality of care and shows possible areas for improvement. Alfa has reduced its mobility at the magnitude of 5% in line with the target identified. Other examples are reported in Table 3.

The new PMS acquired legitimacy in the eyes of the actors involved because the whole evaluation process was improved with its core procedures, the information flows, and the reporting practices and times, discussed and negotiated at various stages, allowing for critiques and amendments, also highly commending the importance of constant networking activities between different structures and professionals with heterogeneous backgrounds.

With regard to the negotiation, we quote one of the Councillors of the political majority:

The interaction between people with different backgrounds, such as managers, physicians and we as policymakers, and the practical knowledge that everyone has of its own tasks, allowed us to end up with a solution compelling the various needs of different subjects. This is an excellent way to avoid wasting resources to implement useless procedures and unreliable evaluations.

Concerning evaluation subjects, it has been made clear that the healthcare organisations should be evaluated first as a whole system, based on a mixed consideration of economic and qualitative elements (that we already reported above). Then, the CEOs and heads of the departments were also evaluated by their specific economic and qualitative objectives. The committee performing the annual assessment was made up of experts from other regions to ensure separation between the controlled and the controllers. This committee is required to change every 3 years and is composed of managers and physicians to provide the proper comprehension of all the aspects related to healthcare organisation performance. One of the physicians not holding managerial positions interviewed enthusiastically stated that this approach was favourably perceived because not only it ensured objectivity in the assessment but also an awareness that in healthcare not everything is quantitatively measurable. This also implies that the Alfa Region does not need to stick on a reward-sanction system because:

Lousy performance results directly in the cut of the financial resources, and in some cases in the chance that people are removed from their positions by the regional board. Moreover, an adverse clinical performance impacts on the reputation of either the healthcare organisations or the departments, resulting in a migration of patients from one to another, with a bad relapse on the financial dimension. Factors such as professional ethics and job satisfaction are much more impacting than punishment or reward and push all of us to do our best.

A crucial innovation of the PMS, linked to the new transparent evaluation process, is the standing IT platform that completely changed the face and practice of reporting. All the information provided by the healthcare organisations and the single departments are collected through this platform. However, the upload of the report is handled manually by each subject and not yet linked to the individual information systems implemented in the healthcare organisations, due to the distinct stages of this process of implementation in the various institutions.

As one of the Councillors argued:

This can cause problems in terms of timely update of the information and heterogeneity. For this reason, the region decided to create a special section on the IT platform dedicated to consultation, assistance and advice in case of doubts on the issues relating to the reporting of data.

During the second half of 2011 small changes have been made to correct some of the deficiencies that have arisen to make the IT Platform user-friendlier. This has contributed to improved results in terms of timeliness and the quality of information already, as noted in the evaluation report of 2012.

In summary, if we look at the PMS in use within the Alfa region, it is possible to maintain that it is permeated by strong economic-financial orientation, due to the bad performance achieved in the previous years and the special plan of recovery. However, it gives ample space to the clinical dimension, as it devotes attention to the effectiveness and appropriateness of the care. Its value-added lies in the constructive manner in which managers, physicians and councillors interact through the PMS to challenge prior assumptions and to rethink the strategic priorities of the region. In particular, it allows to consider the existing programs of scientific excellence and also to the projects that can improve the state of health of the population, towards a new vision of control as an element to support the quality of the healthcare.

On the basis of all the above, we can assert that the phase between 2010 and 2013 featured several actions, enacted by the Specialist Work Group, that relied on relational steering mechanisms derived from a prevailing communicative rationality, leading to reorientation through boundary management (Broadbent and Laughlin 2013). This resulted in progressive and cautious acceptance of the external disturbance. Over this period, the Specialist Work Group continuously enhanced the breadth and relevance of the relational steering PMS and ensured that all stakeholders consciously reached a consensus. As a result, the controls forced by regulatory pressures became more and more embedded in the organisational design and practices, even if they did not undermine the organisation’s interpretive scheme (Agyemang and Broadbent 2015; Fiondella et al. 2016). This was realised in a more stable financial environment, with a stable political majority and ensuring less turbulent regulatory environment. In addition to the prominent role of the Plan, from the contextual point of view, we signal the changing dynamics that were taking place in 2010, with a newly elected (this time large) political majority at the Regional level. Such elections are commended as an important point in the changing processes for a twofold reason.

Firstly, the new composition of the Regional council brought about stability in the normative environment. Since 2010 there was a turnaround in the regulatory process and a diminished pressure at the national level. This left space to consider regulation as the means to satisfy exigencies expressed thanks to deliberative processes, and not to comply with central government demands formally (e.g. Fiondella et al. 2016).

Secondly, and also thanks to the renewed financial control reached through the recovery plan, the new council marked a different approach to performance management in healthcare devoting attention to quality issues and financial/economic questions as two sides of the same coin.

This led to a transactional adoption (due to regulation) and relational implementation (in terms of an approach to the accounting change) of the PMS that was increasingly accepted by people, impacting routines and practices and contributing to improving the performance of the RHS as a whole. Those in charge of the change opted for boundary management strategies leading to a PMS that was progressively accepted and put into use by those involved (Manes Rossi et al. 2018; Spanò et al. 2017).

However, despite the positive results and the success achieved, some minor difficulties persist in the Region Alfa. Some of the physicians remained firmly against the changes, and resolutely refused to participate in any meetings. Moreover, often the specialist work group found it difficult to manage conflicts arising during the negotiations, especially concerning the accreditation programs, that at the end of 2013 remained a mostly unsolved question.

5.3 The changing operationalisation of the PMS in the Alfa Region

On the basis of all the above it is worth clarifying that the PMS was subject to different operationalisation trends over the periods analysed. Such operationalisation depends on the transactional or relational nature of the PMS that is derived from the model of rationality of the organisation.

It is worth remembering that over the period 2007–2010 the instrumental rationality resulted in the adoption of an extremely transactional PMS. Indeed, in line with Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) this phase was characterised by an instrumental rationality leading to narrowly defined outputs and outcomes and a specification of the means to be used to achieve these ends, featured with compliance and strictly financial objectives (Broadbent et al. 2010). In more detail, In the beginning, the transactional nature of the PMS, with decision making relegated to the regional board, led to a high regard for the (coercive) financial dimensions and neglected accountability to citizens. The PMS despite the effort of the specialist work group (made of few powerful people pursuing colonising intents) was resisted. As already argued, the financial achievements were obtained thanks to the legal constraints and the linear cuts applied in the wake of recovery plan and were not connected to the PMS in use, thus exacerbating the relationships between stakeholders within the territory. Such a situation mirrors what Agrizzi et al. (2016) argue about transactional approaches, that are characterised by a command and control style and a something for something logic, which does not admit negotiation between stakeholders.

However, after 2010 Alfa switched from instrumental rationality towards a more communicative one. Since 2010 Alfa has attempted to involve a number of different actors in the process to set up goals and the means to achieve them. This approach well exemplifies a communicative rationality that according to Broadbent and Laughlin (2009, 2013) may lead to relational steering approaches less, if not, prescriptive and agreed thanks to deliberation and discourse between stakeholders. Such a change benefited from the combined effects of contextual factors slowly evolving since 2008 and stabilised after 2010, also with a transforming role of the Recovery Plan that was increasingly perceived as an opportunity because the reduced financial deficit (after its transactional adoption) opened space for reflections on quality-related issues. From the contextual perspective, Alfa experienced improvements in the clinical performance, greater political stability and in power coalitions at the professional level (that helped to reduce the CEO turnover), and diminished regulatory pressure. This less turbulent climate together with a more communicative rationality resulted in a transactionally adopted but relationally implemented PMS in which, in line with previous literature (Laughlin 2007; Laughlin 1995a, b; Laughlin and Broadbent 1993) the ends and means were agreed upon through a discourse between stakeholders and the PMS was considered regulative and justifiable as it ensured more freedom to actors.