Abstract

Background

In this pilot study, the breastfeed care plus intervention program was implemented to support women and their families in breastfeeding success. Primary interests were women’s self-efficacy in breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding.

Methods

A pilot study was developed in the region of Aveiro–Portugal in two Family Health Units. The experimental and control groups consisted of sixteen women each, initially. Four home visits with assessment and guidance focused on breastfeeding support aimed at women and families were delivered in the experimental group, while the control group received conventional care. Both groups were followed between the 5th and the 120th day postpartum and were subjected to three evaluation moments.

Results

On the 120th day postpartum, eleven women completed the BCP intervention program (three women stopped breastfeeding), and nine women received conventional care (seven women stopped breastfeeding). Both interventions proved to be effective in improving the ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy,' with higher scores being found in the experimental group (p < 0.001). The proportion of exclusive breastfeeding was also higher in the experimental group.

Conclusions for Practice

The BCP intervention program, during the first 120 days postpartum, showed promissory results in improving ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy’ compared to conventional care, favoring breastfeeding duration and exclusivity, and cumulative breastfeeding competence of women/families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

Some healthcare systems have well-established home visit programs for the postpartum period. The Portuguese Healthcare System has identified increasing the rate of breastfeeding as a priority. One of the major factors that may influence mothers in opting to breastfeed, is their own perception of maternal self-efficacy. In Portugal, there is a lack of field studies on this subject; therefore, this study serves as evidence that regular home visits by family health nurses in the postpartum and postnatal period can influence women’ self-efficacy. Our findings may encourage other researchers to conduct larger studies to confirm these results.

Introduction

Breastfeeding increases potential gains in maternal/infant health, with short-, medium-, and long-term beneficial effects for the family, community, health and social system, the environment, and society in general (Victora et al., 2016). Protection, promotion, and breastfeeding support are public health priorities worldwide (Cattaneo et al., 2005; WHA, 2016).

At present, given the rationalization of costs and the prevention of hospital infections, hospitalization of the puerperal women and the newborn after delivery tends to be reduced (Benahmed et al., 2017), and therefore, breastfeeding may not be properly established at the time of maternity discharge. Despite all international and national directives, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Portugal is below suggested recommendations (Bosi et al., 2016; WHO & UNICEF, 2014).

The latest breastfeeding record of the Portuguese Directorate General of Health (DGS, 2014) shows 76.7% of women had Exclusive Breastfeeding from birth to maternity discharge, 67.5% maintained Exclusive Breastfeeding in the 5th week after delivery and 22.1% persisted at 5 months postpartum. A recent study (Kislaya et al., 2020) mentions that the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 4 months and up to 6 months in Portugal, respectively, was 48.5% and 30.3%, highlighting the need for strategies and initiatives to promote exclusive breastfeeding after discharge from maternity until 6 months.

According to national (DGS, 2015) and international guidelines (WHO, 2014), postnatal home visits (HV) should be carried out to improve adaptation to the parental role and to provide effective support in the promotion of breastfeeding. Postpartum marks the transition to a new phase of the family life cycle, encompassing a critical transition time in physiological, psychological, relational, and social terms for the child's mother/infant/child's father triad and remaining family (Gillath et al., 2016).

For successful breastfeeding, a combination of key factors such as the decision to breastfeed, the establishment of lactation, the social support for breastfeeding, lactation education, and maternal self-efficacy should be accomplished (Busch et al., 2014; Levy & Bértolo, 2012).

A crucial factor is maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy, which according to the breastfeeding self-efficacy Theory of Dennis (1999), is a mother’s perceived ability to breastfeed her infant, and it has been identified as one modifiable predictor of breastfeeding duration and exclusivity and also acknowledged as an important variable affecting breastfeeding outcomes that may be amenable to intervention (Dennis, 2003).

Breastfeeding self-efficacy is driven by four sources of information: (1) performance accomplishments, (2) vicarious experience of seeing other mothers breastfeed, (3) verbal persuasion by influential others, and (4) the mother’s physiological/affective state (Dennis, 1999).

Assessing women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy in postpartum can identify women at high risk of breastfeeding discontinuation and with the necessity of breastfeeding support (Economou et al., 2021) and helps the Family Health Nurse to identify the nursing focus, construct nursing diagnoses, and develop interventions and strategies for the promotion, protection, support, and capacitation of woman/family towards successful breastfeeding, promoting this way to family health and well-being at this important stage in the life cycle.

To the literature, some family members exert an influence on the self-efficacy and success of breastfeeding (Ferreira et al., 2018; Negin et al., 2016; Prates et al., 2015); therefore, postpartum care should be family centered, with the guidance of a Family Health Nurse with adequate skills, knowledge, and training (Webber & Serowoky, 2017) through the appointment and/or Home Visit (HV).

The randomized controlled trial (Vakilian et al., 2020) and the systematic review and meta-analysis (Chipojola et al., 2020) mentions that the education intervention focused on increasing woman’s breastfeeding self-efficacy and HV are one adequate tool to facilitate support, the transmission of knowledge, resolution of breastfeeding problems, and competence building of the woman/family, promoting the breastfeeding duration and exclusivity.

Therefore, maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy can predict initiation of breastfeeding (Lau et al., 2018) and breastfeeding outcomes at 1 and 2 months postpartum in women of full-term infants (Brockway et al., 2017). Breastfeeding intervention programs based on the breastfeeding self-efficacy theory affect woman’s breastfeeding self-efficacy scores and consequently lead to better breastfeeding outcomes in the early postpartum period (Chipojola et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2020).

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Maleki et al. (2021) references that the most effective education on breastfeeding self-efficacy is in the first week after maternity discharge, and it is observed up to the 24th week postpartum. This finding means that it is very important to continue breastfeeding education to increase women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy in postpartum.

Portugal has scarce experimental studies, mainly in breastfeeding self-efficacy, and most of the guidelines adopted are based on literature produced abroad. Simultaneously, it is recommended that breastfeeding educational intervention should be continued for several weeks postpartum to gain its benefit (Maleki et al., 2021). So, studies regarding the improvement of breastfeeding self-efficacy using breastfeeding intervention programs in a larger period of postpartum need to be carried out, even if it is at the local or in a small region.

In this study, the authors developed a pilot study with a nursing intervention based on regular home visits which aimed to improve women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy, and support women to breastfeed successfully once discharged from Maternity up to 120 days postpartum and assess satisfaction with an intervention program in the Aveiro region—Portugal, compared with conventional care.

Methods

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre Regional Health Administration (28NOV’2017:88/2017). At the fifth antenatal appointment (between 34th and the 35th week and 6 days of gestation), participants were given information about the pilot study's aim, procedures, and ethical issues. Only participants who provided written informed consent were able to enroll in the study.

Participants and Setting

This pilot study took place in Aveiro–Portugal’s region, in two Family Health Units of Baixo Vouga between January and September of 2018. The recruitment period was January to May of 2018 and 68 women met the eligibility criteria and were invited to participate in this study. The inclusion criteria were defined: woman’s age ≥ 18 years, singleton infant delivery at a gestational age of > 36 weeks, without medical problems and still breastfeeding at children’s health appointment (CHA) 1 or HV1. The women were allocated randomly to the experimental or control group if they belonged to Family Health Unit (FHU) Santa Joana, or the control group if they belonged to Family Health Unit Atlântico Norte, due to lack of logistic means to provide intervention at home in this setting.

Study Design and Interventions

A pilot study developed between the 5th and the 120th day postpartum. The BCP Intervention Program was implemented only in the experimental group (EG), whereas the control group (CG) received conventional care (CC). Both interventions are described in line with the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) (Hoffmann et al., 2014)—Table 1.

The BCP intervention program is a new nursing care intervention program based on regular home visits implemented to child’s mothers/fathers/family at home, in four HV postpartum, and aims to assess the knowledge of the child’s mothers/fathers/family on breastfeeding; promote support, training and empower the child’s mother/father/family in the breastfeeding success; educate about risk factors that lead to the breastfeeding abandonment; improved maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy; provide guidance and positive reinforcement on woman's breastfeeding performance; and discuss the inaccurate perception of women’s capabilities.

During the home visit, the research nurse made “face-to-face” interactive health education sessions with proactive support, each lasting for 40–60 min, and assessed and made an intervention on breastfeeding; exclusive breastfeeding sucking reflex; breast engorgement; and lactation. The perception of the woman’s breastfeeding self-efficacy was evaluated, aiming to identify the woman with low efficacy and risk of early breastfeeding abandonment, and support and confidence in woman’s ability to breastfeed were promoted, encouraged the woman to express breastfeeding feelings, attitudes, and concerns and answered woman's questions and doubts. Support evidence-based thematic pamphlets were provided with specific advice: benefits of breastfeeding; breastfeeding techniques; breastfeeding problems; and their solutions. Joint decision making of the child's mother/father/family was encouraged in the breastfeeding practice and continuously reinforced the father/family’s role throughout the process.

The BSES-SF assessment after the intervention was aimed to ensure that the next intervention was tailored to meet the woman’s requirements. Until 120 days postpartum, four HVs are scheduled: HV 1—Until the 7th day postpartum; HV 2—Between the 15th–20th day postpartum; HV 3—Between the 30th–35th day postpartum; and HV 4—Between the 115th–120th day postpartum.

Conventional care (CC) is the standard care implemented during the children’s health appointment in FHU, and aims to assess the knowledge of the child's mother/father on breastfeeding; promote, support, and empower them to maintain breastfeeding. Until 120 days postpartum, three children’s health appointments (CHA) are scheduled in FHU: CHA 1—First week postpartum; CHA 2—Appointment at 1st month postpartum; and CHA 3—Appointment at 4th month postpartum.

During the children’s health appointment, each lasting for 20–30 min, the family nurse has made "face-to-face" interactive sessions, assessed, and made the intervention on breastfeeding; exclusive breastfeeding sucking reflex; breast engorgement; and lactation. The perception of the breastfeeding woman's self-efficacy on breastfeeding was also evaluated, the woman with low efficacy was identified, and strategies to promote breastfeeding were implemented. It was identified and educated to risk factors that lead to breastfeeding abandonment.

Participants were assessed at baseline (up to 7 days postpartum), between 30 and 35 days postpartum, and 115–120 days postpartum.

The following outcomes were measured: women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy (primary outcome), breastfeeding exclusivity, reasons to stop breastfeeding, and woman’s satisfaction degree with the nursing care received (secondary outcomes).

Outcome Measures

All women completed a baseline questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of four parts: the woman completed the first three and sent it to FHU at each subsequent contact (in the EG without the presence of a Research Nurse to minimize bias), whereas part four was completed by the nurse (when applicable) using the phone call method. Table 2 summarizes the timing that the questionnaires were applied.

Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale—Short Form (BSES-SF)

The BSES-SF Portuguese version (Santos & Bárcia, 2009) was used to determine the primary outcome of this pilot study: women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy. The BSES-SF is a 14-item self-report instrument to rate several items using a 5-point scale (the response scale ranges from 1 = not at all confident and 5 = very confident). The theoretical range of the scale is 14–70, and a higher score means the woman has more confidence in her ability to breastfeed. Being short and simple to fulfill, BSES-SF is a reliable and validated instrument to measure the woman's confidence in her ability to breastfeed, and it is used to identify and recognize women with less confidence, who may be predisposed to discontinue breastfeeding earlier. Also, it can help identify women requiring additional intervention and support to ensure breastfeeding success (Dennis, 2003). The BSES-SF Portuguese version internal consistency has Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.95. The woman evaluated the BSES-SF 48–72 h after intervention and sent it to FHU.

Exclusive Breastfeeding

Exclusive breastfeeding was used according to the definition of WHO and UNICEF (2008), which mentions that an infant receives only breast milk, no other liquids or solids are given—not even water, except oral rehydration solution, or drops/syrups of vitamins, minerals, or medicines. Exclusive Breastfeeding was evaluated in CG by the Family Nurse and EG by the Research Nurse at each subsequent contact. The information about infant feeding practices and frequencies, regarding supplemental feeding including formula, other liquids, solids, medication, vitamin, mineral drops, or oral rehydration solution that were introduced in the past 7 days, was obtained by questioning the woman.

Reasons to Stop Breastfeeding

The reasons to stop breastfeeding were categorized: breasts (engorged breasts; mastitis; sore or cracked nipples; breast abscess), milk (low milk supply; poor milk supply), infant (incorrect infant attachment; infant would not breastfeed; infant crying; infant not gaining sufficient weight), woman (woman started working; breastfeeding takes too long; maternal anxiety; maternal medication) and other reasons. They were described by the woman during a telephone call made by the family nurse or research nurse.

Woman’s Satisfaction Degree with Nursing Care Received

The woman’s satisfaction degree with nursing care received was evaluated by including a single question focusing on the satisfaction with the breastfeeding support provided, using a 4-point scale, ranging from ‘not satisfied’ to ‘very satisfied.’ The woman was evaluated 48–72 h after intervention and sent to FHU.

Socio-demographic and Clinics Variables

The socio-demographics and clinics variables included woman’s age, marital status, delivery type, parity, gestational age at birth, previous breastfeeding experience, and Graffar scale adapted (Amaro, 2001), family life cycle stage according to Carter and McGoldrick (1989) and Smilkstein's family apgar scale (Smilkstein et al., 1982).

The Graffar scale adapted (Amaro, 2001) evaluates the family’s socioeconomic conditions, classifies the family in the dimensions: occupation, education, the origin of family income, type of house, and place of residence. The family is ranked in 1 to 5 grades, where each grade implies a score of 1–5, respectively, and allows to classify the social class in I—upper class (score of 5–9); II—upper middle class (score of 10–13); III—middle class (score of 14–17); IV—low middle class (score of 18–21); and V—low class (score of 22–25).

The family life cycle stage, according to Carter and McGoldrick (1989), is a predictor of important transitions and changes that the family passes and gives an understanding of each family’s perception. The family life cycle is classified into six stages: 1. Leaving home: single young adults; 2. The joining of families through marriage: the new couple; 3. Families with young children; 4. Families with adolescents; 5. Launching children and moving on; and 6. Families in later life.

The Smilkstein's family apgar scale (Smilkstein et al., 1982) is a family function test, evaluates family members' perception about family functionality, expressing their satisfaction’s degree in fulfilling the family’s basic parameters. The 5 dimensions are evaluated by 5 questions with 3 possible answers, composed of a rating type scale varying the score between 0 and 2 points (namely almost always = 2 points; some of the times = 1 point; hardly ever = 0 points). The total score suggests the perception of family functionality being family with marked dysfunction (0–3 points), family with moderate dysfunction (4–6 points), and highly functional family (7–10 points).

The first six enrolled participants did not mention any difficulty in understanding and filling the questionnaire. The self-completion time ranged from 15 to 20 min for full form (Part I to Part III) and eight to ten minutes for Part II and Part III.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis to assess the primary outcome included a linear mixed model analysis of variance with estimation by ‘maximum likelihood restricted,’ defining the covariance structure as ‘unstructured.’ For each group, a proportion comparison for breastfeeding exclusivity and woman’s satisfaction was analyzed between initial and final evaluation. For sample description, absolute and relative frequencies of categorical or nominal variables were calculated, and mean and standard deviation for the interval or continuous variables. Differences between groups on sociodemographic and clinic variables were assessed with appropriate testing. The statistical significance level was set at α = 0.05, and data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 24.

Results

During the recruitment period (January to May of 2018), 68 women met the eligibility criteria. Twenty women refused to participate, the remaining 48 women applied the inclusion criteria during the postpartum period, which resulted in the exclusion of 16 women: five preterm newborns’ mothers who were breastfeeding; ten full-term newborns’ mothers who were not breastfeeding; and one woman aged < 18 years. Thirty-two women were then allocated randomly to the experimental or control group.

At baseline, the EG consisted of 16 women at the family health unit Santa Joana and the CG of 16 women at both family health units. At follow-up, 12 women abandoned the study: five women in the EG (three women stopped breastfeeding, one withdrew from the BCP intervention program, one did not answer the phone call to arrange a home visit) and seven women in CG (stopped breastfeeding). Eleven women in the EG and nine women in the CG remained in the study (120th day postpartum). The participant’s flow throughout the study is summarized in Fig. 1.

Participants’ Characteristics

The mean age of women was 33.1 ± 6.0 years old in the EG and 31.7 ± 4.1 years old in the CG (p = 0.43), and most reported being ‘married/common-law marriage’ (EG n = 16; 100% and CG n = 15; 93.7%). The families were mostly ‘nuclear’ (EG with n = 11; 68.8% and GC with n = 15; 87.5%), with a ‘high/medium high’ socioeconomic level (EG with 68.8%; n = 11 e CG with 56.3%; n = 9). In family life cycle stages, both groups were predominantly constituted by ‘Families with young children’ (EG n = 14; 87.4% and CG n = 12; 75.0%), and women perceived their family as ‘highly functional’ (EG n = 16; 100% and CG n = 15; 93.8%).

Dystocia delivery (EG n = 9; 56.3% and CG n = 9; 56.3%) by cesarean section (EG n = 5; 31.3% and CG n = 5; 31.3%) was the most frequent in both groups, with a gestational age mean of 39.1 ± 1.2 weeks in the EG and 39.2 ± 1.7 weeks in the CG (p = 0.35). Most of the women were primiparous, particularly in the EG (n = 12; 75.0%).

All of the multiparous women previously breastfed, with a mean duration of 4.3 ± 5.1 months in EG and 10.1 ± 9.6 months in CG (p = 0.21).

There were no statistical differences in terms of the participant´s characteristics between the EG and CG (Table 3).

Perception of Breastfeeding Self-efficacy Between Groups and Efficacy of BCP Intervention Program

Both interventions had a positive effect on improving ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy,’ but this was most effective in the EG (EG∆, M3−M1 = 18.8 points and CG∆, M3-M1 = 6.9 points (Table 4). The result for the linear mixed model returned an effect for time, F (1.24) = 47.1, p < 0.001, and for the interaction between ‘time’ and ‘group,’ F (1.24) = 23.5, p < 0.001, confirming the significant effect of the BCP intervention program in improving ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy’ in comparison to conventional care.

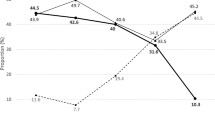

Breastfeeding Exclusivity to the 120th Day Postpartum

Up to the 120th day postpartum: three women stopped breastfeeding (n = 3 after the 35th day but before the 115th day) in EG. In CG 7 women stopped breastfeeding (n = 1 before the 15th day postpartum, n = 2 after the 15th day but before the 20th day, n = 4 after the 35th day, before the 115th day).

Between the initial evaluation and final evaluation, there was an increase in the proportion of exclusive breastfeeding in both groups (EG∆, M3-M1 = 40.9% and CG∆, M3−M1 = 10.4%), although this was markedly more pronounced in the EG [EG∆ with CI 95%: (0.11; 0.71) and CG∆ with CI 95%: (− 0.29; 0.49)]. At the 120th day postpartum (4th month), the exclusive breastfeeding rate was 90.9% in EG and 66.7% in CG (Table 4).

Reasons for Stopping Breastfeeding

The reported reasons for stopping breastfeeding are described in Table 5. The most frequently reported reasons were ‘Low milk supply,’ and ‘Infant crying.’ It was possible to observe in most of the women more than one reason for the stop of breastfeeding, some of which corresponded to amenable conditions for healthcare interventions, such as ‘Incorrect infant's attachment,’ ‘Infant cried,’ ‘Maternal anxiety,’ and ‘Flat nipples.’

Women’s Satisfaction Degree with Nursing Care Received Between Groups

The majority of the women reported being ‘Very Satisfied’ with the orientations/clarifications given to them by the Nurse during CHA or HV, which shows a good quality of care provided.

Discussion

In this pilot study, a nursing intervention program based on regular home visits, the BCP Intervention Program, was implemented in the Aveiro region—Portugal. The aim was to improve women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy and support them and their families in successful breastfeeding once discharged from Maternity, up to 120 days postpartum, and assess satisfaction with the BCP intervention program.

The BSES-SF scale was evaluated by the women 48–72 h after intervention, to determine the intervention’s influence on the improvement of ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy.’ High scores were found in both groups, nonetheless greater in EG. The nurse home visiting in the postpartum period has a potential strategy to promote women's postnatal health (Handler et al., 2019) and their families. So, the BCP Intervention Program with face-to-face interactive health education sessions and proactive support by the nurse, during nurse home visiting, seems to have improved perceived women’s breastfeeding self‑efficacy and support breastfeeding successfully since being discharged from Maternity up to 120 days postpartum when compared with conventional care. According to the randomized controlled trial of Vakilian et al. (2020), continuous breastfeeding education at home enables lactating women to access the educational content and resolve their breastfeeding‑related problems in the stress‑free environment of their home and at any time convenient. However, the educational interventions cannot be effective unless they improve the women’s perceptions of their abilities (Otsuka et al., 2014; Vakilian et al., 2020). Therefore, breastfeeding education enhancing self‑efficacy can enhance women’s self‑confidence, and consequently, help them to maintain breastfeeding after childbirth and also continue breastfeeding for a longer period (Chipojola et al., 2020; Vakilian et al., 2020).

Duration, type, and the number of the health education sessions appeared to be associated with an improvement in perceived breastfeeding self-efficacy. Individualizing the care for lactating women requires an appropriate amount of time, rather than fixed and rigid rules: this allows to provide quality support encouraging acquiring skills, making the correct diagnosis of the situation, and establishing an adequate plan of care directed to the improvement of maternal self-efficacy (Colombo et al., 2018).

On the other hand, a health education session on the 15th day postpartum in the EG appeared to influence the improvement in the perceived women’s breastfeeding self‑efficacy, compared to conventional care. These results suggest, like the experimental studies of Wu et al. (2014) and Rodrigues et al. (2018) that interventions that include several sessions over time have an effect on women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy. The context (home) and the strategy of approach to the family (HV) appeared to influence the ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy’ and to acquire the necessary skills for successful breastfeeding of the woman (Vakilian et al., 2020). Simultaneously, the home environment facilitates the communication between professionals and the woman’s family, which leads to a widespread and proactive intervention (Perry et al., 2017; Vakilian et al., 2020).

In EG, the number of women in exclusive breastfeeding raised from eight to ten (when comparing the final evaluation with the initial findings), suggesting that the BCP intervention program has the potential to contribute to increasing breastfeeding exclusivity and favored the duration. This result is consistent with the findings reported by Wu et al. (2014) and Minharro et al. (2019), who state that breastfeeding self-efficacy affects the breastfeeding duration and exclusivity, and higher breastfeeding self-efficacy increases the probability of exclusive breastfeeding.

The reasons for stopping breastfeeding mentioned by the women in CG were already described in the literature (Colombo et al., 2018; Dagher et al., 2016; Magarey et al., 2016; Rozga et al., 2015) some of which are eligible for healthcare interventions, such as ‘Incorrect infant's attachment,’ ‘Flat nipples,’ ‘Infant crying,’ and ‘Maternal anxiety.’ Some of these factors were also seen in women of the EG; however, we were able to address them during the intervention plan. Evaluating, teaching, correcting, and training the infant's handling and exteriorization of the flat nipple improve the infant's adaptation to the breast, promoting an adequate attachment and efficient suction, with a consequent decrease in nipple pain, maternal anxiety, and woman-infant dyad dissatisfaction with breastfeeding. This approach may increase the duration and/or exclusivity of breastfeeding. Also, the perception of hypogalactia (low milk supply) is most often an incorrect maternal and familial perception, associated with cultural beliefs and myths about breastfeeding (Galipeau et al., 2018; Monte et al., 2013). Proximal intervention increases maternal competence for the correct evaluation of an infant's behavior (Wood et al., 2017).

In this study, women's satisfaction degree in both groups was high, showing that a good quality of care was provided. This finding shows that the therapeutic relationship between the nurse and the woman was not a barrier according to the type of intervention performed.

The first limitation relates due to the small sample size, and the number of dropouts that occurred hindered the pilot study and underpowered to determine the effectiveness of the BCP Intervention program. The time frame, the area covered for recruitment, and the proportion of women who declined to participate induced this limitation. Also, this project was not funded, so a choice was made, and the BCP intervention program was implemented in the FHU Santa Joana because it has the greatest potential in terms of the number of participants. Another limitation of this pilot study is based on the non-blind involvement (both from participants and nurses), which could cause bias. Finally, this study did not address the cost-effectiveness component, which is essential for the decision-making process.

It is expected that these findings provide empirical evidence to promote breastfeeding strategies in Portugal. However, future studies are necessary to warrant a larger and more rigorous, and blinded randomized controlled trial, to determine the effectiveness and feasibility of the BCP Intervention program, or in alternative pragmatic trials that could be fewer resources demanding. In addition to the BCP intervention program, could benefit introduce earlier supplemental interventions to improve woman’s breastfeeding self-efficacy in the prenatal and maternity period and to potentially reduce early breastfeeding abandonment.

Conclusion

The BCP intervention program, during the first 120 days postpartum, showed promissory results in improving the ‘perception of breastfeeding self-efficacy’ compared to conventional care, favoring breastfeeding duration and exclusivity, and cumulative breastfeeding competence of women/families, resulting in health gains for families.

The HV is an intervention strategy inherent to postpartum care and should not be limited to a single moment, because it allows early identification of reasons to stop breastfeeding that are amenable to healthcare interventions.

The BCP intervention program showed to be a personalized intervention to promote breastfeeding in the postpartum period, adequate to implement in the Family Health Units for follow-up, influencing lactating woman/father/family on the breastfeeding success, emphasizing that it contributes to ‘Breastfeeding Friendly’ Family Health Units. The results of this pilot study may prove useful for policymakers and clinicians, in terms of considering introducing home visit programs in the postpartum period in addition to the current standard care.

Abbreviations

- %:

-

Percentage

- BCP:

-

Breastfeed care plus

- BSES-SF:

-

Breastfeeding self-efficacy scale—short form

- CG:

-

Control group

- CHA:

-

Children health appointment

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EG:

-

Experimental group

- FHU:

-

Family health unit

- HV:

-

Home visit

- M1, M2, M3:

-

Initial evaluation, intermedium assessment, the final assessment

- min.:

-

Minutes

- n:

-

Number of participants

- p :

-

Probability value or significance.

- sd:

-

Standard deviation

- y:

-

Years

References

Amaro, F. (2001). A classificação das famílias segundo a escala de Graffar. Fundação Nossa Senhora do Bom Sucesso.

Benahmed, N., San Miguel, L., Devos, C., Fairon, N., & Christiaens, W. (2017). Vaginal delivery: How does early hospital discharge affect mother and child outcomes? A systematic literature review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1465-7

Bosi, A. T. B., Eriksen, K. G., Sobko, T., Wijnhoven, T. M., & Breda, J. (2016). Breastfeeding practices and policies in WHO European Region Member States. Public Health Nutrition, 19(4), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001767

Brockway, M., Benzies, K., & Hayden, K. A. (2017). Interventions to improve breastfeeding self-efficacy and resultant breastfeeding rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Human Lactation, 33(3), 486–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334417707957

Busch, D. W., Logan, K., & Wilkinson, A. (2014). Clinical practice breastfeeding recommendations for primary care: Applying a tri-core breastfeeding conceptual model. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 28(6), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.02.007

Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (1989). The changing family life-cycle: A framework to family therapy (2nd ed.). Gardner Press.

Cattaneo, A., Yngve, A., Koletzko, B., & Guzman, L. R. (2005). Protection, promotion and support of breast-feeding in Europe: Current situation. Public Health Nutrition, 8(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004660

Chipojola, R., Chiu, H. Y., Huda, M. H., Lin, Y. M., & Kuo, S. Y. (2020). Effectiveness of theory-based educational interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 109, 103675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103675

Colombo, L., Consonni, D., Bettinelli, M. E., & Mauri, P. A. (2018). Breastfeeding determinants in healthy term newborns. Nutrients, 10(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010048

Dagher, R. K., Mcgovern, P. M., Schold, J. D., & Randall, X. J. (2016). Determinants of breastfeeding initiation and cessation among employed mothers: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16, 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0965-1

Dennis, C. L. (1999). Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: A self-efficacy framework. Journal of Human Lactation, 15(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/089033449901500303

Dennis, C. (2003). The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 32(6), 734–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884217503258459

DGS. (2014). Registo do Aleitamento Materno: Relatório janeiro a dezembro 2013. Retrieved from, https://www.dgs.pt/documentos-e-publicacoes/iv-relatorio-com-os-dados-do-registo-do-aleitamento-materno-2013-pdf.aspx

DGS. (2015). Programa Nacional para a Vigilância da Gravidez de Baixo Risco (Direção-Geral da Saúde (ed.)). Retrieved from https://www.dgs.pt/em-destaque/programa-nacional-para-a-vigilancia-da-gravidez-de-baixo-risco-pdf11.aspx

Economou, M., Kolokotroni, O., Paphiti, I., Cyprus, D., Hadjigeorgiou, E., Hadjiona, V., & Middleton, N. (2021). The association of breastfeeding self-efficacy with breastfeeding duration and exclusivity: Assessment of the psychometric properties of the Greek version of the BSES-SF tool. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-48028/v1

Ferreira, T. D. M., Piccioni, L. D., Queiroz, P. H. B., Silva, E. M., & do Vale, I. N. (2018). Influence of grandmothers on exclusive breastfeeding: Cross-sectional study. Einstein, 16(4), eAO4293. https://doi.org/10.31744/einstein_journal/2018AO4293

Galipeau, R., Baillot, A., Trottier, A., & Lemire, L. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and perceived insufficient milk supply: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 14(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12607

Gillath, O., Karantzas, G. C., & Fraley, R. C. (2016). Chapter 6—How stable are attachment styles in adulthood? Adult attachment: A concise introduction to theory and research (1st ed., p. 140). Academic Press.

Handler, A., Zimmermann, K., Dominik, B., & Garland, C. E. (2019). Universal early home visiting: A strategy for reaching all postpartum women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(10), 1414–1423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02794-5

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A.-W., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348, 10–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

Kislaya, I., Braz, P., Dias, C. M., & Loureiro, I. (2020). Trends in breastfeeding rates in Portugal: Results from five national health interview surveys. European Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa166.963

Lau, C. Y. K., Lok, K. Y. W., & Tarrant, M. (2018). Breastfeeding duration and the theory of planned behavior and breastfeeding self-efficacy framework: A systematic review of observational studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2453-x

Levy, L., & Bértolo, H. (2012). Manual de Aleitamento Materno (Comité Português para a UNICEF & Comissão Nacional Iniciativa Hospitais Amigos dos Bebés (ed.); 1.a edição). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.pt/media/1581/6-manual-do-aleitamento-materno.pdf

Magarey, A., Kavian, F., Scott, J. A., Markow, K., & Daniels, L. (2016). Feeding mode of Australian infants in the first 12 months of life: An assessment against national breastfeeding indicators. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(4), NP95–NP104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415605835

Maleki, A., Faghihzadeh, E., & Youseflu, S. (2021). The effect of educational intervention on improvement of breastfeeding self-efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2021, 5522229. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5522229

Minharro, M. C. D. O., Carvalhaes, M. A. D. B. L., Cristina, M. G. D. L. P., & Ferrari, A. P. (2019). Breastfeeding self-efficacy and its relationship with breasfeeding duration. Cogitare Enfermagem, 24, e57490. https://doi.org/10.5380/ce.v24i0.57490

Monte, G. C. S. B., Leal, L. P., & Pontes, C. M. (2013). Social support networks for breastfeeding women. Cogitare Enfermagem, 18(1), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.5380/ce.v18i1.31321

Negin, J., Coffman, J., Vizintin, P., & Raynes-Greenow, C. (2016). The influence of grandmothers on breastfeeding rates: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0880-5

Otsuka, K., Taguri, M., Dennis, C.-L., Wakutani, K., Awano, M., Yamaguchi, T., & Jimba, M. (2014). Effectiveness of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention: Do hospital practices make a difference ? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(1), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1265-2

Perry, S., Hockenberry, M., Lowdermilk, D., Wilson, D., Keenan-Lindsay, L., & Sams, C. (2017). Maternal child nursing care in Canada (2nd ed.). New York: Elsevier.

Prates, L. A., Schmalfuss, J. M., & Lipinski, J. M. (2015). Social support network of post-partum mothers in the practice of breastfeeding. Escola Anna Nery, 19(2), 310–315. https://doi.org/10.5935/1414-8145.20150042

Rodrigues, A., Dodt, R., Oriá, M., César de Almeida, P., Padoin, S., & Barbosa Ximenes, L. (2018). Promoção da autoeficácia em amamentar por meio de sessão educativa grupal: ensaio clínico randomizado. Texto & Contexto, 26(4), e1220017. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072017001220017

Rozga, M. R., Kerver, J. M., & Olson, B. H. (2015). Self-reported reasons for breastfeeding cessation among low-income women enrolled in a peer counseling breastfeeding support program. Journal of Human Lactation, 31(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334414548070

Santos, V., & Bárcia, S. (2009). Contributo para a adaptação transcultural e validação da “Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form”-versão portuguesa. Revista Portuguesa De Clinica Geral, 25, 363–369. https://doi.org/10.32385/rpmgf.v25i3.10633

Smilkstein, G., Ashworth, C., & Montano, D. (1982). Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. Journal of Family Practice, 15(2), 303–311.

Tseng, J. F., Chen, S. R., Au, H. K., Chipojola, R., Lee, G. T., Lee, P. H., Shyu, M. L., & Kuo, S. Y. (2020). Effectiveness of an integrated breastfeeding education program to improve self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding rate: A single-blind, randomised controlled study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 111, 103770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103770

Vakilian, K., Farahani, O. C. T., & Heidari, T. (2020). Enhancing breastfeeding—home-based education on self-efficacy: A preventive strategy. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 11, 63. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_494_17

Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J. D., França, G. V. A., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., Murch, S., Sanka, M. J., Walker, N., & Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

Webber, E., & Serowoky, M. (2017). Breastfeeding curricular content of family nurse practitioner programs. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 31(2), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.07.006

WHA. (2016). Sixty-ninth World Health assembly. United Nations decade of action on nutrition (2016–2025)—WHA69.8. 1–3. Retrieved https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_R8-en.pdf

WHO. (2014). Postnatal care of the mother and newborn 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization.

WHO, UNICEF. (2008). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part 1 definitions. Geneva: World Health Organization.

WHO & UNICEF. (2014). Global nutrition targets 2025: breastfeeding policy brief. 1–7.

Wood, N. K., Sanders, E. A., Lewis, F. M., Woods, N. F., & Blackburn, S. T. (2017). Pilot test of a home-based program to prevent perceived insufficient milk. Women and Birth Journal, 30, 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.04.006

Wu, D. S., Hu, J., McCoy, T. P., & Efird, J. T. (2014). The effects of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention on short-term breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous mothers in Wuhan, China. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(8), 1867–1879. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12349

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the nursing teams of the FHU Santa Joana and FHU Atlântico Norte for their active participation and collaboration in data collection, and the women/families for their collaboration and receptivity in the development of this pilot study.

Funding

This pilot study was no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the manuscript as follows: study conception and design: ARP, JJA; data collection: ARP; analysis and interpretation of results: ARP, JJA; draft manuscript preparation: ARP, JJA, EMM; subsequent manuscript revisions: EMM. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The pilot study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre Regional Health Administration (28NOV’2017:88/2017).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all women participants.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pádua, A.R., Melo, E.M. & Alvarelhão, J.J. An Intervention Program Based on Regular Home Visits for Improving Maternal Breastfeeding Self-efficacy: A Pilot Study in Portugal. Matern Child Health J 26, 575–586 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03361-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03361-7