Abstract

Objectives To explore factors that shape decisions made regarding employee benefits and compare the decision-making process for workplace breastfeeding support to that of other benefits. Methods Sixteen semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with Human Resource Managers (HRMs) who had previously participated in a breastfeeding-support survey. A priori codes were used, which were based on a theoretical model informed by organizational behavior theories, followed by grounded codes from emergent themes. Results The major themes that emerged from analysis of the interviews included: (1) HRMs’ primary concern was meeting the needs of their employees, regardless of type of benefit; (2) offering general benefits standard for the majority of employees (e.g. health insurance) was viewed as essential to recruitment and retention, whereas breastfeeding benefits were viewed as discretionary; (3) providing additional breastfeeding supports (versus only the supports mandated by the Affordable Care Act) was strongly influenced by HRMs’ perception of employee need. Conclusions for Practice Advocates for improved workplace breastfeeding-support benefits should focus on HRMs’ perception of employee need. To achieve this, advocates could encourage HRMs to perform objective breastfeeding-support needs assessments and highlight how breastfeeding support benefits all employees (e.g., reduced absenteeism and enhanced productivity of breastfeeding employee). Additionally, framing breastfeeding-support benefits in terms of their impact on recruitment and retention could be effective in improving adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

Additional breastfeeding-support benefits beyond those mandated in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) could improve breastfeeding rates, but few companies provide additional supports. Better understanding of how Human Resource Managers (HRM) decide on overall employee benefits versus breastfeeding-support benefits is crucial for gaining inclusion of more supports. Interviews revealed HRMs’ perception of employee need for breastfeeding-support benefits influenced levels of support offered. For many HRMs, breastfeeding-support benefits met the needs of few employees and did not contribute to recruitment or retention, therefore few supports were offered. By contrast, HRMs who perceived breastfeeding-support needs as high provided additional benefits beyond the ACA mandate.

Introduction

Breastfeeding is beneficial for maternal and infant health. Extensive research demonstrates significant breastfeeding benefits as well as risks associated with early weaning and formula feeding. Infants who are not breastfed have an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, infection, overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (Victora et al. 2016). For women, breastfeeding helps with birth spacing and reduces the risk of some cancers (Victora et al. 2016). The detriment to society of suboptimal breastfeeding are striking: a previous study predicts annual deaths associated with suboptimal breastfeeding total 3340 (78% being maternal) and medical costs total $3.0 billion in the United States (Bartick et al. 2017).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP 2012) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for about 6 months and continued breastfeeding with complementary foods for 1 year or longer as mutually desired by mother and infant. Breastfeeding rates have improved in the US: 83% of mothers initiate and 36% continue to 12 months, surpassing Healthy People objectives of 82% and 34%, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2016). However, at 6 months, exclusive (25%) or any breastfeeding (58%) remains just below target (26% and 61%, respectively), indicating more support is needed (CDC 2016).

There are many barriers to breastfeeding stemming from individual, socioeconomic, cultural, and institutional factors (Rollins et al. 2016). Return-to-work is highly influential in not initiating or discontinuing breastfeeding early (Brown et al. 2014). Compared to non-working breastfeeding women, working full-time is associated with a significant decline in breastfeeding duration, indicating that the workplace may not be conducive to breastfeeding continuation (Mandal et al. 2010). Addressing the impact of return-to-work on breastfeeding is important as 56.8% of all women were workforce participants in 2016 and 61.8% of these women had a child less than 3 years old (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2016).

The provision of breastfeeding-support benefits upon return to work has been associated with longer breastfeeding duration (Kozhimannil et al. 2016). Additionally, company-sponsored lactation programs can lead to improved breastfeeding rates (Spatz et al. 2014). Supporting breastfeeding also benefits the employer as breastfeeding reduces absenteeism rates and improves employee retention, perhaps because increased perception of breastfeeding support is associated with job satisfaction (Cohen and Mrtek 1994; Cohen et al. 1995; Waite and Christakis 2015).

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated that employers with more than 50 employees provide a non-restroom space and unpaid break time for hourly breastfeeding employees to express milk (US Goverment 2010). Though some evidence suggests the ACA mandate is associated with improved breastfeeding rates, its impact is not yet clear (Gurley-Calvez et al. 2018). Additionally, access to these accommodations remains challenging, and many employers reported unawareness of the mandate years after its instatement (Alb et al. 2017). Research indicates that other factors (e.g., availability of lactation amenities, like breast pumps, or a supportive workplace environment) are significant predictors of breastfeeding duration, suggesting supports beyond breaks and designated spaces are needed to sustain breastfeeding among employed women (Bai and Wunderlich 2013).

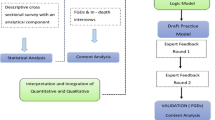

This study was informed by a theoretical model developed using three organizational behavior theories: institutional theory, resource dependence theory, and strategic management theory (Fig. 1). Institutional theory examines the pressures that wider environments exert on organization processes like benefit adoption (Scott 2005). Resource dependence theory suggests that benefit decisions are driven by employee acquisition and retention but balanced with organizational resources (Barringer and Milkovich 1998). Finally, strategic management theory suggests benefits most important to managers and that align with the organizational mission and values are more likely to be adopted (Goodstein 1994). The theoretical model developed for this study proposes that human resource decisions regarding employee benefit offerings are primarily influenced by two factors: (1) external pressure and (2) internal demands and resources. Those influences are moderated by strategic management activities, subsequently affecting decisions regarding benefits.

To date, research is lacking as to why some companies provide several supports for breastfeeding employees whereas others offer the minimum. Human Resource Mangers (HRMs) are key players in electing employee workplace benefits. Therefore, gaining an understanding of how HRMs determine which workplace breastfeeding support to provide is crucial in persuading companies to offer sufficient supports for women to sustain breastfeeding while employed. The purpose of this study is to explore factors that influence employee benefits and compare the decision-making process for workplace breastfeeding support to that of other benefits.

Methods

Sample

We selected HRMs from companies that participated in a pilot study to develop an instrument that assessed company support (Hojnacki et al. 2012) and purposively sampled to include HRMs from companies with a range of breastfeeding-support benefits. Additional company characteristics appear in Table 1. We contacted HRMs by phone and email and invited them to participate in an interview about workplace breastfeeding support. We then scheduled an interview with HRMs interested in participating.

The Michigan State University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Collection

The second author, T.B., conducted 16 semi-structured in-depth interviews between August and November 2011 at company sites across Michigan. Michigan does not have state-level laws on workplace breastfeeding rights, therefore, they must follow the ACA mandate. The interviews took place in private offices or conference rooms and lasted 26–67 min (\({\bar{\text{x}}}\) = 50.78; s = 11.73).

T.B. obtained informed consent and asked participants to complete a demographic questionnaire. Each session was audio-recorded. One moderator T.B., trained in qualitative research through graduate coursework, conducted all interviews and took notes of the discussion. The notes served to facilitate transcription. A professional transcriber transcribed audio recordings. We checked transcripts for accuracy using original recordings. To maintain confidentiality, T.B. conducted discussions in a private space and we de-identified all transcripts.

We organized the interview guide (Online Resource 1) into two major topics: (1) processes involved in company decisions on offering employee benefits and (2) how the processes to offer employee benefits compared to company decisions regarding breastfeeding support. Questions that explored each of the major topics were informed by the theoretical model described previously (Fig. 1). Open-ended questions and probing techniques were used, ensuring all relevant topics were explored. Experts in qualitative research, breastfeeding support, and human resource management and HRMs reviewed the interview guide to obtain content validity and we evaluated face validity through a small pilot with three HRMs. Both led to only small changes to wording.

Data Analysis

We performed a content analysis following a protocol established by Richards (2014) using NVivo analysis software, version 10 (NVivo qualitative data analysis software2012) to manage the data. Following the protocol, first, team members read transcripts thoroughly to facilitate immersion into the data and annotated to aid reflection. We then coded interviews broadly using topic codes derived a priori from the framework described previously (Fig. 1). We created analytical codes, or codes that come from interpretation and reflection on the meaning within the data, both within and outside the framework-derived topic codes. The first author, A.M.U., trained through relevant graduate coursework, and a student researcher K.W. (3rd author), trained by A.M.U. coded independently. Both researchers discussed the resulting codes until they reached consensus. A.M.U. and K.W. discussed power balances prior to reviewing codes and considered this during the analysis process to avoid biasing the consensus process. Both researchers created memos to reflect on analytical codes before and during consensus process and, as analytical coding proceeded, combined or separated categories to further develop emerging patterns and uncover subtler meanings within the data. The final coding structure appears in Table 2. We continually developed graphical models, to visualize associations between codes or emerging patterns and help determine themes.

We included 13 interviews in the analysis. We eliminated two interviews due to failures in recording and another because the participant was not an HRM and was not familiar with how employee-benefit decisions were made. For one interview two individuals attended, the HRM and the Payroll and Benefits Coordinator. We considered methodological differences between one-on-one interviews and group discussions, but because the Payroll and Benefits Coordinator contributed minimally to the conversation and consistently agreed with the HRM, it was included in the analysis.

After transcribing all interviews, we detected data saturation at interview 11, when redundancy of major themes had occurred. This is in agreement with empirical evidence that indicates that 80 to 92% of concepts are uncovered within the first ten interviews (Morgan 2002). Therefore, we deemed 13 interviews adequate for saturation.

We took a reflective approach by considering how team members’ professional backgrounds, experiences, and prior assumptions and the participants’ professional background and wider social context might influence how interviews were conducted and analyzed. A.M.U. and T.B. are Registered Dietitians, hold Masters degrees, are female, and were doctoral students when the interviews were conducted. K.W. was a dietetics undergraduate student when interviews were analyzed. A.M.U., T.B., and K.W. had no experience in human resource management, aside from reading relevant scientific literature, and all worked in a laboratory focused on breastfeeding-support research. Experience in breastfeeding advocacy and as nutrition professionals or students may have generated partiality among the authors in the prioritization of breastfeeding support benefits in the workplace. We considered this influence on the analysis process through memos and discussion of bias with the research team.

We had established relationships with the companies from which HRMs were selected through previous research work (Hojnacki et al. 2012). The participants were aware that the conversation would focus on their experience making decisions on employee-benefit provisions and what factors might influence these decisions. Prior to each interview, the moderator emphasized valuing participants’ experiences and views and refrained from expressing opinions during the interviews.

We established trustworthiness through analyst triangulation, executed through (1) independent analysis of all interviews by a second coder and (2) in-depth discussion of the themes and ideas from each interview and the final resulting themes among team members.

We analyzed demographic questionnaire data using descriptive statistics.

Results

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 3. Analysis revealed three major themes: (a) HRMs’ primary concern was meeting the needs of their employees, regardless of the benefit; (b) general employee benefits were viewed as essential to recruitment and retention whereas breastfeeding-support benefits were discretionary; (c) HRMs’ perception of employees’ breastfeeding-support needs was related to the breastfeeding-support benefits offered. Exemplary quotes appear in Table 4. How results relate to theoretical framework are presented in Fig. 2.

Meeting Employee Needs Primary Concern

Internal demands were often an impetus for offering benefits. Specifically, participants wanted to meet employee needs regardless of benefit type. If participants recognized that many employees needed a particular benefit, they indicated they would make an effort to provide it (Table 4, Quote 1). Likewise, breastfeeding support was often provided because participants wanted to meet employee needs and not because the company was advocating for breastfeeding in particular (Table 4, Quote 2). Participants shared that no or few employees ever asked for breastfeeding support, indicating low internal demand.

Meeting employee needs through benefits, as many participants shared, aligned with companies’ missions and visions as it was a way to show that the company cared for its employees and its employees’ health (Table 4, Quote 3). Participants shared that offering benefits was a balance between employee demands and the company’s budget (Table 4, Quote 4). However, participants felt confident they could provide the best benefits within their company’s budgetary constraints.

Employee Benefits Essential, Breastfeeding Support Discretionary

General employee benefits were viewed as essential to the recruitment and retention of employees (Table 4, Quote 5), once again, illustrating that internal demands were a prominent motivator for offering benefits. Participants indicated that employees expected to receive general benefits, like healthcare insurance and dental insurance, contributing to their essentiality. Participants shared that recruitment and retention was important because companies extensively trained employees or sought highly skilled individuals and, therefore, had to compete for talent (Table 4, Quote 6). For this reason, participants often reported “benchmarking”, or comparing their general benefits to other similar companies, a form of external pressure. Additionally, agents or consultants and professional organizations, like the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), were often-noted sources of information on general benefits, another form of external pressure.

Breastfeeding support, on its own, was viewed as a discretionary benefit. External and internal pressure were often low for breastfeeding-support benefits as participants indicated that this might help companies stand out from others, but were not essential to recruitment and retention (Table 4, Quote 7 and 8). Additionally, participants described offering this benefit as going “above and beyond” what was expected. Only a few participants communicated that breastfeeding support could help retain existing employees (Table 4, Quote 9).

Participants emphasized that breastfeeding-support benefits had to be part of a larger “family-friendly” benefits package rather than a stand-alone benefit so it would appeal to more employees (Table 4, Quote 10). Participants did not benchmark and agents/consultants did not offer information on breastfeeding support, again illustrating low external pressure. Additionally, few participants recalled information regarding breastfeeding support or the ACA breastfeeding mandate in SHRM communications. Those who saw this information indicated it had little publicity or discussion.

Perceived Need Related to Breastfeeding Supports Offered

The ACA, an external pressure, increased awareness of breastfeeding support among participants and drove compliance with the law’s requirements. However, internal demand influenced the degree of support offered. Namely, participants’ interpretation of employee need influenced breastfeeding-support benefits offered beyond the ACA requirements. Participants used language suggesting that their assessment of breastfeeding-support needs was mainly subjective: participants prefaced statement indicating they were unsure or used phrases like “might be” or “never gotten the impression”, indicating uncertainty.

Some participants perceived internal demands for breastfeeding-support as low among employees. In addition to perceiving low demand, those unfamiliar with the ACA breastfeeding mandate reported never having offered breastfeeding-support benefits (Table 4, Quote 11). Additionally, one participant expressed not seeing the value of breastfeeding benefits to employees. Participants who interpreted that breastfeeding needs were low and were aware of the ACA breastfeeding mandate reported only working towards compliance with the mandate (Table 4, Quote 12). The ACA also affected the requirements of many benefits unrelated to breastfeeding support. Therefore, participants reported targeting only the minimum requirements of the ACA breastfeeding mandate since there were many other requirements to meet under this law.

Participants who perceived a high internal demand for breastfeeding benefits reported providing benefits beyond the ACA breastfeeding mandate. In some cases, the ACA made participants aware of breastfeeding-support needs and, if participants perceived it to be of high need to employees, more breastfeeding supports than the ACA mandated were offered (Table 4, Quote 13). Additionally, all participants who expressed that breastfeeding benefits were valuable, a strategic management activity, worked in companies that offered benefits beyond the ACA mandate. Participants who recognized the value of breastfeeding support shared comments about the health-related importance of breastfeeding and/or the benefits to the organization of offering breastfeeding support (Table 4, Quote 14). Participants who had experience breastfeeding or had partners who breastfed, another strategic management activity, often communicated the importance to support breastfeeding in the workplace and worked in companies that offered additional breastfeeding support (Table 4, Quote 15).

Discussion

Internal demand appeared strongly influential in participants’ decision regarding breastfeeding-support benefits (Fig. 2). Specifically, participants’ interpretation of employees’ need influenced the degree of support offered. Many participants perceived that needs were low, as corroborated by previous research with organizational representatives (Dunn et al. 2004). This corresponded with either never having offered breastfeeding support or, if the company was aware of the ACA breastfeeding mandate, an external pressure, only compliance. Breastfeeding-support benefits, often times, are needed by a small subgroup of employees for relatively short time periods. This could give HRMs the impression that internal demand is low, leading to insufficient availability of support despite its essentiality for breastfeeding continuation upon return to work (Dinour and Szaro 2017). Additionally, most participants assessed breastfeeding-support needs subjectively, which could be influenced by strategic management activities, like HRMs’ value of breastfeeding or prior personal experience (DiTomaso et al. 2007). This emphasizes the importance of objective assessments of employee breastfeeding-support needs and recognition among HRMs of how critical breastfeeding support is for the short time mothers need it.

Several participants reported no or few employees asking for breastfeeding support, thus perceiving low internal demand. This may indicate HRMs rely on employees to start conversations, perhaps attributed to their own discomfort or unawareness in discussing breastfeeding accommodations, as highlighted by previous research (Anderson et al. 2015). Relying on employees to advocate is a questionable practice since they may not be voicing their breastfeeding-support needs. This is known as “employee silence”: employees are uncomfortable raising important issues with employers, often in fear of negative consequences (Milliken et al. 2003). Pregnant employees may engage in “employee silence” to avoid uncomfortable conversations with employers or because they are unaware of their employee rights. This lack of communication could lead mothers to believe their work is unsupportive of breastfeeding, reducing breastfeeding duration (Sattari et al. 2013).

Participants who perceived internal demand for breastfeeding support as high offered benefits beyond those mandated by the ACA. Considering participants’ desire to meet employee needs, going beyond the ACA highlights that mothers may require more workplace breastfeeding accommodations than those outlined in the mandate. Indeed, lactation space and breaks have not been consistently associated with breastfeeding duration (Hilliard 2017). Additional accommodations (e.g., corporate lactation program, on-site child care, and access to a lactation consultant) may be needed to successfully balance breastfeeding and work (Hilliard 2017). However, in 2017, SHRM reported only 8% of companies offered lactation support services, such as lactation consulting and education (Society for Human Resource Management 2017).

This research is unique because the interviews occurred when there was heightened awareness of breastfeeding-support benefits as the ACA had recently become law. Though we did not focus on the ACA’s impact on breastfeeding-support benefits, the results offer insights into the ACA’s role in the decision-making process. The ACA, an external pressure, increased awareness of workplace breastfeeding accommodations (Fig. 2). In some cases, the ACA encouraged assessment of breastfeeding-support needs leading to supports beyond ACA requirements if participants perceived a high demand. However, the external pressure the ACA exerted was often limited. For several participants, the ACA resulted in only compliance, rather than inspiring additional support of breastfeeding employees more likely to impact breastfeeding rates (Hilliard 2017). Other external pressures were not apparently influential in decisions regarding breastfeeding-support benefits. This is often seen when a behavior, like breastfeeding, is not yet an accepted part of institutional culture (Tolbert and Zucker 1996).

Participants viewed general benefits as meeting employee needs and essential to recruitment and retention, reflecting high internal demand (Fig. 2). In contrast, breastfeeding-support benefits were viewed as discretionary, having little influence on recruitment or retention. This indicated that internal demands played a role when providing general benefits, but not for breastfeeding-support benefits. Contrary to participants’ perception, employee retention rates are markedly higher for companies with corporate lactation programs (94.2% retention compared to national average of 59%; USDHHS 2008). Better communication of improved retention may persuade HRMs to adopt these benefits.

Limitations

The sample, composed of primarily White females, may be viewed as a limitation. Though this resembles national demographics for the HRM field, views from individuals of differing demographic characteristics deserve further exploration (“US Census Bureau” 2016). Though HRMs from companies with varying breastfeeding accommodations were interviewed, the sample was limited to one state. The findings may diverge in other states that abide to different state laws and local breastfeeding cultures. Finally, participants, acting as company representatives, may have felt compelled to speak positively about their company, possibly leading to an overly favorable depiction of benefit provisions. Encouraging participants to share all their experiences, both positive and negative, and reminding participants that reported results would be de-identified may have mitigated this issue.

Future Directions

These findings can inform future research on adoption of breastfeeding support benefits by HRMs. Framing messaging for HRMs on breastfeeding support benefits in the context of meeting employee needs and improving recruitment and retention may increase adoption, though more research on the impact of breastfeeding-support benefits on recruitment and retention is needed. HRMs may benefit from training on discussing breastfeeding-support needs with employees; future work on the influence of this training on HRMs’ perception of breastfeeding-support needs and benefit provision would be valuable. Additionally, encouraging HRMs to perform objective assessments of employees’ needs for breastfeeding accommodations and exploring its impact on benefit provision is warranted. Continued exploration of how the ACA and additional state laws influence breastfeeding-support benefits is needed, especially considering the recent political debates that makes the ACA’s future uncertain.

Conclusion

Internal demands and resources and external pressures influenced general benefits offered. Participants judged the essentiality of general benefits in terms of: (1) meeting employee needs and (2) impact on recruitment and retention. For many participants, breastfeeding benefits were assumed to meet the need of few employees and had little to no impact on recruitment or retention; therefore, they were often considered discretionary benefits. External pressures, namely the ACA, played a strong role in offering breastfeeding-support benefits that complied with the mandate, but internal demand (participants’ perception of employees’ need) and strategic management activities (participants’ value of breastfeeding and previous experience with breastfeeding) influenced the level of support offered. Taken together, framing breastfeeding-support benefits in a context that is important for HRMs may positively influence adoption of these workplace benefits. This could require an objective assessment of their employees’ need for breastfeeding support, communication of how breastfeeding-support benefits impact recruitment and retention, and the importance of breastfeeding-support benefits for the breastfeeding employee and for the company.

References

Alb, C. H., Theall, K., Jacobs, M. B., & Bales, A. (2017). Awareness of United States’ Law for nursing mothers among employers in New Orleans, Louisiana. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 27(1), 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.10.009.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2012/02/22/peds.2011-3552.

American Factfinder. (2016). Retrieved May 7, 2018, from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

Anderson, J., Kuehl, R. A., Drury, S. A. M., Tschetter, L., Schwaegerl, M., Hildreth, M., et al. (2015). Policies aren’t enough: The importance of interpersonal communication about workplace breastfeeding support. Journal of Human Lactation, 31(2), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415570059.

Bai, Y., & Wunderlich, S. M. (2013). Lactation accommodation in the workplace and duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 58(6), 690–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12072.

Barringer, M. W., & Milkovich, G. T. (1998). A theoretical exploration of the adoption and design of flexible benefit plans: A case of human resource innovation. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 305–324.

Bartick, M. C., Schwarz, E. B., Green, B. D., Jegier, B. J., Reinhold, A. G., Colaizy, T. T., et al. (2017). Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(1), e12366.

Brown, C. R., Dodds, L., Legge, A., Bryanton, J., & Semenic, S. (2014). Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 105(3), e179–e185.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Breastfeeding report card: Progressing toward national breastfeeding goals. Retrieved June 7, 2018, from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm.

Cohen, R., & Mrtek, M. B. (1994). The impact of two corporate lactation programs on the incidence and duration of breast-feeding by employed mothers. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 8(6), 436–441.

Cohen, R., Mrtek, M. B., & Mrtek, R. G. (1995). Comparison of maternal absenteeism and infant illness rates among breast-feeding and formula-feeding women in two corporations. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 10(2), 148–153.

Dinour, L. M., & Szaro, J. M. (2017). Employer-based programs to support breastfeeding among working mothers: A systematic review. Breastfeeding Medicine, 12(3), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2016.0182.

DiTomaso, N., Post, C., & Parks-Yancy, R. (2007). Workforce diversity and inequality: Power, status, and numbers. Annual Review of Sociology, 33(1), 473–501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131805.

Dunn, B. F., Zavela, K. J., Cline, A. D., & Cost, P. A. (2004). Breastfeeding practices in Colorado businesses. Journal of Human Lactation, 20(2), 170–177.

Goodstein, J. D. (1994). Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness: Employer involvement in work-family issues. Academy of Management Journal, 37(2), 350–382. https://doi.org/10.5465/256833.

Gurley-Calvez, T., Bullinger, L., & Kapinos, K. A. (2018). Effect of the Affordable Care Act on breastfeeding outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 108(2), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304108.

Hilliard, E. D. (2017). A review of worksite lactation accommodations: Occupational health professionals can assure success. Workplace Health & Safety, 65(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916666547.

Hojnacki, S. E., Bolton, T., Fulmer, I. S., & Olson, B. H. (2012). Development and piloting of an instrument that measures company support for breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 28(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334411430666.

Kozhimannil, K. B., Jou, J., Gjerdingen, D. K., & McGovern, P. M. (2016). Access to workplace accommodations to support breastfeeding after passage of the Affordable Care Act. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 26(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.002.

Mandal, B., Roe, B. E., & Fein, S. B. (2010). The differential effects of full-time and part-time work status on breastfeeding. Health Policy, 97(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.006.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476.

Morgan, M. G. (2002). Risk communication: A mental models approach. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

NVivo qualitative data analysis software. (2012). (version 10). QSR International Pty Ltd.

Richards, L. (2014). Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. Sage. Retrieved August 22, 2017, from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CR-JCwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=handling+qualitative+data+richards&ots=sri7lKxCxM&sig=0vpG6GIwilNSeALde0h2KWSWeNc.

Rollins, N. C., Bhandari, N., Hajeebhoy, N., Horton, S., Lutter, C. K., Martines, J. C., et al. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387(10017), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2.

Sattari, M., Serwint, J. R., Neal, D., Chen, S., & Levine, D. M. (2013). Work-place predictors of duration of breastfeeding among female physicians. The Journal of Pediatrics, 163(6), 1612–1617.

Scott, W. R. (2005). Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development, 37, 460–484.

Society for Human Resource Management. (2017). SHRM customized employee benefits prevalence benchmarking report. Retrieved May 7, 2018, from https://www.shrm.org/ResourcesAndTools/business-solutions/Documents/Benefits-Prevalence-Report-All-Industries-All-FTEs.pdf.

Spatz, D. L., Kim, G. S., & Froh, E. B. (2014). Outcomes of a hospital-based employee lactation program. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(10), 510–514. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0058.

The Business Case for Breastfeeding: Steps for Creating a Breastfeeding Friendly Worksite. (2008). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.womenshealth.gov/files/documents/bcfb_business-case-for-breastfeeding-for-business-managers.pdf.

Tolbert, P. S., & Zucker, L. G. (1996). The institutionalization of institutional theory. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies (pp. 175–190). London: Sage.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). 2016 Current Population Survey.

US Goverment. (2010). Patient protection and affordable care act, Pub. Law 111-148, as amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (HCERA), Pub. Law 111-152.

Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J. D., França, G. V. A., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., et al. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7.

Waite, W. M., & Christakis, D. (2015). Relationship of maternal perceptions of workplace breastfeeding support and job satisfaction. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(4), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0151.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all Human Resource Managers who participated for their valuable insight.

Funding

The authors disclose no financial support for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacMillan Uribe, A.L., Bolton, T.A., Woelky, K.R. et al. Exploring Human Resource Managers’ Decision-Making Process for Workplace Breastfeeding-Support Benefits Following the Passage of the Affordable Care Act. Matern Child Health J 23, 1348–1359 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02769-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02769-6