Abstract

Background The success of breastfeeding promotion is influenced by maternal factors. Therefore, it is vital to examine the influence of basic maternal demographic factors on breastfeeding practices. Objective To determine the influence of maternal socio-demographic factors on the initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding. Method A cross-sectional survey of mothers of children aged from 1 to 24 months attending a Nigerian Infant Welfare Clinic was conducted. Respondents were grouped according to age, parity, education, occupation, sites of antenatal care and delivery. These groups were compared for breastfeeding indices using bivariate and multivariate analysis. Results All the 262 respondents breastfed their children. The exclusive breastfeeding rate was 33.3% for children aged 0–3 months, 22.2% for children aged 4–6 months and 19.4% for children aged 7–24 months at the time of the study. Significantly higher proportions of mothers with at least secondary education, clinic-based antenatal care and delivery in health facilities initiated breastfeeding within 1 h of birth, avoided pre-lacteal feeding and practiced exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life. Maternal age and parity did not confer any advantage on breastfeeding practices. Delivery of children outside health facilities strongly contributed to delayed initiation of breastfeeding (P < 0.001), pre-lacteal feeding (P = 0.003) and failure to breastfeed exclusively (P = 0.049). Maternal education below secondary level strongly contributed to pre-lacteal feeding (P = 0.004) and failure to practice exclusive breastfeeding (P = 0.008). Conclusion Low maternal education and non-utilization of orthodox obstetric facilities impairs early initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The immense medical, social and economic benefits of breastfeeding children are well known. Breastfeeding offers significant protection against infections and diseases like bacterial meningitis, bacteraemia, necrotising enterocolitis, otitis media, urinary tract infection, diabetes, and obesity [5]. Prior to the introduction of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in 1991, the practice of breastfeeding declined substantially with resultant high childhood morbidities and mortality [25]. Thus, BFHI was aimed at promoting, protecting and supporting breastfeeding by modifying hospital practices which were inimical to good breastfeeding practices as a way of changing the orientation of hospital users about breastfeeding. Specifically, mothers should be assisted to commence breastfeeding within 30 min or at most an hour after birth and should be encouraged to breastfeed exclusively for the next 6 months.

The success of breastfeeding is dependent on its timely commencement and exclusive use for an optimal period as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO Expert Consultation on optimal duration of breastfeeding recommended exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life with the introduction of complementary foods and continued breastfeeding thereafter [23]. Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as “an infant’s consumption of human milk with no supplementation of any type (no water, no juice, no nonhuman milk, and no foods) except for vitamins, minerals, and medications [5]. Apart from ensuring that the infants have the best nutrition and adequate protection from infections and diseases, exclusive breastfeeding may increase the likelihood of continued breastfeeding for at least the first year of life” [5].

There is evidence that this initiative has successfully improved breastfeeding rate in most parts of the world [4, 7, 19]. However, there is still a need for further improvement in breastfeeding practices [24]. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding has been shown to vary in different parts of the world [1, 11, 20] In Nigeria, the exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months of age ranged from 23.4% in Ibadan [13] to 33.3% in Enugu [2] and 78.7% in Sokoto [16]. The former two reports were obtained from urban populations while the latter was obtained from a rural population. Although, breastfeeding has been reported to have improved in some developed countries like France [22], Switzerland [15], and Canada [21] since the introduction of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), the exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months in some of these places remains low. For instance, a Canadian report put the exclusive breastfeeding rate at 4 months of age at 4% and 0% at 6 months [14].

The variations have been related to prominent socio-economic and cultural factors which influence breastfeeding practices [10]. To minimize these variations, it is important to investigate maternal socio-demographic factors which may influence ability to initiate breastfeeding and breastfeed exclusively as recommended by WHO/UNICEF. Social factors like maternal education, occupation, family background and utilization of basic health services may affect breastfeeding practices [12, 20]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the influence of maternal socio-demographic factors on the initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding. This is aimed at improving the quality of breastfeeding practices particularly in resource-poor settings.

Patients and Methods

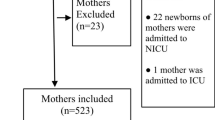

This cross-sectional survey was carried out between January 2005 and March 2005 at the Infant Welfare Clinic, Wesley Guild Hospital, Ilesa, Nigeria. The hospital which is a “Baby Friendly Facility” provides general and specialist maternity and paediatric care to the semi-urban and rural population of Osun, Ondo and Ekiti States of Nigeria. The Infant Welfare Clinic incorporates both the Well Child Clinic and the Paediatric General Out-Patient Clinic, hence both the sick and the healthy children of mothers in all socio-economic classes attend this clinic.

The subjects were consecutive nursing mothers of children aged 1–24 months who consented to participate in the study. The research tool was an open-ended questionnaire administered to the mothers by the researcher and assistants. Information gathered included the demographic characteristics of the mothers, their awareness of the Baby Friendly Initiative and the details of breastfeeding practices. The breastfeeding practices studied included the age of the child at the commencement of breastfeeding, pre-lacteal feeding and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life (for those aged 6 months or more) or at the time of interview (for those aged less than 6 months). For the purpose of this study, the onset of breastfeeding was considered delayed if it was commenced after 1 h of birth.

The mothers were classified into those who resided in rural and semi-urban places. They were also classified into two occupational groups: professionals (bankers, nurses, teachers, administrators and physicians) and others (traders, artisans, technicians, dress makers, farmers and students). Educational qualifications were also recorded as either high (tertiary, post-secondary, senior secondary) or low (junior secondary, primary and no formal education). For places of antenatal care and delivery, government-owned primary, secondary and tertiary health institutions and privately owned hospitals were classified as health facilities while churches, traditional birth homes and residential homes were classified together as others.

For this study, poor breastfeeding practices include delayed initiation of breastfeeding, use of pre-lacteal feeds and failure to breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months of life. Data were analysed with SPSS version 15.0 software using simple descriptive statistics. The mothers were grouped according to socio-demographic factors including age (≤20 and ≥21 years), parity group (primiparous and multiparous), educational qualification (high or low), occupation (professionals and the others), places of antenatal care (health facilities and the others) and places of delivery (health facilities and the others).

The prevalence of delayed initiation of breastfeeding and use of pre-lacteal feeds among all the respondents was determined and compared using bivariate analysis. However, for exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life, only the mothers of infants aged 7 months and above were studied using bivariate analysis since children who were less than 6 months at the time of the interview may not eventually be exclusively breastfed till the age of 6 months. Using means, standard deviation and Chi Square tests, the groups were compared for the indices of breastfeeding practices described above. Socio-demographic factors associated with poor breastfeeding practices were entered into a binary logistic regression model to determine their influences on poor breastfeeding practices defined above while controlling for the awareness of the subjects about the Baby Friendly Initiative. Significance was established when P values were less than 0.05 in two-tailed tests.

Results

Characteristics of Mothers and their Children

The 262 mothers were aged between 18 and 43 years with a mean age (±SD) of 29.3 ± 5.3 years. The children’s age also ranged between 1 and 24 months with a mean (±SD) of 11.7 ± 6.2 months. Sixty-six (25.2%) children were aged from birth to 6 months while 70 (26.7%), 82 (31.3%) and 44 (16.8%) were aged 7–12 months, 13–18 months and 19–24 months, respectively. The details of the socio-demographic data of the mothers are shown in Table 1.

Two hundred (76.3%) mothers had received counselling about breastfeeding according to the Baby Friendly Initiative. All the mothers practiced breastfeeding. Ninety-eight (37.4%) initiated breastfeeding within 1 h of birth and 96 (36.6%) practiced pre-lacteal feeding. Overall, 56 (21.4%) children were breastfed exclusively for 6 months or were still being breastfed exclusively at the time of the interview: 38 (19.4%) of 196 children who were aged 7–24 months were exclusively breastfed for 6 months while the exclusive breastfeeding rates for children aged 1–3 months and those aged 4–6 months were 33.3% (10/30) and 22.2% (8/36), respectively.

Maternal Domicile and Breastfeeding Practices

The proportions of children of semi-urban mothers and rural mothers who initiated breastfeeding within 1 h of life were similar [63 (35.0%) vs. 25 (30.5%); χ2 = 0.514, P = 0.473]. The rate of pre-lacteal feeding was higher among the semi-urban mothers but without significance [72 (40.0%) vs. 24 (29.3%); χ2 = 2.795, P = 0.095]. For children aged >6 months, the difference between the proportions of mothers in the comparison groups described above who breastfed exclusively for at least 6 months was insignificant [26/125 (20.8%) vs. 12/71 (16.9%); χ2 = 0.440; P = 0.507].

Maternal Age and Breastfeeding Practices

The proportions of children of mothers aged 20 years and below and those aged 21 years and above who initiated breastfeeding within 1 h of life were similar [4 (33.3%) vs. 94 (37.6%); χ2 = 0.00, P with Yate’s correction = 0.994]. The rate of pre-lacteal feeding was also similar in both groups [6 (50.0%) vs. 90 (36.0%); χ2 = 0.967, P = 0.3]. For children aged >6 months, the difference between the proportions of mothers in the comparison groups described above who breastfed exclusively for 6 months was insignificant [4 (33.3%) vs. 34 (18.5%); χ2 = 0.782; P with Yate’s correction = 0.376].

Maternal Parity and Breastfeeding Practices

The proportions of children of mothers who were primiparous and multiparous and initiated breastfeeding within 1 h of life were similar [30 (37.5%) vs. 68 (37.4%); χ2 = 0.000, P = 0.9]. The rate of pre-lacteal feeding was also similar in both groups [32 (40.0%) vs. 64 (35.2%); χ2 = 0.56, P = 0.4]. Similarly, for children aged >6 months, the difference between the proportions of mothers in the comparison groups described above who breastfed exclusively for 6 months were not remarkably different [11/72 (15.3%) vs. 27/124 (21.8%); χ2 = 1.23, P = 0.267].

Maternal Education and Breastfeeding Practices

A significantly higher proportion of highly educated mothers commenced breast feeding within 1 h of birth [80 (43.7%) vs. 18 (22.7%); χ2 = 10.325, P = 0.001]. A significantly lower proportion of highly educated mothers gave pre-lacteal feeds [57 (31.1%) vs. 39 (49.4%); χ2 = 7.89, P = 0.005]. For children aged >6 months, a higher proportion of highly educated mothers breastfed exclusively for 6 months compared to mothers with low education [33/139 (23.7%) vs. 5/57 (8.8%); χ2 = 5.796; P = 0.016].

Maternal Occupation and Breastfeeding Practices

The proportion of children of mothers who were professionals and the others who were commenced on breastfeeding within 1 h of birth were similar [26 (45.6%) vs. 72 (35.1%); χ2 = 2.097, P = 0.1]. While a significantly lower proportion of children of professionals had pre-lacteal feeding [12 (21.1%) vs. 84 (41.0%); χ2 = 7.625, P = 0.006], the exclusive breastfeeding rate for children aged >6 months was similar in both groups 10/46 (21.7%) vs. 28/150 (18.7%); χ2 = 0.213, P = 0.645].

Sites of Antenatal Care and Breastfeeding Practices

A significantly higher proportion of the mothers who received clinic-based antenatal care commenced breastfeeding within 1 h of birth [95 (45.0%) vs. 3 (5.9%); χ2 = 30.685, P with Yate’s correction <0.01]. A significantly lower proportion of mothers who had clinic-based antenatal care gave pre-lacteal feeds [67 (31.8%) vs. 29 (56.9%); χ2 = 11.154, P = 0.001]. Ironically, for children aged >6 months, a significantly higher proportion of this group of mothers practiced exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months [35/156 (22.4%) vs. 3/40 (7.5%); χ2 = 4.072, P with Yate’s correction = 0.044].

Sites of Delivery and Breastfeeding Practices

A significantly higher proportion of the children delivered in health facilities were commenced on breastfeeding within 1 h of birth compared to the others [86 (54.4%) vs. 12 (11.5%); χ2 = 49.28, P < 0.001]. Similarly, a significantly lower proportion of children delivered in health facilities had pre-lacteal feeding [39 (25.7%) vs. 57 (54.8%); χ2 = 24.516, P < 0.001]. For children aged >6 months, a significantly higher proportion of those delivered in health facilities were exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months [29/116 (25.0%) vs. 9/80 (11.2%); χ2 = 5.728, P = 0.017].

Logistic Regression of Determinants of Poor Breastfeeding Practices

After controlling for the mothers’ awareness of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, the potential risk factors for poor breastfeeding practices identified above (maternal occupation, education and sites of antenatal care and delivery) were correlated with specific breastfeeding indices in a logistic regression model. Table 2 shows delayed initiation of breastfeeding was significantly associated with lack of clinic-based antenatal care (P = 0.036) and delivery outside health facilities (P < 0.001). The use of pre-lacteal feeds was also significantly associated with low maternal education (P = 0.004), lack of clinic-based antenatal care (P = 0.002) and delivery outside health facilities (P = 0.003). Similarly, failure to breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months of life was significantly associated with low maternal education (P = 0.008), occupation as a professional (P = 0.024) and delivery outside health facilities (P = 0.049).

Discussion

This study examined the rate of specific breastfeeding indices among mothers of diverse social characteristics. Although all the respondents in this study breastfed their children, the rates of timely initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding were low in agreement with previous reports from Nigeria and other parts of the developing world [3, 11, 20]. However, 37% of the respondents in the present study initiated breastfeeding within 1 h compared with 8% reported among rural women in Sokoto, Nigeria [16]. This difference may be attributed to the fact that the respondents in the present study were a mixture of rural and semi-urban populations unlike the uniformly rural population in the Sokoto, Nigeria study. On the other hand, the timely breastfeeding initiation rate was higher (62.5%) in a Canadian study [14]. This may be a reflection of better awareness and acceptance of the tenets of the Baby Friendly Initiative in the latter population as previously suggested [15]. Thus, intense health education is required in most parts of the developing world, particularly resource-poor areas, to improve timely initiation of breastfeeding.

This study also shows that breastfeeding practices did not differ significantly with respect to maternal age and parity. This may suggest that mothers of high parity who are ordinarily more experienced may not necessarily practice breastfeeding as recommended. However, breastfeeding practices were better among mothers with at least secondary education, mothers who received clinic-based antenatal care and those who delivered their children in orthodox health facilities. Maternal education up to at least the secondary level positively influenced timely initiation, exclusive breastfeeding and avoidance of pre-lacteal feeding in agreement with previous reports [1, 2, 11, 20]. This may be related to the fact that educated mothers are more likely to have better access to and make better use of current health information.

Interestingly, maternal occupation as a professional did not particularly appear to confer any advantage on breastfeeding practices. Although, bivariate analysis showed that the professionals avoided pre-lacteal feeding, they also delayed initiation of breastfeeding and failed to exclusively breastfeed their infants in the present study. This agreed with previous reports that working mothers practiced exclusive breastfeeding poorly [6, 9]. This may be attributed to the fact that professionals and other working mothers are under pressure to return to work and thus, can devote very little time to breastfeeding. The design of this study did not assume that only the professionals work. Indeed, most of the non-professionals are also self-employed but enjoy more flexibility in their time schedules compared to government- or company-employed professionals who work under rigid time schedules. Therefore, it is attractive to postulate that non-professionals are able to devote more time to breastfeeding compared to professionals.

From the present study, it appears the gains of high education in good breastfeeding practices may be negated by the demands of occupation. Therefore, the national breastfeeding policy needs to provide adequate protection for working-class mothers so that they could have better opportunities to breastfeed their infants despite the demands of their work. Crèches should also be provided in such situations so that nursing mothers could have better access to their children.

Similar to a report from Accra, Ghana, [3] mothers who utilized orthodox obstetric services in this study had better breastfeeding practices according to bivariate analysis. This may be related to the fact that parturients are routinely counselled on good breastfeeding practices according to the BFHI before and after delivery in most orthodox health facilities. Although this study did not lay emphasis on the BFHI status of the places of delivery used by the respondents, there is evidence that the BFHI may have spread out of “Baby-Friendly” health facilities into other public and private clinics in Nigeria [17, 18]. Therefore, mothers who patronised orthodox health facilities for maternity services were likely to have better access to information about care of the newborn, particularly with regards to breastfeeding.

Maternal age and parity did not significantly influence any specific poor breastfeeding practice in the bivariate analysis in the present study unlike what had been previously reported [1, 6, 11, 20]. Nevertheless, multivariate analysis showed that lack of clinic-based antenatal care and delivery outside orthodox health facilities were determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding and pre-lacteal feeding. It also showed that low maternal education contributed to pre-lacteal feeding and failure to breastfeed exclusively. The negative influence of lack of orthodox antenatal care and delivery in health facilities on breastfeeding practices in the present study agreed with previous reports.[3, 8] It may suggest lack of access to information since expectant mothers who utilized these facilities are routinely counselled on appropriate breastfeeding practices [19]. Therefore, measures that would improve the utilization of these health facilities and guarantee better access to health information about the BFI should be put in place. Intense health education and heavily subsidized maternity services may be employed for this purpose.

The limitations in this study are acknowledged. Selection bias was minimised by using a clinic attended by both sick and well children and by women in both the lower and the upper socioeconomic groups [17, 18]. The design of the study also disallowed the clustering of mothers, thus, it was unlikely that mothers with certain socio-demographic characteristics were concentrated in certain groups. We acknowledge the likelihood of recall bias but this effect was minimised by the restriction of the age of index children to within 24 months.

Conclusion

Initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding was poor among mothers without secondary education and those who did not utilize orthodox antenatal care and delivery services. The contribution of the present study to knowledge is that it highlights the persistence of poor breastfeeding practices in a Nigerian setting despite high awareness of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. These may reflect lack of access to health information about appropriate breastfeeding practices. Therefore, the contribution of the present study to programme intervention includes the need for improved health education about timely initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding, female education as well as better utilization of orthodox maternity services as ways of improving access to and utilization of vital health information particularly about breastfeeding.

References

Agampodi, S. B., Agampodi, T. C., & Piyaseeh, U. K. (2007). Breastfeeding practices in a public health field practice area in Sri Lanka: A survival analysis. International Breastfeeding Journal, 2, 13. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-2-13.

Aghaji, M. N. (2002). Exclusive breastfeeding practices and associated factors in Enugu, Nigeria. West African Journal of Medicine, 21, 66–69.

Aidam, B. A., Perez-Escamilla, R., Lartey, A., & Aidam, J. (2005). Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in Accra, Ghana. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59, 789–796. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602144.

Alam, M. U., Rahman, M., & Rahman, F. (2002). Effectiveness of Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative on the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding among the Dhakar city dwellers in Bangladesh. Mymensingh Medical Journal, 11, 94–99.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2005). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 115, 496–506. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2491.

Bertini, G., Perugi, S., Dani, C., Pezzati, M., Tronchin, M., & Rubaltelli, F. F. (2003). Maternal education and the incidence and duration of breastfeeding: A prospective study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 37, 447–452. doi:10.1097/00005176-200310000-00009.

Broadfoot, M., Britten, J., Tappin, D. M., & Mackenzie, J. M. (2005). The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative and breastfeeding rates in Scotland. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 90, F114–F116. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.041558.

Butler, S., Williams, M., Tukuitanga, C., & Paterson, J. (2004). Factors associated with not breastfeeding exclusively among mothers of a cohort of Pacific infants in New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 117, U908.

Cham, S. K., & Asirvatham, C. V. (2001). Feeding practices of infants delivered in a district hospital during the implementation of Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 56, 71–76.

Davies-Adetugbo, A. A. (1997). Sociocultural factors and the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in rural Yoruba communities of Osun State, Nigeria. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 113–125. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00320-6.

Dubois, L., & Girard, M. (2003). Social determinants of initiation, duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding at the population level; the results of the longitudinal study of child development in Quebec (ELDEQ 1998–2002). Canadian Journal of Public Health, 94, 300–305.

Duong, D. V., Binns, C. W., & Lee, A. H. (2004). Breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding in rural Vietnam. Public Health Nutrition, 7, 795–799. doi:10.1079/PHN2004609.

Lawoyin, T. O., Olawuyi, J. F., & Onadeko, M. O. (2001). Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in Ibadan, Nigeria. Journal of Human Lactation, 17, 321–325. doi:10.1177/089033440101700406.

Leger-Leblanc, G., & Rioux, F. M. (2008). Effect of a prenatal nutritional intervention program on initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 69, 101–105. doi:10.3148/69.2.2008.101.

Merten, S., Dratva, J., & Ackermann-Lierbrich, U. (2005). Do Baby Friendly Hospitals influence breastfeeding duration on a national level? Pediatrics, 116, e702–e708. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0537.

Oche, M. O., & Umar, A. S. (2008). Breastfeeding of mothers in a rural community of Sokoto, Nigeria. The Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal, 15, 101–114.

Ogunlesi, T. A., Dedeke, I. O. F., Okeniyi, J. A. O., & Oyedeji, G. A. (2005). The Impact of Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding practices in Ilesa. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics, 32, 46–51.

Ogunlesi, T. A., Okeniyi, J. A. O., Oyedeji, G. A., & Oyedeji, O. A. (2005). The influence of maternal socioeconomic status on the management of malaria in their children: Implications for the Roll Back Malaria Initiative. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics, 32, 40–46.

Ojofeitimi, E. O., Esimai, O. A., Owolabi, O. O., Oluwabusi, O., Olaobaju, O. F., & Olanuga, T. O. (2004). Breastfeeding practices in urban and rural health centres: Impact of Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative in Ile- Ife, Nigeria. Nutrition and Health (Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire), 14, 119–125.

Salami, L. I. (2008). Factors influencing breastfeeding practices in Edo State, Nigeria. Available at http://ajfand.net/issue-XI-files/pdfs/SALAMI_1680.pdf. Accessed on 10th January 8.

Simard, I., O’Brien, H. T., Beaudoin, A., et al. (2005). Factors influencing the initiation and duration of breastfeeding among low-income women followed by the Canadian Prenatal Nutrition Program in four regions of Quebec. Journal of Human Lactation, 21, 327–337. doi:10.1177/0890334405275831.

Sivet, V., CAstel, C., Boilean, P., Castetbon, K., & Foix L’helias, L. (2008). Factors associated to breastfeeding up to 6 months in the maternity of Antoine-Beclere Hospital, Clamart. Archives de Pediatrie, 15, 1167–1173. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2008.04.014.

WHO. (2001). Report of the expert consultation on the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Geneva, Switzerland. WHO/NHD/01.09.

WHO. (2007). Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for Integrated Care 2006. Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/BFHI_Revised_Section3.1.pdf. Accessed on 10th December 2007.

WHO/UNICEF. (1989). Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding-the special role of maternity services. A joint WHO/UNICEF Statement. WHO, Geneva.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ogunlesi, T.A. Maternal Socio-Demographic Factors Influencing the Initiation and Exclusivity of Breastfeeding in a Nigerian Semi-Urban Setting. Matern Child Health J 14, 459–465 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0440-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0440-3