Abstract

Much of the literature investigating the association between coping and psychopathology is cross-sectional, or associations have been investigated in a unidirectional manner; hence, bidirectionality between coping and psychopathology remains largely untested. To address this gap, this study investigated bidirectional relations between coping and psychopathology during pre-adolescence. Participants (N = 532, 51% male) and their primary caregiver both completed questionnaires assessing pre-adolescents’ coping (i.e., avoidant, problem solving, social support seeking) and symptoms of psychopathology (i.e., generalized anxiety, social anxiety, depression, eating pathology) in Wave 1 (Mage = 11.18 years, SD = 0.56, range = 10–12) and Wave 2 (Mage = 12.18 years, SD = 0.53, range = 11–13, 52% male), one year later. Cross-lagged panel models showed child-reported avoidant coping predicted increases in symptoms of generalized and social anxiety, and eating pathology. In separate child and parent models, symptoms of depression predicted increases in avoidant coping. Greater parent-reported child depressive symptoms also predicted decreases in problem solving coping. Taken together, results suggest unique longitudinal associations between coping and psychopathology in pre-adolescence, with avoidant coping preceding increases in symptoms of anxiety and eating pathology, and depressive symptoms predicting later increases in maladaptive coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coping has been defined as the constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific demands that are appraised as taxing (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Associations between coping and psychopathology have long been investigated (Compas 1987), although, much of the extant literature in this area is cross-sectional, which limits understanding of the direction of these associations (Compas et al. 2017). Of the longitudinal studies conducted, most have investigated coping as a vulnerability factor for psychopathology. However, a recent theory suggests coping and symptoms of psychopathology are likely to be bidirectionally related (Zimmer‐Gembeck and Skinner 2016). That is, particular coping strategies may increase risk for psychopathology, and psychopathology may also impair the development of, or ability to use, particular coping skills (Compas et al. 2017). The transition from late childhood to early adolescence appears to herald significant changes in both coping and increases in psychopathology (Rapee et al. 2019; Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). As such, the present study aimed to investigate directionality between coping strategies that undergo significant change from childhood to adolescence (avoidant coping, problem solving, social support seeking) and symptoms of psychopathology (generalized anxiety, social anxiety, depression and disordered eating) in a sample of pre-adolescents.

Psychopathology and Coping in Adolescence

Pre-adolescence spans from age 10 to 12, and is a period of physical change (e.g., physical growth, hormonal changes) as well as cognitive and social development (e.g., autonomy seeking, widening of social networks; Gilmore and Meersand 2013). Pre-adolescence is also a key developmental period in which to study the potential risks and antecedents (e.g., coping styles) of psychopathology, as it immediately precedes a sharp increase in the prevalence and severity of some social-emotional domains of psychopathology, like anxiety, depression and eating pathology (Rapee et al. 2019). For example, the incidence of depression is five times higher in individuals aged 12 to 17 years compared to those aged four to 11 years; and 23% of 12 to 17 year olds who have a mental disorder report it having a severe impact on their lives, compared to only 8.2% of those aged 4 to 11 years (Lawrence et al. 2015). Further, social anxiety usually develops in early adolescence (~13 years) (Kessler et al. 2005). Although commonly conceptualized as a disorder of adulthood, there is evidence that generalized anxiety disorder may develop during adolescence in a subgroup of individuals (Rhebergen et al. 2017). The onset of puberty in early adolescence also appears to herald the onset of mood and eating disorders (Kessler et al. 2007; Klump 2013). As the risk of developing social anxiety, generalized anxiety, depression and eating disorders increases markedly from pre- to mid-adolescence, this paper focuses on these four outcomes.

Coping strategies can be conceptualized as either problem focused, or emotion focused (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Problem focused coping encompasses strategies designed to resolve situations giving rise to stress (e.g., problem solving), whilst emotion focused coping strategies are employed to modulate emotions (e.g., social support seeking, avoidant coping) (Compas et al. 2017). Problem solving involves adjusting one’s own actions to be effective (e.g., making a plan about what to do). In contrast, social support seeking can involve using available social resources to elicit care and esteem (e.g., asking a friend to make you feel better), and avoidant coping involves cognitive (e.g., mental suppression) or behavioral (e.g., avoiding people) strategies which may prevent or minimize the need to address the stressor (e.g., avoiding the problem by sleeping more) (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). While avoidance of particular feared cues is common in psychopathology, avoidant coping here refers to a broader style of dealing with stressors in an avoidant way.

Like risk for psychopathology, coping also undergoes significant change during the pre-adolescent period. Avoidant coping decreases during late childhood/early adolescence, whereas problem solving increases (Eschenbeck et al. 2018; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). Social support seeking from parents also appears to decrease, but is likely transferred to peers. Avoidant coping, problem solving and social support seeking from friends all undergo significant change in the transition from childhood to adolescence (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011), thus, these coping strategies will be the focus of the current study.

Bidirectionality between Coping Strategies and Psychopathology

Given exposure to stress is one of the strongest predictors of psychopathology in adolescence, the importance of investigating coping as a risk/protective factor is clearly evident (Compas et al. 2017). Whilst exposure to stressors is inevitable, individual differences in the use of coping strategies may help to explain why some young people are resilient to stress, whilst others become vulnerable to symptoms of psychopathology. It has been suggested that ineffective coping may repel positive supports from peers and adults (e.g., families, teachers) and undermine self-regulation, which sets young people on the path towards developing psychopathology (Zimmer‐Gembeck and Skinner 2016).

However, psychopathology itself may also make it more difficult to effectively cope with stress, by impairing the development of, or ability to use, coping skills (Zimmer‐Gembeck and Skinner 2016). For example, young people experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety or other forms of psychological distress, may use ineffective coping strategies, may find it more difficult to use effective coping strategies and may draw from a smaller repertoire of coping strategies (Zimmer‐Gembeck and Skinner 2016). Given psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety, eating pathology) in early life is associated with worse long term outcomes, including the persistence of primary (i.e., initial) and the development of secondary (i.e., comorbid) mental health conditions, substance dependence, poor physical health and educational underachievement (Johnson et al. 2002; Lewinsohn et al. 1999; Woodward and Fergusson 2001), it is important to identify potential risk factors for escalating levels of emotional distress across adolescence. Changes in coping may emerge as one such risk factor; however, the link from different forms of psychopathology to particular coping strategies is not yet clear.

Since much of the empirical literature has examined forms of psychopathology in isolation, it is unclear whether particular coping strategies are uniquely associated with particular forms of psychopathology, and vice versa. This is an important research gap since use of particular coping strategies (e.g., problem-focused strategies) and internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) likely show significant overlap (i.e., shared variance). Therefore, it is important for the field to elucidate unique associations between particular coping strategies and forms of psychopathology, rather than capturing more general associations (i.e., between coping and internalizing more broadly). Indeed within other literatures (e.g., cognitive vulnerabilities in depression), there is evidence that different vulnerabilities have different relationships with psychological outcomes (Bernstein et al. 2019). Overall, there is a need to further elucidate the etiology of psychological disorders, which can then inform prevention and treatment approaches (Compas et al. 2017). As the present study investigates the directionality of the associations between avoidant coping, problem solving and social support seeking from friends and symptoms of psychopathology, the following review of the existing literature is limited only to longitudinal and experimental evidence of these associations in young people.

Avoidant Coping and Psychopathology

Although avoidant coping is likely a key modifiable risk factor implicated in the development of anxiety in young people (Rapee 2002), there is a dearth of longitudinal research. Available studies suggest that reductions in avoidant coping precede improvements in social and generalized anxiety in children and adolescents (8–18 years) (Hogendoorn et al. 2014) and parental facilitation of pre-adolescent (~10–12.5 years) avoidance (e.g., parental overprotection, family accommodation) predicts subsequent increases in early adolescent (~12.5–13.5 years) anxiety (total anxiety; Borelli et al. 2015; Rapee 2009) and poorer treatment outcomes (Salloum et al. 2018).

In relation to mood disorders, multiple longitudinal studies with adolescents have found avoidant coping to be associated with heightened risk for depression (Herman-Stabl et al. 1995; Sawyer et al. 2009; Seiffge-Krenke and Klessinger 2000). Whilst avoidant coping consistently predicted higher depressive symptoms at one to three years follow-up across three studies (Herman-Stabl et al. 1995; Sawyer et al. 2009), the findings of Seiffge-Krenke and Klessinger (2000) are particularly compelling. Namely, adolescents who used avoidant coping at Times 1 and 2 (~14 and 15 years, respectively), reported the highest levels of depressive symptoms at Times 3 and 4 (~16 and 17 years, respectively), irrespective of whether their coping style had changed to a more adaptive form (Seiffge-Krenke and Klessinger 2000). Together, these studies suggest a robust association between avoidant coping and depressive symptoms.

One theory of anorexia nervosa has proposed that avoidance of emotions and interpersonal relations may precede, and be worsened by, symptoms of disordered eating (Schmidt and Treasure 2006). Most research in this area to date has been conducted with adult clinical populations (Ghaderi 2003) and the only longitudinal study in young people found avoidance coping did not uniquely predict disordered eating in adolescent girls three years later, after controlling for earlier disordered eating behavior and other coping strategies (Halvarsson-Edlund et al. 2008). Collectively, these results may suggest specificity of avoidant coping to anxiety and depression in adolescence, but not eating pathology. However, substantially less evidence has evaluated whether adolescent mental health predicts subsequent avoidant coping. Evidence of reciprocal associations between avoidant coping, and symptoms of generalized anxiety and depression have been found in adults (Grant et al. 2013), but understanding these associations in pre-adolescence is particularly important given the changes in this developmental period for both coping and psychopathology.

Problem Solving and Psychopathology

Longitudinal evidence relating to associations between coping via problem solving and symptoms of psychopathology is limited, and findings mixed. An early study found problem solving showed no association with either younger or older adolescents’ levels of trait anxiety five months later (Glyshaw et al. 1989). Similarly, another study found that problem solving in adolescent girls did not predict subsequent disturbed eating attitudes (Halvarsson-Edlund et al. 2008). The majority of studies have also not found prospective associations between problem solving and subsequent depressive symptomology in adolescents (Abela et al. 2002; Davila et al. 1995; Malooly et al. 2017; Pantaleao and Ohannessian 2019). In contrast, Van Voorhees et al. (2008) found active coping, including problem solving, predicted lower risk of new-onset depression one year later. Similarly, a problem solving intervention was found to effectively reduce depressive symptoms and suicide risk in adolescents (Eskin et al. 2008; Spence et al. 2003). Further, there is also some prospective evidence demonstrating that depression precedes decreases in task-oriented coping, including problem solving, suggesting that depression may inhibit the development and subsequent use of problem solving as an effective coping strategy among adolescents (Nrugham et al. 2012). Given the dearth of literature examining possible bidirectionality between psychopathology and problem solving coping, further research is needed.

Social Support Seeking and Psychopathology

Numerous longitudinal studies have concluded that social support seeking protects adolescents from developing symptoms of depression and anxiety (Burton et al. 2004; DuBois et al. 1992; Zimmerman et al. 2000). Evidence pertaining to the source of social support is mixed, although there is some evidence that support sought from friends (Burton et al. 2004), as well as from families (Zimmerman et al. 2000) and schools (DuBois et al. 1992) is protective for adolescent mental health. Only one study has looked at the relation between social support seeking and eating pathology in female adolescents, and found social support seeking did not uniquely predict disturbed eating attitudes three years later, although this study did not appear to differentiate the source of social support (Halvarsson-Edlund et al. 2008). Again, this may point to specificity in the relations between coping and psychopathology symptoms.

In terms of the inverse associations, research on anxiety predicting subsequent social support seeking from family has shown mixed evidence and further studies are needed (Wright et al. 2010; Zimmerman et al. 2000). However, depressive symptoms appear to predict decreases in social support seeking from friends, but not parents (DuBois et al. 1992; Stice et al. 2004; Zimmerman et al. 2000). To the best of our knowledge, the association from eating pathology to subsequent social support seeking has not yet been studied and thus warrants attention.

Gender, Coping and Psychopathology

Gender differences are observable in both the use of coping strategies and symptoms of psychopathology. Namely, early adolescent girls report greater use of instrumental and emotional social support seeking and problem solving, than boys (Eschenbeck et al. 2018; Hampel 2007; Malooly et al. 2017). Whereas, boys report greater use of avoidant coping (Eschenbeck et al. 2018). Girls are also at greater risk of experiencing depression (Breslau et al. 2017), anxiety (Lewinsohn et al. 1998), and eating pathology (Rojo-Moreno et al. 2015); with this pattern of risk evident prior to adolescence. In adults, coping strategies are similarly related to psychopathology irrespective of gender (Nolen-Hoeksema 2012). However, little is known about whether the strength of associations between coping strategies and psychopathology differ by gender in young people. Therefore, the final aim of the present study was to explore gender as a moderator of the association between coping and psychopathology.

Hypotheses

Bidirectionality between coping and psychopathology has rarely been investigated in the extant literature, and typically only one form of psychopathology (e.g., depression) is examined in isolation. The current study addresses these gaps by evaluating whether coping strategies may be implicated in the progression of particular forms of psychopathology and/or whether symptoms of psychopathology may also alter how individual’s cope with stress. It was hypothesized that social support seeking from friends would protect adolescents from developing symptoms of depression, anxiety and eating pathology over time. Avoidant coping was expected to be related to increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety, but not symptoms of disordered eating. Given mixed evidence for the association between problem solving and symptoms of anxiety, depression and eating pathology, we had no explicit hypothesis for this coping strategy. In line with theory and past research, it was hypothesized that symptoms of depression would predict reduced problem solving coping and social support seeking from friends over time. Other changes in coping in response to psychopathology were investigated, but were exploratory in nature. Finally, the present study explored whether gender moderated cross-lagged associations between coping and symptoms of psychopathology.

Method

Participants

A total of 532 Australian pre-adolescents in Grade 6 (Mage = 11.18, SD = 0.56, range = 11–13, 51% male) and their parent/primary caregiver (96% mothers) participated in Wave 1 (2016–2017) and 500 (Mage = 12.18, SD = 0.53, range: 12–14, 52% male) of these child–parent dyads completed relevant measures again in Wave 2 (2017–2018), approximately one year later. This time frame was chosen since it captured the transition from primary schooling (Grade 6) to secondary schooling (Grade 7) in Australia. Approximately 90% of participants were born in Australia (3% United Kingdom, 1.5% Unites States, 0.8% New Zealand, 0.6% South Africa, 3.5% other), with 82% reporting having white European origins (6.6% Asian, 1.5% Middle Eastern, 10% other). Most (96.4%) participants spoke English as their first language at home (1.1% Mandarin, 0.2% Italian, 2.3% other), and approximately 80% of families reported being middle to high income households. Participants were recruited from the general public, via advertisements placed in schools, sporting clubs and medical centers in Sydney, Australia. Sample characteristic are representative of the surrounding community. Other than needing to be in Grade 6, there were no explicit inclusion or exclusion criteria.

Procedures

Each year, participants and their primary caregiver completed an online questionnaire at home, assessing a number of psychological constructs, including adolescent coping (i.e., avoidant coping, problem solving, social support seeking) and symptoms of psychopathology (i.e., generalized anxiety, social anxiety, depression, eating pathology). Each family’s participation was part of the larger longitudinal Risks to Adolescent Wellbeing (RAW) Project, which aims to elucidate risk and protective factors for emotional distress in adolescence. Each year participants were given a small gratitude bag of products and AUD $100 gift card as remuneration for their involvement in the study. The RAW Project was approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee. Active informed consent was obtained from all parents and written assent was obtained from pre-adolescents. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council under Grant Number FL150100096.

Measures

Coping strategies

The Adolescent Coping Strategy Index (ACSI; Parada 2006) is a 15-item measure adapted from the Coping Strategy Indicator (Amirkhan 1990). Participants are asked to consider how they act when faced with difficulties or problems, with 6 items assessing Problem Avoidance (e.g., “I avoid the problem by spending more time alone”), 5 items assessing Active Problem Solving (e.g., “I make a plan about what I will do”) and 4 items assessing Social Support Seeking from friends (e.g., “I go to a friend to help me feel better”). Given data from the current study comes from a larger longitudinal study, which aims to measure psychopathology and related constructs throughout adolescence, and peer social support is comparatively more important in the adolescent developmental period, social support seeking from peers, but not parents, was measured. Items for each subscale were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = Very Often). Average subscale scores were calculated across relevant items for each participant (possible range 1–5), with higher scores indicating greater dispositional use of each coping strategy. To increase the validity of reported coping strategies in the current study, the adolescent version of the ACSI was adapted to create an additional parent-report version of the scale, with the pronoun “I” replaced with “my child”. Internal consistency of the child (Wave 1; Wave 2: Problem Avoidance α = 0.77; 0.83, Problem Solving α = 0.88; 0.88, Social Support Seeking α = 0.88; 0.91) and parent (Wave 1; Wave 2: Problem Avoidance α = 0.81; 0.85, Problem Solving α = 0.88; 0.91, Social Support Seeking α = 0.89; 0.90) scales were acceptable, in line with past research (ACSI-C Problem Avoidance α = 0.75, Problem Solving α = 0.86 and Social Support Seeking α = 0.90) (Parada 2006). Temporal stability in coping strategies between Wave 1 and 2 was slightly lower for child-report (Avoidant Coping: r = 0.41; Problem Solving: r = 0.39; Social Support Seeking: r = 0.46), relative to parent-report (Avoidant Coping: r = 0.59; Problem Solving: r = 0.62; Social Support Seeking: r = 0.55).

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety severity was measured using the Generalized Anxiety (e.g., “I worry about things”) and Social Anxiety (e.g., “I worry what other people think of me”) subscales from the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale-Child Report (SCAS-C) and Parent Report (SCAS-P) (Spence 1998). The 6 items from each subscale are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Never, 3 = Always), with total possible subscale scores ranging from 0–18. Higher scores indicate greater severity of anxiety symptoms. Internal consistency for each subscale was acceptable for child- (Wave 1; Wave 2: Generalized Anxiety: α = 0.77; 0.81, Social Anxiety: α = 0.76; 0.78) and parent-report (Wave 1; Wave 2: Generalized Anxiety: α = 0.77; 0.77, Social Anxiety: α = 0.73; 0.76) in the present study, similar to previous reports (α = 0.73 and α = 0.70, respectively) (Spence 1998). Temporal stability in symptoms of anxiety between Wave 1 and 2 was similar for child- (GAD: r = 0.55; Social Anxiety: r = 0.61) and parent-report (GAD: r = 0.60; Social Anxiety: r = 0.59).

Depressive symptoms

Symptoms of depression were measured using the 13-item Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Child Report (SMFQ-C) and Parent Report (SMFQ-P) (Angold et al. 1995). Participants rated a series of 13 statements (e.g., “I felt miserable or unhappy”) on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = Not True, 1 = Sometimes True, 2 = Always True), based on how true they were over the past 2 weeks. Total scores could range from 0–26, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depressive symptoms. The SMFQ had good internal consistency in the current study for both the child- (Wave 1: α = 0.83; Wave 2: α = 0.86) and parent-report (Wave 1: α = 0.88; Wave 2: α = 0.88), similar to previous research (α = 0.85) (Angold et al. 1995). Temporal stability in depressive symptoms between Wave 1 and 2 was similar for child- (r = 0.54) and parent-report (r = 0.57).

Eating pathology symptoms

Symptoms of eating pathology were measured using the 26 item Children’s Eating Attitude Test (ChEAT) (Maloney et al. 1988). Pre-adolescents rated how often each item (e.g., “I stay away from eating when I am hungry”, “I have gone on eating binges where I feel that I might not be able to stop”) applies to them, on a 6-point likert scale (0 = Never, 0 = Rarely, 0 = Sometimes, 1 = Often, 2 = Very Often, 3 = Always). Total scores could range from 0–78, with higher scores indicating more disordered eating. The ChEAT had good internal consistency in the current study (Wave 1: α = 0.82; Wave 2: α = 0.84), consistent with past research (α = 0.76; Maloney et al. 1988). Temporal stability in eating pathology was within expected limits (r = 0.52).

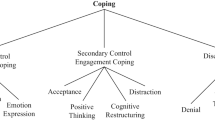

Statistical Analysis

Data aggregation and preliminary descriptive analyses were undertaken using SPSS. Cross-lagged panel models of the observed coping and psychopathology variables were conducted with Mplus version 8.1 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). Child- and parent-report data were analyzed in two separate but identical models. Analyses were originally conducted based on aggregated parent/child data. The results were very similar to the current child-report model. However, based on feedback during the review process for this manuscript we separated child- and parent-report data for analysis. To understand the temporal associations between coping and psychopathology over time, a single model was specified with the inclusion of all autoregressive paths (i.e., controlling for baseline levels) and the cross-lagged paths from coping styles to symptoms of psychopathology, and from symptoms of psychopathology to coping styles whilst controlling for gender (i.e., over and above the shared variance among the coping strategies and psychopathology outcomes; see Fig. 1). Standardized beta coefficients are reported to allow for comparisons of the relative strength of longitudinal associations. Moderation by gender was then tested in a multi-group analysis framework where the unconstrained model was simultaneously estimated for boys and girls, and then again with equality constraints placed on all regression paths between the two groups. Evidence of moderation was examined using the Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square difference test, whereby differences in model fit between the unconstrained and constrained models were compared with significant differences in model fit indicative of moderation (Satorra 2000).

There were very low levels of missing data for child- (0.9–1.5%) and parent-reported (0.2–0.4%) subscales in Wave 1, and slightly higher levels of missing data for child- (7.5–8.1%) and parent-reported (6.2–6.4%) subscales in Wave 2, due to attrition. Missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) in Mplus. Participants who did not complete Wave 2 of the study (n = 32) did not differ from the remainder of the sample with regard to their baseline mental health or coping strategies (all p > 0.05). Given the use of a community sample, psychopathology outcomes were significantly positively skewed. Consequently, the MLR robust maximum likelihood estimator were used to estimate descriptive and cross-lagged analyses, respectively. Given the large number of comparisons in the current paper, significance levels were adjusted to account for a paper-wide 5% false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). The first raw p value to exceed the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p value corresponding to a false discovery rate of 5% was p = 0.031.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics relating to symptoms of psychopathology and coping are presented in Table 1. Paired sample t-tests were performed to determine differences in psychopathology and coping strategies from Wave 1 to Wave 2. As shown in Table 1, significant decreases in levels of child- and parent-reported generalized anxiety were observed from Wave 1 to Wave 2, with small to medium effect sizes. There were also small and statistically significant decreases in child-reported avoidant coping from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Statistically significant Wave 1 to Wave 2 differences were also found for child-reported symptoms of depression, and parent-reported social support seeking, but, the effect sizes for these latter variables were negligible.

As shown in Table 2, girls had significantly higher social anxiety and social support seeking from friends, compared to boys in Wave 1 and 2. As per child-reported mental health, girls also had higher symptoms of generalized anxiety and depression in Wave 2. Parent-report indicated that boys had higher avoidant coping and lower problem solving than girls in Wave 1 and 2, with small effects observed. Consequently, gender was both tested as a moderator and a covariate in separate cross-lagged analyses.

The Pearson correlations between child-reported variables are summarized in Table 3. Avoidant coping was significantly positively correlated with all mental health outcomes, with large concurrent (within-wave) correlations with symptoms of depression, moderate correlations with symptoms of social and generalized anxiety, and small correlations with symptoms of disordered eating at each time wave. Small negative concurrent correlations were evident between problem solving and symptoms of depression and anxiety. A small negative concurrent correlation was also observed between social support seeking and depressive symptoms at Wave 1. However, social support seeking had trivial and non-significant associations with other mental health outcomes.

Similar patterns emerged in the parent-reported variables, shown in Table 4. Avoidant coping was significantly positively correlated with all mental health outcomes, with moderate concurrent (within wave) correlations with symptoms of depression and small-to-moderate correlations with symptoms of generalized and social anxiety at each time wave. Moderate negative concurrent correlations emerged between problem solving and symptoms of depression, with small negative correlations between problem solving and symptoms of social anxiety. A small negative concurrent correlation was observed between social support seeking and depressive symptoms in both waves. However, social support seeking had trivial and non-significant associations with other mental health outcomes.

Cross-Lagged Analyses

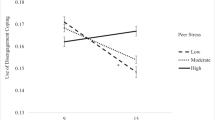

Figure 2 depicts the statistically significant paths in the cross-lagged panel model using child-reported data and Table 5 gives standardized beta coefficients for all estimated paths between child-reported coping strategies and symptoms of psychopathology. Higher levels of avoidant coping at Wave 1 uniquely predicted increases in symptoms of generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and eating pathology over time. Higher symptoms of depression at Wave 1 also uniquely predicted increases in avoidant coping over time. Exploratory moderation analyses revealed that imposing gender equality constraints on the model paths did not adversely affect model fit, as indicated by the non-significant Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests (χ2(31) = 24.50, p = 0.790). Thus there was no evidence of gender moderation found.

Figure 3 depicts the statistically significant paths in the cross-lagged panel model using parent-reported data and Table 6 gives standardized beta coefficients for all estimated paths between parent-reported adolescent coping strategies and symptoms of psychopathology. Higher symptoms of depression at Wave 1 uniquely predicted increases in avoidant coping and decreases in problem solving coping over time. Exploratory moderation by gender was tested by constraining the paths to equality across gender and did not adversely affect model fit, based on the non-significant Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests (χ2(31) = 26.84, p = 0.680), once again indicating that strength of the associations tested did not vary by gender.

Schematic illustrating the statistically significant relations between parent-reported coping and symptoms of psychopathology and child-reported eating pathology at Wave 1 and Wave 2, controlling for gender. Solid black arrows indicate significant paths. Dashed gray lines indicated paths that were estimated, but non-significant

Discussion

Previous longitudinal studies have largely investigated coping and a single form of psychological distress in isolation (e.g., depression), and most have tested the association between the two constructs in only one direction. As such, the current study addressed gaps within the extant literature by investigating whether particular coping strategies (i.e., avoidant coping, problem solving, social support seeking) may be implicated in the progression of psychological distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, eating pathology) and/or whether psychological distress itself may alter how individuals cope with stress. The benefit of including many coping strategies and symptoms of psychopathology in the one model is that this form of analysis also elucidates unique associations between particular coping strategies and forms of psychopathology, rather than capturing more general associations (i.e., between coping and internalizing more broadly, since many forms of psychopathology show significant overlap). To address gaps identified in the literature, the current study examined bidirectional relations between coping strategies and symptoms of psychopathology in a large sample of pre-adolescents over a 1-year period. The possibility that gender moderated associations between coping and psychopathology was also explored.

Girls reported more symptoms of social anxiety than boys in Wave 1 and 2, and more generalized anxiety and depression in Wave 2. At this age, gender differences were not evident for symptoms of disordered eating. Consistent with previous research, girls reported greater use of social support seeking as a coping strategy across both time waves, while boys reported greater use of avoidant coping (Eschenbeck et al. 2018). Parents reported that girls used problem solving coping more than boys at both time points. Similar to the adult literature (Nolen-Hoeksema 2012), gender did not moderate the subsequent cross-lagged models of the longitudinal relations between psychopathology and coping.

Broadly speaking, the child-reported model suggests associations primarily from earlier coping to later psychopathology, and the parent-reported model suggests associations from earlier psychopathology to later coping. It is likely that parents are primarily aware of the behavioral manifestations of psychopathology and coping (e.g., behavioral withdrawal), whereas pre-adolescents are better placed to report their internal states (e.g., cognitive avoidance) and subsequent impact on their mental health (e.g., worry). Therefore, in interpreting the results, we place the greatest emphasis on the child-reported model. Where associations are replicated in parent-report, it is anticipated that these relations are particularly robust and/or more evident in behavior, as opposed to cognitions. Given multi-informant data is scarce in the adolescent coping-psychopathology literature, future research is needed to confirm the different patterns observed amongst pre-adolescents and their parents, as discussed below.

Results from the child-reported cross-lagged analysis supported theory that suggests a broad, avoidant style of coping is a key modifiable risk or maintenance factor implicated in the progression of generalized and social anxiety in young people (Rapee 2002). In relation to social anxiety, this may be the case as avoidant coping strategies (e.g., avoiding the problem by spending more time alone, staying away from other people, wishing people would leave me alone) may limit exposure to feared cues (e.g., social situations), which serves to expedite fear learning. In relation to generalized anxiety disorder, preadolescents may use avoidant coping strategies, such as watching more television, sleeping more than usual and pretending there isn’t a problem, as a way to suppress worries. However, thought suppression may paradoxically serve to worsen worry in the long term, and may contribute to the development of unhelpful beliefs (e.g., worry is uncontrollable); both of which may be implicated in the progression of generalized anxiety (Wells 1999).

The child-report model also suggested that avoidant coping predicts greater eating pathology over time. These results are consistent with theory of anorexia nervosa, which suggests that avoidance of emotions and interpersonal relationships may precede disordered eating (Schmidt and Treasure 2006). For example, individuals with anorexia nervosa have been found to display avoidant personality characteristics and are prone to experiential avoidance (i.e., of emotions, emotional memories and interpersonal relationships) (Schmidt and Treasure 2006). Pertinent to anorexia, and other eating disorders, is the idea that dietary restriction facilitates the avoidance of emotions and peers; thus self-starvation can be seen as an avoidance strategy in itself (Schmidt and Treasure 2006). Whilst these findings support theory, with so few longitudinal studies in adolescence (Halvarsson-Edlund et al. 2008), replication of this effect is needed.

In relation to mood, depressive symptoms predicted an increase in avoidant coping in both the child- and parent-report models, suggesting a robust association. These findings are consistent with the extant literature (Seiffge-Krenke and Klessinger 2000) and suggest symptoms of depression (e.g., loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, reduced ability to concentrate, social withdrawal) may lead an individual to increasingly employ an avoidant style of coping, over other, more proactive, coping strategies. The idea that depression may impair the use of proactive styles of coping was supported by findings that earlier symptoms of depression also predicted decreases in problem solving in the parent-report model, although this relationship was not present in the child-report data. Problem solving is likely to be employed when stressors are perceived as controllable (Davey 1994). Given hopelessness and reduced self-efficacy are hallmarks of depression, depressed young people may reduce the use of problem solving coping over time, since they may perceive stressors as uncontrollable.

Given the number of studies that have found social support seeking to protect against symptoms of anxiety and depression (Burton et al. 2004; Zimmerman et al. 2000), it is somewhat surprising that social support seeking did not predict pre-adolescent mental health over time. However, as the measure of social support seeking used in the current study assesses the likelihood of seeking social support from friends, it is possible that familial social support may play a protective role in the pre-adolescent years, until peer networks become better established and increasingly salient later in adolescence (Zimmerman et al. 2000). Indeed, previous studies that have found social support seeking from peers to be protective, have recruited older adolescent samples (i.e., range = 11–15 years) (Burton et al. 2004; Zimmerman et al. 2000).

Whilst there was no evidence for unique bidirectional effects between psychopathology and coping in either the child- or parent-reported cross-lagged models, bivariate correlations suggest small associations between avoidant coping at Wave 1 and all forms of psychopathology at Wave 2, as well as small correlations between all forms of psychopathology at Wave 1 and avoidant coping at Wave 2. Further, results from the child-reported cross-lagged model suggest that symptoms of depression may uniquely contribute to increases in avoidant coping over time, and that avoidant coping may uniquely contribute to increases in generalized anxiety, social anxiety and eating pathology over time. If these effects generalize to later developmental periods, the child self-report results indicate a potential compounding effect over time whereby higher levels of depression predict increases in avoidant coping, which may subsequently predict increases in other domains of social-emotional psychopathology. However, future research is needed to test this assertion.

Developmental and Clinical Implications

Taken together, these results suggest that avoidant coping may be implicated in the development of anxiety and eating pathology in young adolescents. Worth noting, is that there were unique associations between avoidant coping at Wave 1 and generalized anxiety, social anxiety and eating pathology at Wave 2 in the child model. In short, these results are suggestive of multifinality, and thus support the inclusion of “coping” modules in psychosocial prevention strategies targeting the development of psychopathology in pre-adolescents (e.g., Kowalenko et al. 2005). Indeed, preventative interventions that target avoidance of feared cues appear to be effective, at least in the short term (Calear and Christensen 2010). However, results from the current study suggest that addressing avoidant responding more broadly (i.e., as opposed to disorder specific behavioral avoidance/experiential avoidance) may be an additional useful target in the prevention of anxiety and eating pathology in young people. A wide variety of professionals, including teachers and school counselors, are well placed to assist pre-adolescents to develop their coping skill repertoire (including discouraging avoidant coping), and given the universal benefit this may have for adolescent mental health, this approach to the prevention of psychopathology is worthy of further evaluation.

As higher symptoms of depression also predicted increased avoidant coping and reduced problem solving one year later, clinicians working with depressed young clients may also consider focusing on these coping strategies to augment treatment outcomes. Indeed, most evidence-based treatments for depression and anxiety teach cognitive and behavioral coping skills (e.g., problem solving, social engagement) and previous work suggests this may be a fruitful line of inquiry (Eskin et al. 2008; Spence et al. 2003). Whilst these findings support existing interventions, it should be noted that the vast majority of this sample were not experiencing clinical levels of depression, and thus, findings should be interpreted with this in mind.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations that are important to consider in interpreting the results. For example, the focus on three specific coping strategies did not cover all coping strategies, and examination of other common coping strategies (e.g. opposition, self-reliance, accommodation) would be a valuable extension to these findings (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). The inclusion of a measure of social support seeking from family would also be useful when conducting research with pre-adolescents. It would also be a valuable extension to examine these relations in mid-to late adolescence, when symptoms of depression and eating pathology may be more pronounced (i.e., relative to types of anxiety, which have an earlier age of onset; Kessler et al. 2007), and this was reflected in the distribution of symptom severity in the present sample. The lack of parental report of eating pathology is a limitation, as pre-adolescents may potentially underreport disordered eating behaviors. It would also be important to investigate the relation between coping and psychopathology over longer periods of time, given coping is likely to continue to mature and symptoms of psychopathology intensify in older adolescence. Longer follow-up would also allow formal testing of the possibility of a positive feedback loop between coping and psychopathology. In sum, it is possible that other relations between coping strategies, and psychopathology may emerge later in the adolescent developmental period.

Cross-lagged associations were small and the observational nature of the current study precluded the examination of causal associations, so future research on the robustness and nature of these relations is essential. Measuring coping strategies and symptoms of psychopathology at closer intervals may reveal stronger and more consistent associations and thus, may be a fruitful avenue for future research. Future research should also examine other variables that may influence both coping and symptoms of psychopathology, such as the type and number of stressors experienced (Compas et al. 1993). The measure in the present study assessed how frequently each coping strategy is used in a general way, without specifying the type of stressor, which was a limitation of the study, since particular stressors may be more pertinent to certain forms of psychopathology (e.g., interpersonal stress and depression) (Conway et al. 2012). Future research could take a more nuanced approach by investigating coping in particular contexts. Finally, given the sample in the current study was primarily white, with European origins, it would be useful to evaluate whether the same relations emerge in other cultures.

Conclusion

It has been theorized that particular coping strategies may increase the risk for psychopathology, and that psychopathology itself may also impair adaptive coping. This theory, until now, has remained largely untested (Zimmer‐Gembeck and Skinner 2016). Longitudinal cross-lagged panel models in the present study suggest that avoidant coping precedes increases in symptoms of anxiety and eating pathology in pre-adolescence when assessing child-reported functioning. Symptoms of depression predicted an increase in maladaptive coping over time (i.e., increases in avoidant coping and decreases in problem solving). These longitudinal associations between coping and psychopathology may signal an important contributor to the escalation of emotional distress across adolescence. Whilst replication will be important, findings suggest that pre-adolescents’ coping skills may be an appropriate target in the prevention and treatment of psychopathology in adolescence.

References

Abela, J., Brozina, K., & Haigh, E. (2002). An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third-and seventh-grade children: a short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(5), 515–527.

Amirkhan, J. (1990). A factor analytically derived measure of coping: the coping strategy indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1066.

Angold, A., Costello, E., Messer, S., & Pickles, A. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300.

Bernstein, E., Kleiman, E., van Bork, R., Moriarity, D., Mac Giollabhui, N., McNally, R., & Alloy, L. (2019). Unique and predictive relationships between components of cognitive vulnerability and symptoms of depression. Depression and Anxiety, 36(10), 950–959.

Borelli, J., Margolin, G., & Rasmussen, H. (2015). Parental overcontrol as a mechanism explaining the longitudinal association between parent and child anxiety. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(6), 1559–1574.

Breslau, J., Gilman, S., Stein, B., Ruder, T., Gmelin, T., & Miller, E. (2017). Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Translational Psychiatry, 7(5), e1139.

Burton, E., Stice, E., & Seeley, J. (2004). A prospective test of the stress-buffering model of depression in adolescent girls: no support once again. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(4), 689.

Calear, A., & Christensen, H. (2010). Review of internet‐based prevention and treatment programs for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Medical Journal of Australia, 192, S12–S14.

Compas, B. (1987). Stress and life events during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review, 7(3), 275–302.

Compas, B., Jaser, S., Bettis, A., Watson, K., Gruhn, M., Dunbar, J., & Thigpen, J. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939.

Compas, B., Orosan, P., & Grant, K. (1993). Adolescent stress and coping: implications for psychopathology during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 16(3), 331.

Conway, C., Hammen, C., & Brennan, P. (2012). Expanding stress generation theory: test of a transdiagnostic model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(3), 754.

Davey, G. (1994). Trait factors and ratings of controllability as predictors of worrying about significant life stressors. Personality and Individual Differences, 16(3), 379–384.

Davila, J., Hammen, C., Burge, D., Paley, B., & Daley, S. (1995). Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(4), 592.

DuBois, D., Felner, R., Brand, S., Adan, A., & Evans, E. (1992). A prospective study of life stress, social support, and adaptation in early adolescence. Child Development, 63(3), 542–557.

Eschenbeck, H., Schmid, S., Schröder, I., Wasserfall, N., & Kohlmann, C.-W. (2018). Development of coping strategies from childhood to adolescence. European Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 18–30.

Eskin, M., Ertekin, K., & Demir, H. (2008). Efficacy of a problem-solving therapy for depression and suicide potential in adolescents and young adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(2), 227–245.

Ghaderi, A. (2003). Structural modeling analysis of prospective risk factors for eating disorder. Eating Behaviors, 3(4), 387–396.

Gilmore, K., & Meersand, P. (2013). Normal child and adolescent development: a psychodynamic primer. American Psychiatric Pub, Washington DC, USA.

Glyshaw, K., Cohen, L., & Towbes, L. (1989). Coping strategies and psychological distress: prospective analyses of early and middle adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17(5), 607–623.

Grant, D., Wingate, L., Rasmussen, K., Davidson, C., Slish, M., Rhoades-Kerswill, S., & Judah, M. (2013). An examination of the reciprocal relationship between avoidance coping and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(8), 878–896.

Halvarsson-Edlund, K., Sjödén, P.-O., & Lunner, K. (2008). Prediction of disturbed eating attitudes in adolescent girls: a 3-year longitudinal study of eating patterns, self-esteem and coping. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 13(2), 87–94.

Hampel, P. (2007). Brief report: coping among Austrian children and adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 30(5), 885–890.

Herman-Stabl, M., Stemmler, M., & Petersen, A. (1995). Approach and avoidant coping: implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(6), 649–665.

Hogendoorn, S., Prins, P., Boer, F., Vervoort, L., Wolters, L., Moorlag, H., & de Haan, E. (2014). Mediators of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety-disordered children and adolescents: cognition, perceived control, and coping. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(3), 486–500.

Johnson, J., Cohen, P., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. (2002). Eating disorders during adolescence and the risk for physical and mental disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(6), 545–552.

Kessler, R., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J., De Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., & Haro, J. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 168.

Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K., & Walters, E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

Klump, K. (2013). Puberty as a critical risk period for eating disorders: a review of human and animal studies. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 399–410.

Kowalenko, N., Rapee, R., Simmons, J., Wignall, A., Hoge, R., Whitefield, K., & Baillie, A. (2005). Short-term effectiveness of a school-based early intervention program for adolescent depression. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(4), 493–507.

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven de Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Department of Health, Canberra.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Lewinsohn, P., Gotlib, I., Lewinsohn, M., Seeley, J., & Allen, N. (1998). Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 109.

Lewinsohn, P., Rohde, P., Klein, D., & Seeley, J. (1999). Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(1), 56–63.

Maloney, M., McGuire, J., & Daniels, S. (1988). Reliability testing of a children’s version of the Eating Attitude Test. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(5), 541–543.

Malooly, A., Flannery, K., & Ohannessian, C. (2017). Coping mediates the association between gender and depressive symptomatology in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(2), 185–197.

Muthén, L.K., & Muthén, B.O. (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: the role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 161–187.

Nrugham, L., Holen, A., & Sund, A. (2012). Suicide attempters and repeaters: depression and coping: a prospective study of early adolescents followed up as young adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(3), 197–203.

Pantaleao, A., & Ohannessian, C. (2019). Does coping mediate the relationship between adolescent-parent communication and adolescent internalizing symptoms? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2), 479–489.

Parada, R. (2006). School bullying: psychosocial determinants and effective intervention. Australia: University of Western Sydney.

Rapee, R. (2002). The development and modification of temperamental risk for anxiety disorders: prevention of a lifetime of anxiety? Biological Psychiatry, 52(10), 947–957.

Rapee, R. (2009). Early adolescents’ perceptions of their mother’s anxious parenting as a predictor of anxiety symptoms 12 months later. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(8), 1103–1112.

Rapee, R., Oar, E., Johnco, C., Forbes, M., Fardouly, J., Magson, N., & Richardson, C. (2019). Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: a review and conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, 103501.

Rhebergen, D., Aderka, I., van der Steenstraten, I., van Balkom, A., van Oppen, P., Stek, M., & Batelaan, N. (2017). Admixture analysis of age of onset in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 47–51.

Rojo-Moreno, L., Arribas, P., Plumed, J., Gimeno, N., García-Blanco, A., Vaz-Leal, F., & Livianos, L. (2015). Prevalence and comorbidity of eating disorders among a community sample of adolescents: 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Research, 227(1), 52–57.

Salloum, A., Andel, R., Lewin, A., Johnco, C., McBride, N., & Storch, E. (2018). Family accommodation as a predictor of cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome for childhood anxiety. Families in Society, 99(1), 45–55.

Satorra, A. (2000). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans R.D.H., Pollock D.S.G., Satorra A. (eds) Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. Advanced Studies in Theoretical and Applied Econometrics, vol 36. Springer, Boston, MA.

Sawyer, M., Pfeiffer, S., & Spence, S. (2009). Life events, coping and depressive symptoms among young adolescents: a one-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117(1-2), 48–54.

Schmidt, U., & Treasure, J. (2006). Anorexia nervosa: valued and visible. A cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(3), 343–366.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Klessinger, N. (2000). Long-term effects of avoidant coping on adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(6), 617–630.

Skinner, E., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. (2007). The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 119–144.

Spence, S. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), 545–566.

Spence, S., Sheffield, J., & Donovan, C. (2003). Preventing adolescent depression: an evaluation of the problem solving for life program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 3.

Stice, E., Ragan, J., & Randall, P. (2004). Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 155.

Van Voorhees, B., Paunesku, D., Kuwabara, S., Basu, A., Gollan, J., Hankin, B., & Reinecke, M. (2008). Protective and vulnerability factors predicting new-onset depressive episode in a representative of US adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(6), 605–616.

Wells, A. (1999). A metacognitive model and therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 6(2), 86–95.

Woodward, L., & Fergusson, D. (2001). Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(9), 1086–1093.

Wright, M., Banerjee, R., Hoek, W., Rieffe, C., & Novin, S. (2010). Depression and social anxiety in children: differential links with coping strategies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(3), 405–419.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M., & Skinner, E. (2011). The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: an integrative review and critique of research. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(1), 1–17.

Zimmer‐Gembeck, M., & Skinner, E. (2016). The development of coping: implications for psychopathology and resilience. In: Cicchetti, D (Ed.) Developmental Psychopathology, Volume 4, Risk, Resilience, and Intervention, 3rd Edition, p 485. New Jersey, USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Zimmerman, M., Ramirez‐Valles, J., Zapert, K., & Maton, K. (2000). A longitudinal study of stress‐buffering effects for urban African‐American male adolescent problem behaviors and mental health. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 17–33.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants and all of the research assistants and interns who have worked on this project. In particular, we thank Justin Freeman for coordinating the data collection.

Author’s Contributions

C.E.R. participated in the design and analysis of this study and coordination and drafted the manuscript; N.R.M. participated in the design, analysis and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript; J.F. participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript; E.L.O. participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript; M.K.F. participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript; C.J.J. participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript; R.M.R. conceived this study, and participated in its design and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Australian Research Council funded this research (grant number FL150100096).

Data Sharing and Declaration

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all parents in the study, and informed assent was obtained from all preadolescents.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richardson, C.E., Magson, N.R., Fardouly, J. et al. Longitudinal Associations between Coping Strategies and Psychopathology in Pre-adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 50, 1189–1204 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01330-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01330-x