Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the trajectories of behavioral problems for a sample of predominately minority adolescents (n = 212, 91% African-American and/or Hispanic, 45% boys, 55% girls) in a large, urban school district and to determine the impact of parental and peer relationships, gender, and risk status on their development during middle and high school. Multi-level growth modeling was the primary statistical procedure used to track internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems across time. Results indicated that behavioral problems as rated by students’ teachers declined significantly for both boys and girls, a finding that is in direct contrast to previous studies of adolescent behavior. The quality of parental relationships was a strong predictor of both types of behavior whereas the quality of peer relationships predicted only internalizing behavioral symptoms. These findings suggest that behavioral trajectories may be somewhat unique for this population underscoring the need for additional research in this area. The findings also have implications for intervening with children and youth who display behavioral problems during critical developmental periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study investigated the development of behavior problems for a sample of predominately minority youth in a large, urban school district in the southeastern United States (i.e., 35% African-American, 46% Hispanic, 10% Hispanic/African-American, 10% White non-Hispanic). A primary focus of the study was to determine the impact of parent and peer relationships, gender, and risk status (i.e., not at risk and at risk for developing emotional and behavioral disorders) on the trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems for these adolescents during middle and high school. Behavior problems are typically operationalized as either internalizing or externalizing problems. Internalizing behavior problems are associated with emotional reticence, extreme shyness, withdrawal, depression, and anxiety. Externalizing problems are characterized by behaviors such as opposition and defiance, stealing, destroying property, lying, aggression, and delinquency. There is a considerable body of research that addresses the nature of these behaviors, their development in children and adolescents, and the factors that influence their development. However, research addressing behavioral problems of minority populations is relatively sparse.

The research that has focused on minority youth suggests higher levels of externalizing behaviors among African-Americans and Hispanics compared with white youth. Disproportionate numbers of school disciplinary actions and juvenile justice contacts have been reported for minority students in several studies (e.g., Kempf-Leonard 2007; Richart et al. 2003). National data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (i.e., CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System) have shown consistently higher rates of externalizing risk behaviors (e.g., carrying a weapon) for Hispanic high school students compared with white and African-American students over the last decade (CDC 2007). The CDC also has reported higher rates of internalizing behaviors (e.g., suicide attempts) for minority students. These trends have led researchers to question whether general risk factors related to poor behavioral outcomes for white youth function similarly for minority youth (O’Donnell et al. 2004). Compared with the number of studies focusing on minority youth, studies of gender differences and behavioral problems are plentiful. Generally, there has been consensus that boys evidence higher levels of externalizing behaviors than girls, particularly as young children, and that these behaviors decrease significantly from childhood through adolescence for both boys and girls (e.g., Bongers et al. 2003; Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus 1994). In contrast, studies of internalizing behavior in children and adolescents have suggested that this behavioral type is relatively stable during childhood but increases during adolescence, more so among girls than boys (e.g., Twenge and Nolen-Hoeksema 2002).

However, across studies, results have been somewhat equivocal regarding the trajectory of behavior problems due to a number of reasons including the variations in the populations studied, techniques used to measure behavior, type of informants (e.g., parents, teachers, or students reporting the behavior), age span of the sample included in the study, and duration of the study. Behavior problems of children and adolescents are assessed usually through teacher and/or parent ratings of behavior although there are exceptions (e.g., Dekovic et al. 2004 used adolescent self-reports to assess behavior problems). There seems to be a fairly strong relationship between early behavior problems and behavior problems of adolescents (e.g., Conroy and Brown 2004) as well as substantial stability of both internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors of young children (e.g., Merydith 2001) and adolescents (e.g., Dekovic et al. 2004). In our longitudinal work, teacher ratings of students’ behavior problems were found to be consistent and reliable over time, and early ratings of behavior by elementary school teachers were highly predictive of teacher ratings of students’ behavior problems in middle and high school (Montague et al. 2005, 2009). Thus, despite the methodological variations among studies, there seems to be a consensus generally that behavior problems in children are associated with later behavior problems in adolescents.

Interpersonal Relationships and Behavior

The developmental trajectories of behavior problems have been studied most recently in the context of various influences on behavior over time such as parent and peer relationships, family environments, and child temperament (e.g., Laible et al. 2004; Leve et al. 2005). Bowlby’s (1969) theory of attachment is particularly relevant because attachment during infancy more than likely influences later relationships between children and their parents and, quite possibly, their peers, during late childhood and adolescence. He posited that the attachment relationship between child and caregiver governs the ability of infants to regulate emotion and that a strong bond between the two promotes survival in infants. These attachments or bonds as theorized by Bowlby were later operationalized by Ainsworth (1989) as either secure or insecure relationships. She stipulated that a secure relationship is vital to the psychological well-being of the developing child. There is a voluminous literature on attachment relationships during infancy and early childhood whereas the research on attachment during late childhood and adolescence is comparatively limited.

Several researchers, however, have been instrumental in formulating and further developing the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA), a measure designed to investigate parent and peer relationships in late childhood and adolescence (e.g., Armsden and Greenberg 1987; Gullone and Robinson 2005; Nada Raja et al. 1992). The IPPA measures three dimensions of attachment: trust, communication, and alienation. The trust dimension assesses the extent of mutual understanding and respect between the adolescent and parent or peer, the communication dimension measures the degree and extent of verbal interaction, and the alienation dimension assesses feelings of separation and anger. Using the IPPA as well as other methods, research has suggested associations between positive adolescent–parent relationships and adolescents’ psychological well-being (Armsden and Greenberg 1987), life satisfaction (Ma and Huebner 2008; Nickerson and Nagle 2005), academic success (Bell et al. 1996), and self-efficacy (Arbona and Power 2003). Similarly, positive peer relationships have been associated with adolescents’ self-esteem (Black and McCartney 1997) and academic achievement (Holahan et al. 1996).

Gender Differences

Much of the research on adolescents’ relationships has focused on gender differences. To illustrate, Nada Raja et al. (1992), in a study of 935 adolescents in New Zealand, found that males and females did not differ in their perceived attachment to parents as measured by the IPPA. Positive parent relationships were associated with better self-perceptions of well-being, and positive perceived peer relationships did not seem to compensate for low perceived parent attachment. Dekovic et al. (2004), in a study of 212 adolescents in The Netherlands, found that externalizing behaviors increased over time for both boys and girls whereas internalizing behaviors remained stable. They detected significant individual differences in the initial level and in the rate of change for both behavioral types although no significant relationship between initial level and rate of change was detected. In this study, positive adolescent–parent relationships appeared to function as a protective factor against both externalizing and internalizing problem behavior while peer relationships appeared to influence internalizing but not externalizing behavior. That is, adolescents who reported poor relationships with peers had higher growth rates of internalizing behavior. Boys who reported poor parent relationships had the highest level of externalizing behavior; conversely, girls who reported poor parent relationships had the highest level of internalizing behavior. These studies suggest that parental and peer relationships substantially and differentially influence the behavioral trajectories for boys and girls.

Ethnic and Racial Differences

While much of the research on interpersonal relationships has focused on gender differences, there has been some interest recently in examining the impact of ethnic and racial differences on the link between parent and peer relationships and problem behaviors. For example, Choi et al. (2005) examined the relationship among risk factors for 2,055 middle school youth. These factors included low socioeconomic status (SES), neighborhood safety, parental monitoring and bonding, and youth antisocial beliefs to study racial or ethnic variation in the etiology of youth problem behaviors. They found that, although these risk factors appeared to function in the same way across racial and ethnic groups (e.g., low parental bonding was linked to higher levels of behavior problems), there appeared to be differences in the magnitude of the relationships. Interestingly, in this study, parental bonding was not linked to youth antisocial beliefs for African-American youth. However, in contrast, Lamborn and Nguyen (2004) found a direct relationship between perceptions of family support by 158 African-American adolescents and adjustment as measured by their work and school orientation. In a study examining only internalizing behaviors of 879 youth participating in the Reach for Health (RFH) project, O’Donnell et al. (2004) reported ethnic and racial differences in models of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and socio-demographic factors. In this study, females were more likely to report suicidal ideation and suicide attempts regardless of ethnicity, race, or SES. While there were no differences between white and African-American adolescents’ reports of youth suicide attempts, Hispanic youth reported two and a half times more suicide attempts, matching national trends. This research suggests that ethnicity, in addition to gender, may be an important consideration in the development of behavior problems among children and adolescents.

Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Trajectories

Another area under investigation is the nature of parent and peer relationships and the potentially different role played by each across the developmental span of adolescence. A study linking parent and peer attachment to life satisfaction with 587 middle school students in the United States found that although parent and peer relationships were positively related to life satisfaction of adolescents, parent attachment was the stronger predictor (Ma and Huebner 2008). No differences between boys and girls were found for levels of parent attachment, but girls reported higher levels of peer attachment. The mixed findings, in terms of the strength of the relationship between parent and peer attachment and problem behaviors, may be related to the shifting importance from parent to peer relationships for adolescents as they mature (Michiels et al. 2008). McDowell and Parke (2009) examined the relationship between parent–child interactions and later measures of social competence and social acceptance from peers and noted the importance of examining these relationships in the context of changing developmental pathways, specifically during middle childhood and adolescence as youth “experience a significant shift from parent-dominated to more peer-oriented interactions” (p. 224). Research also has suggested that the strength of parental attachment may have an indirect (negative) effect on youths’ likelihood to develop peer relationships with deviant or delinquent peers who are engaged in externalizing and risk-taking behaviors (Ingram et al. 2007). This type of research helps to illuminate the subtle and differential influences of parents and peers on the development of behavioral problems in children and adolescents.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study seeks to add to the growing discussion of the influence of adolescents’ interpersonal relationships on their behavior. We focused specifically on the development of internalizing and externalizing behaviors in this school-based sample of predominately minority youth and the influence of parent and peer relationships, gender, and risk status on the initial level and growth of these behaviors. Two research questions guided this study: (a) What is the initial status and growth over time of internalizing and externalizing behaviors of adolescents as rated by their middle and high school teachers? and (b) Are there differences in the growth trajectories of adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors as a function of their perceptions of relationships with their parents and peers, gender, and/or risk status (i.e., not at risk or at risk students)?

Based on the literature, we hypothesized that over time boys would evidence higher levels of externalizing behaviors than girls and that girls would display higher levels of internalizing behaviors than boys. We also thought that externalizing behavior would decrease whereas internalizing behavior would remain relatively stable as the research suggests. Additionally, we hypothesized that positive parental relationships would predict lower levels of both types of behavior problems and positive peer relationships would predict lower levels of internalizing behavior only. Finally, we thought that gender would have a differential association with both types of behavior initially and over time. Although, as discussed earlier, the majority of the research has been conducted with non-minority samples of students, we nonetheless anticipated that these hypotheses would hold true for our sample of predominately minority adolescents in urban schools.

Method

Participants

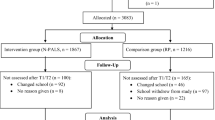

This study was conducted in the context of a longitudinal study (2001–2007) of students identified as at risk for developing emotional and behavioral disorders. The at risk students were identified in a previous 4-year project (1994–1998) that was initiated by screening 628 students in 24 kindergarten and first-grade classrooms at two schools in a large, urban school district. One school was composed primarily of Hispanic students (79%) and, the other, African-American students (72%). The Systematic Screening for Behavior Disorders (SSBD; Walker and Severson 1992) was used to screen students. The SSBD utilizes a three-stage process for identifying youngsters as at risk for developing emotional and behavioral problems: (a) teacher nominations, (b) teacher ratings of adaptive and maladaptive behavior, and (c) classroom and playground observations. Students nominated by their teacher as displaying internalizing or externalizing behaviors but do not meet the cut-off criterion on the teacher rating scale are identified as at risk at Stage One. If students meet the cut-off criterion on the rating scale but do not meet the cut-off criteria for the observations, they are identified as at risk at Stage Two. Students meeting all criteria at all three stages are identified as at risk at Stage Three. Based on the SSBD multiple-stage process, 206 (33%) students were identified as at risk for developing emotional and behavioral problems: 115 (18%) were at Stage One, 63 (10%) at Stage Two, and 28 (5%) at Stage Three.

For the longitudinal study, the original sample of at risk students (n = 206) was located through the school district’s database when students were in early middle school. Of this original sample, 100 students consented to participate, 37 declined participation, 26 did not return consent forms, and 43 could not be located. The not at risk students (n = 112) were recruited from general education language arts classes in secondary school. The criterion for participation as a not at risk student was no history of referral to special education. Thirty-three students in the at risk group (15%) were receiving special education services, which is about the percentage of students placed in special education in the general school-aged population in the United States. The demographics for the participants (n = 212) and non-participants (n = 106) are presented in Table 1.

Students were followed longitudinally throughout middle and high school (see section “Procedures”). It should be noted that longitudinal studies are characterized by an n that changes over time with respect to the analyses due to recruitment of participants at the beginning of the study and attrition of participants over time. This could be viewed as a potential limitation when interpreting results. Our analyses, however, statistically account for the missing data and attrition of participants (see Enders et al. 2006).

Instrumentation

Two instruments were utilized in this study. The Behavioral Assessment System for Children-Teacher Rating Scale (BASC-TRS; Reynolds and Kamphaus 1998) was used to determine the level of internalizing and externalizing behavioral symptoms in the adolescents, and the short version of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA: Armsden and Greenberg 1987; Nada Raja et al. 1992) was used to assess the level of students’ perception of attachment to their parents and peers.

Behavioral Symptoms

The BASC-TRS is appropriate for adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age and provides a broad composite score, the Behavioral Symptoms Index (BSI) and five composite scores: Internalizing Problems, Externalizing Problems, School Problems, Other Problems, and Adaptive Skills. The Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems composite scores were used to assess problem behaviors in this study. The Internalizing Problems composite consists of the Anxiety, Depression, and Somatization scales. The Externalizing Problems composite consists of the Hyperactivity, Aggression, and Conduct Problems scales. Reported coefficient alphas for these composite scores were .94 and .97, respectively.

Parental and Peer Relationships

The short version of the IPPA (for a complete description of the development of the instrument, see Nada Raja et al. 1992) has 24 items and was a modification of the original 53-item IPPA (Armsden and Greenberg 1987). Nada Raja et al. (1992) divided the 24 IPPA items equally between the parent attachment scale and the peer attachment scale. Responses to the items are on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = Almost never or never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Often, and 4 = Almost always or always). Eleven items are reverse-coded. The IPPA measures the quality of communication as well as degree of trust and alienation in adolescent–parent relationships or adolescent–peer relationships with items such as the following: “I tell my parents about my problems and troubles” or “My friends listen to what I have to say.” Each scale score (parent and peer) was derived by summing the appropriate Communication and Trust subscales and then subtracting the respective Alienation subscale (see Armsden and Greenberg 1987, for details). Cronbach’s alphas for the IPPA scores in our study were .83 for the Parent Attachment scale and .82 for the Peer Attachment scale.

Procedures

For the present study, beginning in middle school, in the fall and spring of each year with at least a 6-month interval, the BASC-TRS was completed by students’ content area teachers for 10 Waves of data (Wave 1, n = 74; Wave 2, n = 144; Wave 3, n = 157; Wave 4, n = 176; Wave 5, n = 166; Wave 6, n = 169; Wave 7, n = 151; Wave 8, n = 148; Wave 9, n = 137; Wave 10, n = 111). The IPPA was administered individually to students in school as part of the Wave 6 assessment after students transitioned to high school. Students were given a $25 gift card for each assessment, and teachers were given a $10 gift card for each BASC-TRS they completed.

Methods

Growth Curve Models

The development of internalizing and externalizing behavioral symptoms (as measured by the BASC-TRS composite scores) was examined using a series of multilevel growth models. The multilevel growth model views repeated measures (level-1) as nested within children (level-2). The level-1 equation expresses change for child i as a function of age using the following model.

where Y ti is the outcome score (e.g., externalizing symptoms) for child i at age t, β0i is the intercept (i.e., the predicted outcome score at age 16) for child i, β1i quantifies the yearly change in child i’s outcome, and r ti is a level-1 residual that captures deviations between the observed data and the idealized linear growth trajectory for child i. Note that age was centered at 16, so the intercept is interpreted as the predicted outcome score at that point in the developmental process.

The level-2 (i.e., child-level) equations describe differences across individuals as follows.

where γ00 is the mean intercept (i.e., average outcome score at age 16), γ10 is the average yearly growth rate, and u 0i and u 1i are residuals that capture individual differences in the intercepts and slopes, respectively. The basic linear model described above yields estimates of the average growth trajectory, variance estimates for the intercepts and slopes, and a covariance that describes the association between the intercepts and slopes. As noted previously, the primary thrust of the study was to determine whether development is influenced by the quality of relationships with parents and peers, gender, and risk status. This is readily accomplished by adding these variables as predictors in the level-2 equations shown above. A growth curve analysis is ideally suited for this study because it allows for missing data (as noted elsewhere, the multiple cohort design produced missing data by design) and because it provides a description of individual differences in the growth process. In contrast, repeated measures ANOVA requires complete data and assumes that individuals share a common growth trajectory. All of the growth curve models were estimated using the Mixed procedure in SPSS 16 (Peugh and Enders 2005), and all of the level-2 predictor variables were centered at their grand means (Enders and Tofighi 2007).

A note should be made concerning missing data handling. This study used a multiple cohort design, such that each data collection wave included children at different grade levels (and thus ages). As a result, many of the children were not assessed at every point along the developmental continuum (e.g., children who were 14 years of age at the first wave were never assessed at age 13). This type of missing data is a function of the research design and is missing completely at random, by definition. In other situations, attrition occurred for reasons that were beyond our control. Considering all sources of missing data, 83% of the participants contributed at least four waves of internalizing and externalizing data to the analysis, and approximately 61% of the children had seven or more observations. In addition, 33 (roughly 16%) of the participants contributed their final observation prior to the administration of the IPPA at Wave 6 (the transition to high school). The inclusion or exclusion of these cases had virtually no bearing on the growth modeling parameter estimates (e.g., the growth model estimates in Table 2 were only affected at the second decimal). In the subsequent growth modeling analyses, missing values were handled using the maximum likelihood estimation, which is one of the missing data handling procedures currently recommended in the methodological literature (Enders et al. 2006; Schafer and Graham 2001).

Results

Unconditional Growth Models

The analysis began by exploring the shape of the developmental trajectories using a series of unconditional growth models with no predictor variables. Linear and quadratic growth models were fit to the data, and the relative fit of these models was compared using nested model likelihood ratio tests. For externalizing symptoms, the quadratic model provided no improvement over the linear model, χ2(1) = .10, p = .75. For internalizing behavior, the quadratic model resulted in a slight improvement in fit over the linear model, χ2(1) = 5.54, p = .02. A visual inspection of the average growth trajectory indicated very slight curvature at ages 12 and 19, and the shape of the trajectory was essentially linear between the ages of 13 and 18. Because there were relatively few observations at ages 12 and 19, and because the shape of the average curve was, for all intents and purposes, linear, the quadratic model was abandoned.

The linear growth model parameter estimates are given in Table 2. As seen in the table, a statistically significant decrease in internalizing and externalizing behavior was observed, such that internalizing scores decreased by 1.35 points per year, on average, and the yearly decrease in externalizing scores was approximately 1 point. In addition, the variance estimates indicated that the growth trajectories varied substantially across individuals. Considering internalizing behavior, the standard deviation of the intercepts and slopes (i.e., the square root of the variance estimates listed in Table 1) was 7.82 and 2.04, respectively. If one defines a plausible range of values as plus or minus two standard deviation units around the mean, this suggests that individual intercept values ranged between 30.50 and 61.78, and slope values ranged between −5.42 and 2.72. The heterogeneity in the intercepts and slopes indicated that children varied rather dramatically in their mean levels of reported symptoms, and that some individuals experienced a relatively rapid decrease in internalizing symptoms, while others increased. The same conclusions held for externalizing symptoms; substantial variation existed in the intercepts and slopes, and the standard deviations were 7.43 and 1.96, respectively. Finally, note that there was a significant covariance between the intercepts and slopes for both variables. For internalizing behavior, the covariance was negative (converted to a correlation, the association was r = −.20), suggesting that higher levels of internalizing behavior at age 16 were associated with more rapid declines in problem behavior. For externalizing behavior, the covariance was positive (r = .30), indicating that higher scores at age 16 were associated with less rapid declines (and potential gains) in problem behavior.

Conditional Growth Models

Next, growth models were estimated in order to determine whether individual differences in the growth trajectories could be explained by the perceived quality of relationships with parents and peers, gender, and risk status. It should be noted that a three-category risk status variable (no risk, at risk with no special education placement, and at risk with special education placement) was used first in the models. However, special education placement was non-significant, so the 2-category variable (not at risk, at risk) was used. All of the predictor variables were centered at the grand mean (Enders and Tofighi 2007) and were subsequently added to the level-2 equations for the intercept and slope.Footnote 1 The parameter estimates from the analyses are given in Table 3. Because the predictors were centered, the mean intercept and slope values in Table 3 were virtually identical to those in Table 2.

Internalizing Behavior Trajectories

As seen in Table 3, both quality of parental relationships and peer relationships were significant predictors of internalizing symptoms at age 16 (i.e., the intercepts), but none of the predictors was associated with individual differences in growth rates. As seen in the table, the partial regression coefficients were negative, suggesting that more positive relationships were associated with lower levels of internalizing symptoms. Both the parental and peer relationship scales were computed by averaging responses to 12 four-point Likert items. The standard deviations of the resulting scale scores were approximately .50, so the regression coefficients in Table 3 (γ = −5.34 and −4.90) can be interpreted as the expected change in internalizing scores for a two standard deviation (i.e., one point) increase in relationship quality.

Externalizing Behavior Trajectories

The results from the externalizing growth model were somewhat different from the internalizing analysis. Specifically, gender and quality of parental relationships influenced the level of externalizing reports at age 16, but no other predictors were significantly associated with the intercepts or growth trajectories. Consistent with the internalizing results, the regression coefficient for parental attachment was negative, suggesting that more positive parental relationships were associated with lower levels of teachers’ perceptions of students’ externalizing behavioral symptoms. The γ = −2.39 coefficient reflects the expected decrease associated with roughly a two standard deviation increase in parental relationship quality. The gender coefficient (γ = −2.50) reflects the average amount by which males and females differed at age 16, with teachers reporting higher levels of externalizing behavior for females. This finding was unexpected in light of previous research that indicates that boys typically display higher levels of externalizing behavior than girls.

Gender Differences

The final set of models assessed whether the role of relationship quality as a protective mechanism functioned differently for males and females. To do so, product terms between gender and the peer and parental relationship variables were added to the level-2 intercept and slope equations.Footnote 2 No further tables are used to convey the results, because the interaction effects were not significant, and the results were quite similar to those presented previously.

Consistent with the previous results, parental and peer relationship quality were significant predictors of the internalizing behavior intercept (p < .001). The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the average internalizing growth curve for boys and girls with high and low quality peer relationships defined by one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively. Parental relationship quality and risk status were held constant at the mean. As is evident in the figure, positive peer relationships were associated with lower symptom reports, as the lowest growth curves were associated with high quality relationships. Note that the male growth curves are not parallel, suggesting that peer relationship quality was differentially predictive of growth rates for males and females, but this effect was not significant (p = .23).

The lower panel of Fig. 1 shows the average internalizing growth curves for boys and girls with high and low quality parental relationships, defined by one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively. In this case, peer relationship quality and risk status were held constant at the mean. Positive parental relationships were associated with lower symptom reports, as evidenced by the fact that the lowest growth curves are associated with high quality relationships. Note that the vertical distance between the male growth curves is noticeably less than that for females, suggesting that parental quality was a stronger predictor for females than it was for males. This interaction was not significant, although it neared significance (p = .06).

The externalizing results were quite similar to those presented earlier, with parental relationship quality (p = .02) and gender (p = .06) being the most salient predictors of symptom reports at age 16. Figure 2 shows the average externalizing growth curve for boys and girls with high and low quality parental relationships, with peer relationship quality and risk status held constant at the mean. High and low quality was defined by one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively. The impact of parental relationship quality is evidenced by the fact that, within a given gender group, the lower growth curve was associated with higher quality relationships. Although gender was non-significant (p = .06), this effect is evident in that the female growth curves are higher overall than the male curves.

Discussion

In this study we examined the trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems of a primarily minority sample of adolescents and the influence of adolescent–parent and adolescent–peer relationships, gender, and risk status (i.e., at risk status based on behavioral screening in elementary school) on initial levels of behavior and growth over time. First, we explored the developmental trajectories using unconditional growth models with no predictor variables. Second, we estimated growth of behavioral problems to determine if growth in middle and high school was influenced by the quality of these adolescents’ parental and peer relationships, gender, and/or risk status. Several of our findings were at variance with those of other researchers and are discussed in the context of these previous studies of adolescent behavior.

Behavioral Trajectories

During middle and high school, the adolescents in our study significantly decreased in levels of both internalizing and externalizing behavior as rated by teachers, but their initial levels of behavior problems and rates of decline over time were highly variable. The significant decrease in both types of behavior problems was not expected. That is, we hypothesized a decrease in externalizing behaviors as they typically decline during adolescence, particularly in later adolescence. However, we expected internalizing behaviors to remain relatively stable. The significant individual variation and co-variance of initial status and growth was expected and understandable given the composition of our sample. That is, about half of the adolescents had been identified as at some degree of risk for developing emotional and behavioral problems when they were in primary school and half were not at risk as determined by school records (i.e., no prior referral for psychoeducational evaluation). Furthermore, initial screening occurred in two low-income, minority schools. When students were relocated in middle school, they had dispersed to 42 different schools indicating high mobility rates among students. Differences in family stability and school and community conditions may have contributed to the significant variability of behavior problems in the group. Depending on contextual conditions, early symptoms of behavioral problems may be attenuated or exacerbated over time as a result of exposure to various protective or risk factors (e.g., Youngblade et al. 2007). Thus, the substantial variation in the initial level and decline of problem behaviors in our sample may be attributable somewhat to the nature of the adolescents in our study as well as to the contextual conditions they experienced over their school years. Dekovic et al. (2004) also found significant variability initially and over time in their study, although they did not find a relationship between the two. It may be that adolescents do vary substantially in behavior and that this variation should be expected in large groups of adolescents. Moreover, we found that higher initial levels of internalizing behavior were associated with more rapid declines in contrast with externalizing behavior for which higher levels were associated with less rapid declines suggesting that this behavioral type may be more enduring for adolescents.

Our findings relative to the trajectories of problem behavior, for the most part, contrast with those of other researchers. For example, several earlier studies found that internalizing behavior remained relatively stable over time (e.g., Dekovic et al. 2004; Holsen et al. 2000). Although stability of externalizing behavior has varied to some degree across studies, Dekovic et al. (2004) found an increase in externalizing behavior in their sample of adolescents who self-reported behavioral symptoms annually for 3 years. It should be noted that the problem behavior levels in our sample of students were relatively high initially (i.e., in middle school) (Montague et al. 2005, 2009). Because the at risk students were in the majority during the early waves of data collection, the initial levels of behavior problems may have been somewhat elevated. The not at risk adolescents were recruited and combined with the at risk students during early high school. Nonetheless, the variability among students was evident across the subsequent waves as the problem behaviors, as rated by teachers, decreased from middle school through high school.

Results from our other analyses corroborate these findings; that is, as problem behaviors declined, students’ self-ratings of depressive symptomology also declined while their perceptions of self-concept improved over time, but again with substantial individual variation (Montague et al. 2008). Another explanation for the decline in behavior problems in our sample of adolescents has to do with when these behavioral patterns emerge for different populations. In other words, problem behaviors for our sample of adolescents may have emerged earlier than is typical, increased at a higher rate during childhood, peaked in early adolescence, and then decreased subsequently in high school. There are state data (e.g., Florida Department of Education 2006) suggesting this may be the case as it relates particularly to externalizing behavior trajectories for minority youth. In Florida, the highest disproportionality rates of disciplinary action for minority students have been reported in elementary school with rates decreasing continuously through middle and high school. Specifically, minority youth are almost five times as likely to be disciplined for “disruptive behavior” in elementary school than white youth (Center for Criminology and Public Policy research 2007). Additional research studies that follow culturally diverse groups of students across elementary, middle, and high school years are needed to explain further these long-term behavioral trajectories.

Interpersonal Relationships and Behavior Trajectories

When predictor variables were introduced, we found that the quality of both parental and peer relationships predicted the initial level of internalizing behavioral symptoms but not growth. As expected, more positive relationships with parents and peers were associated with lower levels of internalizing symptoms. The quality of relationships differentially predicted the growth rates for males and females, but the effect for gender was not significant. However, there was a trend for girls with low quality peer relationships to have higher initial levels of internalizing behavior than girls with high quality peer relationships and also boys with both high and low quality relationships. This finding is consistent with previous research that has demonstrated a relationship between low quality peer relationships and high levels of internalizing behaviors and depression among adolescent girls (Fotti et al. 2006). In general, our results with respect to gender and internalizing behavior support others’ findings that positive peer relationships may be a protective factor for youth (Dekovic et al. 2004). Additionally, there was also a trend for girls with positive parental relationships to have lower internalizing symptom ratings compared with the other groups.

The growth pattern for externalizing behaviors for these adolescents was somewhat different. The only significant predictor was the quality of parental relationships, and it predicted initial levels of externalizing behavior only. In keeping with the results for internalizing behavioral symptoms, higher quality parental relationships were associated with lower initial levels of externalizing behavioral symptoms. Again, gender differences were close to significant with girls quite unexpectedly evidencing a higher level of externalizing symptoms than boys. This finding may have something to do with the characteristics of the adolescents in our sample (i.e., low-income, minority, urban youth). Research has fairly consistently reported higher rates of externalizing behavior problems for boys (e.g., Smetana et al. 2002). One relatively recent study, however, lends some credibility to our results by also finding a greater increase in externalizing behavior problems (specifically, aggression) for girls than boys in a similar minority sample (Graber et al. 2006).

Limitations

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, the adolescents in our study represented an urban, school-based sample with varying levels of risk for developing behavioral and emotional problems. Moreover, the adolescents were from primarily minority and low socio-economic families. Thus, the generalizability of the findings is limited to similar populations. The composition of the sample must be considered when interpreting results and comparing findings across studies. For example, the sample in the Dekovic et al. (2004) study was a “community (nonclinical) sample of adolescents… from intact, middle-class families” in The Netherlands (p. 10). Further, in their study, “very few adolescents…(self-)reported high levels of problem behavior” (p. 10). Second, unlike the research that uses self-reports or parent reports of behavior, the behavioral symptoms of adolescents in our study were assessed using ratings of different middle and high school teachers across the 6 years of the study. Although the reliability and consistency of teacher ratings in our longitudinal work was established through middle school (Montague et al. 2005), this may still be regarded as a shortcoming of the study. Third, the IPPA was administered only once for the purpose of this study as a predictor of behavioral problems. As Dekovic et al. (2004) noted, the quality of interpersonal relationships may change over time and have differential effects on behavior. Future research should investigate the relationship between changes in students’ perceptions of their parental and peer relationships and the development of problem behaviors.

Regardless of the limitations, the present study contributes to the accumulating research that seeks to understand and explain behavioral development in adolescents. Our hypotheses were formulated in light of previous research and were realized to some extent. That is, the quality of adolescent–parental relationships was a strong predictor of the initial levels of both internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Adolescent–peer relationships also predicted initial levels of internalizing behavior, and, although not significant, there was a trend toward differential growth rates of both behavioral types for boys and girls. Finally, there was clearly a trend suggesting that the quality of parental relationships was a stronger predictor for internalizing behavior of girls.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that both internalizing and externalizing behavioral symptoms as rated by middle and high school teachers declined significantly over 6 years for both boys and girls. Risk status did not predict either initial level or growth of behavioral problems. However, the quality of both parental and peer relationships strongly predicted initial levels of internalizing problem behaviors, and there was some evidence that girls with low quality peer relationships may be at risk for higher levels of internalizing behaviors. Specifically, as hypothesized and consistent with previous research (e.g., Dekovic et al. 2004), high quality parental relationships predicted lower levels of both types of problem behaviors, high quality peer relationships predicted lower levels of internalizing behavior, and quality of peer relationships was not predictive of externalizing behavior. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution as Kraeger (2004) has noted that “…low peer attachment in and of itself fails to increase…delinquency” (p. 351). Research has demonstrated a direct link between attachment to delinquent peers and externalizing behaviors. Thus, peer relationships with a deviant peer group may actually be perceived in a positive light by adolescents and, thus, may be associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors. As research has consistently shown, relationships with peers with behavior problems can be a strong predictor of adolescent problem behaviors even after controlling for parental relationships (Carlo et al. 2007; Crosnoe et al. 2002; Ingram et al. 2007). Thus, to an extent our findings support previous research but also differ in important ways relative to the development of both types of behavioral symptoms. We found that the quality of parental relationships predicted initial levels of both internalizing and externalizing behaviors, but, in contrast to other studies, found that both types of problem behaviors decreased significantly over time rather than increasing or remaining at the same relative level. Also, unexpectedly, we found a trend for higher levels of externalizing symptoms in girls.

To conclude, the aim of this study was to further our understanding of behavioral development in adolescents and the factors that promote or temper their development. Our findings extend research with minority youth that focuses on the relationships between interpersonal relationships and behavioral problems and suggest that the trajectories of behavioral problems for minority, urban youth may be unique compared with other populations. That is, behavioral problems for these children and adolescents may manifest relatively early, increase through early adolescence, and then decline over time. Our ultimate research goal, however, is to provide insight into the development of behavioral problems that will guide the provision of appropriate and ameliorative supports to culturally diverse children and adolescents during critical developmental periods. The results clearly have implications for providing early and ongoing intervention for children with behavioral problems. An important focus of prevention and intervention efforts should be to develop high quality relationships between children and parents/caregivers because there is strong evidence that positive adolescent–parent relationships, as perceived by adolescents, consistently predict lower levels of behavior problems.

Notes

Although it may seem unnatural to center binary predictor variables, the effect of doing so is the same as in the continuous case (Enders and Tofighi in press). Because the centered variables are level-2 predictors, only the value of the intercept is affected by centering. The rationale for centering all level-2 predictors is that the estimates of the mean intercept and slope are roughly the same across analyses, and are unaffected by the inclusion of predictor variables.

Interaction terms between relationship quality and risk status were also explored, but these effects were non-significant. Because these interactions were of less substantive interest, they were removed from the final analysis model.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44, 709–716.

Arbona, C., & Power, T. G. (2003). Parental attachment, self-esteem, and antisocial behaviors among African-American, European American, and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 40–51.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–453.

Bell, K. L., Allen, J. P., Hauser, S. T., & O’Conner, T. G. (1996). Family factors and young adult transitions: Educational attainment and occupational prestige. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Peterson (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence: Interperson domains & context (pp. 346–366). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Black, K. A., & McCartney, K. (1997). Adolescent females’ security with parents predicts the quality of peer interactions. Social Development, 6, 91–110.

Bongers, I. L., Koot, H. M., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 179–192.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic.

Carlo, G., Crockett, L. J., Randall, B. A., & Roesch, S. C. (2007). A latent growth curve analysis of prosocial behavior among rural adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 301–324.

Center for Criminology and Public Policy Research: Florida State University. (2007). The safe and drug-free schools and communities quality data management project. Retrieved on June 9, 2009, from http://www.criminologycenter.fsu.edu/sdfs/reports-publications.php.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Youth risk behavior surveillance system. Retrieved on June 7, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/trends.htm.

Choi, Y., Harachi, T., Gillmore, M., & Catalano, R. (2005). Applicability of the social development model to urban ethnic minority youth: Examining the relationship between external constraints, family socialization, and problem behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15(4), 505–534.

Conroy, M. A., & Brown, W. H. (2004). Early identification, prevention, and early intervention with young children at-risk for emotional/behavioral disorders: Issues, trends, and a call for action. Behavioral Disorders, 29, 224–236.

Crosnoe, R., Glasgow Erickson, K., & Dornbusch, S. (2002). Protective functions of family relationships and school factors on the deviant behavior of adolescent boys and girls. Youth & Society, 33, 515–544.

Dekovic, M., Buist, K. L., & Reitz, E. (2004). Stability and changes in problem behavior during adolescence: Latent growth analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 1–12.

Enders, C., Dietz, S., Montague, M., & Dixon, J. (2006). Modern alternatives for dealing with missing data in special education research. In T. E. Scruggs & M. A. Mastropieri (Eds.), Advances in learning and behavioral disorders (Vol. 19, pp. 101–130). New York: Elsevier.

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12, 121–138.

Florida Department of Education. (2006). Statewide school environmental safety incident report. Tallahassee, Fl: Florida Department of Education.

Fotti, S., Katz, L., Afifi, T., & Cox, B. (2006). The associations between peer and parental relationships and suicidal behaviours in early adolescents. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 698–709.

Graber, J., Nichols, T., Lynne, S., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Botvin, G. (2006). A longitudinal examination of family, friend, and media influences on competent versus problem behaviors among urban minority youth. Applied Developmental Science, 10(2), 75–85.

Gullone, E., & Robinson, K. (2005). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment—Revised (IPPA-R) for children: A psychometric investigation. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 12, 67–79.

Holahan, C. J., Valentiner, D. P., & Moos, R. H. (1996). Parental support, coping strategies, and psychological adjustment during the transition to college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 633–648.

Holsen, I., Kraft, P., & Vitterso, J. (2000). Stability in depressed mood in adolescence: Results from a 6-year longitudinal panel study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 61–78.

Ingram, J., Patchin, J., Huebner, B., McCluskey, J., & Bynum, T. (2007). Parents, friends, and serious delinquency. Criminal Justice Review, 32, 380–400.

Kempf-Leonard, K. (2007). Minority youths and juvenile justice. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 5(1), 71–87.

Kraeger, D. A. (2004). Strangers in the halls: Isolation and delinquency in school networks. Social Forces, 83, 351–390.

Laible, D. J., Carlo, G., & Roesch, S. C. (2004). Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviours. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 703–716.

Lamborn, S., & Nguyen, D. (2004). African American adolescents’ perceptions of family interactions: Kinship support, parent–child relationships, and teen adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(6), 547–558.

Leve, L. D., Kim, H. K., & Pears, K. C. (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 505–520.

Ma, C. Q., & Huebner, E. S. (2008). Attachment relationships and adolescents’ life satisfaction: Some relationships matter more to girls than boys. Psychology in the Schools, 45, 177–186.

McDowell, D. J., & Parke, R. D. (2009). Parental correlates of children’s peer relations: An empirical test of a tripartite model. Developmental Psychology, 45, 224–234.

Merydith, S. P. (2001). Temporal stability and convergent validity of the behavior assessment system for children. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 253–265.

Michiels, D., Grietens, H., Onghena, P., & Kuppens, S. (2008). Parent–child interactions and relational aggression in peer relationships. Developmental Review, 28, 522–540.

Montague, M., Enders, C., & Castro, M. (2005). Academic and behavioral outcomes for students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 30, 87–96.

Montague, M., Enders, C., Cavendish, W., Dietz, S., & Castro, M. (2009). Academic and behavioral trajectories for at risk adolescents (Manuscript submitted for publication).

Montague, M., Enders, C., Dietz, S., Morrison, W., & Dixon, J. (2008). A longitudinal study of depressive symptomology and self-concept in adolescents. Journal of Special Education, 42, 67–78.

Nada Raja, S., McGee, R., & Stanton, W. R. (1992). Perceived attachments to parents and peers and psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21, 471–485.

Nickerson, A., & Nagle, R. J. (2005). Parent and peer attachment in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 223–249.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Girgus, J. S. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during depression. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 424–443.

O’Donnell, L., O’Donnell, C., Wardlaw, D., & Stueve, A. (2004). Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(1/2), 37–49.

Peugh, J. L., & Enders, C. K. (2005). Using the SPSS Mixed procedure to fit hierarchical linear and growth trajectory models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 811–835.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (1998). Behavior assessment for children. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc.

Richart, D., Brooks, K., & Soler, M. (2003). Unintended consequences: The impact of “zero tolerance” and other exclusionary policies on Kentucky students. Building Blocks for Youth Executive Summary. Retrieved November 22, 2004, from www.buildingblocksforyouth.org.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2001). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177.

Smetana, J., Crean, H., & Daddis, C. (2002). Family processes and problem behaviors in middle-class African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(2), 275–304.

Twenge, J. M., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2002). Age, gender, race, socio-economic status, and birth cohort difference on the Children’s Depression Inventory: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 578–588.

Walker, H. M., & Severson, H. H. (1992). Systematic screening for behavior disorders. Longmont, CO: Sopris West.

Youngblade, L. M., Theokas, C., Schulenberg, J., Curry, L., Huang, I. C., & Novak, M. (2007). Risk and protective factors in families, schools, and communities: A contextual model of positive youth development in adolescence. Pediatrics, 119, 547–553.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant No. H324C010091 from the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP), U.S. Department of Education. Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent the position of the U.S. Department of Education. The authors are grateful to the school personnel and students in the Miami-Dade County Public Schools for their cooperation and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montague, M., Cavendish, W., Enders, C. et al. Interpersonal Relationships and the Development of Behavior Problems in Adolescents in Urban Schools: A Longitudinal Study. J Youth Adolescence 39, 646–657 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9440-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9440-x