Abstract

Religious and spiritual practices have been identified as a main source of mental health support for Latinxs to improve overall health and well-being. This qualitative secondary data analysis sought to elucidate how Mexican patients and family members engaged in religious and spiritual practices to help alleviate patients’ experiences of mental illness. Three main findings are discussed: (1) positive religious coping such as entrusting God with one’s suffering, consejos (i.e., emotional support and advice giving), and positive social supports through religious communities; (2) negative religious coping such as harmful views of God as punishing; and (3) indigenous healing practices such as engagement with curanderos (medicine doctor) and limpias (i.e., herb-based cleanses). The authors discuss these findings in the context of tensions between culturally sanctioned healing and the perception of psychotherapeutic effectiveness reported by Mexican patients and their family members. The authors also provide future directions for incorporating patients’ religious and spiritual practices into multiculturally competent treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Across Latin America, spiritual and religious beliefs and practices are influenced by both indigenous healing and Christian-based systems that were mutually influenced, shaped, and adopted through the process of colonization (Baez & Hernandez, 2001; Lámbarri Rodríguez et al., 2012; Lujan & Campbell, 2006). Spirituality includes beliefs in personal and ancestral spirits, a connection to animal and ecological beings, and a general connection to the divine and the cosmos (Comas-Diaz, 2006; Hovey et al., 2014; Muñoz & Mendelson, 2005; Padilla & Salgado de Snyder, 1988; Tree, 2001). In Mexico, curanderismo is a spiritual healing practice that emerged from the practices of pre-Columbian Aztec and other civilizations flourishing at the time of colonization (Applewhite, 1996). Curanderos/as are community-based healers—medicine doctors who practice traditional healing methods that include yerberos (herbalists), hueseros (bone therapists), sobadores (muscle therapists), and parteras (midwives; Applewhite, 1996). Curanderos/as infuse pre-Columbian values and beliefs with religious artifacts, usually from Catholicism, adopted during the colonization process to treat a wide variety of ailments, including mental and emotional well-being (Lámbarri Rodríguez et al., 2012).

In contrast, religiosity is a broader term characterized by one’s personal connection to a transcendent being, often distinguished by active and organized religious practices (Cervantes & Parham, 2005; Hill & Pargament, 2003; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013). Religion plays a central role for Latinxs (Lujan & Campbell, 2006) and recent estimates indicate that between 80 to 95% of Mexican-origin Latinxs in the USA are religiously affiliated or participate in religious activities (Noyola et al., 2020). Religiosity provides an understanding of a patient’s cultural background and value orientation by offering a set of morals and guidelines by which Latinxs can cope with life stressors such as migration, financial strain, and housing insecurity, and guide their behaviors toward wellness to alleviate psychological distress (Bou-Yong Rhi, 2001; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013, 2018b; Comas-Diaz, 2006; Joshi & Kumari, 2011; Keller, 2002; Moreno & Noyola et al., 2020). Generally,Footnote 1 religious engagement has been found to improve health and mental health, unless it prevents engagement in health-seeking practices (Chatters, 2000; Garcia et al., 2013; George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002; Koenig et al., 1999; Miller & Thoresen, 1999; Pargament, 1997; Patrick & Kinney, 2003).

Types of Religious Coping

Pargament and colleagues (1998) distinguish between positive and negative religious coping. Positive religious coping is characterized by a secure spiritual connection with others and benevolent religious beliefs in forgiveness, that God loves and cares for people, and that God offers strength during times of adversity (Hovey et al., 2014; Koerner et al., 2013; Pargament et al., 1998). Negative religious coping includes beliefs that God is punishing, has abandoned the person, that adversity is a result of sin or demonic forces, and includes having contentious relationships with clergy, chaplains, or other religiously affiliated members (Hovey et al., 2014; Mueller et al., 2001; Pargament et al., 1998). People who report more negative religious coping state higher emotional distress including depression and poorer quality of life (Da Silva et al., 2017; Pargament et al., 1998).

Religious Coping in Latinxs

Previous studies have documented higher levels of psychological distress in Latinxs who engage in negative religious coping (Da Silva et al., 2017; Herrera et al., 2009). For example, Caplan (2019) reported that Latinxs believed depression could be onset by a “lack of faith” and a belief that God is punishing the person. A study on Latina women who were survivors of abuse reported that the belief that God was punishing increased symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to increased feelings of self-blame and guilt (Cuevas et al., 2015).

Yet religious beliefs could serve as a protective factor, promote healing practices and alleviate the experience of mental illness for Latinxs. Prayer can be a positive coping strategy that provides an action-oriented response to life stressors, particularly for issues related to health (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004; Caplan, 2019; Krause & Hayward, 2014; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013). Similarly, “making mandas,” performing a religious act to grant a request, increased a sense of control in older Mexican Americans that improved health (Krause & Bastida, 2012). In rural Mexican communities, people reported frequent participation in religious rituals due to a strong belief in the curative power of God (Salgado-de-Snyder et al., 2003). Other Latinxs reported that “having faith in God” and not dwelling on negative emotions could cure mental illness (Caplan, 2019). In a study on Latinx immigrants in Spain, Kirchner and Patiño (2010) reported that Latina women who had strong feelings of religiosity exhibited less stress and depressive symptoms. These religious-based positive coping can empower Latinxs to engage in health-promoting behaviors.

Religious coping among Latinxs may also be influenced by acculturation. In a study by Moreno and Cardemil (2018b), 88% of the Mexican-born interviewees were engaged in religious activities (usually Christian-based), compared to 37% of USA-born Mexican Americans. Mexican-born participants noted that religiosity was helpful in alleviating/coping with everyday life stress, particularly stress associated with their legal status such as being undocumented (Moreno & Cardemil, 2018b). Religiosity was also seen as an important value to pass down to future generations as these Mexican-born immigrants acculturated to the USA (Moreno & Cardemil, 2018b). Another study by these authors (Moreno & Cardemil, 2018a) reported that Mexican immigrants in the USA had a higher rate of religious attendance and lower prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders when compared to USA-born Mexican Americans.

Religious coping provides broader social supports through the connections built within church communities (Hovey et al., 2014; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013; Noyola et al., 2020). Pastors, priests and church communities may provide comfort, guidance, wisdom, knowledge and support to process feelings and gain specific resources to navigate their concerns (Moreno & Cardemil, 2013; Noyola et al., 2020). Mexicans and Latinxs may rely on their religious and social communities for emotional support in the form of consejos or advice-giving (Caplan, 2019; Salgado-de-Snyder et al., 2003). Religious support may also be more accessible to Latinx communities compared to the barriers described in traditional mental health treatment such as cost and remote locations (Moreno & Cardemil, 2013; Ross et al., 1983). A study by Gallegos and Segrin (2019) found that loneliness was a suppressor variable in the relationship between spirituality and depression—that is, through spirituality Latinos find supportive, satisfying and caring relationships that mitigate feelings of loneliness and improve health. In fact, there may be a particularity in religious-based emotional support. Findings by Krause (2006, 2019) suggest that relationships formed within religious institutions may lead to more effective coping than secular interpersonal relationships.

Religious Coping in Latinx Caregivers

Religiosity may also help caregivers who are supporting patients with an identified mental illness. Research has reported that Latinx caregivers who engage in religious and spiritual practices present fewer depressive symptoms, higher positive affect and life satisfaction, lower levels of morbidity, and increased longevity (Chatters, 2000; Koenig et al., 1999; Koerner et al., 2013; Miller & Thoresen, 1999; Pargament, 1997; Patrick & Kinney, 2003). In a study on caregivers of Mexican descent in the USA, Herrera and colleagues (2009) reported that caregivers who had intrinsic religiosity, that is, strong beliefs and faith, perceived less burden in their caregiver roles. Caregivers who engaged in less structured and non-organized religious practices such as private prayer reported worse mental health and greater caregiver burden (Herrera et al., 2009). Similar to the negative religious coping we see in patients, caregivers who believed in their responsibilities as a punishment or abandonment from God reported higher depressive symptoms (Herrera et al., 2009).

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to analyze a data subset of a larger qualitative study on explanatory models of mental illness among Mexican patients and their family member or caregiver focused on answering the question: “What types of religious and spiritual practices do patients and caregivers engage in to alleviate the patient’s distress?” Although mental health care providers are usually encouraged to incorporate spiritual and religious beliefs and practices for the provision of culturally competent care (Baez & Hernandez, 2001; Bou-Yong Rhi, 2001; Caplan et al., 2011; Mueller et al., 2001), more information is needed on how religious and spiritual practice influence the treatment of mental illness in Mexico. We collected data from Mexicans living and receiving mental health care in Mexico.

Latin America and Mexico are characterized by medical pluralism to address health concerns through traditional or indigenous medicine, Western-based medicine, and home-based remedies (Galaviz & Odgers Ortiz, 2014; Lámbarri Rodríguez et al., 2012; Odgers Ortiz & Olivas-Hernández, 2019). In particular, religious and spiritual practices, also diversifying across Latin America, often fill important treatment gaps where biomedical interventions are less accessible (Galaviz & Odgers Ortiz, 2014; Odgers Ortiz & Olivas-Hernández, 2019). Religious and spiritual therapeutic methods can be considered in conflict with secular biomedical and Western-based approaches to mental health treatment (Galaviz & Odgers Ortiz, 2014; Lámbarri Rodríguez et al., 2012; Odgers Ortiz & Olivas-Hernández, 2019). These approaches find themselves at odds in defining the scope and focus of mental health treatment with biomedical providers also questioning the professionalism and merit of religious and spirituality-based interventions or indigenous healing approaches (Galaviz & Odgers Ortiz, 2014; Lámbarri Rodríguez et al., 2012; Zacharias, 2006). Nevertheless, in a study focused on substance abuse treatment, Galaviz and Odgers Ortiz (2014) noted that both religious and psychiatric (biomedical) providers in Mexico aligned in problematizing the family, mainly the absence of the mother in the home, as a key source in the development of mental health concerns. Understanding the religious and spiritual practices patients and family engage in can inform how multiple treatment approaches help alleviate the experience of mental illness in Mexico.

Method

Design and Participants

The larger qualitative study was conducted at a regional, public, outpatient psychiatric hospital in the city of Puebla in south–central Mexico, 2 h away from Mexico City. Puebla is the fifth largest city in Mexico by population (INEGI, 2021b). According to the 2010 population census, the city of Puebla has a little over 1.5 million inhabitants, representing almost 27% of the total population of the state (INEGI, 2021a). Fifty-five percent of the citizens, more men than women, are economically active (INEGI, 2021b). In the city of Puebla, the majority of the population (50%) has basic education (educación básica), or preschool to 9th grade; 20% have a high school education; and almost 30% have some college or university education (INEGI, 2021b). In contrast, the state of Puebla’s educational average is 8th grade (INEGI, 2021b). Seventy-two percent of the state of Puebla’s population lives in urban settings, and 28% in rural ones, below the national urbanization average of 78% compared to 22%, respectively (INEGI, 2021b). Very few people in the city of Puebla (less than 50 in total) report speaking indigenous languages; those who do, speak náhuatl or totonaco (INEGI, 2021b). However, the overall average of indigenous-speaking population in the state of Puebla is 11 for every 100 people, much higher than Mexico’s national average of 6 for every 100 (INEGI, 2021b).

We adopted a social constructivist approach to understand how patients’, caregivers’, and providers’ experiences of mental illness in Mexico are socially and historically constructed within a hegemonic Western model of mental health treatment (Creswell, 2007). Researchers approaching their interpretations from a social constructivist worldview are attuned to the various and complex meanings underlying participant’s narratives to understand how these subjective meanings are socially and historically negotiated (Creswell, 2007). Social constructivism assumed that personal meanings are formed in interactions with others and are influenced by the social, historical, political, and cultural norms that operate in people’s lives (Creswell, 2007). Therefore, the interpretations we provide are both the personal meanings of participants and the processes of interaction between individuals and their broader worlds.

Patients were recruited using flyers handed out in the main waiting lobby where patients gathered for their outpatient appointments during the summer of 2016 from May to August. Most patients would arrive to the outpatient clinic at the beginning of the morning (9:00 a.m. to 1:30 p.m.) or afternoon (4:00 to 7:30 p.m.) shift on the day their appointment was scheduled and would be seen in the order they arrived. Patients were asked to approach the outpatient receptionist to express interest in participating in the study and were guided to the researchers’ private office to do informed consent procedures.

This study included a total of 19 patients and their accompanying family member (herein, “caregiver”) who were interviewed using the semi-structured DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI; APA, 2013) Patient version (Appendix A) and Informant version (Appendix B). For the secondary analysis presented here, the authors focused on the responses to the CFI questions that elicit information on the cultural factors affecting past and current help seeking (questions 12–15), for example: “Often, people look for help from many different sources, including different kinds of doctors, helpers, or healers. In the past, what kinds of treatment, help, advice, or healing have you sought for your [PROBLEM]?” and “What kinds of help do you think would be most useful to you at this time for your [PROBLEM]?” (APA 2013; p. 754).

The secondary analysis included data from 18 out of 19 cases that identified using spiritual or religious practices to alleviate the patient’s mental illness experiences. All patients were receiving mental health treatment at the outpatient psychiatric clinic where the study was conducted. To participate, patients had to be 18 years or older, and provide consent for their caregiver to be interviewed related to their mental illness experience. Ages ranged from 18 to 83 years (M = 41.9, SD = 19.8), with 10 men and 8 women participants. To comply with HIPAA guidelines related to the privacy of patient’s medical records, patient’s psychiatric diagnoses were not directly requested but rather implied through the gathering of interview data. Patients who participated represented a range of common psychiatric symptoms including psychosis, depression, and anxiety. Caregiver ages ranged from 19 to 73 years (M = 51, SD = 16), with 11 women and 7 men. Caregivers included parents (7), partners or spouses (5), adult children (3), siblings (1), an uncle (1) and a sister-in-law (1). Patients and their family members recruited for this study represented a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds, educational attainment, and provenance as some patients sought psychiatric services from neighboring states (see Table 1).

Procedure

Data for the present study was collected as part of the first-author’s doctoral dissertation research on the cultural conceptions of mental illness among Mexican patients, caregivers, and psychiatrists. This research was approved by the first-author’s university institution and the local outpatient clinic IRB. Data collection was conducted from May to August of 2016. After consent processes, the first author and two research assistants conducted interviews in Spanish of each participant (Patient and Caregiver) separately in private offices at the outpatient clinic. The interview protocol also included demographic questions at the beginning of the interviews for all participants. Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min. All interviews were audio-recorded, de-identified using pseudonyms, uploaded to a secure and password-protected server, and subsequently transcribed in Spanish.

Data Analysis

The data analysis team for the larger study included the first author, three undergraduate psychology students and six master’s-level counseling psychology students who were bilingual, and all but one identified as Latinx, and one who identified as Caribbean but had lived for an extended period in Mexico. All data was coded in Spanish by the bilingual research team. Of note, the first author is originally from the south–central city where the study was conducted where she also received her bachelor’s degree (Licenciatura) in psychology. The research team was paired up to complete data analysis on assigned cases for consensus and fidelity purposes. When discrepancies arose, the first author reviewed the data with both coders to reach consensus. The research team as a whole also conducted consensus coding on one case.

The research team used an emergent coding strategy and followed Braun and Clarke (2006)’s steps to conduct an inductive thematic analysis to identify, analyze, and report latent themes that emerge from the data across interviews and provide a rich description of the essence underlying Mexican patients’ and caregivers’ experience given their particular sociocultural positions. Thematic analysis allows a researcher to identify multiple stakeholders’ descriptions and have a broader understanding of their experiences through patterns of meaning found across the data gathered without theoretical preconceptions (Crowe et al., 2015).

The analysis for this study focused on patients’ and caregivers’ treatment expectations, that is, what they believed would help alleviate the experience of distress or mental illness. Specifically, this information was elicited by the CFI questions related to past and current help seeking (questions 12–15; APA, 2013; p. 754). In the larger qualitative study, four major themes emerged as sources of support or treatment expectations to help alleviate a patient’s distress: psychiatric intervention and medication (18 Patients, 19 Caregivers), religious and spiritual practices (18 Patients, 18 Caregivers), family and social support (15 Patients, 15 Caregivers), and psychological support (13 Patients, 14 Caregivers). Given the richness of the data gathered, we provide the results from a secondary thematic analysis of the subthemes related only to the religious and spiritual practices.

Following the same steps (Braun & Clarke, 2006), we analyzed the latent themes and searched for meanings across the data on religious and spiritual practices to understand how these helped patients and family members alleviate mental illness. The authors of this study extracted all the quotes with the initial code “religious or spiritual practices,” and coded additional subthemes based on the research question: “What types of religious and spiritual practices do patients and caregivers engage in to alleviate the patient’s distress?” As the authors reviewed the initial codes, they found that patients and caregivers discussed religious and spiritual practices as it related to mental health care as either supportive/helpful or unhelpful/harmful. The authors developed subtheme codes for “Positive Coping” and “Negative Coping.” In the third review of the data, the authors noted discussion of indigenous healing which often contained both positive and negative coping, and therefore, decided to code as its own subtheme: “Indigenous-based spiritual healing”. Then, the authors organized the data in a coherent narrative that reflects the main subthemes found and provide exemplary quotes.

Researchers

The authors offer a personal account and interrogation of their experiences, beliefs and practices, and the philosophical underpinnings of the current research endeavor. These accounts offer the reader an understanding of the author’s positionality to assess the credibility and validity of their qualitative assessment (Delgado-Romero et al., 2018). The first author is a queer, cisgender, Latina counseling psychologist. Her interpretations are informed by her identities as a border-crossing Mexican and American (Cervantes-Soon, 2014) who is both an insider and outsider in relationship to the participants of this study. She grew up and was professionally trained as a psychologist in the area where the study was conducted. Through a social constructivist approach, the first author purposefully utilized her cultural and contextual knowledge to “mediate” the different meanings of participants' experiences through her interpretations (Wojnar & Swanson, 2007). Her personal lived experiences mirrored the varied and pluralistic healing methods adopted by the participants she interviewed who often integrated both indigenous healing and religious practices to cope with mental and emotional distress. For example, growing up many of the celebration rituals she engaged in were both Catholic and integrated náhuatl chanting and dance. At the time of colonization, the indigenous people of her hometown were massacred and the Spanish colonizers built churches and alters on top of the main places of worship (teocallis). Although Catholicism was steeped into the cultural practices of her everyday life, the particular practice of Catholicism reflected the negotiation between indigenous and colonizing forces. Similarly, in her research she notes the conflicts that can emerge alongside the coexistence of Western and indigenous psychotherapeutic approaches in practice, with even Christian-based ideologies increasingly diversifying across the Mexican landscape through Evangelical and other emerging faith-based communities.

The second author is a first-generation male Latinx-American-born, cisgender heterosexual graduate student in Latinx counseling psychology. His parents immigrated from Central America, and he was born and raised in the rural Midwest in a predominantly Latinx town. As he is an outsider to the lived experiences of the Mexican participants of this study, he applied his own lived experiences of religion and spirituality as a Latinx American to inform his research with this population. The second author was raised in a Spanish-speaking Catholic and Evangelic environment. His parental figures utilized religion and spirituality as their primary coping mechanisms through practices such as prayer, Bible study and attending church services. As participants also reflected, there were both positive and negative experiences with religious and spiritual coping. Throughout his life, he experienced heated conflicts due to familial differences in faith and practice, which has caused him to doubt most religious or spiritual interventions. In spite of these negative experiences, the second author also finds positives in religious and spiritual healing practices that the participants in this study have reflected such as prayer, studying religious texts, or attending religious gatherings. Due to his American education, the second author views the need for separation between religious and spiritual mental health treatment, and modern psychological and psychiatric forms of care. However, due to being raised in a culture with various faiths and practices but limited in avenues of care, he emphasizes within his research that individuals should have the choice to balance the different methods of treatment they find most culturally and spiritually beneficial to their own well-being (Odgers Ortiz & Olivas-Hernández, 2019).

Results

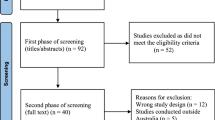

As previously stated, 18 patients and caregivers of the 19 cases in the larger qualitative study, reported on engagement in religious and spiritual practices to help alleviate the patient’s experience of mental illness or mental/emotional distress. Three main subthemes related to religious and spiritual practices emerged: positive religious coping (9 patients and 11 caregivers), indigenous-based spiritual healing (6 patients and 4 caregivers), and negative religious coping (3 patients and 2 caregivers). Patients are identified with numbers (see Table 1). Figure 1 details the thematic map that emerged throughout the coding process.

Positive Religious Coping

Patients reported it was helpful to go to priests or pastors for advice, attend church, pray, talk to God, entrust their suffering to God, and have faith in God. Patients rarely expressed a belief that the etiology of mental illness was religious-based. However, some patients noted concern that others in their social circles would believe that the cause of their distress was due or influenced by their religious practices. For example, patient 13, a 54-year-old man with symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder, expressed fear of telling others about his mental illness experience because "I feel like they would tell me 'stop studying the Bible, that's why you are the way you are'… That's why I don't tell anyone." Yet engaging in religious practices like prayer was a common coping strategy to alleviate the symptoms of mental illness. Patient 13 was a construction worker with little formal education who lived in a rural area 2 h away from the outpatient clinic. He shared:

“Me ha ayudado cuando tenemos reunión se me quita eso. Se me borra de la mente. Pasan dos, tres días, a veces hasta una semana y ando tranquilo, ando normal, pero de que me llega ese pensamiento, no es fácil quitármelo… Leer la Biblia o lo que tenemos que estudiar y todo eso, información espiritual… haga de cuenta que como si se me olvidara o se borrara eso de mi mente. Y ando tranquilo, a gusto.” | “It has helped because when we have a meeting, it all goes away. It erases from my mind. Two, three days, even a week will pass and I’m calm, normal, but when the thought comes, it's not easy to get rid of… To read the Bible, or whatever we have to study, and all that spiritual information, I mean, God’s word, because we have information…it’s as if I forget or it’s erased from my mind. And I’m calm, at ease.” |

Patients reported seeking helpful advice (consejos) from their priest or pastor. For example, patient 8, a 30-year-old man with anxiety symptoms, had served as an altar boy during his childhood and stated that the Catholic priest’s consejos or advice was one of the most helpful sources of support for his distress. Patient 8 had a high school degree and lived 40 min away in an urban area. In another example, 22-year-old patient 3 who had obsessive–compulsive disorder symptoms reported she had sought psychotherapy with a “Christian psychologist." Patient 3 was completing a college degree and also lived in a nearby urban area. Of her Christian-based practices, Patient 3 a noted what was helpful:

“Pues en primer lugar estar en comunión con Dios, ósea, leer diario la Biblia y hacer énfasis lo que dice. Que de nada sirve leer si no lo hago." | "Well in the first place being in communion with God, I mean, reading the Bible every day and emphasizing what it says. Because it doesn't help at all to read if I don't practice it." |

Patients found social connections and communities that supported their recovery through religious activities such as Bible study or attending church services. Patients also invoked their religious-based coping and beliefs to facilitate the healing of the biomedicine-based psychiatric treatment they were prescribed. For example, 18-year-old patient 1 had schizophrenia and was from a rural area 5 h away from the outpatient clinic. Patient 1 stated that his family members recommended he trust in God and discussed the role of God in his medication management:

“Pues unos de los que me ha apoyado es confiar en Dios que me- que funcione los medicamentos. Eso es lo que me ha ayudado hoy” | “Well, one of the supports I’ve had is trusting in God that-that the medication will work. That’s been helpful to this day” |

Patient 11, a 45-year-old man with schizophrenia who lived in the city, worked in photography and had completed middle school, reported wanting religious-based moral advice and reassurance that his mental illness experience did not mean a rupture in his relationship with God. He stated he would find it helpful for someone to tell him: "God is with you, God loves you… God has never left your side." Patient 10, a 43-year-old woman with depression who lived an hour away in a smaller town and owned a taquería, believed that God had "punished her with a cheating husband." Her daughter, caregiver 10, would remind her:

"la hacemos ver que Dios te manda pruebas en esta vida, y tú nos has dicho que Dios nos mandó una prueba muy grande… recuerda cuando yo -en el que me atropellaron y que te dijeron que a lo mejor no despertaba. ¿Y Dios en ese momento a dónde estaba? Te dio otra oportunidad… Le digo, date cuenta que a lo mejor te está mandando una prueba." | "we make her see that God sends you challenges in this life, and you have told us that God has sent us a big challenge… remember when I was run over by a car and they said I might not wake up. And where was God then? He gave you an opportunity… I tell her, notice that maybe he is sending you a challenge." |

For many of these patients, the reassurance that God was “on their side” and the active advice from people in church communities was helpful. Patients’ religious engagement in these instances provided connection and solace during times of need, emphasizing the potential for healing and overcoming their mental health concerns.

Indigenous-Based Spiritual Healing

Patient 6, a 27-year-old man with schizophrenia, incorporated both his pastor's support in prayer with indigenous-based support of a curandero (i.e., indigenous medicine doctor). Patient 6 was a college student who lived in a rural town 2 h away from where the study was conducted. He noted that the curandero provided body massages and limpias (herb-based cleanses) to help him decrease stress and relieve muscular tension that he believed promoted his mental health and well-being. Patient 6 made a distinction between curanderos and brujos (i.e., “witch doctors”), stating that “I don't go with the brujos because I believe that is bad." In another case, patient 8’s father, caregiver 8, noted he had taken his son for a limpia before but had stopped this practice because a Catholic priest had told the family that Catholics should not engage in limpias or go to brujos or curanderos for healing. Patient 8 and his father both lived in the city and patient 8 was a gym instructor who completed a high school degree.

Some patients described trepidation seeking indigenous healing as they had felt deceived by curanderos in the past. Patient 16, a 70-year-old woman with depression had been engaged in mental health treatment for over 30 years with different types of healers. She lived in a smaller town an hour away, reported she was a homemaker and had completed up to 2nd grade of formal education. She described: "[My husband] took me to some curanderas that also heal to do a purge and I felt really bad… it was a horrible thing, and I didn't find any comfort anyway and I would sleep on rose petals and all that." When asked whether going to the curanderas was helpful, patient 16 replied: "Not at all! They only took our money, took all our money and asked to bring them turkey eggs, three kilos of coal, bring roses to sleep with, shower with water of who knows what, using a bunch of herbs until we got tired of it." Patient 16’s husband, caregiver 16, noted that despite going to curanderos and biomedical doctors, healers had not correctly diagnosed her depression as caused by the sudden loss of their 12-year-old daughter. After all the explanations provided by different healers, caregiver 16 stated: “to tell you the truth, I only believe in God.” In another case, caregiver 17, the wife of patient 17, a 71-year-old man who had a substance use disorder, stated that the curandero had asked the family for $6000 MXN before and after the treatment, a total of $12,000 MXN to provide limpias while patient 17 continued his psychiatric medication. Patient 17 also had little formal education (up to 4th grade) and lived in a smaller town 2 h away. His wife stated: "there are many people who advertise on the radio that they cure and what not, but no, they only take away people's money and it's not true."

Patients 4 (a 22-year-old man with drug-induced psychosis) and patient 12 (a 47-year-old man with bipolar disorder) also reported that going to an indigenous-based healer did not help alleviate their distress. Patient 4 was still completing a high school degree and lived in a small town 1.5 h away. Patient 12 had a college degree and lived in a city an hour away from where the study was conducted. They both made the distinction of going to a brujo (“witch doctor”) rather than a curandero (indigenous medicine doctor). Of the experiences with the brujo, patient 12 noted:

“me hicieron este, limpias de bolsillo, porque cobraron carisimo, pero bueno, consideraban que mi problema era porque alguien me estaba causando un daño. Entonces, así fue como las vendieron y así fue como la compramos.” | "they did cleanses but of my pocket because they charged so much, but well, they thought my problem was because someone had done some damage [tried to hurt] to me. So that's how they sold it and that's how we bought it." |

Patient 12 had also sought treatment with a Catholic priest because his wife at the time was very religious. He noted that he went to mass weekly and then was taken to six to eight sessions of exorcism. Of this experience, Patient 12 stated:

“Los médicos [psiquiatras] consideran que quizá no fue muy sano el haber hecho eso ¿Si? Ahora sí, mi sacerdote opinaba que pues era bueno. Y yo la verdad me quedé en eso de que no supe que si fue útil o no fue útil.” | "The [psychiatric] doctors believe that maybe it wasn't a very healthy thing to have done, yes? Now then, my priest thought it was a good thing. And me, to be honest, I was left not knowing whether it was helpful or not helpful." |

Although indigenous healers and other spiritual or religious-based healing was ostensibly more accessible to patients in their communities, there was no assurance these experiences would be helpful or healing.

Negative Religious Coping

For some patients, religious practice was not helpful or could potentially be harmful. Patient 2, a 19-year-old woman with depressive symptoms who was attracted to the same sex, was encouraged by others, particularly her mother, to seek advice or counseling from Catholic priests. She was completing a high school degree in the city only 20 min away. Patient 2 frequently argued with her mother who was not accepting of her sexual orientation, and believed this conflict incited her depressive symptoms. Patient 2 noted that she was not religious and therefore, religious-based coping was unhelpful for her current experience of distress and likely had the potential to perpetuate harmful messages about her sexuality.

In the case of patient 14, a 54-year-old woman with depression, she expressed feeling overtly shamed and rejected by a priest. Patient 14 was a homemaker with up to 5th grade of formal education who lived in a small town an hour away. She noted she "did not believe in curanderos" but "believed in priests" but "they sometimes have a way of saying things that just doesn't go well." Patient 14 had experienced multiple depressive episodes, one in particular after terminating a pregnancy. She recalled:

"no me había yo casado por la iglesia porque yo me casé por el civil luego, luego con mi marido y nos juntamos y ya todo entonces este no me casé. Me casé hasta los 6, 7 años de eso, entonces sentí la necesidad de ir a confesarme porque no estaba yo bien con lo del aborto, no estaba yo bien, entonces fui allá a [nombre de iglesia] y le dije al sacerdote, me empecé a confesar y me dice: "¿Eres casada?" Y le digo: "Si." ¿Por la iglesia?" "No–no-no Padre" Y ¡¿para qué?! Me dice: "Aléjate Satanás aquí no eres bien recibido." Pues sí, imagínese si le hubiera yo dicho lo del aborto, digo no, me hizo sentir muy mal y por eso no.” | "I hadn't gotten married in the church yet because I got a civil marriage right away with my husband, we got together and all that so I didn't get married. I got married until 6, 7 years after that, so I felt the need to go to confession because I didn't feel good about the abortion, I wasn't well, so we went there to the [name of the church] and I told the priest, I started confessing and he said: "Are you married?" And I told him: "Yes." "In the church?" "No–no-no Father." And for what?! He told me: "Get away Satan, you are not welcome here." Well yes, imagine if I would have told him about the abortion, I mean no, he made me feel so bad and that's why no." |

Harm seemed to occur when values and expectations clashed between patients and the religious systems and practices they sought for help. Rejection from religious leaders or their communities due to patient’s experiences or identities further entrenched their social disconnection and lack of social support for their mental health concerns. These interactions may also reflect broader colonial dynamics of sexism, classism, homophobia, and racism that are embedded in some religious philosophies practiced in Mexico.

Discussion

The primary objective of this secondary analysis was to explore and understand religious and spiritual practices that help alleviate distress as reported by Mexican patients and their caregivers. Similar to previous findings, patients in our study found positive religious coping such as entrusting God with one’s suffering and a spiritual connection to God was helpful in alleviating their distress (Hovey et al., 2014; Koerner et al., 2013; Pargament et al., 1998). They actively engaged in religious practices like prayer, reading the Bible, and attending church services or gatherings to prevent worsening symptoms (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004; Caplan, 2019; Krause & Bastida, 2012; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013). Consejos emotional support and advice-giving from clergy/chaplains was also a common positive practice, and like similar findings suggest, patients found the social connections and communities they built in the church to be helpful (Gallegos & Segrin, 2019; Hovey et al., 2014; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013; Noyola et al., 2020). Religious communities provide social support and aid for Latinxs to cope with everyday life stressors such as migration, financial strain, food, and housing insecurity (Gallegos & Segrin, 2019; Krause, 2019; Moreno & Cardemil, 2013, 2018b; Noyola et al., 2020).

Despite the mostly positive gains from religious and spiritual practices, some patients, particularly women, found themselves stigmatized by clergy/chaplains or religious philosophies. Of note, a woman experiencing same-sex attraction found her mother’s push toward religious coping harmful because of Catholic stances overtly against same-sex attraction. Another woman who had sought consejos or advice from a priest through confession was harmed by her priest’s shaming. Previous research has noted that negative religious coping, including contentious relationships with clergy/chaplains or feelings that God is punishing or abandoning, can be harmful (Hovey et al., 2014; Mueller et al., 2001; Pargament et al., 1998). And in the case of Latina women, negative religious coping may even increase symptoms of mental illness (Cuevas et al., 2015). Clergy can be an important influence on health-seeking and health-promoting behavior (Rivera-Hernandez, 2016). Therefore, it is essential to understand how to effectively collaborate with clergy and mitigate any potential negative impacts on mental health care.

In our study, engagement in indigenous healing practices was less common, despite previously reported prominence of indigenous folk healing in Latin America (Baez & Hernandez, 2001). However, patients reported incorporating both Christian-based religious practices with indigenous healing such as body massages and limpias (herb-based cleanses) to decrease stress that reflect the colonial relationship and integration of indigenous healing and religious practice (Lujan & Campbell, 2006). Although patients had sought indigenous healers in the past, there was a clear tension between those who were seen as sanctioned healers (i.e., curanderos), and those who were practicing dark magic (i.e., brujos) who were often deemed charlatans trying to deceive and financially exploit their patients. Some patients were unsure whether the indigenous healing or religious practices helped. In patient 12’s example, he had sought explanations of his illness experience from a brujo who said someone was wishing him harm but that healing ritual did not help. He then went to a Catholic priest who conducted sessions of exorcism and was again unsure whether that helped. Even though our patients reported ambivalent to negative experiences with indigenous healers, they likely utilized them because it reflects culturally relevant beliefs and practices. The way that patients make sense of their mental illness influence the treatment they seek. If patients believe in curanderismo, they will likely seek that source of treatment (Lámbarri Rodríguez et al., 2012). However, treatment effectiveness will also depend on whether patients seek sanctioned or fraudulent treatment.

Limitations

There were several noteworthy limitations to this study. First, participants were all from a similar south/central region of Mexico which would limit capturing the cultural richness in religious and spiritual engagement across the country as a whole. This also limits generalizability to Latinxs as a highly heterogenous group with each cultural subgroup influenced by their own histories, values, beliefs and practices. Nevertheless, participants in our study reported on a variety of engagement that included Christian and Catholic religious coping in addition to indigenous healing such as curanderismo. Second, all the patients in this study were currently engaged in psychiatric treatment. Thus, although religious and spiritual coping may have been helpful, by study design all of our patients had sought medical approaches to psychological care. Finally, as a qualitative study we relied on participants’ self-report on helpful coping. Qualitative data can provide detailed and rich accounts, and further research could also include systematic quantitative measures that capture the effectiveness of different coping strategies for the alleviation of mental and emotional distress across patients who often use both psychiatric and religious and spiritual healing.

Implications & Future Directions

Religion and spirituality are foundational to Latinxs’ sense of self, purpose, mental and physical health (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004; Lujan & Campbell, 2006; Padilla & Salgado de Snyder, 1988). A key implication of this study is for mental health providers to understand and discuss the role of religious and spiritual practices at the onset of mental health treatment to improve overall psychological well-being (Baez & Hernandez, 2001; Bou-Yong Rhi, 2001). Because of the secular nature of psychiatric and psychological care, mental health providers are less likely to have explicit and candid conversations with patients and their families about the merits of religious and spiritual coping and may even disparage these in their professional roles (Odgers Ortiz & Olivas-Hernández, 2019). Latinx patients may also find difficulties seeking professional mental health providers due to lack of access to culturally relevant care in their communities (Levkoff et al., 1999). Additionally, integrating spiritual explanations rooted in indigenous belief systems of health and well-being may be culturally congruent with a Mexican and general Latinx population (Caplan, 2019; Comas-Diaz, 2006; Duncan, 2017).

The Clergy Outreach and Professional Engagement (C.O.P.E.) model is a helpful example of “religion-inclusive” collaboration between psychologists and clergy to facilitate community-based mental health care (Milstein et al., 2008). This model asks mental health care providers to approach the role of religion in patient’s care by (a) assessing the role of religion; (b) educating oneself about the patient’s religious tradition; and (c) discussing potential contact with patient’s clergy/religious leader(s) (Milstein et al., 2008). Patient’s mental and emotional concerns can be better addressed through collaboration by harnessing clergy’s expertise in religious knowledge and clinician’s expertise in mental health that will lessen the burden of any one stakeholder in promoting wellness (Milstein et al., 2008). Collaboration can increase access to mental health in rural areas (Hall & Gjesfjeld, 2013), help alleviate feelings of inadequacy and lack of skills in clergy/chaplains responding to mental health concerns (Hall & Gjesfjeld, 2013; McHale, 2004), and train clinicians to effectively collaborate with faith-based systems (McMinn et al., 2001, 2003; Plante, 1999).

Similar models to C.O.P.E. (Milstein et al., 2008) could be developed for working with Mexicans and Latinxs to encourage collaboration with religious and spiritual leaders that will promote the wellness of patients and their families (Odgers Ortiz & Olivas-Hernández, 2019). Research by Rivera-Hernandez (2016) with clergy in Mexico highlights the importance of open communication to foster social and community interaction and that clergy view the modern church as having a role in promoting health among their congregants. A study by Schwingel and Gálvez (2016) demonstrates the benefits of faith-based health promotion programs to engage Latinxs in the spaces and communities where they have already built nurturing and trusting relationships. These models have important implications in global settings with a dearth of psychology-based services and an abundance of religious and spiritual communities (McMinn et al., 2001).

The negative aspects of religious and spiritual coping among Latinx communities should be further investigated to fully understand what components of these institutions and practices are non-beneficial or potentially harmful. Certainly, previous research has found indigenous healing such as curanderismo to be culturally affirming, helpful, and a common avenue for mental health care (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2006). It would be important to further understand the structural and practical concerns of patients being defrauded and deceived by unsanctioned healers, or being harmed by underlying religious philosophies and practices. Thus, future research could focus on understanding the role of clergy/chaplains, curanderos, and community-based religious and spiritual treatment that either mitigate or exacerbate mental health-related concerns. Future research is also needed to understand the gendered dynamics that influence help seeking and mental health care when men are commonly overrepresented in religious leadership (often male priests or pastors) and male biomedical providers such as psychiatrists comprise approximately 65% of all the psychiatrists in Mexico (Heinze et al., 2016).

The level of comfort and trust of patients to discuss their view on the causes of their mental illness and how they should treat it is imperative, and reflected in the experiences of our study participants. As recommended by Comas-Diaz (2006) and in the APA Multicultural Guidelines (American Psychological Association, 2017), multiculturally oriented mental health care providers incorporate their patients’ religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs into treatment (Bou-Yong Rhi, 2001; Mueller, Plevak, Rummans, 2001). Plante (2014) suggested four steps for psychologists to improve their religious and spiritual cultural competence: (1) be aware of biases and prejudice related to different religious practices; (2) consider religion as any other type of diversity; (3) take advantage of the resources available to learn and understand spiritual and religious practices; and (4) integrate consultation with clergy and other spiritual leaders similar to how psychologists might consult with other professionals (e.g., physicians, social workers) involved in the mental health care of a patient.

Notes

For a general review on the effects of religion on health and an integrating conceptual framework, see Krause (2011).

References

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Vásquez, E., & Echeverría, S. E. (2004). En las manos de Dios [in God’s hands]: Religious and other forms of coping among Latinos with arthritis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.91

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality [Data set]. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/e501962018-001

Applewhite, S. L. (1996). Curanderismo: Demystifying the health beliefs and practices of elderly Mexican American. Health & Social Work, 20(4), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/20.4.247

Baez, A., & Hernandez, D. (2001). Complementary spiritual beliefs in the Latino community: The interface with psychotherapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(4), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.71.4.408

Berenzon-Gorn, S., Ito-Sugiyama, E., & Vargas-Guadarrama, L. A. (2006). Enfermedades y padeceres por los que se recurre a terapeutas tradicionales de la Ciudad de México. Salud Publica de México, 48(1), 45–56. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0036-36342006000100008&lng=es&tlng=es.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caplan, S. (2019). Intersection of cultural and religious beliefs about mental health: Latinos in the faith-based setting. Hispanic Health Care International, 17(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540415319828265

Caplan, S., Paris, M., Whittemore, R., Desai, M., Dixon, J., Alvidrez, J., Escobar, J., & Scahill, L. (2011). Correlates of religious, supernatural and psychosocial causal beliefs about depression among Latino immigrants in primary care. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(6), 589–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.497810

Cervantes, J. M., & Parham, T. A. (2005). Toward a meaningful spirituality for people of color: Lessons for the counseling practitioner. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.69

Cervantes-Soon, C. (2014). The US-Mexico border-crossing Chicana researcher: Theory in the flesh and the politics of identity in critical ethnography. Journal of Latino/Latin American Studies, 6(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.18085/llas.6.2.qm08vk3735624n35

Chatters, L. M. (2000). Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 21(1), 335–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335

Comas-Diaz, L. (2006). Latino healing: The integration of ethnic psychology into psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(4), 436–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.436

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Crowe, M., Inder, M., & Porter, R. (2015). Conducting qualitative research in mental health: Thematic and content analyses. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415582053

Cuevas, C. A., Sabina, C., & Picard, E. H. (2015). Posttraumatic stress among victimized latino women: Evaluating the role of cultural factors: posttraumatic stress among latino women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 531–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22060

Da Silva, N. D., Dillon, F. R., Verdejo, T. R., Sanchez, M., & De La Rosa, M. (2017). Acculturative stress, psychological distress, and religious coping among Latina young adult immigrants. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(2), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017692111

Delgado-Romero, E. A., Singh, A. A., & De Los Santos, J. (2018). Cuéntame: The promise of qualitative research with Latinx populations. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 6(4), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000123

Duncan, W. (2017). Psicoeducación in the land of magical thoughts: Culture and mental-health practice in a changing Oaxaca. American Ethnologist, 44(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12424

Galaviz, G., & Odgers Ortiz, O. (2014). Estado laico y alternativas terapéuticas religiosas. El caso de México en el tratamiento de adicciones. Debates Do NER, 15(26), 253–276. https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/debatesdoner/article/view/52063/32089

Gallegos, M. L., & Segrin, C. (2019). Exploring the mediating role of loneliness in the relationship between spirituality and health: Implications for the Latino health paradox. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(3), 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000180

Garcia, G., Ellison, C. G., Sunil, T. S., & Hill, T. D. (2013). Religion and selected health behaviors among latinos in Texas. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9640-7

George, L. K., Ellison, C. G., & Larson, D. B. (2002). Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1303_04

Hall, S. A., & Gjesfjeld, C. D. (2013). Clergy: A partner in rural mental health? Journal of Rural Mental Health, 37(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000006

Heinze, G., Chapa, G. del C., & Carmona-Huerta, J. (2016). Los especialistas en psiquiatría en México: Año 2016. Salud Mental, 39(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2016.003

Herrera, A. P., Lee, J. W., Nanyonjo, R. D., Laufman, L. E., & Torres-Vigil, I. (2009). Religious coping and caregiver well-being in Mexican-American families. Aging & Mental Health, 13(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802154507

Hill, P. C., & Pargament, K. I. (2003). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. American Psychologist, 58(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64

Hovey, J. D., Hurtado, G., Morales, L. R. A., & Seligman, L. D. (2014). Religion-based emotional social support mediates the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and mental health. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(4), 376–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.833149

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) (2021a). Censo de Población y Vivienda. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) (2021b). México en cifras: Puebla (21). https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=21

Joshi, S., & Kumari, S. (2011). Religious beliefs and mental health: An empirical review. Delhi Psychiatry Journal, 14(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730

Keller, H. (2002). Culture and development: Developmental pathways to individualism and interrelatedness. In W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, & D. N. Sattler (Eds.), Online Readings in Psychology and Culture (Unit 11, Chap. 1), Bellingham, WA: Center for Cross-Cultural Research, Western Washington University.

Kirchner, T., & Patiño, C. (2010). Stress and depression in Latin American immigrants: The mediating role of religiosity. European Psychiatry, 25(8), 479–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.003

Koenig, H. G., Idler, E., Kasl, S., Hays, J. C., George, L. K., Musick, M., Larson, D. B., Collins, T. R., & Benson, H. (1999). Religion, spirituality, and medicine: A rebuttal to skeptics. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 29(2), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.2190/c2fb-95vw-fkyd-c8rv

Koerner, S. S., Shirai, Y., & Pedroza, R. (2013). Role of religious/spiritual beliefs and practices among Latino family caregivers of Mexican descent. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032438

Krause, N. (2006). Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based social support and secular social support on health in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 61B, S35–S43. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.S35

Krause, N. (2011). Religion and health: Making sense of a Disheveled literature. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9373-4

Krause, N. (2019). Religion and health among Hispanics: Exploring variations by age. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(5), 1817–1832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00866-y

Krause, N., & Bastida, E. (2012). Religion and health among older Mexican Americans: Exploring the influence of making Mandas. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 812–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9389-9

Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2014). Trust-based prayer expectancies and health among older Mexican Americans. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(2), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9786-y

Lámbarri Rodríguez, A., Flores Palacios, F., & Berenzon Gorn, S. (2012). Curanderos, malestar y “daños”: Una interpretación social. Salud mental, 35(2), 123–128. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-33252012000200005&lng=es&tlng=es.

Levkoff, S., Levy, B., & Weitzman, P. F. (1999). The role of religion and ethnicity in the help seeking of family caregivers of elders with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 14(4), 335–356. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006655217810

Lujan, J., & Campbell, H. B. (2006). The role of religion on the health practices of Mexican Americans. Journal of Religion and Health, 45(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9019-8

McHale, M. (2004). Catholic priests as counselors: An examination of challenges faced and successful techniques. Verbum, 1(2), 15. https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/verbum/vol1/iss2/3

McMinn, M. R., Meek, K. R., Canning, S. S., & Pozzi, C. F. (2001). Training psychologists to work with religious organizations: The Center for Church-Psychology Collaboration. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(3), 324–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.32.3.324

McMinn, M. R., Aikins, D. C., & Lish, R. A. (2003). Basic and advanced competence in collaborating with clergy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(2), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.34.2.197

Miller, W. R., & Thoresen, C. E. (1999). Spirituality and health. In W. R. Miller (Ed.), Integrating spirituality into treatment: Resources for practitioners (p. 3–18). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10327-001

Milstein, G., Manierre, A., Susman, V. L., & Bruce, M. L. (2008). Implementation of a program to improve the continuity of mental health care through Clergy Outreach and Professional Engagement (C.O.P.E.). Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(2), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.218

Moreno, O., & Cardemil, E. (2013). Religiosity and mental health services: An exploratory study of help seeking among Latinos. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031376

Moreno, O., & Cardemil, E. (2018a). The role of religious attendance on mental health among Mexican populations: A contribution toward the discussion of the immigrant health paradox. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000214

Moreno, O., & Cardemil, E. (2018b). Religiosity and well-being among Mexican-born and U.S.-born Mexicans: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 6(3), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000099

Mueller, P. S., Plevak, D. J., & Rummans, T. A. (2001). Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: Implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 76(12), 1225–1235. https://doi.org/10.4065/76.12.1225

Muñoz, R. F., & Mendelson, T. (2005). Toward evidence-based interventions for diverse populations: The San Francisco General Hospital prevention and treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 790–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.5.790

Noyola, N., Moreno, O., & Cardemil, E. V. (2020). Religious coping and nativity status among Mexican-origin Latinxs: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 8(3), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000147

Odgers Ortiz, O., & Olivas-Hernández, O. L. (2019). Productive misunderstandings: The ambivalent relationship between religious-based treatments and the lay state in Mexico. International Journal of Latin American Religions, 3(2), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-019-00091-1

Padilla, A. M., & De Snyder, V. N. (1988). Psychology in pre-Columbian Mexico. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 10(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863880101004

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. Guilford Publications.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 710. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388152

Patrick, J. H., & Kinney, J. M. (2003). Why believe? The effects of religious beliefs on emotional well being. Journal of Religious Gerontology, 14(2–3), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1300/j078v14n02_05

Plante, T. G. (1999). A collaborative relationship between professional psychology and the Roman Catholic Church: A case example and suggested principles for success. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30(6), 541–546. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.30.6.541

Plante, T. (2014). Four steps to improve religious/spiritual cultural competence in professional psychology. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 1(4), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000047

Rhi, B. (2001). Culture, spirituality, and mental health. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(3), 569–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70248-3

Rivera-Hernandez, M. (2016). Religiosity, social support and care associated with health in older Mexicans with Diabetes. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(4), 1394–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0105-7

Ross, C. E., Mirowsky, J., & Cockerham, W. C. (1983). Social class, Mexican culture, and fatalism: Their effects on psychological distress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11(4), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00894055

Salgado-de-Snyder, V. N., Díaz-Pérez, M. J., González-Vázquez, T. (2003). Modelo de integración de recursos para la atención de salud mental en la población rural de México. Salud Pública de México, 45(1), 19–26. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0036-36342003000100003&lng=es&tlng=es

Schwingel, A., & Gálvez, P. (2016). Divine interventions: Faith-based approaches to health promotion programs for Latinos. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(6), 1891–1906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0156-9

Tree, I. (2001). Sliced iguana: Travels in Mexico. Penguin Books.

Wojnar, D. M., & Swanson, K. M. (2007). Phenomenology: An exploration. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 25(3), 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010106295172

Zacharias, S. (2006). Mexican Curanderismo as Ethnopsychotherapy: A qualitative study on treatment practices, effectiveness, and mechanisms of change. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53(4), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120601008522

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the collaboration of Dr. Kristin Yarris, Dr. Stephen López, Isabel Iturrios, and Diego Guevara as part of the Latino Mental Health Research Training Program (MHIRT) Team. Thanks to the Mexico Research Team who helped transcribe interviews and with data analysis (Verónica Franco, Gabriella Gaus, Karen Godinez, Cung King, Mónica Madrigal, Natalie Mena, Anais Picarelli, and Suzie Sainvilmar). Additional thanks to Dr. Stephen Quintana who provided feedback throughout this study.

Funding

This research received financial support through the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute for Regional and International Studies (IRIS) Graduate Student Summer Fieldwork Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stege, A.M.R., Godinez, J. Trusting in God: Religious and Spiritual Support in Mental Health Treatment Expectations in Mexico. J Relig Health 61, 3655–3676 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01554-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01554-0