Abstract

Surgery is a relatively commonplace medical procedure in healthcare settings. The mental health status of the person undergoing surgery is vital, but there is dearth of empirical studies on the mental health status of surgery patients, particularly with regard to the factors associated with anxiety in surgical conditions. This study investigated the roles of religious commitment, emotion regulation (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) and social support in preoperative anxiety in a sample of 210 surgical inpatients from a Nigerian tertiary healthcare institution. A cross-sectional design was adopted. Before the surgery, respondents completed the state anxiety subscale of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Religious Commitment Inventory, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. After controlling for relevant demographic factors, regression results showed that cognitive reappraisal, social support and interpersonal religious commitment were negatively associated with preoperative anxiety, while expressive suppression was positively associated with preoperative anxiety. The emotion regulation strategies made robust and significant explanation of variance in preoperative anxiety. Appropriate interventions to promote interpersonal religious commitment, encourage cognitive reappraisal and enhance social support quality may improve mental health outcomes in surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

About one-third of the global disease burden requires surgical and/or anaesthetic care (Meara et al. 2015). When one considers the list of health conditions that require surgery, it appears that surgery is a common procedure in healthcare settings. In the absence of surgical care, case-fatality rates are high for common, easily treatable conditions including appendicitis, hernia, fractures, obstructed labour, congenital anomalies, and breast and cervical cancer (Meara et al. 2015). Although hospitalization, regardless of disease, is known to provoke anxiety, the situation can be more debilitating for the patient admitted for surgery. Anxiety can occur before or after the surgery. When it occurs before surgery, it is known as preoperative anxiety but when it occurs after the surgery, it is labelled postoperative anxiety.

Preoperative anxiety can be challenging for healthcare providers in the care of patients. Most surgeons postpone operation in cases with high anxiety (Nigussie et al. 2014; Phipps et al. 2004). If unrecognized, prolonged anxiety creates stress which may subsequently harm the patient and delay recovery (Mitchell 2004; Swindale 2004; Yilmaz et al. 2011), which underscores the relevance of research and intervention in this regard (Caumo et al. 2001). The incidence of preoperative anxiety ranges from 60 to 92% in surgical patients and also varies among different surgical groups (Frazier et al. 2003; Ping et al. 2012). The degree to which each patient manifests anxiety related to future experiences depends on many factors (see Nigussie et al. 2014). Hence, the identification and understanding of anxiety as experienced by surgical patients as well as the psychological variables that correlate with anxiety is vital, given that assisting patients in coping with anxiety is recognized as one of the health workers’ most important responsibilities (McMurray et al. 2007).

There is a wealth of research conducted on anxiety in surgical patients in developed Western cultures, but little is known about pre- and postoperative anxiety in the developing parts of the world. Relatively recent studies have suggested the need for more studies on the psychosocial factors and effective interventions to reduce preoperative anxiety in non-Western countries (e.g., Guo 2015). We believe that evidence from developing cultures will increase the knowledge base about the predictors of preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients. Specifically, an investigation of the roles of religious commitment, emotion regulation and social support in preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients may be seen as important not only to enhance knowledge and understanding of the patients’ experience, but also for the successful implementation of policies and strategies in anxiety management, care services or interventions.

Religious commitment is a term used to reflect the degree or level of religiosity. It attempts to capture how committed the person is to his/her religion by way of indicating the amount of time spent in private religious involvement, religious affiliation, the activities of religious organization and importance of religious beliefs (Worthington et al. 2003). Worthington et al. found that religious commitment has both interpersonal and intrapersonal dimensions. Intrapersonal religious commitment represents the individual’s search for religious knowledge, depth of personal framework and quest for meaning in life by means of religion. Interpersonal religious commitment is the felt, participatory and consequential aspect of religion as manifested in social relations and activities. As a construct which is known to predict a range of health outcomes (e.g., Mouch and Sonnega 2012), religious coping and attendance at religious services have been advanced to be representative of religious commitment (Clements et al. 2015).

In a review of previous research, Larson et al. (1992) reported that out of the 50 studies on the relationships between religious commitment and psychopathology, 36 (72%) reported a positive relationship, eight (16%) reported a negative relationship, and six (12%) reported a neutral relationship. Earlier review focusing on anxiety also showed similar patterns: four studies showed that religious subjects were more anxious, three studies found religious subjects to be less anxious, and three studies reported a null relationship between religiosity and anxiety (Gartner et al. 1991). Even in some other recent studies, religiosity variables were found to be strongly negatively correlated with anxiety (Clements et al. 2015; Nadeem et al. 2017), while others showed that religiosity did not correlate significantly anxiety (e.g., Shiah et al. 2015). The inconsistency of findings may be attributed to two factors: (1) distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic religious commitment (Gartner et al. 1991) and (2) the general nature of anxiety examined in most of the studies. The different forms of religious commitment may be differentially related to different anxiety states. Evidence in this regard had shown that intrinsic (intrapersonal) religiosity correlated with lower anxiety while extrinsic (interpersonal) religiosity was associated with higher anxiety levels (Bergin et al. 1987). There could be a clear direction and pattern of findings if a dimensional religious commitment is considered and anxiety is specified to particular domains or situations of life. Studies on the relationship between religious commitment and anxiety among patients undergoing surgery are scarce. Research on this population is considered to be of immense value in order to understand how optimal health may be improved or maintained in surgery.

A patient’s control or regulation of the emotional state is also critical to the patient’s preparedness and anxiety at the preoperative stage. Emotion regulation is an individual differences variable referring to the processes by which people influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions (Gross 1998). Increasing recognition of the crucial role of emotion regulation in mental health outcomes has helped to identify specific emotion regulation strategies as either maladaptive or adaptive. The two major forms of emotion regulation based on Gross (1998) conceptualization are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Emotion regulation via expressive suppression has been associated with various mental health disorders including anxiety (Aldao et al. 2010), while emotion regulation via reappraisal is thought to be among the most adaptive and effective forms of emotion regulation (Gross 1998) and it had led to increased pain tolerance and less incidence of anxiety during surgery (Campbell-Sills et al. 2006; Gross and John 2003; Hayes et al. 2010). Since most of the available literature on emotion regulation and anxiety are studies in western high income societies, it is necessary to extend such investigations to the low and middle income societies in order to enhance mental healthcare services and programmes.

Despite the assurances of medical personnel, patients my still feel vulnerable when anticipating surgery. The social support available and recognized by them may be critical to their preoperative state. Social support refers to the perception and actuality that one is cared for has assistance available from other people, and that one is part of a supportive social network (Taylor 2011). These supportive resources can be in form of emotional (e.g., nurturance, empathy, concern, affection, love, trust, acceptance, intimacy, encouragement or caring), tangible (e.g., financial assistance, material goods or services), informational (e.g., advice, guidance, suggestions) or companionship (e.g., sense of belonging) and intangible (e.g., personal advice) support. Support can also come from many sources, such as family, friends, neighbours, co-workers, organizations, or governmental support often referred to as public aid. Limited social connectedness impacts negatively on the quality and rate of recovery after major operations (Mitchinson et al. 2007). Generally, social support leads to better mental health outcomes in stressful times (de Souza et al. 2017; Heilmann et al. 2016; Isaacs and Hall 2011).

A theory which can be applied to link the predictor variables in this study to the development of preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients is the Anxiety Sensitivity Theory (AST; Reiss 1991; McNally 1994). Anxiety sensitivity (AS) is the fear of arousal-related sensations, due to beliefs that the sensations have deleterious physical, psychological or social consequences that extend beyond any immediate physical discomfort during an episode of anxiety itself such as death, insanity or social rejection (Reis and McNally 1985). The theory upholds that anxiety sensitivity is displayed differently by each individual, and it may sometimes be characterized by the fear of anxiety-related feelings. In line with the postulations of the Anxiety Sensitivity Theory, we assume that when individuals have anxiety-related feelings but they are equipped with cognitive strengths and have adaptive emotional capabilities which may be reinforced by functional social support networks, and healthy religious faith and practice, these resources can counteract the occurrence of anxiety. We hypothesized as follows: (1a) cognitive reappraisal will be negatively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients; (1b) expressive suppression will be positively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients; (2) social support will be negatively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients; (3a) interpersonal religious commitment will be negatively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients; and (3b) intrapersonal religious commitment will be negatively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study comprised 210 inpatients that were scheduled for elective surgery in the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, in Enugu State, Nigeria. Inclusion criteria in this study were adult surgical patients who were sufficiently alert mentally to be able to respond to the questionnaires; undergoing surgery for the first time; having no endocrine and metabolic disorders; being in a stable physical condition as determined by their medical records; having no known psychiatric illness and/or currently on any type of anti-anxiety or anti-depressant medications such as benzodiazepines, tricyclic-antidepressants, selective serotonin inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors or lithium; having a minimum of secondary education to be literate to respond to the questionnaires; and having no fever during time of data collection. Surgical inpatients within the 15 weeks the study lasted in the hospital who met the above criteria and were willing to participate were involved in the study.

Measures

The participants completed a questionnaire comprising four measures: state anxiety subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Religious Commitment Inventory, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Information on basic demographic characteristics was also included in the questionnaire. Patients’ individual files were also reviewed to obtain records of relevant baseline characteristics (e.g., type of surgery).

Anxiety was measured with the state anxiety (S-anxiety) subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y1; Spielberger et al. 1983). It consists of 20 items, scored on a four-point scale: not at all, somewhat, moderately so, and very much so; with a total score range of 20 to 80 points. A higher score indicates more S-anxiety. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) coefficients of the scale ranged from .86 to .95, with a median coefficient of .93 (Spielberger et al. 1983). Validity of the S-anxiety scale was shown by means of its correlations with measures of personality, adjustment, stress, academic aptitude and achievement (Spielberger et al. 1983). Karanci (2003) reported an α estimate for the preoperational administration of the scale as .91. Preliminary analyses for the reliability of S-anxiety subscale in the present study yielded a Cronbach’s α of .92.

The Religious Commitment Inventory (RCI-10; Worthington et al. 2003) was used to measure the patients’ religious commitment. The scale assesses an individual’s level of religious adherence in daily life and the extent to which an individual interprets life events based on his/her religious views. The 10 items of the inventory are arranged on a 5-point Likert scale: not at all true of me (1) to the totally true of me (5). It has two subscales, namely intrapersonal religious commitment (cognitive focus) with 6 items and interpersonal religious commitment (behavioral focus) with 4 items. Examples of items of the scale include: “my religious beliefs lie behind my whole approach to life” (intrapersonal) and “I enjoy working in the activities of my religious organisation” (interpersonal). As reported by Worthington et al., scores on the RCI–10 had strong estimated internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .93 to .96. Cronbach’s α of the subscales was .92 (intrapersonal religious commitment) and .87 (interpersonal religious commitment). The measure had been found to be reliable and valid in a previous study in Nigeria (see Chukwuorji et al. 2017). In the current study, α for the full scale was .93, while α for the subscales was .88 and .86, for intrapersonal religious commitment and interpersonal religious commitment, respectively.

The 10-item Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross and John 2003) was used to measure the habitual use of two emotion regulation strategies, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression, by the patients. Sample items include: “When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that makes me stay calm” (cognitive reappraisal) and “when I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them” (expressive suppression). Respondents are expected to answer using a 5-point Likert scale of strongly disagree (1), to strongly agree (5). The subscales’ scores are summed separately. Both the cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression subscales had very acceptable internal consistency reliability estimates of Cronbach’s α values ranging from .68 to .85, and 3-month test–retest reliability of r = .68 (Kulkarni 2010). In the present study, we obtained an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = .93 for the full scale, with .89 for cognitive reappraisal and .82 for suppression subscales.

The 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988) was used to measure perceived social support from family, friends and significant others. It is scored on a 5-point Likert-type structure from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” Sample items on the scale include “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family,” “I can count on my friends when things go wrong,” “There is a special person who is around when I am in need.” The internal consistency of MSPSS (Cronbach’s alpha) was .89 (Zimet et al. 1988). In the current study, Cronbach’s α was observed as .82. The composite scores, rather than the subscale scores, were used in this study. Higher scores reflect higher perceived support, while lower scores reflect lower perceived support.

Procedure for Data Collection

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the institutional research ethics committee of the hospital where the study was conducted. Administration of the questionnaire to patients was done 24 h before each patient’s surgery by a trained research assistant after obtaining informed consent from each patient. The choice of this time interval is consistent with studies conducted in this area (e.g., Karanci 2003; Nigussie et al. 2014). The study was carried out over a period of 3 months and 15 days. Within this period, the total number of adult patients admitted for surgery in the hospital was 518. Four hundred and five (405) met the inclusion criteria for the study, but only the 228 patients who were willing to participate in the study were given the questionnaire for completion. Out of 228 copies of the questionnaire distributed, 210 were returned and properly completed. Responses from the 210 copies of the questionnaire were used for data analysis.

Design/Statistical Analysis

This was a cross-sectional survey research. Pearson’s correlation was employed to check the a priori relationship between the demographic factors and predictor variables with anxiety. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses, with step-wise method. Hierarchical multiple regression is suitable for test of association among variables (see some recent examples: Goulet et al. 2017; Litman et al. 2017; Vizehfar and Jaberi 2017; Wirth and Büssing 2016), and it is not less efficacious than partial correlation, but rather has an advantage where confounding variables are to be controlled for in the analysis. Regression also gives variance in the outcome variable explained by each factor and enables comparisons of the contribution of each factor in explaining the obtained variance (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). Following Shiah et al. (2015) suggestions, probable contaminating effects of demographic variables that correlated significantly with preoperative anxiety were controlled for in the analysis by extracting their effect first, before building the main predictors into the regression model. The theoretical basis for the order of entry of the factors was the Anxiety Sensitivity Theory (AST) as discussed earlier. Step 1 included the control variables, while emotion regulation strategies, social support and religious commitment were added in steps 2, 3 and 4, respectively.

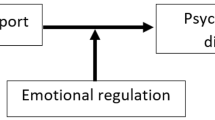

Although it is not our major aim in this study, we adopted the Hayes (2013) regression base macro for SPSS to examine whether social support mediated the association between religious commitment and preoperative anxiety. Some studies have indicated that church attendance and spirituality were indirectly associated with specific indicators of mental health via various forms of social support (Dangel and Webb 2017; Van Olphen et al. 2003). Similarly, The buffering model of social support indicates that supportive relationships may encourage the use of a more effective emotion regulation strategy (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) and less use of ineffective strategies (e.g., expressive suppression), thereby reducing an event’s adverse impacts on personal well-being (Cobb 1976; Cohen and Wills 1985). Some empirical research in this regard has found that emotion regulation mediates the relationship between social support and psychopathology (Marroquín and Nolen-Hoeksema 2015; Rami 2013; Zhou et al. 2016). The mediation by emotion regulation strategies for the association between social support and preoperative anxiety was also analyzed in the present study.

Results

The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 80 years, with a mean age of 34.05 years (SD = 10.36). They consisted of 93 men (44.3%) and 117 women (55.7%), of whom 82 (39%) were single, while 113 (53.8%) were married. By level of education, 53 (25.2%) acquired secondary education, while 157 (74.8%) had tertiary education. For employment status, 116 (55.2%) were employed while 94 (44.8%) were unemployed. One hundred and eighty (108, representing 85%) had been hospitalized before, while 30 (representing 14.3%) had never been hospitalized before. The patients were classified according to the types of surgery (i.e., surgical procedure or degree of surgery) using the Hohn system (Hohn 1972) into minor surgery (74 patients, 35.7%), medium surgery (75 patients, 35.7%) or major surgery (61 patients, 29%).

In Table 1, interpersonal religious commitment was negatively correlated with intrapersonal religious commitment and expressive suppression, but it was positively related to cognitive reappraisal and social support. Intrapersonal religious commitment had a significant positive relationship with expressive suppression and negative relationships with cognitive reappraisal and social support. Cognitive reappraisal correlated negatively with expressive suppression and was positively correlated with social support. Expressive suppression also had a negative relationship with social support. Preoperative anxiety was associated with being a woman, having a major surgery, lower interpersonal religious commitment, higher intrapersonal religious commitment, lower cognitive reappraisal, lower social support and higher expressive suppression.

In this study, only the confounding variables that correlated significantly with preoperative anxiety (gender and type of surgery in Table 1) were entered into the regression analysis. After entering the covariates in the first step of the regression model, the major variables of interest in the study were entered based on the theoretical postulations, and as guided by the results of inter-factor correlations of the variables in Table 1. Expressive suppression had the highest inter-factor correlation and so the emotion regulation strategies were entered into the second step of the regression model. Social support was entered into the third model because it had the second highest inter-factor loading and then came the religious commitment dimensions which were included in the fourth model.

Table 2 shows that the covariates were positively associated with preoperative anxiety. The positive relationship implies that women reported higher preoperative anxiety than men, and patients who had major surgery reported higher anxiety. About 21% of the variance in preoperative anxiety was explained on account of the covariates. The predictor variables, except intrapersonal religious commitment, were significantly associated with preoperative anxiety even when the control variables have been accounted for. Cognitive reappraisal was negatively associated with preoperative anxiety. This suggests that the less the use of cognitive reappraisal of surgery, the more likely the patients would experience higher preoperative anxiety. Expressive suppression was positively associated with preoperative anxiety, suggesting that the greater the use of expressive suppression, the higher the preoperative anxiety. The two emotion regulation strategies contributed 32% in explaining the entire variance in preoperative anxiety. Social support was negatively associated with preoperative anxiety, suggesting that patients who received less social support from their social network are likely to experience higher anxiety. Social support explained 3% of the variance in preoperative anxiety. Interpersonal religious commitment was significantly positively associated with preoperative anxiety, showing that the higher the interpersonal religious commitment, the higher the preoperative anxiety. Intrapersonal religious commitment was not associated with preoperative anxiety in the regression model. The two dimensions of religious commitment accounted for 2% of the variance in preoperative anxiety.

The Hayes PROCESS macro uses a regression-based path analytic approach in its results. If the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (CI) for any of the paths does not include zero at the middle of the lower and upper limits, it means that a mediation effect exists. Based on the results obtained, the indirect effect of interpersonal RC on preoperative anxiety through increased social support (interpersonal RC → social support → preoperative anxiety) was -.33, 95%CI = [− .44, − .28]. The indirect effect of intrapersonal RC (intrapersonal RC → social support → preoperative anxiety) was .27, 95%CI = [.19, .33]. When the mediating roles of emotion regulation strategies in the relationship between social support and preoperative anxiety were tested, there were mediations for the two paths. Social support had an indirect negative effect on preoperative anxiety via increasing cognitive reappraisal (social support → cognitive reappraisal → preoperative anxiety), β = .14, 95%CI = [− .17, − .02]. Social support had an indirect negative effect on preoperative anxiety via reducing expressive suppression (social support → expressive suppression → preoperative anxiety), β = − .23, 95%CI = [− .32, − .11].

Discussion

This study investigated the roles of religious commitment (interpersonal religious commitment and intrapersonal religious commitment), emotion regulation (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) and social support in preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients. The results showed that cognitive reappraisal was negatively associated with preoperative anxiety. Thus, the hypothesis which stated that cognitive reappraisal will be negatively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients was confirmed. This suggests that patients who replace their worries about surgery with thoughts about the positive aspects of the hospital experience and rehearse these positive thoughts experience lower anxiety before surgery. This finding is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Garnefski et al. 2002) which showed that patients who utilized more of cognitive reappraisal of surgery had less preoperative anxiety symptoms. Cognitive reappraisal has been associated with less negative emotional experience, greater positive emotional experience, a greater capacity for negative mood repair, higher self- rated adjustment, higher self-rated and peer-rated social functioning as well as increased pain tolerance, adaptive patterns of cardiovascular responding and less incidence of anxiety during surgery (Campbell-Sills et al. 2006; Gross and John 2003). Our study has gone further to show that social support could strengthen the negative association of cognitive reappraisal with preoperative anxiety.

The results of the study also revealed that expressive suppression was positively associated with preoperative anxiety. The hypothesis which stated that expressive suppression will be positively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients was confirmed. This finding is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Watson et al. 2011) which concluded that patients with emotion suppression tend to feel hopelessness and had a fatalistic attitude. Suppression of negative emotion has been seen as maladaptive because it enhances subjective negative affect and physiological arousal (Gross 2002; Richards et al. 2003; Richards and Gross 2000). The results of this study, however, showed that social support could mitigate the worsening association of expressive suppression with preoperative anxiety.

The results showed that social support was negatively associated with preoperative anxiety. Thus, the hypothesis which stated that social support will be negatively associated with preoperative anxiety among surgical inpatients was confirmed. Social support has been found in previous studies to be helpful in similar populations (e.g., Kelly et al. 2017; Koivula et al. 2002; Parent and Fortin 2000; Power et al. 2016). Thus, knowing that others are available to lend a helping hand when needed is found to be an important social resource (Schroder et al. 1997). It appears that the quality of care received from the family and healthcare providers is very essential in determining the patient’s psychological well-being. Caring for people as individuals rather than as a component of a patient population minimizes the psychological distress associated with surgery (Dodds 1993). Offering assurance and provision of accurate and honest information for patients could be an important source of social support to surgical inpatients.

As hypothesized, we found that interpersonal religious commitment was negatively associated with preoperative anxiety. This finding is consistent with previous research (e.g., DeFiguereido and Lemkau 1978), showing that anxiety symptoms were negatively related to public religious participation. Attendance at religious services has been reported to be potentially the most effective anxiety-buffering mechanism within the samples (Lavrič and Flere 2010). However, some past research (e.g., Bergin et al. 1987) had indicated that externally oriented religious commitment was associated with higher anxiety symptoms. The present finding is also further clarified by the positive correlation between cognitive reappraisal and interpersonal religious commitment. Apparently, interpersonal religious commitment may provide the social reconstruction of meaning in the course of an illness which makes it to be helpful in alleviating anxiety before surgery. It may provide a path to social support.

The hypothesized negative association of preoperative anxiety with intrapersonal religious commitment was not supported by the results of this study. This result is inconsistent with previous findings (e.g., Perks et al. 2009; Pressman 2000) which showed that people to whom God was a strong source of strength and comfort had low anxiety before surgery and could walk farther at discharge from hospital than patients who lack strong spiritual/religious commitment. However, another study (Kalkhoran and Karimollahi 2007) had reported that religious beliefs were not significantly associated with preoperative anxiety. It is possible that religious beliefs may not have received the needed reinforcement to effectively have impact on preoperative anxiety in the current sample. Without this reinforcement, patients would not adopt religious faith as a form of coping. They may have chosen to use other psychological and social resources that as coping mechanisms. Since our study included some other variables, it is possible that the contribution of religious beliefs in anxiety diminishes when stronger factors are considered. Some research in other samples (e.g., Peterman et al. 2014) had found that variables associated with practice rather than personal belief predicted anxiety.

Among the control variables, type of surgery was noticed to be positively related to preoperative anxiety. The positive relationship implies that individuals who had major surgery were prone to experience higher anxiety than other patients who had moderate and minor surgeries. This finding is in line with previous studies (Nigussie et al. 2014). This may be explained by patients’ knowledge and expectations about their surgery. Gender was also found to be related to preoperative anxiety with females experiencing higher anxiety. This also lends support to previous findings on gender differences in preoperative anxiety (Mitchell 2013; Nigussie et al. 2014). Thus, female patients scheduled for surgeries may need special care in order to help them deal with the psychological distress associated with surgery.

In addition to the use of sedatives in relaxing surgical patients, psychological interventions such as stress inoculation training, biofeedback training, cognitive behavior therapy and training in progressive deep muscle relaxation that have been found to generally reduce anxiety in various contexts could be applied to help relieve patients of their anxiety. Psychosocial interventions can incorporate religious-based psychological interventions as it could serve as one of the non-pharmacological anxiety management techniques for reducing anxiety among surgical inpatients.

The result of this study can be used as evidence for presenting preoperative psychological interventions via cognitive reappraisal to surgical inpatients as it would have significant clinical benefit. Even as most African countries are characterized by collectivistic cultural norms, which encourage the suppression of emotional displays in order to avoid offending others and maintain relational harmony, it is important to recognize that suppression is often unhelpful for one’s mental health. Since surgery is seen as a stressful event, clinical intervention of patients with expressive suppression should focus on how to encourage surgical inpatients to assertively express their negative emotions and feelings. There is also need for the medical personnel to understand the regulatory patterns of surgical inpatients including expressive suppression in the early stage of hospitalisation so that such patients can be encouraged to moderately express their negative emotions and feelings in order to reduce their anxiety. It is also needful for healthcare providers to understand the importance of encouraging quality social support from family and friends during the surgical experience.

Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Further Research

One limitation of this study is the limited scope of the sample. The study was carried out in one teaching hospital located in South-Eastern Nigeria where the population is predominantly of Igbo ethnic group and mainly Christians. As a result, a cautious generalization of the findings is warranted. Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study which may have introduced the error of common method bias.

Future studies should extend this research to other hospitals located in other geographical locations in Nigeria, especially the north where Muslims abound. This will help in the generalization of its findings given that religious commitment was a strong predictor of anxiety in this study. Future studies could also adopt longitudinal design in order to obtain data at multiple intervals on the study variables.

Conclusion

The identification of patients who are more likely to experience adverse levels of pre- and postoperative anxiety could be important as it would enable the development and implementation of anxiety reduction interventions whose effectiveness could then be assessed (Mccrone et al. 2001). Apart from the benefits of the anxiety reduction interventions on the patients’ psychological well-being, targeting a high risk group as opposed to the whole patients’ population may be seen as a better utilization of scarce resources. Since research has shown that psychosocial variables are important predictors of preoperative anxiety as established in the present study, the researcher is of the opinion that collaboration among healthcare professionals would ensure the provision of suitable services that will enhance the recovery process and reduce the psychological distress experienced by surgical patients.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksoma, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review,30, 217–237.

Bergin, A. E., Masters, K. S., & Richards, P. S. (1987). Religiousness and psychological well-being re-considered: A study of an intrinsically religious sample. Journal of Psychiatry,34, 197–204.

Campbell-Sills, L., Barlow, D. H., Brown, T. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behavioural Research Therapy,44, 1251–1263.

Caumo, W., Schmidt, A. P., Schneider, C. N., Bergmann, J., Iwamoto, C. W., Bandeir, D., et al. (2001). Risk factors for preoperative anxiety in adults. Acta Anaesthesiological Scandinavia,45(3), 298–307.

Chukwuorji, J. C., Ituma, E. A., & Ugwu, L. E. (2017). Locus of control and academic engagement: Mediating role of religious commitment. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9546-8.

Clements, A. D., Fletcher, T. R., Cyphers, N. A., Ermakova, A. V., & Bailey, B. (2015). RSAS-3: Validation of a very brief measure of religious commitment for use in health research. Journal of Religion and Health,54(1), 134–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9791-1.

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine,38(5), 300–314.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin,98(2), 310–357.

Dangel, T., & Webb, J. R. (2017). Spirituality and psychological pain: The mediating role of social support. Mental Health, Religion and Culture,3, 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2017.1345880.

de Souza, J., Magalhaes, R. C., Arnault, D. M. S., de Oliveira, J. L., Assad, F. B., et al. (2017). The role of social support for patients with mental disorders in primary care in Brazil. Issues in Mental Health Nursing,38(5), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1271483.

DeFiguereido, J. M., & Lemkau, P. V. (1978). The prevalence of psychosomatic symptom in a rapidly changing bilingual culture: An exploratory study. Social Psychiatry,13, 125–133.

Dodds, F. (1993). Access to the coping strategies managing anxiety in elective surgical patients. Professional Nurse,10, 45–52.

Frazier, S. K., Moser, D. K., Daley, L. K., McKinley, S., Riegel, B., et al. (2003). Critical care nurses’ beliefs about and reported management of anxiety. American Journal of Critical Care,12(1), 19–27.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2002). Manual for the use of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Leiderdorp: Datec.

Gartner, J., Larsen, D. B., & Allen, G. D. (1991). Religious commitment and mental health: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology,19(1), 6–25.

Goulet, C., Henrie, J., & Szymanski, L. (2017). An exploration of the associations among multiple aspects of religiousness, body image, eating pathology, and appearance investment. Journal of Religion and Health,56(2), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0229-4.

Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,74, 224–237.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology,39, 281–291.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,85, 348–362.

Guo, P. (2015). Preoperative education interventions to reduce anxiety and improve recovery among cardiac surgery patients: A review of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Nursing,24(1–2), 34–46.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hayes, J. P., Morey, R. A., Petty, C. M., Seth, S., Smoski, M. J., McCarthy, G., et al. (2010). Staying cool when things get hot: Emotion regulation modulates neural mechanisms of memory encoding. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience,4, 230–238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2010.00230.

Heilmann, C., Stotz, U., Burbaum, C., Feuchtinger, J., Leonhart, R., et al. (2016). Short-term intervention to reduce anxiety before coronary artery bypass surgery—A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing,25(3–4), 351–361.

Hohn, H. G. (1972). Operationskatalog fur Betriebswergleiche [Operation Catalog for Betriebswergleiche]. Krankenhausumschau,2, 134–146.

Isaacs, K. B., & Hall, A. (2011). A psychometric analysis of the functional social support questionnaire in low-income pregnant women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing,32(12), 766–773. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.610561.

Kalkhoran, M. A., & Karimollahi, M. (2007). Religiousness and preoperative anxiety: A correlational study. Annals of General Psychiatry,6, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-6-17.

Karanci, A. (2003). Predictors of pre- and postoperative anxiety in emergency surgery patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research,55, 363–369.

Kelly, M. E., Duff, H., Kelly, S., Power, J. E. M., Brennan, S., Lawlor, B. A., et al. (2017). The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. BMC Systematic Reviews,6, 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2.

Koivula, M., Paunonen-Ilmonen, M., Tarkka, M. T., Tarkka, M., & Laippala, P. (2002). Social support and its relation to fear and anxiety in patients awaiting coronary artery bypass grafting. Journal of Clinical Nursing,11(5), 622–633.

Kulkarni, M. R. (2010). Childhood violence exposure on emotion regulation and PTSD in adult survivors. Ph. D thesis. Department of Psychology, University of Michigan.

Larson, D. B., Sherrill, K. A., Lyons, J. S., Craigie, E. F., Jr., Thielman, S. B., Greenwold, M. A., et al. (1992). Associations between dimensions of religious commitment and mental health reported in the American Journal of Psychiatry and Archives of General Psychiatry: 1978–1989. American Journal of Psychiatry,149, 557–559.

Lavrič, M., & Flere, S. (2010). Trait anxiety and measures of religiosity in four cultural settings. Mental Health, Religion & Culture,13(7–8), 667–682.

Litman, L., Robinson, J., Weinberger-Litman, S. L., & Finkelstein, R. (2017). Both intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation are positively associated with attitudes toward cleanliness: Exploring multiple routes from godliness to cleanliness. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0460-7.

Marroquín, B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2015). Emotion regulation and depressive symptoms: Close relationships as social context and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,109, 836–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000034.

Mccrone, S., Lenz, E., Tarzian, A., & Perkins, S. (2001). Anxiety and depression: Incidence and patterns in patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Applied Nursing Research,14(3), 155–164.

McMurray, A., Johnson, P., Wallis, M., Patterson, E., & Griffiths, S. (2007). General surgical patients’ perspectives of the adequacy and appropriateness of discharge planning to facilitate health decision-making at home. Journal of Clinical Nursing,16(9), 1602–1609.

McNally, R. J. (1994). Panic disorder: A critical analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Meara, J. G., Leather, A. J., Hagander, L., Alkire, B. C., Alonso, N., Ameh, E. A., et al. (2015). Global surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet,158, 3–6.

Mitchell, M. (2004). Methodological challenges in the study of psychological recovery from modern surgery. Nurse Research,12(1), 64–77.

Mitchell, M. (2013). Anaesthesia type, gender and anxiety. Journal of Perioperative Practice,23(3), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/175045891302300301.

Mitchinson, A. R., Kim, H. M., Geisser, M., Rosenberg, J. M., & Hinshaw, D. B. (2007). Social connectedness and patient recovery after major operations. Journal of American College of Surgery,206(2), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.08.017.

Mouch, C. A., & Sonnega, A. J. (2012). Spirituality and recovery from cardiac surgery: A review. Journal of Religion and Health,51(4), 1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9612-y.

Nadeem, M., Ali, A., & Buzdar, M. A. (2017). The association between Muslim religiosity and young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, and stress. Journal of Religion and Health,56(4), 1170–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0338-0.

Nigussie, S., Belachew, T., & Wolancho, W. (2014). Predictors of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients in Jimma university specialized teaching hospital, South Western Ethiopia. BMC Surgery,14(67), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-14-67.

Parent, N., & Fortin, F. (2000). A randomized, controlled trial of vicarious experience through peer support for male first-time cardiac surgery patients: Impact on anxiety, self-efficacy expectation, and self-reported activity. Heart and Lung,29(6), 389–400.

Perks, A., Chakravarti, S., & Manninen, P. (2009). Preoperative anxiety in neurosurgical patients. Journal of Neurosurgery and Anesthesiology,21(2), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANA.0b013e31819a6ca3.

Peterman, J. S., LaBelle, D. R., & Steinberg, L. (2014). Devoutly anxious: The relationship between anxiety and religiosity in adolescence. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality,6(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035447.

Phipps, W., Long, B., & Woods, N. F. (2004). Medical surgical nursing. St Louis: CV Mosby Co.

Ping, G., Linda, E., & Antony, A. (2012). A preoperative education intervention to reduce anxiety and improve recovery among Chinese cardiac patients: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies,49(2), 129–137.

Power, J. M., Carney, S., Hannigan, C., Brennan, S., Wolfe, H., Lynch, M., et al. (2016). Systemic inflammatory markers and sources of social support among older adults in the memory research unit cohort. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316676331.

Pressman, P. (2000). Religious belief, depression, and ambulation status in elderly women with broken hips. American Journal of Psychiatry,147(6), 758–760.

Rami, S. (2013). Social support, emotional well-being, and emotion regulation: A mediation model. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science with honors in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan.

Reis, S., & McNally, R. J. (1985). The expectancy model of fear. In S. Reiss & R. R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behavior therapy. New York: Academic Press.

Reiss, S. (1991). The expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clinic Psychology Review,11, 141–153.

Richards, J. M., Butler, E. A., & Gross, J. J. (2003). Emotion regulation in romantic relationships: The cognitive consequences of concealing feelings. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,20, 599–620.

Richards, J. M., & Gross, J. J. (2000). Emotion regulation and memory: The cognitive costs of keeping one’s cool. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,79, 410–424.

Schroder, K. E., Schwarzer, R., & Endler, N. S. (1997). Predicting cardiac patients’ quality of life from the characteristics of their spouse. Journal of Health Psychology,2(2), 231–244.

Shiah, Y. J., Chang, F., Chiang, S. K., Lin, I.-M., & Tam, W. C. (2015). Religion and health: Anxiety, religiosity, meaning of life and mental health. Journal of Religion and Health,54(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9781-3.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, P., Vagg, P., & Jacobs, A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Swindale, J. E. (2004). The nurse’s role in giving pre-operative information to reduce anxiety in patients admitted to hospital for elective minor surgery. Journal of Advanced Nursing,14, 899–905.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In M. S. Friedman (Ed.), The handbook of health psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Van Olphen, J., Schulz, A., Israel, B., Chatters, L., Klem, L., Parker, E., et al. (2003). Religious involvement, social support, and health among African-American Women on the East Side of Detroit. Journal of General and Internal Medicine,18(7), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21031.x.

Vizehfar, F., & Jaberi, A. (2017). The relationship between religious beliefs and quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Religion and Health,56(5), 1826–1836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0411-3.

Watson, M., Haviland, J. S., Greer, S., Davidson, J., & Bliss, J. M. (2011). Influence of psychological response on survival in breast cancer: A population-based cohort study. Lancet,354(13), 31–37.

Wirth, A. G., & Büssing, A. (2016). Utilized resources of hope, orientation, and inspiration in life of persons with multiple sclerosis and their association with life satisfaction, adaptive coping strategies, and spirituality. Journal of Religion and Health,55(4), 1359–1380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0089-3.

Worthington, E., Wade, N., Hight, T., Ripley, J., McCullough, M., Berry, J., et al. (2003). The religious commitment inventory-10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology,50(1), 84–96.

Yilmaz, M., Sezer, H., Gürler, H., & Bekar, M. (2011). Predictors of preoperative anxiety in surgical inpatients. Journal of Clinical Nursing,21(78), 956–964.

Zhou, X., Wu, X., & Zhen, R. (2016). Understanding the relationship between social support and posttraumatic stress disorder/posttraumatic growth among adolescents after Ya’an earthquake: The role of emotion regulation. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research Practice, and Policy,9(2), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000213.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment,52, 30–41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aliche, J.C., Ifeagwazi, C.M., Chukwuorji, J.C. et al. Roles of Religious Commitment, Emotion Regulation and Social Support in Preoperative Anxiety. J Relig Health 59, 905–919 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0693-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0693-0