Abstract

This study has two goals. The first is to assess whether a benevolent image of God is associated with better physical health. The second goal is to examine the aspects of congregational life that is associated with a benevolent image of God. Data from a new nationwide survey (N = 1774) are used to test the following core hypotheses: (1) people who attend worship services more often and individuals who receive more spiritual support from fellow church members (i.e., informal assistance that is intended to increase the religious beliefs and behaviors of the recipient) will have more benevolent images of God, (2) individuals who believe that God is benevolent will feel more grateful to God, (3) study participants who are more grateful to God will be more hopeful about the future, and (4) greater hope will be associated with better health. The data provide support for each of these relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The images that people have of God (i.e., their internal working models of God) are foundational elements of religious life because these perceptions shape a number of other religious beliefs and behaviors. Included among the religious beliefs and behaviors that are influenced by God images are the frequency of private prayer (Bradshaw et al. 2008), the content of prayers (e.g., petitionary prayers, prayers of thanksgiving; see Lazar 2014), the willingness to forgive (Johnson et al. 2013), the choice of religious coping responses (Maynard et al. 2001), religious doubt (Exline et al. 2015), and the level of religious commitment (Wong-McDonald and Gorsuch 2004). These findings are important because they form the basis of the current study. Literally hundreds of studies suggest that greater involvement in religion is associated with better health (Koenig et al. 2012). If religion affects health and if God images are a foundational element of religious life, then the images that people have of God should be associated with their health.

Despite the straightforward nature of this reasoning, it is surprising to find there is relatively little research on God images and physical health. So far, the majority of studies focus on the relationship between God images and various indicators of psychological well-being and distress. For example, Braam et al. (2008) report that God images are associated with depressive symptoms, Steenwyk et al. (2010) provide evidence that positive images of God are associated with greater life satisfaction, and happiness, and Khosravi et al. (2011) find that positive God images are associated with less pathological guilt. There appear to be only two studies on God images that focus specifically on physical health outcomes. The first deals with women who are being treated for breast cancer (Gall et al. 2009), while the second is concerned with the progression of disease among people with HIV (Ironson et al. 2011). Both studies show that positive God images are associated with a more favorable course of disease. These studies clearly make a contribution to the literature, but they are based on clinic samples and as a result, it is not clear whether God images are associated with physical health in the general population.

The purpose of the current study is to use data from a new nationwide survey to evaluate the relationship between benevolent images of God and two widely used measures of physical health status: self-rated health and a checklist of symptoms that are associated with physical illness. This core issue is embedded in a larger conceptual model that was designed to contribute to the literature in two potentially important ways. First, an effort is made to see how benevolent images of God arise in religious settings. Participation in formal worship services and informal support from fellow church members figure prominently in this respect. Second, feelings of gratitude to God and hope serve as mediators that explain how God images influence health. This conceptual model and the theoretical principles upon which it is based are presented in the next section.

A Conceptual Model of God Images and Health

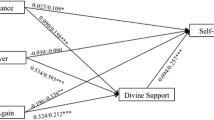

The latent variable model that was developed for this study is depicted in Fig. 1. Two steps were taken to simplify the presentation of this complex theoretical scheme. First, the elements of the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are not shown in this diagram even though a full measurement model was estimated when this conceptual scheme was evaluated empirically. Second, the model in Fig. 1 was assessed after the effects of age, sex, education, and marital status are controlled statistically (i.e., treated as exogenous variables).

All of the paths in Fig. 1 were estimated during the data analytic phase of this study (i.e., a fully saturated model was estimated). However, in order to keep the focus on the conceptual core of this study, the discussion that follows is solely concerned with the following hypotheses: (1) people who attend worship services more often and individuals who receive more spiritual support from fellow church members will have more benevolent images of God, (2) people who believe that God is benevolent will feel more grateful to God, (3) individuals who are more grateful to God will be more hopeful about the future, and (4) greater hope will be associated with better health. The theoretical rationale for each of these relationships is provided below.

Church Attendance, Spiritual Support, and God Images

A number of investigators maintain that God images are formed early in life when children interact with their parents (Kirkpatrick 2005). A basic premise in the current study is that even though early childhood experiences are important, development continues throughout the life course (Settersten and Trauten 2009). Consequently, God images are likely to be influenced by contemporaneous factors, as well. The perspective that is evaluated in Fig. 1 is consistent with Berger’s (1967) classic insight on the social construction and maintenance of religious world views. Rather than being cast in stone during childhood, Berger (1967) maintains that religious beliefs arise and are maintained only if they are continuously reinforced during interaction with like-minded others. More specifically, he argues that religious world views, “… are socially constructed and socially maintained. Their continuing reality, both objective… and subjective depends upon specific social processes, namely those processes that ongoingly reconstruct and maintain the world in question” (Berger 1967, p. 45).

If God images are a foundational element of religious life and if the roots of religious belief arise during interaction with like-minded others, then it makes sense to look for the basis of God images in the social life of the church. Two measures were included in Fig. 1 to evaluate this reasoning. The first is attendance at worship services. Images of God are evoked at numerous points in church services, including sermons, congregational prayers, and lyrics in religious songs. This is one reason why Stark and Finke (2000) maintain that confidence in religious world views, “… increases to the extent that people participate in religious rituals” (p. 107).

But church services are not the only way in which images of God may be reinforced: informal sources of influence may be at work, as well. This is why a measure of informal spiritual support from fellow church members was included in the study model. Spiritual support is informal assistance provided by like-minded others for the explicit purpose of bolstering and maintaining the religious beliefs and behaviors of the recipient (Krause 2008). If God images are a core aspect of religious life, then these perceptions are likely to be discussed during informal interaction among the faithful. Support for this notion may once again be found in theoretical framework that was developed by Stark and Finke (2000). Referring to religious world views as “religious explanations,” they argue that “An individual’s confidence in religious explanations is strengthened to the extent that others express their confidence in them” (Stark and Finke 2000, p. 107).

As discussed below, the image of God that is assessed in this study deals with the extent to which people believe in a benevolent God. This particular image of God is important because research provided by Stark (2008) suggests that the majority of Americans believe that God is benevolent: “It is… apparent that Americans tend to prefer the more benevolent and engaged God to the severe God of judgement” (Stark 2008, p. 77).

Juxtaposing the influence of church attendance and spiritual support provides an opportunity to obtain greater insight into the way in which religious life may influence images of God. There are three ways in which the effects of church attendance and spiritual support might be manifested. First, more frequent attendance at worship services may foster more benevolent views of God. Second, images of God may arise from spiritual support that is provided informally by fellow church members. Third, both attendance at church services and informal spiritual support may be associated with the way people view God.

God Images and Feeling Grateful to God

Findings from four nationwide surveys that were conducted by Barna (2006) suggest that between 71 and 72 % of the people in the USA believe that God is the all-powerful ruler of the world. If people believe that God is the all-powerful ruler of the world and if they believe that God is benevolent, then these beliefs are likely to evoke strong emotions. According to the model in Fig. 1, these emotions will involve feeling grateful to God. There are two closely related reasons why benevolent God images are likely to promote feelings of gratitude to God. First, if people view God as benevolent, then by definition, they believe that God is kind, generous, and merciful. People are more likely to feel this way if they have been recipients of God’s kindness, generosity, and mercy in the past. This is why some researchers define gratitude toward God as feelings of thankfulness for the benefits that God has bestowed (Krause and Ellison 2009). Many world religions commend gratitude as a desirable trait, and this emphasis may cause spiritual or religious people to adopt a grateful outlook (Lundberg 2010). Upon recognition of God’s provision of benefits, people respond with grateful affect and gratitude is one of the most common religious feelings.

The second reason why God images are likely to evoke feelings of gratitude to God follows from the first. If an individual has received benefits from someone in the past, they will typically take steps to insure these benefits will be forthcoming in the future. One way to increase the likelihood that a supportive person will continue to provide benefits in the future is to express feelings of gratitude for what he or she has already given. Evidence that expressions of gratitude help insure future benefits comes from two sources. The first is the classic sociological work on gratitude by Simmel (1964), which focuses on the preservation of social bonds between human beings. He maintained that social relationships would cease to exist were it not for expressions of gratitude: “If every grateful action, which lingers on from good turns received in the past, were suddenly eliminated, society (at least as we know it) would break apart” (Simmel 1964, p. 389). McCullough et al. (2001) reviewed evidence demonstrating that gratitude functions to reinforce further feelings gratitude: when expressed, it encourages benefactors toward continued generosity. The second source speaks more directly to the importance of expressing gratitude to God specifically. Krause et al. (2012) report that the majority of the participants in their qualitative study believe it is important to express feelings of gratitude to God because doing so insures the continuation of benefits in the future.

Gratitude to God and Hope

Research by McCullough et al. (2002) suggests that grateful people are more hopeful about the future. Although this research was conducted with American college students, similar findings have emerged in diverse cultural settings, such as China (Jiang et al. 2015) and Iran (Lashani et al. 2012). Moreover, a strong correlation between gratitude and hope has been observed with parents of grade school children (Hoy et al. 2013). Further support for the notion that gratitude is associated with hope and optimism comes from an experiment by Emmons and McCullough (2003). These investigators report that people who were asked to count their blessings (the treatment group) were more optimistic about the future than members of the control group.

Two limitations can be found in research on gratitude and hope. First, none of the studies that have been discussed so far deal specifically with gratitude to God and hope. Instead, this work focuses primarily on state gratitude. An effort is made in the current study to address this gap in the literature by focusing specifically on gratitude to God and hope. The second limitation in current research has to do with the fact that it is not entirely clear why people who are more grateful should also be more hopeful about the future.

There are two reasons why grateful people should be more hopeful. The first reason is found in the stress and coping literature. As Watkins (2014) points out, a number of studies suggest that people who are more grateful tend to cope more effectively with stressful events. This occurs, in part, because people who are grateful are able to keep the problems they encounter in perspective by viewing stressors in conjunction with the positive experiences that have evoked their feelings of gratitude. So if grateful people cope more effectively with stress, then knowing they possess strong coping skills should make them feel they are in better position to deal with whatever might happen in the future. Facing the future with greater confidence should make grateful people feel more hopeful.

The second reason why gratitude and hope might be related may be found by reflecting on feelings of gratitude to God specifically. By definition, people will feel grateful to God if they believe that God has provided them with benefits in the past. This is important because research consistently reveals that past behavior is one of the best predictors of behavior in the future. As Ouellette and Wood (1998) observe, this relationship is widely regarded as one of the basic truisms in psychology. It follows from this that people will feel that God will continue to help them in the future if He has helped them in the past. So if people believe that the all-powerful ruler of the world stands ready to help them in the future, it is not hard to see why they will feel more hopeful.

Hope and Physical Health

A growing number of studies suggest that greater hope and optimism are associated with better physical health (Krause and Hayward 2014; Rasmussen et al. 2009; Scioli et al. 1997; Snyder 2002). There are three reasons why people who are more hopeful about the future are more likely to enjoy better health. First, people who are more hopeful typically have more to live for and as a result, they are more likely to take steps to extend their lives by engaging in beneficial health behaviors. Evidence in support of this may be found in a study by Feldman and Sills (2013). Their findings indicate that individuals who are more hopeful are more likely to engage in cardiovascular health-promoting behaviors. Second, people who are more hopeful are less likely to experience mental health problems (Gallagher and Lopez 2009). This is important because a number of studies suggest that mental health problems may play an etiological role in the onset of physical health problems (Cohen and Rodriguez 1995). Third, there is some evidence that optimism may have direct beneficial physiological effects on the body. As Carver and Scheier (2014) report, greater optimism is associated with lower levels of inflammation, better antioxidant levels, better lipid profiles, and lower cortisol responses to stress.

Methods

Sample

The data for this study come from the Landmark Spirituality and Health Survey, a nationwide face-to-face survey of adults age 18 and older who reside in the coterminous USA (i.e., residents of Alaska and Hawaii were excluded). The data for this study, which were completed in 2014, were collected by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) in Chicago. The NORC 2010 National Sampling Frame served as the basis for the sampling procedures. This sampling frame is based on two sources. First, the bulk of this database comes from postal address lists that are compiled by the United States Postal Service (USPS). Second, field employees were sent to enumerate all houses in areas where USPS address list was unavailable. Sampling was done in three stages. First, National Frame Areas (NFAs) were constructed. In essence, NFAs are formed from pooling counties and metropolitan areas into blocks of designated sizes. A total of 44 NFAs were selected with probabilities proportional to size. Then, in the second stage, NFAs were partitioned into segments consisting of Census tracts and block groups. Segments were selected with probabilities proportional to size. In the third stage, housing units were sampled with equal probabilities of selection within each segment and the occupants of these dwellings were recruited for the interviews. A detailed description of the sampling procedures is found on the study website (http://landmarkspirituality.sph.umich.edu/).

The response rate for the study was 50 %. The total number of completed interviews was 3010. The sample was broken down into three age groups: 18–40 (N = 1000), 41–64 (N = 1002), and age 65 and older (N = 1008).

Recall that spiritual support from fellow church members figures prominently in the study model. When the questionnaire for this study was developed, the members of the research team felt it did not make sense to ask people about support they receive at church if they never go to church or if they attend worship services only once or twice a year. Consequently, people who never go to church or attend church less than three times a year were excluded from the analyses presented below (N = 1215). The full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure was used to deal with item non-response. Consequently, a total of 1774 cases were available for analysis. Preliminary analyses revealed that the average age of the study participants is 53.1 years (SD = 18.7 years), approximately 38 % are men, 50.1 % were married at the time of the interview, and the average level of education was 13.5 years (SD = 3.1 years).

Measures

Table 1 contains the measures that are used in this study. The procedures that were used to code these indicators are provided in the footnotes of this table.

Physical Symptoms

Two measures of physical health status served as principal outcome measures in this study. The first was a 10-item checklist of symptoms that are associated with physical illness. This measure was devised by Magaziner et al. (1996). A count was obtained of the number of symptoms that were experienced by study participants in the 6 months prior to the interview (M = 2.0; SD = 2.2). A high score denotes more symptoms of physical illness.

Self-rated Health

The second health outcome in this study was self-rated health. This construct was assessed with two items that are used widely in the literature (e.g., Idler et al. 1999). The first indicator asks study participants to rate the overall status of their health, whereas the second asks them to compare their health to the health of people of their own age. A high score stands for a more favorable health rating (M = 5.4; SD = 1.2). The bivariate correlation between the two self-rated health items is .466 (p < .001).

Church Attendance

A single item was used to measure attendance at worship services during the year prior to the survey. This indicator was taken from the research of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group (1999). A high score represents more frequent church attendance (M = 6.8; SD = 1.7).

Spiritual Support

Three items were used to assess how often study participants receive spiritual support from their fellow church members. This measure was developed by Krause (2008). A high score indicates more frequent spiritual support (M = 7.8; SD = 2.4).

God Image

Three items that were developed by Ironson et al. (2011) were included in the survey to measure the extent to which study participants view God as benevolent. A high score on these indicators means people are more likely to believe that God is benevolent (M = 13.3; SD = 1.8).

Gratitude to God

Three measures that assess feeling grateful to God were taken from the work of Rosmarin et al. (2011). A high score on these items denotes more gratitude (M = 13.7; SD = 1.7).

Hope

Four indicators were included in the interview schedule to assess hope. The first two come from the scale that was developed by Scheier and Carver (1985). The other two items were developed by Krause (2002). A high score represents more hopeful study participants. A high score on these items represents greater hope (M = 16.3; SD = 2.4).

Demographic Control Variables

Recall that the relationships among the constructs in Fig. 1 were obtained after the effects of age, sex, education, and marital status were controlled statistically. Age and education were scored continuously in years, while sex (1 = men; 0 = women) and martial status (1 = currently married; 0 = otherwise) were scored in a binary format.

Results

The findings from this study are presented in three sections. Some technical issues involving the estimation of the study model are reported first. Reliability estimates for the multiple-item constructs are presented in section two. Section three contains the substantive findings that emerged from estimating the study model.

Model Estimation Issues

The study model was evaluated with the maximum likelihood estimator in version 8.80 of the LISREL statistical software program (du Toit and du Toit 2001). Researchers who use this estimator must assume that the observed indicators have a multivariate normal distribution. Preliminary tests (not shown here) indicated that this assumption had been violated in the current study. Although researchers have devised a number of strategies for dealing with departures from multivariate normality, the straightforward approach that is discussed by du Toit and du Toit (2001) was implemented in this study. These investigators report that departures from multivariate normality can be handled by converting raw scores for observed indicators to normal scores prior to estimating the model (du Toit and du Toit 2001, p. 143). Consequently, the analyses presented below are based on observed indicators that were normalized.

Because the FIML procedure was used to deal with item non-response, the LISREL software program provides only two goodness-of-fit measures. The first is the full information maximum likelihood Chi-square value (702.614; df = 140; p < .001). Unfortunately, this statistic is not very useful because it substantially underestimates the fit of the model to the data when samples are large, such as the sample in the current study. Better insight into the fit of the model to the data is provided by the second goodness-of-fit measure: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The RMSEA value for the model in Fig. 1 is .047. Researchers have yet to agree on an RMSEA cut point score for identifying a satisfactory fit of the model to the data. However, many follow the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (1999), who propose that values below .05 indicate a good fit. Based on their insights, the fit of the model to the data in the current study is acceptable.

Reliability Estimates

The factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from estimating the study model are presented in Table 2. These coefficients are important because they provide preliminary information about the reliability of the observed indicators that are used to measure the multiple-item latent constructs. Widaman (2012) proposes that items with standardized factor loadings in excess of .600 tend to have good reliability. The data in Table 2 indicate that the standardized factor loadings range from .610 to .895, suggesting that the reliability of the observed indicators is acceptable.

Even though the factor loadings and measurement error terms that are associated with the observed indicators provide useful information about the reliability of each item, it is also helpful to know the reliability of the scales as a whole. DeShon (1998) provides a formula that can be used to compute these estimates. This formula is based on the factor loadings and measurement error terms in Table 2. Applying the formula provided by DeShon (1998) to these data yields the following reliability estimates for the multiple-item constructs in Fig. 1: spiritual support (.829), God images (.854), gratitude to God (.873), and hope (.784). Taken as a whole, the data in this section indicate that the reliability of the multiple-item study measures is good.

Substantive Findings

The findings involving the relationships among the latent constructs are provided in Table 3. Taken as a whole, these data provide support for the core study hypotheses that were discussed earlier. More specifically, the findings indicate that more frequent church attendance (β = .077; p < .01) as well as more frequent spiritual support (β = .362; p < .001) are associated with having a more benevolent view of God. An additional test (not shown in Table 3) was conducted to see whether the magnitude of the relationship between spiritual support and a benevolent view of God is significantly larger than the corresponding relationship between church attendance and a benevolent image of God. This test involved the following steps. The data reported in Table 3 were derived when the relationships between church attendance and God images as well as spiritual support and God images were allowed to vary freely. This estimation produced the Chi-square value that was reported above. The model was then estimated a second time after the relationship between church attendance and a benevolent view of God was constrained to be equivalent to the relationship between spiritual support and God images. This produced a second Chi-square value (791.441; df = 141; p < .001). The difference between the two Chi-square values (88.827) was significant at the .001 level. This suggests that the estimate involving spiritual support is significantly larger than the corresponding estimate that involves church attendance. However, as additional analyses that will be presented below will suggest, the relationships among church attendance, spiritual support, and God images are more complex than these initial analyses indicate.

Returning to Table 3, the data indicate that individuals who have a more benevolent view of God are more likely to feel grateful to God than people who do not believe that God is benevolent (β = .578; p < .001). The size of this relationship is quite large by social and behavioral science standards. This is the primary reason why the variables in the study model explain 47.1 % of the variance in feeling grateful to God. The results in Table 3 further suggest that study participants who are more grateful to God also tend to be more hopeful about the future (β = .214; p < .001) and greater hope is, in turn, associated with more favorable health ratings (β = .330; p < .001) and fewer symptoms of physical illness (β = −.255; p < .001).

Additional analyses that have not been discussed up to this point suggest that the relationships between church attendance, spiritual support, and God images may be more complex than they seem initially. In order to see why this is so, it is helpful to return to some additional findings in Table 3. In order for people to receive spiritual support, they obviously must come into contact with their fellow church members. Attendance at worship services provides an opportunity for this type of interpersonal contact to take place. Consistent with this notion, the data in Table 3 indicate that more frequent church attendance is associated with receiving more informal spiritual support (β = .419; p < .001). This is important because, as reported above, spiritual support is, in turn, associated with a benevolent image of God (β = .362; p < .001). Taken together, these relationships indicate that church attendance influences God images indirectly through informal spiritual support. One of the advantages of working with latent variable models arises from the fact that indirect effects can be estimated directly. Moreover, when the direct effect of church attendance on God images is combined with the indirect effect that operates through spiritual support, the resulting total effect provides a more comprehensive view of the relationship between church attendance and images of God. Breaking down this relationship into direct, indirect, and total effects is known as the decomposition of effects (Little 2013).

The decomposition involving the relationship between church attendance and God images indicates that the indirect effect that operates through spiritual support is statistically significant (β = .153; p < .001). When this indirect effect is added to the direct effect of church attendance on God images that is reported in Table 3 (β = .077; p < .001), the resulting total effect of church attendance is substantially larger (β = .229; p < .001; not shown in Table 3). Viewed in a more general way, this decomposition of effects suggests that rather than viewing the effects of church attendance and spiritual support on God images independently, it makes more sense to think about how these facets of congregational life jointly influence whether church members view God as benevolent.

Two additional decomposition of effects help bring the role that spiritual support plays in the study model into sharper focus. The first involves the relationship between spiritual support and hope. The data in Table 3 indicate that people who receive more spiritual support from fellow church members tend to be more hopeful about the future (β = .131; p < .001). However, when the indirect effects of spiritual support that operate through God images and feelings of gratitude to God are taken into account (β = 139; p < .001; not shown in Table 3), the resulting total effect (β = .270; p < .001; not shown in Table 3) is significantly larger. Viewed in another way, these data suggest that 51.5 % of the total effect of spiritual support on hope operates indirectly through God images and feelings of gratitude to God (.139/.270 = .515).

The final decomposition involves the relationship between spiritual support and symptoms of physical illness. The data in Table 3 are challenging because they suggest that greater spiritual support is associated with more symptoms of physical illness (β = .119; p < .001). This is not consistent with the findings from other studies on spiritual support and health (Krause 2008). Decomposing the relationship between spiritual support and illness symptoms makes it possible to reflect more deeply on the nature of this relationship. The indirect effects of spiritual support on physical illness symptoms that operate through the study model are statistically significant (β = −.050; p < .001; not shown in Table 3). This indirect effect is more in line with what other studies reveal. Even so, when the direct and indirect effects are summed, the total effect still suggest that greater spiritual support is associated with more symptoms of physical illness, but the magnitude of this relationship is more modest (β = .069; p < .001; not shown in Table 3). Taken as a whole, this decomposition of effects suggests that spiritual support may enhance and compromise health. This complex pattern of findings is important because it shows how latent variable modeling can challenge an investigator’s theoretical abilities by uncovering unanticipated findings that require deeper insight and more elaborate explanation.

Discussion

Two broad insights emerge from this study. First, the findings suggest that the foundational views that people have of God (i.e., their images of God) may have important health consequences. Moreover, these potential health benefits may be traced to the feelings of gratitude and hope that these internal working models of God promote. Second, the images that people have of God arise, in part, from the interplay between attendance at worship services and interaction with fellow church members. Taken together, these two blocks of findings suggest that the social life of the church shapes the images that people have of God and these images, in turn, serve to strengthen their relationship with God (via gratitude), influence their view of the future (via hope), and ultimately, bolster their health.

Although the findings from this study provide support for the core hypotheses that were proposed earlier, an unanticipated result emerged from the data. The findings indicate that more spiritual support is associated with more symptoms of physical illness. This is not consistent with a vast literature which reveals that more social support is associated with better health (Roy 2011). Unfortunately, it is not possible to pursue this issue empirically because the additional data that are needed to do so are not available. It is possible, however, to speculate on the factors that may be at work. McFadden et al. (2003) studied friendships that arise in church and in the process, they examined spiritual support. These investigators argue that spiritual support is likely to be beneficial if it is provided by a close friend, but they go on to note that, “… some people might be offended if they are offered spiritual support from people they do not consider to be friends” (McFadden et al. 2003, p. 43). Evidence of the health-related effects of this view is found in the wider literature on secular social support. This research suggests that unwanted assistance may have a noxious effect on health and well-being (e.g., Newsom et al. 2008). Perhaps some of the participants in the current study were offended by the spiritual support they were offered at church. Moreover, the negative interaction that was created by these overtures may have culminated in symptoms of physical illness.

Although the findings from this study provide some insight into the role that God images play in religious life, a considerable amount of research remains to be done. Some of the linkages in the study model were, in part, bridged by conjecture. For example, it was proposed that gratitude to God fosters a greater sense of hope because people who are grateful can cope more effectively with stressful life events. However, stress and coping was not evaluated in this study. Doing so in future research will provide a more direct test of the theoretical foundation of the model that was developed in the current study. In addition, all of the relationships in the study model are linear and additive. However, research is needed to see whether there are statistical interaction effects between some of the components of religion. For example, spiritual support from fellow church members may bolster feelings of gratitude, but only among study participants who have a benevolent view of God.

As in any social science endeavor, there are limitations in the work that was presented above. It is especially important to highlight one shortcoming. The data for this study were gathered at a single point in time and as a result, the causal ordering among the constructs in the study model was based on theoretical considerations alone. As a result, other researchers may legitimately propose different causal orderings. There are at least three ways of relationships that can be re-specified in this way. First, people who have more benevolent views of God may subsequently attend worship services more often and they may be more receptive to the spiritual support that is offered by fellow church members. Second, individuals who are more hopeful about the future may be more grateful to God. Third, people who enjoy better health may be more hopeful about the future, as well. Clearly these issues, as well as the other causal assumptions that are embedded in the study model, must be evaluated rigorously with data that have been gathered at more than one point in time.

Josiah Royce was a close friend of William James and, at times, one of his staunchest critics. Whereas James traced the genesis of religion to factors deep within the human psyche, Royce instead emphasized its social roots: “… the principal means of grace, I say, which is open to any man lies in such communion with the faithful and with the unity of spirit which they express in their lives. It is natural that we should begin this process of communion through direct personal relationships with fellow-servants of our own special cause” (Royce 1912/2001, p. 291). Maintaining a strong faith is hard work because people are required to believe in things they cannot see and trust in forces that cannot be empirically verified. Under such conditions of uncertainty, it is not surprising to find that people turn to like-minded others for insight and encouragement. The findings from the current study illustrate one way in which the social aspect of religious life may be manifest. Hopefully, this will encourage similar efforts.

References

Barna, G. (2006). The state of the church: 2006. Ventura, CA: The Barna Group.

Berger, P. L. (1967). The sacred canopy: Elements of a sociological theory. New York: Doubleday.

Braam, A. W., Jonker, H. S., Mooi, B., De Ritter, D., Beekman, A. T., & Deeg, D. J. (2008). God image and mood in old age: Results from a community-based pilot study in the Netherlands. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11, 221–237.

Bradshaw, M., Ellison, C. G., & Flannelly, K. J. (2008). Prayer, God imagery, and symptoms of psychopathology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47, 644–659.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18, 293–299.

Cohen, S., & Rodriguez, M. S. (1995). Pathways linking affective disturbances and physical disorders. Health Psychology, 14, 374–380.

DeShon, R. P. (1998). A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods, 3, 412–423.

du Toit, M., & du Toit, S. (2001). Interactive LISREL: User’s guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An empirical Investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389.

Exline, J. J., Grubbs, J. B., & Homolka, S. J. (2015). Seeing God as cruel and distant: Links with divine struggles involving anger, doubt, and fear of God’s disapproval. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 25, 29–41.

Feldman, D. B., & Sills, J. R. (2013). Hope and cardiovascular health-promoting behavior: Education alone is not enough. Psychology and Health, 28, 727–745.

Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute.

Gall, T. L., Kristjansson, E., Charbonneau, C., & Florack, P. (2009). A longitudinal study of the role of spirituality in response to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 174–186.

Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2009). Positive expectations and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 548–556.

Hoy, B. D., Suldo, S. M., & Mendez, L. R. (2013). Links between parents’ and children’s levels of gratitude, life satisfaction, and hope. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1343–1361.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut points for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149.

Idler, E. L., Hudson, S. V., & Leventhal, H. (1999). The meanings of self-rated health. Research on Aging, 21, 458–476.

Ironson, G., Stuetzle, R., Ironson, D., Balbin, E., Kremer, H., George, A., et al. (2011). View of God as benevolent and forgiving or punishing and judgmental predicts HIV disease progression. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34, 414–425.

Jiang, F., Yue, X., Lu, S., Yu, G., & Zhu, F. (2015). How belief in a just world benefits mental health: The effects of optimism and gratitude. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0877-x.

Johnson, K. A., Li, Y. J., Cohen, A. B., & Okun, M. A. (2013). Friends in high places: The influence of authoritarian and benevolent God-concepts on social attitude and behaviors. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5, 15–22.

Khosravi, Z., Pasdar, Z., & Farahani, Z. K. (2011). Investigation of positive and negative conception of God and its relation with pathological and non-pathological guilt feeling. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1378–1380.

Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2005). Attachment, evolution, and the psychology of religion. New York: Guilford.

Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Krause, N. (2002). A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 57B, S263–S274.

Krause, N. (2008). Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

Krause, N., & Ellison, C. G. (2009). The social environment of the church and feelings of gratitude toward God. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3, 191–205.

Krause, N., Evans, L. A., Powers, G., & Hayward, R. D. (2012). Feeling grateful to God: A qualitative inquiry. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 119–130.

Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2014). Religious involvement, practical wisdom, and self-rated health. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16, 629–640.

Lashani, Z., Shaeiri, M. R., Moghadam, M. A., & Galzari, M. (2012). Effect of gratitude strategies on positive affectivity, happiness, and happiness. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 18, 164–166.

Lazar, A. (2014). The relation between God concept and prayer style among male religious Israeli Jews. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. doi:10.1080/10508619.2014.935685.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford.

Lundberg, C. D. (2010). Unifying truths of the world’s religions. New Fairfield, CT: Heavenlight Press.

Magaziner, J., Bassett, S. S., Hebel, J. R., & Cruber-Baldini, A. (1996). Use of proxies to measure health and functional status in epidemiologic studies of community dwelling women age 65 years and older. American Journal of Epidemiology, 143, 283–290.

Maynard, E. A., Gorsuch, R. L., & Bjorck, J. P. (2001). Religious coping style, concept of God, and personal religious variables in threat, loss, and challenge situations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40, 65–74.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., Kirkpatrick, S., Emmons, R. A., & Larsen, D. (2001). Gratitude as a moral affect. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249–266.

McFadden, S. H., Knepple, A. M., & Armstrong, J. A. (2003). Length and locus of friendship influence, church members’ sense of social support, and comfort with sharing emotions. Journal of Religious Gerontology, 15, 39–55.

Newsom, J. T., Mahan, T. L., Rook, K. S., & Krause, N. (2008). Stable negative social exchanges and health. Health Psychology, 27, 78–86.

Ouellette, J. A., & Wood, W. (1998). Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 54–74.

Rasmussen, H. N., Scheier, M. F., & Greenhouse, J. B. (2009). Optimism and physical health: A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 239–256.

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Cohen, A. B., Galler, Y., & Krumrei, E. J. (2011). Grateful to God or just plain grateful? A comparison of religious and general gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 389–396.

Roy, R. (2011). Social support, health, and illness: A complicated relationship. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Royce, J. (1912/2001). The sources of religious insight. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

Scioli, A., Chamberlin, C. M., Samor, C. M., Lapointe, A. B., Campbell, T. L., Macleod, A. R., & McLenon, J. (1997). A prospective study of hope, optimism, and health. Psychological Reports, 81, 723–733.

Settersten, R. A., & Trauten, M. E. (2009). The new terrain of old age: Hallmarks, freedoms, and risks. In V. L. Bengston, D. Gans, N. M. Putney, & M. Silverstein (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (2nd ed., pp. 455–470). New York: Springer.

Simmel, G. (1964). The sociology of Georg Simmel (K. Wolff, editor and translator). New York: Simon & Schuster.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249–275.

Stark, R. (2008). What Americans believe. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

Stark, R., & Finke, R. (2000). Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Steenwyk, S. A., Atkins, D. C., Bedics, J. D., & Whitley, B. E. (2010). Images of God as they relate to life satisfaction and hopelessness. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 20, 85–96.

Watkins, P. C. (2014). Gratitude and the good life: Toward a psychology of appreciation. New York: Springer.

Widaman, K. F. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 361–389). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Wong-McDonald, A., & Gorsuch, R. L. (2004). A multivariate theory of God concept, religious motivation, locus of control, coping, and spiritual well-being. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 32, 318–334.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Grant from the John Tempelton Foundation (Grant 40077).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krause, N., Emmons, R.A. & Ironson, G. Benevolent Images of God, Gratitude, and Physical Health Status. J Relig Health 54, 1503–1519 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0063-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0063-0