Abstract

Objectives

Examine whether a death-in-police-custody incident affected community reliance on the police, as measured through citizen calls requesting police assistance for non-criminal caretaking matters.

Methods

This study used Baltimore Police Department (BPD) incident-level call data (2014–2017) concerning non-criminal caretaking matters (N = 234,781). Counts of non-criminal caretaking calls were aggregated by week for each of 279 unique sections derived from census-tract and police district boundaries. This study devised a Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score that operationalized the expected risk of a negative community–police relationship for each of the sections. In April 2015, a Baltimore resident, Freddie Gray, died while in BPD custody. A Poisson regression model assessed whether this high-profile death-in-police-custody incident adversely affected the volume of non-criminal caretaking calls to the police and whether that effect was strongest in sections at a high risk of a negative community–police relationship. A falsification test used pocket-dialed emergency calls to verify that any observed trends were not the result of overall telephone usage.

Results

There was no statistical evidence that the death-in-police-custody incident produced any changes in community reliance on the police for non-criminal caretaking matters, even in high-risk sections. A supplemental analysis using calls for criminal matters yielded similar results. As the falsification test demonstrated, the observed trends were not the result of overall telephone usage.

Conclusions

Despite a divisive death-in-police-custody incident, citizens were still willing to enlist police assistance. More broadly, the caretaking role of the police may be an important mechanism to strengthen community–police relations, particularly in marginalized neighborhoods vulnerable to strained community–police relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study assesses whether a highly-publicized death-in-police-custody incident affected community willingness to request police aid, with calls for non-criminal caretaking services as the primary outcome measure. In April 2015, a Baltimore resident, Freddie Gray, died in Baltimore Police Department custody, prompting two weeks of civil unrest and directing national scrutiny towards Baltimore policing practices. If calls in Baltimore for non-criminal caretaking matters subsequently decreased, then it would indicate that the incident prompted a loss of public willingness to seek police assistance. If no change or an increase in the frequency of these calls occurred, then it would indicate that the public, despite the strained community–police relationship, were still willing to enlist police assistance.

An individual’s race, age, socio-economic status, neighborhood, prior police interactions, and awareness of negative police-citizen encounters can influence his or her attitudes towards the police (MacDonald et al. 2007; Carr et al. 2007; Weitzer and Tuch 2005; Jefferis et al. 1997). A divisive high-profile event, such as a high-profile death-in-police-custody incident, may create a sudden adverse shift in community attitudes (Kaminski and Jefferis 1998; Weitzer 2002); but see (White et al. 2018). And, a divisive high-profile event may also affect willingness to rely on the police (Desmond et al. 2016, 2020); but see (Zoorob 2020). The inherently “pre-and-post” nature of divisive high-profile events creates a temporal delineation that can provide a valuable way for researchers to isolate the effect of police conduct on community willingness to rely on the police.

Previous studies have found that highly publicized negative police-citizen interactions may decrease community willingness to report criminal activity to the police (Desmond et al. 2016, 2020); but see (Zoorob 2020). It is possible, however, that any changes in a willingness to report criminal activity to the police—in response to highly publicized negative police-citizen interactions—may also be the product of other factors, such as crime increases or shifts in how law enforcement reacts to crime. In short, when community reporting of criminal activity to the police is the outcome measure, it may be difficult to disentangle the relationships among police behavior, community attitudes and actions, and other factors that are endogenously related to a community’s willingness to rely on the police for assistance.

By contrast, community reliance on the police for non-criminal caretaking services may provide a measure of community willingness to seek police assistance that is more independent of these endogenous factors. These non-criminal caretaking services include, for example, aiding disabled vehicles or providing assistance during behavioral health crises.

Also, through its use of calls to the police for non-criminal caretaking matters, this study implicitly addresses a function of the police that is distinct from law enforcement. This non-criminal caretaking aspect of policing has remained underexplored in existing empirical research. As some researchers have hypothesized, the non-criminal caretaking role of police may strengthen police-community relationships and, more generally, create positive community perceptions of the police (Furstenberg and Wellford 1973). Given current challenges concerning police legitimacy in many communities, empirical assessments of the non-criminal caretaking functions of the police may be especially relevant.

Although American policing has historically entailed a non-criminal caretaking dimension (President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice 1967), this dimension continues to evolve. Police functions that transcend a traditional law enforcement role present important consequences not only for social order but for public health as well (Wood et al. 2015; Greenberg and Frattaroli 2018).

Consistent with previous research, this study proposes a quantitative measure of the risk of a negative community–police relationship for a given geographic area of a city. The analysis then assesses whether, after Gray’s death, calls for non-criminal caretaking matters decreased more in higher risk areas than in lower risk areas of Baltimore.

In 2020, during a deadly global pandemic and severe economic and social hardships, America witnessed several tragic high-profile incidents in which its citizens died during police interactions. Thus, more than six years after Gray’s death, the problems of strained police–community relations, police use of excessive force, and racial disparities in policing persist. The analysis and methodology in this study seek to contribute to existing empirical research addressing these problems.

Background

On April 12, 2015, Baltimore Police Department (BPD) officers arrested Freddie Gray, a twenty-five-year-old Black male, for allegedly possessing a switchblade (U.S. Department of Justice 2017; Kerrison et al. 2018; White et al. 2018). Six police officers from the Western District, one of Baltimore’s nine police districts, were involved in Gray’s arrest. By the end of an approximately 40-minute ride in a police van, Gray was unconscious, suffering from severe spinal cord injuries; he remained hospitalized until his death on April 19. Meanwhile, on April 18, Baltimore residents began protesting the conduct of the BPD (Cox et al. 2015; Hurdle and Slotnik 2015). By April 25, however, the peaceful protests had devolved into property destruction, violence, and looting (Wen et al. 2015; Rector et al. 2015). The protests and riots in Baltimore had largely subsided towards the end of the first week of May (Stolberg 2015; Morgan and Pally 2016). On May 1, the Baltimore State’s Attorney Office charged all six officers with offenses that included homicide (U.S. Department of Justice 2017). Yet, by the summer of 2016, these charges had resulted in acquittals or dismissals.

In response to the events of spring 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice conducted an investigation of the BPD. Issuing a report in August 2016, DOJ determined that the BPD had engaged in a pattern of unconstitutional conduct (City of Baltimore 2018; U.S. Department of Justice 2016). Thus, the BPD underwent some remediation efforts in 2016 and 2017. For example, in April 2017, the City of Baltimore and DOJ entered into a consent decree, requiring that the BPD had to work on reforms such as building community trust. The DOJ investigation also revealed that BPD officers responding to behavioral health crises had not received proper training, often creating situations involving unnecessary and disproportionate physical force against individuals with behavioral health challenges (U.S. Department of Justice 2016).

Given the well-established relationship between demographic factors and attitudes towards the police, it is possible that the effects of a high-profile death-in-police-custody incident on community reliance on the police may have been differentially present in certain areas of Baltimore. The demographic heterogeneity of Baltimore that emerged during the twentieth century still exists (Taylor 2001; White et al. 2018); at both the census-tract and police district levels, Baltimore markedly varies in terms of characteristics such as racial composition and poverty levels. The Baltimore Police Department Monitoring Team, formed pursuant to the consent decree, produced a July 2019 report; according to qualitative research about police officers’ perceptions, the state of community–police relations varied by geographic area of the city (Crime and Justice Institute 2019). As some researchers have noted, given a history of aggressive policing in disadvantaged Baltimore neighborhoods, the “setting was rife for cynicism….” (Kerrison et al. 2018).

Prior Literature

The non-criminal community caretaking function of the police has not received the same level of empirical scrutiny that the law enforcement function of the police has attracted. Additionally, two well-established and related areas of previous research are particularly relevant to determining whether high-profile negative police-citizen interactions affect the willingness of citizens to seek police assistance: (1) factors that influence citizens’ decision to contact the police and (2) factors that influence citizens’ attitudes towards the police.

Police Caretaking Function

As researchers hypothesized as early as the 1970’s, public confidence in the police could potentially increase “if the police began to measure, and thus make more visible” their non-criminal caretaking role that “account[s], to a great extent, for the positive aspects of the police image.” (Furstenberg and Wellford 1973, pp. 394). At the same time, however, the public may develop a negative perception of the police if officers fail to effectively fulfill their non-law enforcement role (Johnson et al. 1981).

The police role in a community inherently involves activities that are distinct from enforcing the law and combatting crime (Hudson 2013; Schafer 2001; Paoline 2001; Call 1998; Livingston 1998; President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice 1967). Contemporary policing requires that officers respond to both emergency and non-emergency problems that are service-related rather than crime-related (Chriss 2011; Pepinsky 1989; Johnson et al. 1981; Wood et al. 2015; Alpert et al. 2015).

Police responsibilities often include checking on the welfare of elderly residents, assisting stranded motorists (Dimino 2009), rescuing animals from dangerous highways (Johnson et al. 1981); providing referrals to social service agencies (Alpert et al. 2015), warning residents about a leak of hazardous materials; or reuniting unattended children with their parents (Decker 1999). In many communities, including Baltimore, the police are the primary resource for immediate responses to emergency behavioral health situations; for example, the family member of a person experiencing an emergency behavioral health situation may call 911, requesting that the police help escort the person to a hospital for an evaluation (U.S. Department of Justice 2016; Lamb et al. 2002; Wood and Watson 2017).

Police in many jurisdictions are now also responsible for administering opioid reversal drugs to individuals suffering from an overdose (Davis et al. 2014); other urban areas have policies that allow the police to transport gunshot or stabbing injury victims to the hospital (Band et al. 2014; Jacoby et al. 2020).

In short, police departments are frequently the sole government agency available to address citizens’ requests for help or information, regardless of the time of day or day of the week (Laimin and Teboh 2016; Schafer 2001; Alpert et al. 2015). Through their community caretaking role, the police ensure the safety and welfare of the community (Decker 1999; Wood et al. 2015). As some scholars have noted, “service-style policing and community relations go hand in hand” (Alpert 2015, pp. 180). Community-oriented policing conceptualizes the police function broadly, defining it to include social service and general assistance functions; consequently, the non-criminal caretaking role is an important dimension of community-oriented policing.

Willingness to Seek Police Assistance

Contacting the police provides an indication of civil engagement and collective efficacy (Sampson 2017; Taylor et al. 2009; Brantingham and Uchida 2021). A lack of reliance on the police, even for non-criminal caretaking matters, may suggest disruptions in the social contract between a government and its citizens. Additionally, in democratic societies, citizen requests for police assistance are, to a certain extent, statements about how the public perceives the police—and how the public defines the police function (Bennett 2004; Berg and Rogers 2017; Black 1973). To that extent, the decision to report a crime to the police is the product of individual-level, incident-level, and community-level factors (Schnebly 2008).

As a general matter, urban residents and individuals of low socio-economic status may be especially likely to call the police when they have been crime victims (Avakame et al. 1999; Baumer 2002). It is possible that low socio-economic status crime victims rely on the police because they lack alternatives that may be available to wealthier people such as private security or family members who can intervene. As prior research has found, in urban areas, increased calls for service are associated with symptoms of decreased informal resident control over a location (Kurtz et al. 1998). A recent study using Los Angeles data found that calls-for service reporting violent crime and quality-of-life issues (e.g., loud parties) increase significantly in the week following a homicide (Brantingham and Uchida 2021).

At the same time, reporting crime to authorities or cooperating with criminal investigations may be broadly disfavored in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods (Brunson and Wade 2019). This norm largely reflects a distrust of the criminal justice system as a whole rather than a specific distrust of the police (Anderson, 1994; Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2015; Slocum et al. 2010). In a qualitative study, street-level offenders reported that they would never call the police under any circumstances (Rosenfeld et al. 2003). Others acknowledged that they would call the police only for very limited situations such as immediate danger to a family member or for a heinous offense such as murder.

In deciding whether to report crimes to the police, victims may rationally weigh the costs and benefits attendant to reporting, such as the likelihood that an offense will be “solvable” (Skogan, 1976) or the harm to them or the offenders (Felson et al. 2002). As a further consideration, a survey-based study in Chicago found that on average, citizens are more likely to report serious violent crimes, such as shootings, that occurred at greater distances from their residences relative to similarly distanced but less serious violent crimes, such as fights (Wisnieski et al. 2013).

Some researchers have explored how high-profile negative events involving the police affect the willingness of citizens to seek police assistance. Desmond et al. (2016) examined whether the 2004 police beating of an unarmed Black male in Milwaukee that received media coverage affected community willingness to call the police for criminal matters. As the study found, although calls had been increasing before the beating story, subsequent to reports of the beating, calls decreased significantly in both Black and white neighborhoods. Within a year, these effects eventually diminished in white neighborhoods, but not in Black neighborhoods. The study also assessed whether citizen crime reporting in Milwaukee decreased in response to three other publicized controversies about police behavior against unarmed Black males, two of which occurred outside Milwaukee; the three incidents happened between 2006 and 2009. In two of the three cases, the study found an association between the incidents and a short-term relative drop in crimes reported to the police. Other research suggests that the effects in Desmond et al. were the product of an outlier—and that no changes in citizen call behavior occurred (Zoorob 2020).

Using Los Angeles data, another study explored whether officer-involved shootings that resulted in a civilian death had any effect on emergency 911 and nonemergency 311 calls to municipal government (Cohen et al. 2019). Comparing the frequency of calls during the 30-day period before a shooting with the frequency of calls during the 30-day period after the shooting, the study found that these shootings did not alter citizen’s reliance on municipal government for assistance. Using New York City 311 service calls to municipal government as a measure of community engagement, other research has found that the concentration of police stops generally was associated with increased community engagement (Lerman and Weaver 2014). Yet, stops that did not involve arrests but that involved searches or use of force, reduced community engagement.

Factors Affecting Citizen Attitudes Towards Police

The police require public support to maintain legitimacy and efficacy (Kochel et al. 2013; Tyler 2004); concomitantly, how the police exercise their authority is associated with whether the public views the police as procedurally just governmental actors (Tyler and Wakslak 2004). The concept of procedural justice hypothesizes that citizens will have less satisfaction with the police where they perceive that the police, as governmental authorities, fail to act in a just and fair manner (Haberman et al. 2016). In turn, when criminal justice actors act in a trustworthy and neutral manner and treat citizens with respect, citizens will perceive that they have been treated fairly. Citizens will perceive criminal justice system agents as legitimate, thus promoting compliance with the law (Nagin and Telep 2017; Weisburd and Majmundar 2018; Tyler 2017; White et al. 2018).

Empirical research has found that citizen perceptions of procedurally just treatment are closely tied to perceptions of police legitimacy, and that perceptions of legitimacy are largely associated with legal compliance (Nagin and Telep 2017). More specifically, dissatisfaction with the police is associated with public perceptions that, for example, the police engage in racially-biased conduct (Weitzer and Tuch 2002), use excessive force (Jefferis et al. 1997), fail to prevent crime and neighborhood disorder (Taylor et al. 2015), or are untrustworthy (MacDonald and Stokes 2006) or illegitimate government actors (Tankebe 2013). Nonetheless, empirical research has not yet established a causal association between procedurally just treatment and perceived legitimacy and compliance (Nagin and Telep 2017).

A variety of demographic and environmental factors can influence a citizen’s attitudes towards the police (Brown and Benedict 2002; Taylor and Lawton 2012; Reisig and Parks 2000; Shjarback et al. 2018). These factors include age, race, socio-economic status, neighborhood conditions, and prior experiences with law enforcement (Weitzer 2002, 1999; Schuck et al. 2008; Taylor et al. 2015; Tyler 2005; Ridgeway and MacDonald 2014).Footnote 1

Young residents of high-crime neighborhoods often report adverse views of the police based on prior negative interactions and aggressive policing, despite a desire for more police-community engagement (Carr et al. 2007; Brunson 2007; Brunson and Miller 2006; Kerrison et al. 2018; Haberman et al. 2016). Yet, research has found that hot spots policing activity that can reduce crime does not have any significant effect on community perceptions of crime and disorder, perceived safety, satisfaction with the police, or procedural justice (Ratcliffe et al. 2015).

Also, compared to white citizens, non-white citizens may hold less favorable perceptions of the police (Kaminski and Jefferis 1998; Weitzer and Tuch 2004). Compared to white urban residents, Black urban residents are more likely to perceive that police misconduct is a problem in their neighborhoods (Weitzer et al. 2008). Black–white differences in perceptions of the police also hold even when neighborhood context is taken into account (MacDonald et al. 2007).

Knowledge about another person’s encounter with the police can also influence an individual’s perception of the police (Rosenbaum et al. 2005). To that extent, mass media reports on police abuse may increase the likelihood that citizens will have negative perceptions of the police (Weitzer and Tuch 2004, 2005; Jefferis et al. 1997; Chermak et al. 2006; Lasley 1994).

Given this vicarious influence on citizen attitudes, some research has explored whether highly publicized episodes of police violence or misconduct affects public perceptions of the police. At least one survey-based study has indicated that these events may have little immediate effect on public views of police legitimacy and procedural justice. White et al. (2018) surveyed Baltimore residents that were at least twenty one years old; because residents were surveyed both before and after Gray’s death, researchers were able to examine how Gray’s death impacted residents’ perceptions of the police. The survey revealed little change in residents’ attitudes of police legitimacy and procedural justice, regardless of residents’ race or residency in a crime hot-spot area. Yet, among whites, there was a significant decrease in perceived obligation to obey the law. As a theoretical matter, the findings contradicted the procedural justice theory assumption that how police officers behave and treat citizens can have immediate, or at least short-term, impacts on perceptions of police legitimacy.

Nonetheless, other research has reached the opposite conclusion. As one study using poll data found, the Los Angeles Police Department Rampart Division scandal and two New York Police Department fatal-use-of-force incidents adversely affected public attitudes, with the largest effects occurring among African–Americans (Weitzer 2002). Likewise, a 1998 study, which used survey data from Cincinnati residents over an 11‐year period, examined whether the violent televised arrest of an African–American affected public opinions of the police (Kaminski and Jefferis 1998). Despite substantial differences among minorities and whites in their existing levels of police support, the televised arrest largely had no effect on racial differences, with Blacks having less favorable views across the entire time span. Similarly, another study used a panel survey of St. Louis, Missouri residents conducted before and after the police shooting of Michael Brown to evaluate the effects of the shooting on procedural justice, police legitimacy, and willingness to cooperate with police. African–American views significantly declined while other residents’ perceptions remained stable (Kochel 2019).

Motivations for Current Study

In contrast to previous research, this study uses citizen calls for police assistance with non-criminal caretaking matters as a measure of community reliance on the police. Within a large city such as Baltimore, citizen calls to the police for criminal matters may be endogenously related to crime increases, de-policing behaviors,Footnote 2 and pre-existing norms (Crime and Justice Institute 2019).

More precisely, an increase in citizen calls reporting criminal activity may simply reflect an increase in criminal activity—rather than greater citizen reliance on the police. Also, consistent with de-policing, it is possible that an increase in citizen calls concerning crime did not result from a greater community reliance on the police or an increase in crime. Instead, under this de-policing theory, when police withdraw from proactive policing, it is likely to produce a decrease in officer- initiated calls and an increase in citizen calls for service.

As an additional matter, some communities in urban areas may broadly view the government role in the criminal justice system with distrust. These communities may therefore be less likely to report crime to authorities or cooperate with criminal investigations. The distrust inherent in this norm encompasses all governmental actors in the criminal justice system, including, but not limited to, the police (Anderson 1994; Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2015; Slocum et al. 2010). A reliance on the police for non-criminal matters is disassociated from the effects of this norm. Consistent with prior research (Rosenfeld et al. 2003), concern about an elderly neighbor or a disabled vehicle may transcend generalized distrust of governmental authority.

To that extent, this analysis uses caretaking calls as a means to assess community reliance on the police independent of factors such as de-policing, overall crime trends, and norms about reliance on governmental authority within the criminal justice system context. As an ancillary matter, the non-criminal caretaking function of policing has remained underexplored in existing criminological research. Given the importance of community-oriented policing strategies in twenty-first century policing (Mastrofski and Willis 2010), empirical assessments of the non-criminal caretaking functions of the police may be especially valuable. Community-oriented policing encourages officers to collaboratively work with residents to identify and solve problems (Reisig 2010; Parks et al. 1999). Although community policing may not necessarily reduce crime (MacDonald 2002), it may improve citizen perceptions of police legitimacy (Gill et al. 2014; Peyton et al. 2019). The service dimension of policing is strongly associated with community relations (Alpert et al. 2015). As has long been hypothesized, the non-criminal caretaking role of the police may engender positive public perceptions of the police (Furstenberg and Wellford 1973). Thus, the non-criminal caretaking role is an important dimension of community-oriented policing (Alpert et al. 2015).

As a final consideration, this study uses data as to incidents that have already occurred—calls for service—to measure actual citizen behavior. In contrast to survey-based research, this study does not use individuals’ predictions about what their future behavior might be in a given situation. As other researchers have noted (Desmond et al. 2016; Kochel et al. 2013; Skogan 1984), it may be more useful to measure individual behavior based on actual past behavior. More broadly, calls for service are an important and efficient means of information exchange between the public and the police (MacDonald et al. 2003)—and therefore constitute a useful indicator of the public–police relationship.

Data and Methods

This study uses the following data and methods to assess whether a high-profile death-in-police-custody incident affected community reliance on the police and whether any hypothesized decrease in reliance was strongest in areas at greatest risk of a negative relationship with the police.

Call Data

This study uses incident-level Baltimore Police Department 911 call data that range in date from January 1, 2014 through December 31, 2017. In 2015, the BPD began online posting of this data as part of a transparency effort (Rentz 2015). Baltimore residents, after the events of April 2015, had expressed concern about the long wait times for many 911 calls. The data contain information such as a brief reason for the call, the census tract and police district from which the call originated, the call date, and the call priority (Baltimore Police Department 2020).

For its main analysis, this study uses non-criminal caretaking matters to test whether the events around Gray’s death impacted citizen reliance on the police.Footnote 3 These matters include the following call categories: “Adult Wellbeing Check,” “Individual Locked Out of/In Vehicle or Home,”Footnote 4 “Homeless,” “Accident,” “Behavioral Health,” “Disabled or Abandoned Vehicle,” “Person Walking on a Highway,” and “Lost or Stranded Adult.”Footnote 5 These are non-criminal caretaking matters in which a citizen-caller has discretion to (1) call the police or, alternatively, (2) engage in some form of self-help. For example, where an individual is locked outside of a car, instead of calling the police, the caller could break a window or contact a friend or family member for assistance.

Any vehicle accident calls that included a death or injury are excluded from the non-criminal caretaking categorization. The majority of included accident calls would likely include requests for police assistance with the peaceful transfer of insurance information or documenting property damage for insurance claim purposes.Footnote 6 Calls that likely originated from an institution, such as a medical facility, are excluded. Also, all calls where a caller would likely primarily expect a medical (e.g., ambulance), fire department, or municipal service (e.g., maintenance crew) response rather than a police response are excluded.

Importantly, community reliance on the police in a given geographic location may be a function of the demographic characteristics of that location. Baltimore is comprised of 200 census tracts and nine (9) police districts (City of Baltimore 2010). Of the 200 census tracts, approximately 59% have borders that are completely within only one police district, whereas the remainder have borders that extend into two or more districts.

Approximately 99% of the non-criminal caretaking call incidents had both an identifiable census tract and an identifiable police district. The boundaries of these census tracts and the police districts form 279 unique sections where non-criminal call incidents occurred. To illustrate, where a census tract extended into three police districts, the census tract was divided into three unique sections. These sections are the spatial unit of analysis for this study. The use of both census tract and police district boundaries captures both tract-level demographic characteristics as well as district-specific policing characteristics. Each section has, on average, approximately 2229 residents.

All told, this study uses N = 234,781 calls to the police that report non-criminal caretaking matters in Baltimore between 2014 and 2017. Seventy-two percent of these calls involved an accident (N = 169,394), 4% involved a disabled or abandoned vehicle (N = 8364), 12% involved a behavioral health matter (N = 28,700), 11% involved a wellbeing check (N = 26,313), and the remainder of calls involved lock-ins or lock-outs involving an individual (N = 1190), a homeless person (N = 249), an adult stranded or lost (N = 524), or a person walking along a highway (N = 47).

As an additional matter, pocket-dialed calls (N = 724,730) provide a useful proxy for overall phone usage. These “Pocket-Dialed” calls include those call incidents in the data were described with phrases such as “911/No Voice” or “911/Hangup.” Also, for comparative purposes, this study assesses whether any effects occurred as to citizen calls to the police that report criminal matters (N = 1,316,774). The criminal matters include reports of arson, armed individuals, assault, burglary, robbery, theft, property destruction, unauthorized use of motor vehicles, prostitution, threatening or harassing behavior, trespassing, shooting/firearm discharge, suspicious persons/loitering, and weapons.

Temporal Periods

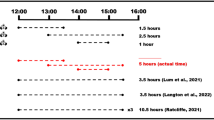

Figure 1 is a time series plot showing the average weekly amount of calls for assistance with non-criminal caretaking, criminal, and pocket-dialed matters at the section level over the 212-week period between 2014 and 2017. The vertical lines mark the two-weeks of civil unrest stemming from Gray’s death.

Notably, during the first week of the resulting civil unrest (Week 70), there is an approximately 34% increase in calls reporting criminal matters, relative to the preceding week (Week 69). Both a slight overall increase in calls to the police for assistance for non-criminal caretaking matters and a slight overall increase in calls reporting criminal activity appear to occur over the 212 weeks; also, an overall decrease in pocket-dialed calls is apparent.

For this study, all of 2014 and the first sixteen weeks of 2015 (before Gray’s death and the resulting civil unrest) are the Pre-Period. The two weeks between April 19, 2015 and May 2, 2015 (Weeks 70 and 71) that had rioting, protests, or some form of civil unrest are the Unrest-Period. The next sixteen (16) weeks (Weeks 72 through 87) are the Immediate-Post-Period (May 3, 2015–August 22, 2015). The remaining weeks of 2015, all of 2016, and all of 2017 are the Post-Period.

It is reasonable to hypothesize that, relative to the Pre-Period, negative public sentiment towards the police increased during the Unrest-Period. Yet, the infrastructural chaos attendant to the civil unrest that followed Gray’s death may have also prompted greater dependence on the police, particularly for non-criminal caretaking matters. To that extent, the time period most of interest for this study is the Immediate-Post-Period, the aftermath of the civil unrest. During this period, despite the restoration of social order, negative public sentiment towards the police likely existed. The period after the Immediate-Post-Period, the Post-Period, provides a measure of long-term effects.

Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score

Besides temporal considerations relative to Gray’s death and the resulting civil unrest, geographic or demographic factors within Baltimore also may affect community reliance on the police. As prior research has explained (Weitzer 2002, 1999; Weitzer and Tuch 2004; Schuck et al. 2008; Taylor et al. 2015; Tyler 2005), perceptions of the police may be adversely affected by demographic characteristics. These characteristics may include the percentage of the population that is Black or that is young (e.g., aged 12–25 years). Relevant neighborhood-level factors include the percentage of vacant housing unitsFootnote 7 or the percentage of the population that is unemployed or lives in poverty.

When considered collectively, these demographic characteristics can create a measure of the risk of a negative community–police relationship. Each of the unique 279 geographic sections in this study were linked to demographic data from the 2016 Five-Year American Community Survey; the data addressed the following demographic indicators: (1) percentage of the population that is Black; (2) percentage of the population aged 12–25; (3) percentage of the population that lives in poverty; (4) percentage of the population that is unemployed; and (5) percentage of residential housing units that are vacant (U.S. Census Bureau 2016).Footnote 8 These demographic indicators were selected because, as prior literature instructs, Black citizens, young citizens, and residents of disadvantaged urban neighborhoods are more likely to have negative perceptions of the police—relative to the rest of the population; additionally, where aggressive policing occurs in an urban area, these populations are often the most likely to encounter it (Carr et al. 2007; Brunson 2007; Brunson and Miller 2006; Kaminski and Jefferis 1998; Weitzer et al. 2008).

A composite measure of the predicted risk of a negative community–police relationship for each section was calculated; the method for calculating this measure borrows from the approach that neighborhood disadvantage literature has used to calculate a concentrated disadvantage composite index, e.g., (Boardman et al. 2001; Sampson and Bartusch 1998; Clear et al. 2003; Morenoff et al. 2001).Footnote 9

For each section, the five individual demographic indicators were standardized by subtracting the city-wide mean and dividing by the city-wide standard deviation. For each of the 279 sections, the five standardized scores (one for each demographic indicator) were summed to create an overall index of a predicted negative community–police relationship. The mean of the resulting Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score is 0.00, and the standard deviation is 3.43. The index ranges from − 8.63 to 10.32; namely, the section at the most risk of a negative community–police relationship scored the highest, 10.32, on the index, and the section that was at the least risk scored the lowest, − 8.63, on the index. In short, this Index Score operationalizes the risk of a negative community–police relationship in a given section.

For both Table 1 and Fig. 2, the sections were divided into six categories according to how many standard deviations from the mean that a section scored on the Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score. Table 1 demonstrates the variation in the average number of non-criminal caretaking calls per section per week given both the temporal period and the Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score.

Within a given category, the change in the average number of caretaking calls per section per week relative to the average number of caretaking calls per section per week in the Pre-Period for that category is noted with parentheses; significance levels were calculated through a t-test. For example, in the “Extremely Low Risk” sections, the average number of calls per section per week in the Post-Period (4.33) was compared to the average number of calls per section per week in the Pre-Period (2.48). The Pre-Period functions as a baseline about call behavior for each of the six categories of risk. Also, within the Pre-Period column, the average number of calls per section per week for a given category in the Pre-Period is compared to the average number of calls per section per week regardless of category (3.48). This difference is noted with brackets; significance levels were again calculated with a t test. Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of the section-level Index Scores.

Regression Analysis

Nonetheless, these descriptive numbers do not control for finer geographic or temporal trends. The following Poisson regression model was used to estimate whether Gray’s death and the ensuing anti-police sentiment had any effect on the willingness of Baltimore residents to call the police for assistance with non-criminal caretaking matters:

The main outcome of interest in this study is the weekly number of non-criminal caretaking calls in each of the 279 unique sections, indexed by i. The outcome, \({\lambda }_{it}\), represents the expected weekly call count for non-criminal caretaking matters in section i for week t. When exponentiated, the coefficients \({\beta }_{1}\), \({\beta }_{2},\) and \({\beta }_{3}\) indicate the multiplicative change in number of calls per week per section attributable to having occurred during the Unrest-Period, Immediate-Post-Period, or the Post-Period, relative to the Pre-Period. \({Unrest}_{t}\), \({Immediate Post}_{t}\), and \({Post}_{t}\) are 0/1 indicators of in which period week t occurs. \({\beta }_{4}t+{\beta }_{5}{t}^{2}\) captures any linear or quadratic trend in crime over the study period. \({\gamma }_{Season(t)}\) is a fixed effect for season.

The variable \({Score}_{i}\), the Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score for a given section, operationalizes predicted negative relationships between the police and the public. This model includes interaction terms where each Index Score for a section is interacted with each of the discrete temporal categories. These interaction terms model the change in the number of calls based on the index score during each of the discrete temporal categories. It is reasonable to expect that any effects on community reliance on the police in response to Gray’s death in a section may be dependent on the predicted community-police negative relationship in that section, as measured by the Index Score.

Significance levels are calculated through permutation tests. Standard significance tests produced by the regression model alone inherently rely on distributional assumptions such as the absence of spatial and temporal correlation (Ridgeway and MacDonald 2017). With many quasi-experimental designs, these assumptions may be incorrect. For example, the Immediate-Post-Period in this study occurred during the spring and summer of 2015. Any effects observed during this period may be correlated with seasonal conditions—rather than with the temporal proximity (within 16 weeks) of this period to Gray’s death and the attendant civil unrest.

Permutation tests provide a non-parametric alternative that generates a reference distribution for the parameters of interest (Ludbrook 1994) and have been applied in other criminological research (MacDonald et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2007; Ridgeway and MacDonald 2017). The null hypothesis in this study is that the number of calls per week in a given section is independent of the interaction between the Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score, \({Score}_{i},\) and the temporal “nearness” to the events of April 2015.

Thus, to generate a reference distribution for the statistics of interest, the permutation test altered the start of the Unrest-Period, while maintaining the temporal pattern of the original data. This pattern consists of more than one week of a Pre-Period, two weeks of an Unrest-Period, sixteen weeks of an Immediate-Post-Period, and more than 1 week of a Post-Period. Using all 212 weeks, a total of 193 permutations was possible. For example, Week 120 is the Post-Period in the original data. In one of the permutations, it is assigned as the first week of the “Unrest-Period,” Week 121 is assigned as the second week of the “Unrest-Period,” all weeks before Week 120 are assigned as the “Pre-Period,” the sixteen weeks after Week 121 are assigned as the “Immediate Post-Period,” (Weeks 122–137), and all weeks after Week 137 as the “Post-Period.”

The Poisson regression for each permutation of the labels was recomputed. This process simulated what the distribution of the treatment effects would look like under the null hypothesis that the number of calls is independent of temporal proximity to the Unrest-Period. The estimated p value is the fraction of the results from the permuted data that is as or more extreme than the coefficient derived from the regression model using the original data.

Additionally, given that vehicle accidents constitute 72% of the caretaking calls, the analysis is re-run with vehicle accidents excluded as a test of the robustness of the results. Furthermore, it is possible that any observed effects are the result of overall phone usage. Therefore, as a falsification test, this analysis reran the above model using pocket-dialed emergency calls, which provide a proxy for overall phone usage. As an additional comparative matter, this analysis reran the model using calls for criminal matters instead of non-criminal caretaking matters.

Results

The Freddie Gray death-in-police-custody incident largely did not produce any effect on community reliance on the police, as measured through calls for non-criminal caretaking matters. The temporal periods, Unrest-Period, Immediate-Post-Period, and Post-Period did not experience any significant change in the number of non-criminal caretaking calls relative to the Pre-Period. When the temporal periods are interacted with the Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score, a significant increase in the number of non-criminal caretaking calls occurred only during the Unrest-Period relative to the Pre-Period. Table 2 presents these results.

Sections with high Index Scores generated a greater increase in non-criminal caretaking calls during the Unrest-Period relative to the Pre-Period when compared with areas with lower Index Scores. During the Unrest-Period, each unit increase in the Index Score was associated with a significant 1.7% increase in calls. Otherwise, there was no significant effect on the multiplicative change in calls in a temporal period, relative to the Pre-Period, when interacted with the Index Score.Footnote 10

The falsification test replaced non-criminal caretaking calls with pocket-dialed calls to assess whether any observed effects may simply be the result of overall phone usage. However, this falsification test largely yielded non-significant results. As an additional matter, this analysis substituted calls for police assistance with non-criminal caretaking matters with calls for police assistance with criminal matters. When the Index Score is interacted with temporal periods, there are no significant effects.

Discussion

Using Baltimore data, this study assessed whether a high-profile death-in-police-custody incident affected community reliance on the police. Drawing intense national scrutiny and provoking two weeks of civil unrest, the death of Freddie Gray created a temporal delineation where it would be reasonable to expect a pronounced shift in citizens’ attitudes toward the police—and their reliance on the police based on these attitudes. This reliance was measured through calls to the police for assistance with non-criminal caretaking matters. Overall, it appears that Gray’s death and the resulting unrest exerted little effect on community reliance on the police.

As a preliminary matter, these results do not necessarily provide evidence about citizen attitudes. Instead, the results in this study provide insight only as to citizen willingness to enlist police assistance. Yet, to the extent that citizen behavior is somehow a manifestation of citizen attitudes, the results comport with research assessing citizen attitudes in response to Gray’s death. White et al. (2018) surveyed Baltimore residents that were at least twenty one years old both before and after Gray’s death; the survey revealed little change in residents’ perceptions of police legitimacy and procedural justice.

Prior literature has suggested that distrust of the police may render citizens less willing to seek police assistance (Bennett 2004; Baumer 2002; Desmond et al. 2016). Thus, willingness to seek police assistance provides, albeit indirectly, some measure of public trust in the police. Yet, Gray’s death, an extreme manifestation of strained community–police relations, largely did not have any significant effect on the willingness of the public to rely on the police.

It is also possible, however, that although Gray’s death may have increased community distrust of the police throughout Baltimore, citizens disengaged this distrust from their behavior. Thus, if they needed assistance during the two weeks of civil unrest or the period immediately after this civil unrest, Baltimore residents would still contact the police—even if they did so reluctantly. To that extent, the findings in this study are somewhat reassuring in that they suggest that citizens did not engage in complete “de-citizening”; specifically, the social contract (Kochel et al. 2013; Tyler 2004) between the government and the citizens was not completely broken because citizens continued to exercise their rights to appropriate police assistance.

This study had several limitations. For example, this study used one divisive high-profile incident in a single urban area to empirically assess whether a death-in-police-custody incident that provoked intense public outrage affected community reliance on the police. Future research should replicate this study in other large cities that experience divisive high-profile police-citizen incidents to see whether they impact communities’ reliance on the police for assistance.

Additionally, it is possible that any negative police-citizen incidents that had preceded Gray’s death had already brought the call rate to a very low level so that by April 2015, the call rate could not have decreased any more than it had. Nonetheless, this study used sections throughout Baltimore that exhibited heterogeneity in the weekly number of calls per section during the Pre-Period, which was approximately sixteen months.

Furthermore, in urban areas, it is reasonable to expect that individuals, as part of their daily activity patterns, often travel outside of the neighborhoods in which they reside (Basta et al. 2010; Hurvitz et al. 2014; Wiebe, et al. 2016). To that extent, a call from a particular section in this study might not necessarily originate from an individual who resides in that section; instead, the call might originate from a non-resident who, as a result of his or her daily activity pattern, happens to temporarily be in that section for some transitory purpose such as work or recreation. Yet, within a given section, it is likely that the proportion of calls from non-residents remained constant during the temporal periods of interest (e.g., the Immediate-Post-Period relative to the Pre-Period).Footnote 11

Several considerations may explain the results of this study. Certainly, if any incident in Baltimore in recent years were to precipitate intense distrust of the police and reduce Baltimore citizens’ willingness to rely on the police, Gray’s death would have been the most likely to have done so. Yet, even in sections most likely to have experienced heightened distrust of the police, there was no significant decrease during either the Immediate-Post-Period or the Post-Period in calls to the police for assistance with non-criminal caretaking matters.

During the Unrest-Period, relative to the Pre-Period, there was a significant 1.7% increase in calls for non-criminal caretaking matters for each unit increase in the Negative Community–Police Relationship Index Score. It is possible that the infrastructural chaos of the Unrest-Period may have prompted greater dependence on the police, particularly for non-criminal caretaking matters. For example, during the civil unrest, these calls possibly increased because individuals living in sections with a high Index Score could not safely leave their homes to assist with a neighbor’s lock-out or to check on an at-risk elderly community member.

More broadly, the caretaking role of the police may be an important mechanism through which the police can develop stronger community–police relations, particularly in marginalized neighborhoods susceptible to feelings of distrust between the police and the public. If the public perceives that the police are willing to assist them with issues such as a behavioral health crisis or an individual locked out of a vehicle, then the public may develop more favorable perceptions of the police (Furstenberg and Wellford 1973). Additionally, in democratic societies, citizen requests for police assistance are statements about what the public believes that the police function should be (Bennett 2004; Berg and Rogers 2017; Black 1973). Future research should empirically assess whether positive interactions between the community and the police for non-criminal caretaking matters can, in fact, improve community perceptions of the police.Footnote 12 Future research should also assess citizen perceptions of the non-criminal caretaking role of the police.

Importantly, in Baltimore, the caretaking role of the BPD, prior to Gray’s death and the DOJ investigation, had suffered from the same problems that had plagued the law enforcement role of the BPD. For example, the DOJ investigation had revealed that the BPD had a history of using unnecessary and disproportionate force during behavioral health crises. Most callers in sections that were at risk for strained police–community relations were likely well aware that any interaction with the police—even if the interaction began as a request for assistance with an elderly neighbor or a family member in a behavioral health crisis—had the volatile potential to escalate into a negative, if not violent, situation. To that extent, calls to the police for assistance with non-criminal caretaking matters provide a useful measure of public willingness to engage the police.

In the near future, the non-law enforcement function of the police may become increasingly important—not only in the context of community-oriented policing—but also for public health and welfare (Galva et al. 2005). In communities with a large population of at-risk residents, such as the elderly or those with behavioral health or substance abuse problems, positive relationships between the police and the community may enable the police to better serve community needs. Incidentally, as prior researchers have noted, many Baltimore neighborhoods, including the neighborhood in which Gray had lived, experience overall poor health outcomes (Wen et al. 2015). Future research should consider ways to quantitatively assess police performance in the non-criminal caretaking context—in much the same way that police performance in the law enforcement context is assessed through measures such as arrest and clearance rates.

As this study finds, the events of April 2015 appeared to have had no significant effect on the willingness of Baltimore residents to seek police assistance, as measured through community reliance on the police for non-criminal caretaking matters. Nonetheless, the fact remains that the events of April 2015 constituted a harsh culmination of issues that have troubled Baltimore—and the rest of America—for decades. And these issues did not resolve themselves in the aftermath of Freddie Gray’s death. In 2020, America began its struggle with a deadly pandemic that has claimed millions of lives worldwide and imposed severe social and economic hardships. That same year, the American people once again had to confront troubling issues surrounding police–community relations—and the intersection of these issues with race. Future empirical research should continue to evaluate and seek ways to improve relationships between police and communities, including within the context of the non-criminal caretaking police function.

Notes

Also, a citizen is more likely to be satisfied with a police encounter where the police are perceived as fair, polite, and communicative (Skogan 2005). As a recent randomized controlled trial found, positive police-citizen interactions in the form of brief door-to-door non-law enforcement visits significantly improved citizens’ attitudes towards the police (Peyton et al. 2019).

According to some observers, the BPD, post-2015, may have engaged in de-policing (Rector 2017; Oppel 2015; Morgan and Pally 2016; Heath 2018; U.S. Department of Justice 2016). Police officers generally learn about criminal activity either through their own observations or through citizen reports to them (Black 1973).

The total data from the BPD website contained over 9000 distinct call reasons that could be separated into categories that also included, for example: “Death,” “Custody/Visitation,” “Elopement/Medical Facility Problems,” “Noise/Animal or Vehicle Disturbance,” and “Dangerous Driving/Road Rage.”

This category excludes calls about a child or pet locked in a vehicle given that these calls may involve a citizen reporting potential criminal activity such as neglect.

This category excludes lost or missing children, runaways, or adults reported as “missing.”

According to 2016 Maryland Department of Transportation data, 77.3% of motor vehicle accidents in Baltimore involved only property damage; 22.7% percent involved an injury, and less than 1% involved a fatality (Maryland State Police 2017). Compared to other accidents, in these property-damage-only accidents, motorists likely have more discretion as to whether they contact the police. As an additional matter, prior research about motor vehicle accidents in Baltimore City has found that no association between socioeconomic variables of accident locations and accident incident density (Dezman et al. 2016).

For two of the 279 sections, some demographic indicators were missing. Census data from 2010 was therefore used (City of Baltimore 2010).

As a preliminary matter, a factor analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which these five demographic indicators are highly correlated with each other, thereby loading on the same factor (Sampson et al. 1997). A factor analysis sets out to determine the relationship among observed, correlated variables with the recognition that at least some of these variables together may constitute a single (or, at a minimum, a smaller number of) latent or unobserved factors (Maruyama and Ryan 2014).

The resulting correlation coefficients among the five indicators were (Black = 0.76, Poverty = 0.72, Vacant Residential Housing Units = 0.63, Unemployed = 0.87, and Aged 12–25 = 0.08). The Aged 12–25 indicator is not strongly correlated with the other indicators. Nonetheless, it is retained in calculating the risk index score; even if the remaining four indicators are more strongly correlated with each other (and, in the aggregate, constitute a factor), it is possible that age is still relevant to the risk of a negative relationship with the police. As a robustness check, however, an alternate index score was computed, and the full analysis was re-run with the age indicator omitted from the index score.

A factor analysis showed that the Aged 12–25 indicator was not strongly correlated with the other indicators. Nonetheless, it was retained in calculating the risk index score. As a robustness check, an alternate index score was computed, and the full analysis was re-run with the age indicator omitted from the index score. The significance levels do not change.

Similarly, this analysis uses a relatively small geographic unit for which demographic characteristics are available. To that extent, the analysis minimizes the possibility of an ecological fallacy—namely that it uses area-level characteristics to draw conclusions about individual-level behavior (Ackerman and Rossmo, 2015). Nonetheless, individual-level data may be particularly valuable to future research assessing public willingness to rely on the police and the community caretaking role.

Certainly, controversies surrounding police behavior, especially within the context of race, have troubled American society throughout much of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The 1967 President’s Crime Commission report noted difficulties with police-community relations, particularly in marginalized urban neighborhoods (President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice 1967). Nonetheless, social media and the increasing presence of social-media supportive technology (e.g., smartphones with improved video-recording capabilities) have facilitated an instantaneous dissemination of ideas, visual images, and emotions in a way traditional media, including online news sources, had been inherently incapable of doing (Gallagher et al. 2018; Ince et al. 2017; Bock 2016; Brown 2015). To that extent, understanding citizen judgments about police conduct has become especially relevant.

References

Ackerman J, Rossmo D (2015) How far to travel? A multilevel analysis of the residence-to-crime distance. J Quant Criminol 31:237–262

Alpert G, Dunham R, Stroshine M (2015) Policing: continuity and change, 2nd edn. Waveland Press, Long Grove

Anderson E (1994) The code of the streets. The Atlantic 273:80–94

Avakame E, Fyfe J, McCoy C (1999) Did you call the police? What did they do?: an empirical assessment of Black’s theory of mobilization of law. Justice Q 16:765–792

Baltimore Police Department (2020) 911 Police calls for service. Retrieved from https://data.baltimorecity.gov/Public-Safety/BPD-Officer-Involved-Use-Of-Force/3w4d-kckv.

Band R, Salhi R, Holena D, Powell E, Branas C, Carr B (2014) Severity-adjusted mortality in trauma patients transported by police. Ann Emerg Med 63:608–614

Basta L, Richmond T, Wiebe D (2010) Neighborhoods, daily activities, and measuring health risks experienced in urban environments. Soc Sci Med 71:1943–1950

Baumer E (2002) Neighborhood disadvantage and police notification by victims of violence. Criminology 40:579–616

Bennett R (2004) Calling for service: mobilization of the police across sociocultural environments. Police Pract Res 5:25–41

Berg M, Rogers E (2017) The mobilization of criminal law. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci 13:451–469

Black D (1973) The mobilization of law. J Legal Stud 2:125–149

Boardman J, Finch B, Ellison C, Williams D, Jackson J (2001) Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 42:151–165

Bock M (2016) Film the police! cop-watching and its embodied narratives. J Commun 66:13–34

Brantingham P, Uchida C (2021) Public cooperation and the police: do calls-for-service increase after homicides?. J Crim Justice 73:101785

Brown G (2015) The blue line on thin ice: police use of force modifications in the era of cameraphones and Youtube. Br J Criminol 56:293–312

Brown B, Benedict W (2002) Perceptions of the police: past findings, methodological issues, conceptual issues and policy implications. Polic Int J Police Strateg Manag 25:543–580

Brunson R (2007) “Police don’t like Black people”: African–American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminol Public Policy 6:71–101

Brunson R, Miller J (2006) Young Black men and urban policing in the United States. Br J Criminol 46:613–640

Brunson R, Wade B (2019) “Oh hell no, we don’t talk to police”: insights on the lack of cooperation in police investigations of urban gun violence. Criminol Public Policy 18:623–648

Call J (1998) Defining the community caretaking function. Polic Int J Police Strat Manag 21:269–279

Carr P, Napolitano L, Keating J (2007) We never call the cops and here is why: a qualitative examination of legal cynicism in three Philadelphia neighborhoods. Criminology 45:445–480

Chermak S, McGarrell E, Gruenewald J (2006) Media coverage of police misconduct and attitudes toward police. Polic Int J Police Strat Manag 29:261–281

Chriss J (2011) Beyond community policing: from early american beginnings to the 21st century. Paradigm Publishers, Boulder

City of Baltimore (2018) Retrieved from City of Baltimore Consent Decree. https://consentdecree.baltimorecity.gov/

City of Baltimore (2010) 2010 Census tracts—shape. Retrieved from https://data.baltimorecity.gov/Neighborhoods/2010-Census-Tracts-Shape/5hwf-e4yi

Clampet-Lundquist S, Carr P, Kefalas M (2015) The sliding scale of snitching: a qualitative examination of snitching in three Philadelphia communities. Sociol Forum 30:265–285

Clear T, Rose D, Waring E, Scully K (2003) Coercive mobility and crime: a preliminary examination of concentrated incarceration and social disorganization. Justice Q 20:33–64

Cohen E, Gunderson A, Jackson K, Zachary P, Clark T, Glynn A, Owens M (2019) Do officer-involved shootings reduce citizen contact with government? J Polit 81:1111–1123

Cox J, Alexander K, Halsey A (2015) In Baltimore, peaceful protest shifts focus back to death of Freddie Gray. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/curfew-lifts-after-calmer-night-in-baltimore-but-tensions-remain/2015/04/29/3f2d42f2-ee7f-11e4-8666-a1d756d0218e_story.html

Crime and Justice Institute (2019) Feedback from the field: a summary of focus groups with Baltimore Police Officers: Prepared by The Crime and Justice Institute for the Baltimore Police Department Monitoring Team

Davis C, Ruiz S, Glynn P, Picariello G, Walley A (2014) Expanded access to naloxone among firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical technicians in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health 104:e7–e9

Decker J (1999) Emergency circumstances, police responses, and Fourth Amendment restrictions. J Crim Law Criminol 89:433–534

Desmond M, Papachristos A, Kirk D (2016) Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the Black community. Am Sociol Rev 81:857–876

Desmond M, Papachristos A, Kirk D (2020) Evidence of the effect of police violence on citizen crime reporting. Am Sociol Rev 85:184–190

Dezman Z, de Andrade L, Vissoci J, El-Gabri D, Johnson A, Hirshon J, Staton C (2016) Hotspots and causes of motor vehicle crashes in Baltimore, Maryland: a geospatial analysis of five years of police crash and census data. Injury 47:2450–2458

Dimino M (2009) Police paternalism: community caretaking, assistance searches, and Fourth Amendment reasonableness. Washington & Lee Law Review 66:1485–1563

Felson R, Messner S, Hoskin A, Deane G (2002) Reasons for reporting and not reporting domestic violence to the police. Criminology 40:617–648

Furstenberg F, Wellford C (1973) Calling the police: the evaluation of police service. Law Soc Rev 7:393–406

Gallagher R, Reagan A, Danforth C, Dodds P (2018) Divergent discourse between protests and counter-protests: #BlackLivesMatter and #AllLivesMatter. PLoS ONE 13:1–23

Galva J, Atchison C, Levey S (2005) Public health strategy and the police powers of the state. Public Health Rep 120:20–27

Gill C, Weisburd D, Telep C, Vitter Z, Bennett T (2014) Community-oriented policing to reduce crime, disorder and fear and increase satisfaction and legitimacy among citizens: a systematic review. J Exp Criminol 10:399–428

Greenberg S, Frattaroli S (2018) What police officers want public health professionals to know. Inj Prev 24:178–179

Haberman C, Groff E, Ratcliffe J, Sorg E (2016) Satisfaction with police in violent crime hot spots: using community surveys as a guide for selecting hot spots policing tactics. Crime Delinq 62:525–557

Heath B (2018) Baltimore police stopped noticing crime after Freddie Gray's death. A wave of killings followed. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/07/12/baltimore-police-not-noticing-crime-after-freddie-gray-wave-killings-followed/744741002/

Hudson D (2013) Courts in a muddle over 4th Amendment’s community caretaking exception. ABA J. Retrieved from https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/courts_in_a_muddle_over_4th_amendments_community_caretaking_exception

Hurdle J, Slotnik D (2015) Clashes in Philadelphia as Freddie Gray protest neared highway. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/01/us/clashes-in-philadelphia-as-freddie-gray-protest-neared-highway.html

Hurvitz P, Moudon A, Kang B, Fesinmeyer M, Saelens B (2014) How far from home? The locations of physical activity in an urban U.S. setting. Prev Med 69:181–186

Ince J, Rojas F, Davis C (2017) The social media response to Black Lives Matter: how Twitter users interact with Black Lives Matter through hashtag use. Ethnic Racial Stud 40:1814–1830

Jacoby S, Reeping P, Branas C (2020) Police-to-hospital transport for violently injured individuals: a way to save lives? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 687:186–201

Jefferis E, Kaminski R, Holmes S, Hanley D (1997) The effect of a videotaped arrest on public perceptions of police use of force. J Crim Justice 25:381–395

Johnson T, Misner G, Brown L (1981) The police and society: an environment for collaboration and confrontation. Prentice-Hall Inc, Englewood Cliffs

Johnson S, Bernasco W, Bowers K, Elffers H, Ratcliffe J, Rengert G, Townsley M (2007) Space-time patterns of risk: a cross national assessment of residential burglary victimization. J Quant Criminol 23:201–219

Kaminski R, Jefferis E (1998) The effect of a violent televised arrest on public perceptions of the police: a partial test of Easton’s theoretical framework. Polic Int J Police Strat Manag 21:683–706

Kerrison E, Cobbina J, Bender K (2018) “Your pants won’t save you”: why Black youth challenge race-based police surveillance and the demands of Black respectability politics. Race Justice 8:7–26

Kochel T (2019) Explaining racial differences in Ferguson’s impact on local residents’ Trust and perceived legtimacy: policy implications for police. Crim Justice Policy Rev 30:374–405

Kochel T, Parks R, Mastrofski S (2013) Examining police effectiveness as a precursor to legitimacy and cooperation with police. Justice Q 30:895–925

Kondo M, Keene D, Hohl B, MacDonald J, Branas C (2015) A difference-in-differences study of the effects of a new abandoned building remediation strategy on safety. PLoS ONE 10:1–14

Kurtz E, Koons B, Taylor R (1998) Land use, physical deterioration, resident-based control, and calls for service on urban streetblocks. Justice Q 15:121–149

Laimin S, Teboh C (2016) Police social work and community policing. Cogent Soc Sci 2:1–13

Lamb H, Weinberger L, DeCuir W (2002) The police and mental health. Psychiatr Serv 53:1266–1271

Lasley J (1994) The impact of the Rodney King incident on citizen attitudes toward police. Polic Soc 3:245–255

Lerman A, Weaver V (2014) Staying out of sight? Concentrated policing and local political action. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 651:202–219

Livingston D (1998) Police, community caretaking, and the Fourth Amendment. University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp 261–314

Ludbrook J (1994) Advantages of permutation (randomization) tests in clinical and experimental pharmacology and physiology. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 21:673–686

MacDonald J (2002) The effectiveness of community policing in reducing urban violence. Crime Delinq 48:592–618

MacDonald J, Stokes R (2006) Race, social capital and trust in the police. Urban Aff Rev 41:358–375

MacDonald J, Manz P, Alpert G, Dunham R (2003) Police use of force: examining the relationship between calls for service and the balance of police force and suspect resistance. J Crim Justice 31:119–127

MacDonald J, Stokes R, Ridgeway G, Riley K (2007) Race, neighbourhood context and perceptions of injustice by the police in Cincinnati. Urban Stud 44:2567–2585

MacDonald J, Fagan J, Geller A (2016) The effects of local police surges on crime and arrests in New York City. PLoS ONE 11:1–13

Maruyama G, Ryan C (2014) Research methods in social relations. Wiley Blackwell, West Sussex

Maryland State Police (2017) Maryland Statewide Vehicle Crashes. Retrieved from https://catalog.data.gov/dataset?tags=maryland-state-police

Mastrofski S, Willis J (2010) Police organization continuity and cange: into the twenty-first century. Crime and Justice 39:55–144

Morenoff J, Sampson R, Raudenbush S (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 39:517–560

Morgan S, Pally J (2016) Ferguson, Gray, and Davis: an analysis of recorded crime incidents and arrests in Baltimore City, March 2010 through December 2015. Report (21st Century Cities Initiative, Johns Hopkins University). Retrieved from https://socweb.soc.jhu.edu/faculty/morgan/papers/MorganPally2016.pdf

Nagin D, Telep C (2017) Procedural justice and legal compliance. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci 13:5–28

Oppel R (2015) West Baltimore’s police presence drops, and murders soar. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/13/us/after-freddie-gray-death-west-baltimores-police-presence-drops-and-murders-soar.html

Paoline E (2001) Rethinking police culture: officers’ occupational attitudes. LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC, New York

Parks R, Mastrofski S, DeJong C, Gray M (1999) How officers spend their time with the community. Justice Q 16:483–518

Pepinsky H (1989) Issues of citizen involvement in policing. Crime Delinq 35:458–470

Peyton K, Sierra-Arevalo M, Rand D (2019) A field experiment on community policing and police legitimacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116:19894–19898

President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice (1967) The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society.

Ratcliffe J, Groff E, Sorg E, Haberman C (2015) Citizens’ reactions to hot spots policing: impacts on perceptions of crime, disorder, safety and police. J Exp Criminol 11:393–417

Rector K (2017) In Baltimore, police face pressure to halt violence and heated scrutiny of arrests. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/crime/bs-md-ci-policing-in-flux-20170814-story.html

Rector K, Dance S, Broadwater L (2015) Riots erupt: Baltimore descends into chaos, violence, looting. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/crime/bs-md-ci-police-student-violence-20150427-story.html

Reisig M (2010) Community and problem-oriented policing. Crime Justice 39:1–53

Reisig M, Parks R (2000) Experience, quality of life, and neighborhood context: a hierarchical analysis of satisfaction with police. Justice Q 17:607–630

Rentz C (2015). Baltimore police now posting 911 calls online. The Baltimore Sun

Ridgeway G, MacDonald J (2014) A method for internal benchmarking of criminal justice system performance. Crime Delinq 60:145–162

Ridgeway G, MacDonald J (2017) Effect of rail transit on crime: a study of Los Angeles from 1988 to 2014. J Quant Criminol 33:277–291

Rosenbaum D, Schuck A, Costello S, Hawkins D, Ring M (2005) Attitudes toward the police: the effects of direct and vicarious experience. Police Q 8:343–365

Rosenfeld R, Jacobs B, Wright R (2003) Snitching and the code of the street. Br J Criminol 43:291–309

Sampson R (2017) Urban sustainability in an age of enduring inequalities: advancing theory and ecometrics for the 21st-century city. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114:8957–8962

Sampson R, Bartusch D (1998) Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: the neighborhood context of racial differences. Law Soc Rev 32:777–804

Sampson R, Raudenbush S, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Schafer J (2001) Community policing: the challenges of successful organizational change. LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC, New York

Schnebly S (2008) The influence of community-oriented policing on crime-reporting behavior. Justice Q 25:223–251

Schuck A, Rosenbaum D, Hawkins D (2008) The influence of race/ethnicity, social class, and neighborhood context on residents’ attitudes toward the police. Police Q 11:496–519

Shjarback J, Nix J, Wolfe S (2018) The ecological structuring of police officers’ perceptions of citizen cooperation. Crime Delinq 64:1143–1170

Skogan W (1976) Citizen reporting of crime-some national panel data. Criminology 13:535–549

Skogan W (1984) Reporting crimes to the police: the status of world research. J Res Crime Delinq 21:113–137

Skogan W (2005) Citizen satisfaction with police encounters. Police Q 8:298–321

Slocum L, Taylor T, Brick B, Esbensen F (2010) Neighborhood structural characteristics, individual-level attitudes and youths’ crime reporting intentions. Criminology 48:1063–1100

Stolberg S (2015) Baltimore enlists National Guard and a curfew to fight riots and looting. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/28/us/baltimore-freddie-gray.html

Tankebe J (2013) Viewing things differently: the dimensions of public perceptions of police legitimacy. Criminology 51:103–135

Taylor R (2001) Breaking away from broken windows: Baltimore neighborhoods and the nationwide fight against crime, grime, fear, and decline. Westview Press, Boulder

Taylor R, Lawton B (2012) An integrated contextual model of confidence in local police. Police Q 15:414–445

Taylor T, Holleran D, Topalli V (2009) Racial bias in case processing: does victim race affect police clearance of violent crime incidents? Justice Q 26:562–591

Taylor R, Wyant B, Lockwood B (2015) Variable links within perceived police legitimacy? Fairness and effectiveness across races and places. Soc Sci Res 49:234–248

Tyler T (2004) Enhancing police legitimacy. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 593:84–99

Tyler T (2005) Policing in black and white:ethnic group differences in trust and confidence in the police. Police Q 8:322–342

Tyler T (2017) Procedural justice and policing: a rush to judgment? Ann Rev Law Soc Sci 13:29–53

Tyler T, Wakslak C (2004) Profiling and police legitimacy: procedural justice, attributions of motive, and acceptance of police authority. Criminology 42:253–281

U.S. Department of Justice (2016) Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-findings-investigation-baltimore-police-department

U.S. Department of Justice (2017) Federal Officials Decline Prosecution in the Death of Freddie Gray. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/federal-officials-decline-prosecution-death-freddie-gray

U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2012–2016 (2016). https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2016/

Weisburd D, Majmundar M (2018) Proactive policing: effects on crime and communities. The National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC

Weitzer R (1999) Citizens’ perceptions of police misconduct: race and neighborhood context. Justice Q 16:819–846

Weitzer R (2002) Incidents of police misconduct and public opinion. J Crim Justice 30:397–408

Weitzer R, Tuch S (2002) Perceptions of racial profiling: race, class, and personal experience. Criminology 40:435–456

Weitzer R, Tuch S (2004) Race and perceptions of police misconduct. Soc Probl 51:305–325

Weitzer R, Tuch S (2005) Racially biased policing: determinants of citizen perceptions. Soc Forces 83:1009–1030

Weitzer R, Tuch S, Skogan W (2008) Police-community relations in a majority-Black city. J Res Crime Delinq 45:398–428

Wen L, Warren K, Tay S, Khaldun J, O’Neill D, Farrow O (2015) Public health in the unrest: Baltimore’s preparedness and response after Freddie Gray’s death. Am J Public Health 105:1957–1959

White C, Weisburd D, Wire S (2018) Examining the impact of the Freddie Gray unrest on perceptions of the police. Criminol Public Policy 17:829–858