Abstract

Unhealthy alcohol use is a significant public health concern among ethnic minority immigrant gay, bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in North America. The definition of unhealthy alcohol use is any use that increases the risk of health consequences or has already led to negative health consequences. Despite its association with various health problems, this issue remains understudied in this population. Therefore, we aim to synthesize key findings to provide the prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use and related factors among this population in North America. We conducted a comprehensive literature search in multiple scientific databases to identify studies on alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. Using random-effect modeling strategies, we aggregate and weigh the individual estimates, providing a pooled prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use within this population. Our review included 20 articles with 2971 participants (i.e., 53% were Latino, 45% were Asian/Pacific Islanders, and 2% were African). The meta-analysis revealed that 64% (95% CI 0.50, 0.78) of the participants reported recent alcohol use, while 44% (95% CI 0.30, 0.59) engaged in unhealthy alcohol use. Co-occurring health issues identified in the studies are other substance use (32%; 95% CI 0.21, 0.45), positive HIV status (39%; 95% CI 0.14, 0.67), and mental health issues (39%; 95% CI 0.21, 0.58). We also identified several factors associated with unhealthy alcohol use, including risky sexual behaviors, experiences of discrimination based on race and sexual orientation, and experiences of abuse. However, meta-regression results revealed no statistically significant associations between alcohol use and co-occurring health problems. This is the first study to systematically review unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. Despite the high burden of alcohol use, there is a dearth of research among Asian and African GBMSM. Our findings underscore the need for more research in these groups and provide insights to inform targeted clinical prevention and early intervention strategies to mitigate the adverse consequences of unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of alcohol use disorder has significantly increased in North America over the past 10 years and is higher among the gay, bisexual, and men who have sex with men (GBMSM) population [1, 2]. A national survey on substance abuse in the United States shows that gay and bisexual adults are more likely to engage in unhealthy alcohol use than other groups [3, 4]. This issue is especially pronounced in ethnic minority communities, where gay and bisexual men report higher rates of heavy episodic drinking compared to their heterosexual counterparts [4]. Numerous studies have shown positive associations between unhealthy alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors, in addition to other significant health risks. These findings indicate that alcohol use increases HIV risk behaviors in this population, including condomless anal intercourse and multiple sex partners [5, 6]. Despite the high prevalence and negative consequences of alcohol use in sexual minorities, the mechanisms explaining the high level of alcohol use among GBMSM populations have not been clearly determined [7].

Unhealthy alcohol use is a significant public health concern, particularly among “ethnic minority” and “immigrant” GBMSM populations who face multiple layers of marginalization due to their intersecting identities that include ethnic minority, immigrant, and sexual minority [8, 9]. While epidemiologic studies have documented that foreign-born ethnic minority populations generally exhibit lower rates of unhealthy alcohol use than North America-born populations, variations by ethnic origin do exist. Moreover, significant alcohol-related health disparities persist across ethnic and sexual minority populations in North America [10,11,12]. Specifically, ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM experience a greater impact from drinking and suffer more severe alcohol-related consequences compared to their white counterparts [5, 13, 14]. These disparities can be attributed to factors such as a lack of appropriate services, social norms, drinking culture, attitudes about treatment, perceived need, and poor access to treatment services [15]. A finding from the National Alcohol Survey explains that racial and ethnic disparities in alcohol use stem from social disadvantages, including poverty, discrimination, and stigma [16]. Consequently, moderate heavy drinkers who are Black have 4.72 times the odds of exhibiting symptoms of alcohol dependence compared to their white counterparts [17]. Black and Hispanic moderate heavy drinkers have 1.47 times the odds of encountering social issues related to alcohol use in comparison to white moderate heavy drinkers [17]. Despite these documented disparities, there has been a dearth of research specifically investigating unhealthy alcohol use within the ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM community. As such, it is imperative to address the unique challenges faced by this population, who represent one of the most marginalized and underserved groups in our society.

Epidemiologic prevalence findings often focus on alcohol use disorder (AUD) but seldom address problematic alcohol use that falls outside this category, especially among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines binge drinking as consuming 5 or more drinks on an occasion for men and 4 or more for women, while the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) sets it as a drinking pattern that raises blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08% or higher [18, 19]. Consequently, the term “unhealthy alcohol use” has been proposed as an inclusive term to encompass all problematic drinking behaviors [20]. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) defines “unhealthy alcohol use” as a spectrum of behaviors, from risky drinking to alcohol use disorder (AUD), including harmful alcohol use, abuse, or dependence [21]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), unhealthy alcohol use is an umbrella term that includes “risky or hazardous drinking” that increases the risk for health consequences, and “harmful use” that has already led to health consequences [21]. When epidemiologic studies on the prevalence of alcohol use are reported, the DSM-5 alcohol use disorder (AUD) diagnosis has been frequently used [22]. Although people who do not meet AUD criteria but exceed moderate drinking (2 drinks or less in a day for men and 1 drink or less in a day for women) are also at risk of health problems, the prevalence of alcohol use in this group has been poorly reported [22]. Additionally, the definition of a standard drink varies between countries, which challenges the standardization of measures of alcohol consumption internationally [23]. Consequently, low-risk drinking guidelines show significant variation, with daily limits for women ranging from 10 to 42 g and for men from 10 to 56 g [23]. These discrepancies in standard drink measures and definitions of risky drinking across countries support the need for the term “unhealthy alcohol use.” The term “unhealthy alcohol use” can capture any drinking behaviors between moderate drinking and AUD that were inconsistently explained by different terms, such as problematic drinking, heavy drinking, excessive drinking, risky drinking, and harmful alcohol use [21, 24]. Therefore, unhealthy alcohol use encompasses a broad range of drinking behaviors that threaten individuals’ health [22, 25]. By adopting “unhealthy alcohol use” as a comprehensive term, health professionals can identify and address problematic alcohol use patterns that threaten individuals’ health at an early stage, thereby preventing the negative health consequences of harmful alcohol use.

Understanding the specific mechanism behind the high levels of unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM is crucial. The sexual minority stress model, proposed by Meyer (2003), offers a valuable framework for examining this issue. This model posits that lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals experience unique stressors due to their stigmatized status, which contributes to mental health disparities between sexual minorities and heterosexual populations [26]. Minority stress has been proposed as a critical predictor of mental health outcomes, including unhealthy alcohol use, among LGB populations [27]. A review paper on substance use among LGB youth identifies that minority stress is a risk factor for alcohol use among sexual and gender minority adolescents [28]. Meyer’s minority stress model (2003) suggests that experiencing the stress that comes from sexual orientation-based discrimination can result in harmful mental outcomes such as unhealthy alcohol use and alcohol use disorder. For ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM, who hold multiple marginalized statuses, the impact of both racial and sexual orientation discrimination on unhealthy alcohol use is expected to be even more substantial [29]. This group faces additional stressors, such as ethnic prejudice, discrimination, and acculturation challenges, along with homophobia [30, 31]. These stressors contribute to a heightened sense of isolation and emotional distress, which may in turn, prompt unhealthy coping mechanisms like excessive alcohol consumption and binge drinking. The cumulative effects of these minority stressors, including ethnic, immigrant, and sexual marginalization, amplify the likelihood of unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority GBMSM [32,33,34].

Unhealthy alcohol use in ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM often co-occurs with multiple other health concerns, such as depression, HIV, other sexual health outcomes, and additional substance use [8, 35]. These health issues not only co-occur but also interact synergistically, resulting in a cumulative negative impact on this population’s well-being [36, 37]. Furthermore, unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM is often aggravated by multiple psychosocial and environmental factors. These factors include experiences of discrimination based on race and sexual orientation, exposure to violence, inadequate social support, economic instability, and low socioeconomic status [38]. Despite its significance, research on unhealthy alcohol use within this population remains sparse, and no systematic review has been conducted to date. To fill this research gap, our current study aims to synthesize key findings to elucidate unhealthy alcohol use and its associated factors among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM in North America. Specifically, we seek to answer the following research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM in North America? (2) What are the co-occurring health problems related to unhealthy alcohol use in this population? (3) What are the associated factors with unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM? We hypothesize that ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM experience high rates of unhealthy alcohol use due to compounded stress from racial and sexual orientation discrimination. Additionally, we hypothesize that ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM experience high rates of co-occurring health problems, such as positive HIV status, mental health issues, and other substance use. Furthermore, we expect that associated factors for unhealthy alcohol use include experiences of discrimination based on racial and sexual orientation, as explained in the Minority Stress model. The objectives of this systematic review are threefold: (1) to quantify the prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM, (2) to assess the prevalence of co-occurring health problems in this population, and (3) to examine associated factors with unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. By highlighting these key aspects, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complexities surrounding unhealthy alcohol use within this marginalized population. By addressing these research questions and hypotheses, this systematic review aims to focus on the prevalence, co-occurring health issues, and associated factors with unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM.

Methods

Data Collection

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we systematically searched English publications up to June 2022 using PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. To ensure a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach in our systematic review and meta-analysis, we utilized PubMed for its extensive coverage of biomedical literature, Web of Science for its broad citation network and scientific coverage, and PsycINFO for its specialization in the psychology field. This combination of databases allowed us to gather diverse and high-quality sources, offering a thorough and balanced literature search. The following MeSH and text word terms were combined: (“Emigrants and Immigrants”[MeSH Terms], “Minority Groups”[MeSH Terms], “immigrant*” OR “Ethnic and Racial Minorities”[MeSH Terms] OR “ethnic minority” OR “racial minority” OR “Asian Americans”[MeSH Terms] OR “Hispanic or Latino”[MeSH Terms] OR “Asians”[MeSH Terms] OR “African Americans”[MeSH Terms] OR “Blacks”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“Sexual and Gender Minorities”[MeSH Terms] OR “Homosexuality”[MeSH Terms] OR “homosexuality, male”[MeSH Terms] OR “bisexuality”[MeSH Terms] OR “gay” OR “bisexual” OR “homosexual” OR “MSM” OR “men who have sex with men” AND (“Alcoholism”[MeSH Terms] OR “alcohol abuse” OR “alcohol dependence” OR “alcohol use disorder” OR “alcohol”). The reference lists of all eligible articles were reviewed to identify additional literature relevant to the topic. Articles were considered eligible for inclusion if they meet inclusion criteria, including (1) data-based article (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO), (2) peer-reviewed journal article, (3) studies that included an immigrant ethnic minority population of men self-defined as gay, bisexual men, and MSM, (4) studies that addressed alcohol use results, (5) studies conducted in North America, and (6) studies published in English. Dissertations, posters, and other grey literature were excluded. Two reviewers (WC and CZ) independently examined relevant abstracts and full-text articles to determine whether they met the criteria for inclusion. To ensure consistency and reliability in the selection process, we conducted a thorough review process. The initial agreement between reviewers was assessed, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. This approach ensured a rigorous and unbiased inclusion process.

Key Definitions

In this paper, we used an inclusive definition of “immigrants,” which encompasses both foreign-born individuals and their native-born children, often referred to as culturally and linguistically diverse individuals [39]. This broad categorization is justified by the unique challenges faced by children of immigrants, who often grapple with cultural conflicts between their parents’ heritage and mainstream American society [40]. Evidence showed that culturally and linguistically diverse individuals also face racism, unequal treatment in labor markets, and deviant lifestyles such as engagement in gangs and the drug trade [41]. Furthermore, these individuals are more likely than children of native-born parents to experience poverty, food insecurity, crowded housing, and a lack of public assistance or health insurance [42]. Given the shared adversities faced by both foreign-born individuals and their native-born children, we considered both groups as part of the immigrant populations in this study, differentiating them from children of US-born parents. In this meta-analysis, we also used two definitions of alcohol consumption: (1) recent alcohol use, defined as any drinking behavior within the past year, and (2) unhealthy alcohol use, a spectrum of drinking behaviors that exceed moderate consumption and encompasses risky, hazardous drinking, and harmful alcohol use.

Data Extraction, Synthesis, and Analysis

We created a comprehensive data extraction table to present details from included studies, such as sexual and gender identity, study design, location, ethnicity, immigration status, mean age, and instruments for measuring alcohol use. We reviewed the included articles for the prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use and recent alcohol use, the prevalence of co-occurring health problems associated with unhealthy alcohol use, and the factors related to unhealthy alcohol use. The quality of each study was assessed using two different tools. For cross-sectional and longitudinal study design research articles, we used the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. This tool evaluates several criteria, including study population, participation rate, measurement of variables, and control of confounding factors. Studies were rated as good, fair, or poor quality based on their adherence to these criteria. For qualitative study design research articles, we employed the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool. The CASP tool assesses the clarity of research questions, appropriateness of the qualitative methodology, coherence of the findings, and the consideration of ethical issues. Studies were rated on a scale from high to low quality depending on their performance across these criteria.

The included studies represent diverse populations and settings, necessitating the use of random-effect modeling strategies to weigh and pool individual estimates. Using Stata Metaprop (a statistical program tailored for binominal data), we calculated the pooled prevalence, and the corresponding 95% CIs of recent alcohol use (within 1 year) and unhealthy alcohol use [43, 44]. Second, we conducted meta-analyses of the prevalence of co-occurring health problems, including history of substance use (within 1 year), positive HIV status, and other mental health problems. Third, bivariate random-effects meta-regression was performed to examine the association between alcohol use (recent alcohol use and unhealthy alcohol use) and other factors (e.g., drug use, HIV diagnosis, and mental health problems) [45]. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plots (asymmetry indicating existing publication biases) and Egger’s test (testing the asymmetry statistically). STATA 17.0 (StataCorp L.P., College Station, Texas) was used for all statistical analyses. We also assessed significant factors associated with alcohol consumption. Then, the identified factors were categorized into several key groups.

Results

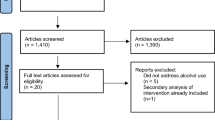

Figure 1 portrays the flow of our search and selection process. Our initial database searches resulted in a total of 1554 studies. After removing the 663 duplicates, we were left with 1131 studies. Next, we excluded the articles that are not data-based, not including immigrant ethnic minority populations, not including gay, bisexual men or MSM populations, not including alcohol use information, not conducted in North America, not published in English, and dissertations and posters. 938 were excluded based on our inclusion criteria after the title and abstract screening, leaving us with a total of N = 193. After the full-text screening, we excluded 173 articles that did not include ethnic minorities, did not include gay, bisexual men, or MSM, did not mention alcohol use, did not have immigration information, and other reasons including dissertations and review papers. We identified 20 studies that met our inclusion criteria.

Among the 2971 participants, 53% were Latino, 45% were Asian Pacific Islanders, and 2% were African. Among the participants, 36% of participants live in the western region of the U.S., 12% live in the Midwest, 18% live in the eastern region, 17% live in the southern region, and 17% live across the country and Canada. Among included studies, there are two longitudinal studies [46, 47], two qualitative studies [48, 49], and sixteen cross-sectional study design studies [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] (See Table 1). The alcohol use instruments used in studies include Quantity-Frequency Index (QFI) [50, 59, 62, 63, 65], Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-concise version (AUDIT-C) [61], DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria [52], Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [53], and behavioral risk assessment tool (BRAT) [55]. Alcohol use-related questionnaires asked of participants include (1) dichotomous questions about whether participants drank alcohol use within a certain period or ever, (2) questions about how many times participants experienced binge drinking (e.g., having five drinks in a single drinking occasion) within a certain period time, and (3) questions about whether participants experienced alcohol use during the most recent sexual activity (See Table 1).

We calculated the pooled proportion of alcohol use and co-occurring health problems. Our meta-analysis revealed that 64% (95% CI 0.50, 0.78) of the participants reported recent alcohol use and 44% (95% CI 0.30, 0.59) reported unhealthy alcohol use. Co-occurring health problems identified in the studies include recent substance use (32%; 95% CI 0.21, 0.45), positive HIV status (39%; 95% CI 0.14, 0.67), and mental health issues (39%; 95% CI 0.21, 0.58), which encompass suicide attempts, suicidal thoughts, depression, and anxiety. The heterogeneity (I-square) for these analyses was high, indicating significant variability across studies: 97.95% for recent alcohol use, 95.06% for unhealthy alcohol use, 96.34% for recent drug use, 98.57% for positive HIV status, and 94.91% for mental health problems. The bivariate meta-regression revealed no statistically significant associations between alcohol use (recent alcohol use and unhealthy alcohol use) and other co-occurring problems (recent drug use, positive HIV status, and mental health problems) among the included participants. Specifically, the meta-regression results showed the following associations with recent alcohol use: recent drug use (0.0023; 95% CI 0.0002, 0.0043; I-square: 95.93%), positive HIV status (0.001; 95% CI − 0.0008, 0.0028; I-square: 94.33%), and mental health problems (− 0.0017; 95% CI − 0.0126, 0.0092; I-square: 95.32%). For unhealthy alcohol use, the associations were: recent drug use (− 0.0003; 95% CI − 0.0073, 0.0036; I-square: 91.46%), positive HIV status (− 0.0007; 95% CI − 0.0086, 0.0071; I-square: 66.12%), and mental health problems (0.0045; 95% CI − 0.0058, 0.0149; I-square: 93.76%).

We also identified 22 factors associated with alcohol use, which were categorized into six key groups (See Table 2). These groups include risky sexual behaviors (N = 8), such as engaging in transactional sex before or after immigration, alcohol enhancing feelings to engage in sexual activity, having more than one sexual partner, being in a relationship with another man, same-sex partnerships, condomless anal intercourse, having a steady partner, and having exchange partners. The second group is discrimination experiences regarding racial and sexual orientation (N = 4), which includes experiencing racial discrimination, being more open about same-sex attraction in the country of origin, encountering homophobic experiences in the country of origin, and facing discrimination. The third group covers abuse and trauma experiences (N = 3), including childhood sexual abuse, history of forced sex before immigration, and intimate partner violence. Socioeconomic status (N = 3) is the fourth group, encompassing factors such as age, housing instability, and country of origin. Mental health issues (N = 2), including depression and recreational drug use, form the fifth group. The final group is club-goers (N = 2), which includes the frequency of clubbing and going to clubs.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis included 20 studies with 2971 participants recruited from across North America. These studies employed various instruments and questionnaires, such as QFI, AUDIT, AUDIT-C, DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder criteria, and BRAT, to gauge alcohol consumption behaviors. Notably, QFI was the predominant measure in these studies, though recent literature shows a trend toward using AUDIT and AUDIT-C. This trend aligns with established guidelines demonstrating that AUDIT and AUDIT-C are widely used and recommended brief screening tools for alcohol use research and practice [66]. Our analyses indicate that 64% (95% CI 50–78%) of participants reported recent alcohol use, and 44% (95% CI 30–59%) reported unhealthy alcohol use. These results are similar to those from a study on the prevalence of recent alcohol use and heavy drinking among ethnoracial minority GBMSM, who are not necessarily immigrant populations, where 64.5% of the population reported alcohol use and 13.9% engaged in heavy drinking [34]. Additionally, we identified other co-occurring health problems, including substance use (32%, 95% CI 21–45%), HIV-seropositivity (39%, 95% CI 14–67%), and mental health issues (39%, 95% CI 21–58%). Substance use prevalence is also similar to the study on ethnoracial minority GBMSM, which showed that 33.1% used marijuana or cannabis and 25.7% consumed stimulant drugs [34].

Our results on co-occurring problems resonate with a nationally representative survey that found a high prevalence of lifetime co-occurring psychiatric and drug use disorders among sexual minority men with AUD, including mood disorders (e.g., major depressive episode) and anxiety disorders (e.g., panic disorder without agoraphobia, specific phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder) [67]. The high HIV-positive rate among GBMSM in our study corroborates past studies that link unhealthy alcohol use among the MSM population with engaging in risky sexual behavior, significantly increasing the risk of HIV acquisition [5, 68]. However, our meta-regression results revealed no statistically significant associations between alcohol use and other co-occurring problems. This result should be interpreted cautiously because a meta-regression can easily be biased when the sample size is small [69]. The high heterogeneity across studies, attributed to differences in study designs, populations, and settings, may also account for this lack of association [69].

In addition to the three co-occurring health issues, we identified six prominent factors associated with unhealthy alcohol use: (1) risky sexual behaviors, (2) experiences of racial and sexual orientation discrimination, (3) experiences of abuse and trauma, (4) socioeconomic status, (5) mental health issues, and (6) being a club-goer. Our study identified associations between unhealthy alcohol use among MSM and factors such as childhood trauma and risky sexual behaviors (e.g., group sex, condomless sex, and having multiple sexual partners) that were often found in MSM studies [70,71,72]. Our findings also support previous research demonstrating a link between experiences of discrimination and unhealthy alcohol use within ethnoracial minority communities, as well as among sexual minority populations [29, 33, 73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Earlier studies have linked sexual orientation-based discrimination to unhealthy alcohol use, especially among bisexuals, Hispanics, and people with less education and lower socioeconomic status [73]. The high rate of unhealthy alcohol use among marginalized people with low socioeconomic status is attributed to limited resources for coping with stress and building resilience, increasing their vulnerability to mental and physical health problems [83].

The underlying mechanisms for these associations can be contextualized within the minority stress framework, which posits that GBMSM are psychologically vulnerable to the cumulative effects of social stressors such as anti-gay sentiments, lack of social support, and discrimination [67]. Earlier studies have shown positive correlations between proximal stressors (e.g., internalized homophobia, anticipated stigma, and concealment) and distal minority stressors (e.g., discrimination and victimization) and coping behaviors like problematic alcohol use [84, 85]. Our findings on associated factors (e.g., experiences of discrimination regarding racial and sexual orientation, experiences of abuse and trauma, socioeconomic status) support existing literature, underscoring the interplay between unhealthy alcohol use and minority stress caused by social circumstances, minority status, and minority identity [26]. Within the minority stress model, coping mechanisms and social support are expected to act as buffers between stress and mental health outcomes [26].

However, immigrant GBMSM may face greater difficulties in accessing such support systems compared to their non-immigrant counterparts. This is often because they are navigating an unfamiliar environment, and frequently, their close family and friends remain in their countries of origin. Acculturative stress factors such as loneliness, social isolation, family separation, and economic concerns significantly contribute to substance use among immigrant GBMSM [15, 86]. The combination of these stressors and the lack of adequate support systems exacerbates their mental health challenges, leading to higher risks of adverse outcomes [86]. Although acculturation-specific stress was not identified as a single associated factor of unhealthy alcohol use in our study, these unique challenges need to be considered in the cultural, social, and economic contexts of immigrant GBMSM. Therefore, we suggest that interventions aimed at reducing unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM should focus on enhancing social support networks, addressing experiences of discrimination and their unique stress, and providing resources to build healthy coping strategies.

It is also important to acknowledge that alcohol can serve as a social lubricant, facilitating social interactions, which may be particularly beneficial for immigrant GBMSM who speak English as a second language. Bars and other social venues serve as key spaces for coping with stress and as places where sexual orientation and gender identity can be openly expressed, away from societal discrimination [87, 88]. A study conducted by Nehl et al. reported that Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) MSM who visit clubs at least once a month have 3.75 times the odds of using alcohol compared to AAPI MSM who do not attend bars [60]. Alcohol consumption in social settings can ease communication barriers and foster a sense of belonging, providing a temporary reprieve from social isolation and loneliness. However, while recognizing this positive aspect, it is crucial to balance this understanding with awareness of the potential for alcohol misuse and the associated health risks.

Strengths

Our review rigorously adhered to PRISMA guidelines and is the first to provide evidence integrating research on alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM and its associated factors. The current study possesses several strengths that enhance its contribution to the literature on unhealthy alcohol use in this understudied group: (1) To account for the inherent heterogeneity across studies, we employed the robust DerSimonian–Laird random-effects modeling techniques. This approach enables us to account for variance both within and between studies, providing more accurate and generalized results. (2) To tailor the binominal nature of the data, we used metaprop to calculate the pooled proportions. This method ensured that the meta-analysis was appropriate for the data type and enhanced the accuracy of our estimates. (3) We employed meta-regression analysis to assess the association between unhealthy alcohol use and other co-occurring health problems. This approach enabled us to explore potential factors that may influence the relationship between alcohol consumption and health outcomes. (4) Our study is the first to quantitatively assess the pooled prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use and other co-occurring health problems among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. As such, it fills a gap in the literature and provides valuable insights into unhealthy alcohol use and its co-occurring health problems faced by this marginalized population. (5) Our findings revealed that the prevalences of recent alcohol use and other substance use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM were similar to those observed in ethnoracial minority GBMSM who are not necessarily immigrant populations. This indicates that immigration does not protect ethnic minority GBMSM from alcohol use, contrary to the general trend where immigrants usually have lower alcohol consumption rates than the non-immigrant population. (6) To identify factors associated with unhealthy alcohol use, we conducted a comprehensive literature review to discern and categorize key factors linked to unhealthy alcohol use in this population. This approach enriched our understanding of the complex interplay between various associated factors and alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. By situating our findings within the minority stress framework, we provided an understanding of how social stressors contribute to unhealthy alcohol use and other health issues among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM. (7) The detailed examination of co-occurring health problems and associated factors offers critical insights for developing targeted intervention and prevention programs. Our findings suggest that addressing mental health support, providing substance use counseling, reducing discrimination, and enhancing social support networks are essential for mitigating unhealthy alcohol use in this population. For immigrant GBMSM, culturally tailored interventions that consider acculturative stress and language are particularly important. By integrating these strengths, our study not only advances the understanding of unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM but also provides a foundation for future research and practical applications in intervention and prevention programs.

Limitations and Implications

Several caveats need to be considered during interpretations. First, our studies are highly heterogeneous due to different study designs, participants, and settings, which may lead to biased pooled estimates. However, using random-effect modeling strategies, we have accounted for the heterogeneity identified across the included studies. Second, the quality of the articles was considered low, primarily due to the potential bias inherent in the cross-sectional design of most studies. Cross-sectional studies and retrospective self-report measures limit our ability to draw definitive conclusions about the causal relationship between identified factors and unhealthy alcohol use. Therefore, we advocate for future research to employ longitudinal designs, which would better capture the temporal relationships between unhealthy drinking and associated factors. This approach would provide a more robust understanding of the temporal sequences involved in alcohol use patterns among this population. Additionally, common limitations in these studies included small sample sizes, lack of control groups, and insufficient detail in reporting methodology. Third, not all the participants are foreign-born immigrants, although we used the broad definition of immigrants in this study, including children of immigrants and second and third-generation immigrants. Some articles did not include immigrant information, such as whether participants were born in the U.S. or foreign countries. As a result, misclassification biases may occur. Nevertheless, we attempted to ensure the inclusion of ethnic minorities GBMSM born in foreign countries whose native languages are not English. Fourth, there is an imbalance in the number of studies available for different ethnic groups. Compared to studies on Latino immigrant GBMSM, studies on African and Asian immigrant GBMSM are not enough to examine their alcohol use patterns. Due to the insufficient number of studies on alcohol use among African and Asian immigrant GBMSM compared to Latino immigrant GBMSM, subgroup analysis on the prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use by ethnicity was unavailable. The National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) survey results indicated that Asian and African immigrants showed lower alcohol use rates than Latino immigrants [12]. Our study populations are ethnic minority immigrant gay, bisexual, and men who have sex with men (GBMSM), whereas the NESARC study analyzed only ethnic minority immigrant populations. Future research needs to investigate potential differences in drinking behavior patterns between ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM and ethnic minority immigrants, and why certain ethnic groups have higher alcohol use than others. Fifth, while we identified and categorized associated factors into six key themes, we did not quantitively calculate the associations between the factors and unhealthy alcohol use. Therefore, the strengths of the association between the factors and unhealthy alcohol use are unknown. We recommend testing the significance and strength of the associations between identified determinants and unhealthy alcohol use among immigrant ethnic minority GBMSM in future research. Sixth, only published English-language studies identified via three databases were included, and thus some relevant studies may have been omitted. Even with these limitations, this review rigorously followed PRISMA guidelines.

Conclusions

This comprehensive meta-analysis systematically evaluated alcohol consumption and associated health issues among ethnic minority immigrant gay, bisexual, and men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in North America. Our findings reveal a significant prevalence of recent alcohol use (64%) and unhealthy alcohol use (44%) among the participants. Additionally, the study observed a high prevalence of co-occurring health problems, namely other substance use, HIV-seropositivity, and mental health disorders. Moreover, the review identified six crucial categories linked to unhealthy alcohol use. These categories, ranging from risky sexual behaviors to the experience of discrimination due to racial and sexual orientation, emphasize the multi-faceted challenges faced by this marginalized group.

This is the first review to provide evidence that integrates research on alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM and its associated factors. This analysis provides a robust foundational understanding of the alcohol use patterns and associated challenges among this vulnerable population. As we move forward, it is imperative for research and public health policies to address these findings, ensuring a comprehensive and targeted approach to support and improve the health outcomes of this vulnerable group. Study findings also provide information that can be used to develop effective clinical prevention and early intervention strategies for reducing unhealthy alcohol use among ethnic minority immigrant GBMSM.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Cheng HG, Kaakarli H, Breslau J, Anthony JC. Assessing changes in alcohol use and alcohol use disorder prevalence in the United States: evidence from national surveys from 2002 through 2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):211–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4008.

Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Kantor LW. The influence of gender and sexual orientation on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: toward a global perspective. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):121–32.

Peralta RL, Victory E, Thompson CL. Alcohol use disorder in sexual minority adults: age- and sex- specific prevalence estimates from a national survey, 2015–2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205: 107673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107673.

Schuler MS, Prince DM, Breslau J, Collins RL. Substance use disparities at the intersection of sexual identity and race/ethnicity: results from the 2015–2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. LGBT Health. 2020;7(6):283–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0352.

Hess KL, Chavez PR, Kanny D, DiNenno E, Lansky A, Paz-Bailey G. Binge drinking and risky sexual behavior among HIV-negative and unknown HIV status men who have sex with men, 20 U.S. cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.013.

Woolf SE, Maisto SA. Alcohol use and risk of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):757–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9354-0.

Green KE, Feinstein BA. Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: an update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(2):265–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025424.

Lewis NM, Wilson K. HIV risk behaviours among immigrant and ethnic minority gay and bisexual men in North America and Europe: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2017;179:115–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.033.

Souleymanov R, Brennan DJ, George C, Utama R, Ceranto A. Experiences of racism, sexual objectification and alcohol use among gay and bisexual men of colour. Ethn Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1439895.

Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(1–2):152–60.

Rodriguez-Seijas C, Eaton NR, Pachankis JE. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders at the intersection of race and sexual orientation: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(4):321–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000377.

Szaflarski M, Cubbins LA, Ying J. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse among U.S. immigrant populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(4):647–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9394-9.

Collins SE. Associations between socioeconomic factors and alcohol outcomes. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):83–94.

Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, Kerr WC. Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcoholism. 2014;38(6):1662–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12398.

Vaeth PA, Wang-Schweig M, Caetano R. Drinking, alcohol use disorder, and treatment access and utilization among U.S. racial/ethnic groups. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(1):6–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13285.

Mulia N, Ye Y, Zemore SE, Greenfield TK. Social disadvantage, stress, and alcohol use among black, hispanic, and White Americans: findings from the 2005 U.S. National Alcohol Survey. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(6):824–33. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2008.69.824.

Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and hispanic Americans. Alcoholism. 2009;33(4):654–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Binge Drinking. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/binge-drinking.htm. Accessed 28 Jun 2023.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2023. Understanding Binge Drinking. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/binge-drinking. Accessed 28 Jun 2023.

Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2018;320(18):1899–909. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16789.

O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Senger CA, Rushkin M, Patnode CD, Bean SI, Jonas DE. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the U.S. preventive services task force. Jama. 2018;320(18):1910–28. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12086.

Volpicelli JR, Menzies P. Rethinking unhealthy alcohol use in the United States: a structured review. Subst Abuse. 2022;16:11782218221111832. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218221111832.

Kalinowski A, Humphreys K. Governmental standard drink definitions and low-risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries. Addiction. 2016;111(7):1293–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13341.

Saitz R, Miller SC, Fiellin DA, Rosenthal RN. Recommended use of terminology in addiction medicine. J Addict Med. 2021;15(1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000673.

Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp042262.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441.

Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S. Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: a meta-analysis. Prev Sci. 2014;15(3):350–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7.

Glass JE, Rathouz PJ, Gattis M, Joo YS, Nelson JC, Williams EC. Intersections of poverty, race/ethnicity, and sex: alcohol consumption and adverse outcomes in the United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(5):515–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1362-4.

Choi KH, Paul J, Ayala G, Boylan R, Gregorich SE. Experiences of discrimination and their impact on the mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):868–74. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.301052.

Lewis NM. Rupture, resilience, and risk: relationships between mental health and migration among gay-identified men in North America. Health Place. 2014;27:212–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.002.

Buttram ME, Kurtz SP. A mixed methods study of health and social disparities among substance-using African American/Black men who have sex with men. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0042-2.

Gilbert PA, Perreira K, Eng E, Rhodes SD. Social stressors and alcohol use among immigrant sexual and gender minority Latinos in a nontraditional settlement state. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(11):1365–75. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.901389.

Paul JP, Boylan R, Gregorich S, Ayala G, Choi KH. Substance use and experienced stigmatization among ethnic minority men who have sex with men in the United States. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2014;13(4):430–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2014.958640.

Carey JW, Mejia R, Bingham T, Ciesielski C, Gelaude D, Herbst JH, Sinunu M, Sey E, Prachand N, Jenkins RA, Stall R. Drug use, high-risk sex behaviors, and increased risk for recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chicago and Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1084–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9403-3.

Martinez O. HIV-related stigma as a determinant of health among sexual and gender minority latinxs. HIV Spec. 2019;11(2):14–7.

Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):941–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30003-x.

Pachankis JE, Eldahan AI, Golub SA. New to New York: ecological and psychological predictors of health among recently arrived young adult gay and bisexual urban migrants. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(5):692–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9794-8.

Pham TTL, Berecki-Gisolf J, Clapperton A, O’Brien KS, Liu S, Gibson K. Definitions of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD): a literature review of epidemiological research in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020737.

Giguère B, Lalonde R, Lou E. Living at the crossroads of cultural worlds: the experience of normative conflicts by second generation immigrant youth. Soc Personality Psychol Compass. 2010;4(1):14–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00228.x.

Portes A, Fernández-Kelly P, Haller W. The adaptation of the immigrant second generation in America: theoretical overview and recent evidence. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2009;35(7):1077–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903006127.

Hamilton ER, Hummer RA, Cardoso JB, Padilla YC. Assimilation and emerging health disparities among new generations of U.S. children. Demogr Res. 2011;25(25):783–818.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.12.

Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-72-39.

van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Stat Med. 2002;21(4):589–624. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1040.

Hahm HC, Wong FY, Huang ZJ, Ozonoff A, Lee J. Substance use among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders sexual minority adolescents: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(3):275–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.021.

Homma Y, Chen W, Poon CS, Saewyc EM. Substance use and sexual orientation among East and Southeast Asian adolescents in Canada. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(1):32–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828x.2012.636687.

Martinez O, Dodge B, Goncalves G, Schnarrs P, Muñoz-Laboy M, Reece M, Malebranche D, Van Der Pol B, Kelle G, Nix R, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behaviors and experiences among behaviorally bisexual latino men in the Midwestern United States: implications for sexual health interventions. J Bisex. 2012;12(2):283–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2012.674865.

Martinez O, Dodge B, Reece M, Schnarrs PW, Rhodes SD, Goncalves G, Muñoz-Laboy M, Malebranche D, Van Der Pol B, Nix R, Kelle G, Fortenberry JD. Sexual health and life experiences: voices from behaviourally bisexual Latino men in the Midwestern USA. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(9):1073–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.600461.

Bruce D, Ramirez-Valles J, Campbell RT. Stigmatization, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender persons. J Drug Issues. 2008;38(1):235–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260803800111.

Choi KH, Operario D, Gregorich SE, McFarland W, MacKellar D, Valleroy L. Substance use, substance choice, and unprotected anal intercourse among young Asian American and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(5):418–29. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2005.17.5.418.

Cochran SD, Mays VM, Alegria M, Ortega AN, Takeuchi D. Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(5):785–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.75.5.785.

Kutner BA, Nelson KM, Simoni JM, Sauceda JA, Wiebe JS. Factors associated with sexual risk of HIV transmission among HIV-positive latino men who have sex with men on the U.S.-México border. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):923–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1449-z.

Levine EC, Martinez O, Mattera B, Wu E, Arreola S, Rutledge SE, Newman B, Icard L, Muñoz-Laboy M, Hausmann-Stabile C, Welles S, Rhodes SD, Dodge BM, Alfonso S, Fernandez MI, Carballo-Diéguez A. Child sexual abuse and adult mental health, sexual risk behaviors, and drinking patterns among latino men who have sex with men. J Child Sex Abus. 2018;27(3):237–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2017.1343885.

Loza O, Provencio-Vasquez E, Mancera B, De Santis J. Health disparities in access to health care for HIV infection, substance abuse, and mental health among Latino men who have sex with men in a U.S.—Mexico Border City. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2021;33(3):320–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1885551.

Martinez O, Arreola S, Wu E, Muñoz-Laboy M, Levine EC, Rutledge SE, Hausmann-Stabile C, Icard L, Rhodes SD, Carballo-Diéguez A, Rodríguez-Díaz CE, Fernandez MI, Sandfort T. Syndemic factors associated with adult sexual HIV risk behaviors in a sample of Latino men who have sex with men in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166:258–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.033.

Martinez O, Muñoz-Laboy M, Levine EC, Starks T, Dolezal C, Dodge B, Icard L, Moya E, Chavez-Baray S, Rhodes SD, Fernandez MI. Relationship factors associated with sexual risk behavior and high-risk alcohol consumption among latino men who have sex with men: challenges and opportunities to intervene on HIV risk. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(4):987–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0835-y.

Martinez O, Wu E, Levine EC, Muñoz-Laboy M, Spadafino J, Dodge B, Rhodes SD, Rios JL, Ovejero H, Moya EM, Baray SC, Carballo-Diéguez A, Fernandez MI. Syndemic factors associated with drinking patterns among Latino men and Latina transgender women who have sex with men in New York City. Addict Res Theory. 2016;24(6):466–76. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2016.1167191.

Molina Y, Ramirez-Valles J. HIV/AIDS stigma: measurement and relationships to psycho-behavioral factors in Latino gay/bisexual men and transgender women. AIDS Care. 2013;25(12):1559–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.793268.

Nehl EJ, Han JH, Lin L, Nakayama KK, Wu Y, Wong FY. Substance use among a National Sample of Asian/Pacific Islander Men who have sex with men in the U.S. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(1):51–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2014.994795.

Ogunbajo A, Anyamele C, Restar AJ, Dolezal C, Sandfort TGM. Substance use and depression among recently migrated African gay and bisexual men living in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(6):1224–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0849-8.

Ramirez-Valles J, Garcia D, Campbell RT, Diaz RM, Heckathorn DD. HIV infection, sexual risk behavior, and substance use among Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender persons. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1036–42. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2006.102624.

Ramirez-Valles J, Kuhns LM, Campbell RT, Diaz RM. Social integration and health: community involvement, stigmatized identities, and sexual risk in Latino sexual minorities. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1):30–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146509361176.

Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Wolfson M, Alonzo J, Bloom FR, Alegría-Ortega J, Eng E. Prevalence estimates of health risk behaviors of immigrant latino men who have sex with men. J Rural Health. 2012;28(1):73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00373.x.

Tori CD. Homosexuality and illegal residency status in relation to substance abuse and personality traits among Mexican nationals. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45(5):814–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198909)45:5%3c814::aid-jclp2270450520%3e3.0.co;2-c.

McNeely J, Adam A (2020) Substance Use Screening and Risk Assessment in Adults.

Lee JH, Gamarel KE, Kahler CW, Marshall BDL, van den Berg JJ, Bryant K, Zaller ND, Operario D. Co-occurring psychiatric and drug use disorders among sexual minority men with lifetime alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;151:167–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.018.

Allen VC, Myers HF, Ray L. The association between alcohol consumption and condom use: considering correlates of HIV risk among black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(9):1689–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1075-1.

Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1559–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1187.

Baliunas D, Rehm J, Irving H, Shuper P. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2009;55(3):159–66.

Shangani S, van den Berg JJ, Dyer TV, Mayer KH, Operario D. Childhood sexual abuse, alcohol and drug use problems among Black sexual minority men in six U.S. cities: findings from the HPTN 061 study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12): e0279238.

Wang K, White Hughto JM, Biello KB, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer KH, Rosenberger JG, Novak DS, Mimiaga MJ. The role of distress intolerance in the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and problematic alcohol use among Latin American MSM. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;175:151–6.

Slater ME, Godette D, Huang B, Ruan WJ, Kerridge BT. Sexual orientation-based discrimination, excessive alcohol use, and substance use disorders among sexual minority adults. LGBT Health. 2017;4(5):337–44. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0117.

Cano M. English use/proficiency, ethnic discrimination, and alcohol use disorder in Hispanic immigrants. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01837-5.

Cheadle JE, Whitbeck LB. Alcohol use trajectories and problem drinking over the course of adolescence. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):228–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510393973.

Factor R, Williams DR, Kawachi I. Social resistance framework for understanding high-risk behavior among nondominant minorities: preliminary evidence. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2245–51. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301212.

Hunte HER, Barry AE. Perceived discrimination and DSM-IV–based alcohol and illicit drug use disorders. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e111–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.300780.

Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(7):1910–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036438.

Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Nieri T. Perceived ethnic discrimination versus acculturation stress: influences on substance use among Latino Youth in the Southwest. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(4):443–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000405.

Savage JE, Mezuk B. Psychosocial and contextual determinants of alcohol and drug use disorders in the National Latino and Asian American Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:71–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.011.

Tran AGTT, Lee RM, Burgess DJ. Perceived discrimination and substance use in Hispanic/Latino, African-born Black, and Southeast Asian immigrants. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2010;16(2):226–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016344.

Hequembourg AL, Dearing RL. Exploring shame, guilt, and risky substance use among sexual minority men and women. J Homosex. 2013;60(4):615–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.760365.

McGarrity LA. Socioeconomic status as context for minority stress and health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2014;1(4):383–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000067.

Lindley L, Bauerband L, Galupo MP. Using a comprehensive proximal stress model to predict alcohol use. Transgender Health. 2021;6(3):164–74. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0042.

Livingston NA, Christianson N, Cochran BN. Minority stress, psychological distress, and alcohol misuse among sexual minority young adults: a resiliency-based conditional process analysis. Addict Behav. 2016;63:125–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.011.

Johnson TP. Alcohol and drug use among displaced persons: an overview. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31(13):1853–89. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089609064003.

Lewis LA, Ross MW. The Gay Dance Party culture in Sydney. J Homosex. 1995;29(1):41–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/j082v29n01_03.

Nemoto T, Operario D, Soma T, Bao D, Vajrabukka A, Crisostomo V. HIV risk and prevention among Asian/Pacific Islander men who have sex with men: listen to our stories. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):7–20. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.7.23616.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Darcey Rodriguez for her help and feedback on literature search strategies.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, W., Zhang, C. Revisiting the Prevalence of Unhealthy Alcohol Use Among Ethnic Minority Immigrant Gay, Bisexual Men, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in North America: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Immigrant Minority Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-024-01629-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-024-01629-y