Abstract

To examine health insurance coverage among the 550,000 U.S.-born minors living in Mexico. Representative data from Mexico’s 2018 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics was used to describe health coverage among persons aged 0–17 living in Mexico (N = 78,370). Multinomial logistic regression models were estimated to identify the association between birthplace (Mexico versus the United States) and health insurance coverage in Mexico. 39% of U.S-born minors living in Mexico in 2018 lacked health insurance compared to just 13% of Mexican-born minors. Logistic regression found that, net of potential confounders, being born in the United States was associated with 87% lower odds of being insured among minors in Mexico. U.S.-born minors disproportionately rely on private insurance programs and are particularly likely to be uninsured in the first year back from the United States. Special attention is needed to ensure access to care among U.S.-born minors in Mexico.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

This study investigates health insurance coverage among the 550,000 U.S.-born minors currently living in Mexico [1]. Many of these children and young adults go to Mexico following the deportation of a parent; other mixed status families relocate preemptively as expanding U.S. immigration enforcement increases the risk of parental removal and family separation [2, 3]. The Great Recession compounded these fears because it disproportionately impacted immigrant-heavy industries, thus displacing many already poor Mexican-origin households [4]. Although some better off immigrant parents with more established U.S. social networks choose to leave their offspring with relatives or friends in the United States [2], Recent evidence shows that between 2010 and 2015 alone, nearly 200,000 U.S.-born minors relocated to Mexico [1]. Many of these children initially return to states along the Mexico-U.S. border. Yet as they have settled, many relocated throughout central and southern Mexico [1].

Mexican-origin Children born in the United States to unauthorized immigrant parents constitute a vulnerable population [5,6,7]. Children in immigrant families experience high levels of economic insecurity, and estimates suggest that 25% of U.S.-born minors with undocumented parents lack health insurance coverage [8,9,10]. As a result, U.S.-born children of Mexican origin often have limited access to routine preventative care while in the United States [8].

When these U.S.-born children relocate to Mexico, they confront a new set of challenges [11, 12]. Mexican-origin children born in the United States often struggle with limited Spanish literacy, and many lack documents necessary to register for school [13, 14]. These challenges are exacerbated by inconsistent or nonexistent federal policies to guide the integration of U.S.-born children into Mexican society [13, 11]. Research shows that U.S.-born children often struggle to adapt to Spanish-language schooling, and their studies suffer as a result [15, 16]. Beyond their schooling, we know little about the integration of U.S.-born children into other essential institutions, such as healthcare. As such, it is unclear the extent to which U.S.-born children in Mexico experience limited access to basic preventative medical care, as is the case in the United States. The well-being of these transnational youth is a matter of critical concern for Mexico and the United States, as many of these U.S. citizens expect to return to the United States 1 day [15, 17]. Informed by recent studies that document low levels of health coverage among recently returned adult migrants [18, 19], this study examines access to medical care among U.S.-born minors living in Mexico.

More than a decade after the implementation of universal healthcare in 2003, Mexican adults who recently returned from the United States remain underinsured [18,19,20]. As of 2014, adult return migrants were 20 percentage-points more likely to be uninsured than adult non-migrants in Mexico [19]. Adults are least likely to be insured in the year immediately following return from the United States, suggesting that entry into Mexican institutions is a gradual process that unfolds over time [19, 20]. With limited knowledge of Mexican institutions and often lacking necessary documentation with which to demonstrate citizenship, U.S.-born children may also struggle to enroll in Mexican health insurance programs [13]. After investigating U.S.-born children’s overall health coverage and their affiliation with specific programs, I examine variations in health coverage by time since return to Mexico.

Methods

Data Source and Dependent Variable

Data comes from the 2018 wave of Mexico’s National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID). The ENADID uses a multi-stage probability design to yield nationally representative estimates across geographic regions and community-sizes. It has been widely used to study Mexico-U.S. migration, including a recent examination of health coverage among adult return migrants [19]. This study includes respondents aged 0–17 who were listed as children of the household head and of Mexican origin (the household head was born in Mexico). Minors who were not children of the household head were excluded because their parents’ birthplace was unobservable (the results were substantively unchanged in models using all respondents aged 0–17). The 2018 ENADID contained 78,370 minors who were born in either Mexico or the United States. U.S.-born minors were dichotomously identified using birthplace (born in U.S. = 1). The ENADID does not record children living in the United States at the time of the survey.

The sample included 1454 U.S.-born children (1.5% of the total). Some of the U.S.-born children may have gained citizenship following their parents’ strategic decisions to give birth in the United States. However, these dual citizens likely contribute only a modest number to the total sample. Harpaz estimates that about 4800 Mexican children are strategically born in the United States each year, suggesting that these privileged dual citizens compose only a small fraction of the 550,000 U.S.-born minors now living in Mexico [1, 21].

Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care

Mexico has a segmented healthcare system, which includes employment-based social security (IMSS), a public option (Seguro Popular), and various private programs. For in-depth discussions of Mexico’s healthcare system, see Knaul et al. [22] and Wassink [19]. For a recent critique, see Molina Palazuelos [23]. Because Mexican migrants tend to work informally and Mexican return migrants disproportionately rely on Seguro Popular [19], health insurance coverage was separated into four categories: none (uninsured), employment-based (IMSS or coverage through government employment), public program (Seguro Popular or other public source), or private. Table S1 in the online supplement describes each of Mexico’s health insurance programs in more detail. Less than 0.15% of the sample (129 minors) reported other insurance as their coverage. These respondents were dropped from the analysis. The ENADID does not measure affiliation with U.S. insurance programs such as Medicaid or CHIP. Thus, this study focused on access to medical care in Mexico. There were only modest differences in health coverage between border and non-border residents, suggesting that relatively few U.S.-born minors strategically live along the U.S.-Mexico border in order to receive medical care in the United States.

Recent U.S. Migration Experience

The ENADID collects detailed information about migrations that occurred within the 5 years before the survey but does not record earlier migrations. Respondents specify their country of residence 5-years and 1-year before the survey. This information was used to identify minors with U.S.-migration experience and U.S.-born children with less time spent in Mexico. Respondents who lived in the United States both 1- and 5-years prior were coded as 1-year residents to reflect their most recent U.S. trips. Five-year residents include those who were in the United States 5 years but not 1 year before the survey. Sixteen minors lived in the United States in the previous 5 years but were in Mexico one and 5 years before the survey. Those who returned before 2017 were classified as 5-year residents, and those who migrated and returned in the last year were classified as 1-year residents. Thus, models controlled for U.S. residence within the 5 years before the survey.

Other Child Characteristics

Children’s educational progress measured the completion of progressions through Mexico’s educational system: none (includes children five and younger), primary school incomplete (0–5 years), completed primary (6–8 years), completed lower secondary (9+ years). Because school enrollment is a crucial challenge for U.S.-born children in Mexico [13, 14], respondents’ current school enrolment was dichotomously identified. All models adjusted for children’s sex, age, and age-squared.

Household Socioeconomic Context

The education of the household head, health insurance coverage of the household head, migration experience of the household head, employment-status of the household head, and total household assets were included to capture household socioeconomic status. The same educational categories were used for the household head as for their children, with the addition of upper-secondary complete (12+ years, equivalent to U.S. high school). The household head’s health insurance and migration experience was also measured using the same categories as for children. Parents’ insurance status affects children because adults commonly affiliate their dependents with their programs. A parents’ migration experience could reduce children’s access to coverage because recently returned adult migrants frequently lack health coverage [19].

Employment of the household head is relevant because children can enroll in IMSS or other employment-based programs through their parents. The ENADID classifies economically active respondents as employees, regular workers, day laborers, self-employed without employees, employers, and workers without pay. Following Wassink [19], respondents who described themselves as employees or regular workers were coded as regularly employed to reflect their more stable occupational statuses likely to confer employment-based insurance. Day laborers and self-employed individuals without employees were classified as irregularly employed owing to the marginal nature of these occupational statuses, while employers were separated to reflect business formation as a strategic economic strategy [24].

Principal component analysis was used to construct a composite indicator of household assets, which included items ranging from home ownership and quality to utilities to possession of appliances and vehicles and is a strong predictor of household income and expenditures [25].

Household and Contextual Controls

Several control variables were included to capture other aspects of children’s context, which may affect their access to healthcare. Models dichotomously adjusted for the household head’s marital status (married/cohabitating). Models also included a continuous variable that measured the number of residents in each child’s household. All the models were adjusted for community size (less than 2500 inhabitants, 2500 to 14,999 inhabitants, 15,000 to 99,999 inhabitants, or 100,000 plus). These cutoffs reflect the information provided by the ENADID and correspond to Mexico’s official census classifications. Rural areas tend to have weaker infrastructure and more limited access to services, such as healthcare [23]. To account for differences in state-level infrastructure and migrant-clustering in particular regions [26], all models included state-fixed effects.

Analytic Strategy

First, bivariate differences in health insurance coverage between Mexican-born and U.S.-born minors living in Mexico were examined. Then, two logistic regression models were estimated to identify the adjusted association between birthplace and health insurance coverage. Next, multinomial logistic regression was used to regress the odds of enrollment in employment-based coverage, public coverage, or private coverage on birthplace, net of other covariates. Finally, predicted probabilities of health coverage were estimated among Mexican- and U.S.-born minors by length of residence in Mexico to assess the extent to which coverage may increase as children become more settled. Probability weights were used to adjust for the survey’s complex design and provide nationally representative estimates.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents means and proportions overall and by birthplace. In 2018, 39% of all U.S.-born minors living in Mexico were uninsured compared to just 13% of those born in Mexico. Although U.S.-born mionrs were disproportionately unaffiliated with employment-based coverage (23% versus 35%), they were also a sizeable 25 percentage points less likely than those born in Mexico to affiliate with the country’s universal healthcare program, Seguro Popular, or another public program. Thus, consistent with recent studies of adult return migrants, U.S.-born children were substantially underinsured despite Mexico having a well-established universal healthcare program.

There was mixed evidence of socioeconomic disadvantage among U.S.-born youth living in Mexico. U.S.-born children reported similar educational attainment to those born in Mexico, and, despite evidence that U.S.-born children often struggle to integrate into Mexican schools [13], U.S.-born minors were more likely than their Mexican-born peers to be enrolled in school. Consistent with previous research on Mexico-U.S. migration [27], U.S.-born children also lived in wealthier households than minors born in Mexico. However, it is important to note that migrants’ accumulated wealth often reflects years of remittances, but does not necessarily connote successful integration into the Mexican labor market [28].

Indeed, being the parent of a U.S.-born child was associated with a modestly lower rate of regular employment, and a corresponding reduction in the likelihood of having either employment-based or public health insurance coverage. Moreover, although business formation can enable economic mobility among those with little schooling, Mexican return migrants most commonly operate small businesses in the informal sector of the economy, which would not provide access to employment-based health coverage [29]. Thus, although U.S.-born youth bear some markers of socioeconomic advantage, these advantages might not enhance health insurance coverage within Mexico. Moreover, U.S.-born children were more likely than Mexican born youth to reside in small rural communities, which often have quite limited healthcare infrastructure [23].

U.S.-born children were much more likely to have recently lived in the United States than their non-migrant peers. However, the majority (90%) had not lived in the United States in the 5 years before the survey. Thus, most U.S.-born minors appeared to be settled in Mexico, a pattern consistent with the high rate of school enrollment among U.S.-born children.

Multivariable Results

Adjustment for socioeconomic and demographic factors increased the negative associations between U.S. birth and health coverage among minors in Mexico (Table 2). Thus, it appears that migrant households’ asset advantage and high rate of business formation do not confer the same advantages that they might among non-migrant households. Being born in the United States was associated with 89% lower odds of having health insurance coverage (Model 1). Adjustment for children’s recent U.S.-residence and school enrollment only marginally attenuated this negative association. However, note that recent U.S. residence was associated with a large decrease in the odds of having health coverage among Mexican children, a result consistent with findings among adult return migrants [19, 20].

Among children with health coverage (Table 3), being born in the United States was associated with 2.5 times higher odds of having private insurance, but was uncorrelated with the odds of having public coverage. Children’s program affiliation was strongly linked to that of their household heads. Children in households with businesses and greater asset holdings were also more likely to affiliate with private insurance programs, suggesting that these sources of wealth but not formal employment may encourage households to procure private coverage rather than affiliating with a public program. Table 3 shows that, as is the case among return migrant adults, universally available health insurance does not appear to mitigate U.S.-born children’s lack of coverage through employment-based programs.

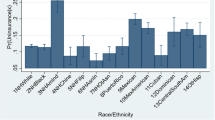

Figure 1 plots predicted probabilities of program affiliation by children’s recent migration experience based on a multinomial logit model that estimated program affiliation with uninsured serving as the reference category—the model adjusted for all control variables included in Table 3. U.S.-born children who lived in the United States in the previous 5 years had a 60% probability of being uninsured, compared to about 20% among return migrant Mexican-born children. The likelihood of uninsurance falls below 40% among more settled U.S.-born children who have lived in Mexico for at least 5 years. Thus, recent U.S. residence is associated with substantial uninsurance among U.S.-born minors in Mexico. Yet, U.S.-born children appear to integrate into Mexican institutions over time, as is the case among adult return migrants [19]. Indeed, note the steady increase in affiliation with public insurance programs, from just 15% among 1-year residents to about 25% among 5-year residents, to nearly 40% among those in Mexico for 5 or more years.

Predicted probabilities of health insurance coverage program by length of residence in Mexico (0–1 years, 1–5 years, 5 or more years) based on a multinomial logistic regression model that regressed health insurance coverage with uninsured as the reference category on all of the variables included in Table 3

Models (not shown) investigated potential variations in health coverage by school enrollment, parental migration experience, employment, and residence in border states. These models (available upon request) did not reveal significantly distinct enrollment patterns between Mexican-born and U.S.-born minors.

Discussion

This study used a nationally representative sample of Mexican-origin youth to assess health insurance coverage and access to medical care among U.S.-born minors in Mexico. Despite extensive scholarship on the challenges faced by Mexican-origin children living in mixed status households in the United States [2, 5, 6], less is known about how Mexican-origin youth born in the United States fare in Mexico. This study documented a high rate of uninsurance (39%) among U.S.-born minors living in Mexico, even higher than the level of uninsurance among U.S. citizens living with undocumented parents in the United States. Sociodemographic characteristics, migration history, school enrollment, community size, and state of residence did not explain this disparity, suggesting a high degree of vulnerability to both chronic and emergency medical conditions among U.S.-born children living in Mexico.

The lack of affiliation with employment-based insurance programs may reflect high levels of labor market informality within migrant households [30, 31]. Yet, disaffiliation with Seguro Popular suggests that institutional barriers and a lack of institutional support also limit health insurance coverage among U.S.-born children struggling to integrate into Mexican institutions, often without essential documents or Spanish literacy. Some Mexican families with U.S.-born children may voluntarily opt out of public health insurance in favor of private healthcare. Indeed, U.S.-born minors were more than five times as likely as those born in Mexico to have private coverage. However, their greater enrollment in private insurance programs only marginally accounted for U.S.-born children’s low levels of enrollment in employment-based and public healthcare programs.

It is also possible that some U.S.-born children living in Mexico continue to receive medical care in the United States. This possibility is unlikely to account for a significant proportion of the overall gap in coverage, however, given that only 10% of U.S. born minors had been in the United States in the last 5 years, only 1.8% in the year before the survey, and only 8% reported household members living in the United States.

Even if U.S.-born youth seek medical care in the United States, the results suggest that most do so without health insurance coverage. Only 11% of U.S.-born children in Mexico reported private health insurance that could include Medicaid, Chip, or other U.S. programs. Moreover, affiliation with private insurance programs was lowest in border states where U.S.-born children could most easily receive medical care in the United States. More research is needed to understand where U.S.-born children living in Mexico receive medical attention and how they pay for their healthcare.

My results suggest that uninsurance results partially from the disruptiveness of international relocation. The probability of being uninsured declined steeply among U.S.-born minors living in Mexico continuously for more than 5 years. Studies of adult return migrants in Mexico find that U.S.-migration can disrupt access to medical care [20], but that health coverage increases with time since return and is related to other aspects of reintegration, such as entry into the formal labor market [19]. My results point to a similar process among U.S.-born children, particularly given the steep increase in the probability of public coverage with more time in Mexico (see Fig. 1).

One strategy to expedite enrollment among U.S.-born children living in Mexico would be to integrate school and healthcare enrollment. This analysis documented a high rate of school enrollment among U.S.-born children, demonstrating that most are already affiliated with one major Mexican institution. Zuniga et al. find that U.S.-born children in Mexico are concentrated in migrant-sending municipalities, a pattern consistent with the regional emergence of migration networks [16]. Schools in these migrant-sending municipalities, which can be identified with data from the Mexican Census, could constitute strategic targets for healthcare enrollment. At the same time, the United States should take steps to improve access to U.S.-healthcare for U.S.-born children living in Mexico, especially those along the border. Given the prevalent intention to 1 day return to the United States, the long-term health of these vulnerable minors has broad implications for the United States [17].

References

Masferrer C, Hamilton ER, Denier N. Immigrants in their parental Homeland: half a million U.S.-born minors settle throughout Mexico. Demography. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00788-0.

Berger Cardoso J, Hamilton ER, Rodriguez N, Eschbach K, Hagan JM. Deporting fathers: involuntary transnational families and intent to remigrate among salvadoran deportees. Int Migr Rev. 2016;50:197–230.

Silver A. Rediscovering home: theorizing return migration among 1.5-generation returnees and deportees in Mexico. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, New York, NY; 2019.

Gonzalez-Barrera A. More Mexicans leaving than coming to the U.S. [Internet]. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. https://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the-u-s/.. Accessed 12 Apr 2016.

Dreby J. The Burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:829–45.

Henderson SW, Baily CDR. Parental deportation, families, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:451–3.

Yoshikawa H. Immigrants raising citizens: undocumented parents and their children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011.

Gelatt J. Immigration status and the healthcare access and health of children of immigrants. Soc Sci Q. 2016;97:540–54.

Terriquez V, Joseph TD. Ethnoracial inequality and insurance coverage among Latino young adults. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:150–8.

Ziol-Guest KM, Kalil A. Health and medical care among the children of immigrants. Child Dev. 2012;83:1494–500.

Hernández-León R, Zúñiga V. Introduction to the special issue. Mex Stud. 2016;32:171–81.

Zúñiga V, Hamann ET. Going to a home you have never been to: the return migration of Mexican and American-Mexican children. Child Geogr. 2015;13:643–55.

Jensen B, Jacobo M. Schooling for US-Citizen Students in Mexico [Internet]. Los Angeles: University of California; 2018. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4zc8b0nh.. Accessed 16 Feb 2019.

Medina D, Menjívar C. The context of return migration: challenges of mixed-status families in Mexico’s schools. Ethn Racial Stud. 2015;38:2123–39.

Panait C, Zúñiga V. Children circulating between the U.S. and Mexico: fractured schooling and linguistic ruptures. Mex Stud Mex. 2016;32:226–51.

Zúñiga V. Students we share are also in Puebla, Mexico: Preliminary findings from a 2009–2010 survey. In: Hamann ET, Sánchez García J, editors. Mex Migr U S. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2016. p. 248–264.

Zúñiga V, Hamann ET. Sojourners in Mexico with U.S. school experience: a new taxonomy for transnational students. Comp Educ Rev. 2009;53:329–53.

Wassink JT. Implications of Mexican health care reform on the health coverage of nonmigrants and returning migrants. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:848–50.

Wassink JT. Uninsured migrants: health insurance coverage and access to care among Mexican return migrants. Demogr Res. 2018;38:401–28.

Martinez-Donate AP, Ejebe I, Zhang X, Guendelman S, Lê-Scherban F, Rangel G, et al. Access to health care among Mexican migrants and immigrants: a comparison across migration phases. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28:1314–26.

Harpaz Y. Citizenship 2.0: dual Nationality as a global asset. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2019.

Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, García-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Lloréns M, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380:1259–79.

Molina RL, Palazuelos D. Navigating and circumventing a fragmented health system: the patient’s pathway in the Sierra Madre Region of Chiapas. Mexico Med Anthropol Q. 2014;28:23–43.

Mandelman FS, Montes-Rojas GV. Is self-employment and micro-entrepreneurship a desired outcome? World Dev. 2009;37:1914–25.

Filmer D, Scott K. Assessing asset indices. Demography. 2011;49:359–92.

Masferrer C, Roberts B. Going back home? changing demography and geography of mexican return migration. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2012;31:465–96.

Garip F. Repeat migration and remittances as mechanisms for wealth inequality in 119 communities from the Mexican migration project data. Demography. 2012;49:1335–600.

Hagan JM, Wassink JT. Return Miration around the World: An Integrated Agenda for Future Research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-120319-015855.

Sheehan CM, Riosmena F. Migration, business formation, and the informal economy in urban Mexico. Soc Sci Res. 2013;42:1092–108.

Parrado EA, Gutierrez EY. The changing nature of return migration to Mexico, 1990–2010. Sociol Dev. 2016;2:93–118.

Villarreal A, Blanchard S. How job characteristics affect international migration: the role of informality in Mexico. Demography. 2013;50:751–75.

Funding

Funding was supported by Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences (Grant No. 1808888) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (US) (Grant No. P2CHD047879).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Research Involving Human and Animals Participants

This research did not involve human or animal participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wassink, J.T. Out of Sight and Uninsured: Access to Healthcare Among US-Born Minors in Mexico. J Immigrant Minority Health 22, 448–455 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00997-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00997-5