Abstract

The enduring and detrimental impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on later health and wellbeing is now well established. However, research on the relationship between ACEs and subjective wellbeing, along with the potential risk and protective factors, is insufficient in the context of developing countries. The current study therefore, examined the mental health of young adults from a wellbeing perspective in a community emerging from a longstanding war. A national representative sample of college students was withdrawn from the Eritrean Institutions of Higher Education using a stratified systematic sampling (N = 507). Data regarding ACEs, resilience, depression symptoms, and subjective wellbeing were obtained through a direct administration of survey questionnaire. Mediation and moderation effects were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results revealed that ACEs were negatively associated with resilience. In turn, resilience was correlated with lower depression and higher subjective wellbeing. ACEs had a positive association with depression, which in turn was negatively related to subjective wellbeing. Further, depression and resilience independently and jointly fully mediated the effect of ACEs on subjective wellbeing. Targeted interventions should be tailored to enhance resilience and prevent depression in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A substantial body of literature has consistently linked adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to poor wellbeing (Oshio et al. 2013; Hughes et al. 2017; Mosley-Johnson et al. 2019) and lifetime and recent depressive disorders (Chapman et al. 2004). The World Mental Health Survey reported that childhood adversities accounted for 29.8% of all mental health disorders worldwide (Kessler et al. 2010). Additionally, according to the Global Burden of Disease Study, depressive disorders rank as the second-highest attributable cause of years lost to disability in young people (Mokdad et al. 2016), showing the widespread prevalence and impact of depression.

The mental health of young adults in Eritrea is of particular research interest due to the impact of war and postwar challenges on families and communities. War or postwar trauma is highly prevalent among Eritreans (Graf 2018; Akresh et al. 2012), as Eritrea has only enjoyed 7 years (1991–1997) of complete peace since the end of World War II. The Ethiopian war of 1998–2000 marked the beginning of a no-peace no-war situation in Eritrea. Studies show that, in addition to the evident consequences of war, including broken family structures, displacement, and exposure to violence, the economic burden and psychological traumas, though primarily faced by parental figures, result in higher risks for ACEs among children (Nurius et al. 2012). Research has also documented the possibility of intergenerational transmission of trauma (Yehuda and Lehrner 2018), emphasizing the longstanding impact of war on communities. Young adults in Eritrea have grown up in the aftermath of the war, with many born during a time of active warfare, making this population an important and unique cohort to study depression and wellbeing. Besides the exposure to potential external and societal adversities, college students have additional unique stressors, including adapting to new college environments (Alonso et al. 2018), academic pressures, and developmental turbulences associated with the transition to adulthood (Arnett 2012; Newcomb-Anjo et al. 2017). Moreover, nearly three-quarters of all lifetime mental health problems first occur during this developmental period of young adulthood (Auerbach et al. 2018). Further, the wellbeing of college students is seen to decline after joining college (Ratanasiripong et al. 2018), and college students are more vulnerable to depression compared to the general population (Ibrahim et al. 2013).

The mental health and wellbeing of young people in Eritrea face additional challenges due to the deep-rooted stigma and unavailability of mental health services. Mental health is viewed categorically as the presence or absence of psychological symptoms. A shift from this pathological perspective to promoting positive mental health resources such as resilience and subjective wellbeing seems more crucial in this context. It has been widely recognized that enhancing positive mental health resources and reducing risks help people thrive and/or flourish in the face of adversity ( Luthar et al. 2014). Therefore, to help break the generational cycle of wartime adversities in the resource-limited setting of Eritrea, it is essential to identify modifiable risk and protective factors affecting the mental health and wellbeing of young people.

1.1 The Link of ACEs to Subjective Wellbeing and Depression

Wellbeing as a general concept is an integral part of the WHO definition of health—“not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” but “a state of wellbeing” (Vik and Carlquist 2018). There are several definitions and measures around the concept of subjective wellbeing (Diener et al. 2018). Nonetheless, based on the judgment model of subjective wellbeing, it could be described as an individual’s cognitive and affective global judgment of his/her life (Schwarz and Strack 1991). Subjective wellbeing is becoming an important measure of the health and wellbeing of individuals and societies (Diener 2006). Due to poverty and structural barriers to health services, subjective wellbeing could be more related to health in the least developed countries such as Eritrea (Ngamaba et al. 2017).

While a large base of evidence has indicated the link of ACEs to later mental and physical health problems, the focus is also growing to look into the association of ACEs and positive aspects of mental health including subjective wellbeing. Adults with a history of childhood adversity were more likely to report significantly low adulthood subjective wellbeing as compared to those with lesser negative experiences (Bellis et al. 2013). Corcoran and McNulty (2017), for example, found that childhood adversities indirectly reduced subjective wellbeing through attachment mechanisms among university students. Likewise, Oshio et al. (2013) indicated that ACEs had considerably reduced subjective wellbeing during adulthood. More so, several childhood bullying experiences were associated with a significant reduction of the subjective wellbeing of undergraduates in Spain (Víllora et al. 2020). Further, ACEs substantially impacted general wellbeing through early-onset depression and other health-harming behaviors (Giovanelli et al. 2016; Scott et al. 2011). ACEs negatively affect subjective wellbeing by several mechanisms. The neurobiological perspective highlights that ACEs over-activate brain structures in charge of emotion-laden memories, while at the same time disrupting neutral memories (Payne et al. 2007). ACEs are also related to alterations of the mesolimbic dopamine system and over stimulation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA), structures involved in reward processes and the regulation of stress respectively (Koss and Gunnar 2018). Reduced mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission is associated with depressed mood (Pizzagalli et al. 2008), while its activation is related to resilient attributes (Dutcher and Creswell 2018). Moreover, ACEs have been shown to threaten one’s capacity to cope with stress through the disruption of neurobiological mechanisms and the alteration of psychological and epigenetic circuitries (Shonkoff et al. 2009). These changes may consequently inhibit the development of cognitive foundations of resilience, including attachment ( Luthar et al. 2015; Fergusson and Horwood 2003), positive emotions (Tugade and Fredrickson 2004), and sense of purpose (Sagone and De Caroli 2014). Research found that children with secure-attachments to significant others showed less sensitivity to stress and higher resilience capacity (Marriner et al. 2014). Likewise, children with adaptive emotion regulation strategies following ACEs showed reduced negative psychological outcomes (McLafferty et al. 2020). Liang et al. (2018) also revealed that college students in China who were left behind by parents during childhood reported much lower scores of hope, optimism and self-efficacy. After relief from ACEs, altered cognitive functions tend to improve. However, structures related to emotion regulation, reward execution, and affective functioning hardly show improvement, even decades after the experience of adversity (Herzog and Schmahl 2018; Pechtel and Pizzagalli 2011). This could be one reason why affective disorders and reduced level of wellbeing are commonly seen among adults with a history of ACEs (Chapman et al. 2004). Likewise, not only do ACEs strongly predict later depressive symptoms (Blum et al. 2019), but they also increase the vulnerability of experiencing further stressors later in life (Mc Elroy and Hevey 2014). Indirect pathways through which ACEs proliferate stress to compromise later mental health outcomes included lack of social support, low income and adversity during adulthood (Jones et al. 2018). On the other hand, in a sample of Japanese adults, Oshio et al. (2013) found that a large proportion of the impact of ACEs on subjective wellbeing remained unexplained by the mediated or moderated effects of social support and low socioeconomic status. Hence, potential conduits through which ACEs lead to poor subjective wellbeing later in life may be through mental health problems such as depression or through personal attributes like psychological resilience.

1.2 Protective Role of Resilience

Not all people with a history of ACEs suffer depression and poor wellbeing later in life. One important protective factor against the toxic stress of ACEs is resilience (Werner 2009). Resilience is defined as the dynamic ability of an individual to “bounce back” in the face of adversity (Connor and Davidson 2003). Resilient individuals have better wellbeing and lower risk of developing psychopathology (Meng et al. 2018). Studies showed that resilience was negatively correlated with depression (Min et al. 2013) and positively with wellbeing (Satici 2016). Individuals with resilient characteristics tend to rely on efficient utilization and mobilization of personal coping resources to overcome adversities, which leads to the feeling of wellbeing. They also show better-coping skills and affect regulation than their non-resilient counterparts (Agaibi and Wilson 2005). Further, people with resilient capacities have a positive orientation towards themselves the environment and the future (Mak et al. 2011). This perception may help them buffer any negative biological and psycho-emotional stress responses which may increase their wellbeing and reduce depression (Southwick and Charney 2012).

Recent studies have pointed out the importance of examining pathways by which resilience provides an advantage to students at institutions of higher education, specifically in regard to withstanding ACEs (Oehme et al. 2019). For example, researchers have implicated that resilience enhances wellbeing and protects against the effects of ACEs among college students (Mello 2016; Theron and Theron 2014). Moreover, among Chinese university students, Chen (2016) found that resilience had a direct and positive effect on subjective wellbeing. Hartley (2012) also documented that college students who sought help from university counseling centers had lower resilience and greater psychological disturbance. Available evidence has guided many researchers to advocate the value of resilience as key for the wellbeing of college students (Holdsworth et al. 2018; Johnson et al. 2015; Hartley 2011, 2012). Yet, most previous studies have not explored the cumulative effect of ACEs on subjective wellbeing and the underlying mediating factors (both risk and protective) in youth emerging from a long-standing war.

In summary, the relationships between ACEs, resilience, depression and wellbeing appear quite intermingled. That is, bidirectional influence and causation are possible in the relationship of these constructs (Diener et al. 2017; Fredrickson and Joiner 2002). Their relationship is further complicated, as they are all confounded by genetic and personality traits (Migliorini et al. 2013). However, it is quite convincing that ACEs are critical factors to lay the ground for and impact later wellbeing (Felitti and Anda 2009).

1.3 The Current Study

With a global increase in the prevalence of common mental health problems among the youth (Eisenberg et al. 2016; Evans-Lacko and Thornicroft 2019; Castillo and Schwartz 2013), a significant decline in resilience among college undergraduates is also detected (Gray 2015; Oehme et al. 2019). Early adulthood is a developmental period when new risks like depression appear (Shapero et al. 2019). Hence, this period gives a crucial window for understanding mental health risks and protective factors. Although mental health has received substantial attention in high-income countries, specifically among young adults, the same is not true for the low-income (Atilola 2015). Eritrean youth are an under-researched population, and they live in a socio-politically complex culture accompanying political unrest. Therefore, identifying contextual factors affecting the subjective wellbeing of young people is essential to inform practice and lay the ground for future studies. Existing literature suggested that the effect of ACEs on psychological adjustment (i.e., depression and wellbeing) could be moderated or mediated by resilience (Hoppen and Chalder 2018). Youssef et al. (2017), for instance, found that higher resilience moderated the effect of ACEs on depression among young adults. Similarly, Poole et al. (2017) have shown that the negative impact of ACEs on depression is moderated by psychological resilience in primary care adults. Moreover, resilience resources moderated ACEs’ effect on perceived wellbeing in a large sample of American adults (Nurius et al. 2015). While the above-mentioned studies have documented that resilience appears to moderate the associations between ACEs and mental health outcomes, others indicated both moderating and mediating effects of resilience in the relationship between childhood adversities and depression (Ding et al. 2017). The effect of childhood abuse among socio-economically disadvantaged women was mediated by resilience on post-traumatic stress symptoms (Hong et al. 2018). A longitudinal cohort study indicated that the mediation role of resilience reduced the relationship between ACEs and wellbeing among adolescents and emerging young adults (Giovanelli et al. 2016). Several longitudinal research also linked the significant mitigating role of resilience to ACEs and later positive mental health outcomes of young adults (Werner 1989; Masten et al. 2004, 2006; Fergusson and Horwood 2003). More so, Fossion et al. (2013) found that the effects of traumas on depression and anxiety among children who have survived the Nazi holocaust were mediated by resilience. Depression, on the other hand, is also shown to mediate the effects of childhood adversities on multiple health-harming behaviors including risk-taking and drug abuse (Solakoglu et al. 2018; Guo et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2018), which may subsequently compromise subjective wellbeing in the long term. Consistent with prior inquiry (Chen 2016; Lu et al. 2017; Karatzias et al. 2017), we hypothesize (1) ACEs, depression and resilience predict subjective wellbeing, (2) Resilience and depression moderate or mediate the effects of ACEs on subjective wellbeing.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

There are seven colleges in the Eritrean institute of higher education and research. The total number of undergraduate degree students in these colleges was 5740. Paper–Pencil based questionnaires were self-administered among undergraduate students from all seven colleges in November 2018. This study applied a stratified systematic sampling to obtain a representative sample of undergraduate degree students. First, the sampling frame was stratified based on students’ year of study (Year 1–6). Next, students were selected through a systematic sampling from an alphabetically arranged name list, with a sample interval of 10. Selected participants were approached through their teachers and head departments in a classroom. A total of 564 students participated in this survey, and data for 507 respondents were eligible for analysis, indicating a response rate of 89.9%. The study was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards. All participants provided written informed consent.

2.2 Measures

Demographic characteristics including gender, age, college, department, year of study, growing up with both parents, setting of residence before college (urban, rural), ethnicity (Tigrigna, others) and parental college education were also collected.

2.2.1 Subjective Wellbeing

The World Health Organization’s five wellbeing index (WHO-5) was used to measure subjective wellbeing (WHO 1998). WHO-5 index mainly reflects basic subjective states of wellbeing such as positive mood, vitality and general interests (Hochberg et al. 2012). It measures subjective wellbeing as a unidimensional construct in a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “at no time” (0) to “all of the time” (5). Higher scores represented better subjective wellbeing. The composite reliability in current study was 0.82, with a 95% confidence interval (0.79, 0.85).

2.2.2 ACEs

The Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) was utilized to assess adverse childhood experiences (WHO 2018). It contains 29 questions regarding exposures to 13 categories of ACEs: emotional abuse; physical abuse; sexual abuse; emotional neglect; physical neglect; domestic violence; living with household members who were substance abusers; living with household members who were mentally ill or suicidal; living with household members who were imprisoned; one or no parents, parental separation or divorce; bullying; community violence; and collective violence. The summary score of ACEs ranged from 0 to 13, with higher scores indicating greater exposure to ACEs. In this study, we employed the frequency scoring approach to estimate ACE exposure. According to the guidance for ACE-IQ (WHO 2018), only 5.5% of college students reported physical neglect or physical abuse. However, child physical abuse and neglect are quite common and widely complicated by structural and deeply rooted sociocultural norms. For instance, parents have the right to disciplining the child and corporal punishment is widely prevalent in families and schools (Plastow 2007; Terhune 1997). Therefore, we modified the scoring of physical neglect and physical abuse. Specifically, responses of “A Few Times” or “Many Times” were recoded as exposure to physical neglect and physical abuse.

2.2.3 Resilience

Resilience was assessed using the 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor and Davidson 2003; Campbell-Sills and Stein 2007). It is a unidimensional and self-administered scale that measures core attributes of resilience, including the ability to quickly “bounce back” in the face of stress or illness, focus under pressure, manage negative and painful affects, and problem solve (Campbell-Sills and Stein 2007). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not true at all” (0) to “true nearly all the time” (4). The total score ranged from 0–40, with higher scores suggesting higher resilience capacity. The composite reliability in current study was 0.82, with a 95% confidence interval (0.79, 0.84).

2.2.4 Depression

The Self-Reporting-Questionnaire (SRQ-20) developed by the World Health Organization for screening depression in low income settings was utilized (Beusenberg et al. 1994). Recently, it was validated among adults in the primary health care setting in Eritrea (Netsereab et al. 2018). College students reported if they had symptoms of depression (E.g. Do you feel unhappy? No = 0; Yes = 1). A composite score ranged from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more symptoms of depression.

2.3 Data Analysis

The completed questionnaires were entered into CSPro version 6.3.2 (census and survey processing system) software. Tetrachoric correlations, composite reliability, and structural equation modeling (SEM) were utilized using Mplus 8.0, whereas all other analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0. ACEs and depression were modeled as observed continuous variables, while resilience and subjective wellbeing were modeled as latent variables. A bootstrap sample of 1000 and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) tested the mediating effect. A series of indicators were used to evaluate the goodness of model fit, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Fit Index (TLI), chi-square to degrees-of-freedom ratio (χ2/df), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

3 Results

As shown in Table 1, the mean age of the participants was 19.69 ± 1.50 years (range 18–25), and 50.49% of the sample was male. The majority were Tigrigna in ethnicity (87.38%) and lived in urban settings before college (81.66%). Only 36.69% of respondents either or both parents graduated from college. 86.4% (438/507) of participants reported at least one category of childhood adversity. Table 1 summarizes the means and standard deviations of ACEs, depression, resilience, and subjective wellbeing.

Tetrachoric correlations between ACEs categories ranged from − 0.01 to 0.64, depression items from 0.06 to 0.63, see Tables 5 and 6. The bivariate correlations for the variables are displayed in Table 2. All correlation coefficients were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

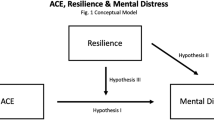

To test the hypothesized moderated mediation model, we first examined the overall effect of ACEs on subjective wellbeing (β = − 0.18, p < 0.001). Next, depression was considered as a mediator to investigate the relation between ACEs and subjective wellbeing. The finding showed that depression fully mediated the effect of ACEs on subjective wellbeing. Then, resilience was examined as a moderator, see Fig. 1. Results indicated that the interaction between resilience and ACEs regressed on depression (p = 0.606) and subjective wellbeing (p = 0.281) were non-significant.

Finally, we tested whether resilience mediates the effect of ACEs on subjective wellbeing. The direct link between ACEs and wellbeing became non-significant (β = − 0.01; p = 0.890), hence this path was eliminated from the final model for parsimony. Figure 2 depicts the final model, with standardized path coefficients adjusting for year of study, growing up with both parents, gender, ethnicity, setting of residence before college, and parental college education. The final model demonstrated a very good fit (χ2 = 393.736, df = 206, χ2/df < 3, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.06, and RMSEA = 0.04, 90% CI: 0.04–0.05), explaining 37.2% of the variance in wellbeing. ACEs were negatively associated with resilience (β = − 0.18, p < 0.001). In turn, resilience was correlated with lower depression (β = − 0.26, p < 0.001) and higher subjective wellbeing (β = 0.24, p < 0.001). ACEs had a positive association with depression (β = 0.22, p < 0.001), which in turn was negatively related to subjective wellbeing (β = − 0.49, p < 0.001), see Table 3.

As presented in Table 4, ACEs had significant indirect effects on subjective wellbeing through resilience (β = − 0.04, p = 0.006) and depression (β = − 0.11, p < 0.001). Resilience together with depression mediated the relationship between ACEs and subjective wellbeing (β = − 0.02, p = 0.005).

4 Discussion

This is the first study from Eritrea to report the effect of ACEs on the subjective wellbeing of college students. ACEs are estimated to be more prevalent in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) with a prevalence of 46% for violence, 52% for emotional maltreatment, and 43% for household dysfunction among adolescents (Blum et al. 2019). 86.40% of respondents reported at least one category of childhood adversity in the current study, which is higher as compared to university students from Tunisia (74.8%), Germany (23.0%) and South Korea (49.9%) (El Mhamdi et al. 2017; Wiehn et al. 2018; Kim 2017). In our study, the average ACE score was 2.70, also higher than similar studies in other countries like China (1.83), East Asia (1.51), and the Philippines (2.37) (Ho et al. 2019, 2020; Reyes et al. 2018).

Previous studies indicated that the subjective wellbeing of college students declines relative to its pre-college level. Though it improves gradually through the undergraduate years, it hardly returns to its previous level (Bewick et al. 2010; Sarmento 2015). This observation is expected to be pronounced among college students with depression or a history of ACEs (Sciolla et al. 2019).

Our data do not support the hypothesized moderated mediation model, with resilience as a moderator. Conversely, the current study showed that resilience, depression, and joint resilience-depression fully mediated the effects of ACEs on subjective wellbeing. Previous studies have reported a link between ACEs and negative mental health outcomes in universities around the world (Mall et al. 2018; Peng et al. 2012; Kalmakis et al. 2019; Robinson et al. 2019; Sokratous et al. 2013). For example, Karatekin and Hill (2018) found that college students with a history of high exposure to ACEs were far more likely to report depression. Another research also found that ACEs had cumulative effects on the subjective wellbeing of college students (Brogden and Gregory 2019). Research on developmental pathways from ACEs through depression (Merrick et al. 2017; LaNoue et al. 2012) further support our finding. The far reaching impact of ACEs can be explained by the indication that during childhood, when brain development is active, ACEs hyper-sensitize stress and emotion regulating brain circuitries such as the HPA, amygdala and the hippocampus (Herzog and Schmahl 2018). These potential neurobiological repercussions from ACEs and the prolonged toxic stress expose children to become highly sensitive, hyper-vigilant and over-reactive to threat stimuli later in life (Tottenham and Sheridan 2010; Teicher et al. 2016). Individuals with these behaviors will have problems regulating their emotions and building healthy interpersonal relationships, which negatively affect their wellbeing (Mc Elroy and Hevey 2014). Not only do ACEs alter neurobiological systems, they also dysregulate other epigenetic and psychosocial stress pathways that lead to lowered stress threshold and exhausted coping mechanisms (Shonkoff 2010; Nurius et al. 2015), which increase vulnerability to depression. These impacts might be visible during this transitional developmental period when young adults move towards independence and salient biological and psychosocial developmental changes occur. Therefore, it is high time to identify high-risk individuals and protective factors.

Compared to the contributions of other variables included in the model, depression exerted the strongest negative effect on subject wellbeing. Additionally, depression alone has mediated more proportion in the relationship than the joint depression-resilience and resilience. This is not a surprising finding inasmuch as several studies have indicated that depression exacerbates subjective wellbeing by several means, including the dominance of negative affect and reduction of positive affect (Cummins 2013), rumination (Sun et al. 2014), loss of hope (Mascaro and Rosen 2005), and increased activity of the HPA axis (Kalmakis et al. 2015).

Risk accumulation is another way ACEs sustain their enduring negative impact on wellbeing through depression. Experiencing one type of ACEs potentially increases the probability of being exposed to another (Garrido et al. 2018). In communities and families with multiple risks related to war, socio-economic, and political challenges, multiple stressors intermingle in a complex mechanism, exposing children to an array of adversities and subsequent psychopathology (Shonkoff et al. 2012). The absence of formal targeted mental health services in our setting may make these risks perpetuate. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and prevent ACEs as early as possible to prevent the accumulation of exposures. Recognizing and treating depression is also essential to prevent the sustained impact of ACEs on subjective wellbeing (Giovanelli et al. 2016). However, investing in the promotion of resilience and subjective wellbeing would be more acceptable than preventing negative mental health, as mental illness literacy is low and stigma is prevalent in this context. Despite the presence of mental illness, nurturing personal assets like psychological resilience helps sustain wellbeing (Bos et al. 2016). Evidence shows that mechanisms that promote positive mental health are effective and sustainable in reducing future mental ill-health (Keyes 2005).

Further, in line with studies among Eritrean youth (Melamed et al. 2019; Farwell 2003), resilience is negatively correlated with both ACEs and depression and positively with subjective wellbeing. Likewise, our results corroborate previous findings (Mehta et al. 2019; Tugade and Fredrickson 2004; Mak et al. 2011; Howell et al. 2017), in which resilience enhances wellbeing and reduces depressive symptoms through positive emotions and positive cognitive schemas. Several studies reiterated the substantial impact of resilience on wellbeing; people with higher resilience capacity are more tenacious when faced with adversity, handle stressful and threatening situations more positively, and have a higher capacity of coping with life’s challenges (Werner 2009; Luthar et al. 2015). Our result is also supported by Turner’s (Turner et al. 2017) finding, indicating resilience as a precursor to the wellbeing of university students. However, research conducted by Kaloeti et al. (2019) has shown that resilience did not mediate the effect of ACEs on depression among university students.

Our study recognizes the significant mediating role of resilience in the relationships between ACEs, depression, and subjective wellbeing, which implies that, though distant risks such as ACEs perpetrate enduring disruptions on subjective wellbeing, they can still be ameliorated by jointly enhancing wellbeing through building resilience and reducing depression (Peng et al. 2012). Our model’s joint risk and protective factor examination also align with the two continua model of mental health and psychological wellbeing (Kinderman et al. 2018).

5 Limitations

Several limitations should be mentioned in the current study. First, this study is prone to systematic bias as the sample consists only of college students; therefore, findings are not generalizable to other populations. Second, causal relationships could not be made from this cross-sectional study. Third, self-reports of study variables may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. Likewise, it is worth noting that the CD-RISC-10 measures only self-perceived individual attributes of resilience. Further, the magnitude of the relationship between ACEs, wellbeing, and resilience are significant but small. The contribution of variables on the explained variance of resilience and depression are very low, as several important constructs such as social supports (Jones et al. 2018) were not examined. Finally, caution should also be used in extrapolating the findings, allowing for sociocultural differences and the meaning ascribed to ACEs, resilience, depression, and subjective wellbeing in the local context.

6 Implications

This study presents potential practical implications. In accordance with the global call by the Sustainable Development Goals to reduce the life-course effects of ACEs on health (Hughes et al. 2017), our study underscores that school psychologists, counselors and other mental health professionals should consider ACEs as key risks to the wellbeing of young people in this particular context. In line with findings from similar war and post war settings, our study confirms that depression and prevalent multiple risks are key intervention targets to improve the wellbeing of youth (Okello et al. 2013). Hence, our research presents an insight into contextualized interventions that might offset the immediate harms of ACEs, protect against depression, and enhance subjective wellbeing. This may help youth to undergo successful transition to college and adulthood. It is particularly relevant to Eritrea, where mental health services are being decentralized and integrated into the primary health care system. For instance, trauma-informed programs could be integrated and streamlined into medical education and other existing primary health care programs. Colleges could be key partners in providing coordinated mental health services. Furthermore, recognizing the limited research on these significant risks in settings affected by political unrest (Kabiru et al. 2013; Akresh et al. 2012) and extensive stigma towards mental illness, our research has the potential to stimulate future studies. The literature on vulnerability in resource limited-settings largely focus on the deficits with little or no attention to assets that may promote the health and wellbeing of people. Investing and harnessing resilience may provide alternatives.

7 Conclusions

Our study further supports the notion that ACEs are prevalent in resource-limited settings and their negative mental health impacts are far-reaching. ACEs affect the subjective wellbeing of young adults emerging from war hardships indirectly via resilience, depression and joint resilience-depression pathways with depression playing a major role. Innovative and contextually suitable interventions targeting youth with history of ACEs may help mitigate the cycle of risk proliferation.

References

Agaibi, C. E., & Wilson, J. P. (2005). Trauma, PTSD, and resilience: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse, 6(3), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005277438.

Akresh, R., Lucchetti, L., & Thirumurthy, H. (2012). Wars and child health: evidence from the Eritrean-Ethiopian conflict. Journal of Development Economics, 99(2), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.04.001.

Alonso, J., Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Bruffaerts, R., Vilagut, G., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). Severe role impairment associated with mental disorders: results of the WHO world mental health surveys international college student project. Depression and Anxiety, 35(9), 802–814. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22778.

Arnett, J. J. (2012). New horizons in research on emerging and young adulthood. In A. Booth, S. L. Brown, N. S. Landale, W. D. Manning, & S. M. McHale (Eds.), early adulthood in a family context (pp. 231–244). New York: Springer.

Atilola, O. (2015). Level of community mental health literacy in sub-Saharan Africa: current studies are limited in number, scope, spread, and cognizance of cultural nuances. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 69(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2014.947319.

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). World mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362.

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Jones, A., Perkins, C., & McHale, P. (2013). Childhood happiness and violence: a retrospective study of their impacts on adult well-being. BMJ Open, 3(9), e003427. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003427.

Beusenberg, M., Orley, J. H., & World Health Organization, Division of Mental, H. (1994). A User's guide to the self reporting questionnaire. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students' psychological well-being as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643.

Blum, R. W., Li, M., & Naranjo-Rivera, G. (2019). Measuring adverse child experiences among young adolescents globally: relationships with depressive symptoms and violence perpetration. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(1), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.020.

Bos, E. H., Snippe, E., de Jonge, P., & Jeronimus, B. F. (2016). Preserving subjective wellbeing in the face of psychopathology: buffering effects of personal strengths and resources. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0150867. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150867.

Brogden, L., & Gregory, D. E. (2019). Resilience in community college students with adverse childhood experiences. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 43(2), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2017.1418685.

Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20271.

Castillo, L. G., & Schwartz, S. J. (2013). Introduction to the special issue on college student mental health. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21972.

Chapman, D. P., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Edwards, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013.

Chen, C. (2016). The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among chinese university students. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(3), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5.

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113.

Corcoran, M., & McNulty, M. (2017). Examining the role of attachment in the relationship between childhood adversity, psychological distress and subjective well-being. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.012.

Cummins, R. A. (2013). Subjective well-being, homeostatically protected mood and depression: a synthesis. In A. Delle Fave (Ed.), The exploration of happiness: present and future perspectives (pp. 77–95). Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer.

Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(4), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9000-y.

Diener, E., Pressman, S. D., Hunter, J., & Delgadillo-Chase, D. (2017). If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 9(2), 133–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12090.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6.

Ding, H., Han, J., Zhang, M., Wang, K., Gong, J., & Yang, S. (2017). Moderating and mediating effects of resilience between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in Chinese children. Journal of Affective Disorders, 211, 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.056.

Dutcher, J. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). The role of brain reward pathways in stress resilience and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 95, 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.014.

Eisenberg, D., Lipson, S. K., & Posselt, J. (2016). Promoting resilience, retention, and mental health. New Directions for Student Services, 2016(156), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20194.

El Mhamdi, S., Lemieux, A., Bouanene, I., Ben Salah, A., Nakajima, M., Ben Salem, K., et al. (2017). Gender differences in adverse childhood experiences, collective violence, and the risk for addictive behaviors among university students in Tunisia. Preventive Medicine, 99, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.02.011.

Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2019). Viewpoint: WHO world mental health surveys international college student initiative: implementation issues in low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(2), e1756. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1756.

Farwell, N. (2003). In war’s wake: contextualizing trauma experiences and psychosocial well-being among Eritrean youth. International Journal of Mental Health, 32(4), 20–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2003.11449596.

Felitti, V., & Anda, R. (2009). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult medical disease, psychiatric disorders, and sexual behavior: implications for healthcare. In R. Lanius, E. Vermetten, & C. Pain (Eds.), The impact of early life trauma on health and disease: the hidden epidemic (pp. 77–87). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511777042.010.

Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2003). Resilience to childhood adversity: results of a 21-year study. In S. S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and vulnerability: adaptation in the context of childhood adversities (pp. 130–155). United Kingdom: Cambrige University Press.

Fossion, P., Leys, C., Kempenaers, C., Braun, S., Verbanck, P., & Linkowski, P. (2013). Depression, anxiety and loss of resilience after multiple traumas: an illustration of a mediated moderation model of sensitization in a group of children who survived the Nazi Holocaust. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(3), 973–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.018.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431.

Garrido, E. F., Weiler, L. M., & Taussig, H. N. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and health-risk behaviors in vulnerable early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(5), 661–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616687671.

Giovanelli, A., Reynolds, A. J., Mondi, C. F., & Ou, S. R. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and adult well-being in a low-income, urban cohort. Pediatrics, 137(4), e20154016. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4016.

Graf, S. (2018). Politics of belonging and the Eritrean diaspora youth: generational transmission of the decisive past. Geoforum, 92, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.04.009.

Gray, P. (2015). Declining student resilience: a serious problem for colleges. Retrieved 30 May 2019 from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/freedom-learn/201509/declining-student-resilienceserious-problem-colleges.

Guo, L., Huang, Y., Xu, Y., Huang, G., Gao, X., Lei, Y., et al. (2018). The mediating effects of depressive symptoms on the association of childhood maltreatment with non-medical use of prescription drugs. Journal of Affect Disorders, 229, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.029.

Hartley, M. T. (2011). Examining the relationships between resilience, mental health, and academic persistence in undergraduate college students. Journal of American College Health, 59(7), 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.515632.

Hartley, M. T. (2012). Assessing and promoting resilience: an additional tool to address the increasing number of college students with psychological problems. College Counseling, 15(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00004.x.

Herzog, J. I., & Schmahl, C. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420.

Ho, G. W. K., Chan, A. C. Y., Chien, W. T., Bressington, D. T., & Karatzias, T. (2019). Examining patterns of adversity in Chinese young adults using the adverse childhood experiences-international questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.009.

Ho, G. W. K., Bressington, D., Karatzias, T., Chien, W. T., Inoue, S., Yang, P. J., et al. (2020). Patterns of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and their associations with mental health: a survey of 1346 university students in East Asia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(3), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01768-w.

Hochberg, G., Pucheu, S., Kleinebreil, L., Halimi, S., & Fructuoso-Voisin, C. (2012). WHO-5, a tool focusing on psychological needs in patients with diabetes: The French contribution to the DAWN study. Diabetes & Metabolism, 38(6), 515–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2012.06.002.

Holdsworth, S., Turner, M., & Scott-Young, C. M. (2018). Not drowning, waving. Resilience and university: a student perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1837–1853. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1284193.

Hong, F., Tarullo, A. R., Mercurio, A. E., Liu, S., Cai, Q., & Malley-Morrison, K. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and perceived stress in young adults: the role of emotion regulation strategies, self-efficacy, and resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.014.

Hoppen, T. H., & Chalder, T. (2018). Childhood adversity as a transdiagnostic risk factor for affective disorders in adulthood: a systematic review focusing on biopsychosocial moderating and mediating variables. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 81–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.002.

Howell, K. H., Miller-Graff, L. E., Schaefer, L. M., & Scrafford, K. E. (2020). Relational resilience as a potential mediator between adverse childhood experiences and prenatal depression. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(4), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317723450.

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., et al. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30118-4.

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C. E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(3), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015.

Johnson, M. L., Taasoobshirazi, G., Kestler, J. L., & Cordova, J. R. (2015). Models and messengers of resilience: a theoretical model of college students’ resilience, regulatory strategy use, and academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 35(7), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.893560.

Jones, T. M., Nurius, P., Song, C., & Fleming, C. M. (2018). Modeling life course pathways from adverse childhood experiences to adult mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.005.

Kabiru, C. W., Izugbara, C. O., & Beguy, D. J. B. (2013). The health and wellbeing of young people in sub-Saharan Africa: an under-researched area? BMC International Health and Human Rights, 13(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-13-11.

Kalmakis, K. A., Meyer, J. S., Chiodo, L., & Leung, K. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and chronic hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal activity. Stress, 18(4), 446–450. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2015.1023791.

Kalmakis, K. A., Chiodo, L. M., Kent, N., & Meyer, J. S. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and self-reported stress among traditional and nontraditional college students. Journal of American College Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1577860.

Kaloeti, D. V. S., Rahmandani, A., Sakti, H., Salma, S., Suparno, S., & Hanafi, S. (2019). Effect of childhood adversity experiences, psychological distress, and resilience on depressive symptoms among Indonesian university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(2), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1485584.

Karatekin, C., & Hill, M. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences as a predictor of attendance at a health-promotion program. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318802929.

Karatzias, T., Jowett, S., Yan, E., Raeside, R., & Howard, R. (2017). Depression and resilience mediate the relationship between traumatic life events and ill physical health: results from a population study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(9), 1021–1031. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1257814.

Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., et al. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499.

Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539.

Kim, Y. H. (2017). Associations of adverse childhood experiences with depression and alcohol abuse among Korean college students. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 338–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.009.

Kinderman, P., Tai, S., Pontin, E., Schwannauer, M., Jarman, I., & Lisboa, P. (2018). Causal and mediating factors for anxiety, depression and well-being. British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(6), 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147553.

Koss, K. J., & Gunnar, M. R. (2018). Annual research review: early adversity, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis, and child psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12784.

LaNoue, M., Graeber, D., de Hernandez, B. U., Warner, T. D., & Helitzer, D. L. (2012). Direct and indirect effects of childhood adversity on adult depression. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(2), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9369-2.

Liang, L., Yang, Y., & Xiao, Q. (2018). Young people with left-behind experiences in childhood have higher levels of psychological resilience. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318801056.

Lu, C., Yuan, L., Lin, W., Zhou, Y., & Pan, S. (2017). Depression and resilience mediates the effect of family function on quality of life of the elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 71, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.02.011.

Luthar, S. S., Lyman, E. L., & Crossman, E. J. (2014). Resilience and positive psychology. In M. Lewis & K. D. Rudolph (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 125–140). Boston, MA: Springer.

Luthar, S. S., Crossman, E. J., & Small, P. J. (2015). Resilience and adversity. In R. M. Lerner & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (7th ed., pp. 1–40). New York: Wiley.

Mak, W. W., Ng, I. S., & Wong, C. C. (2011). Resilience: enhancing well-being through the positive cognitive triad. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025195.

Mall, S., Mortier, P., Taljaard, L., Roos, J., Stein, D. J., & Lochner, C. (2018). The relationship between childhood adversity, recent stressors, and depression in college students attending a South African university. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1583-9.

Marriner, P., Caciolli, J., & Moore, K. (2014). The relationship of attachment to resilience and their impact on perceived stress. In K. Kaniasty, K. A. Moore, S. Howard, & P. Buchwald (Eds.), Stress and anxiety: applications to social and environmental threats, psychological well-being, occupational challenges and developmental psychology (pp. 73–82). Germany: Logos Verlag.

Mascaro, N., & Rosen, D. H. (2005). Existential meaning's role in the enhancement of hope and prevention of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 985–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00336.x.

Masten, A. S., Burt, K. B., Roisman, G. I., ObradoviĆ, J., Long, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404040143.

Masten, A. S., Obradović, J., & Burt, K. B. (2006). Resilience in emerging adulthood: developmental perspectives on continuity and transformation. Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 173–190). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Mc Elroy, S., & Hevey, D. (2014). Relationship between adverse early experiences, stressors, psychosocial resources and wellbeing. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.017.

McLafferty, M., Bunting, B. P., Armour, C., Lapsley, C., Ennis, E., Murray, E., et al. (2020). The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies on psychopathology and suicidal behaviour following negative childhood experiences. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105212.

Mehta, M. H., Grover, R. L., DiDonato, T. E., & Kirkhart, M. W. (2019). Examining the positive cognitive triad: a link between resilience and well-being. Psychological Reports, 122(3), 776–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118773722.

Melamed, S., Chernet, A., Labhardt, N. D., Probst-Hensch, N., & Pfeiffer, C. (2019). Social resilience and mental health among Eritrean asylum-seekers in Switzerland. Qualitative Health Research, 29(2), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318800004.

Mello, J. (2016). Life adversity, social support, resilience, and college student mental health. All Master's Theses, p. 347.

Meng, X., Fleury, M. J., Xiang, Y. T., Li, M., & D'Arcy, C. (2018). Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: a systematic review. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(5), 453–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1485-2.

Merrick, M. T., Ports, K. A., Ford, D. C., Afifi, T. O., Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2017). Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016.

Migliorini, C., Callaway, L., & New, P. (2013). Preliminary investigation into subjective well-being, mental health, resilience, and spinal cord injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 36(6), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000100.

Min, J. A., Jung, Y. E., Kim, D. J., Yim, H. W., Kim, J. J., Kim, T. S., et al. (2013). Characteristics associated with low resilience in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders. Quality of Life Research, 22(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0153-3.

Mokdad, A. H., Forouzanfar, M. H., Daoud, F., Mokdad, A. A., El Bcheraoui, C., Moradi-Lakeh, M., et al. (2016). Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people's health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet, 387(10036), 2383–2401. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00648-6.

Mosley-Johnson, E., Garacci, E., Wagner, N., Mendez, C., Williams, J. S., & Egede, L. E. (2019). Assessing the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and social well-being: United States Longitudinal Cohort 1995–2014. Quality of Life Research, 28(4), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2054-6.

Netsereab, T. B., Kifle, M. M., Tesfagiorgis, R. B., Habteab, S. G., Weldeabzgi, Y. K., & Tesfamariam, O. Z. (2018). Validation of the WHO self-reporting questionnaire-20 (SRQ-20) item in primary health care settings in Eritrea. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0242-y.

Newcomb-Anjo, S. E., Barker, E. T., & Howard, A. L. (2017). A person-centered analysis of risk factors that compromise wellbeing in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 867–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0603-2.

Ngamaba, K. H., Panagioti, M., & Armitage, C. J. (2017). How strongly related are health status and subjective well-being? Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 27(5), 879–885. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx081.

Nurius, P. S., Logan-Greene, P., & Green, S. (2012). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) within a social disadvantage framework: distinguishing unique, cumulative, and moderated contributions to adult mental health. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 40(4), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2012.707443.

Nurius, P. S., Green, S., Logan-Greene, P., & Borja, S. (2015). Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: a stress process analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008.

Oehme, K., Perko, A., Clark, J., Ray, E. C., Arpan, L., & Bradley, L. (2019). A trauma-informed approach to building college students’ resilience. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2018.1533503.

Okello, J., Nakimuli-Mpungu, E., Musisi, S., Broekaert, E., & Derluyn, I. (2013). War-related trauma exposure and multiple risk behaviors among school-going adolescents in Northern Uganda: the mediating role of depression symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(2), 715–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.030.

Oshio, T., Umeda, M., & Kawakami, N. (2013). Childhood adversity and adulthood subjective well-being: evidence from Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 843–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9358-y.

Payne, J. D., Jackson, E. D., Hoscheidt, S., Ryan, L., Jacobs, W. J., & Nadel, L. (2007). Stress administered prior to encoding impairs neutral but enhances emotional long-term episodic memories. Learning & Memory, 14(12), 861–868. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.743507.

Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: an integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 214(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2009-2.

Peng, L., Zhang, J., Li, M., Li, P., Zhang, Y., Zuo, X., et al. (2012). Negative life events and mental health of Chinese medical students: the effect of resilience, personality and social support. Psychiatry Research, 196(1), 138–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.006.

Pizzagalli, D. A., Iosifescu, D., Hallett, L. A., Ratner, K. G., & Fava, M. (2008). Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: evidence from a probabilistic reward task. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.001.

Plastow, J. (2007). Finding children's voices: a pilot project using performance to discuss attitudes to education among primary school children in two Eritrean villages. Research in Drama Education, 12(3), 345–354.

Poole, J. C., Dobson, K. S., & Pusch, D. (2017). Childhood adversity and adult depression: the protective role of psychological resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 64, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.012.

Ratanasiripong, P., China, T., & Toyama, S. (2018). Mental health and well-being of university students in Okinawa. Education Research International, 2018, 7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4231836.

Reyes, M. E., Buac, K. M., Dumaguing, L. I., Lapidez, E. D., Pangilinan, C. A., Sy, W. P., et al. (2018). Link between adverse childhood experiences and five factor model traits among Filipinos. IAFOR Journal of Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences, 4(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.22492/ijpbs.4.2.06.

Robinson, M., Ross, J., Fletcher, S., Burns, C. R., Lagdon, S., & Armour, C. (2019). The mediating role of distress tolerance in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental health outcomes among university students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519835002.

Sagone, E., & De Caroli, M. E. (2014). Relationships between psychological well-being and resilience in middle and late adolescents. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 141, 881–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.154.

Sarmento, M. (2015). A “mental health profile” of higher education students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.606.

Satici, S. A. (2016). Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: the mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.057.

Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1991). Evaluating one's life: A judgment model of subjective well-being. Subjective well-being: an interdisciplinary perspective. (International series in experimental social psychology) (Vol. 21, pp. 27–47). Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

Sciolla, A. F., Wilkes, M. S., & Griffin, E. J. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences in medical students: implications for wellness. Academic Psychiatry, 43(4), 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01047-5.

Scott, K. M., Von Korff, M., Angermeyer, M. C., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., de Girolamo, G., et al. (2011). Association of childhood adversities and early-onset mental disorders with adult-onset chronic physical conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(8), 838–844. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.77.

Shapero, B. G., Farabaugh, A., Terechina, O., DeCross, S., Cheung, J. C., Fava, M., et al. (2019). Understanding the effects of emotional reactivity on depression and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: Moderating effects of childhood adversity and resilience. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.033.

Shonkoff, J. P. (2010). Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Development, 81(1), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01399.x.

Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301(21), 2252–2259. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.754.

Shonkoff, J. P., Richter, L., van der Gaag, J., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2012). An integrated scientific framework for child survival and early childhood development. Pediatrics, 129(2), e460–e472. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0366.

Smith, N. B., Monteith, L. L., Rozek, D. C., & Meuret, A. E. (2018). Childhood abuse, the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide, and the mediating role of depression. Suicide Life Threatening Behavior, 48(5), 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12380.

Sokratous, S., Merkouris, A., Middleton, N., & Karanikola, M. (2013). The association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms among Cypriot university students: a cross-sectional descriptive correlational study. BMC Public Health, 13, 1121. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1121.

Solakoglu, O., Driver, N., & Belshaw, S. H. (2018). The effect of sexual abuse on deviant behaviors among Turkish adolescents: the mediating role of emotions. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(1), 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x16642810.

Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (2012). The science of resilience: implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science, 338(6103), 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222942.

Sun, H., Tan, Q., Fan, G., & Tsui, Q. (2014). Different effects of rumination on depression: key role of hope. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-53.

Teicher, M. H., Samson, J. A., Anderson, C. M., & Ohashi, K. (2016). The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(10), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.111.

Terhune, C. (1997). Cultural and religious defenses to child abuse and neglect. Journal of American Academy of Matrimonial Lawers, 14, 152.

Theron, L. C., & Theron, A. M. C. (2014). Education services and resilience processes: resilient black South African students' experiences. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.10.003.

Tottenham, N., & Sheridan, M. A. (2010). A review of adversity, the amygdala and the hippocampus: a consideration of developmental timing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3, 68. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.068.2009.

Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal Personality Social Psycholology, 86(2), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320.

Turner, M., Scott-Young, C. M., & Holdsworth, S. (2017). Promoting wellbeing at university: the role of resilience for students of the built environment. Construction Management and Economics, 35(11–12), 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2017.1353698.

Vik, M. H., & Carlquist, E. (2018). Measuring subjective well-being for policy purposes: the example of well-being indicators in the WHO "Health 2020" framework. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(2), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817724952.

Víllora, B., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., Alfaro, A., & Navarro, R. (2020). Relations among poly-bullying victimization, subjective well-being and resilience in a Sample of late adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 590.

Werner, E. E. (1989). High-risk children in toung adulthood: a longitudinal study from birth to 32 years. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01636.x.

Werner, E. E. (2009). Risk, resilience, and recovery: perspectives from the kauai longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940000612X.

WHO (1998). Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the depcare project. Retrieve 6 May 2019 from https://www.corc.uk.net/outcome-experience-measures/the-world-health-organisation-five-well-being-index-who-5/.

WHO (2018). Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire. In adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Retrieve 6 May 2019 from https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_expe.

Wiehn, J., Hornberg, C., & Fischer, F. (2018). How adverse childhood experiences relate to single and multiple health risk behaviours in German public university students: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1005. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5926-3.

Yehuda, R., & Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20568.

Youssef, N. A., Belew, D., Hao, G., Wang, X., Treiber, F. A., Stefanek, M., et al. (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in the association of childhood adversities with depression and the role of resilience. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelifa, M.O., Yang, Y., Carly, H. et al. How Adverse Childhood Experiences Relate to Subjective Wellbeing in College Students: The Role of Resilience and Depression. J Happiness Stud 22, 2103–2123 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00308-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00308-7