Abstract

This study’s primary purpose was to examine the hypothesis that there would be a positive association between acculturation and life satisfaction for English-speaking diaspora immigrants to Israel regardless of country of origin (after adjusting for demographic characteristics including gender, age, years in the host country, reason for immigration and family support). Informed by Bornstein’s Specificity Principle in Acculturation Science, acculturation was defined by levels of: language acquisition, having realised/met expectations, and self-identification with host country. Using a cross-sectional study design, a convenience sample of English-speaking participants was recruited through a link on a well-known English-language internet site targeting immigrants to Israel. Due to the diversity of respondents, only questionnaires completed by immigrants from the following four countries were included (n = 641): Canada (n = 40), South Africa (n = 66), the United Kingdom (n = 132) and the United States (n = 403). Life satisfaction only was linked to the acculturation variable of having a higher level of realised expectations for life after immigration and reporting good health, but not associated with the other acculturation variables of language acquisition or self-identification with host country. While having realised expectations was related to life satisfaction, the number of years in the host country and language acquisition was not. Having realistic expectations (related to greater life satisfaction) may be increased by providing prospective immigrants information on the new country’s culture while they are still in the host country and planning their immigration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2015, approximately 244 million migrants arrived at primarily high-income countries (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division 2016). Within this homogeneous group of migrants are diaspora immigrants (defined as immigrants moving primarily because they feel a sense of belonging to a specific country due to its social characteristics, culture or religion) (Gamlen 2008; Motti-Stefanidi et al. 2008). Consequently, the measurement of life satisfaction for diaspora immigrants has been based primarily on sociocultural features related to belongingness including social connections (Mahonen et al. 2013), cultural identity (Stoessel et al. 2014) and religious affiliation (Amit and Bar-Lev 2015).

Diaspora is a complicated phenomenon centred on an amorphous collection of cultural, geographic, national, social and political attributes (see discussion in (Brubaker 2009)). Less than a decade ago, more than 60 countries were communicating or assisting their populations in diaspora (Gamlen 2008). This paper focuses on diaspora immigrants to Israel.

1.1 Diaspora Immigrants and Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction, an aspect of subjective well-being (Diener et al. 2013), is associated with income (Diener et al. 2010). At the country-level, populations from higher, compared to lower, income countries tend to have higher levels of life satisfaction; and the rank of countries based on income level tends to remain stable in the worldwide context (Eksi and Kaya 2017). These country-level effects of life satisfaction may emanate from country culture; but if so, how does life satisfaction of immigrants compare with those of native-born populations? In answer to this question, Hajdu and Hajdu (2016) found that immigrants who were born in a country where the general population had higher levels of life satisfaction, tended to have similarly higher levels of life satisfaction in their new countries post-immigration, even after controlling for known confounders such as income status (Hajdu and Hajdu 2016). Two variables of acculturation also had a strong impact on retaining the birth country’s level of life satisfaction: immigrating as adults versus as children, and preference of speaking the birth country’s language (rather than the host country’s) (Hajdu and Hajdu 2016).

These findings are consistent with Berry’s model of acculturation strategies in multicultural societies (Berry 1997), which suggests that life satisfaction is related to the manner and extent that immigrants adjust and adapt their values, identity, and behaviours to those of the dominant host society (Berry 2005). Acculturation acknowledges the forces between the dominant host society and the minority immigrant culture, as well as levels of adaptation and strategies used by the minority immigrant culture to fit the dominant society (Berry 2005; Berry et al. 2006). Yet, theoretical arguments assert that influences of the dominant host society on immigrants differ based on the immigrants’ country and culture of origin (Bourhis et al. 1997). The Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM) suggests that acculturation is not a monolithic construct, but rather consists of seven spheres or components to which minority immigrants seek to adapt (Navas et al. 2007). Some of these arise from the socioeconomic environmental constructs such as politics, work and economics, but others are symbolic such as ideology and religion, or refer to relationships such as those with family and friends. This theoretical extension of Berry’s Model of Acculturation is incorporated within Bornstein’s Specificity Principle in Acculturation Science (BSPAS); its components of setting (including reasons to migrate, country of origin), person, time, process, and domain provide a theoretical approach to understanding diaspora immigrants (Bornstein 2017).

The concept of culture and ideology from RAEM (Navas et al. 2007) and that of setting (including reasons to migrate and country of origin) from BSPAS (Bornstein 2017) fit diaspora immigrants’ motivation to leave their country of origin and immigrate to a country where the culture, ideology and religion are expected to be like their own. Yet, even if diaspora immigrants view the culture or religion akin to their own, the country of origin may have different social mores, physical environments, and lifestyles, including behaviours, expressions of emotion, familial relationships, and parenting practices.

Bornstein’s component of person includes demographic characteristics unique to the immigrant (e.g., gender, marital status, education level, income, health). Although many demographic characteristics are linked to acculturation, the health status of immigrants has garnered substantial interest due to disparities compared to native-born individuals (Brzoska et al. 2015). Poor health has an impact on the ability to socialise, work and participate in society. Yet, the ages of diaspora immigrants vary; some are retirement age, and some bring older family members with them (Lowenstein and Katz 2005). Older individuals, compared to younger ones, are more likely to have poorer health. Additionally, living in three-generation households may influence both family dynamics and the ability of family members to integrate into the society (Lowenstein and Katz 2005).

BSPAS’ third component of time refers to age, adjustment to the new culture including self-identification, and having met or realised expectations after immigration. Dual identity has been noted as an important characteristic linked to acculturation for all immigrants (Berry 2005; Berry and Sabatier 2011), including diaspora immigrants (Amit and Bar-Lev 2015). Far fewer studies have focused on having realised expectations. In a single study on Finnish diaspora immigrants, having realised expectations with social connections is associated with life satisfaction over time (Mahonen et al. 2013). This study suggests that there may be a link between at least one acculturation characteristic, realised expectations, on quality of life and life satisfaction, but other acculturation characteristics were not included. Moreover, the construct of acculturation expectation profiles tended to be applied to autochthonous populations based on their realised expectations, national identity, ethnic and national social contacts with peers (Inguglia and Musso 2015); this pattern is very likely mirrored in many immigrant populations. Moreover, remote acculturation (across distance) bringing geographically and historically separate groups of people into meaningful contact (such as is the case of diaspora immigrants) (Ward and Geeraert 2016) has an impact on realised expectations post-immigration. Recent research concerning acculturation expectations of minority members also emphasises the role of their identity (Kunst et al. 2016). Diaspora immigrants usually are ideologically oriented to strive for a bicultural identification (Oppenheim-Weller and Kurman 2017). According to Tartakovsky (2011), the anticipatory pre-migration system of national identities reflects the immigrants’ high positive expectations regarding the host country. In his view, it is possible that prior to migration, immigrants form their system of social identities based on high expectations, but after their arrival to the host country, they change their system of social identities in reaction to the difficulties of acculturation (Tartakovsky 2011).

Process, the fourth BSPAS component, is operationalised by rating evidence of socialisation such as language acquisition, an important variable associated with life satisfaction in some samples of diaspora immigrants (Amit and Bar-Lev 2015). However, language acquisition may depend on the immigrants’ country of origin and native language. Diaspora immigrants who are native English-speakers and arriving as adults do not learn the country’s official language as quickly as those with other native languages (e.g., Spanish, French), possibly due to the ability of English-speakers to find needed resources in their own language (Raijman et al. 2015). This potential explanation supports BSPAS’ final component called domain, a dynamic and complex component that is similar to the bioecological theory in that all aforementioned components interact with one another. Thus, emigrating from a native English-speaking country may contribute to acculturation and life satisfaction for those who move to areas where they use English and feel no need to learn the native language. Conversely, life satisfaction may be decreased among native English-speakers who are surprised to find that not being proficient in their native language may influence their ability to find work or socialise, which in turn may decreased levels of life satisfaction. The influences of these factors are not solely independent as suggested by BSPAS’ domain. Consequently, life satisfaction may be stronger or weaker among immigrants depending on the specific English-speaking country. This topic has not yet been examined.

1.2 Case of Israel

“Immigration of Jews from all over the world to Israel has been one of the main goals and core values of the state from the beginning of its existence” (Amir et al. 1999) (p. 713). As an immigrant-receiving country, Israel has a long history of developing policies aimed at facilitating integration including offering five months of free language classes (called ulpan), a small housing allowance, and for some, job assistance. Between the years 2000 to 2015, most Israeli immigrants came from countries of the former Soviet Union (FSU), but others came from English-speaking countries (CBS-Central Bureau of Statistics-Israel 2016).

Although both Russian- and English-speaking diaspora immigrants are coming to Israel, based on Bornstein’s theory components of person (i.e., demographic characteristics including socioeconomic status and work), setting (i.e., reasons for immigration and characteristics of the country of origin) and domain (i.e., the combined and interacting effects of all BPSAS factors including person and setting), the two groups are potentially very different. For example, currently approximately 15% of Israel’s population is comprised of Russian-speakers, many of whom were among the more than 800,000 Russian-speaking immigrants who came to Israel between 1989 and 1992 after the collapse of the former Soviet Union (Goldner et al. 2015). Thus, Bornstein’s component of setting for the Russian-speaking population is quite unique.

Early studies describing Russian-speaking immigrants in Israel noted that acculturation was difficult and life satisfaction low as many Russian-speaking immigrants found that their academic degrees and work experiences were unrecognized in Israel; and as a result, they had difficulty obtaining professional positions in Israel that were comparable to those they held in their country of origin (Cohen and Kogan 2007; Khvorostianov and Remennick 2015; Remennick 2002). Some acculturation studies focused on the Russian-speaking immigrants’ self-identity that included coming from the FSU (Benish-Weisman and Horenczyk 2010; Iarmolenko et al. 2016; Lissitsa and Peres 2011; Remennick 2002) and socializing primarily with other immigrants who speak Russian (Benish-Weisman and Horenczyk 2010; Iarmolenko et al. 2016; Lissitsa and Peres 2011; Remennick 2002). Thus, Bornstein’s component of person also was quite distinctive among Israel’s Russian-speaking immigrants. Additionally, it is important to note that a substantial body of literature on Russian-speaking immigrants to Israel has amassed in the past 20 years due to their enormous numbers and unique history.

In sharp contrast to the Russian-speaking immigrants, immigrants from English-speaking countries comprise a mere fraction of the Israeli population: between the years of 2000–2015 7122 from the United Kingdom (UK), 30,134 from the United States (USA), 3334 from Canada, and 3195 from South Africa (SA) (CBS-Central Bureau of Statistics-Israel 2016). Researchers found that English-speaking immigrants compared to Russian-speaking immigrants in Israel had better language proficiency in Hebrew (although lower than French- and Spanish-speaking immigrants), which might be the result of the large Russian-speaking community in Israel (Raijman et al. 2015). English-speaking, compared to Russian-speaking, immigrants in Israel also had higher incomes (Raijman et al. 2015). Among immigrant groups, English-speaking immigrants’ academic degrees and work experience were more likely to be recognized; and employment opportunities at international companies and academic institutions were more likely as they needed employees with English-language fluency (Raijman et al. 2015). Unlike studies on Russian-speaking immigrants, studies on English-speaking immigrants in Israel frequently measured the variable of contemplating return to their country of origin as this alternative was a back-up plan for many English-speaking immigrants if the acculturation did not meet their expectations (Amit and Bar-Lev 2015; Amit and Riss 2014). Thus, Russian-speaking immigrants and English-speaking immigrants differ by BSPAS person, setting and domain, three important factors influencing acculturation, and possibly, life satisfaction. However, while many studies have examined Russian-speaking immigrants, relatively few studies have focused on English-speaking immigrants.

1.3 Current Study

Past studies have not specified whether native-language English contributes to acculturation and life satisfaction, or perhaps, the contributing factor is the specific country of origin. Moreover, as BSPAS suggests, there are layers of life satisfaction as an immigrant, including demographic characteristics, reasons for immigration, country of origin, family support, and acculturation variables including language acquisition, dual national identity and realised expectations. Consequently, the hypothesis of this study is that there will be a positive association between acculturation and life satisfaction for English-speaking immigrants regardless of country of origin (after adjusting for demographic characteristics including gender, age, years in the host country, reason for immigration and family support).

2 Methods

2.1 Population and Study Design

This cross-sectional study targeted English-speaking immigrants living in Israel from Canada, South Africa (SA), the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (USA). A convenience sample was recruited through online sources (e.g., Facebook groups, listservs), newsletters, and word-of-mouth to answer a three-page, mostly structured, anonymous questionnaire available through a link on a well-known website (called Anglo-List) targeting English-speaking immigrants and expatriates in Israel. Upon entry to the website, the prospective participants were provided with the study description and intent. Following this information, the website requested and required participants to electronically provide informed consent before proceeding to the questionnaire. At the culmination of the questionnaire, participants could opt to provide their names and emails to participate in a lottery with a prize of a 500-shekel (approximately $137) gift-certificate. Identifying data for the lottery were placed in a separate database unlinked to the questionnaire data to preserve participants’ anonymity. Data collection proceeded for approximately a two-week period, 950 questionnaires were begun, but only 729 were completed (76.7% response rate). The study was approved by the University of Haifa Ethics’ Committee (authorisation protocol number: 208/17).

2.2 Instrument

The three-page questionnaire contained 51 questions on demographic characteristics (e.g., birthdate, gender, marital status, country of birth, date of immigration, monthly income), reasons for immigration, family support (e.g., immigrated with family, had family already in Israel), and three scales. Three scales used in this study were: the valid and reliable Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al. 1985), and two other scales on language ability and realised expectations developed specifically for this study.

2.2.1 Life Satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a reliable and validated scale comprised of five statements and a seven-level rating; the total score, ranging from 5 to 35, is tallied by summing the score from all five statements (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = slightly disagree, 4 = neither agree nor disagree, 5 = slightly agree, 6 = agree, 7 = strongly agree) (Diener et al. 1985). The scale originators tested it on different adult populations and achieved high factor loadings and good internal consistency (Diener et al. 1985). Since then, other studies have used the SWLS and found good internal consistency with varied populations including native and immigrant adult populations (Lin et al. 2015), persons with post spinal cord injury (Dijkers 1999), and immigrant students (Vela and Lerma 2017). The Hebrew version of the SWLS was tested and achieved high levels of reliability and validity (Anaby et al. 2010). Moreover, the SWLS consistently demonstrated measurement of a single construct of subjective well-being by immigrant respondents from several different countries living in Israel (Ponizovsky et al. 2013). In this study, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was very good to excellent for the total sample 0.90; and 0.88, 0.91, 0.92, and 0.88 for Canada, South Africa, the UK, and the USA, respectively.

2.2.2 Immigrants’ Language Ability (ILA)

This scale was comprised of three items found in other scales measuring language proficiency and acquisition (Adamuti-Trache 2012; Marian et al. 2007). Other scales contained items that demonstrated the importance of everyday communication, both written and verbal, and included many details on language acquisition, such as: accent, exposure to fellow immigrants and native-born individuals, prior language education, comfort in speaking and writing, and preferences in speaking or writing. Due to restrictions in the study questionnaire’s length, we chose to include only the following three questions: (1) How would you rank your ability to speak Hebrew in everyday situations?; (2) How would you rank your ability to read Hebrew in everyday situations?; and (3) At work or when dealing with Israeli bureaucracy, how would your rank your ability to speak in Hebrew? Respondents rated each question according to a five-level rating (poor to non-existent, adequate, good, very good, like a native-born). Total score was tabulated by summing the three responses: poor to non-existent = 0, adequate = 1, good = 2, very good = 3, and like a native-born = 4; thus, scores ranged from 0 to 12. Internal consistency of this three-item scale was excellent with a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95 for the total sample, and 0.90, 0.91, 0.96, 0.95 for Canada, South Africa, the UK, and the USA, respectively.

2.2.3 Realised Expectations of Acclimating to Life After Immigration (REALI)

The REALI was comprised of three questions:

Based on your pre-move preparations and information, please rate the accuracy of your knowledge about:

… the Israeli social situation and your ability to fit into Israeli society.

… the Israeli economic situation and your ability to find work.

…how realistic your expectations were on life in Israel?

Respondents rated the first two questions with a five-level response (insufficient, not good, so–so, good, great) and the last question with a five-level rating (definitely not, not really, so–so, good, great). Total score was tabulated by summing the three responses: insufficient/definitely no = 0, not good/not really = 1, so–so = 2, good = 3, and great = 4; consequently, scores ranged from 0 to 12. Internal consistency of this three-item scale was acceptable to very good with a Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 for the total sample, and 0.83, 0.77, 0.71, and 0.78 for Canada, South Africa, the UK, and the USA, respectively.

3 Analyses

If the submitted questionnaires (n = 729) were missing values on a few variables used in the study analyses, imputed values were employed using the Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) method (Yuan 2011; Schafer and Olsen 1998). This method enabled more valid estimations than conducting the analyses with listwise deletions (Fichman and Cummings 2003). Comparisons were made by country of origin. Several respondents (n = 88) reported being born in countries (e.g., Greece, Guatemala, Sweden, Philippines) other than Canada, South Africa (SA), the United Kingdom (UK) or the United States (USA). Since these countries were so varied and comparisons to other English-speaking countries would not be meaningful, these observations were not used in this study. Consequently, the final sample was comprised of 89% (n = 641) of submitted questionnaires.

Distributions of variables were examined, including for outliers. Frequencies were reported for categorical variables; and means and standard deviations (SD) were reported for continuous variables. Comparisons were made by country (i.e., Canada, SA, the UK and the USA) using the Chi-square test for Independent Samples with categorical variables and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with continuous variables. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient was used to examine associations between continuous variables for the total sample and by country. Hierarchical regression, with the dependent variable of life satisfaction (measured by the score from the SWLS), was used introducing consecutive blocks of independent variables: demographic variables (gender, age, marital status, college education, monthly income, years since immigration to Israel, health status and country of origin), family support (arrived with family member, had family member in Israel), and acculturation variables (self-identification, language ability, and level of realised expectations). Regression models used the full sample and included a dummy variable coded for country of origin. Beta coefficients, 95% confidence intervals and p values are reported for each variable. Model fit was measured by change of R-squared for each block of independent variables and F-value (and degrees of freedom) for each final model. Significance was declared at p < 0.05. SAS version 9.3 was used for data analysis.

4 Results

The total sample (n = 641) was divided by respondents’ country of origin resulting in four groups: 6.2% (n = 40) from Canada, 10.3% (n = 66) from SA, 20.6% (n = 132) from the UK, and 62.9% (n = 403) from the USA (see Table 1). Among demographic variables, most respondents were: female, between 40 and 64 years old, married, and with college degrees. About two-thirds reported low- or middle-income levels; and on average, reported immigrating almost 17 years ago. More than four-fifths reported excellent/good health status. Among the reasons for immigration (respondents could list more than one), about four-fifths mentioned Zionist or religious reasons, and less than half reported economic or personal reasons. Family support variables indicated that almost half arrived with a family member and about a third had a family member in Israel on their arrival. For acculturation variables, almost half reported a dual country identity (Israel + country of origin), a relatively low Hebrew language level (Mean = 5.2, SD = 3.8 on a scale between 0 and 12) and a moderate level of realised expectations (Mean = 6.8, SD = 2.5 on a scale between 0 and 12). Scores on SWLS indicate moderately high levels of life satisfaction (Mean = 23.5, SD = 6.6). Among groups, significant differences were found by college education, monthly income, years since immigration, health status, Zionist or religious reasons for immigration, economic/personal reasons for immigration, self-identity, language ability, and level of realised expectation after immigration, and life satisfaction.

Correlations for the continuous variables of years since immigration, language ability, realised expectations, and life satisfaction were conducted for the total sample and by country (see Table 2). For the total sample, significant and positive correlations were found: between years since immigration and language ability (i.e., an increasing number of years in the country was related to better language ability), between language ability and realised expectations (i.e., better language ability was related to higher levels of realised expectations), between language ability and life satisfaction (i.e., better language ability was related to greater life satisfaction), and between realised expectations and life satisfaction (i.e., higher levels of realised expectations were related to greater life satisfaction). For all country samples (i.e., Canada, SA, the UK and the USA), significant and positive correlations were found between immigration and language ability, and between realised expectations and life satisfaction. None of the individual country samples exhibited a significant and positive correlation between life satisfaction and years since immigration.

Differences in correlations by country also were found. For example, a significant and positive correlation between language ability and realised expectations was found only for respondents from SA and the USA, but not from Canada or the UK. Also, a significant and negative correlation was found between years of immigration and realised expectation only for respondents from the UK.

The association of demographics characteristics, immigration reasons, family support and acculturation with the dependent variable of life satisfaction was examined in successive blocks using linear regression models (see Table 3). Model 1 examined only the block of demographic characteristics (country of origin, gender, age, married marital status, college education, monthly income, years since immigration, and health status). Model 1 with a total R-squared of 12.5% indicated that greater life satisfaction was found in immigrants who reported having the highest monthly income level compared to the lowest (β = 1.56, p < 0.05) and reporting excellent/good health status (β = 3.43, p < 0.0001), but life satisfaction was lower for respondents from SA compared to the USA (β = − 3.71, p < 0.001). Model 2 added the variable block containing two reasons for immigration (Zionist/religious, economic/personal) to the block of demographic characteristics, achieving a delta R-squared of 1.8% (p < 0.001) (total R-squared of 14.3%). Model 2 indicated that greater life satisfaction was associated with: increased age (β = 0.04, p < 0.05), the highest monthly income level (β = 1.61, p < 0.05), excellent/good health status (β = 3.56, p < 0.0001), and Zionist/Religious reasons for immigration (β = 1.65, p < 0.05). Consistent with the first model, life satisfaction was lower for those from SA compared to the USA (β = − 3.29, p < 0.01). Model 3 added the block containing the two family support variables (arrived with a family member, had a family member in Israel) to the blocks of demographic characteristics and immigration reasons. Neither the delta R-squared of 0.5% (total R-squared of 14.8%) nor the family support variables demonstrated significance; consequently, these variables were dropped from the final model. The final and fourth model added the block of the three acculturation variables (self-identity, language level, level of realised expectations for immigration) resulting in a delta R-square of 3.5% (p < 0.0001) (total R-squared of 18.3%). Thus, this model indicated that greater life satisfaction was found in immigrants who reported excellent/good health status (β = 3.30, p < 0.0001), and having a higher level of realised expectations after immigration (β = 0.69, p < 0.0001).

5 Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between life satisfaction and acculturation for English-speaking immigrants to Israel regardless of country of origin. Unlike prior studies, this study defined acculturation as language acquisition, having realised expectations, and self-identification with host country, as suggested by the BSPAS. Most often, acculturation has been operationalized either by language acquisition or by self-identification. Few studies have examined acculturation using both components, and we found none that added the third component of having realised expectations. However, findings indicated that the study hypothesis was largely unsupported. Life satisfaction was linked only to the single acculturation variable of having a higher level of realised expectations after immigration and the variable of being in good health.

The BSPAS recognised the importance of realised expectations as a part of acculturation, a rarely measured acculturation component. Using a newly created tool, the REALI, this study measured immigrants’ realised expectations for life in the host country with respect to: the social situation, economic situation, and life style. The REALI attained acceptable to good reliability in all four groups of English-speaking immigrants. Other studies have measured realised expectations of immigrants in the host country using a single question about life in general (Simich et al. 2006), a 24-question scale on communication, safety, employment/finances, and racism (Negy et al. 2009), and a 7-question scale on social and economic/employment (Mahonen et al. 2013). Clearly, there is no consensus on the composition of post-immigration realised expectations. A better understanding of this construct is needed to advance the science on immigrants’ acculturation.

Consistent with our results, a study examining the association between life satisfaction and realised expectations among Finns returning from diaspora in Russia found that within realised expectations, only social expectations but not economic expectations were strongly linked to life satisfaction even after a year follow-up period (Mahonen et al. 2013). This study noted that since their study sample was comprised of diaspora immigrants, it was expected that the immigrants would be more interested in the social and cultural aspects of life than the economic ones. Moreover, since these immigrants were coming from and arriving to high-income countries, economic issues were less important. These same beliefs are germane to this study as immigrants are leaving from the high-income countries of Canada, the UK and the USA to live in the high-income country of Israel. Additionally, more than three-quarters of the immigrants in this study were coming to Israel due to Zionist/religious reasons (i.e., returning from diaspora).

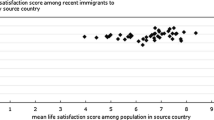

This study found that, until the variable for realised expectations was included in the model, immigrants from SA, compared to those from other countries, reported lower levels of life satisfaction. This finding supports a prior study’s result that the country of origin tends to influence individuals’ level of life satisfaction (Eksi and Kaya 2017), particularly if individuals immigrated as adults and tended to speak their native language rather than the language of the host country (Hajdu and Hajdu 2016). This finding also supports the BSPAS theory component of setting, which includes the complicated connection and interactions of the values and culture of the country of origin with the acculturation process (Bornstein 2017). SA was the only country among the English-speaking countries with a lower ranking, average income per capita than Israel (World Bank 2016) and lower country-level of life satisfaction than Israel (Helliwell et al. 2018) (see Fig. 1). Moreover, SA immigrants were unique as they tended to have lower levels of life satisfaction and realised expectations compared to immigrants from Canada, the UK and the USA in bivariate analyses. These same bivariate analyses showed that immigrants from SA tended to be: less likely to have college education, less likely to immigrate due to Zionist/Religious reasons, reporting lower monthly income, less likely to have a dual country identification with Israel, and lacking language ability. This result is in line with Tartakovsky (2011), who suggests that when expectations regarding immigration to Israel were unmet, the immigrants tended to have lower levels of identification with Israel after arriving to the country (Tartakovsky 2011). Unrealised expectations may arise from misinformation from agencies helping with immigration or word-of-mouth when planning immigration (Amit and Riss 2013). The unique bivariate findings with immigrants from South Africa may indicate that immigrants’ pre-immigration expectations may be even less realistic when there is a different per capita income status between the country of origin and the host country. Thus, this bivariate study’s findings suggest the importance of BSPAS components of setting and domain to immigrants’ acculturation process (Bornstein 2017), and that birth country can influence the level of life satisfaction (Helliwell et al. 2018).

Self-reported life satisfaction for four English-speaking countries and Israel subset of data abstracted from world happiness report (Helliwell et al. 2018)

Studies have noted the relationship among health status, realised expectations, and life satisfaction. Sudanese immigrating to Canada (Simich et al. 2006) and Latinos immigrating to the USA (Negy et al. 2009) had poorer health and higher acculturative stress when they had unrealised expectations. Health status has been linked to life satisfaction in many populations including immigrants ages 15 and older (Frank et al. 2016). Therefore, it was anticipated that in this study’s sample, with immigrants’ average age over 50, health status would be linked to life satisfaction.

Life satisfaction among immigrants has been associated with other acculturation variables. For example, life satisfaction was associated with self-identity that contained the host country for some immigrants but not for others (Amit and Bar-Lev 2015). Additionally, associations between life satisfaction and acculturation variables such as language ability and self-identification with host country have been noted previously (Raijman et al. 2015). This study found no connection between life satisfaction and either acculturation variable of language ability or self-identification. Possible explanations are that the newly developed instrument measuring language ability was insufficiently sensitive (although internal consistency was high), or that other variables such as realised expectations post-immigration had stronger and covarying relationships. Concerning self-identification, a more complex classification of free-text replies could result in a higher connection with this variable.

Life satisfaction has been related to family support in studies on older immigrants (Calvo et al. 2017; Katz 2009; Vinokurov and Trickett 2015; Zhan et al. 2017). Surprisingly, in our study sample with immigrants’ mean age over 50, family support variables were unrelated to life satisfaction in our study, and as a result those variables were dropped from our final model.

This study included numerous variables reflecting the illustrative components of the specificity principle (Bornstein 2017) and examined their association to life satisfaction. Using an individual-centred approach, acculturation demonstrated that life satisfaction was related to only some of BSPAS’ layers of influence. The immigrants’ expectations and health stood out as relevant characteristics for life satisfaction. These two underlying factors of acculturation (Berry 1997) also seem to reflect voluntary (expectations) and involuntary (health) aspects (Boski 2013) relevant for becoming a functioning member of a receiving society.

6 Limitations

This study had several limitations including a cross-sectional study design enabling measurement of association and not causality, a convenience sample of immigrants recruited through primarily online sources, and smaller samples of immigrants from South Africa and Canada compared to the UK and USA. More extensive measures of family support could be applied in the future to verify its correlation with life satisfaction. The newly created REALI instrument contained only three questions to measure post-immigration realised expectations. Although the instrument achieved acceptable to good internal consistency, it will need further testing with different samples of diaspora immigrants. Additionally, some participants did not complete the survey as there were questions such as date of birth and immigration due to fear of identification (written in text fields). As a result, generalisation of study findings must be made with caution. Still, this study recruited a diverse sample of more than 600 immigrants and contributes to the literature by examining more specific components of acculturation—realised expectations for life after immigration—and devising the REALI, a short and direct measure of that variable. Finally, on a different level (beyond individual), an interesting extension of the study would be to compare the immigrants’ expectations with those of the receiving society, juxtaposing acculturation and intercultural strategies (Berry 1997) in the light of models of mutuality in acculturation.

References

Adamuti-Trache, M. (2012). Language acquisition among adult immigrants in Canada: The effect of premigration language capital. Adult Education Quarterly,63(2), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713612442804.

Amir, M., Ayalon, L., Varshavsky, S., & Bulygina, N. (1999). Motherland or home country: A comparative study of quality of life among Jews from the former Soviet Union who immigrated to Israel, Jews in Russia, and Israeli nonimmigrants. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,30(6), 712–721.

Amit, K., & Bar-Lev, S. (2015). Immigrants’ sense of belonging to the host country: The role of life satisfaction, language proficiency, and religious motives. Social Indicators Research,124, 947–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0823-3.

Amit, K., & Riss, I. (2013). The duration of migration decision-making: Moving to Israel from North America. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,39(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.723246.

Amit, K., & Riss, I. (2014). The subjective well-being of immigrants: Pre- and postmigration. Social Indicators Research,119, 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0492-7.

Anaby, D., Jarus, T., & Zumbo, B. D. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the Hebrew language version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Social Indicators Research,96(2), 267–274.

Benish-Weisman, M., & Horenczyk, G. (2010). Cultural identity and perceived success among Israeli immigrants: An emic approach. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,34(5), 516–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.11.010.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Journal of Applied Psychology,46, 5–34.

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,29(2005), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review,55(3), 303–332.

Berry, J. W., & Sabatier, C. (2011). Variations in the assessment of acculturation attitudes: Their relationships with psychological wellbeing. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,35, 658–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.02.002.

Bornstein, M. H. (2017). The specificity principle in acculturation science. Perspectives on Psychological Science,12(1), 3–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616655997.

Boski, P. (2013). A psychology of economic migration. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,44(7), 1067–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022112471895.

Bourhis, R. Y., Moise, L. C., Perreault, S., & Senecal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology,32(6), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075997400629.

Brubaker, R. (2009). Ethnicity, race, and nationalism. Annual Review of Sociology,35(2009), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-l15916.

Brzoska, P., Ellert, U., Kimil, A., Razum, O., Sass, A.-C., Salman, R., et al. (2015). Reviewing the topic of migration and health as a new national health target for Germany. International Journal of Public Health,60, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0617-z.

Calvo, R., Carr, D. C., & Matz-Costa, C. (2017). Another paradox? The life satisfaction of older Hispanic immigrants in the United States. Journal of Aging and Health,29(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315624901.

CBS-Central Bureau of Statistics-Israel. (2016). 4.4 Immigrants(1), by period of immigration, country of birth and last country of residence. http://www.cbs.gov.il/shnaton67/st04_04.pdf. Accessed 11 February 2017.

Cohen, Y., & Kogan, I. (2007). Next year in Jerusalem… or in Cologne? Labour market integration of Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel and Germany in the 1990s. European Sociological Review,23(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcl026.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment,49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research,112(3), 497–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y.

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. (2010). Wealth and happiness across the world: Material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. Journal of Happiness Studies,99(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018066.

Dijkers, M. P. (1999). Correlates of life satisfaction among persons with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation,80, 867–876.

Eksi, O., & Kaya, N. (2017). Life satisfaction and keeping up with other countries. Journal of Happiness Studies,18, 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9724-2.

Fichman, M., & Cummings, J. M. (2003). Multiple imputation for missing data: Making the most of what you know. Organizational Research Methods,6(3), 282–308.

Frank, K., Hou, F., & Schellenberg, G. (2016). Life satisfaction among recent immigrants in Canada: Comparisons to source-country and host-country populations. Journal of Happiness Studies,17, 1659–1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9664-2.

Gamlen, A. (2008). The emigration state and the modern geopolitical imagination. Political Geography,27, 840–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.10.004.

Goldner, S. C., Eckstein, Z., & Weiss, Y. (2015). Chapter 2. The immigration from the former Soviet Union to Israel. In C. Dustmann (Ed.), Economic change. Migration: Economic change, social challenge (pp. 10–32). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hajdu, G., & Hajdu, T. (2016). The impact of culture on well-being: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Happiness Studies,17(3), 1089–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9633-9.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. D. (2018). World happiness report. https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2018/WHR_web.pdf. Accessed 2 November 2018.

Iarmolenko, S., Titzmann, P. F., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2016). Bonds to the homeland: Patterns and determinants of women’s transnational travel frequency among three immigrant groups in Germany. International Journal of Psychology,51(2), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12141.

Inguglia, C., & Musso, P. (2015). Intercultural profiles and adaptation among immigrant and autochthonous adolescents. Europe’s Journal of Psychology,11(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i1.872.

Katz, R. (2009). Intergenerational family relations and life satisfaction among three elderly population groups in transition in the Israeli multi-cultural society. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology,24, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-009-9092-z.

Khvorostianov, N., & Remennick, L. (2015). Immigration and generational solidarity: Elderly Soviet immigrants and their adult children in Israel. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships,13(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2015.992758.

Kunst, J. R., Sadeghi, T., Tahir, H., Sam, D., & Thomsen, L. (2016). The vicious circle of religious prejudice: Islamophobia makes the acculturation attitudes of majority and minority members clash. European Journal of Social Psychology,46(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2174.

Lin, L.-P., Wu, T.-Y., & Lin, J.-D. (2015). Comparison of job burnout and life satisfaction between native and foreign female direct care workers in disability institutions. Work,52, 803–809. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-152117.

Lissitsa, S., & Peres, Y. (2011). Criteria of sociocultural adjustment: The case of the Russian Community in Israel since 1989. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,35(2), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.002.

Lowenstein, A., & Katz, R. (2005). Living arrangements, family solidarity and life satisfaction of two generations of immigrants in Israel. Ageing & Society,25(5), 749–767. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04002892.

Mahonen, T. A., Leinonen, E., & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2013). Met expectations and the wellbeing of diaspora immigrants: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Psychology,48(3), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.662278.

Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q) assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research,50, 940–967.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., Pavlopoulos, V., Obradovic, J., & Masten, A. S. (2008). Acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents in Greek urban schools. International Journal of Psychology,43(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701804412.

Navas, M., Rojas, A. J., García, M., & Pumares, P. (2007). Acculturation strategies and attitudes according to the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM): The perspectives of natives versus immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,31(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.08.002.

Negy, C., Schwartz, S., & Reig-Ferrer, A. (2009). Violated expectations and acculturative stress among U.S. Hispanic Immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,15(3), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015109.

Oppenheim-Weller, S., & Kurman, J. (2017). Value fulfillment and bicultural identity integration. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,48(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116684207.

Ponizovsky, Y., Dimitrova, R., Schachner, M. K., & van de Schoot, R. (2013). Developmetrics the satisfaction with life scale: Measurement invariance across immigrant groups. European Journal of Developmental Psychology,10(4), 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.707778.

Raijman, R., Semyonov, M., & Geffen, R. (2015). Language proficiency among post-1990 immigrants in Israel. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,41(8), 1347–1371. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.982523.

Remennick, L. (2002). Transnational community in the making: Russian-Jewish immigrants of the 1990s in Israel. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,28(3), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830220146581.

Schafer, J. L., & Olsen, M. K. (1998). Multiple imputation for multivariate missing-data problems: A data analyst’s perspective. Multivariate Behavioral Research,33(4), 545–571. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3304_5.

Simich, L., Hamilton, H., & Baya, B. K. (2006). Mental distress, economic hardship and expectations of life in Canada among Sudanese newcomers. Transcultural Psychiatry,43(3), 418–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461506066985.

Stoessel, K., Titzmann, P. F., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2014). Being “Them” and “Us” at the same time? Subgroups of cultural identification change among adolescent diaspora immigrants. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,45(7), 1089–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114534770.

Tartakovsky, E. (2011). Premigration ethnic and national identities: Jewish adolescents planning emigration from Russia and Ukraine to Israel. International Journal of Psychology,46(5), 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.557434.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division. (2016). World youth report on youth civic engagement. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-youth-report-on-youth-civic-engagement.html. Accessed 15 June 2017.

Vela, J. C., & Lerma, E. (2017). Evaluation of the life satisfaction and subjective happiness scales with Mexican American high school and college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,39(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986316681298.

Vinokurov, A., & Trickett, E. J. (2015). Ethnic clusters in public housing and independent living of elderly immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology,30, 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-015-9271-z.

Ward, C., & Geeraert, N. (2016). Advancing acculturation theory and research: The acculturation process in its ecological context. Current Opinion in Psychology,8, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.021.

World Bank. (2016). WV.1 world development indicators: Size of the economy. http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/WV.1. Accessed 3 March 2018.

Yuan, Y. C. (2011). Multiple imputation using SAS software. Journal of Statistical Software,45(6), 1–25.

Zhan, H. J., Wang, Q., Fawcett, Z., Li, X., & Fan, X. (2017). Finding a sense of home across the Pacific in old age—Chinese American senior’s report of life satisfaction in a foreign land. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology,32, 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-016-9304-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zlotnick, C., Dryjanska, L. & Suckerman, S. The Association Between Acculturation Variables and Life Satisfaction Among Israeli Immigrants from Four English-Speaking Countries. J Happiness Stud 21, 1427–1444 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00137-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00137-3