“Everyone wants continuous and genuine happiness.”

Baruch Spinoza (1677/1985)

Abstract

Empirical research focusing on the field of subjective well-being has resulted in a range of theories, components, and measures, yet only a modicum of work leans towards the establishment of a general theory of subjective well-being. I propose that a temporal model of subjective well-being, called the 3P Model, is a parsimonious, unifying theory, which accounts for, as well as unites, disparate theories and measurements. The 3P Model categorizes the components of subjective well-being under the temporal states of the Present, the Past, and the Prospect (Future). The model indicates how each state is important to a global evaluation of subjective well-being and how each state is distinct yet connected to the other states. Additionally, the model explains how measures of subjective well-being are affected by cognitive biases (e.g., peak-end rule, impact bias, retrospective bias), which factor into evaluations of the temporal states, and meta-biases (e.g., temporal perspectives), which factor into global evaluations of life satisfaction. Finally, future research is recommended to further support the model as well as create interventions that can be chosen based on an individual’s temporal preference or that can be designed to counteract certain biases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The preceding quote from Spinoza epitomizes an individual’s basic desire for sustainable happiness. Yet, this raises the question: How do we achieve continuous happiness? Within the field of psychology, understanding subjective well-being (SWB) is a topic of much discourse. In the last fifty years, there has been a concerted effort to empirically investigate SWB, from its correlations (e.g., Seidlitz and Diener 1993; Oishi et al. 2007), to forecasting affect (Gilbert 2006) to cross-cultural differences (Scollon et al. 2005). Yet, only a few have attempted to search for a unifying theory of subjective well-being (e.g., Brief et al. 1993; Feist et al. 1995; Kim-Prieto et al. 2005). My objective is to present a parsimonious model that can unite the various theories, components, and research on SWB under one general, temporal model. As we shall see, trifurcating subjective well-being into temporal building blocks presents a ubiquitous framework for SWB since time affects us all. We each possess a past, present, and future. The notion of time and temporal perspectives has only recently gained momentum in its association with understanding SWB. Yet, in the subsequent sections, we will investigate how the two are mutually inclusive. As an important side note, in this paper I will be using the term subjective well-being instead of terms such as happiness, life satisfaction, or quality of life. Diener (2006) defined SWB as an umbrella term for various types of evaluations, both positive and negative, that people make regarding their lives including evaluations of life satisfaction, engagement, and affect. Let us begin by investigating the current approaches to subjective well-being.

1 Current Approaches to SWB

Before explaining the 3P Model and the relationship of temporal perspectives and subjective well-being, let us begin by surveying the current literature on existing models, theories, and measurements of SWB.

1.1 Existing Theories

With very few universal theories of subjective well-being in existence, one can find many disparate theories and categorizations of SWB. In the following sections we will discuss some examples including, first, the Liking, Wanting, Needing theory; next, the Top-Down/Bottom-Up Factors; then, the Multiple Discrepancy Theory, the Orientations to Happiness Model (Pleasure, Engagement, Meaning), and finally the Mental Health Continuum Model.

1.1.1 Liking, Wanting, Needing

The first model that we will discuss divides the theories of happiness into three categories, the Liking, the Needing, and the Wanting theory. First, the Liking theory represents a hedonic focus. The Liking or Hedonic Happiness theory focuses on maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain (Peterson et al. 2005), which was purported by Aristippus who recommended immediate gratification as the path to a meaningful life (Watson 1895). Hedonic Happiness is the study of what makes events and life pleasant or unpleasant, interesting or boring, joyous or sorrowful (Kahneman 1999).

The needing classification of SWB purports that a set of elements that every human needs, regardless of his/her values, is essential to attaining subjective well-being. Maslow (1943) suggested that a hierarchy existed of five levels of basic needs—starting from physiological needs, safety, love/affection, self-esteem, to self-actualization—that must be satisfied in order, one after another. Wilson (1967) suggested basic universal needs exist; the prompt fulfillment of those needs causes happiness while the needs that are left unfulfilled result in unhappiness.

The third classification is the Wanting Theory, which suggests that subjective well-being is determined by the pursuit of desires or goals. This raises the question: Is subjective well-being derived from the journey or the destination? The wanting theory illustrates that the journey (wanting) is more important than the destination (pleasure from fulfillment of the goal). Davidson (1994) distinguished affect gained from pre-goal attainment from that received through post-goal attainment. The prior concerns the pleasure gained when working towards the goal while the latter typifies pleasure from achieving the goal. Davidson presented that the most pleasure comes from the progress towards a goal rather than the fleeting feeling of contentment when the prefrontal cortex reduces its activity during the accomplishment of a goal.

1.1.2 Multiply Discrepancy Theory

A second model of subjective well-being suggests that we compare experiences or emotions to some standard. Wilson (1967) discussed that satisfaction from the fulfillment of needs depends on the degree of expectation and adaptation. Michalos (1985) explained in his multiple discrepancy theory of satisfaction that individuals compare themselves to many standards such as other people, past conditions, ideal levels of satisfaction, and needs or goals. A discrepancy due to an upward comparison (my expectation was better than the actual vacation) results in decreased satisfaction whereas a downward comparison (my expectation was worse than the actual vacation) will result in an increase in satisfaction.

1.1.3 Top-Down and Bottom-Up Factors

A third theory represents a dichotomous model for the causes of subjective well-being. Diener (1984) differentiated between top-down and bottom-up factors important to SWB. Diener et al. (1999) described bottom-up factors as external events, situations, and demographics. Veenhoven (1999) explained how the data on the average level of happiness in nations indicated that macro-social factors, such as wealth, freedom, and equality, together explain 63% of the difference in average happiness and mark off more or less livable societies. Additionally, Veenhoven (2004) showed that differences in Happy-Life-Years (HLY)—how long and happy people live in a country—can be explained by variations in societal characteristics (e.g. economic development, political democracy, and mutual trust). The explained variance for average happiness is high partly because there is less noise in average happiness ratings than individual ratings (Veenhoven 1999). For individual ratings, bottom-up factors can account for some variance but do not account for all of the variance. For instance, Andrews and Withey (1976) revealed that demographic factors (age, sex, income, education, race, marital status) accounted for only about 8% of the variance in SWB. Many researchers have favored the bottom-up model and have believed that SWB results from a linear additive combination of domain satisfactions such as marriage, work, and health (Andrews and Withey 1976; Argyle 1987; Campbell et al. 1976; Headey et al. 1985). Yet, other researchers have pointed out that domain satisfaction could be consequences rather than causes (Costa and McCrae 1980; Veenhoven 1988). In fact, Diener (1984) claimed that high inter correlations with domain satisfactions could be evidence for a top-down model. In a top-down model, subjective interpretations of events influence SWB as oppose to objective criteria (Feist et al. 1995). Top-down factors represent individual factors (such as values and goals) that trigger external events that influence well-being (Diener et al. 1999). In the top-down model, an individual’s disposition filters and interprets specific, lower-order events (Feist et al. 1995). It is important to recognize the integration of these two theories when holistically understanding subjective well-being (Brief et al. 1993; Feist et al. 1995).

1.1.4 Pleasure, Engagement, Meaning

The fourth theory discussed here is the Orientations to Happiness Model. This theory presumes different ways to be happy (Guignon 1999; Peterson 2006; Russell 1930; Seligman 2006; Peterson et al. 2005). Seligman (2006) defined three roads to happiness, which included positive emotions and pleasure (the pleasant life), engagement (the engaged life), and meaning (the meaningful life). Peterson et al. (2005b) discovered that people choose different paths and that the most satisfied individuals are the ones who choose all three with an emphasis on engagement and meaning.

1.1.5 Mental Health Continuum

Finally the last model discussed is the ‘Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing’ (Keyes 2002), which proposed a gradient from ill-being to well-being. Keyes described individuals with complete mental health as ‘flourishing’ in life with high-levels of SWB. He defined the components of SWB as positive emotions and psychological and social well-being. Additionally, individuals with incomplete mental health are ‘languishing’ in life with low-levels of SWB.

1.2 Measuring Subjective Well-Being

Now that we have reviewed the existing theories of subjective well-being, let us move on to delineate the existing measurement and evaluations of SWB.

1.2.1 Ways of Calculating Subjective Well-Being

One early attempt at creating a formula for SWB denoted the formula created by Bentham (1789/1948) entitled the Hedonic/Felicific Calculus. It accounted for the intensity, duration, certainty, timing, and quality of the event and illustrated that subjective well-being was a balance of pleasure over pain. Another approach from Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) proposed the happiness formula H = S + C + V that calculates your happiness (H) by your biological set point (S), plus the conditions of your life (C), plus your voluntary activities (V). A third approach comes from Diener (1984), who proposed that judgments of life satisfaction could be made by combining positive and negative affect with an assessment of how these moments measure up to one’s goals and aspirations. Finally, Davidson (1992) suggested that the brain might compute both the sum and the difference of the levels of activity in separate systems that mediate positive and negative affect.

1.2.2 Ways of Measuring Subjective Well-Being

Yet, attempting to calculate subjective well-being with one formula is no easy matter due to the numerous variables that can be included in the SWB formula. For instance, Kozma et al. (2000) found that certain measures of SWB reflect short-term (momentary emotions) and long-term (satisfaction and moods) components to different degrees. Additionally, variables represent measurements of evaluations from in the moment, to the aggregation of moments, to the memory of the event, to general assessments of daily, weekly, or over-all satisfaction. For example, the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) (Csikszentmihalyi 1990) measures affect by polling individuals in the moment while the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al. 1988), the Daily Reconstruction Method (DRM) (Kahneman et al. 2004), and the U-Index (Kahneman and Krueger 2006) measure momentary affect through retro-evaluation. Other measurable variables that factor into an evaluation of subjective well-being include recall of an event, interpretation of the event, and one’s mood (Seidlitz and Diener 1993). Well-being additionally can be assessed through psychological functioning (Ryff 1989) and social functioning (Keyes 1998). An approach from Van Praag et al. (2003) suggested that individual total SWB depends on six different subjective domain satisfactions: health, financial situation, job, leisure, housing, and environment. Finally, other global measurements of subjective well-being include the Happiness Measure (Fordyce 1977, 1988), the Satisfaction with Life Measure (SWLS) (Diener et al. 1985), and the Steen Happiness Inventory (Seligman et al. 2005).

1.2.3 The Relationship Between These Variables

Empirical analysis has uncovered the complexity of the relationships among these measures (Kim-Prieto et al. 2005). Currently, we can see that some components of subjective well-being correlate with global life satisfaction, but they do not account for all of the variance. For instance, Oishi et al. (2007) brought forth that the overall frequency of positive affect and negative affect correlated with global life satisfaction .30 and −.04 respectively. Thomas and Diener (1990) showed that the frequency of positive and negative affect correlated with recalled affect .50 and .58 yet the intensity of positive and negative affect correlated with recalled affect .02 to .62. According to Oishi et al. (2007), for happy individuals (as defined through the Fordyce Happiness measure), the frequency and interpretation of positive events correlated .41 and .27 but was uncorrelated with the frequency and interpretation of negative events (.00 and −.02). The findings for the unhappy group showed that happiness correlated with both the frequency and interpretation of positive events (.25 and .28) and negative events (−.32 and −.50). Seidlitz and Diener (1993) reported correlations of average happiness (average weekly PA/NA) and mood of .35 and correlations of current mood and average SWLS (average of two administrations of SWLS) of .27.

1.2.4 SWB: One Temporal, Mutable Construct

What can we learn from all of this data? First, we know that Bentham’s notion of subjective well-being (1780/1948) as the balance of pleasure over pain is an oversimplification. While it is certain that these measures relate modestly, whether these measures assess separate constructs or one single construct with different degrees of error is not clear (Kim-Prieto et al. 2005). Yet, perhaps another explanation can account for this discrepancy. Kim-Prieto et al. suggested that SWB is a unitary construct that changes with the passage of time.

1.3 The Relationship Between Time and Subjective Well-Being

One must consider the passage of time when understanding the construct of SWB because a global evaluation of life satisfaction considers not only current proceedings, but also the moments that have occurred, as well as those yet to be. Since the human brain organizes events into the past, present, and future, SWB can also be considered in the past, present, and future (e.g., how happy I was, how happy I am, how happy I am going to be). Let us look at the existing literature regarding time and subjective well-being.

1.3.1 Current Research on Subjective Well-Being and Time

Many psychologists have researched the relationship between time and subjective well-being from different angles. Kahneman (1999) focused on investigating momentary utility (happiness from the moment) and remembered utility (happiness from the past). Rozin (2008a, b) illustrated that we gain happiness temporally through our experience, our memory, and our anticipation. Bryant (2003) investigated an individual’s ability to savor (sustain) positive events from the past (reminiscing), present (savoring the moment), and future (anticipating). Gilbert and Wilson (2007) discussed our ability to pre-experience the future (prospection) by simulating it in our minds and then use our prospection to predict our future feelings of the event (affective forecasting). Additionally, some researchers have investigated the importance of temporal perspectives (our attitudes about the past, present, and future) on our behavior (e.g., James 1890; Lewin 1942; Fraisse 1963; Zimbardo and Boyd 2008).

While a focus on time and measures of global SWB developed previously (Kilpatrick and Cantril 1960), these studies focused more on the components of SWB separately (Lucas et al. 1996; Diener et al. 1999; Kim-Prieto et al. 2005). A small body of literature focuses on a more united temporal construct.

1.3.2 Existing Temporal Frameworks

Recently psychologists have taken their research a step further by incorporating temporal components into a framework of subjective well-being. Kim-Prieto et al. (2005) developed a temporal framework for subjective well-being where SWB is considered sequentially from the experience of an event to the reactions to the event, on to the recall of the event, and finally to the incorporation into a global judgment about one’s life. Diener et al. (1999) included a temporal distinction of past, present, and future in the construct of life satisfaction in their review of SWB literature. Pavot et al. (1998) suggested that a temporal distinction is necessary to describe the construct of global life satisfaction since the traditional SWLS closely correlates with the present (.92). The authors created the TSWLS (Temporal Satisfaction with Life Scale) where one measures happiness for each temporal state (e.g., how happy I was in the past, am in the present, and will be in the future). Finally, researchers suggest that a balanced temporal perspective (having a positive past, present, and outlook of the future) is crucial towards subjective well-being (Boniwell and Zimbardo 2003; Boniwell et al. 2010).

1.3.3 A Parsimonious Framework

While these models are necessary to understanding SWB because of the temporal incorporation into the framework, they have yet to unite under a parsimonious model. The 3P Model of subjective well-being draws upon these existing theories and current research in novel ways to create said inclusive framework. The objective of the framework is, firstly, to create a model that is generally applicable to all theories of SWB and unifies top-down and bottom up models. Secondly, the model serves to explain the relationship of momentary experiences with global evaluation and explain discrepancies in moving from one evaluation to the next. Thirdly, the framework will illustrate how the integration of happiness from each temporal state results in a meaningful, durable form of subjective well-being.

In the subsequent sections, I will explain the model in detail by discussing the temporal components of SWB as well as the biases that influence evaluations of subjective well-being. Next, I will cover the current research that supports this model and how the temporal states fit together to form a global evaluation of SWB. Afterward, I will discuss the mechanisms behind the model and meaningful happiness according to the theory. Finally, I will discuss the limitations of the model and future research needed to test this theory. Firstly, let us begin by highlighting a few key points and implications of the model.

2 The Key Points and Implications of the 3P Model

I would like to summarize a few key points first before explaining the 3P Model in detail in the following sections.

-

1.

Since not all of our waking thoughts concern the present (Klinger and Cox 1987), our future and past thoughts as well as future and past selves must be considered in the definition of what it means to be happy. Thus, the model builds on the temporal states of the Past, Present, and Prospect.

-

2.

Within each temporal state, long-term measures as well as short-term measures are to be considered (e.g., within the Prospect stage, we must consider happiness derived from one’s sense of purpose as well as pleasure derived from one’s desires).

-

3.

Bryant (2003) suggested that happiness is concerned not just with the ability to feel pleasure but also with the capacity to regulate pleasure, find it, manipulate it, and sustain it. The framework of this general model builds on managing and maximizing happiness (as well as minimizing unpleasantness) as it morphs through time.

-

4.

Cognitive biases (e.g., peak-end rule, impact bias, and retrospective bias) stymie our ability to maximize and maintain pleasure from one temporal state to the next as well as our ability to minimize and curtail pain.

-

5.

SWB is evaluated by the maximization of happiness in each temporal state; however, meta-biases (e.g., personality) account for variations in our global assessment and cumulative assessments of SWB in all the temporal states.

-

6.

The framework inhabits a cyclical model in which evaluations of the present influence past evaluations that affect future evaluations, which, in turn, factor into present evaluations, and so on.

-

7.

Adaptation is the shift from events in our cognitive present to our cognitive past (e.g., a widow might not have adapted to the death of a spouse 2 years later because that loss occupies current thoughts).

Let us now continue by investigating the temporal building blocks of subjective well-being.

3 The 3P Model

3.1 Temporal Building Blocks

3.1.1 Temporal Thoughts

In order to understand why we need a temporal model to explain the components of subjective well-being, we first need to answer the question, “What influences our happiness?” Lofty question—but it has a simple answer: thought. “Really, thought?” you might query. Why is this so? Actually, experience does not influence happiness; rather our thoughts (conscious or otherwise) about experiences influence happiness. While we live in the present, often our thoughts concern the other temporal states (the future and the past). For instance, Klinger and Cox (1987) found that about 12% of our daily thought concern the future. These thoughts of past experiences and future events can fill us with feelings of pleasure (thinking about that great meal you had last Tuesday or thinking about a trip to Disneyland) or unpleasantness (recalling the death of a loved one, or worrying about how much money you have or more likely don’t have for retirement).

The present seems to be the most important temporal state for our happiness because most often thoughts of the present steal our attention and thus are the most salient and accessible. However, the present thoughts alone cannot equate to global evaluations of life satisfaction. For instance, Csikszentmihalyi and Hunter (2003) revealed that although teenagers reported that studying creates less feelings of happiness than most other activities, the amount of time studying was positively related to subjective well-being: negative relationships at the momentary level might lead to a positive global evaluation.

Even within momentary evaluation of affect, frequency, and intensity, we find variance. Thomas and Diener (1990) discovered the correlation range of the frequency of positive versus negative emotions to be .50 to .58 respectively and correlations of positive and negative affect to intensity ranged from .02 to .62. Thus, momentary measures are related to global evaluation but only account for part of the variance in SWB. For example, Andrews and Withey (1976) found that life satisfaction formed a separate construct from positive and negative affect.

Pleasure originates not only from present thoughts but also from thoughts regarding the past (savoring and reflecting on memories) and future (planning and anticipating events). For instance, momentary evaluation can be mitigated by recall (short-term past evaluation) before arriving at global satisfaction (long-term past evaluation). Pavot et al. (1991) showed that recall of good versus bad events correlated .42 with global satisfaction with life.

Elster and Loewenstein (1992) stated that the concept of instant utility (pleasure from the present) should include current sensory experiences but also the pleasure and pain resulting from anticipating future events and remembering the past. Thus, theorists must use the temporal building blocks of the past, present, and prospect as an organizational framework for subjective well-being since SWB derives from pleasurable thoughts of all three. Let us take a moment to introduce these temporal states and their visual representation in the model.

3.1.2 Thoughts in Present, Past, Prospect

In the search for a parsimonious general model of subjective well-being, the first step denoted identifying the fundamental elements. These elegantly simple building blocks (as illustrated in Fig. 1) typify the three states of time: Past, Present, and Prospect (Future). These temporal components are distinct elements (Pavot et al. 1998), but when we view them collectively, the result is a global evaluation of SWB. As you can conclude from Fig. 1, during the temporal stages, happiness embodies varied forms. Some of these forms (as we shall see) are more meaningful and lasting than other forms (i.e., short-term versus long-term constructs). Kozma et al. (2000) discovered that various measures of SWB reflect short and long-term influences to differing degrees. Let us investigate each of these components in more detail starting with the component of the Present.

3.1.3 Present

We will begin with the state that occupies most of our thoughts, the present. Now, while we live in the present, we know that the present is ephemeral. With very few exceptions, the moments in the present simply disappear (Kahneman and Riis 2005). Moods and emotions represent affect, which characterizes people’s on-line (in the moment) evaluations of events (Diener et al. 1999). Present affect can be positive or negative and researchers should measure these two independent factors separately (Bradburn and Caplovitz 1965). Stallings et al. (1997) supplied that the experience of daily pleasurable events related to pleasant affect and the experience of daily undesirable events related to unpleasant affect.

One form of happiness in the present leads to a greater satisfaction with life over pleasure in the present: engagement (Peterson et al. 2005b), also known as flow (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). Flow can be described as mindfulness—the state of being completely lost in the present without worry of the future evaluation of the event. Another form of meaningful happiness in the present is achievement. Should achievement be placed in the present component or the prospect component? Davidson (1994) distinguished between pre-goal attainment and post-goal attainment positive affect. He uncovered that more pleasure comes from the progress towards a goal, which results in greater increases in prefrontal cortex activity, than the ephemeral high from the actual achievement of the goal, which results in the reduction of the prefrontal cortex activity. Related to achievement is self-efficacy and self-determination. Bandura (2000) defined self-efficacy as one’s belief in his/her ability to succeed in specific situations. As one possesses more self-efficacy in a particular area, one is more likely to work towards goals and challenges in that domain than to avoid them. Ryan and Deci (2000) explained in Self-Determination Theory that intrinsic motivation, which refers to the performance of an activity for the inherent satisfaction of the activity itself, leads to the positive potential of human nature.

With each temporal state, distal as well as proximal factors are at play. For instance, affect from a good or bad event would be categorized as a proximal factor while genes, and other external circumstances, can be defined as distal factors. Some accounts have found that demographic factors (distal factors) accounted for less than 20% of the variance in SWB (Campbell et al. 1976).

3.1.4 Past

Kahneman and Riis (2005) called it a basic tenant that we only keep the memories of our experience; thus we view our lives from the perspective of our remembering self. Happiness from the past temporal state refers to happiness obtained from thoughts of and feelings about our past. Components of subjective well-being in the past run the range of temporary feelings of pleasure to more meaningful forms of happiness. A rather short-term form of happiness that can develop into significant happiness with habituation is savoring the past, known as reminiscing. Bryant (2003) studied how pleasure in the present can be generated, intensified, and prolonged through reminiscing about past positive events after the event transpires, and additionally how reminiscing aids in developing the self-concept. Fallot (1980) stated that positive reminiscing could also give one a sense of temporal continuity. Park et al. (2004) discussed how gratitude connects one happily to the past. Gratitude can contribute either to pleasure or to life satisfaction (Peterson et al. 2007) when performed inveterately. A more lasting form of happiness in the past comes from a sense of meaning. I have included meaning in the past temporal state because a sense of meaning is the ability to understand one’s own experiences, themselves, and the world around them (Steger et al. 2008). Research by Moran et al. (2009) yielded that having a sense of meaning in one’s life correlated with life satisfaction by .41.

3.1.5 Future

A future temporal focus is important to SWB (Pavot et al. 1998). The future component of subjective well-being contains forms of SWB ranging from anticipation, to goals, to purpose. First, Bryant (2003) showed how people could generate and amplify pleasure before an upcoming event through anticipation. Next, Austin and Vancouver (1996) showed that individual behavior is best understood by looking into people’s typical aspirations. As mentioned before, just looking towards the future and moving towards one’s aspirations can be more important than the actual end-state of goal attainment (Carver et al. 1996; Csikszentmihalyi 1990). Emmons (1986) found that having goals, making progress towards the goal, and a lack of conflict among the goals predicted SWB. Brunstein (1993) showed that a higher level of commitment towards a goal contributed to higher SWB. Commitment to goals benefits the individual through personal agency and a sense of structure and meaning to daily life (Diener et al. 1999). In fact, personal distal factors such as income, intelligence, and social skills predicted SWB only if they related to the person’s goals (Diener and Fujita 1995; Crawford-Solberg et al. 2002). Kasser and Ryan (1993, 1996) found that intrinsic aspiration (goals such as affiliation, personal growth, and community) was positively associated with indicators of well-being such as self-esteem and self-actualization whereas extrinsic aspiration (e.g. wealth, fame, and image) was negatively related to the well-being indicators. Sheldon and Kasser (1998) showed that regarding attainment of goals, the attainment of intrinsic goals enhanced well-being whereas attainment of extrinsic goals provided little benefit. Third, Snyder (2000) espoused the importance of hope to life satisfaction. Current findings demonstrated that a positive outlook could influence how an individual copes with negative events (Scheier and Carver 1985; Lazarus et al. 1980; Seligman 2006). Finally, having a purpose represents one important component in the future state. Moran et al. (2009) found that having a purpose in one’s life correlated with life satisfaction by .46. Boyle et al. (2009) noted that a greater purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Now, that we have a better understanding of the individual temporal components, let us look closer at how subjective well-being is evaluated in each state.

3.1.6 Temporal Assessments

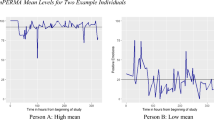

As we see from Fig. 2, measurements of subjective well-being are logically categorized in the same temporal states: Experience measures SWB in the Present, Evaluation measures SWB in the Past, and Expectation measures SWB in the Prospect state. A list of examples of constructs and measurements in each temporal state are featured in Table 1.

3.1.7 Experience

This category of measurement appraises moment-to-moment happiness. Kahneman (2000) referred to an assessment of experience as the sign and intensity of affective/hedonic experience at a given moment in time, which is known as momentary utility. Within the present state, many forms of evaluation offer themselves, including the Experience Sampling Method (Csikszentmihalyi 1990), assessment of positive and negative affect with the PANAS (Watson et al. 1988), and the Daily Reconstruction Method, which takes the form of evaluation but is actually used to access the moment (Kahneman et al. 2004). Kahneman et al. (2004) suggested, to measure experienced utility, the respondent can indicate whether he/she feels impatient for their current situation to end or if they prefer for it to continue. To assess an aggregation of momentary utility, one can use the U-index, which measures the amount of time an individual spends in an unpleasant state (Kahneman and Riis 2005).

3.1.8 Evaluation

In evaluation, the individual is measuring an event or sequence of experiences based on reflection. Kahneman (2000) included two types of utility that fall into evaluation: evaluation of a utility profile and remembered utility. Kahneman stated that evaluation of a utility profile is an observer’s judgment about the overall utility of an experience, whereas, remembered utility is a subject’s own global evaluation of a past experience. The Satisfaction with Life Scale, SWLS, measures global evaluation of the past (Diener et al. 1985). Notably, just as components of temporal states can include proximal versus distal components, likewise measurements of SWB can reflect short and long-term influences in different degrees (Kozma et al. 2000). Evaluation, can be argued, is the most critical temporal measurement. Kahneman and Riis (2005) placed much emphasis on evaluation since SWB concerns the remembered self, when one must consider the question: how satisfied am I with my life as a whole?

3.1.9 Expectation

This category measures the utility gained from thinking about future events. As is the case with the other temporal states, these measurements can be short-term or long-term components of subjective well-being. Bryant (2003) refers to one short-term component as anticipation—looking forward to a good event. Other measures can assess an individual’s positive outlook on the future, such as optimism (Seligman 2006). Other assessments focus on long-term components of subjective well-being within the prospect stage. These can include components such as one’s sense of purpose in life (Ryff 1989) and life goals (Roberts and Robins 2000).

We know that happiness can be derived through thoughts of the present, past or prospect, but what happens when thoughts of a current experience are compared to thoughts about the past or the future? Will those two sets of thoughts be equivalent? Oftentimes they are not. For instance, a surprising finding emerged from studies of momentary happiness: although parents expressed that they gain joy from their children, they often experienced unpleasantness when actually spending time with their children (Kahneman et al. 2004). What’s going on here? Should not the thoughts of momentary experiences be equivalent to the past evaluation? The reason for the discrepancy originates from cognitive biases.

3.1.10 Cognitive Biases

What are cognitive biases? Cognitive biases are patterns of errors in judgment that occur in particular situations. Biases stem from heuristics (rules of thumb), designed for us to make quick decisions by relying on simple rules rather than considering all of the factors (Kahneman et al. 1982). These cognitive biases factor into our evaluations of subjective well-being. As we can see, biases exist between all temporal states (as illustrated in Fig. 1). Let us begin by discussing those types of biases.

3.2 Biases Between Temporal States

Discrepancies exist between judgments of SWB of each temporal state. This model demonstrates that obstacles prevent information from transferring unchanged from one temporal state to another. As you can see from Fig. 1, between each temporal state resides a channel. These channels, I refer to as cognitive biases. Psychologists have researched many of these biases between temporal states. For instance, Kahneman (2000) described psychological rules that influence evaluating past utility while Gilbert (2006) demonstrated distortions looking forward. Many types of cognitive biases can manipulate the passing of information between temporal states. The following section is not an exhaustive list but will identify some important universal biases that affect the judgments of SWB from temporal state to temporal state.

3.2.1 Biases Between Experience and Evaluation (Present and Past)

Many factors contribute to the discrepancy between our evaluation of the present and the past. Fredrickson and Kahneman (1993) showed how people favor a long unpleasant period if the episode ends on a milder note, a bias known as duration neglect. Additionally, they showed how we abide by peak-end rule: when evaluating an episode, people rely heavily on how the event ends, as well as the peak moment. Diener, Wirtz, and Oishi (2001) discussed the ‘James Dean Effect’: a wonderful life that ends abruptly is rated more positively than a wonderful life with additional mildly pleasant years (the addition of a less intense ending to the wonderful life). The authors also described the ‘Alexander Solzhenitsyn Effect’: a terrible life with moderately bad years attached to the end was rated as more desirable than the terrible life that ends abruptly without the moderately bad years at the end.

Strack et al. (1985) showed that respondents included accessible, recent events in the evaluation of their current lives, but if the event was distant (5 years ago or more), they used the event as a standard of comparison when evaluating their current satisfaction. Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) showed that people would reevaluate their engagement in a task if they needed to justify the time spent on attributing meaning to the event. Taylor (1991) found that people expertly reconstruct events in their favor after they occur.

3.2.2 Biases Between Evaluation and Expectation (Past and Prospect)

Other factors contribute to the variability between past and future judgments of subjective well-being. For instance, we neglect to factor in duration when making choices about repeating unpleasant experiences (Kahneman et al. 1993; Schreiber and Kahneman 2000). Additionally, we tend to overestimate the magnitude and generality of the positive or negative feeling generated by an event when predicting future events (Brickman et al. 1978). Wilson et al. (2003) identified that we predict the future poorly because of retrospective impact bias, the circumstance when we overestimate the impact of past events on our well-being. The authors additionally found that the impact bias, the tendency to overestimate the affective impact of future events, may be influenced partially by people’s reliance on salient but unrepresentative memories of the past.

3.2.3 Biases Between Expectation and Experience (Prospect and Present)

When making predictions about the future, we consider not only the present but also the transition to the present. As we shall see, many cognitive biases result from comparisons and the resulting discrepancies. Counterfactual thinking also affects SWB (Roese 1997; Roese and Olson 1995). Counterfactual thinking can be used as a means of comparison for evaluating the present. Kahneman and Miller (1986) explained how, in norm theory, reality is continuously experienced in a context of relevant counterfactual alternatives, each scenario evoking representations of what could have been and what was expected to be. The easier it is to construct a counterfactual scenario, the more the comparison affects the evaluation of subjective well-being. For instance, Medvec et al. (1995) demonstrated that winners of Olympic bronze medals reported more satisfaction than silver medalists probably because it is easier to imagine not having received any medals at all, while for the silver medalists it is easier to imagine winning the gold. Often discrepancies between one’s aspirations and actual standing contribute to SWB evaluation (Markus and Nuris 1986).

A prediction of a person’s initial reaction to a new situation is incorrectly used as a proxy to forecast the long-term effects of that situation (Kahneman 2000). Cohn (1999) identified the transition rule in forecasts of well-being due to winning the lottery and becoming paraplegic. His research showed that in the absence of direct knowledge, people forecast well-being in a long-term state by forecasting the affective impact of the transition to that state. Kahneman (1999) explained, when an episode is considered ‘ex ante,’ then the initial moment of the episode and the transition to the new state dominate the evaluation, but when an episode is considered ‘ex post,’ people evaluate a future state by evaluating the transition to this state.

Kahneman et al. (2006) demonstrated that errors in predicted utility resulting from the heuristic of evaluating states by moments are amplified by a systematic overweighting of certain aspects of the new state; a phenomenon known as the focusing illusion. Kassam et al. (2008) found that people may mistakenly expect to experience less intense affect when an event transpires in the future than when the same event happened in the present. Gilbert et al. (1998) showed that individuals often do not realize the extent to which they will reconstruct an event when predicting how they will feel about it. Gilbert et al. (1998) discovered that people tend to overestimate the duration of their feelings about negative events because they underestimate their immunity to negative affect, known as immune neglect. Finally, we fall prey to a common key bias between our future and our present self if we think that we will like what we want. However, wanting and liking are two different constructs that are not mutually inclusive (Berridge 1999). Berridge (1999) discussed how wanting could be eliminated while still preserving liking. Moreover, Wyvell and Berridge (2000) uncovered that wanting (incentive salience) could be increased without increasing liking (hedonic reaction).

3.3 Meta-Biases

If we look at Fig. 1, we can see that not only do biases exist between temporal states, but also one specific type of biases exists along the circumference of the core of the circle, where SWB is evaluated. This type of bias is called a meta-bias, but also has been called a trait-level bias, external circumstance, or a bottom-up factor (Diener et al. 1999). Schwarz et al. (1987) suggested that people access domain-specific information when evaluating specific life-domains but rely on heuristic cues when evaluating their SWB as a whole. These heuristic cues can stem from meta-biases. For instance, personality is considered a meta-bias.

3.3.1 Personality

Personality is one main meta-bias, specifically extraversion and neuroticism. Fujita (1991) observed that extraversion correlated with positive affect by .71 and that negative affect was proven indistinguishable from neuroticism. Kahneman and Krueger (2006) described how measures of temperament and personality typically account for much more variance of reported life satisfaction than do life circumstances (e.g., measures of psychological depression are highly correlated with life satisfaction). Magnus and Diener (1991) found that personality predicted life satisfaction 4 years later, even with controlling for the effect of intervening life events.

Additionally, some individuals habitually interpret many life events negatively whereas others interpret them positively (Myers and Diener 1995). Oishi et al. (2007) realized that, for happy people, subjective well-being was correlated with the incidence and interpretation of positive events (.41 and .27, respectively) but was uncorrelated with the incidence and interpretation of negative events (.00 and −.02, respectively), whereas for unhappy people, subjective well-being was correlated with the incidence and interpretation of both positive events (.25 and .28, respectively) and negative events (−.32 and −.50, respectively).

3.3.2 Temporal Salience

Temporal salience represents another meta-bias. Schwarz and Strack (1991) showed how evaluations of global well-being and life satisfaction could be significantly affected by minor changes in the wording of a question or how one feels at the time of evaluation. Reported life satisfaction can also be influenced by little things such as finding a dime on the copy machine (Schwarz et al. 1987) and by the current weather (Schwarz and Clore 1983). Bower (1981) showed how moods could increase the accessibility of mood-congruent information in recall. Thus, thinking about one’s life while in a positive mood, one may selectively retrieve good aspects of one’s life and consequently come forth with a more positive evaluation (Schwarz and Strack 1991).

3.3.3 SWB Stability and Adaptation

The literature suggested that a remarkable feature of SWB is its stability (Cummins 2010). Headey and Wearing (1989) explained in their ‘Dynamic Equilibrium Model’ (DEM) that SWB levels maintained consistent in the absence of significant life events, and that if an event resulted in a change of SWB, over time it returned to the previous level. In the DEM, the primary purpose of managing SWB stability is to maintain self-esteem. They called this positive sense of SWB as ‘Sense of Relative Superiority’ since people tend to view their subjective life experiences as better than average. The desire to maintain SWB stability represents an important meta-bias.

Stones and Kozma (1991) proposed in their ‘Magical Model of Happiness’ that SWB maintains stability around a ‘set-point’ and that the best predictor of future SWB is past levels of SWB. Cummins (2010) described in his ‘Homeostatis Model’ that mild threats can cause the level of SWB to vary within its set-point range and as the strength intensifies, the strength of one’s homeostatic defenses increase to maintain SWB stability.

Adaptation to set-point levels represents this extremely influential meta-bias. Adaptation affects not just global SWB evaluations but also individual temporal evaluations. Research on adaptation has shown that we adapt quickly to positive and negative changes eventually returning to a baseline level of happiness (Brickman and Campbell 1971; Kahneman 1999; Lykken and Tellegen 1996). Cummins (2010) described how at the time of SWB evaluation, a powerful emotional state can dominate awareness and overwhelm homeostasis. Moreover, people adapt more quickly to an easily comprehensible and explicable event than to an inexplicable event (Wilson et al. 2005).

Diener et al. (1999) stated that a complete theory of subjective well-being must explain the effects of the temporal context of events, adaptation, what is responsible for adaptation, and what accounts for a person’s inability to adapt. The 3P model can address these concerns by discussing how someone discerns the fine line between the past and the present. When well-being is evaluated, recent events usually have a greater effect than those in the past (e.g., Headey and Wearing 1989; Suh et al. 1996). In other words, events closer to the present influence evaluation more than those in the past.

Adaptation relates to attention. Thus if an event happened in the past, yet still occupies an individual’s present thoughts, the individual might not adapt quickly to the event because the event has not transitioned from the present to the past. This explains Stroebe et al. (1996) findings that after two full years, people who were widowed showed higher average depression levels than non-bereaved persons, although depression rates did decline over this period. The transition (or lack thereof) from the present to the past is a matter of attention. Riis et al. (2005) found that in patients in the end-stage of renal dialysis had no significant differences in average mood throughout the day than the comparison group. Thus, these patients adapted to their momentary experiences. Kahneman and Krueger (2006) stated that this could be the result of attention, whereby these circumstances occupy the individual’s attention for a waning portion of the time as they gradually lose their novelty. Thus, the more the circumstance loses novelty, the more it loses a portion of the time in one’s attention, the more it fade from one’s attention, the more it drifts into the past.

3.3.4 Cultural Biases

Moreover, meta-biases stem from cultural influence as well. Schimmack et al. (2002) showed that Japanese-American students report lower levels of well-being than white American students in retrospective (evaluative) reports, but equivalent levels in momentary (experiential) reports. Additionally, Oishi et al. (2007) explained that it took close to two positive events to mitigate one negative event for European Americans, only 1.3 positive events for Asian Americans and Koreans, and only one positive event for Japanese test subjects to mitigate a negative event.

Although, personality, temporal salience, adaptation, and cultural influences represent intrinsic types of meta-biases, one classification, potent yet understudied, has yet to be mentioned. In the following section, we will investigate the meta-bias of temporal perspectives and its fundamental influence on global evaluations of life satisfaction.

3.4 Temporal Perspectives

Let us begin by defining temporal perspectives. Time perspective represents an individual’s style of relating to the psychological concepts of the past, present, and future (Lennings 1996). Zimbardo and Boyd (2008) described time perspective as the often unconscious personal attitude towards time and the process whereby the continual life flow is categorized into temporal states that help to give order, coherence, and meaning to our lives.

Boniwell et al. (2010) suggested that temporal perspectives could be differentiated in three different ways. Firstly, it can represent people’s positive or negative attitude towards that state (temporal attitudes). Secondly, it can reflect in which temporal state people tend to cognitively spend their time (temporal preferences). Finally, it can reflect the strategic decision-making process involved in weighting benefits of one particular state over another (perceived utility). Thus, when making temporal decisions, one can factor in their preference towards a state, their evaluation of the state, and their perceived utility from that state.

3.4.1 Temporal Attitudes

Zimbardo et al. published the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI) (1997) and Zimbardo and Boyd published the Transcendental-future Time Perspective Inventory (TFTPI) (1999) identifying six time perspectives: past-positive, past-negative, present-fatalistic (belief that fate determines one’s life), present-hedonistic (pleasure in the present), future (concerned and conscientious about future consequences), and transcendental future (belief that death is a new beginning). The past perspectives represent someone’s evaluation of a state, while the other four perspectives represent one’s temporal preference. Bryant (2003) explained that savoring represents a belief in one’s perceived ability to control positive emotions, which is independent of one’s perceived ability to control negative emotions. Bryant continued by explaining that individuals can differ in their capacity to savor different temporal states: whereas some look forward to upcoming positive events (anticipators), others are present-focused (savoring the moment); yet others enjoy thinking about positive events that already transpired (reminiscing).

3.4.2 Temporal Preference

We can categorize people by their temporal preference: Dreamer, Doer, and Documenter. The dreamer finds the most happiness as he expects and plans for an event, hopes for an event, and/or anticipates an event. The Doer finds the most happiness in the feeling of the experience and in being in the moment. Finally, the Documenter gains the most happiness when processing the experience and understanding its meaning. I would suggest that a person might have a combination of all these styles but that often one style dominates the others.

These beliefs on savoring can emerge from preferred temporal states or from the inability to enjoy positive emotions in a certain state. For instance, Bryant (2003) explained how an ephemeral view of the present could prevent savoring in the moment and spread to the inability to rekindle those positive emotions afterwards, some might dread the future rather than look forward to it, and others might feel disconnected from their past and thus unable to recall positive events.

Because subjective well-being is divided into three temporal states and we measure our SWB in each state based on the pleasure derived from expecting, experiencing, or evaluating, we need to understand on which state(s) our attention is focused. Our preferences towards a certain state influence our overall subjective well-being—a poignant insight especially in regard to aging and the moribund state. A person on her deathbed, for example, focuses her attention on weighting judgments of experience (affect from dying) with evaluation (assessing her sense of meaning in life). If she had a proclivity towards only focusing on experience, then she would not be happy on her deathbed because she would be focusing more on the experience of dying than her sense of meaning from her life. Yet, if the person had a tendency to find happiness in evaluation and evaluated her life as fulfilling, then she would feel comfortable weighing that against the salience of mortality and find peace while dying.

3.4.3 Perceived Utility

Finally, temporal preferences can be evaluated based on perceived utility. Ben-Shahar (2007) described in his ‘Hamburger Model of Happiness’ that we make decisions (evaluate temporal utility) about what makes us happy not only based on the experience of the event but also the future consequences of that experience.

Rozin (2008a, b) illustrated this deliberate weighting when we must choose between a familiar experience and an unfamiliar experience. Rozin stated that novelty improves the Remembered State but threatens anticipation and experience because the outcome is less predictable. Although familiar experience seems to provide more positive experiences, some individuals choose new experiences over familiar experiences. And, why is this so? Perhaps individuals have a predilection or weighting towards one state over the other. For instance, an individual might gain more joy from anticipation than from reminiscing and thus might choose the novel experience.

Simons et al. (2004) explained in ‘Future Time Perspective’ (FTP) theory that the degree to which people are able to foresee the future implications and usefulness of their present behavior differs for individuals. Individuals with extended FTP set motivational goals in the distant future and develop a long-range path to achieve these goals (De Volder and Lens 1982). For individuals with extended FTP, present actions acquire higher utility value (Eccles and Wigfield 2002) and are perceived as more instrumental (Miller et al. 1999) because they are able to anticipate future goals. Because the anticipated value of the future goal is higher, individuals with extended FTP view their present task as more engaging (Simons et al. 2004).

Remarkably, Boyd and Zimbardo (1997) disclosed that, in one’s evaluation of perceived utility, many individuals partition the psychological future into pre- and post-death. Additionally, Simons et al. (2004) described how motivational goals can vary from short to long with some final goals extending beyond the individual’s lifetime (e.g. saving money for one’s funeral). Thus, the post-death future (or transcendental future) factors into subjective well-being decision making.

To recapitulate, thus far we have examined how thoughts are temporal (focus on the present, past, and prospect) and that a class of thought known as cognitive biases and meta-biases results in discrepancies between temporal evaluations of the same experience, as well as between temporal evaluations and global evaluations. As you can see, we have begun to explore how the panoply of thoughts from different temporal states interacts to form evaluations of life satisfaction. Now, let us investigate how new thoughts mutate our protean ideology.

3.5 The Interplay of Temporal Thoughts

Imagine a single drop of water falling into a glassy pool. The result—a wave of ripples extends across the water. The single pebble’s effect touches and changes the water (once placid) meters away. If we think of the pebble as one new thought added to our consciousness (the pool) already filled with old thoughts (the placid water meters away), we can begin to imagine how a new thought entering into our consciousness can affect our evaluation of old thoughts.

3.5.1 Re-Evaluation

To explain this concept, let’s say that you just stubbed your toe. Sure, you feel pain in the present, but it is not going to devastate you because you know that pain is finite and short-term. But, let’s say that you were horseback riding, thrown from the horse, and have injured yourself. During the time of this event, the psychological pain is much worse than the pain of the toe-stubbing because at this moment, the negative emotions permeate from the connection of this event to thoughts of the past and the future. Because you are worried that you might become paraplegic, your thoughts might jump to memories of the time when you ran the Boston marathon or went salsa dancing with friends (past) and how you might not be able to do those things again (prospect). Thoughts can be sustained and amplified by its cognitive association with thoughts from other temporal states and from other experiences.

3.5.2 The Power of Transfer

Why is this so? The studies by Rozin and Royzman (2001) on the power of transfer might answer this question. The authors found that features of contagion include the ability of any property to be transferred, a permanence effect, and a negativity bias evidencing that negative contagion is more potent than positive. The authors showed how negative events can be easily transferred from a present experience to a past evaluation of that experience to future decisions on choices of actions.

The power of transfer applies to positive events as well. A positive event in the present can create a ripple effect on our past and future thoughts as well. For instance, if I was a pre-med student who had just found out that I got into a highly competitive medical school, I might reevaluate my negative thoughts of studying for the MCAT and perceive it as less unpleasant than before when I was studying for the test.

Additionally, pleasure from a new thought builds on past pleasant thoughts. For instance, Kahneman and Riis (2005) illustrated how certain moments are privileged because they acquire special significance by affecting the utility of other moments (e.g., graduating from college is both anticipated for an extended time prior and recalled frequently after the fact). The significance of an event can be increased through consciously extending the pleasure of the experience to the other temporal states.

However, there is one caveat worth mentioning. Oishi et al. (2007) suggested that as one’s global life satisfaction increases, the potency of each negative event increases as well (negative events become aberrant and more salient), and more positive events are needed to offset one negative event. Consequently, one feels more driven to achieve stable and continuous well-being out of fear that the potency of a negative event could adulterate our accumulated well-being.

3.5.3 Increasing Duration of Positive Thoughts

Bryant (2003) discussed how the significance of an event could be generated through mindful attention to the experience, consciously storing concrete details about the event and recalling these memories as vividly as possible. However, well-being can be extended only when the temporal states are used to connect pleasure rather than supplanting emotions of another temporal state. Bryant (2003) evidenced that reminiscing to gain perspective and self-insight in the present is associated with greater positive outcomes; yet reminiscing to escape the present is associated with a lower perceived savoring ability.

However, Bryant (1989) demonstrated that people make different self-evaluations of their ability to avoid and cope with negative events and to obtain and sustain positive experiences. Thus some people might be good at minimizing destructive thoughts but not able to sustain positive thoughts because positive and negative emotions are only weakly correlated with each other (Bradburn 1965) Additionally, Diener and Emmons (1984) recognized that, as the time frame increased, pleasant and unpleasant affect became increasingly separate.

3.6 The Interplay Between Evaluations of Temporal Components

It is important to examine not only how one new thought can affect established evaluation but also investigate how thoughts of an entire temporal component (e.g., thoughts of the past) can affect another temporal component (e.g., evaluations of the prospect).

3.6.1 The Influence of Thoughts of the Past to Thoughts of the Future

We can see how the past perspective relates to the future perspective. In fact, research has shown that recalled affect could be a better predictor of future events than the on-line (in the moment) experiences (Wirtz et al. 2004; Oishi 2004). Additionally, low aspiration might result from a series of past failures (Diener et al. 1999). Boniwell et al. (2010) found an association between past negative and future orientations, which they suggested might result from negative past experiences or from the fact that future-oriented people have a more critical view of their past than hedonists.

3.6.2 The Influence of Thoughts of the Past to Thoughts of the Present

The past is also associated with present perspective. Drake et al. (2008) found that a past negative attitude had a positive correlation with negative affect and a negative correlation with ‘subjective happiness’ scores. Boniwell et al. (2010) detected that a negative past perspective correlated with a fatalistic view of the present, possibly resulting from a feeling of loss of control and willpower (Metcalfe and Mischel 1999) and also learned helplessness (Abrahamson et al. 1978). Past positive emotions correlate with present positive emotions as well. Bryant (2003) showed that the strongest correlation (.86) between temporal savoring was between savoring the moment and reminiscing.

3.6.3 The Influence of Thoughts of the Present on Thoughts of the Future

Finally, we also see how the future can impact the present; extreme obsession with the final outcomes of one’s goals is negatively related to well-being (Mclntosh and Martin 1992). The future can also affect global evaluations of SWB. Boniwell et al. (2010) found that the future orientation was correlated with lower levels of subjective well-being; however, if an individual’s future orientation is associated with a positive past and present hedonistic orientation, they have a higher sense of well-being. Oishi et al. (1999) noted that people gain a sense of satisfaction from activities that are congruent with their values. We find that the temporal states not only have an effect on other temporal states but also on global evaluation of SWB. For instance, Emmons (1986) found that certain aspects of one’s aspirations influence positive and negative affect as well as predict SWB.

3.7 A Harmony of Temporal Components

Are thoughts of one temporal component more important than thoughts of another temporal component? Said another way, is the past more important than the future? Is the present more important than the past? When seeking well-being should we focus on one state over another? Boniwell and Zimbardo (2003) described how some scholars proposed that a time orientation with a focus on the present was prerequisite for well-being including Csikszentmihalyi (1990) and Maslow (1971). Yet, Zaleski et al. (2001) provided that a future-orientation and long-term goals positively correlated with almost all aspects of well-being, especially a meaningful life. Perhaps, the most important matter is not to find if one state is more important to focus on versus others, but rather considering how all three temporal states and their interplay lead to greater subjective well-being.

Bohart (1993) argues that a balanced time perspective allows people to move into the future, having reconciled themselves to their past experiences while staying grounded in the system of meanings derived from the past. Thus, as Bohart mentions, balanced time perspectives are import to reconcile temporal states. A balanced temporal perspective is important in order to sustain and amplify well-being.

3.7.1 Balanced Temporal Preference

Zimbardo (2002) stated one needs a balanced temporal perspective of the past, present, and future and the integration should be flexible to best fit our needs. Pavot et al. (1998) introduced the Temporal Satisfaction with Life Scale (TSWLS) in order to allow participants to focus on a specific time frame when evaluating their SWB. The authors found that the correlation between Past and Present, Present and Future, and Future and Past Life Satisfaction was .70, .58, and .60 respectively. Additionally, they realized that the addition of a future-oriented item on the TSWLS produced a significant increase in the prediction of peer-rated well-being over the current SWLS. When comparing the TSWLS and the ZTPI, Boniwell et al. (2010) found that the two past perspectives of the ZTPI related to satisfaction with the past, the present hedonistic perspective related with the present and future scales of the TSWLS, and that the satisfaction with the past and the satisfaction with the present on the TSWLS are strongly related.

We understand that all temporal states must be considered in order to achieve subjective well-being, but when we are making decisions and we are considering each temporal state, should we consider the temporal state in any particular order? The 3P Model would imply that we should use a particular sequence when evaluating temporal components together.

3.8 A Cyclical Model

3.8.1 A Continuous Assessment Process

When making decisions about one’s well-being, temporal components should be considered in a particular order. As we can see from Fig. 1, one must, in this order, start by considering the Prospect stage, then the Present stage, and then the Past stage when making decisions about one’s well-being. The assessment process starts in the Prospect stage because humans have a priori or learned expectations of future events. Next, we experience the event and have a moment-to-moment assessment of whether the experience is feeling positive or negative, known as moment-utility (Kahneman 1999). Then, we can decide if we should continue the event or stop. After, the event we evaluate it to determine if we should repeat it. Finally, the next time we are likely to enter into that event, we have an expectation that is in some way based on our past evaluation. For example, let’s say that you are going on a blind date. You start the blind date with a certain expectation. Based on the blind dates of your friends you feel that this will probably not go well. Once you start the date, you are assessing the moment-utility to determine if you should have a friend call your phone and give you a phony excuse to leave. You decide to follow through with the date but afterwards, because overall the date was not a pleasant memory, you decide that most likely you will not accept a blind date again. As we can see, in a sort of cyclical process an experience in one stage can affect the next stage.

3.8.2 Clockwise Direction

During the process of evaluation, the model stresses the importance of evaluating temporal states in a clockwise direction from prospect to present to past to prospect. This process works for (1) short-term components of SWB or (2) long-term (more meaningful) components of SWB. (1) Short-term components: for example, anticipatory savoring can affect present enjoyment of an event, mindful present enjoyment of an event can affect remembered utility, and remembered utility affects if you want to repeat the event or not. (2) Long-term components: we experience an engaging event, for instance, we then evaluate the event as engaging because it renders meaning, we decide to pursue meaningful events as a new purpose, and thus we enjoy events that are related to our sense of purpose.

If the process is reversed to a counterclockwise process, it can result in a decrease of satisfaction. For, instance, Bryant (2003) observed that a higher degree of anticipation before a vacation predicted a higher reporting of the vacation, whereas a higher reminiscing score predicted a lower level of satisfaction during the vacation and higher levels of frustration and disappointment with the vacation. The reason for this phenomenon could be the change of one’s SWB baseline. Strack et al. (1985) found that recalling happy events can actually lower one’s present subjective well-being by raising one’s hedonic baseline if the reminiscing occurs in an emotionally uninvolving way.

3.8.3 Continuous vs. Uninterrupted Well-Being

This model does not suggest that we can arithmetically average up SWB evaluations because SWB is a process, where information passes through channels of biases. Thus, a simple summation of the SWB score in each temporal state would not equal the net SWB score starting at Prospect and ending at the Past state. Meaningful well-being is meaningful because it continues from state to temporal state. We then ask, is it possible or even desirable for well-being to be continuous? I would argue that continuous does not imply uninterrupted but rather, that the events that produce feelings of happiness are not ephemeral and can connect and transfer positive energy to the next temporal state.

A cyclical model intuitively depicts ‘overall trend’. Kahneman (1999) described overall trend: a sequence of increasingly unpleasant experiences is judged much more unpleasant than the same experiences in the reverse order. Loewenstein and Schkade (1999) showed that we prefer rising patterns of happiness during anticipation and remembering. If we thought of SWB as cyclical and connected to all temporal states, then we would prefer rising patterns because they appear more stable and able to transfer energy at the end of the state than declining patterns.

3.8.4 Developmental Stages

The 3P model can be used to reflect the relationship between human development and subjective well-being. In human development, as particular to middle-class American society, three major stages of life correlate with the 3E Model of Measurement. We begin with childhood (Fig. 3). In this stage, we focus on experience: learning, discovering, and enjoying the world. We do not initially think about the past nor the future, probably as a result of our neurobiolological development. Marcus (2008) suggested that teenagers are motivated by short-term rewards because their nucleus accumbens (responsible for rewards) matures before the orbital frontal cortex (important for long-term planning). Thus, they can only think of the present pleasures rather than of future benefits.

Then, in adolescence and our college years, our attention is shifted to the future, to finding our purpose and anticipating what is in store for us. According to Pavot et al. (1998), students indicated a higher level of future life satisfaction than their present or past in comparison to non-students.

When we reach our 30s and 40s, we try to find meaning in our life and understand the importance of the experiences we choose. Kamvar et al. (2009) found that young people are more likely to associate happiness with excitement, whereas older people equate happiness with a sense of calmness, peace, and connectedness. Pavot et al. (1998) suggested that a temporal framework helps to evaluate SWB because an adolescent might have an average level of satisfaction but have a high level of satisfaction in the future, but an older person might have a high level of satisfaction with the past or present but a low level of satisfaction with the future because of health or economic factors.

Interestingly, this path in human development goes the opposite direction of the flow of the 3E Model. After experience in the 3E Model, we would move into evaluation, to understand our experience and use this information for expectations and towards discovering our purpose. Constructs of one’s future are largely derived from past and present experiences (Cottle and Klineberg 1974; Fraisse 1963). Yet, in American development, after experience we are pressured by societal norms to create expectations of our lives and only then do we evaluate it. Erikson (1963) suggested that the period from adolescence to early adulthood is a time for self-identity. McAdams (1985) argued that identity becomes salient when a young person notices the discrepancies between their present and past self and the projected future self. A way to remedy this dissonance is to reflect on the past to gain insight and create a more congruent sense of self (Bryant et al. 2005).

Since we have discussed how the temporal states connect and interplay to form our evaluations of life satisfaction, we must discuss ways of increasing our subjective well-being by leveraging our knowledge of this interplay.

3.9 Increasing Subjective Well-Being

Happiness stems from our thoughts. New thoughts affect old thoughts. Thoughts of one temporal component connect to thoughts of another temporal component. Because our web of thoughts results in a unified refection of our life, research must investigate how to leverage conscious control of thought to bolster our subjective well-being.

3.9.1 Controlling the Transfer of Thought

Kahneman and Riis (2005) stated that generally spending more time in the good states and less time in the bad/empty states increases well-being. We know that just the frequent experiences of positive events have shown to be correlated with high SWB (Pavot et al. 1991; Schimmack 2003). Additionally, our objective is to decrease the spread of negative emotions and promote the spread of positive emotions (Bryant 2003). For example, Zimbardo and Boyd (2008) suggested to neutralize negative past events or discover some positive element to remember in the future. One method for maximizing good thoughts is through associative memory.

3.9.2 Associative Memory

As mentioned, Kahneman and Riis (2005) stated that privileged events gain significance by their connection to other states. An event gains meaning (becomes privileged) as it connects to other events in its own temporal state and through other temporal states. Consolidation theory suggests that memories either strengthen to become immutable and permanent or gradually weaken to be soon forgotten (McGaugh 2000). Forming associations between items denotes an intrinsic strategy for the successful formation of long-term memories (Onoda et al. 2009). Additionally, Collins and Quillian (1969) showed how the meanings of words are embedded in networks of other meanings. Harley (1995) explained how information acquires meaning through its relationship with other information, a concept known as cognitive semantic networks. For instance, the word “mom” has much more significance than the word “chia pet” (well, that is, for most people). But why is this important?

It is important because events that can be cognitively associated with a sense of purpose or meaning lead to subjective well-being. For instance, Kim-Prieto et al. (2005) explained that goal-related factors and those preeminent in their lives (such as jobs or relationships) appear to have more impact on people’s reports of SWB. Thus, events in the present that relate to one’s sense of purpose (prospect) and meaning (past) influence SWB more than unrelated events. For example, Andrews and Withey (1976) revealed that an individual’s evaluations of generally distal factors, such as the government and other institutions, have little relation to measures of SWB. Thus, choosing meaningful, purposeful events increases our SWB. For, as we associate a pleasant event with another event, that memory becomes stronger and indelible in our minds. Memories that have strengthened with time maybe assessed faster (Ellmore et al. 2008). Let us spend a few minutes discussing the importance of accessibility of information.

3.9.3 Accessibility of Information

Salient, and thus highly accessible information is strongly influential in evaluations of subjective well-being (Schwarz and Strack 1991). For instance, Schimmack et al. (2002) found that this extends to domain salience since for some individuals, information about romantic life is more chronically salient than for others, and hence is more likely to affect their evaluation of life satisfaction (the keyword being “chronically”). Diener et al. (2002) discovered that, when evaluating their life satisfaction, some individuals place a larger weight on those domains with the biggest problems, whereas others weight their best domains. Thus, focusing on the negative or the positive aspects of one’s life depends on each component’s salience.