Abstract

Numerous medical associations have identified firearm injuries as a public health issue, calling on physicians to provide firearm safety counseling. Data suggest that while many physicians agree with this, few routinely screen and provide counseling. We aimed to survey Maine physicians to assess their current firearm safety counseling practices and knowledge of a new state child access prevention (CAP) law. We conducted an anonymous cross-sectional survey of Maine primary care and psychiatry physicians. We recruited multiple statewide medical organizations, residency programs, and two major health systems to distribute the survey to their membership. Group differences were compared by physician rurality and years in practice using Fisher’s Exact and Chi Squared tests. Ninety-five surveys were completed. Though most participants agreed that firearm injury is an important public health issue that physicians can positively affect (92%), few had received prior firearm safety counseling education (27%). There were significant differences in firearm screening frequency, with rural physicians screening more often. More rural physicians and physicians with > 10 years of clinical practice felt they had adequate knowledge to provide meaningful counseling, compared with non-rural and early career physicians, respectively. Overall, 62% of participants were unaware of the 2021 Maine CAP law. This study highlights significant differences in firearm safety counseling practices among Maine physicians based on rurality and years of experience. Participants also reported a significant gap in knowledge of a recent state child access prevention law. Next steps include development of firearm safety counseling education tailored to Maine physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2020, firearms were, for the first time, the leading cause of death for children aged 1–19 years [1]. In fact, firearm deaths among children and adolescents in the United States increased more than 40% between 2018 and 2021 [2]. Firearm deaths have also been increasing in Maine [3]. According to data from the CDC and RAND corporation, Maine’s firearm deaths (12.6 per 100,000) [3] and household firearm ownership rate (47%) [4] are currently the highest in New England. In 2021, Maine passed a child access prevention (CAP) law, requiring firearms to be secured in households with children under 16 [5].

The American College of Physicians (ACP) [6], American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [7], American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) [8], American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) [9], and American Psychiatric Association (APA) [10], have identified firearm-related injuries and deaths as a public health issue, calling on physicians to provide counseling on firearm safety counseling [11,12,13,14]. Proponents have also argued that primary care providers (PCPs) should have knowledge of state laws, including knowledge of safety practices for different types of firearms to provide adequate counseling [12, 15]. Research has shown that physician-led firearm safety counseling increases safe storage practices and reduces rates of firearm carriage and acts of violence [15].

Understanding that the landscape of firearm ownership and injury are different from the other states in the region, we conceived of this cross-sectional survey of Maine physician’s firearm safety counseling practices as a needs assessment to inform the development of a firearm safety counseling education program tailored to Maine physicians. We hypothesized that there are gaps in the firearm safety counseling provided by Maine physicians that might be addressed by an educational intervention.

Methods

We received institutional review board approval to conduct a cross-sectional survey of Maine physicians regarding firearm safety counseling practices. We developed a fifteen-item anonymous survey using multiple choice questions to describe demographics, prior training, current practices, and barriers, and Likert scale questions to assess knowledge and values (see supplemental information, Figure S1). The survey content was based on a review of the literature [16,17,18,19] except for one question regarding the 2021 Maine CAP law. The survey was piloted among six physician volunteers for feedback on readability and ease of completion. These responses were not included in the data analysis.

Participant Recruitment

All physicians practicing in Maine in psychiatry and primary care fields, including pediatrics, family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and their subspecialities were eligible to participate in this study. From May to July 2023, we recruited physician members from the Maine Chapters of the AAP and AAFP, Maine Medical Association, as well as pediatric, internal medicine, family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology (OB/Gyn), and psychiatry physicians from two major health systems, and resident physicians in pediatrics, family medicine, and OB/Gyn in one health system. Physicians were invited to participate using a public REDCap link that was distributed by email or newsletter. The Maine AAP shared the survey link in four weekly newsletters. All other recruitment emails and newsletters were sent once. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants could choose to leave any question blank. To preserve anonymity, we asked participants to describe their primary practice location as rural, suburban, or urban, rather than report their zip code, which could be used to identify physicians in rural areas.

Group differences by self-reported physician rurality and years in clinical practice were assessed using Chi-squared and Fisher’s Exact tests. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Effect sizes were not calculated given that all categorical variables had at least three groups. All analyses were conducted in R v. 4.2.1. Reporting was guided by the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies [20].

Results

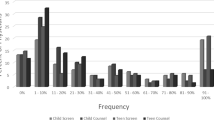

There were 95 survey responses. The majority of respondents identify as female (68%) and were practicing for < 10 years (60, 64%). Most respondents were pediatricians (41, 43%) or family physicians (31, 33%). Respondents were asked to describe practice location by rurality: urban (37, 39%), suburban (35, 37%) and rural (22, 23%). Though most participants agreed that firearm injury is an important public health issue that physicians can positively affect (92%), few had received prior firearm safety counseling education (27%). Overall, 62% (59) of participants were unaware of the 2021 Maine CAP law.

Table 1 shows participants’ current practices and confidence level in firearm safety counseling, stratified by rurality of practice. There were significant differences among practice locations in terms of how often providers asked about firearms in the home, with rural physicians screening more often. 73% (16) of rural physicians felt they had adequate knowledge to provide meaningful counseling, compared with only 29% (10) of suburban and 32% (12) of urban physicians (p = 0.004). Despite this, rural physicians were no more likely to be aware of the 2021 Maine CAP law.

There were also significant differences with respect to years in practice in terms of knowledge of firearm safety principles and legislation (Table 2). More experienced physicians were more likely to feel they had adequate knowledge to provide meaningful counseling. Further, they were the subgroup with the greatest likelihood of being aware of the 2021 CAP law at 50%.

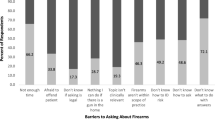

Participants were asked which patient factors prompt them to ask about firearms in the home; children (64, 67%), patients with mental illness (58, 61%), someone in home with mental illness (41, 43%) and patients with substance use disorders (32, 34%) were the most common. Participants also cited significant barriers to providing counseling, with lack of time being the most common followed by lack of knowledge (43, 46%) and lack of resources to provide to patients (37, 40%).

84% (80) of participants indicated they were somewhat to very interested in further education on firearm safety counseling. Participants interested in additional education preferred an asynchronous webinar (66%, 53) or printed literature (55%, 44).

Discussion

This cross-sectional survey found broad agreement among Maine physicians that firearm injury and death is an important public health concern that physicians can positively affect. Rural physicians were more likely to screen for firearms in the home, and to feel that their knowledge about firearm safety principles was adequate to provide meaningful counseling compared with suburban and urban physicians. However, rural physicians were no more likely than other physicians to know about the 2021 CAP law [5] revealing a disconnect between confidence in the subject matter and awareness of important new statewide policy changes.

In addition, early career physicians were less likely to feel confident in their ability to provide firearm safety counseling and were more likely to be unaware of the 2021 CAP law [5]. This suggests a similar knowledge gap for more recent graduates that could be addressed by educational initiatives. There was broad interest in further education among those surveyed, particularly in the form of an asynchronous webinar tailored to practicing physicians.

Several studies have surveyed physicians and trainees throughout the country on their views on firearm-safety counseling, as well as their experience and training. Physicians and trainees who received formal training, were more likely to report a higher level of knowledge and comfort with firearm safety screening and counseling [17,18,19]. Survey participants favored an educational webinar offering continuing medical education (CME) credit, as well as a standardized screening tool built within the electronic health record [18, 19].

Barriers to firearm safety counseling include lack of time, knowledge, resources, prompts in the medical record, and fear of a negative reaction. This highlights the importance of an intervention that (1) would provide education to providers on safe storage principles, gun safety laws, and how to approach the subject in a nonjudgmental way, and (2) would provide primary care offices with patient-facing resources and practical guidance for implementing counseling.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. Through partnerships with state physicians’ organizations and major health systems, we were able to achieve broad distribution of a cross-sectional survey. We rigorously developed the survey instrument to ensure an accurate and comprehensive assessment of current counseling practices. Additionally, we assessed knowledge of specific state firearm policy, which has not been previously studied and could inform an educational intervention tailored to Maine physicians.

A potential limitation of this study is participant selection bias. Physicians who chose to complete the study may rate firearm safety counseling as more important and may undertake it more often than physicians who did not complete the study. Due to the method of survey distribution and the overlapping membership between the participating organizations, we do not know how many individual physicians received the survey. This precludes us from reporting a rate of response. Further, we used a public REDCap to ensure anonymity, but it is possible that an individual participant could have completed the survey more than once. Lastly, a large health system located in a rural area of the state was not willing to distribute to their clinicians. However, physicians from this health system may have received the notification through other means of statewide distribution.

Conclusions

Maine physicians who completed a firearm safety counseling survey agreed that preventable firearm related injury or death is an important public health issue that physicians can positively affect. However, this study highlights significant differences in firearm safety counseling practices among Maine physicians based on rurality and years in practice. Respondents also reported a significant gap in knowledge of a recent state CAP law. Our results indicate that firearm safety counseling education tailored to Maine physicians is both needed and wanted. Next steps include development and distribution of an educational intervention that would aim to improve physician knowledge of Maine firearm safety policies and counseling strategies.

References

Goldstick, J. E., Cunningham, R. M., & Carter, P. M. (2022). Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 386(20), 1955–1956.

Roberts, B. K., Nofi, C. P., Cornell, E., Kapoor, S., Harrison, L., & Sathya, C. (2023). Trends and disparities in Firearm deaths among children. Pediatrics, 152(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-061296.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control (Published 2005). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Accessed March 13, 2023.

Schell, T. L., Peterson, S., Vegetabile, B. G., Scherling, A., Smart, R., & Morral, A. R. (2020). State-level estimates of Household Firearm Ownership. RAND Corporation.

LD 759 (2024). HP 564, Text and Status, 130th Legislature, First Special Session (maine.gov) Accessed June 3.

Butkus, R., Doherty, R., Bornstein, S. S., & For the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. (2018). Reducing firearm injuries and deaths in the United States: A position paper from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(10), 704–707.

Lee, L. K., Fleegler, E. W., Goyal, M. K., et al. (2022). Firearm-related injuries and deaths in children and youth: Injury Prevention and Harm Reduction. Pediatrics, 150(6), e2022060070.

Gun, Violence, & Prevention of (Position Paper). (2018). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/gun-violence.html. Accessed March 12, 2024.

Gun Violence and Safety; Statement of Policy (2023). https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/policy-and-position-statements/statements-of-policy. Accessed March 12, 2024.

Statement from the American Psychiatric Association on Firearm Violence (2022). https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/apa-statement-on-firearm-violence. Accessed March 12, 2024.

Abdallaha, H. O., & Kaufman, E. J. (2021). Before the bullets fly: The Physician’s role in preventing Firearm Injury. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 94, 147–152.

Betz, M. E., & Wintemute, G. J. (2015). Physician counseling on Firearm Safety: A New Kind of Cultural competence. Jama, 314(5), 449–450.

McCarthy, M. (2014). US internists call for public health approach to gun violence in US. Bmj, 348, g2796.

Sathya, C., & Kapoor, S. (2022). Universal Screening for Firearm Injury Risk Could Reduce Healthcare’s Hesistancy in Talking to Patients About Firearm Safety. Ann Surg Open ;3(1).

Hathi, S., & Sacks, C. A. (2019). #ThisIsOurLane: Incorporating Gun Violence Prevention into Clinical Care. Current Trauma Reports, 5(4), 169–173.

Butkus, R., & Weissman, A. (2014). Internists’ attitudes toward prevention of firearm injury. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(12), 821–827.

Rubin, N. (2019). ObGyn Physician Knowledge, Comfort, and Current Practices of Firearm Safety Counseling.

Thai, J. N., Saghir, H. A., Pokhrel, P., & Post, R. E. (2021). Perceptions and experiences of Family Physicians regarding Firearm Safety Counseling. Family Medicine, 53(3), 181–188.

Titus, S. J., Huo, L., Godwin, J., et al. (2022). Primary care physician and resident perceptions of gun safety counseling. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent, 35(4), 405–409.

von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). Strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bmj, 335(7624), 806–808.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Alexa Craig, Leah Seften, Wendy Craig, and the Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital Scholarship Academy for their support. In addition, we thank the Maine Chapters of the American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians, Maine Medical Association, ambulatory physician groups and residency programs at Maine Health and Central Maine Healthcare for their partnership.

Funding

No funding support was required for this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registry name and Registration Number

N/A.

Contributors Statements

Dr. Pleacher conceptualized and designed the study; reached out to professional organizations and hospital systems to recruit participants; supervised data collection, analysis, and interpretation; reviewed and revised the manuscript; and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Oppenheimer contributed to the design of the study, data collection, and interpretation of the results; drafted the initial manuscript; reviewed and revised the manuscript; and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Ms. Cutler conducted analysis and interpretation of data; critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Oppenheimer, J., Cutler, A. & Pleacher, K. Knowledge Gaps Identified in a Survey of Maine Physicians’ Firearm Safety Counseling Practices. J Community Health 49, 1101–1105 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01379-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01379-w