Abstract

The awareness of Human Papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted disease in the world, and the frequency of vaccination vary across countries. In Turkey, the rate of HPV vaccination is quite low even amongin women, and there is not much data on the frequency of vaccination among men. This study aimedto investigate the difference in knowledge and attitude between Turkish women who had HPV vaccination and those who did not. Women between 18 and 65 living in a province in the central region of Turkey were included. Participants (n = 856) were selected by snowball sampling and with an online questionnaire. The collected data were analyzed by the SPSS programme. Descriptive statistical analysis, chi-square test, T-test for independent samples and one-way ANOVA was used. 67.3% of the participants had heard of HPV and 55.4% had heard of the HPV vaccine. The HPV vaccination rate was 3.6%. The most important source of information for those who reported getting vaccinated on HPV was their family physician. Additionally, the HPV Knowledge Scale total scores of those who received information from family physicians and gynecologists were higher than the others. The most frequent reasons they cited for not getting vaccinated were a lack of information and not having the vaccine covered by social security. It is important to include it in the national vaccination scheme in order to increase the HPV vaccination rate in low-income countries such as Turkey. Also, these findings show the prominence of family physicians in public education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common cause of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) which causes morbidity and mortality in both sexes. An estimated 80% of sexually active people become infected with HPV at least once in lifetime. Infection with this virus is associated with anogenital cancers, including cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers [1, 2]. Approximately 44,000 HPV-associated cancers are diagnosed in the United States (US) each year. According to the GLOBOCAN 2020 report, there are 2532 new cases of cervical cancer and 1245 deaths annually in Turkey [3].

Currently, more than 200 genotypes of HPV are known to cause infections in humans, but only a few genotypes are associated with malignancy. HPV 16 is responsible for approximately 60% of invasive cervical cancers and 85% of HPV-related non-cervical cancers. HPV 18, one of the high-risk genotypes, is responsible for approximately 15% of cervical cancers [4]. The development of vaccines against HPV types that are particularly carcinogenic is a critical step in preventing cervical cancer. Currently, bivalent (HPV 16 and 18), quadrivalent (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18), and 9-valent (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58) vaccines are used. These vaccines protect against HPV 16 and 18, the most common cause of cervical cancer. Although the 9-valent vaccine was licensed in Turkey in 2019, it is not on the market yet. In the US, only the 9-valent HPV vaccine has been on the market since 2016 [5, 6]. Although the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) routinely recommends 11-12-year-olds, vaccination can be given at as early as 9 years. Catch-up (booster) vaccinations are recommended for males and females up to age 26 years [5]. It has been reported that, since 2006, when HPV vaccination was recommended, HPV infections have decreased significantly. In one study, an 86% decrease in HPV types due to the quadrivalent vaccine was observed during the ten years when the vaccination rate was 54% compared to before vaccination [7]. The HPV vaccine is included in the national vaccination calendar of 105 countries worldwide [8]. In Turkey, where the study is conducted, it is not yet included in the vaccination calendar. Individuals can get vaccinated by paying the optional fee. Vaccination rates are above 50% in most countries that include the HPV vaccine in their national vaccination calendars [9]. Since vaccination in Turkey depends on the population’s will, the vaccination rate can not be expected to increase without improving knowledge levels. This study aimed to investigate HPV knowledge and behaviors of women who have or have not had HPV vaccine.

Materials and methods

Study type

This study was a descriptive study.

Design

The universe of the study consists of women between 18 and 65 years living in Sivas. Sivas province is in the middle of Turkey. The population of this province amounts to 635,889, compared to 2020, and 317,118 of this population are women [10]. The universe for the study is estimated to be 317,118 people. The sample reported in the study was obtained using the snowball method. The snowball sampling is generally used for detecting hidden populations. Despite the cost and efficiency advantage of this method, a disadvantage is that it is a non-random selection procedure [11]. We chose to use this method because we planned to compare the data of people who had and did not have the HPV vaccine. This is because, according to the information we obtained from the literature review, the rate of HPV vaccination among women in Turkey is very low [12]. The researchers informed the individuals who met the criteria for participation in the study by phone and sent a survey link by smartphone application to those who agreed to participate. These individuals were then asked for contact information for individuals they knew would meet the criteria for participation, and they were contacted too. Proceeding in this way, we tried to reach as many people as possible within the sample collection period (April to June 2021) for the research.

Inclusion criteria for the study were being literate and using a smart mobile phone. Exclusion criteria for the study were cervical cancer diagnosis and refusal to participate in the study.

Information about the study was given in the phone call. Informed consent was obtained from the participants on the first page of the survey link sent to them.

Data collection tool

The data form used in the study consisted of 53 questions in total. The first 20 questions contain socio-demographic information, and the following 33 questions are related to the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Knowledge Scale [13, 14].

The HPV Knowledge Scale developed by Waller et al. [13] in 2013 includes 29-item three sub-dimensions and 6 independent items. Demir et al. [14] conducted its Turkish validity and reliability study in 2019. Two questions were excluded from the scale because they were not consistent with the current vaccination program in Turkey. The Cronbach α-value calculated in the Turkish validity study was 0.96. The sub-dimensions of the scale consisted of questions about the general level of knowledge about HPV, HPV screening tests, and the level of knowledge about the HPV vaccine. Three Likert-type responses can be given to the questions: ‘Yes,‘ ‘No,‘ and ‘I do not know.‘ Correct responses score 1 point, while incorrect responses and ‘I do not know’ score 0 points. A maximum of 33 points can be scored on the scale. A high score on the scale indicates a high level of knowledge about HPV.

The data collected were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) package program for Windows version 25. The adequacy of numerical data for normal distribution was assessed by analyzing the skewness and kurtosis coefficients. According to Huck [15], the skewness and kurtosis values should be between − 1 and + 1 for the data to have a normal distribution. First, a descriptive statistical analysis of the data was performed. Frequencies were calculated for categorical data and measures of central distribution (mean ± standard deviation) were calculated for numerical data. A chi-square test was used to compare categorical data. Having the means of normally distributed numerical data differing significantly between two independent groups was analyzed using the T-test for independent samples. The one-way ANOVA analyzed whether they differed significantly between more than two independent groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, with a 95% CI.

Permissions

Permission to use the scale in our study was obtained from Demir F. via email.

Results

A total of 856 individuals with a mean age of 33.8 ± 9.4 (min:18; max:65) participated in the study. Most women were married (77.6%) and sexually active (82.2%). Participants’ mean age of first sexual intercourse was 22.3 ± 4.2 (min:13; max:43). The demographic data of the participants are shown in Table 1.

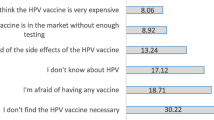

67.3% (n = 576) of the participants had heard of HPV and 55.4% (n = 474) had heard of the HPV vaccine. 3.6% (n = 31) of them had received HPV vaccination. Among the causes for not being vaccinated, the lack of knowledge (41.1%) and not having the vaccine covered by social security (26.3%) are the most common. The reasons why the participants were not vaccinated are given in Table 2.

6.9% (n = 59) of the participants had a family history of cervical cancer. 13.2% of participants (n = 113) stated that they did not know much about cervical cancer. Additionally, 12.3% (n = 105) of them did not know about STIs. The rates of those who obtain information from family physicians about both cervical cancer (46.6%) and STIs (56.7%) are higher than other sources. Also, young participants get informed from social media. The sources from which the participants obtained their knowledge about cervical cancer and STIs are presented in Table 3.

The sources of knowledge for those who reported getting vaccinated were their family physician (64.5%; n = 20), family and friends (38.7%; n = 12), gynecologist (32.3%; n = 10), and the Internet (25.8%; n = 8). The vaccination rate of those with higher income levels was significantly higher (p = 0.003). The income status of 90.3% (n = 28) of those vaccinated was above the minimum wage. There was a significant difference between HPV vaccination and a family history of cervical cancer (p < 0.001). 35.5% (n = 11) of those vaccinated had cervical cancer in family. There was a significant difference between vaccination and the mean age (p < 0.001). The mean age of those vaccinated was 23.1 ± 3.3 years.

49.8% (n = 426) of participants had a smear test taken. 14.8% (n = 127) were comfortable with talking about sex, which was partly comfortable for 36.9% (n = 316), and not at all comfortable for 48.2% (n = 413).

474 people who heard about HPV and the HPV vaccine responded to the full scale. The mean total scale score of these individuals was 13.6 ± 3.8. The mean scores of the subscales; the general HPV knowledge (n = 576) was 8.9 ± 2.5, the HPV testing knowledge (n = 576) was 1.7 ± 1.4, the HPV vaccination knowledge (n = 474) was 2.7 ± 1.5. Comparison of correct answers to scale items according to vaccination status is given in Table 4.

There was a significant difference between the scale scores of the participants and their educational status, sexual activity status, obtaining knowledge about cervical cancer from the family physician and gynecologists, and the status of HPV vaccination (p < 0.05). The participants’ total scale score compared with the varied characteristics is shown in Table 5.

Discussion

HPV infection is the most common sexually transmitted disease and the cause of substantial morbidity and mortality. We found that 67% of the participants had heard of HPV, and 55% had heard of the HPV vaccine. The vaccination rate was 3.6%. Participants indicated that they did not get vaccinated due to inadequate knowledge.

In studies conducted on women in Turkey over the past 10 years, the rate of those who had heard of HPV ranged from 9 to 57%, the rate of those who had heard of the HPV vaccine ranged from 2 to 74%, and the HPV vaccination rate ranged from 0.3 to 6% [12]. In most countries where HPV vaccination is part of the national vaccination program, vaccination rates exceed 50% [9]. Vaccination and screening programs are cost-effective. In Turkey, a cervical cancer-screening program based on cytology has been implemented since 2004, and HPV DNA was added to the screening in 2012. Data can be found in the literature showing that between 6% and 68% of the target population were screened [16]. In our study, it was concluded that 49% of participants participated in cervical cancer screening. We revealed that screening had no effect on the knowledge level, while vaccination significantly increased it. Screening programs, vaccination, and HPV knowledge levels are the three pillars of an effective fight against cervical cancer. However, only the screening program pillar is intact in Turkey.

HPV knowledge scale scores were significantly higher among those who reported obtaining knowledge from their family physician and gynecologist. Moreover, the most common source of information for those who had been vaccinated was family physicians. In the study by Kops et al., it was shown that increasing the frequency of visits to a family physician positively influenced knowledge levels [17]. Patients may feel more comfortable talking about sexuality with their family physician than with a physician they do not know. Family physicians are the first point of contact for people when it comes to their health. When assessing individuals, their physical, psychological, social, and environmental factors can be considered [18]. Family physicians are the ones who can best inform patients and clarify the reasons for their hesitation regarding the vaccine. At this point, it is believed that primary care-based interventions are more effective.

Nowadays, the Internet and the changes in social media have made their way into the health sector. People often use social media as a source of diagnosis and for treating diseases or to learn about health [19]. In a study on the impact of social media on HPV knowledge and attitudes toward the HPV vaccine, it was found to be associated with increased awareness and knowledge but had no impact on vaccination frequency [20]. Our study determined that obtaining information from social media did not influence knowledge levels. However, to research social media, people need to be aware. Among the participants in our study, it was determined that young people use the Internet more frequently to learn about cancer and STI.

It was remarkable to find that those with a university diploma and above had higher HPV knowledge in our study. In support of this finding, low educational level was associated with low knowledge in a multi-center study conducted by Marlow et al. in the US, UK, and Australia. In this study, the knowledge scale developed by Waller et al. was used to measure knowledge levels. When we compared the results with our data, our participants’ mean general HPV knowledge score was 8.9, while, in Marlow’s study, it was 9.2 points for women in the US, 8.5 points in the UK, and 8.3 points in Australia. It can be said that our participants’ general HPV knowledge scores were similar. The mean score for HPV vaccine knowledge in our study was 2.7, which was significantly lower than the results of other studies (USA: 4.1; UK: 4.1; Australia: 4.1) [21].

In Turkey, a single dose of HPV vaccine (Gardasil 4v®) costs an average of 700 TL ($47). It seems to be quite a challenge to get this vaccine for a country where the minimum wage is 2800 TL ($190) [22, 23]. The fact that the vaccine was not given for free was the most common reason for non-vaccination after lack of information. It is well known that the biggest barrier to vaccination in middle- and low-income countries is the inability to buy the vaccine [24]. It is noteworthy that the number of vaccinated women worldwide is much higher in high-income countries than in middle- and low-income countries [25]. Countries should include the HPV vaccine in their national vaccination programs and provide free transport to prevent this disparity.

98% of the population in Turkey is Muslim [26]. According to Islamic beliefs, any sexual intercourse (zina) outside the legal framework is a grave sin for both sexes [27]. Because of gender inequality, sex with more than one partner or premarital sex is acceptable by society for men, but not for women in Turkey [28, 29]. In a study conducted on university students in Turkey, the incidence of premarital sex was ten times higher in men than in women [30]. Higher risk of HPV infection in those with multiple sexual partners and transmission of infection through sexual intercourse was the responses that most participants reported as correct in the knowledge scale. In our study, among the reasons why women did not get vaccinated, the option of not feeling themselves at risk for STIs was notable. However, the prevalence of HPV in Turkey varies from 3 to 28% in different studies [31,32,33]. These results are not different from those in global literature. It would not be correct to attribute this result to a lack of knowledge. In a study conducted with physicians mothers, 87% of the participants thought that vaccination should be included in the vaccination calendar, while only half thought of vaccinating their child [34]. Even physicians with a high level of knowledge had reservations about having their children vaccinated. Further studies are needed to investigate the reasons for non-vaccination.

Conclusions

As a result, we determined that the most common reasons for non-vaccination were lack of information, not being able to get the vaccine for free, and not feeling at risk. We concluded that those who had obtained knowledge from their family physician and gynecologist had higher education and received the HPV vaccine had higher scale scores. While participants’ HPV knowledge was consistent with the literature, their knowledge about the HPV vaccine was weak. The importance of vaccination in the effective control of cervical cancer is evident. In this context, the vaccine should first be included in the national vaccination calendar to address inequities in accessing the vaccine. Subsequently, efforts should be made to improve knowledge and vaccination through primary care-based interventions.

Limitations

A snowball sampling was used for the study. The sample size was increased by approaching individuals who were known to the participants. Our results may not reflect the province of Sivas, which is our universe. Additionally, the reasons for non-vaccination could not be examined in detail because the knowledge about the HPV vaccine in the study was low.

Another limitation of the study was that it only focused on the vaccination status of women. HPV vaccines can be administered to both women and men. However, as the rate of vaccination among women was very low in the country where the study was conducted, men were not included. Our data can shed light on studies with large participation where men will be included.

Data availability statements

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Human papillomavirus vaccination. (2020). ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 809. Obstet Gynecol, 136(2), e15–e21. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004000

Küçükyıldız, I., & Yanık, A. (2020). The visible face of HPV, condyloma acuminata. The Journal of Gynecology-Obstetrics and Neonatology, 17(4), 615–620. https://doi.org/10.38136/jgon.671667

World Health Organization (2020). International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2020 Turkey Fact Sheets. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/792-turkey-fact-sheets.pdf

Schiffman, M., Doorbar, J., Wentzensen, N., de Sanjosé, S., Fakhry, C., Monk, B. J., Stanley, M. A., et al. (2016). Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2, 16086. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.86

Meites, E., Szilagyi, P. G., Chesson, H. W., Unger, E. R., Romero, J. R., & Markowitz, L. E. (2019). Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 68(32), 698–702. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3

TUIC Akademi. Türkiye’de HPV Aşı Uygulamaları: Toplumsal Cinsiyet Perspektifinden Bakış. Retrieved December 12 (2021). from https://www.tuicakademi.org/turkiyede-hpv-asi-uygulamalari-toplumsal-cinsiyet-perspektifinden-bakis/

McClung, N. M., Lewis, R. M., Gargano, J. W., Querec, T., Unger, E. R., & Markowitz, L. E. (2019). Declines in vaccine-type human papillomavirus prevalence in females across racial/ethnic groups: Data from a national survey. J Adolesc Health, 65(6), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.003

World Health Organization (2021). Existence of national HPV vaccination programme. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/existence-of-national-hpv-vaccination-programme

World Health Organization (2021). Girls aged 15 years old that received the recommended doses of HPV vaccine. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/girls-aged-15-years-old-that-received-the-recommended-doses-of-hpv-vaccine

Official site of Sivas Governorship of the Republic of Turkey (2021). Retrieved December 12, 2021, from http://www.sivas.gov.tr/ilcelerimiz

Johnson, T. P., & Snowball Sampling (2014). Sep 29. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. John Wiley & Sons Publishing. [Internet]

Özdemir, S., Akkaya, R., & Karaşahin, K. E. (2020). Analysis of community-based studies related with knowledge, awareness, attitude, and behaviors towards HPV and HPV vaccine published in Turkey: A systematic review. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc, 21(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2019.2019.0071

Waller, J., Ostini, R., Marlow, L. A., McCaffery, K., & Zimet, G. (2013). Validation of a measure of knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV) using item response theory and classical test theory. Prev Med, 56(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.10.028

Demir, F. (2019). Human papilloma virüsü (HPV) bilgi ölçeğinin Türkçe geçerlik ve güvenirliği. Sağlık Bilimleri Üniversitesi Gülhane Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü Halk Sağlığı Hemşireliği Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezDetay.jsp?id=PbXEf_W5BPYbJWlM7wlVgQ&no=3YBI6ZjejEkzQxqlVU-UQw

Huck, S. W. (2012). Reading statistics and research (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson

Küçükceran, H., Ağadayı, E., & Şentürk, H. (2020). Evaluation of the approaches of women registered to a family medicine unit in Ankara regarding having cervical cancer screening tests. Turkish Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 14(2), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.21763/tjfmpc.650940

Kops, N. L., Hohenberger, G. F., Bessel, M., Correia, Horvath, J. D., Domingues, C., Kalume, Maranhão, A. G., et al. (2019). Knowledge about HPV and vaccination among young adult men and women: Results of a national survey. Papillomavirus Res, 7, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2019.03.003

Cohen, G., & Cohen, M. (1985). Sexual health care in family medicine. Can Fam Physician, 31, 767–771

Zülfikar, H. (2014). The internet usage behaviour and access patterns of the patients to the health information on the internet. Florence Nightingale J Nurs, 22(1), 46–52

Ortiz, R. R., Smith, A., & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2019). A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 15(7–8), 1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1581543

Marlow, L. A., Zimet, G. D., McCaffery, K. J., Ostini, R., & Waller, J. (2013). Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination: an international comparison. Vaccine, 31(5), 763–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.083

Turkish Medication Directory. Gardasil Quadivalan Human Papillomavirus Recombinant Vaccine 2022 Price Information. Retrieved March 18 (2022). from https://www.ilacrehberi.com/v/gardasil-kuadivalan-human-papillomavirus-tip-6-11-b0f8/ilac-fiyati-2021/

Republic of Turkey Ministry of Labor and Social Security (2021). minimum wage. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://www.csgb.gov.tr/asgari-ucret/asgari-ucret-2021/

Vorsters, A., Arbyn, M., Baay, M., Bosch, X., de Sanjosé, S., Hanley, S., et al. (2017). Overcoming barriers in HPV vaccination and screening programs. Papillomavirus Res, 4, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2017.07.001

Bruni, L., Diaz, M., Barrionuevo-Rosas, L., Herrero, R., Bray, F., Bosch, F. X., et al. (2016). Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Glob Health, 4(7), e453–e463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30099-7

Hackett, C., Grim, B., Stonawski, M., Skirbekk, V., Potančoková, M., & Abel, G. (2012). The global religious landscape. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center

Hamdi, S. (2018). The impact of teachings on sexuality in Islam on HPV vaccine acceptability in the Middle East and North Africa region. J Epidemiol Glob Health, 7(Suppl 1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2018.02.003

Şimşek, H. (2011). Effects of gender inequalities on women’s reproductive health: The case of Turkey. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi, 25(2), 119–126

Kılıçer, B., Naşit, Gurcag, S., Civan, A., Akyıl, Y., & Prouty, A. M. (2021). Feminist family therapy in Turkey: Experiences of couple and family therapists. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 33(2), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2020.1848053

Eşsizoğlu, A., Yasan, A., Yildirim, E. A., Gurgen, F., & Ozkan, M. (2011). Double standard for traditional value of virginity and premarital sexuality in Turkey: a university students case. Women Health, 51(2), 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2011.553157

Kan, Ö., Görkem, Ü., Barış, A., Koçak, Ö., Toğrul, C., & Yıldırım, E. (2019). Evaluation of the frequency of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in women admitted to cancer early diagnosis and screening training centers (KETEM) and analysis of HPV genotypes. Turkish Bulletin of Hygiene & Experimental Biology, 76(2), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.5505/TurkHijyen.2018.47123

Hasbek, M., Çelik, C., Çabuk, A., & Bakıcı, M. Z. (2018). The frequency and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus in cervical specimens in Sivas Region. Türk Mikrobiyoloji Cemiyeti Dergisi, 48(3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.5222/TMCD.2018.199

Aydemir, Ö., Terzi, H. A., Köroğlu, M., Turan, G., Altındiş, M., & Karakeçe, E. (2020). Human papillomavirus positivity and genotype distribution in cervical samples. Turkish Bulletin of Hygiene & Experimental Biology, 77(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.5505/TurkHijyen.2019.68984

Döner, Güner, P., & Gözükara, K. H. (2019). Factors influencing decision - making for HPV vaccination of female doctors for their children. Ankara Medical Journal, 19(3), 539–549. https://doi.org/10.17098/amj.624511

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: EA, DK, SK; Methodology: EA, DK, SK; Formal analysis and investigation: EA, SK; Writing - original draft preparation: EA, DK; Writing - review and editing: EA, DK, SK; Resources: EA, DK; Supervision: EA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by Sivas Cumhuriyet University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee for Social and Human Sciences (approval date/number: 01.04.2021/E-60263016-050.06.04-29008).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agadayi, E., Karademir, D. & Karahan, S. Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors of Women who have or have not had human papillomavirus vaccine in Turkey about the Virus and the vaccine. J Community Health 47, 650–657 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01089-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01089-1