Abstract

Motivated by compelling, but scant, literature on high rates of breast cancer mortality among the United States Amish, a survey was conducted to examine mammography-seeking practices among Amish women. Inclusion criteria included age 40–70 years and membership of the Arthur, Illinois Amish community. Data were collected from this unique, socially isolated group through a mail questionnaire focusing on health history, mammography practices, and beliefs surrounding breast health. Sample mammography adherence and “ever mammogram” rates were compared with both the general population of the United States (U.S.) and other Amish communities in the U.S. Logistic regression on the “ever mammogram” variable showed that Amish women with knowledge of screening guidelines experienced an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 5.26 [confidence interval (CI) 1.79, 15.45] for mammography screening compared to those without that knowledge. Participants who believed nutrition/diet causes breast cancer experienced an OR of 4.27 (CI 1.39, 13.11) for mammography and those who believed physical injury caused breast cancer had an OR of 3.86 (CI 1.24, 12.04) compared to women who do not hold these beliefs. Future research is needed to confirm and extend these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a growing problem in the United States (U.S.). From the 1940’s through the 2000’s, the incidence increased over 1 % annually [1]. Breast cancer affects all racial groups and is currently the most common cancer across women in the U.S. In the U.S. breast cancer incidence for white women was 107 per 100,000 in 1975 and rose to 126 per 100,000 by 2005 [2]. Similarly, breast cancer incidence rates in Black women rose from 94 per 100,000 in 1975 to 120.5 per 100,000 in 2009 [2]. In addition to affecting racial and ethnic minorities, breast cancer also burdens female members of ethnocultural and insular religious groups, which are effectively minority groups themselves [3, 4]. Like racial and ethnic minorities, groups such as Mormons, Hutterites, Seventh-Day Adventists, Jat Hindus, ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Old Order Amish not only share cancer concerns with the general population but, as research suggests, also may experience screening and treatment barriers and lifestyle factors unique to their population [5]. This study focuses on the breast cancer burden and barriers specific to the Old Order Amish.

There is one prior study of breast cancer detection in women of the Amish faith, and that study suggests they have a much lower rate of mammography than the average U.S. woman [4]. The lack of breast cancer screening leads to an increased risk for late detection of breast cancers and a higher rate of breast cancer mortality than found in the general population [5, 6]. The Amish have unique breast cancer screening barriers, health perspectives, and religious ideas, each of which vary slightly from one settlement to the next. Further, women living in rural areas seek mammography less often, have lower socioeconomic status, and live farther from healthcare facilities than their urban counterparts [7, 8]. This study aims to explain the disparity between the Amish and the rest of the U.S. population with respect to breast cancer screening behavior.

Many risk factors affect women’s susceptibility to breast cancer, including age, genetics, Body Mass Index (BMI), parity, use of oral contraceptives, and age at first birth [9]. One of the biggest risk factors for breast cancer is lack of screening. The mammogram, one of several screening options, was ordered by U.S. physicians 19.3 million times in 2006 [10]. In 2010, 67.1 % of American women over age 40 had received a mammogram in the prior 2 years [11].

Scientific evidence for the benefits of mammography continues to grow. For example, mammography has been shown to detect tumors at an earlier stage than they would otherwise be detected, improving survival odds [12]. Also, women whose breast cancer is first detected by mammography survive longer, on average, than those whose cancer was detected by other forms of breast cancer screening, such as clinical breast exam or self-exam [13].

Guidelines for recommended mammography frequency vary among agencies and organizations [14, 15]. In 2007, the American College of Physicians, advocated that women’s screening frequency between the ages of 40–49 should be determined on an individual basis by their physician [15]. On the other hand, the U.S. Preventive Health Task Force and National Cancer Institute recommend that women over age 40 should obtain a mammogram every 2 years or more frequently if they are at an increased risk [14]. A third guideline, issued by the American Cancer Society, recommends annual mammography for women over age 40. The latter two guidelines (biannual and annual) will be examined in this study.

Setting

Arthur, Illinois, is a small, rural community in central Illinois. The “Arthur Amish” community extends into several other small, neighboring towns, including Arcola, Atwood, Humboldt, Lovington, Sullivan, and Tuscola [16]. There are several reasons why the Arthur Amish community is a desirable study sample. None of the limited research on breast cancer and mammography in the Amish has been conducted in Illinois; therefore, the Arthur Amish community can provide comparison data for other Amish women as well as U.S. women as a whole.

Amish Screening Barriers

Amish women experience a unique set of barriers to breast cancer screening. One is access to both health care and health insurance. Related to access to care, Old Order Amish utilize horse and buggy as a primary mode of long distance transportation and bicycles or foot travel for traveling shorter distances [17]. The Amish refrain from automobile use in an effort to foster a sense of community rather than individualism, and may shun members who use automobiles [18]. They believe the autonomy afforded by individual automobile use encourages self-centeredness [19]. Though there are several general practice physicians within a distance suitable for travel by buggy, most Amish in the Arthur area travel either to Champaign-Urbana, IL (a distance of approximately 35 miles), Mattoon, IL (35 miles), or Decatur, IL (35 miles) for specialized health care needs such as gynecological exams and screenings. Buggy travel is rarely used for such distances; rather, a driver could be paid to take them.in his or her vehicle.

Another barrier is communication. Health care appointments are difficult to schedule by mail, and the Amish are only allowed phone calls outside the home in special situations.

Economics is yet another barrier. Because the vast majority of Amish people are self-employed and have lower than average earning power, purchasing health insurance is often not feasible [20]. In a cross-sectional study using the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (BRFS), Levinson et al. [20] found that about 66 % of the Amish women from the study sample were homemakers and only 5.3 % of men reported making more than $25,000 annually as compared to 24.3 % of non-Amish men, although 59.0 % of Amish men were unsure of their annual income [20]. Household size also adversely affects the Amish’s ability to purchase health insurance, as the average Amish family has more than five children [5, 21, 22]. This lack of formal health insurance translates to a lack of preventive care practices like mammography. Further, while there are free screening clinics, the Amish resist accepting free or charitable services, including Medicare and Medicaid [6]. Foregoing such measures may delay diagnosis and, as the disease advances, treatment becomes more costly and the patient’s chances of recovery less likely [9].

In this context, we compare rates of mammography between Arthur, Illinois, Amish women and both the general U.S. population and other Amish communities. We also used logistic regression modeling to explore possible explanations for the differences in mammography rates.

Methodology

Selection Process

This research is approved by University of Illinois’ Institutional Review Board. Selection criteria were threefold: female, self-identification as an accepted member of the Arthur, Illinois, Amish community, and a birth date between January 1, 1938 and December 31, 1968 (approximately age 40–70). Two sampling frames were used in the selection process: the 2003 Directory of the Illinois Amish and the Illinois Department on Aging Caregiver Support Program. The Directory served as the primary source of participant information, and the support program was supplemental, to capture any eligible community members whose directory information was no longer accurate at the time of sampling. The current study was performed in 2009 using the most current version of the directory.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used for this project was derived from Champion’s Health Belief Scale and another previously validated in an Ohio Amish community [4], which was itself derived from Champion’s Health Belief Scale. Because of the latter’s use in Ohio Amish communities, the questionnaire is considered validated to some degree, which is why a closely adapted version is used in the current project. The questionnaire is used to gauge the level of need for mammography services, just as it was used in the Ohio Amish samples.

The survey instrument used for primary data collection has three sections. Part one focuses on personal mammography history and future plans for mammography seeking. Part two centers around personal beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge of breast cancer causes, treatments, and prevalence. In this section, participants are urged to choose the best answer if they are unsure of the correct choice. The purpose of part two is to obtain information about participants’ health literacy. The third part includes personal and family breast cancer history, and other relevant variables such as breastfeeding and oral contraception history, number of children, and marital and employment status.

The questionnaire was mailed to all women in the 2003 Amish Illinois Directory who met the three inclusion criteria (n = 351). The initial response rate was 37 %, and a follow-up letter was subsequently sent to non-respondents.

The Caregiver Support Program sampling frame yielded two participants. The program director reported that Amish program participants ultimately opted not to participate overall. The director reported the Amish women to be uneasy about disclosure of identity, despite assurances of confidentiality. Only two community members participated, and those two would not provide identifying information (name and address). Because of the lack of address, these two were placed in an “Unspecified” town category.

Table 1 shows crude and adjusted response rates. Surveys were coded as “Undeliverable” if the participant no longer lived at the address, if the postal carrier was unable to locate the address, or if the address no longer existed. In these cases, the participant did not actively refuse to participate. Therefore, the total number mailed does not include the number of undeliverable surveys. Similarly, an individual was placed into the “Deceased” category when a friend or family member of the potential participant returned a note stating that the individual had passed away. Since the addressee did not actively decline participation, the number of deceased was subtracted from the total number of mailings in the adjusted response rate calculation. Summarily, adjusted response rates were calculated as follows: (number of returned surveys)/(total surveys mailed—deceased—undeliverable). Adjusted response rates range from 33.0–52.0 %, with a total response rate of 43.0 %. Adjusting the response rates resulted in a net response rate increase of 3.0 %. Table 1 also includes mean respondent age. The overall mean sample age is 0.6 years older than the overall mean population age.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were first conducted to provide an overarching picture of the population and sample through basic frequencies and rates. Chi square tests assisted with model development. Binary logistic regression was used to model the association between respondent characteristics and their mammography history. Dependent variables were biannual mammography adherence and ever mammogram. Chi square tests assisted in model development before forward stepwise logistic regression was conducted. Statistical Package for Social Sciences, v17.0, was used for all analyses (Chicago: SPSS Inc.).

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for demographic and behavioral variables of interest. The sample’s characteristics tend to be homogeneous in terms of education, number of children born, and marital status, in keeping with the Amish population as a whole.

Mean grade completed is 8th, with an average of 5.3 births per woman. About 25 % have ever taken oral contraceptives and 10.6 % have never married. All women sampled had heard of a mammogram, but only about half had ever had one, as compared with about 90.0 % for all Illinois women over age 40 [23].

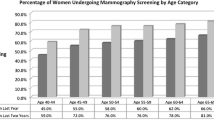

Comparisons of Mammography-Seeking Practices Between Amish and U.S. Women

We compare both mammography adherence and whether women have ever had a mammogram between our Amish sample and the U.S. general population. The recommendation for biannual mammography will be used in comparing mammography rates between Amish and U.S. women, due to data availability.

In 2004, Illinois’ ever mammogram rate was 90.1 % for women over age 40 [23] compared to the national average of 74.3 % for all women age 18 and over in the same year [24]. Since mammography is typically recommended only after age 40, the national rate is undoubtedly lower than it would be for a 40–70 age range [25, 26]. Nevertheless, the total 53.1 % ever mammogram rate from the Arthur Amish study sample falls is much lower than the Illinois 40–70 ever mammogram rate of 90.1 %.

We also compared the Amish sample to county-level BRFSS data. The Arthur Amish community spans four Illinois counties: Douglas, Moultrie, Coles, and Piatt. The combined ever mammogram rate of all four counties for 2004–2009 is 64.0 %, as compared to the Arthur Amish counterpart, with a comparison rate of 53.1 % [23]. Amish are typically excluded from the BRFSS because it is administered by phone, so the BRFSS ever mammogram rate provides a non-Amish local comparison group.

In 2010, 67.1 % of U.S. women over 40 reported having a mammogram within the past 2 years. In other words, 67.1 % were compliant with standard mammography recommendations [11]. The percentage in 2010 was consistent with previous years: 67.8 % in 2005, 69.7 % in 2003 and 70.4 % in 2000 [11]. Our sample’s mammography adherence rate was only 40.0 %.

Comparisons of Mammography-Seeking Practices Among Amish Communities

In 2000, researchers surveyed 90 Ohio Amish women, finding that 45 % had ever had a mammogram and 27 % had received a mammogram within the past year [27]. The same researchers collected mammography data on a sample of 344 Amish women from the largest existing U.S. Amish community, located in Ohio [28]. Sixty percent of the sample reported ever having a mammogram, whereas 28 % reported having one within the past year. The Illinois Amish community from this study’s 53.1 % “ever mammogram” rate falls between the two Ohio communities. Our sample’s 1-year mammography adherence rate was 20.2 %, compared to the Ohio samples’ rates of 28.0 and 27.0 %. This comparison demonstrates that Arthur Amish women obtain similar or fewer mammograms than other Amish communities.

Regression Analyses

Two dependent variables were analyzed in this study: biannual mammography adherence and ever mammogram. Chi square tests were conducted to describe sample characteristics and assist in logistic regression model development. Table 3 summarizes the significant associations from bivariate analysis (p < 0.05).

Eleven independent variables were included in the logistic regression model with “ever mammogram” as the dependent variable. Two variables were excluded because of wide confidence intervals: “Perceived B.C. Cause: X-rays/Radiation” (95 % CI 1.78, 30.32) and “Perceived B.C. Cause: Environment” (1.49, 163.04).

Table 4 displays the final model of the logistic regression. Results indicate that respondents who believe a woman over 40 should have a mammogram every 1–2 years were about 5 (95 % CI 1.79, 15.45) times more likely to have ever had a mammogram than those who selected a response inconsistent with common screening recommendations. Women who cited “Nutrition/Diet” as a cause of breast cancer were about four times (95 % CI 1.39, 13.11) more likely to have ever had a mammogram than those who did not select this option. The older age group (55–70 years) was more likely to have had a mammogram than the younger group. All variables in the model are significant at the p < 0.05 level.

Discussion

Mammography is one step that women can take to protect themselves from breast cancer mortality. Recommended guidelines for mammography vary slightly from one organization to another, but the National Cancer Institute recommends one mammogram every 1–2 years after age 40. More frequent mammography may be prescribed if a woman is at elevated risk due to factors such as family history, personal history, menstrual history, breast density, or BMI [26]. Mammography adherence rates in the U.S. varied from 63 to 70 % in 2003 across racial groups [29]. Although there is room for improvement, the majority of American women (63–70 %) adhere to at least one of these guidelines.

Academic literature on breast cancer or mammography in the Amish is scarce. However, the few existing studies show Amish breast cancer mortality rates to be among the highest in the world [5]. Thomas [4], who has conducted multiple studies in Ohio Amish communities, found the Amish breast cancer incidence to be lower than in the general population, but again saw very elevated breast cancer mortality rates. The Ohio Amish also displayed significantly lower mammography rates than the general U.S. female population. Heightened breast cancer and mammography education in Amish communities could potentially increase mammography compliance and early breast cancer detection, thereby saving or prolonging lives.

A total of 351 questionnaires were distributed via mail, with an adjusted response rate of 43 % for these data. Mammography rates in this study differed from the general population and from other Amish communities. In our sample, 31.0 % of respondents obtained a mammogram within 2 years prior to completing the survey, compared to the general population rate of 66.8 % [10]. The ever mammogram rate for this study sample was 53.1 %, as compared to the Illinois state rate of 90.1 %.

Logistic regression analyses evaluated ever mammogram and mammography adherence outcomes. In comparison to an Ohio Amish sample, 53.1 % of our sample ever had a mammogram compared to 60.0 % among Ohio Amish (Ohio comparison group 1) and 45.0 % (Ohio comparison group 2), illustrating that our sample’s low rates are similar to those for the Ohio Amish.

This study is an important step in accruing more academic literature in the area of breast cancer and mammography among Amish women. To our knowledge, only one other state, Ohio, has had breast cancer and mammography data collected among its Amish communities. This study contributes to extant literature and provides motivation for others interested in Amish breast cancer screening. Data collection in insular religious communities can be daunting, and this study provides a model for other researchers to gain access to the Amish community by approaching them in a respectful and culturally appropriate manner.

Results of this study are largely in keeping with the existing literature. In our study, the following three barriers to mammography were reported most frequently: financial cost or lack of insurance (35.0 %); too much trouble or simply will not get around to it (22.4 %); and because there is no current problem with the breasts, there is no need for a mammogram (20.3 %). These results are consistent with the literature on Amish income/insurance status and preventive medicine beliefs [6, 21, 30]. Only 8.4 % of our sample cited “Transportation” as a mammography barrier, despite the fact that almost all of the women in this sample who had obtained a mammogram had traveled 70 miles round trip, without the use of a personal automobile. The implications of this finding are somewhat unclear and more research is required. One possible explanation is that women of the Arthur community have a system of transportation such as organized carpooling or volunteer drivers.

With respect to perceived breast cancer causes, the most common response was “Genetics/Heredity” (49.0 %). Genetics can increase risk breast cancer risk, but the risk attributable to genetics is only 5–10 % of total risk [31]. Another commonly reported perceived breast cancer cause was “X-rays/Radiation” (21.7 %), which is also the most significant variable in this study with respect to mammography adherence, with a Chi square value of 8.116 (p = 0.004). Although X-rays and/or radiation are a legitimate risk factor for breast cancer in cases of extreme overexposure, such intense concerns about the amount of radiation conveyed by regular mammography may indicate reduced health literacy [22, 32].

Over 36.0 % of women from our sample believe mammograms are useful “only when she has a pain or lump in her breast.” The belief that mammography should only be sought when a problem arises may again indicate inadequate health literacy, not only about breast cancer itself but also about the purposes of regular screening. The “No need/No problems with breasts” and “Only when she has a pain or lump in her breast” responses also tie strongly to Amish preventive medicine beliefs. The Amish typically reserve health care for medical issues that cause problems in their everyday lives [21]. Overall, regular mammography is not viewed as worthwhile unless used to treat an existing problem with the female breast. In contrast, only 0.8 % of the sample believed that there is “No benefit in finding cancer early,” which is a puzzling response due its indirect endorsement of preventive medicine. The Amish acknowledge the benefit of finding cancer early, yet maintain that mammography should only be used once a problem becomes evident. This contradiction may point to a need for more education.

Regression analyses identified factors behind participants’ breast cancer screening behavior. Participants who were knowledgeable about mammography guidelines were more likely to have ever had a mammogram, reinforcing the idea that increased health literacy potentiates screening. Conversely, women who had either no perception or an incorrect perception about mammography guidelines were less likely to have ever had one mammogram or to be compliant with guidelines. The finding that screening is positively associated with the belief that Nutrition/Diet is a perceived breast cancer cause was unexpected. The questionnaire contained no other items pertaining to the Amish diet or cultural perspective on food, but it is possible that the association is due to healthy behaviors being associated with both concern with diet and the probability of screening. Relatedly, Thomas [4] administered a survey containing a section on nutrition and diet. Thomas measured women’s diet in “dietary compliance” and found that higher dietary compliance was positively correlated with not only breast self-exam adherence but also clinical breast exam adherence [4]. In further study, a dietary component should be included in the questionnaire.

Women who cited physical injury as a perceived breast cancer cause were also more likely to have ever had a mammogram. Like “Nutrition/Diet,” this variable’s significance was unexpected. A literature review did not reveal evidence of Amish beliefs about breast injury, but the finding raises health literacy issues and highlights the need for breast health education. It is possible that if women feel that they have had a breast injury or trauma of some sort, they fear cancer occurrence and seek screening. Age was also significant in regression analysis (categories 40–54 and 55–70), with women in the older category being more likely to have ever had a mammogram.

One strength of the study is the survey method used with this unique, socially isolated group. Amish communities can be difficult to access from a research perspective, so the information that they willingly provided for this project is valuable. A limitation of the study is response rate (43.0 %), which was less than desirable for the Directory sampling frame, and almost zero for the Caregiver Support Program sampling frame. However, in the context of this study population, a response rate of 43.0 % may be acceptable. Research with other Amish communities has been conducted with a smaller sample size than ours (n = 143). Thomas [4] administered a questionnaire to 90 Ohio Amish women. The current study also offered no tangible incentive, which could potentially have improved the response rate. Further, studies of non-response to health surveys indicate that non-respondents are less likely to use health services, so the low screening rates reported here might be overstated [33].

Recent data indicate that the U.S. is making progress in the fight against breast cancer. Overall, U.S. mammography rates have risen significantly over the past 30 years [34]. Mammography and breast cancer literacy are also increasing in many minority groups [29]. Organizations like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Cancer Society have made breast cancer, along with other health issues, less frightening and mysterious through their multimedia educational campaigns. Nonetheless, continued research on breast cancer and mammography in the general U.S. population is advisable. If approximately 65.0 % of U.S. women are in adherence with mammography guidelines, then 35.0 % are not [29]. Both the U.S. government and health promotion organizations have a responsibility to continue allocating resources and research efforts to further raise mammography rates for U.S. women.

Despite the progress made by most of the nation, some demographics are largely excluded when it comes to breast cancer screening and general awareness. The Amish are one example. Preexisting research and data from this study agree that Amish rates of mammography, as well as ideas about mammography, lag far behind the rest of the U.S. population. This study revealed that adherence rates of Illinois Amish women are only about half that of the average American woman. Other Amish groups exhibit very low mammography rates as compared to the general population as well. Ever mammogram percentages would be expected to be much higher than adherence rates in any comparison, but such is not the case between the Amish and the average American woman.

Based on our regression analysis, five factors should be considered candidates for future research: knowledge of mammography guidelines, perceived breast cancer causes “Nutrition/Diet” and “Physical Injury”, and age category, as relatively younger Amish women were more likely to have had a mammogram, suggesting that mammography rates may be rising over time. Stage of diagnosis also warrants further investigation. High breast cancer mortality is the most serious Amish breast cancer issue according to extant studies, but the reasons remain unclear. Whether elevated mortality is due to low screening rates, late-stage diagnosis, lack of treatment, or some combination of these, is unknown. The problem of breast cancer mortality among Amish women should be a primary research focus at this time. It is timely and consequential, and further investigation has the potential to save many lives.

Abbreviations

- U.S.:

-

United States

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral risk factor surveillance system

References

American Cancer Society. (2009). Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2009/index.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention United States Cancer Statistics (USCS). (2009). Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/cancersbyraceandethnicity.aspx.

Shatenstein, B., & Ghadirian, P. (1997). Influences on diet, health behaviours and their outcome in select ethnocultural and religious groups. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, CA), 14, 223–230.

Thomas, M. K. (2007). The relationship between objective risk factors associated with breast cancer and breast cancer screening utilization among Amish women. Minneapolis: Walden University

Troyer, H. (1988). Review of cancer among 4 religious sects: Evidence that life-styles are distinctive sets of risk factors. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 26, 1007–1017.

Documet, P., et al. (2008). Perspectives of African American, Amish, Appalachian and Latina women on breast and cervical cancer screening: Implications for cultural competence. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19, 56–74.

Casey, M. M., Call, K. T., & Klingner, J. M. (2001). Are rural residents less likely to obtain recommended preventive healthcare services? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 21, 182–188.

Carney, P. A., et al. (2012). Influence of health insurance coverage on breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening in rural primary care settings. Cancer, 118, 6217–6225.

American Cancer Society. (2009). What are the risk factors for breast cancer? Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/detailedguide/breast-cancer-risk-factors.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Mammography Breast Cancer. (2009). Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/mammography.htm.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2010). Health, United States, 2010. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Elkin, E. B., Hudis, C., Begg, C. B. & Schrag, D. (2005). The effect of changes in tumor size on breast carcinoma survival in the U.S.: 1975–1999. Cancer 104, 1149–1157.

Shen, Y., et al. (2005). Role of detection method in predicting breast cancer survival: Analysis of randomized screening trials. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 97, 1195–1203.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Screening. March 24, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/screening.htm.

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. (2007). New screening mammography guidelines affect women in their forties.

Schlabach, L. Directory of the Illinois Amish. (JKL Services).

Beachy, A., Hershberger, E., Davidhizar, R., & Giger, J. (1997). Cultural implications for nursing care of the Amish. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 4, 118-26-8.

Hostetler, J. A. (1993). Amish society. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Kraybill, D. B. (1990). The riddle of Amish culture. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Levinson, R., Fuchs, J., Stoddard, R., Jones, D., & Mullet, M. (1989). Behavioral risk factors in an Amish community. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 5, 150–156.

Guyther, J. (1979). Medical attitudes of the Amish. Maryland State Medical Journal, 28, 40–41.

Kraybill, D. B. (1989). The puzzles of Amish life. Surrey: Good Books.

Illinois Department of Public Health. Illinois Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. (2009). Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://app.idph.state.il.us/brfss/default.asp.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Use of Mammograms Among Women Aged >40 Years—United States, 2000–2005. Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5603a1.htm.

American Cancer Society. (2009). Mammograms and Other Breast Imaging Procedures. Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://www.cancer.org/healthy/findcancerearly/examandtestdescriptions/mammogramsandotherbreastimagingprocedures/mammograms-and-other-breast-imaging-procedures-toc.

National Cancer Institute. (2015). Mammograms. National Cancer Institute. Accessed March 24, 2015, from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast/mammograms-fact-sheet.

Thomas, M. K. & Menon, U. (2001). Predictors of breast cancer screening utilization among Amish women.

Menon, U. & Thomas, M. K. (2006). Breast Cancer knowledge and beliefs among Amish women.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Mammography. Accessed December 7, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/screening.htm.

Girod, J. (2002). A sustainable medicine: Lessons from the old order Amish. The Journal of Medical Humanities, 23, 31–42.

Katapodi, M. C., & Aouizerat, B. E. (2005). Do women in the community recognize hereditary and sporadic breast cancer risk factors? Oncology Nursing Forum, 32, 617–623.

Adams, C., & Leverland, M. (1986). The effects of religious beliefs on the health care practices of the Amish. The Nurse Practitioner, 11, 58–60.

Etter, J. F., & Perneger, T. V. (1997). Analysis of non-response bias in a mailed health survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50, 1123–1128.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2009). Health, United States, 2008. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geiger, S.D., Grigsby-Toussaint, D. Mammography-Seeking Practices of Central Illinois Amish Women. J Community Health 42, 369–376 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0265-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0265-8