Abstract

The risk for suicidal behaviors including suicide ideations and attempts among individuals with gambling disorder (IWGDs) is high compared to the general population. Little is known about the interplay of mood disorders, alcohol use disorders, and suicidal behaviors among IWGDs. The study aimed to determine the prevalence, sociodemographic characteristics, risky behaviors, mental health disorders, and alcohol use disorders associated with suicide behaviors among IWGDs. Studies published between January 1 1995 and September 1 2022 were obtained from following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases. PECOS (population, exposures, comparison, outcome, and study design) criteria were used for selecting studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for assessing risk of bias and rated each study in terms of exposure, outcome, and comparability. After initial assessment of 10,243 papers, a total of 39 studies met the eligibility criteria. Among IWGDs, the findings indicated a life-time pooled prevalence rate of 31% for suicide ideations (95% CI, 23–39%), 17% for suicide plans (95% CI, 0–34%), and 16% for suicide attempts (95% CI, 12–20%). Generally, suicide ideations among IWGDs were associated with having any financial debt and having chronic physical illnesses, as well as experiencing depression, mood disorders, and alcohol use disorders. Suicide attempts among IWGDs were associated with being older and having a childhood history of sexual abuse, as well as experiencing depression, mood disorders and alcohol use disorders. Interventions can help to facilitate seeking support among IWGDs by de-stigmatizing mental health disorders as well as improving the quality of care presented to individuals with psychiatric conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Often viewed as a behavioral addiction, gambling disorder (GD) is defined as a loss of control over gambling that becomes the sole attraction for the individual, compromising all other interests and activities and that leads to major socio-economic and familial harms (Guillou-Landreat et al., 2016). Among individuals with gambling disorder (IWGDs), co-occurring mental health conditions, such as substance use disorder and mood disorders, are common (Dowling et al., 2015; Ronzitti et al., 2017). Previous research suggests a 20% lifetime suicide attempt rate among IWGDs. Consequently, suicidality requires the most attention among various other harms associated with gambling (Moghaddam et al., 2015). In addition, IWGDs are at a 3.4 times higher risk for suicide attempts, relative to the general population (Newman & Thompson, 2003). Lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (suicidal behaviors) are reported by IWGDs to be as high as 17–48% and 9–31%, respectively (Komoto, 2014; Thon et al., 2014).

A significant body of literature has examined suicidal behaviors among IWGDs but has provided inconsistent and contradictory findings. According to the literature, numerous sociodemographic characteristics, risky behaviors, and mental health disorders are associated with suicidality among IWGDs. However, there are data discrepancies in this regard. For instance, being female (Bischof et al., 2015, 2016; Thon et al., 2014) and being unemployed (Komoto, 2014; Thon et al., 2014) were found to be associated with suicidality in some studies, but not in others (Black et al., 2015; Weinstock et al., 2014). One study reported no significant relationship between marital status and suicidal ideation among IWGDs (Weinstock et al., 2014). However, the results of another study indicated that lifetime suicidal ideation and being divorced were positively and significantly associated (Ledgerwood & Petry, 2004). The most prevalent comorbid conditions among IWGDs include substance use disorders and mood disorders (Bischof et al., 2015, 2016; Petry & Kiluk, 2002). The total amount of financial debts and losses (Battersby et al., 2006; Bischof et al., 2016; Ledgerwood et al., 2005), as well as the severity of problem gambling (Battersby et al., 2006; Black et al., 2015; Ledgerwood & Petry, 2004) also appear to be associated with suicidality.

There are over 20 different models and theories regarding suicide (Benson et al., 2016; John Mann et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2008; Leung et al., 2016; O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018; Rudd, 2000; Soloff et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2011) and most of these can be categorized as either (i) traditional/predictive models or (ii) complex models (De Beurs et al., 2019), Moreover, some studies have designed models of suicidal behavior to categorize different variables associated with suicide (De Beurs et al., 2019; Díaz-Oliván et al., 2021). Predictive models result in a risk score considering key factors using statistical analysis (Díaz-Oliván et al., 2021). Complex theories aim to explain the interaction of risk factors associated with suicide, and highlight the complex interaction between biological, environmental, psychological, and social factors (Klonsky et al., 2016; O'Connor & Nock, 2014). Moreover, complex models may be more efficient than predictive models since current theories often consider a specific domain such as psychological, biological or environmental factors (Díaz-Oliván et al., 2021). These interactions (among others) include failure, being caught in a trap, and impulsivity related to motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior (O’Connor & Portzky, 2018; O'Connor & Nock, 2014). The aforementioned factors have high interaction with each other and on the development of suicide behavior (De Beurs et al., 2019; O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018).

Although the relationship between suicidal behaviors and IWGDs has been explored in some epidemiological and clinical studies, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no meta-analysis study examining prevalence of suicidal behaviors including suicide ideations and attempts and their correlates with sociodemographic characteristics, risky behaviors, mental health disorders, and alcohol use disorders among IWGDs. Also, few studies have focused on the impact of alcohol use disorders and mood disorders with respect to suicidal behaviors among IWGDs. Therefore, the present systematic review and meta-analysis study aimed to determine the prevalence, sociodemographic characteristics, risky behaviors, mental health disorders, and alcohol use disorders associated with suicide behaviors among IWGDs.

Methods

Search Strategy

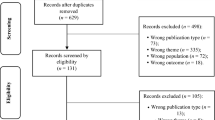

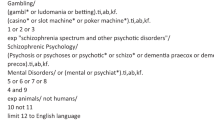

The present study was conducted based on the Protocols of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Bayani et al., 2020; Bayat et al., 2020; Rezaei et al., 2020). Two independent authors (RM and BA) reviewed studies published between January 1 1995 and September 1 2022 which were obtained from following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Library All fields within records and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) were used in the aforementioned databases. The initial keywords of the search strategy were “(suicide ideations), (suicide plan), (suicide attempts), (suicidal behaviors), (gambling), (pathological gambling), (gambling disorders)”. Finally, bibliography lists of the included papers were manually reviewed for further relevant studies (Supplementary File 1).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

PECOS (population, exposures, comparison, outcome, and study design) criteria were used for selecting studies: “population”: only IWGDs; the “exposures”: positive and protective associations of the sociodemographic characteristics, risky behaviors, mental health disorders, and alcohol use disorders among IWGDs on lifetime suicidal behaviors; “comparison” group: IWGDs without any lifetime suicidal behaviors; “outcomes”: lifetime suicide ideations or suicide attempts among IWGDs; and “study design”: integrated cross-sectional, cohort or case–control studies. Studies such as qualitative studies, secondary studies without primary data, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis were excluded. Also, literature with major heterogeneity or outcome variations from the study groups were excluded.

Screening and Data Extraction

Paper references were managed using EndNote X7 software (Thomson Reuters). First, the duplications (89% agreement) were removed. The agreement between the reviewers (unweighted kappa) was assessed. The level of agreements including poor, slight, fair, moderate, substantial, or almost perfect level were represented by the values 0, 01–0.02, 0.021–0.04, 0.041–0.06, 0.061–0.08, or 0.081–1.00, respectively (Landis & Koch, 1977). Any disagreements were resolved by a third member of the research team (EA). Second, the same authors (RM and BA) reviewed the full texts of the papers, considering the PECOS criteria and the exclusion criteria. Data management was carried out utilizing Microsoft Excel software. The following features were extracted from the reviewed studies: publication year, the study location, the first author’s name, country, the design of the study, the study sample size, data collection source, diagnostic criteria used to assess key variables, key statistical data, and any outcome measures.

Quality Appraisal of Studies

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for quality appraisal purposes (Ghiasvand et al., 2019, 2020; Peterson et al., 2011). The NOS contains three domains of (i) selection (three items for cross-sectional studies; four items for cohort and case control studies), (ii) comparability (one item for both cross sectional studies and cohort and case control studies), and (iii) exposure/outcome (one item for cross-sectional studies and three items for cohort and case control studies). If a study met each criterion, it got a score or star. A maximum score of 5 was possible for cross-sectional and a maximum score of 8 was possible for the quality of cohort/ case–control studies were obtained. Cross-sectional studies with a total score of 0–2, 3, 4 and 5 points were considered as “unsatisfactory,” “satisfactory,” “good,” or “very good” respectively. Cohort and case–control studies with a total score of 0–3, 4, 5–6 and 7–8 points were considered as “unsatisfactory,” “satisfactory,” “good,” or “very good” respectively” (Supplementary File 2).

Study Selection Process

Initially, 10,243 papers were found through the four database searches. After paper duplicates were excluded (n = 6,524), the title and abstracts of 3,719 papers were screened. Of these, 456 were found related to the aim of study and after a full text review, 417 studies were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion were as follows: 37 studies did not meet the quality appraisal score (8%), and 380 studies utilized a non-quantitative methodology or did not report parametric measurements such as coefficients, or odd ratios of relative risks of determinants of study outcomes (92%). Following exclusions, 39 studies remained for meta-analysis (Afifi et al., 2010; Ahuja et al., 2021; Andronicos et al., 2016; Battersby et al., 2006; Bischof et al., 2015, 2016; Black et al., 2015; Carr et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2015; Guillou-Landreat et al., 2016; Håkansson & Karlsson, 2020; Hodgins et al., 2006; Husky et al., 2015; Jolly et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2016; Ledgerwood et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2021; Lloyd et al., 2016; Maccallum & Blaszczynski, 2003; Mallorquí-Bagué et al., 2018; Manning et al., 2015; Moghaddam et al., 2015; Newman & Thompson, 2007; Nower et al., 2004; Park et al., 2010; Petry & Kiluk, 2002; Ronzitti et al., 2017; Sharman et al., 2022; Slutske et al., 2022; Sundqvist & Wennberg, 2022; Valenciano-Mendoza et al., 2021a, 2021b; Valenciano-Mendoza et al., 2021a, 2021b; Verdura-Vizcaíno et al., 2015; Wardle & McManus, 2021; Wardle et al., 2020; Weinstock et al., 2014; Winters & Kushner, 2003; Wong et al., 2010, 2014) (Supplementary File 3).

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

The meta-analysis was performed by producing pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on factors related to suicidal behaviors (ideations and attempts) among IWGDs. The summary effect sizes were computed by an inverse variance weighting. These values were gained from regression coefficients for the multivariate analyses. Moreover, actual effect sizes among studies with random effects models were different. Therefore, a random-effects model was applied to model selection and calculating publication bias. Two uncertainty sources were recognized such as within-study sampling error and between-study variance. The analysis used large Cochran's Q statistics with small p-values and large I2 statistics to consider the heterogeneity in true effect sizes of the studies.

To identify the sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were performed according to sample size and geographic regions. Data from at least two studies were needed to explain the variable under consideration within each stratum. Sensitivity analysis was carried out using Baujat plots comprising a random effect model. Influential effects were identified by excluding each study from the analysis to assess their effect on the overall estimates. Funnel plots, trim-and-fill analysis, and Rosenthal's fail-safe number were used to identify publication bias in the studies. R 3.5.1 software ‘Meta’ package was used for the data analysis.

Publication Bias

To identify potential publication bias, the Egger's test and graph were performed. Considering the symmetry assumption, there was no significant publication bias in the reviewed studies selected for inclusion. As regards the funnel plot, the distribution of the papers was not oriented for most of them. In fact, it was identical, confirming no publication biases observed in the study. The publication bias test indicated considerable bias based on Egger’s test (coefficient = 3.66, p-value < 0.001).

Results

Study Characteristics

Selected studies were from three World Health Organization regions (16 from the America region [n = 88,798 participants], 15 from the European region [n = 41,169 participants], and eight from the Western Pacific region [n = 21,040 participants]). The USA and Canada had the highest number of included studies, with eight studies each (n = 26,332 in the US and 65,466 participants in Canada). Considering country income level, 38 studies were conducted in high-income countries (n = 147,321), and one study was conducted in an upper-middle-income country (n = 3,686). Study size at baseline had a mean of 3,871, with 79 being the lowest sample size (Battersby et al., 2006), and 36,894 being the largest sample size (Newman & Thampson, 2007). Response rates between studies varied from 57% to 100%. Participants had a mean age of 32.84 years and were more likely to be male in the studies (mean 63.87%), varying from 32% to 100%. Most (n = 26) were cross-sectional studies (66%). More than three-quarters were published between 2010 and 2021 (76%). Twenty-seven studies (69%) assessed both suicide ideations and suicide attempts as the outcomes, taken from either administrative databases or self-report surveys. Five studies assessed suicide ideations only, and six studies assessed suicide attempts only as the outcome measure. Twenty-eight studies (71%) used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as diagnostic criteria for assessing GD. Almost all studies (90%) used a simple question for assessing suicidal behaviors among IWGDs (e.g., “Have you ever thought about suicide?” and/or “Have you ever attempted suicide?”). Eleven studies (28%) used the South Oaks Gambling Screen to assess GD. Among the 39 studies included in the meta-analysis, two reported sociodemographic variables among IWDGs, five reported risky behaviors, 19 reported mental health disorders, and 10 reported alcohol use disorders (Table 1).

Prevalence of Suicidal Behaviors Among Gambling Disorders

The present study showed a significant life-time pooled prevalence rate of 31% for suicide ideations (95% CI, 23–39%), 17% for suicide plans (95% CI, 0–34%), and 16% for suicide attempts (95% CI, 12–20%) among IWGDs (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Sociodemographic Characteristics, Risky Behaviors, Mental Health Disorders, and Alcohol Use Disorders Associated with Suicidal Behaviors Among Individuals with Gambling Disorders

IWGDs who had chronic physical illnesses were 1.82 times more likely than those who did not to report lifetime suicide ideations (OR = 1.82, 95%CI = 1.37–2.42). Additionally, IWGDs who had any debt were 1.82 times more likely than those who did not to report lifetime suicide ideations (OR = 1.82, 95%CI = 1.48–2.23). Those who were older than 35 years were 2.91 times more likely than who were not to report lifetime suicide attempts (OR = 2.91, 95%CI = 1.96–4.34). Significant associations were found between history of sexual abuse and suicide attempts among IWGDs. Moreover, IWGDs who had history of sexual abuse were 2.48 times more likely than those who did not to report lifetime suicide attempts (OR = 2.48, 95%CI = 1.81–3.39). There was no significant association found between any financial debt and suicide attempts among IWGDs (OR = 4.41, 95%CI = 0.60–32.47). IWGSs with depression (compared to those without) were (i) 3.58 times more likely to have suicide ideations (OR = 3.58, 95%CI = 1.09–11.74) and (ii) 5.61 times more likely to have lifetime suicide attempts (OR = 5.61, 95%CI = 2.90–10.83). Also, IWGDs with mood disorders (compared to those without) were (i) 5.11 times more likely to have suicide ideations (OR = 5.11, 95%CI = 3.06–8.54) and (ii) 5.20 times more likely to have lifetime suicide attempts (OR = 5.20, 95%CI = 2.92–9.28). Finally, IWGDs with alcohol use disorders (compared to those without) were (i) 1.38 times more likely to have suicide ideations (OR = 1.38, 95%CI = 1.04–1.83) and (ii) 2.08 times more likely to have lifetime suicide attempts (OR = 2.08, 95%CI = 1.51–2.86) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis and Baujat plots were performed to identify influential effects. Effects on the right-hand side show studies with more heterogeneity. The studies that had the most contributions to the heterogeneity were removed following the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Files 4–19).

Subgroup Analysis

In the present study, several subgroup analyses were conducted to identify the main source of heterogeneity on pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. The factors taken into consideration were age, study design, sample size, year of publication of studies, geographical location and gambling disorder assessment tools. However, no heterogeneity was detected. Non-evaluated variables such as participants’ gender and other variables may have been sources of heterogeneity (Supplementary File 20).

Discussion

The present meta-analysis explored variables associated with suicidal behaviors among IWGDs. Generally, suicide ideations among IWGDs were associated with having any financial debt and having chronic physical illnesses, as well as experiencing depression, mood disorders, and alcohol use disorders. Suicide attempts among IWGDs were associated with being older and having a childhood history of sexual abuse, as well as experiencing depression, mood disorders and/or alcohol use disorders.

The pooled prevalence rates of suicide ideations, suicide plans, and lifetime suicide attempts in the present study were 31%, 17% and 16%, respectively. No pooled prevalence for these three suicidal behaviors has previously been reported in relation to IWGDs. Among IWGDs, the most recently published cross-sectional study reported lower rate of suicide ideation (20.6%) than the present study (31%), and a lower rate of suicide attempts (6.7%) than the present study (16%) (Valenciano-Mendoza et al., 2021a, 2021b). The difference between suicide behaviors among IWGDs in this recent study and results of the present study might be because IWGDs in the study by (Valenciano-Mendoza et al., 2021a, 2021b) did not report any risky behaviors (such as child sexual abuse) or and alcohol use disorders.

A previous study among IWGDs found a significant association between chronic medical conditions, older age, and suicidal behavior. Furthermore, elevated prevalence rates of arteriosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases were significantly related among IWGDs (Pilver & Potenza, 2013). IWGDs are more likely to have conditions related to stress, such as hypertension, lack of sleep, cardiovascular disease, and peptic ulcer disease (Fong, 2005; Meyer et al., 2000). These data highlight the necessity of further investigations on the relationship between chronic physical illnesses and IWGDs, to potentially include heart condition screening when examining IWGDs.

The findings suggest that IWGDs who were in debt were 1.82 times more likely to display suicidal ideation than gamblers who were not in debt. Previous studies have suggested that having financial debts is significantly associated with suicidal ideation (Guillou-Landreat et al., 2016; Komoto, 2014; Ledgerwood et al., 2005) and support the findings of the present study. In comparison with the general population, studies have shown that those in debt are 2.50 (Rojas, 2022) to 3.39 (Naranjo et al., 2021) times more likely to have suicidal behaviors than those who are not. There are a number of possible explanations for the difference between the general population and IWGDs. First, it may simply be due to the small number of studies that reported financial debts in the present study. Second, the general population may not have any experience of prior financial debts. Therefore, the general population with financial debts may have a higher likelihood of suicidal behaviors than IWGDs (who may have more resilience in dealing with debt as it is likely to be a common occurrence of their problematic gambling). Third, not being able to pay debts and feeling guilty and/or highly anxious about this may be a very stressful and painful experience which may cause a desire to escape, and finally, suicide attempts (Rojas, 2022), and may be more so among individuals in the general population compared to IWGDs. Finally, it could be that more IWGDs actually die by suicide than the general population leaving a lower proportion of IWGDs that experience lesser suicide behaviors such as suicidal ideation.

Such incursion of debt suggests that gambling goes from being an enjoyable social activity to a state where the dire consequences of gambling contribute to a sense of hopelessness through the chasing of losses (Battersby et al., 2006). Suicidality is known to be associated with mental health conditions. However, the burden of medical conditions can lead to the aggravation of suicidality among IWGDs. Gambling counseling professionals and other service providers should not overlook the significance of gambling disorder’s financial burden and acute physical problems in relation to suicidality.

IWGDs who had history of sexual abuse were 2.48 times more likely than those who did not to report lifetime suicide attempts. This is similar to the general population who have history of sexual abuse who (in a meta-analysis study) were estimated to be 2.43 times more likely to have suicide behaviors compared to those who did not have a history of sexual abuse (Devries et al., 2014). Although the association between history of sexual abuse and gambling needs further investigation, previous studies have reported that sexual trauma may lead to emotional vulnerability, that increases gambling behaviors (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; Dion et al., 2015). According to Polusny and Follette’s (1995) emotional avoidance theory, childhood sexual abuse as a stressor may cause avoidant coping behaviors, such as substance abuse (Polusny and Follette, 1995). Although these behaviors may temporarily decrease childhood sexual abuse-related memories and sedation, they may lead to long-term negative consequences such as problematic gambling behaviors as a maladaptive coping strategy to avoid stress caused by childhood sexual abuse trauma (Dion et al., 2015). Overall, this indicates that childhood sexual abuse is a stressor that may increase the development of maladaptive coping behaviors, including gambling disorder.

Previous studies have also highlighted a significant association between elevated risk of suicide attempts and histories of childhood sexual abuse (Fernández-Montalvo et al., 2019; Jakubczyk et al., 2014). The findings of other studies have indicated that histories of childhood trauma and stress can negatively affect brain development, which in turn exposes the individual to experiencing psychopathological symptoms (Leeb et al., 2011; Twardosz & Lutzker, 2010). According to genetic, epidemiological, and clinical studies, childhood traumatic experiences exacerbate suicidality. The present study also suggests a need to create prevention and intervention programs for victims of sexual abuse such as media campaigns and school-based prevention programs to meet their needs.

The present study’s finding showed that IWGDs who had depression were 3.58 and 5.61 times more likely to display suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than IWGDs who had not. Also, those who had mood disorders were 5.11 and 5.20 times more likely to display suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than IWGDs who had not. Compared to the general population who had depression and mood disorders, they are 2.47 (Ribeiro et al., 2018) and 1.42 (Baldessarini et al., 2019) times more likely to have suicide behaviors than those who did not respectively. Co-occurring depressive and mood disorders among IWGDs are associated with negative effects, such as intense gambling (Lister et al., 2015), greater likelihood of problem gambling relapse following treatment (Hodgins et al., 2005, 2010), increased probability of dedicating higher proportions of their income on gambling activities (El-Guebaly et al., 2006), and increased risk of suicidal ideation and attempts (Petry & Kiluk, 2002). However, IWGDs with co-occurring mood disorders are no more likely to initiate gambling treatment than IWGDs without mood disorders (Ledgerwood et al., 2013).

Mood disorders, including depression are among determinants of suicidality. Moreover, more than 90% of completed suicide cases have been classified with at least one kind of psychiatric condition, such as schizophrenia (Hor & Taylor, 2010), anxiety disorders (Sareen et al., 2005), depression or bipolar disorders (Isometsä, 2014), and mood disorders (Bertolote et al., 2004). Previous studies conducted among individuals with mental health disorders have highlighted a robust relationship between impulsiveness and aggressiveness traits (Koller et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2022), recent alcohol or substance use, as well as enhanced risk of suicide (Armoon et al., 2021, 2022). Studies have suggested a higher rate of depression among individuals with problem gambling and suicidality (Ledgerwood & Petry, 2004; Thon et al., 2014). Several health-related behaviors are associated with depression, such as obesity, alcohol consumption, higher cigarette smoking rates, immune system alterations, cardiovascular and endocrine conditions, as well as biological dysregulations (Lorains et al., 2011; Newman & Thompson, 2003). Previous studies have suggested that gambling disorders appear to be associated with the severity of active psychiatric problems (Winters & Kushner, 2003). If an IWGD’s psychiatric symptoms are not severe, their gambling disorders should be treated first while monitoring the psychiatric symptoms (Winters & Kushner, 2003). Another study recommended strategies to treat comorbid psychiatric disorder and gambling disorders, and that modifying psychoeducational and behavioral problems of gambling behavior may be helpful to gamblers who use gambling to deal with their problems (Nunes et al., 1996). One study showed that assertive community treatment and intensive case management approaches decreased suicidal behaviors among these vulnerable groups (Wang et al., 2015).

The present study’s findings showed that IWGDs who had alcohol use disorders were 1.38 and 2.08 times more likely to display suicidal ideation and attempts than gamblers who had not. This compares to a previous meta-analysis which reported that among the general population who had alcohol use disorders, they were 1.10 and 1.67 times more likely to have suicidal ideation and attempts than those who did not (Amiri & Behnezhad, 2020). This suggests that IWGDs who have alcohol use disorders are more likely to experience suicidal behaviors than general population. One factor to take into consideration is the availability of alcohol in gambling venues which potentially encourages gamblers who have alcohol use disorders to play longer than planned and may be less able to make informed decisions about their gambling behavior (Leino et al., 2017).

The results of the present study can be used to frame the consequences of gambling and alcohol use disorders in the general population. Predominantly, the available training regarding gambling and alcohol use disorders are concentrated on the impacts of alcohol use on problem gambling (e.g., continued play despite losing and betting more than can afford to lose; (Baron & Dickerson, 1999). However, relatively few initiatives specifically warn gamblers of the personal risks of alcohol use. The findings suggest that public health officials should educate gamblers (and IWGDs more specifically) about the increases risk of suicidal behaviors when alcohol use is combined with their gambling behavior. Such training can specifically be beneficial to IWGDs who are at greater risk of suicidality than those who do not experience financial losses (Kim et al., 2016). In a similar vein, gambling venues should also be encouraged to better manage the provision of alcohol and gambling in the same place. The availability of alcohol in gambling settings potentially encourages gamblers to play longer than planned. This issue has been supported by previous research, indicating a substantial association between alcohol consumption and elevated problematic gambling, such as higher amounts of monetary loss (Ellery et al., 2005; Håkansson & Karlsson, 2020; Kim et al., 2016).

Methodological Considerations Related to Results

The studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis have some methodological concerns. First, two-thirds of the included studies were cross-sectional designs, preventing the delineation of a causal/temporal association between the research variables under study. Second, different instruments for assessing gambling disorders were used such as International Classification of Diseases (ninth and tenth revision), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (third, fourth and fifth versions), South Oaks Gambling Screen, and Canadian Problem Gambling Index (among others). Consequently, comparisons of gambling disorder using different screening instruments can be challenging. Third, other variables included in the studies were not retained in the meta-analysis because there were not present in more than two studies (e.g., marital status, nicotine dependence, insomnia, taking medication, mental health care, having mental health counseling, intense treatment utilization). Fourth, the selected number of studies was arguably limited to the variables examined. Research which reported sociodemographic variables associated with suicidal behaviors comprised only two studies for older age. Due to low number of studies considering sociodemographic variables, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results.

Regarding risky behaviors associated with suicidal behaviors, there were two studies examining any financial debt, two studies examining childhood sexual abuse, and three studies examining chronic physical illnesses. High heterogeneity was observed among risky behaviors. Therefore, the associations may be weak. In addition, due to the relatively low number of studies, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results. Regarding mental health disorders associated with suicidal behaviors, there were eleven studies examining depression disorders and five studies examining mood disorders. High heterogeneity was observed among mental health disorders. Therefore, the associations may be weak. In addition, due to low number of studies examining mood disorders, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results. There were ten studies examining alcohol use disorders associated with suicidal behaviors. High heterogeneity was observed among the studies. Therefore, the associations may be weak.

Finally, there was high heterogeneity between studies. The present study assessed several variables such as country of study, publication year, sample size, study design, age of participants and gambling disorder assessments. However, no sources of heterogeneity were found. Therefore, variables that were not evaluated (such as participants’ gender) may be sources of heterogeneity. Although several subgroup analyses were performed to reduce the effect of heterogeneity, not all sources of heterogeneity could be considered since the more subgroup analyses that are conducted, the more the number of studies in each subgroup decreases. Since the source of heterogeneity could not be found, and subgroup analysis on variables such as gender could not be performed, further cohort and case control studies are needed.

Conclusion

Financial credit and payday loans may lead IWGDs to continue their gambling habits, even in situations where they may have lost large amounts of money which may cause debt problems and psychological distress. The findings suggest that gambling regulators and/or banks should introduce protective measures to limit consumers’ debt to reduce financial and psychological costs of gambling problems. Moreover, based on the findings in the present study, histories of sexual abuse should perhaps be included in the medical records of IWGDs and that tailored treatment plans must include individuals’ histories of physical and sexual abuse. There is a robust association between psychiatric conditions and suicidality. According to the literature, healthcare professionals are suggested to evaluate depressive symptoms precisely and seriously to screen individuals at risk for suicidal behaviors. The present study data extended this necessity to also including the monitoring of concurrent mood disorders and suicidal behaviors among IWGDs. Such measures can help to facilitate seeking support among this group by de-stigmatizing mental health disorders as well as improving the quality of care presented to individuals with psychiatric conditions.

Joint efforts from mental health services and problem gambling services are necessary to ensure that individuals with dual diagnosis of GD and psychiatric disorders are treated effectively. It is recommended that gambling counseling centers should collaborate with other mental health agencies to implement a wide range of new and enhanced services including individual and group counseling, workshops, community programs, screening protocols, and referral systems. Based on the results of the present study, it is recommended that gambling treatment providers take into account detailed patient assessment and possible treatment for IWDGs at the same time for comorbid conditions, such as alcohol use, mood, and depressive disorders to improve the pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic interventions for gambling problems. Such action would likely reduce suicidal risk among IWDGs. To protect those with alcohol use disorders (as well as those without), measures are necessary to restrict the provision of alcohol in gambling venues.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Afifi, T. O., Cox, B. J., Martens, P. J., Sareen, J., & Enns, M. W. (2010). The relationship between problem gambling and mental and physical health correlates among a nationally representative sample of Canadian women. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101(2), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03404366

Ahuja, M., Werner, K. B., Cunningham-Williams, R. M., & Bucholz, K. K. (2021). Racial associations between gambling and suicidal behaviors among black and white adolescents and young adults. Current Addiction Reports, 8(2), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00374-8

Amiri, S., & Behnezhad, S. (2020). Alcohol use and risk of suicide: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(2), 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1736757

Andronicos, M., Beauchamp, G., Robert, M., Besson, J., & Séguin, M. (2016). Male gamblers – suicide victims and living controls: Comparison of adversity over the life course. International Gambling Studies, 16(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1151914

Armoon, B., Fleury, M.-J., Bayani, A., Mohammadi, R., Ahounbar, E., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). Suicidal behaviors among intravenous drug users: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Use, 1–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2022.2120435

Armoon, B., SoleimanvandiAzar, N., Fleury, M.-J., Noroozi, A., Bayat, A.-H., Mohammadi, R., Ahounbar, E., & Fattah Moghaddam, L. (2021). Prevalence, sociodemographic variables, mental health condition, and type of drug use associated with suicide behaviors among people with substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 39(4), 550–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2021.1912572

Baldessarini, R. J., Tondo, L., Pinna, M., Nuñez, N., & Vázquez, G. H. (2019). Suicidal risk factors in major affective disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(4), 621–626. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.167

Baron, E., & Dickerson, M. (1999). Alcohol consumption and self-control of gambling behaviour. Journal of Gambling Studies, 15(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023057027992

Battersby, M., Tolchard, B., Scurrah, M., & Thomas, L. (2006). Suicide ideation and behaviour in people with pathological gambling attending a treatment service. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 4, 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-006-9022-z

Bayani, A., Ghiasvand, H., Rezaei, O., Fattah Moghaddam, L., Noroozi, A., Ahounbar, E., Higgs, P., & Armoon, B. (2020). Factors associated with HIV testing among people who inject drugs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(3), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1771235

Bayat, A.-H., Mohammadi, R., Moradi-Joo, M., Bayani, A., Ahounbar, E., Higgs, P., Hemmat, M., Haghgoo, A., & Armoon, B. (2020). HIV and drug related stigma and risk-taking behaviors among people who inject drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1718264

Benson, O., Gibson, S., Boden, Z. V. R., & Owen, G. (2016). Exhausted without trust and inherent worth: A model of the suicide process based on experiential accounts. Social Science & Medicine, 163, 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.045

Bertolote, J. M., Fleischmann, A., De Leo, D., & Wasserman, D. (2004). Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: Revisiting the evidence. Crisis, 25(4), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.147

Bischof, A., Meyer, C., Bischof, G., John, U., Wurst, F. M., Thon, N., Lucht, M., Grabe, H. J., & Rumpf, H. J. (2015). Suicidal events among pathological gamblers: The role of comorbidity of axis I and axis II disorders. Psychiatry Research, 225(3), 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.074

Bischof, A., Meyer, C., Bischof, G., John, U., Wurst, F. M., Thon, N., Lucht, M., Grabe, H. J., & Rumpf, H. J. (2016). Type of gambling as an independent risk factor for suicidal events in pathological gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000152

Black, D. W., Coryell, W., Crowe, R., McCormick, B., Shaw, M., & Allen, J. (2015). Suicide ideations, suicide attempts, and completed suicide in persons with pathological gambling and their first-degree relatives. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(6), 700–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12162

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x

Carr, M. M., Ellis, J. D., & Ledgerwood, D. M. (2018). Suicidality among gambling helpline callers: A consideration of the role of financial stress and conflict. American Journal on Addictions, 27(6), 531–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12787

Cook, S., Turner, N. E., Ballon, B., Paglia-Boak, A., Murray, R., Adlaf, E. M., Ilie, G., den Dunnen, W., & Mann, R. E. (2015). Problem gambling among Ontario students: Associations with substance abuse, mental health problems, suicide attempts, and delinquent behaviours. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9483-0

De Beurs, D., Fried, E. I., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., O’ Connor, D. B., Ferguson, E., O’ Carroll, R. E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2019). Exploring the psychology of suicidal ideation: A theory driven network analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 120, 103419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103419

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y. T., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Bacchus, L. J., Astbury, J., & Watts, C. H. (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and suicidal behavior: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 133(5), e1331–e1344. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2166

Díaz-Oliván, I., Porras-Segovia, A., Barrigón, M. L., Jiménez-Muñoz, L., & Baca-García, E. (2021). Theoretical models of suicidal behaviour: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. European Journal of Psychiatry, 35(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2021.02.002

Dion, J., Cantinotti, M., Ross, A., & Collin-Vézina, D. (2015). Sexual abuse, residential schooling and probable pathological gambling among indigenous peoples. Child Abuse & Neglect, 44, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.004

Dowling, N. A., Cowlishaw, S., Jackson, A. C., Merkouris, S. S., Francis, K. L., & Christensen, D. R. (2015). The prevalence of comorbid personality disorders in treatment-seeking problem gamblers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29(6), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2014_28_168

El-GuebalyPatten, N. S. B., Currie, S., Williams, J. V. A., Beck, C. A., Maxwell, C. J., & Wang, J. L. (2006). Epidemiological associations between gambling behavior, substance use & mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22(3), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-006-9016-6

Ellery, M., Stewart, S. H., & Loba, P. (2005). Alcohol’s effects on video lottery terminal (VLT) play among probable pathological and non-pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(3), 299–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-005-3101-0

Fernández-Montalvo, J., López-Goñi, J. J., Arteaga, A., & Haro, B. (2019). Suicidal ideation and attempts among patients with lifetime physical and/or sexual abuse in treatment for substance use disorders. Addiction Research & Theory, 27(3), 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1485891

Fong, T. W. (2005). The biopsychosocial consequences of pathological gambling. Psychiatry, 2(3), 22–30.

Ghiasvand, H., Higgs, P., & Noroozi, M. (2020). Social and demographical determinants of quality of life in people who live with HIV/AIDS infection: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Biodemography and Social Biology, 65(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2019.1587287

Ghiasvand, H., Waye, K. M., Noroozi, M., Harouni, G. G., & Armoon, B. (2019). Clinical determinants associated with quality of life for people who live with HIV/AIDS: A meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 768. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4659-z

Guillou-Landreat, M., Guilleux, A., Sauvaget, A., Brisson, L., Leboucher, J., Remaud, M., Challet-Bouju, G., & Grall-Bronnec, M. (2016). Factors associated with suicidal risk among a French cohort of problem gamblers seeking treatment. Psychiatry Research, 240, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.008

Håkansson, A., & Karlsson, A. (2020). Suicide attempt in patients with gambling disorder-associations with comorbidity including substance use disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 593533. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.593533

Hodgins, D. C., & El-Guebaly, N. (2010). The influence of substance dependence and mood disorders on outcome from pathological gambling: Five-year follow-up. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9137-9

Hodgins, D. C., Mansley, C., & Thygesen, K. (2006). Risk factors for suicide ideation and attempts among pathological gamblers. American Journal on Addictions, 15(4), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550490600754366

Hodgins, D. C., Peden, N., & Cassidy, E. (2005). The association between comorbidity and outcome in pathological gambling: A prospective follow-up of recent quitters. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(3), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-005-3099-3

Hor, K., & Taylor, M. (2010). Suicide and schizophrenia: A systematic review of rates and risk factors. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 24(4_suppl), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359786810385490

Husky, M. M., Michel, G., Richard, J. B., Guignard, R., & Beck, F. (2015). Gender differences in the associations of gambling activities and suicidal behaviors with problem gambling in a nationally representative French sample. Addictive Behaviors, 45, 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.011

Isometsä, E. (2014). Suicidal behaviour in mood disorders–who, when, and why? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(3), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900303

Jakubczyk, A., Klimkiewicz, A., Krasowska, A., Kopera, M., Sławińska-Ceran, A., Brower, K. J., & Wojnar, M. (2014). History of sexual abuse and suicide attempts in alcohol-dependent patients. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(9), 1560–1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.010

John Mann, J., & Rizk, M. M. (2020). A brain-centric model of suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(10), 902–916. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081224

Johnson, J., Gooding, P., & Tarrier, N. (2008). Suicide risk in schizophrenia: Explanatory models and clinical implications, The Schematic Appraisal Model of Suicide (SAMS). Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 81(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608307X244996

Jolly, T., Trivedi, C., Adnan, M., Mansuri, Z., & Agarwal, V. (2021). Gambling in patients with major depressive disorder is associated with an elevated risk of suicide: Insights from 12-years of Nationwide inpatient sample data. Addictive Behaviors, 118, 106872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106872

Kim, H. S., Salmon, M., Wohl, M. J. A., & Young, M. (2016). A dangerous cocktail: Alcohol consumption increases suicidal ideations among problem gamblers in the general population. Addictive Behaviors, 55, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.12.017

Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Saffer, B. Y. (2016). Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204

Koller, G., Preuß, U. W., Bottlender, M., Wenzel, K., & Soyka, M. (2002). Impulsivity and aggression as predictors of suicide attempts in alcoholics. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252(4), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-002-0362-9

Komoto, Y. (2014). Factors associated with suicide and bankruptcy in Japanese pathological gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12(5), 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-014-9492-3

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Ledgerwood, D. M., Arfken, C. L., Wiedemann, A., Bates, K. E., Holmes, D., & Jones, L. (2013). Who goes to treatment? Predictors of treatment initiation among gambling help-line callers. The American Journal on Addictions, 22(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00323.x

Ledgerwood, D. M., & Petry, N. M. (2004). Gambling and suicidality in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(10), 711–714. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000142021.71880.ce

Ledgerwood, D. M., Steinberg, M. A., Wu, R., & Potenza, M. N. (2005). Self-reported gambling-related suicidality among gambling helpline callers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164x.19.2.175

Lee, K., Kim, H., & Kim, Y. (2021). Gambling disorder symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Psychiatry Investigation, 18(1), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.0035

Leeb, R. T., Lewis, T., & Zolotor, A. J. (2011). A review of physical and mental health consequences of child abuse and neglect and implications for practice. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(5), 454–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2020.101930

Leino, T., Molde, H., Griffiths, M. D., Mentzoni, R. A., Sagoe, D., & Pallesen, S. (2017). Gambling behavior in alcohol-serving and non-alcohol-serving-venues: A study of electronic gaming machine players using account records. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(3), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1288806

Leung, C. L. K., Kwok, S. Y. C. L., & Ling, C. C. Y. (2016). An integrated model of suicidal ideation in transcultural populations of Chinese adolescents. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(5), 574–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9920-2

Lister, J. J., Milosevic, A., & Ledgerwood, D. M. (2015). Psychological characteristics of problem gamblers with and without mood disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(8), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000806

Lloyd, J., Hawton, K., Dutton, W. H., Geddes, J. R., Goodwin, G. M., & Rogers, R. D. (2016). Thoughts and acts of self-harm, and suicidal ideation, in online gamblers. International Gambling Studies, 16(3), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1214166

Lorains, F. K., Cowlishaw, S., & Thomas, S. A. (2011). Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: Systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addiction, 106(3), 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03300.x

Maccallum, F., & Blaszczynski, A. (2003). Pathological gambling and suicidality: An analysis of severity and lethality. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.1.88.22781

Mallorquí-Bagué, N., Mena-Moreno, T., Granero, R., Vintró-Alcaraz, C., Sánchez-González, J., Fernández-Aranda, F., Pino-Gutiérrez, A. D., Mestre-Bach, G., Aymamí, N., Gómez-Peña, M., Menchón, J. M., & Jiménez-Murcia, S. (2018). Suicidal ideation and history of suicide attempts in treatment-seeking patients with gambling disorder: The role of emotion dysregulation and high trait impulsivity. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1112–1121. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.132

Manning, V., Koh, P. K., Yang, Y., Ng, A., Guo, S., Kandasami, G., & Wong, K. E. (2015). Suicidal ideation and lifetime attempts in substance and gambling disorders. Psychiatry Research, 225(3), 706–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.011

Meyer, G., Hauffa, B. P., Schedlowski, M., Pawlak, C., Stadler, M. A., & Exton, M. S. (2000). Casino gambling increases heart rate and salivary cortisol in regular gamblers. Biological Psychiatry, 48(9), 948–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00888-x

Moghaddam, J. F., Yoon, G., Dickerson, D. L., Kim, S. W., & Westermeyer, J. (2015). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in five groups with different severities of gambling: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. American Journal on Addictions, 24(4), 292–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12197

Moore, F. R., Doughty, H., Neumann, T., McClelland, H., Allott, C., & O’Connor, R. C. (2022). Impulsivity, aggression, and suicidality relationship in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101307

Naranjo, D. E., Glass, J. E., & Williams, E. C. (2021). Persons with debt burden are more likely to report suicide attempt than those without: A national study of US adults. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(3), 19m13184. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19m13184

Newman, S. C., & Thompson, A. H. (2003). A population-based study of the association between pathological gambling and attempted suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(1), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.1.80.22785

Newman, S. C., & Thompson, A. H. (2007). The association between pathological gambling and attempted suicide: Findings from a national survey in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(9), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200909

Nower, L., Gupta, R., Blaszczynski, A., & Derevensky, J. (2004). Suicidality and depression among youth gamblers: A preliminary examination of three studies. International Gambling Studies, 4(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1445979042000224412

Nunes, E. V., Deliyannides, D., Donovan, S., & McGrath, P. J. (1996). The management of treatment resistance in depressed patients with substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(2), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70290-2

O’Connor, R. C., & Portzky, G. (2018). The relationship between entrapment and suicidal behavior through the lens of the integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.021

O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

O’Connor, R. C., & Nock, M. K. (2014). The psychology of suicidal behaviour. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6

Park, S., Cho, M. J., Jeon, H. J., Lee, H. W., Bae, J. N., Park, J. I., Sohn, J. H., Lee, Y. R., Lee, J. Y., & Hong, J. P. (2010). Prevalence, clinical correlations, comorbidities, and suicidal tendencies in pathological Korean gamblers: Results from the Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(6), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0102-9

Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2011). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

Petry, N. M., & Kiluk, B. D. (2002). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(7), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200207000-00007

Pilver, C. E., & Potenza, M. N. (2013). Increased incidence of cardiovascular conditions among older adults with pathological gambling features in a prospective study. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 7(6), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829e9b36

Polusny, M. A., & Follette, V. M. (1995). Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: Theory and review of the empirical literature. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 4, 143–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80055-1

Rezaei, O., Ghiasvand, H., Higgs, P., Noroozi, A., Noroozi, M., Rezaei, F., Armoon, B., & Bayani, A. (2020). Factors associated with injecting-related risk behaviors among people who inject drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(4), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1781346

Ribeiro, J. D., Huang, X., Fox, K. R., & Franklin, J. C. (2018). Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(5), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.27

Rojas, Y. (2022). Financial indebtedness and suicide: A 1-year follow-up study of a population registered at the Swedish Enforcement Authority. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(7), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211036166

Ronzitti, S., Soldini, E., Smith, N., Potenza, M. N., Clerici, M., & Bowden-Jones, H. (2017). Current suicidal ideation in treatment-seeking individuals in the United Kingdom with gambling problems. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.032

Rudd, M. D. (2000). The suicidal mode: A cognitive-behavioral model of suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 30(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb01062.x

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Afifi, T. O., de Graaf, R., Asmundson, G. J., ten Have, M., & Stein, M. B. (2005). Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(11), 1249–1257. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249

Sharman, S., Murphy, R., Turner, J., & Roberts, A. (2022). Predictors of suicide attempts in male UK gamblers seeking residential treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 126, 107171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107171

Slutske, W. S., Davis, C. N., Lynskey, M. T., Heath, A. C., & Martin, N. G. (2022). An epidemiologic, longitudinal, and discordant-twin study of the association between gambling disorder and suicidal behaviors. Clinical Psychological Science, 10(5), 901–919. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026211062599

Soloff, P. H., Feske, U., & Fabio, A. (2008). Mediators of the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.3.221

Sundqvist, K., & Wennberg, P. (2022). The association between problem gambling and suicidal ideations and attempts: A case control study in the general Swedish population. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(2), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09996-5

Taylor, P. J., Gooding, P., Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2011). The role of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety, and suicide. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 391–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022935

Thon, N., Preuss, U. W., Pölzleitner, A., Quantschnig, B., Scholz, H., Kühberger, A., Bischof, A., Rumpf, H. J., & Wurst, F. M. (2014). Prevalence of suicide attempts in pathological gamblers in a nationwide Austrian treatment sample. General Hospital Psychiatry, 36(3), 342–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.01.012

Twardosz, S., & Lutzker, J. R. (2010). Child maltreatment and the developing brain: A review of neuroscience perspectives. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.003

Valenciano-Mendoza, E., Fernández-Aranda, F., Granero, R., Gómez-Peña, M., Moragas, L., Mora-Maltas, B., Håkansson, A., Menchón, J. M., & Jiménez-Murcia, S. (2021a). Prevalence of suicidal behavior and associated clinical correlates in patients with behavioral addictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111085

Valenciano-Mendoza, E., Fernández-Aranda, F., Granero, R., Gómez-Peña, M., Moragas, L., Pino-Gutierrez, A. D., Mora-Maltas, B., Baenas, I., Guillén-Guzmán, E., Valero-Solís, S., Lara-Huallipe, M. L., Codina, E., Mestre-Bach, G., Etxandi, M., Menchón, J. M., & Jiménez-Murcia, S. (2021b). Suicidal behavior in patients with gambling disorder and their response to psychological treatment: The roles of gender and gambling preference. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 143, 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.027

Verdura-Vizcaíno, E. J., Fernández-Navarro, P., Vian-Lains, A., Ibañez, Á., & Baca-García, E. (2015). Características sociodemográficas y comorbilidad de sujetos con juego patológico e intento de suicidio en España. Revista Colombiana De Psiquiatría, 44(3), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2015.03.002

Wang, Y., Bhaskaran, J., Sareen, J., Wang, J., Spiwak, R., & Bolton, J. M. (2015). Predictors of future suicide attempts among individuals referred to psychiatric services in the emergency department: A longitudinal study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(7), 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000000320

Wardle, H., John, A., Dymond, S., & McManus, S. (2020). Problem gambling and suicidality in England: Secondary analysis of a representative cross-sectional survey. Public Health, 184, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.024

Wardle, H., & McManus, S. (2021). Suicidality and gambling among young adults in Great Britain: Results from a cross-sectional online survey. Lancet Public Health, 6(1), e39–e49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30232-2

Weinstock, J., Scott, T. L., Burton, S., Rash, C. J., Moran, S., Biller, W., & Kruedelbach, N. (2014). Current suicidal ideation in gamblers calling a helpline. Addiction Research & Theory, 22(5), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2013.868445

Winters, K. C., & Kushner, M. G. (2003). Treatment issues pertaining to pathological gamblers with a comorbid disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19(3), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024203403982

Wong, P. W., Cheung, D. Y., Conner, K. R., Conwell, Y., & Yip, P. S. (2010). Gambling and completed suicide in Hong Kong: A review of coroner court files. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(6), PCC.09m00932. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.09m00932blu

Wong, P. W., Kwok, N. C., Tang, J. Y., Blaszczynski, A., & Tse, S. (2014). Suicidal ideation and familicidal-suicidal ideation among individuals presenting to problem gambling services: A retrospective data analysis. Crisis, 35(4), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000256

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BA conceived the study. BA collected all data. BA and RM analyzed and interpreted the data. BA and EA drafted the manuscript. MDG and BA contributed to the revised paper and were responsible for all final editing. All authors commented on the drafts of the manuscript and approved the final copy of the paper for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest except MDG. MDG has received research funding from Norsk Tipping (the gambling operator owned by the Norwegian government). MDG has received funding for a number of research projects in the area of gambling education for young people, social responsibility in gambling and gambling treatment from GambleAware (formerly the Responsibility in Gambling Trust), a charitable body which funds its research program based on donations from the gambling industry. MDG undertakes consultancy for various gambling companies in the area of social responsibility in gambling.

Ethical Approval

This study was an analysis of pre-existing literature and did not use human participants.

Informed Consent

Not applicable. Secondary data analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10899_2023_10188_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 4. Baujat plot for pooled prevalence ratio of suicidal ideation among individuals with gambling disorders. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneit

10899_2023_10188_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 5. Pooled prevalence ratio of suicidal ideation after removing Mallorquí−Bagué et al., 2018 (study that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM6_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 6. Baujat plot for pooled prevalence ratio of suicide attempts among individuals with gambling disorders. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM7_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 7. Pooled prevalence ratio of suicide attempts after removing Newman & Thampson, 2007 (study that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM8_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 8. Baujat plot for having chronic physical illnesses associated with suicidal ideation. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM9_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 9. Pooled odds ratio of having chronic physical illnesses associated with suicidal ideation after removing Manning et al., 2015 (study that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM10_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 10. Baujat plot for having depression associated with suicidal ideation. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM11_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 11. Pooled odds ratio of having depression associated with suicidal ideation after removing Nower et al., 2004 (study that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM12_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 12. Baujat plot for having chronic depression associated with suicide attempts. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM13_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 13. Pooled odds ratio of having depression associated with suicide attempts after removing Wardle., 2020 and Newman & Thampson, 2003 (studies that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM14_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 14. Baujat plot for having mood disorders associated with suicide attempts. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM15_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 15. Pooled odds ratio of having mood disorders associated with suicide attempts after removing Bischof et al., 2015 and Bischof et al., 2016 (studies that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM16_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 16. Baujat plot for having alcohol use disorders associated with suicidal ideation. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM17_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 17. Pooled odds ratio of having alcohol use disorders associated with suicidal ideation after removing Slutske et al., 2022 (study that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM18_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 18. Baujat plot for having alcohol use disorders associated with suicide attempts. Effects on the right part indicated studies contribute much to the heterogeneity

10899_2023_10188_MOESM19_ESM.pdf

Supplementary File 19. Pooled odds ratio of having alcohol use disorders associated with suicide attempts after removing Newman & Thampson, 2003 (study that had the most contribution of heterogeneity)

10899_2023_10188_MOESM20_ESM.docx

Supplementary File 20. Subgroup analysis based on random-effect models for pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among individuals with gambling disorders

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Armoon, B., Griffiths, M.D., Mohammadi, R. et al. Suicidal Behaviors and Associated Factors Among Individuals with Gambling Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J Gambl Stud 39, 751–777 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10188-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10188-0