Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate intimate partner violence (IPV) involving children and the parenting role (e.g., preventing an intimate partner from providing parental care or threatening to take one’s children away). Specifically, the study examined whether this form of IPV affects maternal functioning above and beyond other IPV experiences. Participants included a community sample of 120 primarily low-income, single women, diverse in age, education, and ethnicity, who were interviewed 1 year after giving birth, as part of a longitudinal study. IPV involving children and the parenting role was significantly associated with other experiences of IPV, especially general psychological IPV. Multiple regression analyses revealed that this form of IPV significantly affected mothers’ personal, relational, and parental functioning. Results suggest that it is important to assess for IPV involving children and the parenting role when working with mothers. More research on this unique type of IPV is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research concerning intimate partner violence (IPV) over the last several decades has led to advances in methodology, an expansion of conceptualizations and typologies of violence, and increased knowledge and understanding of prevalence rates, predictors, and outcomes (Black et al. 2011; Dutton and Goodman 2005; Mechanic et al. 2008). However, there is still room for further development in all of these areas. In particular, a closer examination of more specific types and conceptualizations of IPV may be beneficial. One type of IPV particularly relevant to women who have children involves use of the victimized partner’s children and role as a parent. For instance, clinical papers, qualitative studies, and reviews (e.g., Bancroft et al. 2012; Buchanan et al. 2014; Dutton and Goodman 2005; Edin et al. 2010; Stark 2007) have noted that a number of abusive intimate partners criticize and overrule their partner’s parenting, express jealousy of their partner’s attention toward the children, threaten to take the children away, and mistreat or endanger the children to control their partner. However, this type of IPV has received very little focused empirical attention.

Research, that has just begun to focus on this type of IPV as an important construct in its own right, has found prevalence rates that are quite high in both clinical and community samples of women (Ahlfs-Dunn and Huth-Bocks 2012; Beeble et al. 2007; Hayes 2012). This research also indicates a variety of negative outcomes for women who experience such IPV. However, whether IPV involving children and the parenting role accounts for negative outcomes above and beyond the effects of IPV as it is more generally and typically conceptualized and assessed (i.e., general psychological, physical, and/or sexual violence) is unknown. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to advance the literature on this topic through investigating this research question using a diverse, primarily single, low-income, community sample of mothers.

Researchers typically conceptualize IPV in a general manner, i.e., as psychological or emotional violence (e.g., insults, humiliation, threats of violence), physical violence (e.g., hitting, kicking, choking), and/or sexual violence (e.g., use of force, threats, or coercion to engage in intercourse or other sexual behaviors). However, IPV may be even more nuanced than these broad groups imply. This is particularly true for psychological violence, which can include a variety of specific tactics to victimize and establish power and control over intimate partners; this may also be referred to as coercive control or intimate terrorism (Dutton and Goodman 2005; Johnson 2006; Stark 2007). Assessing IPV in a general manner fails to fully capture these specific tactics, and thereby limits understanding of IPV and its consequences. IPV that involves use of the victimized partner’s children and role as a parent is one such specific type of IPV that may best fall under the more general conceptualizations of psychological violence, coercive control, or intimate terrorism, but is not fully captured by current IPV assessments. Although this type of IPV may overlap with other conceptualizations of IPV, it will primarily be referred to as a form of psychological violence in this paper.

For mothers, specifically, IPV involving use of her children and her parenting role can take a variety of forms and manifest differently based on a multitude of factors. Broadly, though, it takes advantage of and uses her identity and role as a caregiver, relationship with her children, and drive to protect and nurture her children as a way to victimize her. Examples of this type of IPV include, but are not limited to, making threats to kidnap, harm, or kill the children; making threats to report the mother to Child Protective Services (CPS) and have the children removed from her care; making threats to leave the children without a mother by deporting or killing her; criticizing, degrading, and humiliating the mother either directly to her when her children are present or as comments to her children when she is not present; requiring the children to keep track of their mother’s activities, relay threatening messages, or harass her; physically abusing, kidnapping, or otherwise putting the children in danger as a means to intimidate, threaten, or punish the mother; limiting or withholding resources so the mother can not meet her children’s needs; expressing jealousy of the mother’s attention toward her children; preventing the mother from comforting and caring for her children; forcing the children to participate in abuse of their mother; and abusing the mother in front of her children or while she is pregnant, thereby undermining her value as a person, her role as a mother, and her ability to protect her children (Bancroft et al. 2012; Beeble et al. 2007; Buchanan et al. 2014; Buckley et al. 2007; Dutton and Goodman 2005; Dutton et al. 2005; Edin et al. 2010; Hayes 2012; Kelly 2009; Lapierre 2010; McGee 1997; Moe 2009; Moore et al. 2010; Mullender et al. 2002; Radford and Hester 2006; Stark 2007; Thiara 2010; Tubbs and Williams 2007). As illustrated in the above examples, use of children in this type of IPV is not limited by age or developmental level of the child as there are both direct (e.g., requiring the children to keep track of their mother’s activities, relay threatening messages, or harass her) and indirect (e.g., making threats to kidnap, harm, or kill the children) ways in which children can be used to victimize their mothers.

Although some of the tactics that are referenced in the literature may overlap with child maltreatment, and research has consistently found that child maltreatment occurs in homes with IPV around 50 % of the time (Zolotor et al. 2007), it should be noted that the focus of these tactics is on controlling, intimidating, and arousing fear in the partner. For this reason, the term IPV, rather than the overlapping but more encompassing term ‘domestic violence’, is being used in this paper. Conceptualizing these tactics as a form of IPV emphasizes that this type of violence is primarily directed at the romantic partner, rather than the children, as a strategy to further control, undermine, and degrade her. Some factors that may influence how this type of IPV is expressed include the age and gender of the children, whether the abusive partner is the biological father, step-father, or father-figure of the children, and what the current living and/or custody arrangements are (Beeble et al. 2007).

IPV involving use of a mother’s children and her parenting role has been discussed in some clinical writings (Bancroft et al. 2012), has been noted when qualitative methods have been used to study IPV (Buchanan et al. 2014; Edin et al. 2010; Lapierre 2010; Radford and Hester 2006), and has been embedded within broader IPV assessments via inclusion of a few items (Tolman 1989; Walters et al. 2013). However, empirical research investigating the prevalence rates, predictors, and outcomes of this form of violence is much more limited. Of the quantitative research that has focused specifically on better understanding this type of IPV, researchers have reported prevalence rates of 28 % (the present study sample during pregnancy; Ahlfs-Dunn and Huth-Bocks 2012), 53 % (the present study sample during the first year after birth; Ahlfs-Dunn and Huth-Bocks 2012), and 88 % (a sample of women who were seeking services for IPV and who had at least one child between 5 and 12 years of age; Beeble et al. 2007). Another recent study (Hayes 2012) reported prevalence rates of specific tactics that involved the mother’s children (age of children was not reported) for a sample of women who had obtained an order for protection from their children’s fathers as a result of IPV; only families where the children still had visitation with their fathers were included. At baseline, Hayes reported prevalence rates for specific tactics involving use of the mother’s children that ranged from 14.7 % (threatened to kill the children) to 81.1 % (threatened to take the children away from the mother). At the follow-up interview (6 months later, on average), prevalence rates for specific tactics involving use of the mother’s children ranged from 0.0 % (threatened to kill the children) to 26.6 % (told lies to the children about the mother).

Prevalence rates from the above existing studies highlight the relatively common occurrence of IPV involving use of a mother’s children and her parenting role during pregnancy, immediately after a child is born, and when mothers have very young children and older school-aged children. These few studies also suggest that this type of psychological violence occurs both prior to and after a mother’s separation from her abusive partner, and this type of violence may not decrease at the same rate as physical IPV after separation (Hayes 2012). One existing study also indicated that levels of physical and sexual violence tended to be higher when this type of IPV was present (Beeble et al. 2007). Last, previous research conducted using the present study’s sample indicated that mothers who had experienced this type of IPV either during pregnancy or the first year after birth, in comparison to mothers who had not experienced this type of IPV, were more likely to experience poorer mental health, poorer self-esteem in regard to being a mother, and greater parenting stress (Ahlfs-Dunn and Huth-Bocks 2012). Thus, preliminary evidence suggests that IPV involving use of a mother’s children and her role as a parent may be particularly harmful to not only her personal functioning, but also to her parental functioning

There are several reasons to pursue further understanding of IPV involving children and the parenting role. First, research on IPV indicates that not only is violence against women highly prevalent (Alhabib et al. 2010; Black et al. 2011), but the greatest risk for IPV appears to be during the childbearing years (Rivara et al. 2009; Walton-Moss et al. 2005). In fact, even during pregnancy, where prevalence rates fall between 0.9 % and 36 % (Devries et al. 2010; Taillieu and Brownridge 2009), IPV is just as severe and/or frequent (if not more so) for many (13 %-71 %) women as at other times (Taillieu and Brownridge 2009). High rates of IPV (20.9 %-30 %) also continue to be found in the early postpartum period (Charles and Perreira 2007; Rosen et al. 2007). Thus, mothers, especially those with young children, make up a large number of women who experience IPV each year; better understanding their specific experiences of IPV is important for their own well-being and for their children’s well-being.

Furthermore, psychological violence is not only the most commonly reported type of IPV (Ludermir et al. 2010; Martin et al. 2006), but it also appears to be just as, if not more, detrimental than physical and sexual IPV (Huth-Bocks et al. 2013; Mechanic et al. 2008; O’Leary 1999). For women, being a mother is often a large part of one’s self-identity (Stern 1995), and it influences self-esteem (Shea and Tronick 1988). Additionally, the mother-child relationship has been observed to be a source of strength for mothers experiencing IPV (Irwin et al. 2002). Therefore, violence that threatens this role and relationship may be particularly damaging.

Finally, psychological, physical, and sexual forms of IPV have been repeatedly shown to negatively affect a variety of outcomes for women. For example, several decades of research have demonstrated that IPV before or after giving birth to a child contributes to a number of different mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Bargai et al. 2007; Karmaliani et al. 2009; Ludermir et al. 2010; Rodriguez et al. 2010; Stampfel et al. 2010). Qualities of romantic relationships, such as satisfaction, commitment, levels of love, and attachment are also impacted by current and past experiences of IPV (Giordano et al. 2010; Hellemans et al. 2015; Shortt et al. 2010; Williams and Frieze 2005; Young and Furman 2013). IPV also has negative effects on parenting, such that mothers who experience IPV tend to exhibit poorer parenting (Kelleher et al. 2008; Krishnakumar and Buehler 2000; Levendosky et al. 2006), higher potential for child abuse (Casanueva and Martin 2007; Cohen et al. 2008), and significantly greater parenting stress (Holden et al. 1998; Ritchie and Holden 1998). Thus, better understanding what contributes to the myriad of negative outcomes for women experiencing IPV is important.

The Present Study

Little research has examined IPV that aims to victimize mothers through using their children and their role as a parent in a comprehensive way. Although it is clear that this type of partner violence can be considered a detrimental type of psychological violence, it is unknown whether it accounts for negative maternal outcomes above and beyond what can already be accounted for by typical assessments of IPV (i.e., general psychological, physical, and/or sexual IPV directed at the woman that does not involve her children or her parenting role). Further empirical investigation is warranted to determine whether or not research and clinical efforts should be directed toward this specific form of psychological IPV. The present study, therefore, aimed to address this gap in the literature by examining associations between IPV involving children and the parenting role, more general forms of IPV typically examined in the literature (general psychological, physical, and/or sexual violence), and maternal outcomes, including mental health symptoms, perceived romantic relationship quality, parenting stress, and parenting daily hassles. A wide range of outcomes was purposefully examined due to the established literature demonstrating pervasive effects of IPV on women’s functioning. Hypotheses for the present study were: (1) IPV involving children and the parenting role would be significantly associated with other, broader forms of IPV (general psychological, physical, and sexual violence), (2) IPV involving children and the parenting role would be most strongly associated with general psychological partner violence as compared to physical and sexual partner violence, and (3) IPV involving children and the parenting role would significantly affect maternal mental health, perceived romantic relationship quality, and parenting outcomes, above and beyond the more general forms of IPV typically assessed in the literature.

Method

Participants

Participants included 120 primarily low-income women who participated in a longitudinal study on parenting over the course of pregnancy to the infant’s third birthday (PI = Alissa Huth-Bocks, PhD, Parenting Project, Eastern Michigan University). Only data from the third wave of the longitudinal study were used in the present study. This wave of data (n = 114; 95 % retention) was collected 1 year after participants had given birth to the study child. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 42 (M = 26.2, SD = 5.7) at study entry, 30 % were pregnant for the first time, and 47 % self-identified as African American, 36 % as Caucasian, 12 % as Biracial, and 5 % as belonging to other ethnic groups. At study entry, 63 % of participants reported that they were single (never married), 28 % married, 4 % separated, and 5 % divorced. Furthermore, 20 % of participants reported having a high school diploma/GED or less education, 44 % reported having some college or trade school, and 36 % reported having a college degree. The median monthly family income for participants was $1500.00 (range = $0-$10,416.00) at the start of the study, and participants reported receiving a variety of public social services: Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program (73 %), food stamps (52 %), Medicaid, Mi-Child, or Medicare (76 %), and public supplemental income (17 %).

Procedures

This study maintained University IRB approval throughout its duration. Interviews were conducted in either the participant’s home (92 %), at a research office (4 %), or over the phone (4 %), and they lasted approximately 3 h. After informed consent procedures, a number of questionnaires were administered as part of a larger assessment battery. The lead research assistant read all questionnaires aloud to the participant and wrote down the participant’s verbal answers in order to minimize random responding and protect against literacy difficulties; however, participants were also given a questionnaire packet with which to follow along for convenience. At the end of the interview, participants were given a referral list of community resources and were compensated with $50 in cash and a baby gift.

Measures

General Types of Intimate Partner Violence

The 33 victimization items from the Conflict Tactics Scales-2 (CTS-2; Straus et al. 2003) were used to assess for general experiences of partner violence over the last year. There are four subscales: psychological (8 items), physical (12 items), and sexual violence (7 items), as well as injury resulting from partner violence (6 items). Items are responded to using the following categories: 0 (never), 1 (once), 2 (twice), 3 (3–5 times), 4 (6–10 times), 5 (11–20 times), 6 (more than 20 times), and 7 (not during these time periods, but it happened before). The CTS-2 is scored by using a weighting system in which values are recoded (1 = 1, 2 = 2, 3 = 4, 4 = 8, 5 = 15, and 6 = 25) and then summed into their respective subscales and all together for a total. Higher scores indicate greater severity (frequency) of IPV. Good internal consistency reliability for each of the CTS-2 subscales has been reported, factor analyses have indicated that each item typically loads highest on its intended subscale, and there is evidence of convergent and discriminant validity (Straus et al. 2003). In the present study, the total score and the psychological, physical, and sexual violence subscales were used.

IPV Involving Children and the Parenting Role

After a review of the literature, an 11-item questionnaire to assess mothers’ experiences of IPV that involved their children and/or their role as a parent was created for the longitudinal study. Due to the composition of the longitudinal study sample, the items were designed to be applicable to women who had recently been pregnant and who had very young children. Items aimed to assess multiple aspects of this form of IPV, such as controlling, intimidating, or eliciting fear in the mother via use of the child (e.g., threats regarding the child), preventing the mother from providing protection and care, interfering with other aspects of parenting, degrading parenting efficacy, and undermining the mother-child relationship. The format of this questionnaire was modeled after the CTS-2 (Straus et al. 2003) in order to increase ease of use and comparison. Participants indicated the frequency with which they experienced each item during the last year using the same response categories as the CTS-2. Values were also recoded using the same weighting system as the CTS-2 and then summed to create a total score. Higher scores indicate greater severity (frequency) of this specific type of psychological partner violence. Previous research using data from the same longitudinal study indicated adequate internal consistency reliability, moderate 1-year test-retest reliability, and concurrent and predictive validity (Ahlfs-Dunn and Huth-Bocks 2012). There is also evidence of convergent and concurrent validity in the present study, detailed in the Results below. Please see Table 1 for the 11 questionnaire items and frequencies at which they were endorsed in the sample.

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that was used to assess for depression symptoms. Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. Participants respond based on how they have been feeling for the past 2 weeks, and items are summed to create a total score. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. Internal consistency reliability for the BDI-II has been found to be excellent when used with a variety of samples, there is high 1-week test-retest reliability, and there is also evidence of construct validity (Arnau et al. 2001; Beck et al. 1996).

Anxiety and Hostility

The 6 anxiety items and the 5 hostility items from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis 1993) were used to assess for anxiety and hostility symptoms. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Participants indicate how much they have been bothered or distressed by each symptom during the past week. Respective items are summed to create total scores for anxiety and hostility. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. Both subscales have been found to have good internal consistency reliability, as well as high 2-week test-retest reliability. There is also evidence of convergent validity for both subscales (Derogatis and Lazarus 1994; Prinz et al. 2013).

Traumatic Stress Symptoms

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers et al. 1993) is a 17-item self-report questionnaire that was used to assess for PTSD symptoms. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Participants report how much they have been experiencing each symptom over the last month. A total score is calculated by summing items. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. High internal consistency reliabilities have been reported for the PCL-C, as well as high 1-week and moderate 2-week test-retest reliability and evidence for convergent validity (Blanchard et al., 1996; Ruggiero et al. 2003).

Perceived Romantic Relationship Quality

Braiker and Kelley’s (1979) 25-item self-report questionnaire on intimate relations was used to assess perceived romantic relationship quality. Items are rated on a 9-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much). Participants reported on their current relationship or, if they were not currently in a relationship, their most significant romantic relationship in the last year. Items are summed into their respective subscales (i.e., love [10 items], maintenance [5 items], ambivalence [5 items], and conflict [5 items]) or all together for a total score. Higher scores indicate more of the construct. Within various samples, internal consistency reliability tends to be adequate and stable for all subscales except maintenance (Belsky et al. 2005; Bosch and Curran 2011); therefore, it was not used in the present study. There is evidence of validity for the measure (Holland and McElwain 2013).

Parenting Stress

The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin 1995) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that was used to assess parenting stress. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, with the majority rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Items are summed to create a total score. Higher scores indicate greater parenting stress. High internal consistency reliability, high 1-year test-retest reliability, and evidence for convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity have been reported (Haskett et al. 2006; Reitman et al. 2002).

Parenting Daily Hassles

The Parenting Daily Hassles Scale (PDH; Crnic and Greenberg 1990) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that was used to assess for the frequency and perceived intensity of relatively minor, but inconvenient and potentially bothersome parenting tasks and challenging child behaviors. Participants consider the past 6 months and indicate the frequency with which they have experienced each item on a 4-point scale (rarely, sometimes, often, constantly) and the intensity with which they perceive the item to be a hassle on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Items are summed for separate frequency and intensity total scores, and higher scores indicate more of the construct. High internal consistency reliability has been reported, the two scales are highly correlated, and there is evidence of convergent validity (Crnic and Greenberg 1990).

Results

Missing Data and Scale Transformation

Missing item-level and scale-level data on all variables were minimal (no more than 10 %) and primarily a result of attrition. All missing data were imputed using an expectation maximization algorithm from SPSS 17.0 (single imputation) prior to data analysis except for 6 participants on the perceived romantic relationship quality measure (because they had not been in a romantic relationship in the last year) and 4 participants on the PSI-SF and the PDH (because the baby’s birth was not confirmed or there was a lengthy maternal separation from the infant that prevented daily care for the infant). Thus, analyses were based on 114–120 participants depending on which variables were included in the analysis. Problematic skew and kurtosis were addressed with log-transformations prior to data analysis.

Descriptive Statistics

As noted earlier, frequencies for different forms of IPV involving children and the parenting role can be found in Table 1. There was a wide range by which the items were endorsed (0.0 % to 28.1 %). The four most commonly endorsed items were, “My partner has been jealous of the time and attention I give my new baby,” “My partner intentionally overruled or failed to back up my parenting decision,” “My partner says that I am a bad mother or criticizes my parenting skills,” and “My partner threatened to take my child(ren) away from me.” Descriptive data for all study variables can be found in Table 2. As can be seen, a wide range of general experiences of IPV (total, psychological, physical, sexual) were reported, with general psychological IPV being the most frequently reported on average. Similarly, a wide range of mental health symptoms were reported, but symptom levels were low on average for this sample. In regard to perceived romantic relationship quality, on average, feelings of love were relatively high, feelings of ambivalence were relative low, and perceived conflict was at a moderate level, yet a wide range of all qualities were endorsed. Last, parenting stress and frequency and intensity of parenting daily hassles were, on average, endorsed at a relatively low level.

Associations Between Types of IPV

As first hypothesized, there was a significant, positive association between IPV involving children and the parenting role and general experiences of IPV, r = 0.61, p < 0.01. Additionally, IPV involving children and the parenting role was significantly associated with each of the three broad types of IPV typically examined in the literature including general psychological violence, r = 0.60, p < 0.01, physical violence, r = 0.42, p < 0.01, and sexual violence, r = 0.26, p < 0.01. The strongest association was with general psychological violence, as hypothesized second.

Associations Between Types of IPV and Maternal Outcomes

The third hypothesis was tested using several hierarchical multiple regressions for each outcome variable. Overall, the third hypothesis was supported.

Mental Health

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses indicated that general experiences of IPV significantly predicted mothers’ depression symptoms (β = 0.34, p < 0.001) and accounted for 11 % of the variance. IPV involving children and the parenting role also predicted mothers’ depression symptoms at a trend level and accounted for an additional 3 % of the variance when it was added to the model. Mothers’ anxiety and PTSD symptoms were each significantly predicted by general experiences of IPV until IPV involving children and the parenting role was taken into account, then only IPV involving children and the parenting role predicted mothers’ anxiety (β = 0.24, p < 0.05) and PTSD symptoms (β = 0.30, p < 0.01). Adding IPV involving children and the parenting role to the model significantly led to predicting an additional 4 % and 6 % of the variance in mothers’ anxiety and PTSD symptoms, respectively. Last, mothers’ hostility symptoms were predicted by general experiences of IPV (β = 0.27, p < 0.05) and IPV involving children and the parenting role (β = 0.24, p < 0.05). IPV involving children and the parenting role significantly accounted for an additional 4 % of the variance when it was added to the model. See Table 3 for results of all mental health outcomes.

Perceived Romantic Relationship Quality

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses indicated that general experiences of IPV significantly, negatively predicted mothers’ feelings of love in their romantic relationships until IPV involving children and the parenting role was added to the model, then only IPV involving children and the parenting role significantly, negatively predicted mothers’ feelings of love toward their partners (β = −0.30, p < 0.01). IPV involving children and the parenting role also accounted for an additional 6 % of the variance when added to the model. Mothers’ feelings of ambivalence in their romantic relationships were significantly, positively predicted by both general experiences of IPV (β = 0.45, p < 0.001) and IPV involving children and the parenting role (β = 0.23, p < 0.05). IPV involving children and the parenting role accounted for an additional 3 % of the variance in predicting ambivalence when added to the model. Last, only general experiences of IPV significantly, positively predicted perceived conflict in mothers’ romantic relationships (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and accounted for 20 % of the variance. IPV involving children and the parenting role did not account for any additional variance when added to the model. See Table 4 for results.

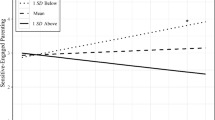

Parenting Stress and Daily Hassles

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses revealed that mothers’ parenting stress was significantly predicted by general experiences of IPV (β = 0.19, p < 0.05) initially; however, when IPV involving children and the parenting role was added to the model, neither type of IPV was a significant predictor of parenting stress. General experiences of IPV accounted for 4 % of the variance in predicting parenting stress; no additional variance was significantly accounted for by IPV involving children and the parenting role. Frequency of parenting daily hassles was not significantly predicted by general experiences of IPV; however, IPV involving children and the parenting role did significantly predict this outcome when added to the model (β = 0.34, p < 0.01); the latter type of IPV also accounted for an additional 7 % of the variance. Somewhat similarly, intensity of parenting daily hassles was not significantly predicted by general experiences of IPV; however, IPV involving children and the parenting role did predict this outcome when added to the model, but only at trend-level. IPV involving children and the parenting role accounted for an additional 3 % of the variance in predicting intensity of parenting daily hassles. See Table 5 for results.

Discussion

As research on IPV has typically focused on IPV more broadly (i.e., general psychological, physical, and/or sexual IPV), it is important to determine if investigating more specific types or conceptualizations of IPV would be beneficial to the field. The present study focused on a specific type of psychological IPV that involves use of the victimized partner’s children and role as a parent. The purpose of the study was to examine how IPV involving children and the parenting role affects maternal outcomes above and beyond general types of IPV. Results revealed support for all three hypotheses.

First, as hypothesized, IPV involving children and the parenting role was found to be strongly associated with general experiences of IPV. This suggests that IPV involving children and the parenting role overlaps with, but is still unique from, IPV assessed more broadly. Moreover, of the three general types of IPV (i.e., psychological, physical, and sexual), IPV involving children and the parenting role was most strongly associated with general psychological violence, as anticipated in the second hypothesis. This finding suggests that IPV involving children and the parenting role best fits within the category of psychological IPV and other similar constructs such as coercive control and intimate terrorism. The third hypothesis was also supported, although the findings were more complex than originally anticipated. Of the outcome variables that were examined (mental health, perceived romantic relationship quality, and parenting stress and daily hassles), IPV involving children and the parenting role significantly predicted several maternal outcomes and accounted for a significant additional amount of variance for several variables above and beyond general experiences of IPV.

Results relevant to the third hypothesis can be broken down by outcome variable examined. First, when added to the model after general IPV, IPV involving children and the parenting role was a significant predictor of mothers’ anxiety, hostility, and PTSD symptoms. Findings with depression symptoms were similar, but at trend-level significance. Notably, general experiences of IPV were no longer a significant predictor of anxiety and PTSD symptoms when IPV involving children and the parenting role was added to the model. Thus, when it comes to mothers’ mental health symptoms, this specific type of psychological IPV should not be overlooked, particularly for mothers who have recently given birth and who may be especially focused on caregiving. In this light, it makes sense that violence that instills fear surrounding the well-being of one’s children, that undermines one’s identity and esteem as a parent, and that undermines one’s relationship with one’s children would contribute to a variety of mental health symptoms during this critical period.

Second, when added to the model after general IPV, IPV involving children and the parenting role was a significant predictor of mothers’ feelings of love and ambivalence in their romantic relationships; general experiences of IPV remained a significant predictor of mothers’ feelings of ambivalence, but not their feelings of love toward their partner. In contrast, perceived conflict with the current partner was only predicted by general experiences of IPV. Thus, it appears that for mothers who have given birth within the last year, positive feelings of love and closeness with their current partner are most influenced by an absence of IPV experiences involving children and the parenting role, whereas perceptions of conflict are most influenced by general experiences of IPV. Both types of IPV influence uncertain or ambivalent feelings about the current partner. Together, the findings highlight, as would be expected, that IPV influences perceptions of romantic relationship quality; however, the association varies by type of IPV and type of romantic relationship component.

Third, when added to the model after general IPV, IPV involving children and the parenting role was a significant predictor of the frequency of daily parenting hassles reported by mothers. A similar result was found for mothers’ reported intensity of daily parenting hassles, but this was at trend-level significance. In contrast, broad feelings of parenting stress related to personal well-being and caregiving were predicted by general experiences of IPV. These findings suggest that different types of IPV may account for different parenting outcomes. It is notable that it was frequency of parenting daily hassles that was most associated with IPV involving children and the parenting role. This suggests that for mothers who have given birth recently, and therefore have at least one young child, this specific type of psychological violence is less related to how subjectively burdened or hassled they feel as a parent and more related to the actual number of parenting demands they face regularly. This may be because IPV involving children and the parenting role leads to a greater number of parenting challenges that must be handled daily. For example, children may be more directly affected by this type of IPV and may respond with more challenging behaviors. This finding may also reflect the particular statements and behaviors that make up this type of psychological IPV (i.e., abusive partners may repeatedly highlight these hassles as part of the abuse). Alternatively, it is possible that a higher level of these daily parenting hassles prompt abusive tactics involving use of the children and the parenting role.

Strengths

There are several strengths of the present study. First, this is one of very few studies to focus specifically on investigating IPV that involves use of a mother’s children and parenting role in a comprehensive manner, rather than using one or a few items embedded within a broader assessment of IPV. The present study not only increases awareness and understanding of this type of psychological IPV, but it also demonstrates how it influences outcomes above and beyond the general experiences of IPV that are typically examined in the literature. Moreover, this study examined a number of outcomes that are relevant to mothers’ personal, relational, and parental functioning within a community sample of diverse, primarily single, low-income mothers with young children. Looking broadly at mothers’ well-being within the context of different types of IPV highlights not only the detrimental impact that IPV can have on a mother, but also that areas of functioning can be impacted differently. Findings additionally suggest that IPV involving children and the parenting role can be just as, if not more, important in understanding outcomes for mothers. Last, it is a strength of this study that a community sample was used, as this may allow the findings to be more widely generalized to IPV victims.

Limitations

There are also limitations to the present study. First, the study was cross-sectional in design, thereby preventing a look at outcomes over time. Although use of a community sample may increase generalizability, the specific demographics of the sample (e.g., primarily single, low-income mothers who recently gave birth) may be limiting. In particular, findings may be primarily relevant to mothers who are around 1 year post-birth and caring for very young children, as these circumstances can be influential in the outcomes assessed. Moreover, the measure of IPV involving children and the parenting role was created to be particularly applicable to women who had recently been pregnant and who had very young children, and this may also limit generalizability. Items that would be more applicable to older children (e.g., using the child to keep track of the mother’s activities) were not included. Additionally, only 11 items were used; therefore, some experiences of this type of IPV were likely missed. Last, all data were collected via self-report, which may result in common problems that are particularly relevant to IPV research, such as possible underreporting.

Research Implications

As this is a relatively new line of research, future research should attempt to replicate these findings with other samples, as well as investigate other outcomes and consider assessing for a wider range of items beyond those included in this and other recent studies (e.g., Beeble et al. 2007; Hayes 2012). There is still a considerable amount to learn about IPV involving children and the parenting role and the ways in which abusive partners seek control via instilling fear about the well-being of the mother’s children, degrading the mother’s identity and esteem as a parent, interfering with parenting, and undermining the mother-child relationship. For instance, how are children affected by this type of IPV? Are the child outcomes any different or are they more severe than the child outcomes associated with exposure to general types of IPV? Overall, results of this research suggest that further investigation into more specific types or more specific conceptualizations of IPV, such as IPV involving children and the parenting role, would be beneficial to the IPV field. Such research would allow current IPV measures to be refined and may encourage development of measures more applicable to certain populations. Ultimately, focusing greater research efforts on more specific types and conceptualizations of IPV would further increase understanding of the nuances of IPV.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Results from this study indicate that IPV involving children and the parenting role is damaging to mothers’ personal, relational, and parental functioning beyond what is typically captured by assessments of general experiences of IPV. When working with mothers, it would be beneficial to assess for this specific type of psychological IPV, as well as impairments in personal, relational, and parental functioning and disruptions in the mother-child relationship. Results from such assessments could then inform treatment and safety planning, as well as provide a better context for understanding presenting difficulties. Clinical IPV interventions may be particularly beneficial if mother and child treatments are integrated. Dyadic interventions, such as Child-Parent Psychotherapy (Lieberman and Van Horn 2005, 2008), can be particularly beneficial when the mother-child relationship is in need of repair, which is a likely consequence of IPV involving young children and the parenting role. Home visiting programs designed to decrease child maltreatment, such as Nurse Family Partnership (Olds et al. 2003) and Healthy Families America (Daro and Harding 1999), may also benefit from identifying different forms of IPV within the home as additional stressors that further put the mother-child dyad at risk.

Moreover, for those who work with IPV through other systems, like family court, this research can offer greater insight into and validation of mothers’ experiences of this specific type of psychological IPV (see Hayes 2012 for specific discussion of these tactics during the process of separation). It may also offer a context for understanding issues such as difficult child behaviors, strained mother-child relationships, and mothers’ concerns regarding their children’s well-being, all of which may be highlighted during parenting evaluations, custody determinations, and other procedures. Recent research has indicated that mothers often directly disclose IPV involving children and the parenting role to mediators when working out custody arrangements, but their concerns and allegations are often dismissed (Rivera et al. 2012). This is especially problematic when the safety and well-being of children is at stake. Therefore, greater knowledge regarding IPV involving children and the parenting role may be particularly influential and pertinent to policies and practices surrounding custody arrangements.

Conclusion

In summary, IPV involving children and the parenting role is a specific type of psychological IPV that has been discussed in clinical writings and qualitative research, but has rarely been empirically examined in a comprehensive manner that is distinguishable from more general IPV assessments. Results from the present study indicate that IPV involving children and the parenting role affects mothers’ personal, relational, and parental functioning above and beyond the effects of IPV as it is typically assessed (i.e. general psychological, physical, and/or sexual violence). These findings have important implications for research, clinical work, and policy related to IPV.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress index: Professional manual (3rd ed., ). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Ahlfs-Dunn, S. M., & Huth-Bocks, A. C. (2012). Psychological violence against women by intimate partners: The use of children to victimize mothers. In H. R. Cunningham, & W. F. Berry (Eds.), Handbook on the psychology of violence (pp. 123–144). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Alhabib, S., Nur, U., & Jones, R. (2010). Domestic violence against women: Systematic review of prevalence studies. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 369–382. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9298-4.

Arnau, R. C., Meagher, M. W., Norris, M. P., & Bramson, R. (2001). Psychometric evaluation of the beck depression inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychology, 20, 112–119. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.20.2.112.

Bancroft, L., Silverman, J. G., & Ritchie, D. (2012). Shock waves: The batterer’s impact on the home. In Author, The batterer as parent: Addressing the impact of domestic violence on family dynamics (2nd ed. pp. 69–105). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bargai, N., Ben-Shakhar, G., & Shalev, A. Y. (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battered women: The mediating role of learned helplessness. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 267–275. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9078-y.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beeble, M. L., Bybee, D., & Sullivan, C. M. (2007). Abusive men’s use of children to control their partners and ex-partners. European Psychologist, 12, 54–61. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.12.1.54.

Belsky, J., Jaffee, S. R., Sligo, J., Woodward, L., & Silva, P. A. (2005). Intergenerational transmission of warm-sensitive-stimulating parenting: A prospective study of mothers and fathers of 3 year-olds. Child Development, 76, 384–396. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00852.x.

Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Blanchard, E.B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T.C., & Forneris, C.A. (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 669–673. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2.

Bosch, L. A., & Curran, M. A. (2011). Identity style and relationship quality for pregnant cohabitating couples during the transition to parenthood. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 11, 47–63. doi:10.1080/15283488.2010.540738.

Braiker, H. B., & Kelley, H. H. (1979). Conflict in the development of close relationships. In R. Burgess, & T. Huston (Eds.), Social exchange and developing relationships (pp. 135–168). New York: Academic Press.

Buchanan, F., Power, C., & Verity, F. (2014). The effects of domestic violence on the formation of relationships between women and their babies: “I was too busy protecting my baby to attach.”. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 713–724. doi:10.1007/s10896-014-9630-5.

Buckley, H., Holt, S., & Whelan, S. (2007). Listen to me! Children’s experiences of domestic violence. Child Abuse Review, 16, 296–310. doi:10.1002/car.995.

Casanueva, C. E., & Martin, S. L. (2007). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and mothers’ child abuse potential. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 603–622. doi:10.1177/0886260506298836.

Charles, P., & Perreira, K. M. (2007). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and 1-year post-partum. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 609–619. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9112-0.

Cohen, L. R., Hien, D. A., & Batchelder, S. (2008). The impact of cumulative maternal trauma and diagnosis on parenting behavior. Child Maltreatment, 13, 27–38. doi:10.1177/1077559507310045.

Crnic, K. A., & Greenberg, M. A. (1990). Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development, 61, 1628–1637.

Daro, D. A., & Harding, K. A. (1999). Healthy families America: Using research to enhance practice. The Future of Children, 9, 152–176.

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI, brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedure manual (4th ed., ). Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

Derogatis, L. R., & Lazarus, L. (1994). SCL-90-R, brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment (pp. 217–248). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Devries, K. M., Kishor, S., Johnson, H., Stöckl, H., Bacchus, L. J., Garcia-Moreno, C., & Watts, C. (2010). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reproductive Health Matters, 18, 158–170. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36533-5.

Dutton, M. A., & Goodman, L. A. (2005). Coercion in intimate partner violence: Toward a new conceptualization. Sex Roles, 52, 743–756. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-4196-6.

Dutton, M. A., Goodman, L., & Schmidt, R. J. (2005). Development and validation of a coercive control measure for intimate partner violence: Final technical report. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/214438.pdf

Edin, K. E., Dahlgren, L., Lalos, A., & Högberg, U. (2010). “Keeping up a front”: narratives about intimate partner violence, pregnancy, and antenatal care. Violence Against Women, 16, 189–206. doi:10.1177/1077801209355703.

Giordano, P. C., Soto, D. A., Manning, W. D., & Longmore, M. A. (2010). The characteristics of romantic relationships associated with teen dating violence. Social Science Research, 39, 863–874. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.009.

Haskett, M. E., Ahern, L. S., Ward, C. S., & Allaire, J. C. (2006). Factor structure and validity of the parenting stress index–short form. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 302–312. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14.

Hayes, B. E. (2012). Abusive men’s indirect control of their partner during the process of separation. Journal of Family Violence, 27, 333–344. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9428-2.

Hellemans, S., Loeys, T., Dewitte, M., De Smet, O., & Buysse, A. (2015). Prevalence of intimate partner violence victimization and victims’ relational and sexual well-being. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 685–698. doi:10.1007/s10896-015-9712-z.

Holden, G. W., Stein, J. D., Ritchie, K. L., Harris, S. D., & Jouriles, E. N. (1998). Parenting behaviors and beliefs of battered women. In G. W. Holden, R. Geffner, & E. N. Jouriles (Eds.), Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and applied issues (pp. 289–334). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Holland, A. S., & McElwain, N. L. (2013). Maternal and paternal perceptions of coparenting as a link between marital quality and the parent-toddler relationship. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 117–126. doi:10.1037/a0031427.

Huth-Bocks, A. C., Krause, K., Ahlfs-Dunn, S., Gallagher, E., & Scott, S. (2013). Relational trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms among pregnant women. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41, 277–301.

Irwin, L. G., Thorne, S., & Varcoe, C. (2002). Strength in adversity: Motherhood for women who have been battered. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 34, 47–57.

Johnson, M. P. (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 12, 1003–1018. doi:10.1177/1077801206293328.

Karmaliani, R., Asad, N., Bann, C. M., Moss, N., Mcclure, E. M., Pasha, O., et al. (2009). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and associated factors among pregnant women of hyderbad, Pakistan. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 55, 414–424. doi:10.1177/0020764008094645.

Kelleher, K. J., Hazen, A. L., Coben, J. H., Wang, Y., McGeehan, J., Kohl, P. L., & Gardner, W. P. (2008). Self-reported disciplinary practices among women in the child welfare system: Association with domestic violence victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 811–818. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.004.

Kelly, U. A. (2009). “I’m a mother first”: the influence of mothering in the decision-making processes of battered immigrant Latino women. Research in Nursing & Health, 32, 286–297. doi:10.1002/nur.20327.

Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations, 49, 25–44.

Lapierre, S. (2010). Striving to be ‘good’ mothers: Abused women’s experiences of mothering. Child Abuse Review, 19, 342–357. doi:10.1002/car.1113.

Levendosky, A. A., Leahy, K. L., Bogat, G. A., Davidson, W. S., & von Eye, A. (2006). Domestic violence, maternal parenting, maternal mental health, and infant externalizing behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 544–552. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.544.

Lieberman, A. F., & Van Horn, P. (2005). Don't hit my mommy: A manual for child-parent psychotherapy. Washington, D.C.: Zero to Three Press.

Lieberman, A. F., & Van Horn, P. (2008). Psychotherapy with infants and young children: Repairing the effects of stress and trauma on early attachment. New York: Guilford Press.

Ludermir, A. B., Lewis, G., Valongueiro, S. A., Barreto do Araujo, T. V., & Araya, R. (2010). Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: A prospective cohort study. Lancet, 367, 903–910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60887-2.

Martin, S. L., Li, Y., Casanueva, C., Harris-Britt, A., Kupper, L. L., & Cloutier, S. (2006). Intimate partner violence and women’s depression before and during pregnancy. Violence Against Women, 12, 221–239. doi:10.1177/1077801205285106.

McGee, C. (1997). Children’s experiences of domestic violence. Child and Family Social Work, 2, 13–23. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2206.1997.00037.x.

Mechanic, M. B., Weaver, T. L., & Resick, P. A. (2008). Mental health consequences of intimate partner violence: A multidimensional assessment of four different forms of abuse. Violence Against Women, 14, 634–654. doi:10.1177/1077801208319283.

Moe, A. M. (2009). Battered women, children, and the end of abusive relationships. Journal of Women and Social Work, 24, 244–256. doi:10.1177/0886109909337374.

Moore, A. M., Frohwirth, L., & Miller, E. (2010). Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 1737–1744. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009.

Mullender, A., Hague, G., Imam, U., Kelly, L., Malos, E., & Regan, L. (2002). Children’s perspectives on domestic violence. London: Sage Publications.

O’Leary, K. D. (1999). Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. Violence and Victims, 14, 3–23.

Olds, D. L., Hill, P. L., O’Brien, R., Racine, D., & Moritz, P. (2003). Taking preventive intervention to scale: The nurse-family partnership. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 278–290. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80046-9.

Prinz, U., Nutzinger, D. O., Schulz, H., Petermann, F., Braukhaus, C., & Andreas, S. (2013). Comparative psychometric analyses of the SCL-90-R and its short versions in patients with affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 104–112. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-104.

Radford, L., & Hester, M. (2006). Mothering through domestic violence. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Reitman, D., Currier, R. O., & Stickle, T. R. (2002). A critical evaluation of the parenting stress index–short form (PSI-SF) in a head start population. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 384–392. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_10.

Ritchie, K. L., & Holden, G. W. (1998). Parenting stress in low income battered and community women: Effects on parenting behavior. Early Education and Development, 9, 97–112. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed0901_5.

Rivara, F. P., Anderson, M. L., Fishman, P., Reid, R. J., Bonomi, A. E., Carrell, D., & Thompson, R. S. (2009). Age, period, and cohort effects on intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 24, 627–638. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.24.5.627.

Rivera, E. A., Zeoli, A. M., & Sullivan, C. M. (2012). Abused mothers’ safety concerns and court mediators’ custody recommendations. Journal of Family Violence, 27, 321–332. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9426-4.

Rodriguez, M. A., Valentine, J., Ahmed, S. R., Eisenman, D. P., Sumner, L. A., Heilemann, M. V., & Liu, H. (2010). Intimate partner violence and maternal depression during the perinatal period: A longitudinal investigation of Latinas. Violence Against Women, 16, 543–559. doi:10.1177/1077801210366959.

Rosen, D., Seng, J. S., Tolman, R. M., & Mallinger, G. (2007). Intimate partner violence, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder as additional predictors of low birth weight infants among low-income mothers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 1305–1314. doi:10.1177/0886260507304551.

Ruggiero, K. J., Del Ben, K., Scotti, J. R., & Rabalais, A. E. (2003). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist-civilian version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 495–502. doi:10.1023/A:1025714729117.

Shea, E., & Tronick, E. Z. (1988). The maternal self-report inventory: A research and clinical instrument for assessing maternal self-esteem. In H. E. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Theory and research in behavioral pediatrics (vol. 4, pp. 101–139). New York: Plenum Press.

Shortt, J. W., Capaldi, D. M., Kim, H. K., & Laurent, H. K. (2010). The effects of intimate partner violence on relationship satisfaction over time for young at-risk couples: The moderating role of observed negative and positive affect. Partner Abuse, 1(2), 131–152. doi: 10.1891/1946–6560.1.2.131

Stampfel, C. C., Chapman, D. A., & Alvarez, A. A. (2010). Intimate partner violence and posttraumatic stress disorder among high-risk women: Does pregnancy matter? Violence Against Women, 16, 426–443. doi:10.1177/1077801210364047.

Stark, E. (2007). Coercive control: The entrapment of women in personal life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stern, D. (1995). The motherhood constellation. In Author, The motherhood constellation: A unified view of parent-infant psychotherapy (pp. 171–190). New York: Basic Books.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., & Warren, W. L. (2003). The conflict tactics scales handbook. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Taillieu, T. L., & Brownridge, D. A. (2009). Violence against pregnant women: Prevalence, patterns, risk factors, theories, and directions for future research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 14–35. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.07.013.

Thiara, R. K. (2010). Continuing control: Child contact and post-separation violence. In R. K. Thiara, & A. K. Gill (Eds.), Violence against women in south Asian communities: Issues for policy and practice (pp. 156–181). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Tolman, R. M. (1989). The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims, 4, 159–177.

Tubbs, C. Y., & Williams, O. J. (2007). Shared parenting after abuse. In J. L. Edleson, & O. J. Williams (Eds.), Parenting by men who batter: New directions for assessment and intervention (pp. 19–44). New York: Oxford University Press.

Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Breiding, M. J. (2013). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Walton-Moss, B. J., Manganello, J., Frye, V., & Campbell, J. C. (2005). Risk factors for intimate partner violence and associated injury among urban women. Journal of Community Health, 30, 377–389. doi:10.1007/s10900-005-5518-x.

Weathers, F., Litz, B., Herman, D., Huska, J., & Keane, T. (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. San Antonio, TX: Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

Williams, S. L., & Frieze, I. H. (2005). Patterns of violent relationships, psychological distress, and marital satisfaction in a national sample of men and women. Sex Roles, 52, 771–784. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-4198-4.

Young, B. J., & Furman, W. (2013). Predicting commitment in young adults’ physically aggressive and sexually coercive dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 3245–3264. doi:10.1177/0886260513496897.

Zolotor, A. J., Theodore, A. D., Coyne-Beasley, T., & Runyan, D. K. (2007). Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Overlapping risk. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 7, 305–321. doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhm021.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grants from the American Psychoanalytic Association and from Eastern Michigan University to the second author. The authors would like to thank the Parenting Project research assistants for their invaluable help with data collection as well as thank the families who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahlfs-Dunn, S.M., Huth-Bocks, A.C. Intimate Partner Violence Involving Children and the Parenting Role: Associations with Maternal Outcomes. J Fam Viol 31, 387–399 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9791-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9791-x