Abstract

During the medieval and early modern periods the Middle East lost its economic advantage relative to the West. Recent explanations of this historical phenomenon—called the Long Divergence—focus on these regions’ distinct political economy choices regarding religious legitimacy and limited governance. We study these features in a political economy model of the interactions between rulers, secular and clerical elites, and civil society. The model induces a joint evolution of culture and political institutions converging to one of two distinct stationary states: a religious and a secular regime. We then map qualitatively parameters and initial conditions characterizing the West and the Middle East into the implied model dynamics to show that they are consistent with the Long Divergence as well as with several key stylized political and economic facts. Most notably, this mapping suggests non-monotonic political economy dynamics in both regions, in terms of legitimacy and limited governance, which indeed characterize their history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Around the year 1000 C.E., the Muslim Middle East was far ahead of Christian Western Europe in terms of socio-economic development. By the dawn of the industrial period (circa 1750), however, the Middle East severely lagged behind along several dimensions, including technology, innovation, literacy, wages, and financial development (Mokyr, 1990; Kuran, 2011; Özmucur & Pamuk, 2002; Bosker et al., 2013; Rubin, 2017). This is what Timur Kuran (2011) calls the Long Divergence. Urban population is one metric illustrating the socio-economic divergence, as seen in Fig. 1.Footnote 1

Urban Population, 800–1800. Data source: Bosker et al. (2013)

The historical narratives in the literature consistently interpret the economic divergence between Western Europe and the Middle East as the outcome of institutional and technological progress brought about or hindered by different strategies political authorities adopted to sustain their political support and to enlarge fiscal capacity in the medieval and early modern periods. Specifically, Kuran (2011) identifies the root cause of Middle East stagnation in Islamic law or Sharia—especially its inheritance system and partnership law—that governed most economic activities. Rubin (2017) argues that the persistence of Islamic law is at least partly a consequence of the role of the political power ceded to Muslim religious authorities due to their ability to provide legitimacy. This power was in turn used to block important technological and economic advancements, a leading example being the printing press. In Europe, on the other hand, the Catholic Church had a much weaker legitimating role, and economic elites in parliaments developed laws and policies that favored economic development. Blaydes and Chaney (2013) posit that Western European rulers had to rely on feudal institutions for tax collection and military recruitment. This led to a balance of power more favorable to local economic elites, which promoted economic growth in the long run. Muslim sultans, on the other hand, were not constrained by secular economic elites, in large part due to their access to slave soldiers, who satisfied both fiscal and military needs.

Motivated by these narratives, we propose a political economy model which aims at elucidating the historical mechanisms possibly responsible for the Long Divergence while mapping qualitatively into relevant historical facts.Footnote 2 Specifically, the model centers on the interactions between political authorities, secular and clerical elites, and civil society. It captures three fundamental elements of the socio-economic environment under study. The first concerns the role of religious legitimacy. Religious elites provide services which can shape the moral beliefs of the religious component of civil society. Political authorities can leverage this ability of religious elites to legitimate rule by delegating political power to them. The second element is a trade-off between religious legitimacy and religious proscriptions. These proscriptions may often end up dampening economic activity as, arguably, in the case of Islamic law in business affairs. The third element concerns the role of secular elites in enhancing the state’s fiscal capacity. The delegation of political power from rulers to secular elites results in limited governance, which increases tax revenues by ceding tax collection power to those with greater capacity to collect it.

At the heart of the model is a complementarity between religious legitimacy and the profile of religious values in civil society. Religious agents see taxation as more legitimate than the non-religious portion of the population. A higher fraction of religious agents in the population therefore augments the political incentives for the ruler to delegate power to clerics to increase legitimacy; and in turn a more religious institutional set-up reinforces the incentives of religious individuals to transmit their values across generations, increasing their relative share in the population.

The reinforcement of religious cultural values and the political power of religious elites fundamentally affects socio-economic dynamics. The dynamics display two types of stationary states: (i) a religious regime where clerics have substantial political power, they legitimate the ruler, and religious cultural values are predominant in the population; and (ii) a secular regime in which clerics have little political power and secular beliefs are predominant. Allowing for limited governance induces a further characterization of the secular regime in which rulers delegate political power to secular elites at the expense of religious clerics.

The structural parameters of the socio-economic environment (e.g., the legitimating capacity of religious elites) and the initial conditions (e.g., the initial share of religious individuals in civil society) determine both the characteristics of the transitory dynamics of society as well as whether these dynamics converge to the religious or the secular stationary states. Importantly, these dynamics are not necessarily monotonic. In a subset of the basin of attraction of the religious state, for instance, and specifically when religious values are not predominant initially, rulers will not seek legitimacy from religious authorities for some time, only to change strategies after religious values are spread enough in the population. Conversely, when religious values are initially predominant, non-monotonic dynamics in which rulers delegate power to clerical elites for some time before delegating power to secular elites occur in the basin of attraction of the secular stationary state. In both cases, the dynamics are characterized by a “horse race” between cultural and institutional change.

We argue that this model provides a unitary account of the historical mechanisms which might have contributed to the Long Divergence. To this end, we first map various historical stylized facts into their structural parameters and initial conditions. We then show that the implied dynamics of the model are not only consistent with the Long Divergence, but also produce convergence paths with qualitative characteristics which can be historically identified in the growth paths of Western Europe and the Middle East.Footnote 3

The main structural parameter of interest is the legitimating ability of religious elites. As discussed in detail in Sect. 4.2, we posit that—due to the contexts in which these religions were born—Christianity was relatively weak at legitimating rule, while the opposite was true for Islam in the Middle East (Feldman, 1997; Rubin, 2011, 2017).Footnote 4 The most relevant initial conditions in the model are the initial religious cultural values in the population. Christianity was widespread in the former Roman lands (i.e., religious cultural beliefs were widespread), while this was not the case for Islam in the Middle East, at least at the beginning of the period under consideration.Footnote 5 Under this mapping, the dynamics of the model are consistent with the Middle East and the West converging, respectively, to the religious and secular stationary states and with the historical narratives regarding the Long Divergence. The Middle East, in a religious stationary state, is expected to be less economically vibrant in the long-run due to the effects of religious proscriptions on economic activity. The main mechanisms driving the convergence to the distinct stationary states are (i) the persistent use of religious legitimacy in the Middle East but not in Western Europe; and (ii) the lack of limited governance in the Middle East relative to the West.

Furthermore, our mapping of historical facts into parameters and initial conditions suggests a tension between the structural ability of religious elites to provide legitimacy and the initial fraction of the population with religious beliefs—for both the Middle East and the West. This tension gave rise to the non-monotonic convergence dynamics the model allows for: the incentives to seek religious legitimacy were initially high in the Christian West, to be overtaken because of the limited legitimating ability of Christianity; while the opposite was the case in the Islamic Middle East. This non-monotonicity of the dynamic paths is consistent with the historical political economy patterns in the two regions. As discussed in much more detail in Sect. 4.3, in Western Europe, following the fall of the Roman Empire, rulers of the Germanic “follower kingdoms” either converted to Christianity or promoted it, as for instance was the case of the Frankish king Clovis (r. 481–509). These strategies characterized Western Europe until the 11th century, when the re-birth of commerce gave rise to independent cities and increased tensions between the religious and secular elite. In the Middle East, early rulers established law and order, administered the state, and encouraged loyalty to the empire by sending “proto-kadis” (religious judges) to the provinces. After the religious establishment consolidated in the ninth century, and especially after the rise of the madrasa system in the 11th century, religious authorities were the primary agents capable of determining whether rulers acted in accordance with Islam.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2 we lay out the basic socio-economic environment in terms of preferences and technologies of the ruler, clerics, and civil society. We also describe the space of available policy interventions. In Sect. 3 we study the societal equilibrium for each generation t (Sect. 3.1) and the processes of institutional and cultural change across generations (Sects. 3.2 and 3.3, respectively). In Sect. 4 we map the model into historical facts and narratives. In Sect. 5 we extend the model to study equilibria and dynamics when we allow for political decentralization to secular elites. Section 6 concludes.Footnote 6

2 Ruler, clerics, and civil society

We consider a political economy model of the distribution of power between three types of agents: a ruler, religious clerics, and civil society.Footnote 7 Religious legitimacy is an equilibrium phenomenon. It results from an institutional process of delegation of power and it depends on the profile of religious values in the population, the efficiency of the clerics’ “legitimating technology”, and the degree of restrictiveness of religious proscriptions imposed by clerics.Footnote 8.

Let \(t=0,1, \ldots\) index generations. All agents only live for one generation. As a consequence, the game played between the ruler, clerics, and civil society is a series of one-shot games in which behavior is not forward-looking with respect to institutional or cultural evolution.Footnote 9

2.1 Civil society

Each generation consists of a continuum [0, 1] of citizens. Civil society is composed of two types i of citizens: religious individuals (\(i=Re\)) in proportion \(q_{t}\) in generation t, and secular individuals (\(i=S\)) in proportion \(1-q_{t}\). Citizens employ effort in production activities. Total production is \(E_{t}=q_{t}e_{Re,t}+(1-q_{t})e_{S,t}\), where \(e_{i,t},\;i=Re,S\) is the per-capita work effort employed by an individual of type i in generation t.

2.2 Ruler and clerics

The ruler lives off taxing civil society at a tax rate \(\tau _{t}\). The tax base to which the ruler has access is the total production of citizens, \(E_{t}\). The ruler also contributes to building and maintaining religious infrastructure, \(m_{t}\ge 0\), for the clerics to provide religious services. The total religious services provided for society are \(m_{t} \cdot \alpha _{c,t}\), where \(\alpha _{c,t}\ge 0\) is the effort of the (representative) cleric at time t. The building of religious infrastructure has cost \(C(m_{t})\) that the ruler pays for. Meanwhile, clerics pay for the daily maintenance costs \(F(m_{t})\) of religious infrastructure.Footnote 10

2.3 Legitimacy

Clerics can provide the ruler with legitimacy through religious services which facilitate governance and obedience for religious individuals. We focus on the role legitimacy plays in tax collection (e.g., Coşgel and Miceli 2009, Levi and Sacks 2009, Wintrobe 1998). In particular, citizens are more likely to defer to tax authorities when governance is viewed as legitimate, and they likewise may feel better about paying taxes to a divinely sanctioned political authority.Footnote 11 This is a source of political power for religious authorities. However, this power is limited by the fact that religious legitimacy only operates on the religious component of civil society. In our formulation, religious individuals, when taxed by the ruler, subjectively perceive a tax rate \(\tau _{Re,t}^{e}\) smaller than the actual \(\tau\) chosen by the ruler and decreasing in the religious effort of clerics, \(\alpha _{c,t}\):

For secular individuals, \(\tau _{S,t}^{e}=\tau\).Footnote 12

As a consequence, the total level of taxes collected is increasing in the cleric’s effort, \(\alpha _{c,t}\), and the efficiency of the legitimating technology. We denote the exogenous component of the legitimating technology by \(\theta \in [0,1]\), and we interpret it as the efficiency of religious legitimacy in encouraging compliance with authority.

2.4 Proscriptions

Religious services have an indirect cost, in that they require the imposition of various proscriptions (i.e., regulations and constraints) on individual behavior. These proscriptions are imposed on both religious and secular individuals.Footnote 13 Examples of these types of proscriptions are inheritance laws, prohibitions on technologies such as printing, and usury restrictions on the entire credit market. We capture the effect of religious proscriptions by assuming that the cost of individual production effort is

The parameter \(\phi >0\) represents the degree of restrictiveness of religious proscriptions on economic activities.Footnote 14

2.5 Preferences

Preferences of the agents in this society in any generation t are as follows. The ruler has utility

Clerics derive utility \(m_{t} \cdot \alpha _{c,t}\) from religious services, at effort cost \(\Psi (\alpha _{c,t})\).Footnote 15 The utility of the clerics therefore is

Finally, the utility of agents of type \(i=Re, S\) in civil society is

We assume the cost functions C(.), F(.) and \(\Psi (.)\) are increasing and convex in their argument.Footnote 16

This setup establishes—somewhat starkly—one of the model’s fundamental building blocks: the trade-off between religious legitimacy and religious proscriptions with respect to the size of the taxable surplus. Legitimacy increases the incentive to provide effort for the religious (or alternatively, lowers their incentive to evade taxation), but comes at the cost of lowered productivity due to proscriptions.

2.6 Policy

Policy choices are not necessarily the sole responsibility of the ruler. They are, in general, the outcome of a collective choice problem in any given generation t, reflecting the political power and preferences of the three groups, and representing indirectly the political economy process in society (Bisin & Verdier, 2017; Paniagua & Vogler, 2022).Footnote 17 In other words, policies are the outcome of a “bargain” implicit in the institutional structure of society. More specifically, this is how the choice of religious infrastructure \(m_{t}\), over which both religious clerics and civil society have a say, is made in our model.Footnote 18

The relative political power of the groups is captured by their respective weight in the social welfare function \(W_{t}\), which is the objective of policy choices.Footnote 19 Specifically, the social welfare function \(W_t\) to be maximized by the policy choice \(m_t\) is:

Fixing the relative power of the ruler (to \(\frac{1}{2}\)),Footnote 20 the power of clerics and civil society is, respectively, \(\frac{\lambda _t}{2}\) and \(\frac{1-\lambda _t}{2}\) with \(\lambda _t\in [0,1]\).

Each generation’s societal equilibrium will obtain as the ruler, clerics, and agents in civil society choose \(\tau _{t}\)(\(\le\) \({\overline{\tau }}\)),Footnote 21\(\alpha _{c,t}\), and \(e_{i,t}\) (for \(i=Re,S,\)) to maximize their utility given by (3), (4), and (5), respectively. The policy choice \(m_{t}\) is determined by the institutional bargaining process to maximize (6). At a societal equilibrium in each generation t, the ruler, policy-maker, clerics, and civil society, take as given i) the distribution of power between the groups in society, \(\lambda _t\); as well as ii) the distribution of religious and secular types in civil society, \(q_t\). But both the distribution of power and the distribution of types in civil society are endogenously determined. In the next section, we study first the societal equilibrium for any t, and then the dynamics of \(\lambda _t\) and \(q_t\) in the model.

3 Societal equilibrium and dynamics

At any time t, for a given institutional power structure and population profile of religious and secular individuals, the societal equilibrium is a Nash equilibrium of the simultaneous game between the ruler, policy-maker, clerics, and civil society. The non-cooperative nature of choices captures the idea of a public choice environment plagued by externalities and lack of commitment, whereby policy-makers and agents do not internalize the full impact of their behavior on society.

Institutional change arises as a mechanism to internalize the externalities associated with the political process, given the changing cultural composition of society (Bisin & Verdier, 2017; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2019; Iyigun et al., 2021). Cultural dynamics derive from purposeful inter-generational transmission, emanating from parental socialization and imitation of society at large (Bisin & Verdier, 2001, 2017).

3.1 Societal equilibrium

At a societal equilibrium for generation t, the choices of \(\tau _{t}\), \(\alpha _{c,t}\), \(e_{i,t}\) (\(i=Re,S\)), and \(m_{t}\) constitute a Nash equilibrium, denoted by \(\left\{ \tau _{t}(\lambda _{t}),m_{t}(\lambda _{t}),\alpha _{c,t}(\lambda _{t}),e_{S,t}(\lambda _{t}),e_{Re,t}(\lambda _{t})\right\}\).Footnote 22

It is easy to see that the equilibrium tax rate \(\tau _{t}(\lambda _{t})\) is equal to its maximum possible value \({\overline{\tau }}\), indicating fully extractive taxation.Footnote 23 In order to simplify notation, we write \(\tau\) instead of \({\bar{\tau }}=\tau _{t}(\lambda _{t})\) in the remainder of the paper. The comparative statics at equilibrium in any period t are summarized in the following Lemma. For notational convenience, we suppress the time subscript t in the rest of this section.

Lemma 1

(Religious infrastructure) The equilibrium investment in religious infrastructure, \(m(\lambda )\), and the equilibrium effort of the clerics, \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda )\), are increasing in \(\lambda\) and independent of \(\theta\) and \(\phi\).

When the weight of the clerics in social choice increases, so does the marginal benefit of provisioning the religious infrastructure m. In turn, clerics increase their own effort in provisioning religious services \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda )\). Since the weight of the clerics in social choice is \(\frac{\lambda }{2}\), both \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda )\) and \(m(\lambda )\) increase with \(\lambda\).

In the model, clerics do not derive utility from imposing proscriptions on economic activity nor from legitimating the ruler. Hence, the investment in religious infrastructure \(m(\lambda )\) and the provision of the religious services \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda )\) are independent from \(\theta\) and \(\phi\).

Lemma 2

(Labor effort) The equilibrium effort of secular individuals \(e_{S}(\lambda )\) is decreasing in \(\lambda\) and \(\phi\) and is independent of \(\theta\). On the other hand, as long as \(\theta \ge \frac{\phi (1-\tau )}{\tau }\), the equilibrium effort of religious individuals \(e_{Re}(\lambda )\) is increasing in \(\lambda\) and \(\theta\), and is decreasing in \(\phi\).

When the efficiency of the clerics to legitimate the ruler \(\theta\) increases, so does the effort of religious individuals who subjectively perceive a lower tax rate. By contrast, the efficiency of the legitimating technology has no effect on the effort of secular individuals. An increase in the degree of restrictiveness of religious proscriptions, \(\phi\), leads to lower efforts from both religious and secular individuals, as harsher proscriptions decrease individuals’ labor productivity.

The political weight of the clerics affects labor efforts through \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda )\), their equilibrium effort. While more effort from the clerics makes secular individuals reduce their own labor effort—through costly regulations and prohibitions \(\phi\)—when \(\theta \ge \frac{\phi (1-\tau )}{\tau }\), clerics have the opposite effect on the labor effort of religious individuals \(e_{Re}\). This is because when clerics provide more effort, religious individuals perceive a lower tax rate. Despite costly religious regulations, they increase their effort due to higher investments in religious infrastructure. In order to make this key difference between secular and religious individuals stark, we make the following Assumption:

Assumption 1

\(\theta \ge \frac{\phi ( 1-\tau )}{\tau }\).

We denote the tax base as \(E(\lambda )=qe_{Re}(\lambda )+(1-q)e_{S}(\lambda )\). From the two previous Lemmas, we deduce the following result:

Lemma 3

(Tax base) Under Assumption 1, the tax base is increasing in q and \(\theta\) and it is decreasing in \(\phi\). It increases with \(\lambda\) as long as \(q\ge \frac{\phi (1-\tau )}{\tau \theta }\).

While religious infrastructure increases the scope of religious proscriptions, it also positively affects the effort of the religious individuals under Assumption 1. Hence, when religious individuals are sufficiently numerous, the latter effect dominates, and the tax base \(E(\lambda )\) increases with the effort of the clerics \(\alpha _c(\lambda )\), so it increases with \(\lambda\). Similarly, since \(\theta\) positively affects the labor effort of religious individuals, it also positively affects the tax base. Religious proscriptions \(\phi\) negatively affect the tax base, as they decrease labor efforts. The tax base increases with the fraction of religious q, who provide greater effort than their secular counterparts.

3.2 Institutional dynamics

Each generation brings about institutional change in the relative power delegated to clerics and civil society in the future. That is, at the end of any generation t, \(\lambda _{t+1}\) is chosen from the point of view of the social welfare function with weight \(\lambda _t\).Footnote 24 In other words, institutions are exogenous from the perspective of all players at any point in time but change over time to reduce externalities associated with the decisions made by policymakers.Footnote 25 More formally, at any time t, given institutions \(\lambda _{t}\), future institutions \(\lambda _{t+1}\) are designed as the solution to:

Institutional change between periods t and \(t+1\) therefore internalizes two externalities that are not taken into account by the optimal decisions characterizing the Nash equilibrium of period t. The first one relates to the fact that the provision of religious infrastructure m grants legitimacy to the ruler, reducing the subjectively perceived tax rate for religious individuals. The second is the fact that it also has a depressing effect on labor productivity via proscriptions. Hence, increased provision of the religious good m not only affects the utility of the clerics, but also feeds back into the utility of both the ruler and the citizens. Solving the optimization problem (7), we obtain the following result:

Proposition 1

The solution \(\lambda _{t+1}\in [0,1]\) to optimization problem (7) is unique. The solution is characterized by a threshold \({\overline{q}}( \lambda _t)\in [0,1]\) such that,

Furthermore, the threshold \({\overline{q}}(\lambda _{t})\) is decreasing in \(\theta\) and increasing in \(\phi\).

The uniqueness result follows from the convexity of the optimization problem. Whether more power is delegated to the clerics over time depends on the fraction of religious individuals \(q_{t}\). A larger weight to clerics \(\lambda _{t+1}>\lambda _{t}\) increases their effort \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda _{t+1})\). This in turn increases the utility of the ruler \(U_{r}\), who benefits from a larger tax base (Lemma 3). When the religious are sufficiently numerous, this also increases the total welfare of the citizens \(q_{t}U_{Re}+(1-q_{t})U_{S}\). In such a case, while secular individuals suffer from religious proscriptions, civil society as a whole can still benefit from higher effort from the clerics. Religious individuals are better off when they perceive a lower tax rate and they comprise a large enough share of the population.Footnote 26

When the severity of religious proscriptions \(\phi\) increases, so does the cost to the ruler of using religious legitimacy as a means of extracting resources from the population. When clerics are efficient at legitimating the ruler, i.e. when \(\theta\) increases, delegating power to the clerics enables the ruler to extract more resources and lowers the perceived cost of effort of the religious. As a result, the parameter space over which \(\lambda _{t}\) increases expands, so \({\overline{q}}\) decreases.

3.3 Cultural dynamics

Cultural dynamics are modeled as purposeful inter-generational transmission via parental socialization and imitation of society at large (Bisin & Verdier, 2001, 2017). Direct vertical socialization to the parent’s trait \(i\in \{Re,S\}\) occurs with probability \(d_{i}\). If a child from a family with trait i is not directly socialized, which occurs with probability \(1-d_{i}\), he/she is horizontally/obliquely socialized by picking the trait of a role model chosen randomly in the population.Footnote 27 The probability \(P_{ij}\) that a child in group i is socialized to trait j writes as:

with \(q_{Re}=q\) and \(q_{S}=1-q\). We assume that the probability of direct socialization \(d_{i}\) is the solution of a parental socialization problemFootnote 28 in which: a) parents are paternalistic (i.e., imperfectly altuistic) and have a bias for children sharing their own cultural trait; b) such paternalistic bias writes as \(\Delta V_{i}(\lambda _{t})=V_{ii}(\lambda _{t})-V_{ij}(\lambda _{t})\), where \(V_{ij}(\lambda _{t})=U_{i}(e_{j}(\lambda _{t}))\) is the utility perceived by a type i parent of having a type j child, for \(i,j\in \{Re,S\}\) and \(j\ne i\); c) parents of type \(i\in \{Re,S\}\) have socialization costs that are increasing and convex in \(d_{i}\); d) religious infrastructure \(m_{t}\) may act as a complementary input to the transmission effort \(d_{Re}\) of religious families in the socialization of children to the religious trait.

More specifically, denote \(h_{Re}(d_{Re},m_{t})\) the socialization cost of religious families and \(h_{S}(d_{S})\) the socialization cost of secular families. Then religious parents solve the following socialization problem:

while secular parents solve the following socialization problem:

As shown in the Appendix in supplementary file, the solution to (9) provides the equilibrium socialization effort of religious families \(d_{Re,t}^{*}=D_{Re}\left[ (1-q_{t})\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t}),m(\lambda _{t})\right]\), which is an increasing function of both \((1-q_{t})\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})\) and \(m(\lambda _{t})\). Similarly, the solution of (10) defines the equilibrium socialization effort of secular families \(d_{S,t}^{*}=D_{S}\left[ q_{t}\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})\right]\), which is an increasing function of \(q_{t}\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t}).\) In addition, the dynamics of the proportion of the population with the religious trait is characterized by the following “cultural replicator” dynamics:

In equation (11), the term

can be interpreted as the relative “cultural fitness" of the religious trait in the population. This term is frequency dependent (i.e., it depends on the state of the population \(q_{t}\)). It is also affected by the institutional environment \(\lambda _{t},\) as this variable interacts with the process of parental cultural transmission both through paternalistic motivations \(\Delta V_{i}(\lambda _{t})\), and through the provision of religious infrastructure \(m_{t}=m(\lambda _{t})\) as a complementary input to religious family socialization.

In other words, there is a complementarity between religious legitimacy and the profile of religious values in the population. We deduce the following result:

Proposition 2

There exists a threshold \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\) such that

Furthermore, the threshold \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\) is increasing in \(\theta\) and \(\lambda _{t}\) and decreasing in \(\phi\).

Because the process of cultural transmission (8) is characterized by cultural substitution between vertical and oblique transmission, the relative “cultural fitness" of the religious trait \(D(q_{t},\lambda _{t})\) is decreasing in the frequency \(q_{t}\) of religious individuals in the population (Bisin & Verdier, 2001). Consequently, the proportion \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\) such that \(D(q^{*}(\lambda _{t}),\lambda _{t})=0\) is the unique attractor of the cultural dynamics in (11). When the fraction of religious individuals \(q_{t}\) is above (resp. below) \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\), then it decreases (resp. increases) in order to converge in the direction of \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\).

An increase in the political weight of the clerics \(\lambda _{t}\) affects cultural transmission in two ways, through its effect on socialization incentives \(\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})\) and \(\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})\) and through its effect on religious infrastructure, \(m=m(\lambda _{t})\). On the one hand, an increase in \(\lambda _t\) promotes the clerics’ effort \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda _{t})\) and consequently leads to a lower perceived tax rate \(\tau _{Re}^{e}\) by religious individuals. The labor effort choice of religious and secular individuals is, therefore, further apart and, consequently, the incentives of parents to socialize their children to their own cultural trait, \(\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})\) and \(\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})\), are larger in both groups.Footnote 29 However, when the socialization effort of religious parents is more sensitive to these incentives than the effort of secular parents, the religious trait is relatively more successfully transmitted than the secular trait, and \(D(q_{t},\lambda _{t})\) is shifted up with an increase in \(\lambda _{t}\). An increase in \(\lambda _{t}\) also increases the amount of religious infrastructure \(m=m(\lambda _{t})\). When such infrastructure enters as a complementary input in the socialization process of the religious trait, then again religious parents tend to socialize more intensively than secular ones when m increases. The religious trait has consequently higher cultural fitness than the secular trait and again \(D(q_{t},\lambda _{t})\) is shifted up with \(\lambda _{t}\). In either situation, the diffusion of the religious trait is favored by an increase in \(\lambda _{t}\), and \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\) becomes larger.

A change in the other parameters \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) affects the relative cultural fitness of the religious trait only through their induced changes on the paternalistic motives \(\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})\) and \(\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})\). For instance, a higher efficiency of the clerics \(\theta\) tends to widen the gap between the optimal work effort of a religious individual compared to that of a secular individual. As a consequence, an increase in \(\theta\) shifts up both \(\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})\) and \(\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})\). As mentioned above, when religious parents are more sensitive to paternalistic motives than secular parents, these shifts lead religious parents to socialize more intensively than secular parents, and religious values are passed from generation to generation with a higher intensity. This results in a higher value of \(q^{*}(\lambda _{t})\). Conversely, a higher value of religious proscriptions \(\phi\) dampens the impact of work effort on economic outcomes. Consequently, behavioral differences induced by cultural traits are less relevant from a utility point of view. This in turn reduces the paternalistic motives \(\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})\) and \(\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})\) of religious and secular parents. The effect of a change in proscriptions \(\phi\) on cultural evolution is then qualitatively the opposite of that of a change in \(\theta\).

4 Model dynamics and historical narrative

In this section we draw out the implications of the model with regards to the joint dynamics of culture and institutions and match them with various elements of the historical narrative regarding Middle Eastern and Western European political economy during the medieval and early modern periods.

In Sect. 4.1 we represent the dynamics of the model by a phase diagram. To this end, we exploit the characterization we obtained in the previous section of the dynamics’ stationary states, their stability properties, and their basins of attraction, as a function of structural parameters and initial conditions. In Sect. 4.2 we lay out relevant historical information to draw a qualitative mapping of structural parameters and initial conditions for the Middle East and the West into the basins of attraction of the different dynamics identified by the model. Finally, in Sect. 4.3 we match the model’s implied dynamics for these two regions to the historical narrative regarding the Long Divergence as well as other characteristics of the political economy patterns of the history of these regions.Footnote 30

4.1 The joint dynamics of culture and institutions

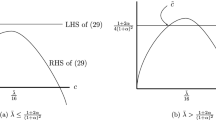

Under the conditions of Propositions 1 and 2, we can represent the joint cultural and institutional dynamics in the phase diagram of Fig. 2. The solid black line represents the threshold of the institutional dynamics \({\overline{q}}(\lambda _{t})\). The dotted line represents the threshold \(q^{*}(\lambda )\) associated with the cultural dynamics.Footnote 31 The arrows in Fig. 2 depict the joint dynamics of culture and institutions, given our results in Propositions 1 and 2.

4.1.1 Stationary states

As described in the figure, the joint dynamics of culture and institutions in this society display two stable steady states and one saddle point steady state.Footnote 32 The first stable steady state could be characterized as a religious regime represented by point A in Fig. 2, where the ruler is legitimated by religion, clerics have significant political power (\(\lambda _t\) is high), taxation is high (the tax rate \(\tau\) is maximal and the tax base E is high), and the share of religious individuals in civil society is high (q is high). The second stable steady state, point B in Fig. 2, could be characterized as a secular regime where the ruler is not legitimated by religion, clerics have little political power (\(\lambda _t\) is zero), taxation is limited (the tax rate \(\tau\) is maximal but the tax base E is small), and civil society is secular (q is small). Two mechanisms characterize the dynamics.

4.1.2 Monotonic convergence paths

In regions I and IV of Fig. 2, the ruler’s option to rely on religious legitimacy to increase tax capacity induces a fundamental complementarity between religious legitimacy and the profile of religious values in the population. On the one hand, religious elites provide services to the religious component of civil society, which shape civil society’s moral beliefs that support an obligation to obey the ruler, which in turn lowers the subjective tax rate for the religious. Institutions delegating power to clerics (i.e., high \(\lambda _t\)) therefore reinforce the incentives of religious individuals to transmit their values. This in turn increases the relative share of the religious in the population. In addition, a higher fraction of religious individuals in the population augments the political incentives for the ruler to delegate power to clerics to increase legitimacy. This complementarity operates to produce dynamics converging to the religious regime, as represented by point A in Fig. 2 or to the secular regime, as represented by point B. In these regions, the complementarity between culture and institutions locks-in society to one of the two stable equilibria.

4.1.3 Non-monotonic convergence paths

In regions II and III of Fig. 2, the dynamics are not characterized by complementarity. In these regions of the phase diagram, a “horse race” arises between cultural and institutional change. The “winner” of the horse race determines which stable equilibrium—religious or secular—emerges in the long run. In region II, religious individuals are insufficiently numerous and \(\lambda _{t}\) decreases over time. At the same time, religious values grow: as the religious trait is not widespread, religious individuals invest more in direct socialization. Depending on the speed of institutional change relative to cultural change, the joint dynamics can either reach region I or region IV.

Region II may give rise to a transitory path to the religious equilibrium when the religious population grows fast despite the political weight of the clerics decreasing over time. This might occur because, being in the minority, religious parents have higher incentives to exert effort transmitting their cultural trait to their child. In this case, religious individuals become sufficiently numerous at some point that the course of institutional change is reversed, and the political power of religious clerics starts to grow after a transitory period. In region III, religious individuals are sufficiently numerous for the political power of the religious clerics to increase over time. But the religious population is too large, so secular individuals invest more in direct socialization. Again, depending on the speed of institutional change relative to cultural change, either region I or region IV could be reached by the joint dynamics. If the religious population decreases faster than religious institutions grow, we can expect the joint dynamics to reach region IV. In this case, the religious population becomes so low after a transitory period that the political weight of the clerics decreases over time and equilibrium B is reached in the long-run.

4.1.4 Comparative dynamics

The basin of attraction of each stationary state—the subset of initial conditions from which the dynamical system converges to this state in the phase diagram in Fig. 2—depends on the parameters of the society. Since the size of each basin of attraction can be interpreted as a likelihood of reaching that stationary state, it is important for our analysis to characterize their dependence on the efficiency of the legitimating technology of the clerics, \(\theta\), and the degree of restrictiveness of the religious proscriptions imposed by the clerics, \(\phi\):

Proposition 3

The size of the basin of attraction of the religious (resp. secular) stationary state is increasing (resp. decreasing) in religious legitimacy \(\theta\) and decreasing (resp. increasing) in the restrictiveness of religious proscriptions \(\phi\).

As an illustration, consider the basin of the religious state. A higher efficiency of the clerics \(\theta\)—by definition—decreases the subjectively perceived tax rate of the religious. As a consequence, religious parents have a higher willingness to transmit their cultural values inter-generationally. At the same time, clerics become more important in the institutional apparatus, as they increase social welfare by (i) lowering the perceived cost of effort and (ii) increasing the rents extracted by the ruler. Therefore, the complementarity between the spread of religious values and institutional changes delegating power to the clerics is reinforced when \(\theta\) is higher; and the size of the basin of attraction of the religious state is enlarged.

On the other hand, when the degree of religious proscriptions \(\phi\) increases, the cost for the ruler from using religious legitimacy as a means of extraction also increases. The threshold \({\overline{q}}(\lambda _t)\) consequently increases. Similarly, greater religious proscriptions dampen the impact of work effort on economic outcomes. As a result, behavioral differences induced by cultural traits are less relevant. To the extent that religious parents are more sensitive to paternalistic motives than secular parents, these shifts lead religious parents to socialize less intensively than secular parents, so the threshold \(q^*(\lambda _t)\) associated with the cultural dynamics decreases. As a consequence, the complementarity between the spread of religious values and institutional changes delegating power to the clerics is weakened; and the size of the basin of attraction of the religious state is reduced.

4.2 Historical parameters and initial conditions

In the historical context we study—Western Europe and the Middle East over the period starting from the end of the Western Roman Empire in the West and the emergence of Umayyad Caliphate in the Middle East until the onset of the Reformation in Europe and the capture of the Egyptian Mamluk Empire by the Ottoman Empire—the historical literature has identified several key differences between the regions.

4.2.1 Parameters \(\theta\) and \(\phi\)

We contend, for reasons given below, that Muslim religious authorities had greater exogenous capacity to legitimate (\(\theta\)) than their Christian counterparts. It is worth noting that there is dispute among historians regarding the degree to which early Muslim rulers, especially the Umayyad Empire (661–750) employed religious legitimacy.Footnote 33 For instance, Rubin (2003, p. 87-99) argues that the Umayyads based their legitimacy on their right of succession, not specifically their religious credentials. Bessard (2020, ch. 1, 9) shows that the Umayyads and Abbasids sponsored markets to bolster their legitimacy among merchants. Yet, these insights do not undermine our claim. The key distinction made in the model is between the exogenous legitimating technology (\(\theta\)) and the endogenous political power (\(\lambda\)) devolved to religious authorities. The dispute in the literature primarily concerns the latter. For reasons we discuss below, the view that early Muslim empires limited their use of religious legitimacy is consistent with our model.

The primary reason provided in the literature why the exogenous legitimating technology of Islam was relatively greater than in Christianity stemmed from the environment in which the religions were born. Christianity was born in the Roman Empire and was in no position to legitimate the emperor. Early Christian doctrine is reflective of the low legitimating capacity of Christianity (Feldman, 1997; Rubin, 2011). For instance, Jesus famously said “Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21). Meanwhile, Islam formed conterminously with expanding empire, and there are numerous important Islamic dictates specifying the righteousness of following leaders who act in accordance with Islam (Hallaq, 2005; Rubin, 2011, 2017). There are several Qur’anic passages and hadiths (reports of the teachings of Muhammad, which are among the most important sources of authority in Islam) supporting this idea. Among the most explicit is Qur’an passage 4:59: “O you who have believed, obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you. And if you disagree over anything, refer it to Allah and the Messenger, if you should believe in Allah and the Last Day. That is the best [way] and best in result.” This passage suggests that one should follow those in authority, but only if they rule in accordance with Allah. In short, the growing corpus of Islamic doctrine motivated rulers to employ religious authorities for all sorts of functions, including legitimating the state. This legitimating relationship became codified as the corpus of Islamic doctrine, including the most trusted hadiths, was formulated in the first Islamic centuries. We denote this as the “exogenous component” of the legitimating technology, or \(\theta\). In the context of our model, these historical differences are mapped into a higher \(\theta\) for the Islamic Middle East.

Secondly, economically-inhibitive religious proscriptions existed—and in fact abounded—in both Christianity and Islam. Although it is not clear whether they were initially more restrictive in Western Europe or the Middle East, they persisted for much longer in the latter. For instance, Kuran (2005, 2011) cites how Islamic law regarding partnerships and inheritance combined to discourage long-lived or large business ventures. More generally, Islamic law, as formulated in the first few centuries of Islam, covers numerous aspects of commercial life. Another well-known set of proscriptions are those related to usury, which persisted for over a millennium in both Islam and Christianity (Noonan, 1957; Rubin, 2011, 2017). For now, we note that proscriptions typically lasted for much longer in Islam. We do not claim that proscriptions were initially more severe in one religion or the other.

4.2.2 Initial conditions q and \(\lambda\)

At the starting point of our analysis of the Middle East, the beginning of the Umayyad Caliphate in 661CE, the “Islamic world” was not thoroughly Muslim. In fact, it was not so for at least a few centuries after the onset of Islam, which first spread along trade routes before spreading into other Muslim-controlled territory (Ensminger, 1997; Michalopoulos et al., 2016, 2018). Though Islamic political authority spread quickly, reaching the Iberian Peninsula in the west and the Indian subcontinent in the east within its first century under the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), “Muslims still formed a small part of the populace... [Umayyad] authorities, who realized that this would deprive them of much-needed tax revenue, did not encourage conversion” (Bessard 2020, p. 18).Footnote 34 In the context of our model, this suggests a “low q” initial condition in the Middle East.

Moreover, as we already noted, Islam was born conterminously with empire, to the point that in its first few decades (through the end of the first Caliphate in 661CE), political and religious authority was concentrated in the ruler. The first four Muslim caliphs (632–661CE), who were all companions of Muhammad, claimed to have religious authority vested in themselves. As noted above, there is dispute in the historical literature regarding the extent to which their successors, the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750CE), attempted to make similar claims. Some argue that the Umayyads attempted to do so, although less successfully given their distance from the Prophet (Crone & Hinds, 1986; Donner, 2010, 2020). Others argue that other sources of legitimacy were also employed, such as claims to hereditary rule and supporting market activity (Rubin, 2003; Bessard, 2020). While it is certainly true that several Umayyad leaders were not personally pious, they did play a significant role in defining Islamic rituals—including the daily prayer, Friday prayer, and the hajj—and their coins featured statements of faith and were written in the Arabic script, which at the time was closely associated with the Qur’an (Donner 2010, p. 193–205). Regardless of how subsequent Umayyad (and Abbasid) rulers ultimately employed religious legitimacy, at the onset of the period under study (i.e., 661CE), we interpret this history (as argued by the work of historians of the period) as mapping directly into a high initial \(\lambda\).

In summary, despite the population largely being non-Muslim, initially at least, the legitimating relationship between rulers and religious authorities was clearly codified in the Islamic Middle East during the early Middle Ages. These historical characteristics can be mapped, in the context of our model, into “low q, high \(\lambda\)” initial conditions.

The historical characteristics of Western Europe, following the fall of the Roman Empire, were somewhat opposite to those we identified for the Middle East. First of all, the Roman population had largely become Christianized in the fourth and fifth centuries, so that Christianity was predominant in the Germanic “follower kingdoms.” On the other hand, again as a consequence of the environment in which Christianity was born, the political power of the church was relatively small, to the point that the Germanic “follower kingdoms” were not initially ruled by Christians. We map therefore these historical characteristics of Western Europe into “high q, low \(\lambda\)” initial conditions in the model.

4.3 Matching model dynamics and historical trajectories

Qualitatively, the parameters and the initial conditions we identified in the historical narratives in the previous section suggest a mapping into region II of Fig. 2 for the Islamic Middle East and into region III for the Christian West. We consider the two regions in turn, providing a narrative match between the dynamics implied by the model starting from these regions and the documented historical trajectories.

4.3.1 Christian west

Our mapping of the Christian West into region III of Fig. 2 following the fall of the Western Roman Empire implies that the West could have converged to either the secular or the religious stationary state in the long-run. The implied dynamics from this region are sensitive to slight variations in initial conditions and they depend on the relative speeds of cultural and institutional change. Since the exogenous component of the legitimating technology, \(\theta\), was relatively low in the Christian West, Proposition 3 indicates that the basin of attraction should be larger for the “secular” stationary state than it was for the Muslim Middle East. Importantly, however, the paths to this basin of attraction, should these paths reach the basin, are not monotonic: they allow for historical trajectories characterized by early institutional changes whereby rulers delegated power to religious clerics to gain religious legitimacy in the face of a largely religious civil society, before turning back to secular institutional structures.

These transitory, non-monotonic dynamics of institutions characterized Western Europe until the 11th century (although not in Northern Europe, which was Christianized between the 8th and 12th centuries). We begin the analysis after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476CE. As noted above, the Christian West was in a “high q, low \(\lambda\)” state at this starting off point. The model’s dynamics (see region III of Fig. 2) suggest that the institutionalized use of religious legitimacy (\(\lambda\)) should increase initially, while the population should become less religious. At some point, depending on which of these effects occurs more rapidly, a basin of attraction will be reached whereby either a “secular” or “religious” equilibrium emerges.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, the majority-Christian civil society provided a strong incentive for Germanic rulers to either convert to Christianity or promote Christianity. For instance, the Frankish king Clovis (r. 481–509) converted and employed Christianity to legitimate his Frankish expansion into new territory (Tierney 1970, Rubin 2017, pp. 62–63). Likewise, the Visigoths converted to Christianity under Recared (r. 586–601), with the Church serving as an important source of legitimacy until they were overrun by Muslim invaders in 711. Germanic rulers ultimately became among the leading defenders of Christianity, with Charlemagne’s crowning by the pope in 800CE the most visible manifestation.

Around 1000 CE, the re-birth of commerce gave rise to independent cities and increased tensions between religious and secular elites (Angelucci et al., 2022; Rubin, 2011). Although we do not model the re-emergence of trade endogenously—indeed, it can be viewed as an exogenous shock relative to the political economy environment we model—it had clear implications for the institutional and cultural dynamics at the heart of the model. The rebirth of commerce entailed that religious proscriptions (\(\phi\) in our model), such as the ban on usury, were more economically harmful. In the absence of widespread trade prior to the Commercial Revolution, such proscriptions had little dampening effect on the economy. Yet, they became increasingly harmful as trade flourished (Rubin, 2011). Using the terminology of our model, the increase in \(\phi\) combined with the relatively low \(\theta\) increased the basin of attraction of the “secular equilibrium,” encouraging rulers to break with the Church as a primary means of legitimation.

The most important event in this break was the Investiture Controversy (1075–1122), a conflict between various secular rulers and the papacy over the role of the former in religious affairs. The Investiture Controversy took place in part due to the political economy dynamics noted above. In response to growing secular power over religious affairs, Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073–85) issued a series of reforms regarding the role of secular rulers in Church affairs, including investiture. Although there was back and forth between rulers and the Church, by this point the value of religious legitimation was on the decline, and a movement towards the basin of attraction of the “secular equilibrium” had commenced. The Investiture Controversy culminated with the Concordat of Worms in 1122. In the following two centuries, the Church sought to impose its own set of laws (canon law) across Europe, but to no avail. Rulers, lords, merchants and other elites increasingly turned to other forms of law that covered manorial relations, merchant activity, urban codes, and royal jurisprudence (Berman, 1983). With respect to legitimating arrangements, European rulers increasingly sought alternative justifications for their rule (i.e., further lowering \(\lambda\)) (Tierney 1988, pp. 33-95). They found these alternative justifications in the universities, where leading scholars provided justification for secular rule based on Aristotelian thought, while others helped codify various branches of secular law such as merchant law, feudal law, and manorial law (Berman, 1983; Cantoni & Yuchtman, 2014; Hollenbach & Pierskalla, 2020). By the 14th century, the papacy was under the thumb of the French king. The entire papal court was moved to Avignon from 1309–76. This transition can be seen in the type of advice given to monarchs on the “art of ruling.” Blaydes et al. (2018) find that it was precisely in this period that European political advice texts began to de-emphasize religious appeals.

As a whole, these events helped place much of Western Europe on a path towards the more “secular” equilibrium described in our model. Institutional change in the direction of more political power to the Church did not arise fast enough, especially after the Investiture Controversy gave local rulers greater suzerainty over their lands. In the context of the model, Western Europe thus ultimately ended up in region IV of Fig. 2—the basin of attraction that results in a “secular equilibrium”. In this region, the declining political power of religious clerics reinforced cultural changes that placed less emphasis on religious values. These reinforcing mechanisms ultimately resulted in lock-in, whereby there was little role for religious authorities in legitimating political rule, and more political power rested in civil society.

The Reformation played a key role in further secularizing civil society. In the context of the model, such secularization is necessary for a society to reach region IV of Fig. 2. In England, Greif and Rubin (2023a) argue that following the Reformation, the political power of religious authorities dropped significantly and the law (as formed in Parliament) became a key source of royal legitimacy. In Germany, Cantoni et al. (2018) find that, following the Reformation, there was a massive reallocation of resources and education from religious to secular purposes. In other words, where the Reformation undermined the political power of the Church (i.e., lowered \(\lambda\)), less cultural capital was invested in religious pursuits. This is precisely the type of lock-in the model predicts will arise in a society in region IV.

4.3.2 Islamic middle east

Our qualitatively mapping of the Middle East initially (i.e., after 661CE) into region II of Fig. 2 suggests historical trajectories somewhat specular with respect to those of the West: convergence to the religious stationary state in the long-run but through historical trajectories characterized by institutional changes whereby rulers limited the power of religious clerics early on, before turning back to a strategy of delegation in exchange for legitimacy which led society to a religious stationary state. This insight helps resolve—or at the very least, shines a new light on—the debate in the historical literature regarding the use of religious legitimacy by early Islamic empires. While there is much reason to believe that early Islamic empires sought sources of legitimacy outside of Islam (though not to its exclusion), this is precisely what our model predicts should happen, initially at least, in a “high \(\lambda\), low q” society.

Following the rapid political spread of Islam in its first few decades under the First Four Caliphs (632–61), institutional change transpired favoring economic—not religious—elites. The merchant class saw a rise in its economic and political power in the first few centuries of Islam (Bessard 2020, ch. 9). A common currency and political institutions facilitated a massive expansion of trade. The Umayyad and Abbasid states sponsored markets and provided privileges for leading merchants, directly involving themselves in urban retailing to “establish their power and legitimacy from the first decades of the eighth century” (Bessard 2020, p. 5). This was not just a period of economic growth; it was also the “Golden Age” of rationalist Islamic thought. Islamic science, technology, mathematics, architecture, and medicine were the envy of Western Eurasia. Hence, there were forces pushing against the political power of religious elites (i.e., lower \(\lambda\), as is predicted in region II).

Yet, these forces did not move fast enough to reach the basin of attraction in which a “secular” equilibrium emerged in the long run. Religious authorities provided administrative services to a largely non-Muslim population throughout the Middle East and North Africa. After 661, in the Sunni successor empires (the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates), religious authorities served a central role in administering the state although the population was not yet Islamized. Most important was their role in providing legal services and overseeing various aspects of state administration. With respect to the early Abbasid Empire (8th century), Hallaq (2005, p. 182-83) writes:

[T]he government was in dire need of legitimization, which it found in the circles of the legal profession. The legists served the rulers as an effective tool for reaching the masses, from whose rank they emerged and represented ... Jurists and judges emerged as the civil leaders who, though themselves products of the masses, found themselves involved in the day-to-day running of their affairs ... [T]he judges were not only justices of the court, but the guardians and protectors of the disadvantaged, the supervisors of charitable trusts, the tax-collectors and the foremen of public works. They resolved disputes, both in the court and outside it, and established themselves as the intercessors between the populace and the rulers.

As a result, the Umayyads and their successors, the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258CE), relied on legitimacy supplied by religious authorities. Especially after the religious establishment consolidated in the ninth century (Hallaq, 2005; Coşgel et al., 2009; Rubin, 2017), religious authorities were the primary agents capable of determining whether rulers acted in accordance with Islam (i.e., whether secular authorities and Allah “disagreed over anything”, to quote the Qur’anic passage cited above). This relationship was formally institutionalized with the rise of the madrasa system in the 11th century and the diversion of resources away from secular intellectual pursuits (e.g., science, mathematics) and into religious learning (Chaney, 2016; Kuru, 2019).

Importantly, as posited in our model, the Middle East became Islamicized prior to an unraveling of political power for religious clerics. In the context of Fig. 2, this placed much of the Muslim Middle East in the basin of attraction of a “religious equilibrium” (region I). In the model, as in Bisin and Verdier (2001), the dominant cultural group (initially, non-Muslims) had less incentive to pass down their cultural traits, especially when the institutional structure was not aligned with their cultural (religious) beliefs. Institutional pressures favoring the minority culture can incentivize conversion to that culture. In the Islamic context, such institutionalized incentives were provided via taxes on non-Muslims (jizya).Footnote 35 In Egypt, for example, Saleh (2018) finds evidence of massive conversions of lower socio-economic status Copts into Islam: by 1200, Muslims were 80% of the Egyptian population, and by 1500 they were over 90% of the population. Saleh (2018) argues that negative selection among Copts was due to the poll tax that non-Muslims had to pay; those that could not afford it simply converted to Islam.

This history is consistent with the dynamics predicted in our model. As a society approaches the basin of attraction of the “religious equilibrium,” religious culture reinforces clerical political power, and a religious stationary state becomes locked-in in the long run. In the Middle East and North Africa, this equilibrium was characterized by a massive expansion in madrasas (Chaney, 2016; Kuru, 2019), less frequent “rationalist” interpretation of Islam in favor of traditionalist interpretation (i.e., the “closing of the gate of ijtihād” (Schacht, 1964; Coulson, 1969; Weiss, 1978; Hallaq, 1984, 2001)), and little political bargaining power for the economic elite (Pamuk, 2004a, b).

Two examples from two different periods and regions highlight the reinforcement of Muslim institutions and culture in a “high q, high \(\lambda\)” world. First, Chaney (2013) finds that medieval Egyptian religious authorities were more secure in their rule (e.g., higher \(\lambda\)) when the Nile flooded or there was a drought. This is precisely when a ruler would most need religious legitimacy, both because the tax base would be lower and because there was a greater threat of revolt. Moreover, as noted above, this was a period of increasing Islamization of the Egyptian population (i.e., q was increasing). This suggests the presence of a “high q, high \(\lambda\)” equilibrium, with cultural and institutional forces reinforcing each other.

A second example comes from the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, where the population had largely converted to Islam centuries prior to Ottoman expansion (i.e., q was high). In the late 15th century, the Ottomans brought the religious establishment into the state, establishing the office of the Grand Mufti (chief religious jurist). This gave the Ottomans significant power to formulate controversial decisions in a manner consistent with Islam (Imber, 1997). Meanwhile, the reinforcement of institutions and culture strengthened after the Ottomans conquered the Egyptian Mamluk Empire (in 1517) and took control over Mecca and Medina, the two holy cities of Islam. This further enhanced the capacity of clerics to confer legitimacy by associating the sultan with Islamic piety (e.g., mentioning his name in each Friday sermon or supporting obedience to him in judicial rulings) (Hallaq 2005, ch. 8). Thus, the high level of religious legitimacy (\(\theta\)) provided by Muslim clerics resulted in a “high q, high \(\lambda\)” equilibrium for much of Ottoman history.

4.4 The long divergence through lens of the model

Our model squares two of the leading theories of the “Long Divergence,” and in doing so directly addresses one stylized fact highlighted in the literature: the persistence of religious legitimacy in the Middle East and the secularization of politics in Western Europe. The model suggests that the diverging long-run paths of the economies of these two regions—“high q, high \(\lambda\)” in the Middle East and “low q, low \(\lambda\)” in Western Europe—were in part a result of the relatively high efficacy of religious legitimacy (\(\theta\)) in the Islamic world. This meant that the two regions had different responses to religious proscriptions (\(\phi\)), which were not necessarily stronger in either region. In Western Europe, once commerce revived in the 11th and 12th centuries, religious proscriptions were sufficiently economically damaging to push society towards the basin of attraction that ultimately resulted in a low q, low \(\lambda\) equilibrium. On the other hand, in the Islamic world such religious proscriptions may have been even more economically damaging initially, given that the Islamic world was ahead of Europe. However, the relatively high \(\theta\) in Middle Eastern societies helps account for the presence (and persistence) of strict religious proscriptions in a “high q, high \(\lambda\)” equilibrium. Although proscriptions diminish the attractiveness of religious legitimacy to rulers and of passing down religious traits to one’s child, proscriptions are mitigated for the ruler if religious legitimacy is effective enough (i.e., \(\theta\) is high) and enough of the population is religious (i.e., q is high). Hence, supporting economically-inhibitive religious doctrine is more than worth it for a ruler in a high-q society when \(\theta\) is also large.

These insights therefore unify Kuran ’s theory emphasizing religious proscriptions with theories emphasizing religious legitimacy (Rubin, 2017; Platteau, 2017; Kuru, 2019). Kuran ’s theory centers not just on the fact that religious proscriptions existed in Islamic law, but that they persisted for so long after they were useful. Our theory sheds light on the how religious culture reinforced clerical political power, and vice versa, which resulted in the persistence of religious proscriptions. Meanwhile, an emphasis on religious proscriptions reveals why legitimating arrangements changed over time in Europe.

These insights also shed light on a second stylized fact central to the literature: the long-run economic vibrancy of Western Europe relative to the Middle East. Even though there are welfare-enhancing properties of religious legitimacy (as highlighted in the model), these welfare gains can be overwhelmed by religious proscriptions. As Kuran (2011) points out, such proscriptions can have unforeseeable, path dependent consequences for economic growth. For instance, Islamic partnership law and inheritance law jointly discouraged larger enterprises, which ultimately stifled the creation of anything remotely resembling the corporate form (Kuran, 2005, 2011). Meanwhile, the persistent dominance of Islamic law over commercial transactions entailed the slow (or non-) adoption of new organizational forms and financial instruments from abroad, which itself had numerous unforeseeable economic consequences (Rubin, 2010, 2017; Kuran & Rubin, 2018).

So far, our model does not account for the third major theory of the Long Divergence: Middle Eastern rulers had more unconstrained power relative to other elites (i.e., European governance was more limited). As such, it cannot account for an important stylized fact mentioned in the introduction: the growth in limited governance in Western Europe but not the Middle East. Blaydes and Chaney (2013) ascribe the relatively greater power of Middle Eastern rulers to their access to slave soldiers, which gave rulers access to coercive power without ceding political power. Meanwhile, weaker European rulers had greater incentive to negotiate with their economic (i.e., feudal) elites for revenue and military power, since they had little capacity to rule otherwise (Duby, 1982). Throughout Europe, rulers also ceded power to urban burghers, who had relative freedom from imperial rule (Mann, 1986; Putnam et al., 1994; Angelucci et al., 2022; Schulz, 2022). More generally, this meant that Muslim rulers had fewer constraints on their power, which a large literature suggests is harmful for economic growth (North & Weingast, 1989; Acemoglu et al., 2005b; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012; North et al., 2009; van Zanden et al., 2012). Our model currently does not permit the ruler to share power with other (secular) elites that may constrain her, so it cannot speak to the conditions under which this occurs. In the next section, we extend the model to consider how the devolution of political power interacts with the various parameters of importance in our model (namely, \(\theta\) and \(\phi\)).

5 Religious legitimacy and limited governance

In this section we extend and enrich the model introduced in Sect. 2 to consider the emergence of limited governance.Footnote 36 Pre-modern states tended to have little fiscal capacity or capacity to provide law and order to regions far away from the capital. Administrative capacity tended to be quite weak in most parts of the world, meaning that rulers could not easily implement their desired policies (de Lara et al., 2008; Greif, 2008; Karaman & Pamuk, 2013; Besley & Persson, 2014; Ma & Rubin, 2019). As such, there was a limit to the potential tax revenue available to rulers that was well below the optima on a Laffer curve (Besley & Persson, 2009, 2010; Dincecco, 2009; Johnson & Koyama, 2017). This issue is (implicitly) central to the framework proposed by Blaydes and Chaney (2013). Without the capacity to collect revenue on their own, pre-modern rulers had to delegate tax collection to powerful agents. Such powerful agents could deter tax evasion via force and more easily assess taxable surpluses. More importantly, these powerful agents could limit what the ruler could do because they held the power of the purse.

The degree to which rulers had to delegate tax collection (and, more generally, the administrative functions of the state) depended on their own power vis-à-vis other elites. According to Blaydes and Chaney (2013), Muslim rulers had to delegate less because they had access to slave soldiers. This meant they did not need local elites for military service or, oftentimes, tax collection. Meanwhile, feudal arrangements in medieval Europe were such that local taxes were collected by powerful local elites, and in return rulers received military service and, occasionally, tax revenue.

We study the interactions between rulers and local elites in a political economy model where political power is divided between three groups: the ruler, religious clerics, and a secular elite (e.g., feudal lords, parliament, or the military). This allows us to incorporate into the model a fundamental element of the socio-economic environment under study, as discussed in the Introduction: a tradeoff between religious legitimacy and limited governance with respect to the state’s fiscal capacity. This, in turn, allows us to study the conditions under which the ruler shares political power with the secular elite, who have the capacity to collect taxes.

We treat secular elites as representatives of the citizenry. In terms of the distribution of power between groups, we assign the “ruling coalition” the combined weight of the ruler and the secular elites, \(\frac{1}{2}+ \frac{1-\lambda }{2}=1-\frac{\lambda }{2}\), in social welfare. This is similar to the baseline model, with the citizenry being replaced by the secular elites. In other words, if the ruler and the secular elites are the “ruling coalition” (as in North, Wallis and Weingast 2009),

then \(1-\frac{\lambda }{2}\) is the total weight of the coalition. Clerics have weight \(\frac{\lambda }{2}\) and citizens have no political power (i.e., zero weight).Footnote 37

Secular elites enforce tax compliance and share with the ruler the tax surplus. The share of this surplus accruing to the ruler vis-a-vis the secular elites is \(\beta \in [0,1]\).Footnote 38 As a simple illustration, a regime where \(\lambda =1\) can be interpreted as a theocracy, while \(\lambda =0\) is a dictatorship when \(\beta =1\) and a republic when \(\beta =0\), as the ruler does not benefit from tax revenue in the latter case. It is therefore the tradeoff between \(\beta\) and \(\lambda\) that determines the state’s fiscal capacity.

We denote \(\alpha _{l}\in [0,{\overline{\alpha }}_{l}]\) the enforcement effort of the secular elites, with \(\overline{\alpha }_{l}>0\). Let \(\mu \frac{\alpha _{l}^{2}}{2}\), with \(\mu >0\), be a quadratic cost associated with this effort. The utility of the secular elites can be expressed as:

Consider now the utility of the ruler. We assume the ruler faces a cost \(\rho \alpha _{l}\) when letting the secular elite enforce tax compliance \(\alpha _{l}.\) For instance, medieval European rulers provided feudal lords with lands to administer. Tax enforcement was accompanied with the hiring and building of a force capable of violence by these lords. These elements suggest that the more the ruler cedes to lords the power of tax enforcement, the larger is the military power of the lords, which may eventually be turned against the ruler herself. The cost \(\rho \alpha _{l}\) is a simple way to capture such threats. We maintain the assumption that the maintenance cost of religious infrastructure paid by the clerics is F(m). The utility of the ruler is then

and the utility of the clerics is:

In order to focus on the institutional implications of endogenous tax enforcement, we also simplify the production structure of the economy. More precisely, we assume that all citizens are now endowed with one unit of resource out of which they produce \(\frac{1}{1+\phi \alpha _{c,t}}\) of the consumption good. They then face the dichotomous choice of complying or not with tax collection. When an individual of type \(i\in \{Re,S\}\) complies with taxation, he pays the effective tax rate \(\tau\) on his output, while enjoying from a welfare point of view, a “perceived" tax rate \(\tau _{i,t},\) with as before \(\tau _{Re,t}=\tau (1-\theta \alpha _{c,t})\) and \(\tau _{S,t}=\tau _{t}\). When the individual decides to evade tax collection, he faces an expected consumption penalty which depends on two factors: i) the capacity of tax enforcement on the part of the elites, and ii) the capacity of that individual to escape taxation. More precisely, denote by \(\epsilon (\alpha _{l,t})\) a measure of the capacity of tax enforcement by the elites, increasing in the elite’s tax collection effort \(\alpha _{l,t}\).Footnote 39 Assume as well that each individual has an idiosyncratic (inverse) capacity to evade taxes c drawn from a uniform distribution on a segment \([0,{\overline{c}}]\), with \({\overline{c}}>0\). An individual with characteristic c who does not comply with tax collection incurs an expected consumption penalty \(c\epsilon (\alpha _{l,t})\).Footnote 40 In this modified version of the model, the expected utility of an individual belonging to type \(i\in \{Re,S\}\) with an (inverse) evasion capacity c isFootnote 41:

5.1 Societal equilibrium and dynamics

The societal equilibrium in generation t is a Nash equilibrium of the game between the ruler, clerics, secular elite, and civil society. In this equilibrium, religious infrastructure m is chosen to maximize social welfare,

The clerics and secular elite choose, respectively, \(\alpha _{c,t}\) and \(\alpha _{l,t}\). We denote \(\{m_{t}(\lambda _{t}),\) \(\alpha _{c,t}(\lambda _{t}),\) \(\alpha _{l,t}(\lambda _{t},\beta _{t})\}\) the equilibrium. In the rest of this section, we omit the time indices when not necessary. Solving the equilibrium in any period t, we obtain the following results:

Lemma 4

(Religious infrastructure) The equilibrium investment in religious infrastructure \(m(\lambda )\) and the optimal effort of the clerics \(\alpha _{c}(\lambda )\) are increasing in \(\lambda\), and independent of \(\beta\), \(\theta\), and \(\phi\).

Lemma 5

(Tax enforcement) The equilibrium enforcement effort of the secular elite \(\alpha _{l}(\lambda ,\beta )\) is decreasing in \(\beta\), \(\lambda\), q, \(\theta\), and \(\phi\).